Abstract

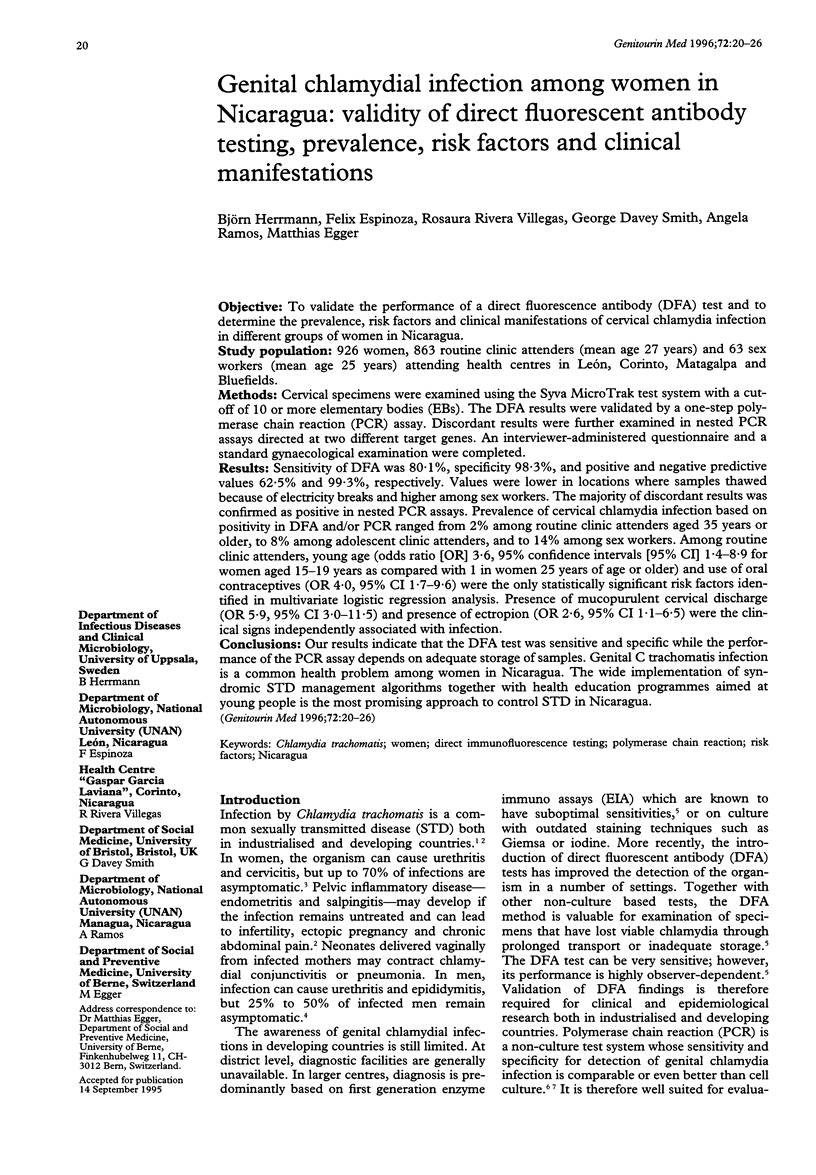

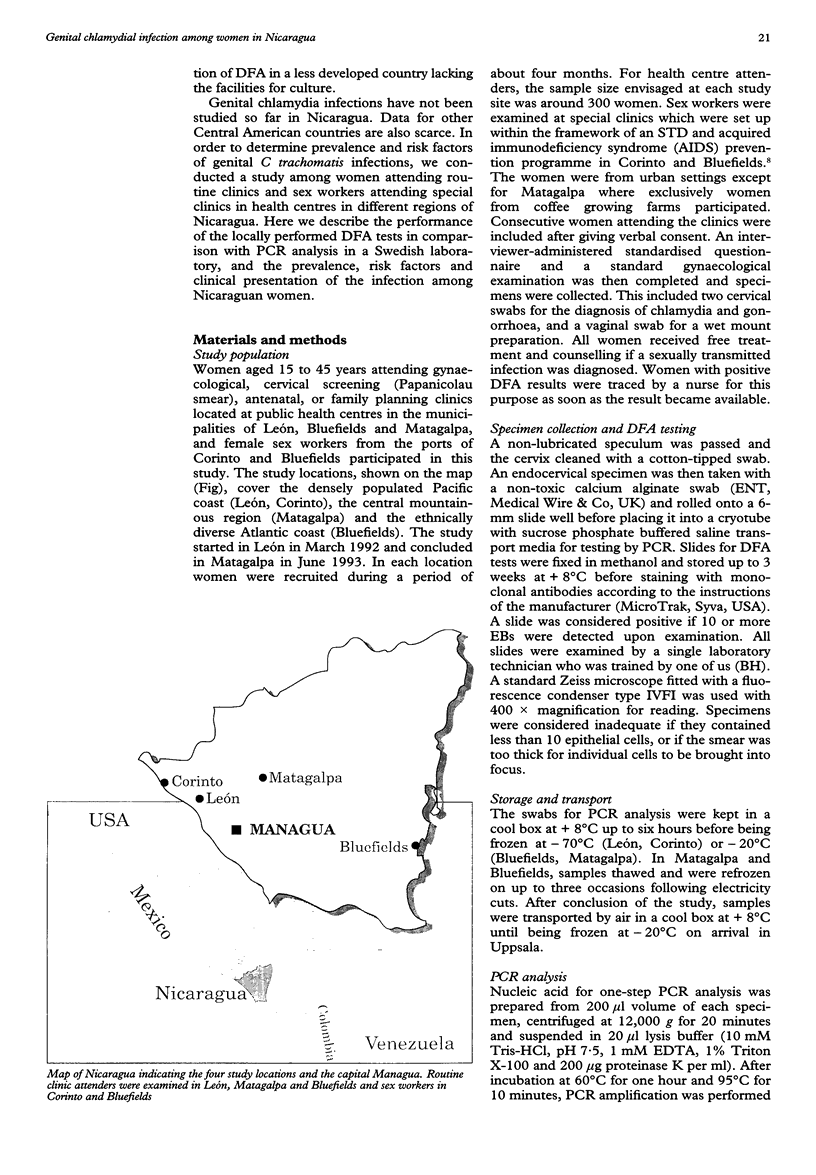

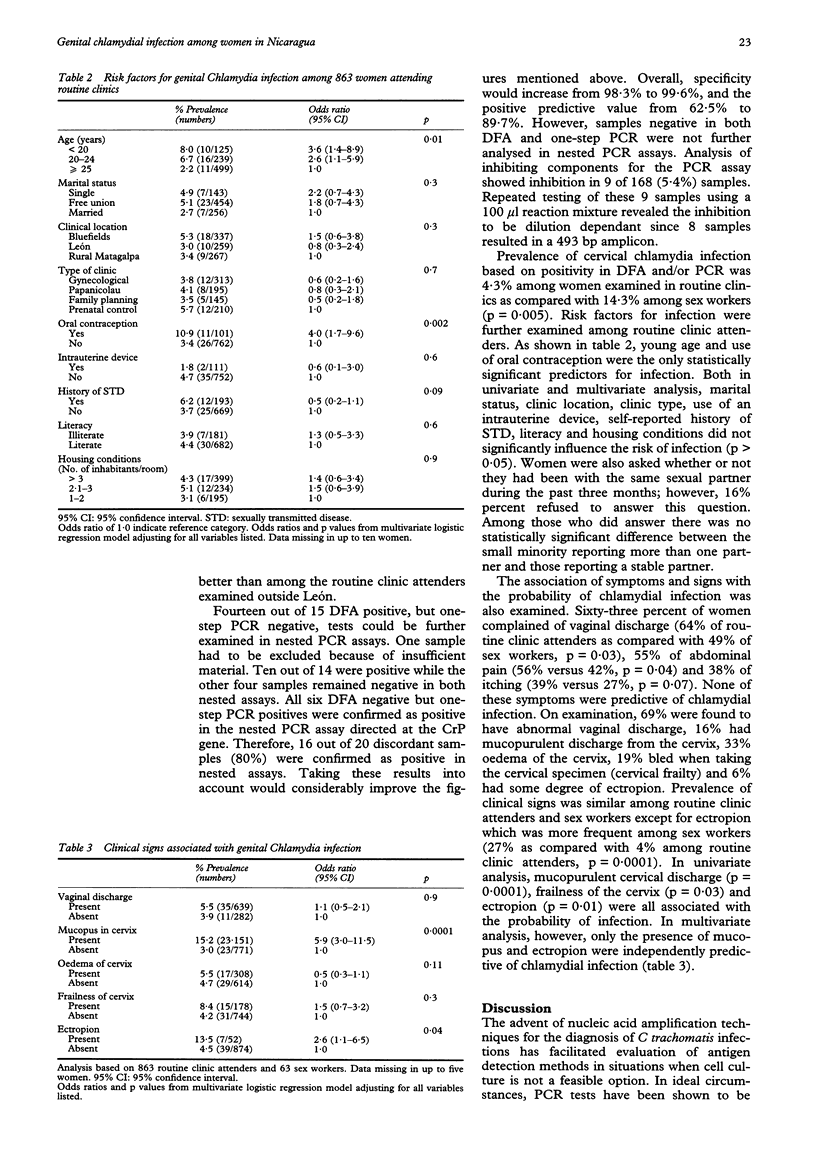

OBJECTIVE: To validate the performance of a direct fluorescence antibody (DFA) test and to determine the prevalence, risk factors and clinical manifestations of cervical chlamydia infection in different groups of women in Nicaragua. STUDY POPULATION: 926 women, 863 routine clinic attenders (mean age 27 years) and 63 sex workers (mean age 25 years) attending health centres in León, Corinto, Matagalpa and Bluefields. METHODS: Cervical specimens were examined using the Syva MicroTrak test system with a cut-off of 10 or more elementary bodies (EBs). The DFA results were validated by a one-step polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. Discordant results were further examined in nested PCR assays directed at two different target genes. An interviewer-administered questionnaire and a standard gynaecological examination were completed. RESULTS: Sensitivity of DFA was 80.1%, specificity 98.3%, and positive and negative predictive values 62.5% and 99.3%, respectively. Values were lower in locations where samples thawed because of electricity breaks and higher among sex workers. The majority of discordant results was confirmed as positive in nested PCR assays. Prevalence of cervical chlamydia infection based on positivity in DFA and/or PCR ranged from 2% among routine clinic attenders aged 35 years or older, to 8% among adolescent clinic attenders, and to 14% among sex workers. Among routine clinic attenders, young age (odds ratio [OR] 3.6, 95% confidence intervals [95% CI] 1.4-8.9 for women aged 15-19 years as compared with 1 in women 25 years of age or older) and use of oral contraceptives (OR 4.0, 95% CI 1.7-9.6) were the only statistically significant risk factors identified in multivariate logistic regression analysis. Presence of mucopurulent cervical discharge (OR 5.9, 95% CI 3.0-11.5) and presence of ectropion (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.1-6.5) were the clinical signs independently associated with infection. CONCLUSIONS: Our results indicate that the DFA test was sensitive and specific while the performance of the PCR assay depends on adequate storage of samples. Genital C trachomatis infection is a common health problem among women in Nicaragua. The wide implementation of syndromic STD management algorithms together with health education programmes aimed at young people is the most promising approach to control STD in Nicaragua.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

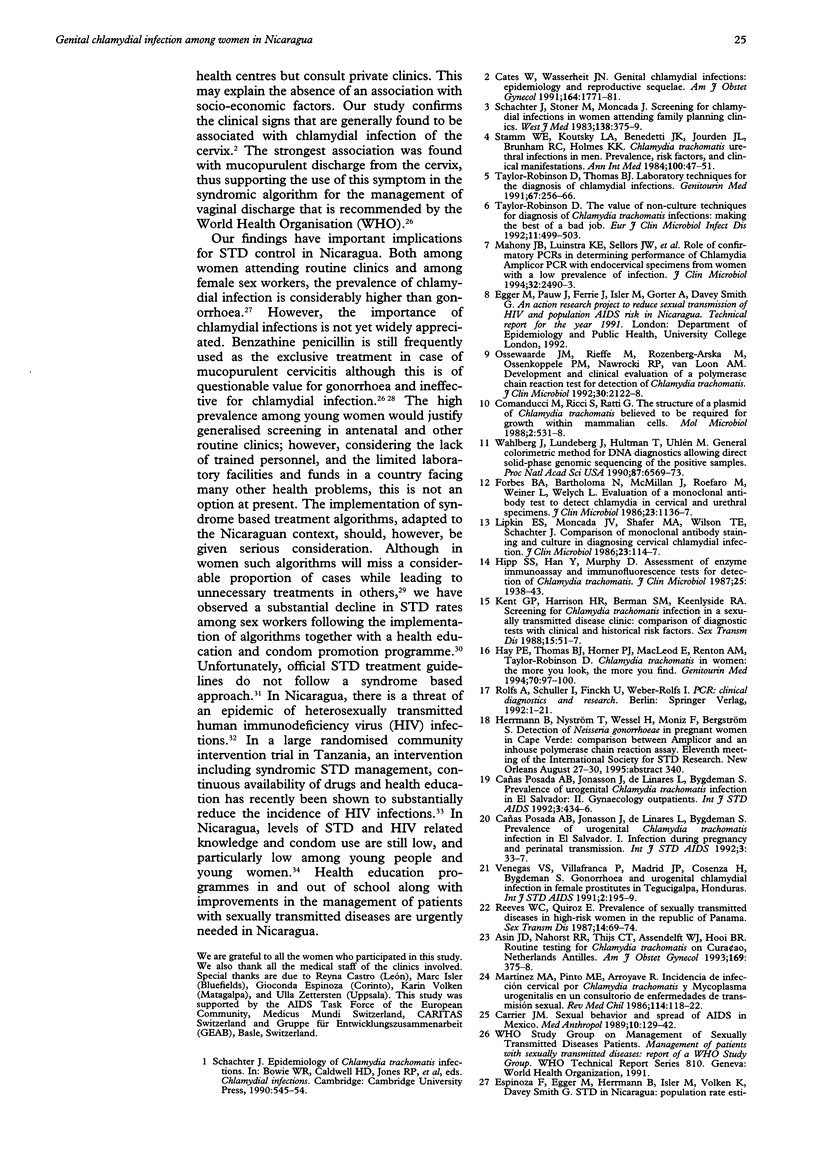

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Asin J. D., Nahorst R. R., Thijs C. T., Assendelft W. J., Hooi B. R. Routine testing for Chlamydia trachomatis on Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Aug;169(2 Pt 1):375–378. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier J. M. Sexual behavior and spread of AIDS in Mexico. Med Anthropol. 1989 Mar;10(2-3):129–142. doi: 10.1080/01459740.1989.9965958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro I., Bergeron M. G., Chamberland S. Characterization of multiresistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated in Nicaragua. Sex Transm Dis. 1993 Nov-Dec;20(6):314–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates W., Jr, Wasserheit J. N. Genital chlamydial infections: epidemiology and reproductive sequelae. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Jun;164(6 Pt 2):1771–1781. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90559-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cañas Posada A. B., Jonasson J., de Linares L., Bygdeman S. Prevalence of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in El Salvador. II. Gynaecology outpatients. Int J STD AIDS. 1992 Nov-Dec;3(6):434–436. doi: 10.1177/095646249200300607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comanducci M., Ricci S., Ratti G. The structure of a plasmid of Chlamydia trachomatis believed to be required for growth within mammalian cells. Mol Microbiol. 1988 Jul;2(4):531–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Ferrie J., Gorter A., González S., Gutiérrez R., Pauw J., Smith G. D. HIV/AIDS-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Managuan secondary school students. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1993;27(4):360–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes B. A., Bartholoma N., McMillan J., Roefaro M., Weiner L., Welych L. Evaluation of a monoclonal antibody test to detect chlamydia in cervical and urethral specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Jun;23(6):1136–1137. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.6.1136-1137.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosskurth H., Mosha F., Todd J., Mwijarubi E., Klokke A., Senkoro K., Mayaud P., Changalucha J., Nicoll A., ka-Gina G. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1995 Aug 26;346(8974):530–536. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay P. E., Thomas B. J., Horner P. J., MacLeod E., Renton A. M., Taylor-Robinson D. Chlamydia trachomatis in women: the more you look, the more you find. Genitourin Med. 1994 Apr;70(2):97–100. doi: 10.1136/sti.70.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipp S. S., Han Y., Murphy D. Assessment of enzyme immunoassay and immunofluorescence tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol. 1987 Oct;25(10):1938–1943. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.10.1938-1943.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent G. P., Harrison H. R., Berman S. M., Keenlyside R. A. Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis infection in a sexually transmitted disease clinic: comparison of diagnostic tests with clinical and historical risk factors. Sex Transm Dis. 1988 Jan-Mar;15(1):51–57. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low N., Egger M., Gorter A., Sandiford P., González A., Pauw J., Ferrie J., Smith G. D. AIDS in Nicaragua: epidemiological, political, and sociocultural perspectives. Int J Health Serv. 1993;23(4):685–702. doi: 10.2190/1P6N-BPDW-M7BM-P2DR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony J. B., Luinstra K. E., Sellors J. W., Pickard L., Chong S., Jang D., Chernesky M. A. Role of confirmatory PCRs in determining performance of Chlamydia Amplicor PCR with endocervical specimens from women with a low prevalence of infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1994 Oct;32(10):2490–2493. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2490-2493.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez M. A., Pinto M. E., Arroyave R. Incidencia de infección cervical por Chlamydia trachomatis y Mycoplasma urogenitales en un consultorio de enfermedades de transmisión sexual. Rev Med Chil. 1986 Feb;114(2):118–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossewaarde J. M., Rieffe M., Rozenberg-Arska M., Ossenkoppele P. M., Nawrocki R. P., van Loon A. M. Development and clinical evaluation of a polymerase chain reaction test for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992 Aug;30(8):2122–2128. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2122-2128.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Bale M. J., Schulte K. R., Koontz F. P. Comparison of the Quantum II Bacterial Identification System and the AutoMicrobic System for the identification of gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Jan;23(1):1–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.1.1-5.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada A. B., Jonasson J., de Linares L., Bygdeman S. Prevalence of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in El Salvador. I. Infection during pregnancy and perinatal transmission. Int J STD AIDS. 1992 Jan-Feb;3(1):33–37. doi: 10.1177/095646249200300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves W. C., Quiroz E. Prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in high-risk women in the Republic of Panama. Sex Transm Dis. 1987 Apr-Jun;14(2):69–74. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J., Stoner E., Moncada J. Screening for chlamydial infections in women attending family planning clinics. West J Med. 1983 Mar;138(3):375–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamm W. E., Koutsky L. A., Benedetti J. K., Jourden J. L., Brunham R. C., Holmes K. K. Chlamydia trachomatis urethral infections in men. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1984 Jan;100(1):47–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Robinson D. The value of non-culture techniques for diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infections: making the best of a bad job. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992 Jun;11(6):499–503. doi: 10.1007/BF01960803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Robinson D., Thomas B. J. Laboratory techniques for the diagnosis of chlamydial infections. Genitourin Med. 1991 Jun;67(3):256–266. doi: 10.1136/sti.67.3.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venegas V. S., Villafranca P., Madrid J. P., Cosenza H., Bygdeman S. Gonorrhoea and urogenital chlamydial infection in female prostitutes in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Int J STD AIDS. 1991 May-Jun;2(3):195–199. doi: 10.1177/095646249100200309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg J., Lundeberg J., Hultman T., Uhlén M. General colorimetric method for DNA diagnostics allowing direct solid-phase genomic sequencing of the positive samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Sep;87(17):6569–6573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]