Abstract

Physical exercise is recognized as an effective intervention to improve mood, physical performance, and general well-being. It achieves these benefits through cellular and molecular mechanisms that promote the release of neuroprotective factors. Interestingly, reduced levels of physical exercise have been implicated in several central nervous system diseases, including ocular disorders. Emerging evidence has suggested that physical exercise levels are significantly lower in individuals with ocular diseases such as glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa, and diabetic retinopathy. Physical exercise may have a neuroprotective effect on the retina. Therefore, the association between reduced physical exercise and ocular diseases may involve a bidirectional causal relationship whereby visual impairment leads to reduced physical exercise and decreased exercise exacerbates the development of ocular disease. In this review, we summarize the evidence linking physical exercise to eye disease and identify potential mediators of physical exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection. Finally, we discuss future directions for preclinical and clinical research in exercise and eye health.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration, biomarkers, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, neuroprotective factors, ocular diseases, physical exercise, retinal neuroprotection, retinitis pigmentosa, visual impairment

Introduction

Physical exercise (PE) is a planned, structured, and repetitive activity aimed at maintaining or improving physical fitness (Mahalakshmi et al., 2020). PE has numerous health benefits, including the prevention of acute and chronic diseases such as sudden cardiac death, acute coronary occlusion, hypertension, stroke, and diabetes (Fiuza-Luces et al., 2018; Fanous and Dorian, 2019; Bennie et al., 2020; Wake, 2022). Acute PE, typically defined as a single physical activity session, and chronic exercise (training), consisting of long-term, repeated activity, produce different physiological effects. Acute exercise primarily induces immediate physiological changes, such as transient modulation of blood flow and oxidative stress, while chronic exercise results in adaptive responses, including improved antioxidant defence and enhanced neuroplasticity. Both acute and chronic exercise play crucial but distinct roles in neuroprotection, particularly in retinal diseases, and should be investigated separately. While the positive effects of PE on neuroprotection and general well-being are established, its impact on ocular health, particularly the health of the retina, is not yet well understood.

The retina is a component of the central nervous system (CNS) situated at the back of the eye that translates patterns of light into neural signals that are transmitted to the thalamus and the cortex. PE levels are lower in patients with ocular diseases, especially those affecting the retina, such as glaucoma (Lee et al., 2019), age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (Loprinzi and Joyner, 2016), retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (Levinson et al., 2017), and diabetic retinopathy (Colberg et al., 2016). Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases characterized by damage to the optic nerve, which is crucial for vision. Permanent deterioration of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) is a characteristic feature of glaucoma. AMD is one of the leading causes of vision impairment worldwide, particularly among people aged 60 years and older. This disorder is marked by the degeneration of the macula, the central area of the retina, and results from retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) dysfunction and photoreceptor cell death (Pfeiffer et al., 2020). RP encompasses a collection of inherited eye disorders that affect the retina, resulting in the progressive deterioration of photoreceptors (initially the rods, followed by cones). Individuals with RP experience a loss of night vision and compromised peripheral vision. Diabetic retinopathy is a common complication of diabetes among adults aged from 20 years in developed countries. These conditions share common pathophysiological features like RGC death, photoreceptor degeneration, and inflammation, all of which might be modulated by PE. Moreover, there is growing evidence that PE has a neuroprotective effect on the retina, although the specific cellular and molecular mechanisms involved are not yet fully understood (Virathone et al., 2021; Chu-Tan et al., 2022).

This review aims to summarize the role of PE in ocular health, focusing on neuroprotection in the retina, and highlighting research gaps in the field. The review is structured as follows:

Overview of Physical Exercise and Ocular Health: This section will introduce the role of PE in maintaining ocular health and its influence on parameters such as intraocular pressure (IOP), ocular blood flow, and retinal neuroprotection.

Effects of Physical Exercise on Specific Retinal Diseases: In this section, we will discuss the potential neuroprotective benefits of exercise in major retinal diseases, including glaucoma, AMD, RP, and DR.

Potential Mediators of Exercise-Induced Retinal Neuroprotection: This section will highlight the molecular mechanisms through which exercise may exert its effects on the retina, focusing on neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF).

Future Directions: We will conclude with a discussion of the gaps in current knowledge and suggest avenues for future research to develop exercise-based interventions for retinal diseases.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The search strategy and selection criteria for this review were designed to comprehensively capture relevant studies linking physical exercise to ocular diseases. The search was conducted across multiple databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, using a combination of MeSH terms and keywords. Key search terms included “physical exercise,” “ocular diseases,” “glaucoma,” “age-related macular degeneration,” “retinitis pigmentosa,” and “diabetic retinopathy.” Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to refine the search and ensure a broad yet targeted retrieval of articles. Inclusion criteria were studies that investigated the relationship between physical exercise and ocular health, specifically focusing on neuroprotective effects within the retina. Exclusion criteria included studies not published in English, non-peer-reviewed articles, and those not directly addressing the impact of physical exercise on ocular diseases. The search was iteratively refined to maximize sensitivity and specificity, ensuring the inclusion of all relevant literature for a thorough review.

While a large number of references were included, this review does not qualify as a systematic review because it does not follow the predefined, rigorous methodology typically required in systematic reviews. Systematic reviews involve a structured process of identifying, selecting, and critically appraising all relevant evidence, using specific protocols and quality assessment criteria. In contrast, this review provides a comprehensive narrative synthesis of the literature without using the exhaustive search and evaluation methods necessary for a systematic review.

Overview of Physical Exercise and Ocular Health

The eye is a complex and delicate organ that requires a well-regulated environment to maintain optimal function. PE can influence a range of ocular parameters, including IOP, ocular blood flow, and retinal neuroprotection. Understanding the relationship between PE and these ocular parameters is crucial for developing strategies to prevent and manage ocular diseases.

Intraocular pressure

Elevated IOP is a major risk factor for glaucoma, a leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide (Wylęgała, 2016). Both acute and chronic exercises have been shown to reduce IOP, although the mechanisms differ. Acute exercise can lead to immediate but transient decreases in IOP, as shown in studies where IOP significantly dropped post-exercise (Zhu et al., 2018). Chronic exercise, in contrast, promotes long-term IOP regulation by enhancing ocular blood flow and decreasing systemic risk factors, which can contribute to a sustained reduction in IOP (Natsis et al., 2009; Esfahani et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2018; Vera et al., 2020). The mechanisms underlying this effect are not yet fully understood, but proposed explanations include increased aqueous humor outflow (Thomson et al., 2021), reduced episcleral venous pressure (Usha Tejaswini et al., 2020), and enhanced ocular blood flow (Wu et al., 2022). The impact of exercise on IOP depends on the type, intensity, and duration of PE. Aerobic exercise, such as running and cycling, significantly decreases IOP (Ma et al., 2022). Furthermore, longer and more intense PE sessions have been reported to cause greater IOP reductions. For example, when patients with primary open-angle glaucoma engaged in intense cycling activity (at 60% of their maximum workload) for 5 minutes following a period of moderate exercise, there was a significant reduction in their IOP by 5.95 ± 3.80 mmHg post-exercise (Ma et al., 2022). Resistance training can transiently increase IOP during exercise, but reduces IOP after training sessions (Vera et al., 2020; Gene et al., 2022; Gene-Morales et al., 2022). Furthermore, high-intensity leg press exercises under three conditions: 1-repetition maximum, 6-repetition maximum, and isometric resistance, induced a significant but transient increase in IOP, with an average increase of 26.5 mmHg and a mean IOP of 39.2 mmHg across participants (Vaghefi et al., 2021). Another study reported a transient increase in IOP during resistance training in 25 healthy young individuals who performed four basic resistance exercises (squat, military press, biceps curl and calf raise exercises) (Vera et al., 2019). This suggests that PE can modulate IOP with a progressive rise during exercise and a decrease afterwards.

Ocular blood flow

Recent research has shed light on the impact of PE on ocular blood flow. Understanding this relationship is crucial for evaluating the potential therapeutic application of PE for ocular diseases that have been linked to abnormal blood flow within the eye such as glaucoma and AMD (Zhu et al., 2018). Several human studies have contributed valuable insights into the effects of PE on ocular blood flow (Okuno et al., 2006; Wylęgała, 2016; Sathi Devi, 2022). These studies collectively shed light on the nuanced effects of PE on ocular blood flow, revealing that dynamic exercises can enhance choroidal blood flow, with systemic factors playing a lesser role compared to local factors such as nitric oxide in regulating this flow. Wylęgała’s research further elaborates on how both isometric and dynamic exercises influence IOP and ocular blood flow, suggesting potential benefits for conditions like glaucoma through the acute decrease in intraocular pressure observed with isometric exercise. Meanwhile, in 2022, Sathi Devi’s findings introduced a perspective on the relationship between exercise habits and the stiffness of ocular vessels, indicating that while aging increases vessel stiffness, regular exercise does not significantly alter this aspect of ocular circulation.

In addition to these findings, the work of Hayashi and Ikemura’s group offers critical insights into ocular blood flow, particularly about arteriole and macular blood flow. Their studies, which incorporate human data, provide valuable evidence that arteriole flow in the macular region is highly susceptible to age-related changes. Hayashi and Ikemura’s group have demonstrated that with increasing age, there is a significant decline in macular blood flow, contributing to the pathophysiology of age-related macular degeneration (Hayashi et al., 2011; Ikemura et al., 2022). However, they also report that regular PE can mitigate some of these age-related changes, promoting better blood flow in the macula and arterioles, thereby offering potential protective effects against ocular diseases. These findings emphasize the importance of maintaining an active lifestyle to preserve ocular health, especially as one age.

Moreover, it is crucial to consider the significant influence of blood pressure on ocular perfusion pressure (OPP), particularly during exercise. Blood pressure is known to fluctuate significantly with physical activity, which directly affects OPP, defined as the difference between IOP and mean arterial pressure. Increases in blood pressure during exercise can lead to elevated OPP, thus enhancing ocular blood flow. This relationship is vital for understanding the physiological mechanisms involved during PE, especially for individuals with ocular conditions like glaucoma. Therefore, the acute changes in blood pressure that occur during exercise should be incorporated into the discussion surrounding ocular blood flow, highlighting the interplay between systemic hemodynamics and ocular health (Hayashi et al., 2011).

In rodent studies, low-intensity treadmill exercise (at speeds of 0, 5, 10, or 20 m/min) was found to protect retinal function during light-induced retinal degeneration, suggesting an increase in ocular blood flow (Mees et al., 2019). Moreover, PE-induced effects in the retina have also been attributed to various mechanisms including improved vasodilation, enhanced nitric oxide production, and increased expression of pro-angiogenic factors, for example, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Gunga et al., 1999). Additionally, exercise-induced changes in autonomic nervous system activity play a significant role in regulating ocular blood flow (Sun et al., 2020). PE may promote an increase in OPP, which can in turn potentially increase blood flow throughout the intraocular vasculature and protect against ischemic damage in open-angle glaucoma (Li et al., 2019a). For instance, a study found that after short-term aerobic exercise, such as cycling at moderate intensity, IOP significantly decreased while OPP significantly increased (Ma et al., 2022). Other studies have also reported similar effects of PE on promoting ocular blood flow. For instance, research utilizing Doppler imaging techniques has shown that individuals engaged in regular aerobic exercises exhibit higher retrobulbar blood velocities compared to sedentary individuals (Zhao et al., 2017). Furthermore, studies using laser speckle flowgraphy have revealed increased optic nerve head and peripapillary vessel perfusion following acute bouts of moderate-intensity exercises (Liu et al., 2022).

Retinal neuroprotection

Acute exercise triggers immediate neuroprotective mechanisms, such as the activation of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase) and transient increases in neurotrophic factors like BDNF (He et al., 2020). In contrast, chronic exercise induces long-term adaptations, including sustained neurotrophic support, enhanced synaptic plasticity, and reduced chronic inflammation (Chu-Tan et al., 2022). These mechanisms contribute to the long-term preservation of retinal ganglion cells and photoreceptors, offering protection against progressive diseases such as glaucoma and AMD. Subsequently, in the context of the retina, the neuroprotective effects of PE can be categorized into four main aspects: cell survival, synaptic plasticity, inflammation reduction, and oxidative stress reduction.

Cell survival

PE has been suggested to promote cell survival in the retina by upregulating the expression of neurotrophic factors, such as BDNF (He et al., 2020) and GDNF (Kimura et al., 2015). These factors support the survival and function of RGCs and other retinal neurons, which are essential for maintaining proper visual function. In animal models, regular PE increases the levels of BDNF and GDNF in the retina, leading to enhanced RGC survival and reduced retinal degeneration in conditions such as glaucoma and AMD (Kim et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2022).

Synaptic plasticity

Synaptic plasticity refers to the ability of synapses to change their strength and connectivity in response to neuronal activity. PE has been shown to preserve synaptic integrity in the retina by maintaining the expression of synaptic proteins, such as postsynaptic density protein 95 (Chrysostomou et al., 2016). The study demonstrated that PE elicits neuroprotective effects in the retina primarily by preventing complement-mediated synapse elimination through a mechanism dependent on BDNF. Interestingly, in middle-aged mice, PE was found to protect the RGCs from dysfunction and cell loss following an acute injury. This protection was associated with the preservation of inner retinal synapses and reduced synaptic complement deposition. Specifically, PE maintained BDNF levels in the retina, which were otherwise decreased post-injury in non-exercised animals. The study confirmed the critical role of BDNF in this protective mechanism, as blocking BDNF signaling during exercise negated the protective effects on RGCs. It is also crucial to note that synaptic plasticity has been associated with the maintenance of night vision during retinal degenerative disease, suggesting a role in the resistance to retinal degeneration (Leinonen et al., 2020). Specifically, Leinonen et al. (2020) explored how the retina adapts to progressive photoreceptor degeneration, particularly in a mouse model of RP caused by the P23H mutation in rhodopsin. Furthermore, their study provides significant insights into the adaptive responses of the retina to photoreceptor loss, suggesting that homeostatic synaptic plasticity can preserve visual function during the early stages of retinal degenerative diseases like RP.

Anti-inflammation

Chronic inflammation is a major contributor to retinal degeneration and vision loss in conditions such as diabetic retinopathy and AMD (Tan et al., 2020; Kaur and Singh, 2023). PE has been shown to reduce retinal inflammation by modulating the expression of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines (Dantis Pereira de Campos et al., 2020; Cui et al., 2023). Regular physical activity can lead to a decrease in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6, and an increase in the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-10. This shift in cytokine balance can help to reduce retinal inflammation and protect retinal neurons from damage.

Reduction in oxidative stress

Oxidative stress, caused by an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species and the ability of the body to detoxify them, is another major contributor to retinal degeneration (Rohowetz et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019b). PE has been shown to reduce oxidative stress in the retina by enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (Kim et al., 2015). Increased antioxidant enzyme activity can help to neutralize reactive oxygen species and protect retinal cells from oxidative damage, which may contribute to the prevention or delay of retinal degeneration in conditions such as AMD and diabetic retinopathy. For example, the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems that are major antioxidant systems in mammalian cells exert functions in redox signaling regulation via modifying cysteines in proteins, thus protecting the retina from oxidative stress (Ren and Léveillard, 2022). Furthermore, astaxanthin, a potent antioxidant, has been shown to protect retinal photoreceptor cells against high glucose-induced oxidative stress by inducing antioxidant enzymes via the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway (Lai et al., 2020).

Effects of Physical Exercise on Specific Retinal Diseases

Glaucoma

The primary risk factor for glaucoma is elevated IOP. This ocular hypertension may contribute to neuronal damage by compressing the optic nerve and restricting blood flow (Cole et al., 2021). PE can significantly reduce both temporary and baseline IOP for extended durations (Zhu et al., 2018), indicating its potential as a strategy for RGC preservation, although direct evidence is still limited, particularly in animal studies. Individuals with low OPP are more prone to glaucomatous damage, and decreased levels of PE are strongly linked to lower OPP (Zhu et al., 2018). Indeed, in glaucoma, acute exercise primarily lowers IOP temporarily, but repeated chronic exercise offers more robust protection by improving ocular perfusion and reducing systemic risk factors (Zhu et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2022). In diabetic retinopathy, acute bouts of exercise can enhance glycaemic control temporarily, while chronic exercise interventions result in sustained reductions in oxidative stress and inflammation, delaying disease progression (Loprinzi and Joyner, 2016).

Age-related macular degeneration

A meta-analysis study involving multiple cohorts examined the influence of PE on the occurrence or progression of AMD. The research incorporated data from 14,630 adults who initially had no AMD or were in the early stages of the disease, gathered from seven population-based studies. The findings indicated that engaging in high levels of PE could serve as a protective factor against the onset of early AMD (Mauschitz et al., 2022) Epidemiological studies have also shown an inverse relationship between regular vigorous exercise in the past and intermediate AMD in women (McGuinness et al., 2016). Additionally, a clinical prospective cohort study involving participants with early or intermediate AMD found that increased PE was linked to a slower progression of the condition (Seddon et al., 2003). With regards to animal research, there is no direct evidence for PE-induced neuroprotection specifically in animal models of AMD. However, indirect evidence was provided in recent studies showing the neuroprotective effect of wheel running exercise in C57BL/6J mice (with the I307N rhodopsin-mutant mice) which shares some pathological features with AMD (Zhang et al., 2019; Bales et al., 2024). The study found that voluntary wheel running exercise partially protected against retinal degeneration, cell death, inflammation, and RPE disruption in these mice. Specifically, exercised mice showed preservation of retinal function and visual acuity, reduced photoreceptor cell death, mitigated inflammatory response, and reduced RPE disruption compared to non-exercised counterparts. These findings support the notion that PE can be an effective, non-invasive strategy to prevent and halt the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, including those affecting the retina like AMD.

Diabetic retinopathy

The positive impact of PE on diabetes has been widely acknowledged and explored in various studies. Research conducted by Reitman and his team analyzed six individuals with recent-onset diabetes, discovering that consistent aerobic exercise could reduce fasting plasma glucose levels and enhance oral glucose tolerance, thereby preserving glucose balance (Reitman et al., 1984). Another small-scale human study demonstrated that a single 45-minute cycling session could result in an immediate glucose-reducing effect (Zinman et al., 1984). Two comprehensive reviews (Peirce, 1999; Colberg et al., 2010) based on numerous studies have corroborated that PE not only ameliorates blood glucose management in type 2 diabetes, but also prevents or delays the disease’s progression. A higher level of PE is correlated with a reduced prevalence of diabetic retinopathy, as observed in the population-based Beijing Eye Study (Wang et al., 2019). Loprinzi and Joyner (2016) reported engaging in moderate levels of PE is associated with a significantly lower risk of developing moderate to severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. In a streptozotocin-induced diabetic model, treadmill exercise (30 minutes per day, five times a week, for 6 weeks) was found to decrease TUNEL-positive and caspase-3-positive cells, suppress pro-apoptotic protein Bax expression, and elevate anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and cell survival factor phospho-Akt in the rat retina (Kim et al., 2013). In a separate study by Allen et al. (2018), using the same method to establish a diabetic rat model, improved recovery following PE was observed through behavioral tests and electroretinogram assessments, with the tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB)-dependent pathway hypothesized to mediate the enhancement of visual and cognitive function.

Light-induced retinal degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa

Treadmill training preserves the structure and function of mouse retinas, as assessed by electroretinography, and influences the expression of the leukemia inhibitory factor gene following light-induced retinal degeneration (Chrenek et al., 2016). Additionally, low-intensity exercise might help reduce the effects of light-triggered retinal degeneration (Mees et al., 2019). In a related study, 2 weeks of treadmill exercise in mice improved retinal function and increased the number of photoreceptor nuclei (Lawson et al., 2014).

A previous study suggested that increased PE can improve self-reported visual function and quality of life for RP patients (Levinson et al., 2017). The rd10 mouse model, which carries an autosomal recessive mutation in rods, exhibits significant photoreceptor degeneration by postnatal day 18, making it a suitable RP model. Voluntary running has been shown to partially preserve retinal structure and delay vision loss due to photoreceptor death in this mouse strain, although this protective effect is reduced when a BDNF receptor antagonist is administered (Hanif et al., 2015). The I307N (also known as Tvrm4) mouse model represents an autosomal dominant form of RP, in which rod photoreceptors degenerate after exposure to brief, intense light. Voluntary wheel running partially reverses this degeneration, maintains visual function, and reduces retinal inflammation in this transgenic strain (Zhang et al., 2019).

Overall, both animal and human studies have indicated the neuroprotective effects of PE on the retina (Table 1).

Table 1.

Neuroprotective effects of PE in the ocular health of human and animal subjects

| Diseases | Study subjects | Gender; age | Exercise protocols | Study outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glaucoma | Human | Males; 45 yr and 54 yr | 10-km footrace | Lower likelihood of glaucoma diagnosis in active runners | Williams, 2009 |

| 2 males and 23 females; 18–23 yr | 1046-m walk at a brisk pace in a natural setting | Reduction in intraocular pressure (–1.4 mmHg) | Hamilton-Maxwell and Feeney, 2012 | ||

| AMD | Human | 77 males, 184 females; Aged 60 yr and older | PE performed three times per week | 25% decreased risk of advanced AMD among individuals with early or intermediate AMD | Seddon et al., 2003 |

| Human | 8281 males, 12,535 females; 40–69 years | Walking, frequent (≥ 3 times/wk) and less frequent (1–2 times/wk) vigorous and non-vigorous exercise | Lower odds of intermediate and late AMD | McGuinness et al., 2016 | |

| I307N Rhodopsin-mutant Mice | Male and female; 10–20 mon | Voluntary wheel running at a modest intensity | Partial protection against retinal degeneration and inflammation | Zhang et al., 2019 | |

| Diabetic Retinopathy | Human | 5278 females; 20–85 yr | Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. | Diminished likelihood of moderate/severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy | Loprinzi and Joyner, 2016 |

| Sprague-Dawley rats | 32 males; 7 wk | Treadmill exercise (30 min/d, 5 times a wk, for a duration of 6 wk) | Amelioration of diabetes-induced apoptosis in retinal cells by enhancing p-Akt levels | Kim et al., 2013 | |

| Type II Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat | 71 males; < 9 wk | Running wheels exercise at 3 wk of age; Assessments were done at 2 and 4 mon | Protection against early visual and cognitive dysfunction | Worthy et al., 2019 | |

| Light-induced RD and RP | Human | RP: 83 females, 60 males; Mean age: 46.9 yr | 9 yr (2005–2014) physical activity data collection using the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire | Greater self-reported visual function and quality of life in RP patients with increased physical activity | Levinson et al., 2017 |

| Light-induced RD BALB/cJ mice | 48 adult males | Treadmill exercise duration was 5 d per wk for 60 min each day at a rate of 10 m/min | Twice greater retinal function and photoreceptor nuclei than inactive mice exposed to bright light | Lawson et al., 2014 | |

| rd10 mice | RP: male and female; 4–6 wk | Voluntary exercise on free-spinning (active) or locked (inactive) running wheels | Partial protection against retinal degeneration and vision loss | Hanif et al., 2015 |

AMD: Age-related macular degeneration; PE: physical exercise; RD: retinal degeneration; RP: retinitis pigmentosa.

Potential Mediators of Exercise-Induced Retinal Neuroprotection

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

BDNF is a neurotrophin encoded by the bdnf gene in humans. It plays a crucial role in the survival, growth, differentiation, and maintenance of neurons in both the central and peripheral nervous systems (Huang and Reichardt, 2001). BDNF plays key roles in promoting adult neurogenesis and the repair of myelin (KhorshidAhmad et al., 2016). PE increases BDNF expression in the brain, particularly in the hippocampus, through the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α/neuronal fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 pathway and by altering the BDNF promoter (Sleiman et al., 2016). BDNF is predominantly found in the brain however, various retinal neurons, including RGCs, amacrine cells, astrocytes, retinal glial cells (Müller cells), and photoreceptors also express BDNF (Bennett et al., 1999; Afarid et al., 2020). Additionally, BDNF can be transported between the brain and retina through the optic nerve (Fudalej et al., 2021). BDNF also serves several crucial functions within the nervous system, such as guiding neural development, influencing synaptogenesis, and providing neuroprotection (Bathina and Das, 2015; Miranda et al., 2019; Colucci-D’Amato et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022). In the context of the retina, BDNF is essential for the development of vision signaling by fine-tuning the organization of RGC dendrites and ensuring the correct formation of the retinal structure (Fudalej et al., 2021). In mature individuals, endogenous BDNF offers neuroprotective benefits to RGCs by preserving dendritic fields and minimizing vision loss following ocular hypertension-induced damage. This protective effect has been observed in animal models of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (Domenici et al., 2014; Figure 1 and Table 2). Furthermore, BDNF plays a role in safeguarding retinal cells from injury caused by hypoxia and glucose deprivation (Vanevski and Xu, 2013).

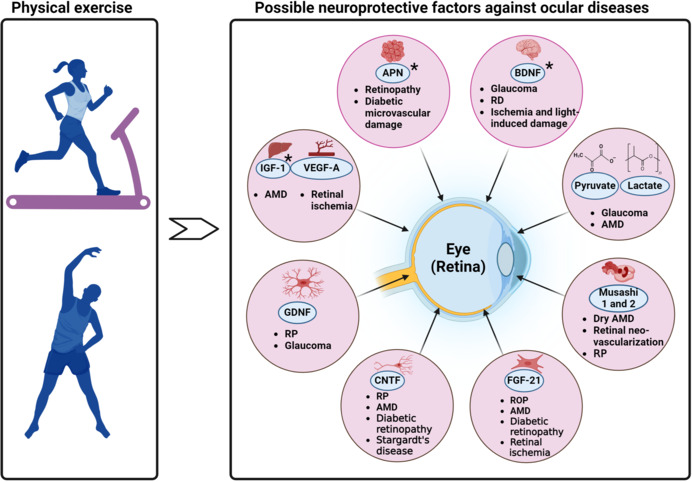

Figure 1.

Impact of physical exercise–induced neuroprotective factors on various ocular diseases.

*PE increases/potentially increases the level of adiponectin (APN), BDNF, and IGF-1. For the other neurotropic factors, PE potentially influences their levels however there is no direct mention of whether PE causes an increase or decrease in their levels. Created with BioRender.com. AMD: Age-related macular degeneration; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CNTF: ciliary neurotrophic factor; FGF-21: fibroblast growth factor-21; GDNF: glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor; IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor-1; PE: physical exercise; ROP: retinopathy of prematurity; RP: retinitis pigmentosa; VEGF-A: vascular endothelial growth factor-A.

Table 2.

Neuroprotective effects of possible neurotrophic factors in ocular diseases after physical exercise

| Neurotrophic factors | Ocular diseases | Neuroprotective effects |

|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin | Retinopathy and diabetic microvascular damage | Anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic properties, which may help in reducing inflammation and preventing abnormal blood vessel growth, potentially mitigating diabetic retinopathy and microvascular damage. |

| BDNF | Retinal degeneration, glaucoma, ischemia, light-induced damage | Exogenous application and increased expression of BDNF in retinal neurons using viral vector systems have been beneficial in promoting RGC survival. |

| Pyruvate and lactate | Glaucoma and AMD | Energy substrates for retinal cells and may protect against oxidative stress, potentially offering neuroprotection in glaucoma and AMD by supporting cellular metabolism and reducing oxidative damage. |

| Musashi 1 and 2 | Dry AMD, retinal neovascularization, and RP | Direct neuroprotective effects on the retina are not well-documented. Could contribute to retinal cell maintenance and repair, which may be beneficial in conditions like dry AMD and RP. |

| FGF-21 | ROP, AMD, diabetic retinopathy, retinal ischemia | Metabolic and cytoprotective effects, which may help in reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, potentially offering protection against various forms of retinopathy and retinal ischemia. |

| CNTF | RP, AMD, diabetic retinopathy, Stargardt’s disease | Potent neuroprotective cytokine in multiple models of retinal degeneration. |

| Enhances glycolysis and anabolism in degenerating retinas, improves the morphology of photoreceptor mitochondria, and restores key antioxidants to wild-type levels. | ||

| GDNF | RP and glaucoma | May support the survival and function of RGCs, potentially offering benefits in conditions like RP and glaucoma. |

| IGF-1 | AMD | Implicated in retinal health, promoting cell survival and vascular stability, which may help in reducing the progression of AMD. |

| VEGF-A | Retinal ischemia | Primarily known for its role in angiogenesis, but it also has neuroprotective properties that may help in reducing ischemic damage to retinal cells. |

AMD: Age-related macular degeneration; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CNTF: ciliary neurotrophic factor; FGF-21: fibroblast growth factor-21; GDNF: glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor-1; ROP: retinopathy of prematurity; RP: retinitis pigmentosa; VEGF-A: vascular endothelial growth factor-A.

With regards to PE, BDNF has been identified as a potential mediator of exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection in various studies that reported a significant decrease in photoreceptor cell death and preserved retinal structure and function (Lawson et al., 2014; Hanif et al., 2015; Allen et al., 2018; Mees et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Another study found that treadmill exercise promoted increased retinal astrocytic population, glial fibrillary acidic protein expression, branching and endpoints, dendritic complexity, and BDNF-astrocyte interaction in a light-induced retinal degeneration mouse model (Bales et al., 2022). The beneficial effects of exercise were seen together with increased levels of BDNF in both the body and the retina. These benefits required the activation of BDNF’s specific receptor, TrkB (Lawson et al., 2014; Allen et al., 2018). Rodent models of neurodegeneration have shown that BDNF and TrkB are present in both neurons and astrocytes (Ohira et al., 2007; Koppel et al., 2018; Holt et al., 2019; Fernández-García et al., 2020). Imbalances in neurotrophins and/or their high-affinity Trk receptors have been documented in neurodegenerative diseases (Dorsey et al., 2006; Vidaurre et al., 2012). Specifically, reduced expression of BDNF and increased expression of TrkB’s truncated isoform, TrkB.T1, have been linked to neuronal cell death and disease severity in the mature central nervous system (Dorsey et al., 2006; Vidaurre et al., 2012; Fernández-García et al., 2020). Neuronal cell death associated with upregulated expression of TrkB.T1 can be rescued by overexpression of the full-length, catalytically active isoform of TrkB (TrkB.FL) (Dorsey et al., 2006).

Exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection, mediated by BDNF, holds potential clinical implications for preventing and treating retinal degenerative diseases, such as AMD, RP, and glaucoma (Bales et al., 2022; Figure 1 and Table 2). It may also offer neuroprotection following ischemic injury, enhance retinal function by promoting cell survival and function, and serve as a complementary therapy alongside existing treatments like gene therapy, stem cell therapy, or pharmacological interventions (Bales et al., 2022; Sayyah et al., 2022; Gibbons et al., 2023). Furthermore, a deeper understanding of the role of BDNF in exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection could lead to the development of personalized exercise programs tailored to optimize neuroprotective effects for individuals with specific retinal conditions or those at risk of developing retinal degenerative diseases.

Adiponectin

Adiponectin (APN) is a hormone secreted predominantly by adipocytes (Kim et al., 2007), but it may also be secreted locally by the retina (Lin and Kuo, 2013) and brain (Thundyil et al., 2012). In the brain, APN is thought to improve brain plasticity by regulating intracellular energetic activity (Formolo et al., 2022). APN plays a significant role in the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism (Tao et al., 2014), and exhibits anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic properties (Ohashi et al., 2012). Recent research has identified the presence of APN and its receptors (AdipoR1 and AdipoR2) in the retina (Yamauchi et al., 2014), suggesting their potential involvement in retinal physiology and pathology. Studies that explore the presence of APN in the retina (Lin et al., 2013) and eyes (Li et al., 2013) largely focus on its role in diabetic retinopathy, AMD, photoreceptor integrity, RP, retinopathy of prematurity, and hypoxia-mediated retinal neovascularization (Figure 1 and Table 2). For example, APN and its receptors are expressed in the RPE and photoreceptor cells (Li et al., 2019a), indicating a possible role in photoreceptor function and RPE-photoreceptor interaction. Additionally, APN protects retinal neurons from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis (Bushra et al., 2022), highlighting its neuroprotective effects. In the context of diabetic retinopathy, a common microvascular complication of diabetes, decreased levels of APN have been observed (Deng et al., 2023), suggesting a potential link between APN and the development of this condition. Moreover, APN has been reported to inhibit retinal inflammation and neovascularization, two key features of diabetic retinopathy, by suppressing the expression of VEGF and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (Choubey and Bora, 2023). In a separate study, using the model of laser-induced neovascularization in choroid in mice, APN peptide II was reported to reduce the extent of choroidal neovascularization mouse model of neovascular AMD (Davis et al., 2012). Collectively, the aforementioned findings indicate that APN and its receptors play a crucial role in retinal health and may serve as potential therapeutic targets for retinal diseases.

Numerous studies indicate that PE can enhance the production of APN (Yau et al., 2014; Micheli et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Various clinical investigations have demonstrated that engaging in physical activity can elevate APN levels in both plasma (Yau et al., 2014; Micheli et al., 2018) and adipose tissue (Becic et al., 2018) in humans. In a mouse study, it was found that exercise increased APN concentrations in the hippocampus, promoting neurogenesis and exhibiting anti-depressive effects (Yau et al., 2014). Consequently, PE may provide beneficial outcomes by modulating the expression of APN.

In the context of the retina, APN is a potential mediator for exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection due to its neurotrophic and neuroprotective properties, its role in regulating intracellular energetic activity, and its involvement in the APN/AdipoRs signaling pathway. The possible mechanisms by which exercise induces APN neuroprotection of the retina are multifaceted and involve several pathways including anti-inflammatory and antioxidative mechanisms (Schön et al., 2019; Polito et al., 2020; Choubey and Bora, 2023), modulation of barrier permeability and activation of neuroprotective pathways (Wang et al., 2020). However, further research is warranted to know the exact mechanisms by which APN contributes to retinal neuroprotection and how PE can be leveraged to promote eye health.

Insulin-like growth factor-1

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) is a hormone that plays a crucial role in cell growth, development, and survival. In the brain, IGF-1 has been reported to have potential therapeutic effects in neurodegenerative diseases related to metabolic syndrome, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. IGF-1 modulates synaptic plasticity, neurotransmission, and neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Interestingly, it was demonstrated that a lack of serum IGF-1 triggered cognitive impairment and depressive behavior (Carro et al., 2003), while reduced Igf-1 gene expression with aging was linked to cognitive decline (Hadem and Sharma, 2017). PE has been reported to increase the levels of IGF-1 in the hippocampus, and the high blood-brain barrier permeability of IGF-1 allows serum IGF-1 to access the brain (Carro et al., 2003). Moreover, PE can also attenuate neurodegeneration or neuropathological behaviors by altering cytokine production, which indirectly restores normal IGF-1 levels (Mee-inta et al., 2019).

In the retina, IGF-1 has been found to have several effects. It acts as a potent proangiogenic factor present in the neovascular membranes of AMD patients, and elevated concentrations of IGF-1 have been detected in the plasma of these patients (Biadgo et al., 2020; Figure 1 and Table 2). Additionally, transgenic mice overexpressing IGF-1 in the retina have been shown to progressively develop retinal neovascularization, which is associated with rubeosis iridis (Bailes and Soloviev, 2021). IGF-1 also affects ocular growth and development, epithelial proliferation, retinal angiogenesis, and inflammation (Puche and Castilla-Cortázar, 2012). IGF-1 receptor is expressed in the retina and photoreceptor neurons, and it has been suggested to mediate photoreceptor neuroprotection (Wrigley et al., 2017). Furthermore, IGF-1 promotes retinal cell proliferation through the activation of multiple signaling pathways (Al-Samerria and Radovick, 2021).

PE has been shown to have a positive relationship with IGF-1 levels in both human and animal studies. Regular PE can increase IGF-1 levels, which in turn can have various health benefits. In elderly individuals, PE has been implicated in increased IGF-1 levels and improved cognition (Stein et al., 2018). This relationship suggests that engaging in regular PE may help maintain cognitive function in older adults. Moreover, IGF-1 levels have been associated with a reduced risk of hypertension, and PE has been shown to reverse IGF-1 deficiencies in microvascular rarefaction and hypertension (Norling et al., 2020). Several animal studies have demonstrated a positive increase in IGF-1 levels following PE interventions. For example, a study was conducted to examine the impact of moderate swimming training on the GH/IGF-1 growth axis and tibial mass in diabetic rats. The study revealed that swimming training promoted bone mass and stimulated the GH/IGF-1 axis in diabetic rats (Gomes et al., 2006). Another study examined the role of swimming training on cerebral metabolism and hippocampus concentrations of insulin and IGF-1 in diabetic rats. The research concluded that physical training-induced important metabolic and hormonal alterations associated with improved glucose homeostasis and increased activity in the systemic and hippocampus IGF-1 peptide (Gomes et al., 2009).

Given the above findings, it is possible that IGF-1 could serve as a mediator of PE-induced retinal neuroprotection. However, further research is warranted to establish a direct link between IGF-1 and PE-induced retinal neuroprotection specifically.

Ciliary neurotrophic factor

Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) is a member of the interleukin-6 cytokine family and has potent neuroprotective properties for neurons. The CNTF receptor complex, which consists of CNTF receptor-α (CNTFRα), gp130, and the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor, is responsible for binding CNTF. When the receptor complex binds, it activates several signaling pathways, including the Janus kinases/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK, and PI3K/Akt pathways (Ernst and Jenkins, 2004). These pathways modulate gene expression, promoting neuronal regeneration in both mice and zebrafish (Smith et al., 2009; Elsaeidi et al., 2014). When the CNTF gene is removed in mice, it leads to motor neuron degeneration and hastened decline in inflammatory demyelinating diseases (Masu et al., 1993; Linker et al., 2002). Conversely, mice deficient in CNTFRα have a short lifespan, dying soon after birth (DeChiara et al., 1995). In a study that focused on the targeted delivery of CNTF in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease, researchers discovered that using cell-based methods to administer CNTF prevents the deterioration of synapses and improves memory function (Garcia et al., 2010). This study highlights the potential therapeutic role of CNTF in neurodegenerative diseases. With regards to PE, there is limited information specifically about the increase in CNTF after PE. However, several studies have shown a relationship between CNTF and exercise. For example, research investigating the impact of resistance training on muscle strength, endurance, and motor unit discovered that the outcomes differed based on the CNTF gene polymorphism (Hong et al., 2014). Furthermore, a study of 494 healthy men and women across the entire adult age span (20–90 years) demonstrated that CNTF genotype is associated with muscular strength and quality in humans (Roth et al., 2001). About a sedentary life-style, another study revealed that the levels of CNTF were found to be elevated in the blood plasma of individuals suffering from obesity and these levels showed a correlation with indices of diabetes and inflammation (Perugini et al., 2022). Although the above studies do not directly show an increase in CNTF after PE, it suggests that CNTF might play a role in the response to PE.

The relationship between CNTF and PE warrants further investigation, as it may provide insights into the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of PE on the CNS, particularly the retina. CNTF has been shown to have beneficial effects on retinal neurons in various studies. CNTF is expressed by various cells in the retina, particularly Müller glia (Kirsch et al., 1997), and is one of the most extensively researched neurotrophic factors for protecting neurons in retinal diseases. CNTF has demonstrated significant potency in preventing photoreceptor loss in multiple animal models of retinal disease, such as RP (Tao et al., 2002; Rhee et al., 2013). Additionally, CNTF has been shown to protect against RGC death in models of glaucoma and ischemic optic neuropathy (Pease et al., 2009; Mathews et al., 2015). In a recent study, researchers used mice as their animal model to investigate the influence of CNTF on metabolism in a mouse model of photoreceptor degeneration (Do Rhee et al., 2022; Figure 1 and Table 2). The study revealed that CNTF treatment alters the morphology of rod photoreceptor mitochondria in the degenerating mouse retinas. The results obtained suggested that CNTF treatment has a significant effect on the metabolic condition of degenerating retinas by fostering aerobic glycolysis and increasing anabolic activities (Dittrich et al., 1994; Figure 1 and Table 2). CNTF’s neuroprotective effectiveness has led to the concept of its clinical application. However, systemic administration of CNTF does not efficiently reach the CNS (Zhang et al., 2011). Consequently, direct application to the necessary site is preferred. Intriguingly, CNTF delivery through encapsulated cell implants has been examined in clinical trials for treating RP and geographic atrophy, an advanced form of dry AMD (Sieving et al., 2006; Birch et al., 2013, 2016). This technology’s application may also be advantageous for glaucoma treatment. Besides its neuroprotective effects, CNTF can stimulate axonal regeneration (Fischer and Leibinger, 2012). Inflammation is known to promote optic nerve regeneration (Benowitz and Popovich, 2011), and it has been reported that inflammatory stimulation increases CNTF levels in retinal astrocytes, which then act on RGCs to encourage axonal regeneration (Müller et al., 2007). Within the CNTF signaling pathways, the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) serves as a negative regulator for the JAK/STAT pathway (Babon and Nicola, 2012). Removing SOCS3 in RGCs leads to substantial axonal regeneration following optic nerve injury (Smith et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2011). Remarkably, combining SOCS3 deletion with other factors related to axonal regeneration, including CNTF, resulted in the formation of functional synapses and the recovery of visual function in an optic tract injury model (Bei et al., 2016). These findings provide promising prospects for neural repair research and raise expectations for visual restoration and functional recovery in other CNS conditions associated with axon degeneration or injury.

Glial-derived neurotrophic factor

GDNF is part of the GDNF family and is distantly related to the transforming growth factor-β superfamily. GDNF signals through a receptor complex composed of multiple components, including the GPI-anchored receptor GFRα1 and the transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase RET (Airaksinen and Saarma, 2002). GDNF has been reported to have powerful neuroprotective effects on the brain. Initially, GDNF was identified as a potent neurotrophic factor necessary for promoting the survival of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. However, GDNF-deficient mice exhibit only minor deficits in the CNS and peripheral nervous system, while displaying severe deficits in the enteric nervous system and kidney agenesis, leading to death shortly after birth (Sánchez et al., 1996). The neuroprotective effects of GDNF on various neurons suggest its potential as a therapeutic candidate for neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (Budni et al., 2015; Kramer and Liss, 2015).

PE has been shown to have a positive relationship with the expression of GDNF in the nervous system. A rodent study demonstrated that short-term PE increased GDNF protein content in the lumbar spinal cord of both young and old rats (McCullough et al., 2013). Involuntary running resulted in the greatest change in GDNF protein levels, followed by swimming and voluntary running (McCullough et al., 2013). Another study showed that PE enhanced functional recovery and expression of GDNF after photochemically induced cerebral infarction in rats (Harada et al., 2003). Although the exact mechanisms underlying the relationship between PE and GDNF expression are not fully understood, these findings suggest that PE may play a role in promoting neuroprotective effects through the regulation of GDNF levels in the nervous system. This could have potential implications for maintaining a healthy motor nervous system and developing therapies for individuals with neurodegenerative diseases.

In the retina, GDNF has been found to support photoreceptor survival during retinal degeneration. Recent research indicates that long-lasting expression of GDNF in photoreceptors or retinal pigment epithelial cells, using the tetracycline-On inducible expression system, decelerates photoreceptor degeneration in rd10 mice (Ohnaka et al., 2012). Interestingly, it has been discovered that in the porcine retina, GFRα1 and RET are present in Müller glia, but not in photoreceptors (Harada et al., 2003). However, when GDNF is applied to cultured mouse Müller glia, it increases the levels of BDNF, basic fibroblast growth factor, and GDNF itself. These observations imply that GDNF may provide neuroprotection to photoreceptors indirectly through the stimulation of glial cells. Moreover, GDNF has been shown to safeguard RGCs following optic nerve transection and retinal ischemia (Kyhn et al., 2009). In a spontaneous glaucoma model using DBA/2J mice, the administration of an intravitreal injection containing GDNF-loaded microspheres led to a significant improvement in long-term RGC survival (Ward et al., 2007). GDNF delivered through microspheres also promoted RGC survival in an experimental glaucoma model (Checa-Casalengua et al., 2011).

Overall, GDNF offers neuroprotective effects directly and/or indirectly via glia, making it a promising therapeutic candidate for retinal diseases, especially RP and glaucoma. GDNF has been observed to increase the expression of the glutamate/aspartate transporter (GLAST) in Müller glia, a process necessary for RGC protection after optic nerve transection (Koeberle and Bähr, 2008). Prior studies have demonstrated that GLAST deficiency (GLAST KO mice) leads to spontaneous RGC death and optic nerve degeneration without elevated IOP, thus resembling the pathological features seen in normal tension glaucoma (Harada et al., 2007). GLAST is expressed in Müller glia and is crucial for maintaining extracellular glutamate concentration below neurotoxic levels (Harada et al., 1998). As a result, neighboring neurons are shielded from excitotoxic damage. The transport of glutamate into Müller glia is also essential for the synthesis of glutathione, a major cellular antioxidant in the retina. In GLAST KO mice, glutathione levels are reduced in the retina, particularly in Müller glia (Harada et al., 2007). Decreased glutathione levels have also been detected in the blood of glaucoma patients (Gherghel et al., 2005, 2013). Therefore, GLAST KO mice serve as an appropriate model for normal tension glaucoma and have contributed valuable insights into potential therapeutic approaches for this condition (Harada et al., 2010; Kimura et al., 2015). These findings emphasize the crucial roles of GLAST in supporting the survival of injured RGCs and propose that GLAST impairment could play a part in the development of glaucoma (Figure 1 and Table 2). Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that exercise can increase glutathione levels. Regular physical activity, including cardio and weight training, has been associated with increased glutathione levels. For example, a study indicated that aerobic exercise training, circuit weight training, and a combination of both resulted in significant increases in resting glutathione and the glutathione-glutathione disulfide ratio (Elokda and Nielsen, 2007). Another source also reported that regular exercise training leads to an increase in resting levels of glutathione as an adaptive response by the body (Kerksick and Willoughby, 2005).

Vascular endothelial growth factor

VEGF, a hypoxia-induced protein, plays a critical role in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. PE has been noted to increase VEGF levels and angiogenesis in the brain through the lactate receptor hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1 (HCAR1) (Voss et al., 2013; Maass et al., 2016; Morland et al., 2017). Moreover, it is hypothesized that exercise-induced VEGF in the periphery can cross the blood–brain barrier to mediate neurogenesis and angiogenesis in the CNS. VEGF has been shown to induce angiogenesis in the brain (Nieto et al., 2001; Nag et al., 2019). Other pioneering studies report beneficial effects of VEGF on the survival of newborn neuronal precursors and promotion of neurogenesis after cerebral ischemia and neurite outgrowth (Jin et al., 2002, 2006; Sun et al., 2003; Widenfalk et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2007). Additionally, VEGF has key implications in increasing the size of the subventricular zone (Gotts and Chesselet, 2005). Interestingly, inhibition of VEGF expression following injury potentially exacerbates outcome (Sköld et al., 2006). Aside from the brain, VEGF also has neuroprotective effects in the retina. VEGF-A, a specific isoform of VEGF, has been shown to have a direct neuroprotective effect on retinal neurons (Foxton et al., 2013). VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR2) is expressed in several neuronal cell layers of the retina, and functional analyses have demonstrated that VEGFR2 is involved in retinal neuroprotection (Nishijima et al., 2007). VEGF-A has been found to play a role in the adaptive response to retinal ischemia and acts as a maintenance factor for retinal neurons (Nishijima et al., 2007). In models of experimental glaucoma, VEGF-A has been shown to act directly on RGCs to promote survival. VEGFR2 signaling via the phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt pathway was required for the survival response in isolated RGCs (Foxton et al., 2013). Some studies have provided contrasting views of VEGF-induced retinal neuroprotection. Such studies have implicated VEGF in the pathogenesis of various retinal diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy and AMD (Wallsh and Gallemore, 2021; Arrigo et al., 2022). Nonetheless, the neuroprotective role of VEGF in the retina is also important to consider. In fact, other studies have suggested that anti-VEGF therapies may have negative effects on the retinal nerve fiber layer, which is primarily composed of RGC axons (Froger et al., 2020). Thus, the use of anti-VEGF therapies for retinal diseases should be carefully considered due to the potential negative effects on the nerve fiber layer.

With regard to PE, the relationship between VEGF and exercise in retinal diseases has not been fully explored. One study found that PE alleviates neovascular AMD by inhibiting AIM2 inflammasome in myeloid cells (Cui et al., 2023; Figure 1 and Table 2). Although the study does not directly address the relationship between VEGF and exercise, it suggests that PE could have a positive impact on retinal health in the context of AMD. Consequently, the exact relationship between VEGF and exercise in the context of retinal diseases requires further research.

Pyruvate and lactate

As end products of glycolysis, both pyruvate and lactate serve as crucial energy sources for various cells and tissues, including neurons. Although pyruvate is primarily generated from glucose breakdown via glycolysis, it can be converted into either acetyl-CoA (entering the Krebs cycle) or lactate. While pyruvate has long been acknowledged as a beneficial glycolysis-derived product, lactate production was initially considered a waste product due to oxygen deficiency in exercising muscle cells. However, numerous studies have shown that the L-enantiomer of lactate is produced under aerobic conditions.

In mammals, L-lactate serves as a crucial energy source for the process of gluconeogenesis and functions as a signaling molecule with autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine-like effects. Lactate is recognized as a vital energy source for neurons in the CNS. The monocarboxylate transporter 1 enables lactate transport through the blood–brain barrier and the inner and outer blood–retina barrier in a concentration-dependent manner (Hosoya et al., 2001; Brooks, 2020). There is ongoing debate about whether retinal ganglion cells prefer lactate or glucose as their primary energy source. In vitro studies have shown that retinal ganglion cells can utilize glucose, lactate, or pyruvate as energy sources (Wood et al., 2005; Casson et al., 2021).

The relationship between lactate, pyruvate, and retinal neuroprotection is not yet fully understood. However, some studies suggest that lactate and pyruvate may play important roles in retinal metabolism and neuroprotection (Figure 1 and Table 2). Pyruvate metabolism is suggested to be important in retinal ganglion cells across various species due to the high levels of MPC1 and MPC2 (Harder et al., 2020). In the vascularized retina, photoreceptors express high levels of lactate dehydrogenase A (which converts pyruvate into lactate), indicating the capacity for photoreceptors to convert pyruvate to lactate. This could provide energy for photoreceptors and allow them to serve as valuable lactate providers for other retinal cells (Grenell et al., 2019; Casson et al., 2021). Müller cells are believed to have a significant function in transporting lactate from photoreceptors to the inner parts of the retina. This process can occur directly, as evidenced by the existence of various monocarboxylate transporter receptors on Müller cells, or through glucose resulting from glycogen breakdown (Chidlow et al., 2005; Hurley et al., 2015). Interestingly, lactate also seems to be a favored energy source for Müller cells, promoting their survival when provided exogenously (Vohra et al., 2018). The metabolism of lactate by Müller cells could offer a vital backup system in case of reduced retinal ganglion cell metabolism.

A previous study has highlighted the neuroprotective properties of pyruvate in experimental neurodegeneration models (Li et al., 2019b). Additionally, pyruvate has been found to decrease oxidative stress in a retina model cultured ex vivo (Hegde and Varma, 2008). The neuroprotective effects of both lactate and pyruvate on retinal ganglion cells have been observed in cell-culture models, including during glucose deprivation (Vohra et al., 2019; Harder et al., 2020). Further research is needed to explore the potential of pyruvate as a neuroprotective treatment for ocular disorders such as glaucoma. With one clinical study currently underway (De Moraes et al., 2022).

Concerning the connection between PE and lactate, it has been proposed that exercise-induced neuroprotection could be facilitated by increased lactate levels, which subsequently affect BDNF secretion. In this regard, numerous studies have utilized blood lactate to monitor exercise intensity, and these investigations have found that higher lactate concentrations correlate with increased BDNF plasma and/or serum levels (Pasquale and Kang, 2009; Van Bergen et al., 2015; Shaafi et al., 2016; Müller et al., 2020). Despite the proposed ocular neuroprotective effects of lactate, it has been reported that intense PE such as ultramarathons can lead to increased lactate production, which, in the specific environment of the cornea, contributes to corneal edema (Moshirfar et al., 2018). This condition arises due to a disruption in the normal regulatory mechanisms of the corneal endothelium, influenced by factors such as enhanced glycolysis, oxidative stress, and environmental conditions like UV exposure and hypoxia at high altitudes. Moreover, in another study it was observed that mice subjected to the same exercise routine previously demonstrated to protect photoreceptor function, morphology, and visual function did not exhibit increased serum lactate concentrations (Sellers et al., 2019). The researchers proposed that elevating circulating lactate levels might not be essential for exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection. Nevertheless, it will be worthwhile for future research to explore the impact of PE on lactate shuttles between photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelial cells. For example, locally released lactate could safeguard neighboring retinal neurons and photoreceptor cells by serving as an energy source for maintaining bioenergetic needs and acting as signal mediators, potentially by binding receptors and initiating second messenger cascades (Vohra et al., 2019; García-Bermúdez et al., 2021).

Musashi-1 and Musashi-2

Musashi proteins Musashi-1 and Musashi-2 (MSI1 and MSI2) are RNA-binding proteins that play essential roles in stem cell maintenance, cell fate determination, and neural development. In the retina, they have been found to be crucial for photoreceptor morphogenesis and vision (Sundar et al., 2021). Photoreceptor cells express high levels of MSI1 and MSI2, indicating their importance in vision (Murphy et al., 2016; Matalkah et al., 2022). Combined knockout of Msi1 and Msi2 in mature photoreceptor cells leads to the loss of retinal response to light and progressive photoreceptor cell death (Matalkah et al., 2022). In photoreceptor cells, Musashi proteins perform distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic functions. In the cytoplasm, MSI1 and MSI2 act as activators of protein expression (Matalkah et al., 2022). In the nucleus, they promote the splicing of photoreceptor-specific alternative exons (Murphy et al., 2016). Photoreceptor cells express a characteristic splicing program that affects a broad set of transcripts and is initiated prior to the development of the light-sensing outer segments. The loss of MSI1 and MSI2 in photoreceptor cells results in disrupted photoreceptor outer segment morphology, ciliary defects, and impaired retinal response to light (Murphy et al., 2016). This suggests that Musashi proteins play a critical role in the morphogenesis of terminally differentiated photoreceptor neurons, which is in contrast to their canonical function in the maintenance and renewal of stem cells (Figure 1 and Table 2).

Although Musashi proteins have not been directly linked to exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection, their roles in neural development and maintenance suggest that they might be involved in the underlying mechanisms. For example, MSI1 has been shown to regulate the translation of target mRNAs, including those encoding for proteins involved in neural stem cell maintenance and differentiation. Similarly, MSI2 has been implicated in the regulation of neural stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Given the importance of BDNF in exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection, Musashi proteins might be involved in the regulation of BDNF expression or function. For example, Musashi proteins could modulate the translation of BDNF mRNA or other mRNAs encoding for proteins involved in BDNF signaling. Alternatively, Musashi proteins might interact with other factors that regulate BDNF expression or function, thereby indirectly influencing the neuroprotective effects of exercise on the retina. Further research is needed to elucidate the precise roles of Musashi proteins in exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection and to explore their potential as therapeutic targets for retinal degenerative diseases.

Fibroblast growth factor 21

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is a hormone produced primarily in the liver, but it is also expressed in other tissues such as adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and the pancreas (Matsui et al., 2022). It is involved in glucose and lipid metabolism, helping to regulate blood sugar levels and lipid balance in the body (Matsui et al., 2022). FGF21 exerts its effects by binding to specific receptors on target cells, activating intracellular signaling pathways that regulate various metabolic processes (Ma et al., 2021). In adipose tissues, FGF21 promotes the browning of white adipose tissue, a process that increases energy expenditure and may help combat obesity and its related risk factors (Haghighi et al., 2022).

PE has been shown to affect FGF21 levels, with different types of exercise such as high-intensity interval training and high-intensity resistance training promoting favorable changes in body composition and FGF21 levels (Haghighi et al., 2022). Indeed, it has been demonstrated that both high-intensity interval training and high-intensity resistance training significantly increased serum levels of Irisin and FGF21 and reduced the percentage of body fat and body weight compared to the control group (Haghighi et al., 2022). This study suggests that different types of exercise can promote favorable changes in body composition and FGF21 levels, which are critical for adipose tissue browning and glucose regulation (Haghighi et al., 2022). Exercise training has been shown to help reduce cardiac fibrosis and improve heart function following a myocardial infarction (Ma et al., 2021). The study discovered that both aerobic exercise training and resistance exercise training significantly improved cardiac function and reduced fibrosis. Additionally, these types of exercise increased the expression of FGF21 protein and hindered the activation of the transforming growth factor-β1-Smad2/3-MMP2/9 signaling pathway (Ma et al., 2021).

Although the direct relationship between FGF21 and exercise-induced retinal neuroprotection has not been explicitly studied, there is evidence to suggest that FGF21 may play a role in exercise-induced benefits on the retina. For example, a study assessed early optical coherence tomography angiography changes in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes and correlated them with diabetes duration, glycemic control, and FGF21 levels (Sherif et al., 2023). This study highlights the potential role of FGF21 in retinal health and its relationship with glucose regulation. Another study reported that in a mouse model of retinal ischemia caused by cardiovascular diseases, pemafibrate treatment enhanced liver function, elevated serum levels of FGF21, and protected against retinal dysfunction (Lee et al., 2021). Again, this study suggests that FGF21 might have a neuroprotective role in the eye and could be a potential therapeutic target for retinal ischemia (Figure 1 and Table 2). Additionally, several studies have demonstrated that FGF21 plays a significant role in maintaining retinal vascular health and may offer therapeutic potential for retinal diseases characterized by neovascularization and vascular leakage. For example, one study found that pemafibrate and fenofibrate, which increase plasma FGF21 concentration, can suppress the expression of VEGF-A, a protein that promotes pathological neovascularization in the retina (Tomita et al., 2019). This suggests that FGF21 may help prevent the development of abnormal blood vessels in the retina, which is a key feature of diabetic retinopathy. Another study demonstrated that FGF21 administration promoted physiological retinal vessel growth in a mouse model of Phase I retinopathy of prematurity, while FGF21 deficiency suppressed this growth (Figure 1 and Table 2). The study also found that FGF21 increased serum APN levels and modulated lipid oxidation in mitochondria, which are mechanisms that may underlie its effects on retinal vascularization (Fu et al., 2023). Moreover, research has shown that long-acting FGF21 can inhibit retinal vascular leakage in both in vivo and in vitro models, which is relevant for conditions that involve blood-retinal barrier breakdown, such as diabetic retinopathy (Tomita et al., 2020). Lastly, a correlation was observed between serum FGF21 levels and the severity of diabetic retinopathy, suggesting that FGF21 may be involved in the progression of this retinal disease (Lin et al., 2014).

While the aforementioned studies provide some insights into the potential implications of FGF21 for treating retinal diseases, more research is needed to establish a direct link between FGF21 and PE in promoting retinal health, as well as to explore their potential therapeutic applications in retinal diseases.

Conclusion

In summary, there are significant neuroprotective effects of PE on ocular diseases, such as glaucoma, AMD, RP, and diabetic retinopathy. The underlying mechanisms of these effects involve the modulation of neurotrophic factors, and improvements in intraocular pressure and ocular blood flow. The impact of PE on ocular health is dependent on the type, intensity, and duration of PE, with aerobic exercise and resistance training showing promising results in reducing intraocular pressure and promoting ocular blood flow. Furthermore, the benefits of PE appear to be more pronounced in individuals with ocular diseases compared to healthy subjects. By promoting PE as a complementary approach to traditional treatments, healthcare professionals can potentially improve the quality of life and visual outcomes for patients with ocular disorders. Further research is needed to elucidate the optimal exercise regimens and to explore additional mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of PE on ocular health.

Lastly, while there are significant neuroprotective effects of PE in the retina and potential benefits in preventing or ameliorating diseases like glaucoma, AMD, and diabetic retinopathy, it is also important to consider the less frequent but notable risks such as ultramarathon-induced corneal edema. This balanced view not only provides a comprehensive understanding of the impact of PE on ocular health but also emphasizes the importance of appropriate protective measures. For instance, athletes participating in high-endurance sports might benefit from protective eyewear to shield against environmental factors and strategies to manage and monitor lactate levels effectively. These precautions can help mitigate the risk of conditions such as ultramarathon-induced corneal edema, ensuring that the pursuit of physical fitness does not inadvertently compromise ocular health.

Future Directions

To further explore the benefits of PE in ocular diseases and to better understand the specific mechanisms of PE-induced neuroprotection in ocular diseases, future research should focus on the following areas:

Investigate the causality of reduced PE levels in ocular diseases: Determine whether visual impairment leads to restrictions in PE or if diminished exercise performance triggers the development of ocular diseases.

Identify novel mediators of PE-induced retinal neuroprotection: Expand the understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in PE-induced neuroprotection in ocular diseases.

Conduct preclinical and clinical studies: Develop and test interventions that incorporate PE as a therapeutic strategy for ocular diseases, and assess their efficacy in improving visual function and preventing disease progression.

Explore the role of genetic factors: Investigate how genetic factors, such as the Val66Met mutation, APOEε4 allele carriers, and methyl CpG binding protein 2, influence the effect of PE on neuroprotection in ocular diseases.

Examine the possible interaction between exercise and baseline fitness, as well as determine the optimal exercise parameters—intensity, duration, and type—that promote neuroprotection in ocular diseases.

By addressing these research gaps, the scientific community can gain a deeper understanding of the role of PE in ocular health and develop novel therapeutic strategies to prevent and treat ocular diseases.

Funding Statement

Funding: This project was supported by the InnoHK Initiative and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government, China (to SYY).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

C-Editors: Zhao M, Liu WJ, Qiu Y; T-Editor: Jia Y

Data availability statement:

Not applicable.

References

- Afarid M, Namvar E, Sanie-Jahromi F. Diabetic retinopathy and BDNF: a review on its molecular basis and clinical applications. J Ophthalmol. 2020;2020:1602739. doi: 10.1155/2020/1602739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airaksinen MS, Saarma M. The GDNF family: signalling, biological functions and therapeutic value. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:383–394. doi: 10.1038/nrn812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Samerria S, Radovick S. The role of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in the control of neuroendocrine regulation of growth. Cells. 2021;10:2664. doi: 10.3390/cells10102664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Hanif AM, Gogniat MA, Prall BC, Haider R, Aung MH, Prunty MC, Mees LM, Coulter MM, Motz CT, Boatright JH, Pardue MT. TrkB signalling pathway mediates the protective effects of exercise in the diabetic rat retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2018;47:1254–1265. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo A, Aragona E, Bandello F. VEGF-targeting drugs for the treatment of retinal neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy. Ann Med. 2022;54:1089–1111. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2064541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babon JJ, Nicola NA. The biology and mechanism of action of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Growth Factors. 2012;30:207–219. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2012.687375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailes J, Soloviev M. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and its monitoring in medical diagnostic and in sports. Biomolecules. 2021;11:217. doi: 10.3390/biom11020217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, Chacko AS, Nickerson JM, Boatright JH, Pardue MT. Treadmill exercise promotes retinal astrocyte plasticity and protects against retinal degeneration in a mouse model of light-induced retinal degeneration. J Neurosci Res. 2022;100:1695–1706. doi: 10.1002/jnr.25063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, Karesh AM, Hogan K, Chacko AS, Douglas GL, Feola AJ, Nickerson JM, Pybus A, Wood L, Boatright JH, Pardue MT. Voluntary exercise preserves visual function and reduces inflammatory response in an adult mouse model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Sci Rep. 2024;14:6940. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-57027-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathina S, Das UN. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its clinical implications. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:1164–1178. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.56342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becic T, Studenik C, Hoffmann G. Exercise increases adiponectin and reduces leptin levels in prediabetic and diabetic individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Sci (Basel) 2018;6:97. doi: 10.3390/medsci6040097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei F, Lee HHC, Liu X, Gunner G, Jin H, Ma L, Wang C, Hou L, Hensch TK, Frank E, Sanes JR, Chen C, Fagiolini M, He Z. Restoration of visual function by enhancing conduction in regenerated axons. Cell. 2016;164:219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JL, Zeiler SR, Jones KR. Patterned expression of BDNF and NT-3 in the retina and anterior segment of the developing mammalian eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2996–3005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennie JA, Shakespear-Druery J, De Cocker K. Muscle-strengthening exercise epidemiology: a new frontier in chronic disease prevention. Sports Med Open. 2020;6:40. doi: 10.1186/s40798-020-00271-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz LI, Popovich PG. Inflammation and axon regeneration. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:577–583. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834c208d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biadgo B, Tamir W, Ambachew S. Insulin-like growth factor and its therapeutic potential for diabetes complications - mechanisms and metabolic links: a review. Rev Diabet Stud. 2020;16:24–34. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2020.16.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]