Abstract

Background

Well designed and properly executed randomised trials are considered the most reliable evidence on the benefits of healthcare interventions. However, there is overwhelming evidence that the quality of reporting is not optimal. The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement was designed to improve the quality of reporting and provides a minimum set of items to be included in a report of a randomised trial. CONSORT was first published in 1996, then updated in 2001 and 2010. Here, we present the updated CONSORT 2025 statement, which aims to account for recent methodological advancements and feedback from end users.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of the literature and developed a project-specific database of empirical and theoretical evidence related to CONSORT, to generate a list of potential changes to the checklist. The list was enriched with recommendations provided by the lead authors of existing CONSORT extensions (Harms, Outcomes, Non-pharmacological Treatment), other related reporting guidelines (TIDieR) and recommendations from other sources (e.g., personal communications). The list of potential changes to the checklist was assessed in a large, international, online, three-round Delphi survey involving 317 participants and discussed at a two-day online expert consensus meeting of 30 invited international experts.

Results

We have made substantive changes to the CONSORT checklist. We added seven new checklist items, revised three items, deleted one item, and integrated several items from key CONSORT extensions. We also restructured the CONSORT checklist, with a new section on open science. The CONSORT 2025 statement consists of a 30-item checklist of essential items that should be included when reporting the results of a randomised trial and a diagram for documenting the flow of participants through the trial. To facilitate implementation of CONSORT 2025, we have also developed an expanded version of the CONSORT 2025 checklist, with bullet points eliciting critical elements of each item.

Conclusions

Authors, editors, reviewers, and other potential users should use CONSORT 2025 when writing and evaluating manuscripts of randomised trials to ensure that trial reports are clear and transparent.

Author summary

To interpret a randomised trial accurately, readers need complete and transparent information on its methods and findings.

The CONSORT 2025 statement provides updated guidance for reporting the results of randomised trials, that reflects methodological advancements and feedback from end users.

The CONSORT 2025 statement consists of a 30-item checklist of essential items, a diagram for documenting the flow of participants through the trial, and an expanded checklist that details the critical elements of each checklist item.

Authors, editors, reviewers, and other potential users should use CONSORT 2025 when writing and evaluating manuscripts of randomised trials to ensure that trial reports are clear and transparent.

Introduction

“Readers should not have to infer what was probably done; they should be told explicitly.” Douglas G Altman [1]

Randomised trials, when appropriately designed, conducted, analysed, and reported, are generally considered the highest quality evidence in evaluating healthcare interventions. Critical appraisal of the quality of randomised trials is possible only if their design, conduct, analysis, and results are thoroughly and accurately reported. To interpret a trial accurately, readers need complete and transparent information on its methods and findings. However, extensive evidence displays that the completeness of reporting of randomised trials is inadequate [2,3] and that incomplete reporting may be associated with biased estimates of intervention effects [4]. Similarly, having a clear and transparent trial protocol is important because it prespecifies the methods used in the trial, such as the primary outcome, thereby reducing the likelihood of undeclared post hoc changes [5].

Efforts to improve the reporting of randomised trials gathered impetus in the early 1990s and resulted in the Standardised Reporting of Trials (SORT) and Asilomar initiatives in 1994. Those initiatives then led to publication of the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement in 1996 [6], revised in 2001 [7] with an accompanying explanation and elaboration document [8]. CONSORT was then updated in 2010 [9], along with an updated explanation and elaboration article [10]. Similar problems related to the lack of complete and transparent reporting of trial protocols led to the development of the SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) statement, published in 2013 [11], and its accompanying explanation and elaboration document [12] explaining the principles underlying the statement.

CONSORT is endorsed by numerous journals worldwide and by prominent editorial organisations, including the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME), International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and Council of Science Editors (CSE). The introduction of CONSORT within journals has been shown to be associated with improved quality of reports of randomised trials. Some evidence shows that journal endorsement of CONSORT is associated with better reporting and that reporting is improving over time [2,13–15]. A Cochrane review of 50 evaluations of 16,604 trials assessed the association between journals’ endorsement of CONSORT and the reporting of trials they published; 25 of 27 CONSORT checklist items were more completely reported when a trial was published in a CONSORT endorsing as opposed to non-endorsing journal [2,14]. However, a causal effect cannot be proven. At a minimum, CONSORT has sensitised many end users (e.g., authors, journal editors, and peer reviewers) to how important careful and thorough reporting can be for randomised trials.

SPIRIT and CONSORT are evidence-based guidelines that comprise a checklist of essential items that should be included in protocols and primary reports of completed randomised trials, respectively, and a diagram that documents the flow of participants through a trial. These statements provide guidance to authors on the minimum information that should be included in the reporting of trials to ensure that trial protocols and trial reports are clear and transparent. They are published alongside explanation and elaboration documents, which provide the meaning and rationale for each checklist item, examples of good reporting, and relevant empirical evidence where possible.

In January 2020, the SPIRIT and CONSORT executive groups met in Oxford, UK. As the SPIRIT and CONSORT statements are conceptually linked, with overlapping content and similar dissemination and implementation strategies, the two groups decided it was more effective to work together and formed one group. The CONSORT 2025 statement is being simultaneously published in The BMJ, JAMA, The Lancet, Nature Medicine, and PLOS Medicine.

Decision to update the SPIRIT and CONSORT statements

SPIRIT and CONSORT are living guidelines and it is vital that the statements are periodically updated to reflect new evidence, methodological advancements, and feedback from users; otherwise, their value and usefulness will diminish over time[16]. Updating the SPIRIT 2013 and CONSORT 2010 statements together was also an opportunity to further align both checklists and to provide users with consistent guidance in the reporting of trial design, conduct, analysis, and results from trial protocol to final publication. Harmonising the reporting process should improve usability and adherence, and lead to more-complete reporting [17]. Here, we introduce the updated CONSORT 2025 statement; the updated SPIRIT 2025 statement is published separately [18].

Development of CONSORT 2025

The methods used to update the CONSORT statement followed the EQUATOR Network guidance for developers of health research guidelines [19] and have been described in detail elsewhere [20,21]. In brief, we first conducted a scoping review of the literature to identify published comments suggesting modifications and additions or reflecting on strengths and challenges of CONSORT 2010, the findings of which have been published separately [22]. We also developed a project specific database (SCEBdb) for empirical and theoretical evidence related to CONSORT and risk of bias in randomised trials [23]. The evidence identified in the scoping review was combined with evidence from, and recommendations provided by the lead authors of, certain key existing CONSORT extensions whose checklist items apply to all trials (Harms [24], Outcomes [25]), or a considerable number of trials [26] (Non-pharmacological Treatment [27]), other related reporting guidelines (the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) [28]), and recommendations from other sources (e.g., personal communications).

Using the existing CONSORT 2010 checklist as the starting point, a list of potential modifications or additions to the checklists was then created using the gathered evidence from the scoping review and recommendations. This list of potential changes was presented to end users for feedback in a large international online Delphi survey, involving 317 participants who responded to round 1, 303 to round 2 and 290 to round 3. Delphi participants were identified through existing SPIRIT and CONSORT collaborations, and professional research networks and societies. Participants were also recruited via an expression of interest form on the SPIRIT-CONSORT update project website. A broad range of end user roles were represented, the most frequent being statisticians/methodologists/epidemiologists (n = 198), systematic reviewers/guideline developers (n = 73), trial investigators (n = 73), clinicians (n = 58), journal editors (n = 47), and patient representatives (n = 17) (numbers not mutually exclusive). During the three-round Delphi survey, participants were asked to rate on a 5-point Likert scale the extent to which they agreed with the inclusion of each item in the updated CONSORT checklist. Free text boxes were provided for comments on each item and to suggest additional new checklist items.

The Delphi survey results were then presented and discussed at a two-day online expert consensus meeting via Zoom, on 1 and 2 March 2023, attended by 30 invited international participants representing the different stakeholder groups included in the Delphi survey. During the meeting, each new and modified CONSORT checklist item was discussed and agreement sought. An anonymous poll via Zoom was used to help establish the level of support for items where the discussion indicated differing opinions; these polls were advisory and no formal consensus threshold was specified.

After the expert consensus meeting, the executive group held a two-day, in-person writing meeting in Oxford on 25 and 26 April 2023, where the format and wording of each new or modified CONSORT checklist item was reviewed and agreed on. The draft checklist was then circulated to consensus meeting participants to confirm whether they represented the group consensus or needed clarification. CONSORT items were further revised by the executive group in response to this feedback. The finalised items address the minimum content for inclusion in a trial report, although that should not deter prospective authors from including additional information that they deem important or that facilitates replication. Members of the executive group and the 30 invited consensus meeting participants are authors of the manuscript and their names are listed at the end of the manuscript.

Main changes to CONSORT 2025

We have made a number of substantive changes to the CONSORT 2025 checklist (see Box 1). We have added seven new checklist items, revised three items, deleted one item, and integrated several items from key CONSORT extensions (Harms [24], Outcomes [25], Non-pharmacological Treatment [27]) and other related reporting guidelines (TIDieR [28]). We also restructured the CONSORT checklist, with a new section on open science, which includes items that are conceptually linked, such as trial registration (item 2), where the trial protocol and statistical analysis plan can be accessed (item 3), sharing of de-identified participant level data (item 4), and funding and conflicts of interest (item 5). We have also harmonised the wording between CONSORT and SPIRIT checklist items and clarified and simplified the wording of some items. For a detailed comparison of the changes made in the CONSORT 2025 checklist from CONSORT 2010, see S1 Appendix. We have also updated the CONSORT explanation and elaboration document [29], which has been extensively revised and describes the rationale and scientific background for each CONSORT 2025 checklist item and provides published examples of good reporting.

Box 1. Summary of main changes in CONSORT 2025.

Addition of new checklist items

Item 4: added item on data sharing, including where and how individual de-identified participant data, statistical code, and any other materials can be accessed.

Item 5b: added item on financial and other conflicts of interest of manuscript authors.

Item 8: added item on how patients and/or the public were involved in the design, conduct, and/or reporting of the trial.

Item 12b: added item on eligibility criteria for sites and for individuals delivering the interventions, where applicable

Item 15: added item on how harms and other unintended effects were assessed.

Item 21: added items to define who is included in each analysis (e.g., all randomised participants) and in which group (item 21b), and how missing data were handled in the analysis (item 21c).

Item 24: added item on intervention delivery, including how the intervention and comparator were actually administered (item 24a) and details of concomitant care received during the trial (item 24b).

Completely revised checklist items

Item 3: revised item to include where the statistical analysis plan can be accessed in addition to the trial protocol.

Item 10: revised item to include reporting of important changes to the trial after it commenced, including any outcomes or analyses that were not prespecified.

Item 26: revised item to specify for each primary and secondary outcome—the number of participants included in the analysis and the number of participants with available data at each time point for each treatment group.

Deletion of checklist item

Deleted item on generalisability of trial findings, which is now incorporated under trial limitations (item 30).

Integration of checklist items from key CONSORT extensions

Structure and organisation of checklist items

Restructuring of checklist, with a new section on open science, which includes items that are conceptually linked such as trial registration (item 2), where the trial protocol and statistical analysis plan can be accessed (item 3), sharing of de-identified participant level data (item 4), and funding and conflicts of interest (item 5).

Aligned wording of some CONSORT checklist items with that of SPIRIT checklist items and vice versa.

Clarified and simplified wording of some items.

To help facilitate implementation of CONSORT 2025, we have also developed an expanded version of the CONSORT 2025 checklist, with bullet points eliciting critical elements of each item. This is similar to the model proposed by the COBWEB (CONSORT-based web tool) [30] and COBPeer (CONSORT based peer review tool) [31] studies and used in the 2020 PRISMA guidance for reporting systematic reviews [32]. The expanded checklist comprises an abridged version of elements presented in the CONSORT 2025 explanation and elaboration document [29], with examples and references removed (see S2 Appendix).

Scope of CONSORT 2025

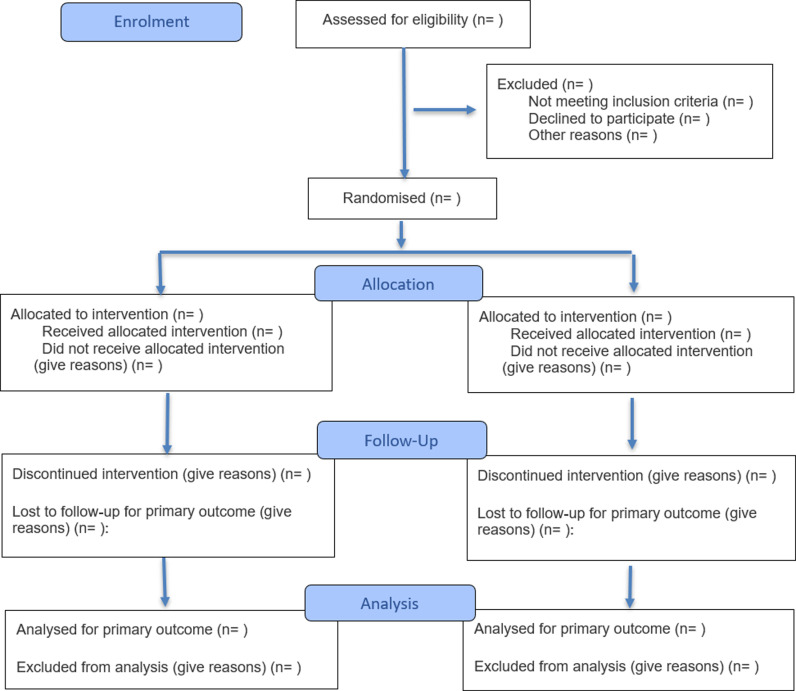

The CONSORT 2025 statement comprises a 30-item checklist and provides a minimum set of items to be included in a report of a randomised trial (Table 1) and a diagram for documenting the flow of participants through a trial (Fig 1). We strongly recommend the CONSORT 2025 statement be used alongside the CONSORT 2025 explanation and elaboration document [29]. The CONSORT 2025 statement supersedes the CONSORT 2010 statement, which should no longer be used. Journal editors and publishers should update their instructions to authors to refer to CONSORT 2025. CONSORT 2025 provides guidance for reporting all randomised trials but focuses on the most common type, the two-group parallel design.

Table 1. CONSORT 2025 checklist of information to include when reporting a randomised trial.

| Section/topic | No | CONSORT 2025 checklist item description |

|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | ||

| Title and structured abstract | 1a | Identification as a randomised trial |

| 1b | Structured summary of the trial design, methods, results, and conclusions | |

| Open science | ||

| Trial registration | 2 | Name of trial registry, identifying number (with URL) and date of registration |

| Protocol and statistical analysis plan | 3 | Where the trial protocol and statistical analysis plan can be accessed |

| Data sharing | 4 | Where and how the individual de-identified participant data (including data dictionary), statistical code and any other materials can be accessed |

| Funding and conflicts of interest | 5a | Sources of funding and other support (e.g., supply of drugs), and role of funders in the design, conduct, analysis and reporting of the trial |

| 5b | Financial and other conflicts of interest of the manuscript authors | |

| Introduction | ||

| Background and rationale | 6 | Scientific background and rationale |

| Objectives | 7 | Specific objectives related to benefits and harms |

| Methods | ||

| Patient and public involvement | 8 | Details of patient or public involvement in the design, conduct and reporting of the trial |

| Trial design | 9 | Description of trial design including type of trial (e.g., parallel group, crossover), allocation ratio, and framework (e.g., superiority, equivalence, non-inferiority, exploratory) |

| Changes to trial protocol | 10 | Important changes to the trial after it commenced including any outcomes or analyses that were not prespecified, with reason |

| Trial setting | 11 | Settings (e.g., community, hospital) and locations (e.g., countries, sites) where the trial was conducted |

| Eligibility criteria | 12a | Eligibility criteria for participants |

| 12b | If applicable, eligibility criteria for sites and for individuals delivering the interventions (e.g., surgeons, physiotherapists) | |

| Intervention and comparator | 13 | Intervention and comparator with sufficient details to allow replication. If relevant, where additional materials describing the intervention and comparator (e.g., intervention manual) can be accessed |

| Outcomes | 14 | Prespecified primary and secondary outcomes, including the specific measurement variable (e.g., systolic blood pressure), analysis metric (e.g., change from baseline, final value, time to event), method of aggregation (e.g., median, proportion), and time point for each outcome |

| Harms | 15 | How harms were defined and assessed (e.g., systematically, non-systematically) |

| Sample size | 16a | How sample size was determined, including all assumptions supporting the sample size calculation |

| 16b | Explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines | |

| Randomisation: | ||

| Sequence generation | 17a | Who generated the random allocation sequence and the method used |

| 17b | Type of randomisation and details of any restriction (e.g., stratification, blocking and block size) | |

| Allocation concealment mechanism | 18 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (e.g., central computer/telephone; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed containers), describing any steps to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned |

| Implementation | 19 | Whether the personnel who enrolled and those who assigned participants to the interventions had access to the random allocation sequence |

| Blinding | 20a | Who was blinded after assignment to interventions (e.g., participants, care providers, outcome assessors, data analysts) |

| 20b | If blinded, how blinding was achieved and description of the similarity of interventions | |

| Statistical methods | 21a | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes, including harms |

| 21b | Definition of who is included in each analysis (e.g., all randomised participants), and in which group | |

| 21c | How missing data were handled in the analysis | |

| 21d | Methods for any additional analyses (e.g., subgroup and sensitivity analyses), distinguishing prespecified from post hoc | |

| Results | ||

| Participant flow, including flow diagram | 22a | For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended intervention, and were analysed for the primary outcome |

| 22b | For each group, losses and exclusions after randomisation, together with reasons | |

| Recruitment | 23a | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up for outcomes of benefits and harms |

| 23b | If relevant, why the trial ended or was stopped | |

| Intervention and comparator delivery | 24a | Intervention and comparator as they were actually administered (e.g., where appropriate, who delivered the intervention/comparator, how participants adhered, whether they were delivered as intended (fidelity)) |

| 24b | Concomitant care received during the trial for each group | |

| Baseline data | 25 | A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group |

| Numbers analysed, outcomes and estimation | 26 |

For each primary and secondary outcome, by group:

|

| Harms | 27 | All harms or unintended events in each group |

| Ancillary analyses | 28 | Any other analyses performed, including subgroup and sensitivity analyses, distinguishing pre-specified from post hoc |

| Discussion | ||

| Interpretation | 29 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence |

| Limitations | 30 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, generalisability, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses |

Fig 1. CONSORT 2025 flow diagram.

Flow diagram of the progress through the phases of a randomised trial of two groups (i.e., enrolment, intervention allocation, follow-up, and data analysis). CONSORT = Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Extensions to CONSORT have been developed to tackle the methodological issues associated with reporting different types of trial designs, data, and interventions. Examples of extensions for trial designs include recommendations for adaptive designs [33], cluster trials [34], crossover trials [35], early phase trials [36], factorial trials [37], non-inferiority and equivalence trials [38], pragmatic trials [39], multi-arm trials [40], n-of-1 trials [41], pilot and feasibility trials [42], and within-person trials [43]. Other extensions include non-pharmacological treatments [27], outcomes [25], patient reported outcomes [44], surrogate outcomes [45], social and psychological interventions [46], harms [24], abstracts [47], and health equity [48]. We will engage with the leaders of these extensions to implement a process for aligning them with the updated CONSORT 2025 statement. In the meantime, we recommend that readers use the existing version of the relevant CONSORT extension(s).

Implication and limitations

The objective of the CONSORT 2025 statement is to provide a minimum set of recommendations to authors about the content they should include in order to report their trials in a clear, complete, and transparent manner [9,10]. Readers, peer reviewers, clinicians, guideline writers, patients and the public, and editors can also use CONSORT 2025 to help them appraise the reporting of randomised trials. We also strongly recommend the submission of a completed CONSORT 2025 checklist as part of the manuscript submission process, detailing where in the manuscript checklist items are reported, and uploaded as part of the supplementary materials [49]. An explicit description of what was done and what was found, without ambiguity or omission, best serves the interests of all readers [9].

It is important to note that CONSORT 2025 and SPIRIT 2025 do not include recommendations for designing, conducting, or analysing trials, but nevertheless the recommendations contained here can help researchers in the design, conduct, and analysis of their trial by highlighting key issues to consider. Updating the SPIRIT and CONSORT statements together was also an opportunity to align reporting in both checklists and to provide users with consistent guidance in the reporting of trial design, conduct, and analysis, from the trial protocol to final publication [17]. Thus, clear and transparent reports of trial protocols should in turn facilitate properly designed and well conducted trials. In addition, transparent reporting of trial results can reveal deficiencies in research if they exist and allow better estimates of their prevalence and severity. Importantly, however, CONSORT 2025 is not meant to be used as a quality assessment instrument. Rather, the content of CONSORT 2025 focuses on reporting items related to the internal and external validity of randomised trials.

With CONSORT 2025, we do not suggest a rigid structure for the reporting of randomised trials. Instead, the format of articles should abide by the journal’s individual style and its “Instructions to Authors.” Authors should address checklist items somewhere in the article, with sufficient detail and clarity [9]. We also promote the use of additional online supplementary material to allow for more detailed reporting of the trial methods and results than may be permissible within the typical length of some print journal articles. Full data and code sharing offers another, higher level of transparency and we recommend providing detailed information on whether this is happening or planned to happen (e.g., after some time) in a randomised trial.

CONSORT urges clarity and transparency of reporting which reflects the actual trial design, conduct, and analysis. High quality reporting is an important step when considering issues related to reproducibility [50]. We encourage trial authors to detail what was done and to acknowledge if something was not done or was modified, ensuring alignment of information with that reported in the trial protocol, statistical analysis plan, and trial registry. A joint SPIRIT-CONSORT website (https://www.consort-spirit.org/) has been established to provide more information about the CONSORT and SPIRIT statements, including additional resources and training materials aimed at researchers, research trainees, journal editors, and peer reviewers. The website also includes resources aimed at patients and the public that explain the importance of clear and transparent reporting of randomised trials and their importance in the delivery of evidence based healthcare.

CONSORT 2025 represents a living guideline that will continue to be periodically updated to reflect new evidence and emerging perspectives. Such an approach is important to ensure the guidance remains relevant to end users, including authors, patients and the public, journal editors, and peer reviewers.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

SPIRIT-CONSORT executive group: Sally Hopewell, University of Oxford, UK; An-Wen Chan, University of Toronto, Canada; Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; David Moher, University of Ottawa, Canada; Kenneth Schulz, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA; Isabelle Boutron, Université Paris Cité, France. Gary Collins and Ruth Tunn, both of University of Oxford, UK, were also involved in leading the SPIRIT and CONSORT 2025 update.

SPIRIT-CONSORT 2025 consensus meeting participants: Rakesh Aggarwal, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, India; Michael Berkwits, Office of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA (formally JAMA and the JAMA Network at time of consensus meeting); Jesse A Berlin, Rutgers University/JAMA Network Open USA; Nita Bhandari, Society for Applied Studies, India; Nancy J Butcher, The Hospital for Sick Children, Canada; Marion K Campbell, University of Aberdeen, UK; Runcie CW Chidebe, Project PINK BLUE, Nigeria/Miami University, Ohio, USA; Diana Elbourne, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK; Andrew J Farmer, University of Oxford, UK; Dean A Fergusson, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Canada; Robert M Golub, Northwestern University, USA; Steven N Goodman, Stanford University, USA; Tammy C Hoffmann, Bond University, Australia; John PA Ioannidis, Stanford University, USA; Brennan C Kahan, University College London, UK; Rachel L Knowles, University College London, UK; Sarah E Lamb, University of Exeter, UK; Steff Lewis, University of Edinburgh, UK; Elizabeth Loder, The BMJ, UK; Martin Offringa, Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Canada; Dawn P Richards, Clinical Trials Ontario, Canada; Frank W Rockhold, Duke University, USA; David L Schriger, University of California, USA; Nandi L Siegfried, South African Medical Research Council, South Africa; Sophie Staniszewska, University of Warwick, UK; Rod S Taylor, University of Glasgow, UK; Lehana Thabane, McMaster University/St Joseph’s Healthcare, Canada; David Torgerson, University of York, UK; Sunita Vohra, University of Alberta, Canada; and Ian R White, University College London, UK.

We dedicate CONSORT 2025 to the late Doug Altman who was instrumental in the development of the SPIRIT and CONSORT statements and whose files and correspondence contributed to this update following his death. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all those who participated in the SPIRIT-CONSORT 2025 update Delphi survey. We also acknowledge Camilla Hansen Nejstgaard for conducting the scoping review of the literature to identify suggested changes to CONSORT 2010 and for comparing CONSORT 2025 with RoB2, Lasse Østengaard for developing the SCEB (SPIRIT-CONSORT Evidence Bibliographic) database of empirical evidence to support the development of CONSORT, Jen de Bayer and Patricia Logullo for their involvement during the consensus meeting, and Lina El Ghosn for initial drafting of the expanded CONSORT checklist.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was granted by the Central University Research Ethics Committee, University of Oxford (R76421/RE001). All Delphi participants provided informed consent to participate.

Patient and public involvement: The CONSORT 2025 checklist items and the explanations here were developed using input from an international Delphi survey and consensus meeting. The Delphi survey was advertised via established patient and public involvement (PPI) networks, and 17 respondents self-identified as a “patient or public representative” and completed the Delphi survey. In addition, three of the participants in the expert consensus meeting were patient or public representatives who were leaders in advancing PPI.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: CONSORT 2025 will be disseminated via a new website, consort-spirit.org, which will include materials designed for patients and the public.

Funding Statement

The 2025 update of SPIRIT and CONSORT was funded by the MRC-NIHR: Better Methods, Better Research (MR/W020483/1). The funder reviewed the design of the study but had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the MRC, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- 1.Altman DG. Better reporting of randomised controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 1996;313(7057):570–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7057.570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D. Does use of the CONSORT Statement impact the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials published in medical journals? A Cochrane review. Syst Rev. 2012;1:60. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):267–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savović J, Jones HE, Altman DG, Harris RJ, Jüni P, Pildal J, et al. Influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates from randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):429–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldacre B, Drysdale H, Powell-Smith A, Dale A, Milosevic I, Slade E, et al. The COMPare trials project. 2016. [accessed 26 May 2021]. Available from: https://www.compare-trials.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276(8):637–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285(15):1987–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, et al. ; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials). The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(8):663–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):726–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche PC, Krleža-Jerić K, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):200–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A, Schulz K, Altman DG, Hill C, et al. Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? A systematic review. Med J Aust. 2006;185(5):263–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00557.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dechartres A, Trinquart L, Atal I, Moher D, Dickersin K, Boutron I, et al. Evolution of poor reporting and inadequate methods over time in 20 920 randomised controlled trials included in Cochrane reviews: research on research study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards for Reporting of Trials). Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA. 2001;285(15):1992–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simera I, Altman DG. ACP Journal Club. Editorial: Writing a research article that is “fit for purpose”: EQUATOR Network and reporting guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):JC2-2, JC2-3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-02002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopewell S, Boutron I, Chan A-W, Collins GS, de Beyer JA, Hróbjartsson A, et al. An update to SPIRIT and CONSORT reporting guidelines to enhance transparency in randomized trials. Nat Med. 2022;28(9):1740–3. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01989-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan A-W, Boutron I, Hopewell S, Altman DG, Blinding K, Boulanger L, et al. SPIRIT 2025 statement: updated guideline for protocols of randomised trials. BMJ. 2025;389:e081477. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2024-081477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopewell S, Chan A-W, Boutron I, et al. Protocol for updating the SPIRIT 2013 (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) and CONSORT 2010 (CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) Statements [version 1.0, 2022. Aug 9]. Database: OSF. doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/6HJYG [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tunn R, Boutron I, Chan A-W, Collins GS, Hróbjartsson A, Moher D, et al. Methods used to develop the SPIRIT 2024 and CONSORT 2024 Statements. J Clin Epidemiol. 2024;169:111309. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2024.111309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nejstgaard CH, Boutron I, Chan A-W, Chow R, Hopewell S, Masalkhi M, et al. A scoping review identifies multiple comments suggesting modifications to SPIRIT 2013 and CONSORT 2010. J Clin Epidemiol. 2023;155:48–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Østengaard L, Barrientos A, Boutron I, Chan A, Collins G, Hopewell S, et al. Development of a topic‐specific bibliographic database supporting the updates of SPIRIT 2013 and CONSORT 2010. Cochrane Evid Synth Methods. 2024;2(5). doi: 10.1002/cesm.12057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junqueira DR, Zorzela L, Golder S, Loke Y, Gagnier JJ, Julious SA, et al. ; CONSORT Harms Group. CONSORT Harms 2022 statement, explanation, and elaboration: updated guideline for the reporting of harms in randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2023;158:149–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butcher NJ, Monsour A, Mew EJ, Chan A-W, Moher D, Mayo-Wilson E, et al. Guidelines for reporting outcomes in trial reports: the CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 extension. JAMA. 2022;328(22):2252–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.21022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghosn L, Boutron I, Ravaud P. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extensions covered most types of randomized controlled trials, but the potential workload for authors was high. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;113:168–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P; CONSORT NPT Group. CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):40–7. doi: 10.7326/M17-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hopewell S, Chan A-W, Collins G. CONSORT 2025 explanation and elaboration: updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ. 2025;389:e081124. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2024-081124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnes C, Boutron I, Giraudeau B, Porcher R, Altman DG, Ravaud P. Impact of an online writing aid tool for writing a randomized trial report: the COBWEB (Consort-based WEB tool) randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2015;13:221. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0460-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chauvin A, Ravaud P, Moher D, Schriger D, Hopewell S, Shanahan D, et al. Accuracy in detecting inadequate research reporting by early career peer reviewers using an online CONSORT-based peer-review tool (COBPeer) versus the usual peer-review process: a cross-sectional diagnostic study. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1436-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dimairo M, Pallmann P, Wason J, Todd S, Jaki T, Julious SA, et al. ; ACE Consensus Group. The adaptive designs CONSORT extension (ACE) statement: a checklist with explanation and elaboration guideline for reporting randomised trials that use an adaptive design. Trials. 2020;21(1):528. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04334-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG; CONSORT Group. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e5661. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dwan K, Li T, Altman DG, Elbourne D. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised crossover trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4378. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yap C, Solovyeva O, de Bono J, Rekowski J, Patel D, Jaki T, et al. Enhancing reporting quality and impact of early phase dose-finding clinical trials: CONSORT Dose-finding Extension (CONSORT-DEFINE) guidance. BMJ. 2023;383:e076387. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-076387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahan BC, Hall SS, Beller EM, Birchenall M, Chan A-W, Elbourne D, et al. Reporting of factorial randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2023;330(21):2106–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.19793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJW, Altman DG; CONSORT Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2594–604. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.87802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. ; CONSORT group; Pragmatic Trials in Healthcare (Practihc) group. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008;337:a2390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juszczak E, Altman DG, Hopewell S, Schulz K. Reporting of multi-arm parallel-group randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2019;321(16):1610–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vohra S, Shamseer L, Sampson M, Bukutu C, Schmid CH, Tate R, et al. ; CENT Group. CONSORT extension for reporting N-of-1 trials (CENT) 2015 Statement. BMJ. 2015;350:h1738. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, Bond CM, Hopewell S, Thabane L, et al. ; PAFS consensus group. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandis N, Chung B, Scherer RW, Elbourne D, Altman DG. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension checklist for reporting within person randomised trials. BMJ. 2017;357:j2835. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD; CONSORT PRO Group. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309(8):814–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manyara AM, Davies P, Stewart D, Weir CJ, Young AE, Blazeby J, et al. Reporting of surrogate endpoints in randomised controlled trial reports (CONSORT-Surrogate): extension checklist with explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2024;386:e078524. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-078524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montgomery P, Grant S, Mayo-Wilson E, Macdonald G, Michie S, Hopewell S, et al. ; CONSORT-SPI Group. Reporting randomised trials of social and psychological interventions: the CONSORT-SPI 2018 Extension. Trials. 2018;19(1):407. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2733-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D, Wager E, Middleton P, Altman DG, et al. ; CONSORT Group. CONSORT for reporting randomized controlled trials in journal and conference abstracts: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welch VA, Norheim OF, Jull J, Cookson R, Sommerfelt H, Tugwell P; CONSORT-Equity and Boston Equity Symposium. CONSORT-Equity 2017 extension and elaboration for better reporting of health equity in randomised trials. BMJ. 2017;359:j5085. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirst A, Altman DG. Are peer reviewers encouraged to use reporting guidelines? A survey of 116 health research journals. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodman SN, Fanelli D, Ioannidis JPA. What does research reproducibility mean?. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(341):341ps12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf5027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)