Abstract

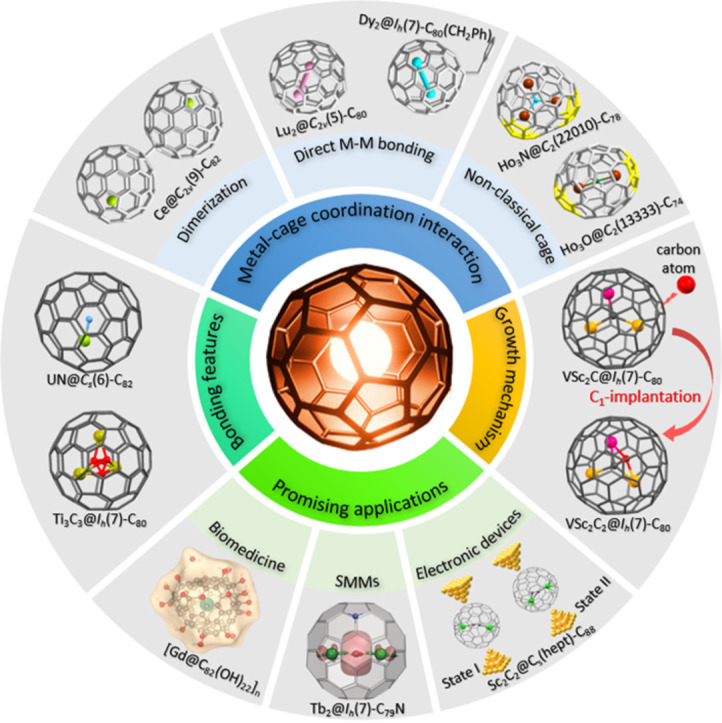

Fullerenes are a collection of closed polycyclic polymers consisting exclusively of carbon atoms. Recent remarkable advancements in the fabrication of metal-fullerene nanocatalysts and polymeric fullerene layers have significantly expanded the potential applications of fullerenes in various domains, including electrocatalysis, transistors, energy storage devices, and superconductors. Notably, the interior of fullerenes provides an optimal environment for stabilizing a diverse range of metal ions or clusters through electron transfer, resulting in the formation of a novel class of hybrid molecules referred to as endohedral metallofullerenes (EMFs). The utilization of advanced synthetic methodologies and the progress achieved in separation techniques have played a pivotal role in expanding the diversity of the encapsulated metal constituents, consequently leading to distinctive structural, electronic, and physicochemical properties of novel EMFs that surpass conventional ones. Intriguing phenomena, including regioselective dimerization between EMFs, direct metal-metal bonding, and non-classical cage preferences, have been unveiled, offering valuable insights into the coordination interactions between metallic species and carbon. Of particular importance, the recent achievements in the comprehensive characterization of EMFs based on transition metals and actinide metals have generated a particular interest in the exploration of new metal clusters possessing long-desired bonding features within the realm of coordination chemistry. These clusters exhibit a remarkable affinity for coordinating with non-metal atoms such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur, thus making them highly intriguing subjects of systematic investigations focusing on their electronic structures and physicochemical properties, ultimately leading to a deeper comprehension of their unparalleled bonding characteristics. Moreover, the versatility conferred by the encapsulated species endows EMFs with multifunctional properties, thereby unveiling potential applications in various fields including biomedicine, single-molecule magnets, and electronic devices.

Keywords: Fullerenes, Metallofullerenes, Crystallography, Single-molecule magnet, Metal-metal bonding

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

In 1985, a seminal breakthrough was achieved by Kroto, Smalley, Curl and coworkers during a series of experiments aimed at elucidating the formation of long-chain carbon molecules in celestial environments. Through laser vaporization of a graphite disk, they successfully detected the presence of C60 named as fullerene in short, thus unveiling its remarkable spherical structure and the presence of pi-electrons on the surface [1]. This unexpected finding, recognized by the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1996, served as a catalyst for the subsequent exploration and advancement of nanocarbon chemistry. As the sole molecular allotrope of elemental carbon, fullerenes exhibit diverse chemical properties, well-defined molecular structures and outstanding physicochemical properties. Over the past years, numerous valuable materials derived from fullerenes have been developed, finding applications in a wide range of disciplines including biology, medicine, electronics, and photovoltaics.

Remarkably, the interior of fullerenes exhibits a capability to accommodate metal ions or clusters, leading to the formation of hybrid materials characterized by strong metal-carbon interactions and unique electronic structures, called endohedral metallofullerenes (EMFs) [2], [3], [4], [5]. In 1985, Smalley reported the first solvent extractable endohedral metallofullerene, La@C82, unveiling a fascinating phenomenon involving a three-electron transfer from the entrapped La ion to the C82 fullerene cage [6], [7], [8]. This intramolecular charge transfer confers EMFs with the ability to stabilize a wide range of isolated metal ions and reactive metal clusters, thus offering an avenue for fundamental investigations into unprecedented bonding features and potential applications that were previously inaccessible with empty fullerenes. Over the last decade, considerable efforts have been dedicated to the encapsulation of various metals within fullerenes, primarily employing the highly effective arc discharge method. While Group-3 (Sc, Y) and lanthanide metals have been extensively investigated and represent the most versatile and intriguing branches of EMFs, recent breakthroughs in metallofullerene research have unveiled the discovery of EMFs containing transition metals and actinides [9]. The considerably strong host-guest interactions arising from a formal four or five-electron transfer from the metal to the cage not only stabilize pentagon adjacencies on the fullerene cage but also give rise to novel configurations of metal clusters within the cage. These developments provide new insights into the potential applications in such areas as magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents, single-molecule magnets, and electron-spin quantum computing. In this comprehensive review, our main focus is to provide an overview of recent advancements in the field of EMFs, encompassing improved synthesis and purification methodologies, new members of the EMF family, comprehensive understanding of the formation mechanisms, and the potential applications of EMFs in diverse fields such as nanomedicine, single-molecule magnets, and electronic devices.

2. Novel exploration in the studies of fullerenes

2.1. Monolayer fullerene network

Carbon, as one of the most versatile elements in the periodic table, exhibits a remarkable ability to form bonds with itself and almost all other elements through sp, sp2, and sp3 hybridizations. Diamond and graphite, the two well-known carbon allotropes, are characterized by extended networks of sp3-hybridized and sp2-hybridized atoms, respectively [2]. By combining different hybridizations and geometries of carbon, it is possible to create numerous synthetic allotropes. Graphene, as a prominent synthetic carbon allotrope, has garnered significant attention due to its two-dimensional (2D) structure and exceptional carrier transport properties arising from its conjugated carbon network with unique π-electron system [10], [11], [12], [13]. In efforts to complement the zero-bandgap nature of graphene, extensive research has been focused on the identification of other 2D carbon materials [14], [15], [16], [17]. However, the preparation of large-sized single-crystal 2D carbon materials with moderate bandgaps remains challenging [18]. In contrast to structural units comprising single atoms, 2D structures constructed from nanoclusters are anticipated to possess improved topologies and distinctive properties. In this context, fullerene C60, a representative carbon cluster, is particularly intriguing for the formation of atomic-scale 2D carbon materials through polymerization. Such polymeric fullerene layers are expected to exhibit regularly undulating topologies with a repeating arrangement of carbon clusters in a 2D plane, offering interesting electronic and magnetic properties [19], [20], [21]. Recently, 2D carbon materials composed of covalently bonded C60 molecules in a periodic nanocluster network structure have been successfully synthesized using various methods. Zheng et al. achieved the fabrication of monolayer polymeric C60 through an organic cation slicing approach, obtaining both monolayer and few-layer polymeric C60 with distinct quasi-hexagonal and quasi-tetragonal bulk single crystals (Fig. 1) [22]. The monolayer polymeric C60 features covalently bonded cluster cages of C60 in a plane, exhibiting high crystallinity, good thermodynamic stability, and a moderate bandgap of approximately 1.6 eV. Furthermore, the asymmetric lattice structure imparts notable in-plane anisotropic properties to the monolayer polymeric C60. However, challenges remain in addressing solvent residue resulting from solution exfoliation, despite efforts to neutralize the ionic sheets using hydrogen peroxide. To overcome this, Roy et al. presented a straightforward synthesis of another 2D polymer of C60 that enables the production of large flakes via mechanical exfoliation, thereby yielding high-quality molecularly thin flakes with clean interfaces [23]. The synthesis of polymeric fullerene layers offers a promising avenue for the systematic design of materials, enabling the construction of 2D heterostructures characterized by distinctive topological structures and captivating properties. Consequently, these advances open up possibilities for potential applications in diverse areas, including transistors, energy storage devices, superconductors, confined light manipulation, and quantum-materials-based devices [13,16,24,25].

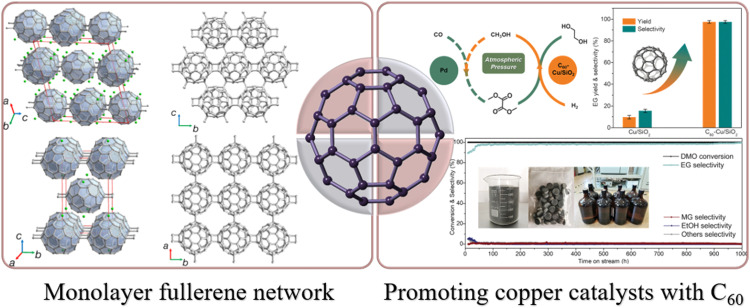

Fig. 1.

Novel exploration in the studies of fullerenes. Left: crystal structures of quasi-hexagonal C60 and quasi-tetragonal C60[22]. Right: catalytic performance of Cu/SiO2 and C60—Cu/SiO2 at 1 bar, H2/DMO = 200 (v/v, volume ratio), temperature 190 ℃ [28]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. Copyright 2022, The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

2.2. Metal-fullerene nanocatalysts

The unique electronic properties of fullerenes, such as high electron affinity, have also brought new possibilities for the exploration of novel applications. For instance, Forrest et al. demonstrated centimetre-scale diffusion of electrons within a photoactive, fullerene-based organic heterostructure, revealing exceptionally long diffusion lengths surpassing 3.5 cm [26]. This remarkable long-range electron diffusion observed in fullerene devices highlights their advantageous potential in optoelectronic applications when compared to conventional organic semiconductors, which typically exhibit limited charge-diffusion lengths of less than a micrometre. In addition, non-ferromagnetic materials such as diamagnetic Cu and paramagnetic Mn can undergo modifications in magnetization through charge transfer at molecular interfaces between metal films and fullerenes [27]. The C60/transition metal complexes exhibit strong interfacial 3dz-p coupling and interface reconstruction, enabling them to surpass the Stoner criterion and display ferromagnetic behavior at room temperature. The fullerenes can also modulate the electronic density of Cu species by accepting electrons from Cu, while providing electron feedback to electron-deficient copper, thus conferring beneficial redox properties during catalysis. In a recent study, Xie et al. utilized C60 as an electronic buffer to regulate the electronic density of active Cu species and overcome limitations associated with conventional Cu catalysts, which can selectively hydrogenate dimethyl oxalate (DMO) to Ethylene glycol (EG) but exhibit limited activity and stability at low pressure (Fig. 1) [28]. They achieved an impressive EG yield of up to 98% ± 1% in the hydrogenation of DMO using a C60—Cu/SiO2 catalyst under ambient pressure and temperatures of 180 ℃ to 190 ℃. Notably, the majority of C60 was found to be loaded on the Cu surface without intercalating into Cu lattice sites, thereby preserving the surface structure of Cu nanoparticles. The C60 species (C60 and C60−) served as single-electron acceptors from Cu0 or single-electron donors to Cu2+, thereby stabilizing Cu+ and inhibiting its transformation to Cu0 or Cu2+. Apart from DMO hydrogenation, the use of C60 as an electron buffer in Cu/SiO2 catalysts to enhance hydrogen absorption also holds potential for other copper-catalyzed hydrogenation reactions. Specifically, the C60—Cu/SiO2 catalyst was found to exhibit advantages in the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO, enabling the CO2-to-EG process to be carried out under ambient conditions. The investigation of C60—Cu/SiO2 catalyst represents a significant advancement in the design of high-performance electrocatalysts. This exploration has provided fresh insights into the development of novel approaches to overcome the limitations encountered by conventional catalysts. Subsequent studies have further contributed to this field, exemplified by a Pt/C60 single-atom catalyst [29] and the C60-based pentagonal defect-rich nanocarbon electrocatalyst [30]. Likewise, the very recently reported N-doped defect-rich carbon nano-onions (CNOs), which were synthesized using C60 as sacrificial seeds, have also demonstrated to be high-performance carbon-based electrocatalysts [31]. These studies offer promising avenues for enhancing catalytic performance through innovative strategies and pave the way for potential breakthroughs in the field of electrocatalysis.

3. Improvement in the synthesis and purification of EMFs

In 1990, Krätschmer and Huffman successfully accomplished the large-scale synthesis of the abundant C60 and C70 fullerenes through the resistive heating of graphite in a helium atmosphere within a furnace [32]. This landmark achievement paved the way for further advancements in fullerene synthesis. Subsequently, Smalley introduced a modified version of the Krätschmer-Huffman fullerene reactor, employing an electric arc discharge between graphite electrodes to induce a plasma. This technique has since become the predominant approach employed for fullerene production [33]. The arc discharge generates extremely high temperatures in the center, while a decreasing temperature gradient allows for the formation and stabilization of fullerenes at cooler regions.

In comparison to the conventional arc-discharge method, the combustion method has shown notable efficiency in facilitating the industrial-scale synthesis of fullerenes. The application of low-pressure combustion, coupled with an appropriate C/O ratio, was initially reported in 1991 as a viable approach for fullerene synthesis [34]. However, the underlying reaction mechanism governing the formation of fullerenes and the growth of carbon particles during combustion remains poorly understood. Moreover, the composition of fullerene species within the carbon soot generated through combustion is highly complex [35].

Even though most fullerenes and their hydrogenated derivatives obtained from combustion soot strictly adhered to the Isolated Pentagon Rule (IPR), which stipulates that a stable fullerene should have its 12 pentagons separated from each other, recent reports showed that non-IPR fullerenes are produced through combustion, such as a C64 molecule with three directly-fused pentagons and an isomeric form of C60 with double-fused pentagons [36,37]. Additionally, the smaller C50 fullerene, featuring 10 pairs of double-fused pentagons, has also been identified in combustion soot [38]. In 2019, Xie et al. presented an interesting non-IPR hydrofullerene, C66H4, which was obtained in a low-pressure diffusion flame of benzene, acetylene, and oxygen [39]. The unique structure of C66H4 was unambiguously determined through single-crystal X-ray diffraction, revealing a nonclassical geometry characterized by two heptagons and two pairs of fused pentagons with C2v symmetry. The shared vertices of the fused pentagons are bonded to four hydrogen atoms, inducing a conversion of the sp2 hybridization of the carbon atoms at the hydrogen-linking sites to sp3 hybridization. This hydrogenation, coupled with the adjacent heptagons, effectively alleviates the sp2-bond strains present at the abutting-pentagon positions of the diheptagonal fused pentagon in C66. Computations indicate that the in-situ hydrogenation process plays a crucial role in stabilizing the diheptagonal C66H4, which significantly differs from the previously stabilized four isomers of C66 obtained through arc-discharge experiments [40], [41], [42]. This diheptagonal C66 structure represents the first instance of a fullerene cage with two heptagons captured during an in-situ carbon-clustering growth process occurring under the combustion conditions.

Similar to the synthesis of empty fullerenes, endohedral metallofullerenes (EMFs) are typically produced using an arc-discharge methodology. In this process, a target rod consisting of a mixture of metal oxides and graphite powder is subjected to arcing under direct current conditions. This results in the formation of a carbon-rich plasma under an inert gas atmosphere of helium or argon, along with the appropriate reactive gas, such as hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, or ammonia [5]. However, the arc-discharge method for synthesizing EMFs is known to be challenging as it lacks selectivity, leading to the production of complex mixtures containing various empty fullerenes, EMFs, nanotubes, and amorphous carbon. Although efficient high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) columns for separating EMFs are available, the purification of EMFs through chromatographic techniques presents significant challenges. This is primarily due to the diverse range of species present in fullerene extracts and the similarity in size and shape among carbon cages. Additionally, the content of EMFs in the extracts is typically limited, further complicating the purification process, even with the utilization of multi-step or recycling HPLC approaches [43].

In order to overcome the challenges associated with chromatographic purification, alternative non-chromatographic separation techniques have been developed, particularly focusing on endohedral metallofullerenes (EMFs). In 2005, Echegoyen and colleagues achieved a significant milestone by successfully separating Sc3N@Ih-C80 and Sc3N@D5h-C80 isomers through selective chemical oxidation, marking a leading advancement in this field [44]. Subsequently, various versatile strategies have emerged, capitalizing on the distinctive chemical reactivity of EMFs compared to empty fullerenes, effective for the separation and purification of EMFs. These strategies include the utilization of Diels Alder (DA) reactions [45,46], the SAFA (stir and filter approach) methodology [47], [48], [49], the employment of Lewis acids [50], [51], [52], and in situ reduction induced by reflux in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) [53].

An alternative and promising approach for purifying EMFs involves their recognition by supramolecular receptors, leveraging their facile conformational and electronic tunability. Pioneering work by Anderson and colleagues in 2010 demonstrated the host-guest complexation of EMFs using a metalloporphyrin-based receptor [54]. Specifically, molecular receptors incorporating three porphyrins exhibited remarkably high affinities for La@C82. The strong binding observed can be attributed to the electronic polarization of La@C82 as well as the size and shape complementarity between La@C82 and the molecular receptor.

Supramolecular purification strategies utilizing nanocapsules has gained momentum as highly selective platforms for isolating EMFs from carbon soot based on cage size and metallocluster composition. In 2017, Ribas and coworkers reported the use of a supramolecular nanocapsule capable of purifying various EMF extracts with remarkable selectivity through reversible host-guest reactions [55]. The nanocapsule, assembled from two tetracarboxylate ZnII-porphyrin segments and four CuII-based macrocyclic clips, facilitated efficient entrapment of smaller cages (C60 and C70), while larger Sc3N-based EMFs (Sc3N@Ih(7)-C80 and Sc3N@D5h(6)-C80) remained in solution (Fig. 2). Leveraging these size-dependent differential affinities, Sc3N@C80 was successfully isolated from a mixture containing empty fullerenes and Sc3N-containing EMFs with exceptionally high purity. In 2018, this nanocapsule demonstrated selective separation of a series of U-based actinide EMFs from U/Sc-based soot [56]. The nanocapsule crystals, when immersed in a toluene solution of soot extract containing empty fullerenes, Sc- and U-based EMFs, exhibited preferential capture of U2@Ih(7)-C80. Following the complete extraction of U2@Ih(7)-C80 from the crude mixture, subsequent selective encapsulation of the unprecedented Sc2CU@Ih(7)-C80 with the same number of transferred charges as observed for U2@Ih(7)-C80 was achieved using the same protocol (Fig. 2). These findings confirmed that the nanocapsule selectively responded to the nature of the distinct internal clusters trapped within the fullerene cages. Calculations indicated that the highly directional electron-density distribution of U-based fullerenes, induced by the host-guest interaction, likely underlies the observed discrimination ability.

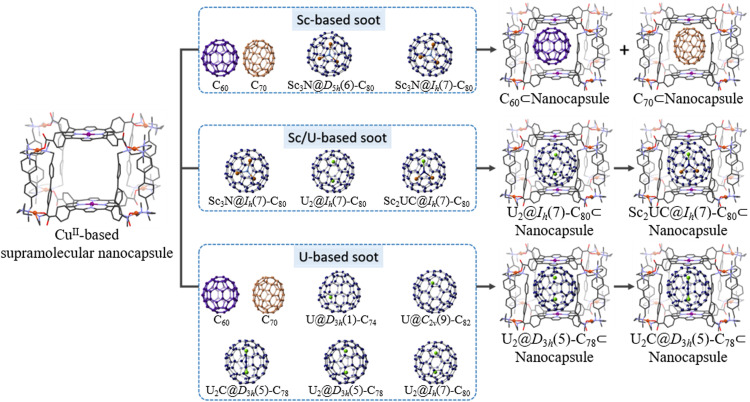

Fig. 2.

Straightforward purification methodology to the desired EMFs. Selective isolation of different types of EMFs from raw soot using a CuII-based supramolecular nanocapsule.

In 2019, the nanocapsule was employed for purifying a mixture of empty fullerenes and U-based EMFs of different cage sizes, including U@C74, U@C84, U2@C78, U2@C80, and U2C@C78 [57]. The remarkable selective binding enabled the isolation of pure U2@C78 in a single step. Subsequently, by exposing the remaining mixture to additional nanocapsule crystals, pure U2C@C78 was selectively complexed (Fig. 2). An in-depth examination of the host-guest selectivity revealed a smaller energy destabilization of the system upon porphyrin compression, attributable to the cylindrical shape of the D3h(5)-C78 cage. Consequently, the nanocapsule exhibited a lower energy penalty during encapsulation of the elongated D3h(5)-C78 compared to the spherical Ih(7)-C80. Importantly, all encapsulated fullerenes could be easily released via a solvent-washing procedure, showcasing the potential of this straightforward methodology for practical and nonchromatographic EMF purification. The development of such streamlined purification protocols is crucial to ensure the availability of large quantities of pure EMFs for further studies, particularly for EMF derivatization and potential applications.

4. Novel phenomena in recently reported EMFs

Macroscopic synthesis of EMFs was successfully accomplished by the Smalley group in 1985, and the first solvent extraction of La-EMFs was described in 1991. The distinct electronic structure of La@C2n demonstrated a three-electron transfer from the entrapped La atom to the fullerene cage [7,8]. Such intramolecular charge transfer endows EMFs with unique properties that are not attainable by empty fullerenes. A significant breakthrough in fullerene research occurred in 1999 with the discovery of Sc3N@C80, marking the first member of Sc-EMFs [58]. This discovery was particularly significant due to the notably high yield of Sc3N@C80 compared to the other reported EMFs, propelling EMF research forward [43]. Comprehensive experimental and theoretical investigations concluded the six-electron transfer occurs from the entrapped Sc3N cluster to the C80 cage, resulting in the mutual stabilization of the internal nitride cluster and the external cage with a specific isomeric structure. Thereafter, significant strides were made in the discovery of several other types of La-based or Sc-based metal clusters stabilized by fullerene cages, such as di-metal species, nitride cluster, carbide cluster, oxide cluster, sulfide cluster, cyanide cluster and so on. Systematic investigations on carbide cluster metallofullerenes unveiled a notable "size effect" between the encapsulated metal cluster and the fullerene cage. By leveraging the geometric effect, a series of large fullerenes (C90—C104) were successfully stabilized through the encapsulation of a large La2C2 cluster, while the relatively smaller cages (C72—C88) tend to accommodate the smaller Sc2C2 cluster [59], [60], [61].

4.1. Regioselective dimerization of pristine EMFs

Despite the significance of La-EMFs and Sc-EMFs as highly diverse and interesting branches of endohedral fullerenes, extensive efforts have been dedicated to encapsulating metals of various types inside fullerenes using the relatively effective arc discharge method. The incorporation of different metal species within fullerenes introduces novel structures and unexpected phenomena to the field of EMFs, thereby offering valuable insights into modern chemistry. Notably, intriguing regioselective dimerization phenomena have been observed in the crystalline states of Y@Cs(6)-C82, Er@Cs(6)-C82, and Ce@C2v(9)-C82 when co-crystallized with NiII(OEP) (octaethylporphyrin dianion) (Fig. 3). These dimers involve the connection of two fullerene cages through a C—C single bond [62], [63], [64]. However, in the case of La-EMFs and Sc-EMFs, dimerization does not occur during the crystallization process. The formation of a similar dimer was only achieved through the synthesis of a bis-adduct of La@C2v(9)-C82 [65]. Density functional theory calculations suggest that the regioselective dimer formation can be attributed to the localization of high spin density and pyramidalization resulting from the encapsulation of Y, Er, and Ce within the fullerene cage. Moreover, the predominant metal centers in the dimers are in close proximity to the porphyrin molecules, while the sites of dimerization are situated far from the respective inner metal atoms. This indicates that the location of the metal atom may exert a crucial influence on the spin distribution.

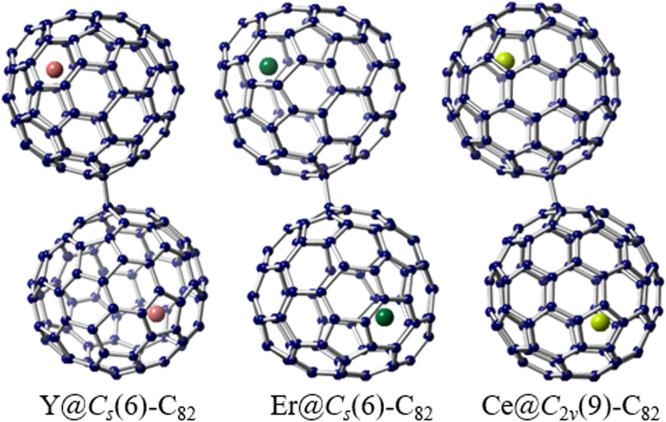

Fig. 3.

Regioselective dimerization between EMFs. Drawings of the dimers of pristine metallofullerenes: Y@Cs(6)-C82, Er@Cs(6)-C82, and Ce@C2v(9)-C82. Only the major metal sites and major cage orientation are shown. The Y atoms are highlighted in red, the Er atoms are highlighted in green, and the Ce atoms are highlighted in yellow green.

4.2. Direct metal-metal bonding in pristine EMFs

In addition to mono-EMFs, the emergence of di-EMFs featuring diverse metal species offers significant opportunities for investigating metal-metal bonding and gaining new insights into fullerene chemistry. Experimental confirmation of the metal-metal bond was initially reported in the triazinyl radical monoadduct and benzyl radical monoadduct of La2@Ih(7)-C80 [66,67]. The addition of triazinyl radicals or benzyl radicals to the closed-shell La2@Ih(7)-C80 resulted in the formation of open-shell monoadducts, namely La2@Ih(7)-C80(C3N3Ph2) or La2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph), featuring a single-electron localized in the La-La bond within the cage (Fig. 4). It has been demonstrated that the unpaired electron is transferred to the molecular orbital of the internal La2 unit upon the addition of triazinyl radical or benzyl radical to La2@Ih(7)-C80, leading to the formation of a single-electron La-La bond. In contrast, other encapsulated lanthanide dimers within Ih(7)-C80, such as M2@Ih(7)-C80 (M = Y, Gd, Dy, Tb, etc.), exhibited a single-electron occupied M-M bond due to a different energy level alignment between the molecular orbital of M-M bonding and the fullerene cage (Fig. 4) [68,69]. In these cases, only one unpaired electron occupies the M-M bonding molecular orbital, while the other electron is delocalized over the fullerene cage, resulting in a formal oxidation state of +2.5 for the metal ion. However, these molecules are typically unstable radicals that are stabilized in the form of their benzyl radical monoadducts or azafullerenes by substituting a carbon atom in the cage by a nitrogen atom.

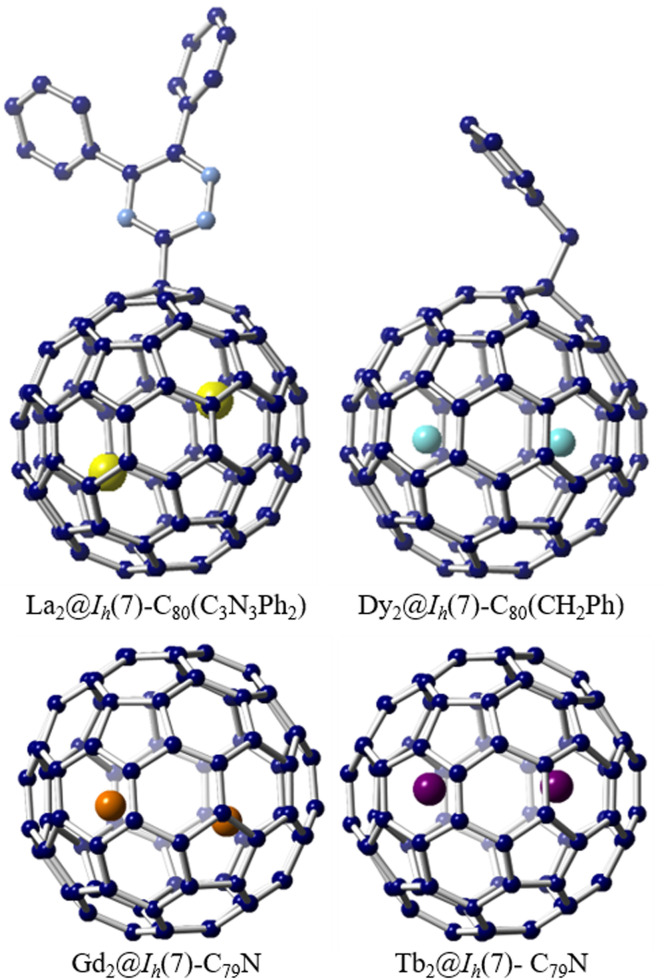

Fig. 4.

Metal-metal bonding in functionalized EMFs. Drawings show the single crystal X-ray examples of benzyl radical monoadducts or azafullerenes: La2@Ih(7)-C80(C3N3Ph2), Dy2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph), Gd2@Ih(7)-C79N and Tb2@Ih(7)-C79N. The La atoms are highlighted in yellow, the Dy atoms are highlighted in light blue, the Gd atoms are highlighted in orange, and the Tb atoms are highlighted in purple.

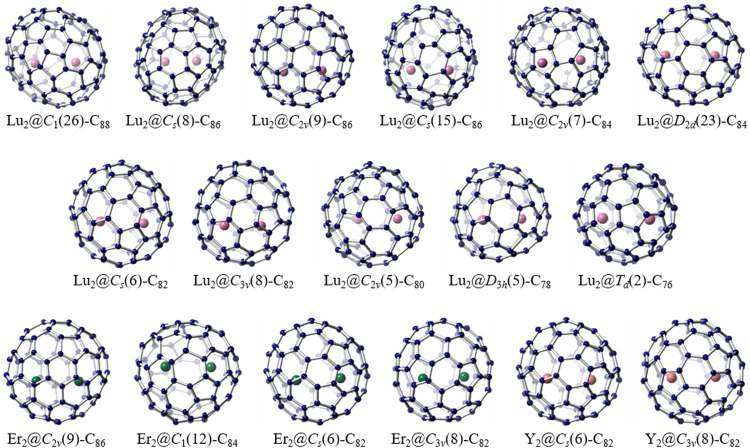

Conversely, recent experimental evidence from a series of Lu2@C76–88 isomers has provided the first conclusive confirmation of the metal-metal bond in pristine (unfunctionalized) EMFs (Fig. 5) [70,71]. Crystallographic analysis revealed that the distances between the two Lu atoms in these isomers fall within the range of a Lu-Lu single bond length, thereby unequivocally confirming direct Lu-Lu bonding between the repulsive Lu2+ ions. Theoretical calculations further support the thermodynamic favorability of Lu2@C82–86 isomers due to the formation of the two-electron occupied Lu-Lu bond. The hybrid composition of Lu-Lu bonds demonstrates that the Lu 6s orbital contributes significantly to the metal bonding molecular orbitals. Consequently, in these di-lutetium EMFs, each Lu atom contributes one 6s electron and one 5d electron to the fullerene cage, leading to the establishment of a formal divalent state for each Lu ion. Similarly, direct metal-metal bonds have also been identified for Y2@C3v(8)-C82 and a series of Er2@C82–86 isomers (Fig. 5) [72,73]. It is noteworthy that for Er2@Cs(6)-C82, Er2@C3v(8)-C82, and Er2@C2v(9)-C86, the two Er ions establish a two-electron occupied Er-Er bond, while Y2@C3v(8)-C82 and Er2@C1(12)-C84 exhibit a single-electron occupied M-M (M = Y, Er) bond, highlighting distinct bonding characteristics of the identical metallic units within different fullerene cages.

Fig. 5.

Metal-metal bonding in pristine EMFs. Drawings show the single crystal X-ray structures of diverse M2@C2n-type (M = Lu, Er, and Y) dimetallofullerenes: Lu2@C1(26)-C88, Lu2@Cs(8)-C86, Lu2@C2v(9)-C86, Lu2@Cs(15)-C86, Lu2@C2v(7)-C84, Lu2@D2d(23)-C84, Lu2@Cs(6)-C82, Lu2@C3v(8)-C82, Lu2@C2v(5)-C80, Lu2@D3h(5)-C78, Lu2@Td(2)-C76, Er2@C2v(9)-C86, Er2@C1(12)-C84, Er2@Cs(6)-C82, Er2@C3v(8)-C82, Y2@Cs(6)-C82 and Y2@C3v(8)-C82. The Lu atoms are highlighted in pink, the Er atoms are highlighted in green, and the Y atoms are highlighted in red.

4.3. Specific non-IPR cage preferences

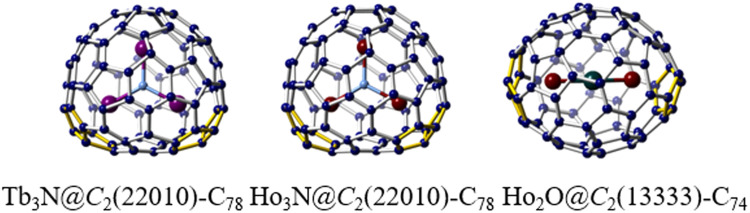

The incorporation of different combinations of metals and/or non-metal atoms within metallofullerenes also results in a diverse composition of entrapped metal clusters. This diversity gives rise to unique properties in novel metallofullerenes that differ from those of conventional metallofullerenes. Presently, an extensive number of cluster metallofullerenes featuring non-IPR fullerene cage isomers have been discovered, unveiling their specific cage preferences for encapsulated unique metal clusters. For instance, the classical Sc3N cluster favors an IPR D3h(5)-C78 cage [43], whereas Ho3N and Tb3N clusters exhibit a preference for a non-IPR C2(22,010)-C78 cage with two pairs of adjacent pentagons (Fig. 6) [74]. Computational and spectroscopic investigations have also revealed that M3N@C78 species with M = Y, Lu, La, Gd, Dy, and Tm exhibit the same preference for the C2(22,010)-C78 cage [5]. Although significant non-IPR cage structures have been predicted for the Sc2O cluster, the only isolated species is Sc2O@C70, which features a non-IPR C2(7892)-C70 cage [75]. The predicted non-IPR cages for Sc2O@C2n, namely Cs(10,528)-C72 and C2(13,333)-C74, have not been experimentally observed. Remarkably, recent crystallographic analysis of various Ho2O-containing EMFs unambiguously confirmed the adoption of an expanded configuration by the Ho2O cluster within the non-IPR C2(13,333)-C74 cage (Fig. 6), thus indicating the role of metal cluster compositions as influential templates of cage formation during the discharging process [76].

Fig. 6.

Specific non-classical cage preferences. Single crystal X-ray examples of three novel cluster metallofullerenes: Tb3N@C2(22,010)-C78, Ho3N@C2(22,010)-C78 and Ho2O@C2(13,333)-C74. The Tb atoms are highlighted in purple, the Ho atoms are highlighted in claret-red, the N atoms are highlighted in blue, and the oxygen atom is highlighted in dark green. The fused-pentagons are highlighted in yellow.

4.4. Transition metal-containing EMFs

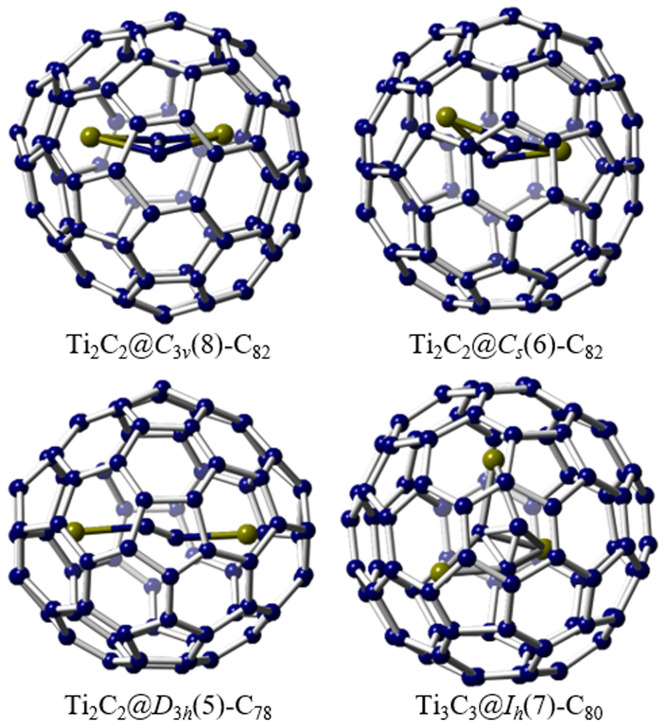

Remarkably, within the realm of macroscopically synthesized EMFs over the past two decades, rare-earth metals, such as Group-3 elements (Sc, Y), and a majority of the lanthanide metals have been encapsulated within fullerene cages. This leads to an intriguing question regarding the possibility of forming EMFs with other elements in significant yields. The exploration of EMFs containing adjacent d-block transition metals was initiated in 1992 with the mass spectrometric detection of a titanium-only EMF, Ti@C28, thereby expanding the scope of EMF investigations [77,78]. However, the macroscopic synthesis of Ti-containing EMFs (Ti2C80 and Ti2C84) was first reported by Shinohara and colleagues [79,80], with subsequent studies theoretically determining their stable structures as Ti2C2@C78 and Ti2C2@C82, respectively [81,82]. Furthermore, in 2013, Echegoyen et al. successfully identified the first Ti-containing sulfide cluster metallofullerene, Ti2S@C78, where the cage exhibits D3h(5)-C78 symmetry and the Ti2S cluster demonstrates a near-linear structure [83]. More recently, Lu and co-workers achieved the preparation and structural characterization of a groundbreaking Ti-containing carbide cluster metallofullerene, Ti3C3@Ih(7)-C80 (Fig. 7) [84]. The internal C3 unit displayed an anticipated cyclopropane-like geometry, forming a novel perpendicular coordination with the Ti3 unit. Notably, this unique coordination pattern, resembling cyclopropane, has never been observed in any reported organometallic complexes, providing novel insights into organo-transition metal chemistry. Subsequently, three Ti-containing CCMFs, namely Ti2C2@D3h(5)-C78, Ti2C2@Cs(6)-C82, and Ti2C2@C3v(8)-C82, featuring an encapsulated Ti2C2 cluster within the carbon cages, were successfully isolated and characterized (Fig. 7) [85]. Single crystal X-ray analysis revealed that the Ti2C2 cluster adopted a stretched planar configuration within the smaller D3h(5)-C78 cage, while a bent butterfly geometry was observed within the relatively larger Cs(6)-C82 and C3v(8)-C82 cages. DFT calculations indicated that the anomalous geometric shapes of the Ti2C2 cluster in these carbide cluster metallofullerenes can be attributed to the varying number of electrons transferred from the Ti2C2 cluster to the cage, which is dependent on the size and electronic structure of the cage.

Fig. 7.

The macroscopic synthesis of d-block transition metal-containing EMFs. Single crystal X-ray examples of four Ti-only cluster metallofullerenes: Ti2C2@C3v(8)-C82, Ti2C2@Cs(6)-C82, Ti2C2@D3h(5)-C78 and Ti3C3@Ih(7)-C80. The Ti atoms are highlighted in olive green.

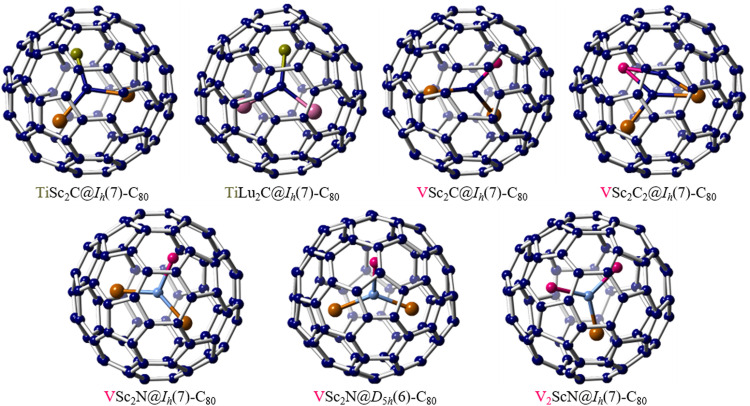

In addition to the limited instances of Ti-clusterfullerenes, an alternative approach involves utilizing Group-3 metals as the core to create versatile mixed-metal clusters in fullerene cages. When Ti was combined with Sc or Y and subjected to arc synthesis in the presence of nitrogen, the formation of nitride clusterfullerenes TiM2N@Ih(7)-C80 (M = Sc, Y) was observed [86,87]. Furthermore, by employing a reactive gas atmosphere such as methane, Popov et al. identified the formation of a distinctive type of carbide clusterfullerenes, TiM2C@Ih(7)-C80 (M = Sc, Y, Nd, Gd, Dy, Er, Lu), in which a Ti=C double bond was present (Fig. 8). This marked the first instance of EMFs featuring a multiple bond between the metal and the non-metal atom within the endohedral cluster [88], [89], [90].

Fig. 8.

The encapsulation of transition metals by using Group-3 metals as the core to create mixed-metal clusters. Single crystal X-ray examples of mixed-metal cluster fullerenes containing Ti or V: TiSc2C@Ih(7)-C80, TiLu2C@Ih(7)-C80, VSc2C@Ih(7)-C80, VSc2C2@Ih(7)-C80, VSc2N@Ih(7)-C80, VSc2N@D5h(6)-C80 and V2ScN@Ih(7)-C80. The Ti atoms are highlighted in olive green, the V atoms are highlighted in fuchsia, the Lu atoms are highlighted in pink, the Sc atoms are highlighted in brown, and the N atoms are highlighted in blue.

However, the synthesis of V-only endohedral metallofullerenes has proven to be challenging. Unlike its neighbor Ti in the first 3d transition metal series, the encapsulation of pure vanadium species within the cage is quite difficult. In light of the mixed-metal strategy that yielded successful results in the synthesis of the M-Ti system, Sc was utilized to facilitate the encapsulation of V atoms. As a result, the first mixed-metal nitride cluster fullerenes containing vanadium, namely VSc2N@Ih(7)-C80, V2ScN@Ih(7)-C80, and VSc2N@D5h(6)-C80, were successfully synthesized [91,92]. Subsequently, novel V-based trimetallic carbide cluster metallofullerenes, namely VSc2C@Ih(7)-C80 and VSc2C2@Ih(7)-C80, were also reported [93]. Similar to the mixed-metal Sc-Ti system, the presence of a V=C double bond was identified in VSc2C@Ih(7)-C80. However, the distance between V and C atoms in VSc2C2@Ih(7)-C80 corresponding to that of a typical single bond, as observed for conventional V-based organometallic complexes. Interestingly, in contrast to Ti-clusterfullerenes that typically encapsulate one Ti atom, V-containing clusters exhibit the potential to host either one or two V atoms within the fullerene cage, highlighting the sensitivity of the composition of non-Group-3 transition-metal-containing clusterfullerenes to the specific characteristics of the transition metal involved (Fig. 8).

4.5. Actinide metal-containing EMFs

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the synthesis and comprehensive investigation of actinide-based EMFs, uncovering distinct chemical bonding and coordination patterns that differ substantially from those observed in the rather extensively studied rare earth-based EMFs. Notably, the actinide elements, particularly uranium, exhibit variable oxidation states, in contrast with the relatively limited Ln2+/Ln3+oxidation states of the rare earth elements. This variation in oxidation states gives rise to new electronic structures and specific fullerene cage isomers to actinide EMFs. For instance, single crystal X-Ray diffractometric analyses and theoretical studies of monometallic uranium EMFs unveiled a cage isomer-dependent charge transfer phenomenon originating from the encapsulated uranium atom [94]. Furthermore, the considerably stronger interactions between the metal and the carbon cage in actinide EMFs have facilitated the stabilization of previously unexplored chiral non-IPR fullerene cage isomers, by providing these isomers in relatively high yields [95].

Recent investigations of uranium clusterfullerene families have unveiled the remarkable capability of fullerene cages to encapsulate diverse actinide clusters, showcasing important actinide bonding motifs achieved through electron transfer between the cluster and the carbon cage, as well as U-carbon coordination. Notably, the discovery of uranium metal cluster EMFs, such as UCU@Ih(7)-C80 and UNU@Ih(7)-C80, represent the first examples of M2C and M2N clusters in the EMF field (Fig. 9) [96,97]. In UCU@Ih(7)-C80, the combined experimental and theoretical investigations have shown a bent configuration featuring unsupported strong U=C covalent bonds for the U=C=U cluster and a formal oxidation state of 5+ for both uranium atoms. Similarly, an encapsulated U=N=U cluster has been stabilized within U2N@Ih(7)-C80, featuring an uncommon unsymmetrical structure characterized by two U=N bonds with uneven bond distances. Systematic investigations have indicated different oxidation states of +4 and +5 for the two uranium ions, with the f1/f2 population playing a dominant role in inducing distortion of the U=N=U cluster and resulting in the unsymmetrical structure. Further studies with U2X@Ih(7)-C80 (X = C, N and O) have demonstrated that the number of U(f) electrons play a crucial role in controlling the symmetry of the U2X cluster [97]. Notably, the U-X interaction in U=X=U clusters does not resemble classical multiple bonds, but rather resembles an anionic central ion Xq− with biased overlaps with the two metal ions, and this interaction weakens as the electronegativity of X increases. In addition, the crystallographic study of a mixed actinide-lanthanide cluster metallofullerene, USc2C@Ih(7)-C80, has revealed the shortest U=C double bond (2.011 Å) for U-containing EMFs to date. The U ion within the USc2C cluster, located inside the Ih(7)-C80 cage, has an oxidation state of +4, resulting in a similar electronic structure to the previously reported Ti4+(Sc3+)2C cluster [98].

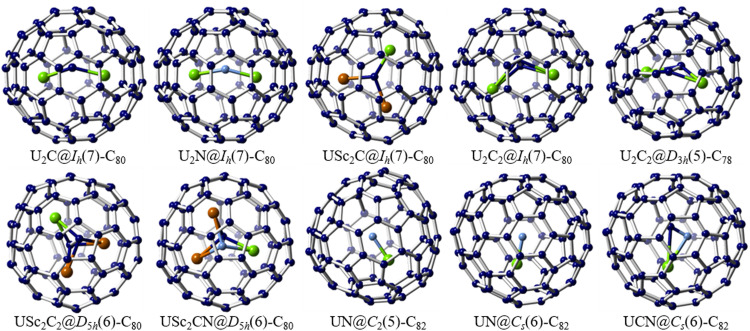

Fig. 9.

The exploration of long-desired bonding features via the strong coordination interaction between uranium and non-metal atoms. Single crystal X-ray examples of U-containing cluster metallofullerenes: U2C@Ih(7)-C80, U2N@Ih(7)-C80, USc2C@Ih(7)-C80, U2C2@Ih(7)-C80, U2C2@D3h(5)-C78, USc2C2@D5h(6)-C80, USc2CN@D5h(6)-C80, UN@C2(5)-C82, UN@Cs(6)-C82 and UCN@Cs(6)-C82. The U atoms are highlighted in light green, the Sc atoms are highlighted in brown, and the N atoms are highlighted in blue.

Another interesting finding involves the stabilization of a U2C2 cluster within both the Ih(7)-C80 and D3h(5)-C78 cages (Fig. 9) [99]. The C2 units in both compounds exhibit unprecedented C C bonds, which are not observed in other carbide cluster metallofullerenes. Unlike the U=C covalent bonds observed in UCU@Ih(7)-C80, the two U atoms in the U2C2 cluster adopt a formal 4+ oxidation state, thus forming four predominantly ionic U-C bonds. Interestingly, despite the contrasting bonding interactions between UCU@Ih(7)-C80 and U2C2@Ih(7)-C80, the U-U distances remain essentially consistent in both compounds. Subsequent investigations have further unveiled a variety of bonding motifs exhibited by uranium, exemplified by the successful synthesis and characterization of UCN@Cs(6)-C82, USc2C2@D5h(6)-C80, USc2CN@D5h(6)-C80, UN@Cs(6)-C82 and UN@C2(5)-C82, (Fig. 9) [100], [101], [102]. For instance, the UCN cluster, with a triangular configuration, exhibits an open-shell electronic structure [UCN]2+@[Cs(6)-C82]2−, with uranium adopting a + 3 oxidation state. In addition, the presence of a U N bond in the UN cluster, along with uranium displaying a formal oxidation state of +5, has been confirmed through another study with UN@Cs(6)-C82 and UN@C2(5)-C82. These findings provide evidence for the electronic structure of (UN)2+@(C82)2−. Furthermore, it has been observed that U N is immobilized and coordinated to the fullerene cage at 100 K, while rotational movement within the cage is observed at 273 K. Likewise, the electronic configurations of USc2C2@D5h(6)-C80 and USc2CN@D5h(6)-C80 have revealed intriguing donation bonding features, characterized by novel U-C partial triple bond characteristics and multicenter bonding expansion across the Sc centers. Of particular note, different oxidation states of +6 and +5 were confirmed for the U ions in USc2C2@D5h(6)-C80 and USc2CN@D5h(6)-C80, respectively. The exploration of novel uranium clusters with unprecedented bonding motifs and intriguing electronic structures not only offers valuable insights into the field of coordination chemistry and fundamental actinide bonding properties, but also broadens our knowledge of the interactions of actinide clusters within fullerene frameworks, opening up new avenues for future research in this intriguing area.

5. Improved understanding in the formation mechanism of EMFs

To date, the precise mechanisms underlying the formation of EMFs have remained elusive, impeded by the acquisition of direct experimental evidence. Although two distinct theoretical models proposing top-down and bottom-up processes have been put forward [103,104], recent investigations have focused on elucidating the specific formation mechanisms of EMFs synthesized under varying arcing conditions. The controlled synthesis studies of europium-containing EMFs have shed light on the prevalent formation of Eu@C74–88 while observing the scarcity of Eu2@C2n and Eu3@C2n species [105]. In order to comprehend the underlying factors governing the preferential formation of mono-EMFs, calculations have been employed, introducing a novel concept known as encapsulation energy (Ee) to quantify the feasibility of EMF formation. A higher Ee value corresponds to a greater likelihood of EMF formation [106], thus offering new insights into the formation mechanism of EMFs. In an alternative line of investigation, the synthesis and structural characterization of a carbide cluster metallofullerene featuring an unprecedented heptagonal ring, namely Sc2C2@Cs(hept)-C88, have provided substantial experimental evidence supporting the bottom-up growth model [107]. It has been proposed that this non-classical carbide cluster endohedral represents a kinetically trapped intermediate formed via a direct C2 insertion in the bottom-up growth process originating from Sc2C2@C2v(9)-C86. Although Sc2C2@Cs(hept)-C88 may not be thermodynamically favored, Sc2C2@C2v(9)-C86 is proposed to be more stable from a thermodynamic standpoint [108], revealing an important pathway for capturing non-classical EMFs through C2 insertion. Given the relatively low energy barrier associated with C2 insertion (approximately 2 eV), an intriguing question arises as to whether it is possible to generate novel EMFs via single carbon atom insertion (C1 insertion). To address this question, a C1 implantation mechanism was proposed based on the synthesis and crystallographic characterization of VSc2C@Ih(7)-C80 and VSc2C2@Ih(7)-C80 [93]. The C1 implantation process can be divided into two distinct steps: the bonding process (C1 insertion) and the self-driven encapsulation process. The energy barrier associated with C1 implantation (3.95 eV) is slightly higher than that of C2 insertion (∼2 eV), yet considerably lower than that of the Stone-Wales transformation (∼7 eV), thereby indicating the feasibility of C1 implantation under high temperatures generated by the arc-discharging process. Notably, detailed theoretical investigations confirm that the high likelihood of the transition from VSc2C to VSc2C2 can be attributed to the presence of an unpaired electron on the vanadium atom, which exhibits a strong affinity for electron pairing with carbon radicals. This investigation into the mechanism of C1 implantation provides the first mechanistic link elucidating the evolution of endohedral metal-carbon clusters during the formation process of EMFs.

The structural identification of various endohedral metallofullerenes has paved the way for comprehensive investigations concerning the inter-cage transformations among existing fullerene cages, which make it possible to establish typical transformation routes to offer valuable insights into the formation mechanism of EMFs. A recent study focusing on uranium EMFs possessing non-IPR chiral carbon cages, namely U@C1(17,418)-C76 and U@C1(17,894)-C80, revealing a novel structural rearrangement pathway indicative of a bottom-up growth process [95]. Specifically, enantiomer e1 (e2) of C1(17,418)-C76 and enantiomer e2 (e1) of C1(17,894)-C80 were found to be topologically connected through two C2 insertions without the need of Stone-Wales rearrangements. These pathways exhibit lower energy demands compared to those preserving the same chirality, thus providing new mechanistic insights into the formation of metallofullerenes during arc discharging processes. In a consistent manner, the interconversion map for all characterized EMFs was expanded by capturing several key cages, including U@C1(17,418)-C76, U@C1(28,324)-C80, U@C1(11)-C86, Eu@C2(27)-C88, Gd2C2@C1(51,383)-C84 and La2C2@C2(816)-C104 [105,[109], [110], [111]]. These low-symmetry fullerene cages serve as starting points for fullerenes with either IPR or non-IPR cages through diverse transformation routes. Notably, the topological analysis reveals that C1(17,418)-C76, C1(11)-C86, and C2(27)-C88 can be obtained through spontaneous rolling and wrapping directly from flat graphene sheets, consistent with observations from transmission electron microscopy (TEM) visualizations of fullerene formation from graphene sheets [112]. Additionally, it is worth noting that fullerene structural interconversion maps provide evidence for the simultaneous occurrence of both top-down and bottom-up processes during arc discharging. Certain asymmetric intermediates, such as C1(28,324)-C80, can serve as precursors for the formation of larger cages in growth processes or smaller cages in shrinking routes.

6. New achievements in the application of EMFs

The distinctive electronic structures and innovative bonding motifs exhibited by the encapsulated metal moieties, coupled with their remarkable interactions with the carbon cage, render EMFs as promising candidates for the fabrication of molecular materials with diverse applications. As the mass production of EMFs has reached significant quantities, extensive research efforts have been devoted to exploring their practical applications and uncovering their new functionalities. In this section, we will primarily discuss the recent advancements in the field of functional metallofullerene materials, with a particular focus on their applications in nanomedicine, single-molecule magnets, and electronic devices. These areas represent key domains where EMFs have demonstrated potential for significant applications and have witnessed notable progress in recent years.

6.1. Biomedical applications

The inherent non-toxicity of the carbon cage and its ability to provide a totally isolated environment for the internal metal species make water-soluble derivatives of metallofullerenes promising candidates for medical diagnosis and therapy. One notable example is the utilization of water-soluble derivatives of Gd-containing EMFs, which have demonstrated significant potential as advanced contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This is attributed to the presence of seven unpaired f-electrons in Gd3+, which give rise to super-paramagnetic properties. Similarly, a series of metallofullerenes containing Lu3N clusters have been successfully employed as X-ray contrast agents, leveraging the large cross-section of the Lu atom [43].

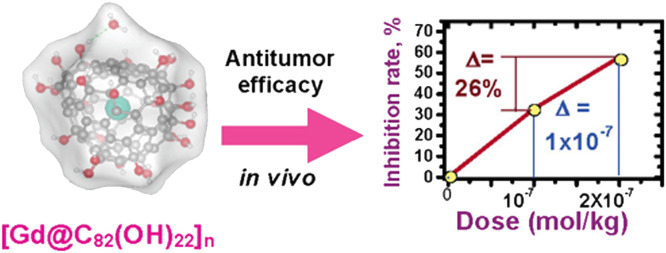

It is noteworthy to highlight that nanoparticles of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n have also demonstrated potential antitumor activity (Fig. 10). In 2005, Zhao et al. conducted a study showcasing the potent antineoplastic effects of Gd@C82(OH)22 nanoparticles with an average size of approximately 22 nm against H22 hepatoma in mice [113]. Remarkably, these nanoparticles exhibited superior anticancer efficacy compared to the clinical anticancer drug paclitaxel, while showing minimal side effects. The proposed mechanism of action for Gd@C82(OH)22 involves the indirect inhibition of tumor growth in human pancreatic cancer xenografts in a nude mouse model [114]. In addition, Gd@C82(OH)22 nanoparticles have been found to significantly suppress cancer metastasis in aggressive and invasive human breast cancer models by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase production, rather than exerting direct cytotoxicity [115]. Notably, while extensive research has focused on the anticancer properties of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles, Wang and colleagues reported a novel water-soluble Gd@C82 particles modified with amino acids, denoted as (Gd@C82)m(OH)n(Ala)x, which exhibited exceptional antitumor effects in mice implanted with H22 hepatoma [116]. These (Gd@C82)m(OH)n(Ala)x particles, with an average size of approximately 127.7 nm, demonstrated superior therapeutic efficacy by rapidly disrupting tumor blood vessels under radiofrequency (RF) irradiation, surpassing the performance of (Gd@C82)m(OH)n. Furthermore, Wang and colleagues introduced an unprecedented tumor vascular-targeting therapeutic technique for cancers, utilizing (Gd@C82)m(OH)n nanoparticles with an average diameter of approximately 140 nm and applying radiofrequency (RF) irradiation (200 MHz) for 30 min [117]. The proposed mechanism involves the accumulation of (Gd@C82)m(OH)n nanoparticles in the nanogaps between endothelial cells, leading to the specific destruction of tumor blood vessels. Subsequent investigations revealed that the therapeutic technique using (Gd@C82)m(OH)n leads to down-expression of tumor vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) [118], causing disruption of blood flow and tumor necrosis.

Fig. 10.

Biomedical applications based on water-soluble derivatives of Gd-EMFs. The very high antineoplastic efficiency of Gd@C82(OH)22 nanoparticles with an average size of approximately 22 nm against H22 hepatoma in mice [113]. Copyright 2005, American Chemical Society.

Notably, Gd@C82(OH)22 nanoparticles have also been shown to regulate oxidative stress in tumor cells in vivo and function as scavengers of reactive oxygen species (ROS), contributing to their antitumor activity. Wang and colleagues reported the therapeutic potential of (Gd@C82)m(OH)n nanoparticles in protecting oxidative injury during chemotherapy. These nanoparticles have demonstrated remarkable radical scavenging activity, thereby effectively mitigating damage induced by cyclophosphamide chemotherapy [119]. Furthermore, a water-soluble derivative of Gd@C82, modified with multiple ethylenediamine (EDA) groups and referred to as Gd@C82-(EDA)8, has been demonstrated to possess hydroxyl radical scavenging properties [120]. This derivative exhibited a cytoprotective effect by mitigating H2O2-induced injuries in human epidermal keratinocytes-adult (HEK-a) cells.

6.2. Single molecular magnets

Metallofullerenes possess unique electronic structures and internal metal atoms that give rise to diverse magnetic properties, holding great promise in various applications such as quantum information processing (QIP), memory and logic devices, medical imaging, and single-molecule magnets (SMMs) [121]. In 2012, Greber and colleagues made a significant breakthrough by discovering slow magnetic relaxation in DySc2N@Ih(7)-C80, exhibiting a magnetic blocking temperature (TB) of up to 7 K. This discovery sparked the exploration of the SMM properties of metallofullerenes containing lanthanide ions [122]. The fullerene cages in metallofullerenes act as nano-containers, providing stabilization for unconventional metal cluster configurations and protection against ambient conditions. The combination of their unique physicochemical properties, the varied structures of encapsulated magnetic species, and the potential to create functional devices, offers opportunities for creating well-controlled and high-performance SMMs for practical applications.

Recent advancements in the field have primarily focused on exploring the single-molecule magnetism of Dy-containing EMFs. Due to the presence of high thermal barriers, Dy-containing EMFs exhibit the potential for achieving remarkably high magnetic blocking temperatures and significantly prolonged magnetic lifetimes at low temperatures. However, in most cases, the existence of quantum tunneling of magnetization (QTM) will lead to a plateau in magnetic relaxation lifetimes at low temperatures, thereby placing limitations on the performance of Dy-EMF SMM. Intriguingly, in contrast to DySc2N@Ih(7)-C80, a di-lanthanide clusterfullerene, Dy2ScN@Ih(7)-C80, demonstrated magnetic hysteresis and magnetization blocking at 8 K, without exhibiting QTM [123]. Recent magnetic investigations have further revealed that the magnetization relaxation and blocking temperature in DyM2N@Ih(7)-C80 (M = Sc, Y, Lu) are related to the mass of M, while the magnetic behavior of Dy2MN@Ih(7)-C80 (M = Sc, Y, La, Lu) are associated with varied Dy…Dy coupling caused by the size of M3+ ions [124]. Significantly, the presence of ferromagnetic coupling between the two Dy spins suppresses the occurrence of zero-field QTM, while simultaneously creating new relaxation pathways that result in a relaxation rate reliant on the strength of the coupling. Consequently, recent studies in EMF SMMs have primarily focused on systems containing two Dy ions. For instance, Dy2O@C3v(8)-C82 exhibits a relatively high magnetization blocking temperature of 7.4 K [125], comparable to that of Dy2ScN@Ih(7)-C80. Notably, Dy2O@Cs(10,528)-C72, Dy2O@C2(13,333)-C74, Dy2O@Cs(6)-C82, Dy2O@C2v(9)-C82, Dy2S@C3v(8)-C82, and Dy2ScN@D5h(6)-C80 show hysteresis in the range of 4–6 K [125], [126], [127], [128], while carbide clusterfullerenes such as Dy2TiC@Ih(7)-C80, Dy2TiC2@Ih(7)-C80, and Dy2C2@Cs(6)-C82 exhibit hysteresis of magnetization below 2 K [88,127].

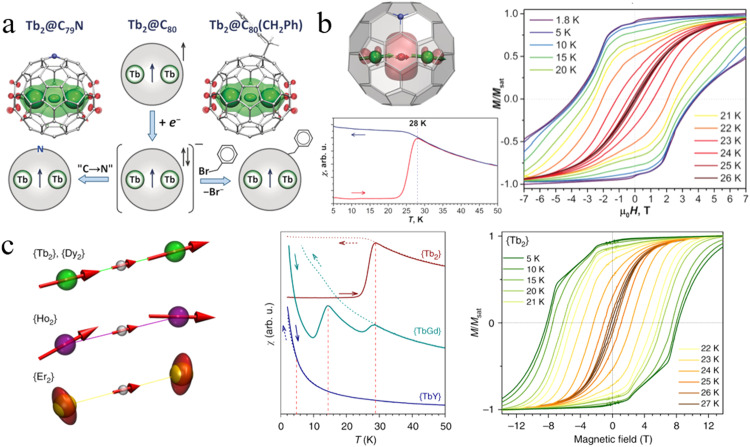

The establishment of di-metallofullerenes (di-EMFs) with a covalent metal-metal bond represents an elegant approach to enhance the magnetic coupling between ions. The formation of metal-metal bonds leads to substantial exchange interactions within magnetic molecules, thereby offering significant advantages for molecular magnetism. In 2017, Popov et al. reported the synthesis of an exceptional single molecule magnet Dy2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph) with a notable blocking temperature of magnetization at 21.9 K, exhibiting hysteresis in the temperature range of 1.8 to 21 K [69]. In this system, Dy2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph) can be regarded as a three-spin system [Dy3+-e-Dy3+], where the ferromagnetic coupling between the two Dy3+ions is facilitated through the electron spin interaction. Theoretical calculations indicate that the negatively charged electron between the Dy3+ ions mediates a strong ferromagnetic exchange between the radical Dy-Dy bond, while the direct antiferromagnetic coupling between the Dy3+ ions is negligible. Subsequent investigations on a series of M2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph) compounds (M = Y, Gd, Dy, Tb, Ho, Er, etc.) with an electron spin positioned between two magnetic ions revealed that the presence of a high-spin magnetic ground state resulting from strong ferromagnetic exchange coupling, in conjunction with single-ion anisotropy and collinearity of lanthanide spins, played pivotal roles in achieving excellent SMM behavior [129]. Particularly noteworthy is the observation that Tb2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph) exhibits a substantial coercivity and an impressively high blocking temperature of 29 K, accompanied by broader hysteresis and a longer relaxation time for QTM reaching 18 h. However, the specific shape of the 4f charge density associated with a different lanthanide element would result in the variation in magnetic anisotropy of these M2 dimers. For instance, Ho2, with mixed single-ion ligand-field (LF) states and tilted magnetic moments, exhibits only modest SMM behavior, while Er2, possessing an easy-plane single-ion anisotropy, does not demonstrate significant SMM properties (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

High-performance metallofullerene single molecular magnets. The comparison of the SMM properties between Tb2@Ih(7)-C79N and Tb2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph) [129,130]. (a) The spin density distributions in Tb2@Ih(7)-C79N and Tb2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph). (b) The alignment of magnetic moments of Tb2 dimers in Tb2@Ih(7)-C79N, as well as the magnetic hysteresis curves and blocking temperature of magnetization for Tb2@Ih(7)-C79N. (c) The alignment of magnetic moments of M2 dimers in a series of M2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph) compounds (M = Tb, Dy, Ho and Er), as well as the magnetic hysteresis curves and blocking temperature of magnetization for Tb2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph). Copyright 2019, Springer Nature. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

As previously mentioned, the M2 dimers incorporated into M2@Ih(7)-C80 (M = Y, Gd, Dy, Tb, etc.) contribute five electrons to the cage, resulting in a single-electron-occupied M-M bond with a formal oxidation state of +2.5 on each metal ion. Two approaches have been explored to stabilize these unstable radicals. The first involves the formation of radical monoadducts through functionalization of the cage with a radical group such as CF3 or benzyl. The second approach entails substituting a carbon atom in the cage with a nitrogen atom, yielding azafullerenes known as M2@Ih(7)-C79N (M = Tb, Gd…). Notably, the absence of functional groups in M2@Ih(7)-C79N would enhance its thermal stability and facilitate the growth of thin molecular films through sublimation. In 2019, it was discovered that azafullerene Tb2@Ih(7)-C79N exhibits SMM behavior with a high blocking temperature of 27 K and a significant electron-Tb exchange coupling constant (Fig. 11) [130]. This prompts an interesting comparison of the SMM properties between Tb2@Ih(7)-C79N and Tb2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph), as they possess identical spin systems encapsulated within the same fullerene cage, but with different stabilization protocols. Significantly, the considerable variation in the electrostatic potential (ESP) distribution exhibited by Tb2@Ih(7)-C79N results in a tilting of the magnetic moments of the Tb ions by approximately 7° away from the Tb-Tb bond. Conversely, in Tb2@Ih(7)-C80(CH2Ph), the magnetic moments of the Tb ions remain aligned along the Tb…Tb axis due to a less pronounced variation in the ESP.

6.3. Single-metallofullerene devices

In response to the growing demands for data-driven applications, such as machine learning, in-memory computing presents a promising approach by integrating logic operations and data storage. Various macroscopic non-volatile memory devices, including resistive switching random access memory, phase-change memory, magnetoresistive random access memory, and ferroelectric random access memory, have demonstrated the feasibility of logic-in-memory operations [131], [132], [133], [134]. In order to achieve greater miniaturization of electronic devices and enhance their power efficiency, researchers have demonstrated the operation of molecular-scale non-volatile memory devices, including self-assembled monolayers and molecular thin films, at remarkably low operating voltages below 1.0 V. Consequently, it suggests that single-molecule non-volatile memory devices could serve as a potential ultimate solution for realizing logic-in-memory computing. In this regard, the manipulation of spin or electric dipole has been recognized as a promising approach for achieving single-molecule scale in-memory logic operations. Recently, a gate-controlled three-terminal device based on Gd@C82 has demonstrated low-temperature single electric dipole bistability below 1.6 K [135]. However, achieving single electric dipole bistability at room temperature remains challenging due to the inherent difficulties associated with effectively controlling random molecular orientations.

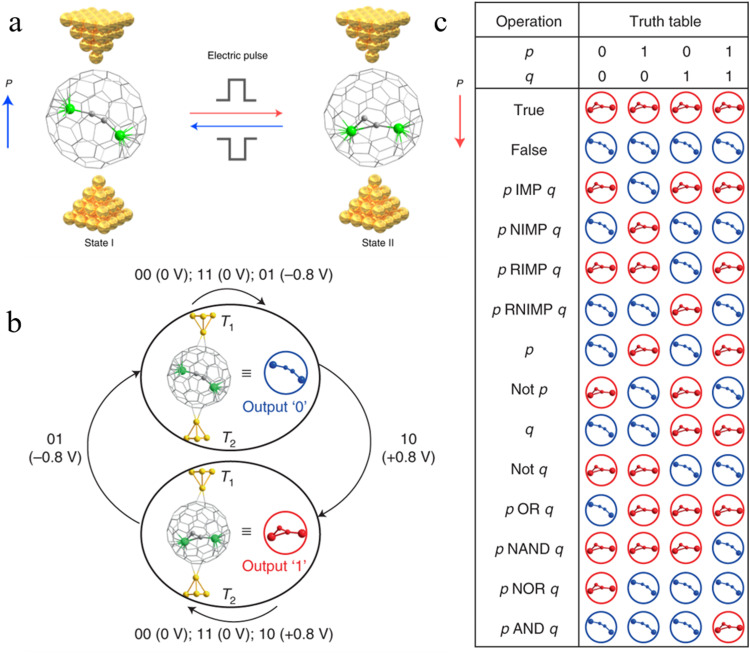

EMF molecules have gained attention due to their ability to attain room-temperature single electric dipole bistability. This is attributed to their capacity to modulate single permanent dipoles that reside within the fullerene cages. Theoretical calculations have also played a crucial role in elucidating the appropriateness of the encapsulation energy and chemical bonding energy between a Sc3+ ion and the fullerene cage, thereby confirming their potential for achieving room-temperature switching [136]. Very recently, logic-in-memory operations based on the manipulation of a single electric dipole, were successfully demonstrated by Xie and co-authors for Sc2C2@Cs(hept)-C88 (Fig. 12) [137]. It is noteworthy that this endohedral exhibits distinguishable electrical read-out signals due to its favorable room-temperature stability and asymmetry resulting from the presence of the unique heptagonal ring. Furthermore, the disordered Sc2C2 cluster possesses a quasi-permanent dipole, enabling its rotation within the cage under the influence of an applied electric field. The application of a low voltage range of ±0.8 V to the single-metallofullerene junction enabled the reversible encoding and storage of digital information through controlled manipulation of the independent permanent dipole of Sc2C2 within the Cs(hept)-C88 cage. As a result, 14 distinct Boolean logic functions were experimentally implemented in the single-Sc2C2@Cs(hept)-C88 devices (Fig. 12). In-depth theoretical findings show that the origin of the non-volatile memory behavior stems from the reorientation of the Sc2C2 group's dipole within the fullerene cage, induced by an applied electric field. In addition, the presence of non-volatile memory characteristics in another two carbide cluster metallofullerenes, namely Sc2C2@D2d(23)-C84 and Sc2C2@C2v(9)-C86, suggests that EMFs with an enclosed single dipole group hold great promise as potential candidates for the design of single-molecule binary logic-in-memory devices. This pioneering demonstration marks a significant advancement in the development of room-temperature electrically controlled in-memory logic devices, paving the way for the development of nanoelectronic devices for in-memory computing.

Fig. 12.

Room-temperature logic-in-memory single-metallofullerene (Sc2C2@Cs(hept)-C88) device[137]. (a) Different single Sc2C2@Cs(hept)-C88 junction configurations when states I and II are embedded in two-terminal gold electrodes. (b) Logic operations of the single-metallofullerene device. (c) The truth table of 14 fundamental Boolean logic functions implemented in the single-Sc2C2@Cs(hept)-C88 devices. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature.

7. Conclusion and perspective

Endohedral metallofullerenes provide an exceptional platform for the exploration of the distinctive structures and properties of metallic species that are not attainable in conventional systems outside the confinement of fullerene cages. However, the development of novel EMFs is significantly hindered by challenges associated with their synthesis and purification. In contrast to the conventional arc-discharge method, which yields EMFs in low quantities within the carbon soot, the combustion method provides novel insights into the macroscopic synthesis of desired EMF species, particularly those with non-classical cage structures. Alternatively, the development of purification protocols that circumvent the need for HPLC process, such as supramolecular purification strategies utilizing nanocapsules, offers an effective approach for selectively capturing specific EMF compounds. To date, various types of metallofullerenes have been successfully synthesized and isolated. The diversity of the encapsulated metal species gives rise to new structures and distinct properties. Firstly, intriguing phenomena related to the bonding inside and outside the fullerene cages have been observed, providing fresh insights into coordination chemistry. On one hand, a surprising regioselective dimerization process is observed for a pair of paramagnetic mono-EMFs, specifically M@C82 (M = Y, Er, Ce), through simple co-crystallization with NiII(OEP), indicating a bonding behavior influenced by spin interactions. On the other hand, direct metal-metal bonding is detected between the two M2+ ions (M = Lu, Y, Er) in the resulting di-EMFs, offering valuable knowledge regarding the coordination interactions between metals and carbon elements. Secondly, the encapsulation of transition metals (Ti, V) and actinide metals (Th, U) into fullerene cages holds significant importance as their strong coordination ability to interact with non-metal atoms (C, N, O, S) would stimulate research into the formation of new metal clusters with desired bonding features that researchers have been seeking for a considerable period of time. Various examples have been presented, such as the formation of unexpected C3-rings with cyclopropane-like geometry, C C triple bonds, M=X double bonds (where M = Ti, V, U, Th and X = C, N, O), and U N triple bonds. Thirdly, the ongoing exploration of these novel EMF structures holds the promise of bridging the existing gaps in the proposed growth maps, ultimately yielding substantial evidence that establishes a reliable growth mechanism for EMFs. Enhanced understanding of the formation mechanism for EMFs will lead to further optimization of synthetic protocols, resulting in higher yields and the discovery of novel structures with unique properties. Last but not least, the exceptional electronic structures of the internal metal moieties and their remarkable interactions with the fullerene cage give rise to multifunctional properties, paving the way for promising applications of EMFs in a wide range of fields, including biomedicine, single-molecule magnets, electronic devices.

Significantly, recent advancements in the field of fullerenes offer a fresh perspective in the realm of designing high-performance electrocatalysts, such as the Pt/C60 single-atom catalyst and the C60—Cu/SiO2 catalyst. These breakthroughs point towards a novel approach to surmount the limitations faced by conventional catalysts. Furthermore, the successful synthesis of polymeric fullerene layers exhibiting intriguing electronic and magnetic properties opens up avenues for potential applications in transistors, energy storage devices, superconductors, confined light systems, and quantum-materials-based devices. The development of functionalized fullerene complexes will also offer new perspectives into the application of fullerenes in the field of next-generation batteries. A notable example is the incorporation of nitro groups into the C60 cage, resulting in nitrofullerenes [138]. These nitrofullerenes exhibit excellent compatibility with various electrolytes, thereby serving as effective additives that greatly enhance the reversible and electrochemical performance of sodium metal batteries. Likewise, a recently introduced C60-S supramolecular complex, featuring high-density active sites for the adsorption and electrochemical conversion of lithium polysulfides (LiPSs), was applied as a stable cathode material for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries.139 In line with this trajectory, there is high anticipation for the invention of a new generation of EMF-based catalysts, EMF electrolyte additives, EMF-S cathodes and EMF functional materials. The ongoing exploration of their molecular devices, characterized by unprecedented properties due to the existence of metal moieties, holds the potential to unveil a vast realm of boundless opportunities across diverse applications.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (22201227, 21925104, 92261204) and Qin Chuang Yuan Program of Shaan Xi Province (2021QCYRC4-37) is greatly acknowledged. L. E. thanks the Robert A. Welch Foundation (AH-0033) for an endowed chair and the U.S. NSF (CHE-1801317) for generous financial support.

Biographies

Wenting Cai is currently an associate professor at Xi'an Jiaotong University. She is the recipient of The Young Talent Support Plan of Xi'an Jiaotong University (2021). Her research interests include the generation and characterization of synthetic carbon allotropes, along with exploring their potential applications in single-molecule magnets and electrocatalysis. Her research work has been published in the high-impact journals including Nature Energy, J. Am. Chem. Soc.

Luis Echegoyen served as the Robert A. Welch Professor of Chemistry at the University of Texas at El Paso from August 2010 until his retirement in 2021 and was President of the American Chemical Society in 2020. Luis was also the Director of the Chemistry Division of the National Science Foundation from August 2006 until August 2010 and served as Chair for the Department of Chemistry at Clemson University from 2002 until 2006. Luis has published > 515 articles, including 49 book chapters.

Xing Lu(BRID: 09855.00.12903) is a full professor in Huazhong University of Science and Technology. He is the recipient of The Ambassador Award from Chinese Embassy in Japan (2009), The Osawa Award from Fullerenes and Nanotubes Research Society of Japan (2011) and The National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (2019). His research interests lie in the rational design and facile generation of novel hybrid carbon materials with applications in energy storage and conversion. He has published more than 200 peer-reviewed papers in international journals with > 50 at J. Am. Chem. Soc. and Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.

Contributor Information

Luis Echegoyen, Email: echegoyen@utep.edu.

Xing Lu, Email: lux@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Kroto H.W., Heath J.R., O'Brien S.C., et al. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature. 1985;318(6042):162–163. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsch A., et al. The era of carbon allotropes. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:868–871. doi: 10.1038/nmat2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu X., Feng L., Akasaka T., et al. Current status and future developments of endohedral metallofullerenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41(23):7723–7760. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35214a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang S., Liu F., Chen C., et al. Fullerenes encaging metal clusters-clusterfullerenes. Chem. Commun. 2011;47(43):11822–11839. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12318a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Popov A.A., Yang S., Dunsch L., et al. Endohedral fullerenes. Chem. Rev. 2013;113(8):5989–6113. doi: 10.1021/cr300297r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heath J.R., Obrien S.C., Zhang Q., et al. Lanthanum complexes of spheroidal carbon shells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107(25):7779–7780. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chai Y., Guo T., Jin C.M., et al. Fullerenes with metals inside. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95(20):7564–7568. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson R.D., de Vries M.S., Salem J., et al. Electron paramagnetic resonance studies of lanthanum-containing C82. Nature. 1992;355(6357):239–240. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai W., Chen C.-H., Chen N., et al. Fullerenes as nanocontainers that stabilize unique actinide species inside: Structures, formation, and reactivity. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019;52(7):1824–1833. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geim A.K., Novoselov K.S., et al. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007;6(3):183–191. doi: 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Q.H., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Kis A., et al. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotech. 2012;7(11):699–712. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L., Yu Y., Ye G.J., et al. Black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nat. Nanotech. 2014;9(5):372–377. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novoselov K.S., Geim A.K., Morozov S.V., et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science. 2004;306(5696):666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1102896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan Q., Yan L., Tripp M.W., et al. Biphenylene network: A nonbenzenoid carbon allotrope. Science. 2021;372(6544):852–856. doi: 10.1126/science.abg4509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolmer M., Steiner A.K., Izydorczyk I., et al. Rational synthesis of atomically precise graphene nanoribbons directly on metal oxide surfaces. Science. 2020;369(6503):571–575. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H., Xue Y., Li Y., et al. Graphdiyne and its assembly architectures: Synthesis, functionalization, and applications. Adv. Mater. 2019;31(42) doi: 10.1002/adma.201803101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakharev P.V., Huang M., Saxena M., et al. Chemically induced transformation of chemical vapour deposition grown bilayer graphene into fluorinated single-layer diamond. Nat. Nanotech. 2020;15(1):59–66. doi: 10.1038/s41565-019-0582-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toh C.T., Zhang H., Lin J., et al. Synthesis and properties of free-standing monolayer amorphous carbon. Nature. 2020;577(7789):199–203. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1871-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makarova T.L., Sundqvist B., Höhne R., et al. Magnetic carbon. Nature. 2001;413(6857):716–718. doi: 10.1038/35099527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu C.H., Scuseria G.E., et al. Theoretical predictions for a two-dimensional rhombohedral phase of solid C60. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995;74(2):274–277. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okada S., Saito S., et al. Electronic structure and energetics of pressure-induced two-dimensional C60 polymers. Phys. Rev. B. 1999;59(3):1930–1936. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou L., Cui X., Guan B., et al. Synthesis of a monolayer fullerene network. Nature. 2022;606(7914):507–510. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04771-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meirzadeh E., Evans A.M., Rezaee M., et al. A few-layer covalent network of fullerenes. Nature. 2023;613(7942):71–76. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05401-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon P., Gogotsi Y., et al. Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 2008;7(11):845–854. doi: 10.1038/nmat2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao Y., Fatemi V., Fang S., et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature. 2018;556(7699):43–50. doi: 10.1038/nature26160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burlingame Q., Coburn C., Che X., et al. Centimetre-scale electron diffusion in photoactive organic heterostructures. Nature. 2018;554(7690):77–80. doi: 10.1038/nature25148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma'Mari F.A., Moorsom T., Teobaldi G., et al. Beating the Stoner criterion using molecular interfaces. Nature. 2015;524(7563):69–73. doi: 10.1038/nature14621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng J., Huang L., Cui C.-H., et al. Ambient-pressure synthesis of ethylene glycol catalyzed by C60-buffered Cu/SiO2. Science. 2022;376(6590):288–292. doi: 10.1126/science.abm9257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang R., Li Y., Zhou X., et al. Single-atomic platinum on fullerene C60 surfaces for accelerated alkaline hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2023;14(1):2460. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38126-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C., Shen W., Guo K., et al. A pentagonal defect-rich metal-free carbon electrocatalyst for boosting acidic O2 reduction to H2O2 production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145(21):11589–11598. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c00689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo K., He Z., Lu S., et al. A fullerene seeded strategy for facile construction of nitrogen-doped carbon nano-onions as robust electrocatalysts. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023;33(29) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kratschmer W., Lamb L.D., Fostiropoulos K., et al. Solid C60-a new form of carbon. Nature. 1990;347(6291):354–358. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haufler R.E., Conceicao J., Chibante L.P.F., et al. Efficient production of C60 (buckminsterfullerene), C60H36, and the solvated buckide ion. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94(24):8634–8636. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard J.B., McKinnon J.T., Makarovsky Y., et al. Fullerenes C60 and C70 in flames. Nature. 1991;352(6331):139–141. doi: 10.1038/352139a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johansson K.O., Head-Gordon M.P., Schrader P.E., et al. Resonance-stabilized hydrocarbon-radical chain reactions may explain soot inception and growth. Science. 2018;361(6406):997–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.aat3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao Z.Y., Jiang W.S., Sun D., et al. Synthesis of C3v-#1911C64H4 using a low-pressure benzene/oxygen diffusion flame: Another pathway toward non-IPR fullerenes. Combust. Flame. 2010;157(5):966–969. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weng Q.H., He Q., Liu T., et al. Simple combustion production and characterization of octahydro[60]fullerene with a non-IPR C60 cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132(43):15093–15095. doi: 10.1021/ja108316e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J.H., Gao Z.Y., Weng Q.H., et al. Combustion synthesis and electrochemical properties of the small hydrofullerene C50H10. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18(11):3408–3415. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]