Abstract

Objective

Our objective was to review the available literature on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) findings in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitides (AAV), evaluate its diagnostic utility, and assess its potential as a screening tool.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science from inception to March 29, 2023, following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. English‐language studies involving adult patients diagnosed with AAV—eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), or microscopic polyangiitis (MPA)—using recognized classification criteria were included. Studies had to report specific cMRI parameters in at least three patients. Three independent reviewers conducted study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment.

Results

Of 2,251 studies, 30 met the inclusion criteria, encompassing 1,149 patients with AAV (87% with EGPA, 13% with GPA, and 0.3% with MPA). The mean patient age was 52 ± 5 years, with 50.4% being female. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 55.6% ± 11.3%, and 29% of patients had an LVEF less than 50%. Myocardial fibrosis, indicated by late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), was present in 49% of patients, with predominantly subendocardial or endocardial (23%), intramyocardial (14%), and subepicardial (10%) patterns. Patients in remission (26%), when compared to those not in remission (74%), exhibited higher proportions of LGE (55% vs 47%) and glucocorticoid use (77% vs 68%), despite similar rates of abnormal electrocardiograms (44% vs 42%).

Conclusion

This systematic review reveals a high prevalence of myocardial fibrosis detected by cMRI in patients with AAV, even during remission. Significant subclinical cardiac involvement may be missed by conventional diagnostic methods, underscoring the utility of cMRI during routine evaluation.

INTRODUCTION

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitides (AAV) represent a group of systemic autoimmune diseases characterized by inflammation of small‐ to medium‐sized blood vessels. The primary subtypes of AAV include granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). 1 Recent advancements in classification criteria have improved the ability to accurately classify subtypes of AAV, guiding more tailored clinical and research approaches. For instance, the 2022 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/EULAR classification criteria for EGPA, GPA, and MPA have demonstrated improved sensitivity and specificity compared to the outdated 1990 ACR criteria. 2 , 3 , 4 Additionally, the 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference provided a more refined nomenclature and classification system, distinguishing among large, medium, and small vessel vasculitis, thereby facilitating more precise clinical and research applications. 1

SIGNIFICANCE & INNOVATIONS.

This study is the first to systematically review cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) findings in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitides (AAV).

cMRI revealed myocardial fibrosis in 49% of patients, even those in remission, highlighting subclinical cardiac involvement.

Incorporating cMRI into routine evaluations could improve the detection and management of cardiac involvement in patients with AAV.

Although EGPA, GPA, and MPA share overlapping immune‐mediated processes characterized by ANCA‐driven vascular inflammation, 5 EGPA differs by featuring prominent eosinophilic involvement. The management of AAV has been guided by comprehensive, evidence‐based recommendations, such as those developed by the ACR and the Vasculitis Foundation in 2021. These guidelines emphasize the use of rituximab over cyclophosphamide for remission induction in severe GPA and MPA due to its comparable efficacy and lower toxicity and recommend mepolizumab for remission induction in nonsevere EGPA cases. 6 Remission maintenance strategies also prioritize rituximab for severe GPA and MPA, while suggesting alternative immunosuppressives for EGPA, underscoring the importance of tailored therapeutic approaches based on disease severity and patient‐specific factors. 6

Cardiac involvement in AAV, although less common than renal or pulmonary involvement, poses significant diagnostic challenges. Conventional diagnostic tools such as electrocardiography (EKG) and echocardiography (TTE) may often fail to detect subtle myocardial abnormalities, especially in patients presenting with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). 7 , 8 This silent cardiac involvement can lead to underdiagnosis and delayed treatment, potentially resulting in adverse cardiovascular outcomes. 9 Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) emerges as a superior modality for identifying myocardial fibrosis, inflammation, and other subtle cardiac changes that are not readily apparent with traditional imaging techniques. 9 cMRI's ability to detect late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) allows for the visualization of myocardial scarring and fibrosis, which are critical markers of subclinical cardiac involvement. 10 The prognostic significance of LGE on cMRI has been well‐documented in other nonischemic cardiomyopathies, in which its presence correlates with increased risks of adverse cardiovascular events, including all‐cause death, heart failure hospitalization, and sudden cardiac death. 11 Despite these advancements, the specific role and utility of cMRI in the context of AAV remain underexplored. Given the potential for cMRI to uncover subclinical cardiac involvement in patients with AAV, a systematic evaluation of existing literature is essential to elucidate its diagnostic and prognostic value in this patient population. This systematic review aims to synthesize current evidence on cMRI findings in patients with AAV, evaluate the diagnostic utility of cMRI, and assess its potential as a routine screening tool to detect silent cardiac involvement that may be missed by conventional diagnostic methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy and information sources

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines 12 to ensure a comprehensive and transparent synthesis of the available evidence on cMRI findings in patients diagnosed with AAV, including EGPA, GPA, and MPA. A systematic literature search was performed across four major databases: PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search strategy for each database was predetermined and developed with the assistance of a medical librarian to ensure a comprehensive retrieval of relevant studies. Search terms were tailored to capture studies focusing on cMRI findings in adult patients diagnosed with AAV. The final search was executed on March 29, 2023. Detailed search strategies for each database are available in the Supplementary Material.

Eligibility criteria and study selection process

Studies were included if they involved adult (>18 years old) patients diagnosed with AAV (EGPA, GPA, or MPA) according to recognized classification criteria published by the ACR, EULAR, Chapel Hill Consensus Conference, and Lanham criteria. Different versions of these criteria were deemed acceptable depending on the study publication date. Some studies did not specify the exact criteria used but were included if they involved patients diagnosed with AAV based on recognized standards. The intervention (or exposure) involved the reporting of specific cMRI parameters. Outcomes of interest included detailed cMRI findings such as LVEF, LGE, myocardial swelling, and pericardial effusion. All study designs were considered, including cohort studies, cross‐sectional studies, and case series, provided they were published in English and reported cMRI parameters (at least LGE) in three or more patients. Exclusion criteria encompassed studies that reported incorrect outcomes, provided insufficient data, used inappropriate study designs, were non‐English publications, or involved unsuitable patient populations. Two independent reviewers (IK and UB) initially screened the titles and abstracts of all identified studies for relevance and eligibility. During this screening phase, studies were evaluated based on the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements between the primary reviewers were resolved by consulting a third reviewer. Following the initial screening, the full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed by two independent reviewers (IK and UB) to determine their suitability for inclusion in the review. The final decision to include or exclude studies was based on a thorough evaluation of each full‐text article against the established criteria. Any disagreements between the primary reviewers were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Three independent reviewers (IK, HA, and BC) conducted data extraction and bias assessments using predetermined forms to minimize subjective bias and ensure consistency. IK assessed all studies, while HA and BC each assessed half of the studies. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached. The extraction encompassed demographic information (age, sex, and other relevant details), relevant medical history, laboratory values, medications administered, measures of vasculitis disease severity, specific cMRI findings (such as LVEF, LGE, myocardial edema, and pericardial effusion), patient outcomes, and remission data based on Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) scoring or explicit statements by study authors.

The methodologic quality and potential risk of bias of the included studies were systematically evaluated using appropriate critical appraisal tools tailored to each study design, following recommendations from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS). 13 , 14 , 15 For cohort studies with control groups, the NOS was used, whereas cohort studies without control groups, cross‐sectional studies, and case series were appraised using the respective JBI critical appraisal checklists specific to each design. Scoring and categorization were performed accordingly. For the NOS, a maximum of 9 points was assigned; studies scoring 7 to 9 points were categorized as low risk of bias, 4 to 6 points as moderate risk, and 0 to 3 points as high risk. For the JBI checklists, items were scored as “yes,” “no,” or “unclear,” with studies achieving 75% or more of the total possible points classified as low risk of bias, 50% to 74% as moderate risk, and less than 50% as high risk. Bias assessments were performed only on full articles (21 of 30 included studies), as conference abstracts provided limited information, precluding adequate evaluation of methodologic quality. Detailed bias assessment tables for each selected study are included in the Supplementary Tables. Any modifications to the appraisal process during the review were documented and justified following best practices for systematic reviews. 12

Data synthesis and additional analyses

Because of the heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and reported outcomes, a meta‐analysis was not feasible. Instead, data were synthesized through comprehensive summary tables that organized key demographic, clinical, treatment, and cMRI findings. We performed a subgroup analysis between patients in remission—defined as a BVAS of less than or equal to 1, or by explicit statement of remission by the authors—and patients not in remission. The review did not include subgroup analyses based on different ANCA subtypes or perform sensitivity analyses.

Registration and deviations from the protocol

The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023464957) to ensure transparency and adherence to predefined methodologic standards. 12 Although our systematic review closely followed the methodology outlined in our registered PROSPERO protocol, certain deviations were necessary due to practical considerations encountered during the study. We were unable to perform subgroup analyses based on vasculitis subtypes, disease stage, specific cMRI parameters, and demographics as initially planned, owing to insufficient or inconsistent data reporting across the included studies. For the risk of bias assessment, we adapted our approach by using the JBI critical appraisal checklists alongside the NOS to appropriately evaluate the diverse study designs included (cohort studies without control groups, cross‐sectional studies, and case series). Although we intended to extract specific cMRI parameters such as left ventricular end diastolic volume, left ventricular end systolic volume, left ventricular mass, right ventricular ejection fraction, right ventricular end diastolic volume, right ventricular end systolic volume, native T1, extracellular volume, T2 ratio, and early gadolinium enhancement, these were not consistently reported across studies; therefore, our synthesis focused on the most commonly reported cMRI findings such as LVEF, LGE, myocardial edema, and pericardial effusion. Lastly, we did not assess publication bias as planned because of the heterogeneity of the studies and lack of sufficient comparable data.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the Supplementary Materials, including the data extraction forms, synthesized data tables, and bias assessment forms and tables. Further information may be provided from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

Study selection

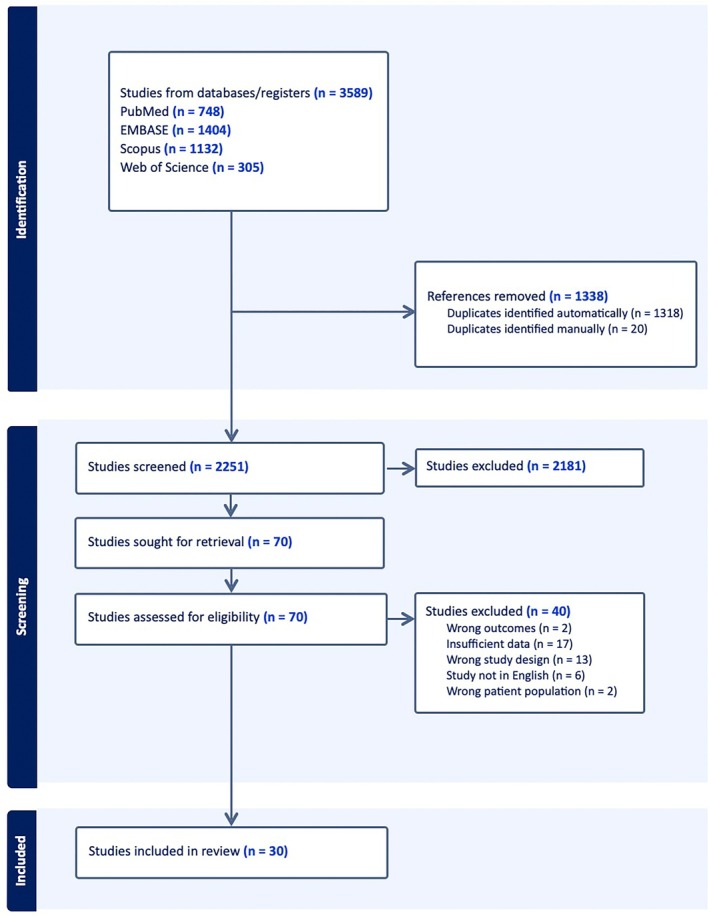

From the initial 3,589 studies, after removing duplicates (1,318 through automatic deduplication in EndNote and an additional 20 through manual deduplication), 2,251 unique studies remained. During the abstract screening process, 2,181 studies were excluded based on relevance and the predetermined eligibility criteria. The full texts of the remaining 70 studies were then assessed for eligibility. Exclusions at this stage were due to incorrect outcomes, 16 , 17 insufficient data, 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 inappropriate study design, 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 non‐English language, 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 and unsuitable patient population. 54 , 55 Ultimately, 30 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the review, 7 , 8 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

Study characteristics

A total of 30 studies published between 2005 and 2022 were included in the systematic review, encompassing 1,149 patients diagnosed with AAV, as shown in Table 1. The majority of the studies were cohort designs (n = 21), followed by cross‐sectional studies (n = 7) and case series (n = 2). Sample sizes varied across the studies, ranging from 7 to 176 patients. Most studies focused on evaluating cardiac involvement in patients with AAV using cMRI. The primary objectives included detecting myocardial damage, assessing the incidence and prevalence of cardiac involvement, evaluating the diagnostic utility of cMRI, and exploring its potential in early detection and risk stratification. Common findings across the studies indicated a high prevalence of myocardial fibrosis and cardiac abnormalities detected by cMRI in patients with AAV. Myocardial fibrosis was frequently observed even in patients without overt cardiac symptoms or with preserved LVEF.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies*

| Study ID | Ref no. | Year | Study design | AAV, n | Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goebel et al (2005) a | 3 | 2005 | Case series | 10 | cMRI identifies reversible and irreversible myocardial damage in EGPA |

| Cereda et al (2017) | 357 | 2017 | Cohort | 11 | Cardiac disease detection in EGPA |

| Dennert et al (2010) | 506 | 2010 | Cross‐sectional | 32 | Incidence of cardiac involvement in EGPA |

| Dunogué et al (2015) | 548 | 2015 | Cohort | 42 | Prognosis prediction via cMRI in EGPA |

| Fijolek et al (2016) | 624 | 2016 | Cohort | 33 | cMRI detects cardiac involvement, monitors treatment efficacy in EGPA |

| Garcia‐Vives et al (2021) | 677 | 2021 | Cohort | 131 | Universal cardiac screening improves early detection in EGPA |

| Giollo et al (2021) | 707 | 2021 | Cross‐sectional | 26 | cMRI identifies myocardial fibrosis, aiding risk stratification in GPA |

| Greulich et al (2016) | 740 | 2016 | Cross‐sectional | 63 | Prevalence and patterns of cardiac involvement in rheumatic disorders |

| Greulich et al (2017) a | 742 | 2017 | Cohort | 37 | Evaluation of myocardial involvement in patients with AAV using T1 and T2 mapping techniques |

| Hansch et al (2009) | 785 | 2009 | Cross‐sectional | 7 | Myocardial FPP abnormalities in patients with EGPA with cardiac involvement |

| Hazebroek et al (2015) | 814 | 2015 | Cohort | 91 | Prevalence and prognostic significance of cardiac involvement for death in patients with EGPA and GPA |

| Hinojar et al (2014) a | 837 | 2014 | Cohort | 7 | Elevated T1 and T2 values, indicating diffuse myocardial injury in systemic inflammatory disease |

| Hua et al (2022) a | 866 | 2022 | Cohort | 63 | Cardiac involvement was detected in 37% of patients with EGPA by cMRI |

| Lagan et al (2021) | 1,128 | 2021 | Cohort | 13 | Myocardial fibrosis was observed in patients with stable EGPA without pulmonary fibrosis or inflammation |

| Marmursztejn et al (2010) | 1,258 | 2010 | Case series | 8 | cMRI detected cardiac lesions in patients with EGPA, and immunosuppressive therapy reduced abnormalities in most cases |

| Marmursztejn et al (2013) | 1,260 | 2013 | Cohort | 20 | cMRI detected subclinical myocardial lesions in patients with EGPA, with FDG‐PET distinguishing between fibrosis and inflammation |

| Marmursztejn et al (2009) | 1,261 | 2009 | Cross‐sectional | 20 | cMRI with delayed enhancement detected myocardial involvement in patients with EGPA, regardless of symptoms |

| Marmursztejn et al (2006) a | 1,263 | 2006 | Cohort | 20 | cMRI identified myocardial inflammation, perfusion defects, and fibrosis in patients with EGPA, highlighting subclinical cardiac involvement |

| Mavrogeni et al (2013) | 1,297 | 2013 | Cohort | 28 | cMRI detected higher cardiac fibrosis in ANCA‐negative EGPA |

| Miszalski‐Jamka et al (2013) a | 1,363 | 2013 | Cohort | 50 | Cardiac involvement detected in 82% of patients with EGPA, often with subendocardial fibrosis |

| Miszalski‐Jamka et al (2013) | 1,366 | 2013 | Cohort | 21 | Subclinical myocardial involvement on cMRI is prevalent in patients with EGPA and GPA, despite normal EKG and TTE |

| Miszalski‐Jamka et al (2014) a | 1,367 | 2014 | Cohort | 51 | Nonsteroid immunosuppression reduces myocardial damage on cMRI and dysfunction in patients with EGPA |

| Miszalski‐Jamka et al (2011) a | 1,369 | 2011 | Cohort | 11 | cMRI showed involvement in 82% of patients with GPA, often with fibrosis and ongoing inflammation |

| Neumann et al (2009) | 1,471 | 2009 | Cohort | 49 | Endomyocarditis in EGPA correlates with ANCA negativity, worsening cardiac outcomes |

| Pugnet et al (2017) | 1,637 | 2017 | Cross‐sectional | 31 | cMRI revealed abnormalities in 61% of patients with GPA, primarily LGE |

| Sartorelli et al (2022) | 1,769 | 2022 | Cohort | 176 | cMRI revealed abnormalities in 40% of patients with EGPA, primarily LGE |

| Szczeklik et al (2011) | 1,976 | 2011 | Cross‐sectional | 20 | Cardiac involvement detected in 90% of patients with EGPA, often with fibrosis |

| Szczeklik et al (2015) a | 1,977 | 2015 | Cohort | 51 | Nonsteroid immunosuppressive therapy may limit cardiac damage in EGPA |

| Wassmuth et al (2008) | 2,143 | 2008 | Case series | 11 | cMRI effectively detects myocardial injury in EGPA, even with preserved LVEF |

| Yune et al (2016) | 2,230 | 2016 | Cohort | 16 | cMRI can detect myocardial GLE in patients with active EGPA, even in the absence of cardiac symptoms |

AAV, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitides; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; cMRI, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; EKG, electrocardiography; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; FPP, first pass perfusion; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; ID, identifier; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PET, positron emission tomography; Ref, reference; TTE, echocardiography.

These studies have been excluded from bias assessment due to inadequate information (conference abstracts).

Risk of bias in studies

Of the 30 included studies, 21 full‐text studies subjected to bias assessment, 8 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 72 , 75 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 82 , 83 as seen in Table 2. Nine conference abstracts provided limited information, precluding adequate evaluation of methodologic quality. 7 , 61 , 65 , 66 , 71 , 73 , 74 , 76 , 81 None of the evaluated studies were categorized as having a high risk of bias. Three studies (14%) were rated as low risk of bias, reflecting high methodologic quality with adequate selection processes, comparability, and outcome assessments. 8 , 56 , 62 The remaining 18 studies (86%) were deemed to have a moderate risk of bias. 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 63 , 64 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 72 , 75 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 82 , 83 Common methodologic limitations identified across studies included inadequate consideration of confounding factors, incomplete follow‐up reporting, and insufficient strategies to address confounding variables. Several studies did not explicitly identify or adjust for potential confounders, which could affect the internal validity of their findings. 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 63 , 64 , 68 , 70 , 77 , 79 , 83 Incomplete or unclear reporting of follow‐up and loss to follow‐up was observed in some studies. 67 , 72 , 75 , 77 , 79 , 83 Additionally, some studies lacked clarity in participant inclusion criteria and did not fully describe the study settings, which may affect the generalizability of the results. 64 , 69 , 82 Despite these limitations, most studies demonstrated strengths in other domains. Exposure and outcome measurements were conducted in valid and reliable ways, with standardized criteria and appropriate use of cMRI to detect cardiac involvement, in all studies but one. 82 All but two studies employed appropriate statistical analyses consistent with their study designs and objectives. 59 , 83 Detailed bias assessment for each study can be accessed in the Supplementary Tables.

Table 2.

Bias assessment overview*

| Study ID | Ref no. | Design | Assessment tool | Total score | Risk of bias | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereda et al (2017) | 357 | Cohort (control group) | NOS (9 points) | 7/9 | Low | Good selection and comparability |

| Dennert et al (2010) | 506 | Cross‐sectional | JBI (8 items) | 5/8 | Moderate | Confounding factors not identified |

| Dunogué et al (2015) | 548 | Cohort (no control group) | JBI (11 items) | 9/11 | Moderate | Confounding factors not addressed |

| Fijolek et al (2016) | 624 | Cohort (no control group) | JBI (11 items) | 7/11 | Moderate | Inadequate statistical analysis |

| Garcia‐Vives et al (2021) | 677 | Cohort (no control group) | JBI (11 items) | 9/11 | Moderate | Incomplete follow‐up |

| Giollo et al (2021) | 707 | Cross‐sectional | JBI (8 items) | 8/8 | Low | High methodologic quality |

| Greulich et al (2016) | 740 | Cross‐sectional | JBI (8 items) | 6/8 | Moderate | Confounding factors not addressed |

| Hansch et al (2009) | 785 | Cross‐sectional | JBI (8 items) | 5/8 | Moderate | Study setting not described |

| Hazebroek et al (2015) | 814 | Cohort (control group) | NOS (9 points) | 8/9 | Low | Comprehensive follow‐up |

| Lagan et al (2021) | 1,128 | Cohort (control group) | NOS (9 points) | 6/9 | Moderate | Incomplete follow‐up reporting |

| Marmursztejn et al (2009) | 1,261 | Cross‐sectional | JBI (8 items) | 6/8 | Moderate | Confounding factors not addressed |

| Marmursztejn et al (2010) | 1,258 | Case series | JBI (10 items) | 8/10 | Moderate | Incomplete participant inclusion |

| Marmursztejn et al (2013) | 1,260 | Cohort (no control group) | JBI (11 items) | 9/11 | Moderate | Confounding factors not addressed |

| Mavrogeni et al (2013) | 1,297 | Cohort (control group) | NOS (9 points) | 5/9 | Moderate | Loss to follow‐up not described |

| Miszalski‐Jamka et al (2013) | 1,366 | Cohort (control group) | NOS (9 points) | 5/9 | Moderate | Nonexposed cohort derivation not described |

| Neumann et al (2009) | 1,471 | Cohort (no control group) | JBI (11 items) | 7/11 | Moderate | Participants not free of outcome at baseline |

| Pugnet et al (2017) | 1,637 | Cross‐sectional | JBI (8 items) | 6/8 | Moderate | Confounding factors not addressed |

| Sartorelli et al (2022) | 1,769 | Cohort (no control group) | JBI (11 items) | 8/11 | Moderate | Confounding factors partially addressed |

| Szczeklik et al (2011) | 1,976 | Cross‐sectional | JBI (8 items) | 6/8 | Moderate | Confounding factors not addressed |

| Wassmuth et al (2008) | 2,143 | Case series | JBI (10 items) | 6/10 | Moderate | Inclusion criteria not clearly defined |

| Yune et al (2016) | 2,230 | Cohort (no control group) | JBI (11 items) | 7/11 | Moderate | Follow‐up completeness unclear |

Nine of 30 studies without full articles (conference abstracts) have been excluded from bias assessment due to inadequate information. ID, identifier; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute; NOS, Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale; Ref, reference.

Results of individual studies and results of syntheses

A total of 30 studies encompassing 1,149 patients with AAV were included in this systematic review. Among these patients, 87% of patients (n = 963) were diagnosed with EGPA, 13% of patients (n = 146) were diagnosed with GPA, and three patients were diagnosed with MPA, as shown in Table 3. The mean ± SD age was 52 ± 5 years, and the sex distribution was nearly equal, with 50.4% of patients (n = 532) being female. The comprehensive data extraction table detailing the results of each study was not included in the main text due to space limitations. However, this detailed table can be accessed in the Supplementary Material provided.

Table 3.

Demographic, clinical, and imaging characteristics by remission status. The asterisk applies to all values except Age.

| Patient characteristic | All patients | Remission | No remission |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients with AAV, n | 1,149 | 296 | 853 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 52 (5) | 51.2 (14.2) | 48.4 (11.5) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 532 (50.4) | 151 (51) | 381 (50) |

| Male | 522 (49.5) | 145 (49) | 377 (50) |

| Disease type, n (%) | |||

| EGPA | 963 (87) | 245 (83) | 718 (84) |

| GPA | 146 (13) | 51 (17) | 95 (11) |

| ANCA status, n (%) | |||

| ANCA+ | 308 (37) | 90 (49) | 218 (34) |

| ANCA− | 512 (61) | 94 (51) | 418 (66) |

| Clinical parameters | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 195 (25) | 78 (40) | 117 (20) |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 104 (18) | 44 (27) | 60 (15) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 60 (11) | 21 (13) | 39 (10) |

| Abnormal EKG, n (%) | 336 (43) | 68 (44) | 268 (42) |

| LVEF, mean % (SD) | 55.6 (11.3) | 54.7 (14.9) | 56.1 (8.3) |

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 558 (70) | 180 (77) | 378 (68) |

| Other immunosuppresion, n (%) | 484 (58) | 118 (50) | 366 (61) |

| Cardiac MRI parameters | |||

| Cardiac MRIs, n | 1,006 | 270 | 736 |

| Late GE, n (%) | 496 (49) | 149 (55) | 347 (47) |

| Subendocardial or endocardial, n (%) | 178 (23) | 54 (25) | 124 (22) |

| Intramyocardial, n (%) | 100 (14) | 39 (24) | 61 (11) |

| Subepicardial, n (%) | 55 (10) | 20 (28) | 35 (8) |

| No. of segments, mean (SD) | 7.2 (2.5) | 4.2 (7.6) | 6.2 (4.8) |

| Early GE, n (%) | 63 (20) | 1 (3) | 62 (22) |

| Pericardial effusion, n (%) | 132 (18) | 15 (9) | 117 (22) |

| Myocardial edema, n (%) | 65 (19) | 4 (4) | 61 (26) |

| Intraventricular thrombus, n (%) | 13 (5) | 3 (27) | 10 (4) |

Sex: denominators for female and male are based on the total number of patients. Disease type: denominators for EGPA and GPA are based on the total number of patients. ANCA status: denominators for ANCA+ and ANCA− are based on the total number of ANCA‐tested patients. Clinical parameters: denominators for all parameters are based on the total number of patients with available data. Cardiac MRI parameters: denominators for all parameters are based on the total number of patients with available MRI data. AAV, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitides; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; EKG, electrocardiography; GE, gadolinium enhancement; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Clinical characteristics and cMRI findings

The mean ± SD LVEF across all patients was 55.6% ± 11.3%, with 29% of patients (n = 133) exhibiting an LVEF below 50%, indicating varying degrees of ventricular function impairment. Hypertension was present in 25% of patients (n = 195), hyperlipidemia was present in 18% of patients (n = 104), and diabetes mellitus was present in 11% of patients (n = 60). Abnormal EKG findings were reported in 43% of patients (n = 336).

cMRI was performed on 1,006 patients. LGE was present in 49% of the patients (n = 496). The patterns of LGE involvement were predominantly subendocardial or endocardial (23%, n = 178), followed by intramyocardial (14%, n = 100) and subepicardial regions (10%, n = 55). The mean ± SD number of myocardial segments exhibiting LGE was 7.2 ± 2.5 based on the 17‐segment model, 84 suggesting extensive myocardial involvement in some patients. Early gadolinium enhancement, indicative of active inflammation, was observed in 20% of patients (n = 63). Pericardial effusion was detected in 18% of patients (n = 132), myocardial edema was detected in 19% of patients (n = 65), and intraventricular thrombus was detected in 5% of patients (n = 13). As shown in Table 4, most of the available cMRI data pertain to EGPA (870 scans in 963 patients), whereas fewer MRI scans were reported for GPA (133 scans in 146 patients) and MPA (3 scans in 3 patients). LGE was seen in approximately half of patients with EGPA (50.9%, n = 443) and 39.0% of patients with GPA (n = 52), with a notably higher proportion of intramyocardial or subepicardial involvement in the latter. Because of the small number of patients with MPA (n = 3), no meaningful cMRI subgroup analysis was feasible for that subtype.

Table 4.

Comparison of key cMRI findings in EGPA, GPA, and MPA subgroups 1. The asterisk applies to all values.

| Parameter | EGPA (n = 963) | GPA (n = 146) | MPA (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| cMRI, n | 870 | 133 | 3 |

| Late GE, n (%) | 443 (50.9) | 52 (39.0) | – |

| Subendocardial or endocardial | 171 (22.6) | 7 (30.4) | – |

| Intramyocardial | 88 (13.2) | 12 (38.7) | – |

| Subepicardial | 41 (10.0) | 14 (45.1) | – |

| Early GE, n (%) | 52 (21.3) | 11 (15.7) | – |

| Pericardial effusion, n (%) | 121 (18.7) | 11 (15.9) | – |

Denominators for all parameters are based on the total number of patients with available MRI data. Cells containing en dashes were data that could not be extracted. cMRI, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; GE, gadolinium enhancement; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Several studies specifically examined the discrepancy between normal EKG or TTE findings and abnormal cMRI results in patients with AAV. Overall, eight studies 8 , 58 , 59 , 64 , 69 , 70 , 75 , 78 reported that cMRI could detect subclinical myocardial involvement even when EKG and TTE appeared normal. Fijolek et al 59 observed that 39.4% of patients had a normal EKG and 36% of patients had a normal TTE, yet all patients (100%) had abnormal cMRI findings. Marmursztejn et al 70 (2013) found that 10 of 14 patients with abnormal cMRI still had a normal EKG, and 7 of 14 patients had a normal TTE. Similarly, Miszalski‐Jamka et al 75 reported that 81% of patients with otherwise normal EKG or TTE exhibited LGE on cMRI. Some studies also provided paired follow‐up cMRI data, suggesting that cMRI abnormalities may regress partially or completely following immunosuppressive therapy, although only a small number of patients underwent repeat imaging. 58 , 69 , 78

Comparison by remission status

When comparing patients in remission (26%, n = 296) to those not in remission (74%, n = 853), several notable differences emerged. A higher proportion of patients in remission exhibited LGE on cMRI compared to those not in remission (55% vs 47%, respectively). The rates of abnormal EKGs were similar between the two groups (44% in remission vs 42% not in remission). Patients in remission had a lower incidence of pericardial effusion (9% vs 22%) and myocardial edema (4% vs 26%) compared to those not in remission. The mean ± SD LVEF was slightly lower in patients in remission (54.7% ± 14.9%) compared to those not in remission (56.1% ± 8.3%). Regarding treatment, a higher percentage of patients in remission were receiving glucocorticoids (77%, n = 180) compared to those not in remission (68%, n = 378). Conversely, other immunosuppressive therapies were more commonly started in patients not in remission (61% vs 50%). Among the patients, 37% (n = 308) were ANCA‐positive, with a higher proportion of ANCA positivity observed in patients in remission (49% vs 34%). Hypertension and hyperlipidemia were more prevalent in patients in remission compared to those not in remission (hypertension: 40% vs 20%; hyperlipidemia: 27% vs 15%).

Synthesis of findings, reporting biases, certainty of evidence

The included studies consistently demonstrate a significant burden of subclinical cardiac involvement in AAV, particularly EGPA, as indicated by cMRI‐detected myocardial fibrosis even in patients who appear to be in clinical remission. This highlights the limitations of conventional diagnostic tools such as EKG and TTE, as well as the potential for irreversible cardiac damage if fibrosis persists. Although publication bias was not formally evaluated—largely due to heterogeneity in study populations, designs, and reported outcomes—most studies were deemed to have a moderate risk of bias, often stemming from inadequate control of confounders and variable cMRI protocols. Furthermore, the lack of randomized trials, reliance on observational data, and significant variability in patient characteristics limit the overall strength of the conclusions. Nevertheless, the repeated finding of LGE across multiple studies supports a reliable association between AAV and myocardial involvement, yielding a moderate level of certainty when weighing the consistency of results against methodologic constraints. Notably, we did not formally apply Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation because of the narrative synthesis required by the heterogeneity of the included studies.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate a high prevalence of subclinical cardiac involvement in AAV patients, as evidenced by cMRI. Nearly half of the patients (49%) exhibited LGE, even among those in clinical remission. This underscores the superior sensitivity of cMRI in uncovering cardiac abnormalities that conventional diagnostic methods, such as EKG and TTE, often fail to detect. Our results align with previous studies focusing on patients with EGPA. Cereda et al 56 reported that patients with EGPA in clinical remission exhibited significant myocardial fibrosis and reduced LVEF on cMRI, despite normal electrocardiogram findings. Similarly, Dunogué et al 58 found that 59.5% of patients with EGPA had myocardial anomalies on cMRI, with LGE being particularly prevalent in those with cardiomyopathy. Fijolek et al 59 demonstrated that all patients with EGPA in their cohort exhibited myocardial injury on cMRI, which was not detected by TTE or EKG.

Studies focusing on patients with GPA revealed similar patterns. Giollo et al 62 found that 32% of patients with GPA without known cardiovascular disease exhibited LGE indicative of myocardial fibrosis, which was absent in healthy controls. Greulich et al 7 , 63 reported that 43% of patients with AAV exhibited LGE and elevated native T1 and T2 mapping values were common, independent of LGE presence. Hazebroek et al 8 found that 61% of patients with GPA had cardiac abnormalities detectable by cMRI, even without evident cardiac symptoms. The pattern of LGE predominantly involved subendocardial or endocardial regions, consistent with findings from Goebel et al 61 and Marmursztejn et al, 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 indicating myocardial damage due to granulomatous inflammation and vasculitis.

Our review also highlights the significant impact of immunosuppressive therapy on cardiac involvement in patients with AAV. Fijolek et al 59 observed that after treatment with glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide, 81% of patients with EGPA showed improvements on cMRI, with some achieving complete remission, whereas Marmursztejn et al 69 reported significant regression or normalization of cMRI abnormalities in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, demonstrating that early and aggressive immunosuppressive treatment can reduce myocardial inflammation, limit the progression of fibrosis, and improve cardiac function. Similarly, our review found that patients in remission had a lower incidence of active myocardial inflammation markers, such as myocardial edema and pericardial effusion, compared to those not in remission, suggesting that immunosuppressive therapy effectively reduces ongoing myocardial inflammation. However, the persistence of LGE in a significant proportion of patients in remission (55%) indicates that myocardial fibrosis may continue or remain despite clinical improvement, highlighting the importance of early and aggressive treatment to prevent irreversible cardiac damage. The higher usage of glucocorticoids among patients in remission in our review (77% vs 68%) further supports the role of immunosuppressive therapy in achieving remission and mitigating cardiac involvement.

Furthermore, cardiac involvement detected by cMRI is associated with adverse outcomes and higher mortality rates. Hazebroek et al 8 linked cardiac involvement to significantly higher all‐cause and cardiovascular death, whereas Pugnet et al 78 noted that cardiac involvement was more prevalent in patients with longer disease duration and those experiencing disease relapse. Consistent with these findings, our review underscores the prognostic significance of cardiac involvement detected by cMRI. The high prevalence of myocardial fibrosis and its persistence during remission suggest that patients with cardiac involvement may be at increased risk of adverse outcomes, reinforcing the need for routine cardiac screening and early therapeutic interventions to improve long‐term prognosis. However, a potential indication bias must be acknowledged when interpreting higher LGE rates in patients classified as being in remission, as cMRI might be performed more often in individuals with previous or suspected cardiac complications. In addition, the decision to order advanced imaging may vary among treating physicians, further introducing selection bias. Future prospective and longitudinal studies with systematic cMRI screening—both in active disease and in remission—would help clarify the true prevalence and progression of cardiac involvement in AAV.

As previously discussed, the majority of the included studies were assessed as having a moderate risk of bias due to limitations such as inadequate consideration of confounding factors and incomplete follow‐up reporting. These methodologic shortcomings may influence the reliability of the synthesized findings. Specifically, the prevalence of myocardial fibrosis and other cardiac abnormalities could be affected by selection bias, measurement bias, and unaddressed confounders. The heterogeneity of study designs, patient populations, and cMRI protocols across studies also contributes to variability in the reported outcomes.

The studies included in this review have several limitations that may affect the interpretation of the findings. Many studies had small sample sizes, limiting the generalizability of the results. For instance, the study by Hansch et al 64 included 7 patients, the study by Yune et al 83 had 16 patients, and the study by Giollo et al 62 had 26 patients. The majority of studies were observational and cross‐sectional, making it difficult to establish causality or assess the progression of cardiac involvement over time. Methodologic limitations, such as heterogeneity in cMRI protocols and diagnostic criteria, were evident. Differences in imaging techniques, LGE assessment methods, and definitions of cardiac involvement can lead to variability in reported prevalence rates and hinder direct comparisons between studies. Some studies did not adequately control for confounding factors, such as comorbid cardiovascular risk factors and differences in disease severity or duration, which could influence cMRI findings. Moreover, cMRI findings in GPA should be interpreted in light of potential verification bias, as cMRI is often ordered only when cardiac involvement is suspected. Consequently, the prevalence of cardiac abnormalities in this subgroup may be artificially heightened compared to a more uniformly screened population. The risk of bias assessments indicated that most studies were of moderate quality, with potential biases related to selection, measurement, and confounding. The observational nature of these studies introduces the possibility of selection bias, and the lack of blinding may result in measurement bias.

Our systematic review has several limitations. We included only studies published in English, which may introduce language bias and exclude relevant research in other languages. Several included studies were conference abstracts with limited information, precluding a thorough assessment of methodologic quality. The heterogeneity among studies in terms of patient populations, disease activity, cMRI protocols, and reported outcomes limited our ability to perform a meta‐analysis, necessitating a narrative synthesis of the data. Additionally, the inclusion of studies with varying definitions of remission and inconsistent use of standardized disease activity scores may affect the comparability of findings related to disease activity and cardiac involvement. The reliance on published data limits the ability to explore individual patient data or unpublished outcomes that could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the prognostic significance of cardiac involvement in AAV.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of cMRI findings in patients with AAV. The high prevalence of subclinical myocardial fibrosis detected by cMRI in patients with AAV underscores the need for routine cardiac assessment using advanced imaging techniques in this population. Clinicians should be aware that conventional diagnostic methods may not be sufficient to detect early cardiac involvement. Incorporating cMRI into the standard evaluation of patients with AAV, even those in clinical remission or without cardiac symptoms, may facilitate early detection and intervention, potentially improving long‐term cardiovascular outcomes. Policy‐wise, guidelines for the management of AAV should consider recommending cMRI as a valuable tool for cardiac assessment. Insurance coverage and resource allocation for advanced cardiac imaging in this patient population may need to be addressed to ensure accessibility. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to assess the progression of myocardial fibrosis over time and its impact on clinical outcomes. Randomized controlled trials investigating the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions in reducing myocardial fibrosis detected by cMRI would provide valuable insights. Standardization of cMRI protocols and diagnostic criteria should be established to enhance comparability across studies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to at least one of the following manuscript preparation roles: conceptualization AND/OR methodology, software, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, visualization, and validation AND drafting or reviewing/editing the final draft. As corresponding author, Dr Karageorgiou confirms that all authors have provided the final approval of the version to be published and takes responsibility for the affirmations regarding article submission (eg, not under consideration by another journal), the integrity of the data presented, and the statements regarding compliance with institutional review board/Declaration of Helsinki requirements.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supplementary Bias_Assessment_Tables_detailed

Appendix S2: Supplementary Master_data_extraction

Appendix S3: Supplementary Study protocol‐2

AAVcMRI search strategy.

Disclosure form.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Ashbina Pokharel for her invaluable contribution to the abstract screening process as an arbitrator. Additionally, we extend our heartfelt thanks to Courtney Mandarino, our institution's librarian, whose expertise in formulating the search strategy, querying the databases, and acquiring articles was vital to the success of this study.

1Ioannis Karageorgiou, MD, Unnati Bhatia, MBBS, Hazem Alakhras, MD, Berk Celik, MD: Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital, Royal Oak, Michigan; 2Alexandra Halalau, MD, MSc: Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital, Royal Oak, and Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Rochester, Michigan.

Additional supplementary information cited in this article can be found online in the Supporting Information section (https://acrjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr2.70026).

Author disclosures are available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr2.70026.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jennette JC. Overview of the 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013;17(5):603–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grayson PC, Ponte C, Suppiah R, et al; DCVAS Study Group. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022;74(3):386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robson JC, Grayson PC, Ponte C, et al; DCVAS Study Group . 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022;74(3):393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Suppiah R, Robson JC, Grayson PC, et al; DCVAS INVESTIGATORS. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology classification criteria for microscopic polyangiitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022;74(3):400–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jennette JC, Falk RJ. Pathogenesis of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody‐mediated disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014;10(8):463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chung SA, Langford CA, Maz M, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody‐Associated Vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73(8):1366–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greulich S, Mayr A, Kitterer D, et al. T1 and T2 mapping for evaluation of myocardial involvement in patients with ANCA‐associated vasculitides. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017;19(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hazebroek MR, Kemna MJ, Schalla S, et al. Prevalence and prognostic relevance of cardiac involvement in ANCA‐associated vasculitis: eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Int J Cardiol 2015;199:170–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karamitsos TD, Francis JM, Myerson SG, et al. The role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54(15):1407–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferreira VM, Schulz‐Menger J, Holmvang G, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in nonischemic myocardial inflammation: expert recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72(24):3158–3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuruvilla S, Adenaw N, Katwal AB, et al. Late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance predicts adverse cardiovascular outcomes in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7(2):250–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372(71):n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta‐analyses. The Ottawa Hospital. 2013. Accessed March 12, 2025. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, et al, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2024. Accessed March 12, 2025. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355598596/7.+Systematic+reviews+of+etiology+and+risk [Google Scholar]

- 15. Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth 2020;18(10):2127–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mavrogeni S, Manoussakis MN, Karagiorga TC, et al. Detection of coronary artery lesions and myocardial necrosis by magnetic resonance in systemic necrotizing vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61(8):1121–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rednic D, Rancea R, Cozma F, et al. AB0557 heart lesson in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1245–1246.28073801 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Allen SD, Harvey CJ. Imaging of Wegener's granulomatosis. Br J Radiol 2007;80(957):757–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. d'Ersu E, Ribi C, Monney P, et al. Churg‐Strauss syndrome with cardiac involvement: case illustration and contribution of CMR in the diagnosis and clinical follow‐up. Int J Cardiol 2018;258:321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edwards NC, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, et al. Myocardial disease in systemic vasculitis and autoimmune disease detected by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(7):1208–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Egan A, Bond M, Jayne D. Cardiovascular disease in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Rheumatology 2019;58(Suppl 2):kez063.019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Egan AC, Bosch TB, Jayne DR. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis cardiac disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;30:1147.31208985 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eyler AE, Ahmad FA, Jahangir E. Magnetic resonance imaging of the cardiac manifestations of Churg‐Strauss. JRSM Open 2014;5(4):2054270414525370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grinnell M, Zhao M, O'Dell J, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis cardiomyopathy versus myocardial infarction: value of magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography for differentiation. J Clin Rheumatol 2021;27(6):e210–e212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guillevin L, Mahr A, Cohen P, et al. CSS phenotypes: are MRI‐detected cardiac anomalies associated with ANCA negativity? Clin Exp Immunol 2011;164:70. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mavrogeni S, Gialafos E, Karabela G, et al. “The silence of lambs”: cardiac lesions in asymptomatic immune‐mediated diseases detected by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Int J Cardiol 2013;168(3):2901–2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mavrogeni S, Markousis‐Mavrogenis G, Koutsogeorgopoulou L, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging pattern at the time of diagnosis of treatment naïve patients with connective tissue diseases. Int J Cardiol 2017;236:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mavrogeni S, Sfikakis PP, Gialafos E, et al. Cardiac tissue characterization and the diagnostic value of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in systemic connective tissue diseases. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(1):104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miszalski‐Jamka T, Szczeklik W, Sokołowska B, et al. Noncorticosteroid immunosuppression limits myocardial damage and contractile dysfunction in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg‐Strauss syndrome). J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65(1):103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pakbaz M, Pakbaz M. Cardiac involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a meta‐analysis of 62 case reports. J Tehran Heart Cent 2020;15(1):18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sartorelli S, Cohen P, Dunogue B, et al. Cardiac involvement of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg‐Strauss): initial manifestations and outcomes based on data from a monocenter patient cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:3006–3007. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zampieri M, Beltrami M, Emmi G, et al. Cardiac involvement in Churg Strauss syndrome: an update on cardiological manifestations. Eur Heart J Suppl 2019;21:J177. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zampieri M, Beltrami M, Fumagalli C, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, a new recurrent feature in an extremely rare disease. Eur Heart J 2020;41(Suppl 2):ehaa946.2067. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zampieri M, Emmi G, Beltrami M, et al. Cardiac involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Churg‐Strauss syndrome): prospective evaluation at a tertiary referral centre. Eur J Intern Med 2021;85:68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Al Umairi RS, Al Manei K, Al Lawati F, et al. Cardiac involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg‐Strauss Disease): the role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2021;21(4):644–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kane GC, Keogh KA. Involvement of the heart by small and medium vessel vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2009;21(1):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mavrogeni SI, Dimitroulas T, Kitas GD. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis and management of cardiac and vascular involvement in the systemic vasculitides. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2019;31(1):16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mavrogeni S, Markousis‐Mavrogenis G, Kolovou G. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance for evaluation of heart involvement in ANCA‐associated vasculitis. A luxury or a valuable diagnostic tool? Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2014;13(5):305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mavrogeni SI, Sfikakis PP, Dimitroulas T, et al. Can cardiovascular magnetic resonance prompt early cardiovascular/rheumatic treatment in autoimmune rheumatic diseases? Current practice and future perspectives. Rheumatol Int 2018;38(6):949–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Medford AR. Churg‐Strauss syndrome: remember cardiac complications too. Clin Med (Lond) 2013;13(3):321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moosig F, Richardt G, Gross WL. A fatal attraction: eosinophils and the heart. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52(4):587–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mukhtyar CB, Flossmann O, Luqmani RA. Clinical and biological assessment in systemic necrotizing vasculitides. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2006;24(2)(suppl 41):S92–S99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Raman SV, Aneja A, Jarjour WN. CMR in inflammatory vasculitis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2012;14(1):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sanchez F, Gutierrez JM, Kha LC, et al. Pathological entities that may affect the lungs and the myocardium. Evaluation with chest CT and cardiac MR. Clin Imaging 2021;70:124–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sierra‐Galan LM, Bhatia M, Alberto‐Delgado AL, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance in rheumatology to detect cardiac involvement since early and pre‐clinical stages of the autoimmune diseases: a narrative review. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022;9:870200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Życińska K, Borowiec A. Cardiac manifestations in antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA) ‐ associated vasculitides. Kardiol Pol 2016;74(12):1470–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zekić T. Cardiac involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Rheumatol Int 2018;38(4):705–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Belhassen A, Toujani S, El Ouni A, et al. Caractéristiques de l'atteinte cardiaque au cours de la granulomatose éosinophilique avec polyangéite. [Characteristics of cardiac involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis]. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 2022;71(2):95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Breuckmann K, Breuckmann F, Nassenstein K, et al. MR‐tomographische Darstellung einer Endomyokardfibrose als kardiale Manifestationsform bei Churg‐Strauss‐Syndrom. [MR imaging of endomyocardial fibrosis representing cardiac involvement in Churg‐Strauss syndrome]. Herz 2007;32(1):71–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fijołek J, Wiatr E, Gawryluk D, et al. Podstawy rozpoznania zespołu Churga‐Strauss w materiale własnym. [The basis of Churg‐Strauss syndrome diagnosis in own material]. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2012;80(1):20–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sauvetre G, Fares J, Caudron J, et al. Intérêt de l'imagerie par résonance magnétique nucléaire au cours de l'atteinte cardiaque du syndrome de Churg‐Strauss. Trois observations et revue de la littérature. [Usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging in Churg‐Strauss syndrome related cardiac involvement. A case series of three patients and literature review]. Rev Med Interne 2010;31(9):600–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vignaux O, Marmursztejn J, Cohen P, et al. Imagerie cardiaque dans les vascularites associées aux ANCA. [Cardiac imaging in ANCA‐associated vasculitis]. Presse Med 2007;36(5 Pt 2):902–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang J, Yin L. Imaging findings of cardiac involvement in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody‐associated vasculitis. Chinese Journal of Medical Imaging Technology 2022;38(3):460–463. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Merten C, Beurich HW, Zachow D, et al. Cardiac involvement in hypereosinophilic syndromes detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J 2013;34(suppl 1):643–644. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Merten C, Beurich H, Zachow D, et al. Cardiac involvement in hypereosinophilic syndromes detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015;17:Q75. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cereda AF, Pedrotti P, De Capitani L, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of cardiac involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) with cardiac magnetic resonance. Eur J Intern Med 2017;39:51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dennert RM, van Paassen P, Schalla S, et al. Cardiac involvement in Churg‐Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62(2):627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dunogué B, Terrier B, Cohen P, et al; French Vasculitis Study Group. Impact of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging on eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis outcomes: a long‐term retrospective study on 42 patients. Autoimmun Rev 2015;14(9):774–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fijolek J, Wiatr E, Gawryluk D, et al. “The significance of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in detection and monitoring of the treatment efficacy of heart involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis patients.” Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2016;33(1):51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Garcia‐Vives E, Rodriguez‐Palomares JF, Harty L, et al. Heart disease in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) patients: a screening approach proposal. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60(10):4538–4547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Goebel U, Wassmuth R, Schulz‐Menger J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging detects myocardial damage in Churg‐Strauss syndrome. Kidney Blood Press Res 2005;28:153–202. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Giollo A, Dumitru RB, Swoboda PP, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of myocardial involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;37(3):1053–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Greulich S, Kitterer D, Kurmann R, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with rheumatic disorders: Data of the RHEU‐M(A)R study. Int J Cardiol 2016;224:37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hansch A, Pfeil A, Rzanny R, et al. First‐pass myocardial perfusion abnormalities in Churg‐Strauss syndrome with cardiac involvement. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;25(5):501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hinojar R, Foote L, Ucar EA, et al. Native T1 and T2 values by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients with systemic inflammatory conditions. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2014;16:251. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hua AX, Sularz A, Dhariwal J, et al. Detection of cardiac involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) with multiparametric cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR). Circulation 2022;146(suppl 1):A10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lagan J, Naish JH, Fortune C, et al. Myocardial involvement in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis evaluated with cardiopulmonary magnetic resonance. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;37(4):1371–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Marmursztejn J, Vignaux O, Cohen P, et al. Impact of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for assessment of Churg‐Strauss syndrome: a cross‐sectional study in 20 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009;27(1)(suppl 52):S70–S76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Marmursztejn J, Cohen P, Duboc D, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in Churg‐Strauss syndrome. Impact of immunosuppressants on outcome assessed in a prospective study on 8 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2010;28(1)(suppl 57):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Marmursztejn J, Guillevin L, Trebossen R, et al. Churg‐Strauss syndrome cardiac involvement evaluated by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and positron‐emission tomography: a prospective study on 20 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52(4):642–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Marmursztejn J, Vignaux O, Cohen P, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in patients with Churg‐Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:S489–S489. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mavrogeni S, Karabela G, Gialafos E, et al. Cardiac involvement in ANCA (+) and ANCA (‐) Churg‐Strauss syndrome evaluated by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2013;12(5):322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Miszalski‐Jamka T, Szczeklik W, Sokołowska B, et al. Cardiac involvement in Wegener's granulomatosis resistant to induction therapy. Eur Radiol 2011;21(11):2297–2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Miszalski‐Jamka T, Sokolowska B, Szczeklik W, et al. Cardiac involvement in subjects with Churg‐Strauss syndrome in clinical remission. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;14(suppl 1):i2. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Miszalski‐Jamka T, Szczeklik W, Sokołowska B, et al. Standard and feature tracking magnetic resonance evidence of myocardial involvement in Churg‐Strauss syndrome and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's) in patients with normal electrocardiograms and transthoracic echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;29(4):843–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Miszalski‐Jamka T, Szczeklik W, Sokołowska B, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy limits myocardial damage and contractile dysfunction in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg‐Strauss). Eur Heart J 2014;35:851–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Neumann T, Manger B, Schmid M, et al. Cardiac involvement in Churg‐Strauss syndrome: impact of endomyocarditis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88(4):236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pugnet G, Gouya H, Puéchal X, et al; French Vasculitis Study Group. Cardiac involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a magnetic resonance imaging study of 31 consecutive patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56(6):947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sartorelli S, Chassagnon G, Cohen P, et al; French Vasculitis Study Group (FVSG). Revisiting characteristics, treatment and outcome of cardiomyopathy in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Churg‐Strauss). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;61(3):1175–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Szczeklik W, Miszalski‐Jamka T, Mastalerz L, et al. Multimodality assessment of cardiac involvement in Churg‐Strauss syndrome patients in clinical remission. Circ J 2011;75(3):649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Szczeklik W, Miszalski‐Jamka T, Sokolowska B, et al. The influence of the immunosuppressive therapy on the cardiac function in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg‐Strauss) patients. Nephron 2015;129:45–249.25895550 [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wassmuth R, Göbel U, Natusch A, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging detects cardiac involvement in Churg‐Strauss syndrome. J Card Fail 2008;14(10):856–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Yune S, Choi DC, Lee BJ, et al. Detecting cardiac involvement with magnetic resonance in patients with active eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;32(S1)(suppl 1):155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, et al; American Heart Association Writing Group on Myocardial Segmentation and Registration for Cardiac Imaging. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation 2002;105(4):539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supplementary Bias_Assessment_Tables_detailed

Appendix S2: Supplementary Master_data_extraction

Appendix S3: Supplementary Study protocol‐2

AAVcMRI search strategy.

Disclosure form.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the Supplementary Materials, including the data extraction forms, synthesized data tables, and bias assessment forms and tables. Further information may be provided from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.