Abstract

Coral populations worldwide are declining rapidly due to elevated ocean temperatures and other human impacts. The Caribbean harbors a high number of threatened, endangered, and critically endangered coral species compared with reefs of the larger Indo-Pacific. The reef corals of the Caribbean are also long diverged from their Pacific counterparts and may have evolved different survival strategies. Most genomic resources have been developed for Pacific coral species which may impede our ability to study the changes in genetic composition of Caribbean reef communities in response to global change. To help fill the gap in genomic resources, we used PacBio HiFi sequencing to generate the first genome assemblies for 3 Caribbean reef-building corals, Colpophyllia natans, Dendrogyra cylindrus, and Siderastrea siderea. We also explore the genomic novelties that shape scleractinian genomes. Notably, we find abundant gene duplications of all classes (e.g. tandem and segmental), especially in S. siderea. This species has one of the largest genomes of any scleractinian coral (822 Mb) which seems to be driven by repetitive content and gene family expansion and diversification. As the genome size of S. siderea was double the size expected of stony corals, we also evaluated the possibility of an ancient whole-genome duplication using Ks tests and found no evidence of such an event in the species. By presenting these genome assemblies, we hope to develop a better understanding of coral evolution as a whole and to enable researchers to further investigate the population genetics and diversity of these 3 species.

Keywords: genome, coral, reef, gene family expansion, duplication, orthogroups, Siderastrea siderea, Dendrogyra cylindrus, Colpophyllia natans

Introduction

Genomic resources are increasingly available for Pacific reef-building corals (e.g. Fuller et al. 2020; Stephens et al. 2022), yet most Caribbean coral species still lack them despite genetic management of their populations becoming necessary (Baums et al. 2022). Caribbean reefs represent ecosystems long diverged from Pacific counterparts. During the mid-Miocene, the Mediterranean closed off at both ends and the eastern connection of the Caribbean with the Indo-Pacific basin was severed (Wallace and Rosen 2006). The Isthmus of Panama to the west of the Caribbean remained open until roughly 3 million years ago, after which ocean circulation drastically changed and Caribbean reefs were isolated from Pacific reefs (Burton et al. 1997; O’Dea et al. 2016).

Cnidarians diverged early in metazoan evolution roughly 700 MYA (Park et al. 2012), and the 3 species discussed here represent the 2 major scleractinian lineages, complex (Siderastrea siderea) and robust (Colpophyllia natans and Dendrogyra cylindrus). D. cylindrus is a rare Caribbean coral (Hunter and Jones 1996) that has declined sharply in the past 2 decades due anthropogenic stressors and a highly infectious disease called stony coral tissue loss disease (Brandt et al. 2021). D. cylindrus is extinct in the wild in Florida and is considered critically endangered (Neely et al. 2021; Cavada-Blanco et al. 2022). S. siderea and C. natans were common reef-building corals that have also experienced significant declines in response to disease and anthropogenic impacts. S. siderea is now listed as critically endangered (Rodriguez-Martinez et al. 2022) and under threat due to acidification, ocean warming (Horvath et al. 2016), and stony coral tissue loss disease (Brandt et al. 2021). C. natans is also in decline due to stony coral tissue loss disease (Vermeij and Goergen 2022; Williamson et al. 2022). Despite their ecological and evolutionary importance, genomic resources are not yet available for these species.

Coral genomes are variable in size (e.g. Stephens et al. 2022), but have highly conserved gene order (Ying et al. 2018; Locatelli et al. 2024). Anthozoan genomes contain between 13.57 and 52.2% repetitive content (e.g. Shinzato et al. 2011; Bongaerts et al. 2021) and harbor DNA and retrotransposons that are still active (Chapman et al. 2010; Huang et al. 2012), which can result in gene duplication and movement of genes to disparate regions of the genome. Accumulation of somatic mutations in long-lived coral colonies represents another mechanism by which coral genomes gain heterozygosity (Devlin-Durante et al. 2016; López and Palumbi 2020) and some of these mutations can be passed on to their sexually produced offspring (Vasquez Kuntz et al. 2022). Development of genomic resources allows for further study of these complex evolutionary mechanisms in metazoans as a whole (Reusch et al. 2021).

To help bridge the gap in genomic resources for Caribbean corals, we present novel PacBio HiFi-derived assemblies for C. natans, D. cylindrus, and S. siderea. With these references, we hope to foster an understanding of how corals will respond to environmental change (Bove et al. 2022) and population decline (Cramer et al. 2020) and how the response of Caribbean corals may differ from Indo-Pacific species.

Methods

Tissue sampling

Tissue of C. natans ([latitude 12.1095 decimal degrees, longitude −68.95497 decimal degrees], database ID 22254) was collected from the Water Factory reef in Curaçao on 2022 August 6 using a hammer and chisel. D. cylindrus ([12.0837, −68.89447], database ID 22255) and S. siderea ([12.0839, −68.8944], database ID 22256) were collected from the Sea Aquarium reef in Curaçao on 2022 August 12 and 13 using a hammer and chisel. All collections were made under Curaçao Governmental Permit 2012/48584. All fragments were ca. 12 cm2 in size and were kept alive in coolers filled with seawater during transit prior to being preserved in DNA/RNA Shield (Zymo Research, CA, USA). Samples were stored at −20°C or at −80°C until extraction.

Nucleic acid extraction and sequencing

For all species, DNA was extracted from tissue preserved in DNA/RNA Shield (Zymo Research) using the Qiagen (MD, USA) MagAttract HMW DNA kit, following manufacturer’s protocols. Following initial extraction, DNA was further purified using a 0.9X AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) bead cleanup. Purified DNA was then size selected using a Pacific Biosciences (formerly Circulomics) SRE size selection kit. The SRE standard kit selects for DNA predominantly >25 kb and a near total depletion of fragments <10 kb. Barcoded templates were generated and sequenced by the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences Genomics Core Facility at Penn State University using a Pacific Biosciences (Menlo Park, CA, USA) Sequel IIe across a total of 3 SMRTcells (further described below).

As RNAseq data were not available for D. cylindrus or any close relatives for the purposes of gene prediction, RNA was extracted from the same DNA/RNA Shield (Zymo Research) preserved samples as described above using a TriZol and a Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (as in https://openwetware.org/wiki/Haynes:TRIzol_RNeasy). Compared with the RNA sequence data obtained from NCBI SRA for C. natans and S. siderea (described below in “Gene prediction and functional annotation”), the RNA sample for D. cylindrus was of an untreated colony growing in the wild rather than experimental samples exposed to heat and disease stress. From the extracted total RNA, libraries were prepared and sequenced by the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation Clinical Genomics Center using the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England BioLabs Inc., MA, USA), Swift Rapid RNA Library Kit (Swift Biosciences, MI, USA), and 150 M read pairs of 2 × 150 bp chemistry on an Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) NovaSeq 6000 machine.

Genome assembly

A PacBio library was generated by pooling the barcoded templates for each of the 3 species in equal proportions and was initially sequenced on 2 SMRTcells. Prior to genome assembly, k-mer (31-mer) counting was performed on PacBio HiFi data for each species using Jellyfish v2.2.10 (Marçais and Kingsford 2011) for the purpose of haploid genome size estimation. K-mer frequency-based genome-wide heterozygosity and genome size were estimated from 31-mer histograms using GenomeScope2 (Ranallo-Benavidez et al. 2020). With the data from these 2 initial SMRTcells, a preliminary assembly was performed using hifiasm_meta v0.2 (Feng et al. 2022) to assess assembly size and to determine whether the pool balance needed to be adjusted for the third and final SMRTcell run.

Because the preliminary assembly and genome size estimate from GenomeScope2 of S. siderea was larger than the remaining 2 species, the final SMRTcell was run with a pool balance of 25:25:50 Colpophyllia/Dendrogyra/Siderastrea to provide additional coverage of the larger Siderastrea genome. Prior to all stages of data delivery, the sequencing facility used PacBio lima to demultiplex and remove adapters and unbarcoded sequences. Across all SMRTcells, total sequence yield was 26 Gb across 2.8 M reads in C. natans, 25 Gb across 2.7 M reads in D. cylindrus, and 32 Gb across 3.4 M reads in S. siderea. Further breakdown of PacBio yield and read lengths per species per sequencing run are given in Supplementary Table 1. Utilizing all data, a new set of primary assemblies was generated using hifiasm_meta.

Assembly decontamination, haplotig purging, and repeat annotation

HiFi reads were then mapped to the assembly using minimap2 v2.24 (Li 2018), and BAM files were sorted using samtools v0.1.19 (Danecek et al. 2021). Using blastn v2.14.0 (Camacho et al. 2009), assemblies were searched against a custom database comprised of NCBI's ref_euk_rep_genomes, ref_prok_rep_genomes, ref_viroids_rep_genomes, and ref_viruses_rep_genomes databases combined with dinoflagellate and Chlorella genomes (Shoguchi et al. 2013, 2018, 2021; Hamada et al. 2018; Beedessee et al. 2020). All NCBI RefSeq databases were downloaded on 2023 March 28. Using the mapping and blastn hits files, blobtools v1.1.1 (Laetsch and Blaxter 2017) was used to identify and isolate noncnidarian contigs. To better identify symbionts within the metagenome assemblies, blastn (Camacho et al. 2009) was used to query putative Symbiodiniaceae contigs against a curated nuclear ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacer-2 (ITS2) database (Hume et al. 2019). With all noncnidarian contigs excluded, a repeat database was modeled using RepeatModeler2 v2.0.2a (Flynn et al. 2020). Purge_dups v1.2.6 (Guan et al. 2020) was utilized to identify and remove any remaining putative haplotigs in the respective assemblies. Following haplotig purging, repeats were soft-masked using a filtered repeat library in RepeatMasker4 v4.1.2.p1 (Smitet al.), following recommendations from the Blaxter Lab (https://blaxter-lab-documentation.readthedocs.io/en/latest/filter-repeatmodeler-library.html). Protein references from Orbicella faveolata (Prada et al. 2016) and Fungia sp. (Ying et al. 2018) were used to filter repeat libraries for the 2 robust species (C. natans and D. cylindrus). Protein references from Acropora millepora (Fuller et al. 2020), Montipora capitata (Stephens et al. 2022), and Galaxea fascicularis (Ying et al. 2018) were used to filter repeat libraries for S. siderea.

Gene prediction and functional annotation

Prior to gene prediction, the hifiasm_meta assemblies were scanned for mitochondrial contamination using MitoFinder v1.4.1 (Allio et al. 2020) and contigs of mitochondrial origin were removed from the assemblies. Nuclear assemblies were annotated using RNAseq data in funannotate v1.8.13 (Palmer and Stajich 2020). C. natans and S. siderea were annotated using all RNAseq data available on NCBI SRA for the respective species at the time of assembly (see Supplementary Table 2). As no RNAseq data are publicly available for D. cylindrus or its close relatives, RNA was extracted as previously described and included within the funannotate annotation process. All RNAseq data were adapter- and quality-trimmed using TrimGalore v0.6.7 (Krueger et al. 2021).

Briefly, funannotate train was run for all assemblies with a –max_intronlen of 100,000. Funannotate train is a wrapper that utilizes Trinity (Grabherr et al. 2011) and PASA (Haas et al. 2008) for transcript assembly. Upon completion of training, funannotate predict was run to generate initial gene predictions using the arguments --repeats2evm, --organism other, and --max_intronlen 100000. Funannotate predict is a wrapper that runs AUGUSTUS (Stanke et al. 2006) and GeneMark (Brůna et al. 2020) for gene prediction and EvidenceModeler (Haas et al. 2008) to combine gene models. Funannotate update was run to update annotations to be in compliance with NCBI formatting. For problematic gene models, funannotate fix was run to drop problematic IDs from the annotations. Finally, functional annotation was performed using funannotate annotate which annotates proteins using PFAM (Bateman et al. 2004), InterPro (Hunter et al. 2009), EggNog (Huerta-Cepas et al. 2019), UniProtKB (Boutet et al. 2016), MEROPS (Rawlings et al. 2010), CAZyme (Huang et al. 2018), and Gene Ontology (GO) (Harris et al. 2004). For all genes not functionally annotated with GO terms by funannotate, a single network of ProteInfer (Sanderson et al. 2023) was used to infer functional attributes of genes using pretrained models.

To assess the quality of genome assemblies and annotations, BUSCO v5.8.0 (Manni et al. 2021) was run with the metazoa_odb10 lineage dataset. BUSCO was run in genome mode on the full genome assembly and in protein mode on the predicted proteins dataset output by funannotate.

Mitochondrial genome assembly

To assemble mitochondrial genomes for each sample, MitoHiFi v2.2 (Gabriel et al. 2023) was used on all available HiFi data for each species. For S. siderea, C. natans, and D. cylindrus, accessions NC_008167.1, NC_008162.1, and DQ643832.1 (whole mitogenomes for Siderastrea radians, C. natans, and Astrangia poculata) were used as seed sequences for mitochondrial assembly, respectively. For all assemblies, the arguments -a animal and -o 5 were used to indicate that the organism type was an animal and the organism genetic code was invertebrate.

Duplication and orthogroup analysis

To assess the origin of gene duplications, whole-genome duplication pipeline and orthogroup analyses were used. The wgd pipeline v1.1 (Zwaenepoel and Van De Peer 2019) was used to investigate duplication and divergence at the whole paranome and anchor-pair levels. The longest, coding CDS transcript of each gene was used as input for wgd. The wgd pipeline acts as a wrapper for a number of programs, and in the case of the analysis here, the following programs were run through wgd: blastp (Altschul et al. 1997), MCL (Markov Cluster Process, Hazewinkel and Van Eijck 2000), PAML (Yang 2007), MAFFT (Katoh and Standley 2013), FastTree (Price et al. 2010), and i-ADHoRe 3.0 (Proost et al. 2012). In addition to wgd, OrthoFinder v2.5.4 (Emms and Kelly 2019) was run to discover orthologous groups unique to each species and shared between species. For OrthoFinder analyses, the longest peptide isoform for each gene was used as input. A full list of taxa included in OrthoFinder and doubletrouble analyses (described below) is given in Supplementary Table 3.

CAFE5 v5.1.0 (Mendes et al. 2021) was used to discover hierarchical orthogroups from OrthoFinder undergoing phylogenetically significant gene family expansions or contractions. To begin, r8s v1.81 (Sanderson 2003) was used to time-calibrate the phylogeny from OrthoFinder using fossil priors obtained from the PaleoBioDB fossil record (Peters and McClennen 2016). Priors for Acropora palmata (3.6 MYA, Budd et al. 1999), Porites compressa (2.588 MYA, Faichney et al. 2011), Acropora (59 MYA, Vecsei and Moussavian 1997), Faviina (247 MYA, Qi 1984), and Scleractinia (268 MYA, Gregorio 1930) were used as calibration points. With significantly expanding or contracting hierarchical orthogroups identified by CAFE5, GO terms for genes in expanding and contracting gene families were extracted and compared with the whole-genome background in each species to test for enrichment. Enrichment analyses were performed using GOAtools (Klopfenstein et al. 2018) on genes in expanding gene families not annotated as transposons and transposases. Genes functionally annotated with the transposition GO term (GO:0032196) and its child terms were also excluded. GO term enrichment was also assessed for orthogroups unique to each species (unshared orthogroups). To reduce false discovery, only terms with a Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P-value <0.05, depth >2, and terms present in more than 5 study genes (all genes present in expanding orthogroups) were preserved. As GOAtools propagates child term counts up to parent terms, results can contain high redundancy and semantic similarity. To reduce some of the redundancy in significant GO terms, REVIGO v1.8.1 (Supek et al. 2011) was run using the SimRel semantic similarity measure to simplify enrichment results.

To classify stony coral (Scleractinia) paralogs into duplication types, doubletrouble v1.3.6 (Almeida-Silva and Van de Peer 2025) was run using the longest peptide isoform for each gene and default arguments. Briefly, doubletrouble classifies genes into segmental (SD), tandem (TD), proximal (PD), transposon-derived (TRD), and dispersed duplications (DD) based on collinearity, intron content, and phylogenetic position of paralogs. For instance, duplications are classified as tandem if 2 paralogs are separated by fewer than 10 genes. If the distance between genes is >10, paralogs are classified as PD. DD are considered any duplication that is not otherwise classifiable into more specific categories. For all doubletrouble analyses, Amplexidiscus fenestrafer (Wang et al. 2017), a member of the naked corals, Corallimorpharia, was used as an outgroup. Not all gene annotations were compatible with the “full” scheme, where TRD duplications are further classified into retrotransposon-derived and DNA transposon-derived. As such, the “full” scheme was only utilized for the focal study species here, C. natans, D. cylindrus, and S. siderea. All other species were run using the “extended” scheme.

Results and discussion

Assembly contiguity, completeness, and heterozygosity

All assemblies exhibit high contiguity (Table 1) and are gap-free. The S. siderea genome is roughly 2 times larger than observed in other corals species, with an assembly size of 822 M, compared with 526 and 399 Mb for D. cylindrus and C. natans, respectively. The assembly size of S. siderea is larger than most publicly available coral genome assemblies—only 2 species have larger assemblies, Pachyseris speciosa (Bongaerts et al. 2021) and Platygyra sinensis (Pootakham et al. 2021). However, the P. sinensis assembly likely contains considerable haplotig duplication, leaving only P. speciosa as a comparable assembly. In addition to being the largest of the 3 assemblies presented here, the S. siderea assembly is the most contiguous assembly (N50 = 9.1 Mb), likely due to the larger read N50 of SMRTcell 3 (see Supplementary Table 1). The genomes of C. natans and D. cylindrus have N50s of 4.647 and 4.902 Mb, respectively. Further scaffolding with Hi-C data could help elevate these 3 references to chromosome level. Genome-wide GC content is similar across all 3 species, with 39.81% for S. siderea, 38.87% for C. natans, and 39.29% for D. cylindrus. GC estimates are similar to other published stony coral genomes (e.g. Bongaerts et al. 2021).

Table 1.

Assembly summary statistics for Colpophyllia natans, Dendrogyra cylindrus, and Siderastrea siderea.

| Siderastrea siderea | Dendrogyra cylindrus | Colpophyllia natans | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contig total (Mb) | 822.514 | 526.444 | 398.943 |

| Gap percentage | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Number of contigs | 265 | 301 | 174 |

| Contig N50 | 9.1 Mb | 4.647 Mb | 4.902 Mb |

| Largest contig | 25.215 Mb | 21.044 Mb | 14.745 Mb |

| GC content (%) | 39.81 | 39.29 | 38.87 |

| % of k-mer estimate recovered | 105.61 | 105.99 | 103.47 |

| BUSCO Metazoa, complete (%)—genome mode | 96.6 | 96.5 | 97.2 |

| Single copy (genome) | 93.9 | 95.3 | 96.1 |

| Duplicated (genome) | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Fragmented (%) (genome) | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Missing (%) (genome) | 2.4 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| BUSCO Metazoa, complete (%)—protein mode | 91.8 | 94.9 | 95.5 |

| Single copy (protein) | 87.1 | 88.2 | 88.8 |

| Duplicated (protein) | 4.7 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

| Fragmented (%) (protein) | 3.2 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Missing (%) (protein) | 4.9 | 3.4 | 2.5 |

| Gene models | 61,712 | 39,739 | 34,139 |

| Protein-coding gene models | 52,473 | 34,738 | 29,090 |

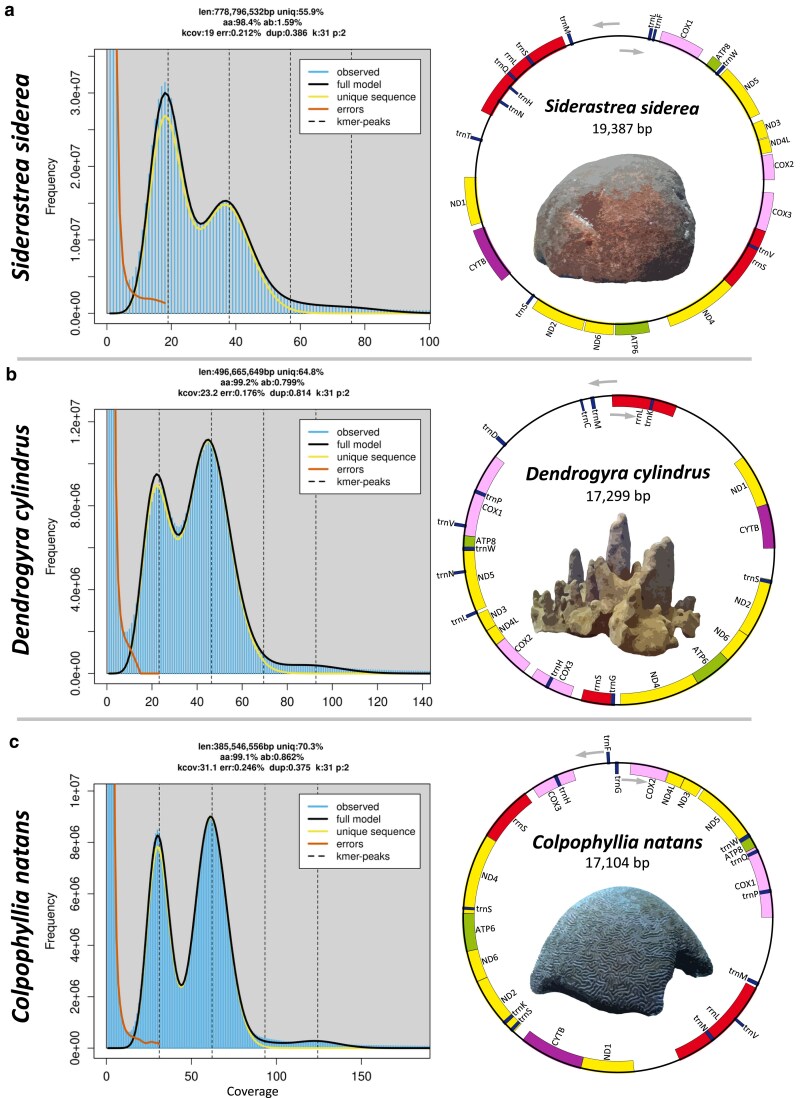

K-mer duplicity plots from GenomeScope2 (Fig. 1) suggest that all species here are diploid in nature, unlike the recent findings in Hawaiian corals (Stephens et al. 2022). All 3 assemblies exhibited high completeness as determined by BUSCO Metazoa in genome mode (Manni et al. 2021), with C. natans, D. cylindrus, and S. siderea showing 97.2, 96.5, and 96.6% completeness, respectively (Table 1). In terms of core BUSCO genes, S. siderea has the highest number of duplicated genes, with 2.7% of metazoan genes being duplicated. In genome mode, BUSCO showed that all 3 assemblies had similar percentages of fragmented and missing BUSCO genes. Evaluation of all protein isoforms using BUSCO in protein mode suggested that the complexity of the S. siderea genome may have slightly reduced the efficacy of genome annotation compared with the remaining 2 species, with completeness scores of 95.5, 94.9, and 91.8% for C. natans, D. cylindrus, and S. siderea, respectively. All assemblies are similar to their GenomeScope2 k-mer-based size estimates (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Taken together, these results suggest that the majority of all 3 genomes were successfully captured and annotated in our assemblies with little remaining haplotig duplication.

Fig. 1.

K-mer multiplicity plots (left panels) from GenomeScope2 (Ranallo-Benavidez et al. 2020) for a k-mer size of 31 for a) Siderastrea siderea, b) Dendrogyra cylindrus, and c) Colpophyllia natans. Mitochondrial genome gene order (right panels) in S. siderea, D. cylindrus, and C. natans. Mitogenomes assembled using MitoHiFi (Gabriel et al. 2023).

Genome-wide heterozygosity in corals typically ranges from 1.07 to 1.96% (Shinzato et al. 2021; Stephens et al. 2022; Yu et al. 2022; Young et al. 2024). K-mer frequency-based estimates of genome-wide heterozygosity from GenomeScope2 suggest that D. cylindrus has the lowest heterozygosity of the 3 species discussed here (0.799%) and among the lowest in any coral species for which genomic resources are available (Shinzato et al. 2021; Stephens et al. 2022; Yu et al. 2022; Young et al. 2024). The species has been rare throughout history (Hunter and Jones 1996; Modys et al. 2023) but with high local abundances in some locations (e.g. St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands). Recent catastrophic declines due to stony coral tissue loss disease (Neely et al. 2021; Alvarez-Filip et al. 2022) have led to the listing of the species as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, Cavada-Blanco et al. 2022). D. cylindrus is extinct in the wild in Florida (Neely et al. 2021), and all genets are now in captivity. Captive-based spawning efforts are burgeoning (Craggs et al. 2017; O’Neil et al. 2021) to recover the species. The very low heterozygosity estimate provided here highlights the need for carefully managed breeding (Marhaver et al. 2015) to ensure the persistence of the remaining standing genetic variation and adaptive potential of D. cylindrus (Barrett and Schluter 2008; Kardos et al. 2021). Of the 3 species, S. siderea has the highest genome-wide heterozygosity estimate of 1.59% and C. natans is intermediate with 0.862%. C. natans also has low genome-wide heterozygosity compared with other coral species and may require genetic management in the future. However, these genome-wide heterozygosity estimates are generated from singular genets and may not accurately represent the heterozygosity of the wider populations of each species. C. natans is the only species discussed here that does not have range-wide population genetic information available. As such, further genetic characterization of the species is clearly warranted due to population declines caused by infectious diseases (Alvarez-Filip et al. 2022) and the heterozygosity estimates provided here.

Repetitive content and transposable elements

The proportion of repeats assigned to each repeat category of RepeatMasker was similar across all 3 species assembled here (Table 2). Repetitive content was 47.80, 40.40, and 23.62% in S. siderea, D. cylindrus, and C. natans, respectively. The majority of repeats were interspersed, with unclassified repeats being most abundant in all 3 species (31.91, 25.57, and 12.22%). Compared with other cnidarians, these assemblies contain similar levels of repetitive content to jellyfish species such as members of Clytia, Aurelia, and Chrysaora containing 39–49.5% (Gold et al. 2019; Leclère et al. 2019; Xia et al. 2020) and to other scleractinian corals containing 13.6–58.1% (e.g. Shinzato et al. 2011; Cooke et al. 2020; Bongaerts et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2022; Stephens et al. 2022; Locatelli et al. 2024; Young et al. 2024). In our set of 3 species, we observe a general relationship of increasing repetitive content with increasing with genome size, corroborating that repeat expansion may be important in driving genome size disparities across evolutionary time in stony corals, as similarly observed in zoantharian and Hydra genomes (Wong et al. 2019; Fourreau et al. 2023).

Table 2.

Repetitive content and transposable elements identified by RepeatMasker (Smitet al.) across Siderastrea siderea, Dendrogyra cylindrus, and Colpophyllia natans.

| Siderastrea siderea | Dendrogyra cylindrus | Colpophyllia natans | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | Total | 138,779 | 68,819,835 | 8.39% | 82,872 | 47,945,358 | 9.09% | 68,722 | 17,971,690 | 4.52% |

| Maverick | 22,353 | 42,786,635 | 5.20% | 13,811 | 35,496,289 | 6.74% | 5,091 | 5,626,678 | 1.41% | |

| Sola-3 | 17,315 | 6,171,939 | 0.75% | 4,051 | 1,802,393 | 0.34% | 3,249 | 1,019,211 | 0.26% | |

| PIF-Harbinger | 9,247 | 1,246,387 | 0.15% | 9,092 | 1,764,101 | 0.34% | 5,361 | 821,524 | 0.21% | |

| Academ-1 | 4,662 | 1,873,178 | 0.23% | 2,578 | 872,091 | 0.17% | 1,886 | 777,963 | 0.20% | |

| LINE | Total | 104,185 | 32,929,736 | 4.02% | 53,305 | 17,696,634 | 3.36% | 46,166 | 15,626,622 | 3.92% |

| Penelope | 38,138 | 11,157,756 | 1.36% | 16,584 | 5,217,438 | 0.99% | 21,897 | 5,971,804 | 1.50% | |

| L1-Tx1 | 13,255 | 8,443,143 | 1.03% | 9,745 | 5,273,753 | 1.00% | 6,122 | 3,626,933 | 0.91% | |

| L2 | 29,218 | 6,994,614 | 0.85% | 16,810 | 3,452,973 | 0.66% | 11,440 | 3,468,236 | 0.87% | |

| RTE-BovB | 4,796 | 946,003 | 0.12% | 2,582 | 1,414,380 | 0.27% | 2,717 | 1,144,012 | 0.29% | |

| LTR | Total | 36,888 | 17,315,718 | 2.09% | 11,593 | 7,626,581 | 1.44% | 10,698 | 7,645,820 | 1.92% |

| Gypsy | 14,784 | 5,919,375 | 0.72% | 4,918 | 2,999,690 | 0.57% | 5,407 | 4,098,188 | 1.03% | |

| Pao | 4,227 | 4,683,913 | 0.57% | 3,053 | 2,945,104 | 0.56% | 1,809 | 1,501,851 | 0.38% | |

| DIRS | 3,419 | 2,371,017 | 0.29% | 1,323 | 882,015 | 0.17% | 2,095 | 1,383,508 | 0.35% | |

| Ngaro | 7,195 | 3,053,083 | 0.37% | 869 | 469,818 | 0.09% | 1,057 | 496,392 | 0.12% | |

| SINE | Total | 16,023 | 2,146,747 | 0.26% | 4,485 | 541,212 | 0.10% | 5,616 | 674,504 | 0.17% |

| tRNA-V | 3,912 | 567,988 | 0.07% | 2,623 | 350,202 | 0.07% | 3,166 | 512,682 | 0.13% | |

| MIR | 8,147 | 1,173,564 | 0.14% | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | |

| tRNA-RTE | 1,612 | 150,650 | 0.02% | 1,010 | 100,831 | 0.02% | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Alu | 1,485 | 131,235 | 0.02% | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Low complexity | 455 | 76,303 | 0.01% | 282 | 53,301 | 0.01% | 123 | 26,366 | 0.01% | |

| Retroposon | L1-dep | 175 | 32,571 | 0.00% | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0 | 0.00% |

| Rolling circle | Helitron | 2,701 | 1,113,967 | 0.14% | 837 | 186,063 | 0.04% | 5,529 | 2,007,025 | 0.50% |

| Satellites | 476 | 226,250 | 0.03% | 1,120 | 113,510 | 0.02% | 1,795 | 189,861 | 0.05% | |

| Simple repeats | 17,276 | 2,670,182 | 0.32% | 11,761 | 1,849,810 | 0.35% | 6,765 | 1,167,479 | 0.29% | |

| RNA repeats | Total | 24,191 | 5,349,132 | 0.65% | 21,009 | 2,054,088 | 0.39% | 727 | 135,302 | 0.03% |

| tRNA | 23,498 | 5,198,251 | 0.63% | 20,541 | 1,915,611 | 0.36% | 395 | 44,379 | 0.01% | |

| rRNA | 693 | 150,881 | 0.02% | 468 | 138,477 | 0.03% | 260 | 82,379 | 0.02% | |

| snRNA | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 72 | 8,544 | 0.00% | |

| Unclassified | 1,000,623 | 262,395,404 | 31.91% | 635,176 | 134,635,802 | 25.57% | 262,664 | 48,767,859 | 12.22% | |

| Total | 1,341,772 | 393,075,845 | 47.80% | 822,440 | 212,702,359 | 40.40% | 408,805 | 94,212,528 | 23.62% | |

The top 3 repeat families (e.g. Maverick) within each major repeat class (DNA, LINE, LTR, SINE, and RNA repeats) are presented in this table.

In C. natans, the DNA transposon class of repeats was reduced by ∼50% when compared with S. siderea and D. cylindrus (Table 2). Within the DNA transposons, the Maverick subclass represented the most prominent deficits in C. natans, representing only 1.41% of the genome compared with 5.20 and 6.74% in S. siderea and D. cylindrus, respectively. It is unclear whether DNA transposons have contracted in C. natans or expanded in S. siderea and D. cylindrus, although both purging and expansions of repetitive content have been implicated in genome size evolution in cnidarians and other organisms (Hawkins et al. 2006; Michael 2014; Roessler et al. 2019; Kon et al. 2024). Further work is required to understand the genomic processes by which repetitive DNA expands and contracts in cnidarian genomes, as well as the overall importance of repetitive content in speciation processes and establishing new lineages. However, the genome assemblies presented here echo the standing literature and suggest that losses or gains of certain repetitive classes exist across the diversity of extant stony corals.

Gene prediction and unique orthogroups

S. siderea is unique among the assembled genomes not just for its size and contiguity, but also its gene content. Gene prediction in funannotate identified 61,712 gene models, roughly double the number of genes discovered for D. cylindrus and C. natans (39,739 and 34,139, respectively; Table 1), and compared with other publicly available coral genome assemblies (e.g. Prada et al. 2016; Fuller et al. 2020). Of these gene models, 52,473, 34,738, and 29,090 were predicted to be protein-coding for S. siderea, D. cylindrus, and C. natans, respectively. D. cylindrus and C. natans fall within the expectations for stony corals in terms of protein-coding gene content. The gene content of S. siderea is higher than expected, only comparable to M. capitata among published genomes (Stephens et al. 2022). Of the protein-coding gene models, 1,515, 297, and 287 models in S. siderea, D. cylindrus, and C. natans contained ≥90% repeat-masked bases, suggesting that these models may be derived from repetitive DNA and transposition-related events. A further 79, 47, and 31 gene models in S. siderea, D. cylindrus, and C. natans were either directly annotated as transposons or transposases or were associated with transposition (GO:0032196) or transposase activity (GO:0004803) related GO terms.

Because of the doubling in overall size and gene content present in the S. siderea, Ks tests were performed to test for an ancient whole-genome duplication in the evolution of the species. Ks distributions in species having experienced whole-genome duplication events exhibit characteristic distributions with a hump (as in Zwaenepoel and Van De Peer 2019), where many gene pairs are derived from a simultaneous duplication event and have all experienced a similar number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site. Whole-genome duplication analyses in wgd did not find Ks ratios indicative of ancient whole-genome duplication in any of the species assembled here (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting that other processes may be responsible for gain in genome size. BUSCO completeness, as described above, also suggested that duplication of metazoan single copy genes in the S. siderea genome is minimal, further reducing support for a whole-genome duplication event.

OrthoFinder analyses placed 47,786 protein-coding genes into 21,970 orthogroups in S. siderea. Of these, 1,004 orthogroups containing 3,849 protein-coding genes were exclusively found in S. siderea (Fig. 2). An additional 4,687 protein-coding genes could not be binned into orthogroups by OrthoFinder. As OrthoFinder utilizes DIAMOND (Buchfink et al. 2015) with the --more-sensitive alignment option, orthogroups are only formed if inter- and intraspecies alignments are ≥40% in identity. The presence of thousands of unbinned genes and orthogroups unique to S. siderea suggests that gene duplication and subsequent diversification are prominent in the lineage. Among multicopy gene families unique to S. siderea (Supplementary Fig. 2), the most enriched GO term compared with the genomic background was “bioluminescence” (GO:0008218). Fluorescent pigment proteins have been shown to undergo rapid evolution and strong selection in corals (Voolstra et al. 2011). These proteins are photoprotective for the coral holobiont (Salih et al. 2000) and can serve to optimize the light environment of symbiotic Symbiodiniaceae (Bollati et al. 2022). Indeed, presence of pink fluorescent pigment in congener Siderastrea stellata is associated with higher temperatures (Tunala et al. 2023). S. siderea harbors 3 distinct genetic lineages (Aichelman et al. 2025) of which only one was sequenced here. Additional genome assemblies of the other 2 lineages may shed light on the taxonomic status of these lineages and what role gene duplication and diversification may have played in their evolution.

Fig. 2.

Upset plot describing unique and shared orthogroups across scleractinian corals and an outgroup, Corallimorpharia. Gene models were assigned to orthogroups using OrthoFinder (Emms and Kelly 2019). All included taxa are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The focal taxa assembled in the present study are indicated by bold font and asterisks (*).

D. cylindrus had comparatively fewer protein-coding genes placed into a similar number of orthogroups—32,896 genes in 19,251 orthogroups. Of these, 233 orthogroups were unique to the species, containing a total of 1,061 genes. 1,842 genes remained unbinned. Of the orthogroups unique to D. cylindrus, the most enriched GO term was “response to defense of other organism” (GO:0098542, Supplementary Fig. 2). The lack of specificity of the term makes it unclear whether this refers to external organisms (e.g. damage from predation or disease) or internal organisms (e.g. intracellular Symbiodiniaceae symbionts). However, a child term of GO:0098542, “defense response to bacterium” (GO:0042742), is found among the genes in gene families unique to D. cylindrus, suggesting that immune response to infection is particularly important to the species. Other enriched GO terms such as “apoptotic process” and “regulation of response to external stimulus” further support that response to bacterial infection may be particularly important to the species. Given its lineage age, D. cylindrus has been suggested to be intrinsically better at fighting infections compared with younger lineages (Pinzón et al. 2014). Recent catastrophic losses of the species due to stony coral tissue loss disease may have broken this long-standing advantage (Alvarez-Filip et al. 2022), although some evidence suggests that the disease may be the result of an infection of the symbiont that cascades to affect the host (Klein et al. 2024), rather than directly infecting the host.

C. natans had the fewest orthogroups, with 27,892 protein-coding genes placed into 18,430 orthogroups. 545 genes were placed into 164 orthogroups that were unique to the species and 1,198 genes remained unbinned. There was an enrichment for terms relating to transfer RNA (tRNA) modification (GO:0002949 and GO:0070525) in the gene families only found in C. natans (Supplementary Fig. 2). “Bioluminescence” also appears among the most enriched GO terms in orthogroups unique to the species, similar to S. siderea. Additionally, several terms relating to growth and development (“blastocyst growth” and “anatomical structure maturation”) were found to be enriched among orthogroups unique to C. natans. C. natans is among the most quickly developing broadcast spawners in the Caribbean, with settlement and the onset of zooplanktivory occurring in as little as 3–4 days (Geertsma et al. 2022; Yus et al. 2024), possibly due to the enrichment of growth-related terms observed here. The “regulation of pH” is also enriched, perhaps allowing the species to survive in environments less conducive to survival in other species. For instance, C. natans is one of the few coral species able to thrive in unusual habitats such as mangrove canopy environments with comparatively low pH, as well as reef flats and reef slope environments more typically associated with Caribbean reef communities (Stewart et al. 2022).

Mitochondrial genomes

Mitochondrial genomes were successfully assembled for all 3 species discussed here using MitoHiFi (Gabriel et al. 2023). Both D. cylindrus and C. natans were of similar size with lengths of 17,299 and 17,104 bp, respectively. S. siderea is considerably larger, with a total length of 19,387 bp (Fig. 1). The S. siderea mitogenome is among the largest of all stony coral (Scleractinia). Of all sequenced scleractinians, the mitogenome of S. siderea is exceeded in length only by the solitary coral species Polymyces wellsi (Flabellidae, NC_082103.1, 19,924 bp), Deltocyathus magnificus (Deltocyathidae, OR625187.1, 19,736 bp), and Rhombopsammia niphada (Micrabaciidae, MT706034.1, 19,654 bp), and colony-forming species Pseudosiderastrea formosa and Pseudosiderastrea tayami (Siderastreidae, NC_026530.1 and NC_026531.1, 19,475 bp). In terms of gene structure, all 3 mitochondrial genome assemblies consist of 13 protein-coding genes and 2 ribosomal RNA (rRNA, rrnL and rrnS) genes with highly conserved gene order (ND5, ATP8, COX1, rrnL, ND1, CYTB, ND2, ND6, ATP6, ND4, rrnS, COX3, COX2, ND4L, and ND3). Both D. cylindrus and C. natans contain 12 tRNA genes, while S. siderea contains 11.

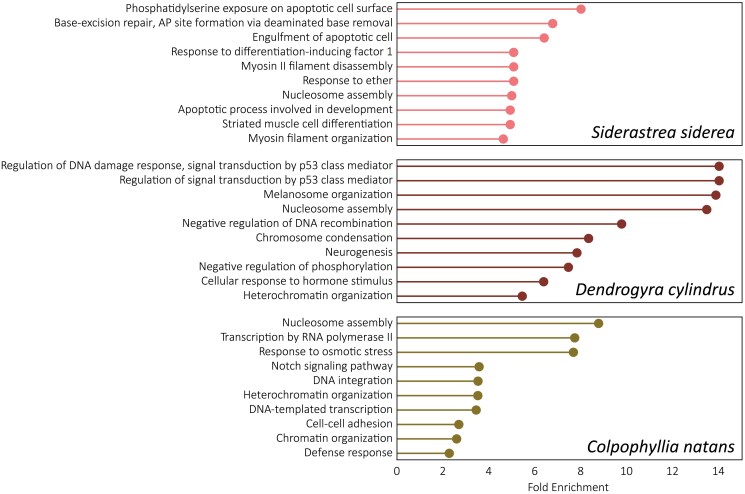

Expansion of shared gene families and modes of duplication

GO enrichment analyses of shared gene families undergoing phylogenetically significant expansion (as identified by OrthoFinder and CAFE5) may point to the importance of specific functional attributes in the evolution of each of the taxa assembled here (Fig. 3). In all 3 species, there was an enrichment among significantly expanding gene families for GO terms relating to nucleosome assembly, chromosome condensation, and chromatin/heterochromatin organization when compared with the genomic background of each species. This suggests that these functional attributes were disproportionately important in the evolution of stony corals. Chromatin accessibility is important for fine-tuning transcriptional response (GO:0006351 and GO:0006366, enriched in C. natans), as well as DNA repair (GO:0097510, enriched in S. siderea) and recombination (GO:0045910 and GO:0015074, enriched in D. cylindrus and C. natans, respectively) (Tsompana and Buck 2014). Experiments in the model sea anemones, Nematostella and Aiptasia, further corroborate this hypothesis, demonstrating that chromatin accessibility is dynamic over the course of stressful events such as heat exposure and resulted in expressional changes in pathways related to immune response, oxidative stress, metabolism, and DNA repair (Weizman and Levy 2019; Weizman et al. 2021).

Fig. 3.

Top 10 GO terms enriched in orthogroups undergoing phylogenetically significant expansion in Siderastrea siderea, Dendrogyra cylindrus, and Colpophyllia natans. Orthogroups were assigned using OrthoFinder (Emms and Kelly 2019). Gene families undergoing phylogenetically significant expansion were identified using CAFE5 (Mendes et al. 2021). GO enrichment analyses were performed in GOATools (Klopfenstein et al. 2018).

In S. siderea, “phosphatidylserine exposure on apoptotic cell surface” (GO:0070782) is the most enriched GO term in gene families that are significantly expanding compared with the genomic background of the species (Fig. 3). Additionally, the terms “engulfment of apoptotic cell” (GO:0043652) and “apoptotic process involved in development” (GO:1902742) were also enriched in S. siderea. Stress response in corals involves the activation of apoptotic pathways, particularly in the case of heat stress response (Kvitt et al. 2011; Tchernov et al. 2011; Helgoe et al. 2024), and S. siderea is among the most heat-tolerant corals inhabiting Caribbean reefs (Palacio-Castro et al. 2021). The expansion of apoptosis-regulating gene families may be, in part, responsible for the overall resilience of S. siderea to adverse environmental conditions. In addition to apoptotic pathways and chromatin structure, there was also an enrichment of multiple myosin- and muscle-related ontology terms (GO:0031035, GO:0031033, GO:0051146). Myosin proteins have been identified as differentially expressed or differentially concentrated across inshore-offshore gradients, in heat stress conditions, and in diseased tissue across divergent coral taxa and may also play a role in S. siderea's resilience (DeSalvo et al. 2010; Ricaurte et al. 2016; Wong et al. 2021; Mayfield 2022).

The 2 GO terms with the highest fold enrichment in D. cylindrus both involve pathways of the p53 class mediator (GO:1901796 and GO:0043516), one of which involves the regulation of DNA damage response. Sessile, shallow-living marine organisms are exposed to high levels of UV radiation, and corals have fast and effective DNA repair mechanisms at all life stages (Reef et al. 2009; Svanfeldt et al. 2014). Melanosome organization (GO:0032438) was also found highly enriched in D. cylindrus. Melanin production is important in cnidarian innate immunity (Palmer et al. 2012; Changsut et al. 2022; Van Buren et al. 2024) and may serve to protect shallow-living corals from UV exposure (Wall et al. 2018), and also protect their symbionts (Harman et al. 2022). D. cylindrus is a long-lived species, and even colonies in early development with no vertical pillar formation may be older than 30 years (Neely et al. 2021). This longevity may explain the enrichment in processes that reduce UV exposure and repair DNA damage that accumulates during the life of a genet.

Compared with other species in the analysis, gene families most expanded in C. natans were enriched in functions related to environmental response (“response to osmotic stress,” GO:0006970) as well as cell signaling (“Notch signaling pathway,” GO:0007219 and “cell–cell adhesion,” GO:0098609) and immune response (“defense response,” GO:0006952). As described above, C. natans is able to persist in habitats such as mangrove stilt roots. These environments are often low in pH and low in salinity, and expansions of gene families relating to osmotic stress response may enable the species to thrive in these challenging habitats. The remainder of the expanded gene families in C. natans were involved in chromatin accessibility and nucleosome assembly (Fig. 3) as in S. siderea and D. cylindrus.

Subsequent analysis of paralogs using doubletrouble found that proximal duplications (PD—locally duplicated with paralogs separated by 10 or more genes) were the most prominent form of classifiable gene duplications in S. siderea (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4). Previous studies have suggested that tandem duplications (TD) drive Scleractinian (stony coral) evolution (Noel et al. 2023). Indeed, TD appeared to be more abundant in S. siderea in comparison with many of the evaluated taxa (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4). However, duplicate classification is inherently challenging as the order of genes can be the result of many different potential processes. For instance, TD can be broken apart by dispersed duplications (DD) being copied between tandem paralogs. These would resemble PD according to doubletrouble's classification schema, despite being the result of 2 separate duplication processes. Additionally, analyses comparing species are somewhat reliant on similarly high-quality annotation and assembly across analyzed taxa. Several of the assemblies evaluated in our duplication analyses are of low contiguity and filled with short-read derived gaps, which could reduce the ability to detect certain forms of duplication. For example, O. faveolata (Prada et al. 2016) contains no segmental duplications (SD, Supplementary Table 4), potentially because the detection of collinear, duplicated blocks of genes is less likely when the genome is highly fragmented. Further, it may not be possible to assign duplicates as transposon-derived duplications (TRD) with assemblies derived from Nanopore or PacBio CLR data (e.g. Acropora cervicornis, Locatelli et al. 2024). Even polished long-read assemblies may contain enough error in repetitive proteins such that a single copy of the gene cannot be assigned as ancestral—a requirement for paralogs to be classified as TRDs.

Despite the expansion of duplicated genes in Scleractinian species with larger genome sizes (e.g. S. siderea and M. capitata, Supplementary Fig. 3), tandemly duplicated genes do not appear to have a disproportionate impact on genome size or gene content as suggested previously (Noel et al. 2023). When all duplicates are scaled to a value of 1 (Supplementary Fig. 4), no singular duplication category appears to be most important in governing coral genome size. Instead, the proportion of paralogs assigned to each duplication type is similar across all species (an average of 22.0% tandem, 14.5% proximal, 2.3% segmental, 19.0% transposon-related, and 42.2% dispersed, Supplementary Table 4). This suggests that all duplication types are expanding in synchrony to result in the genome size disparities we see across the phylogeny of Scleractinia. Further expansion of duplication analyses to include assemblies from upcoming efforts of large database projects (e.g. Reef Genomics, Liew et al. 2016; Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics Project, McKenna et al. 2021) could help elucidate more fine-scale, lineage-specific duplication processes that we have been unable to capture here.

Symbiont contigs

As metagenome assemblers were utilized in the assembly of the host species, symbiont data were also co-assembled and were of sufficient coverage to identify the prominent symbiont present to at least the genus-level. Both C. natans and D. cylindrus contained Breviolum, with D. cylindrus most likely containing Breviolum dendrogyrum, as described in Lewis et al. (2019). However, the top ITS2 hits (determined by e-value, followed by percent identity) for both species do not closely match formally named strains/species in the curated ITS2 database (C. natans top symbiont hit B4, 89.89%, e-value 3.33e−24; D. cylindrus top hit B1, 97.98%, e-value 2.21e−42). It is possible that the symbionts contained in the genome assembly samples of C. natans and D. cylindrus are not yet represented in this database.

In the initial separation of host and symbiont contigs using BlobTools, the S. siderea genet assembled here was found to be associated with Cladocopium, but comparison of contigs with the ITS2 database did not reveal any more specific hits. The psbA region is a more reliable marker for symbiont strain identification than ITS2 (LaJeunesse and Thornhill 2011). However, symbiont reference sequences for psbA are not currently as extensive as ITS2 in strain coverage. As the ITS2 and psbA databases continue to grow, symbiont contigs assembled here could be identified with greater taxonomic resolution.

In addition to eukaryotic algal symbionts, one notable prokaryotic symbiont was recovered. Within the assembly for C. natans, a 2.13-Mb contig was identified as most closely related to Prosthecochloris aestuarii. This bacterium has been proposed as a putatively symbiotic microbe living within coral skeletons (Cai et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2021). Coral metagenomes contain a wealth of symbionts with important functions for the holobiont (Bourne et al. 2009; Thompson et al. 2015; Boilard et al. 2020; Garrido et al. 2021). Further exploration of coral associated microbial communities may identify novel associations that are critical for the survival of the coral host.

Conclusion

Here, we generated novel genome assemblies for key Caribbean reef-building corals, all of which are listed as vulnerable or critically endangered by the IUCN. All genome assemblies are highly complete (>95% BUSCO Metazoa) and contiguous (N50 > 4.6 Mb). The genomes of D. cylindrus and C. natans fall within nominal expectations of size and gene content based on other published coral genomes. S. siderea is roughly 2 times larger than expected with twice the number of predicted gene models, despite no evidence for a whole-genome duplication event. Repeat and gene family expansions seem to be drivers of the larger S. siderea genome size. These results align with and expand upon previously published literature which implicated gene duplications as a driving factor of stony coral evolution (Noel et al. 2023). Given the importance of duplications in speciation across corals, further work should explore intraspecific structural polymorphisms (such as copy number variants) to understand how structural variation plays a role in structure and adaptation at the population level.

These assemblies will help aid the broader research community by enabling high-resolution genomic analyses that explore trait variation within species and potentially provide restoration practitioners with useful information to implement in restoration initiatives. As coral populations continue their decline, it is crucial that we develop a thorough understanding of the genomic processes that have driven coral evolution and have allowed them to overcome past extinction events and global stressors. These reference assemblies provide a key stepping stone toward this goal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kelly Gomez-Campo and C. Cornelia Osborne for field assistance in collection of genome samples. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Huck Institutes' Genomics Core Facility (RRID:SCR_023645) for use of the PacBio Sequel IIe sequencing platform.

Contributor Information

Nicolas S Locatelli, Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

Iliana B Baums, Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA; Helmholtz Institute for Functional Marine Biodiversity at the University of Oldenburg (HIFMB), Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, Im Technologie Park 5, Oldenburg 26129, Germany; Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz-Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), Am Handelshafen 12, Bremerhaven 27570, Germany; Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment (ICBM), School of Mathematics and Science, Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, Ammerländer Heerstraße 114-118, Oldenburg 26129, Germany.

Data availability

Raw sequencing data and assemblies generated for this project are available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession PRJNA982825. These Whole Genome Shotgun projects (assemblies) have been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accessions GCA_043250745.1, GCA_043250805.1, and GCA_043250775.1 for Dendrogyra cylindrus, Colpophyllia natans, and Siderastrea siderea, respectively. All annotations and associated assembly and analysis scripts and files are publicly available on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.13323697.

Supplemental material available at G3 online.

Funding

This research was funded by the Revive and Restore Advanced Coral Toolkit Program funding to IBB. N.S.L. was supported by the NIH T32 Kirschstein-NRSA: Computation, Bioinformatics, and Statistics (CBIOS) training program at The Pennsylvania State University (#T32GM102057). The findings and conclusions do not necessarily reflect the view of the funding agencies.

Literature cited

- Aichelman HE, Benson BE, Gomez-Campo K, Martinez-Rugerio MI, Fifer JE, Tsang L, Hughes AM, Bove CB, Nieves OC, Pereslete AM, et al. 2025. Cryptic coral diversity is associated with symbioses, physiology, and response to thermal challenge. Sci Adv. 11(3):eadr5237. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adr5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allio R, Schomaker-Bastos A, Romiguier J, Prosdocimi F, Nabholz B, Delsuc F. 2020. MitoFinder: efficient automated large-scale extraction of mitogenomic data in target enrichment phylogenomics. Mol Ecol Resour. 20(4):892–905. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Silva F, Van de Peer Y. 2025. Doubletrouble: an R/Bioconductor package for the identification, classification, and analysis of gene and genome duplications. Bioinformatics. btaf043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaf043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1086/284325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Filip L, González-Barrios FJ, Pérez-Cervantes E, Molina-Hernández A, Estrada-Saldívar N. 2022. Stony coral tissue loss disease decimated Caribbean coral populations and reshaped reef functionality. Commun Biol. 5(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03398-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett RDH, Schluter D. 2008. Adaptation from standing genetic variation. Trends Ecol Evol. 23(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, Sonnhammer ELL, et al. 2004. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32(90001):D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baums IB, Chamberland VF, Locatelli NS, Conn T. 2022. Maximizing genetic diversity in coral restoration projects. In: van Oppen MJH, Lastra MA, editors. Coral Reef Conservation and Restoration in the Omics Age. Vol. 15. Cham: Springer. (Coral Reefs of the World). p. 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Beedessee G, Kubota T, Arimoto A, Nishitsuji K, Waller RF, Hisata K, Yamasaki S, Satoh N, Kobayashi J, Shoguchi E. 2020. Integrated omics unveil the secondary metabolic landscape of a basal dinoflagellate. BMC Biol. 18(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12915-020-00873-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boilard A, Dubé CE, Gruet C, Mercière A, Hernandez-Agreda A, Derome N. 2020. Defining coral bleaching as a microbial dysbiosis within the coral holobiont. Microorganisms. 8(11):1682. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8111682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollati E, Lyndby NH, D’Angelo C, Kühl M, Wiedenmann J, Wangpraseurt D. 2022. Green fluorescent protein-like pigments optimise the internal light environment in symbiotic reef-building corals. eLife. 11:e73521. doi: 10.7554/eLife.73521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaerts P, Cooke IR, Ying H, Wels D, den Haan S, Hernandez-Agreda A, Brunner CA, Dove S, Englebert N, Eyal G, et al. 2021. Morphological stasis masks ecologically divergent coral species on tropical reefs. Curr Biol. 31(11):2286–2298.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne DG, Garren M, Work TM, Rosenberg E, Smith GW, Harvell CD. 2009. Microbial disease and the coral holobiont. Trends Microbiol. 17(12):554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutet E, Lieberherr D, Tognolli M, Schneider M, Bansal P, Bridge AJ, Poux S, Bougueleret L, Xenarios I. 2016. UniProt/Swiss-Prot, the manually annotated section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase. Methods Mol Biol. 1374:23–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3167-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bove CB, Mudge L, Bruno JF. 2022. A century of warming on Caribbean reefs. PLOS Clim. 1(3):e0000002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt ME, Ennis RS, Meiling SS, Townsend J, Cobleigh K, Glahn A, Quetel J, Brandtneris V, Henderson LM, Smith TB. 2021. The emergence and initial impact of stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) in the United States Virgin Islands. Front Mar Sci. 8:715329. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.715329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brůna T, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M. 2020. GeneMark-EP+: eukaryotic gene prediction with self-training in the space of genes and proteins. NAR Genom Bioinform. 2(2):lqaa026. doi: 10.1093/nargab/lqaa026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. 2015. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 12(1):59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd AF, Johnson KG, Stemann TA, Tompkins B. 1999. Pliocene to Pleistocene reef coral assemblages in the Limon Group of Costa Rica. Bull Am Paleontol. 113(357):119–158. [Google Scholar]

- Burton KW, Ling H-F, O’Nions RK. 1997. Closure of the Central American Isthmus and its effect on deep-water formation in the North Atlantic. Nature. 386(6623):382–385. doi: 10.1038/386382a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Zhou G, Tian R-M, Tong H, Zhang W, Sun J, Ding W, Wong YH, Xie JY, Qiu J-W, et al. 2017. Metagenomic analysis reveals a green sulfur bacterium as a potential coral symbiont. Sci Rep. 7(1):9320. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavada-Blanco F, Croquer A, Vermeij M, Goergen L, Rodriguez-Martinez R. 2022. Dendrogyra cylindrus. IUCN red list of threatened species. [accessed 2023 Jun 4]. e.T133124A129721366.

- Changsut I, Womack HR, Shickle A, Sharp KH, Fuess LE. 2022. Variation in symbiont density is linked to changes in constitutive immunity in the facultatively symbiotic coral, Astrangia poculata. Biol Lett. 18(11):20220273. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2022.0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JA, Kirkness EF, Simakov O, Hampson SE, Mitros T, Weinmaier T, Rattei T, Balasubramanian PG, Borman J, Busam D, et al. 2010. The dynamic genome of Hydra. Nature. 464(7288):592–596. doi: 10.1038/nature08830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-H, Yang S-H, Tandon K, Lu C-Y, Chen H-J, Shih C-J, Tang S-L. 2021. Potential syntrophic relationship between coral-associated Prosthecochloris and its companion sulfate-reducing bacterium unveiled by genomic analysis. Microb Genom. 7(5):000574. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke I, Ying H, Forêt S, Bongaerts P, Strugnell JM, Simakov O, Zhang J, Field MA, Rodriguez-Lanetty M, Bell SC, et al. 2020. Genomic signatures in the coral holobiont reveal host adaptations driven by Holocene climate change and reef specific symbionts. Sci Adv. 6(48):eabc6318. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc6318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craggs J, Guest JR, Davis M, Simmons J, Dashti E, Sweet M. 2017. Inducing broadcast coral spawning ex situ: closed system mesocosm design and husbandry protocol. Ecol Evol. 7(24):11066–11078. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer KL, Jackson JBC, Donovan MK, Greenstein BJ, Korpanty CA, Cook GM, Pandolfi JM. 2020. Widespread loss of Caribbean acroporid corals was underway before coral bleaching and disease outbreaks. Sci Adv. 6(17):eaax9395. doi: 10.1126/SCIADV.AAX9395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO, Whitwham A, Keane T, McCarthy SA, Davies RM, et al. 2021. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 10(2):1–4. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo MK, Sunagawa S, Voolstra CR, Medina M. 2010. Transcriptomic responses to heat stress and bleaching in the elkhorn coral Acropora palmata. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 402:97–113. doi: 10.3354/meps08372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin-Durante MK, Miller MW, Group CAR, Precht WF, Baums IB. 2016. How old are you? Genet age estimates in a clonal animal. Mol Ecol. 25(22):5628–5646. doi: 10.1111/mec.13865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emms DM, Kelly S. 2019. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faichney IDE, Webster JM, Clague DA, Braga JC, Renema W, Potts DC. 2011. The impact of the Mid-Pleistocene Transition on the composition of submerged reefs of the Maui Nui Complex, Hawaii. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 299(3–4):493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.11.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Cheng H, Portik D, Li H. 2022. Metagenome assembly of high-fidelity long reads with hifiasm-meta. Nat Methods. 19(6):671–674. doi: 10.1038/s41592-022-01478-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JM, Hubley R, Goubert C, Rosen J, Clark AG, Feschotte C, Smit AF. 2020. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 117(17):9451–9457. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.1921046117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourreau CJL, Kise H, Santander MD, Pirro S, Maronna MM, Poliseno A, Santos MEA, Reimer JD. 2023. Genome sizes and repeatome evolution in zoantharians (Cnidaria: Hexacorallia: Zoantharia). PeerJ. 11:e16188. doi: 10.7717/peerj.16188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller ZL, Mocellin VJL, Morris LA, Cantin N, Shepherd J, Sarre L, Peng J, Liao Y, Pickrell J, Andolfatto P, et al. 2020. Population genetics of the coral Acropora millepora: toward genomic prediction of bleaching. Science. 369(6501):eaba4674. doi: 10.1126/SCIENCE.ABA4674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido AG, Machado LF, Zilberberg C, Leite DC. 2021. Insights into ‘Symbiodiniaceae phycosphere’ in a coral holobiont. Symbiosis. 83(1):25–39. doi: 10.1007/s13199-020-00735-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geertsma RC, Wijgerde T, Latijnhouwers KRW, Chamberland VF. 2022. Onset of zooplanktivory and optimal water flow rates for prey capture in newly settled polyps of ten Caribbean coral species. Coral Reefs. 41(6):1651–1664. doi: 10.1007/s00338-022-02310-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goergen L, Vermeij M. 2022. Colpophyllia natans. IUCN red list of threatened species. [accessed 2023 Jun 4]. e.T132884A165613226.

- Gold DA, Katsuki T, Li Y, Yan X, Regulski M, Ibberson D, Holstein T, Steele RE, Jacobs DK, Greenspan RJ. 2019. The genome of the jellyfish Aurelia and the evolution of animal complexity. Nat Ecol Evol. 3(1):96–104. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, et al. 2011. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 29(7):644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio Ad. 1930. Sul Permiano di Sicilia (Fossili del calcare con Fusulina di palazzo adriano non descritti del Prof. G. Gemmellaro conservati nel mio private Gabinetto). Ann Géol Paléontol. 52:18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guan D, Guan D, McCarthy SA, Wood J, Howe K, Wang Y, Durbin R, Durbin R. 2020. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 36(9):2896–2898. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTAA025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Salzberg SL, Zhu W, Pertea M, Allen JE, Orvis J, White O, Robin CR, Wortman JR. 2008. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 9(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M, Schröder K, Bathia J, Kürn U, Fraune S, Khalturina M, Khalturin K, Shinzato C, Satoh N, Bosch TCG. 2018. Metabolic co-dependence drives the evolutionarily ancient Hydra–Chlorella symbiosis. eLife. 7:e35122. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman TE, Barshis DJ, Hauff Salas B, Hamsher SE, Strychar KB. 2022. Indications of symbiotic state influencing melanin-synthesis immune response in the facultative coral Astrangia poculata. Dis Aquat Organ. 151:63–74. doi: 10.3354/dao03695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MA, Clark J, Ireland A, Lomax J, Ashburner M, Foulger R, Eilbeck K, Lewis S, Marshall B, Mungall C, et al. 2004. The gene ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 32(90001):D258–D261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JS, Kim H, Nason JD, Wing RA, Wendel JF. 2006. Differential lineage-specific amplification of transposable elements is responsible for genome size variation in Gossypium. Genome Res. 16(10):1252–1261. doi: 10.1101/gr.5282906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazewinkel M, Van Eijck J. 2000. Graph clustering by flow simulation [dissertation]. University of Utrecht. [accessed 2023 Apr 17]. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/848.

- Helgoe J, Davy SK, Weis VM, Rodriguez-Lanetty M. 2024. Triggers, cascades, and endpoints: connecting the dots of coral bleaching mechanisms. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 99(3):715–752. doi: 10.1111/brv.13042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath KM, Castillo KD, Armstrong P, Westfield IT, Courtney T, Ries JB. 2016. Next-century ocean acidification and warming both reduce calcification rate, but only acidification alters skeletal morphology of reef-building coral Siderastrea siderea. Sci Rep. 6(1):29613. doi: 10.1038/srep29613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CRL, Burns KH, Boeke JD. 2012. Active transposition in genomes. Annu Rev Genet. 46(1):651–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Zhang H, Wu P, Entwistle S, Li X, Yohe T, Yi H, Yang Z, Yin Y. 2018. DbCAN-seq: a database of carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZyme) sequence and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46(D1):D516–D521. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Cepas J, Szklarczyk D, Heller D, Hernández-Plaza A, Forslund SK, Cook H, Mende DR, Letunic I, Rattei T, Jensen LJ, et al. 2019. EggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(D1):D309–D314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume BCC, Smith EG, Ziegler M, Warrington HJM, Burt JA, LaJeunesse TC, Wiedenmann J, Voolstra CR. 2019. SymPortal: a novel analytical framework and platform for coral algal symbiont next-generation sequencing ITS2 profiling. Mol Ecol Resour. 19(4):1063–1080. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bork P, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L, et al. 2009. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37(Database):D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter IG, Jones B. 1996. Coral associations of the Pleistocene Ironshore Formation, Grand Cayman. Coral Reefs. 15(4):249–267. doi: 10.1007/BF01787459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kardos M, Armstrong EE, Fitzpatrick SW, Hauser S, Hedrick PW, Miller JM, Tallmon DA, Funk WC. 2021. The crucial role of genome-wide genetic variation in conservation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 118(48):e2104642118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2104642118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Choi JP, Kim MS, Jo Y, Min WG, Woo S, Yum S, Bhak J. 2022. Comparative genome and evolution analyses of an endangered stony coral species Dendrophyllia cribrosa near Dokdo Islands in the East Sea. Genome Biol Evol. 14(9):evac132. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evac132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AM, Sturm AB, Eckert RJ, Walker BK, Neely KL, Voss JD. 2024. Algal symbiont genera but not coral host genotypes correlate to stony coral tissue loss disease susceptibility among Orbicella faveolata colonies in South Florida. Front Mar Sci. 11:1287457. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1287457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klopfenstein DV, Zhang L, Pedersen BS, Ramírez F, Warwick Vesztrocy A, Naldi A, Mungall CJ, Yunes JM, Botvinnik O, Weigel M, et al. 2018. GOATOOLS: a Python library for gene ontology analyses. Sci Rep. 8(1):10872. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28948-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon T, Kon-Nanjo K, Simakov O. 2024. Expansion of a single Helitron subfamily in Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus suggests a shared mechanism of cnidarian chromosomal extension. bioRxiv 624632. 10.1101/2024.11.21.624632, preprint: not peer reviewed. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger F, James F, Ewels P, Afyounian E, Schuster-Boeckler B. 2021. FelixKrueger/TrimGalore: v0.6.7 [Software]. Zenodo. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.5127899. [DOI]

- Kvitt H, Rosenfeld H, Zandbank K, Tchernov D. 2011. Regulation of apoptotic pathways by Stylophora pistillata (Anthozoa, Pocilloporidae) to survive thermal stress and bleaching. PLoS One. 6(12):e28665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laetsch DR, Blaxter ML. 2017. BlobTools: interrogation of genome assemblies. F1000Res. 6:1287. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12232.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaJeunesse TC, Thornhill DJ. 2011. Improved resolution of reef-coral endosymbiont (Symbiodinium) species diversity, ecology, and evolution through psbA non-coding region genotyping. PLoS One. 6(12):e29013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclère L, Horin C, Chevalier S, Lapébie P, Dru P, Peron S, Jager M, Condamine T, Pottin K, Romano S, et al. 2019. The genome of the jellyfish Clytia hemisphaerica and the evolution of the cnidarian life-cycle. Nat Ecol Evol. 3(5):801–810. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0833-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AM, Chan AN, LaJeunesse TC. 2019. New species of closely related endosymbiotic dinoflagellates in the Greater Caribbean have niches corresponding to host coral phylogeny. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 66(3):469–482. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 2018. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 34(18):3094–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew YJ, Aranda M, Voolstra CR. 2016. Reefgenomics.org—a repository for marine genomics data. Database (Oxford). 2016:baw152. doi: 10.1093/database/baw152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli NS, Kitchen SA, Stankiewicz KH, Osborne CC, Dellaert Z, Elder H, Kamel B, Koch HR, Fogarty ND, Baums IB. 2024. Chromosome-level genome assemblies and genetic maps reveal heterochiasmy and macrosynteny in endangered Atlantic Acropora. BMC Genomics. 25(1):1119. doi: 10.1186/s12864-024-11025-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López EH, Palumbi SR. 2020. Somatic mutations and genome stability maintenance in clonal coral colonies. Mol Biol Evol. 37(3):828–838. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manni M, Berkeley MR, Seppey M, Simão FA, Zdobnov EM. 2021. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 38(10):4647–4654. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marçais G, Kingsford C. 2011. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 27(6):764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhaver KL, Vermeij MJA, Medina MM. 2015. Reproductive natural history and successful juvenile propagation of the threatened Caribbean Pillar Coral Dendrogyra cylindrus. BMC Ecol. 15(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12898-015-0039-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield AB. 2022. Machine-learning-based proteomic predictive modeling with thermally-challenged Caribbean reef corals. Diversity (Basel). 14(1):33. doi: 10.3390/d14010033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna V, Archibald JM, Beinart R, Dawson MN, Hentschel U, Keeling PJ, Lopez JV, Martín-Durán JM, Petersen JM, Sigwart JD, et al. 2021. The Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics Project: probing the evolution of symbiosis across the tree of life. Wellcome Open Res. 6(254):254. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.17222.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes FK, Vanderpool D, Fulton B, Hahn MW. 2021. CAFE 5 models variation in evolutionary rates among gene families. Bioinformatics. 36(22–23):5516–5518. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael TP. 2014. Plant genome size variation: bloating and purging DNA. Brief Funct Genomics. 13(4):308–317. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elu005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modys AB, Toth LT, Mortlock RA, Oleinik AE, Precht WF. 2023. Discovery of a rare pillar coral (Dendrogyra cylindrus) death assemblage off southeast Florida reveals multi-century persistence during the late Holocene. Coral Reefs. 42(4):801–807. doi: 10.1007/s00338-023-02387-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neely KL, Lewis CL, Lunz KS, Kabay L. 2021. Rapid population decline of the pillar coral Dendrogyra cylindrus along the Florida reef tract. Front Mar Sci. 8:434. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.656515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noel B, Denoeud F, Rouan A, Buitrago-López C, Capasso L, Poulain J, Boissin E, Pousse M, Da Silva C, Couloux A, et al. 2023. Pervasive tandem duplications and convergent evolution shape coral genomes. Genome Biol. 24(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s13059-023-02960-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea A, Lessios HA, Coates AG, Eytan RI, Restrepo-Moreno SA, Cione AL, Collins LS, de Queiroz A, Farris DW, Norris RD, et al. 2016. Formation of the Isthmus of Panama. Sci Adv. 2(8):e1600883. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil KL, Serafin RM, Patterson JT, Craggs JRK. 2021. Repeated ex situ spawning in two highly disease susceptible corals in the family Meandrinidae. Front Mar Sci. 8:669976. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.669976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palacio-Castro AM, Dennison CE, Rosales SM, Baker AC. 2021. Variation in susceptibility among three Caribbean coral species and their algal symbionts indicates the threatened staghorn coral, Acropora cervicornis, is particularly susceptible to elevated nutrients and heat stress. Coral Reefs. 40(5):1601–1613. doi: 10.1007/s00338-021-02159-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CV, Bythell JC, Willis BL. 2012. Enzyme activity demonstrates multiple pathways of innate immunity in Indo-Pacific anthozoans. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 279(1743):3879–3887. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JM, Stajich J. 2020. nextgenusfs/funannotate: funannotate v1.8.13 [Software]. Zenodo. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4054262. [DOI]

- Park E, Hwang D-S, Lee J-S, Song J-I, Seo T-K, Won Y-J. 2012. Estimation of divergence times in cnidarian evolution based on mitochondrial protein-coding genes and the fossil record. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 62(1):329–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters SE, McClennen M. 2016. The Paleobiology Database application programming interface. Paleobiology. 42(1):1–7. doi: 10.1017/pab.2015.39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzón JHC, Beach-Letendre J, Weil E, Mydlarz LD. 2014. Relationship between phylogeny and immunity suggests older Caribbean coral lineages are more resistant to disease. PLoS One. 9(8):e104787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pootakham W, Sonthirod C, Naktang C, Kongjandtre N, Putchim L, Sangsrakru D, Yoocha T, Tangphatsornruang S. 2021. De novo assembly of the brain coral Platygyra sinensis genome. Front Mar Sci. 8:732650. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.732650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prada C, Hanna B, Budd AF, Woodley CM, Schmutz J, Grimwood J, Iglesias-Prieto R, Pandolfi JM, Levitan D, Johnson KG, et al. 2016. Empty niches after extinctions increase population sizes of modern corals. Curr Biol. 26(23):3190–3194. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. 2010. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 5(3):e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proost S, Fostier J, De Witte D, Dhoedt B, Demeester P, Van De Peer Y, Vandepoele K. 2012. i-ADHoRe 3.0-fast and sensitive detection of genomic homology in extremely large data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 40(2):e11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi W. 1984. An Anisian coral fauna in Guizhou, South China. Palaeontogr Am. 54:187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ranallo-Benavidez TR, Jaron KS, Schatz MC. 2020. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 11(1):1432. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14998-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]