Abstract

Background

Endometriosis affects women of reproductive age. Increasing attention is being given to the characterization of comorbidities in endometriosis to enhance clinical phenotyping. Among these comorbidities, migraine has been reported to be significantly more common in individuals with endometriosis compared to the general population. However, the true epidemiological burden remains uncertain, and no conclusive evidence links specific subtypes of endometriosis to migraine.

Main body

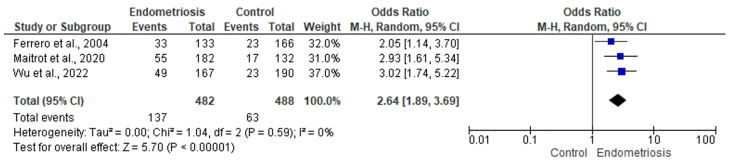

Seven electronic databases were searched from inception until July 22nd, 2024, using combinations of relevant keywords. PROSPERO Registration CRD42023449492. Two independent reviewers screened the records according to inclusion/exclusion criteria and abstracted data. The risk of bias assessment was undertaken using the ROBINS-E tool. Random effects models were implemented to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between endometriosis and migraine. Fourteen studies were included in the qualitative synthesis, and 13 in the meta-analysis, accounting for a total of 331,655 individuals (32,489 with endometriosis vs. 299,166 controls). There was a serious risk of bias in the majority of the included studies, with 50% being at very high risk of bias. The risk of migraine was higher in individuals with endometriosis compared to those without (OR 2.25, 95%CI = 1.85–2.72; n = 13 studies; I2 = 81%). This association remained significant in the sensitivity analyses: (i) when excluding studies at very high or high risk of bias (OR 2.64; 95%CI = 1.62–4.31; n = 4 studies; I2 = 77%), (ii) when including only risk estimates adjusted for clinically relevant confounders (OR 2.35; 95%CI = 1.77–3.13; n = 6 studies; I2 = 88%), and (iii) when including only risk estimates adjusted for hormonal therapy (OR 1.95; 95%CI = 1.42–2.66; n = 3; I2 = 92%). Endometriosis was significantly associated with migraine without aura (OR 2.64, 95%CI 1.89–3.69; n = 3 studies; I2 = 0%), but not migraine with aura (OR 3.47, 95%CI = 0.53–22.89; n = 3, I2 = 73%).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis highlights the high prevalence of migraine in patients with endometriosis. However, due to observed high heterogeneity and risk of bias, caution is advised when interpreting and applying these findings in clinical practice. Future research should address these issues by limiting variations in diagnostic criteria, stratifying study populations, accounting for key confounders, and investigating potential underlying pathophysiological mechanisms to enhance understanding of the endometriosis-migraine relationship.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s10194-025-02020-4.

Keywords: Migraine, Endometriosis, Pelvic pain, Overlapping pain, Meta-analysis, Migraine with aura, Genetics

Introduction

Endometriosis is a multifaceted disease characterized by complex epidemiological, etiological, diagnostic, phenotypic and prognostic features [1]. It predominantly affects young women of reproductive age, with a peak incidence rate of 6 per 1,000 person-years in the 30–34 age range [2]. Growing evidence suggests that considering endometriosis exclusively as a pelvic gynecological disorder fails to capture its complex nature and heterogenous clinical manifestations, including its association with multiple comorbidities [3].

Among these comorbidities, the association between endometriosis and migraine, supported by various studies [3–7], warrants special attention. Individuals with endometriosis are more likely to have migraine, and similarly, the prevalence of endometriosis is higher in patients with migraine compared to the general population [3, 4, 6–8]. Migraine disproportionately affects women, with an incidence rate more than double the rate for men (23 per 1000 person-years compared to 10 per 1000 person-years) [12–14]. Moreover, it occurs most commonly in young women of reproductive age, with peak incidence between 25 and 34 years old [9]. Notably, pain is a central feature of both endometriosis and migraine, significantly worsening quality of life and interfering with daily activities [10–12]. Recent studies have also uncovered a strong and significant genetic overlap between endometriosis and migraine [13–15], further supporting this association [3–5]. Finally, both endometriosis and migraine have been linked to similar comorbidities, including autoimmune-related traits, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome [16–20].

However, an epidemiological association of endometriosis with specific migraine subtypes such as with or without aura, as well as the effect of clinical covariates, including hormonal factors, has not yet been fully elucidated. Considering that menstruation is an important migraine trigger [21] and estrogen withdrawal has been suggested to trigger migraine [22], hormonal factors are indeed an important aspect when investigating this link.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to quantify the risk of migraine in individuals with endometriosis. Additionally, we aimed to gain understanding of this link by exploring whether endometriosis is associated with various migraine subtypes, and whether this association was maintained when considering only high quality studies. Although this has been previously explored in a meta-analysis [6], our study provides an updated perspective by incorporating the latest available literature with a greater number of records included in the analysis and offering new insights into the association between these conditions by conducting multiple subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Methods

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [23] and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [24]. The study protocol was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023449492). Ethical approval and informed consent were not needed in accordance with 45CFR§ 46.

Eligibility criteria, study selection and search strategy

The following databases were searched from inception up to July 22nd, 2024: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid MEDLINE and Embase via OvidSP, and CINAHL. ClinicalTrials.gov was used to search for ongoing and registered trials; OpenGrey and Google.com were used to search for grey literature. The electronic search algorithm consisted of MeSH terms “endometriosis”, “headache”, and “migraine” with all subheadings explored; the terms were then combined with “and”. The full search strategy is presented in Supplementary Appendix. Reference lists of relevant articles were backwards searched to identify papers not captured by the electronic searches. No restrictions were applied to publication date or language. The literature search and article eligibility were independently assessed by two authors (G.E.C. and S.M.), with any disagreements resolved through discussion with a third author (D.R.K.).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The PICOS framework was used to assess study eligibility as follows: (i) Population: individuals with endometriosis, diagnosed by surgery, imaging, clinical assessment, International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes, or self-report [25]; (ii) Intervention/Exposure: migraine, diagnosed by clinical assessment by a neurologist, ICD codes, questionnaire, interview, or self-report, with the preferred diagnostic method being the application of the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition criteria created by the Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) [26]; (iii) Comparator: individuals without a diagnosis of endometriosis and with no chronic pelvic pain, although no specific exclusion of endometriosis was required; (iv) Outcome: pooled risk of migraine in endometriosis compared to controls; Study type: peer-reviewed cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies. Case reports, case series, or any studies without a comparison population (control group), animal studies, conference abstracts, review articles, editorials, or commentaries were excluded. In the case of multiple publications from the same source population, only the most recent publication was included to avoid amplifying the effect of the same cohort on the pooled estimate.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by two authors (G.E.C. and S.M.). The following data were collected and tabulated: first author, publication year, study country, study design, study period, sample size (number of endometriosis cases and number of controls), frequency of migraine in cases and controls, diagnostic modalities for endometriosis and migraine, baseline characteristics of study participants (including mean age, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, cigarette smoking status, co-morbidities, parity, and infertility history), menopausal status, treatment of endometriosis and migraine, confounding factors adjusted for in the analysis. Additionally, we collected data on the localization and stage of endometriosis lesions in accordance with the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification [27], categorizing stages I-II as minimal-to-mild disease, and stages III-IV as moderate-to-severe disease [27]. When data were missing or unclear, the authors of the included studies were contacted for clarification.

Assessment of risk of bias and certainty of the evidence

The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Exposure (ROBINS-E) tool [28] from the updated Cochrane collaboration guidelines was utilized for the assessment of methodological quality of included studies. Seven domains of bias were assessed, including:1) confounding, 2) measurement of the exposure, 3) the selection of participants into a study, 4) post-exposure interventions, 5) missing data, 6) measurement of the outcome, and 7) selection of the reported result. In the domain of bias due to confounding, a study was rated as “very high” risk of bias if it did not report any effect estimates, “high” risk of bias if it reported unadjusted risk estimates, “moderate” risk of bias if it reported effect estimates adjusted for a single confounding factor, and “low” risk of bias if it reported effect estimates adjusted for multiple confounding factors. A study was considered at low risk of bias if it was rated ‘low’ in all domains; a rating of some concerns if it was rated as ‘some concerns’ in one domain; high risk of bias if rated as ‘high’ in one domain, and very high risk of bias if rated as ‘very high’ in one domain [28]. Each study was assessed independently by two authors (G.E.C. and S.M.); when disagreement occurred, consensus was achieved via discussion.

The certainty of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [29]. Guidance from the Grade Handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations [30] was utilized to make the assessment, and the GradePRO Guideline Development Tool software [31] was utilized to create a Summary of Findings table. Starting from a certainty of “high” for randomized controlled studies, GRADE allows for downgrading if one or more of five domains suggests limitations in the certainty of the evidence (risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias). For nonrandomized studies, the initial certainty starts at low, then five downgrading domains and three upgrading domains (large effect, dose–response gradient, and plausible confounding) are assessed.

Meta-analysis methods

Data synthesis

Original data on binary outcome measures were extrapolated from included studies so that Log Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) were computed and pooled together. A random effects model was applied to estimate the pooled effect size for every investigated outcome [32]. The overall effect size was estimated as the weighted average of study-specific effect sizes, with larger studies having greater weights and smaller studies having lesser weights. Forest plots were used to present study-specific and overall effect sizes together with 95% CI.

Between-study heterogeneity was represented by the I2 index which estimates the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to between-study heterogeneity rather than due to sampling variation. I2 index values were interpreted as follows: a value of up to 50% was considered low heterogeneity, 51–75% moderate heterogeneity, and > 75% high heterogeneity [33]. Publication bias was identified using the linear regression-based method according to Egger et al. [34]. Meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager (RevMan) for Mac (Version 5.3) [35].

Comparison groups

The primary analysis to answer the research question was obtained by comparing pooled data on the risk of migraine in endometriosis patients versus controls. Secondary outcomes included the risk of migraine with aura in individuals with endometriosis compared to controls. Additionally, we planned to provide pooled risk estimates according to endometriosis disease stage (by rASRM) and localization (deep lesions, ovarian endometriomas and superficial endometriosis), as outlined in the PROSPERO study protocol.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the results, accounting for the ROBINS-E risk of bias rating, any adjustment for confounding factors (e.g. age, BMI) and for hormonal therapy. Subgroup analyses were implemented to explore potential sources of heterogeneity in the estimates, considering the endometriosis diagnostic method (laparoscopic or non-laparoscopic diagnosis), and migraine diagnostic method (neurologist, ICD codes, questionnaire, interview, self-report). All sensitivity and subgroup analyses were a priori planned; however, an additional sensitivity analysis not outlined in the PROSPERO study protocol was conducted for the specific confounder of hormonal therapy, given the availability of sufficient data for pooling.

Results

The screening process identified 1,536 records, of which 220 were duplicates, leaving 1,316 records to be screened. Following title and abstract screening, 1,283 records did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 33 studies were eligible for full-text screening (Table S1). Fourteen studies were included in the qualitative synthesis [4–7, 10, 15, 36–43]. Thirteen studies were included in the meta-analysis, accounting for a total of 331,655 individuals (32,489 with endometriosis vs. 299,166 controls). The PRISMA flow diagram showing the process of literature selection is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flowchart of study selection. Abbreviations: CENTRAL Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; ICTRP International Clinical Trials Registry Platform; PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

Of the fourteen studies included in the qualitative synthesis, most were cross-sectional (n = 6), with the remaining being case-control (n = 4), retrospective cohort (n = 3), or prospective cohort (n = 1) studies. Most of the included studies (n = 5) were conducted in the United States. The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies

| Author, year, location | Design | Number of endometriosis cases | Endometriosis diagnostic method | Number of controls | Migraine diagnostic method | Result N (%) with migraine |

Adjustment factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrero et al. 2004, Italy [7] | Cross-sectional | 133 | Laparoscopy and histology | 166 | Clinical by neurologist |

Exposure: 51 (38.3%) Control: 25 (15.1%)* Migraine without aura: Exposure: 33 (24.8%) Control: 23 (13.9%) Migraine with aura: Exposure: 18 (13.5%) Control: 2 (1.2%) |

N/A |

| Gete et al. 2023, Australia [42] | Prospective cohort | 1,149 | Self-reported | 6,457 | Self-reported |

Exposure: 682 (59%) Control: 3,312 (51%)* |

Age, residence, marital status, education, income, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, BMI, parity, use of hormonal therapy |

| Karamustafaoglu et al. 2019, Turkey [44] | Cross-sectional | 114 | Laparoscopy | 97 | Questionnaire |

Exposure: 51 (69%) Control: 26 (43%)* |

N/A |

| Maitrot et al. 2020, France [49] | Case-control | 182 | Laparoscopy and histology | 132 | Questionnaire |

Exposure: 64 (35.2%) Control: 23 (17.4%)* Migraine without aura: Exposure: 55 (30.2%) Control: 17 (12.9%) Migraine with aura: Exposure: 9 (4.9%) Control: 6 (4.5%) |

Age, BMI, and family history of migraine |

| Miller et al. 2018, USA [5] | Cross-sectional | 296 | Laparoscopy | 95 | Self-reported |

Exposure: 205 (87.2%) Control: 30 (12.8%) |

Age, race, use of hormonal therapy |

| Mirkin et al. 2007, USA [41] | Retrospective cohort | 40,150 MY | ICD codes | 7,144,896 MY | ICD codes |

Exposure: 8.9% Control: 4%* |

N/A |

| Nyholt et al. 2009, Australia [40] | Cross-sectional | 767 | Self-reported | 164 | Telephone interview |

Exposure: 285 (37%) Control: 50 (30%) |

N/A |

| Stratton et al. 2015, USA [45] | Cross-sectional | 18 | Laparoscopy and histology | 20 | Structured interview |

Exposure: 11 (61%) Control: 0* |

N/A |

| Sultana et al. 2024, Bangladesh [43] | Case-control | 190 | Laparoscopy or laparotomy | 190 | Clinical by neurologist |

Exposure: 27 (14.2%) Control: 5 (2.6%)* |

Age, BMI |

| Tietjen et al. 2007, USA [46] | Cross-sectional | 46 | Self-report of laparoscopy | 229 | Clinical by neurologist |

Exposure: 36 (78.3%) Control: 127 (55.5%) |

N/A |

| Tietjen et al. 2006, USA [4] | Case-control | 16 | Self-report of laparoscopy | 86 | Clinical by neurologist |

Exposure: 14 (87.5%) Control: 36 (41.9%) |

N/A |

| Wu et al. 2018, Taiwan [47] | Retrospective cohort | 9,191 | ICD codes | 27,573 | ICD codes |

Exposure: 398 (4.3%) Control: 36 (41.9%)** |

N/A |

| Wu et al. 2022, China [48] | Case-control | 167 | Laparoscopy | 190 | Clinical by neurologist |

Exposure: 50 (29.9%) Control: 23 (12.1%)* Migraine without aura: Exposure: 49 (29.3%) Control: 23 (12.1%) Migraine with aura: Exposure: 1 (0.6%) Control: 0 |

N/A |

| Yang et al. 2012, Taiwan [6] | Retrospective cohort | 20,220 | ICD codes | 263,767 | ICD codes |

Exposure: 985 (4.9%) Control: 7,701 (2.9%)* |

Age, use of hormonal therapy |

N/A – not applicable; NR – not reported, OR – odds ratio; BMI – Body mass index; ICD – International Classification of Disease; MY – member years (total days of eligibility of an individual divided by 365)

* p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05

Risks of migraine in endometriosis patients versus controls

Study overview

The population size of the included studies was highly variable, with n = 283,987 individuals derived from the largest study [6] and n = 38 individuals included in the smallest [40]. In half of the included studies the diagnosis of endometriosis was based on laparoscopic confirmation of the disease [5, 7, 10, 38–40, 43]; four studies (28.5%) diagnosed endometriosis via self-report [4, 15, 37, 41], and the remaining three studies (21.5%) diagnosed endometriosis via ICD codes [6, 36, 42]. Only Wu et al., 2022 [43] reported data on endometriosis severity according to the r-ASRM staging system [27]. Four of the included studies [7, 10, 38, 43] performed laparoscopy to rule out endometriosis in controls. Migraine diagnostic method was highly heterogeneous, with 5 studies achieving diagnosis via interview with a neurologist applying IHS criteria, 3 studies adopting ICD codes in insurance databases, 2 studies via questionnaires applying IHS criteria, 2 studies via self-reported diagnosis, one study via telephone interview applying IHS criteria, and one study via self-report and clinical interview. Three studies provided risk estimates adjusted for use of hormonal therapy [5, 6, 37]. Since Tietjen et al. 2006 [4] and Tietjen et al. 2007 [41] were conducted one year apart, the author was contacted and confirmed that the study populations were distinct.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias assessment found a serious risk of bias in the majority of the included studies, with 50% of studies (n = 7) being at very high risk of bias, 21% (n = 3) at high risk of bias, 14.5% of studies (n = 2) rated as ‘some concerns’, and 14.5% (n = 2) judged as at low risk of bias (Figure S1). Bias due to confounding was the section most often ranked as very high risk. Nyholt et al., 2009 [15] was ranked as high risk of bias in three domains: confounding, exposure assessment, and missing data. Mirkin et al., 2007 [36] and Tietjen et al., 2007 [41] were ranked as very high risk of bias due to confounding and high risk of bias due to exposure assessment. Gete et al., 2023 [37] was ranked as very high risk of bias in selection of participants into the study and high risk of bias in selection of the reported result. No other studies were ranked as very high or high risk of bias in more than one category.

Data analysis

Meta-analysis of the 13 included studies revealed a greater risk of migraine in individuals with endometriosis compared to controls (OR 2.25; 95% CI = 1.85–2.72; n = 13 studies) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 81%) and non-significant publication bias (Egger’s, p = 0.83) (Fig. 2). The certainty of the evidence according to GRADE was graded as Low (Table 2): downgraded two levels due to very high risk of bias, downgraded one level due to indirectness (multiple diagnostic methods were accepted, the population settings varied, and not all studies excluded endometriosis in the control group), and upgraded one level for strong association (OR > 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for the association between endometriosis and migraine diagnosis

Table 2.

Assessment of certainty of evidence using the GRADE evidence profile

| Certainty assessment | No of patients | Effect | Certainty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | endometriosis | control | Relative (95% CI) |

Absolute (95% CI) |

|

| Migraine | |||||||||||

| 13 | Observational studies | very seriousa | not serious | seriousb | not serious | strong association | 2,859/32,489 (8.8%) | 12,030/299,166 (4.0%) |

OR 2.25 (1.85 to 2.72) |

46 more per 1,000 (from 32 more to 62 more) |

⨁⨁◯◯ Lowa, b |

| Migraine without aura | |||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | very seriousc | not serious | seriousb | not serious | strong association | 137/482 (28.4%) |

63/488 (12.9%) |

OR 2.64 (1.89 to 3.69) |

152 more per 1,000 (from 90 more to 224 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ Very lowb, c |

| Migraine with aura | |||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | very seriousc | seriousd | seriousb | very seriouse | limited evidence, heterogeneity of findings |

28/482 (5.8%) |

8/488 (1.6%) |

OR 3.47 (0.53 to 22.89) |

37 more per 1,000 (from 7 fewer to 255 more) |

⨁◯◯◯ Very lowb, c,d, e |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio

Explanations

a. 50% of studies (n = 7) at very high risk of bias, 21% (n = 3) at high risk of bias, 14.5% of studies (n = 3) rated as ‘some concerns’, and 14.5% (n = 3) at low risk of bias

b. Multiple diagnostic methods accepted, various population settings (e.g. neurology clinic), not all studies excluded endometriosis in the control group (e.g. negative laparoscopy)

c. 67% (n = 2) rated as ‘some concerns’ and 33% (n = 1) at very high risk of bias

d. One study found similar rates in both groups

e. 95% CI 0.53–22.89

Sensitivity analyses excluding studies at very high or high risk of bias by the ROBINS-E assessment confirmed that the risk of migraine was higher in endometriosis compared to controls (OR 2.64; 95% CI = 1.62–4.31; n = 4 studies; I2 = 77%) (Figure S2). The Egger’s test for this analysis showed some publication bias (p = 0.03). Sensitivity analysis including only studies which adjusted for clinically relevant confounders (full list of confounders adjusted for in each study is provided in Table 1) also confirmed an association between the two conditions (OR 2.35; 95% CI = 1.77–3.13; n = 6 studies; I2 = 88%), despite some publication bias (Egger’s, p = 0.04) (Figure S3). Sensitivity analysis including only studies which adjusted for hormonal therapy use also confirmed this association (OR 1.95; 95% CI = 1.42–2.66; n = 3 studies; I2 = 92%), with non-significant publication bias (Egger’s, p = 0.72) (Figure S4).

Subgroup analysis based on endometriosis diagnostic method showed a greater association in the studies that diagnosed endometriosis via laparoscopy in comparison to those with a non-surgical diagnosis: OR 3.48 (95% CI = 2.50–4.83; n = 7; I2 = 43%) vs. OR 1.65 (95% CI = 1.42–1.92; n = 6; I2 = 73%) (Figure S5). Non-significant publication bias was found for both studies based on surgical or non-surgical diagnosis (Egger’s, p = 0.28 and p = 0.66, respectively). When considering migraine diagnostic method, pooled risk estimates were higher when migraine was diagnosed by a neurologist (OR 3.38; 95% CI = 2.42–4.73; n = 4; I2 = 0%), with non-significant publication bias (Egger’s, p = 0.71) (Figure S6).

Risks of migraine without aura in endometriosis versus controls

Study overview

Three studies could be included for this specific comparison [7, 10, 43], accounting for a total of 970 individuals (482 with endometriosis vs. 488 controls).

Risk of bias assessment

Maitrot et al., 2020 [10] and Wu et al., 2022 [43] were rated as having “some concerns”, and Ferrero et al., 2004 [7] was rated at “very high” risk of bias (Figure S1).

Data analysis

Meta-analysis of the included studies revealed a greater risk of migraine without aura in individuals with endometriosis compared to controls (OR 2.64, 95% CI 1.89–3.69; n = 3 studies; I2 = 0%) (Fig. 3). There was no significant publication bias (Egger’s, p = 0.67).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for the association between endometriosis and migraine without aura diagnosis

The certainty of the evidence according to GRADE was graded as Very Low (Table 2): downgraded two levels due to very high risk of bias, downgraded one level due to indirectness (multiple diagnostic methods were accepted, the population settings varied, and not all studies excluded endometriosis in the control group), downgraded one level due to small number of studies/population, and upgraded one level for strong association (OR > 2).

Risks of migraine with aura in endometriosis versus controls

Study overview

Only three studies could be included in this comparison [7, 10, 43], accounting for a total of 970 individuals (482 with endometriosis vs. 488 controls).

Risk of bias assessment

Maitrot et al., 2020 [10] and Wu et al., 2022 [43] were rated as having “some concerns”, and Ferrero et al., 2004 [7] was rated at “very high” risk of bias (Figure S1).

Data analysis

Meta-analysis of the included studies showed a substantial uncertainty in the association between endometriosis and migraine with aura, with a very wide confidence interval (OR 3.47, 95% CI = 0.53–22.89; n = 3) and high heterogeneity (I2 = 73%). There was no significant publication bias (Egger’s, p = 0.66) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for the association between endometriosis and migraine with aura diagnosis

The certainty of the evidence according to GRADE was graded as Very Low (Table 2): downgraded two levels due to very high risk of bias, downgraded one level due to indirectness (multiple diagnostic methods were accepted, the population settings varied, and not all studies excluded endometriosis in the control group), and downgraded two levels due to imprecision (wide confidence interval crossing 0), and downgraded one level due to small number of studies/population.

Risk of migraine according to endometriosis severity and lesion localization

Study overview

Only one study reported on the risk of migraine according to endometriosis severity, and one according to lesion localization. Therefore, meta-analysis could not be performed. Wu et al., 2022 [43] reported rASRM stage and found that a diagnosis of migraine was more than four times more likely in individuals with moderate-severe endometriosis (rASRM stages III-IV) compared to those without endometriosis (OR 4.52; 95% CI = 2.49–8.20), whereas the association between migraine and minimal-mild endometriosis (rASRM stages I-II) was not statistically significant (OR 1.4; 95% CI = 0.64–3.05). Maitrot et al., 2020 [10] reported disease phenotypes: superficial peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometrioma, and deep infiltrating endometriosis. The risk of migraine was significantly increased in individuals with endometriomas (OR 2.78; 95% CI = 1.11–6.98) and deep infiltrating endometriosis (OR 2.51; 95% CI 1.25–5.07) in comparison to controls without endometriosis. The risk of migraine was not increased with superficial peritoneal endometriosis (OR 1.97; 95% CI = 0.88–4.40) in comparison to controls without endometriosis.

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 331,655 individuals across 13 studies confirms the association between endometriosis and migraine (Fig. 2), although the certainty of evidence was low (Table 2). When considering the secondary outcomes, meta-analysis revealed an increased risk of migraine without aura in individuals with endometriosis (Fig. 3). However, the association between endometriosis and the risk of migraine with aura was uncertain (Fig. 4). Further secondary outcomes explored included the association between migraine and endometriosis by severity or localization. In the single study that reported rASRM stage [43], migraine was associated with moderate-severe endometriosis. Similarly, in the single study addressing disease localization [10], ovarian endometriosis and deep lesions were associated with migraine, whereas superficial endometriosis was not. Given the importance of accounting for confounding factors, we conducted sensitivity analyses including only studies that reported adjusted effect estimates for clinically relevant confounders (Figure S3), including only studies rated as “some concerns” or “low” risk of bias (Figure S2), and pooling adjusted risk estimates for hormonal therapy use (Figure S4). All sensitivity analyses demonstrated a robust and consistent association between endometriosis and migraine. Furthermore, subgroup analysis confirmed that this association was stronger when endometriosis was diagnosed via laparoscopy (Figure S5) and migraine was confirmed through neurological assessment (Figure S6).

Interpretation

The potential biological mechanisms that could underlie the association between endometriosis and migraine include hormonal milieu, inflammation, and genetic predisposition. The hormonal milieu of the menstrual cycle may influence migraine through the ability of estrogen and progesterone to modify neurotransmitter systems linked with migraine pathogenesis [44–47]. Estrogen withdrawal has been suggested to trigger migraine [22]. Indeed, women with migraine experience a more rapid decline in estrogen levels during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle compared to controls, leading to an increased frequency of migraine attacks in the menstrual period [48]. Notably, the frequency of migraine attacks is higher during perimenopause, a time characterized by more frequent anovulatory cycles and fluctuating, lower estrogen levels [47, 49, 50]. While the precise interaction between female sex hormones and migraine remains to be fully defined, available data suggest an association. In this context, it is well-established that estrogens play a crucial role in endometriosis [51], promoting the growth of the ectopic endometrium that defines the disease. Therefore, the alterations in estrogen signaling observed in endometriosis may facilitate mechanisms underlying migraine [51]. When considering potential therapeutic implications, amenorrhea induced by first-line hormonal treatments has been shown to reduce menstrual-related migraine attacks triggered by hormonal withdrawal [52]. Moreover, in individuals with endometriosis and migraine without aura, continuous regimens with progestin-only pills (POPs) have been suggested to be highly effective in reducing migraine attacks [53], further supporting the key role of achieving amenorrhea. On the other hand, in the sensitivity analysis including only studies which adjusted for hormonal therapy the association between endometriosis and migraine was maintained.

In addition to the role of estrogens, the altered peritoneal environment in women with endometriosis triggers a robust inflammatory response, characterized by elevated levels of prostaglandins, cytokines, and chemokines [51, 54]. This inflammatory milieu appears to operate not only within the peritoneal cavity, contributing to the pathophysiology of pelvic endometriosis lesions, but also at a systemic level, partially underpinning its association with systemic immune dysregulatory and inflammatory conditions [55, 56]. Emerging evidence highlights the importance of neuro-inflammation in endometriosis, driven by interactions between nerve fibers and immune cells that trigger peripheral and central pain pathways [54]. Migraine shares similar mechanisms, with local inflammation triggering meningeal nociceptors and activating the trigeminovascular system, processes that are thought to drive migraine pain [57]. Furthermore, systemic inflammation appears to play a key role in migraine as in endometriosis, with elevated levels of serum inflammatory markers in individuals with migraine compared to controls [58].

In the context of endometriosis and migraine, the inflammatory and neuro-inflammatory processes associated with both conditions are likely to sensitize central pain pathways, predisposing individuals to the development of nociplastic pain—a type of pain arising from altered nociception, characterized by heightened central nervous system responsiveness to sensory input [59]. This heightened sensitivity amplifies pain perception, even in the absence of ongoing noxious stimuli, and contributes to widespread pain originating from multiple body sites. The concept of chronic overlapping pain conditions provides a useful framework for understanding this association. Chronic overlapping pain conditions refer to the coexistence of multiple pain disorders, such as migraine and endometriosis, in the same individuals, underpinned by shared mechanisms such as central sensitization, inflammation, and altered nociceptive processing [60].

Finally, there is growing evidence of a genetic link between endometriosis and migraine. An extensive investigation of genome-wide association study (GWAS) data identified multiple lead single nucleotide polymorphisms associated to both conditions [14]. Further support to this genetic overlap was confirmed in another GWAS analysis, which identified multiple loci linked to both conditions, though no causal relationship was established [13]. At the individual level, a study conducted in a twin population found a significant additive genetic correlation between endometriosis and migraine [15]. These findings suggest the existence of shared genetically controlled biological mechanisms between endometriosis and migraine.

Overall, it is quite challenging to infer which is exactly the biological mechanism underlying the association between the two diseases based on the available epidemiological evidence, primarily due to the scarcity of data pertaining to specific subgroups or affected populations. However, some plausible biological explanations supporting causality do exist.

Strengths and limitations

This meta-analysis adopted strict inclusion and exclusion criteria and was conducted with a rigorous methodology. Compared to the previous meta-analysis on this topic [3], it included a more extensive population, with 14 studies included in comparison to 9 in the previous review. This review performed multiple subgroup and sensitivity analyses to thoroughly investigate the association between endometriosis and migraine, whereas the previous review only conducted one subgroup analysis according to study design (i.e. cohort and case-control vs. cross-sectional). Additionally, although there was some overlap of studies included in both reviews, the previous review found that the records included were high quality, whereas a systematic assessment in this review found a high risk of bias, indicating stricter criteria and robust methodology in this review compared to the previous one [3].

However, several important limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. Notably, the majority of the included studies were rated as having a high or very high risk of bias. To address this limitation, we conducted a sensitivity analysis including only studies rated as having ‘some concerns’ or ‘low risk’ in the risk of bias assessment. The association between endometriosis and migraine remained significant. The principal cause of the high risk of bias was confounding, as few studies performed analyses adjusting for potential confounders. We tackled this issue through a separate sensitivity analysis including only studies that adjusted for confounders, and again the association persisted. Results not adjusted for confounding of potential migraine risk factors are less robust, as they could contribute to the increased risk of migraine if the exposure and control groups have baseline differences.

The findings of this review may have been influenced by this high risk of bias and lack of adjustment for confounders, but it is unclear whether the direction of the bias would make the association between endometriosis and migraine stronger or less strong. Another key limitation was the high heterogeneity of pooled estimates, reflecting substantial variability across studies and emphasizing the need for caution in interpreting these findings. Additionally, in both the sensitivity analyses excluding studies at high risk of bias and including only studies adjusting for confounders, the Egger’s test revealed significant publication bias. This suggests that studies reporting stronger associations may have been more likely to be published, potentially leading to an overestimation of the association between the two conditions.

Among the studies that included adjustment factors, only two considered hormonal therapy in their analyses, and just one accounted for surgical treatment of endometriosis. Both factors significantly influence the clinical manifestation of endometriosis and could therefore impact its association with migraine, making them important potential confounders. Another limitation relates to diagnostic methods. As outlined in the PROSPERO protocol (CRD42023449492), all diagnostic methods for endometriosis and migraine were accepted in order to gain the broadest possible overview of the available literature. Some of the included studies relied on self-reported diagnoses, which, while accounted for in the risk of bias assessment, may have introduced misclassification bias. To address this, a subgroup analysis based on endometriosis diagnostic method was conducted, which showed a greater association between endometriosis diagnosed via laparoscopy and migraine than other endometriosis diagnostic methods. However, the finding of a stronger association with migraine in individuals with endometriosis diagnosed via laparoscopy could be due to selection bias, another potential limitation to consider.

While informative clinical insights could potentially be gained from stratifying migraine risk according to endometriosis severity, this analysis was not feasible, as only one study [43] reported data on endometriosis stage according to the ASRM classification. Therefore, conclusions on this aspect should be drawn with caution. The variations in study designs, condition frequencies, diagnostic methods or unaccounted confounding factors across comparisons may introduce significant clinical heterogeneity.

Importantly, although the results of this review suggest a link between the two conditions and a biological plausibility can be proposed, no causal relationship between endometriosis and migraine has been established, and indeed the direction of this association is unclear. We cannot exclude that shared underlying risk factors might simply explain the association.

Implications for future research

Whilst this review suggests an association between endometriosis and migraine, further research is needed to establish this link with greater certainty. Future research should prioritize large, high-quality prospective studies with standardized diagnostic criteria and adjustment for confounding factors. Additionally, exploring whether the association changes based on endometriosis severity or migraine severity would provide new insights. Apart from the severity of the condition, the types of migraine, particularly migraine with and without aura, should investigated in future studies. The finding of publication bias in two sensitivity analyses indicates the possibility that not all research is being published, and studies which find no association between the conditions are also essential to understand this link.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggest an association between endometriosis and migraine, although given risk of bias, substantial heterogeneity among studies, residual confounding, and evidence of publication bias, these results should be interpreted with caution. Recognizing the overlap between these conditions may have implications for clinical practice, particularly in screening, diagnosis, treatment selection, and patient education. Despite the limitations, our findings underscore a noteworthy link that warrants further investigation. Future research should focus on larger, methodologically rigorous studies designed to account for clinically relevant confounders, ensuring a more precise understanding of the relationship between endometriosis and migraine.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the World Endometriosis Society for supporting an international network through the mentorship program.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- COCP

Combined oral contraceptive pill

- DIE

Deep infiltrating endometriosis

- GWAS

Genome-Wide Association Study

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- ICD

International Classification of Disease

- HIS

International Headache Society

- MeSH

Medical subject headings

- OMA

Ovarian endometrioma

- OR

Odds ratio

- POP

Progesterone-only pill

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- rASRM

Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine

- ROBINS-E

The Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Exposure

- SUP

Superficial peritoneal endometriosis

Author contributions

GEC was involved in study design, search strategy, study selection, data extraction, data interpretation, risk of bias and study quality assessment, and drafting of the manuscript. SM was involved in study design, study selection, data extraction, data interpretation, risk of bias and study quality assessment, and editing of the manuscript. ES was involved in study design and editing of the manuscript. GS was involved in statistical analysis and editing of the manuscript. BL was involved in study design, data interpretation, and editing of the manuscript. CP was involved in study design, data interpretation, and editing of the manuscript. NS was involved in study design, data interpretation, drafting of the manuscript. DRK was involved in study design, statistical analysis, data interpretation, and editing of the manuscript. PV was involved in study inception, study design, data interpretation, editing of the manuscript, and study supervision.

Funding

This study is partially supported by Italian Ministry of Health – Current research IRCCS.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dimitrios Rafail Kalaitzopoulos and Paola Vigano’ contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Giorgia Elisabeth Colombo, Email: giorgiaecolombo@gmail.com.

Paola Vigano’, Email: paola.vigano@policlinico.mi.it.

References

- 1.Fauconnier A, Chapron C, Dubuisson JB et al (2002) Relation between pain symptoms and the anatomic location of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertil Steril 78:719–726. 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03331-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowlands IJ, Abbott JA, Montgomery GW et al (2021) Prevalence and incidence of endometriosis in Australian women: a data linkage cohort study. BJOG 128:657–665. 10.1111/1471-0528.16447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenabi E, Khazaei S (2020) Endometriosis and migraine headache risk: a meta-analysis. Women Health 60:939–945. 10.1080/03630242.2020.1779905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tietjen GE, Conway A, Utley C et al (2006) Migraine is associated with menorrhagia and endometriosis. Headache 46:422–428. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller JA, Missmer SA, Sc D et al (2018) Prevalence of migraines in adolescents with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 109:685–690. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang MH, Wang PH, Wang SJ et al (2012) Women with endometriosis are more likely to suffer from migraines: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 7:12–16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrero S, Pretta S, Bertoldi S et al (2004) Increased frequency of migraine among women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 19:2927–2932. 10.1093/humrep/deh537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller JA, Missmer SA, Sc D et al (2016) Prevalence of migraines in adolescents with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 109:685–690. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashina M, Katsarava Z, Do TP et al (2021) Migraine: epidemiology and systems of care. Lancet 397:1485–1495. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32160-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maitrot-Mantelet L, Hugon-Rodin J, Vatel M et al (2020) Migraine in relation with endometriosis phenotypes: results from a French case-control study. Cephalalgia 40:606–613. 10.1177/0333102419893965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P et al (2011) Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril 96:366–373e8. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD, Tijhuis M et al (2000) The impact of migraine on quality of life in the general population. Neurology 55:624–629. 10.1212/WNL.55.5.624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adewuyi EO, Sapkota Y, Auta A et al (2020) Shared molecular genetic mechanisms underlie endometriosis and migraine comorbidity. Genes (Basel) 11:1–26. 10.3390/genes11030268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahmioglu N, Mortlock S, Ghiasi M et al (2023) The genetic basis of endometriosis and comorbidity with other pain and inflammatory conditions [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Nyholt DR, Gillespie NG, Merikangas KR et al (2009) Common genetic influences underlie comorbidity of migraine and endometriosis. Genet Epidemiol 33:105–113. 10.1002/gepi.20361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML et al (2002) High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod 17:2715–2724. 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peres MFP, Zukerman E, Young WB et al (2002) Fatigue in chronic migraine patients. Cephalalgia 22:720–724. 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ifergane G, Buskila D, Simiseshvely N et al (2006) Prevalence of fibromyalgia syndrome in migraine patients. Cephalalgia 26:451–456. 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01060.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biscetti L, De Vanna G, Cresta E et al (2021) Headache and immunological/autoimmune disorders: a comprehensive review of available epidemiological evidence with insights on potential underlying mechanisms. J Neuroinflammation 18:1–28. 10.1186/s12974-021-02229-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramin-Wright A, Schwartz ASK, Geraedts K et al (2018) Fatigue – a symptom in endometriosis. Hum Reprod 33:1459–1465. 10.1093/humrep/dey115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anne MacGregor E (2004) Oestrogen and attacks of migraine with and without aura. Lancet Neurol 3:354–361. 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00768-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raffaelli B, Do TP, Chaudhry BA et al (2023) Menstrual migraine is caused by Estrogen withdrawal: revisiting the evidence. J Headache Pain 24:1–10. 10.1186/s10194-023-01664-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement David Moher and colleagues introduce PRISMA, an update of the QUOROM guidelines for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Source BMJ: Br Med J 2535:332–33623. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiologya proposal for reporting. JAMA 283:2008–2012. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor HS, Adamson GD, Diamond MP et al (2018) An evidence-based approach to assessing surgical versus clinical diagnosis of symptomatic endometriosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet 142:131–142. 10.1002/ijgo.12521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) (2018);38:1–211. 10.1177/0333102417738202 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis (1996) Fertil Steril. 1997;67:817–21. 10.5363/tits.21.6_102 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.(ROBINS-E Development Group, Higgins J, Morgan R, Rooney A, Taylor K, Thayer K, Silva R, Lemeris C, Akl A, Arroyave W, Bateson T, Berkman N, Demers P, Forastiere F, Glenn B, Hróbjartsson A, Kirrane E, LaKind J, Luben T, Lunn R, McAleenan A, McGuinness L M SJ. Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Exposure (ROBINS-E).

- 29.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al (2008) GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ.;336:924 LP – 926. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G et al (2013) GRADE handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendation. https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html

- 31.Higgins J, Green S, GRADEpro GDT (2011) GRADEpro guideline development [software]ool [Software]. The Cochrane Collaboration

- 32.DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7:177–188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21:1539–1558. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M et al (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ.;315:629 LP – 634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Center CTNC (2014) Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.3

- 36.Mirkin D, Murphy-Barron C, Iwasaki K (2007) Actuarial analysis of private payer administrative. Health (San Francisco) 13:262–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gete DG, Doust J, Mortlock S et al (2023) Associations between endometriosis and common symptoms: findings from the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Am J Obstet Gynecol 229:536. e1-536.e20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sultana S, Chowdhury TA, Chowdhury TS et al (2024) Migraine among women with endometriosis: a hospital-based case-control study in Bangladesh. AJOG Global Rep 4:100344. 10.1016/j.xagr.2024.100344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karamustafaoglu Balci B, Kabakci Z, Guzey DY et al (2019) Association between endometriosis, headache, and migraine. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord 11:19–24. 10.1177/2284026518818975 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stratton P, Khachikyan I, Sinaii N et al (2015) Association of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis with signs of sensitization and myofascial pain. Obstet Gynecol.;125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Tietjen GE, Bushnell CD, Herial NA et al (2007) Endometriosis is associated with prevalence of comorbid conditions in migraine. Headache: J Head Face Pain 47:1069–1078. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00784.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu CC, Chung SD, Lin HC (2018) Endometriosis increased the risk of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis: A population-based study. Neurourol Urodyn 37:1413–1418. 10.1002/nau.23462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Y, Wang H, Chen S et al (2022) Migraine is more prevalent in Advanced-Stage endometriosis, especially when Co-Occuring with adenomoysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 12:1–9. 10.3389/fendo.2021.814474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anne MacGregor E, Hackshaw A, Bartholomew S (2004) Prevalence of migraine on each day of the natural menstrual cycle from the City of London migraine clinic and departments of gynaecology and sexual health. (Dr;351–353 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Vetvik KG, Benth JŠ, MacGregor EA et al (2015) Menstrual versus non-menstrual attacks of migraine without aura in women with and without menstrual migraine. Cephalalgia 35:1261–1268. 10.1177/0333102415575723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin VT, Behbehani M (2006) Ovarian hormones and migraine headache: Understanding mechanisms and pathogenesis - Part 2. Headache 46:365–386. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin VT, Wernke S, Mandell K et al (2005) Defining the relationship between ovarian hormones and migraine headache. Headache 45:1190–1201. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.00242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pavlović JM, Allshouse AA, Santoro NF et al (2016) Sex hormones in women with and without migraine. Neurology.;87:49 LP – 56. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Martin VT, Pavlovic J, Fanning KM et al (2016) Perimenopause and menopause are associated with high frequency headache in women with migraine: results of the American migraine prevalence and prevention study. Headache 56:292–305. 10.1111/head.12763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burger HG, Hale GE, Dennerstein L et al (2008) Cycle and hormone changes during perimenopause: the key role of ovarian function. Menopause 15:603–612. 10.1097/gme.0b013e318174ea4d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E et al (2014) Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10:261–275. 10.1038/nrendo.2013.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nappi RE, Terreno E, Sances G et al (2013) Effect of a contraceptive pill containing estradiol valerate and dienogest (E2V/DNG) in women with menstrually-related migraine (MRM). Contraception 88:369–375. 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morotti M, Remorgida V, Venturini PL et al (2014) Progestogen-only contraceptive pill compared with combined oral contraceptive in the treatment of pain symptoms caused by endometriosis in patients with migraine without aura. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reproductive Biology 179:63–68. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saunders PTK, Horne AW, Endometriosis (2021) Etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell 184:2807–2824. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shigesi N, Kvaskoff M, Kirtley S et al (2019) The association between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 25:486–503. 10.1093/humupd/dmz014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tulandi T, Vercellini P (2024) Growing evidence that endometriosis is a systemic disease. Reprod Biomed Online 49:104292. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2024.104292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levy D, Burstein R, Strassman AM (2006) Mast cell involvement in the pathophysiology of migraine headache: A hypothesis. Headache 46. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00485.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Geng C, Yang Z, Xu P et al (2022) Aberrations in peripheral inflammatory cytokine levels in migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci 98:213–218. 10.1016/j.jocn.2022.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fitzcharles M-A, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ et al (2021) Nociplastic pain: towards an Understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet 397:2098–2110. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00392-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bartley EJ, Alappattu MJ, Manko K et al (2024) Presence of endometriosis and chronic overlapping pain conditions negatively impacts the pain experience in women with chronic pelvic–abdominal pain: A cross-sectional survey. Women’s Health 20:17455057241248016. 10.1177/17455057241248017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.