ABSTRACT

Inflammation is associated with a wide range of medical conditions, most leading causes of death, and high healthcare costs. It can thus benefit from new insights. Here we extended previous studies and found that oxidation of human native mtRNA to ‘mitoxRNA’ strongly potentiated IFNβ and TNFα immunostimulation in human cells, and that this newly identified type 1 interferon potentiation was transcriptional. This potentiation was significantly greater than with mtDNA oxidation, and t-butylhydroperoxide (tBHP) oxidation of RNA was more proinflammatory than hydrogen peroxide (HP). mtRNA triggered a modest increase in apoptosis that was not potentiated by oxidation, and mtDNA triggered a much greater increase. For native mtRNA, we found that chloroquine-inhibitable endosomes and MDA5 are key signaling pathways for IFNβ and TNFα production. For mitoxRNAs, RNAseq revealed a major increase in both tBHP- and HP-mitoxRNA modulated genes compared with native mtRNA. This increase was very prominent for interferon-related genes, identifying them as important mediators of this powerful oxidation effect. Moderately different gene modulations and KEGG pathways were observed for tBHP- versus HP-mitoxRNAs. These studies reveal the profound effect that mitochondrial RNA oxidation has on immunostimulation, providing new insights into DAMP inflammation and identifying potential therapeutic targets to minimize DAMP mtRNA/mitoxRNA-mediated inflammation.

KEYWORDS: Mitochondria, oxidative stress, T-butylhydroperoxide, hydrogen peroxide, type 1 interferons, proinflammatory cytokines, human, immunostimulation

1. Introduction

Inflammation is associated with a wide range of medical conditions. These include rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune diseases, asthma, obesity, cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis, diabetes, osteoporosis, hepatitis, endocarditis, bronchitis, gingivitis, certain cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and many more [1,2]. It is considered to be the major driver of most leading causes of death worldwide today [1,2]. Predictably inflammation, especially chronic inflammation, has high associated costs [1,2]. Thus, new insights into better understanding the inflammatory process are of major health importance toward identifying new therapeutic targets.

We study inflammation with an emphasis on mitochondrial RNA (mtRNA) and DNA (mtDNA) and their oxidation [3–7]. These are examples of damage-associated molecular patterns or ‘DAMPs’. DAMPs are native molecules released from damaged and dying mammalian cells. This release triggers a danger response from DAMP interaction with various cellular ‘pattern recognition’ receptors such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) in turn inducing release of various proinflammatory cytokines and immunomodulators [8–10]. DAMPs represent a diverse range of cellular molecules, most notably HMGB1 protein, S100 protein, heat shock protein, and mitochondrial DNA, but others as well. Mitochondrial molecules including DNA and RNA are prominent DAMPs as their unintended release into the cytoplasm and extracellular spaces (including blood) deceives the body into thinking that a bacterial or viral infection is taking place. We and others have shown that this leads to increased release of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNFα as well as type 1 interferons such as IFNβ [3–5,10–12], a different class of inflammation-associated cytokine. To date, significantly less is known about the proinflammatory effects of mtRNA than mtDNA.

We have also reported that mtRNA- and mtDNA-oxidation typically enhances or ‘immunostimulates’ proinflammatory responses [3–5] although this immune modulation can also reduce cytokine release in mice cells [4]. These observations strongly suggest that oxidized mtRNA and mtDNA, which we designate mitoxRNA and mitoxDNA respectively, play a major role in controlling inflammation. However, only a modest amount is known about this oxidation effect for mitochondrial RNA.

In this paper, we extend our previous studies to better understand the important role that oxidized (mitoxRNA) and native (mtRNA) mitochondrial RNA DAMPs play in inflammation. This includes the first assessment of oxidation of mitoxRNA on a different class of cytokine, type 1 interferon, beyond our previously analyzed proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNFα and IL1β); assessing the role of transcription in this immunostimulation; comparing the potentiation of immunostimulation and apoptosis between mitoxRNA and mitoxDNA; comparing the immunostimulatory effects of tBHP- versus HP-oxidized mitoxRNA; and identifying key mediators and potential human therapeutic targets to minimize DAMP mtRNA/mitoxRNA-mediated inflammation using specific pathway inhibitors as well as RNAseq.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell cultures and oxidant treatments

The human monocyte THP-1 cell line was cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). These cells were then differentiated into macrophages by addition of 100 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) to a 600,000 cells/ml suspension and transfer to multi-well plates for 3 days leading to a monolayer phenotype switch and confluence of approximately 75%. THP1-Dual cells were cultured in the same media additionally supplemented with 25 mM HEPES. HeLa epithelial-like human cells were cultured in DMEM media containing 10% fetal bovine serum and the same above penicillin/streptomycin. All cell lines were incubated in a humidified incubator atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C. THP-1 cells were obtained from Dr. Jon Harton (Albany Medical College). THP1-Dual cells were obtained from Invivogen (San Diego, CA). HeLa cells were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD).

2.2. Subcellular fractionation isolation of mitochondria and cytoplasm

HeLa epithelial-like cells or THP-1 monocytes were incubated for two hours with different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide or t-butylhydroperoxide (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO) or solvent-only control (phosphate-buffered saline; PBS). Cells were then collected and centrifuged, washed once with PBS, and resuspended in isotonic 0.25 M sucrose containing 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4 and 1 mM EDTA. Each preparation was Dounce homogenized and spun 5 min at 1200 × g at 4°C to remove nuclei and unbroken cells. Supernatant were collected and respun under the same conditions. The subsequent supernatants were centrifuged 14 min at 14,000 × g, and supernatants from this spin collected and respun. These supernatants were then saved as the cytoplasmic fraction. The pellets, representing the mitochondrial fraction, were rinsed and centrifuged again. The pellets were then resuspended in the above sucrose buffer, layered onto 1 ml of 1 M sucrose in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4 plus 5 mM EDTA, and spun 20 min at 12,000 × g at 4°C to minimize contaminating membranes. The resultant mitochondrial pellet was then resuspended in a small volume.

2.3. Western blot analyses

For purity assessment, the above mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions were electrophoresed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted to nitrocellulose. This was followed by membrane incubation with primary antibody (rabbit polyclonal VDAC as a mitochondrial marker from Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, and mouse monoclonal alpha tubulin as a cytoplasmic marker from Sigma), washes, horse radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody addition, washes, and signal development using Western Lightning Pus-ECL from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA). For below MDA5 Western blots, rabbit monoclonal antibody from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) was used.

2.4. Isolation of RNA

Mitochondrial fraction RNA and DNA and cytoplasmic fraction RNA were extracted using the AllPrep DNA/RNA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) including the optional DNase step for RNA isolation.

2.5. Transfections

Native mtRNA and mitoxRNA; Invivogen positive controls ssRNA40, poly(I:C) and Poly dA:dT; and no nucleic acid (‘Mock’ transfection) controls were transfected into PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages or THP1-Dual cells in 96-well culture plates using Lipofectamine MessengerMAX according to the manufacturer (Thermo Fisher, Agawam, MA). Twenty hours later, cell culture medias were collected for cytokine analyses (THP-1 cells) or chemiluminescent signal (Dual cells). Agonist immunostimulations were determined by comparison with mock transfections. For RNase pretreatments, separate reaction tubes of mitoxRNA were first preincubated with and without the RNA single-strand degrading enzyme RNase A (Thermo Fisher) using the same reaction buffer and the same done for the RNA double-strand degrading ShortCut RNase III (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) according to the manufacturers and prior to transfection. A no RNA, no enzyme control was also included and for RNase A, 350 mM NaCl was added to insure single strand-specific cutting.

2.6. THP-1 cell cytokine analysis

For THP-1 cell studies, human proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNFα as well as IFNβ were analyzed in cell culture media using the BioPlex Multiplex immunoassay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioRad, Hercules, CA) with analysis carried out in the Albany Medical College Department of Immunology core facility. Cytokine levels were quantified by interpolation from a standard curve for each cytokine.

2.7. THP1-dual cell transcriptional analysis

Type 1 interferon transcription was assessed using the THP1-Dual interferon response element reporter gene cell line according to the manufacturer (Invivogen). Luminescent signals were read using the BioTek Cytation 7 multimode reader (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

2.8. Apoptosis analyses

Transfected cells were assessed for apoptosis using the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit according to the manufacturer (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) using a FACSymphony A3 flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) with FlowJo software, version 10.10.0. Results were expressed as the percentage of cells counted within a debris exclusion gate. Positive controls included the proapoptotic agent Camptothecin (5 µM for 6 h or overnight) and the double-strand RNA mimic poly(I:C) (Invivogen, San Diego, CA).

2.9. Assessment of MDA5, RIG-I and chloroquine-inhibitable endosomes in immunostimulation

THP-1 cells were separately transfected with final 16 nM siRNAs to MDA-5 and RIG-I for 28 h. Additionally, other cultures were exposed to 30 µM chloroquine (CQ) for 60 min. Cells were then transfected with native HeLa mtRNA and TNFα and IFNβ immunostimulation assessed as above.

2.10. RNA sequencing

Total cellular RNAs purified with the AllPrep DNA/RNA kit as above were submitted to Azenta (South Plainfield, NJ) for RNA sequencing (RNAseq). These RNAs were prepared following THP-1 cell mock, native mtRNA, tBHP mitoxRNA and HP mitoxRNA transfections, each in quadruplicate except native mtRNA triplicate. RIN analyses were carried out on both the HeLa RNAs before transfection and the THP-1 RNAs following transfection and all met with the ≥ 6.0 requirement. rRNA depletion was performed using the FastSelect rRNA Bacteria Kit (Qiagen). RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Preparation Kit for Illumina per the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). Samples were sequenced using a 2 × 150 bp Paired End (PE) configuration. Image analysis and base calling were conducted by the NovaSeq Control Software. Raw sequence data (.bcl files) generated from Illumina NovaSeq was converted into fastq files and de-multiplexed using Illumina bcl2fastq 2.20 software.

2.11. RNAseq analysis

The RNAseq data was processed and analyzed for differential expression using R (version 4.4.0). The code used for the analysis is available upon request. For read alignment, paired-end RNAseq reads were mapped to the human genome (hg38) using the align function from the Rsubread package (version 1.5.3) [13]. Gene annotation, including gene symbols and names, was performed using the org.Hs.eg.db package. Quality control included checks for library size, log-transformed count distributions, and the generation of multidimensional scaling (MDS) plots. For differential expression analysis, the limma-voom approach was employed. Linear models were fitted to the gene expression data using the lmFit function. The eBayes function was used to apply empirical Bayes moderation, improving the estimates of variance.

2.12. RNAseq pathway analysis

For gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), we used the WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt) as described [14] with the Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) method. The analysis was performed for the organism Homo sapiens (hsapiens). Enrichment categories included non-redundant biological processes (geneontology_Biological_Process_noRedundant) and molecular functions (geneontology_Molecular_Function_noRedundant) from Gene Ontology (GO). Additionally, pathway analysis was conducted using KEGG (pathway_KEGG) and Panther (pathway_Panther) databases.

2.13. Statistics

Data is expressed as the mean ± SEM. For cytokine, polynucleotide oxidation state and polyphenol administration comparisons, statistics were carried out using the Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was concluded when p ≤ .05 for any comparison. To normalize the data for RNAseq analysis and account for differences in library sizes and composition, normalization factors were computed using the calcNormFactors function from edgeR, applying the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) method. For differential expression analysis, the limma-voom statistical method was used with the voom function used to apply a variance-stabilizing transformation and generate observation-level weights based on the mean-variance relationship of log-counts.

3. Results

3.1. Immunostimulation of THP-1 cell IFNβ and proinflammatory cytokines with oxidized mtRNA

Our previous studies reported that mtRNA from different species including human immunostimulate proinflammatory cytokine induction, and that mtRNA oxidation can increase or decrease (in mice) this effect [3–5]. We also observed that mitochondrial RNA induces the expression of another key immune cytokine class, type 1 interferons, in mouse primary bone marrow derived macrophages using interferon beta (IFNβ) as a marker [4]. However, the effect of human mtRNA oxidation (mitoxRNA) on human type 1 interferon immunostimulation has not yet been assessed. Given the importance of type 1 interferons in inflammation, autoimmune disease, type 1 interferonopathies and other disorders [15–17], assessing the effect of oxidation of human mitochondrial polynucleotides has potential major clinical implications. Here we extend our previous studies to human using both t-butylhydroperoxide (tBHP) and hydrogen peroxide (HP) as oxidants. These provide some diversity of action as tBHP is an organic peroxide that is more lipid (and so membrane) soluble than hydrogen peroxide [18–20]. As such, these studies are also the first to ever report the use of tBHP to assess and compare the effect of oxidized mtRNA on the release of any cytokine.

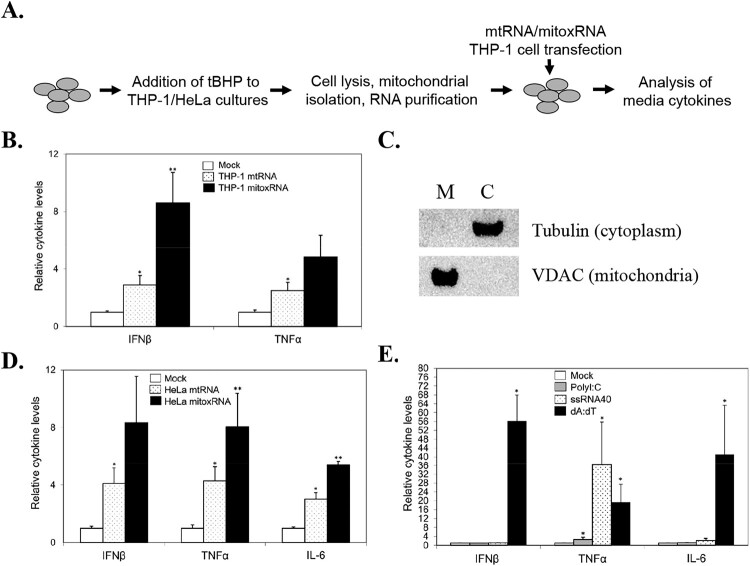

Our general experimental strategy is shown in Figure 1(a). Using successfully fractionated THP-1 cell mitochondria as previously reported [5], transfection of human THP-1 cell native mtRNA into the same cell type induced IFNβ release 2.9-fold (and TNFα 2.5-fold) above mock transfected (Figure 1b). Parallel analysis with tBHP-oxidized mitoxRNA led to a significantly greater 8.6-fold induction of IFNβ above mock transfected, and a full 3.0-fold greater induction than for the native mtRNA. Additionally, a twofold potentiation of induction of TNFα was also observed. Thus, oxidation (in this case, with tBHP) of mtRNA potentiates mtRNA immunostimulation of type 1 IFNβ and TNFα. This is the first such demonstration of mitoxRNA potentiation of human IFNβ levels.

Figure 1.

Immunostimulation of THP-1 cell IFNβ and proinflammatory cytokines with oxidized mtRNA. (a) General experimental strategy. (b) THP-1 cell native mtRNA and mitoxRNA induction of cytokines in THP-1 cells 20 h after transfection (N = 8). (c) Subcellular fraction analysis by Western immunoblotting using antibodies to the mitochondrial marker VDAC and the cytoplasmic marker alpha tubulin. M, mitochondrial fraction; C, cytoplasmic fraction. (d) HeLa cell native mtRNA and mitoxRNA induction of cytokines in THP-1 cells 20 h after transfection (N = 3–6). (e) Positive control ligand (polyI:C, ssRNA40, and dA:dT) induction of cytokines in THP-1 cells 20 h after transfection (N = 3–7). Mock transfection values were normalized to 1.0. Values represent means ± SEM. *, significant difference compared with Mock transfection using the Student’s t-test at p < .05. **, significant difference between native mtRNA and mitoxRNA.

We then assessed another human mtRNA source (HeLa cells) to see if the transfection immunostimulations were similar, as expected, using the same THP-1 recipient cells. Similar to what we observed for THP-1 human as well as hamster and mouse cells [4], our subcellular fractionation of HeLa cells revealed a clean mitochondrial fraction free of cytoplasmic contamination using markers for mitochondria (VDAC) and cytoplasm (alpha tubulin) (Figure 1c). Using these purified fractions, we observed that native (HeLa cell) mtRNA significantly induced both IFNβ and TNFα (4.1 and 4.3-fold, respectively), and these inductions were also well potentiated by tBHP RNA oxidation (to 8.3 and 8.1-fold, respectively) (Figure 1d), similar to what we observed using THP-1 mtRNA and mitoxRNA (Figure 1b). We also assessed another proinflammatory cytokine here, IL-6, and saw a similar induction trend (3.0-fold for mtRNA, and 5.4-fold for mitoxRNA). These results confirm that a different source of human mitochondrial RNA immunostimulates to a similar extent using a cell type (HeLa) that other investigators have also used to study RNA immunostimulation [21–23].

Toward better understanding THP-1 cytokine production capability and mtRNA/mitoxRNA data interpretation including mitochondrial RNA-stimulated pathways, we also assessed positive control ligand stimulation of the above cytokines. These positive controls included poly(I:C), a double-strand RNA positive control able to act through TLR3 but presumed to act through the intracellular MAVS pathway when transfected; the single-strand RNA ligand ssRNA40, which acts through TLR 7 and TLR8; and dA:dT, a repetitive polyAT analog of double-stranded DNA recognized by multiple receptors including those for intracellular double stranded RNA following RNA polymerase III activity (the later known for its production of type I interferons); [24]. A variety of results were observed depending upon the agonist (Figure 1e). Relative to our IFNβ focus here, transfected poly(I:C) showed no immunostimulation and was only weakly inductive of TNFα but not IL-6, in contrast to the significantly greater immunostimulatory activity observed for both mtRNA and especially mitoxRNA from THP-1 and Hela cells (Figure 1b,d). ssRNA40 showed a surprisingly selective TNFα stimulation. Conversely, dA:dT was an effective immunostimulant of all three tested cytokines. These results suggest that in these transfected THP-1 cells, authentic mitochondrial RNA is a far more efficient immunostimulant than poly(I:C), which is known to be an efficient cytokine inducer in some other cells [25–27]; that TLR 7/8 (ssRNA40 target) is mainly relevant to TNFα induction; and that intracellular RNA produced from dA:dT is highly effective, in turn suggesting an overlapping mechanism of induction to what we observe with our mitochondrial RNAs.

3.2. Type 1 interferon induction by mitoxRNA is transcriptionally mediated in THP-1 dual cells

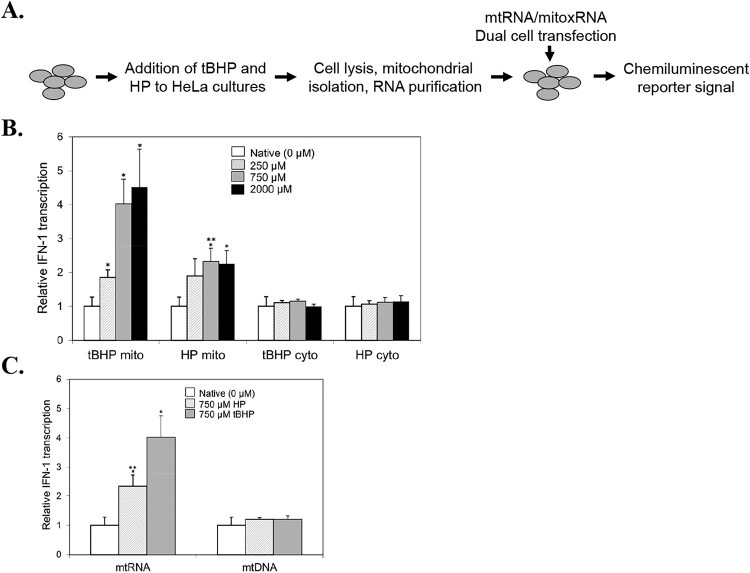

To gain additional insight and potentially identify new therapeutic targets, we used a THP1 type 1 interferon response element reporter gene cell line to assess the immunostimulatory effect of human mtRNA oxidation (mitoxRNA) on type 1 interferon (IFN-1) induction in more detail (transcriptional). These ‘Dual cells’ contain a luciferase reporter gene construct with five interferon-stimulated transcriptional response elements. Our new experimental strategy focusing on Dual cells is shown in Figure 2(a). Transfection of these cells with both HeLa native mtRNA and mitoxRNA prepared using 250 µM tBHP led to IFN-1 transcriptional induction, with the mitoxRNA exhibiting a 1.9-fold induction greater than native mtRNA (Figure 2b). Even greater induction was observed with 750 µM tBHP-generated mitoxRNA as compared with native mtRNA (4.0-fold induction) (Figure 2b). These results demonstrate for the first time that oxidized mitoxRNA significantly potentiates native mtRNA-induced IFN-1 transcription, and also support the conclusion that the potentiation of IFN-1 immunostimulation by mitochondrial RNA oxidation observed in Figure 1(b,d) is mainly if not totally due to transcriptional induction. As part of these analyses, we also assessed the effect of double strand-degrading RNase III and single stand-degrading RNase A pretreatment on 750 tBHP mitoxRNA transcriptional induction. Per total RNase inhibition, we observed 73.1% inhibition of immunostimulation with RNase III (down to 26.9 ± 12.0 SEM of the total RNase-inhibitable activity; N = 5) and 26.9% inhibition with RNase A (down to 73.1 ± 17.3 SEM of the total RNase-inhibitable activity; N = 6), indicating that mitoxRNA IFN-1 transcriptional immunostimulation is due to both structural forms and mainly double-stranded RNA.

Figure 2.

Type 1 interferon (IFN-1) immunostimulation at the transcriptional level using Dual cells. (a) General experimental strategy. (b) Dual cell native mtRNA and mitoxRNA IFN-1 interferon transcription 20 h after transfection (N = 3–10). Mito, mitochondrial fraction; cyto, cytoplasmic fraction. (c) Comparison of Dual cell mitoxRNA versus mitoxDNA induction of IFN-1 transcription 20 h after transfection using 750 µM tBHP and 750 µM HP (N = 6–10). Mock transfection values were normalized to 1.0. Values represent means ± SEM. *, significant difference compared with Native using the Student’s t-test at p < .05. **, significant difference comparing 750 µM tBHP mitoxRNA with 750 µM HP mitoxRNA using the Student’s t-test at p < .05.

In addition, we compared mitochondrial RNA oxidation by tBHP with hydrogen peroxide (HP) relative to immunostimulation. We observed that mitoxRNA obtained from HeLa cells treated with a 250 and 750 µM bolus of hydrogen peroxide exhibited a 1.9- and 2.3-fold potentiation, respectively, of IFN-1 induction over native mtRNA (Figure 2b). These results demonstrate that HP oxidation of RNA also leads to a significant immunostimulation although significantly less than what was observed with tBHP mitoxRNA at 750 µM.

3.3. IFN-1 transcriptional induction by mitoxRNA is not attenuated at higher oxidation

We previously reported that greater oxidation of rodent mtRNA leads to a reduction (rather than induction) of IFN-1, TNFα and IL-6 protein release in mouse cells but not with a lesser oxidized human mitochondrial RNA [4,5]. To evaluate this more fully in human cells, we assessed IFN-1 induction in Dual cells using a maximally attainable tBHP concentration; i.e. a concentration high enough to generate cytotoxicity but still able to provide a mitochondrial fraction and RNA yield comparable to native mitochondria (2000 µM). As shown in Figure 2(b), even at this highest tBHP and HP concentration, immunostimulation of IFN-1 was still observed, and at almost the same extent as that observed using 750 µM oxidant. Thus, unlike rodent cell mtRNA, human mitoxRNA obtained using higher oxidant concentration does not attenuate immunostimulation in these human cells.

As part of these studies, we assessed cytoplasmic RNA (cytoRNA) immunostimulation of IFN-1 transcription in the Dual THP-1 cells obtained from the same experiments presented in Figure 2(b), left side. No significant immunostimulation was observed with the oxidized cytoRNAs as compared with native cytoRNAs (Figure 2b, right side). These results are similar to what we previously reported for IL-6 and TNFα release from parental THP-1 cells [5]. It should be noted that while the Figure 2 data is normalized to 1.0 for native mtRNA to clearly illustrate fold-changes induced by mitoxRNA, the actual raw mtRNA and mitoxRNA signals far exceeded those for cytoRNAs.

For perspective, we compared the above mitoxRNA potentiations with that for mtDNA oxidation. Here we observed that mtRNA oxidation had a much more profound effect on transcriptional immunostimulation, suggesting a more potent regulatory effect at the mtRNA level. These weak mitoxDNA cytokine potentiations might be unique to type 1 interferon and/or its transcription as we previously observed much greater increases in proinflammatory cytokine levels by mtDNA oxidation, albeit in mice [4].

We also extended Figure 1(e) agonist analyses to Dual cells using the most consistently immunostimulatory positive control dA:dT. Here we observed that this agonist stimulated IFN-1 transcription 63.0-fold. This value is nearly identical to what we saw for Figure 1(e) THP-1 parental cells assessing IFNβ release to the media following dA:dT transfection (56.3-fold). Thus, like tBHP-oxidized mitoxRNA immunostimulation, elevated IFNβ released from THP-1 parental cells after dA:dT transfection appears due to transcription.

3.4. mtRNA triggers a modest increase in apoptosis and this is not potentiated by oxidation

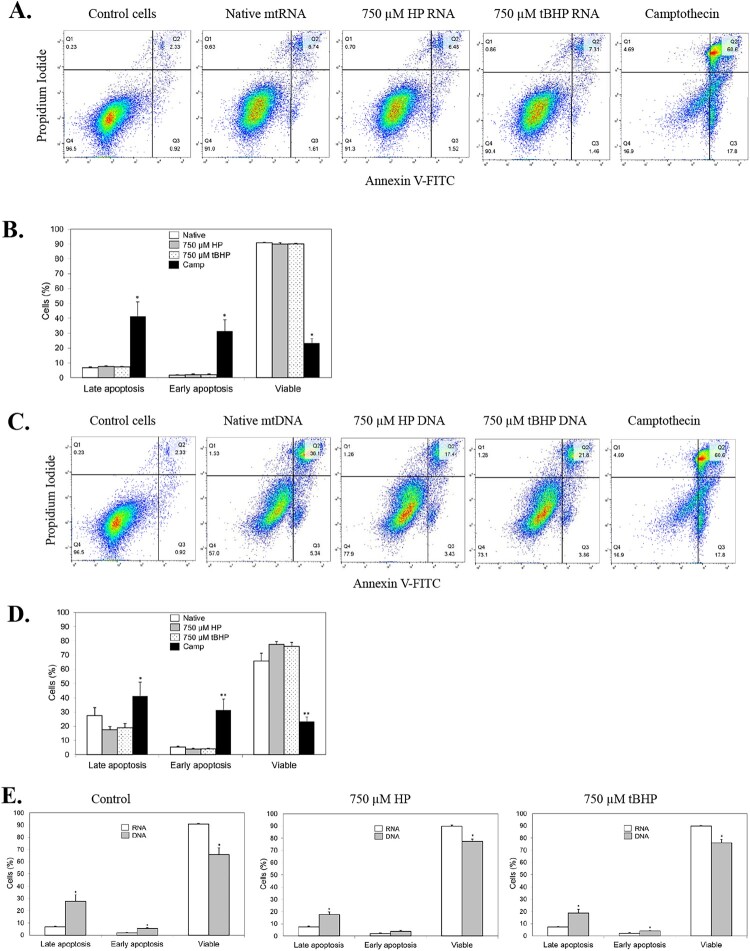

Our original studies on mtRNA oxidation revealed that oxidation of mammalian cells in cell culture led to mtRNA (and mtDNA) degradation and that this correlated with apoptosis [6]. Other studies have shown that introduction of poly I:C, a synthetic analog of double-stranded RNA used to mimic viral infection, can lead to increased apoptosis [23,25–27]. To assess the possible involvement of apoptosis in the cellular response to native and oxidized mtRNA release from mitochondria, we transfected the THP-1 Dual cells with these RNAs and assessed apoptosis using Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry detection. Here, Q1 (PI positive, Annexin negative) represents necrotic cells; Q2 (PI positive, Annexin positive) represent late (end stage) apoptosis or already dead cells; Q3 (PI negative, Annexin positive) represent cells undergoing early apoptosis; and P4 (PI negative, Annexin negative) represents viable cells not undergoing apoptosis. For our studies, we focused on Q2, Q3 and Q4 as the Q1 necrotic signals were consistently very low (<2%).

Transfection of mtRNA led to a modest 2.90-fold increase in the late apoptosis population and a 1.48-fold increase in the early apoptosis population when compared to control cells (Table 1 and Figure 3a). Importantly, this increase in apoptotic rate was not (statistically) potentiated when transfected native mtRNA was replaced with mitoxRNA, whether tBHP- or HP-generated. Predictably, a resultant small decrease in the viable cell population was also observed for all RNA transfections. The lack of statistical differences in mtRNA versus mitoxRNA transfections on apoptosis is further illustrated in Figure 3(b) where the absolute percent cell populations are plotted. For these analyses, the apoptosis positive control Camptothecin (Camp) is included.

Table 1.

The effect of mtRNA and mitoxRNA on late apoptotic, early apoptotic, and viable populations compared to control cells.

| Samples | Late apoptotic | Early apoptotic | Viable |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 µM | 2.90-fold | 2.07-fold | 0.94-fold |

| 750 µM HP | 3.19-fold | 2.32-fold | 0.93-fold |

| 750 µM tBHP | 3.12-fold | 2.39-fold | 0.93-fold |

Figure 3.

Effect of mtRNA and mitoxRNA on apoptosis of THP-1 cells. (a) Mitochondrial RNA-transfected cells were washed and resuspended and FITC Annexin and propidium iodide (PI) added, incubated, and analyzed by flow cytometry at 561 nm (PI) and 488 (FITC). The proapoptotic agent Camptothecin was used as a positive control. (b) Plotted data. (c) Mitochondrial DNA-transfected cells prepared and analyzed as above. (d) Plotted data for mitochondrial DNA. (e) Comparison of mtDNA and mitoxDNA effects on apoptosis. For (b, d) and (e) plotted data, the Y-axis ‘Cells (%)’ refers to each designated subpopulation as a percentage of total cells.

3.5. mtDNA triggers a much greater increase in apoptosis than mtRNA, and like mtRNA, this effect is not potentiated by oxidation

We also assessed the effect of native mtDNA and mitoxDNA and compared this with RNA. Transfection of mtDNA led to a much larger 11.82-fold increase in the late apoptosis population and a 7.50-fold increase in the early apoptosis population when compared to control cells (Table 2 and Figure 3c). Similar to RNA, this increase in apoptotic rate was not (statistically) potentiated when transfected native mtDNA was replaced with mitoxDNA, whether tBHP- or HP-generated (Figure 3d). Predictably, a counter decrease in the viable cell population was also observed for all DNA transfections. The differences in apoptosis following mitochondrial RNA versus DNA transfections are further illustrated in Figure 3(e) using absolute percent cell populations and comparing Q2, Q3 and Q4. To better understand the mechanism behind the increased mtDNA proapoptotic effects as compared with mtRNA, we looked to see if we could differentiate based on cell size (measured using forward scatter or FSC) and/or cell complexity or granularity (measured using side scatter or SSC). Here we gated the double-positive Q2 and double-negative Q4 signals from both treatments and graphed FSC and SSC. No (positional) differences were observed (Figure 4), suggesting that the increased proapoptotic mtDNA effect does not involve differences in cell size and/or granularity but rather is due to a similar mechanism as for mtRNA but at a greater magnitude. Combined, these results indicate that delivery of mitochondrial RNA to the cytoplasm leads to only a modest increase in cellular apoptosis that is significantly less than that observed for mitochondrial DNA. Additionally, these mitochondrial polynucleotide effects on apoptosis are not potentiated by oxidation.

Table 2.

The effect of mtDNA and mitoxDNA on late apoptotic, early apoptotic, and viable populations compared to control cells.

| Samples | Late apoptotic | Early apoptotic | Viable |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 µM | 11.82-fold | 6.02-fold | 0.68-fold |

| 750 µM HP | 7.50-fold | 4.23-fold | 0.80-fold |

| 750 µM tBHP | 8.06-fold | 4.47-fold | 0.79-fold |

Figure 4.

Comparison of mtDNA versus mitoxDNA forward and side-scatter. (a) Representative RNA analysis and (b) representative DNA analysis. Bottom panel shows Q2 and Q4 signals gated from both treatments and forward (FSC) and side-scatter (SSC) assessed.

3.6. MDA5 and chloroquine-inhibitable endosomes are key mediators of native mtRNA proinflammatory and type 1 interferon cytokine production

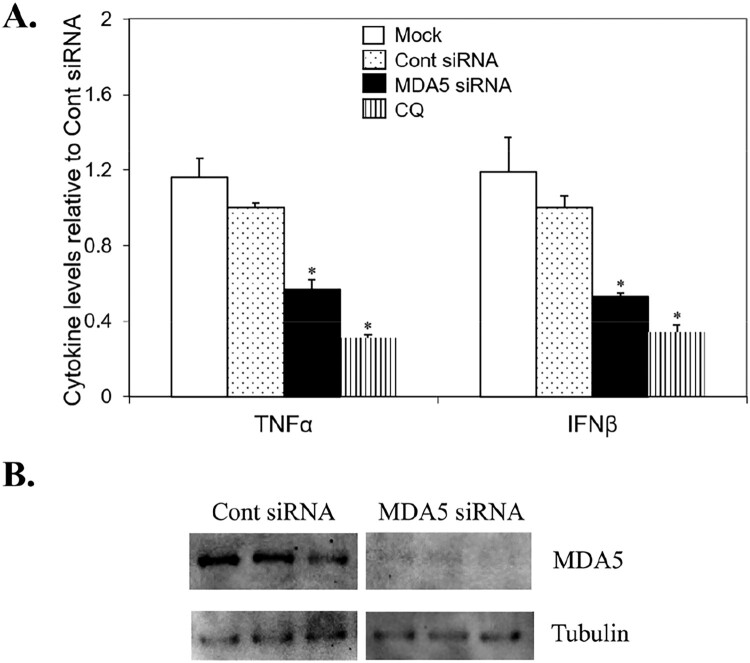

Toward determining the underlying mechanism(s) behind native mtRNA proinflammatory effects as well as identifying potential human therapeutic targets to minimize DAMP mtRNA/mitoxRNA-mediated inflammation, we assessed key known candidate mtRNA immunostimulation pathways (MDA5, RIG-I, TLR3, 7 and 8 for RNA) using final 16 nM siRNAs to MDA5 and RIG1, and 30 µM chloroquine (CQ), an inhibitor of TLR3,7,8,9 containing endosomes [28]. After 28 h siRNA and 60 min CQ pretreatment, THP-1 cells were transfected with native HeLa mtRNA as above. MDA5 siRNA (76% reduction; N = 3; Figure 5b) inhibited TNFα and IFNβ immunostimulation 43% and 47%, and CQ inhibited 69% and 66% (Figure 5a; N = 6, P < .05 for all inhibitions). Conversely, no RIG-I siRNA inhibition of immunostimulation was observed (N = 6). These results indicate that chloroquine-inhibitable endosomes and MDA5 are key native mtRNA signaling pathways for both proinflammatory (TNFα) and type 1 interferon (IFNβ) cytokine production.

Figure 5.

MDA5 and endosome in native mtRNA immunostimulation. (a) THP-1 cells were pretreated with siRNA or CQ followed by HeLa mtRNA transfection and TNFα/IFNβ analysis. Data means (N = 6) ± SEM. *, significant difference vs Cont siRNA, Students t-test at p < .05. (b) MDA5 knockdown Western blot.

3.7. Mitochondrial RNA oxidation triggers many more gene expression inductions, especially interferon-associated genes

Toward better understand the underlying mechanisms by which oxidized mitochondrial RNA (mitoxRNA) potentiates immunostimulation over native mtRNA, we carried out RNAseq analyses. These analyses also allowed us to compare tBHP- versus HP-oxidations for insight into why we observe differences in their comparative immunostimulations.

Comparing transfection control RNA (i.e. THP-1 cell RNA extracted following a mock no-RNA transfection) with native mtRNA transfection, RNAseq analyses identified 76 modulated genes using a log2 cutoff of 0.5 (equivalent to 1.41-fold or greater using an adjusted P-value less than 0.10). Conversely, comparison of the same transfection control with tBHP-oxidized mitoxRNA transfected cells revealed many more gene expression modulations (474) with less but a still significant number for HP (308). For all comparisons, the vast majority of modulations were inductions. The control RNA versus native mtRNA comparison revealed very few immune-related modulated genes (at this cutoff) with TNF the one notable exception. However, comparison of control with tBHP-oxidized mitoxRNA identified numerous immune-related modulated genes, most notably interferon-associated genes ranging from 1.6- to 13.5-fold (Table 3). Other induced immune genes of interest included TNF, IL8 (CXCL8), VCAM1, ICAM1, heme oxygenase (HMOX1). Comparison of control with HP-oxidized mitoxRNA also revealed induction of a significant number of interferon-associated genes (Table 3), although significantly less than that observed for tBHP-oxidized mitoxRNA, as well as other immune genes TNF, VCAM1, ICAM1, heme oxygenase and more. These HP-mitoxRNA interferon inductions ranged from 1.5- to 6.5-fold.

Table 3.

Relative number of IFN genes induced 1.41-fold or greater by mtRNA and mitoxRNA.

| Native mtRNA | tBHP-mitoxRNA | HP-mitoxRNA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN genes | Fold induction | IFN genes | Fold induction | IFN genes | Fold induction |

| (none) | IFNL1 IFIT1 IFIT3 IFNB1 IFI44L IFI27 IFI44 ISG20 OAS1 OASL IFIT5 IFI6 OAS3 IFITM1 OAS2 IRF7 IL4I1 IFIT2 IFI16 IFIH1 IFITM3 IFI35 BISPR IRF9 IFI27L1 IRF1 ADAR |

13.5 8.7 7.6 7.4 7.3 7.1 7.1 5.5 5.0 4.9 4.8 4.7 4.7 4.6 4.5 3.9 3.7 3.6 3.4 3.3 3.2 2.7 2.1 2.1 1.7 1.6 1.6 |

IFIT1 IFIT27 IFI44L IFI44 IFIT3 IFITM1 OAS3 IFI6 OAS1 OAS2 IRF7 IFITM3 IFI16 IFIH1 IFI35 BISPR IRF9 ADAR |

6.5 6.5 6.2 5.7 5.4 4.3 4.3 4.2 4.2 3.9 3.5 3.1 2.8 2.7 2.4 2.0 1.9 1.5 |

|

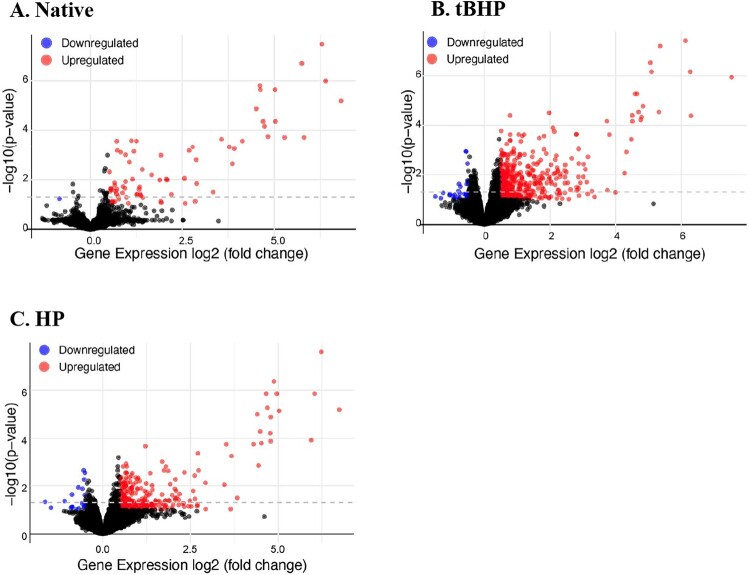

Of additional interest, the key genes for the antiviral MAVS pathway (RIG-I and MDA5) were also induced with both mitoxRNAs but not native mtRNA at the 1.41-fold and adjusted P-value less than 0.10 cutoff. Specifically, the mRNA for RIG-1 (RIGI) was induced 4.47- and 3.53-fold with tBHP and HP-mitoxRNA, respectively, and the mRNA for MDA5 (IFIH1) was induced 3.29- and 2.69-fold for tBHP and HP-mitoxRNA, respectively. These RNAseq data are summarized in Figure 6 where heatmaps of differentially expressed genes for the control versus native comparison (‘Native’), control versus tBHP mitoxRNA comparison (‘tBHP’ and ‘TB’), and control versus HP mitoxRNA comparison (‘HP’) are shown. They reveal a hierarchal clustering separation representative of robust mRNA expression changes and definite differences between native versus mitoxRNAs. Figure 7 Volcano plots underscore these significant differences with respect to number of modulated gene expressions, especially induced, for mitoxRNA when compared with native mtRNA.

Figure 6.

RNAseq heat maps. Hierarchal cluster heat maps for (a) Native, differentially expressed genes for mock- versus native mtRNA-transfected (76 modulated genes detected), (b) tBHP (TB), differentially expressed genes for mock- versus tBHP mitoxRNA-transfected (474 modulated genes), (c) HP, differentially expressed genes for mock- versus HP mitoxRNA-transfected (308 modulated genes). For above, (N = 3–4). Z-score scale bars based on Log2 FC are also shown. Blue, downregulated; red, upregulated.

Figure 7.

RNAseq volcano plots. Volcano plots comparing samples described in Figure 6.

When the log2 cutoff for the mock transfected control versus transfected native mtRNA comparison was lowered to the 1.2- to 1.3-fold induction range, a number of the above interferon-related gene transcripts were found to be elevated. Thus, introduction of native mtRNA into the cytoplasm of THP-1 cells induces numerous interferon-related genes but only modestly, and significantly less than the fold inductions observed for both tBHP and HP mitoxRNAs. Also of note was the induction of expression of many extracellular matrix (ECM)-associated genes for all groups including those transcripts that were most strongly induced. These included COL5A1, PXDN, KRT7, COL3A1 and COL4A5. Review of the literature indicates that this is the first report that mitochondrial RNA (whether native or oxidized) induces expression of this class of genes.

The major elevation in interferon-associated gene modulation with 750 µM tBHP mitoxRNA is consistent with the significant potentiation of type 1 interferon induction seen in our Dual reporter cells as well as the potentiation of IFNβ protein induction in Figure 1(b,d), with these results in effect acting as a confirmation of the RNAseq results. The lesser number of interferon-associated genes potentiation from 750 µM HP mitoxRNA transfection – while still much greater than native – is also consistent with the lesser amount of type 1 interferon-associated induction observed with HP mitoxRNA (Figure 2b,c). Importantly, these results reveal that interferon-associated gene inductions including IFNB1 itself are strongly potentiated by oxidation of the mitochondrial RNA. They also suggest that the RIG-I pathway plays an important role here for oxidized mitoxRNA, which was not the case for native mtRNA (Section 3.6).

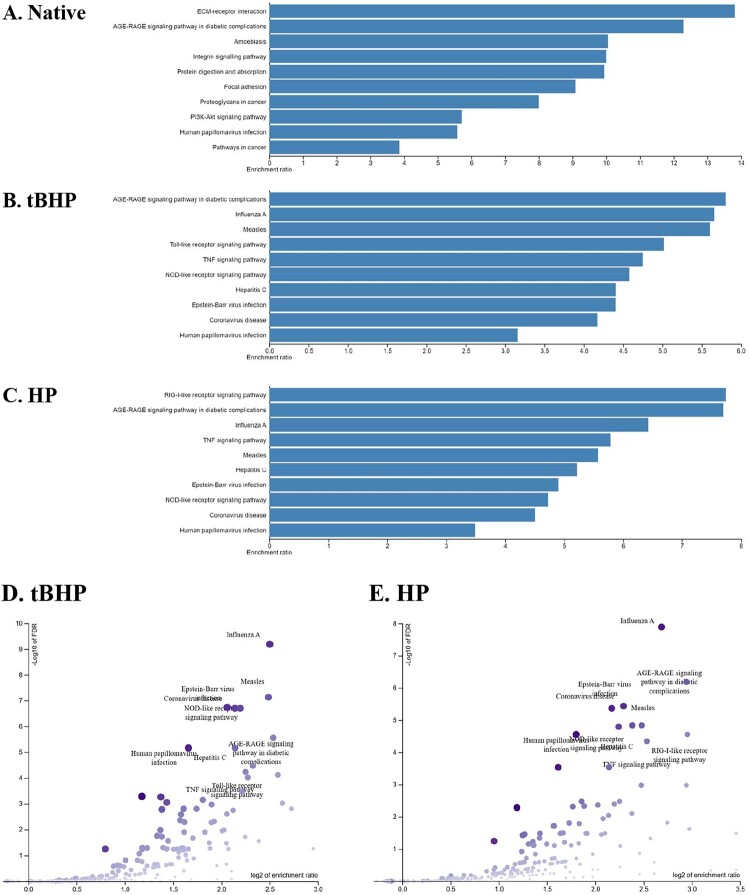

3.8. KEGG/PANTHER analysis and enrichment

To gain additional insight from our RNAseq analyses, we carried out KEGG/Panther pathway analyses. Figure 8 shows the order of subcategories under the ‘Biological Process’, ‘Cellular Component’ and ‘Molecular Function’ headings based on the number of associated modulated genes in response to Native mtRNA and the most robust oxidant trigger, tBHP mitoxRNA. It is immediately apparent that the order of these subcategory representations is significantly different for native mtRNA versus tBHP mitoxRNA (note: tBHP mitoxRNA and HP mitoxRNA subcategory orders were near identical; data not shown).

Figure 8.

GOSlim summary. GOSlim summary of genes differentially altered in (a) native mtRNA-transfected (‘Native’) cells, and (b) tBHP mitoxRNA-transfected (‘tBHP’) cells. Bar charts for Biological Process (red), Cellular Component (blue), and Molecular Function (green) categories are presented with bar heights representative of the number of genes observed in the category.

The top KEGG pathways and their enrichment order are shown in Figure 9 using the Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) method as described under Materials and Methods. Consistent with the large number of interferon-associated genes modulated by oxidized but not native RNA as described above, the mitoxRNA transfections stimulated numerous pathways associated with various viral infections (influenza, measles, hepatitis C, Epstein-Bass, coronavirus and human papillomavirus) as well as other pathogen-infection pathways (toll-like receptor signaling, TNF signaling, NOD-like receptor signaling). Since interferons inhibit viral replication in response to viral RNA in host cells [29] the above viral pathway connection is logical. Conversely, native RNA only stimulated one of these pathways (human papillomavirus). Also of note is the strong induction of the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway, a known proinflammatory pattern recognition receptor pathway [30], by both mitoxRNAs as well as the strong RIG-1 receptor pathway stimulation by HP mitoxRNA (Figure 9c). Volcano plots of the mitoxRNA enrichment results emphasizing the annotation pathways (rather than biological pathways shown in Figure 9a–c) are shown in Figure 9(d,e). These two plots highlight the numerous infection and immune pathways and their relative impact triggered by both mitoxRNAs, and also showcase modest differences between tBHP mitoxRNA versus HP mitoxRNA transfection responses per the similar but different orders besides the leading ‘Influenza A’ gene set.

Figure 9.

ORA analyses of gene ontology biological processes. Bar graph representations of top KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results in order. (a) Native, mock- versus native mtRNA transfection, (b) tBHP, mock- versus tBHP mitoxRNA-transfected, and (c) HP, mock- versus HP mitoxRNA-transfected. All FDR ≤ 0.05. (d) Volcano plot of above ‘B’ tBHP, mock- versus tBHP mitoxRNA-transfected, and (e) Volcano plot of above ‘C’ HP, mock- versus tBHP mitoxRNA-transfected. For the volcano plots, −log10 of FDR (Y-axis) is plotted against the log2 enrichment ratio (X-axis) with dot size and color proportional to the size of the category and dot position to the category significance.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we extend our previous studies to better understand the important role that oxidized (‘mitoxRNA’) and native (‘mtRNA’) mitochondrial RNA play as proinflammatory DAMPs. Our studies place special emphasis on type 1 interferons as they play a key role in DAMP immune response and inflammation. Our studies reveal a powerful redox effect. Even small changes in the actions of these cytokines can have profoundly negative effects on health and here, we observe oxidant potentiations as strong as threefold. The importance of oxidation is further supported by the significantly different impacts of the oxidants used (tBHP versus HP), and that much greater immunostimulatory potentiation of native polynucleotide occurs with mitochondrial RNA as compared with DNA. The tBHP versus HP results might also indicate that membrane-based oxidants such as lipid peroxides are more effective oxidizers of mitochondrial RNA (and perhaps DNA). Overall, our results support the conclusion that the regulatory (potentiating) effects of mitochondrial RNA oxidation are diverse and important. Cell type also appears relevant as we have observed different responses in different cell types in mice, and Dhir reports a strong transfected native mtRNA effect on IFNβ1 mRNA response in HeLa cells [21].

Our RNAseq analyses were especially insightful revealing mitoxRNA induction of many interferon-associated genes including IFNB1 itself over that observed with native mtRNA, and is consistent with and confirmed by our original Figures 1 and 2 studies. Predictably, pathway analysis revealed that the mitoxRNA transfections stimulated numerous pathways associated with various viral and other pathogen infections. These analyses also revealed that these cells respond to mitochondrial RNA, especially when oxidized, similar to a viral infection since interferons and interferon-stimulated genes inhibit viral replication in host cells [29,31]. Since there is no pathogen or infection protocol in our study, it is of additional interest as to what role this type 1 interferon induction response is playing beyond its usual combating infectious agent survival and propagation. Future studies assessing this should reveal even more valuable insight, perhaps even overlapping with typical anti-viral responses such as reducing protein translation and arresting cell growth.

Our apoptosis studies derive in part from our original observations [6], apoptosis induction by synthetic double-stranded RNA poly I:C, a viral infection mimic [23,25,26], and the interesting Killarney et al. connection between mtRNA induction of type 1 interferon, inflammation and executioner caspases [32]. While underscoring yet another interesting difference between mitochondrial RNA and DNA, the weak to modest mtRNA effect was nonetheless somewhat surprising given the known apoptotic effects of poly I:C. This might reflect a carefully evolved cellular response mechanism whereby mtRNA, when oxidized, acts more immunostimulatory but less apoptogenic than mtDNA. The modest mtRNA apoptogenic effect might also suggest that poly I:C, long used as a viral mimic, has limitations representing viral RNA as suggested by our observed modest effect from an actual cellular RNA source.

Limitations of these studies include the fact that inflammation is a complex cellular response and we are only examining a few important contributors. Subsequent studies combining these mitochondrial polynucleotides with other proinflammatory agents (e.g. proinflammatory cytokines themselves) would be useful as would assessing the impact of healthy dietary anti-inflammatories as a potential therapeutic treatment for related inflammatory diseases [33–36]. We also emphasize transfection studies and while highly useful and the basis for many biomedical discoveries through the years, their efficacy varies from cell to cell and can be somewhat low in THP-1 cells. Thus, repeating these studies with other more transfectable cells might produce even more robust results. And while not a limitation per se, we evaluated two oxidants (HP and tBHP) out of many that exist and so our conclusions should not be interpreted as representative of all others such as superoxide, peroxynitrite, and one- versus two-electron oxidants. Relative to this and since this paper has a major gene expression focus, it is already known that different oxidative stresses elicit different gene expression patterns, even from the same cells (e.g. [37,38]).

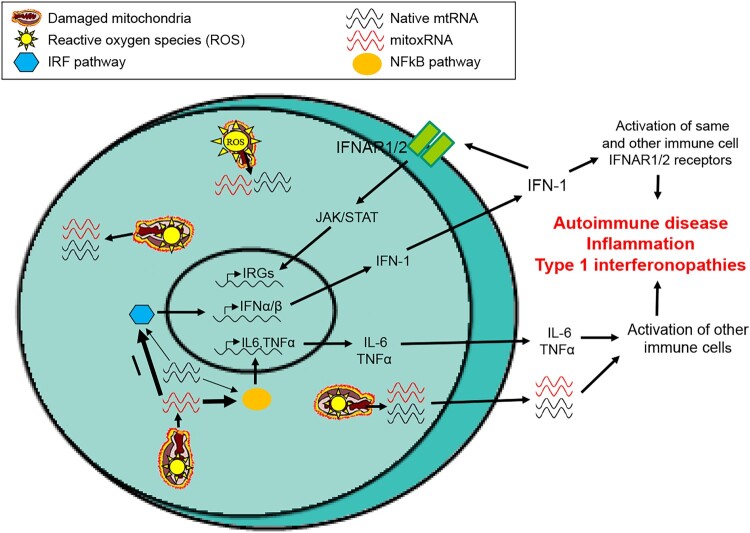

In Figure 10, we present a model overview of our findings with an emphasis on type 1 IFN. Conditions of stress including disease often raise the level of reactive oxygen species leading to oxidation of native mitochondrial RNA (and DNA), increased membrane permeability, and leakage to the cytosol as well as the extracellular space and circulation. Subsequently, leaked mitoxRNA in the cell produces a much stronger stimulation (represented as thicker arrows) of downstream effectors including key IRFs than any leaked native mtRNA, in turn increasing IFN-1 transcription. This IFN-1 is released and then binds to interferon receptors on the same and adjacent cells, triggering a JAK/STAT pathway transcriptional induction of interferon stimulated genes. Concurrently, proinflammatory gene induction occurs, both in these cells as well as in response to released mitoxRNAs, all contributing to organismal inflammation, autoimmune disease, type 1 interferonopathies and other disorders.

Figure 10.

Model of mitochondrial RNA immunostimulation in stressed cell emphasizing type 1 interferon. Proposed model of native mtRNA and mitoxRNA release, signaling and pathological effects.

5. Conclusions

These studies extend our understanding of the immunostimulatory effects of mitochondrial RNA and underscore the powerful effect that oxidation plays. Overall, we observe a pronounced oxidized mitochondrial RNA (mitoxRNA) potentiation of both type 1 interferon and proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-6); identify transcription as a major mechanism behind these type 1 interferon stimulations; observe significantly more potentiation of immunostimulation using tBHP as an oxidant as well as for mitoxRNA than mitoxDNA; observe a modest proapoptotic mtRNA as compared with mtDNA, neither of which are affected by oxidation; identify interferon-stimulated genes as abundant mediators of mitoxRNA immunostimulation; and identify chloroquine-inhibitable endosomes and MDA5 are key mediators of (non-oxidized) native mtRNA signaling pathways for IFNβ and TNFα cytokine production; These studies reveal a powerful regulatory effect of mtRNA oxidation, provide new insights into our understanding of inflammation, and identify multiple potential therapeutic targets to treat DAMP mtRNA/mitoxRNA-mediated inflammation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dawn Bellville, Dr. Zoran Ilic, Dr. Sivakumar Periasamy, Dr. Jim Drake, Dr. Jon Harton, Djenabou Diallo, Shantanu Sheth, and Diego Fu. We also thank Dr. Don Steiner for Albany Medical College immunology core facility technical assistance.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R03AI168677 (to D.R.C.) and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST110-2314-B-038-147 and MOST110-2314-B-038-115 to H.Y.L.).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon request. The dataset DOI is.

References

- 1.Slavich GM. Understanding inflammation, its regulation, and relevance for health: a top scientific and public priority. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;45:13–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cifuentes M, Verdejo HE, Castro PF, et al. Low-grade chronic inflammation: a shared mechanism for chronic diseases. Physiology (Bethesda). 2025;40(1):0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew A, Lindsley TA, Sheridan A, et al. Degraded mitochondrial DNA is a newly identified subtype of the damage associated molecular pattern (DAMP) family and possible trigger of neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:617–627. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saxena AR, Gao LY, Srivatsa S, et al. Oxidized and degraded mitochondrial polynucleotides (DeMPs), especially RNA, are potent immunogenic regulators in primary mouse macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;104:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilic Z, Saxena AR, Periasamy S, et al. Control (native) and oxidized (DeMP) mitochondrial RNA are proinflammatory regulators in human. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;143:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford DR, Lauzon RJ, Wang Y, et al. 16S mitochondrial ribosomal RNA degradation is associated with apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;22:1295–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(96)00544-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abramova NE, Davies KJA, Crawford DR.. Polynucleotide degradation during early stage response to oxidative stress is specific to mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;28:281–288. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00239-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y, Jiang W, Zhou R.. DAMP sensing and sterile inflammation: intracellular, intercellular and inter-organ pathways. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;24(10):703–719. doi: 10.1038/s41577-024-01027-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianchi ME. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J Leukocyte Biol. 2007;81:1–5. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roh JS, Sohn DH.. Damage-associated molecular patterns in inflammatory diseases. Immune Netw. 2018;18(4):e27. doi: 10.4110/in.2018.18.e27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins LV, Hajizadeh S, Holme E, et al. Endogenously oxidized mitochondrial DNA induces in vivo and in vitro inflammatory responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:995–1000. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pazmandi K, Agod Z, Kumar BV, et al. Oxidative modification enhances the immunostimulatory effects of extracellular mitochondrial DNA on plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;77:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W.. The subread aligner: fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(10):e108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang B, Kirov S, Snoddy J.. WebGestalt: an integrated system for exploring gene sets in various biological contexts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W741–W748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji L, Li T, Chen H, et al. The crucial regulatory role of type I interferon in inflammatory diseases. Cell Biosci. 2023;13:230. doi: 10.1186/s13578-023-01188-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crow MK, Olferiev M, Kirou KA.. Type I interferons in autoimmune disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:369–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Londe AC, Fernandez-Ruiz R, Julio PR, et al. Type I interferons in autoimmunity: implications in clinical phenotypes and treatment response. J Rheumatol. 2023;50(9):1103–1113. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.2022-0827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma W, Kleiman NJ, Sun F, et al. Characteristics of tertiary butyl hydroperoxide and hydrogen peroxide conditioned cells withdrawn from peroxide stress. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78(5):1037–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altman SA, Zastawny TH, Randers L, et al. Tert-butyl hydroperoxide-mediated DNA base damage in cultured mammalian cells. Mutat Res. 1994;306(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90165-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC.. Free radicals in biology and medicine. 5th ed. New York (NY: ): Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhir A, Dhir S, Borowski LS, et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA triggers antiviral signaling in humans. Nature. 2028;560(7717):238–242. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0363-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crossley MP, Song C, Bocek MJ, et al. R-loop-derived cytoplasmic RNA-DNA hybrids activate an immune response. Nature. 2023;613(7942):187–194. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05545-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen H, Wang DL, Liu YL.. Poly (I:C) transfection induces mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in cervical cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13(3):2689–2695. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeshita F, Ishii KJ.. Intracellular DNA sensors in immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20(4qqq):383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang J, Wang S, Fang J, et al. Stable silencing of TIPE2 reduced the Poly I:C–induced apoptosis in THP–1 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:6313–6319. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yapp CW, Widaad Mohaimin A, Idris A.. Poly I:C Delivery into J774.1 and RAW264.7 macrophages induces rapid cell death. Iran J Immunol. 2017;14(3):250–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rintahaka J, Lietzén N, Öhman T, et al. Recognition of cytoplasmic RNA results in cathepsin-dependent inflammasome activation and apoptosis in human macrophages. J Immunol. 2011;186(5):3085–3092. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buys W, Bick A, Madel RJ, et al. Substantial heterogeneity of inflammatory cytokine production and its inhibition by a triple cocktail of toll-like receptor blockers in early sepsis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1277033. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1277033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sengupta P, Chattopadhyay S.. Interferons in viral infections. Viruses. 2024;16(3):451. doi: 10.3390/v16030451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teissier T, Boulanger É. The receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) is an important pattern recognition receptor (PRR) for inflammaging. Biogerontology. 2019;20(3):279–301. doi: 10.1007/s10522-019-09808-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM.. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Killarney ST, Washart R, Soderquist RS, et al. Executioner caspases restrict mitochondrial RNA-driven Type I IFN induction during chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):1399. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37146-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, et al. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(8):1689–1696. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013002115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Byrd DA, Judd SE, Flanders WD, et al. Development and validation of novel dietary and lifestyle inflammation scores. J Nutr. 2019;149(12):2206–2218. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxz165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ford ML, Cooley JM, Sripada V, et al. Eat4Genes: a bioinformatic rational gene targeting app and prototype model for improving human health. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1196520. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1196520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagyi J, Sripada V, Aidone AM, et al. Dietary rational targeting of redox-regulated genes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;173:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crawford DR, Suzuki T, Davies KJA.. Oxidant-modulated gene expression. In: Sen CK, Sies H, Baeuerle PA, editors. Antioxidant and redox regulation of genes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. p. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki T, Spitz DR, Gandhi P, et al. Mammalian resistance to oxidative stress: a comparative analysis. Gene Expr. 2002;10(4):179–191. doi: 10.3727/000000002783992442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request. The dataset DOI is.