Abstract

Therapeutics for thin endometrium (TE) have emerged, with autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy gaining significant attention. In the present study, ten eligible TE patients were recruited for PRP infusion. Endometrial tissue biopsies collected before and after PRP therapy (paired samples) were subjected to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Additionally, haematoxylin and eosin (HE) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were employed to validate changes in protein markers. The results demonstrated PRP therapy increased the average endometrial thickness in these patients. Cellular trajectory reconstruction analysis using gene counts and expression (CytoTRACE) scores indicated that high-stemness cells were more enriched in proliferating stromal cells (pStr) or stromal cells (Str) in post-PRP samples, while greater stemness was observed in glandular epithelial cells (GE) and luminal epithelial cells (LE). Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) revealed significant differences in mesenchymal‒epithelial transition (MET)-related gene signature scores between paired samples. Furthermore, an increased number of macrophages, particularly M1-type macrophages, was detected in post-PRP samples. As the first study to investigate the effects of PRP therapy via transcriptomic analysis, our findings suggest PRP therapy may enhance high-stemness, stimulate MET, and boost macrophage function. These insights contribute to a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying PRP therapy and its potential in treating TE patients.

Keywords: Platelet-rich plasma, Thin endometrium, Single-cell RNA sequencing, Stem cell, Mesenchymal‒epithelial transition, Macrophage polarization

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Diseases, Medical research, Molecular medicine

Introduction

The human endometrium, the uterine lining, displays a high regenerative capacity throughout the reproductive age. Dysfunction of the endometrium may contribute to infertility and unhealthy conditions, which include endometriosis, endometrial cancer, and abnormal uterine bleeding1. TE, normally defined as an endometrial thickness (ET) less than 7 mm on an ultrasound scan, is the main reason for impaired endometrial receptivity during in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles2. Accumulating evidence has shown that embryo transfers performed in patients with TE have reduced implantation and clinical pregnancy rates3.

Methods of endometrial repair or therapeutic options for TE have emerged in recent years to solve this clinical problem4–6. These methods mainly include oestrogen therapy, multiple medication regimens, immunomodulatory methods or stem cell transplantation, but their efficacy may differ. Chang et al. reported the use of PRP therapy for TE patients in 2015, and they achieved promising outcomes because of its regenerative properties7. PRP is a fraction of plasma with an autologous concentration of platelets and has attracted increasing attention in reproductive medicine because of the presence of cytokines and various growth factors8. With the help of PRP, some success has recently been achieved in enhancing endometrial function in infertile patients with TE, recurrent implantation failure (RIF) and refractory endometrium9. Although the precise function of PRP in enhancing implantation is not fully understood, PRP may have positive effects on various cell types of the endometrium, including endometrial epithelial cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, or stromal mesenchymal stem cells10. Modern scientific technology is necessary to elucidate the cellular and molecular mechanisms of PRP therapy11,12.

Transcriptomic analysis provides an understanding of gene structure and function and enables an understanding of the human genome at the transcriptional level13. Currently, single-cell transcriptomics using next-generation sequencing has become a powerful tool for analysing cell-to-cell variability at the genome scale14. Advances in single-cell technology provide an unbiased and optional workflow allowing cells to be sequenced without prior knowledge of target genes and proteins and to group cells according to their transcriptional characteristics. Recent breakthroughs in scRNA-seq offer the possibility of enhancing the detection of cell types with low frequencies and blurred intermediate cell states based on the transcriptome of each cell15. This method is expected to map cellular phenotypic heterogeneity and identify previously undefined cell populations, as well as their gene expression properties. To date, scRNA-seq has been applied to the discovery of cellular states in health and disease across various systems, and TEs are frequently investigated. The first transcriptomic atlas of TE was constructed by Zhang et al. in 2022, from the late proliferative phase to the middle secretory phase at the single-cell level16. Moreover, Lv et al. profiled the transcriptomes of human endometrial cells at single-cell resolution to characterize cell types, cell communication, and the underlying mechanism of endometrial growth within normal and TE in the proliferative phase17. In addition, Xu et al. combined scRNA-seq methods and one bulk sequencing method for TE to perform an integrated analysis of endometrial cells in the proliferative phase, and they reported dysfunction of intercellular signal transduction and impaired metabolic signalling pathways18. Recently, Fu et al. systematically investigated a single-cell transcriptomic atlas across three distinct groups of patients and provided valuable insights into the heterogeneous molecular pathways and cellular interactions related to RIF19.

However, a comprehensive transcriptome analysis of the effect of PRP therapy on TE patients has not yet been performed using scRNA-seq. The present study aimed to explore endometrial transcriptomic changes in response to PRP therapy. Our results suggest changes in the human endometrium after PRP, which involves three points of interest: the efforts of epithelial or stromal stem cells to contribute to re-epithelization, the contribution of MET to cellular transdifferentiation, and the polarization of macrophages that regulate local immune responses. We believe these important findings will help decipher and elucidate the critical dynamics of autologous PRP therapy in TE patients.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the use of clinical endometrial samples and the procedures involved in this study were approved by Ethics Committee of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (2021135, approver Yonghong Lai). Informed consent was obtained from each participant before the endometrial biopsy.

Standardized criteria for the admission of TE patients

The inclusion criteria were infertile patients who had received assisted reproduction treatment and had frozen embryos in storage, and women whose endometrial thickness failed to expand beyond 5.5 mm with the use of 6–8 mg/day oestradiol valerate, and gradually increased to 12 mg/day as needed combined with at least one round of treatment with aspirin20. A hysteroscopic examination was performed to confirm that no intrauterine adhesions were present; the patient was not a smoker; and no abnormalities in metabolism, blood coagulation, the immune system, heart, lung, liver, kidney, or reproductive tract were present. The exclusion criteria were as follows: reproductive tract infections, endometriosis, congenital uterine malformations, adenomyosis, uterine fibroids that could impair embryo implantation, RIF, the presence of a tumour, or the presence of an intrauterine device. For the study by Lv et al.17, forty-five patients who needed hysteroscopic examination at the Infertility Consulting Clinic at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital were enrolled, including twenty patients with thin endometria and twenty-five controls with normal endometria. The diagnosis of TE was based on their ET < 7 mm at mid-luteal phase or had histories of embryos transfer cancellation in vitro fertilization procedures due to TE17. Those patients also presented scanty menstruation, poor response to estrogen stimulations and normal uterine cavity by hysteroscopy. Normal controls had normal menstrual blood volume and ET was between > 8 mm – < 14 mm at mid-luteal phase and normal ovary function17. All participants presented regular menstrual cycling, normal karyotype and negative serological tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and syphilis. Patients with endometriosis, leiomyoma or adenomyosis or polycystic ovary syndrome were excluded.

PRP preparation for treatment

Autologous PRP was prepared on the day of PRP infusion. A total of 40 ml of venous blood was collected into a 50 ml centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 1500 rpm (MODEL S300TR, KUBOTA CORPORATION, JAPAN) for 10 min. After centrifugation, the upper 3.5 ml of plasma was transferred for storage, and the remaining plasma was transferred to another tube and centrifuged at 2800 rpm (MODEL S300TR, KUBOTA CORPORATION, JAPAN) for 15 min. After the second centrifugation, the remaining supernatant plasma was discarded, and the remaining 1.5 ml of plasma plus precipitated platelets was mixed with 3.5 ml of plasma from the first separation step. The platelet concentration was determined using an automatic cell counting system until it reached approximately 1012/L. After adding 0.5 ml of calcium chloride (the ratio of calcium chloride to PRP was 1:10), the prepared PRP solution was ready for transferring.

PRP infusion in TE patients

On the third day of the menstrual cycle after a transvaginal ultrasound evaluation, TE patients were initially treated with a 3–4 mg dose of oestradiol two times daily21. After 7 days, another ultrasound evaluation of ET was performed. If the ET was less than 5.5 mm, the first uterine PRP infusion was performed on the 8th day of endometrial preparation. The activated PRP obtained above was slowly infused into the uterine cavity using a Insemi™-catheter (COOK MEDICAL, USA) in attached to a syringe containing 1 ml of PRP. After 3–4 days, the ET was evaluated and an endometrial tissue biopsy was performed. The oestradiol dosage was increased to 9 tablets (1 mg for 1 tablet) daily. Simultaneously, the second PRP infusion was administered. After two PRP infusions and 3–4 days to assess the ET, progesterone supplementation was initiated.

Endometrial tissue biopsy

Endometrial tissues were first harvested from TE patients during the late proliferative phase via hysteroscopic examination. Similarly, the second endometrial biopsy sample was collected 3‒4 days after the first PRP application. An endometrial biopsy was obtained using a disposable uterine cavity aspiration cannula (Shanghai, China), which was inserted into the uterus and used to scratch the uterine lining. The procedure was performed without anaesthesia. After the hysteroscopic examination and PRP therapy, both biopsies from TE patients were placed in ice-cold 0.9% sodium chloride and then transported on ice to preserve cell viability.

scRNA-seq and preparation of the endometrial sample

Sample processing and cDNA library preparation (10x) were performed with biopsies of paired endometrial samples. The samples were prepared as described previously14. The Chromium Single Cell 5′ Library, Gel Bead and Multiplex Kit, and Chip Kit (10 × Genomics) were used to convert single-cell suspensions of scRNA-seq samples into barcoded scRNA-seq libraries. After sequencing on the NovaSeq 6000 platform, the average sequencing depth of the mRNA library was 50,000 read pairs per cell. The sequencing reads were aligned to human genome reference sequences (GRCh38), and gene-level unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts were obtained using Cell Ranger 3.1.0 (10 × Genomics). The generated read count matrices were analysed in R (v3.5.2, https://www.R-project.org) via Seurat (v3.1.1) following filtering, variable gene selection, normalization, scaling, dimensionality reduction, clustering and visualization. The cells had fewer than 200 detected genes or greater than the upper percentiles (expected multiple rates according to the 10 × Genomics Single Cell 3’v3 Reagent Kit user guide). UMIs, as well as cells with greater than the upper percentile (95%) of mitochondrial reads, with a few remaining T and B cells, were removed.

Clustering analysis of the scRNA-seq data

The cell clusters were visualized using t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE). The major cell type-specific markers were screened by Seurat, which satisfies a p value ≤ 0.05 and greater than or equal to 2 times the differential expression range, to identify differentially expressed genes between the specified cell population and the remaining cell population.

Gene ontology and pathway enrichment analyses of differentially expressed genes

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were performed using clusterProfiler v3.6.0 to analyse the functions of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)22–24.

Cellular trajectory reconstruction analysis using gene counts and expression (CytoTRACE)

The CytoTRACE algorithm was developed by Gulati et al. in 202025. CytoTRACE captures, smooths, and calculates the expression levels of genes most strongly correlated with single-cell gene counts using scRNA-Seq data26. When the calculation of the CytoTRACE algorithm is complete, each single cell will receive a score that represents its stemness within the given dataset. The R package CytoTRACE v0.3.3 was used to calculate CytoTRACE scores for different cells. CytoTRACE scores range from 0 to 1, where higher scores indicate greater stemness (less differentiation) and vice versa.

Gene set variation analysis

For the gene set variation analysis (GSVA), the hallmark and related gene pathways used for the functional analysis were downloaded from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB)14. GSVA was performed using the GSVA R package (v1.32.0)27.

Pseudotime analysis

Monocle 2 (v2.10.1) was used to estimate the pseudotemporal path of macrophage differentiation14. The macrophages were ordered in pseudotime along a trajectory using reduceDimension with the DDRTree method and orderCells functions19. The GO terms of cells in each state were applied via clusterProfiler (v3.10.1), as mentioned above.

Haematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining

Endometrial tissues were collected for histology according to the standard procedures described below16. Briefly, the tissues were fixed with paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and then cut into 5 µm thick sections. After dewaxing with xylene, the tissue sections were sequentially immersed in a graded alcohol series and distilled water and then dyed with haematoxylin (5 min) and eosin (1 min) (Sigma, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, sections were prepared as described above. Antigen retrieval was conducted in a water bath (60 °C), and the sections were incubated in sodium citrate solution (pH = 6.0) overnight14. After cooling to room temperature, the sections were permeabilized with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min, followed by blocking endogenous peroxidases with 3% (vol/vol) H2O2 for 20 min. Nonspecific binding of the antibodies was blocked with 10% (vol/vol) normal donkey serum in PBS for 1 h, followed by an incubation with primary antibodies against octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (Oct-4, 1:100, Cell Signaling, USA, C30A3), STRO-1 (1:200, Merck Millipore, Ger, MAB4315), stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1, 1:200, Abcam, USA, AB25117), cytokeratin 8 (KRT8, 1:500, Hangzhou Huaan Biotechnology, China, ET1610-43), vimentin (VIM, 1:500, Hangzhou Huaan Biotechnology, ET1610-39), E-cadherin (E-cad, 1:200, Hangzhou Huaan Biotechnology, China, ET1607-75), inducible NO synthase (iNOS, 1:200, Abcam, USA, AB283655), arginase-1 (Arg1, 1:100, Cell Signaling, USA, D4E3M) and CD31 (1:200, Abcam, USA, AB281583) overnight at 4 °C, followed by an incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit/mouse (H + L) secondary antibodies (Dako, USA) for 40 min at room temperature. The primary antibody was replaced with PBS as a negative control. Three washes with PBS were performed between antibody incubations. A 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) kit (Dako, USA) was used to visualize the binding sites, and sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (Sigma, USA). After dehydration, permeabilization, and mounting, the sections were observed under an Olympus BX43 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as the means ± standard deviations (SDs). Comparisons between normally distributed continuous variables were performed using Student’s t test. Multiple comparisons of continuous variables were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni post hoc correction. For the scRNA-seq analysis, the significance of DEGs was determined by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and adjusted by the Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple tests. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 23.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant14.

Results

PRP therapy increased the average endometrial thickness of ten TE patients

Ten eligible TE patients were recruited for PRP therapy (Table 1). The average age of these patients was 34.9 ± 5.4 years. The mean pre-PRP endometrial thickness was 4.19 ± 0.5 mm, and the post-PRP was 4.85 ± 0.5 mm. Significant differences (p = 0.012) were observed between the pre- and post-PRP endometrial thickness, which suggested endometrial expansion after PRP therapy (Table 1). To reveal the underlying mechanism, we sampled paired endometria from these patients and obtained a transcriptomic atlas by using scRNA-seq28.

Table 1.

PRP therapy increased the average endometrial thickness of ten TE patients.

| TE patient (n) | Age (y) | Pre-PRP ET (mm) | Post-PRP ET (mm) | P value (T test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 34.9 ± 5.4 | 4.19 ± 0.5 | 4.85 ± 0.5 | 0.012* |

| 1 | 28 | 3.7 | 4.2 | |

| 2 | 33 | 4.0 | 5.8 | |

| 3 | 32 | 4.8 | 4.8 | |

| 4 | 38 | 3.5 | 4.3 | |

| 5 | 43 | 4.5 | 5.0 | |

| 6 | 30 | 4.7 | 5.6 | |

| 7 | 40 | 3.4 | 4.5 | |

| 8 | 33 | 4.1 | 5.1 | |

| 9 | 42 | 4.5 | 4.5 | |

| 10 | 30 | 4.7 | 4.7 |

Cellular heterogeneity and subtypes in paired endometrial samples

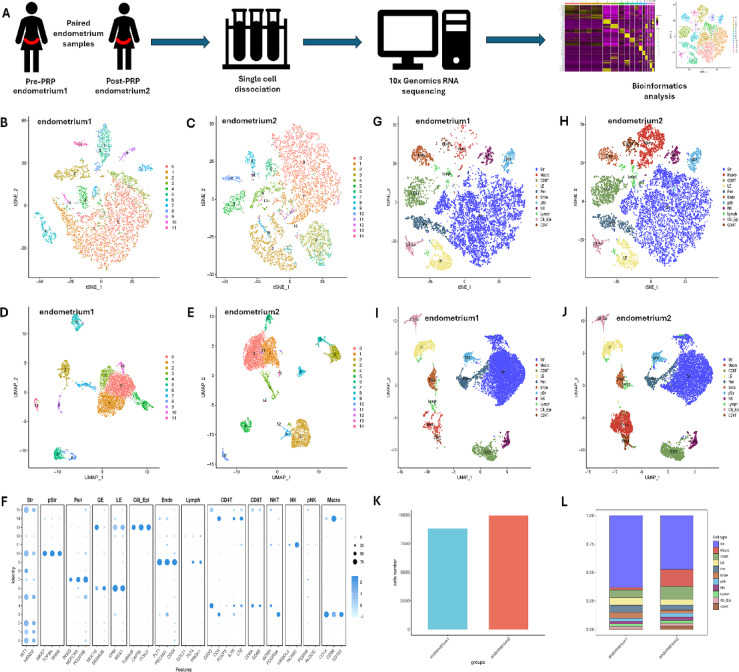

The scRNA-seq data were analysed with strict quality control criteria (Fig. 1A). A total of 8823 or 9953 cells from pre-PRP (endometrium 1) and post-PRP (endometrium 2) samples were sequenced (Table 2). After filtering, gene expression was normalized for read depth. Principal component analysis (PCA) was then applied to genes with variable expression and for dimension reduction via t-SNE (Fig. 1A). A t-SNE map of pre- and post-PRP samples was generated, which included 11 and 14 clusters, respectively (Fig. 1B,C). All these clusters were also visualized in a separated uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot (Fig. 1D,E).

Fig. 1.

Cellular heterogeneity and subtypes in paired endometrial samples. (A) Experimental workflow of tissue collection, single-cell dissociation, RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. (B) t-SNE map of pre-PRP tissue samples. (C) t-SNE map of post-PRP tissue samples. (D) UMAP plot of pre-PRP tissue samples. (E) UMAP plot of post-PRP tissue samples. (F) Recognized cell markers used in the process of cell type annotation. (G) t-SNE map of different cell types in pre-PRP tissue samples. (H) t-SNE map of different cell types in post-PRP tissue samples. (I) UMAP plot of different cell types in pre-PRP tissue samples. (J) UMAP plot of different cell types in post-PRP tissue samples. (K) Different cell numbers in paired samples. (L) Different cell proportions in paired samples.

Table 2.

Cell numbers and proportions within paired endometrial samples.

| Cell type | Pre-PRP cell number | Pre-PRP cell percentage | Post-PRP cell number | Post-PRP cell percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Str | 5569 | 63 | 4701 | 47 |

| Mac | 182 | 2 | 1501 | 15 |

| CD8+ T | 599 | 6.8 | 1127 | 11.4 |

| LE | 598 | 6.7 | 482 | 4.9 |

| Peri | 571 | 6.5 | 442 | 4.5 |

| Endo | 435 | 5 | 280 | 2.8 |

| pStr | 237 | 2.7 | 326 | 3.3 |

| NK | 200 | 2.4 | 310 | 3.1 |

| Lymph | 198 | 2.3 | 239 | 2.4 |

| Cili_Epi | 188 | 2.1 | 218 | 2.2 |

| CD4+ T | 46 | 0.5 | 327 | 3.4 |

| Total | 8823 | 100 | 9953 | 100 |

Based on transcriptomic results from Lv et al.17, widely recognized cell markers were further used in the process of cell type annotation (Fig. 1F): WT1 and HAND2 for stromal cells (Str); CD14, CD86 and CD163 for macrophages (Mac); CD8A and CD8B for CD8+ T cells; CPM and MSX1 for luminal cells (LE); RGS5, NOTCH3 and PDGFRB for perivascular cells (Peri); FLT1, PECAM1 and CD34 for endothelial cells (Endo); MKI67, TOP2A and RRM2 for proliferating stromal cells (pStr); KIR2DL4 and NCAM1 for natural killer cells (NK); CCL21, FLT4 and PROX1 for lymph node cells (Lymph); TUBA4B, CAPSL and FOXJ1 for ciliated epithelial cells (Cili_Epi); and CD3D, CD4, FOXP3, IL7R and LTB for CD4+ T cells. Therefore, 11 major cell types are shown in both the t-SNE and UMAP plots (Fig. 1G–J). The cell numbers and proportions in paired endometrial samples were also determined (Table 2, Fig. 1K,L). The proportions of stromal cells and macrophages clearly changed after PRP therapy (Fig. 1K,L). Compared with those in pre-PRP samples, the percentage of stromal cells in post-PRP samples decreased (63% vs. 47%), whereas the percentage of macrophages increased (2% vs. 15%).

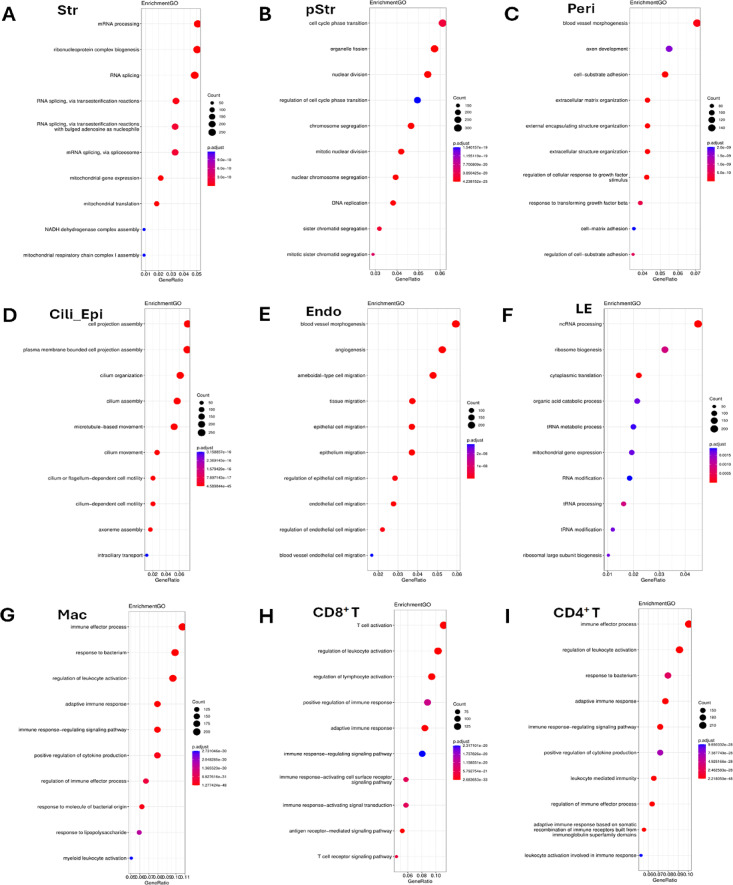

Enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in paired endometrial samples

An integrated comparative analysis was performed as previously described16. Based on clustering results from the canonical correlation analysis (CCA), DEGs were obtained by comparing endometrial samples before and after the PRP infusion (Fig. 2). GO and KEGG pathway analyses of 11 major cell types were subsequently performed. According to the results reported by Lv et al., these 11 cell types can be divided into 3 categories17: stromal cell niches (Str, pStr, and Peri); epithelial cell niches (Cili_Epi, Endo, LE, and Lymph); and immune cell niches (Mac, CD8+ T, CD4+ T, and NK cells). For stromal cell niches (Fig. 2A–C), the robust enriched pathways (top 3) were mRNA processing, ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis, RNA splicing, cell cycle phase transition, organelle fission, nuclear division, blood vessel morphogenesis, axon development, and cell–substrate adhesion. The most enriched pathways (top 3) of epithelial cell niches were related to cell projection assembly, plasma membrane-bound cell projection assembly, cilium organization, blood vessel morphogenesis, angiogenesis, ameboidal-type cell migration, ncRNA processing, ribosome biogenesis, and cytoplasmic translation (Fig. 2D–F). In addition, the significantly enriched pathways (top 3) for immune cells included the immune effector process, response to bacteria, regulation of leukocyte activation, T-cell activation, and regulation of lymphocyte activation (Fig. 2G–I).

Fig. 2.

Enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in paired endometrial samples. (A) GO and KEGG pathway analyses of Str cells. (B) GO and KEGG pathway analyses of pStr cells. (C) GO and KEGG pathway analyses of Peri cells. (D) GO and KEGG pathway analyses of Cili_Epi cells. (E) GO and KEGG pathway analyses of Endo cells. (F) GO and KEGG pathway analyses of LE cells. (G) GO and KEGG pathway analyses of Mac cells. (H) GO and KEGG pathway analyses of CD8+ T cells. (I) GO and KEGG pathway analyses of CD4+ T cells.

Cell stemness of stromal and epithelial cell niches in paired endometrial samples

Progenitors of stromal and epithelial cells need to be further evaluated using the CytoTRACE framework to regenerate the endometrium28. We first analysed the stemness of endometrial tissue from normal and TE patients using the sequencing data from the study by Lv et al.17. The distributions of the CytoTRACE score and cellular response phenotype predicted the stemness order of different cell clusters (Fig. 3A,B). After double checking the UMAPs of normal controls and TE patients (Fig. 3E‒F), the first three orders of the CytoTRACE score were phenotypes 12, 7 and 13 in the stromal cell niche, defined as pStr, Str and Peri cells, whereas phenotypes 0, 6 and 1 in the epithelial cell niche were classified as glandular epithelial (GE) and LE cells (Fig. 3C,D). As predicted by CytoTRACE, cells with high stemness were more enriched in pStr and Str cells from normal controls than in those from TE patients (Fig. 3G–H). However, greater enrichment of stemness was observed in the LE and GE cells of TE patients than in those of normal controls (Fig. 3G–H). For PRP therapy, CytoTRACE scores predicted that high-stemness were more enriched in pStr or Str cells of post-PRP samples (endometrium 2, E2), whereas much greater stemness were detected in GE and LE cells than in pre-PRP samples (endometrium 1, E1), suggesting the regenerative role of PRP infusion (Fig. 3I–J). Results of IHC confirmed strong staining for STRO-1 and SDF-1, whereas weak staining for Oct-4 was observed in post-PRP tissue samples (Fig. 3K).

Fig. 3.

Cell stemness of the stromal and epithelial cell niches in paired endometrial samples. (A) CytoTRACE scores and cellular response phenotypes of stromal cell niches in normal controls and TE patients. (B) CytoTRACE scores and cellular response phenotypes of epithelial cell niches in normal controls and TE patients. (C) Stemness orders of different cell clusters in stromal cell niches. (D) Stemness orders of different cell clusters in epithelial cell niches. (E) UMAPs of stromal cell niches in normal controls and TE patients. (F) UMAPs of epithelial cell niches in normal controls and TE patients. (G) CytoTRACE predicted that high stemness was more enriched in pStr and Str cells from normal controls. (H) A greater enrichment of stemness was observed in LE and GE cells from TE patients. (I) CytoTRACE predicted that high stemness was enriched in pStr or Str cells from post-PRP samples. (J) Much greater stemness was detected in GE and LE cells from post-PRP samples. (K) IHC confirmed strong staining for STRO-1 and SDF-1, weak staining of Oct-4 in post-PRP samples (DAB, 50 µm).

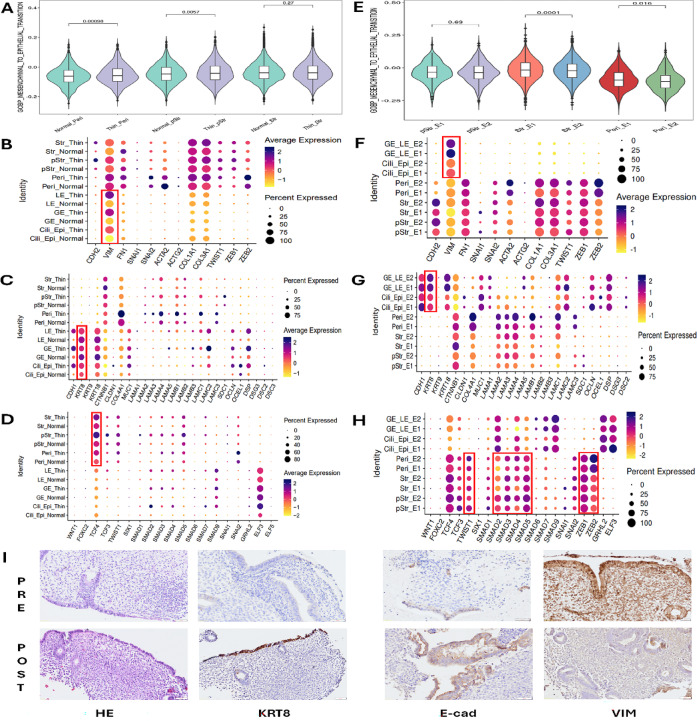

Comparison of MET pathway activity between pre- and post-PRP samples

Lv et al. speculated that some epithelial cells are derived from stromal cell differentiation via MET17. GSVA was utilized to calculate the activity of the MET signalling pathway with clinical samples from normal control and TE patients, and paired samples before and after PRP therapy to solve this problem (Fig. 4). GSVA revealed significant differences (p = 0.00098) in MET-related gene signature scores in Peri cells between normal control and TE patients, and significant differences (p = 0.0057) in pStr or Str cells (Fig. 4A). With respect to the identity of MET markers, especially VIM and KRT8, the epithelial cells of TE patients presented relatively high expression of VIM and low expression of KRT8, suggesting immature re-epithelization (Fig. 4B,C). Furthermore, only one of the MET transcription factors, TCF4, was relatively upregulated in TE patients compared with normal controls, indicating that the process by which MET generated sufficient epithelial cells was incomplete (Fig. 4D). However, PRP therapy changed this situation, since significant differences in MET-related gene signature scores were observed between Str (p = 0.0001) and Peri (p = 0.016) cells (Fig. 4E). The epithelial cells of post-PRP patients presented relatively lower expression of VIM but similar or higher expression of KRT8 (Fig. 4F–G). Moreover, in addition to TCF4, other MET transcription factors, such as TWIST1, SMAD family members, ZEB1 and ZEB2, were activated (Fig. 4H), suggesting that the ongoing activation of endometrial re-epithelization was stimulated by PRP therapy. IHC results confirmed that PRP infusion therapy induced the expression of KRT8 and E-cad while reducing the VIM protein level (Fig. 4I).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of MET pathway activity between pre- and post-PRP samples. (A) GSVA was used to calculate the activity of the MET signalling pathway in samples from normal control and TE patients. (B) Epithelial cells from TE patients presented relatively high expression of VIM (red rectangle). (C) Epithelial cells from TE patients presented relatively low expression of KRT8 (red rectangle). (D) The expression of only one of the MET transcription factors, TCF4, was relatively upregulated in TE patients compared with normal patients (red rectangle). (E) Significant differences in MET-related gene signature scores were observed in the Str and Peri cells of post-PRP samples. (F) Epithelial cells from post-PRP samples presented relatively low expression of VIM (red rectangle). (G) Epithelial cells from post-PRP samples presented relatively similar or higher expression of KRT8 (red rectangle). (H) In addition to TCF4, other MET transcription factors, such as TWIST1, SMAD family members, ZEB1 and ZEB2, were activated (red rectangle). (I) IHC showed PRP therapy induced the expression of KRT8 and E-cad while reducing the protein level of VIM (DAB, 50 µm).

The polarization and development of macrophages are affected by PRP infusion

As mentioned above, more macrophages were observed in endometrial tissue after the autologous PRP infusion (Table 2). A t-SNE map or UMAP plot of macrophages from pre- and post-PRP samples was generated, which revealed heterogeneous populations and 7 separate clusters in each paired sample (Fig. 5A–G).

Fig. 5.

Heterogeneity and subtypes of macrophages in paired endometrial samples. (A) t-SNE map of macrophages in paired tissue samples. (B) t-SNE map of macrophages in pre- and post-PRP tissue samples. (C) UMAP plot of macrophages in paired tissue samples. (D) UMAP plot of macrophages in pre- and post-PRP tissue samples. (E) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes in macrophages from pre- and post-PRP tissue samples. (F) Numbers of macrophages in pre- and post-PRP tissue samples. (G) Proportions of macrophages in pre- and post-PRP tissue samples. (H) Detection of the cell markers used to assess the process of macrophage polarization. (I) t-SNE map of M1- and M2-type macrophages in paired tissue samples. (J) t-SNE map of M1- and M2-type macrophages in pre- and post-PRP tissue samples. (K) UMAP plot of M1- and M2-type macrophages in paired tissue samples. (L) UMAP plot of M1- and M2-type macrophages in pre- and post-PRP tissue samples. (M) Numbers of M1- and M2-type macrophages in paired samples. (N) Proportions of M1- and M2-type macrophages in paired samples.

For the assessment of macrophage polarization, cell markers of the M1 and M2 phenotypes were utilized, and the detailed generation of these two types was analysed29. Along with the increased number of macrophages detected in the post-PRP sample, a greater number of M1-type macrophages was also detected (Fig. 5H–N). The activities of both M1- and M2-type macrophages prompted us to further compare the DEGs and GO pathways between paired samples (Fig. 6). For the M1 type, the most enriched pathways (top 3) were the innate immune response, the inflammatory response, and the regulation of cytokine production, which are consistent with the main functions of M1-type macrophages (Fig. 6A,B). For the M2 type, the significantly enriched pathways (top 3) were positive regulation of immune system processes, regulation of the immune response and lymphocyte activation (Fig. 6C,D). GVSA scores revealed that signalling pathways associated with VEGF were predominant in paired endometrial samples (Fig. 6E). Additionally, a trajectory analysis was performed on both types of macrophages by combining the 4 phases of development30. Both the M1 and M2 phenotypes clearly shifted from phase 2 to phase 4 after PRP therapy (Fig. 6F). Diverse dot-points of the M1 and M2 phenotypes reflected that the active state of the macrophages was affected by the PRP infusion (Fig. 6F). IHC staining of macrophages revealed stronger staining for the typical protein marker of the M1 type (iNOS), whereas weaker staining for the marker of the M2 type (Arg1) was observed after autologous PRP therapy (Fig. 6G). Clear staining for CD31 was also detected in various epithelial cell niches of endometrial tissue (Fig. 6G).

Fig. 6.

Effects of the PRP infusion on the polarization and development of macrophages. (A, B) DEGs and GO analysis revealed that pathways which were most enriched in M1-type macrophages (top 3) were the innate immune response, the inflammatory response, and the regulation of cytokine production. (C, D) Significantly enriched pathways (top 3) in M2-type macrophages were the positive regulation of immune system processes, regulation of the immune response and lymphocyte activation. (E) GVSA scores indicated that signalling pathways associated with VEGF were predominant in paired endometrial samples (red rectangle). (F) Both the M1 and M2 phenotypes clearly shifted from phase 2 to phase 4 after PRP therapy. Diverse dot-points of the M1 and M2 phenotypes reflected the active state of the macrophages was affected by the PRP infusion. (G) Strong staining for a typical protein marker of the M1 type (iNOS), and none staining for a marker of the M2 type (Arg1) were observed after autologous PRP therapy (DAB, 50 µm). Clear staining for CD31 was also detected in various epithelial cell niches of the endometrial tissue (DAB, 50 µm).

Discussion

Although our clinical analysis of ten TE patients suggested the average increase of endometrial thickness, conflicting results still exist for the application of PRP infusion in the treatment of TE patients31. In 2021 Mouanness et al. performed a literature review in PubMed of in vitro, animal, and human studies, as well as abstracts presented at national conferences, and indicated that PRP might be beneficial for improving endometrial thickness and receptivity8. However, a recent review summarized by Stefanović et al. has demonstrated the main drawbacks of PRP are not enough data on safety and the lack of uniformity in PRP preparation methods, which may provide optimal standardized quality and quantity of PRP product32,33. Nevertheless, high-quality prospective clinical trials with large numbers of patients are necessary to confirm its effectiveness, and whether PRP is beneficial and safe in women trying to become pregnant via assisted reproductive technology34–37.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to compare transcriptional changes in the endometrium before and after PRP therapy. scRNA-seq was utilized to analyse paired endometrial samples and depict transcriptomic changes. Based on diverse markers of different cell types, the cell cluster results revealed changes in the numbers of various cells. The results of the GO and KEGG analyses revealed that these cells could be classified into 3 categories: stromal cell niches, epithelial cell niches and immune cell niches. With respect to the stromal cell niches of Str, pStr and Peri cells, the proportion of pStr cells increased and exhibited the enrichment of the cell cycle phase transition and nuclear division, which may indicate their synthesis function. In the Cili_Epi, Endo, LE and Lymph cells present in epithelial cell niches, although various proportions of changes were observed, the enrichment of cell projection assembly, ncRNA processing, and blood vessel morphogenesis may indicate the activation of epithelial cell proliferation. For the Mac, CD8+, CD4+ T and NK cells in the immune cell niches, the increased proportions of these cells and enrichment of immune effector processes and T-cell activation may determine the positive roles of local immune responses.

The re-epithelization of human endometrium relies not only on complex crosstalk between stromal and epithelial cells, but also on the migration and differentiation of epithelial progenitors and multilineage differentiation potential of endometrial mesenchymal populations1. Lv et al. reported that the numbers of Str, pStr and epithelial cells were reduced, along with a subpopulation of pStr cells whose cell cycle signalling pathways were compromised in TE patients17. Conversely, our current study revealed that PRP therapy increased the proportion of pStr cells via the activation of cell cycle signalling pathways. In addition, the CytoTRACE analysis suggested that high-stemness were more common in pStr or Str cells, while much greater stemness were present among GE and LE cells. These results inevitably demonstrate that PRP therapy may activate regenerative seed cells via stored cytokines and various growth factors38. Furthermore, Lv et al. investigated whether stromal cells of TE might be able to differentiate into epithelial cells through MET, which is an important contributor to endometrial epithelial repair39. Cellular transdifferentiation between stromal and epithelial cell types in the human endometrium appears to play key roles in repopulating the endometrium40,41. Kirkwood et al. reported that stromal fibroblasts could undergo MET and become incorporated into the re-epithelialized luminal surface of repaired tissue41. Our current research used GSVA and calculated those epithelial cells of TE showed relatively high expression of VIM and low expression of KRT8. However, PRP infusion improved the re-epithelialization condition, whereas epithelial cells from post-PRP patients presented relatively lower expression of VIM but similar or higher expression of KRT8. Maintaining healthy endometrial tissue via MET/EMT control is important for receptivity, since it allows the phenotypic and functional necessary for regeneration, embryo implantation and decidualization39. If MET/EMT processes do not function properly, the endometrial tissue may change to pathologic condition such as endometriosis, endometrial fibrosis, and certain endometrial cancers42,43. Yun et al. revealed higher E-cadherin and lower N-cadherin expression in the endometria of women with infertility-related diseases, suggests a resistance to endometrial receptivity and potentially reflects MET properties44. Additionally, Crizotinib is reported to be a small molecule inhibitor that targets MET, that is a well-known prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic target within cervical cancer45.

The most surprising finding of our present study was the increased number of immune cells, especially macrophages, after PRP therapy. Macrophages are natural immune cells that are widely distributed throughout all tissues, respond to physiological and pathological changes, and keep individuals healthy via the phagocytosis and digestion of bacteria, viruses, and cellular debris46. They also play vital roles in homeostasis, antigen presentation, inflammation resolution and tissue remodelling29. Macrophages are highly plastic and heterogeneous populations that can be broadly characterized into two distinct phenotypes: M1 and M247. M1-type macrophages are generally considered proinflammatory and mediate inflammatory responses. In contrast, M2-type macrophages are responsible for anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects48. Considering the M1/M2 ratio, we further investigated the polarization and development of macrophages in paired samples. The results revealed a high M1/M2 ratio (2.11 vs. 0.70) with enrichment of typical M1 pathways after PRP therapy. Traditionally, the M1 type and its inflammatory reaction are believed to be detrimental, but increasing evidence suggests that transient M1 macrophage polarization in the early inflammatory stage may be crucial for tissue regeneration47. Cytokines secreted by the M1 type may recruit stem cells to the injury site of the endometrium and promote their growth. According to the trajectory analysis, both the M1 and M2 phenotypes were active in the post-PRP tissue samples, and several signalling pathways regulating macrophage polarization were activated, with the top pathway identified as the VEGF pathway. Numerous studies have indicated that macrophages can participate in angiogenesis via the secretion of angiogenic factors48. M1 macrophages can recruit vascular endothelial progenitor cells to the wound site49. M2 macrophages may initiate angiogenesis by producing VEGF, thus providing nutrients and oxygen50.

Apparently, the results of the in silico evaluation must be validated through analyses of expression in vivo14. The results of IHC staining revealed that PRP therapy clearly increased cell stemness and epithelial marker expression, and stronger staining for STRO-1 with SDF-1 and KRT8 plus E-cad proteins was detected in endometrial tissue. Moreover, strong iNOS staining and weak Arg1 staining were observed in post-PRP tissue samples, indicating the early inflammatory stage of the human endometrium. CD31, a specific marker for vascularization, was obviously located in the epithelial lining and stromal area compared with that in samples from TE patients.

Our current study has several inevitable limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small. Although the average endometrial thickness increased in these 10 patients with TE, some individuals still failed to reach adequate thickness, leading to the forfeiture of their embryo transfer opportunities. Expanding the sample size and obtaining a sufficient number of clinical cases is a critical objective for our future research. Second, long-term follow-up data, such as pregnancy and neonatal outcomes, are currently unavailable. Such data would provide more comprehensive and meaningful insights into the efficacy of the PRP treatment. Third, while immunohistochemistry confirmed the expression of markers associated with various signalling pathways, additional techniques such as protein array or proteomic analysis should be employed to further investigate protein-level changes. These methods could provide a more accurate reflection of the cellular and molecular events described. Finally, the inclusion of a control group—either placebo or non-intervention—is essential to evaluate placebo and procedural effects. In subsequent studies, we plan to establish appropriate control groups to distinguish specific changes induced by PRP from those influenced by external factors or the procedure itself.

Conclusions

In summary, our current study is the first to reveal the effects of autologous PRP infusion on treating TE patients via a transcriptomic analysis, and our results suggest the underlying mechanism involves three aspects that need to be addressed: the efforts of epithelial or stromal stem cells to contribute to re-epithelization, the contribution of MET to cellular transdifferentiation, and the polarization of macrophages that regulate local immune responses. These are consistent with the latest publication regarding endometriosis therapy51. Although the long-term effects of PRP require further investigation, this analysis offers valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying PRP treatment in endometrial regeneration. Moving forward, we will focus more closely on the cellular and molecular events identified in this study to better understand the roles of specific PRP bioactive components. By precisely targeting and modulating the relevant pathways, we aim to mitigate potential risks and enhance clinical outcomes for TE patients undergoing PRP therapy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Yali Hu team for sharing the scRNA-seq data from normal and TE patients. We also thank Dr. Zhuolin Li for analysing and interpreting these sequencing data.

Abbreviations

- TE

Thin endometrium

- PRP

Platelet-rich plasma

- scRNA-seq

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- ET

Endometrial thickness

- HE

Haematoxylin and eosin

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- Str

Stromal cells

- Mac

Macrophages

- t-SNE

T-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding

- UMAP

Uniform manifold approximation and projection

- GO

Gene ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- CytoTRACE

Cellular trajectory reconstruction analysis using gene counts and expression

- pStr

Proliferating stromal cells

- GE

Glandular cells

- LE

Luminal cells

- GSVA

Gene set variation analysis

- MET

Mesenchymal‒epithelial transition

- IVF

In vitro fertilization

- RIF

Recurrent implantation failure

Author contributions

J.Q. and J.L. designed the study, supervised the project, reviewed and revised the manuscript; J.Z. performed the experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; H.L. helped collect and process the clinical tissue samples; W.G. guided the application of PRP preparation for treatment; and F.Q. helped analyze the data. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangzhou Health Science and Technology Project (grant no. 20221A010057) and the China Scholarship Council (no. 202206385009).

Data availability

The scRNA-seq data from normal and TE patients was deposited in the database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA730360. The datasets used and analysed during the current study for TE patients before and after PRP therapy are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (2021135, approver Yonghong Lai). Each participant had signed the consent form for the use of personal data for research use and publication.

Consent for publication

All the authors agree to publish this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jingjing Quan, Email: quanjj3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Jianqiao Liu, Email: ljq88gz@163.com.

References

- 1.Ang, C. J., Skokan, T. D. & McKinley, K. L. Mechanisms of regeneration and fibrosis in the endometrium. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol.39, 197–221 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng, T. et al. Cytoskeletal and inter-cellular junction remodelling in endometrial organoids under oxygen-glucose deprivation: A new potential pathological mechanism for thin endometria. Hum. Reprod.39, 1778–1793 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saad-Naguib, M. H., Kenfack, Y., Sherman, L. S., Chafitz, O. B. & Morelli, S. S. Impaired receptivity of thin endometrium: Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne)14, 1268990 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu, T., He, B. & Xu, X. Repairing and regenerating injured endometrium methods. Reprod. Sci.30, 1724–1736 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu, S. et al. Protective effects of engineered Lactobacillus crispatus strains expressing G-CSF on thin endometrium of mice. Hum. Reprod.39, 2305–2319 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li, C. et al. A dopamine-modified hyaluronic acid-based mucus carrying phytoestrogen and urinary exosome for thin endometrium repair. Adv. Mater.36, e2407750 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii, S. & Oguchi, T. The number of previous implantation failures is a critical determinant of intrauterine autologous platelet-rich plasma infusion success in women with recurrent implantation failure. Reprod. Med. Biol.23, e12565 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mouanness, M., Ali-Bynom, S., Jackman, J., Seckin, S. & Merhi, Z. Use of Intra-uterine Injection of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for endometrial receptivity and thickness: A literature review of the mechanisms of action. Reprod. Sci.28, 1659–1670 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qi, J. et al. Locationally activated PRP via an injectable dual-network hydrogel for endometrial regeneration. Biomaterials309, 122615 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu, X. et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of thin endometrium: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth24, 567 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catalini, L. et al. In vivo effect of vaginal seminal plasma application on the human endometrial transcriptome: A randomized controlled trial. Mol. Hum. Reprod.30, gaae017 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yadalam, P. K., Arumuganainar, D., Natarajan, P. M. & Ardila, C. M. Artificial intelligence-powered prediction of AIM-2 inflammasome sequences using transformers and graph attention networks in periodontal inflammation. Sci. Rep.15, 8733 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroda, K. et al. Transcriptomic profiling analysis of human endometrial stromal cells treated with autologous platelet-rich plasma. Reprod. Med. Biol.22, e12498 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo, J. et al. Single-cell RNA analysis of chemokine expression in heterogeneous CD14+ monocytes with lipopolysaccharide-induced bone resorption. Exp. Cell. Res.420, 113343 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih, A. J. et al. Single-cell analysis of menstrual endometrial tissues defines phenotypes associated with endometriosis. BMC. Med.20, 315 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, X. et al. Single-cell transcriptome analysis uncovers the molecular and cellular characteristics of thin endometrium. FASEB J.36, e22193 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lv, H. et al. Deciphering the endometrial niche of human thin endometrium at single-cell resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.119, e2115912119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu, L., Fan, Y., Wang, J. & Shi, R. Dysfunctional intercellular communication and metabolic signaling pathways in thin endometrium. Front. Physiol.13, 1050690 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu, X. et al. Varied cellular abnormalities in thin vs normal endometrium in recurrent implantation failure by single-cell transcriptomics. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol.22, 90 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, Y. et al. Unresponsive thin endometrium caused by Asherman syndrome treated with umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells on collagen scaffolds: A pilot study. Stem. Cell. Res. Ther.12, 420 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huniadi, A. et al. Autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) efficacy on endometrial thickness and infertility: A single-centre experience from Romania. Medicina (Kaunas)59, 1532 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic. Acids. Res.53, 672–677 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein. Sci.28, 1947–1951 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gulati, G. S. et al. Single-cell transcriptional diversity is a hallmark of developmental potential. Science367, 405–411 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, Z. et al. Integrated analysis of single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing data reveals a pan-cancer stemness signature predicting immunotherapy response. Genome Med.14, 45 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu, X. et al. Integrating single-cell RNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics reveals MDK-NCL dependent immunosuppressive environment in endometrial carcinoma. Front. Immunol.14, 1145300 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarsenova, M. et al. Endometriotic lesions exhibit distinct metabolic signature compared to paired eutopic endometrium at the single-cell level. Commun. Biol.7, 1026 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang, J. et al. Circulating IL6 is involved in the infiltration of M2 macrophages and CD8+ T cells. Sci. Rep.15, 8681 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu, Q. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the effects of high-fat diet on oocyte and early embryo development in female mice. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol.22, 105 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, Y., Tang, Z. & Teng, X. New advances in the treatment of thin endometrium. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne)15, 1269382 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stefanović, M. et al. The effect of autologous platelet rich plasma on endometrial receptivity: A narrative review. Medicina (Kaunas)61, 134 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurkan, N. & Alper, T. The effect of endometrial PRP on fertility outcomes in women with implantation failure or thin endometrium. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet.3, 1–10 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan, G. et al. Injectable GelMA hydrogel microspheres with sustained release of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of thin endometrium. Small20, e2403890 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaidakis, D., Papapanou, M. & Siristatidis, C. S. Autologous platelet-rich plasma for assisted reproduction. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.4, CD013875 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Artimani, T. et al. Effect of different concentrations of PRP on the expression of factors involved in the endometrial receptivity in the human endometrial cells from RIF patients compared to the controls. Reprod. Sci.31, 3870–3879 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, Y. et al. Menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells combining with platelet-rich plasma infusion in endometrium repair. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res.50, 2338–2345 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deane, J. A., Gualano, R. C. & Gargett, C. E. Regenerating endometrium from stem/progenitor cells: Is it abnormal in endometriosis, Asherman’s syndrome and infertility?. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol.25, 193–200 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patterson, A. L., Zhang, L., Arango, N. A., Teixeira, J. & Pru, J. K. Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition contributes to endometrial regeneration following natural and artificial decidualization. Stem. Cells Dev.22, 964–974 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Owusu-Akyaw, A., Krishnamoorthy, K., Goldsmith, L. T. & Morelli, S. S. The role of mesenchymal-epithelial transition in endometrial function. Hum. Reprod. Update25, 114–133 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirkwood, P. M. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing and lineage tracing confirm mesenchyme to epithelial transformation (MET) contributes to repair of the endometrium at menstruation. Elife11, e77663 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uchida, H. Epithelial mesenchymal transition in human menstruation and implantation. Endocr. J.71, 745–751 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spooner-Harris, M. et al. A re-appraisal of mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) in endometrial epithelial remodeling. Cell. Tissue Res.391, 393–408 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yun, B. S. et al. Endometrial E-cadherin and N-cadherin expression during the mid-secretory phase of women with ovarian endometrioma or uterine fibroids. J. Pers. Med.14, 920 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Varma, D. A. & Tiwari, M. Crizotinib-induced anti-cancer activity in human cervical carcinoma cells via ROS-dependent mitochondrial depolarization and induction of apoptotic pathway. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res.47, 3923–3930 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo, Q. & Qian, Z. M. Macrophage based drug delivery: Key challenges and strategies. Bioact. Mater.38, 55–72 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qiu, Y. et al. Macrophage polarization in adenomyosis: A review. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol.91, e13841 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gou, M., Wang, H., Xie, H. & Song, H. Macrophages in guided bone regeneration: Potential roles and future directions. Front. Immunol.15, 1396759 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang, L. et al. Surface modified small intestinal submucosa membrane manipulates sequential immunomodulation coupled with enhanced angio- and osteogenesis towards ameliorative guided bone regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. Appl.119, 111641 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, Y. et al. Injectable immunoregulatory hydrogels sequentially drive phenotypic polarization of macrophages for infected wound healing. Bioact. Mater.41, 193–206 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marečková, M. et al. An integrated single-cell reference atlas of the human endometrium. Nat. Genet.56, 1925–1937 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The scRNA-seq data from normal and TE patients was deposited in the database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA730360. The datasets used and analysed during the current study for TE patients before and after PRP therapy are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.