Abstract

Background and objectives

Bullying victimization is strongly associated with sleep quality issues in primary school students, yet the underlying mechanisms among these variables require further exploration. This study investigates the mediating role of mobile phone addiction and the moderating role of physical activity in the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality among primary school students, contributing to a deeper understanding of these psychological processes.

Methods

This study utilized a convenience sampling method to recruit 502 primary school students in 2023. The sample included 232 boys and 270 girls, with ages ranging from 10 to 12 years (mean age = 11.15 ± 0.62). Participants were recruited from specific region or school district to ensure a diverse representation of the target population. Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from both the students and their parents or guardians prior to data collection.

Results

Bullying victimization was significantly positively correlated with both sleep quality issues and mobile phone addiction. Additionally, mobile phone addiction was significantly positively correlated with sleep quality issues. The analysis confirmed that mobile phone addiction mediates the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality. Furthermore, physical activity was found to moderate the relationship between bullying victimization and mobile phone addiction.

Conclusions

This study elucidates the psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality among primary school students. Mobile phone addiction serves as a mediating factor, while physical activity acts as a moderating factor in the link between bullying victimization and mobile phone addiction. These findings underscore the importance of addressing mobile phone addiction and promoting physical activity as part of targeted interventions to improve sleep quality among primary school students.

Keywords: Bullying victimization, Sleep quality, Mobile phone addiction, Physical activity, Primary school students

Introduction

According to data from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, sleep is an indispensable component of daily human life. Along with diet and physical activity, sleep is considered one of the three fundamental pillars of health [1], and it is crucial for maintaining life and overall health [2]. However, research indicates that poor sleep quality is a significant public health issue among primary school students [3], and the prevalence of poor sleep quality in this group has been steadily increasing, with the onset age decreasing [4]. The incidence of sleep disorders among adolescents is estimated to be approximately 25–30% [5], and general sleep problems, such as insufficient sleep, affect up to 80% of this group [6]. In the United States, recommendations for adolescent sleep duration range from 8 to 10 h, while primary school students are advised to get 7 to 9 h of sleep [7]. Despite these recommendations, reports from many countries indicate that primary school students’ actual sleep duration is often below these guidelines [8, 9], and sleep duration has decreased over the past few decades. Sleep, as an essential physiological activity, is closely related to the growth and development of primary school students [10]. It is a neurophysiological process that plays a critical role in vital biological pathways essential for brain and body health [11]. Adolescence is considered the second critical developmental phase, following early childhood, for fundamental learning and neuroplasticity [12]. During this period, the brain undergoes significant restructuring and development, which gradually matures primary school students’ cognitive abilities, emotional regulation, and behavioral patterns [13]. However, this developmental stage also makes primary school students more vulnerable to the effects of poor sleep quality. Sleep is crucial for neuroplasticity, memory consolidation, and the development of learning abilities. Poor sleep quality can disrupt these vital physiological and psychological processes, negatively impacting cognitive development, emotional health, and overall growth. These impacts include heightened risks of anxiety and depression [14], aggression [15], cognitive function changes [16], and suicidal behaviors [17], technology addiction [18, 19]. Based on the above overview, there is an urgent need to explore the various factors influencing primary school students’ sleep quality. Such research will not only help identify key risk factors contributing to poor sleep but also provide scientific evidence for developing effective intervention strategies.

Bullying victimization and sleep quality

The factors contributing to poor sleep quality are diverse and complex. Among these factors, bullying victimization is closely linked to sleep quality [20, 21, 22]. Bullying victimization is a major psychosocial predictor of mental health problems [23, 24, 25] and poor lifestyle habits [26], and it is also considered a significant antecedent of poor sleep quality [27]. Bullying victimization refers to the repeated, intentional attacks (including physical, verbal, relational, or social attacks) that children or primary school students experience over time, resulting in a power imbalance between the perpetrator and the victim [28]. A meta-analysis shows that the prevalence of bullying victimization among primary school students is 36% [29], and 13.13% of primary school students in China have experienced bullying victimization [30]. A recent study reported that 36% of females and 24% of males frequently experience bullying victimization [31]. Studies indicate that the prevalence of bullying victimization varies between 6.3% and 45.2% across different countries, suggesting that bullying victimization is a widespread issue among primary school students [32, 33]. Moreover, bullying victimization globally has a similar impact on the health of primary school students and appears to be associated with sleep quality [34]. Bullying victimization is one of the most common and concerning adversities among primary school students [35]. Victims of bullying are at greater risk for physical, cognitive, and psychological health issues [36], particularly in terms of anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and suicide rates [23, 25]. Children who are frequently bullied at school are more likely to experience enuresis and sleep difficulties [37], victims of bullying tend to have lower sleep quality [38] and are more likely to use sleeping pills [39]. As proposed by rumination theory, rumination refers to the repetitive thinking about negative events or emotional experiences without taking effective coping actions [40]. Victims of bullying are prone to entering a rumination state at night, constantly recalling the bullying incidents they experienced during the day. This repeated thinking can lead to sustained psychological arousal, making it difficult for them to relax and fall asleep. The ongoing psychological arousal also increases the frequency of nighttime awakenings, leading to more light sleep, which ultimately reduces overall sleep quality [41]. Therefore, a significant positive correlation is hypothesized to exist between bullying victimization and sleep quality among primary school students (H1).

The mediating effect of mobile phone addiction

In the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality in primary school students, mobile phone addiction may serve as an important mediating factor. Bullying victimization may not only directly affect the victim’s sleep quality but also indirectly influence it through mediating variables such as mobile phone addiction. Mobile phone addiction is a new manifestation of internet addiction in the smartphone era, characterized by a behavioral addiction to excessive mobile phone use [42]. The association between cyberbullying and mobile phone addiction is a complex socio - psychological phenomenon that has garnered widespread attention in recent years [43]. Several studies have found that individuals who experience bullying victimization may resort to excessive mobile phone use as a means of escaping reality, thereby developing mobile phone addiction [44, 45]. This behavior may serve as a coping strategy to alleviate the negative emotions and stress caused by cyberbullying [24, 46]. Primary school students who are highly dependent on smartphones and spend substantial time online are often victims of cyberbullying. Exposure to such online environments subjects them to cyberbullying-related threats [47]. Studies show that the more stressful life events an individual experiences, the more severe their mobile phone addiction becomes [48]. According to General Strain Theory, stressful life events reduce an individual’s positive stimuli and lead to problem behaviors [49]. Cyberbullying, as a daily stressor, can also trigger mobile phone addiction [50]. Research by Kim et al. found that excessive mobile phone and internet use due to uncontrollable cravings is a risk factor for cyberbullying [51]. This finding is supported by a cross-sectional study that reported a positive association between high levels of mobile phone addiction and cyberbullying involvement [52]. These findings collectively indicate a significant correlation between cyber-victimization and addictive behaviors [53] with gender and emotional factors acting as moderators [54]. By 2022, the number of minor internet users had exceeded 193 million, and the trend of younger age groups engaging with the internet is evident. Over the past five years, the internet penetration rate among primary school students has increased from 89.5 to 95.1%. Mobile phones have become the primary tool for primary school students to engage in online activities. Research indicates that poor sleep quality over the long term can affect both physical and mental health, while mobile phone and internet addiction negatively impacts sleep quality. As mobile phone addiction levels increase, sleep quality continues to deteriorate [55]. Controlling excessive mobile phone use can help improve sleep quality [56]. Both domestic and international studies show that mobile phone addiction has become a significant factor contributing to insomnia. Improving sleep quality can help alleviate mobile phone addiction in primary school students [57]. Therefore, mobile phone addiction mediates the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality (H2).

The moderating effect of physical activity

The exercise environment refers to the atmosphere created by the surrounding people during physical activity [58]. Physical exercise can improve health, enhance peer relationships, and increase social-emotional skills [59]. Existing studies have shown that physical exercise can help mitigate mobile phone addiction. Physical exercise is a direct negative predictor of mobile phone addiction among university students, and it can also indirectly influence mobile phone addiction through psychological distress [19]. Moreover, physical exercise can improve students’ mental health and foster innovative behaviors [60, 61, 62, 63, 64]. A study examining the relationship between mobile phone addiction tendencies and physical exercise among university students found that engaging in physical activity promotes direct social interaction, enhances social skills, and reduces feelings of loneliness. The pleasure derived from exercise helps reduce anxiety, depression, and stress, thereby improving mood [65]. Regular physical activity also enhances cognitive function [66], self-esteem, and self-efficacy, which in turn increases individual happiness [67]. Moreover, physical activity, as a positive coping strategy, may exert a moderating effect on the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality through multiple mechanisms. From a physiological perspective, physical activity promotes the secretion of neurotransmitters such as endorphins, which can improve mood states and attenuate the negative emotional responses associated with bullying victimization, thereby indirectly enhancing sleep quality [68]. From a psychological standpoint, engaging in physical activity can enhance an individual’s self-efficacy and self-esteem, enabling them to confront bullying victimization with greater confidence and reducing the anxiety and depressive symptoms that stem from it, thus contributing to better sleep. Additionally, physical activity provides a context for social support, where individuals can make friends and receive care and support from others [69]. This social support plays a significant role in alleviating the psychological stress associated with bullying victimization, thereby positively influencing sleep quality. Therefore, physical exercise is hypothesized to moderate the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality, as well as the mediating effect of mobile phone addiction (H3).

Current research

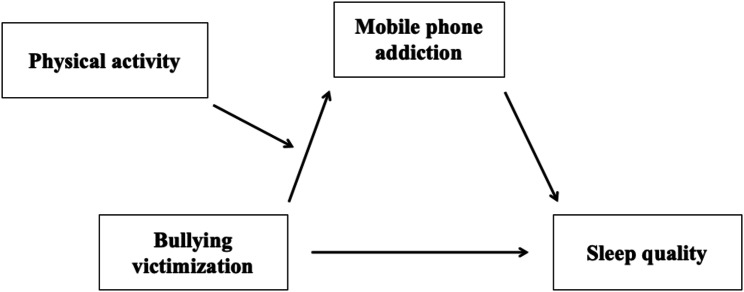

Based on the above discussion, the present study constructed a moderated mediation model (see Fig. 1) to examine the pathways and mechanisms through which mobile phone addiction and physical activity influence the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality. Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized a mediation model

H1

There is a significant positive correlation between bullying victimization and sleep quality among primary school students.

H2

Mobile phone addiction mediates the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality.

H3

Physical activity moderates the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality, as well as the mediating effect of mobile phone addiction.

Methods

Participants

Convenience sampling was employed in December 2023 to recruit 535 primary school students from two elementary schools in the Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Western Hunan for this study. The sample comprised 270 girls (54%) and 232 boys (46%), with ages ranging from 10 to 12 years, average age of 11.15 years (SD = 0.62). A total of 502 valid questionnaires were collected, yielding an effective response rate of 93.83%. Prior to the survey, homeroom teachers informed the guardians of the participants about the content and purpose of the research. All participants took part voluntarily, with informed consent obtained from their guardians. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the authors’ institution (Approval No. JSDX-2023-0034).

In the survey, researchers provided participants with an overview of the study’s main objectives, data confidentiality, and the intended use of the data. Participants were reminded that their involvement was voluntary and that there was no risk associated with participating. The survey was administered in paper format on a class-by-class basis. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) students enrolled in Grades 5 and 6 of the participating schools and (2) basic reading and writing abilities sufficient to complete the questionnaire independently. Upon completion of data collection, a thorough review of the dataset was conducted to identify the location and extent of missing data. This study used paper-based questionnaires. To ensure data quality, responses with missing data were excluded from the final dataset. This approach was adopted to minimize potential bias, as incomplete responses might indicate inattentive participation, which could affect the validity of the findings.

Measures

If a construct has been well-defined in previous research, it can be considered reliably measurable. A key objective of construct measurement is to ensure that the instrument captures the full conceptual domain of the target construct while avoiding the inclusion of irrelevant elements [70]. Additionally, given the academic demands placed on participants, the potential instability of paper questionnaires, and the need to minimize disruptions to students’ learning and teachers’ instructional schedules [71], this study employed concise yet comprehensive measurement tools to assess sleep quality and bullying victimization. Using shorter measurement instruments offers several advantages, including reducing participants’ cognitive and time burden [72], minimizing response bias [73], enhancing participant satisfaction [74], and streamlining subsequent data processing [75].

Bullying victimization

This study uses a one-question measure of bullying victimization. This item was specifically designed to define bullying victimization as “repeated and frequent negative behavior exhibited by others under conditions of unequal power or status, such as hitting, kicking, shoving, threatening, mocking, insulting, ostracizing, spreading rumors, or sending harmful electronic messages. Actions carried out mutually or in a friendly/joking manner do not qualify as bullying” [76, 77]. Participants were asked to recall their experiences over the past 90 days and respond using a five-point scale (0 = never, 1 = once a month, 2 = two to three times a month, 3 = once a week, 4 = several times a week, 5 = almost daily). This measure has been validated and utilized in previous studies [78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85].

Sleep quality

The instrument used in this study was adapted from Snyder’s research [86] and refined based on the National Health Survey results [87, 88]. Specifically, the sleep quality assessment tool was modified to better suit the context of this study. The refined tool was then employed to collect data for this research. Sleep quality was assessed using two items: “In the past 30 days, how often did you (1) have trouble falling asleep, (2) feel that you did not get enough sleep or rest?” Responses were scored on a scale from 1 (less than once a month) to 4 (almost always). Higher scores on the sleep quality measure indicate more frequent sleep problems [87]. This sleep quality assessment tool has been widely used in previous studies [89, 90].

Mobile phone addiction

We adopted the Chinese-translated version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale, validated by Xiang et al. [91]. This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity among Chinese populations. The total score ranges from 10 to 60, with higher scores indicating a greater tendency toward mobile phone addiction. In this study, the scale’s Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.838.

Physical activity

The Physical Activity Rating Scale − 3 (PARS-3), adapted by scholar Liang Deqing in 1994 [92], was employed to assess physical exercise levels. This scale comprises three dimensions: exercise duration, exercise intensity, and exercise frequency (e.g., “How many times do you engage in the aforementioned physical activities per month?“). The PARS-3 includes three subscales: exercise intensity, exercise frequency, and exercise duration, with a total of three items. It uses a 5-point Likert scale for scoring. The calculation method is as follows: Physical Activity Score = Exercise Intensity × (Exercise Duration − 1) × Exercise Frequency. The total score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater physical activity levels. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the PARS-3 was 0.867, indicating good internal consistency and reliability.

Data processing and analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0. A test for common method bias was first conducted, with a threshold of less than 40% indicating an absence of significant bias [93]. Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were conducted for demographic characteristics and key variables. Primary data were standardized prior to further analysis. To test our hypotheses, we used the PROCESS macro (Model 4 and 7) for SPSS to examine the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality, with mobile phone addiction as a mediating variable and physical activity as a moderating variable [94]. Bootstrap resampling (5,000 iterations) was used to evaluate model fit and estimate 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) to ensure robustness [95]. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Common method bias test

The results of the common method bias test revealed three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, with the first factor accounting for 22.60% of the total variance, below the 40% threshold. This indicates no significant common method bias in the data.

Descriptive analysis

As shown in Table 1, there were significant gender differences in bullying victimization (t = 3.89, p < 0.001), physical activity (t = 4.44, p < 0.001), and mobile phone addiction (t = 3.79, p < 0.01). Specifically, boys scored higher than girls in all three variables.

Table 1.

Describes the analysis

| Variables | Bullying victimization | Sleep quality | Physical activity | Mobile phone addiction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Sd | Mean | Sd | Mean | Sd | Mean | Sd | |

| Boys | 0.48 | 1.02 | 3.72 | 1.68 | 2.71 | 2.24 | 23.10 | 9.49 |

| Girls | 0.19 | 0.55 | 3.59 | 1.23 | 1.88 | 1.87 | 20.16 | 8.35 |

| t | 3.89*** | 1.02 | 4.44*** | 3.79*** | ||||

***: p < 0.001

Correlation analysis

Results in Table 2 show significant positive correlations between bullying victimization and both mobile phone addiction (r = 0.196, p < 0.001) and sleep quality (r = 0.303, p < 0.001). Additionally, mobile phone addiction was positively correlated with sleep quality (r = 0.226, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Correlation analysis

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bullying victimization | - | ||

| 2. Mobile phone addiction | 0.196*** | - | |

| 3. Sleep quality | 0.303*** | 0.226*** | - |

**: p < 0.01;***: p < 0.001

Mediation model test

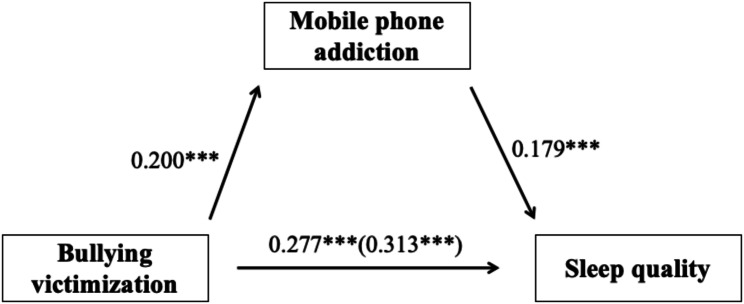

As shown in Table 3; Fig. 2, bullying victimization significantly and positively predicted sleep quality among primary school students (β = 0.313, p < 0.001). However, when the mediator was included in the model, the direct effect of bullying victimization on sleep quality remained significant (β = 0.277, p < 0.001). Additionally, in the mediation model, bullying victimization significantly and positively predicted mobile phone addiction among primary school students (β = 0.200, p < 0.001), which in turn significantly and positively predicted sleep quality (β = 0.179, p < 0.001). The specific proportions of the mediated effects are presented in Table 4. The detailed paths of the effect model are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 3.

Mediation model test

| Outcome variables | Predictor variables | β | SE | t | R² | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep quality | Bullying victimization | 0.313 | 0.044 | 7.191*** | 0.108 | 15.106*** |

| Mobile phone addiction | Bullying victimization | 0.200 | 0.044 | 4.529*** | 0.084 | 11.484*** |

| Sleep quality | Bullying victimization | 0.277 | 0.044 | 6.342*** | 0.137 | 15.845*** |

| Mobile phone addiction | 0.179 | 0.043 | 4.108*** |

*: p < 0.05; ***: p < 0.001

Fig. 2.

Mediation model

Table 4.

Mediation model path analysis

| Intermediate path | Effect size | SE | Bootstrap 95% CI | Proportion of mediating effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.313 | 0.044 | 0.228, 0.399 | |

| Total direct effect | 0.277 | 0.044 | 0.191, 0.363 | 88.50% |

| Total indirect effect | 0.036 | 0.012 | 0.014, 0.061 | 11.50% |

Moderated and mediation analysis

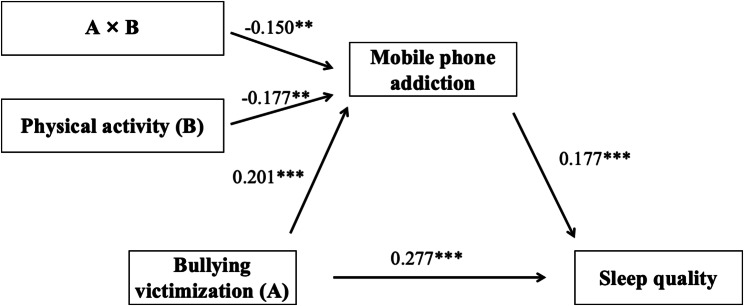

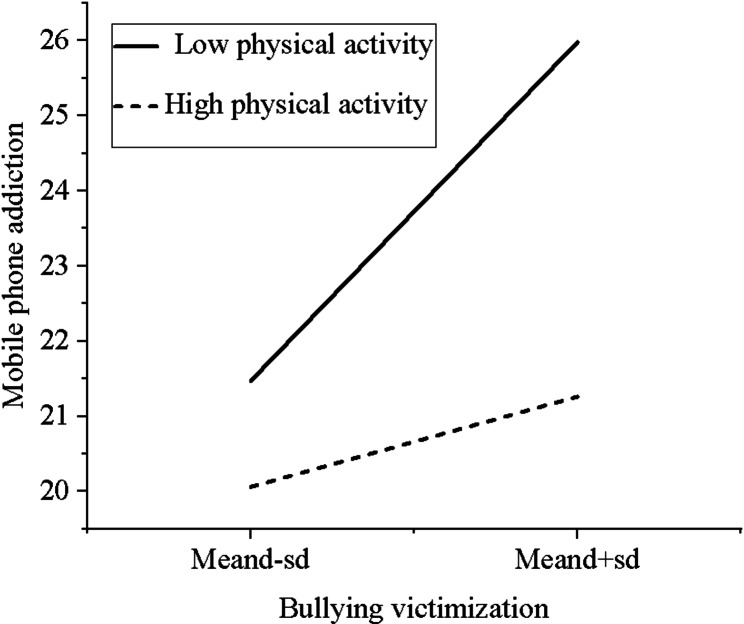

As shown in Table 5; Figs. 3 and 4, bullying victimization remained a significant predictor of mobile phone addiction among primary school students (β = 0.201, p < 0.001). Physical activity significantly predicted mobile phone addiction among primary school students (β =−0.117, p < 0.01). The interaction between bullying victimization and physical activity was also significant in predicting mobile phone addiction (β =−0.150, p < 0.01). Further analysis revealed that physical activity at both low and high levels negatively moderated the effect of bullying victimization on mobile phone addiction. Detailed pathways are shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

Table 5.

Moderated mediation model test

| Variables | Mobile phone addiction | Sleep quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Bullying victimization(A) | 0.201 | 0.044 | 4.574*** | 0.277 | 0.044 | 6.342*** |

| Physical activity(B) | −0.117 | 0.044 | −2.679** | |||

| A × B | −0.150 | 0.044 | −3.397** | |||

| Mobile phone addiction | 0.177 | 0.043 | 4.101*** | |||

| R² | 0.090 | 0.122 | ||||

| F | 12.266*** | 23.088*** | ||||

*: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001

Fig. 3.

Moderated mediation models (**: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001)

Fig. 4.

Simple slope diagram

Discussion

This study examines the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality among primary school students, as well as the mediating role of mobile phone addiction and the moderating effect of physical activity. The findings reveal a significant positive correlation between bullying victimization and sleep quality issues in primary school students. Mediation analysis indicates that bullying victimization directly impacts sleep quality and also exerts an indirect effect through mobile phone addiction. Moderation analysis further shows that physical activity can modulate the relationship between bullying victimization and mobile phone addiction, which, in turn, may influence sleep quality. These results offer insight into the psychological mechanisms underlying the impact of bullying victimization on sleep quality among primary school students.

The present study revealed a positive correlation between bullying victimization and sleep quality among primary school students, a finding that is corroborated by other similar studies [27, 38] and supports Hypothesis 1 (H1) of this research. Bullying victimization is defined as a situation where an individual is repeatedly and intentionally targeted by one or more peers over time [96], representing a significant and common source of stress, with an incidence rate of 10–35% [35]. The current findings align with the view that bullying acts as a social stressor that activates the stress response system, particularly the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [97]. The HPA axis regulates the body’s response to stress by releasing cortisol. Prolonged exposure to bullying may lead to HPA axis dysregulation, resulting in persistently elevated cortisol levels or disrupted circadian rhythms. Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, typically peaks in the early morning and declines gradually throughout the day. For individuals who experience bullying, this diurnal pattern may be disrupted, leading to elevated nighttime cortisol levels that interfere with normal sleep cycles. Sustained high cortisol levels can hinder sleep onset and quality, resulting in increased nocturnal awakenings and lighter sleep stages [98]. Additionally, victims of bullying often experience social exclusion and feelings of helplessness, which amplify psychological distress. Research shows that social pain activates brain regions involved in physical pain processing, such as the anterior cingulate cortex, thereby increasing nocturnal awakenings and impairing sleep quality [99]. Victims often lack social support and a sense of security [100], leading to nighttime anxiety and difficulty relaxing into sleep. This lack of social safety can heighten sensitivity to perceived threats, further prolonging sleep onset and reducing overall sleep quality. Furthermore, bullying victims are often subjected to a high-stress social environment that chronically activates the autonomic nervous system, particularly the sympathetic nervous system [101]. Prolonged sympathetic activation may extend the “fight-or-flight” response, causing heightened physical tension and disrupting normal sleep processes [102]. The autonomic nervous system comprises the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, and excessive sympathetic activity can lead to increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, and impaired thermoregulation. These physiological responses are closely associated with difficulty falling asleep, frequent nighttime awakenings, and lighter sleep stages [103]. Simultaneously, overactive sympathetic responses can suppress parasympathetic function, impeding relaxation and recovery, leading to chronic sleep insufficiency. In summary, the results of this study confirm the positive correlation between bullying victimization and sleep quality among primary school students (H1). Specifically, higher levels of bullying victimization are associated with higher sleep quality scores, which paradoxically indicate poorer sleep quality.

The results also show a significant positive correlation between bullying victimization and mobile phone addiction in primary school students, consistent with existing research [104]. The self-medication hypothesis can explain this phenomenon, suggesting that mobile phone addiction serves as a coping mechanism for alleviating negative emotions [105]. Bullying victims may use mobile phone activities as a strategy to manage the negative impacts of their experiences. Empirical studies support this view, demonstrating that bullying victimization can lead to mobile phone addiction [106]. Moreover, this study finds a significant negative correlation between mobile phone addiction and sleep quality. The mechanisms by which mobile phone addiction impairs sleep quality include psychological stimulation (prolonged internet use increasing arousal and delaying sleep onset), screen light exposure (suppressing melatonin secretion and affecting sleep), and physical discomfort (extended phone use causing cervical strain that impacts sleep quality) [107]. These results are supported by theories such as the sleep displacement hypothesis, arousal theory, and electromagnetic radiation theory. The sleep displacement hypothesis posits that mobile phone addiction compromises sleep quality by encroaching on rest time. Arousal theory suggests that phone content induces psychophysiological activation, leading to anxiety and insomnia. Electromagnetic radiation theory states that device radiation interferes with sleep structure, particularly deep and REM sleep, thereby reducing overall sleep quality [108]. Based on these theoretical underpinnings, the present study tested and confirmed the hypothesis that mobile phone addiction mediates the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality among primary school students (H2).

Physical activity is shown to play a protective role in the relationship between bullying victimization and sleep quality, aligning with the core tenets of the exercise performance integration model [109], supporting hypothesis H3. Physical activity, known for its benefits to mental and physical health, enhances positive emotions and reduces negative emotions [110]. Research indicates that physical activity can significantly reduce the likelihood of bullying victimization by promoting better physical health, optimizing peer interactions, and fostering social-emotional skills. It can also regulate physiological rhythms, facilitate faster sleep onset, and improve sleep quality [111]. Therefore, encouraging students to engage in regular physical activity may help mitigate sleep quality problems, improve peer relationships, and decrease the incidence of bullying. Based on these findings, the present study confirmed the hypothesis that physical activity acts as a protective factor between bullying victimization and sleep quality (H3).

This study delves into the complex interplay among bullying victimization, mobile phone addiction, sleep quality, and physical activity, revealing their intrinsic connections and interactions. The findings enrich theoretical understanding of the behavioral and psychological mechanisms linking mobile phone addiction to sleep quality and offer practical insights for intervention strategies. The study empirically demonstrates the mediating role of mobile phone addiction between bullying victimization and sleep quality and clarifies the moderating effect of physical activity, providing new theoretical support for identifying risk factors. In particular, schools and families should pay close attention to adolescents who have experienced adverse life events such as childhood maltreatment [112, 113, 114, 115], bullying, and family conflict, as well as those who frequently exhibit negative emotions or possess specific personality traits [116, 117]. These factors not only increase the risk of technology addiction but also contribute to poorer sleep quality. Considering the cumulative effects of these risk factors, it is crucial to implement targeted protective interventions. These may include offering stable family and peer support to strengthen adolescents’ sense of security and emotional belonging [118, 119, 120], encouraging physical activity to enhance both physical and mental health and improve emotional regulation [121, 122, 123], and providing cognitive training to boost adolescents’ ability to cope with negative emotions and stress. Practically, these results highlight the need to assess and intervene in mobile phone addiction among bullied primary school students to improve sleep quality. Intervention strategies should leverage physical activity’s regulatory effect, as it can effectively modulate the relationship between mobile phone addiction and sleep quality. Promoting physical activity may help students manage phone use better and prevent sleep issues.

Limitations

Despite its innovative aspects, this study is subject to several limitations. First, the use of self-reported data may introduce inaccuracies. Such data are prone to biases arising from subjective interpretations, memory errors, or incomplete information, which can affect the objectivity and reliability of the findings. For example, the assessment of bullying victimization and sleep quality using brief scales with fewer than three items, while widely utilized, may only capture a limited aspect of these constructs, potentially overlooking other important dimensions. The brevity of these scales also means that there is less internal consistency (reliability) to support the robustness of the findings, which may lead to greater variability in the results and impact the stability and reproducibility of the study outcomes. Future research should consider employing multi-item scales or more sophisticated measurement tools to further validate the conclusions drawn in this study. Additionally, longitudinal studies are necessary to explore the causal relationships between these variables. Second, the explained variance in some of the data was relatively low. This could be due to the inherent randomness or noise in the data, which may prevent the model from fully accounting for all variations, even if it captures certain patterns. Alternatively, there may be other unmeasured variables that influence the relationship between the constructs under investigation. Despite the modest explained variance, the model was still able to uncover significant trends and relationships. For example, a significant positive correlation was found between bullying victimization and sleep quality, providing valuable insights for future in-depth research. Third, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes the determination of causality. For instance, while a significant association was found between poor sleep quality and bullying victimization, it is not possible to rule out the possibility that poor sleep quality may increase an individual’s vulnerability to being bullied. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to better elucidate the causal relationships between these variables.

Conclusion

This study investigates the relationships among bullying victimization, sleep quality, mobile phone addiction, and physical activity among primary school students. It establishes the mediating role of mobile phone addiction and the moderating role of physical activity. The findings demonstrate a significant association between bullying victimization and sleep quality, with mobile phone addiction serving as a mediator. Physical activity alleviates the negative impact of bullying victimization on sleep quality. These results underscore the importance of improving sleep quality and preventing bullying, highlighting the need for targeted family and school-based interventions that promote physical activity and reduce mobile phone addiction to enhance sleep quality. This study has some limitations. First, its cross-sectional design prevents causal conclusions, so future research should use longitudinal designs to explore these relationships over time. Second, the sample was limited to primary school students in one region, so the findings may not apply to all populations. Future studies should include more diverse samples. Additionally, factors like parental involvement or socio-economic status should be explored in future research.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jinyin Peng’s revision, can be changed to this, in the end is their own growth or have a superior advice?

Author contributions

Jinyin Peng12345, Jiale Wang12345, Jiawei Chen1235, Geng Li1256, Hongqing Xiao1256, Yang Liu123456, Qing Zhang1235, Xiaozhen Wu1235, Yiping Zhang125.1 Conceptualization; 2 Methodology; 3 Data curation; 4 Writing - Original Draft; 5 Writing - Review & Editing; 6 Funding acquisition.

Funding

Hunan Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Foundation Project (General Project, ID: 22YBA150).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [our experimental team’s policy] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Biomedicine Ethics Committee of Jishou University before the initiation of the project (Grant number: JSDX-2023-0034). Informed consent was obtained from the participants and their guardians before the start of the program. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jinyin Peng and Jiale Wang have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Contributor Information

Hongqing Xiao, Email: 330928954@qq.com.

Yang Liu, Email: ldyedu@foxmail.com.

Qing Zhang, Email: qing.zhang@awf.gda.pl.

References

- 1.Shechter A, Grandner MA, St-Onge MP. The role of sleep in the control of food intake. AM J LIFESTYLE MED. 2014;8(6):371–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrington J, Lee-Chiong T. Basic biology of sleep. Dent Clin North Am. 2012;56(2):319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruce ES, Lunt L, McDonagh JE. Sleep in adolescents and young adults. CLIN MED. 2017;17(5):424–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopasz M, Loessl B, Hornyak M, Riemann D, Nissen C, Piosczyk H, Voderholzer U. Sleep and memory in healthy children and adolescents - a critical review. SLEEP MED REV. 2010;14(3):167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Impact of insomnia on future functioning of adolescents. J PSYCHOSOM RES. 2002;53(1):561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamura N, Okamura K. Social jetlag as a predictor of depressive symptoms among Japanese adolescents: evidence from the adolescent sleep health epidemiological cohort. SLEEP HEALTH. 2023;9(5):638–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, Hazen N, Herman J, Katz ES, Kheirandish-Gozal L, et al. National sleep foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. SLEEP HEALTH. 2015;1(1):40–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gradisar M, Gardner G, Dohnt H. Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. SLEEP MED. 2011;12(2):110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kocevska D, Lysen TS, Dotinga A, Koopman-Verhoeff ME, Luijk M, Antypa N, Biermasz NR, Blokstra A, Brug J, Burk WJ, et al. Sleep characteristics across the lifespan in 1.1 million people from the Netherlands, united Kingdom and united States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NAT HUM BEHAV. 2021;5(1):113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarokh L, Saletin JM, Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescence: physiology, cognition and mental health. NEUROSCI BIOBEHAV R. 2016;70:182–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Besedovsky L, Lange T, Haack M. The Sleep-Immune crosstalk in health and disease. PHYSIOL REV. 2019;99(3):1325–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agostini A, Centofanti S. Normal sleep in children and adolescence. CHILD ADOL PSYCH CL. 2021;30(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescents: the perfect storm. PEDIATR CLIN N AM. 2011;58(3):637–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A Systematic Review Assessing Bidirectionality between Sleep Disturbances, Anxiety, and Depression. SLEEP 2013;36(7):1059–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.GREGORY AM, O’CONNOR TG. Sleep problems in childhood: A longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(8):964–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowe CJ, Safati A, Hall PA. The neurocognitive consequences of sleep restriction: A meta-analytic review. NEUROSCI BIOBEHAV R. 2017;80:586–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peach HD, Gaultney JF. Sleep, impulse control, and sensation-seeking predict delinquent behavior in adolescents, emerging adults, and adults. J Adolesc HEALTH. 2013;53(2):293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Jin C, Zhou X, Chen Y, Ma Y, Chen Z, Zhang T, Ren Y. The chain mediating effect of anxiety and inhibitory control between bullying victimization and internet addiction in adolescents. SCI REP-UK. 2024;14(1):23350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Tan D, Wang P, Xiao T, Wang X, Zhang T. Physical activity moderated the mediating effect of self-control between bullying victimization and mobile phone addiction among college students. SCI REP-UK. 2024;14(1):20855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Geel M, Goemans A, Vedder PH. The relation between peer victimization and sleeping problems: A meta-analysis. SLEEP MED REV. 2016;27:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolke D, Lereya ST. Bullying and parasomnias: a longitudinal cohort study. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1040–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Liu Y, Xiao T, Pan M. The relationship between bullying victimization and adolescent sleep quality: the mediating role of anxiety and the moderating role of difficulty identifying feelings. Psychiatry. 2025. 10.1080/00332747.2025.2484147 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Moore THM, Kesten JM, López-López JA, Ijaz S, McAleenan A, Richards A, Gray S, Savović J, Audrey S. The effects of changes to the built environment on the mental health and well-being of adults: systematic review. HEALTH PLACE. 2018;53:237–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Peng J, Ding J, Wang J, Jin C, Xu L, Zhang T, Liu P. Anxiety mediated the relationship between bullying victimization and internet addiction in adolescents, and family support moderated the relationship. BMC PEDIATR 2025, 25(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wang J, Wang N, Qi T, Liu Y, Guo Z. The central mediating effect of inhibitory control and negative emotion on the relationship between bullying victimization and social network site addiction in adolescents. Front Psychol. 2025;15:1520404. 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1520404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Tu W, Jiang H, Liu Q. Peer victimization and adolescent mobile social addiction: mediation of social anxiety and gender differences. INT J ENV RES PUB HE 2022, 19(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.He Y, Chen SS, Xie GD, Chen LR, Zhang TT, Yuan MY, Li YH, Chang JJ, Su PY. Bidirectional associations among school bullying, depressive symptoms and sleep problems in adolescents: A cross-lagged longitudinal approach. J AFFECT DISORDERS. 2022;298(Pt A):590–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cikili-Uytun M, Efendi GY, Mentese-Babayigit T. The Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Handbook of anger, aggression, and violence. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2023. pp. 2343–55. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modecki KL, Minchin J, Harbaugh AG, Guerra NG, Runions KC. Bullying prevalence across contexts: a meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(5):602–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ran H, Cai L, He X, Jiang L, Wang T, Yang R, Xu X, Lu J, Xiao Y. Resilience mediates the association between school bullying victimization and self-harm in Chinese adolescents. J affect disorders. 2020;277:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Przybylski AK, Bowes L. Cyberbullying and adolescent well-being in England: a population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet child adolesc. 2017;1(1):19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasan MM, Fatima Y, Smith SS, Tariqujjaman M, Jatrana S, Mamun AA. Geographical variations in the association between bullying victimization and sleep loss among adolescents: a population-based study of 91 countries. Sleep med. 2022;90:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig W, Harel-Fisch Y, Fogel-Grinvald H, Dostaler S, Hetland J, Simons-Morton B, Molcho M, de Mato MG, Overpeck M, Due P, et al. A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. Int J public health. 2009;54(Suppl 2):216–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen TB, Steenberg LM, Palic S, Elklit A. A review of psychological factors related to bullying victimization in schools. Aggress violent beh. 2012;17(4):383–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, Thomas HJ, Sly PD, Scott JG. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J psychiatr. 2017;7(1):60–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Z, Zhang J, Zhang T, et al. The relationship between early adolescent bullying victimization and suicidal ideation: the longitudinal mediating role of self-efficacy. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):1000. 10.1186/s12889-025-22201-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Williams K, Chambers M, Logan S, Robinson D. Association of common health symptoms with bullying in primary school children. BMJ-BRIT Med J. 1996;313(7048):17–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shakoor S, M SZH, Gregory AM, Ronald A. The association between bullying-victimisation and sleep disturbances in adolescence: evidence from a twin study. J SLEEP Res. 2021;30(5):e13321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mei S, Hu Y, Sun M, Fei J, Li C, Liang L, Hu Y. Association between bullying victimization and symptoms of depression among adolescents: A moderated mediation analysis. INT J Env Res Pub HE 2021, 18(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Ehring T. Thinking too much: rumination and psychopathology. World psychiatry. 2021;20(3):441–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomsen DK, Mehlsen MY, Christensen S, Zachariae R. Rumination–relationship with negative mood and sleep quality.|.*34*34. Netherlands: Elsevier Science 2003;1293–301. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong F, Chiu S, Huang D. A model of the relationship between psychological characteristics, mobile phone addiction and use of mobile phones by Taiwanese university female students. COMPUT HUM BEHAV. 2012;28(6):2152–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Wang N, Liu P, Liu Y. Social network site addiction, sleep quality, depression and adolescent difficulty describing feelings: a moderated mediation model. BMC PSYCHOL. 2025;13(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marinoni C, Rizzo M, Zanetti MA. Fake profiles and time spent online during the COVID 19 pandemic: a real risk for cyberbullying? CURR PSYCHOL. 2024;43(32):26639–47. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lareki A, Martínez De Morentin JI, Altuna J, Amenabar N. Teenagers’ perception of risk behaviors regarding digital technologies. COMPUT HUM BEHAV. 2017;68:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo S, Zhang P, Lv S, Wang R. Effect of violence exposure on aggressive intervention in Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model. CHILD YOUTH SERV REV. 2024;163:107744. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen S, Liang K, Chen S, Huang L, Chi X. Association between 24-Hour movement guideline and physical, verbal, and relational forms of bullying among Chinese adolescents. ASIA-PAC J PUBLIC HE. 2023;35(2–3):168–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tu W, Nie Y, Liu Q. Does the effect of stress on smartphone addiction vary depending on the gender and type of addiction? BEHAV SCI-BASEL 2023;13(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Wachs S, Vazsonyi AT, Wright MF, Ksinan JG. Cross-National associations among cyberbullying victimization, Self-Esteem, and internet addiction: direct and indirect effects of alexithymia. FRONT PSYCHOL. 2020;11:1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Şimşek N, Şahin D, Evli M. Internet addiction, cyberbullying, and victimization relationship in adolescents: A sample from Turkey. J ADDICT NURS. 2019;30(3):201–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan TKH, Cheung CMK, Lee ZWY. Cyberbullying on social networking sites: A literature review and future research directions. Inf MANAGE-AMSTER. 2021;58(2):103411. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gámez-Guadix M, Borrajo E, Almendros C. Risky online behaviors among adolescents: longitudinal relations among problematic internet use, cyberbullying perpetration, and meeting strangers online. J BEHAV ADDICT. 2016;5(1):100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marinoni C, Rizzo M, Zanetti MA. Social Media, Online Gaming, and Cyberbullying during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediation Effect of Time Spent Online. Adolescents 2024.

- 54.Uçar HN, Çetin FH, Ersoy SA, Güler HA, Kılınç K, Türkoğlu S. Risky cyber behaviors in adolescents with depression: A case control study. J AFFECT DISORDERS. 2020;270:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao T, Pan M, Xiao X, Liu Y. The relationship between physical activity and sleep disorders in adolescents: a chain-mediated model of anxiety and mobile phone dependence. BMC Psychol. 2024;12(1):751. 10.1186/s40359-024-02237-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Sohn SY, Krasnoff L, Rees P, Kalk NJ, Carter B. The association between smartphone addiction and sleep: A UK Cross-Sectional study of young adults. FRONT PSYCHIATRY. 2021;12:629407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarhan AL. The relationship of smartphone addiction with depression, anxiety, and stress among medical students. SAGE OPEN MED. 2024;12:362889113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruiz-Ranz E, Asín-Izquierdo I. Physical activity, exercise, and mental health of healthy adolescents: a review of the last 5 years. Sports Med Health Sci 2024.7(3), 161–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. CLIN PSYCHOL REV. 2001;21(1):33–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao Z, Zhao S, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Chen C. Effects of Physical Exercise on Mobile Phone Addiction in College Students: The Chain Mediation Effect of Psychological Resilience and Perceived Stress. In International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health|.*19*19. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Peng J, Liu Y, Wang X, Yi Z, Xu L, Zhang F. Physical and emotional abuse with internet addiction and anxiety as a mediator and physical activity as a moderator. SCI REP-UK 2025;15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Liu Y, Xiao T, Zhang W, Xu L, Zhang T. The relationship between physical activity and Internet addiction among adolescents in western China: a chain mediating model of anxiety and inhibitory control. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2024;29(9):1602–1618. 10.1080/13548506.2024.2357694 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Liu Y, Jin Y, Chen J, et al. Anxiety, inhibitory control, physical activity, and internet addiction in Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24(1):663. 10.1186/s12887-024-05139-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Liu Y, Yin J, Xu L, Luo X, Liu H, Zhang T. The chain mediating effect of anxiety and inhibitory control and the moderating effect of physical activity between bullying victimization and internet addiction in chinese adolescents. J Genet Psychol. 2025. 10.1080/00221325.2025.2462595 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Zeng M, Chen S, Zhou X, Zhang J, Chen X, Sun J. The relationship between physical exercise and mobile phone addiction among Chinese college students: Testing mediation and moderation effects. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1000109. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1000109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Li G, Xia H, Teng G, Chen A. The neural correlates of physical exercise-induced general cognitive gains: A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. NEUROSCI BIOBEHAV R. 2025;169:106008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang MX, Wu AMS. Effects of smartphone addiction on sleep quality among Chinese university students: the mediating role of self-regulation and bedtime procrastination. ADDICT BEHAV. 2020;111:106552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hillman CH, McDonald KM, Logan NE. A review of the effects of physical activity on cognition and brain health across children and adolescence. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2020;95:116–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y, et al. Relationship between bullying behaviors and physical activity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 2024. 78: p. 101976.

- 70.Davidshofer KR, Murphy CO. Psychological Testing: Principles and Applications. 6th Edition, Pearson, Upper Saddle River. 2005.

- 71.Hosseinkhani Z, Hassanabadi HR, Parsaeian M, Karimi M, Nedjat S. Academic stress and adolescents mental health: A multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM) study in Northwest of Iran. J RES HEALTH SCI. 2020;20(4):e496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gogol K, Brunner M, Goetz T, Martin R, Ugen S, Keller U, Fischbach A, Preckel F. My questionnaire is too long! The assessments of motivational-affective constructs with three-item and single-item measures. CONTEMP EDUC PSYCHOL. 2014;39(3):188–205. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bergkvist L, Rossiter JR, American Marketing Association. The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs.|.*44*44. US:; 2007:175-184.

- 74.Postmes T, Haslam SA, Jans L: A single-item measure of social identification: reliability, validity, and utility. BRIT J SOC PSYCHOL 2013;52(4):597–617. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Zimmerman M, Ruggero CJ, Chelminski I, Young D, Posternak MA, Friedman M, Boerescu D, Attiullah N. Developing brief scales for use in clinical practice: the reliability and validity of single-item self-report measures of depression symptom severity, psychosocial impairment due to depression, and quality of life. J CLIN PSYCHIAT. 2006;67(10):1536–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Olweus D. Bullying at school: what we know and what we can do. Bullying at school: what we know and what we can do. Malden: Blackwell Publishing 1993;140. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Waasdorp TE, Mehari KR, Milam AJ, Bradshaw CP. Health-related risks for involvement in bullying among middle and high school youth.|.*28*28. Germany: Springer; 2019;2606–17. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koyanagi A, Oh H, Carvalho AF, Smith L, Haro JM, Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, DeVylder JE. Bullying victimization and suicide attempt among adolescents aged 12–15 years from 48 countries. J AM ACAD CHILD PSY. 2019;58(9):907–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang RX, Tang CM, Zhang M, Liu QJ, Tang WJ, Li SY, Li YC, Liu QL. The relationship between bullying and suicidal tendencies among adolescents in Western China: the mediating role of anxiety and the moderating role of loneliness. Modern Prev Medicine. 2023;84(1):231–243.

- 80.Badarch J, Chuluunbaatar B, Batbaatar S, Paulik E. Suicide attempts among School-Attending adolescents in Mongolia: associated factors and gender differences. INT J ENV RES PUB HE 2022;19(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Koyanagi A, Veronese N, Vancampfort D, Stickley A, Jackson SE, Oh H, Shin JI, Haro JM, Stubbs B, Smith L. Association of bullying victimization with overweight and obesity among adolescents from 41 low- and middle-income countries. PEDIATR OBES. 2020;15(1):e12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rahman MM, Rahman MM, Khan M, Hasan M, Choudhury KN. Bullying victimization and adverse health behaviors among school-going adolescents in South Asia: findings from the global school-based student health survey. DEPRESS ANXIETY. 2020;37(10):995–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith L, Jacob L, Shin JI, Tully MA, Pizzol D, López-Sánchez GF, Gorely T, Yang L, Grabovac I, Koyanagi A. Bullying victimization and obesogenic behaviour among adolescents aged 12 to 15 years from 54 low- and middle-income countries. PEDIATR OBES. 2021;16(1):e12700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hosozawa M, Bann D, Fink E, Elsden E, Baba S, Iso H, Patalay P. Bullying victimisation in adolescence: prevalence and inequalities by gender, socioeconomic status and academic performance across 71 countries. ECLINICALMEDICINE. 2021;41:101142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Khan MMA, Rahman MM, Islam MR, Karim M, Hasan M, Jesmin SS. Suicidal behavior among school-going adolescents in Bangladesh: findings of the global school-based student health survey.|.*55*55. Germany: Springer; 2020;1491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Snyder E, Cai B, DeMuro C, Morrison MF, Ball W. A new Single-Item sleep quality scale: results of psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic primary insomnia and depression. J CLIN SLEEP MED. 2018;14(11):1849–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.National Health Interview Survey.: research for the 1995–2004 redesign. Vital Health Stat 2 1999(126):1–119. [PubMed]

- 88.National Center for Health Statistics. Inadequate Sleep Optional Module. National Health Interview Survey 2000. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/surveillance.html

- 89.Waasdorp TE, Mehari KR, Milam AJ, Bradshaw CP. Health-related risks for involvement in bullying among middle and high school youth. J CHILD FAM STUD. 2019;28(9):2606–17. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Waasdorp TE, Mehari KR, Milam AJ, et al. Health-related risks for involvement in bullying among middle and high school youth[J]. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28:2606–17. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xiang, et al. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of the smartphone addiction scale in adolescents. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2019;27(5):6.

- 92.Liang. Stress level of college students and its relationship with physical exercise. Chin Mental Health J. 1994;8(1):2.

- 93.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J APPL PSYCHOL. 2003;88(5):879–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hayes AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Routledge 2018;(1).

- 95.Berkovits I, Hancock GR, Nevitt J. Bootstrap resampling approaches for repeated measure designs: relative robustness to sphericity and normality violations.|.*60*60. US: Sage; 2000;877–92. [Google Scholar]

- 96.McRae K, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation.|.*20*20. US: American Psychological Association. 2020;1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ouellet-Morin I, Odgers CL, Danese A, Bowes L, Shakoor S, Papadopoulos AS, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L. Blunted cortisol responses to stress signal social and behavioral problems among maltreated/bullied 12-Year-Old children. BIOL PSYCHIAT. 2011;70(11):1016–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nicolaides NC, Vgontzas AN, Kritikou I, Chrousos G. HPA Axis and Sleep. 2000.

- 99.Wu Z, Fang X, Yu L, Wang D, Liu R, Teng X, Guo C, Ren J, Zhang C. Abnormal functional connectivity of the anterior cingulate cortex subregions mediates the association between anhedonia and sleep quality in major depressive disorder. J AFFECT DISORDERS. 2022;296:400–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.The social outcast: Ostracism, social exclusion, rejection, and bullying. In The social outcast: Ostracism, social exclusion, rejection, and bullying. Edited by Williams KD, Forgas JP. von Hippel W. New York, NY, US: Psychology Press; 2005;366:366.

- 101.Holterman LA, Murray-Close DK, Breslend NL. Relational victimization and depressive symptoms: the role of autonomic nervous system reactivity in emerging adults. INT J PSYCHOPHYSIOL. 2016;110:119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li X, Tan WH, Zheng X, Dou D, Wang Y, Yang H. Effects of digital monitoring and immediate feedback on physical activity and fitness in undergraduates. EDUC INF TECHNOL. 2025;30:3743–3769.

- 103.Lambe LJ, Craig WM, Hollenstein T. Blunted physiological stress reactivity among youth with a history of bullying and victimization: links to depressive symptoms. J ABNORM CHILD PSYCH. 2019;47(12):1981–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cui K, Yip PSF. How peer victimization in childhood affects social networking addiction in adulthood: an examination of the mediating roles of social anxiety and perceived loneliness. DEVIANT BEHAV. 2024;45(11):1640–53. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hsieh Y, Shen AC, Wei H, Feng J, Huang SC, Hwa H. Associations between child maltreatment, PTSD, and internet addiction among Taiwanese students. COMPUT HUM BEHAV. 2016;56:209–14. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhao H, Li X, Zhou J, Nie Q, Zhou J. The relationship between bullying victimization and online game addiction among Chinese early adolescents: the potential role of meaning in life and gender differences. CHILD YOUTH SERV REV. 2020;116:105261. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hale L, Kirschen GW, LeBourgeois MK, Gradisar M, Garrison MM, Montgomery-Downs H, Kirschen H, McHale SM, Chang AM, Buxton OM. Youth screen media habits and sleep: Sleep-Friendly screen behavior recommendations for clinicians, educators, and parents. CHILD ADOL PSYCH CL. 2018;27(2):229–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hamblin DL, Wood AW. Effects of mobile phone emissions on human brain activity and sleep variables. INT J RADIAT BIOL. 2002;78(8):659–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dijkstra HP, Pollock N, Chakraverty R, Alonso JM. Managing the health of the elite athlete: a new integrated performance health management and coaching model. BRIT J SPORT MED. 2014;48(7):523–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li J, Huang Z, Si W, Shao T. The effects of physical activity on positive emotions in children and adolescents: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. INT J ENV RES PUB HE 2022;19(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Garcia-Hermoso A, Oriol-Granado X, Correa-Bautista JE, Ramírez-Vélez R. Association between bullying victimization and physical fitness among children and adolescents. INT J CLIN HLTH PSYC. 2019;19(2):134–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu Y, Shen Q, Duan L, Xu L, Xiao Y, Zhang T. The relationship between childhood psychological abuse and depression in college students: a moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24(1):410. 10.1186/s12888-024-05809-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 113.Liu Y, Duan L, Shen Q, Xu L, Zhang T. The relationship between childhood psychological abuse and depression in college students: internet addiction as mediator, different dimensions of alexithymia as moderator. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2744. 10.1186/s12889-024-20232-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 114.Liu Y, Wang P, Duan L, Shen Q, Xu L, Zhang T. The mediating effect of social network sites addiction on the relationship between childhood psychological abuse and depression in college students and the moderating effect of psychological flexibility. Psychol Psychother. 2025. 10.1111/papt.12580 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 115.Yang L, Tao Y, Wang N, Zhang Y, Liu Y. Child psychological maltreatment, depression, psychological inflexibility and difficulty in identifying feelings, a moderated mediation model. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):8478. 10.1038/s41598-025-92873-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 116.Wang A, Guo S, Chen Z, Liu Y. The chain mediating effect of self-respect and self-control on the relationship between parent-child relationship and mobile phone dependence among middle school students. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):30224. 10.1038/s41598-024-80866-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 117.Guo S, Zhang J, Wang A, Zhang T, Liu Y, Zhang S. The chain mediating effect of self-respect and self-control on peer relationship and early adolescent phone dependence. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):11825. 10.1038/s41598-025-96476-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 118.Liu Y, Jin C, Zhou X, et al. The mediating role of inhibitory control and the moderating role of family support between anxiety and Internet addiction in Chinese adolescents. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2024;53:165–170. 10.1016/j.apnu.2024.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 119.Yi Z, Wang W, Wang N, Liu Y. The relationship between empirical avoidance, anxiety, difficulty describing feelings and internet addiction among college students: a moderated mediation Model. J Genet Psychol. 2025. 10.1080/00221325.2025.2453705 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 120.Wang J, Ning W, Yang L, Zirui Z. Experiential avoidance, depression, and difficulty identifying emotions in social network site addiction among chinese university students: a moderated mediation model. Behav Inf Technol. 2025;2455406. 10.1080/0144929X.2025.2455406

- 121.Liu Y, Duan L, Shen Q, et al. The mediating effect of internet addiction and the moderating effect of physical activity on the relationship between alexithymia and depression. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):9781. 10.1038/s41598-024-60326-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 122.Shen Q, Wang S, Liu Y, Wang Z, Bai C, Zhang T. The chain mediating effect of psychological inflexibility and stress between physical exercise and adolescent insomnia. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24348. 10.1038/s41598-024-75919-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 123.Luo X, Liu H, Sun Z, et al. Gender mediates the mediating effect of psychological capital between physical activity and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):10868. 10.1038/s41598-025-95186-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [our experimental team’s policy] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.