Abstract

Background/Aim

Allicin is a small-molecule natural product found in garlic (Allium sativum). We previously showed that allicin inhibits ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) in vitro and induces apoptotic cell death in pediatric neuroblastoma (NB) cancer cell cultures. However, its potency as an anticancer agent in vivo has not been sufficiently explored.

Materials and Methods

In this study, we used cell proliferation assays, immunoblotting techniques, and light microscopy to study NB tumor cell cultures and human primary neonatal skin fibroblast control cells as well as a MYCN-amplified NB patient-derived xenograft (PDX) mouse tumor model to study the efficacy of allicin in vivo.

Results

Allicin strongly inhibits NB tumor cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner while non-cancerous human primary neonatal skin fibroblast control cells were largely unaffected. Importantly, two intra-tumoral injections of allicin over a two-week trial period significantly reduced the NB tumor burden in mice compared to controls (N=4-9 mice/group). Excised tumor tissues revealed that allicin treatment increased the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 protein levels, suggesting that in vivo, allicin increases p27Kip1-mediated G1/S cell cycle arrest.

Conclusion

Our findings warrant further preclinical development of allicin as a potential anticancer agent, especially for those types of cancers that are treatable by intra-tumoral injections, including neuroblastoma, glioblastoma, and medulloblastoma.

Keywords: Allicin, childhood cancer, in vivo antitumor activity, intra-tumoral injection, natural products, neuroblastoma, patient-derived xenograft (PDX)

Introduction

When tissues of garlic (Allium sativum) are damaged they release the natural product allicin, the pungent-smelling volatile organic sulfur compound (VOSC), that is the typical odor of fresh garlic (1,2) (Figure 1A and B). Allicin reacts reversibly with cellular thiols (R-SH) by making a disulfide bridge with an allyl group attached, i.e., R-SH becomes R-S-S-CH2-CH=CH2. The low molecular weight thiol glutathione and proteins containing cysteine are typical cellular targets for allicin and the disulfide bridge in the thioallylated products can be reduced back to thiols, thus making allicin effects reversible at sublethal levels. When cellular proteins are affected in this way their activity can become altered, and this makes allicin a dose-dependent biocide (1). The S-thioallylation reaction is central to allicin’s biological reactivity and, significantly, has also been shown to be performed by other compounds like allyl polysulfanes, found in aged garlic products and garlic oils where no allicin is present (3).

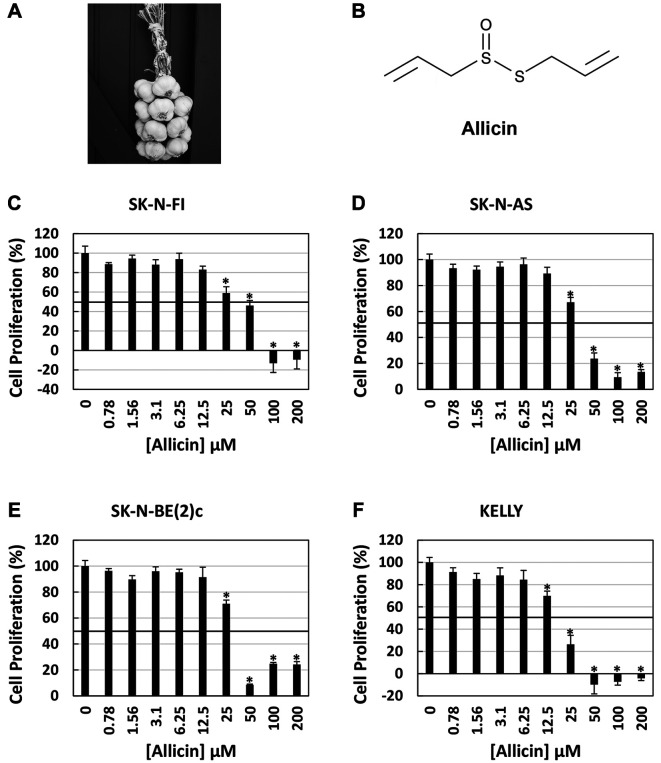

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent effect of allicin in neuroblastoma cell cultures. The chemical allicin (B) is a natural product extracted from garlic (A). Increasing concentrations of allicin inhibited NB cell proliferation in a dose dependent manner (C-F) with the greatest effect in SK-N-FI (C) and KELLY (F) cells. Data represents the mean±the standard deviation (S.D.) of a single experiment done in quadruplicate (N=4). *Statistically significant decrease in cell proliferation as compared to control (p=0.0001 or less).

MYCN gene amplification is often associated with high-risk neuroblastoma (NB), a fatal pediatric cancer, where relapsed tumors are virtually untreatable (4-6). The transcription factor MYCN directly activates the gene ornithine decarboxylase 1 (ODC1) (7,8) and the ODC protein is a rate-limiting enzyme in polyamine biosynthesis (9-11). We have been interested in the role of ODC and polyamines in NB for many years (12-20). High polyamines (putrescine, spermidine, spermine) trigger cell proliferation in NB as well as MYC-driven cancers (21-24). Difluoromethylornithine (DFMO, also known as Eflornithine, Ornidyl, and Iwilfin) is currently the only FDA-approved ODC inhibitor and has various challenges in the clinic, including high dosing requirements and rapid renal clearance. Because ODC has multiple cysteine residues, we tested whether human ODC was inhibited by allicin in vitro. We found allicin to be approximately 23,000 times more effective than DFMO, an astounding result that prompted us to also test the activity of allicin in NB cell cultures. Allicin indeed inhibits endogenous ODC activity, reduces polyamines, and induces apoptotic death in NB cell cultures (25).

The primary purpose of this study was to test the therapeutic activity in vivo, by injecting allicin directly into NB patient-derived xenograft (PDX) tumors.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals, reagents, and antibodies. Allicin was synthesized as previously described (26) and suspended in a 48 mM stock solution in water. Rabbit polyclonal antibody against PARP (#9542) and rabbit monoclonal antibody against p27Kip1 (#3686) was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Mouse monoclonal antibody against GAPDH (SC-47778) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to IRDye®680 RD (926-68071) and goat anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to IRDye®800CW (926-32210) were obtained from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE, USA). Protein assay dye reagent (#5000006) was obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA).

Cell culture. Human NB cells lines were purchased between 2014 and 2016 from certified suppliers. Cells were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen and used for cell culture experiments as previously described (25). SK-N-FI were from the Childhood Cancer Repository/Children’s Oncology Group Resource Laboratory, SK-N-AS (CRL-2137), and SK-N-BE from the ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), and Kelly (CB_92110411) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The SK-N-BE clone used was SK-N-Be(2)c (ATCC: CRL-2268). The MycoAlert™ PLUS Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) was used to monitor cells lines yearly for mycoplasma contamination. NB cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), Penicillin (100 IU/ml) and Streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (30-002-CI, Corning, Corning, NY, USA). The human primary neonatal skin fibroblasts were grown in DMEM medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml), non-essential amino acids (0.1 mM) and sodium pyruvate (1 mM). NB cells were grown in a humidified atmosphere at 37˚C with 5% CO2. Cells were 80-90% confluent when counted for use in experiments.

Immunoblotting. Tumor and cell protein lysates were harvested, with equal amounts of protein resolved by Western blotting as previously described (27). PARP, p27Kip1, and GAPDH levels were detected by incubating blots with primary antibodies diluted 1:1,000 in 5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Tween-20 overnight at 4˚C. Blots were washed with TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 three times for 5 min each. Secondary antibodies containing fluorophores were diluted 1:1000 in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Blots were again washed with TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 three times for 5 min each. Images of the blots were captured using an Odyssey Clx (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) Western blot scanner. Image Studio Lite (LI-COR Biosciences) software was used to quantitate the relative p27Kip1 signal.

Cell proliferation assay. The colorimetric sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay (28,29) was used to measure the cellular proliferation of actively growing NB cells following treatment with increasing concentrations of allicin as previously described (25,30). For NB cells treated with allicin, a single experiment was performed in quadruplicate for each condition. For neonatal skin fibroblast cells treated with allicin, three independent experiments were performed (N=16).

Microscopy. Light micrographs of the human primary neonatal skin fibroblasts treated with allicin were captured at 10X using a camera attached to a Leica DMi1 microscope.

Animal ethics. All experimental animal procedures were approved by the Michigan State University (MSU) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, Protocol #PROTO202100058). MSU is an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-certified institution.

In vivo tumor studies. The effects of allicin on in vivo NB tumor growth was performed using the NB patient-derived xenograft (PDX) line COG-N-623 (Children’s Oncology Group Childhood Cancer Repository). This PDX line was derived from a MYCN-amplified NB tumor established at time of disease progression after chemotherapy (31). Six- to eight-week-old athymic nude mice were injected with 1.5×107 COG-N-623 tumor cells and tumor volume was measured and calculated as previously described (27). Mice containing palpable tumors (~100 mm3) were randomized into 4 treatment groups: 1. Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) control (n=7); 2. 0.05 mg allicin in PBS (n=8); 3. 0.2 mg allicin in PBS (n=9); 4. 0.5/0.2mg allicin (n=4). For each group, the treatment was administered once weekly in 100 microliters via intra-tumor injection, distributing the volume across multiple quadrants of the tumor. After the first treatment, it was noted that the 0.5 mg allicin treated tumors exhibited excessive bleeding and their dose was cut to 0.2 mg allicin for subsequent treatments. Tumor volumes were measured 3 times per week. Tumors were treated for 2 weeks. At this point control tumors had to be euthanized since they had grown to approximately 2,500 mm3 in size. Mice were euthanized with CO2 using a Euthanex Prodigy system, which is compliant with the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) guidelines. The tumors were removed, weighed, snap frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80˚C.

Statistical analyses. An unpaired Student’s t-test assuming the null hypothesis was used to determine the statistical significance of allicin treatment on neuroblastoma cell proliferation, tumor volume and relative tumor p27Kip1 expression. Unless otherwise noted in the figure legend, for all comparisons, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Allicin inhibits tumor growth of neuroblastoma cells. Allicin is a natural product produced by the garlic plant (Figure 1A and B). We previously showed that chemically synthesized allicin with high purity induces apoptotic cell death in NB tumor cells (25). Herein we confirm that allicin inhibits the proliferation of the four NB tumor cell lines SK-N-FI, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE(2)c, and KELLY, in a dose-dependent fashion after 24 h of treatment (Figure 1C-F). The approximate concentration of allicin required to inhibit 50% cell growth was estimated in the range of 19-50 μM depending on the cell line and was most effective against the KELLY NB tumor cell line (Figure 1F).

Allicin does not induce cell death in human primary neonatal skin fibroblasts. To determine if allicin also inhibits non-cancerous human cells, we treated human primary neonatal skin fibroblast control cells with allicin in a dose-dependent manner (0, 6, 12, 25 μM) for 24 h. As shown in Figure 2A, allicin did not significantly affect cell proliferation of control cells. To determine if allicin induces apoptotic cell death, we examined these normal human control cells by light microscopy and confirmed that allicin does not induce cell detachment and the formation of rounded cell phenotypes, a hallmark of apoptosis (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the detection of PARP protein expression by immunodetection confirmed that apoptosis is not induced as judged by the lack of cleaved PARP product (Figure 2C). In addition, allicin also did not induce p27Kip1, a common marker of cytostasis and G1/S-linked cell cycle arrest (Figure 2D). In stark contrast, we previously published that allicin induces strong apoptotic cell death in four NB tumor cell lines (SK-N-FI, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE(2)c, and KELLY) as judged by PARP cleavage and rounded cell detachment (25). These results suggest that allicin only kills NB cancer cells by means of apoptosis but not normal human primary cells, which is an important observation indicating that future treatments with allicin may not lead to adverse side-effects in normal tissues.

Figure 2.

Effect of allicin on human primary control cells. Human primary neonatal skin fibroblasts treated with allicin (0, 6, 12, 25 μM) for 24 h. Allicin did not affect human primary neonatal skin fibroblast control cell proliferation after 24 h of treatment (A). Light micrographs show that allicin does not induce the detachment of adherent cells and the formation of rounded cell phenotypes, a hallmark of apoptosis (B). Allicin did not induce apoptosis in human primary neonatal skin fibroblast control cells, as indicated by the lack of cleaved PARP using the immunoblotting detection method (C). Likewise, there were no changes in the cell cycle marker p27Kip1 (C). Data represents the three independent experiments (N=16)±the standard deviation (B). Western blot images are representative of 2 (p27Kip1) or 3 (PARP) independent experiments.

Allicin inhibits PDX neuroblastoma tumor growth in vivo. To investigate if allicin inhibits tumor growth in vivo, we performed studies in mice using a PDX of human NB. All PDX tumors were treated with 0.05 mg, 0.2 mg, and 0.5/0.2 mg allicin per intra-tumoral injection or PBS (control) when tumors were palpable (day 0) and again on day 7 of the trial. On day 14, tumors in the control group and lowest allicin dose treatment group reached ≥2,500 mm3 in size, thus requiring euthanasia of these mice per internal IACUC guidelines. As shown in Figure 3, the tumor volumes of mice that received two treatments of allicin at 0.2 mg/injection were significantly smaller than tumors of control mice, as early as 7 days after the first injection as well as on day 14 of the study (p<0.05). Injecting tumors with 0.5 mg (day 0) and 0.2 mg (day 7) allicin further suppressed tumor growth (p<0.05), showing that allicin is an effective antitumor agent and able to inhibit NB PDX in mice.

Figure 3.

Antitumor efficacy of allicin in vivo. Mice harboring NB patient-derived xenograft (PDX) tumors were treated by intra-tumoral injections with 0.05, 0.2 and 0.5/0.2 mg allicin per injection when tumors were palpable (100 mm3, day 0) and seven days later (day 7). Tumors treated with allicin exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in tumor volume. Tumors treated with 0.2 mg (N=9, green line) and 0.5/0.2 mg (N=4, yellow line) allicin were statistically significantly smaller than control tumors (N=7, blue line) starting at day 7 and continued throughout the study until day 14. Treatment with 0.05 mg allicin (N=8, red line) had no effect on tumor volume. The data represents the mean tumor volume±standard error (S.E.) at each time point. *Denotes a statistically significant decrease as compared to control (p<0.05). Black arrows denote the days of intra-tumoral allicin injections.

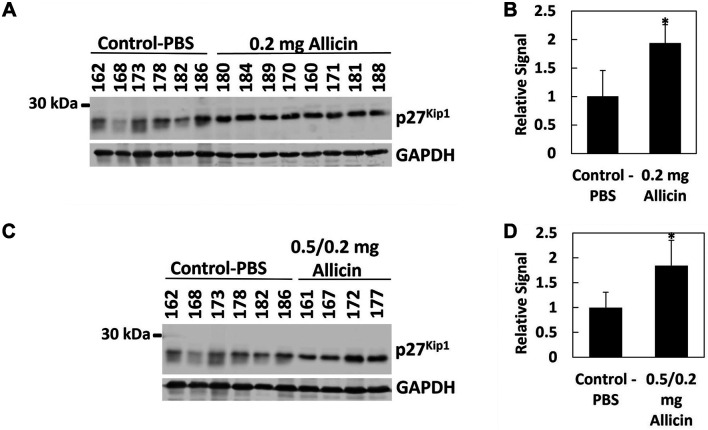

Allicin induces p27Kip1 protein expression in excised neuroblastoma PDX tumor tissues. Subsequent to our mouse study (Figure 3), all tumors were excised at the conclusion of the mouse study, and tumor tissues were further analyzed by western blot and immunodetection. We found that the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 significantly increased in allicin-treated tumors (p<0.05), indicating that in vivo, allicin induces p27Kip1-mediated G1/S cell cycle arrest (Figure 4). Additional protein markers including the tumor suppressor protein p53 and PARP did not change in response to allicin treatments (not shown), suggesting that unlike what we observed in cell cultures (25), allicin appears to suppress tumor growth in vivo by stalling cell cycle progression.

Figure 4.

Allicin treatment increases cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 protein in NB tumors. Excised tumors were analyzed for p27Kip1 protein levels by immunoblotting (A, C). Each number represents an individual mouse. GAPDH was used as a loading control. p27Kip1/GAPDH signal ratios were determined using Image Studio Lite (Ver 5.2) and normalized to control (B, D). Bar graphs represent the mean relative signal±S.D. Tumors treated with 0.2 mg (A, B) and 0.5/0.2 mg (C, D) allicin had increased amounts of p27Kip1 as compared to control. *Denotes a statistically significant increase as compared to control (p<0.05).

Discussion

In our previous studies of the human proteome, the most prevalent cellular targets of allicin were glycolytic enzymes and cytoskeletal proteins, many of which are critical in cancer development (32). Allicin has a broad-spectrum activity and has been shown to directly inhibit a range of SH-containing enzymes (33). In addition, our own studies revealed that allicin targets ODC (25). Importantly, allicin can regulate SHP-1/STAT3, Nrf2, ROS, ERK and p38 MAPK-associated signaling cascades, all of which are key regulators of tumorigenesis (34-39). A number of synergisms have also been reported, for example, the combination of allicin with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), cyclophosphamide, and artesunate (40-42). Furthermore, many tumor types are associated with abnormally high GSH levels which protects the tumor cells against some therapeutic agents (43,44). Because GSH is a primary target for allicin, it depletes the cellular GSH pool and that is likely to further help restrict tumor cells. Interestingly, it was recently shown that enhanced glutathione biosynthesis might be a selective metabolic adaptation required for initiation of MYCN-driven NB, suggesting that glutathione-targeted drugs might be used as a potential preventative strategy, or as an adjuvant to existing chemotherapies in established disease (45).

While several studies have shown the cytotoxic potency of allicin in cultured cancer cell lines and the induction of apoptosis (34-42,46), fewer studies have examined its effect on normal, non-cancerous human primary cells. We here show that, at the doses employed, allicin only moderately reduced the growth of human primary neonatal skin fibroblasts, without inducing apoptotic cell death (Figure 2). Therefore, allicin is cytotoxic against NB cancer cells only and not normal cells at identical doses, suggesting that future drug treatments with allicin will likely not induce significant adverse effects in normal tissues surrounding the tumor.

To our knowledge, the efficacy and bioavailability of allicin in a NB tumor mouse model has not been studied before. Allicin, if taken orally, is hydrolyzed in the acidic environment in the stomach and in addition it reacts with GSH in cells and tissues, further reducing the amount of allicin that might reach tumors to S-thioallylate cysteine residues there. In regard of these factors reducing the bioavailability of allicin taken orally, we reasoned that a more effective means of administration for allicin would be direct intra-tumoral injection. Our results confirmed that allicin administered in this way is quite potent and indeed significantly reduced NB PDX tumor growth in vivo (Figure 3).

Conclusion

There is increasing interest in, and new technologies available for, the treatment of cancer patients via intra-tumoral injections, an administration strategy that has been successful in the treatment of in vivo cancer models (47). Moreover, this tumor-tissue targeted treatment method also significantly reduces the occurrence of side effects commonly associated with systemic chemotherapy, because allicin is liable to be largely titrated out within the tumor itself by reacting with its substrates in situ. Thus, for these reasons, allicin, or perhaps allyl polysufanes that are able to carry out the thioallylation of thiols, might be premier candidates for intra-tumoral treatments of tumors including neuroblastoma, glioblastoma, and medulloblastoma.

Funding

This study was supported by Spectrum Health-Michigan State University Alliance Corporation funds (RG072418-K5STA to ASB) and by a generous gift (RN100728-K5BAC to ASB) from the Alex Mandarino Foundation (St. Joseph, Michigan).

Authors’ Contributions

ASB designed the study and developed the technical protocols. MCHG synthesized allicin. CRS performed all biological experiments including PDX in vivo studies, evaluated raw data, and prepared final figures. ASB, CRS, and AJS interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. All Authors reviewed the final draft.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

Acknowledgements

The human NB PDX and the SK-N-FI cell line were kindly provided by the Children’s Oncology Group Childhood Cancer Repository (Dr. Patrick Reynolds), powered by the Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation. We thank the late Dr. Patrick Woster (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC) for providing DFMO.

References

- 1.Borlinghaus J, Foerster Née Reiter J, Kappler U, Antelmann H, Noll U, Gruhlke MCH, Slusarenko AJ. Allicin, the odor of freshly crushed garlic: a review of recent progress in understanding allicin’s effects on cells. Molecules. 2021;26(6):1505. doi: 10.3390/molecules26061505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mengers HG, Schier C, Zimmermann M, Gruhlke MCH, Block E, Blank LM, Slusarenko AJ. Seeing the smell of garlic: Detection of gas phase volatiles from crushed garlic (Allium sativum), onion (Allium cepa), ramsons (Allium ursinum) and human garlic breath using SESI-Orbitrap MS. Food Chem. 2022;397:133804. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbach M, Santana TM, Moxham H, Tinson R, Anwar A, Groom M, Hamilton CJ. Antimicrobial garlic-derived diallyl polysulfanes: Interactions with biological thiols in Bacillus subtilis. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2019;1863(6):1050–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodeur GM. Neuroblastoma: biological insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(3):203–216. doi: 10.1038/nrc1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maris JM. Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(23):2202–2211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthay KK, Maris JM, Schleiermacher G, Nakagawara A, Mackall CL, Diller L, Weiss WA. Neuroblastoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2(1):16078. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bello-Fernandez C, Cleveland JL. c-myc transactivates the ornithine decarboxylase gene. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;182:445–452. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77633-5_56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bello-Fernandez C, Packham G, Cleveland JL. The ornithine decarboxylase gene is a transcriptional target of c-Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1993;90(16):7804–7808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace HM, Fraser AV, Hughes A. A perspective of polyamine metabolism. Biochem J. 2003;376(Pt 1):1–14. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pegg AE. Mammalian polyamine metabolism and function. IUBMB Life. 2009;61(9):880–894. doi: 10.1002/iub.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pegg AE. Functions of polyamines in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(29):14904–14912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.731661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallick CJ, Gamper I, Thorne M, Feith DJ, Takasaki KY, Wilson SM, Seki JA, Pegg AE, Byus CV, Bachmann AS. Key role for p27Kip1, retinoblastoma protein Rb, and MYCN in polyamine inhibitor-induced G1 cell cycle arrest in MYCN-amplified human neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2005;24(36):5606–5618. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bachmann AS, Geerts D. Polyamine synthesis as a target of MYC oncogenes. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(48):18757–18769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.TM118.003336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geerts D, Koster J, Albert D, Koomoa DL, Feith DJ, Pegg AE, Volckmann R, Caron H, Versteeg R, Bachmann AS. The polyamine metabolism genes ornithine decarboxylase and antizyme 2 predict aggressive behavior in neuroblastomas with and without MYCN amplification. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(9):2012–2024. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachmann AS. The role of polyamines in human cancer: Prospects for drug combination therapies. Hawaii Med J. 2004;63(12):371–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachmann AS, Geerts D, Sholler G. Neuroblastoma: Ornithine decarboxylase and polyamines are novel targets for therapeutic intervention. In: Pediatric cancer, neuroblastoma: Diagnosis, therapy, and prognosis. Hayat MA (ed.) Springer. 2012:pp. 91–103.. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koomoa DL, Borsics T, Feith DJ, Coleman CC, Wallick CJ, Gamper I, Pegg AE, Bachmann AS. Inhibition of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase by inhibitor SAM486A connects polyamine metabolism with p53-Mdm2-Akt/protein kinase B regulation and apoptosis in neuroblastoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(7):2067–2075. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koomoa DL, Yco LP, Borsics T, Wallick CJ, Bachmann AS. Ornithine decarboxylase inhibition by alpha-difluoro-methylornithine activates opposing signaling pathways via phosphorylation of both Akt/protein kinase B and p27Kip1 in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68(23):9825–9831. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lange I, Geerts D, Feith DJ, Mocz G, Koster J, Bachmann AS. Novel interaction of ornithine decarboxylase with sepiapterin reductase regulates neuroblastoma cell proliferation. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(2):332–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saulnier Sholler GL, Gerner EW, Bergendahl G, MacArthur RB, VanderWerff A, Ashikaga T, Bond JP, Ferguson W, Roberts W, Wada RK, Eslin D, Kraveka JM, Kaplan J, Mitchell D, Parikh NS, Neville K, Sender L, Higgins T, Kawakita M, Hiramatsu K, Moriya SS, Bachmann AS. A phase I trial of DFMO targeting polyamine addiction in patients with relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casero RA Jr, Marton LJ. Targeting polyamine metabolism and function in cancer and other hyperproliferative diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(5):373–390. doi: 10.1038/nrd2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casero RA Jr, Murray Stewart T, Pegg AE. Polyamine metabolism and cancer: treatments, challenges andopportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(11):681–695. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0050-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holbert CE, Cullen MT, Casero RA Jr, Stewart TM. Polyamines in cancer: integrating organismal metabolism and antitumour immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(8):467–480. doi: 10.1038/s41568-022-00473-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerner EW, Meyskens FL Jr. Polyamines and cancer: old molecules, new understanding. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(10):781–792. doi: 10.1038/nrc1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schultz CR, Gruhlke MCH, Slusarenko AJ, Bachmann AS. Allicin, a potent new ornithine decarboxylase inhibitor in neuroblastoma cells. J Nat Prod. 2020;83(8):2518–2527. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albrecht F, Leontiev R, Jacob C, Slusarenko AJ. An optimized facile procedure to synthesize and purify allicin. Molecules. 2017;22(5):770. doi: 10.3390/molecules22050770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schultz CR, Swanson MA, Dowling TC, Bachmann AS. Probenecid increases renal retention and antitumor activity of DFMO in neuroblastoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2021;88(4):607–617. doi: 10.1007/s00280-021-04309-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skehan P, Storeng R, Scudiero D, Monks A, McMahon J, Vistica D, Warren JT, Bokesch H, Kenney S, Boyd MR. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82(13):1107–1112. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orellana EA, Kasinski AL. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay in cell culture to investigate cell proliferation. Bio Protoc. 2016;6(21):e1984. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schultz CR, Geerts D, Mooney M, El-Khawaja R, Koster J, Bachmann AS. Synergistic drug combination GC7/DFMO suppresses hypusine/spermidine-dependent eIF5A activation and induces apoptotic cell death in neuroblastoma. Biochem J. 2018;475(2):531–545. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen TH, Koneru B, Wei SJ, Chen WH, Makena MR, Urias E, Kang MH, Reynolds CP. Fenretinide via NOXA induction, enhanced activity of the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax in high BCL-2-expressing neuroblastoma preclinical models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18(12):2270–2282. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruhlke MCH, Antelmann H, Bernhardt J, Kloubert V, Rink L, Slusarenko AJ. The human allicin-proteome: S-thioallylation of proteins by the garlic defence substance allicin and its biological effects. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;131:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curtis H, Noll U, Störmann J, Slusarenko AJ. Broad-spectrum activity of the volatile phytoanticipin allicin in extracts of garlic (Allium sativum L.) against plant pathogenic bacteria, fungi and Oomycetes. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2004;65(2):79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2004.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bat-Chen W, Golan T, Peri I, Ludmer Z, Schwartz B. Allicin purified from fresh garlic cloves induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells via Nrf2. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62(7):947–957. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2010.509837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cha JH, Choi YJ, Cha SH, Choi CH, Cho WH. Allicin inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in U87MG human glioblastoma cells through an ERK-dependent pathway. Oncol Rep. 2012;28(1):41–8. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen H, Zhu B, Zhao L, Liu Y, Zhao F, Feng J, Jin Y, Sun J, Geng R, Wei Y. Allicin inhibits proliferation and invasion in vitro and in vivo via SHP-1-mediated STAT3 signaling in cholangiocarcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;47(2):641–653. doi: 10.1159/000490019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, Ni J, Tang Y, Wang X, Tang H, Li H, Zhang S, Shen X. Allicin inhibits mouse colorectal tumorigenesis through suppressing the activation of STAT3 signaling pathway. Nat Prod Res. 2019;33(18):2722–2725. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1465425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhuang J, Li Y, Chi Y. Role of p38 MAPK activation and mitochondrial cytochrome-c release in allicin-induced apoptosis in SK-N-SH cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2016;27(4):312–317. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou X, Liang J, Sun J, Hu X, Lei L, Wu D, Liu L. Allicin sensitizes hepatocellular cancer cells to anti-tumor activity of 5-fluorouracil through ROS-mediated mitochondrial pathway. J Pharmacol Sci. 2016;131(4):233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao XY, Geng XJ, Zhai WL, Zhang XW, Wei Y, Hou GJ. Effect of combined treatment with cyclophosphamidum and allicin on neuroblastoma–bearing mice. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2015;8(2):137–141. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang W, Huang Y, Wang JP, Yu XY, Zhang LY. The synergistic anticancer effect of artesunate combined with allicin in osteosarcoma cell line in vitro and in vivo. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(8):4615–4619. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.8.4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jobani BM, Najafzadeh N, Mazani M, Arzanlou M, Vardin MM. Molecular mechanism and cytotoxicity of allicin and all-trans retinoic acid against CD44+ versus CD117+ melanoma cells. Phytomedicine. 2018;48:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Estrela JM, Ortega A, Obrador E. Glutathione in cancer biology and therapy. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2006;43(2):143–181. doi: 10.1080/10408360500523878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Traverso N, Ricciarelli R, Nitti M, Marengo B, Furfaro AL, Pronzato MA, Marinari UM, Domenicotti C. Role of glutathione in cancer progression and chemoresistance. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:972913. doi: 10.1155/2013/972913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carter DR, Sutton SK, Pajic M, Murray J, Sekyere EO, Fletcher J, Beckers A, De Preter K, Speleman F, George RE, Haber M, Norris MD, Cheung BB, Marshall GM. Glutathione biosynthesis is upregulated at the initiation of MYCN-driven neuroblastoma tumorigenesis. Mol Oncol. 2016;10(6):866–878. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gruhlke MC, Nicco C, Batteux F, Slusarenko AJ. The effects of allicin, a reactive sulfur species from garlic, on a selection of mammalian cell lines. Antioxidants (Basel) 2016;6(1):1. doi: 10.3390/antiox6010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bender LH, Abbate F, Walters IB. Intratumoral administration of a novel cytotoxic formulation with strong tissue dispersive properties regresses tumor growth and elicits systemic adaptive immunity in in vivo models. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4493. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]