Abstract

The autolytic LytA amidase from 12 bile (deoxycholate)-insoluble streptococcal isolates (formerly classified as atypical Streptococcus pneumoniae) showing different antibiotic resistance patterns was studied. These atypical strains, which autolyze at the end of the stationary phase of growth, contain highly divergent lytA alleles (pairwise evolutionary distances of about 20%) compared to the lytA alleles of typical pneumococci. The atypical LytA amidases exhibit a peculiar deletion of two amino acids responsible for cell wall anchoring in the carboxy-terminal domain and have a reduced specific activity. These enzymes were inhibited by 1% deoxycholate but were activated by 1% Triton X-100, a detergent that could be used as an alternative diagnostic test for this kind of strain. Preparation of functional chimeric enzymes, PCR mutagenesis, and gene replacements demonstrated that the characteristic bile insolubility of these atypical strains was due to their peculiar carboxy-terminal domain and that the 2-amino-acid deletion was responsible for the inhibitory effect of deoxycholate. However, the deletion alone did not affect the specific activity of LytA. A detailed characterization of the genes encoding the 16S rRNA and SodA together with multilocus sequence typing indicated that the strains studied here are not a single clone and, although they cannot be strictly classified as typical pneumococci, they represent a quite diverse pool of organisms closely related to S. pneumoniae. The clinical importance of these findings is underlined by the role of the lytA gene in shaping the course of pneumococcal diseases. This study can also contribute to solving diagnostic problems and to understanding the evolution and pathogenic potential of species of the Streptococcus mitis group.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is an important human pathogen that is currently the main cause of acute otitis media, sinusitis, pneumonia requiring hospitalization in adults, and meningitis. All these infections cause substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide (28). Three classical tests are used in clinical laboratories to differentiate pneumococcus from other alpha-hemolytic streptococci: optochin sensitivity, immunological reaction with type-specific antisera (capsular reaction or Quellung test), and bile or deoxycholate (Doc) solubility (35). Although most laboratories in the United States rely on bile solubility as the first-line method of identification of pneumococcus or as a backup for optochin-resistant (Optr phenotype) strains, in most countries laboratories today depend on optochin susceptibility, and when there is no inhibitory zone around the optochin disk, the strain is routinely identified as a viridans Streptococcus and Doc testing is not usually performed (39). Isolates putatively identified as pneumococci on the basis of other analyses (2, 31, 40) but giving negative results in one or more of the classical assays are usually referred to as atypical pneumococci.

The characteristic Doc solubility is due to the triggering of the major pneumococcal autolysin (38). Pneumococcus possesses several murein hydrolases that split down different bonds in the peptidoglycan of the cell wall, and it has been proposed that these enzymes are present in practically all known bacterial systems. These ubiquitous enzymes play important biological roles in cell wall enlargement and degradation (49).

The major autolysin of S. pneumoniae, an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase (LytA) (25), was the first example of a bacterial autolytic enzyme characterized at the molecular level (18). This amidase exhibits a modular organization in which the amino-terminal domain functions as the catalytic region, whereas the carboxy-terminal domain (choline-binding domain) possesses a pair of six repeated motifs involved in recognition of the choline residues present in the cell wall teichoic acids (14). More recently, elucidation of the three-dimensional structure of the C-terminal domain has revealed the existence, at the end of LytA, of a highly divergent seventh motif (12). This modular arrangement has also been demonstrated for the lytic enzymes of pneumococcal phages (34), and its functionality was fully confirmed by the preparation of various active chimeric enzymes (4). A similar design was found later for different murein hydrolases isolated mainly from gram-positive bacteria (19). In the particular case of Staphylococcus aureus, it has been shown that a group of three motifs localized at the central part of a bifunctional murein hydrolase (Atl) anchor the protein to the equatorial region of the cell wall to control the separation of the daughter cell at the end of cell division (1).

In a previous report (6), we characterized the amidase of a clinical strain (101/87) that was isolated on the basis of hybridization with a lytA probe (pCE3) embracing the sequence coding for the N-terminal domain of the amidase (11). This isolate exhibited a Doc-insoluble phenotype, and in contrast to the LytA amidase from typical pneumococcal strains, Doc inhibited the enzymatic activity of the LytA101 amidase. We suggested that modifications in the primary structure or in the mechanisms that control the lytic activity of LytA might be responsible for the Doc-insoluble phenotype of this atypical pneumococcal strain (6).

The relevance of using the lytA gene as a specific pneumococcal identification tool is a subject of great controversy. Recent reports have envisaged that using lytA probes to identify difficult organisms as putative atypical pneumococci could also select other genetically related organisms such as Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus oralis (22, 52). On the contrary, other investigations concluded that the lytA PCR amplification approach could be used to correctly differentiate S. pneumoniae from related species of the Streptococcus mitis group (30, 37).

To get insight into the Doc solubility defect of atypical pneumococci, we report here the characterization of several lytA alleles from a group of clinical isolates that exhibit aberrant reactions to Doc. The genetic and biochemical analyses of the amidases isolated from these strains and the constructions of chimeric proteins between these enzymes and the wild-type LytA from a typical pneumococcal strain provided insights into the molecular basis underlying the peculiar phenotype of these strains concerning a gene encoding an important virulence factor of S. pneumoniae (28). In addition, analyses of several housekeeping genes of the isolates reported here have been done to achieve a more accurate identification of these bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The clinical isolates included in this study (Table 1) were provided by the Spanish Pneumococcal Reference Laboratory (Majadahonda, Spain). Strain 101 has been described previously (6). We also used the laboratory pneumococcal strains R6 (lytA+) and M41 (lytA41) (15). In addition, we employed the type strains of S. pneumoniae (CECT 993), S. mitis (NCTC 12261), and S. oralis (NCTC 11427). Escherichia coli DH5α (23) served as the host for the expression vector pINIII-A3 (27). E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani medium (44), and S. pneumoniae was grown in C medium (32) supplemented with yeast extract (0.8 mg/ml; Difco Laboratories) (C+Y medium). The procedures for genetic transformation of S. pneumoniae (45) and E. coli (44) have been described previously.

TABLE 1.

Some characteristics of the atypical (DocT− Lyt+) isolates used in this studya

| Strain | Yr of isolation | Origin | Phenotype

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serogroup | Opt | DocF | MIC (μg/ml) | |||

| 101 | 1987 | Blood | NT | R | − | P (2); T (0.12); E (1) |

| 1508 | 1992 | Pharynx | NT | R | − | P (0.06), T (0.5), E (0.25) |

| 11923 | 1992 | CSF | NT | S | − | P (8), T (0.5), E (4) |

| 8224 | 1994 | Pharynx | NT | R | − | P (8), T (0.25), E (1) |

| 10546 | 1994 | Sputum | 19 | R | − | P (0.015), T (0.5), E (1) |

| 782 | 1996 | BAA | NT | S | + | P (0.25), T (128), E (>128) |

| 1230 | 1996 | Sputum | 19 | S | − | P (4), T (1), E (0.06) |

| 1283 | 1996 | Sputum | NT | S | − | P (0.015), T (0.5), E (0.06) |

| 1338 | 1996 | Sputum | NT | S | + | P (1), T (0.5), E (0.12) |

| 1078 | 1997 | Conjunctiva | NT | R | − | P (0.12), T (32), E (8) |

| 1383 | 1997 | P-BS | 19 | S | − | P (0.25), T (0.5), E (8) |

| 1629 | 1997 | BAA | 19 | S | − | P (1), T (64), E (0.06) |

NT, nontypeable; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; BAA, bronchoalveolar aspirate; P-BS, protected-brush specimen; P, penicillin; T, tetracycline; E, erythromycin. Values indicating antibiotic resistance are boldfaced.

Determination of Doc solubility and autolytic phenotype.

Unless stated otherwise, 0.5 ml of exponentially growing cultures of S. pneumoniae or atypical pneumococci received 50 μl of 1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) and 50 μl of a 10% Doc solution in water. The mixtures were incubated for up to 15 min at 37°C. When the turbidity of the cell suspension decreased more than 50% from the initial value, the strain was designated DocT+. We also used a filter technique (17) to determine the lytic phenotype. In short, colonies of S. pneumoniae or atypical pneumococci grown on the surface of C+Y plates containing catalase (250 U/ml) were lifted off on a nitrocellulose filter and deposited on velvet saturated with a 1% Doc solution buffered with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer. After incubation for 10 min at 37°C, the filter was stained in a Coomassie brilliant blue solution and destained briefly, and the colonies on the filter were eliminated by stripping by hand. Afterwards, the filter was washed under tap water and heat dried. Colonies that lysed (DocF+) appeared as blue spots, whereas those that did not lyse (DocF−) appeared as white circles (17). Pneumococcal isolates that autolysed in the stationary phase of culture were designated Lyt+.

PCR amplification, cloning, and nucleotide sequencing.

Routine DNA manipulations were performed essentially as described before (44). DNA fragments were purified by using the Geneclean II kit (Bio 101). The relevant oligonucleotide primers used were LA_Sau5(1), 5′-cggGATCCTTCCTCTAGTTTCTAGC-3′; LA_Sau3(2376/c), 5′-cggGATCCGCTTTTCTTTCAGTTTC-3′; LA5_Ext(384), 5′-ggtctagAAGCTTTTTAGTCTGGGGTG-3′; LA3_Ext(1596/c), 5′-ggggatccAAGCTTTTTCAAGACCTAATAATATG-3′; MUTD1(1441), 5′-AGCGGACGGATGGTACTACC-3′; and MUTD2 (1466/c), 5′-GGTAGTACCATCCGTCCGCT-3′. Numbers in parentheses indicate the position of the first nucleotide of the primer in the sequence reported previously (18) (accession no. M13812), and c means that the sequence corresponds to the complementary strand. Lowercase letters indicate nucleotides introduced to construct appropriate restriction sites (shown in italics). We also used primers 63f and 1387r to amplify and sequence the 16S rRNA genes (36) and SOD-UP and SOD-DOWN for the sodA gene (30). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was carried out exactly as described elsewhere (7).

DNA sequence was determined by the dideoxy chain termination method (47) with an automated ABI Prism 3700 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). All primers for PCR amplification and nucleotide sequencing were synthesized on a Beckman model Oligo 1000 M synthesizer.

Data analysis.

Deduced amino acid sequences were analyzed with the Protein Analysis Tool at the World Wide Web molecular biology server of the Geneva University Hospital and the University of Geneva. Protein sequence similarity searches were done with the blastp program via the National Institute for Biotechnology Information server. Pairwise and multiple protein sequence alignment were done with the align and clustal w programs, respectively, at the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Center server (http://kiwi.imgen.bcm.edu:8088). DNA and protein sequences were also analyzed with the Genetics Computer Group software package (version 10.0) (3). Pairwise evolutionary distances (PEDs; estimated number of substitutions per 100 bases) were determined using the distances program with the correction adequate to each case. Multiple sequence alignments were created with pileup. Three-dimensional modeling of the C-terminal domain of the atypical LytA was carried out with the geno3d program run at the Pole Bio-Informatique Lyonnais server (http://geno3d-pbil.ibcp.fr) using the crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of LytA (12) as a model.

Expression and purification of the amidases.

E. coli recombinant strains were incubated in Luria-Bertani medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). The culture was centrifuged (10,000 × g, 5 min), and the bacteria were resuspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and disrupted in a French cell press. The insoluble fraction was separated by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 15 min), and the supernatant was loaded into a DEAE-cellulose column to purify the amidases in a single step following a procedure described previously (46).

Miscellaneous techniques.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed following the agar dilution technique (10). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out with the buffer system described by Laemmli (33) in 10 or 12.5% polyacrylamide gels, and protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. Pneumococcal cell walls were radioactively labeled with [methyl-3H]choline as described (38). Assays for cell wall lytic (amidase) activity were carried out according to standard conditions described elsewhere using labeled cell walls as the substrate (25). One unit of amidase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the hydrolysis (solubilization) of 1 μg of cell wall material in 10 min. Serogrouping was carried out by using specific antisera purchased from the Staten Seruminstitut (Copenhagen).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases. The lytA alleles have been assigned accession numbers AJ419973 to AJ419983, the sodA fragments are accession numbers AJ421532 to AJ421543, and the housekeeping gene fragments are accession numbers AJ422245 to AJ422287.

RESULTS

Isolation and phenotypic characteristics of atypical S. pneumoniae strains.

All the isolates collected in different Spanish hospitals during a 10-year period were putatively identified as pneumococci on the basis of hybridization with a lytA probe (11). In four cases (strains 10546, 1230, 1383, and 1629), the presence of a serogroup 19 capsule could be demonstrated (Table 1). In addition, five isolates were Optr. Although all the strains autolysed at the stationary phase of growth when incubated in C+Y medium (Lyt+ phenotype), none of them lysed when tested by the Doc tube assay described above (DocT− phenotype). However, two isolates (strains 782 and 1338) showed a DocF+ phenotype when tested for Doc-induced lysis with a filter technique (see Materials and Methods). This behavior might be explained by taking into account that in the filter technique the detergent must diffuse through the nitrocellulose membrane, and consequently, it is expected that the actual concentration of Doc causing the lysis of the colonies may be lower than that used in the tube assay (1%). If this were the case, atypical LytA amidases that are less sensitive to Doc, are produced in higher amounts, and/or have a higher specific activity should possess enough active enzyme to lyse the cells in the colony filter assay, giving rise to blue spots (DocF+ phenotype).

In agreement with this hypothesis, exponentially growing cultures of strains 782 and 1338 were subjected to the Doc assay in tubes but with decreasing amounts of the detergent. When 0.05 or 0.1% Doc was employed, the cultures of those strains lysed, whereas no lysis was observed at Doc concentrations of 0.5% or higher (data not shown). With any other atypical strain tested, lysis did not occur at any Doc concentration used. Interestingly, with the exception of strain 1078, a strain that shows very low autolytic activity (not shown), all the atypical pneumococci lysed when 1% Triton X-100 was used instead of Doc. In vitro experiments (not shown) demonstrated that, in contrast to the inhibitory effect of Doc, Triton X-100 stimulated the amidase activities of the atypical amidases.

Relationship between lytic phenotype and genetic background.

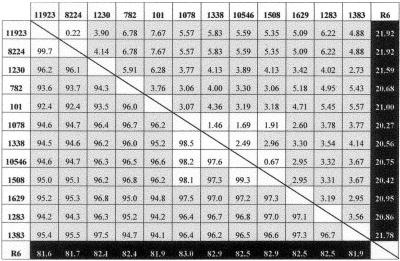

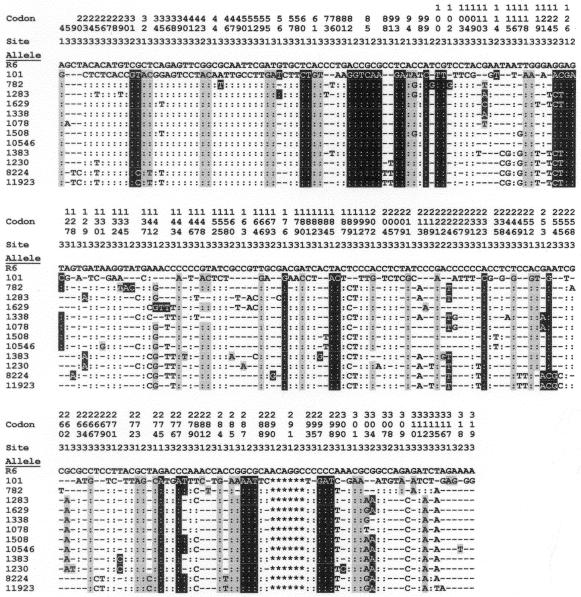

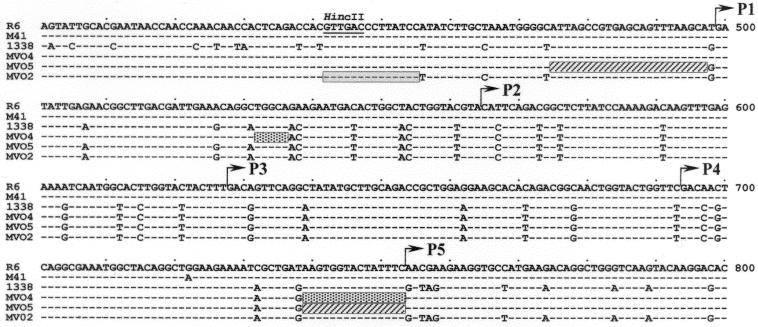

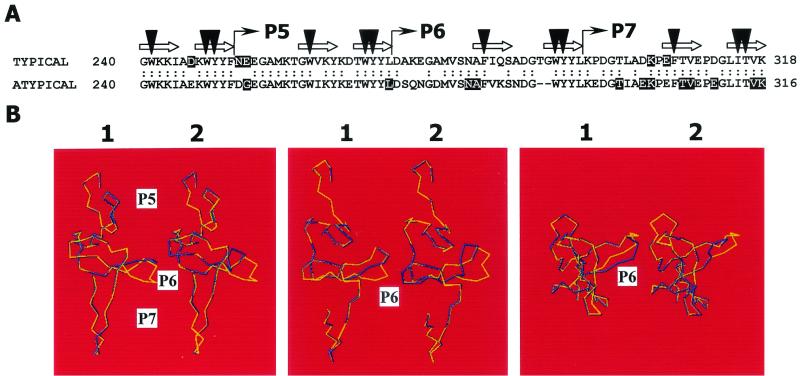

In a previous report, we suggested that the failure of Doc to induce the lysis of the 101 strain was due to the presence of an atypical lytA allele (designated lytA101 hereafter) in this isolate (6). To further investigate the relationship between the lytA+ alleles characteristic of the typical pneumococcal strains, that is, those strains showing a DocT+ phenotype, from those alleles present in the DocT− isolates, we amplified by PCR the lytA gene from the strains shown in Table 1. Sequence comparison (Fig. 1) revealed that the atypical lytA alleles were quite different from the lytAR6 allele, i.e., the PEDs were higher than 20%. However, the lytA alleles from atypical isolates were more than 92% identical to each other. Besides, the alleles from strains 8224 and 11923 on one side and 1078, 1338, 10546, and 1508 on the other were more than 97.5% identical (PEDs lower than 2.5%). We can conclude from these data that the sequence similarities of the atypical LytA amidases with LytAR6 ranged from 84.5 to 86.7% identity (88.6 to 90.5% similarity), whereas identities higher than 93.7% were found when they were compared with the atypical amidases. When the lytA alleles were aligned, up to 247 nucleotide positions were found to be modified (Fig. 2). These mutations were evenly distributed over the entire gene, and no clear indication of mosaic structures could be observed. The most noticeable feature of the atypical alleles is the presence of a 6-bp deletion (ACAGGC), located between nucleotide positions 868 and 873, coding for Thr290-Gly291 in the P6 motif of the wild-type LytA amidase.

FIG. 1.

Pairwise comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the lytA alleles from atypical isolates and from strain R6. Above the diagonal, a matrix of PEDs between aligned sequences is shown. Below the diagonal, the percent nucleotide identity is shown. Black, gray, and white boxes indicate identities lower than 85% (PEDs higher than 20%), between 90 and 97.5% (PEDs between 8 and 5%), and higher than 97.5% (PEDs lower than 2.5%), respectively.

FIG. 2.

Sequence variation in atypical lytA alleles. Each of the sites where the sequence of one or more of the lytA alleles differs from that of the wild type (lytAR6) is shown. Hyphens and colons represent nucleotides identical to those of the lytAR6 and lytA101 alleles, respectively. Sites where all of the sequences are identical are not shown. Sites 1, 2, and 3 indicate the first, second, and third nucleotide, respectively, in the codon. The numbering of the codons corresponds to that in a previous publication (16). Gray and black boxes indicate nucleotide changes causing conserved and nonconserved amino acid substitutions, respectively.

Biochemical characterization of some LytA-like amidases.

To get more insights on the biochemical peculiarities of the LytA-like enzymes of the strains studied here and to determine if these features correlate with the DocT− phenotype, the genes lytA782, lytA1078, and lytA1338 were cloned and expressed in E. coli, and the proteins were purified to homogeneity. The LytAR6 and the LytA101 amidases were used as controls (Table 2). The purified enzymes from the atypical pneumococci showed a reduced specific activity ranging between 32% (LytA1078) and 55% (LytA1338) of that of LytAR6. In addition, Doc inhibited the activity of the LytA-like amidases, whereas the LytAR6 enzyme was not affected by the detergent (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Specific activities and Doc sensitivities of purified LytA-like amidases

| Amidase | Sp act, 10−3 U/mg of protein (%)a | Activity in the presence of 1% Doc (% of wild-type activity) |

|---|---|---|

| LytAR6 | 980 (100) | 100 |

| LytA101 | 400 (41) | 57 |

| LytA782 | 404 (41) | 46 |

| LytA1078 | 318 (33) | 50 |

| LytA1338 | 538 (55) | 35 |

Activity values are the averages of at least three independent determinations. The percentage of wild-type activity is shown in parentheses.

Identification of the region of lytA-like alleles responsible for Doc sensitivity by constructing chimeric gene products.

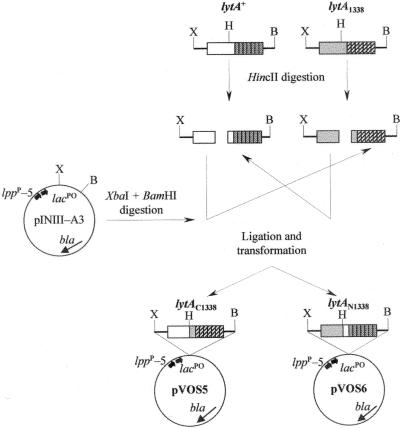

Using the lytA+ and the lytA1338 alleles from strains R6 and 1338, respectively, we constructed two chimeric genes following the procedure illustrated in Fig. 3. The resulting plasmids, pVOS5 and pVSO6, respectively, were expressed in E. coli, and the corresponding chimeric amidases, LytAC1338 and LytAN1338, were purified to homogeneity. The specific activities of LytAC1338 and LytAN1338 were 50 and 65% of that of the LytAR6 enzyme, respectively (not shown). Remarkably, the chimeric enzyme LytAN1338, which is built up by the N-terminal end of LytA1338 and the C-terminal end of the LytAR6 amidase, was not affected in its activity by the presence of 1% Doc, whereas LytAC1338, containing the C terminus of LytA1338 and a wild-type LytA N-terminal moiety, showed a reduction of more than 60% of activity in the presence of detergent (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of the construction of chimeric genes between the lytA+ and lytA1338 alleles. The corresponding genes were PCR amplified with oligonucleotide primers LA5_Ext and LA3_Ext. The locations of the tandem promoters lppp-5 and lacpo in pINIII-A3 are shown. Abbreviations: bla, gene encoding β-lactamase; B, BamHI; H, HincII; X, XbaI. The elements of the figure are not drawn at the same scale.

Construction of a mutant amidase lacking two amino acids in its C-terminal moiety.

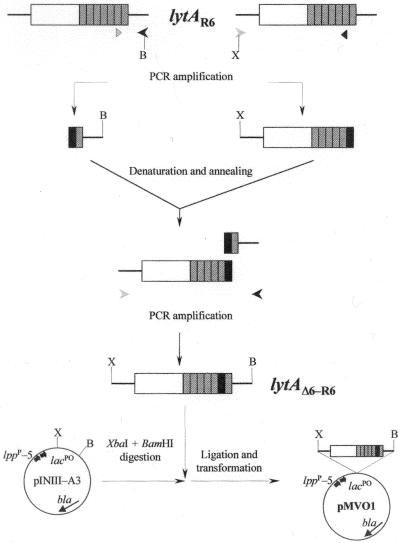

To investigate the precise role of the 2-amino-acid deletion (6-bp deletion) in the P6 motif of the LytA-like enzymes, site-directed mutagenesis was used to construct a ΔlytA mutation of the lytAR6 gene (lytAΔ6-R6) (Fig. 4). The resulting plasmid, pMVO1, harboring the mutant gene was used to overproduce in E. coli the deleted LytA enzyme (designated LytAΔ6-R6 hereafter). The purified amidase showed a specific activity of 910,000 U/mg, similar to that of the LytAR6 amidase (Table 2), but it was inhibited by 1% Doc and lost 30% of its enzymatic activity in the presence of the detergent (not shown). These results strongly suggested that sensitivity to Doc was influenced by the 6-bp deletion and that the low specific activity of the LytA-like amidases had to be ascribed to another mutation(s) in the corresponding genes. Nevertheless, we cannot discard the possibility that other mutations in the atypical isolates, e.g., cell wall alterations, might contribute to the atypical behavior of these strains when tested with Doc.

FIG. 4.

Construction of the expression vector pMVO1, encoding a 2-amino-acid deletion in the R6 amidase. The deleted motif is shown as a black box. The locations and directions of the oligonucleotide primers LA5_Ext (gray arrowhead), LA3_Ext (black arrowhead), MUTD1 (gray triangle), and MUTD2 (black triangle) are indicated. Abbreviations: B, BamHI; X, XbaI.

To further ascertain whether only the 2-amino-acid deletion in the P6 motif of the atypical lytA alleles was sufficient to inhibit lysis by Doc, we used genetic transformation to introduce the lytAΔ6-R6 allele into the R6 background. The R6 descendant strain M41 (lytA41) was employed as the recipient. This mutant has suffered a G-to-A transition at nucleotide 722 of the lytA gene, leading to the formation of a UAG stop codon (15) (Fig. 5). Consequently, M41 exhibits a DocT− DocF− phenotype. Competent M41 cells were transformed with pMVO1 (Fig. 4) and plated, and the colonies were tested for the DocF phenotype. Several DocF+ colonies were found, and one of them (strain MVO1) was isolated for further analysis. PCR amplification and sequencing of the lytAMVO1 gene demonstrated the presence of the 6-bp deletion. In addition, when MVO1 was subjected to the Doc tube test, it showed a DocT+ phenotype (not shown). Taken together, these results revealed that the 6-bp deletion, although causing the synthesis of an amidase that is inhibited in vitro by Doc, is not sufficient per se to produce either a DocT− or a DocF− phenotype.

FIG. 5.

Multiple alignment of a partial nucleotide sequence of the lytA alleles from transformants MVO2, MVO4, and MVO5. The nucleotide sequences of the lytA alleles from strains 1338 (donor) and M41 (recipient) are also shown. Hyphens indicate nucleotides identical to those of the lytAR6 allele. Gray, stippled, and hatched bars represent the regions of lytAMVO2, lytAMVO4, and lytAMVO5, respectively, where recombination took place during transformation. The location of the HincII site used for constructing lytAN1338 and lytAC1338 (see Fig. 3) is also shown.

Additional mutations at the lytA gene are needed to produce a DocT− phenotype.

A 2.4-kb PCR fragment containing the lytA1338 allele was amplified by using oligonucleotides LA_Sau5 and LA_Sau3 and used to transform the M41 strain. Transformants identified by their DocF+ phenotype were isolated and tested for Doc-induced lysis in liquid medium. Two types of DocF+ transformants were found: those that lysed (DocT+ phenotype), and those that did not (DocT−). The lytA alleles of two DocF+ DocT+ transformants (MVO4 and MVO5) and DocF+ DocT− strains (MVO2 and MVO25) were amplified and sequenced. Strains MVO4 and MVO5 have interchanged part of the sequence coding for the C-terminal part of LytAM41, including the nonsense mutation of the recipient strain but not the 6-bp deletion (Fig. 5). In strain MVO2, a complete replacement of the C-terminal coding region of the recipient lytA41 allele by that of the donor lytA1338 allele was found, and consequently, the alleles lytAMVO2 and lytAC1338 (Fig. 3) are identical. A complete replacement of the recipient gene was observed in strain MVO25 (not shown).

To determine the biochemical properties of the new chimeric amidases, exponentially growing cultures of the corresponding pneumococcal transformants were disrupted in a French pressure cell, and amidase activity was assayed in the presence or in the absence of 1% Doc (not shown). As expected, LytAMVO4 and LytAMVO5 were fully active in the presence of the detergent, whereas LytAMVO2 and LytAMVO25 were inhibited by about 40%. These results allowed us to conclude that the lytA1338 allele was the single trait responsible for the DocT− DocF− phenotype of the atypical strain. Moreover, and according to the behavior of the chimeric LytA constructions, this phenotype can be ascribed to the cooperation of various mutations (including the 6-bp deletion) located at the C-terminal domain of the enzymes, as illustrated in the case of strain MVO2.

Phylogenetic position and genetic relatedness of atypical isolates.

To determine the phylogenetic position of the atypical isolates, we amplified and determined a partial nucleotide sequence of the genes coding for the 16S rRNA (data not shown). Sequence comparison revealed more than 97% identity with the 16S rRNA genes of S. pneumoniae and S. mitis, whereas lower similarities were found with other species of the S. mitis group, indicating that all the atypical isolates belong to the S. mitis group of viridans streptococci (29) and that the atypical isolates were closely related to those two species.

Recent works (30, 41) have shown that variations in the sequence of the sodA gene, coding for the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase enzyme (Mn-SOD), is a faithful marker to estimate the similarity between species of the S. mitis group. We amplified by PCR an internal portion (327 bp) of the sodA gene from the clinical isolates reported in this study, the laboratory R6 strain, and S. pneumoniaeT, S. mitisT, and S. oralisT (Fig. 6A). As expected, the sodA sequences from the four latter strains were identical to those reported previously (26, 30, 41). Interestingly, the sodA782 allele is identical to sodAR6 whereas all other alleles from atypical strains differed from those of R6, S. mitisT, or S. oralisT. The reason for this identity might be explained as the result of a single transformation event involving DNA from a typical pneumococcus into the 782 isolate, acting as the recipient. On the other hand, the sodA8224 and sodA11923 alleles were identical.

FIG. 6.

Sequence variation in sodA alleles. (A) Multiple alignment. Each of the sites where the sequence of one or more of the sodA alleles differs from that of the R6 strain is shown. Hyphens represent nucleotides identical to those of the sodAR6 allele. Sites where all of the sequences are identical are not shown. Sites 1, 2, and 3 indicate the first, second, and third nucleotide, respectively, in the codon. The numbering of the codons corresponds to that in a previous publication (53). Spn, Smi, and Sor indicate the sodA alleles from the type strains of S. pneumoniae, S. mitis, and S. oralis, respectively. (B) A matrix of PEDs between aligned sequences is shown. Numbers represent the estimated number of substitutions per 100 bases with no distance correction. Black boxes indicate comparisons with the sodA alleles from the type strains of S. pneumoniae (Spn), S. mitis (Smi), and S. oralis (Sor). The ranges of PEDs compared the atypical alleles with the sodA alleles included in the EMBL database (6 November 2001, last date accessed) and are shown in gray boxes. SPN, S. pneumoniae (26 entries); SMI, S. mitis (24 entries); SOR, S. oralis (40 entries).

Determination of PEDs (Fig. 6B) showed that, with the exception of those two alleles (sodA8224 and sodA11923), the atypical sodA alleles were quite divergent (PEDs ranging between 1.22 and 4.89), suggesting that the corresponding strains were not as closely related as previously suspected. It should be noted that the sodA alleles from typical pneumococcal strains are very similar (PEDs, <1.6) in agreement with that previously reported (30, 41). On the contrary, higher divergences were observed among S. mitis (PED, 0.00 to 5.20) and S. oralis (PED, 0.00 to 7.34) strains, suggesting that these species are less well defined and form a heterogeneous cluster. Even higher divergences were found when comparing the atypical sodA alleles with those from other members of the S. mitis group (not shown). Taking these data into account, from the results of Fig. 6B it can be deduced that, with the exception of strain 782, which contains a typical pneumococcal sodA gene, all other atypical isolates appear to be more related to strains previously classified as S. mitis than to S. pneumoniae (or S. oralis), but they cannot be definitely classified as belonging to any of the three species.

To get further insight into the phylogenetic relationships of the atypical isolates, we used the MLST technique (7), and some housekeeping (neutral) genes were partly sequenced and compared to those included in the pneumococcal MLST web- site (http://mlst.net; 17 December 2001, last date accessed). This database currently contains the partial nucleotide sequences of seven housekeeping genes from over 600 S. pneumoniae isolates. Sequencing of the gki and xpt genes from the 12 atypical isolates revealed that all the alleles differed from those included in the MLST database and that those from strains 11923 and 8224 were identical (not shown). The additional five housekeeping genes (aroE, ddl, gdh, recP, and spi) were also sequenced in the latter two strains, showing identity in every case. However, these alleles differed from those of strain 1338.

These results, taken together, allowed us to conclude that, with the exception of strains 11923 and 8224, each atypical strain represents a different clone according to the nomenclature introduced by Feil and coworkers (8). When the PED values of the alleles of genes ddl, gdh, and spi from strains 11923/8224 and 1338 were compared with those of typical pneumococci, it was observed that they fit within the range calculated for typical alleles included in the MLST database (≤10.66, ≤5.65, and ≤8.44%, respectively). However, the atypical isolates harbored gki and xpt housekeeping alleles with PED values ranging from 2.69 to 10.97% and 1.23 to 10.29%, respectively. Consequently, some of these values were higher than those found for typical pneumococci (PED values of ≤6.25 and ≤8.85%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Traditionally, optochin susceptibility is the primary test used to identify S. pneumoniae in most clinical laboratories outside the United States. However, reference laboratories normally perform additional tests such as the capsular reaction and bile (Doc)-induced lysis. From 5,032 presumptive pneumococcal clinical isolates received in the Spanish Pneumococcal Reference Laboratory between 1988 and 1992, up to 468 isolates were preliminarily classified as atypical pneumococci (9). The main reservoirs of these strains appear to be the conjunctiva, the pharynx, wounds, and peritoneal fluid. As an example, 25% of the isolates from the conjunctiva showed atypical phenotypes. In the same study, it was also found that whereas nearly half of the isolates were penicillin sensitive, more than 90% of the atypical isolates had increased penicillin resistance (MIC ≥ 0.12 μg/ml), and some of them exhibited an extremely resistant phenotype (MIC = 8 μg/ml).

In view of the currently recognized genetic interchange among streptococci (24) leading to the spreading of antibiotic resistance, in this work we studied 12 streptococcal isolates with different levels of resistance that were preliminarily classified as S. pneumoniae on the basis of reactivity with a lytA-specific probe (11). Some of these isolates harbor a serogroup 19 pneumococcal capsule, whereas others were nontypeable. In addition, seven isolates were optochin sensitive. Globally, all of these strains showed an altered autolytic system, as shown by the finding that none of them lysed with 1% Doc, which is a prominent characteristic of typical pneumococci.

Sequence determination of the amplified lytA gene from the atypical isolates demonstrated that, globally, the atypical lytA alleles showed PEDs of about 20% compared with the lytA gene from typical pneumococcal strains (Fig. 1). The atypical alleles also exhibited a remarkable polymorphism (Fig. 2), and high divergence values (PED ≤ 7%) were found compared with the atypical lytA alleles described here as a whole or with those reported previously by Whatmore et al. (52). This was somewhat unexpected, since only limited genetic variation (0.11 to 3.2%) is known to exist among otherwise unrelated S. pneumoniae isolates (51).

The construction of chimeric LytA amidases containing either the N- or C-terminal moieties of a LytA from an atypical isolate showed significant loss of specific activity in both cases (Fig. 3). Moreover, only the chimeric enzyme LytAC1338 was inhibited by Doc. In addition, Doc sensitivity could be specifically attributed to the 2-amino-acid deletion located at the P6 motif of the amidase, as demonstrated here (Fig. 4). Further evidence for this conclusion was obtained from the study of phenotypes and biochemical properties of the amidases from the transformant strains MVO2, MVO4, MVO5, and MVO25 (Fig. 5). A multiple alignment of the LytA sequences revealed noticeable changes at the P6 motif that appeared to be unique to the atypical alleles, that is, the 2-amino-acid deletion already mentioned and several nonconservative amino acid replacements (Fig. 7A). Molecular modeling predicted a profound alteration of the three-dimensional folding of the atypical P6 motif compared to that reported recently for the typical motif (12) (Fig. 7B). This explains why mutations at P6 strongly modify the biochemical properties of the amidase in the atypical LytA. It is interesting that the amidases Ejl and Pal, which are encoded, respectively, by the pneumococcal bacteriophages EJ-1 and Dp-1 and contain identical deletions, are also inhibited by Doc (5, 48).

FIG. 7.

Atypical LytA amidases contain a degenerate P6 motif. (A) Alignment of the C-terminal end of typical and atypical LytA amidases. The sequences of the bacterial LytA amidases were obtained from the EMBL database (10 December 2001, last date accessed). Eighteen typical and 19 atypical amidases, which include those reported here, were aligned by using pileup, and a consensus amino acid sequence of one enzyme of each class is shown. Colons indicate identical amino acid residues, and polymorphic residues are boxed. In the case of typical amidases, the consensus sequence contains amino acid residues present in at least 90% of the aligned enzymes, whereas a higher polymorphism was observed for atypical amidases. The corresponding accession numbers, positions, and changes in the atypical LytAs are: AJ252191, AJ252193, AJ419980, and AJ419981, 253G→R; AJ419974 and AJ419975, 253G→T; AJ252190, 253G→A; AJ419978 and AJ419982, 271L→P; S43511, 281N→H; AJ419977, 282A→V; AJ419978, 298T→P; S43511, AJ252191, AJ252192, AJ252193, AJ419977, and AJ419981, 301E→D; S43511, AJ252191, AJ252193, AJ419977, AJ419980, and AJ419981, 302K→R; S43511 and AJ419977, 306/307TV→SI; S43511 and AJ419977, 310E→D; S43511, 315V→M; AJ419976, 316K→I; and AJ419974, 316K→N. Choline-binding residues are indicated with a black triangle. The portions of the sequence that form the first and second strands of the hairpins are marked with an arrow. (B) Predicted three-dimensional folding of the P5 to P7 motifs of an typical LytA amidase lacking two amino acid residues (TG) at positions 290 to 291 (illustration 1) and of the corresponding consensus sequence from an atypical isolate (illustration 2). For simplicity, only the α-carbon chains are shown. The blue lines correspond to the modified amidases, whereas the folding of a typical LytA enzyme that has been experimentally determined (12) is drawn in yellow. Three different rotations of the models are shown.

Phages, either lytic or temperate, might be the natural reservoir for the spreading of the altered lytA alleles found in atypical isolates. Díaz et al. (5) reported the isolation of a temperate phage, EJ-1, from atypical strain 101. The Ejl amidase is very similar to that of the host (LytA101) and shares, as indicated above, many of its biochemical properties. Furthermore, the Pal amidase, encoded by the lytic phage Dp-1 (21), is a chimeric lysin of intergeneric origin whose C-terminal domain is highly similar to that of LytA, whereas the N-terminal domain is homologous to that of the lysin of the phage BK5-T, which infects Lactococcus lactis (48). On the contrary, other lytic phages, namely Cp-1 and Cp-9, encode choline-dependent lysozymes (not amidases), but their C-terminal domains also have the 6-bp deletion characteristic of atypical LytA amidases (14, 20).

Previous and current findings taken together strongly suggest that very localized recombination events might have occurred between the wild-type lytA gene and other choline-binding enzymes, likely as the result of interchanges with genes carried by pneumococcal phages. An alternative possibility, though not mutually exclusive, is drawn by taking into account the well-documented presence of remnants of the lytA gene in various S. pneumoniae strains (34). These remnants could also provide an ideal background for site-specific recombination that would not affect the integrity of the lytA genes native to the host and the integrative phage HB-3 when a lysogenic situation is generated (42, 43). It has been suggested that localization of the bacterial attB close to these remnants may serve to incorporate the modified lytA genes when abnormal excisions of HB-3 take place (42). Later, this and possibly other phages might infect species closely related to pneumococcus that would incorporate these remodeled genes, which might provide evolutionary advantages to the new variants, into their genome.

An observation of potential practical interest is that the atypical pneumococci lysed when 1% Triton X-100 was used instead of Doc, because in contrast to the inhibitory effect of Doc, Triton X-100 stimulates amidase activity (6). This finding suggested that, for clinically relevant isolates showing a DocT− phenotype, the same test should be carried out with Triton X-100. This rapid, simple, and inexpensive assay would allow recognition of most of the atypical strains and their differentiation from closely related species such as S. mitis and S. oralis. The fact that the 1078 strain did not lyse with Triton X-100 suggests that a critical level of autolytic activity must be reached to induce cell lysis even in the presence of this detergent, and therefore, it is important to consider that some atypical pneumococci could still elude this test. However, a reasonable survey study should be performed to ensure that other nonpneumococcal streptococci are uniformly negative to the lytic action of Triton X-100.

It has been documented that pneumococcal strains that exhibit alterations in their lytic systems appear to contribute to higher morbidity and mortality during infection by playing a role in shaping the course of pneumococcal meningitis (50). The atypical strains studied here contain altered forms of LytA that make them refractory to the lytic effect of detergents, although they are still capable of autolysing at the stationary phase of culture (Lyt+ phenotype), at least under laboratory conditions. Obviously, the phenotypic variations induced by the LytA-like amidases studied here reflect an alteration in their lytic behavior that should influence the pathogenic properties of these strains compared with typical pneumococci and with other species of the S. mitis group. From the above data, we believe that the strains studied here are of pathogenic potential and might act as sources of DNA in recombination events generating new alleles under high selective pressure, e.g., antibiotic treatment, which means that they constitute a pool of variant DNAs.

The detailed molecular characterization of the atypical LytA autolysins, the 16S rRNA and the sodA sequencing, as well as the MLST analysis suggest that the strains studied here, although not typical pneumococcal strains, represent a quite diverse pool of organisms closely related to S. pneumoniae. It should be kept in mind that 16S rRNA sequences can be used routinely to distinguish and establish relationships between genera and well-resolved species (13). In this sense, sodA sequencing has contributed to a better identification at the species level among streptococci (41). However, in the particular case of streptococci belonging to the S. mitis group, it is very difficult to establish the strict limits between species, since the wide interchange of genetic information by different mechanisms of transformation and recombination (including infection by the same bacteriophages) that is facilitated by the possibility of sharing the same habitats may originate a panoply of strains with hybrid characteristics.

Finally, because the LytA amidase is an important pathogenic trait that may allow the strains to became adapted to different physiological circumstances and/or niches and because it shares with many other proteins a modular structure containing a common choline-binding domain, this enzyme provides an excellent reference system to follow its distribution and evolution within the S. mitis group of streptococci. In addition, this study can help not only to resolve diagnostic problems but also to understand the pathogenic potential of the different species of the S. mitis group. In fact, atypical pneumococci are indeed a heterogeneous population of related but not true pneumococci that may prove to be a new species.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants BMC2000-1002 from the Dirección General de Investigación, 08-2/0014/91 from the Comunidad de Madrid, and the Contrato Programa-Grupos Estratégicos of the Comunidad de Madrid.

We thank E. Cano and M. Carrasco for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba, T., and O. Schneewind. 1998. Targeting of muralytic enzymes to the cell division site of Gram-positive bacteria: repeat domains direct autolysin to the equatorial surface ring of Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 17:4639-4646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denys, G. A., and R. B. Carey. 1992. Identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae with a DNA probe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2725-2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devereux, J., P. Haeberli, and O. Smithies. 1984. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:387-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Díaz, E., R. López, and J. L. García. 1990. Chimeric phage-bacterial enzymes: a clue to the modular evolution of genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:8125-8129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Díaz, E., R. López, and J. L. García. 1992. EJ-1, a temperate bacteriophage of Streptococcus pneumoniae with a Myoviridae morphotype. J. Bacteriol. 174:5516-5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Díaz, E., R. López, and J. L. García. 1992. Role of the major pneumococcal autolysin in the atypical response of a clinical isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 174:5508-5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enright, M. C., and B. G. Spratt. 1998. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology 144:3049-3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feil, E. J., J. Maynard Smith, M. C. Enright, and B. G. Spratt. 2000. Estimating recombinational parameters in Streptococcus pneumoniae from multilocus sequence typing data. Genetics 154:1439-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenoll, A. 1994. Ph.D. thesis. Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain.

- 10.Fenoll, A., C. Martín Bourgon, R. Muñoz, D. Vicioso, and J. Casal. 1991. Serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates causing systemic infections in Spain, 1979-1989. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:56-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenoll, A., J. V. Martínez-Suárez, R. Muñoz, J. Casal, and J. L. García. 1990. Identification of atypical strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae by a specific DNA probe. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 9:396-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández-Tornero, C., R. López, E. García, G. Giménez-Gallego, and A. Romero. 2001. A novel solenoid fold in the cell wall anchoring domain of the pneumococcal virulence factor LytA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:1020-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox, G. E., J. D. Wisotzkey, and P. J. Jurtshuk. 1992. How close is close: 16S rRNA sequence identity may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42:166-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García, E., J. L. García, P. García, A. Arrarás, J. M. Sánchez-Puelles, and R. López. 1988. Molecular evolution of lytic enzymes of Streptococcus pneumoniae and its bacteriophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:914-918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García, E., J. L. García, P. García, C. Ronda, J. M. Sánchez-Puelles, and R. López. 1987. Molecular genetics of the pneumococcal amidase: characterization of lytA mutants, p. 189-192. In J. J. Ferreti and R. Curtis III (ed.), Streptococcal genetics. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 16.García, E., J. L. García, C. Ronda, P. García, and R. López. 1985. Cloning and expression of the pneumococcal autolysin gene in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 201:225-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García, E., C. Ronda, J. L. García, and R. López. 1985. A rapid procedure to detect the autolysin phenotype in Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 29:77-81. [Google Scholar]

- 18.García, P., J. L. García, E. García, and R. López. 1986. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the pneumococcal autolysin gene from its own promoter in Escherichia coli. Gene 43:265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García, P., M. P. González, E. García, J. L. García, and R. López. 1999. The molecular characterization of the first autolytic lysozyme of Streptococcus pneumoniae reveals evolutionary mobile domains. Mol. Microbiol. 33:128-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García, P., A. C. Martín, and R. López. 1997. Bacteriophages of Streptococcus pneumoniae: a molecular approach. Microb. Drug Resist. 3:165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García, P., E. Méndez, E. García, C. Ronda, and R. López. 1984. Biochemical characterization of a murein hydrolase induced by bacteriophage Dp-1 in Streptococcus pneumoniae: comparative study between bacteriophage-associated lysin and host amidase. J. Bacteriol. 159:793-796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakenbeck, R., N. Balmelle, B. Weber, C. Gardès, W. Keck, and A. de Saizieu. 2001. Mosaic genes and mosaic chromosomes: intra- and interspecies genomic variation of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 69:2477-2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of E. coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Håvarstein, L. S., R. Hakenbeck, and P. Gaustad. 1997. Natural competence in the genus Streptococcus: evidence that streptococci can change pherotype by interspecies recombinational exchanges. J. Bacteriol. 179:6589-6594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Höltje, J. V., and A. Tomasz. 1976. Purification of the pneumococcal N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase to biochemical homogeneity. J. Biol. Chem. 251:4199-4207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoskins, J., W. E. Alborn, J. Arnold, L. C. Blaszczak, S. Burgett, B. S. DeHoff, S. T. Estrem, L. Fritz, D.-J. Fu, W. Fuller, C. Geringer, R. Gilmour, J. S. Glass, H. Khoje, A. R. Kraft, R. E. Lagace, D. J. LeBlanc, L. N. Lee, E. J. Lefkowitz, J. Lu, P. Matsushima, S. M. McAhren, M. McHenney, K. McLeaster, C. W. Mundy, T. I. Nicas, F. H. Norris, M. O'gara, R. B. Peery, G. T. Robertson, P. Rockey, P.-M. Sun, M. E. Winkler, Y. Yang, M. Young-Bellido, G. Zhao, C. A. Zook, R. H. Baltz, R. Jaskunas, P. R. J. Rosteck, P. L. Skatrud, and J. I. Glass. 2001. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183:5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inouye, S., and M. Inouye. 1985. Up-promoter mutations in the lpp gene of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:3101-3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jedrzejas, M. J. 2001. Pneumococcal virulence factors: structure and function. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:187-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamura, Y., X.-G. Hou, F. Sultana, H. Miura, and T. Ezaki. 1995. Determination of 16S rRNA sequences of Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus gordonii and phylogenetic relationships among members of the genus Streptococcus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:406-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawamura, Y., R. A. Whiley, S.-E. Shu, T. Ezaki, and J. M. Hardie. 1999. Genetic approaches to the identification of the mitis group within the genus Streptococcus. Microbiology 145:2605-2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kellogg, J. A., D. A. Bankert, C. J. Elder, J. L. Gibbs, and M. C. Smith. 2001. Identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae revisited. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3373-3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacks, S., and R. D. Hotchkiss. 1960. A study of the genetic material determining an enzyme activity in Pneumococcus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 39:508-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.López, R., E. García, P. García, and J. L. García. 1997. The pneumococcal cell wall degrading enzymes: a modular design to create new lysins? Microb. Drug Resist. 3:199-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lund, E., and J. Henrichsen. 1978. Laboratory diagnosis, serology and epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Methods Microbiol. 12:241-262. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchesi, J. R., T. Sato, A. J. Weightman, T. A. Martin, J. C. Fry, S. J. Hiom, and W. G. Wade. 1998. Design and evaluation of useful bacterium-specific PCR primers that amplify genes coding for bacterial 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:795-799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAvin, J. C., P. A. Reilly, R. M. Roudabush, W. J. Barnes, A. Salmen, G. W. Jackson, K. K. Beninga, A. Astorga, F. K. McCleskey, W. B. Huff, D. Niemeyer, and K. L. Lohman. 2001. Sensitive and specific method for rapid identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae using real-time fluorescence PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3446-3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosser, J. L., and A. Tomasz. 1970. Choline-containing teichoic acid as a structural component of pneumococcal cell wall and its role in sensitivity to lysis by an autolytic enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 245:287-298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mundy, L. S., E. N. Janoff, K. E. Schwebke, C. J. Shanzholtzer, and K. E. Willard. 1998. Ambiguity in the identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae: optochin, bile solubility, quellung, and the AccuProbe DNA tests. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 109:55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pikis, A., J. M. Campos, W. J. Rodriguez, and J. M. Keith. 2001. Optochin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: mechanism, significance, and clinical implications. J. Infect. Dis. 184:582-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, S. Coulon, P. Berche, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 1998. Identification of streptococci to species level by sequencing the gene encoding the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:41-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romero, A., R. López, and P. García. 1992. The insertion site of the temperate phage HB-746 is located near the phage remnant in the pneumococcal host chromosome. J. Virol. 66:2860-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romero, A., R. López, and P. García. 1990. Sequence of the Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteriophage HB-3 amidase reveals high homology with the major host autolysin. J. Bacteriol. 172:5064-5070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 45.Sánchez-Puelles, J. M., C. Ronda, J. L. García, P. García, R. López, and E. García. 1986. Searching for autolysin functions. Characterization of a pneumococcal mutant deleted in the lytA gene. Eur. J. Biochem. 158:289-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sánchez-Puelles, J. M., J. M. Sanz, J. L. García, and E. García. 1992. Immobilization and single-step purification of fusion proteins using DEAE-cellulose. Eur. J. Biochem. 203:153-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheehan, M. M., J. L. García, R. López, and P. García. 1997. The lytic enzyme of the pneumococcal phage Dp-1: a chimeric lysin of intergeneric origin. Mol. Microbiol. 25:717-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shockman, G. D., and J.-V. Höltje. 1994. Microbial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases, p. 131-166. In J.-M. Ghuysen and R. Hakenbeck (ed.), Bacterial cell wall. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 50.Tuomanen, E., H. Pollack, A. Parkinson, M. Davidson, R. Fackland, R. Rich, and O. Zak. 1988. Microbiological and clinical significance of a new property of defective lysis in clinical strains of pneumococci. J. Infect. Dis. 158:36-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whatmore, A. M., and C. G. Dowson. 1999. The autolysin-encoding gene (lytA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae displays restricted allelic variation despite localized recombination events with genes of pneumococcal bacteriophage encoding cell wall lytic enzymes. Infect. Immun. 67:4551-4556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whatmore, A. M., A. Efstratiou, A. P. Pickerill, K. Broughton, G. Woodard, D. Sturgeon, R. George, and C. G. Dowson. 2000. Genetic relationships between clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus mitis: characterization of “atypical” pneumococci and organisms allied to S. mitis harboring S. pneumoniae virulence factor-encoding genes. Infect. Immun. 68:1374-1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yesilkaya, H., A. Kadioglu, N. Gingles, J. E. Alexander, T. J. Mitchell, and P. W. Andrew. 2000. Role of the manganese-containing superoxide dismutase in oxidative stress and virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 68:2819-2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]