Abstract

Background and Aims:

Primary biliary cholangitis is a rare, progressive liver disease. Obeticholic acid (OCA) received accelerated approval for treating patients with primary biliary cholangitis in whom ursodeoxycholic acid failed, based on a surrogate endpoint of reduction in ALP. Analysis of the long-term safety extension with 2 external control groups demonstrated a significant increase in event-free survival in OCA-treated patients. This fully real-world evidence study assessed the effect of OCA treatment on clinical outcomes.

Approach and Results:

This trial emulation used data from the Komodo Healthcare Map claims database linked to US national laboratory, transplant, and death databases. Patients with compensated primary biliary cholangitis and intolerance/inadequate response to ursodeoxycholic acid who initiated OCA therapy were compared with patients who were OCA-eligible but not OCA-treated. The primary endpoint was time to the first occurrence of death, liver transplant, or hospitalization for hepatic decompensation, analyzed using a propensity-score weighted Cox proportional hazards model. Baseline prognostic factors were balanced using standardized morbidity ratio weighting. For the primary analysis, 4174 patients contributed 11,246 control index dates, and 403 patients contributed OCA indexes. Weighted groups were well balanced. Median (95% CI) follow-up in the OCA and non-OCA arms was 9.3 (8.4–10.6) months and 17.5 (16.2–18.6) months (weighted population; censored at discontinuation). Eight events occurred in the OCA arm and 32 in the weighted control (HR = 0.37; 95% CI = 0.14–0.75; p < 0.001). Effects were consistent for each component of the composite endpoint.

Conclusions:

We identified a 63% reduced risk of hospitalization for hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, or death in OCA-treated versus non–OCA-treated individuals.

Trial Registration:

HEROES; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05292872.

Keywords: confirmatory trial, death, hepatic decompensation, liver disease, liver transplant

INTRODUCTION

The gold standard for establishing drug efficacy and safety is the replication of intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).1 Randomization is used to balance groups on baseline variables and protect against systematic bias. By assessing differences in outcomes between treatment groups, ITT analyses preserve randomization. Appropriately implemented, blinding can eliminate investigator bias.2 Finally, replication ensures the effect is reproducible. However, RCTs may often be infeasible because of issues related to practical implementation challenges and ethical concerns. Chance imbalance in baseline risk factors and protocol nonadherence can obscure treatment effects. Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, estimates obtained from RCTs may lack generalizability because the patients studied are often highly selected, and the RCT environment may be dissimilar to typical routine care settings.3

RCTs conducted in rare diseases face additional, unique challenges. With a small patient pool, recruitment can be difficult and protracted. In slow-progressing diseases, long follow-ups can make retention difficult, especially for event-driven trials. If a medication becomes commercially available during the RCT, as happens with accelerated/conditional approval,4 patients/physicians who do not observe improvement may withdraw from the study in favor of definite treatment with the commercial drug. When a drug is effective, this can disproportionately affect patients randomly assigned to the placebo group.

There has been increasing recognition that real-world evidence (RWE) studies, such as trials with external control arms or fully real-world trial emulation, can be a valid alternative for assessing drug efficacy and safety.5–8 In observational studies, without the benefit of randomization, statistical approaches must be used to balance treated and untreated groups with respect to baseline risk. As with RCTs, replication is essential to protect against chance findings. However, observational studies are subject to various types of bias.9 Statistical techniques such as propensity score methods do not always achieve adequate balance between groups, and balance on observed variables does not guarantee balance on important unmeasured variables. Because patients and physicians are not blinded to the treatment, it is not possible to rule out bias introduced by knowledge of the treatment or disease state. Although RWE has been used for decades to assess drug safety,10 its use by regulators to support drug efficacy has been sporadic and largely limited to ultra-rare disease and pediatric and oncology indications.11 Recent regulatory RWE draft guidance documents have outlined strict requirements for the conduct of real-world studies for regulatory use, adopting with modification the rules governing the conduct of RCTs.10,12–14

The goal of the current study, HEROES, was to conduct a fully real-world trial emulation examining the effect of obeticholic acid (OCA) treatment on clinical outcomes in patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), a rare chronic liver disease characterized by progressive bile duct damage, affecting 100,000–150,000 patients in the United States.15,16 OCA received accelerated approval for treatment of patients with PBC who are intolerant or have had inadequate response to first-line treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA).17 A long-term safety extension study of the pivotal, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (POISE; NCT01473524) with 2 external control arms demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in death, liver transplant, and hepatic decompensation in OCA-treated subjects (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21–0.85).18 Subsequently, a postmarketing, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (COBALT; NCT02308111) was stopped on the basis of the determination by the data safety and monitoring board that the trial was infeasible and did not demonstrate clinical benefit.19 We attempted to emulate the results observed in POISE with real-world data in accordance with the recently released US Food and Drug Administration draft guidance on RWE studies and data. Because POISE was not designed to investigate fibrate treatment and excluded patients receiving fibrates, they were also excluded from HEROES.

METHODS

Data sources and participants

This study used the Komodo Healthcare Map database, a nationally representative, open-source, longitudinal database that includes deidentified claims-based health care encounters from 330 million insured individuals across all 50 US states.20 Komodo includes data on provider visits, laboratory tests, procedures, imaging, and prescriptions. Claims data in Komodo were linked with laboratory data from LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics, which together account for more than half of outpatient laboratories in the United States. Laboratory tests were run at regional laboratories. National LabCorp upper and lower limits of normal (ULN and LLN, respectively) were adopted for all laboratory measures. The data were also linked with data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), a registry that captures US transplant information (including donors, waitlisted candidates, and recipients of transplants), and vital statistics data, which includes the US Social Security Death Index and a national obituary search. All data were linked using Datavant tokenization.21 Data were analyzed using Datavant token 2 as the patient identifier. While data linkages cannot be 100% in real-world data, the precision of linking records on token 2 is ~98.6%.22

Patients aged ≥18 years were included, with either 1 PBC inpatient admission diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision [ICD9/10] code: 571.6 [ICD9]; K74.3 [ICD10]) or 2 PBC outpatient diagnoses separated by at least 1 day23 between June 1, 2016 (date of OCA approval), and December 31, 2021. Patients had to have all laboratory tests and ≥1 ALP measure greater than the ULN (121 U/L) and/or total serum/plasma bilirubin (total bilirubin [TB]) greater than the ULN (1.2 mg/dL) to define an index date, with evidence of one of the following: UDCA intolerance (≤90 d of UDCA use any time before index, with last UDCA use >90 d before index), inadequate UDCA response (≥270 d of UDCA treatment in the year before index, with ≥60 d of UDCA use in the 90 d before index), or UDCA discontinuation (history of UDCA use, with no use for >6 mo before index).

Patients initiating OCA were also included if they switched from UDCA to OCA or had <270 days of UDCA use in the previous year. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were modeled on the POISE phase 3 trial (Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). One important modification was to reduce the ALP inclusion criteria to >ULN, versus >1.67× ULN in POISE. This was done because ~40% of patients initiating OCA in the US Komodo Healthcare Map database had ALP levels <1.67× ULN. Thus, this inclusion criterion was modified to reflect current practice. To adequately assess comorbidity exclusions, patients had to have at least 12 months of continuous enrollment before index.

Exclusion criteria included history or presence of concomitant liver disease (eg, hepatitis B or C infection, primary sclerosing cholangitis, alcoholic liver disease, HCC, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatopulmonary syndrome, portopulmonary syndrome, Paget’s disease, or Gilbert’s syndrome) or hepatic decompensation events (eg, variceal bleeding, ascites, hepatic hydrothorax, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and HE) before the index date. Patients with medical conditions that could cause nonhepatic increases in ALP (eg, bone fractures) within 3 months before the index date, history of liver transplant before the index date, or evidence of OCA, fenofibrate, or bezafibrate use before the index date were also excluded.

Study design

This study used a trial emulation design to evaluate the effect of OCA treatment on time to the first occurrence of hospitalization for hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, or death (Figure 1).7,24 At each eligible visit, the emulated trials would each randomly assign patients who had not yet initiated OCA to receive either OCA or remain on non-OCA treatment. In each subsequent trial, patients not yet assigned to receive OCA in a previous trial would be repeatedly randomly assigned to treatment as long as they continued to meet eligibility criteria. In this hypothetical experiment, once a patient is randomly assigned to receive OCA, they are no longer eligible for further randomization.24 We emulated this trial in the following way: each time a patient had a health care visit that met inclusion/exclusion criteria and had no history of treatment with OCA, that visit contributed a control observation and associated index date from which the patient was followed to the first occurrence of a composite endpoint, censoring at initiation of PBC treatment (OCA, fibrates, or UDCA [if not receiving UDCA at index]); loss to follow-up through disenrollment; or end of study. In this way, a single patient was able to contribute more than 1 control index.25 If the eligible visit resulted in the first fulfillment of an OCA prescription, the patient contributed an OCA treatment index to the study on the date of the prescription fulfillment. Because OCA-treated patients may be prescribed drug holidays in response to intercurrent events (such as pruritus), we required patients initiating OCA to have no history of use. Therefore, each patient could contribute only a single OCA index, after which they could not contribute subsequent OCA or non-OCA indexes. By allowing patients to contribute multiple indexes to the analytic data set, we increased the precision of estimated treatment effects, which can be crucial in rare disease studies but must address within-subject correlation in the statistical analysis. The decision for OCA initiation represents the index date for the OCA treatment arm/cohort. The multiple index dates of the comparator arm represent multiple opportunities when patients in that arm could have enrolled in a trial or initiated second-line therapy.

FIGURE 1.

Design of HEROES study. This real-world outcome study emulated a sequence of trials to assess the effect of OCA treatment on time to hospitalization for hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, or death, in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Patients were randomly assigned to either no-OCA treatment (control, top row) or OCA treatment (bottom row). At health care visits, eligibility was assessed (ineligible, open diamonds; eligible, solid diamonds). For eligible patients without a history of OCA treatment, the visit contributed a control observation and follow-up (orange arrows) started from the visit date (control index date; orange diamonds) until the first occurrence of a clinical event (study endpoint), censor event, or end of follow-up in the control arm or initiation of OCA in the OCA arm. Similarly, for OCA-treated patients, follow-up (green arrow) started from the date of the first dose (OCA index date; green diamond) until the first occurrence of a clinical event, censor event, or end of follow-up. All eligible patients were required to be enrolled at least 12 months before the control or OCA initiation index date (preindex period) to assess comorbidity exclusions. aControl indexes were censored if a patient initiated OCA therapy, if a patient initiated fibrate therapy, or if UDCA was reinitiated for patients who had discontinued the therapy for >6 months. bOCA-treated indexes were censored 90 days after OCA discontinuation, or if fibrates were initiated. Abbreviations: OCA, obeticholic acid; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid.

Our primary analysis targeted a per-protocol (or “as-treated”) estimand; in other words, the effect if patients were randomized and remained adherent to treatment.26 To estimate this, we censored patients if they crossed over to a different treatment. A control index was censored if a patient initiated commercial PBC treatment: UDCA (if not receiving UDCA at baseline) or second-line treatment with OCA or fibrates. This was done to avoid confounding from patients in the comparator group getting a second-line treatment for PBC that would be likely to affect outcomes.17 OCA-treated patients were censored if they initiated another PBC therapy (such as fibrates), out of similar concerns for confounding. Patients in the OCA arm were also censored 90 days after the treatment discontinuation date. The 90-day period was prespecified in the protocol by a panel of 9 expert hepatologists as the maximal period OCA anticholestatic effects would be observed, given a 24-hour half-life, allowing for hepatic recirculation, and the possibility of reduced clearance in the face of mild or moderate obstruction.27

Primary and exploratory endpoints

The primary endpoint was the first occurrence of hospitalization for hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, or death. The date of death was derived from the Social Security Death Index and a national obituary search and adjudicated against claims data. The date of the liver transplant was derived from the OPTN transplant database and adjudicated against claims data. Decompensation was derived from claims data, defined as the first occurrence of hospitalization with admission for ascites, gastroesophageal varices with bleeding, or HE (Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). A board-certified hepatologist and epidemiologist adjudicated mismatches between data sources. Exploratory endpoints included time to each individual component of the composite endpoint using a competing risk model.

Statistical analysis

The primary statistical analysis used a weighted Cox proportional hazards model with standardized morbidity ratio (SMR) weights to target the effect of OCA treatment. The SMR weights were computed using estimated propensity scores derived from logistic regression. This approach weighted the control observations by their inverse odds of being treated with OCA, conditional on their clinical and demographic characteristics, thus standardizing the control observations to resemble the OCA-treated observations with respect to potential confounders.28 The propensity scores were estimated with a logistic regression model that included baseline sex, age, index year before and after COVID (<2020; ≥2020), laboratory measures (ALP, TB, ALT, AST, and platelet count), Charlson Comorbidity Index, cirrhosis diagnosis (yes/no), clinical evidence of portal hypertension defined as a diagnosis and/or platelets <150,000 and/or nonbleeding varices (yes/no), UDCA treatment (yes/no), time since intolerance or inadequate response to UDCA, and health insurance type as predictors (Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). Cirrhosis was identified programmatically from claims having any of the ICD-10 codes for liver or biliary cirrhosis (K74.5, K74.60, and K74.69) and evidence of liver imaging (eg, Current Procedural Terminology code 91200 for liver elastography, ICD-10 code BF35ZZZ for MRI of the liver) and/or biopsy (eg, Current Procedural Terminology codes 47000 and 47001) within 6 months of diagnosis of cirrhosis. Insurance type included government-sponsored programs (federal-level Medicare, state-level Medicaid, and Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligible), as well as employer-sponsored commercial insurance and self-insurance (including government-subsidized insurance exchanges). Standardized mean differences were computed for baseline variables before and after weighting, and a post-weighting threshold of ±0.10 was prespecified to indicate adequate balance. Inference for the HR was conducted using a nonparametric grouped bootstrap with 1000 replicates that addressed the within-patient correlation of outcomes induced by the study design.29 A 95% CI was estimated by taking the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution. A 2-tailed p value was calculated for the HR using the nonparametric bootstrap approach.30 A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The median and 95% CI follow-up duration was estimated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method.

Individual components of the composite endpoint were analyzed separately in exploratory analyses. For death (all-cause), the weighted analysis was identical to that for the primary effect size estimation. For liver transplantation, death was treated as a competing event using a Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazards model.31 The weighted analysis for hepatic decompensation was similar but treated death and liver transplantation as competing events.

Sensitivity analyses

Two analyses were conducted that targeted ITT-type estimands. The first allowed OCA-treated patients to discontinue treatment and did not censor OCA-treated patients at discontinuation. The second allowed OCA-treated patients to discontinue treatment or initiate UDCA and untreated patients to initiate OCA or UDCA and thus did not censor OCA patients at discontinuation and did not censor untreated patients if they initiated treatment. Prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted by sex, age (<55; ≥55 y), US region (South, Northeast, Midwest, and West), baseline cirrhosis (yes/no), baseline portal hypertension (yes/no), and pre-/post-COVID (index <2020; ≥2020). Quantitative bias analyses were performed on the primary endpoint to explore the effect of a hypothetical unmeasured confounder on results using a single-variable multidimensional approach appropriate to the small sample size.32,33 Following best practices,34 the prevalence of the confounder was set at 5% and 50%, with 50% representing the differential prevalence with maximal effect on outcomes. The primary HR was tested at the observed value and the upper end of the 95% CI. The association between the hypothetical confounder and treatment, and the confounder and outcomes, varied from HR 0.1 to 0.9.

Inverse probability of censoring weighting analysis was also performed to account for potential informative censoring using the method of Robins and Finkelstein.35 Censoring probabilities were estimated using a pooled logistic regression model that included both baseline and time-varying covariates (eg, TB, ALP, ALT, AST, platelets, and Charlson Comorbidity Index) that were updated in 30-day follow-up intervals. Censoring weights were stabilized by the marginal probability of censoring. The censoring weights were multiplied by the propensity score weights (SMR weights) and applied to a Cox proportional hazards model that included only the treatment assignment.

RESULTS

Study population

We identified 143,197 patients who had an inpatient or outpatient claim with an associated ICD9/10, code for PBC, of whom 97,648 had the requisite 1 inpatient claim or 2 outpatient claims (separated by at least 1 day) (Supplemental Figure S1A, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). This initial reduction excluded patients with a single outpatient ICD9/10 code, typically used as rule-out diagnoses. For control patients, 54,473 had the required laboratory values in the Quest Diagnostics and/or LabCorp outpatient laboratory databases (Supplemental Figure S1B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). This conformed with the percentage of outpatient tests conducted in the United States by these 2 leading commercial laboratories. There were no significant differences between patients with and without laboratory tests on any of the measured baseline variables. Of the patients with laboratory data, 40,994 had at least 1 elevated ALP and/or TB level, and 16,528 had at least 1 year of data before an elevated ALP and/or TB. Given the nature of the US health insurance system, in which patients transfer between insurers, this decrement was within the expected range. Of these patients, 12,081 had a history of UDCA use, of whom 6932 met the prespecified criteria for UDCA intolerance, inadequate response, or discontinuation, and thus would qualify as eligible for OCA therapy under the current label and indication. This prevalence of UDCA use is similar to other analyses of patients with PBC in the US health care system.16 After the application of the comorbid exclusions from the POISE trial, upon which this study was modeled, there were 4535 patients in the control group (Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641).

Of the 2552 patients who initiated OCA, 1263 had the required laboratory values, 955 had at least 1 elevated ALP and/or TB level; 630 had at least 1 year of data before an elevated ALP and/or TB; and 603 had a history of UDCA use and met the prespecified criteria for UDCA intolerance, inadequate response, or discontinuation/switching/<270 days UDCA use in the previous year. After comorbid exclusions, there were 432 patients in the OCA-treated group (Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641).

The proportion of patients with cirrhotic disease who were OCA-treated reflects the real-world use of OCA as a second-line PBC treatment. Of the patients with cirrhotic disease, diagnosis was confirmed by liver biopsy and was performed in 29/214 (13.6%) OCA-treated patients and 234/1885 (12.4%) non–OCA-treated patients, liver imaging was performed in 180/214 (84.1%) OCA-treated patients and 1641/1885 (87.1%) non–OCA-treated patients, and both liver biopsy and imaging were performed in 5/214 (2.3%) OCA-treated patients and 10/1885 (0.5%) non–OCA-treated patients. Among all patients in the weighted population (OCA-treated, N = 203, non–OCA-treated, N = 1756), liver imaging tests included ultrasound (OCA-treated, n = 143 [70.4%] and non–OCA-treated, n = 1170 [66.6%]), MRI scans (OCA-treated, n = 21 [10.3%] and non–OCA-treated, n = 236 [13.4%]), elastography (OCA-treated, n = 9 [4.4%] and non–OCA-treated, n = 76 [4.3%]), and CT scans (OCA-treated, n = 7 [3.4%] and non–OCA-treated, n = 81 [4.6%]).

The logistic regression and propensity score density functions before and after SMR weighting are shown in Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641 and Supplemental Figure S2, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641. Note that 361 control and 29 OCA-treated patients were missing variables temporal to index and were excluded listwise from the logistic regression, producing a final sample for weighting of 403 OCA-treated and 4174 non–OCA-treated controls. All baseline variables fell within the prespecified standardized mean differences of ±0.10 (Supplemental Figure S3, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). Baseline characteristics before and after SMR weighting are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant or clinically meaningful differences in observed variables between the non–OCA-treated and OCA-treated groups after weighting; patients were 91%–92% female with a mean (SD) age of 55.9 (12.6) and 56.2 (10.6) years, respectively. The largest percentage of patients were from the southern United States (46%), and the largest percentage had commercial insurance (48%). Baseline laboratory values were similar between groups: TB was 0.7 mg/dL in both non–OCA-treated and OCA-treated groups; ALP was 294 versus 292 U/L; ALT was 53 versus 52 U/L; AST was 50 versus 49 U/L; albumin was 4.1 g/dL in both groups; and platelet counts were 252 versus 250 counts/mL blood × 1000. The duration of follow-up in the unweighted and weighted populations was similar in both treatment groups. In the non–OCA-treated group (unweighted N = 12,399 indexes and weighted N = 405 indexes), the median (95% CI) follow-up was 15 (14.7–15.4) months in the unweighted population and 17.5 (16.2–18.6) months in the weighted population. In the OCA-treated group (unweighted N = 432 indexes and weighted N = 403 indexes), the median (95% CI) follow-up was 9.3 (8.3–10.4) months and 9.3 (8.4–10.6) months, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Unweighted and SMR-weighted baseline characteristicsa

| Non-OCA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted | SMR-weighted | OCAb | |

| Eligible patients, n | 4535 | 4174 | 403 |

| Indexes, nc | 12,400 | 405.4 | 403 |

| Female, % | 90.2 | 91.1 | 91.6 |

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 61.1 ± 11.7 | 55.9 ± 12.6 | 56.2 ± 10.6 |

| US region, % | |||

| South | 43.8 | 43.3 | 46.2 |

| West | 23.9 | 26.1 | 24.1 |

| Northeast | 22.1 | 20.8 | 20.3 |

| Midwest | 9.7 | 9.4 | 9.4 |

| Insurance, % | |||

| Commercial | 43.4 | 48.2 | 48.1 |

| Medicaid | 12.7 | 18.7 | 18.1 |

| Medicare | 23.6 | 14.4 | 14.9 |

| Self-insured/exchanges | 15.3 | 16.6 | 16.9 |

| Other | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Laboratory, mean ± SD (fraction of ULN or LLN)d | |||

| TB, mg/dL | 0.7 ± 0.4 (0.58× ULN) |

0.7 ± 0.4 (0.58× ULN) |

0.7 ± 0.5 (0.59× ULN) |

| ALP, U/L | 198.2 ± 102.9 (1.64× ULN) |

294.2 ± 152.7 (2.43× ULN) |

292.1 ± 154.2 (2.41× ULN) |

| ALT, U/L | 34.7 ± 28.2 (0.79× ULN) |

52.7 ± 45.6 (1.20× ULN) |

51.5 ± 41.1 (1.17× ULN) |

| AST, U/L | 35.5 ± 23.2 (0.89× ULN) |

49.6 ± 36.5 (1.24× ULN) |

48.8 ± 34.0 (1.22× ULN) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.1 ± 0.4 (1.03× LLN) |

4.1 ± 0.4 (1.03× LLN) |

4.1 ± 0.3 (1.03× LLN) |

| PLT, count/μL blood × 1000 | 243.2 ± 91.4 (1.62× LLN) |

252.2 ± 100.2 (1.68× LLN) |

249.7 ± 94.8 (1.67× LLN) |

| On UDCA at index, % | 63.8 | 72.7 | 72.5 |

| Months from UDCA failure to index | 7.3 ± 13.5 | 1.2 ± 3.2 | 1.1 ± 3.8 |

| Portal HTN, % | 24.8 | 23.4 | 23.6 |

| Cirrhosis, % | 43.1 | 50.5 | 50.4 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 3.7 ± 2.7 | 3.0 ± 2.3 | 3.0 ± 2.3 |

Plus-minus values are mean ± SD.

Represents patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and had the required baseline variables for weighting, 29 patients were not included in the overall weighted OCA group.

All percentages are out of the number of indexes. All means ± SD are at the time of index.

ULN defined per US LabCorp as follows: TB, 1.2 mg/dL; ALP, 121 U/L; ALT, 44 U/L; AST, 40 U/L; albumin, 4 g/dL; PLT, 150,000/μL.

Abbreviations: HTN, hypertension; LLN, lower limit of normal; OCA, obeticholic acid; PLT, platelet count; SMR, standardized morbidity ratio; TB, total bilirubin; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; ULN, upper limit of normal.

All patients (non–OCA-treated and OCA-treated) had evidence of UDCA discontinuation, inadequate UDCA response, or intolerance to UDCA before any index date (Supplemental Table S4, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). Approximately three-quarters of patients in both groups were receiving UDCA at baseline and had an inadequate UDCA response on average 1 month before the index. Approximately half of each group had cirrhosis at baseline, and one-quarter had portal hypertension. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score was 3.0 in both groups.

Primary efficacy endpoint

Figure 2 shows the unweighted (A) and weighted (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for time to death, liver transplant, or hepatic decompensation by treatment group. As shown in Table 2, significantly more events occurred in the non–OCA-treated control group versus the OCA-treated group, regardless of whether the groups were unweighted or weighted or whether events were enumerated by patient count or index count. For the primary analysis, there were 31.8 events (23.0 hepatic decompensations, 7.2 deaths, and 1.6 liver transplants) among 405.4 weighted indexes (7.9%) for controls. In the OCA-treated group, there were 8 events (6 hepatic decompensations, 2 deaths, and no liver transplants) among 403 indexes (2.0%; HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.14–0.75; p < 0.001).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of time to primary endpoint for OCA-treated versus non–OCA-treated patients. This figure illustrates the survival probabilities and number of OCA-treated and non–OCA-treated patients with PBC who are at risk of death, liver transplant, or hospitalization for hepatic decompensation over time. Curves are shown for unweighted control subjects (A) and SMR-weighted control subjects (B). The median (95% CI) follow-up time in the non–OCA-treated group was 15 (14.7–15.4) months in the unweighted population and 17.5 (16.2–18.6) months in the weighted population. In the OCA-treated group, the median (95% CI) follow-up time was 9.3 (8.3–10.4) months and 9.3 (8.4–10.6) months, respectively. Censored data are indicated by + symbols. Abbreviations: OCA, obeticholic acid; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; SMR, standardized morbidity ratio.

TABLE 2.

Main results and sensitivity analysis: adjusted and unadjusted HR for the composite outcome and each component of the composite outcome

| Outcome | Treatment group | Unweighted events | Weighted events | Unweighted HR (95% CI) | Weighted HRa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite | Control | 741 | 31.8 | 0.41 (0.15–0.74) | 0.37 (0.14–0.75) |

| OCA | 8 | 8 | |||

| Death | Control | 217 | 7.2 | — | — |

| OCA | 2 | 2 | |||

| Liver transplant | Control | 19 | 1.6 | — | — |

| OCA | 0 | 0 | |||

| Hepatic decompensation | Control | 505 | 23.0 | — | — |

| OCA | 6 | 6 | |||

| ITT1b | Control | 741 | 31.8 | 0.73 (0.44–1.07) | 0.59 (0.34–0.995) |

| OCA | 24 | 22.0 | |||

| ITT2c | Control | 832 | 35.0 | 0.73 (0.45–1.06) | 0.64 (0.38–1.05) |

| OCA | 24 | 22.0 |

Adjusted HR is estimated using an SMR-weighted Cox proportional hazards model.

OCA-treated patients not censored at discontinuation.

OCA-treated patients not censored at discontinuation and untreated patients not censored if they initiated treatment with OCA, fibrates, or ursodeoxycholic acid.

Abbreviations: ITT, intent-to-treat; NC, not calculated; ND, no data; OCA, obeticholic acid; SMR, standardized morbidity ratio.

Exploratory efficacy analyses

In exploratory analyses, the HRs for time to event for the components of the composite were similar to that of the composite: hepatic decompensation HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.09–0.85; p = 0.012 (Supplemental Tables S5 and S6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641 and Supplemental Figure S4A, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641); death HR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0–1.26; p = 0.12 (Supplemental Table S7, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641 and Supplemental Figure S4B, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). As no liver transplants occurred in the OCA-treated group, an HR could not be computed (Supplemental Tables S8 and S9, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641, and Supplemental Figure S4C, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). For liver transplantation or death, the HR was 0.29 (95% CI, 0–0.86; p = 0.03; Supplemental Table S10, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641 and Supplemental Figure S4D, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). The ITT1 analysis, in which patients receiving OCA were not censored upon treatment discontinuation, showed a statistically significant effect in favor of OCA treatment: HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.34–0.995; p = 0.046 (Supplemental Table S11, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641, and Supplemental Figure S5A, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). The ITT2 analysis, in which OCA-treated patients were not censored upon discontinuation and non–OCA-treated controls were not censored for initiating OCA, fibrates, or UDCA, showed a similar but not statistically significant effect: HR, 0.644; 95% CI, 0.38–1.05; p = 0.072 (Supplemental Table S12, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641, and Supplemental Figure S5b, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641). The results of the per-protocol (or as-treated) estimate using the inverse probability of censoring weighting analysis were also similar (0.52; 95% CI, 0.12–0.82). The weighted and unweighted HRs in these sensitivity analyses fall within the 95% CI of the primary analysis and indicate treatment benefit even in the presence of substantial confounding due to treatment crossover and channeling bias. In subgroup analyses, only the male sex did not have an HR indicative of treatment benefit (Figure 3), although it should be noted there were only 34 male OCA-treated patients. The point estimates from the other subgroup analyses were all <0.75, though smaller sample sizes reduced the precision of these estimates. The weighted HR for the composite outcome of death, liver transplant, or hospitalization for hepatic decompensation in OCA-treated versus non–OCA-treated patients was 0.41 (95% CI, 0.12–1.09, p = 0.068) for patients with cirrhosis and 0.26 (95% CI, 0–0.81; p = 0.022) for patients without cirrhosis (Supplemental Figure 6, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641).

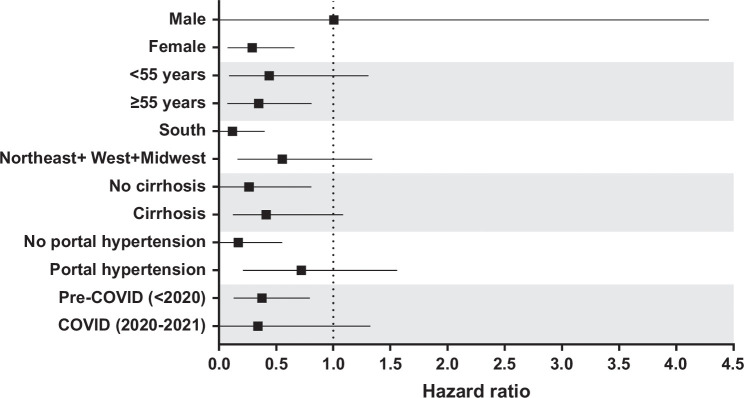

FIGURE 3.

Subgroup analysis of time to primary endpoint for OCA-treated versus non–OCA-treated patients. This figure shows adjusted HRs for time to hospitalization for hepatic decompensation, liver transplant, or death in subgroups of OCA-treated versus non–OCA-treated patients. Adjusted HRs were estimated using an SMR-weighted Cox proportional hazards model. The median (95% CI) follow-up time in the non–OCA-treated group was 15 (14.7–15.4) months in the unweighted population and 17.5 (16.2, 18.6) months in the weighted population. In the OCA-treated group, the median (95% CI) follow-up time was 9.3 (8.3–10.4) months and 9.3 (8.4–10.6) months, respectively. Black squares and whiskers indicate HRs and 95% CIs, respectively. Abbreviations: OCA, obeticholic acid; SMR, standardized morbidity ratio.

Quantitative bias analyses demonstrated that the observed treatment effect was robust even in the face of significant potential confounding (Supplemental Tables S13–S16, http://links.lww.com/HEP/J641).

DISCUSSION

We sought to evaluate the effect of OCA treatment on hepatic outcomes in patients with PBC using a trial emulation approach. We observed a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 63% reduction in relative risk of death, liver transplant, and hepatic decompensation in the OCA-treated group versus comparable non–OCA-treated controls. Numerous sensitivity and supportive analyses were undertaken to test the robustness of the observed treatment effect estimate, varying design and analysis components that could affect bias. The 2 ITT analyses allowed for treatment crossover between groups, with the expected reduction in treatment effect. The resulting HRs continued to suggest treatment benefits, even in unweighted analyses in which confounding was not addressed. In addition, the per-protocol HR estimate using inverse probability of censoring weighting estimation suggested a benefit of OCA treatment. Furthermore, analysis of each component of the primary endpoint showed a similar treatment effect, demonstrating that the observed effect was not driven disproportionately by 1 event type. Quantitative bias analysis explored the conditions under which an unmeasured confounder would render the treatment effect nonbeneficial. It showed that only an unmeasured confounder prevalent in at least half of the population and strongly associated with both exposure and outcomes would have the potential to shift the HR toward the null. This is highly unlikely and supports the robustness of primary results. Finally, an HR indicating treatment benefit was observed in subgroups of patients regardless of disease status or demographics, with the exception of male sex, which only represented a small subgroup of patients (n = 34).

UDCA is the only approved first-line therapy for PBC, with a high frequency of treatment insufficiency. In the 1990s and 2000s, governments implemented incentives for the development of medicines for diseases with high unmet needs. Accelerated and conditional approval on the basis of surrogate endpoints allowed treatments to become available more quickly, on the condition that outcomes studies would be performed to confirm benefit. Paradoxically, this solution has made it more challenging to conduct confirmatory, placebo-controlled trials, especially in rare diseases with small patient populations.36 Substantial progress has been made in the science of real-world data analysis to fill this evidence gap, resulting in increased acceptance by regulators, clinicians, and patients. Early failures to replicate real-world analyses in placebo-controlled trials have been addressed with methodological advances in trial emulation.6 Indeed, the reliability of results within real-world data sets has been shown to be robust, and comparisons of real-world and trial data have shown concordance similar to that observed in replicate clinical trials.6,24,37

In contrast to randomized clinical trials, which often have strict inclusion and exclusion criteria and only follow patients during the trial, real-world data reflect routine patient encounters with health care professionals, including patients receiving OCA as part of standard clinical practice, which are more likely to be representative of the entire patient population.38 The Komodo Healthcare Map database used in HEROES included deidentified data for ~330 million unique patients, 150 million of whom had both medical and pharmacy encounters available. Given the size of and detailed information in the Komodo database and the linkages to laboratory, transplant, and death data, the entire data set not only is a rich source of information to identify patients with PBC but also increases the generalizability of the study results. Specifically, the finding of a 63% reduction in relative risk of severe hepatic outcomes or death in OCA-treated versus non–OCA-treated individuals may help appropriate patients with PBC and their physicians evaluate second-line treatment options when first-line treatment with UDCA fails or is not tolerated.

A strength of this study was that the population from the Komodo database is reflective of real-world clinical practice. In the pivotal POISE trial, patients were specifically selected, whereas those in this real-world population had different access to care, and therefore, the results are more representative of the insured US population. The study population in HEROES was similar to other published studies about the prevalence of PBC, despite the use of different databases and geographies between studies.18,39 In addition, all patients (non–OCA-treated and OCA-treated) had evidence of UDCA discontinuation, inadequate UDCA response, or intolerance to UDCA before any index date. Although this definition allowed the inclusion of patients with any evidence of UDCA use in the year before the index date and who discontinued but had a single ALP or TB elevation, it reflects real-world practice in patients who may experience delays in diagnosis or treatment.

There are limitations to the analysis of real-world data. Potential for errors exists in coding and omissions when using administrative claims-based data, resulting in possibly missing and mismeasured covariates, treatments, and outcomes. Potential also exists for uncontrolled confounding, which we addressed as much as possible with numerous robustness checks. In addition, a limitation of merging multiple real-world data sources is the potential for suspected collisions (ie, deidentified patient records that are programmatically matched across health plans but have the potential to represent the same individual). A sensitivity analysis removing suspected collisions (1% of patients) was conducted and yielded consistent results, and the tokenization procedure employed in HEROES has published precision rates of over 98%.22

Ultimately, whether efficacy is assessed by traditional randomized placebo-controlled trials, by single-arm trials with external control, or by fully real-world trial emulation, the ability to replicate benefit defines treatment efficacy. This is, in fact, how the clinical benefit of first-line UDCA was shown—by real-world confirmation of randomized trial results.36 In the case of OCA, the POISE long-term open-label extension compared OCA-treated patients from the trial with external controls from the Global PBC registry and reported a similar benefit using a nearly identical composite endpoint (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21–0.85).18 The real-world data reported here demonstrate that OCA reduces the risk of death, liver transplant, and hepatic decompensation in appropriate patients with PBC.

Supplementary Material

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data reported here have been supplied by the United Network for Organ Sharing as the contractor for the OPTN. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the US government. Individual, deidentified participant data used in these analyses are being shared with the US Food and Drug Administration as part of the supplemental New Drug Application. Data are available for analysis on request from any qualified investigator after the approval of a protocol and are subject to the data-sharing requirements of Komodo Health, including a signed data access agreement with the HEROES Study Steering Committee and Komodo Health. ©2023 Komodo Health, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction, distribution, transmission or publication is prohibited. Reprinted with permission.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors conceived and designed the analysis. Charles Coombs, Julia Chu, and Jing Li analyzed the data. Tracy J. Mayne and M. Alan Brookhart wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in revising the manuscript, approved the submitted versions, and confirmed the accuracy and completeness of the data and the fidelity of the trial to the protocol.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patients who contributed data to this study. Alexander Simon and Katherine O’Connor, PhD, of MedLogix Communications, LLC, a Citrus Health Group, Inc. company, provided editorial support, which was funded by Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc. funded this study and was involved in the conception, design, conduct, and review of the analysis, in the writing and review of the manuscript, and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

M. Alan Brookhart advises and owns stock in Target RWE. He advises Amgen, Astellas/Seagen, Atara Biotherapeutics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Kite, Gilead, NIDDK, Vertex, AccompanyHealth, Target RWE, and Vertex. He advises and was employed by Intercept at the time they study was conducted. He owns stock in Accompany Health. Tracy J. Mayne was employed by Intercept at the time the study was conducted. Charles Coombs owns stock in and is employed by Syneos Health and Walmart. Alexander Breskin owns stock in and is employed by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Target RWE. Erik Ness was employed by Intercept at the time the study was conducted. He is employed by Madrigal. Leona Bessonova is employed by Intercept. Yucheng Julia Chu consults for and is employed by Intercept. Jing Li is employed by Intercept. Michael W. Fried is employed by and owns stock in Target RWE. Bettina E. Hansen consults for, is on the speakers’ bureau, and received grants from Mirum. She consults for, advises, and received grants from Cymabay, Intercept, and Ipsen. She consults for and advises Pliant. She consults for and received grants from Albireo, Calliditas, and Eiger. She consults for Enyo. She received grants from Gilead. Kris V. Kowdley has received honoraria, fees, equity, research support, and clinical trial grants from AbbVie, Corcept, CymaBay, Enanta, Genfit, Gilead, GSK, Hanmi, HighTide, Inipharm, Intercept, Madrigal, Mirum, Novo Nordisk, NGM Bio, Pfizer, Pliant, Terns, Viking, and 89bio. He advises and received grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Ipsen. He advises Arbormed. He received grants from AstraZeneca and Akero. He receives royalties from UpToDate. David Jones consults for, is on the speakers’ bureau for, and received grants from Advanz and Intercept. He consults for and is on the speakers’ bureau for Abbott, Ipsen, and GSK. He consults for and received grants from Intercept. He consults for Cymabay and Umecrine. He is on the speakers’ bureau for Falk. George Mells received grants from Intercept. Palak J. Trivedi receives institutional salary support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). [This paper presents independent research supported by the Birmingham NIHR BRC based at the University Hospitals Birmingham National Health Service Foundation Trust and the University of Birmingham. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.] Palak J. Trivedi has received grant support from Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Foundation, the LifeArc Foundation, Innovate UK, GSK, Guts UK, PSC Support, Intercept, Falk, Gilead, and Bristol Myers Squibb; has received speaker fees from Intercept and Falk; and has been an advisory board member/consultant for Albireo, CymaBay, Intercept, Ipsen, Falk, GSK, and Pliant. He consults for, advises, is on the speakers’ bureau, and received grants from Advanz. Shaun Hiu received grants from Intercept. James Wason received grants from Intercept. Rachel Smith received grants from Advanz. John D. Seeger is employed by Optum and has stock in UnitedHealth Group (Optum’s parent company). Participation in this project was supported through a research contract between Optum and Intercept. Gideon M. Hirschfield consults for Intercept, Advanz, Ipsen, Cymabay, HIghTide, Kowa, Pliant, Mirum, Gilead, GSK, and Escient. The remaining author has no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ITT, intent-to-treat; LLN, lower limit of normal; OCA, obeticholic acid; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RWE, real-world evidence; SMR, standardized morbidity ratio; TB, total bilirubin; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Brookhart A, et al. Results of the HEROES Study: Treatment efficacy of obeticholic acid on hepatic real-world outcomes in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Presented at: AASLD The Liver Meeting 2022; November 4–8, 2022; Washington, DC.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.hepjournal.com.

Contributor Information

M. Alan Brookhart, Email: alan.brookhart@duke.edu.

Tracy J. Mayne, Email: tjmayne@aol.com.

Charles Coombs, Email: Charles.Coombs@walmart.com.

Alexander Breskin, Email: alex.breskin@gmail.com.

Erik Ness, Email: Erik.ness@hotmail.com.

Leona Bessonova, Email: leona.bessonova@interceptpharma.com.

Yucheng Julia Chu, Email: Julia.Chu-CW@interceptpharma.com.

Jing Li, Email: jing.li@interceptpharma.com.

Michael W. Fried, Email: mfried@med.unc.edu.

Bettina E. Hansen, Email: b.hansen@erasmusmc.nl.

Kris V. Kowdley, Email: kkowdley@liverinstitutenw.org.

David Jones, Email: David.Jones@newcastle.ac.uk.

George Mells, Email: george.mells@nhs.net.

Palak J. Trivedi, Email: p.j.trivedi@bham.ac.uk.

Shaun Hiu, Email: shaun.hiu@newcastle.ac.uk.

Dorcas N. Kareithi, Email: dorcas.kareithi@newcastle.ac.uk.

James Wason, Email: james.wason@newcastle.ac.uk.

Rachel Smith, Email: rachel.smith244@nhs.net.

John D. Seeger, Email: John.Seeger@optum.com.

Gideon M. Hirschfield, Email: gideon.hirschfield@uhn.ca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hariton E, Locascio JJ. Randomised controlled trials—The gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. BJOG. 2018;125:1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman DG, Schulz KF. Statistics notes: Concealing treatment allocation in randomised trials. BMJ. 2001;323:446–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frieden TR. Evidence for health decision making—Beyond randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Code of Federal Regulations . Accelerated approval of new drugs for serious or life-threatening illnesses. CFR Title 21, Part 314, Subpart H., 1992.

- 5.United States Food and Drug Adminisration. Submitting Documents Using Real-World Data and Real-World Evidence to FDA for Drug and Biological Products. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danaei G, Rodriguez LA, Cantero OF, Logan R, Hernan MA. Observational data for comparative effectiveness research: An emulation of randomised trials of statins and primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22:70–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernan MA, Robins JM. Using Big Data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:758–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang SV, Schneeweiss S, Initiative R-D, Franklin JM, Desai RJ, Feldman W, et al. Emulation of randomized clinical trials with nonrandomized database analyses: Results of 32 clinical trials. JAMA. 2023;329:1376–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgado-Rodriguez M, Llorca J. Bias. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:635–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United States Food and Drug Administration. Considerations for the Use of Real-World Data and Real-World Evidence to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Drug and Biological Products. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purpura CA, Garry EM, Honig N, Case A, Rassen JA. The role of real-world evidence in FDA-approved new drug and biologics license applications. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;111:135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States Food and Drug Administration. Data Standards for Drug and Biological Product Submissions Containing Real-World Data Draft Guidance. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.United States Food and Drug Administration. Real-World Data: Assessing Electronic Health Records and Medical Claims Data to Support Regulatory Decision-Making For Drug and Biological Products Draft Guidance. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Food and Drug Administration. Real-World Data: Assessing Registries to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Drug and Biological Products Draft Guidance. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Younossi ZM, Bernstein D, Shiffman ML, Kwo P, Kim WR, Kowdley KV, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary biliary cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:48–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu M, Zhou Y, Haller IV, Romanelli RJ, VanWormer JJ, Rodriguez CV, et al. Increasing prevalence of primary biliary cholangitis and reduced mortality with treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1342–1350 e1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nevens F, Andreone P, Mazzella G, Strasser SI, Bowlus C, Invernizzi P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of obeticholic acid in primary biliary cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:631–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murillo Perez CF, Fisher H, Hiu S, Kareithi D, Adekunle F, Mayne T, et al. Greater transplant-free survival in patients receiving obeticholic acid for primary biliary cholangitis in a clinical trial setting compared to real-world external controls. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:1630–1642 e1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kowdley KV, Brookhart MA, Hirschfield GM, Coombs C, Malecha E, Mayne T, et al. Efficacy of obeticholic acid (OCA) vs placebo and external control (EC) on clinical outcomes in primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). Hepatology. 2023;77:E165. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komodo Health. Komodo Healthcare Map. 2019. Accessed September 27, 2024.https://www.komodohealth.com/healthcare-map

- 21.Kiernan D, Carton T, Toh S, Phua J, Zirkle M, Louzao D, et al. Establishing a framework for privacy-preserving record linkage among electronic health record and administrative claims databases within PCORnet((R)), the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network. BMC Res Notes. 2022;15:337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernstam EV, Applegate RJ, Yu A, Chaudhari D, Liu T, Coda A, et al. Real-world matching performance of deidentified record-linking tokens. Appl Clin Inform. 2022;13:865–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers RP, Shaheen AA, Fong A, Wan AF, Swain MG, Hilsden RJ, et al. Validation of coding algorithms for the identification of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis using administrative data. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:175–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernan MA, Alonso A, Logan R, Grodstein F, Michels KB, Willett WC, et al. Observational studies analyzed like randomized experiments: An application to postmenopausal hormone therapy and coronary heart disease. Epidemiology. 2008;19:766–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brookhart MA. Counterpoint: The treatment decision design. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182:840–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toh S, Hernan MA. Causal inference from longitudinal studies with baseline randomization. Int J Biostat. 2008;4:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwards JE, LaCerte C, Peyret T, Gosselin NH, Marier JF, Hofmann AF, et al. Modeling and experimental studies of obeticholic acid exposure and the impact of cirrhosis stage. Clin Transl Sci. 2016;9:328–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato T, Matsuyama Y. Marginal structural models as a tool for standardization. Epidemiology. 2003;14:680–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davison A, Hinkley D. Further ideas. In: Gill R, Ripley BD, eds. Bootstrap Methods and Their Application. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 1997:70–135. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. 1st ed. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanagawa T. Case-control studies: Assessing the effect of a confounding factor. Biometrika. 1984;71:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lash TL. Bias analysis. In: Lash TL, Van der Weele TJ, Haneuse S, Rothman KJ, eds. Modern Epidemiology, 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2021:711–754. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lash TL, Fox MP, MacLehose RF, Maldonado G, McCandless LC, Greenland S. Good practices for quantitative bias analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1969–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS Clinical Trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56:779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones DE, Beuers U, Bonder A, Carbone M, Culver E, Dyson J, et al. Primary biliary cholangitis drug evaluation and regulatory approval: Where do we go from here? Hepatology. 2024;80:1291–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franklin JM, Patorno E, Desai RJ, Glynn RJ, Martin D, Quinto K, et al. Emulating randomized clinical trials with nonrandomized real-world evidence studies: First results From the RCT DUPLICATE initiative. Circulation. 2021;143:1002–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chodankar D. Introduction to real-world evidence studies. Perspect Clin Res. 2021;12:171–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu M, Li J, Haller IV, Romanelli RJ, VanWormer JJ, Rodriguez CV, et al. Factors associated with prevalence and treatment of primary biliary cholangitis in United States health systems. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1333–1341 e1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]