Abstract

Background

The existence and transmission of pathogenic and antibiotic-resistant bacteria through currency banknotes and coins poses a global public health risk. Banknotes and coins are handled by people in everyday life and have been identified as a universal medium for potentially microbial contamination.

Methods

To ascertain existence of medically important bacteria, a total of 300 samples including 150 banknotes and 150 coins were randomly collected at onsite retail fresh meat stores, i.e., pork and chicken, fish, and seafood stores, from nineteen fresh markets distributed across Bangkok, Thailand. An individual banknote or coin was entirely swabbed, and bacterial culture was carried out using tryptic soy agar (TSA), sheep blood agar (SBA) and MacConkey agar (Mac). A colony count was performed and bacterial species identification was conducted using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometry. Phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing was carried out using the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion methods.

Results

The results demonstrated that the bacterial contamination rate was higher on banknotes than on coins (93.33% vs. 30.00%) in all three store types. A substantial number of colonies of >3,000 colony forming units (CFU) was predominantly found in banknotes (70.00%), especially from fish store (83.3%); meanwhile, <1,000 CFU was observed in coin sample (76.67%). MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry could identify 107 bacterial species, most of them were Staphylococcus kloosii (14.02%, 15/107), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (12.15%, 13/107), and Macrococcus caseolyticus (8.41%, 9/107). The prevalence based on genera were Staphylococcus (36.45%, 39/107), Acinetobacter (20.56%, 22/107), and Macrococcus (10.28%, 11/107). Almost all Staphylococcus isolates had low susceptibility to penicillin (21%). Notably, Staphylococcus arlettae, Staphylococcus haemolyticus and M. caseolyticus were multidrug-resistant (MDR). It is notable that none of the staphylococci and macrococci isolates exhibited inducible clindamycin resistance (D-test negative). Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas putida isolates were carbapenem-resistant, and Acinetobacter baumannii isolates were MDR with showing carbapenem resistance.

Conclusion

Our data demonstrated a high prevalence of medically important bacteria presented on Thai currency, which may pose a potential risk to human health and food safety. Food vendors and consumers should be educated about the possible cross-contamination of bacteria between the environment, food item, and currency.

Keywords: Bacteria, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, Currency, Markets, Antimicrobial susceptibility test, Thai

Introduction

Cashless payment technology is a feature that currency transactions in the digital world provide for individuals; nevertheless, this advanced technology is still unable to apply to all users or be implemented in all places. Consequently, transactions utilizing banknotes and coins remain significant and unavoidable. Accumulated data reported over the last 20 years globally on the microbial status and survival of pathogen on currency notes indicated that this could represent a potential cause of disease transmission, especially respiratory and gastrointestinal infections (Schaarschmidt, 1884; Agersew, 2014; Ofoedu et al., 2021). The frequent handling of money by individuals with bacteria-contaminated hands, as well as its contact with contaminated surfaces or food, poses a significant risk. Money, as a universal medium of exchange, has the potential to act as a carrier for the transmission of infectious pathogens to humans and animals. Additionally, it may facilitate the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes between commensal and pathogenic bacteria, as documented in prior studies (Nemeghaire et al., 2014; Chanchaithong, Perreten & Schwendener, 2019).

Previous reports indicated that banknotes and coins were frequently contaminated with bacteria, particularly from human skin microbiota such as coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), gut microbiota enterococci, and environmental Bacillus spp. (Ofoedu et al., 2021; Meister et al., 2023). Additionally, various other pathogenic bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Streptococcus spp., Escherichia coli (E. coli), Proteus spp., Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Pseudomonas spp., Acinetobacter spp., Salmonella spp., and multiple-drug resistance bacteria, are frequently identified (Meister et al., 2023). Certain bacteria have been documented to flourish on the skin (Mackintosh & Hoffman, 1984), and on inanimate surfaces for a long time (Kramer, Schwebke & Kampf, 2006). Nonetheless, several parameters such as humidity, temperature, pH, salinity, surface material, UV radiation, the presence of organic matter, and ventilation, along with pathogen-specific factors like the initial quantity of infectious agents, can significantly influence the persistence of infectious microbes (Leung, 2021).

Thailand is located in a tropical region with high temperatures and humidity, which effectively encourages the growth of germs. Thailand is experiencing rapid aging, positioning itself as the second most aged society in ASEAN, following Singapore. At present, twenty percent of the Thai population is aged 60 years or older. By 2030, approximately one-third of the Thai population is projected to be over 60 years old (UNFPA Country Office in Thailand, 2021). These factors might raise the risk of bacterial colonization, transmission, and infection in elderly individuals who are susceptible. Consequently, it is imperative to prioritize the evaluation of bacterial contamination on currency to reduce public health hazards, particularly for vulnerable populations that lack access to advanced cashless technologies. Unfortunately, research is scarce on this significant field in Thailand. This study aimed to identify bacterial strains contaminating Thai currency using the MALDI-TOF assay and to determine the antimicrobial resistance profiles of the medically important bacteria detected. This has the potential to offer important information regarding public health surveillance, which could encourage individuals to be aware of and maintain their hygiene.

Materials and Methods

Study sites and sample collection

This cross-sectional study was conducted from June to July 2024, which any kinds of Thai banknotes and coins were randomly collected from retail fresh meat stores at the markets in Bangkok, Thailand. Excellent fresh food markets certified by the Department of Internal Trade (DIT), Ministry of Commerce, Thailand, located in Bangkok were selected as the study sites.

Based on previous investigations, many studies from several countries including Thailand have reported the very high prevalence of bacterial contamination ranging from 69% to 100% of tested currencies with varying degrees of sample sizes randomly collected (70–343 banknotes and coins) (Phunpae et al., 2018; Ofoedu et al., 2021; Yar, 2020; Ejaz, Javeed & Zubair, 2018; Gabriel, Coffey & O’Mahony, 2013; Alemu, 2014). In addition, most of the tested currencies were contaminated by pathogenic or potentially pathogenic bacteria. Therefore, we hypothesized that most of actively used banknotes and coins in the circulation system might be contaminated by bacteria. Our study set the sample sizes with at least 35 samples based on each type of fresh stores (pork and chicken, seafood, and fish stores) located in nineteen markets, identified as excellent fresh food markets, across Bangkok. Therefore, a presumptive sample sizes of 105 banknotes and 105 coins should be collected. However, to precise statistically descriptive analysis, our study collected a total of 300 samples, including 150 banknotes and 150 coins, with a similar proportion from each store type as described in Table 1. The samples were collected by the purchasing process from three categories of retail stores: pork and chicken stores, fish stores, and seafood stores. The samples received from each store were kept in a sterile plastic bag under cold storage condition before further processing.

Table 1. Details of markets and data distribution in sample collection.

| Market details a | Pork/Chicken | Seafood | Fish | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label | District | B | C | B | C | B | C | B | C |

| (I) Phra Nakhon Zone | |||||||||

| A | Sai Mai | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 9 |

| B | Bang Sue | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 9 |

| C | Bang Khen | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 8 |

| D | Bang Khen | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | – | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| E | Khan Na Yao | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 8 |

| F | Min Buri | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 9 |

| G | Lak Si | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 12 |

| H | Chatuchak | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | – | – | 5 | 4 |

| I | Suan Luang | 3 | 3 | 3 | – | 2 | – | 8 | 3 |

| J | Prawet | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 6 |

| K | Din Daeng | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 12 | 10 |

| L | Pathum Wan | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | – | – | 8 | 8 |

| (II) Thonburi Zone | |||||||||

| M | Bangkok Noi | 4 | 3 | 4 | – | 1 | – | 9 | 3 |

| N | Khlong San | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | – | 8 | 8 |

| O | Taling Chan | 6 | 7 | 5 | 5 | – | – | 11 | 12 |

| P | Suan Luang | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | – | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| Q | Thung Khru | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 10 |

| R | Thawi Watthana | 1 | 3 | 3 | – | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| S | Thawi Watthana | 3 | – | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 6 |

| Total | 59 | 59 | 61 | 54 | 30 | 37 | 150 | 150 | |

Notes.

Samples were collected from each market once, except for market O, which was sampled twice.

Abbreviations

- B

- banknote

- C

- coin

Sample processing

Each banknote or coin was entirely swabbed, and the swab was then resuspended with 1 ml of tryptic soy broth (TSB) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C (Phunpae et al., 2018). One-hundred microliters (µl) TSB culture was directly inoculated to tryptic soy agar (TSA) without making a dilution for colony count, and a full loop of culture was utilized to isolate the bacterial colonies in the sample using a cross-streak technique on sheep blood agar (SBA) and MacConkey agar (Mac). All culture plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C. The leftover TSB culture was kept at 4 °C. A colony count on TSA was reported as CFU/ml or too many to count (TMTC). The positive culture on SBA/Mac was recorded and calculated as the prevalence percentage (%). The suspected medically important bacterial colonies were chosen for subculturing as pure isolation on SBA/Mac, and the basic characteristics was determined by gram-staining to differentiate between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and by testing the presumptive tests of catalase/oxidase (Lee, 2021).

Colony identification using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

A fresh pure colony was spotted on a MALDI-TOF target Microflex (Bruker Daltonik, Wissembourg, France) using a sterile wooden toothpick. An expanded direct transfer (“on-target” extraction) method was used for the gram-positive colony. The spotted colony as a film was treated with one µl of 70% formic acid (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in HPLC grade water (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and left to air dry at room temperature. Following the drying, 1–2 µl of a saturated solution of α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA) matrix solution in 50% acetonitrile and 2.5% trifluoroacetic acid was applied and allowed to dry at room temperature for 5 min before loading sample targets into the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) instrument for analysis. On the other hand, a direct transfer method was applied for the gram-negative colony. The same protocol was done as described for the gram-positive colony except for not treating with formic acid solution (Calderaro & Chezzi, 2024).

Sample mass spectra were acquired and analyzed by the Biotyper software to compare the protein profile of the bacteria with a library database (Calderaro & Chezzi, 2024). An analyzed score <1.70 was considered unreliable and no identification of bacteria, while a score ≥1.70 was accepted for identification. A score >1.99 represents a precise identification of genus and species, whereas a score ≥1.70−1.99 confirms identification of genus only, without species specification (Calderaro & Chezzi, 2024; Czeszewska-Rosiak et al., 2025).

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

An antimicrobial susceptibility assay was performed using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method. Inhibition zones were measured and interpreted using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (33rd edition) (Institute CLSI, 2023). The following antibiotics (Oxoid) were used: penicillin 10 µg (P), ampicillin 10 µg (AMP), ampicillin/clavulanic acid 20/10 µg (AMC), amikacin 30 µg (AK), clindamycin two µg (DA), erythromycin 15 µg (E), cefoxitin 30 µg (FOX), sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim 23.75/1.25 µg (SXT), tetracyclin 30 µg (TE), fusidic acid 10 µg (FD), gentamicin 10 µg (CN), gentamicin 120 µg (CN), vancomycin 30 µg (VA), ceftazidime 30 µg (CAZ), cefotaxime 30 µg (CTX), meropenem 10 µg (MEM), imipenem 10 µg (IMP), ciprofloxacin five µg (CIP), and levofloxacin five µg (LEV). The clinical resistance breakpoints established for Staphylococcus spp. were applied to Macrococcus spp., as proposed by Cotting et al. (2017). Inducible clindamycin resistance was detected using a double disk diffusion test by CLSI guidelines. The antimicrobial susceptibility results for each group of tested microorganisms were calculated as a percentage of susceptibility (only S result) and presented as antimicrobial resistance profiles.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was carried out to calculate the frequency or percentage of data.

Biosafety approval

The biosafety issue was approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (TU-IBC), Thammasat University with the certificate of approval number 015/2567.

Results

Sample collection and bacteria identification by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

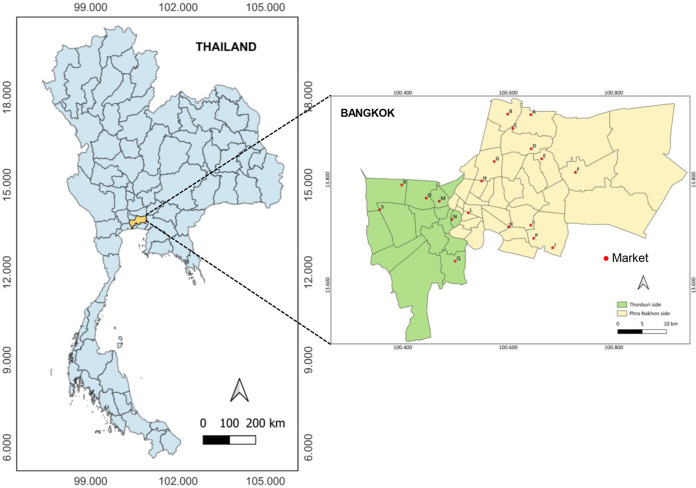

Nineteen excellent fresh food markets (labelled A-S in Fig. 1) located in different locations across two zone areas of Thonburi (green zone) and Phra Nakhon (yellow zone) of Bangkok province were chosen as study sites. A total of 300 samples, including 150 banknotes and 150 coins, were collected with a similar proportion from each store type as described in Table 1.

Figure 1. Map of the study sites encompassing nineteen excellent fresh food markets (labeled A-S) located in different locations across two zone areas of Thonburi (green zone) and PhraNakhon (yellow zone) of Bangkok, Thailand.

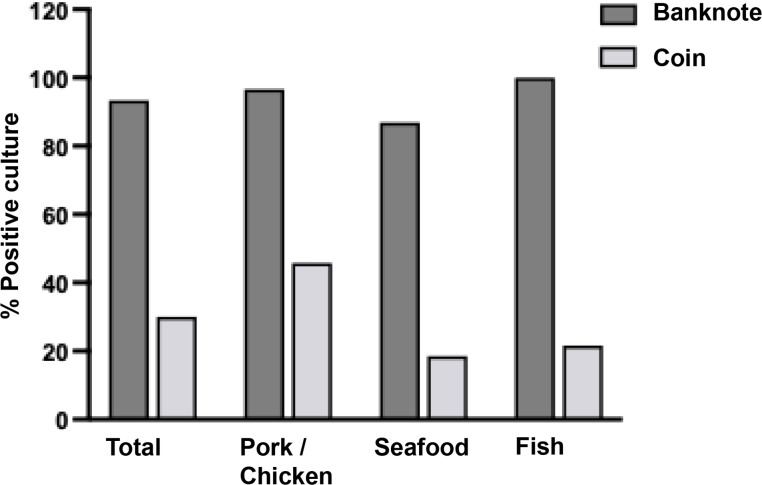

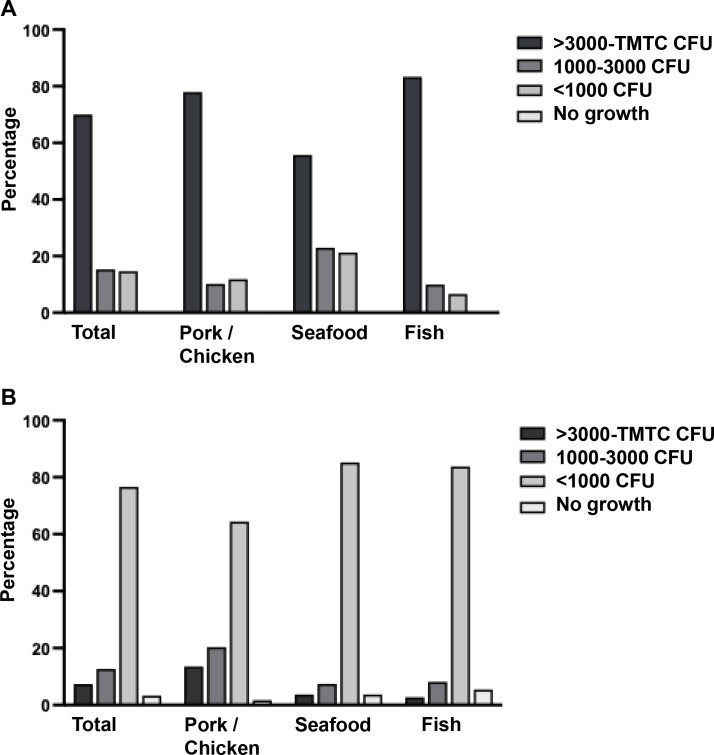

As shown in Fig. 2, the bacteria contamination rates were detected on banknotes higher than on coins (93.33% vs. 30.00%) in all store types. All positive samples were contaminated with multiple colony types. The highest bacterial contamination rate on banknotes was observed in fish stores (100%, 30/30), whereas the highest contamination rate on coins was found in pork and chicken stores (45.76%, 27/59) (Table S1). Additionally, the colony count was evaluated for banknote and coin samples as illustrated in Figs. 3A and 3B. Seventy percent of the banknote samples exhibited a substantial number of colonies, ranging from over 3,000 CFU to TMTC, whereas 76.67% of the coin samples displayed colony counts below 1000 CFU. Notably, the highest percentage of >3000-TMTC CFU colony count was observed on banknotes at fish stores (83.33%) and on coins at pork and poultry stores (13.56%) (Table S2). In addition, the number of contaminated bacteria detected across different location sites for both banknote and coin was comparable by showing minimum detection at ranged of 0–60 CFU and maximum detection of >3,000 CFU or TMTC (Table S2).

Figure 2. Percentage of bacterial detection on Thai banknotes and coins from retail fresh meat stores, i.e., pork and chicken, fish, and seafood stores.

Figure 3. Enumeration of bacterial colonies grown in tryptic soy agar (TSA).

A colony count was evaluated and reported as CFU/ml or too many to count (TMTC) for banknotes (A) and coins (B).

One-hundred and twenty-five colonies grown on SBA/Mac were randomly selected from any kind and any source of samples. They were isolated and identified using the MALDI-TOF MS, and the analyzed score of each isolate was reported in Table S3. About 85.60% (107/125) of isolates could be reported due to some of them showing the problems of no peak signal presence or unidentified peptide peak based on the database. Colony isolation from fish stores could be identified in the highest proportion (90.91%, 20/22) when compared to pork and chicken stores (89.66%, 52/58), and seafood stores (77.78%, 35/45). Data from MALDI-TOF MS indicated that the majority were uncommon bacterial strains identified as shown in Table 2. Of the detected strains, 58.69% (27/46) were gram-negative. The top three predominant strains were Staphylococcus kloosii (14.02%, 15/107), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (12.15%, 13/107), and Macrococcus caseolyticus (8.41%, 9/107). Staphylococcus kloosii and Macrococcus caseolyticus were the most prevalence in pork and chicken stores; meanwhile, S. saprophyticus was mostly detected in seafood stores. Nevertheless, the prevalence data analyzed based on genus, Staphylococcus (36.45%, 39/107), Acinetobacter (20.56%, 22/107), and Macrococcus (10.28%, 11/107) were identified as the three most predominant genera.

Table 2. Description of bacteria identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, sources of isolation, and infection system.

| Microorganisms | Gram | No. of isolation | Total (%) (N = 107) |

Infection systems | Reference | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pork/Chicken (N = 52) |

Seafood (N = 35) |

Fish (N = 20) |

RT | SST | UT | CNS | BL | GI | Others | No report | ||||

| Acinetobacter baumannii | GNC/GNCB | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 (2.80) | x | x | x | x | x | Howard et al. (2012), Towner (2009) | |||

| Acinetobacter bereziniae | GNCB/GNB | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 (3.74) | x | Dahal, Paul & Gupta (2023) | |||||||

| Acinetobacter defluvii | GNCB/GNB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | – | |||||||

| Acinetobacter gandensis | GNCB/GNB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | – | |||||||

| Acinetobacter indicus | GNCB/GNB | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.93) | x | Dahal, Paul & Gupta (2023) | |||||||

| Acinetobacter junii | GNCB/GNB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | Abo-Zed, Yassin & Phan (2020) | |||||||

| Acinetobacter lactucae | GNCB/GNB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | Sheck et al. (2023) | |||||||

| Acinetobacter pittii | GNCB/GNB | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | Bello-López et al. (2024) | |||||

| Acinetobacter radioresistens | GNCB/GNB | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.93) | x | Wang et al. (2019) | |||||||

| Acinetobacter seifertii | GNCB/GNB | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | Sheck et al. (2023) | |||||||

| Acinetobacter ursingii | GNCB/GNB | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 (5.61) | x | Dahal, Paul & Gupta (2023) | |||||||

| Acinetobacter variabilis | GNCB/GNB | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | – | |||||||

| Aerococcus viridans | GPC | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 (2.80) | x | x | x | Mohan et al. (2017) | |||||

| Aeromonas veronii | GNB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | x | x | Janda & Abbott (2010) | |||

| Bacillus pumilus | GPB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | Tena et al. (2007), Bentur, Dalzell & Riordan (2007) | ||||||

| Corynebacterium casei | GPB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | Bernard (2012) | |||||||

| Cronobacter sp. | GNB | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | x | Patrick et al. (2014) | ||||

| Delftia tsuruhatensis | GNB | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.87) | x | Ranc et al. (2018) | |||||||

| Empedobacter falsenii | GNB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | Olowo-Okere et al. (2022) | ||||||

| Enterobacter kobei | GNB | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | x | Hoffmann et al. (2005), Ji et al. (2021) | ||||

| Enterobacter roggenkampii | GNB | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | Ji et al. (2021) | |||||

| Enterococcus casseliflavus | GPC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.93) | x | Yoshino (2023) | |||||||

| Escherichia coli | GNB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | x | Mueller & Tainter (2023) | ||||

| Lysinibacillus fusiformis | GPB | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | Sulaiman et al. (2018) | |||||

| Macrococcus canis | GPC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (1.87) | x | Jost et al. (2021) | |||||||

| Macrococcus caseolyticus | GPC | 7 | 1 | 1 | 9 (8.41) | x | Zhang et al. (2022) | |||||||

| Mammaliicoccus sciuri † | GPC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (1.87) | x | x | x | Boonchuay et al. (2023), Dakić et al. (2005) | |||||

| Mixta calida | GNB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | Huzefa et al. (2022) | ||||||

| Moraxella osloensis | GNCB | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (1.87) | x | x | x | Alkhatib et al. (2017) | |||||

| Ochrombactrum amthropi | GNB | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.93) | x | Jeyaraman et al. (2022) | |||||||

| Pantoea eucrina | GNB | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | – | |||||||

| Pantoea piersonii | GNB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | – | |||||||

| Pluralibacter gergoviae | GNB | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (1.87) | x | x | x | Furlan & Stehling (2023) | |||||

| Priestia megaterium | GPB | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | Shwed et al. (2021), Bocchi et al. (2020) | |||||

| Pseudomonas putida | GNB | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (1.87) | x | x | x | Baykal et al. (2022) | |||||

| Rothia amarae | GPC | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (1.87) | x | Fatahi-Bafghi (2021) | |||||||

| Rothia endophytica | GPC | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (1.87) | x | Fatahi-Bafghi (2021) | |||||||

| Staphylococcus arlettae | GPC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | Dinakaran et al. (2012) | ||||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | GPC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | x | x | Tong et al. (2015) | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | GPC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.80) | x | Otto (2009) | |||||||

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | GPC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.93) | x | x | x | Eltwisy et al. (2022) | |||||

| Staphylococcus hominis | GPC | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 (2.80) | x | x | Vasconcellos et al. (2022) | ||||||

| Staphylococcus kloosii | GPC | 12 | 3 | 0 | 15 (14.02) | x | x | Blondeau et al. (2021) | ||||||

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | GPC | 3 | 7 | 3 | 13 (12.15) | x | x | Lawal et al. (2021) | ||||||

| Staphylococcus xylosus | GPC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (1.87) | x | Dordet-Frisoni et al. (2007) | |||||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | GNB | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.80) | x | x | x | x | x | Brooke (2012) | |||

Notes.

It was previously known as Staphylococcus sciuri.

Abbreviations

- N

- number of isolates

- RT

- respiratory tract

- SST

- skin and soft tissues or wound

- UT

- urinary tract

- CNS

- central nervous system

- BL

- blood

- GI

- gastrointestinal tract

- GNC

- gram-negative cocci

- GNCB

- gram-negative coccobacilli

- GNB

- gram-negative bacilli

- GPC

- gram-positive cocci

- GPB

- gram-positive bacilli

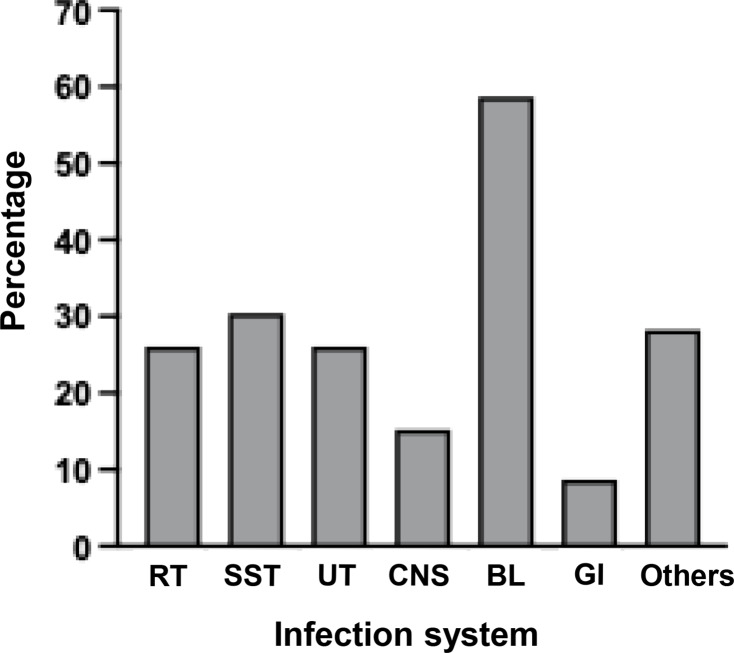

Considering the majority of uncommon bacterial strains were detected, their category as human pathogens and their pathogenesis was examined, as illustrated in Table 2. The literature review identified eight classifications of infection systems for each microorganism: respiratory tract (RT), skin and soft tissues (SST) or wound, urinary tract (UT), central nervous system (CNS), blood (BL), gastrointestinal tract (GI), other systems, and no report. Among them, the majority of detected bacteria (78.26%, 36/46) were classified as human pathogens, with a significant proportion (69.44%, 25/36) responsible for multiple tract infections. Nonetheless, bloodstream infection was the most prevalent (Fig. 4 and Table S4).

Figure 4. Percentages of detected bacteria classified as human pathogens for causing infections in several systems.

Antimicrobial susceptibility

As shown in Table 3, fifty bacterial isolates were randomly selected from groups of bacteria that can be tested by standard antimicrobial drugs, which have interpretation criteria based on CLSI guidelines. Almost all Staphylococcus isolates had low susceptibility to penicillin (21%), with the exception of S. epidermidis, which demonstrated no resistance for all drugs tested. Isolates of S. arlettae and S. haemolyticus were multidrug-resistant (MDR), defined as the bacterial isolate acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories (Magiorakos et al., 2012), and methicillin-resistant. Macrococci, a close relative of the Staphylococcus genus, were highly resistant to erythromycin and clindamycin. M. caseolyticus exhibited intermediate susceptibility to fusidic acid and low susceptibility to tetracyclin. Thus, some M. caseolyticus isolates were multidrug resistance. It is notable that none of the staphylococci and macrococci isolates exhibited inducible clindamycin resistance (D-test negative). A single isolate of Enterococcus was susceptible to all drugs that were tested.

Table 3. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of identified gram positive bacteria (A) and gram negative bacteria (B) in the study.

| Microorganisms (N) | % Drug Susceptibility a | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | DA | E | FOX | SXT | TE | FD | AMC | VA | h-CN | LEV | AMP | CAZ | CTX | CN | IMP | MEM | AK | CIP | |

| (A) Gram positive bacteria | |||||||||||||||||||

| Staphylococcus (19) | 21 | 74* | 89* | 95 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| S. kloosii (4) | 0 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| S. hominis (3) | 33 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| S. xylosus (2) | 0 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| S. saprophyticus (5) | 20 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| S. epidermidis (2) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| S. arlettae (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| S. haemolyticus (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus (1) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| Macrococcus (6) | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 67* | 83* | ||||||||||||

| M. canis (2) | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| M. caseolyticus (4) | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 75* | ||||||||||||

| Enterococcus casseliflavus (1) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||||||||||||||

| (B) Gram negative bacteria | |||||||||||||||||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (1) | 100 | 100 | |||||||||||||||||

| Enterobacter roggenkampii (1) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Enterobacter kobei (1) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Escherichia coli (1) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | |||||||||||

| Pseudomonas putida (2) | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| Acinetobacter (16) | 50 | 100 | 88* | 94 | 88* | ||||||||||||||

| A. baumannii (2) | 0 | 100 | 0 | 50 | 50 | ||||||||||||||

| A. bereziniae (3) | 67* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| A. defluvii (1) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| A. gandensis (1) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| A. indicus (1) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| A. junii (1) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| A. pittii (1) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| A. radioresistens (1) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| A. seifertii (1) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| A. ursingii (3) | 33 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

| A. variabilis (1) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

Notes.

The data was calculated from only susceptible result. Level of drug susceptibility was classified into three levels: Low susceptibility (≤ 50%) was indicated in bold number; Intermediate susceptibility (51–89%) was indicated with asterisk sign (*); and High susceptibility (≥ 90%).

Abbreviations

- N

- number of isolates

- P

- penicillin 10 μ g

- AMP

- ampicillin 10 μ g

- AMC

- ampicillin/clavulanic acid 20/10 μ g

- AK

- amikacin 30 μ g

- DA

- clindamycin 2 μ g

- E

- erythromycin 15 μ g

- FOX

- cefoxitin 30 μ g

- SXT

- sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim 23.75/1.25 μ g

- TE

- Tetracyclin 30 μ g

- FD

- Fusidic acid 10 μ g

- CN

- gentamicin 10 μ g

- h-CN

- gentamicin 120 μ g

- VA

- vancomycin 30 μ g

- CAZ

- ceftazidime 30 μ g

- CTX

- cefotaxime 30 μ g

- MEM

- meropenem 10 μ g

- IMP

- imipenem 10 μ g

- CIP

- ciprofloxacin 5 μ g

- LEV

- levofloxacin 5 μ g

For gram-negative bacteria, most of them were resistant to ampicillin, ampicillin/clavulanic acid, and ceftazidime. Notably, E. coli and P. putida isolates were carbapenem-resistant, and A. baumannii isolates were MDR and carbapenem-resistant. Ceftazidime resistance was observed in particular Acinetobacter non-baumannii species, such as A. bereziniae, A. defluvii, A. gandensis, A. seifertii, and A. ursingii. Ciprofloxacin resistance was also discovered in A. gandensis (Table 3 and Table S5).

Discussion

Despite the digital world enabling cashless transactions, the utilization of currency remains essential for some individuals, locations, and circumstances. A significant quantity of germs has been found on banknotes, some of which are infectious to humans (Phunpae et al., 2018; Gosa, 2015). The currency circulation could be a vehicle for transmitting pathogenic bacteria to other compromised or healthy individuals. Neglecting personal hygiene and allowing hand contact or physical transfer between bacteria-shedding sources and currency results in cash contamination. Sources of bacterial contamination in this study may occur via the release of infectious bacteria through mucus, feces, and aerosol droplets during coughing or sneezing by infected individuals, or from other contaminated environmental surfaces or fresh meats in each store. Paper notes from meat shops were likely to be contaminated with blood, which is a good medium for facilitating substantial microbial proliferation (Yar, 2020). Contaminated banknotes and coins act as a universal carrier for the spread of pathogens, posing a threat to public health.

Our finding aligned with prior studies (Phunpae et al., 2018; Kalita et al., 2013; Glenn et al., 2015) indicating that the positive culture results from banknotes were observed at a higher rate and quantity compared to coins. It is noteworthy that several bacterial strains were identified in the majority of positive culture samples, as indicated by previous research (Basavarajappa, Rao & Suresh, 2005). The difference in material type and size between Thai banknotes and Thai coins corroborated the findings. Nearly all Thai banknotes are composed of cotton-linen paper; however, the 20-baht banknote was changed to polymer material in 2009 to enhance durability for practical use. In contrast, Thai coins are composed of various metals based on their denomination, including copper, nickel, and aluminum (Bank of Thailand, 2024). The predominant metal in all Thai coins is copper, comprising between 75% and 92% (Phunpae et al., 2018). The porous structure of cotton-linen fibers in banknotes could promote bacterial colonization more effectively than polymers and metals (Vriesekoop et al., 2016). This may be attributed to a variety of physicochemical parameters in polymers (Prasai, Yami & Joshi, 2010) copper metal exhibits broad antibacterial properties that can suppress bacterial growth (Salah, Parkin & Allan, 2021).

Using the advanced MALDI-TOF MS technology to identify colonies grown on SBA/Mac agar facilitated this study to discover uncommon bacteria and newly emerging opportunistic pathogens that traditional biochemical assays, mostly utilized in prior research, could not identify. Our study identified a total of 107 bacterial isolates covering 46 species in 24 genera. Most isolates were identified as medically important and opportunistic pathogens, and the variation of bacterial species presented in currencies is comparable to previous studies (Phunpae et al., 2018; Ofoedu et al., 2021; Yar, 2020; Ejaz, Javeed & Zubair, 2018; Gabriel, Coffey & O’Mahony, 2013; Alemu, 2014). Despite the rarity of these uncommon bacteria infecting immunocompromised hosts, our comprehensively reviewed demonstrated that opportunistic and nosocomial infections have been recently documented.

Genus Staphylococcus was the most contaminated bacteria on cash samples that this study could identify. The eight species included one coagulase-positive S. aureus and seven coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), with a distinction in frequency. Staphylococci are common skin and mucous membrane colonizers in humans, poultry, and other warm-blooded animals (Lee & Yang, 2021). Despite coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) being less prevalent in human pathogenesis compared to S. aureus, its potential to cause infections in humans and animals under appropriate conditions has drawn greater scientific interest over the past decade (Von Eiff, Peters & Heilmann, 2002). Numerous species of coagulase-negative staphylococci, including S. gallinarum, S. arlettae, S. chromogenes, S. xylosus, and S. epidermidis, have been frequently isolated from the nares and skin of chickens. Our investigation was able to identify S. arlettae, S. xylosus, and S. epidermidis from pork and chicken stores. Recent studies have demonstrated that CoNS can also produce staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) and could be a potential cause of food poisoning. Numerous virulence genes linked to pathogenesis, such as ica, nuc, and ssp, which are typically present in the genomes of pathogenic staphylococci, are also identified in specific CoNS, including S. haemolyticus, S. saprophyticus, and S. arlettae (Shimizu et al., 1992; Lavecchia et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the potential role of CoNS in the transmission of antimicrobial resistance by serving as a reservoir for antimicrobial resistance genes has been increasingly documented (Nemeghaire et al., 2014; Archer & Niemeyer, 1994). Staphylococci that were nearly entirely isolated, with the exception of S. epidermidis, demonstrated a high level of penicillin resistance. From the late 1960s to the present, over 80% of staphylococcal isolates acquired in both community and hospital settings were resistant to penicillin, a resistance that was mediated by the blaZ gene, which encodes β-lactamase/penicillinase (Lowy, 2003). Only S. haemolyticus exhibited a methicillin-resistant (MR) strain, while S. haemolyticus and S. arlettae were multidrug-resistant strains (resistant to three or more antibiotic classes). This study was in line with the previous study, which could isolate MDR-S. heamolyticus from ready-to-eat (RTE) foods served in bars and restaurants (Chajecka-Wierzchowska et al., 2023). Despite the legal prohibitions, antimicrobial agents are still in use for prophylaxis or metaphylaxis in aquaculture and livestock production (Collignon & McEwen, 2019; Pepi & Focardi, 2021). In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the number of reports on the occurrence of antibiotic-resistant CoNS in food (Aslantaş & Yıldırım, 2021; Silva et al., 2022). This strongly implies that the food chain production may represent a pathway for the transmission of antimicrobial resistance genes. Antimicrobial resistance genes in staphylococci are typically located on plasmids, transposons, or other mobile genetic elements (MGEs), facilitating horizontal gene transfer (El-Adawy et al., 2022).

Acinetobacter was the second most prevalent bacterium on currency samples; twelve species of A. baumannii and eleven Acinetobacter non-baumannii (Anb) were detected. Anb species are becoming more significant as opportunistic nosocomial pathogens for humans (Sheck et al., 2023; Wong et al., 2017). The identified strains of A. lactucae (formerly referred to as A. dijkshoorniae), A. pittii, and A. seifertii belong to the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii (Acb) complex (Sheck et al., 2023). While the phenotypes of the species within the Acb complex are nearly identical, they exhibit substantial differences in terms of their ecology, pathogenesis, epidemiology, and susceptibility to antibiotics (Nemec et al., 2011). Moreover, the isolated isolates of A. bereziniae, A. junii, and A. ursingii have been frequently reported in human infections (Sheck et al., 2023).

The presence of extensive antibiotic resistance phenotype in A. baumannii isolated from cash samples in this study, as well as from commercial food samples in prior research (Al Atrouni, 2016; Lupo, Haenni & Madec, 2018), indicated that environmental sources may contribute to the transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to humans. A. baumannii exhibited intrinsic resistance to numerous antibiotics and possessed a notable capacity to acquire resistance to all existing therapeutic agents, including carbapenems. This has established it among the ESKAPE pathogens (E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.) (Boucher et al., 2009) and contributed to the critical position on the WHO’s global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (Breijyeh, Jubeh & Karaman, 2020). Nonetheless, most of the isolated Anb demonstrated susceptibility to the majority of the tested antibiotics, with the exception of certain species that exhibited resistance to ceftazidime. This aligns with earlier research that identified ceftazidime resistance in Anb isolates at a rate of 12.6% (Kittinger et al., 2017). Moreover, nearly all other gram-negative bacteria exhibited resistance to penicillins and third-generation cephalosporins. Resistance of Enterobacteriaceae to third-generation cephalosporins exceeds 10%, whereas resistance to carbapenems ranges from 2% to 7%. This is a result of the rapid dissemination of strains that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) (Baba et al., 2009).

Macrococcus was another type of isolate that was prevalent in this investigation. The genus Macrococcus is closely related to the genus Staphylococcus (Baba et al., 2009; Mazhar et al., 2019). It demonstrated significant homology in phenotypic and biological traits, sharing characteristics with these oxidase-positive and novobiocin-resistant staphylococci (Mašlaňová et al., 2018). Members of Macrococcus are currently classified into twelve species (Mašlaňová et al., 2018), which are commonly isolated from animal skin (ponies, horses, cows, llamas, and dogs), as well as from dairy or meat products (Kloos et al., 1998; Mannerová et al., 2003; Gobeli Brawand et al., 2017). Despite the almost all macrococci have yet to be documented in human clinical specimens, recent studies indicated high mortality rates in animals infected with Macrococci (Cotting et al., 2017; Gobeli Brawand et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018), suggesting a potential risk for human infections. Macrococcus caseolyticus and M. canis were two isolated species in the present study. M. caseolyticus was the most prevalent species that was previously classified as Staphylococcus caseolyticus due to the high degree of similarity (Cotting et al., 2017). Recently, M. canis was described for the first time as isolated from a human skin infection (Jost et al., 2021).

It is crucial to note that the adaptive acquisition of methicillin resistance genes in Macrococci genomes, such as mecABCD has been observed over the past decades (Jost et al., 2021; Schwendener, Cotting & Perreten, 2017; Gómez-Sanz et al., 2015). In contrast to classical mecA and mecC, which are predominantly associated with S. aureus, the methicillin-resistant genes found in Macrococci are primarily associated with mecB and mecD (Zhang et al., 2022; Tsubakishita et al., 2010). The mecB and mecD genes, being homologs of mecA, raise significant safety concerns because of the potential for these mobile elements to transfer to other commensal or pathogenic bacteria, such as S. aureus (Chanchaithong, Perreten & Schwendener, 2019; Gómez-Sanz et al., 2015). Despite the fact that this investigation was unable to identify methicillin-resistant Macrococcus spp. in Thai currency samples, the isolation of a potential multidrug-resistant strain may have been the result of the acquisition of MDR mobile genetic elements (Zhang et al., 2022).

Conclusions

Despite the advanced features of E-commerce technology, the use of currency as a universal medium for daily transactions remains indispensable. This study demonstrated that Thai currency, particularly Thai banknotes, was significantly contaminated with numerous highly pathogenic and newly emerging opportunistic microorganisms. It is crucial to note that the majority of these bacteria were resistant to antibiotic therapeutic medications, which raises concerns about the public health risks associated with the potential transmission of pathogens through contaminated cash. Furthermore, certain bacteria have significant drug-resistant genes within their genome, posing a risk of transferring these mobile genetic elements to other commensal or pathogenic bacteria. Consequently, our study indicates that increased focus is necessary on the surveillance and monitoring of bacterial contamination on currency, while also promoting the use of digital wallets to reduce exposure to contaminated materials, alongside enhancing education on maintaining proper personal hygiene practices.

Supplemental Information

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) Fundamental Fund, fiscal year 2024. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Nattamon Niyomdecha conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Suwitchaya Sungvaraporn performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Arisa Pinmuang performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Narissara Mungkornkaew performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Thanchira Saita performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Waratchaya Rodraksa performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Achiraya Phanitmas performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Nattapong Yamasamit performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Pirom Noisumdaeng conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, project administration and Funding acquisition, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are available in the Supplementary Files.

References

- Abo-Zed, Yassin & Phan (2020).Abo-Zed A, Yassin M, Phan T. Acinetobacter junii as a rare pathogen of urinary tract infection. Urology Case Reports. 2020;32:101209. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2020.101209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agersew (2014).Agersew A. Microbial contamination of currency notes and coins in circulation: a potential public health hazard. Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2014;2(3):46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Al Atrouni et al. (2016).Al Atrouni A, Joly-Guillou ML, Hamze M, Kempf M. Reservoirs of non-baumannii Acinetobacter species. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2016;7:49. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemu (2014).Alemu A. Microbial contamination of currency notes and coins in circulation: a potential public health hazard. Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2014;2:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhatib et al. (2017).Alkhatib NJ, Younis MH, Alobaidi AS, Shaath NM. An unusual osteomyelitis caused by Moraxella osloensis: a case report. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2017;41:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer & Niemeyer (1994).Archer GL, Niemeyer DM. Origin and evolution of DNA associated with resistance to methicillin in staphylococci. Trends in Microbiology. 1994;2(10):343–347. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90608-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslantaş & Yıldırım (2021).Aslantaş Ö, Yıldırım N. Isolation of methicillin resistant (MR) Staphylococci from chicken meat samples. Harran University Journal of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. 2021;10(2):126–131. doi: 10.31196/huvfd.958632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baba et al. (2009).Baba T, Kuwahara-Arai K, Uchiyama I, Takeuchi F, Ito T, Hiramatsu K. Complete genome sequence of Macrococcus caseolyticus strain JCSCS5402, (corrected) reflecting the ancestral genome of the human-pathogenic staphylococci. Journal of Bacteriology. 2009;191(4):1180–1190. doi: 10.1128/JB.01058-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Thailand (2024).Bank of Thailand About BoT. 2024. https://www.bot.or.th/en/about-us.html. [14 October 2024]. https://www.bot.or.th/en/about-us.html

- Basavarajappa, Rao & Suresh (2005).Basavarajappa KG, Rao PN, Suresh K. Study of bacterial, fungal, and parasitic contamination of currency notes in circulation. Indian Journal of Pathology & Microbiology. 2005;48:278–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baykal et al. (2022).Baykal H, Çelik D, Ülger AF, Vezir S, Güngör MÖ. Clinical features, risk factors, and antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas putida isolates. Medicine. 2022;101(48):e32145. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000032145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello-López et al. (2024).Bello-López E, Escobedo-Muñoz AS, Guerrero G, Cruz-Córdova A, Garza-González E, Hernández-Castro R, Zarain PL, Morfín-Otero R, Volkow P, Xicohtencatl-Cortes J, Cevallos MA. Acinetobacter pittii: the emergence of a hospital-acquired pathogen analyzed from the genomic perspective. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2024;15:1412775. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1412775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentur, Dalzell & Riordan (2007).Bentur HN, Dalzell AM, Riordan FA. Central venous catheter infection with Bacillus pumilus in an immunocompetent child: a case report. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2007;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard (2012).Bernard K. The genus corynebacterium and other medically relevant coryneform-like bacteria. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2012;50(10):3152–3158. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00796-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau et al. (2021).Blondeau LD, Rubin JE, Deneer H, Kanthan, Sanche S, Blondeau JM. Isolation of Staphylococcus kloosii from an ankle wound of an elderly female patient in rural Saskatchewan, Canada: a case report. Annals of Clinical Case Reports. 2021;6(1):2073. [Google Scholar]

- Bocchi et al. (2020).Bocchi MB, Cianni L, Perna A, Vitiello R, Greco T, Maccauro G, Perisano C. A rare case of Bacillus megater ium soft tissues infection. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91(14-S):e2020013. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i14-S.10849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonchuay et al. (2023).Boonchuay K, Sontigun N, Wongtawan T, Fungwithaya P. Association of multilocus sequencing types and antimicrobial resistance profiles of methicillin-resistant Mammaliicoccus sciuri in animals in Southern Thailand. Veterinary World. 2023;16(2):291–295. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2023.291-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher et al. (2009).Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(1):1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breijyeh, Jubeh & Karaman (2020).Breijyeh Z, Jubeh B, Karaman R. Resistance of gram-negative bacteria to current antibacterial agents and approaches to resolve it. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2020;25(6):1340. doi: 10.3390/molecules25061340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke (2012).Brooke JS. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: an emerging global opportunistic pathogen. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2012;25(1):2–41. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00019-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderaro & Chezzi (2024).Calderaro A, Chezzi C. MALDI-TOF MS: a reliable tool in the real life of the clinical microbiology laboratory. Microorganisms. 2024;12(2):322. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12020322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chajęcka-Wierzchowska et al. (2023).Chajęcka-Wierzchowska W, Gajewska J, Zadernowska A, Randazzo CL, Caggia C. A comprehensive study on antibiotic resistance among coagulase-negative Staphylococci (CoNS) Strains isolated from ready-to-eat food served in bars and restaurants. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2023;12(3):514. doi: 10.3390/foods12030514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanchaithong, Perreten & Schwendener (2019).Chanchaithong P, Perreten V, Schwendener S. Macrococcus canis contains recombinogenic methicillin resistance elements and the mecB plasmid found in Staphylococcus aureus. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2019;74(9):2531–2536. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon & McEwen (2019).Collignon PJ, McEwen SA. One health-its importance in helping to better control antimicrobial resistance. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2019;4(1):22. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotting et al. (2017).Cotting K, Strauss C, Rodriguez-Campos S, Rostaher A, Fischer NM, Roosje PJ, Favrot C, Perreten V. Macrococcus canis and M. caseolyticus in dogs: occurrence, genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance. Veterinary Dermatology. 2017;28(6):559–e133. doi: 10.1111/vde.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeszewska-Rosiak et al. (2025).Czeszewska-Rosiak G, Adamczyk I, Ludwiczak A, Fijałkowski P, Fijałkowski P, Twaruzek M, Złoch M, Gabryś D, Miśta W, Tretyn A, Pomastowski PP. Analysis of the efficacy of MALDI-TOF MS technology in identifying microorganisms in cancer patients and oncology hospital environment. Heliyon. 2025;11(2):e42015. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahal, Paul & Gupta (2023).Dahal U, Paul K, Gupta S. The multifaceted genus Acinetobacter: from infection to bioremediation. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2023;134(8):lxad145. doi: 10.1093/jambio/lxad145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakić et al. (2005).Dakić I, Morrison D, Vuković D, Savić B, Shittu A, Jezek P, Hauschild T, Stepanović S. Isolation and molecular characterization of Staphylococcus sciuri in the hospital environment. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(6):2782–2785. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2782-2785.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinakaran et al. (2012).Dinakaran V, Shankar M, Jayashree S, Rathinavel A, Gunasekaran P, Rajendhran J. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus arlettae strain CVD059, isolated from the blood of a cardiovascular disease patient. Journal of Bacteriology. 2012;194(23):6615–6616. doi: 10.1128/JB.01732-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dordet-Frisoni et al. (2007).Dordet-Frisoni E, Dorchies G, De Araujo C, Talon R, Leroy S. Genomic diversity in Staphylococcus xylosus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2007;73(22):7199–7209. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01629-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejaz, Javeed & Zubair (2018).Ejaz H, Javeed A, Zubair M. Bacterial contamination of Pakistani currency notes from hospital and community sources. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2018;34:1225–1230. doi: 10.12669/pjms.345.15477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Adawy et al. (2016).El-Adawy H, Ahmed M, Hotzel H, Monecke S, Schulz J, Hartung J, Ehricht R, Neubauer H, Hafez HM. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from healthy turkeys and broilers using DNA microarrays. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2016;7:2019. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltwisy et al. (2022).Eltwisy HO, Twisy HO, Hafez MH, Sayed IM, El-Mokhtar MA. Clinical infections, antibiotic resistance, and pathogenesis of Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Microorganisms. 2022;10(6):1130. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10061130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatahi-Bafghi (2021).Fatahi-Bafghi M. Characterization of the Rothia spp. and their role in human clinical infections. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2021;93:104877. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan & Stehling (2023).Furlan JPR, Stehling EG. Genomic insights into Pluralibacter gergoviae sheds light on emergence of a multidrug-resistant species circulating between clinical and environmental settings. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland) 2023;12(11):1335. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12111335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, Coffey & O’Mahony (2013).Gabriel EM, Coffey A, O’Mahony JM. Investigation into the prevalence, persistence and antibiotic resistance profiles of staphylococci isolated from euro currency. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2013;115:565–571. doi: 10.1111/jam.12247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn et al. (2015).Glenn LSS, Christelle C, Audrey C, Regalado J, Anna V, Mary AS, Teresita DG. Bacteriological and parasitological assessment of currencies obtained in selected markets of Metro Manila. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 2015;5:468–470. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(15)60817-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobeli Brawand et al. (2017).Gobeli Brawand S, Cotting K, Gómez-Sanz E, Collaud A, Thomann A, Brodard I, Rodriguez-Campos S, Strauss C, Perreten V. Macrococcus canis sp. nov. a skin bacterium associated with infections in dogs. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2017;67(3):621–626. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Sanz et al. (2015).Gómez-Sanz E, Schwendener S, Thomann A, Gobeli Brawand S, Perreten V. First Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec containing a mecB-carrying gene complex independent of transposon Tn6045 in a Macrococcus canis isolate from a canine infection. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2015;59(8):4577–4583. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05064-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosa (2015).Gosa G. Health risk associated with handling of paper currencies. International Journal of Food and Nutritional Science. 2015;2:1–6. doi: 10.15436/2377-0619.15.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann et al. (2005).Hoffmann H, Schmoldt S, Trülzsch K, Stumpf A, Bengsch S, Blankenstein T, Heesemann J, Roggenkamp A. Nosocomial urosepsis caused by Enterobacter kobei with aberrant phenotype. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2005;53(2):143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard et al. (2012).Howard A, O’Donoghue M, Feeney A, Sleator RD. Acinetobacter baumannii: an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Virulence. 2012;3(3):243–250. doi: 10.4161/viru.19700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huzefa et al. (2022).Huzefa B, Vinayak M, Nakeya D, Josue V-G, Samiullah A, Subramanya SG, Adnan B, Gaurang V. Indolent course of mixta calida bacteremia mimicking decompensated heart failure. Chest. 2022;162:A160–A161. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.08.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute CLSI (2023).Institute CLSI . Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 33rd edition. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne: 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Janda & Abbott (2010).Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2010;23(1):35–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaraman et al. (2022).Jeyaraman M, Muthu S, Sarangan P, Jeyaraman N, Packkyarathinam RP. Ochrobactrum anthropi—an emerging opportunistic pathogen in musculoskeletal disorders—a case report and review of literature. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports. 2022;12(3):85–90. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2022.v12.i03.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji et al. (2021).Ji Y, Wang P, Xu T, Zhou Y, Chen R, Zhu H, Zhou K. Development of a one-step multiplex PCR assay for differential detection of four species (Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter hormaechei, Enterobacter roggenkampii, and Enterobacter kobei) belonging to Enterobacter cloacae complex with clinical significance. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2021;11:677089. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.677089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost et al. (2021).Jost G, Schwendener S, Liassine N, Perreten V. Methicillin-resistant Macrococcus canis in a human wound. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2021;96:105125. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.105125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalita et al. (2013).Kalita M, Palusińska-Szysz M, Turska-Szewczuk A, Wdowiak-Wróbel S, Urbanik-Sypniewska T. Isolation of cultivable microorganisms from Polish notes and coins. Polish Journal of Microbiology. 2013;62(3):281–286. doi: 10.33073/pjm-2013-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittinger et al. (2017).Kittinger C, Kirschner A, Lipp M, Baumert R, Mascher F, Farnleitner AH, Zarfel GE. Antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter spp. isolates from the river Danube: susceptibility stays high. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;15(1):52. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15010052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloos et al. (1998).Kloos WE, Ballard DN, George CG, Webster JA, Hubner RJ, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, Fiedler F, Schubert K. Delimiting the genus Staphylococcus through description of Macrococcus caseolyticus gen. nov., comb. nov. and Macrococcus equipercicus sp. nov., and Macrococcus bovicus sp. no. and Macrococcus carouselicus sp. nov. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1998;48(Pt 3):859–877. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-3-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Schwebke & Kampf (2006).Kramer A, Schwebke I, Kampf G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces? A systematic review. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006;6:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavecchia et al. (2019).Lavecchia A, Chiara M, De Virgilio C, Manzari C, Monno R, De Carlo A, Pazzani C, Horner D, Pesole G, Placido A. Staphylococcus arlettae genomics: novel insights on candidate antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Microorganisms. 2019;7(11):580. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7110580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawal et al. (2021).Lawal OU, Barata M, Fraqueza MJ, Worning P, Bartels MD, Goncalves L, Paixão P, Goncalves E, Toscano C, Empel J, Urbaś M, Domiìnguez MA, Westh H, De Lencastre H, Miragaia M. Staphylococcus saprophyticus from clinical and environmental origins have distinct biofilm composition. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2021;12:663768. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.663768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee (2021).Lee A. LibreText™https://bio.libretexts.org/Courses/North_Carolina_State_University/MB352_General_Microbiology_Laboratory_2021_(Lee)/07%3A_Microbial_Metabolism/7.02%3A_Introduction_to_Biochemical_Tests_Part_II#: :text=Oxidase%20positive%20bacteria%20change%20the,reagent%20from%20colorless%20to%20black. [18 March 2024];MB352 general microbiology laboratory. 2021

- Lee & Yang (2021).Lee GY, Yang SJ. Profiles of coagulase-positive and -negative staphylococci in retail pork: prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, enterotoxigenicity, and virulence factors. Animal Bioscience. 2021;34(4):734–742. doi: 10.5713/ajas.20.0660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung (2021).Leung NHL. Transmissibility and transmission of respiratory viruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2021;19(8):528–545. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00535-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2018).Li G, Du X, Zhou D, Li C, Huang L, Zheng Q, Cheng Z. Emergence of pathogenic and multiple-antibiotic-resistant Macrococcus caseolyticus in commercial broiler chickens. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 2018;65(6):1605–1614. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy (2003).Lowy FD. Antimicrobial resistance: the example of Staphylococcus aureus. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111(9):1265–1273. doi: 10.1172/JCI18535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo, Haenni & Madec (2018).Lupo A, Haenni M, Madec JY. Antimicrobial resistance in Acinetobacter spp. and Pseudomonas spp. Microbiology Spectrum. 2018;6(3):ARBA-0007-2017. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0007-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh & Hoffman (1984).Mackintosh CA, Hoffman PN. An extended model for transfer of micro-organisms via the hands: differences between organisms and the effect of alcohol disinfection. The Journal of Hygiene. 1984;92(3):345–355. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400064561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos et al. (2012).Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannerová et al. (2003).Mannerová S, Pantůček R, Doškař J, Švec P, Snauwaert C, Vancanneyt M, Swings J, Sedláček I. Macrococcus brunensis sp. nov., Macrococcus hajekii sp. nov. and Macrococcus lamae sp. nov., from the skin of llamas. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2003;53(Pt 5):1647–1654. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mašlaňová et al. (2018).Mašlaňová I, Wertheimer Z, Sedláček I, Švec P, Indráková A, Kovařovic V, Schumann P, Spröer C, Králová S, Šedo O, Krištofová L, Vrbovská V, Füzik T, Petráš P, Zdráhal Z, Ružičková V, Doškař J, Pantuček R. Description and comparative Ggenomics of Macrococcus caseolyticus subsp. hominis subsp. nov., Macrococcus goetzii sp. nov., Macrococcus epidermidis sp. nov., and Macrococcus bohemicus sp. nov., Novel Macrococci from human clinical material with virulence potential and suspected uptake of foreign DNA by natural transformation. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018;9:1178. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazhar et al. (2019).Mazhar S, Altermann E, Hill C, McAuliffe O. Draft genome sequences of the type strains of six Macrococcus species. Microbiology Resource Announcements. 2019;8(19):e00344–19. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00344-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister et al. (2023).Meister TL, Kirchhoff L, Brüggemann Y, Todt D, Steinmann J, Steinmann E. Stability of pathogens on banknotes and coins: a narrative review. Journal of Medical Virology. 2023;95(12):e29312. doi: 10.1002/jmv.29312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan et al. (2017).Mohan B, Zaman K, Anand N, Taneja N. Aerococcus viridans: a rare pathogen causing urinary tract infection. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2017;11(1):DR01–DR03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/23997.9229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller & Tainter (2023).Mueller M, Tainter CR. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2023. [2024 Jan]. Escherichia coli infection. [Updated 2023 Jul 13] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemec et al. (2011).Nemec A, Krizova L, Maixnerova M, Van der Reijden TJ, Deschaght P, Passet V, Vaneechoutte M, Brisse S, Dijkshoorn L. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex with the proposal of Acinetobacter pittii sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 3) and Acinetobacter nosocomialis sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU) Research in Microbiology. 2011;162(4):393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeghaire et al. (2014).Nemeghaire S, Argudín MA, Feßler AT, Hauschild T, Schwarz S, Butaye P. The ecological importance of the Staphylococcus sciuri species group as a reservoir for resistance and virulence genes. Veterinary Microbiology. 2014;171(3–4):342–356. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofoedu et al. (2021).Ofoedu CE, Iwouno JO, Agunwah IM, Obodoechi PZ, Okpala COR, Korzeniowska M. Bacterial contamination of Nigerian currency notes: a comparative analysis of different denominations recovered from local food vendors. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10795. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olowo-Okere et al. (2022).Olowo-Okere A, Ibrahim YKE, Olayinka BO, Mohammed Y, Nabti LZ, Lupande-Mwenebitu D, Rolain JM, Diene SM. Genomic features of an isolate of Empedobacter falsenii harbouring a novel variant of metallo-β-lactamase, blaEBR-4 gene. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2022;98:105234. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2022.105234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto (2009).Otto M. Staphylococcus epidermidis-the ‘accidental’ pathogen. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2009;7(8):555–567. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick et al. (2014).Patrick ME, Mahon BE, Greene SA, Rounds J, Cronquist A, Wymore K, Booth E, Lathrop S, Palmer A, Bowen A. Incidence of Cronobacter spp. infections, United States, 2003–2009. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2014;20(9):1520–1523. doi: 10.3201/eid2009.140545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepi & Focardi (2021).Pepi M, Focardi S. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in aquaculture and climate change: a challenge for health in the mediterranean area. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(11):5723. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phunpae et al. (2018).Phunpae P, Sriruan C, Udpuan R, Buamongkol S, Pawichai S, Ruangpayuk A, Chairungwut W. Bacterial contamination and their tolerance in banknotes and coins surrounding the area of Chiang Mai University Hospital in Chiang Mai Province. Journal of Associated Medical Sciences. 2018;51(3):171–179. doi: 10.14456/jams.2018.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasai, Yami & Joshi (2010).Prasai T, Yami KD, Joshi DR. Microbial load on paper/polymer currency and coins. Nepal Journal of Science and Technology. 2010;9:105–109. doi: 10.3126/njst.v9i0.3173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranc et al. (2018).Ranc A, Dubourg G, Fournier PE, Raoult D, Fenollar F. Delftia tsuruhatensis, an emergent opportunistic healthcare-associated pathogen. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2018;24(3):594–596. doi: 10.3201/eid2403.160939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salah, Parkin & Allan (2021).Salah I, Parkin IP, Allan E. Copper as an antimicrobial agent: recent advances. RSC Advances. 2021;11(30):18179–18186. doi: 10.1039/d1ra02149d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaarschmidt (1884).Schaarschmidt J. Upon the occurrence of bacteria and minute algæon the surface of paper money. Nature. 1884;30:360. doi: 10.1038/030360a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendener, Cotting & Perreten (2017).Schwendener S, Cotting K, Perreten V. Novel methicillin resistance gene mecD in clinical Macrococcus caseolyticus strains from bovine and canine sources. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:43797. doi: 10.1038/srep43797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheck et al. (2023).Sheck E, Romanov A, Shapovalova V, Shaidullina E, Martinovich A, Ivanchik N, Mikotina A, Skleenova E, Oloviannikov V, Azizov I, Vityazeva V, Lavrinenko A, Kozlov R, Edelstein M. Acinetobacter non-baumannii species: occurrence in infections in hospitalized patients, identification, and antibiotic Resistance. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 2023;12(8):1301. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12081301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu et al. (1992).Shimizu A, Ozaki J, Kawano J, Saitoh Y, Kimura S. Distribution of Staphylococcus species on animal skin. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 1992;54(2):355–357. doi: 10.1292/jvms.54.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shwed et al. (2021).Shwed PS, Crosthwait J, Weedmark K, Hoover E, Dussault F. Complete genome sequences of Priestia megaterium type and clinical strains feature complex plasmid arrays. Microbiology Resource Announcements. 2021;10(27):e0040321. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00403-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva et al. (2022).Silva V, Caniça M, Ferreira E, Vieira-Pinto M, Saraiva C, Pereira JE, Capelo JL, Igrejas G, Poeta P. Multidrug-resistant methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci in healthy poultry slaughtered for human consumption. Antibiotics. 2022;11(3):365. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11030365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman et al. (2018).Sulaiman IM, Hsieh YH, Jacobs E, Miranda N, Simpson S, Kerdahi K. Identification of Lysinibacillus fusiformis isolated from cosmetic samples using MALDI-TOF MS and 16S rRNA sequencing methods. Journal of AOAC International. 2018;101(6):1757–1762. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.18-0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tena et al. (2007).Tena D, Martinez-Torres JA, Perez-Pomata MT, Sáez-Nieto JA, Rubio V, Bisquert J. Cutaneous infection due to Bacillus pumilus: report of 3 cases. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44(4):e40–e42. doi: 10.1086/511077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong et al. (2015).Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler Jr VG. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2015;28(3):603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towner (2009).Towner KJ. Acinetobacter: an old friend, but a new enemy. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2009;73(4):355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubakishita et al. (2010).Tsubakishita S, Kuwahara-Arai K, Baba T, Hiramatsu K. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec-like element in Macrococcus caseolyticus. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2010;54(4):1469–1475. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00575-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA Country Office in Thailand (2021).UNFPA Country Office in Thailand Comprehensive policy framework a life-cycle approach to ageing in Thailand. 2021. https://thailand.un.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/framework_on_ageing.pdf https://thailand.un.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/framework_on_ageing.pdf

- Vasconcellos et al. (2022).Vasconcellos D, Weng B, Wu P, Thompson G, Sutjita M. Staphylococcus hominis infective endocarditis presenting with embolic splenic and renal infarcts and spinal discitis. Case Reports in Infectious Diseases. 2022;2022:7183049. doi: 10.1155/2022/7183049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Eiff, Peters & Heilmann (2002).Von Eiff C, Peters G, Heilmann C. Pathogenesis of infections due to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2002;2(11):677–685. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriesekoop et al. (2016).Vriesekoop F, Chen J, Oldaker J, Besnard F, Smith R, Leversha W, Smith-Arnold C, Worrall J, Rufray E, Yuan Q, Liang H, Scannell A, Russell C. Dirty money: a matter of bacterial survival, adherence, and toxicity. Microorganisms. 2016;4(4):42. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms4040042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2019).Wang T, Costa V, Jenkins SG, Hartman BJ, Westblade LF. Acinetobacter radioresistens infection with bacteremia and pneumonia. IDCases. 2019;15:e00495. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong et al. (2017).Wong D, Nielsen TB, Bonomo RA, Pantapalangkoor P, Luna B, Spellberg B. Clinical and pathophysiological overview of Acinetobacter infections: a century of challenges. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2017;30(1):409–447. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yar (2020).Yar DD. Bacterial contaminants and antibiogram of Ghana paper currency notes in circulation and their associated health risks in asante-mampong, Ghana. International Journal of Microbiology. 2020;2020:8833757. doi: 10.1155/2020/8833757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino (2023).Yoshino Y. Enterococcus casseliflavus infection: a review of clinical features and treatment. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2023;16:363–368. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S398739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2022).Zhang Y, Min S, Sun Y, Ye J, Zhou Z, Li H. Characteristics of population structure, antimicrobial resistance, virulence factors, and morphology of methicillin-resistant Macrococcus caseolyticus in global clades. BMC Microbiology. 2022;22(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12866-022-02679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are available in the Supplementary Files.