Abstract

Background

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are traumatic experiences (e.g., abuse) that can have a profound negative effect on a child’s developing brain and body with lasting deleterious impacts on a person’s mental health and chronic disease risk throughout the lifespan. Exposure to ACEs is often repeated generation to generation. STANCE (Supporting Trauma Awareness and Nurturing Children’s Environments) was developed, in partnership with a rural community in Colorado, to prevent the intergenerational transmission of ACEs. STANCE is employing community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles to develop and test a multi-level community intervention to promote socioemotional development in young children, enhance parenting skills, and strengthen a comprehensive system of care to meet the needs of young families who have experienced ACEs.

Methods

An effectiveness-implementation hybrid study of STANCE is being conducted in the San Luis Valley of Colorado, a rural community with a majority Hispanic population. The primary effectiveness outcomes are being evaluated in a pragmatic public health trial using a stepped-wedge cluster randomized design that includes 16 early childhood education centers. A mixed-methods, prospective case study with a social network analysis approach will inform the primary implementation outcomes which were drawn from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).

Discussion

This study evaluates the effectiveness and implementation of an ACEs prevention intervention for young children and families living in a rural community. If successful, this trial will inform the use of evidence-based intervention strategies to address ACEs and provide a framework for dissemination and implementation to other rural communities.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13063-025-08881-z.

Keyword: Community-based participatory research, Adverse childhood experiences, Social-emotional development, Early childhood

Background

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are traumatic experiences that can have a profound negative effect on a child’s developing brain and body with lasting deleterious impacts on a person’s mental health and chronic disease risk throughout the lifespan. There are ten recognized ACEs, which fall into three types—abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. The CDC-Kaiser Permanente ACE Study [1] found that ACEs are common (63.9% of adults in the study had experienced at least one ACE), highly inter-related, and exert a powerful negative effect on human development, behaviors, and chronic disease outcomes. Moreover, a person with four or more ACEs, compared to those who had experienced no ACEs, had increased health risks for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempt and was more likely to suffer from numerous chronic health conditions (e.g., obesity, ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease) [1]. ACEs have also been linked to over 40 adverse outcomes, including low life potential (e.g., academic achievement), negative health behaviors, disease outcomes, and even premature death [2] and there is some research that suggests there is an even more detrimental impact of ACEs on health for people of color [3]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has estimated that the economic toll associated with child maltreatment is between $124 and $585 billion across the lifetime [4]. The wide-ranging health and social consequences and long-term costs, both human and economic, of ACEs underscore the necessity of primary prevention.

ACEs in early childhood

ACEs experienced during critical periods of development, such as early childhood (birth to age eight), can have especially detrimental impacts. The basic architecture of the brain is constructed through an ongoing process that begins before birth, is heightened in early childhood, and continues into adulthood. Early experiences affect the quality of brain architecture by establishing either a sturdy or a fragile foundation for subsequent learning, health, and behavior. In the first few years of life, more than 1 million new neural connections are formed every second [5]. Stressors experienced during this critical period of development shape a child’s physiological response to stress, which then becomes biologically embedded and can lead to the development of disease [6]. Therefore, early exposure to ACEs negatively impacts brain development processes and can lead to poorer cognitive, social, regulatory, and emotional trajectories [7].

Children who have at least one ACE are more likely to be emotionally reactive to stress and less capable of emotional regulation [8]. Lack of emotional regulation in childhood is associated with the onset of depression, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, substance-abuse disorders, and eating disorders through adolescence and into adulthood [9]. As the number of ACEs experienced increases, the level of social-emotional distress in children increases [10]. Because early childhood development can be severely compromised by exposure to ACEs, addressing ACEs and promoting positive social-emotional development early in life can mitigate risk and bolster protective factors, which can lead to more positive adaptive outcomes, including significant improvements in health and well-being [7].

The intergenerational transmission of ACEs

The association between exposure to ACEs early in life and poor mental health outcomes in adulthood can lead to next generation exposure to the same kind of abuse, neglect, and familial dysfunction and, thus, the intergenerational transmission of ACEs [11, 12]. Hypothesized mechanisms for the intergenerational transmission of ACEs include parental psycho-social vulnerability, maladaptive coping behaviors [13], and non-nurturing interactions between parent and child [14, 15]. For example, Plant et al. found that mothers with one or more ACEs were more likely to be depressed during pregnancy, which was associated with significantly greater levels of offspring childhood maltreatment. [15] Moreover, mothers who experience violence during childhood may model these behaviors by engaging in various forms of violence within their relationships and directed at their children. Finally, maternal experience of ACEs in early childhood impacts maternal-child attachment. Mothers who report exposure to traumatic events in childhood can exhibit attachment disorganization as parents, in which fear and disorganization predominate maternal-child interactions often leading to neglect [16].

Prevention and intervention strategies

In order to effectively address the intergenerational transmission of ACEs, prevention and intervention strategies should be aimed at both parents and young children to prevent, treat, or reduce the long-term effects of mental illness throughout the life span [17, 18]. Currently, efforts to intervene are scattered across service sectors and often do not take a prevention approach to improving mental health, but rather tend to be more reactive to individuals’ mental health challenges and crises. A two-generational, evidence-based mental health approach to addressing ACEs with a component that addresses the coordination of community services across the various sectors is needed.

The STANCE intervention overview

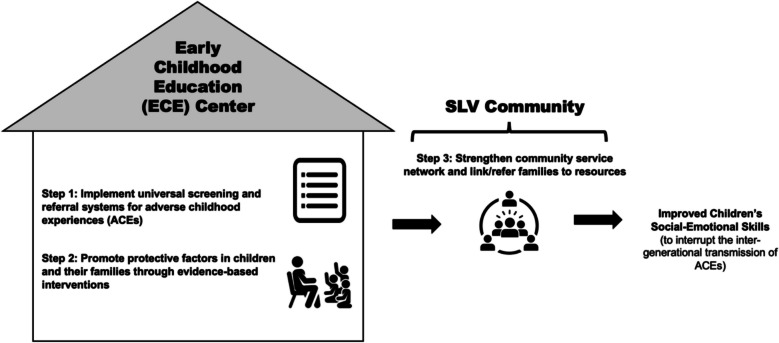

STANCE (Supporting Trauma Awareness and Nurturing Children’s Environments) is a multi-level, multi-generation, stakeholder-directed framework designed to decrease the intergenerational transmissions of ACEs. The framework was designed as part of a long-standing, community-academic partnership in the San Luis Valley (SLV) of Colorado and consists of three steps: (1) building capacity and infrastructure within early childhood education (ECE) settings to implement ECE-based assessments for early identification of ACEs and appropriate referral to extant community supports (e.g., behavioral health services); (2) implementing an evidence-based, tiered intervention that promotes social-emotional development among children, enhances resilience and reduces stress among parents and teachers, and strengthens social and physical environmental support within ECE settings; and (3) strengthening the community system of care to better meet the needs of children and families struggling with ACEs. Figure 1 includes a conceptual model of the STANCE intervention framework.

Fig. 1.

STANCE intervention framework conceptual model

The aim of this article is to describe the design of a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study to test the effectiveness and implementation of the STANCE intervention. For the effectiveness component, we hypothesize that an integrated, coordinated systems approach in ECE centers that involves timely assessment of ACEs, intervention, and referral will lead to increased social-emotional development for children (primary outcome), decreased parental stress (secondary outcome), and improved parental mental health (secondary outcome). For the implementation component, we hypothesize that there will be common and specific barriers and facilitators to participant engagement, program implementation, and sustainability at the individual, organization, and community levels. Our hybrid effectiveness-implementation study of STANCE is rigorously testing our hypotheses in a real-world, complex, community setting to inform the field on ACEs prevention and treatment strategies in the early childhood setting. It is also doing so, by adhering to community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles and, thus, incorporating community engagement throughout the entire study process [19].

Methods

Study design

The STANCE intervention began in August 2020 in the SLV of Colorado under funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Grant: 6 U48DP006399-01–01). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB) (Protocol #19–1969). Any amendments to the study protocol will be submitted to COMIRB and communicated to project study team. To evaluate the intervention, we have employed a hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation study design, which involves the blending of two study designs and has the benefits of rapid translational gains [20]. The primary effectiveness outcomes are being evaluated in a pragmatic public health trial using a stepped-wedge cluster randomized design with participating ECE centers [21, 22]. The study design is a pragmatic study design which can reconcile the need for robust evaluation with logistical constraints [23]. A mixed-methods, prospective case study with a social network analysis approach is informing the primary implementation outcomes, which were drawn from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [24]. By using a hybrid design, we can understand the implementation strategies needed for program success, demonstrate effectiveness of the linking of evidence-based programs, and increase the speed at which interventions are translated to public health practice by simultaneously assessing both effectiveness and implementation.

The primary outcome of the effectiveness study is increased social-emotional development in young children (age 3–5) achieved through improved ECE settings, teaching practices, and an improved community-level network of services. Due to our two-generational approach, secondary outcomes pertain to the primary caregivers of the young children and include lower perceived stress, increased mindful attention awareness, increased resiliency, and lower depressive and anxiety symptoms. The primary outcomes for the implementation study are intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, process, and the cost of adopting the intervention.

Community setting

The San Luis Valley is comprised of six counties (3 frontier with less than six people per square mile and 3 rural) with a total population of 46,040; 40% of residents are of Hispanic origin [25]. Approximately the size of New Jersey, the SLV is identified as a Health Professional Shortage Area and a Medically Underserved Area, two key federal designations that identify areas with severe health care provider access issues and areas in need of assistance with health care delivery. The estimated median household income is $37,663 compared to the Colorado median of $72,331 [25]. The percentage of families who live in poverty in the six counties of the SLV ranges from 7.6 to 21.2% compared to 6.6% in Colorado [25].

Recruitment

Recruitment was coordinated through a partnership with the Early Childhood Council of the SLV (ECC SLV), a hub of early childhood efforts that aims to strengthen the local system of early childhood care and education through research, advocacy, policy, and innovative practice. All ECE centers in the SLV were eligible to participate. Leaders at the Early Childhood Council connected the research team with every ECE center director in the SLV, and the research team met with each director to provide an overview of the study and answer questions. Each director was invited to participate in the study, with 16 ECE centers agreeing to participate and signing a memorandum of understanding with the principal investigators (76% participation rate). All teachers and students at these sites participated in the study. Teachers were actively consented at the beginning of the first year by the study team (and new teachers were consented at the beginning of each school year after that). Because the intervention took place at the school level, all children participated in the intervention and passive consent was obtained from parents for their children’s participation in the child assessment only. Active parent consent was obtained for parents’ participation in the intervention (see Fig. 2). It is anticipated that the final sample of children will mirror the demographics of the population in the SLV and will be 50% female and 50% male; children that have a mean age of 3.0 years; 40% Hispanic; and 60% non-Hispanic.

Fig. 2.

STANCE study schedule of enrollment, intervention, and assessments

Effectiveness study

ECE center randomization

The team statistician used SAS 9.4M7 to randomize participating ECE centers [29]. Our stepped-wedge design is included in Fig. 3and calls for three implementation steps which means that ECE centers were randomized into three cohorts. The randomization was stratified by centers’ classroom count and quality rating in order to create three relatively homogenous cohorts. Centers with 1–4 classrooms were classified as small, and centers with 5–10 classrooms were classified as large. Quality rating data was obtained from the Colorado Shines program, a quality rating and improvement system that monitors and supports early learning programs in Colorado [30]. Programs are rated on a scale of 1–5, with higher ratings demonstrating high-quality programs and practices that support children’s health and safety, ensure the staff are well-trained and effective, provide a learning environment that teaches children new skills, and help parents become partners in their child’s learning. Programs were classified as low rating (score of 1–2) or high rating (score of 3–5). In years prior to the intervention cohort year, ECE sites serve as control sites (comparators). During the intervention cohort year, the STANCE team meets with ECE center directors to confirm adherence to intervention protocols or address any necessary changes for intervention modification to meet the needs of the center. After ECE centers participate in the intervention cohort year, they move to a “Plan for Sustainability” year and then a “Sustainability” year, where the intervention team works with the center to understand which of the STANCE components the center would like to sustain, how they would like to sustain them and they action plan in order for them to be sustained.

Fig. 3.

STANCE stepped-wedged cluster randomized study design

STANCE intervention components.

The 1-year STANCE intervention was implemented to three intervention cohorts over the course of 3 years (see Figs. 2 and 3). The intervention comprises the following three detailed components:

Conduct ACEs screening and referral at ECE centers. The STANCE intervention includes conducting ACEs screenings (called the Health and Well-Being survey) among children and parents within participating ECEs using the Center for Youth Wellness (CYW) ACEs-Questionnaire (ACE-Q) [26]. The ACE-Q is a clinical screening tool that calculates cumulative exposure to ACEs. The tool contains 17 items and is completed by the parent or primary caregiver of the child. The instrument contains two sections: Sect. 1 comprises the 10 ACEs for which population-level data for disease risk in adults exists, and Sect. 2 assesses exposure to seven additional early life stressors, such as bullying and migration. Respondents are asked to report how many ACEs and early life stressors apply to them and their child. The tool is available in English and Spanish and takes approximately 2 to 5 min to complete. For families (either child or parent) who screen positive for four or more ACEs, trained early childhood behavioral health specialists with the ECC SLV, who are pre-assigned to intervention sites, provide early childhood behavioral health consultation and/or refer the family to the appropriate extant community services. The “referral” could take a variety of forms, including a traditional referral to a service agency, a “warm handoff” to the agency, or a navigator model at the ECE center. Based on feedback from community partners, benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) were also assessed. The BCEs scale assess positive early life experiences in a child’s life, such as the presence of at least one safe caregiver or the presence of at least one good friend, and was developed to be multiculturally sensitive and applicable regardless of socioeconomic position, urban–rural background, or immigration status [27].

Implement an evidence-based ECE intervention that promotes protective factors in children and their families. The STANCE intervention coaching team, comprised of two certified ECE coaches that had completed 45 training hours and been certified longer than a year, are training and coaching participating ECE teachers in the evidence-based Pyramid Model for Supporting Social-Emotional Competence in Infants and Young Children (Pyramid Model) (https://challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu/Pyramid/overview/index.html). The Pyramid Model provides a tiered intervention framework of evidence-based strategies for promoting the social, emotional, and behavioral development of infants and young children [28]. The Pyramid Model includes four levels of practices that address the needs of all children, including children with persistent, challenging behavior. These practices are arranged using a response to intervention framework. The first two levels (nurturing and responsive relationships and high-quality supportive environments) are universal approaches that are delivered to all children in a classroom by the teacher. The third level (targeted social-emotional supports) includes secondary interventions designed to address the needs of children at risk for problem behavior, and the fourth level (intensive intervention) provides an individualized intervention approach for children with the most severe and persistent challenging behavior. In addition to these efforts, STANCE is assisting participating ECE centers in coordinating and facilitating a corresponding parenting program. The program, entitled Positive Solutions for Families, was developed by the Pyramid Model and provides families with information on how to promote children’s social and emotional skills, understand their problem behavior, and use positive approaches to help children learn appropriate behavior. The STANCE coaches conduct an initial training with intervention teachers at the beginning of the intervention school year and then provide coaching on the Pyramid Model for at least 30 min each week for approximately 7 months (a total of 28 coaching sessions). Examples of coaching topics include noticing and responding to your feelings, building positive relationships, responsive environments, designing a schedule that promotes child engagement, and minimizing challenging behaviors during transition times.

Strengthen community service network of care for ACEs. To leverage and strengthen the system of care to better meet the needs of children and families struggling with ACEs and associated downstream health outcomes, the STANCE intervention is employing a social network analysis methodology. This approach will include (1) characterizing the existing ACEs services system of care by conducting a community-level social network analysis; (2) identifying barriers and discrepancies between systems-level and personal networks of care (using a personal network analysis); and (3) developing and implementing community-driven solutions to strengthen the ACEs system of care.

Primary outcomes and instruments.

The primary outcome of interest for this study is children’s social-emotional development (increased social skills and decreased problem behaviors). Changes in social-emotional development in children at participating ECE centers are measured using a pre-/post-Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS) assessment. The SSIS assessment is a brief (15–20 min) teacher-report on the frequency of various behaviors exhibited by a child using a 4-point Likert scale [31, 32]. The social skills subscale has a total of 30 items assessing cooperation, assertion, self-control, communication, empathy, and engagement. The problem behavior subscale is also a 30-item subscale assessing behaviors related to externalizing, internalizing, bullying, and hyperactivity/inattention.

Sample size, power, and data analysis for primary outcomes.

Power calculations for this study’s primary effectiveness outcomes were based on the three implementation steps in the 1-year time blocks for the stepped-wedge cluster randomized design. The intervention is being implemented in random order in 5–6 sites at a time, and the continuous outcomes (social skills and problem behavior measures at the individual child level) will be analyzed using linear mixed-models, including a time effect and teachers as a random effect. Due to budget constraints, data will not be collected on intervention sites following the time block in which the intervention was implemented, which is a limitation. As such, the power calculation for this study, the number of students enrolled per site per time block was reduced by 25% to account for this reduction in total sample size [33]. For the social skills outcome, the original randomized controlled trial (RCT) study data for the Pyramid Model, which also used the SSIS assessment, reported a standard deviation (SD) of 14.0 [28], and this study will therefore have 80% power to detect a difference in mean scores on the SSIS social skill subscale of 3.2. For the problem behaviors outcome, the original RCT study data reported a SD of 16.4 [28], and this study will therefore have 80% power to detect a difference in mean scores on the SSIS problem behaviors subscale of 3.8. Both differences are considerably less than the differences found in the original RCT study, and these calculations assume an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 within sites and are based on two-sided hypothesis tests at the 5% significance level.

Secondary outcomes and instruments.

Improved parenting skills.

Parenting skills, including positive reinforcement, parenting involvement, disciplinary inconsistence, friendship skills, emotional literacy, and problem-solving strategies, are measured using an adapted version of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) [34]. The original APQ consists of 42 items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). An example of an item is “You let your child know when he/she is doing a good job with something.” The APQ has had multiple adaptions [35, 36], and the most recent adaptation for preschoolers resulted in three factors—positive reinforcement, parental involvement, and disciplinary inconsistence—that have demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas = English version: 0.65, 0.67, and 0.70, respectively [35]; Spanish version: 0.72, 0.77, and 0.58, respectively [36]). This survey will be administered before and after the Positive Solutions for Families workshop series.

The following instruments were combined into a Health and Well-Being survey and administered to parents/caregivers at the beginning of the school year.

Lower perceived stress in parents.

Parents’ perceived stress are measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [37], a validated tool designed to measure “the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful.” [38] The PSS consists of 10 items measuring monthly frequency on a 5-point Likert scale of items such as “how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?” and “how often have you felt nervous or stressed?”. The internal consistency reliability of the PSS in English is 0.85 [38] and in Spanish is 0.78 [39].

Increased mindfulness in parents.

Parents’ mindfulness are measured using the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), a 5-item scale designed to assess the short-term or current expression of mindfulness [40]. Mindfulness can be defined as a receptive state of mind in which an individual simply observes what is taking place around them. The internal consistency reliability Cronbach’s alpha is English version [41] = 0.87 and Spanish version [42] = 0.89.

Increased resiliency in parents.

Parents’ resiliency is measured using the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS), which was created to assess an individual’s ability to bounce back or recover from stress [43]. The BRS is a 6-item scale that assesses agreement on a 5-point Likert scale with statements such as “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times” and “I have a hard time making it through stressful events.” The BRS internal consistency reliability Cronbach’s alpha for the English version ranges from 0.80 to 0.91 [43] and for the Spanish version is 0.83 [44].

Decreased depressive symptoms in parents.

Parents’ depressive symptoms are measured using the eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-8), which has been established as a valid diagnostic and severity measure for depressive disorders in large clinical studies [45, 46]. The PHQ-8 uses a 4-point Likert scale to assess the frequency of depressive symptoms and includes questions such as “over the last 2 weeks, how often have you had little interest or pleasure in doing things?” The PHQ-8 scale has been shown to have good internal reliability in medical populations (English version: Cronbach’s α = 0.82 [47] and Spanish version: Cronbach’s α = 0.92 [48]).

Decreased anxiety symptoms in parents.

Parents’ anxiety symptoms are measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, a brief self-report scale used to identify probable cases of GAD [49]. The GAD-7 uses a 4-point Likert scale to assess the frequency of anxiety symptoms and includes questions such as “over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge?” The GAD-7 has high internal consistency (α = 0.92 for the English version [50] and α = 0.94 for the Spanish version [51]).

Community-level improved systems-level network.

The PARTNER (Program to Analyze, Record, and Track Networks to Enhance Relationships) tool [52] is being used to measure the changes in the ACEs services systems of care. The PARTNER tool contains both a validated survey and an analysis tool (https://visiblenetworklabs.com/partner-cprm/) [52, 53]. The survey includes 19 items which examine a combination of well-known social network metrics (e.g., density and centrality) as well as additional metrics developed by the tool’s research team (e.g., trust, value, and relative connectivity). The PARTNER survey is being administered in year 1 and year 4 to a bounded list of partnering agencies that serve young children and their families in the SLV. Partnering organizations from all 6 counties in the SLV and from all sectors including education (early childhood and elementary schools), healthcare (community clinics and hospitals), non-profit organizations, and governmental agencies. Having a high response rate will be essential to ensure accuracy and representativeness of the network data.

Implementation study

Primary outcomes and conceptual framework.

Intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, process, and cost.

The evaluation of implementation outcomes is being informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [24]. The CFIR is a widely used, meta-theoretical framework that includes 39 constructs across five major domains, including intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and process. The framework has been used to evaluate implementation across a wide range of study designs and contexts and provides “a common language by which determinants of implementation can be articulated, as well as a comprehensive, standardized list of constructs to serve as a guide for researchers as they identify variables that are most salient to implementation of a particular innovation.” [54] Interviews are being conducted with ECE directors, teachers, and parents and organizational representatives from the ACEs services system of care throughout the course of the study to explore CFIR constructs related to the implementation outcomes of interest. Table 1 presents sample interview questions and the CFIR construct alignment.

Table 1.

STANCE study semi-structured interview sample questions and CFIR construct alignment

| Interviewee role | Question | CFIR domain | CFIR construct |

|---|---|---|---|

| Director/teacher | How does STANCE compare to other similar existing programs in your setting? | Intervention factor | Relative advantage |

| Parent | Please describe your relationship with your child’s ECE center? | Inner setting | Networks and communication |

| Community organization | To what extent were the needs and preferences of the individuals, including parents/caregivers and children, served by your organization considered when deciding to implement STANCE? | System-level and contextual factors | Participant needs and resources |

Data management plan

A Data Safety Monitoring Plan (DSMP) will be in place to ensure safety of all participants. The DSMP includes a Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) comprised of the following specialties: mental health, early childhood, and dissemination and implementation science. The study team is conducting yearly analysis to present to the DSMB periodically to review any adverse events, data, and procedures.

Data are being collected electronically and via paper copies when necessary. Electronic data is stored in a secured database, REDCap. Downloaded data are stored on a secured server. Paper copies are being stored in a locked cabinet after data entry. Access to all data and study records, including hard copies and computer files, are limited to authorized study personnel. A copy of the data management plan is included as an appendix.

Data that are not electronically collected are entered by the project study team into the same electronic database. Double Data Entry (DDE) protocols are followed for the SSIS instrument. To ensure the accuracy of this data entry, each data entry person needs to have an error rate less than 0.5%. The first 20 assessments entered by each data entry person are double-data entered. If the error rate for the first 20 assessments is below 0.5%, then 1 assessment is randomly selected for DDE for every batch of 50 assessments entered by each data entry person. If the error rate is greater than 0.5%, the next batch of 20 are double-data entered. This occurs until the error rate is acceptable (below 0.5%).

Data are not shared beyond study personnel in its original form to protect respondents’ confidentiality. Requests for data summaries/aggregated data used to produce peer-reviewed papers or publications or community presentations will be evaluated by the co-principals (Co-PIs) and authorship will be granted on an as-needed basis. Upon publication of trial results in academic journal articles and dissemination of findings to the community via presentations and reports, all study data will be stored through the University of Colorado’s secure long-term storage with Iron Mountain. The Co-PIs and the grant administrator will maintain the storage records. Additionally, to increase transparency and decrease unnecessary duplication of research effort, we plan to make our de-identified data and statistical code available for public use through Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) (https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/landing.jsp by 9/30/30) or similar platform, through restricted access.

Discussion

ACEs can have profound effects on a child’s developing brain and body with lasting impacts on a person’s mental health and chronic disease risk throughout the lifespan. This multi-level, community-based intervention aims to facilitate and sustain prevention efforts with the goal of reducing the intergenerational transmission of ACEs in a predominately Hispanic, rural community while simultaneously studying the effectiveness and implementation of the intervention with a rigorous methodological approach. Findings from this study have high potential to positively impact the health and well-being of children and families and inform the field of ACEs science, especially as it pertains to low-resourced and under-served populations experiencing health disparities. The study design can also be used as a template because it is not only robust (e.g., high internal and external validity), but feasible and acceptable to participating organizations to implement in challenging contexts, such as the COVID pandemic and under-resourced early childhood education settings. This could be helpful for other researchers, practitioners, or funders planning similar projects.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Data management plan.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Rocky Mountain Prevention Research Center (RMPRC) San Luis Valley (SLV) Community Advisory Board (CAB) for identifying ACEs as a health topic to focus on, as well as for their guidance on the STANCE intervention and study and for their deep knowledge of the SLV community. Additionally, the authors would like to thank the leadership and staff of the Early Childhood Council of the SLV; all of the participating early childhood education centers, as well as the children and families they serve; our STANCE study team members; and our RMPRC national advisors, all of whom have been instrumental in this project.

Community Advisory Board (CAB)

The CAB identified the public health topic of interest and provided guidance on study design and community engagement.

Protocol Version

Issue date: 27 July 2023; Protocol amendment number: 21

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this report to disclose. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sponsors had no role in determining study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Author contributions

JEP and JAL conceived of the study and are the co-principal investigators. They wrote the grant that funded this study and lead the development and implementation of the intervention and the effectiveness and implementation study. BR, BM, and DV are all co-investigators for the study. They all contributed to the conception of the study design and informed the implementation of the study. BR leads the community partnership and outreach, as well as the implementation arm of the study. BM leads the cost-effectiveness part of the study. DV leads the social network analysis part of the study. DL was instrumental in the coordination of the intervention implementation and study. SS is the lead biostatistician and has oversight of all the data tracking and management. All authors contributed to the development of this manuscript.

Funding

Data used for this study were collected under contracts with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Grant: 6 U48DP006399-01–01, Jenn A. Leiferman).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this report to disclose. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sponsors had no role in determining study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing adverse childhood experiences: leveraging the best available evidence.; 2019:40. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/preventingACES.pdf

- 3.LaBrenz CA, O’Gara JL, Panisch LS, Baiden P, Larkin H. Adverse childhood experiences and mental and physical health disparities: the moderating effect of race and implications for social work. Soc Work Health Care. 2020;59(8):588–614. 10.1080/00981389.2020.1823547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(2):156–65. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center on the Developing Child. Brain architecture. Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Published 2022. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/brain-architecture/

- 6.Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. 2012;106(1):29–39. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shonkoff JP, Phillips D. From neurons to neighborhoods: the science of early childhood development. National Academies Press; 2000. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25077268/ [PubMed]

- 8.D’Andrea W, Ford J, Stolbach B, Spinazzola J, van der Kolk BA. Understanding interpersonal trauma in children: why we need a developmentally appropriate trauma diagnosis. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(2):187–200. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berking M, Wupperman P. Emotion regulation and mental health: recent findings, current challenges, and future directions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):128–34. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blodgett C. Adopting ACEs screening and assessment in child serving systems. Washington State University; 2012. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.dcyf.wa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/Complex-Trauma-Research-ACE-Screening-and-Assessment.pdf

- 11.Lesesne CA, Kennedy C. Starting early: promoting the mental health of women and girls throughout the life span. J Womens Health. 2005;14(9):754–63. 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayan AJ, Lieberman AF, Masten AS. Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85: 101997. 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin CA, Kercher GA. The intergenerational transmission of intimate partner violence: differentiating correlates in a random community sample. J Fam Violence. 2012;27(3):187–99. 10.1007/s10896-012-9419-3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bifulco A, Moran PM, Ball C, et al. Childhood adversity, parental vulnerability and disorder: examining inter-generational transmission of risk. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43(8):1075–86. 10.1111/1469-7610.00234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plant DT, Barker ED, Waters CS, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Intergenerational transmission of maltreatment and psychopathology: the role of antenatal depression. Psychol Med. 2013;43(3):519–28. 10.1017/S0033291712001298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyons-Ruth K, Jacobvitz D. Attachment disorganization: genetic factors, parenting contexts, and developmental transformations from infancy to adulthood. In: Handbook of attachment. Theory, research, and clinical applications. Guilford Press; 2008:666–697.

- 17.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):603. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E. Methods for community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed. Jossey-Bass; 2012.

- 20.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–26. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mdege ND, Man MS, Taylor (nee Brown) CA, Torgerson DJ. Systematic review of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials shows that design is particularly used to evaluate interventions during routine implementation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(9):936–948. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Glasgow RE, Riley WT. Pragmatic measures. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(2):237–43. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, Girling AJ, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ. 2015;350(feb06 1):h391-h391. 10.1136/bmj.h391 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.San Luis Valley Development Resources Group & Council of Governments. San Luis Valley statistical profile.; 2021. https://www.slvdrg.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2021-SLV-Statistical-Profile.pdf

- 26.Center for Youth Wellness. An unhealthy dose of stress.; 2013. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1RD50llP2dimEdV3zn0eGrgtCi2TWfakH/view

- 27.Narayan AJ, Rivera LM, Bernstein RE, Harris WW, Lieberman AF. Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: a pilot study of the benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) scale. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;78:19–30. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemmeter ML, Snyder PA, Fox L, Algina J. Evaluating the implementation of the pyramid model for promoting social-emotional competence in early childhood classrooms. Top Early Child Spec Educ. 2016;36(3):133–46. 10.1177/0271121416653386. [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Institute Inc. SAS 9.4 M7 macro language: reference. 5th ed. SAS Institute Inc.; 2020.

- 30.Colorado Shines. Overview of the ratings process. Colorado Shines. Published 2023. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.coloradoshines.com/programs?p=Overview-of-the-ratings-process

- 31.Gresham F, Elliot S. Social skills improvement system. Pearson Education; 2008.

- 32.Gresham FM, Elliott SN, Cook CR, Vance MJ, Kettler R. Cross-informant agreement for ratings for social skill and problem behavior ratings: an investigation of the social skills improvement system—rating scales. Psychol Assess. 2010;22(1):157–66. 10.1037/a0018124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(2):182–91. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shelton KK, Frick PJ, Wootton J. Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. J Clin Child Psychol. 1996;25(3):317–29. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2503_8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clerkin SM, Halperin JM, Marks DJ, Policaro KL. Psychometric properties of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire-Preschool Revision. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2007;36(1):19–28. 10.1080/15374410709336565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donovick M, Rodriguez MD. An examination of self-reported parenting practices among first generation Spanish-speaking Latino families: a Spanish version of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. Graduate Student J Psychology. 2008;10:52–63. 10.52214/gsjp.v10i.10833. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385. 10.2307/2136404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yokokura AVCP, Silva AAM da, Fernandes J de KB, et al. Perceived Stress Scale: confirmatory factor analysis of the PSS14 and PSS10 versions in two samples of pregnant women from the BRISA cohort. Cad Saúde Pública. 2017;33(12). 10.1590/0102-311x00184615 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Baik SH, Fox RS, Mills SD, Roesch SC, Sadler GR, Klonoff EA, Malcarne VL. Reliability and validity of the Perceived Stress Scale-10 in Hispanic Americans with English or Spanish language preference. J Health Psychol. 2019 Apr;24(5):628–639. 10.1177/1359105316684938. Epub 2017 Jan 5. PMID: 28810432; PMCID: PMC6261792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Osman A, Lamis DA, Bagge CL, Freedenthal S, Barnes SM. The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale: further examination of dimensionality, reliability, and concurrent validity estimates. J Pers Assess. 2016;98(2):189–99. 10.1080/00223891.2015.1095761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soler J, Tejedor R, Feliu-Soler A, Pascual JC, Cebolla A, Soriano J, Alvarez E, Perez V. Psychometric proprieties of Spanish version of Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2012 Jan-Feb;40(1):19–26. Epub 2012 Jan 1. PMID: 22344492. [PubMed]

- 43.Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194–200. 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodríguez-Rey R, Alonso-Tapia J, Hernansaiz-Garrido H. Reliability and validity of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) Spanish version. Psychol Assess. 2016May;28(5):e101–10. 10.1037/pas0000191. (Epub 2015 Oct 26 PMID: 26502199). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1–3):163–73. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin C, Lee SH, Han KM, Yoon HK, Han C. Comparison of the usefulness of the PHQ-8 and PHQ-9 for screening for major depressive disorder: analysis of psychiatric outpatient data. Psychiatry Investig. 2019;16(4):300–5. 10.30773/pi.2019.02.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pressler SJ, Subramanian U, Perkins SM, et al. Measuring depressive symptoms in heart failure: validity and reliability of the Patient Health Questionnaire-8. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20(2):146–52. 10.4037/ajcc2010931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pagán-Torres OM, González-Rivera JA, Rosario-Hernández E. Psychometric analysis and factor structure of the Spanish version of the eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire in a general sample of Puerto Rican adults. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2020;42(3):401–15. 10.1177/0739986320926524(Originalworkpublished2020). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266–74. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.García-Campayo J, Zamorano E, Ruiz MA, Pardo A, Pérez-Páramo M, López-Gómez V, Freire O, Rejas J. Cultural adaptation into Spanish of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale as a screening tool. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010Jan;20(8):8. 10.1186/1477-7525-8-8.PMID:20089179;PMCID:PMC2831043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varda DM, Sprong S. Evaluating networks using PARTNER: a social network data tracking and learning tool. New Dir Eval. 2020;2020(165):67–89. 10.1002/ev.20397. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Varda DM, Chandra A, Stern SA, Lurie N. Core dimensions of connectivity in public health collaboratives. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(5):E1–7. 10.1097/01.PHH.0000333889.60517.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):72. 10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 2: Data management plan.