Abstract

During pregnancy, women experience substantial anthropometric, cardiovascular, hormonal and psychological changes that affect several organs involving the circulatory, respiratory, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, dermatological and sensory systems. The main aim of this review was to analyse the available literature on postural strategies throughout pregnancy in both static and dynamic conditions. The secondary aim was to assess and discuss the current knowledge regarding vestibular disorders during pregnancy. Pregnant women with vestibular disorders need appropriate and safe treatments to resolve or reduce symptoms without risks for mother and foetus. Our protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42024622122). A literature search was conducted screening PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases. After duplicates removal and exclusion of records due to coherence with the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 41 articles relevant to the topic were examined. Although some studies claimed no changes in postural behaviour during pregnancy, most of the available evidence seems to demonstrate significant modifications in posture and balance metrics, with multiple mechanisms. Physiological changes that occur in the mother's body during pregnancy have been considered as a possible substrate for developing vestibular disorders. Dizziness and vertigo were reported in pregnancy in small, low-quality studies. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, vestibular neuritis, Ménière disease, vestibular migraine and vestibular schwannoma have all been documented in pregnant women. To overcome reported limitations, prospective studies, preferably multicentre and involving third-level audio-vestibular centres are mandatory in order to define rational diagnostic and treatment approaches for vestibular disorders to protect the safety of the mother and foetus.

Keywords: Pregnancy, balance, postural control, vestibular disorders, vertigo

Introduction

During pregnancy, women experience substantial anthropometric, cardiovascular, hormonal and psychological changes that affect several organs. 1 These structural and functional changes involve the circulatory, respiratory, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, dermatological and sensory systems, and they are modulated by specific hormones including oestrogen, progesterone, human chorionic gonadotropin, placental lactogen and relaxin. 2

Pregnancy may undoubtedly influence the need for adaptation to maintain balance and optimise joint load distribution. 3 More specifically, balance control may involve either static or dynamic balance scenarios. Static balance is defined as the ability to maintain steadiness, keeping the body as motionless as possible on a fixed, firm, unmoving base of support.4,5 On the other hand, dynamic balance involves the continuous adjustment of posture during movement or in response to acceleration forces. 5 More precisely, dynamic balance includes both autonomous and passive mechanisms. The first refers to the capability to restore balance during self-initiated movements, while the latter implies the ability to regain balance in response to external disturbances.4–6

Some authors considered alterations in the postural control system as an adaptation to the changes that occur during pregnancy. To provide stability while standing, a pregnant woman adapts her posture by increasing lumbar lordosis and slightly tilting her body posteriorly. 7 In addition to the postural changes typical of pregnancy, it is necessary to keep in mind, however, that disorders of the balance system can also occur during pregnancy. Regarding the audio-vestibular system, several conditions, including hearing loss, tinnitus, facial nerve paralysis, otosclerosis, autophony and vertigo, may present for the first time or worsen during pregnancy. 8

The main aim of this review was to analyse the available literature on postural strategies throughout pregnancy in both static and dynamic conditions. The secondary aim was to assess and critically discuss the current knowledge regarding vestibular disorders during pregnancy. Pregnant women with vestibular disorders need appropriate and safe treatments to resolve or reduce symptoms without any risks for mother and foetus. It is mandatory to provide clinicians with information on the rational diagnostic and therapeutic approach in the context of impaired balance in pregnant women.

Methods

Protocol registration

The protocol of this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO, an international database of prospectively registered reviews in health and social care (Center for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK), in 27 December 2024 (registry number CRD42024622122).

Search strategy

A systematic literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations. 9 The electronic databases Scopus, Pubmed and Web of Science were searched from database inception to 30 December 2024. As previously done, 10 a combination of MeSH terms and keywords was used to define the following search string: ((“dizziness"[MeSH Terms] OR “disequilibrium"[tiab] OR “postural balance"[MeSH Terms] OR “vertigo"[MeSH Terms] OR “vestibular diseases"[MeSH Terms] OR “vestibulopathy"[tiab]) AND (“pregnancy"[MeSH Terms] OR “gestation"[tiab] OR “puerperium"[tiab])). This string was applied to PubMed and appropriately adapted for Scopus and Web of Science. To limit the results to relevant studies, the search was restricted to human studies and articles published in English. Additionally, free-text terms (e.g. ‘vertigo’, ‘Meniere’, ‘benign paroxysmal positional vertigo’, ‘dizziness’, ‘schwannoma’, ‘vestibular neuritis’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘puerperium’) were employed to cross-check and expand the search scope. The reference lists of all included articles were thoroughly screened to find other relevant studies. References were exported to Zotero bibliography manager (v6.0.10, Center for History and New Media, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA). After duplicates removal, three reviewers (G.B., G.P., A.G.B.) independently screened all titles and abstracts and then evaluated the full texts of the eligible articles based on the inclusion criteria. Any disagreement between the reviewers involved in the literature search was resolved through discussion with all authors to reach a consensus.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review were structured according to the PICOS framework 11 to ensure a focused and systematic selection of relevant studies, as follows:

Population (P): Studies involving balance physiology/pathophysiology and/or vestibular function in pregnant women (no restrictions were placed on age, ethnicity, or geographical location).

Intervention (I): clinical and instrumental evaluation of postural balance and/or vestibular function during pregnancy under physiological or pathological conditions.

Comparison (C): studies comparing pregnant with non-pregnant women, or comparison between different gestation epochs, when applicable.

Outcomes (O): physiological variables including static/dynamic balance and/or vestibular function.

Study Design (S): Original research articles, including cross-sectional, case-control, cohort studies, randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and prospective or retrospective series with a sample size of at least 10 participants. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded but used for reference mining to identify additional studies.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) lack of relevant data; (ii) non-original studies (i.e. reviews, recommendations, letters, editorials, or book chapters); (iii) non-English language studies.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Extracted data were collected in an electronic database including study characteristics. The quality of the studies eligible for inclusion was categorised as Poor, Fair and Good, in agreement with the National Institutes of Health quality assessment tool for Observational Cohorts and Cross-Sectional Studies (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools, accessed on 3 January 2025). Three reviewers (G.B., G.P., A.G.B.) independently evaluated the papers, and any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

The included articles were qualitatively summarized, to highlight and discuss the main findings, as well as possible limitations.

Results

Search results and quality assessment

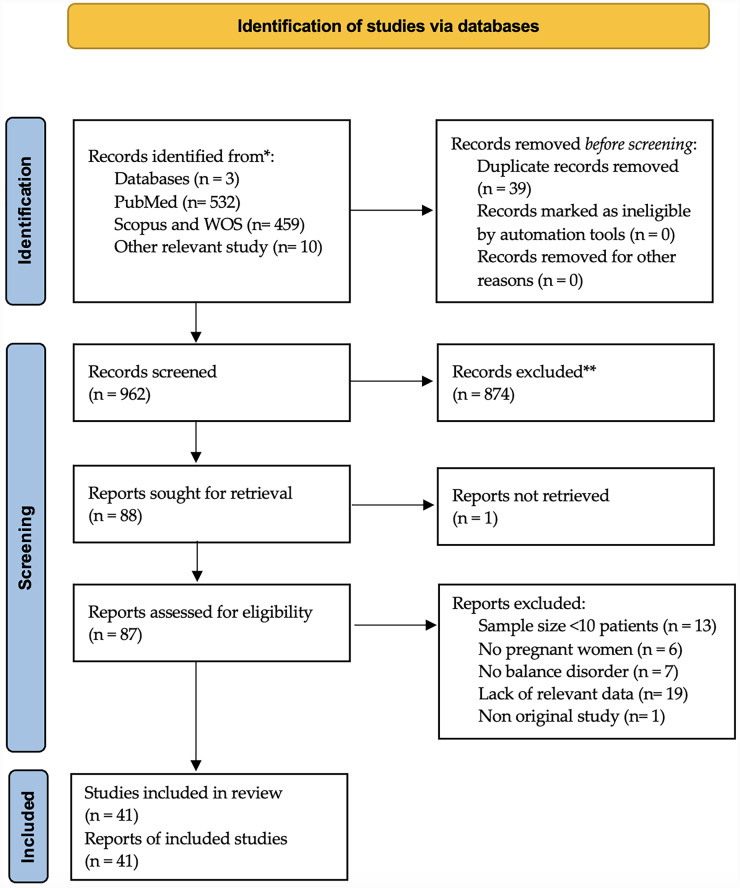

A total of 1001 titles were collected from our literature search. After duplicates removal and exclusion of 921 records due to coherence with the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 41 articles relevant to the topic were examined1,12–51 (see also the PRISMA plot depicted in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram summarising electronic database search and inclusion/exclusion process of the review. *Date of last search, 30 December 2024.

Balance control during pregnancy

Most of the articles retrieved and selected according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria regarded balance control in pregnant women, under either physiological1,12,13,15,18,22–24,27,29–31,34,36–40,43,47 or pathological14,20,25,26,28,32,33,35,41,47,50 conditions. Among the studies focusing on balance control in a physiological pregnancy setting, ten13,15,18,24,29,31,34,36,39,42 considered non-pregnant women as a control group, whereas seven reported comparisons between different gestation epochs.1,12,17,22,29,34,38 Moreover, four studies also reported a comparison between women during pregnancy and in their post-partum period.18,39,40,43

The articles dealing with pathological conditions during pregnancy regarded gestational or type I diabetes,25,52 as well as obesity, 26 hyperemesis gravidarum, 20 low back pain,14,28,41 pregnancy-associated falls32,33,35 and long-term bed rest. 47

From a methodological point of view, most of the included studies focused on static balance, as evaluated by posturographic means,1,12–15,17,18,20,24–26,28,29,33,34,37–41,49,50 whereas eight investigated dynamic balance outcomes.22,23,27,30–32,35,43

The design and main findings of the included studies are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Study size | Population (P) | Intervention (I) | Comparison (C) | Outcome (O) | Study design (S) | Author's conclusion | Quality rating a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abedzadehzavareh Z 12 | 2025 | USA | 23 | Normal-risk pregnant women | Standing balance | Pregnant individuals were assessed longitudinally at 4-week intervals (± 2 weeks) between 18 and 34 weeks of gestation coin- ciding with the peak risk of falling during pregnancy |

Maximum lateral velocity of the COM (mm/s), maximum COM-ankle-vertical angle in frontal plane (degree), and minimum centre of gravity distance to the lateral border (COG-Lat) (mm); anterior-posterior COM excursion; maximum anterior-posterior velocity of COM | Longitudinal case control study |

Waddling gait seems to be a protective mechanism, which pregnant individuals tend to adopt to increase their safety and prevent falling. |

GOOD |

| Bagwell JJ 13 | 2022 | USA | 38 | Pregnant participants during the second and third trimesters | Stand on a force platform | Nulligravida + 4–6 months post-partum | Mean single leg stance time; centre of pressure; mean sway velocity | Longitudinal, case control study | These data may reflect rigidity and inflexibility to adapt to external perturbations, but could also represent a necessary protective strategy during single limb stance, possibly due to fear of falling. | GOOD |

| Bagwell JJ 14 | 2024 | USA | 38 | Pregnant participants during the second and third trimesters | Stand on a force platform | Nulligravida + 4–6 months post-partum | Total sway (sway; the total path of the centre of pressure data across the entire trial), mean sway velocity (the rate of change of the centre of pressure location averaged across the trial period), AP sway, ML sway |

Longitudinal, case-control study |

This study adds to the growing body of research indicating postural control deficits during pregnancy and suggests that postural control may be altered to a greater extent in pregnant individuals with pain, especially when visual input is diminished. | GOOD |

| Bey ME 15 | 2018 | Germany | 120 | Healthy pregnant women | Postural stability with and without maternity support belt | Healthy non-pregnant women | Sway magnitude was determined by total path length, overall sway velocity, sway amplitudes in antero-posterior (A-P) and medio-lateral (M-L); mean position of the Centre of Pressure (CoP); limits of stability (LoS) |

Longitudinal cohort study | The MSB has small but significant effects on postural stability in pregnant and non-pregnant women, leading to a slight reduction in the LoS, representing improved balance, while slightly increasing postural sway in the antero-posterior direction, indicating impaired balance. Due to the conflicting results, the hypothesis that the MSB leads to an improvement in postural stability cannot be clearly rejected or accepted. | GOOD |

| Bhavana G 16 | 2020 | India | 34 | First-trimester pregnant women | Otolith reflex pathway. | Age-matched non-pregnant women. | cVEMP and oVEMP testing | Cross-sectional study | The results of this investigation have shown reduced peak to peak amplitude during the first trimester of pregnancy. The reduction in amplitude has been observed in cVEMP and oVEMP. The reduction in amplitude indicates dysfunction in the otolith reflex pathway. |

POOR |

| Błaszczyk JW 17 | 2016 | Poland | 28 | Healthy pregnant women | Changes in gait and postural stability during pregnancy and after delivery |

After delivery | Gait velocities; stride length; stance phase; swing phase; double support | Longitudinal cohort study | Such changes gave them a safer and more tentative ambulation that reduced the single-support period and, hence, the possibility of instability. The stance and double-support times were mainly affected by the increase in body weight and fear of balance loss during late pregnancy. Additionally, as pregnancy progressed, a significant increase in stance width and a decrease in step length was observed. The latter effect might also result from increased anxiety of falling. |

GOOD |

| Butler EE 18 | 2006 | USA | 24 | Pregnant women | Static postural balance | After delivery + nulligravid control subjects |

Path length, ARD closed/open eyes | Longitudinal cohort study | These data suggest that postural stability declines during pregnancy and remains diminished at 6 to 8 weeks after delivery. | FAIR |

| Cakmak B 19 | 2014 | Turkey | 90 | Pregnant women | Dynamic and postural stability and comparing pregnant women with and without an MSB in each cohort group | Pregnant women without Maternity Support Belts | The measure of postural stability includes the overall (overall stability index [OA]), antero-posterior (antero-posterior stability index [APSI]), medial-lateral (medial-lateral stability index [MLSI]) scores, and the risk of falling (FRT) scores. | Prospective, observational cohort study | In this study, the scores of FRT were significantly lower in each trimester group in women with MSB than in those without MSB. | FAIR |

| Cakmak B 20 | 2015 | Turkey | 41 | Pregnancies complicated by HG during first trimester | Postural balance | Healthy pregnant controls. | Overall stability index (OA), anterior-posterior stability index (APSI), medial-lateral stability index (MLSI) and fall risk test (FRT) scores. | Observational study | This study found that HG adversely affects postural balance during the first trimester. | POOR |

| Castillo-Bustamante M 21 | 2023 | Colombia | 65 | Healthy pregnant women | Functions of the six semi-circular canals, | Healthy pregnant women | VOR gain | Cross-sectional study | Pregnant women may present vestibular changes within the semi-circular canals, mainly at lateral canals starting from the 20th week of gestation until labour. | FAIR |

| Catena RD 22 | 2019 | USA | 15 | Pregnant women | Balance control during gait | Postpartum | The linear COM range of motion in the antero-posterior direction (AP-COM) was calculated. The peak medio-lateral COM velocity (ML-COMv) was calculated. The total angular range of motion of the COM around the ankle joint centres (both right and left ankles) in the medio-lateral (ML-COMΘ) directions was calculated. The maximum medio-lateral angular COM motion for each stride was also calculated (maxML-COMΘ). |

Longitudinal cohort study | Only a small portion of the variance in dynamic balance changes may be explained through anthropometric changes, and there is still significant unexplained variance in statistical analyses. |

GOOD |

| Catena RD 23 | 2020 | USA | 23 | Pregnant women in their second and third trimesters | Walking balance control | Pregnant women were tested at five different times in their second and third trimesters | COMang: Maximum coronal plane COM angle around the ankle joint centre measured in degrees. A greater value indicates poorer control of balance. COMv: maximum velocity of the COM in the medio-lateral direction. A greater value indicates poorer control of balance. COG5th: the minimum lateral distance of the centre of gravity (COG) to the lateral border (lateral location of 5th metatarsal markers). A smaller value indicates poorer control of balance |

Longitudinal cohort study | Kinematic changes seem to be driven by postural changes of the hip, but only have a small correlation to dynamic balance changes. | GOOD |

| Danna-Dos-Santos A 24 | 2018 | USA | 40 | Pregnant women | Postural instability and fall risk during pregnancy. |

Non-pregnant women | COPap and COPml | Longitudinal cohort study | The results indicate the existence of changes in posture and balance behaviour as early as the first trimester of pregnancy. | FAIR |

| Doğan H 25 | 2023 | Turkey | 72 | Pregnant women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus | Proprioception; balance levels. | Healthy pregnant women. | Inclinometer; Berg Balance Scale (BBS) | Prospective case-control study. | Pregnant women with GDM had a minimal decrease in sensation level, and a decrease in position sense and balance level compared to healthy pregnant women. |

FAIR |

| Dumke BR 1 | 2024 | USA | 40 | Pregnant women | Static postural stability with open and closed eyes | Non-pregnant women | Antero-posterior (AP) accelerations root mean square (RMS); medial-lateral (ML) accelerations root mean square (RMS); Visual Sway Ratio; Vestibular Sway Ratio; Proprioceptive Sway Ratio | Cross-sectional study | The small effects observed here contrast prior studies and suggest larger, definitive studies are needed to assess the effect of pregnancy on postural control. This study serves as a preliminary exploration of pregnant sensory and segmental postural control. | GOOD |

| Ficagna N 26 | 2024 | Brasil | 23 | Obese pregnant women: | Balance stability (1) in standing position (orthostasis - without disturbances; (2) with vestibular disturbance (comfortable head circumduction movement; (3) with visual disturbance (eyes closed; (4) with proprioceptive disturbance (on an unstable sur- face – foam rubber mat |

Normal weight pregnant women: | COP Area (mm2); COP Length (cm); COP Velocity (cm/s) | Observational longitudinal cohort study | The progression of pregnancy negatively impacts postural stability throughout its course. Visual disturbance only affected the balance of the control group. Hence, obesity combined with pregnancy does not appear to alter COP variables. | GOOD |

| Flores D 27 | 2018 | USA | 15 | Healthy pregnant women | Walking balance change during pregnancy; methods for identifying tCOM location | Same sample, different gestational week | The maximum (Max), total range of motion (ROM), and average (Ave) angle between the bCOM and vertical in the coronal plane during a complete stride; the linear motion of the bCOM, with superior-inferior, lateral, and anterior-posterior motion; bCOM angular motion around the ankle joint centre; minimum distances of the centre of gravity (COG) and the extrapolated bCOM (xCOM); xCOM (a position measure in space with units in mm) is a measure that simultaneously accounts for COM location and its velocity to “extrapolate” where the COM is going. |

Observational longitudinal study | The results of this study inform clinicians and patients about the gestational stage-associated changes in balance during pregnancy that increase the risk of falling and injury. | GOOD |

| Hrvatin I 28 | 2024 | Slovenia | 63 | Pregnant women with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain | Postural stability | Pregnant women with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain | Velocity of CoP excursion, CoP excursion in the mediolateral (ML) direction expressed as ML path length, CoP excursion in the anteroposterior (AP) direction expressed as AP path length and sway area calculated by principal component analy- sis (PCA) |

Cross-sectional study | Pelvic girdle pain affects the pelvic stabilisation function, disturbances in the automatic movement patterns are present, changes can be seen in the posture and gait pattern, which can directly affect postural stability: Women with PPGP may be at a higher risk of falling and they relied more on visual cues to maintain a stable position. Information on balance issues and fall prevention interventions should be included in the regular treatment of pregnant women with PPGP. |

FAIR |

| Inanir A 29 | 2014 | Turkey | 110 | Pregnant women in the first and second trimester |

Postural equilibrium and risk of falls during pregnancy | Non-pregnant control subjects. | Overall stability index (OA); antero-posterior stability index (APSI) is the front-rear balance ability, while the medial–lateral stability index (MLSI) refers to the ability to balance to the side. The fall risk test (FRT) is evaluated by overall, antero-posterior and medial–lateral stability indexes. |

cross-sectional study | Postural equilibrium decreases during pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester. Using postural stability tests may detect pregnant women with a high fall risk | FAIR |

| Krkeljas Z 30 | 2018 | South Africa | 35 | Healthy pregnant women | Gait and postural control | Women at different trimester of pregnancy | Walking speed, stride length and width, bilateral one-leg stance time and foot clearance height, maximum medio-lateral deviation of centre of pressure (COPML) and centre of gravity (COGML) during single-leg stance. horizontal distance between COP and COG (COP/COG trunk inclination angle) in the coronal plane was also measured; margin of stability is a stability index |

cross-sectional study | The relative weight gain was a significant factor in this study, and that the rate of weight gain was not consistent among individuals. | FAIR |

| McCrory JL 31 (Dynamic postural stability during advancing pregnancy) | 2010 | USA | 81 | Pregnant women | Dynamic postural stability with small, medium, and large anterior and posterior translation perturbations. |

Non-pregnant women | Reaction time, Initial sway was defined as the maximum initial COP movement resulting from the translation of the platform. Sway velocity was defined as the initial sway divided by the time from the onset of COP movement to the time of the initial sway. Total sway was defined as the total anterior–posterior movement of the COP in response to the perturbation. |

cross-sectional study | Alterations to dynamic stability in response to a translation postural perturbation emerged in the third trimester of pregnancy. Specifically, while reaction time was not affected by the pregnancy, the amount of sway following the perturbation was reduced. The implications of this reduction were unclear but suggest that factors other than reaction time and perturbation response might be influencing falls in pregnant women. | FAIR |

| McCrory JL 32 (Dynamic postural stability in pregnant fallers and non-fallers) | 2010 | USA | 69 | Pregnant fallers | Dynamic stability | Pregnant non-fallers + non-pregnant | Reaction time, Initial sway; Sway velocity; Total sway | Cross-sectional and longitudinal observational study |

Pregnant women who experienced a fall exhibited altered dynamic postural stability compared with those who did not fall, as well as with non-pregnant women. Dynamic balance was altered in pregnant women who have fallen compared with non-fallers and controls. Exercise may play a role in fall prevention in pregnant women. Exercise participation may play a role in reducing fall risk. All of the sedentary pregnant women in this study fell during their pregnancies. Although some of the pregnant women who reported exercise participation experienced a fall, the majority did not. | GOOD |

| McCrory JL 33 | 2011 | USA | 69 | Pregnant fallers | Examine the effects of advancing pregnancy and fall history on GRFs (ground reaction forces) during gait. | Pregnant non-fallers + non-pregnant | Walking velocity; Mediolateral excursion of the COP during the stance phase was calculated as the difference between the maximum medial and lateral positions of the COP. The following variables were determined from the antero-posterior shear forces: braking peak, time to braking peak, propulsive peak, time to propulsive peak, and braking and propulsive impulses. Medial and lateral impulses were determined from the medio-lateral shear forces. Passive peak, time to passive peak, active peak, time to active peak, minimum between peaks, time to minimum between peaks, loading rate, and impulse was calculated from the vertical GRFs. Loading rate was calculated as the passive peak divided by the time to the passive peak. |

cross-sectional study | Pregnant women in their latter trimesters as well as pregnant women who have experienced a fall did not demonstrate altered GRF patterns or mediolateral COP excursion during stance compared to a control group of non-pregnant women. When walking velocity was considered in the statistical model, ground reaction forces were essentially unchanged by pregnancy. | FAIR |

| McCrory JL 34 | 2013 | USA | 69 | Pregnant women in their second and third trimesters | Stair locomotion in pregnancy | Non-pregnant women | The following variables were determined from the antero-posterior shear forces: braking peak, time to braking peak, propulsive peak, time to propulsive peak, and braking and propulsive impulses. Medial and lateral impulses were determined from the medial-lateral shear forces. Passive peak, time to passive peak, active peak, time to active peak, minimum between peaks, time to minimum between peaks, loading rate, and impulse were calculated from the vertical GRFs. Loading rate was calculated as the passive peak divided by the time to the passive peak; Ascent velocity; Stance time; The mediolateral excursion of the COP during ascent; |

cross-sectional study | Several GRF variables during staircase locomotion were significantly altered during pregnancy, including the mediolateral excursion of the COP during ascent, the antero-posterior braking impulse in both ascent and descent, and the vertical GRF loading rate during descent. These alterations may contribute to increased fall risk and reflect an altered motor control in pregnancy | FAIR |

| McCrory JL 35 | 2014 | USA | 69 | Pregnant fallers | Stair locomotion in pregnant fallers, pregnant non-fallers, and non-pregnant controls | Pregnant non-fallers + non-pregnant | Braking Pk (BW); Time to braking Pk (s); Propulsive Pk (BW); Time to propulsive Pk (s); Braking impulse (BW s); Propulsive impulse (BW s); Medial impulse (BW s); Lateral impulse (BW s) Passive peak (BW); Time to passive Peak (s); Loading rate (BW/s); Minimum between peaks (BW); Time to min between peaks (s); Active peak (BW); Time to active peak (s); Impulse (BWs) |

cross-sectional study | Pregnant fallers displayed several alterations to staircase locomotion compared to pregnant non-fallers and non-pregnant control women. These changes likely reflected a gait strategy intended to increase stability during staircase locomotion. | FAIR |

| Moreira LS 36 | 2017 | Brasil | 30 | Pregnant women | Control of upright quiet standing | Non-pregnant control subjects. | EMG amplitudes | cross-sectional study | This study provides additional data regarding the functioning and adaptations of the postural control system during pregnancy. Postural control during quiet standing cannot be used to predict the occurrence of low-back pain. The modifications in the neural drive to the muscles, as well as in postural sway may be related to changes in the biomechanics and hormonal levels experienced by the pregnant women. | FAIR |

| Nagai M 37 | 2009 | Japan | 43 | Pregnant women | Postural control standing upright | Non-pregnant women | Enveloped areas of body sway (ENV-AREA) and the ratio of total path length to enveloped area (LNG/ENV-AREA) in pregnant and non-pregnant women standing with the eyes open (open) and closed (closed); Path length of body sway in the medio-lateral (X-LNG) and antero-posterior axes (Y-LNG) |

cross-sectional study | Subjects with high anxiety abstract visual cues differently from those with low anxiety. The maintenance of standing posture in the late trimester is brought about by increasing the reliance on somatosensory cues in the course of responding to physical challenges. When anxiety increases during pregnancy, the standing posture is destabilised. | POOR |

| Oliveira LF 38 | 2009 | Brasil | 20 | Healthy pregnant women | Postural control; stabilometric tests in each of the following standing conditions: (1) eyes open with feet comfortably apart (EO/FA); (2) eyes closed with feet comfortably apart (EC/FA); (3) eyes open with feet together (EO/FT); and finally (4) eyes closed with feet together (EC/ FT). |

None | deflections of the centre of pressure (COP) along the lateral (x) and anterior/posterior (y) axes | Descriptive study | Pregnancy induced significant changes in the postural control when pregnant women stood with a reduced support base or with eyes closed. | FAIR |

| Opala-Berdzik A 39 | 2015 | Poland | 31 | Normal-risk pregnant women | Static postural stability | Same women post-partum | AP path length, AP velocity, ML path length, ML velocity, Total path length, Total velocity | Longitudinal study | Under visual deprivation conditions women in advanced pregnancy may have decreased static stability compared to their non-pregnant state | GOOD |

| Opala-Berdzik A 40 | 2018 | Poland | 17 | Normal-risk pregnant women | Correlation between women's trunk flexibility and their postural stability | Same women post-partum | CoP anterior-posterior mean velocity. | Longitudinal study | Increased total trunk flexibility may be presented in women 6 months postpartum. During that period, women with higher trunk flexibility may be more likely to present higher antero-posterior postural sway velocity in quiet standing. | GOOD |

| Öztürk G 41 | 2016 | Turkey | 68 | Women in the third trimester of pregnancy with lower back pain | Static postural stability | Women in the third trimester of pregnancy without lower back pain | Using Tetrax posturography: stability index (SI), frequency bands of postural sway (F1, F2–F4, F5–F6 and F7–F8) and fall risk. | Cross-sectional study | LBP had a negative effect on postural stability. Postural equilibrium decreased and fall risk increased in pregnant patients with LBP. | GOOD |

| Ramachandra P 42 | 2023 | India | 80 | Primigravidae at the 32nd week of pregnancy | Static postural sway, with open and closed eyes | Non-pregnant women | Antero-posterior (AP) sway velocity (mm/sec), mediolateral (ML) sway velocity (mm/sec) and the velocity moment (mm2/sec). | Cross-sectional study | The postural sway of pregnant women in the third trimester was significantly larger compared to non-pregnant women when exposed to conditions in which visual input, proprioceptive input, and base of support were compromised. Medio-lateral sway velocity did not show any significant difference between the groups except for eyes open and eyes closed conditions on a firm surface when the stance width was controlled. Pregnant women adopted wider stance width in the advanced stage of pregnancy. | GOOD |

| Rothwell SA 43 | 2020 | USA | 17 | Normal risk pregnant women | Dynamic balance | Same women, post-partum |

Step width, linear range of medial-lateral COM motion (ML COM) over the stride, the maximum medial-lateral COM velocity (ML COMv) during the stride, and medial-lateral angular range of motion of the COM around the ankle joint centre (ML Angle) | Longitudinal observational cohort study | Balance was found to significantly improve just following birth. There were changes that continued to indicate improvements throughout the post-partum period. Anthropometry changes were significantly, but minimally, correlated with balance changes. | GOOD |

| Salvati A 44 | 2020 | Italy | 11 | Pregnant women | Audio-vestibular evaluation | NA | 1 pregnant woman with right total deafness and vestibular areflexia, 7 patients presented BVPP, 3 vestibular neuritis | Retrospective case series | The importance of multi-disciplinarily between otolaryngologist, neurologist and gynaecologist have to be highlighted. Vascular aetiology, strictly related to the gravidic hormonal variations, has been often hypothesised. | POOR |

| Sawa R 45 | 2015 | Japan | 27 | Pregnant women (pregnancy ≥ 28 weeks) | Gait and functional ability of the trunk | Pregnant women (pregnancy <27weeks) | Gait velocity, Stride time, Stride length, Index of gait variability Stride time CV (coefficient of variation); autocorrelation coefficient: vertical, mediolateral, anteroposterior | Cross-sectional study | The functional ability of the trunk declines in late pregnancy. Women during the third trimester of pregnancy showed a significantly smaller RMS and CoA in the antero-posterior lower trunk than those before the third trimester of pregnancy. | GOOD |

| Schmidt PM 46 | 2010 | Brazil | 82 | Normal risk pregnant women | Audio-vestibular evaluation with the interview protocol Castagno | NA | Main auditory complaints, dizziness occurrence, dizziness related symptoms, dizziness-associated symptoms. | Prospective study | The most frequent auditory complaint in pregnant women was tinnitus; dizziness was reported by more than half of the pregnant women, being more frequent in the first two gestational trimesters. Nausea was the main symptom associated with dizziness. It is possible that a vestibular alteration stemming from the hormonal alteration causes vertigo in the first gestational trimester, and this complaint reduces in the following trimesters. | POOR |

| Shibayama Y 47 | 2016 | Japan | 161 | Pregnant women with bed rest | Static postural stability | Pregnant women without bed rest | (1) total distance moved by the COG (reflecting the distance of sway (cm)), (2) track area, indicating the area covered by COG movement (reflecting the extent of sway [cm 2 ]), (3) average medial – lateral (right-left) deviation of the COG (reflecting the degree of medial – lateral sway: a positive value indicates average COG deviation to the right [cm]), and (4) average antero-posterior deviation of the COG (reflecting the degree of antero-posterior sway: a positive value indicates average COG deviation anteriorly (cm)). | Case-control study | Pregnant women with bed rest for as long as 4 weeks showed the same stabilometry-measured body sway as those without bed rest. Pregnant women with oedema showed increased medial lateral instability. | GOOD |

| Skarica B 48 | 2018 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 55 | Pregnant women with dizziness | Manual treatment over pregnancy symptoms (including dizziness) | NA | Number of treatments, Number of relapses, Successfulness | Prospective controlled study | Manual therapy in pregnancy is a drugless, aetiological, usually highly effective therapy. It is a low-cost, rapid, safe and well-tolerated treatment for pregnancy symptoms. | GOOD |

| Tulmaç OB 49 | 2020 | Turkey | 70 | Normal risk pregnancy with hyperemesis gravidarum | Semi-circular canal functions of the vestibular system (vHIT) | Healthy pregnant women without nausea and vomiting | VOR gain in every semi-circular canal | Prospective case control study | Semi-circular canal functions were not abnormal globally in women with hyperemesis gravidarum. However, higher LARP plane asymmetry and low LA gain in women with hyperemesis suggested a need for further research to clarify the functional role of vestibular system on hyperemesis gravidarum. | GOOD |

| Valerio PM 50 | 2020 | Brazil | 40 | Pregnant women in their third gestational trimester with type 1 diabetes | Postural and balance evaluations | Pregnant women in their third gestational trimester without type 1 diabetes | APToe (antero-posterior distance trajectory of the centre of pressure with eyes open); APTce (antero-posterior distance trajectory of the centre of pressure with eyes closed); MLToe (medio-lateral distance trajectory of the centre of pressure with eyes open); MLTce (mediolateral distance trajectory of the centre of pressure with eyes closed); SAPoe (average speed of the antero-posterior distance trajectory of the centre of pressure with eyes open); SAPce (average speed of the anteroposterior distance trajectory of the centre of pressure with eyes closed); SLMoe (average speed of the lateral to medial distance trajectory of the centre of pressure with eyes open); SLMce (average speed of the lateral to medial distance trajectory of the centre of pressure with eyes closed); APAoe (antero-posterior amplitude of the centre of pressure displacement with eyes open); APAce (anteroposterior amplitude of the centre of pressure displacement with eyes closed); MLAoe (medio-lateral amplitude of the centre of pressure displacement with eyes open); MLAce (medio-lateral amplitude of the centre of pressure displacement with eyes closed); | comparative observation study | Pregnant women with diabetes mellitus in the third trimester of gestation presented lower adaptation of the column curvatures, lower active ankle range of motion, and increased anteroposterior oscillation of the centre of pressure that may interfere in postural control. | GOOD |

| Wu PH 51 | 2017 | Taiwan | 68 | Normal-risk pregnant women with inner ear diseases | Audio-vestibular evaluation | NA | inner ear diseases frequency during pregnancy and treatment (34 vestibular migraine, 14 sudden deafness, 10 autonomic related vertigo, 6 peripheral vertigo, 3 Ménière disease, 1 VN). | Retrospective case series | More than 70% of inner ear disorders in pregnant women are attributed to vestibular migraine and sudden deafness, and audiometry helps differentiate between the two diseases. The highest abnormality of the inner ear test battery in pregnant women was cVEMP test, likely because half of the patients were vestibular migraine, which has been correlated with abnormal cVEMPs. | POOR |

AP: anterio-posterior; AP sway: the maximum distance between the most anterior and posterior locations of the centre of pressure across the trail period; ARD: average radial displacement; COG-Lat: minimum centre of gravity distance to the lateral border; bCOM: body centre of mass; BVPP: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; cm: centimetre; CoA: coefficient of attenuation; COM or CoM: centre of mass; COP or CoP: centre of pressure; COPap: centre of pressure coordinates in anterior-posterior direction; COPml: centre of pressure coordinates in medial-lateral direction; cVEMP: cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential; FRT: fall risk test; GDM: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus; GRF: ground reaction force; HG: hyperemesis gravidarum; LA: left anterior; LARP: left anterior–right posterior; LBP: lower back pain; ML: medio-lateral; ML sway: maximum distance between the most medial and lateral locations of the centre of pressure across the trail period; mm: millimetre; MSB: maternity support belt; NA: not applicable; oVEMP: ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potential; PPGP: pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain; RMS: root mean square; tCOM: torso centre of mass; vHIT: video head impulse test; VN: vestibular neuritis; VOR: vestibulo-ocular reflex.

Quality rating according to the NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools).

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

Four reports in the literature described BPPV cases during pregnancy.44,52–54 In 2017, Çoban et al. 48 reported four cases of pregnant women diagnosed with BPPV for the first time during gestation. In all cases, posterior semi-circular canal BPPV (two on the left side and two on the right) was diagnosed by Dix-Hallpike test and the Epley manoeuvre for canalith-repositioning was performed. In three out of four cases, the manoeuvre was successful at the first attempt; in one case, it was necessary to repeat it. One additional case was described by Sun et al. 53 in a 26-year-old parturient woman who experienced a left posterior semi-circular canal BPPV two hours after the positioning of an epidural catheter. The Dix-Hallpike test confirmed the diagnosis and the Epley manoeuvre was used for treatment. Delivery was successful 18 h after commencing epidural analgesia and the woman was discharged 3 days later without BPPV recurrence. In 2020, Salvati et al. 44 found 7 cases of BPPV among 11 pregnant women presenting with acute rotatory vertigo. Specifically, four patients suffered from posterior semi-circular canal BPPV (two on the right side and two on the left) confirmed by the Dix-Hallpike and/or Semont manoeuvres; in the remaining three patients, the right horizontal canal was involved with a geotropic variant. All seven patients were successfully treated by canalith-repositioning manoeuvres. Salvati et al. 44 additionally described one case of right posterior semi-circular canal VPPB due to Lindsay-Hemenway syndrome. 55 Four more cases of BPPV in pregnant women without previous histories/risk factors of otological diseases but confirmed by Dix-Hallpike test were reported by Swain et al. 54 : no further details were provided.

Vestibular neuritis (VN)

Few cases of VN have been reported, primarily within retrospective, monocentric studies focused on otological disorders during pregnancy.44,51 Among 68 pregnant women showing inner ear complaints, Wu et al. 51 identified 6 cases of peripheral vertigo, encompassing both VN and herpes zoster oticus. However, the study did not distinguish between these two conditions, nor did it provide details regarding diagnostic protocols, therapeutic strategies, or long-term follow-up. Salvati et al. 44 described 3 clinically confirmed cases of VN in their series of 11 pregnant woman with acute objective vertigo. All three patients were treated with corticosteroids, resulting in significant symptoms relief within 4–5 days and complete recovery within one month.

Ménière disease

There are few available reports on the course of Ménière disease during and after pregnancy. In 1997, Uchide et al. 56 described the case of a 28-year-old woman with a recent diagnosis of Ménière disease. The vertigo attacks increased up to 10 times/month during early pregnancy, when the serum osmolality was significantly below normal. As the pregnancy proceeded, the serum osmolality normalised and the vertigo attacks decreased in frequency. The vertigo attacks were treated by oral isosorbide and intramuscular injection of low-dose diazepam. Stevens and Hullar 57 described the rare case of a patient with a history of Ménière's disease and vestibular migraine who experienced temporary hearing recovery during two successive pregnancies. An improvement in hearing was found by the third trimester during each pregnancy, with a rapid return to baseline thresholds after delivery. In 2017, Wu et al. 51 considered 68 consecutive pregnant women with newly developed inner ear symptoms, that were vertigo/dizziness, hearing loss or tinnitus who were encountered at the Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, New Taipei in the period from 1995 to 2014. Diagnoses comprised vestibular migraine in 34 patients, sudden deafness in 14, autonomic-related vertigo in 10, VN or herpes zoster oticus in 6, Ménière disease in 3 and vestibular schwannoma (VS) in one. The patients with Ménière disease were identified at the first (two cases) and second (one case) trimesters; none of them was encountered at the third trimester. Analysing 84 pregnant women participating in a prospective study in eastern India, Swain et al. 54 found 9 cases showing true vertigo; 2 of them were diagnosed with Ménière disease, 4 with BPPV and 3 with VN. No detailed clinical data were provided on the two cases of Ménière disease.

Vestibular schwannoma (VS)

Our literature analysis showed that VS is rarely presented in pregnant women. A 31-year-old primipara manifested vertigo associated with left side deafness and facial palsy at 31 weeks of gestation 58 ; the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 4-cm VS at the left cerebellopontine angle. The patient underwent a caesarean section for delivering two healthy babies. After 2 weeks, she underwent craniotomy for VS removal. Both postpartum and post-operative courses were free of complications and facial nerve function was recovered 1 year later. 58 In 2014, Shah and Chamoun 59 reported the case of a 20-year-old primigravida at 26 weeks’ gestation with gait imbalance, left facial weakness, left ear hearing loss, nausea and vomiting. MRI revealed a large left cerebellopontine angle mass with extension into the left internal auditory canal and compression of the fourth ventricle. At the 33rd week, the patient's headache and neurologic symptoms worsened due to increased hydrocephalus: a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was placed. An emergency caesarean delivery was performed due to worsening respiratory status. A tracheostomy was done and a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed because of dysphagia. Eight days after the delivery, the mass was resected with a left retro-sigmoid approach without complications. The patient was discharged to inpatient rehabilitation on postoperative day 12 without new neurologic deficits. In 2023, Bao et al. 60 described the case of a pregnant woman with a giant VS and obstructive hydrocephalus occurred at 30 weeks of gestation. A ventricular-peritoneal shunt was placed for hydrocephalus, corticosteroids were used to stimulate foetal maturation. After 10 days, the patient's mental conditions deteriorated, and right limb muscle strength gradually decreased. The patient underwent a caesarean section and VS removal at 31 weeks of gestation. Upon discharge, the previously observed neurological deficits were successfully resolved, and the foetus conserved. Very recently, Kadir et al. 61 reported the case of a pregnant woman at 36 + 5 weeks of gestation diagnosed with a large VS exhibiting brainstem compression, peritumoral oedema and cranial nerve encasement. A conservative approach involving close monitoring and corticosteroid therapy was initially preferred. As the patient neared full term, a carefully planned caesarean section was performed, followed by a craniotomy for VS removal. Post-operatively, the mother and new-born showed favourable outcomes.

Vestibular migraine

Only one investigation 51 describing pregnant women with vestibular migraine, emerged from the literature review. Among a series of 68 pregnant women with newly-developed vestibular symptoms during gestation, according to the criteria at that time proposed by the Barany Society and International Headache Society, 62 34 (50%) were diagnosed as vestibular migraine. 51 Symptoms developed during the 1st, 2nd and 3rd trimester in 4, 10 and 20 patients, respectively. None of them received oral medication but they were reassured. 51 As previously mentioned, a rare case of a patient with a concurrent history of vestibular migraine and Ménière's disease who experienced temporary hearing recovery during two successive pregnancies has also been reported.

Discussion

Nowadays, although some studies claimed no changes in postural behaviour during pregnancy, 39 most of the available evidence seems to demonstrate significant modifications in posture and balance metrics, with multiple mechanisms.18,27,63 In particular, regarding the static balance domain, in their case-controlled investigation, Danna-Dos-Santos et al. 24 found that, along with gestation progression, the body's centre of pressure seemed to migrate posteriorly, while the anterior pelvic tilt appeared to increase. Furthermore, from a dynamic viewpoint, significantly larger body sway accompanied by a more regular medial-lateral pattern of oscillation and a more synchronised anterior-posterior and medial-lateral sway were found in pregnant women, compared to non-pregnant ones. 24 Such findings might be consistent with a possible increase in co-dependency of postural sway dynamics between anterior-posterior and medial-lateral directions during pregnancy. 64 Such postural changes may result in a tendency toward a greater use of feedforward or anticipatory mechanisms in pregnant women, instead of feedback ones, as safer ways to control medial-lateral balance and avoid falls. 64 As a general principle, active gait control is exerted to accelerate the centre of mass in the desired direction, by either changing the motion direction to anticipate the effect of possible perturbations (feedforward control) or varying muscle activity in response to external stimuli (feedback control). 65 Regarding the feedback control, proprioceptive information on the centre of mass state and its relation to the base of support are required. 65

An implication of postural modifications in pregnant women could be the development of lumbar spine and pelvic girdle instability, leading to pain and discomfort.28,41 In their recent investigation on 63 pregnant women, Hrvatin et al. 28 found a significant association between pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain and greater centre-of-pressure velocity and sway area, especially during the third trimester of pregnancy. This might be explained by a poorer ability to stabilise the trunk and pelvis, and poorer proprioception, leading to pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain in patients with higher centre-of-pressure velocity and sway area. 28 Moreover, such balance impairments seemed to reflect also on risk of fall. 66 In fact, women with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain seemed to have poorer static stability and fall more often than those without pain. 28

Physiological changes that occur in the mother's body during pregnancy have been considered as a possible substrate for developing vestibular disorders. 8 According to reported evidence, dizziness and vertigo were reported in pregnancy in small, low-quality studies. BPPV, VN, Ménière disease, vestibular migraine and VS have all been documented in pregnant women.51,54,67

BPPV during pregnancy

BPPV has been described as an acute episodic, brief, paroxysmal rotational vertigo, triggered by head position changes. 68 BPPV is the most common vestibular disorder across the life span, with a reported 69 lifetime prevalence of 2.4%. Women are more frequently affected, 70 with a female to male ratio of 2:1. Two clinical variants of BPPV are mostly encountered. Posterior canal-related BPPV constitutes approximately 85% to 95% of cases; the lateral (horizontal) canal one accounts for 5% to 15% of cases.71,72 The involvement of the superior (anterior) canal is uncommon, reported in about 3% of cases. 73 Although BPPV may sometimes be associated with trauma, migraine, previous inner ear damage from a viral or ischaemic cause, diabetes, osteoporosis and lying in bed for long periods, in most cases it is idiopathic.74,75 However, it has been observed that serum level of vitamin D was significantly lower in patients with idiopathic BPPV, so that vitamin D supplementation might help in preventing BPPV recurrence. 75

Whether pregnancy represents a risk factor for exacerbating BPPV is unclear and available reports are very limited. Several hypotheses underlying BPPV occurring during pregnancy have been proposed. Firstly, it may be due to prolonged bed rest or related to sleeping on the left side (as is recommended to reduce compression of the vena cava during pregnancy), although we did not find a semi-circular canal side prevalence among the reported cases. Moreover, a role of hormonal alterations during pregnancy has been hypothesised. 76 Oestrogen helps to maintain normal inner ear function; during the late trimesters, low and fluctuating oestrogen levels may lead to otoconial degeneration, 76 similarly to what happens to menopausal women. 77 Likewise, calcium and Vitamin D metabolism seems to be essential in preventing inner ear degeneration. Emerging research suggested a patho-physiological link between Vitamin D deficiency and BPPV. 78 BPPV first occurrence during pregnancy could be related to Vitamin D deficiency and calcium metabolism disturbances during the second trimester, due to an increased calcium reabsorption in many systems, such as the kidney and bone, and increased metabolic demands of the foetus. 79 Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy seems to have benefits both on maternal and neonatal health outcomes, reducing the risk of pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, low birthweight and severe post-partum haemorrhage.80,81 Considering its apparent pathogenetic role in BPPV, 78 vitamin D integration in pregnant women may also play a role in preventing pregnancy-related BPPV.

Vn during pregnancy

VN is referred to as acute unilateral vestibulopathy, a disorder characterised by acute onset of long-lasting vertigo accompanied by nausea, vomiting and imbalance, without other audiological or neurological symptoms. 82 VN arises from inflammation of the vestibular nerve; the typical age of onset is between 30 and 60 years. 83 It has been hypothesised that the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy might exacerbate microvascular compromise, which has been reported as a possible cause of VN.44,51,83,84 Moreover, pregnancy-induced immunological changes, such as a shift towards a more tolerogenic immune environment, could predispose both to primary viral infection and viral reactivation – in the case of latent herpes simplex virus (HSV) – which have been implicated as leading causes in VN.44,51,85 According to Shi et al., 86 HSV infection during pregnancy was associated with a significantly increased risk of spontaneous abortion (OR: 3.81), premature birth (OR: 3.83) and stillbirth (OR: 1.78). Therefore, direct collaboration between otolaryngologists and gynaecologists in the care of women experiencing VN during pregnancy is appropriate.

As highlighted in the Results section, VN during pregnancy has been infrequently reported in the existing literature, with only two retrospective studies documenting fewer than 10 cases. Both studies lacked a thorough diagnostic workup, detailed therapeutic data and long-term follow-up, thereby significantly constraining our understanding of this disorder in the context of pregnancy.44,51 Furthermore, two recent case reports highlighted the presentation and management of VN in pregnant women.87,88 Gökgöz et al. 88 reported the case of a 33-year-old woman at 28-gestation-week presenting with sudden-onset vertigo, nausea and vomiting. Diagnostic tests confirmed right-side vestibular neuritis, with vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP) revealing prolonged P1-N1 latency. Treatment included intravenous dexamethasone, vitamin B6-B12 complex and metoclopramide, avoiding vestibular suppressants due to potential foetal risks. The patient delivered a healthy baby without complications. Vestibular recovery was supported by appropriate rehabilitation exercises. 88 Aasfara et al. 87 reported the case of a 36-year-old pregnant woman at 37 weeks of gestation who showed vestibulo-cochlear neuritis as part of a Guillain-Barré Syndrome variant following SARS-CoV-2 infection. The patient exhibited sudden-onset vertigo, nausea and right-sided vestibular areflexia, confirmed by video-nystagmography and pure-tone audiometry. A treatment with corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulins led to significant hearing recovery, with a vestibular function improvement confirmed at six weeks follow-up. 87 Diagnosing VN during pregnancy is feasible and relies primarily on a thorough clinical history. Examination findings, such as spontaneous unidirectional nystagmus and a positive head impulse test (HIT) on the affected side are keystones of the diagnosis. 44 Additional non-invasive tests, such as video-nystagmography, VEMPs or video-HIT, can confirm vestibular dysfunction. Gökgöz et al. 88 stated that, since caloric testing was not critical for the immediate management of VN, it could be safely performed after labour. This approach minimises patient's discomfort and avoids unnecessary risks during pregnancy, aligning with the principle of prioritising maternal and foetal well-being.

Management of VN in pregnant women should focus on symptomatic relief while minimising risks to the foetus. Non-pharmacological approaches, including vestibular rehabilitation therapy (VRT), should be prioritised. 88 VRT plays a pivotal role in promoting central compensation, improving balance and alleviating vertigo. 89 Exercises focusing on gaze stabilisation, postural control and habituation to motion sensitivity are typically included in rehabilitation programmes. 90 The significant changes in body weight and centre of pressure associated with advancing pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester, necessitate careful monitoring and adaptation of VRT to ensure both safety and effectiveness. Key considerations include: (i) creating supportive environments by incorporating balance aids or rails to enhance safety; (ii) modifying exercises that involve walking or stepping, such as the Fukuda test or Tandem gait, by prioritising slow, controlled movements and using external support to minimise the risk of falls; (iii) adapting Cawthorne-Cooksey Exercises to emphasise seated or supported positions, reducing physical strain and preventing fatigue. 91 In conclusion, for pregnant patients with VN, supervised VRT 89 is strongly recommended. Collaboration with clinicians experienced in both VRT and prenatal care is essential to develop a tailored and effective rehabilitation programme. This allows safe procedures optimising recovery outcomes for pregnant patients. If needed, pharmacological treatments – steroids and antiemetics – should be used in consultation with gynaecologists.44,87,88 Further research is warranted to understand the prevalence, triggers and optimal management strategies for VN in pregnancy. Multicentric studies could provide valuable insights into safe and effective treatment protocols tailored to pregnant VN patients.

Ménière disease management during pregnancy

Ménière disease is histologically characterised by endolymphatic hydrops in the inner ear. 92 Hormonal fluctuations (such as those experienced during puberty, monthly cycling, pregnancy and menopause) have been found to play an important role in vestibular conditions, including Ménière disease.93–96 The role of sex hormones in females with Meniere's disease has been investigated mainly in post-menopause. 97 There are few reports on the course of Ménière disease during pregnancy. Uchide et al. 56 hypothesised that Ménière's disease might be expected to worsen during early pregnancy because of the sudden decrease of serum osmolality inducing an osmotic gradient between outer and inner endolymphatic sac, so that free water could enter the endolymphatic space exacerbating endolymphatic hydrops.

Salt and caffeine restrictions have been advised for the treatment of Ménière disease. 79 Dimenhydrinate and meclizine are safe when used in low doses to treat nausea and related vertigo in Ménière disease patients. 98 Although betahistine is rarely used during pregnancy and there are no adverse event data published, 99 it should be used with caution. 79

Vs management during pregnancy

VS is a benign tumour of the 8th cranial nerve and comprises 90% of cerebellopontine angle tumours and 8% of all intracranial tumours. 100 The incidence is increasing and ranges from 11 to 19 VS/million/year. 101 Patel et al. 102 aimed to determine by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction the role of oestrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression in 23 sporadic VSs. Fifty-two percent of sporadic VS samples upregulated ER, and 69.6% of samples upregulated PR. The hormonal status of VS was investigated because of the possible induction of vascular endothelium by oestrogenic stimulation. Endoglin (CD105) is a proliferation-associated protein expressed in angiogenic endothelial cells, 103 and a potential prognostic indicator for several solid tumours.104,105 Marioni et al. 106 investigated the expression and role of CD105 in a series of 71 sporadic VSs. Based on CD105 expression assessments, a significant positive correlation was identified between vessel cross-sectional area and tumour size, and between vessel density and VS size. Considering pregnancy, high levels of hormones, especially in the late trimester, may be a factor in promoting VS growth. 60 Due to the increased blood volume, increased jugular vein pressure and oestrogen levels during pregnancy, VS is at a higher risk of exacerbation related to increased oedema, peritumoral effusion and the formation of intra-tumoral bleeding. Previously, it has been observed that VSs presenting during pregnancy tended to be larger, suggesting that the biology of the tumour may be altered during pregnancy, resulting in an increased risk of tumour progression. 60 Diagnosis and management of VS during pregnancy present a therapeutic challenge. In cases where VS is asymptomatic during pregnancy, the preferred course of action is to monitor the mother and foetus closely, followed by tumour removal after delivery. 59 For symptomatic VSs, intervention is recommended to minimise complications for both the mother and foetus. In cases of late-stage tumour discovery, delivery of the foetus is required immediately, followed by VS resection. All options should be carefully considered; consulting a multidisciplinary team of gynaecologists, anaesthesiologists and oto-neurosurgeons provides the best outcome for both mother and foetus. 61

Vestibular migraine during pregnancy

Vestibular migraine is an increasingly recognised variant of migraine associated with vestibular symptoms, accompanied or not by migraine's headache. Vestibular migraine has a reported prevalence of 2.7% in the general population, mainly affecting females rather than males (3 to 1 ratio). 107 Diagnosis is made according to the criteria defined by the Consensus of Bárány Society 62 and the Third Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. 108 Vestibular symptoms can be of moderate or severe intensity, including rotational vertigo, postural imbalance, head motion-induced dizziness and visually induced vertigo. Acute episodes usually last between 5 min and 72 h. 109 Conditions mimicking BPPV and auditory symptoms overlapping Ménière disease have also been reported. 110 Headache is not always present in every attack, whereas other migraine symptoms, such as photophobia, osmophobia, visual aura, autonomic symptoms, emotional lability, can be encountered in most of the patients with vestibular migraine. 111 Similarly to migraine, vestibular migraine can be influenced by pregnancy, although clear evidence is lacking. Physiologic changes to the endocrine, haematologic and vascular systems during pregnancy may affect patho-physiological processes of migraine during gestation. 112 Elevated oestrogen levels, which no longer fluctuate, lead to improved migraine symptoms, particularly migraine without aura. 112 Conversely, migraine with aura is less likely to improve during pregnancy or it can more frequently occur ex novo. Likewise, vestibular migraine symptoms may either improve or exacerbate in pregnant women, but consistent studies are not available. The most relevant issue of vestibular migraine during pregnancy is a correct diagnosis. Diagnosis of vestibular migraine in pregnant women is challenging, due to debilitating symptoms, particularly vertigo, nausea, vomiting, osmophobia and allodynia, which may mimic or be masked by nausea and vomiting typical of early gestational stages. 113 Other paroxysmal vestibular disorders or pregnant neuropsychiatric complaints (i.e. anxiety, depression) and hypertensive disorders make the differential diagnosis even more difficult, and vestibular migraine may remain an underdiagnosed and undertreated condition in pregnancy. 113

Even though data in the literature are scarce, the awareness of diagnosis of vestibular migraine in pregnant women presenting with vertigo or dizziness, should be high among healthcare practitioners, to promptly identify and manage the condition, to exclude secondary pregnancy-related headache disorders (i.e. cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, preclampsia and cerebrovascular disease), 113 and to prevent psychological and quality of life deterioration.

Managing vestibular migraine in pregnancy can be challenging. Currently, there are no robust evidence-based approaches for prophylaxis or acute treatment of vestibular migraine, and therapeutic recommendations are generally extrapolated from studies on classical migraine. 114 Non-pharmacological treatments, such as vestibular rehabilitation therapy and lifestyle modifications, are typically recommended as first-line options. In more severe cases, many standard migraine treatments can be safely used in pregnancy. 113 Analgesic agents such as paracetamol and, carefully, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (up to 34 weeks of gestation) can be used to treat the headache component of vestibular migraine. 115 Nausea can be managed by antihistamines (i.e. prochlorperazine) or metoclopramide. 116 Also, first-line prophylactic treatment (aspirin, beta-adrenergic receptor blockers, tricyclic antidepressants) can be safely used. Even though data for aspirin prophylaxis in vestibular migraine are lacking, low-dose aspirin is prescribed in pregnant patients with classical migraine; it is considered safe and widely used to reduce pre-eclampsia risk. 115 Propranolol has proven effective as a prophylaxis, resulting in vestibular symptoms improvement. 117 Amitriptyline showed overall clinical benefit in headache and vertigo as well, even if during pregnancy its use showed a slightly increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. 115 Other drugs used for migraine second-line prophylaxis treatment, such as calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and anticonvulsants, are conversely not recommended due to lack of safety data and risk of teratogenesis. 113 Clinical research about the safety of novel treatment options for migraine during pregnancy, such as botox 118 and Calcitonin Gene-related peptide blocking monoclonal antibodies, is still needed.119,120

Safe and effective personalised management plans are crucial for pregnant women experiencing vestibular migraine.

Limitations, strengths and perspectives

The main limitation of this comprehensive review is definitely the relevant heterogeneity of measures and evaluation methods across the included studies, which prevented the possibility of a quantitative pooled analysis. Moreover, most of the available data regarded static/dynamic postural balance control during pregnancy, rather than vestibular function. In fact, this review highlights a lack of solid information on vestibular disorders in pregnant patients due to the limited number of reported cases, diagnostic methods, but also to treatment inhomogeneity.

On the other hand, the primary strength of this review lies in the article selection process, with circumscribed inclusion/exclusion criteria, allowing for the inclusion of original articles with an overall good or fair quality rating, according to the NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools; see also Supplemental Table 1). Moreover, despite the between-study heterogeneity, the available evidence on balance control during pregnancy has been qualitatively evaluated, to draw a detailed picture of the state of knowledge on this topic. In addition, the identification of specific knowledge gaps, particularly regarding vestibular function in pregnant women, may prompt future research, possibly leading to improved study designs and greater consistency in findings.

Conclusions

Judging from the findings of this review, many of the physiological changes in pregnancy, including shifting centre of gravity and hemodynamic changes, may result in symptoms of disequilibrium. Most of the available data about pregnant women focus on static or dynamic postural balance control rather than vestibular function. On the other hand, a substantial lack of information on vestibular disorders during pregnancy emerged. In particular, the scattered reports on specific vestibular conditions (mainly single case reports or small observational series) may not allow any generalisable conclusion to be derived.

To overcome such limitations, prospective studies, preferably multicentre and with the collaboration of third-level audio-vestibular centres are mandatory in order to reach numbers that allow rational and effective diagnostic and treatment approaches to be defined for vestibular disorders to protect the safety of the mother and foetus.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sci-10.1177_00368504251343778 for Balance control and vestibular disorders in pregnant women: A comprehensive review on pathophysiology, clinical features and rational treatment by Leonardo Franz, Andrea Frosolini, Daniela Parrino, Giulio Badin, Valentina Piccoli, Giovanni Poli, Anna Giulia Bertocco, Giacomo Spinato, Cosimo de Filippis and Gino Marioni in Science Progress

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Alison Garside for correcting the English version of this paper.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Leonardo Franz https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2306-4088

Andrea Frosolini https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1347-4013

Giulio Badin https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8581-5660

Author contributions: The conception and design of the study: G.M. Acquisition of data: G.B., G.P., G.B. Data analysis and interpretation: L.F., A.F., D.P., G.M. Drafting the article: L.F., A.F., D. P., V. P. Revising the article critically for important intellectual content: L.F., A.F., D. P.; V. P., G. S., C.d.F.; G.M.. Supervision: L. F., C.d.F., G.M. Final approval of the version to be submitted: All authors.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Università degli Studi di Padova (grant number DOR2399707/23 (G. Marioni)).

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Dumke BR, Theilen LH, Shaw JM, et al. Sensory integration and segmental control of posture during pregnancy. Clin Biomech 2024; 115: 106264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandra M, Paray AA. Natural physiological changes during pregnancy. Yale J Biol Med 2024; 97: 85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forczek-Karkosz W, Masłoń A. Postural control patterns in gravid women—A systematic review. McCrory JL, ed. PLoS One 2024; 19: e0312868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sell TC. An examination, correlation, and comparison of static and dynamic measures of postural stability in healthy, physically active adults. Phys Ther Sport 2012; 13: 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo W, Huang Z, Li H, et al. Regulation of static and dynamic balance in healthy young adults: interactions between stance width and visual conditions. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2025; 13: 1538286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldie PA, Bach TM, Evans OM. Force platform measures for evaluating postural control: reliability and validity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1989; 70: 510–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoffregen TA, Yoshida K, Villard S, et al. Stance width influences postural stability and motion sickness. Ecol Psychol 2010; 22: 169–191. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frosolini A, Marioni G, Gallo C, et al. Audio-vestibular disorders and pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Otolaryngol 2021; 42: 103136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2021; 10: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cazzador D, Astolfi L, Daloiso A, et al. Tumor microenvironment in sporadic vestibular schwannoma: a systematic, narrative review. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24: 6522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, et al. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Adelaide: JBI; 2024. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. doi: 10.46658/JBIMES-24-01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abedzadehzavareh Z, Catena RD. The role of waddling gait in balance control during pregnancy. Gait Posture 2025; 116: 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagwell JJ, Reynolds N, Katsavelis D, et al. Center of pressure characteristics differ during single leg stance throughout pregnancy and compared to nulligravida individuals. Gait Posture 2022; 97: 43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagwell JJ, Reynolds N, Katsavelis D, et al. Investigating postural control as a predictor of low back and pelvic girdle pain during and after pregnancy. Clin Biomech 2024; 120: 106370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bey ME, Arampatzis A, Legerlotz K. The effect of a maternity support belt on static stability and posture in pregnant and non-pregnant women. J Biomech 2018; 75: 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhavana G, Kumar K, Anupriya E. Assessment of otolith function using vestibular evoked myogenic potential in women during pregnancy. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2022; 88: 584–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Błaszczyk JW, Opala-Berdzik A, Plewa M. Adaptive changes in spatiotemporal gait characteristics in women during pregnancy. Gait Posture 2016; 43: 160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butler EE, Colón I, Druzin ML, et al. Postural equilibrium during pregnancy: decreased stability with an increased reliance on visual cues. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 195: 1104–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cakmak B, Inanir A, Nacar MC, et al. The effect of maternity support belts on postural balance in pregnancy. PM&R 2014; 6: 624–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cakmak B, Inanir A, Nacar MC. Postural balance in pregnancies complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015; 28: 819–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castillo-Bustamante M, Espinoza I, Briceño O, et al. Vestibular findings on the video Head Impulse Test (vHIT) in pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2023; 15(6): e41059. doi: 10.7759/cureus.41059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catena RD, Campbell N, Werner AL, et al. Anthropometric changes during pregnancy provide little explanation of dynamic balance changes. J Appl Biomech 2019; 35: 232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catena RD, Bailey JP, Campbell N, et al. Correlations between joint kinematics and dynamic balance control during gait in pregnancy. Gait Posture 2020; 80: 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danna-Dos-Santos A, Magalhães AT, Silva BA, et al. Upright balance control strategies during pregnancy. Gait Posture 2018; 66: 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doğan H, Demir Çaltekin M. Plantar sensation, proprioception, and balance levels in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin Biomech 2023; 107: 106016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ficagna N, Brodt GA, Castilhos L, et al. Balance in obese and normal weight pregnant women: a longitudinal study. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2024; 40: 1480–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flores D, Connolly CP, Campbell N, et al. Walking balance on a treadmill changes during pregnancy. Gait Posture 2018; 66: 146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hrvatin I, Rugelj D, Šćepanović D. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain affects balance in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. In: McCrory JL. (ed) PLoS One, Vol. 19. San Francisco, CA, USA: Public Library of Science, 2024, pp.e0287221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inanir A, Cakmak B, Hisim Y, et al. Evaluation of postural equilibrium and fall risk during pregnancy. Gait Posture 2014; 39: 1122–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krkeljas Z. Changes in gait and posture as factors of dynamic stability during walking in pregnancy. Hum Mov Sci 2018; 58: 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCrory JL, Chambers AJ, Daftary A, et al. Dynamic postural stability during advancing pregnancy. J Biomech 2010; 43: 2434–2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCrory J, Chambers A, Daftary A, et al. Dynamic postural stability in pregnant fallers and non-fallers. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2010; 117: 954–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCrory JL, Chambers AJ, Daftary A, et al. Ground reaction forces during gait in pregnant fallers and non-fallers. Gait Posture 2011; 34: 524–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCrory JL, Chambers AJ, Daftary A, et al. Ground reaction forces during stair locomotion in pregnancy. Gait Posture 2013; 38: 684–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCrory JL, Chambers AJ, Daftary A, et al. Ground reaction forces during stair locomotion in pregnant fallers and non-fallers. Clin Biomech 2014; 29: 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreira LS, Elias LA, Gomide AB, et al. A longitudinal assessment of myoelectric activity, postural sway, and low-back pain during pregnancy. Acta Bioeng Biomech 2017; 19(3): 77–83. doi: 10.5277/ABB-00753-2016-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]