Abstract

The medical needs of obesity have been underrecognized, though it has posed long-term and enormous challenges to global health. Correspondingly, clinical services for obesity are still uncommon and in their infancy across health systems. It is meaningful to sort out the implementation of such clinical services involving a multiplicity of factors to identify measures for service development, scaling-up and optimization. This study aims to generate a comprehensive understanding of key variables and factors in the utilization and delivery of clinical services for adult patients with obesity and their dynamic patterns and to explore viable options for improved implementation of such services in health systems. We conducted a scoping review of published articles in the database from the lens of system dynamics through causal loop diagramming. Based on the data obtained from the review, we employed the causal loop diagramming as a tool to capture the variables in the implementation of clinical obesity services and their causal relationships. Twenty-one studies were finally included in the review. Based on the evidence consolidated through the review, we developed a causal loop diagram containing 19 causal variables and 38 causal arrows in single directions centered around the service utilization and delivery in the clinical obesity service. The feedback loops revealed potential activation points to intervene to facilitate the service implementation, such as, promotion of obesity as a disease with medical needs and available clinical services, provision of obesity-specific medical education and training opportunities, and prioritization of obesity-specific procedures in clinical protocols. The possible intervention points identified through the causal loop analysis can facilitate the development, implementation, and optimization of clinical obesity services in health systems.

Keywords: clinical service, service implementation, adult obesity, causal loop diagram, health systems

Introduction

Obesity has been threatening the health of nearly 770 million adults.1 As a complex disease, obesity is characterized as accumulating adiposity due to loss of balance between energy intake and consumption, which exposes individuals to increased risks of morbidity and mortality.2–5 The financial burden of health systems worldwide was estimated to weigh more heavily in the future due to the large population of obesity and overweight.6,7 Although many countries and regions have been taking action to combat this obesity crisis through extensive policies and preventative measures, the growth momentum of obesity has not been slowed down drastically to actualize a zero-increase rate.8–15

Recent pathophysiologic and clinical research highlights the significance and urgency of prioritization of the medical needs of obesity equivalent to other non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, etc. In other words, obesity intrinsically requires medical interventions and services as a disease.5,16 Clinical management of obesity follows a common step-wise intervention pathway with lifestyle interventions as the first-line therapeutic option. A few medications for long-term use and invasive procedures with desirable effectiveness and safety are also available for patients fulfilling the severity criteria of obesity and related complications.17

However, the medical need of obesity is less commonly recognized either among the public or healthcare professionals.18–20 The stigmatization of obesity is a longstanding issue taking time and whole-society efforts to shift, which largely hinders patients with obesity from seeking professional support and services.21,22 Studies have reported either country-wide or geographically imbalanced inadequacy of specific professional manpower for obesity management.23,24 Moreover, although novel anti-obesity drugs with desirable effectiveness in long-term weight management are emerging, their current cost-effectiveness performance may have largely constrained their accessibility to a wider patient population.25–27 Unsurprisingly, the latest global environmental scan of the availability of clinical obesity services confirms the worldwide shortage of such services to formally diagnose, assess and treat this disease condition for patients in need.24 Therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) calls for health systems to improve their readiness to provide a continuum of medical care across the primary, secondary and tertiary care levels and universal health coverage for obesity in its recent initiative on health services response to obesity.28

In relevant studies, significant attention has been paid to specific elements, steps, or supporting resources in the delivery and utilization of clinical obesity services for adults with obesity. However, there is an obvious lack of original research on such services as a whole to investigate their implementation and outcomes.

A causal loop diagram (CLD) is an effective visual representation tool to demonstrate not only the diverse components involved in a complex system but also the causal links and feedback mechanisms between variables.29,30 It is a key step in the system dynamics to construct a conceptual model for the subsequent systems modelling and simulation processes. CLDs, either utilized independently or as part of the system dynamics modelling (SDM) approach, are instrumental in capturing the intricacy of complex issues and pinpointing potential activation points to make systematic changes.31 A CLD commonly comprise variables, unidirectional arrows with either positive or negative polarity, and closed feedback loops.32

Health issues and the healthcare system are intrinsically ever-changing and convoluted, the changes of which are in accordance with the advantages of the methodology of system dynamics.33–37 A cursory search of relevant literature on applying the system dynamics approach could generate various studies on a broad range of topics, covering health system and equity issues,38–41 public health matters,33,42,43 health service delivery,44–48 management of infectious diseases and NCDs,49–53 among others. Obesity is a disease known for its diverse etiologies and mechanisms. The SDM approach has also become a common method of investigating the interrelations of diverse factors leading to obesity, proposing policy and public health interventions to mitigate specific risks, and projecting the potential effectiveness and outcomes of interventions.54–60

Therefore, this study seeks to generate a comprehensive understanding of key variables and factors of the delivery and utilization of clinical services for adult patients with obesity and their dynamic patterns through synthesizing evidence from relevant literature and developing a CLD. The CLD was utilized as a vehicle to construct and demonstrate the comprehensive analysis of the variables and their interlinkages in relation to the implementation of clinical obesity services from a systems perspective. This research will serve as a starting point for further investigation of optimal care models of obesity management for adults with obesity.

Methods

A scoping review of available literature was carried out to define the key variables of the delivery and utilization of clinical obesity services and their interrelations to guide the follow-up construction of the CLD. We followed the key steps of undertaking a scoping study proposed by Arksey and O’Malley.61 The reporting of results complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The findings from the scoping review were then analyzed and visualized through causal loop diagramming to inform the identification of possible implications regarding the implementation of clinical service for adult patients with obesity.

Structuring Research Questions

After deliberating among the main researchers involved in this study, we determined to utilize the following two questions to lead our investigation into the included studies: (1) what are the main variables in the delivery and utilization of clinical obesity services for adult patients; (2) what are the key factors that influence the delivery and utilization; and (3) what is the interplay among these variables?

Identifying and Selecting Relevant Studies

For the purpose of this research, we searched the electronic database PubMed to identify the research articles in any of the following two categories: (1) studies reporting a clinical obesity service for the general adult population; and (2) studies examining any factors that influence service delivery and utilization from any perspective. The combination of two keywords “obesity” and “clinical service” was used in the initial search of relevant peer-reviewed articles published in the recent decade till 31 December 2023. We restricted our search to studies written in English or Chinese with full texts available. The detailed search strategy is presented in the Additional File 1. The references obtained from the initial search were managed by EndNote for the follow-up screening and selection processes.

We explicitly excluded studies that fall into any of the criteria listed below: (1) studies reporting clinical services for a specific group of population, such as children/adolescents, women in pregnancy, and veterans; (2) studies focusing on specific treatment strategies without providing adequate information about the other major components of a clinical service; (3) studies which were not research articles, eg, reviews, conference proceedings, commentary, editorials, and reports; and (4) substandard study quality. In addition, we also conducted hand searches of the reference lists of the key articles identified from our preliminary review of the topic.

In the first round of screening, the duplicate records were deleted. Titles and abstracts of the rest of the studies were then scanned to evaluate their relevance and eligibility, with irrelevance removed. The full texts of the remaining studies from this round were closely examined. Two independent reviewers (YX and XC) were involved in the screening and identification process for joint decisions on the final inclusion.

Examining the Data and Summarizing and Visualizing Through Causal Loop Diagramming

A data extraction form was created to capture the general characteristics, including the country and setting where the study was conducted, the study design and primary data investigated, and the main findings relevant to this research. The causal variables were identified and extracted iteratively. In this process, two steps were taken to ensure the standardization of the labelling of each variable across different studies. We first characterized emerging themes surrounding variables that were identified initially. Subsequently, we adopted the themes to facilitate further identification and final inclusion of variables. We undertook an iterative approach in constructing the causal links between variables based on our close examination of the included studies. The final product of the diagramming reflected the consensus among the research team members on the understanding of the included variables and their inter-relations. The CLD was created with the software Vensim PLE 9.1.1.

Results

General Characteristics of the Included Studies

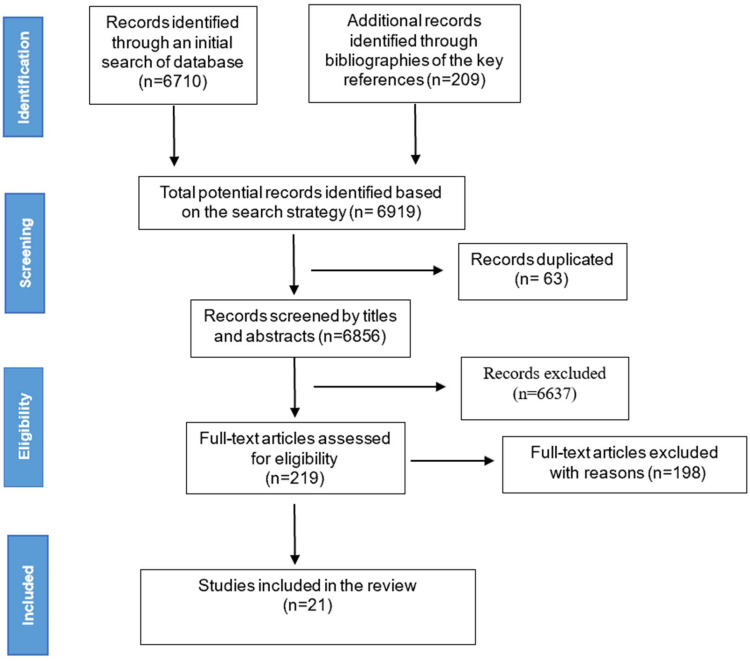

The data identification and selection process are displayed in Figure 1. There were 6710 articles identified through our initial search from databases. In parallel, we conducted a step of hand search of the key references in our preliminary research, which generated 209 articles on relevant topics. After de-duplicating 63 items, we screened the remaining 6856 studies by their titles and abstracts. We then examined the 219 eligible full-text articles for final inclusion. By assessing the relevance and quality of the evidence, we identified 21 studies for the follow-up review procedure.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Table 1 contains the basic characteristics of the included studies. They were performed in five countries: Australia,62–65 Canada,66,67 New Zealand,68,69 the UK,70–72 and the US.73–82 The settings of the clinical obesity services examined in these studies were diverse. Thirteen studies were in the primary care setting,62,66–70,72–75,78,80,82 three studies were in a secondary/tertiary care setting (3,5,11), and the rest were in a general medical setting.64,76,77,79,81 The research designs include three major categories: qualitative approach,62–64,68,69,72,80 quantitative approach,65–67,70,73–79,81 and mixed-methods approach.71,82 Among the seven qualitative studies, interviews were the primary channel to collect primary data from different groups of stakeholders, eg, healthcare providers, clinical administrations, service teams, patients, and the public. The data from the 12 quantitative studies were mainly obtained from electronic medical records and surveys.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

| No | Ref. | Country | Setting | Study Design | Data Investigated | Primary Research Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 62(2019) | Australia | Primary care | Qualitative interviews | Interview input from clinical practitioners | To investigate the factors that impact the clinical practitioners’ execution of a clinical practice guideline for the management of obesity and overweight in Australia |

| 2 | 63(2021) | Australia | Tertiary care | Qualitative interviews | Interview input from clinical leaders and managers working in services that care for patients with obesity | To understand how the clinical leadership perceives the inpatient service provided for people with morbid obesity |

| 3 | 64(2020) | Australia | General medical setting | Qualitative interviews | Interview input from clinical leaders and managers | To understand how the clinical leadership perceives the inpatient service provided for people with morbid obesity, to improve the service |

| 4 | 65(2019) | Australia | Tertiary care, specialist | Quantitative case-control observational study | Medical records | To develop a model based on the existing medical records to enable predictions on the non-completion of a specialist clinical MDT obesity management program for patients with severe obesity |

| 5 | 66(2021) | Canada | Primary care, specialist | Convergent mixed-method randomized control trial | Patient intake questionnaires and electronic medical records | To analyze the patterns of weight loss history and weight loss goals of patients enrolled in a publicly funded specialist obesity clinic through referrals |

| 6 | 67(2022) | Canada | Primary care, specialist | Quantitative retrospective chart review | Patient intake questionnaires and electronic medical records | To explore how weight loss is achieved in patients at a publicly funded, evidence-based clinical obesity management program. the impact of weight-loss history (frequency and amount), the age of overweight onset |

| 7 | 69(2023) | New Zealand | Primary care | Qualitative interviews | Interview input from general practitioners | To identify the factors that inhibit the delivery of clinical obesity services for the local community |

| 8 | 68(2022) | New Zealand | Primary care | Qualitative interviews | Interview input from participants | To identify the factors that inhibit effective weight management of people with obesity who have joined the local general clinical practice |

| 9 | 70(2017) | UK | Primary care, specialist | Quantitative observational cross-sectional study | Electronic medical records | To examine how the patient characteristics and the clinical practitioner’s referring practice affect the attendance and completion of a specialist clinical obesity service |

| 10 | 71(2018) | UK | Secondary care, specialist | Mixed-method design (quantitative retrospective pre-post study, survey, interview) | Electronic medical records, participant survey (general public, clinical practitioners, and service delivery team), interview input from service teams | To conduct an evaluation on the process and outcomes of specialist weight management service completion rates; weight loss at 12 weeks; follow-up weight loss and maintenance |

| 11 | 72(2023) | UK | Primary care, specialist | Qualitative interviews | Residents who are eligible for a tier-2 weight management service | To examine influencers on the signing-up decisions of residents who fulfil the eligibility criteria of a tier-2 weight management service when receiving a referral opportunity |

| 12 | 73(2023) | US | Primary care | Quantitative observational cohort study | Electronic medical records of clinic-, provider-, and patient-level data (participants were adults with a BMI >25 kg/m2 seen in family medicine clinics) | To assess the impact of a novel program that promotes the prioritization of obesity treatment in primary care on the actual provision of weight-prioritized clinic visits |

| 13 | 74(2022) | US | Primary care | Quantitative survey | Primary care providers | To evaluate the amount of weight management services provided and factors on the service provision |

| 14 | 75(2020) | US | Primary care | Quantitative retrospective cohort study | Electronic medical records | To examine the diagnosis rate of obesity, use of pharmacologic and surgical therapies, and weight change of the population of the study (all patients aged ≥18 years who were seen in a primary care clinic within a specific health system) |

| 15 | 76(2019) | US | General medical setting | Quantitative cross-sectional data | 2011 to 2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data on patients with overweight or obesity | To explore the proportion of people who reported seeking clinical obesity services when being advised to do so. |

| 16 | 77(2020) | US | General medical setting | Quantitative cross-sectional data | 2011–2018 NHANES data on respondents who were adults with overweight/obesity and had seen an HCP in the previous 12 months | To examine the association of patient characteristics and their receipt pattern of HCP counselling and or acting on the lifestyle behavioral advice for weight management. |

| 17 | 78(2023) | US | Primary care | Quantitative cohort study | 2013–2019 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Provider Utilization and Payment Data | To analyze the service provision pattern of Intensive Behavior Therapy (IBT) among PCPs for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries |

| 18 | 79(2017) | US | General medical setting | Quantitative cross-sectional analysis | Electronic medical records | To analyze the prevalence of obesity and its comorbidities among patients in a large health system based on real-world data, and to assess the proportion of patients who received a formal diagnosis of obesity and their characteristics |

| 19 | 80(2017) | US | Primary care | Qualitative combined studies (literature review and expert interviews) | Literature and input from PCPs, physical assistants, nurse practitioners, and patient advocates | To study the delivery of clinical obesity service for patients and the challenges of primary care providers |

| 20 | 81(2017) | US | General medical setting | Quantitative cross-sectional survey | Survey data from the US HPs including dieticians, nurses, mental HPs, exercise professionals and pharmacists | To explore the perceived challenges and ways out in the delivery of clinical obesity service, and possible factors |

| 21 | 82(2023) | US | Primary care | Mixed-method (quantitative survey and qualitative interviews) | Primary care providers (PCPs) | To identify the provision pattern of clinical obesity services by the PCPs and the barriers that inhibit the service delivery |

Themes and Variables of the Delivery and Utilization of Clinical Obesity Service

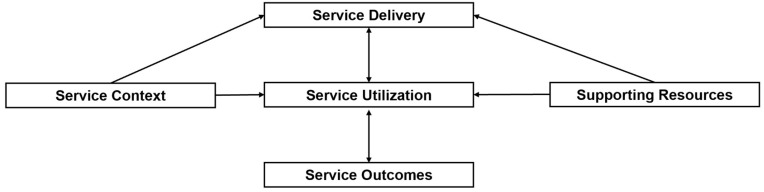

With careful consideration of the study perspectives, aims, and major findings of the included studies, we first identified the following themes that emerge: service context, supporting resources, service delivery, service utilization, and service outcomes. The theme of “service delivery” refers to studies collecting data and viewpoints from healthcare providers and administration on delivering services to patients. The theme of “service utilization” specifies studies collecting data and viewpoints from patients or potential targets of relevant services on the initiation, and utilization of relevant services. The theme of “service outcomes” implies those studies reporting or analyzing the outcomes (eg, weight change, other health benefits obtained) as the main findings.

“Service context” covers studies examining the context for service delivery and utilization, which may include social awareness and culture, organizational culture, etc. “Supporting resources” refers to diverse resources needed to facilitate the delivery or utilization of services. These themes will constitute the subsystems of the causal loop diagram to be established. Their internal relations, as depicted in Figure 2, will direct the construction of CLDs from a bundle of variables. Service utilization and delivery are in reciprocal influences. Both are affected by the service context and supporting resources. Service outcomes are the results of the synergic effect of the other themes, and, in turn, will impact service utilization and delivery.

Figure 2.

Interactions between main themes surrounding the delivery and utilization of clinical obesity services identified from the included studies.

Table 2 demonstrates the variables we identified under each theme from the 21 studies. We standardized the tagging of the variables for easy reference and convenience in the follow-up diagramming. In total, we identified two variables regarding service context, 13 variables regarding service delivery, 11 variables about service utilization, six variables about supporting resources, and two variables about service outcomes.

Table 2.

Themes and Variables Included in the CLD

| No. | Ref. | Service Context(number of Variables: 2) | Service Delivery(Number of Variables: 13) | Service Utilization(Number of Variables: 11) | Supporting Resources(Number of Variables: 6) | Service Outcomes(Number of Variables: 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 62(2019) |

|

|

|||

| 2 | 63(2021) |

|

|

|

||

| 3 | 64(2020) |

|

|

|

||

| 4 | 65(2019) |

|

||||

| 5 | 66(2021) |

|

||||

| 6 | 67(2022) |

|

|

|||

| 7 | 69(2023) |

|

|

|

||

| 8 | 68(2022) |

|

|

|

||

| 9 | 70(2017) |

|

|

|||

| 10 | 71(2018) |

|

|

|

|

|

| 11 | 72(2023) |

|

|

|

||

| 12 | 73(2023) |

|

|

|

||

| 13 | 74(2022) |

|

|

|||

| 14 | 75(2020) |

|

|

|

||

| 15 | 76(2019) |

|

||||

| 16 | 77(2020) |

|

||||

| 17 | 78(2023) |

|

||||

| 18 | 79(2017) |

|

||||

| 19 | 80(2017) |

|

||||

| 20 | 81(2017) |

|

|

|||

| 21 | 82(2023) |

|

|

Abbreviation: MDT, multi-disciplinary team; HER, electronic health records; HCP, healthcare providers.

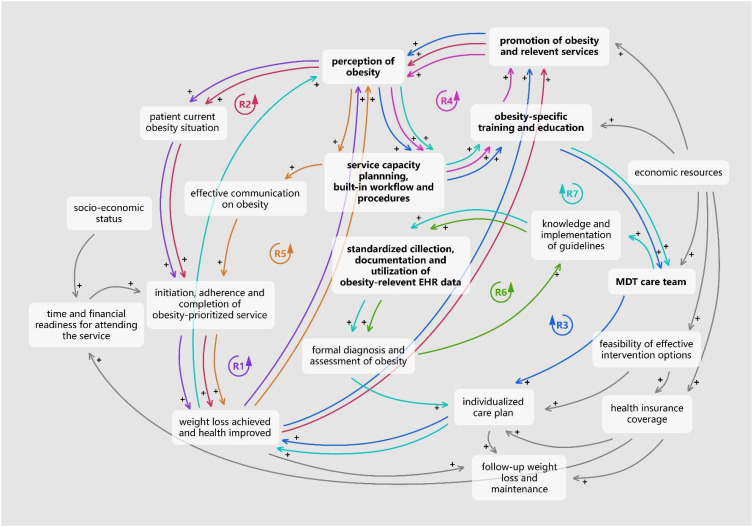

Causal Loop Diagramming

The causal linkages between the variables included were established through an iterative process by referring to the relevant findings from the included studies. The final product was thoroughly discussed to reach a consensus on the included variables and causal links to be included among the research team. The finalized causal loop diagram encompasses 19 variables and 38 causal arrows between these variables, as displayed in Figure 3. Of these variables, 13 are interconnected with many other variables in many loops.

Figure 3.

Causal Loop Diagram on the delivery and utilization of clinical obesity service.

The following provides a detailed account of the loops that emerged as potential intervention points for the improvement of service utilization and delivery of clinical obesity services,

Loops R1 & R2: The reinforcing loop R1 demonstrates that patients’ previous perceptions and awareness of obesity as a disease affect the current severity of obesity and related complications. The enhancement of their perceptions would help to improve their obesity-related condition and understanding of the necessity of weight reduction. Thus, it would prompt these patients to join in an obesity-prioritized service, if they have been suffering from severe obesity and related complications due to their prior low perceptions of obesity as a disease and its health consequences.66,70,72,73,76 Certain weight reduction and health improvement may be observed once they take proactive actions on HCPs’ recommendations after attending and completing obesity-prioritized services. A successful weight loss experience could then reinforce their understanding of the importance of proper recognition of obesity and the necessity of seeking professional help from clinical services. The Loop R2, sharing similar path with Loop R1, indicates that the promotional activities/campaigns on obesity as a disease and relevant clinical services could drive virtuous loop of improved perceptions and awareness of obesity as a disease in the Loop R1.71

Loop R3: The Loop R3 shows that the active promotion of obesity-related knowledge can also lead to the improved recognition of the disease of healthcare providers, hence positively influence their prioritization of obesity in clinical service capacity planning.62–64 Once such a plan is in place, there would be an endogenous demand to improve the professional knowledge and clinical practice skills in managing obesity through strengthening the training and education concerning this specific disease. With elevated professionalism, HCPs involved in an MDT care team will be more likely to play their parts in delivering the clinical obesity services, which includes tailor-making care plans with necessary treatment options for different patients. Consequently, an appropriate individualized treatment strategy is the key step in helping patients to achieve desirable weight loss outcomes and other health benefits.67,71,73,75,81 Successful cases of clinical obesity management would help to build the real-world evidence base for promoting obesity and relevant services, resulting in a reinforcing loop.

Loop R4: Healthcare providers involved in clinical obesity services need obesity-specific training and continual education opportunities to equip them with up-to-date evidence-based knowledge and clinical practices regarding obesity management.62–64,70,71,73,75 In this way, HCPs will be more likely to recognize obesity as a disease with medical necessity, hence encouraging them to make more efforts in the health promotion of obesity and relevant services. With elevated public awareness of obesity as a disease, an increase in the demand for clinical obesity services may be observed subsequently. The administrations of clinical institutions will be more likely to be incentivized to plan capacity for obesity-prioritized services and consider mandating relevant services in the workflow. In turn, these service provision requirements may create larger needs for obesity-specific training and continual education opportunities for HCPs.

Loop R5: The prioritization of obesity in the existing workflow and medical procedures will enable HCPs to have time and mandate to have obesity-relevant communications with patients concerned in a more proactively way.62,64,73–75,80,82 Such communications will influence patients’ awareness and willingness to take an obesity-prioritized assessment and treatment.62,79,82 Actions of patients are vital to the health outcomes they could achieve from clinical obesity services. As obesity is a relapsing chronic disease requiring long-term management, positive weight loss experiences may further raise their awareness towards the disease. Consecutively, the increased perceptions of the disease would generate more demands for clinical obesity services from patients, bringing about a reinforcing loop of increased supply.

Loop R6: The standardized and high-quality obesity-relevant EHR data can help to generate comprehensive evidence for HCPs to make a diagnosis of obesity for patients evidence.71,73,75,79 In this way, the relevant clinical practice guidelines to deliver services to the patients. In turn, high-quality obesity-relevant data would be collected and documented by following the guidelines closely.

Loop R7: The involvement of an MDT plays a pivotal role in implementing obesity-related clinical practice guidelines.63,80 With good knowledge of the guidelines, the healthcare delivery team would be able to collect and document standardized quality obesity-relevant data to inform the formal diagnosis, and follow-up individualized care plan making. Such endeavors may directly influence the weight loss outcomes of patients attending the service. In turn, health benefits that patients achieve from such a service may impact their perceptions of obesity and relevant services. On the other hand, this would then link back to the Loop R1 to influence the improvement in service delivery alongside the enhanced perceptions of obesity of HCPs.

In addition to these variables forming various loops, adequate financing and funding support is inevitably a key player in delivering clinical obesity services by supporting the service promotion and establishment of MDTs, and ensuring accessibility of necessary and effective treatment strategies for patients with obesity.68,69,72,75,81

Discussions

The current research is aimed at constructing an analytical overview of the key variables and drivers influencing the delivery and utilization of clinical obesity services for adult patients with obesity by synthesizing original studies pertinent to this topic through the lens of system dynamics. The CLD was created based on the scoping review of the literature. It not only demonstrates the multitude of variables surrounding the implementation of a clinical obesity service but also provides insights into the possible complex interrelationships among them. This system dynamics approach has been utilized in investigating different determinants of obesity occurrence and prevalence, and the development and evaluation of various interventions. However, to our knowledge, our study is the first to use CLD to study the implementation issue about clinical services for adult patients with obesity.

Another value of this research is that the feedback loops in the resultant diagram reveal areas with great potentials for bringing systematic changes to improve the delivery of clinical services for the adult population with obesity. The diagram suggests that promoting the perception of obesity as a disease and the recognition of its medical needs among the public and healthcare professionals could bring leverage effects to the delivery and utilization of clinical obesity services. Also, as the pathophysiology research of obesity achieved great advancement only in recent years, it is necessary to equip healthcare providers and other support staff with updated evidence-based knowledge and practices about obesity through formal education and continuing training opportunities. Another possible leverage point is to build obesity-relevant or specific procedures into the clinical protocols to conduct necessary conversations, assessments and diagnoses of obesity. The effective implementation of such protocols will be facilitated by high-quality obesity relevant electronic health records collected and documented with a reasonable degree of standardization. Moreover, an integrated multidisciplinary team service is the crux of managing such a complex disease. These potential intervention points on resource mobilization and service innovation, together with the key components of clinical obesity services identified in our previous study, could provide guidance on the development, implementation, and optimization of clinical care for adult obesity in health systems.83

There are several limitations of this study worth noting. Firstly, the final CLD drawn out here is a preliminary CLD purely based on the published articles with a defined study focus. Presumably, this literature-based source of information may restrict our conceptualization of the core research question to capture all the underlying dynamics. Further direct dialogues with stakeholders are much in need of first-hand information to validate and refine the current CLD, and for strengthening our understanding of the development and optimization of clinical obesity services. Secondly, the healthcare settings of the clinical obesity services reported in the included studies are highly heterogeneous, ranging from community to tertiary care. And all of them are from the health systems in developed countries. This complicated mix of contextual factors may compound the generalizability of our findings. Further refined criteria of care levels for inclusion may improve the findings to be more targeted. This approach would only be viable if there are adequate original studies investigating factors influencing the implementation of clinical obesity services in similar settings.

Conclusions

This research probed into variables in and factors impacting the delivery and utilization of clinical services for adult patients with obesity from a scoping review of the literature with the aid of a qualitative system dynamics modelling approach. The resultant CLD contains 19 variables in five themes and 38 causal links between them. By analyzing the dynamics of the clinical obesity services revealed in this CLD, we identified possible activation points to improve and optimize the utilization and delivery, including enhancement of awareness and perceptions of obesity as a disease of both the public and healthcare providers, active promotion of obesity as a disease and relevant clinical services, strengthening of obesity-specific training and education, prioritization of clinical obesity services in the current clinical procedures, improvement of the EHR data system to support the assessment, diagnosis, treatment and long-term management of obesity, involvement of a qualified MDT, and so forth. It is vital for future studies to solicit more first-hand information from stakeholders with considerations of broader contextual varieties to generate further evidence base for these observations. Where possible, experimental or quantitative modelling research could be conducted to evaluate or predict the impact of potential leverage points on the systematic enhancement of clinical obesity services in various health systems.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.World Obesity Federation. World obesity atlas 2024. [Internet]. London (UK): WOF; 2024. Available from: https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/?cat=22. Accessed May 20, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blüher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):288–298. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popkin BM, Du S, Green WD, et al. Individuals with obesity and COVID‐19: a global perspective on the epidemiology and biological relationships. Obesity Rev. 2020;21(11). doi: 10.1111/obr.13128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbade EB. The relationships between obesity-increasing risk factors for public health, environmental impacts, and health expenditures worldwide. MEQ. 2018;29(1):131–147. doi: 10.1108/MEQ-08-2016-0058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):254–266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1514009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suehs BT, Kamble P, Huang J, et al. Association of obesity with healthcare utilization and costs in a medicare population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(12):2173–2180. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1361915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okunogbe A, Nugent R, Spencer G, Powis J, Ralston J, Wilding J. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for 161 countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(9):e009773. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ananthapavan J, Sacks G, Brown V, et al. Priority-setting for obesity prevention—the assessing cost-effectiveness of obesity prevention policies in Australia (ACE-Obesity Policy) study. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theis DRZ, White M. Is obesity policy in England fit for purpose? Analysis of government strategies and policies, 1992–2020. Milbank Q. 2021;99(1):126–170. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfenden L, Ezzati M, Larijani B, Dietz W. The challenge for global health systems in preventing and managing obesity. Obesity Rev. 2019;20(S2):185–193. doi: 10.1111/obr.12872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xue Y, Ruan Z, Ung COL, Lai Y, Hu H. Policy analysis of system responses to addressing and reversing the obesity trend in China: a documentary research. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1198. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15890-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koliaki C, Dalamaga M, Liatis S. Update on the obesity epidemic: after the sudden rise, is the upward trajectory beginning to flatten? Curr Obes Rep. 2023;12(4):514–527. doi: 10.1007/s13679-023-00527-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyn R, Heath E, Dubhashi J. Global implementation of obesity prevention policies: a review of progress, politics, and the path forward. Curr Obes Rep. 2019;8(4):504–516. doi: 10.1007/s13679-019-00358-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esdaile E, Thow AM, Gill T, et al. National policies to prevent obesity in early childhood: using policy mapping to compare policy lessons for Australia with six developed countries. Obesity Rev. 2019;20(11):1542–1556. doi: 10.1111/obr.12925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kersh R. Of nannies and nudges: the current state of U.S. obesity policymaking. Public Health. 2015;129(8):1083–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jepsen CH, Bowman-Busato J, Allvin T, et al. Achieving consensus on the language of obesity: a modified delphi study. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;62:102061. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lingvay I, Cohen RV, Roux CWL, Sumithran P. Obesity in adults. Lancet. 2024;404(10456):972–987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01210-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritten A, LaManna J. Unmet needs in obesity management: from guidelines to clinic. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29(S1):S30–S42. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciciurkaite G, Moloney ME, Brown RL. The incomplete medicalization of obesity: physician office visits, diagnoses, and treatments, 1996-2014. Public Health Rep. 2019;134(2):141–149. doi: 10.1177/0033354918813102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujioka K, Harris SR. Barriers and solutions for prescribing obesity pharmacotherapy. Endocrinol Metab Clinics North Am. 2020;49(2):303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2020.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearl RL. Weight bias and stigma: public health implications and structural solutions. Soc Iss Policy Rev. 2018;12(1):146–182. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nutter S, Eggerichs LA, Nagpal TS, et al. Changing the global obesity narrative to recognize and reduce weight stigma: a position statement from the WORLD OBESITY FEDeration. Obesity Rev. 2024;25(1):e13642. doi: 10.1111/obr.13642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gudzune KA, Johnson VR, Bramante CT, Stanford FC. Geographic availability of physicians certified by the American board of obesity medicine relative to obesity prevalence. Obesity. 2019;27(12):1958–1966. doi: 10.1002/oby.22628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson Leach R, Powis J, Baur LA, et al. Clinical care for obesity: a preliminary survey of sixty‐eight countries. Clin Obes. 2020;10(2). doi: 10.1111/cob.12357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakhtoura M, Haber R, Ghezzawi M, Rhayem C, Tcheroyan R, Mantzoros CS. Pharmacotherapy of obesity: an update on the available medications and drugs under investigation. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;58:101882. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Q, Wang Y, Hao Q, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2024;403(10434):e21–e31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00351-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue Y, Zou H, Ruan Z, et al. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of anti-obesity drugs for chronic weight management: a systematic review of literature. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1254398. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1254398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Health service delivery framework for prevention and management of obesity. WHO; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073234. Accessed August 16, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavana RY, Maani KE. A methodological framework for integrating systems thinking and system dynamics.

- 30.Baugh Littlejohns L, Baum F, Lawless A, Freeman T. The value of a causal loop diagram in exploring the complex interplay of factors that influence health promotion in a multisectoral health system in Australia. Health Res Policy Sys. 2018;16(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0394-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baugh Littlejohns L, Hill C, Neudorf C. Diverse approaches to creating and using causal loop diagrams in public health research: recommendations from a scoping review. Public Health Rev. 2021;42:1604352. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2021.1604352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sterman JD. System dynamics modeling: tools for learning in a complex world. California Manage Rev. 2001;43(4):8–25. doi: 10.2307/41166098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George A, Badrinath P, Lacey P, et al. Use of system dynamics modelling for evidence-based decision making in public health practice. Systems. 2023;11(5):247. doi: 10.3390/systems11050247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rees D, Orr-Walker DB, Auckland S. System dynamics modelling as a tool in healthcare planning. Presented at the 11th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society. Christchurch, NZ. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong QN, Bangpan M, Stansfield C, et al. Using systems perspectives in evidence synthesis: a methodological mapping review. Res Synth Meth. 2022;13(6):667–680. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carey G, Malbon E, Carey N, Joyce A, Crammond B, Carey A. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: a systematic review of the field. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009002. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang AY, Ogbuoji O, Atun R, Verguet S. Dynamic modeling approaches to characterize the functioning of health systems: a systematic review of the literature. Soc sci med. 2017;194:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li M, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Yu W, Nong X, Zhang L. Factors influencing two-way referral between hospitals and the community in China: a system dynamics simulation model. Simulation. 2018;94(9):765–782. doi: 10.1177/0037549717741349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan JS, Graber-Naidich A. Small system dynamics model for alleviating the general practitioners rural care gap in Ontario, Canada. Socio-Econ Plann Sci. 2019;66:10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.seps.2018.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Royston G, Dost A, Townshend J, Turner H. Using system dynamics to help develop and implement policies and programmes in health care in England. Syst Dyn Rev. 1999;15(3):293–313. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu W, Li M, Ge Y, et al. Transformation of potential medical demand in China: a system dynamics simulation model. J biomed informat. 2015;57:399–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2015.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cilenti D, Issel M, Wells R, Link S, Lich KH. System dynamics approaches and collective action for community health: an integrative review. American J of Comm Psychol. 2019;63(3–4):527–545. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tobias MI, Cavana RY, Bloomfield A. Application of a system dynamics model to inform investment in smoking cessation services in New Zealand. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(7):1274–1281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aminullah E, Erman E. Policy innovation and emergence of innovative health technology: the system dynamics modelling of early COVID-19 handling in Indonesia. Technol Soc. 2021;66:101682. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conroy S, Brailsford S, Burton C, et al. Identifying models of care to improve outcomes for older people with urgent care needs: a mixed methods approach to develop a system dynamics model. Health Soc Care Deliv Res. 2023:1–183. doi: 10.3310/NLCT5104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iorfino F, Occhipinti JA, Skinner A, et al. The impact of technology-enabled care coordination in a complex mental health system: a local system dynamics model. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(6):e25331. doi: 10.2196/25331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Del Vecchio P, Mele G, Villani M. System dynamics for e-Health: an experimental analysis of digital transformation scenarios in health care. IEEE Trans Eng Manage. 2023;70(8):2920–2930. doi: 10.1109/TEM.2022.3194720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kasiri N, Sharda R, Asamoah DA. Evaluating electronic health record systems: a system dynamics simulation. Simulation. 2012;88(6):639–648. doi: 10.1177/0037549711416244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weeks MR, Lounsbury DW, Li J, et al. Simulating system dynamics of the HIV care continuum to achieve treatment as prevention. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0230568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li M, Yu W, Tian W, et al. System dynamics modeling of public health services provided by China CDC to control infectious and endemic diseases in China. IDR. 2019;Volume 12:613–625. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S185177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kok S, Rutherford AR, Gustafson R; on behalf of the Vancouver HIV Testing Program Modelling Group, et al. Optimizing an HIV testing program using a system dynamics model of the continuum of care. Health Care Manag Sci. 2015;18(3):334–362. doi: 10.1007/s10729-014-9312-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peng CQ, Lawson KD, Heffernan M, et al. Gazing through time and beyond the health sector: insights from a system dynamics model of cardiovascular disease in Australia. PLoS One. 2021;16(9):e0257760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valaei Sharif S, Habibi Moshfegh P, Morshedi MA, Kashani H. Modeling the impact of mitigation policies in a pandemic: a system dynamics approach. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022;82:103327. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waterlander WE, Singh A, Altenburg T, et al. Understanding obesity‐related behaviors in youth from a systems dynamics perspective: the use of causal loop diagrams. Obesity Rev. 2021;22(7):e13185. doi: 10.1111/obr.13185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Langellier BA, Bilal U, Montes F, Meisel JD, de O Cardoso L, Hammond RA. Complex systems approaches to diet: a systematic review. Am J Preventive Med. 2019;57(2):273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stankov I, Henson RM, Headen I, Purtle J, Langellier BA. Use of qualitative systems mapping and causal loop diagrams to understand food environments, diet and obesity: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e066875. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mui Y, Ballard E, Lopatin E, Thornton RLJ, Pollack Porter KM, Gittelsohn J. A community-based system dynamics approach suggests solutions for improving healthy food access in a low-income urban environment. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0216985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aguiar A, Önal F, Hendricks G, et al. Understanding the dynamics emerging from the interplay among poor mental wellbeing, energy balance‐related behaviors, and obesity prevalence in adolescents: a simulation‐based study. Obesity Rev. 2023;24(S2):e13628. doi: 10.1111/obr.13628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meisel JD, Esguerra V, Giraldo JK, et al. Understanding the dynamics of the obesity transition associated with physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and consumption of ultra-processed foods in Colombia. Preventive Med. 2023;177:107720. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guariguata L, Garcia L, Sobers N, et al. Exploring ways to respond to rising obesity and diabetes in the Caribbean using a system dynamics model. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2(5):e0000436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mazza D, McCarthy E, Carey M, Turner L, Harris M. “90% of the time, it’s not just weight”: general practitioner and practice staff perspectives regarding the barriers and enablers to obesity guideline implementation. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2019;13(4):398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2019.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qvist A, Pazsa F, Hitch D. Perceptions of clinical leaders and managers of inpatients with obesity in an Australian public health service. J Hosp Manag Health Policy. 2021;5:15. doi: 10.21037/jhmhp-20-98 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hitch D, Pazsa F, Qvist A. Clinical leadership and management perceptions of inpatients with obesity: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. IJERPH. 2020;17(21):8123. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Atlantis E, Lin F, Anandabaskaran S, Fahey P, Kormas N. A predictive model for non-completion of an intensive specialist obesity service in a public hospital: a case-control study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):748. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4531-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuk JL, Dehlehhosseinzadeh M, Kamran E, Wharton S. An analysis of weight loss efforts and expectations in a Canadian cohort: a retrospective medical chart review. Clin Obes. 2021;11(3). doi: 10.1111/cob.12449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuk JL, Kamran E, Wharton S. Association between weight‐loss history and weight loss achieved in clinical obesity management: retrospective chart review. Obesity. 2022;30(10):2071–2078. doi: 10.1002/oby.23530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Norman K, Burrows L, Chepulis L, Lawrenson R. “Sometimes choices are not made, because we have ‘a’ choice, they’re made because they are ‘the’ choice”: barriers to weight management for clients in rural general practice. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):268. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01874-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Norman K, Burrows L, Chepulis L, Lawrenson R. Barriers to obesity health care in general practice from rural Waikato GP perspectives: a qualitative study. Australian J Rural Health. 2023;31(4):758–769. doi: 10.1111/ajr.13004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blane DN, McLoone P, Morrison D, Macdonald S, O’Donnell CA. Patient and practice characteristics predicting attendance and completion at a specialist weight management service in the UK: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018286. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ells L, Watson P, Carlebach S, et al. A mixed method evaluation of adult tier 2 lifestyle weight management service provision across a county in Northern England: evaluating adult weight management. Clin Obes. 2018;8(3):191–202. doi: 10.1111/cob.12250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gericke C, Rippy S, D’Lima D. Anticipated barriers and enablers to signing up for a weight management program after receiving an opportunistic referral from a general practitioner. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1226912. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1226912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wild J, Kaizer A, Willems E, Kramer ES, Perreault L. Prelude to PATHWEIGH: pragmatic weight management in primary care. Family Practice. 2023;40(2):322–329. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmac092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suresh K, Willems E, Williams J, et al. An assessment of weight loss management in health system primary care practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2023;36(1):51–65. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2022.220224R1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lumsden RH, Pagidipati NJ, Phelan MP, Chiswell K, Peterson ED. Prevalence and management of adult obesity in a large U.S. academic health system. Am J Preventive Med. 2020;58(6):817–824. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.De Heer HD, Kinslow B, Lane T, Tuckman R, Warren M. Only 1 in 10 patients told to lose weight seek help from a health professional: a nationally representative sample. Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(7):1049–1052. doi: 10.1177/0890117119839904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Greaney ML, Cohen SA, Xu F, Ward-Ritacco CL, Riebe D. Healthcare provider counselling for weight management behaviours among adults with overweight or obesity: a cross-sectional analysis of national health and nutrition examination survey, 2011–2018. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e039295. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ozoor M, Gritz M, Dolor RJ, Holtrop JS, Luo Z. Primary care provider uptake of intensive behavioral therapy for obesity in medicare patients, 2013–2019. PLoS One. 2023;18(3):e0266217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pantalone KM, Hobbs TM, Chagin KM, et al. Prevalence and recognition of obesity and its associated comorbidities: cross-sectional analysis of electronic health record data from a large US integrated health system. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e017583. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hayes S, Wolf C, Labbé S, Peterson E, Murray S. Primary health care providers’ roles and responsibilities: a qualitative exploration of “who does what” in the treatment and management of persons affected by obesity. J Healthc Commun. 2017;10(1):47–54. doi: 10.1080/17538068.2016.1270874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Doshi RS, Bleich SN, Gudzune KA. Health professionals’ perceptions of insurance coverage for weight loss services: insurance and weight loss. Obes Sci Pract. 2017;3(4):384–389. doi: 10.1002/osp4.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oshman L, Othman A, Furst W, et al. Primary care providers’ perceived barriers to obesity treatment and opportunities for improvement: a mixed methods study. PLoS One. 2023;18(4):e0284474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0284474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xue Y, Song MH, Chen XW, et al. Consolidating international care models and clinical services for adult obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2025;14(1):26. doi: 10.1007/s13679-025-00621-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]