Abstract

Abstract

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs) are a rare subset of pancreatic cancers often diagnosed late and characterized by complex behaviors. Recent evidence suggests the gut microbiome (GM) significantly influences various diseases by modulating the immune system. This study utilized a Mendelian randomization (MR) approach to investigate the causal relationship between GM and pNETs, using single nucleotide polymorphism data as instrumental variables. Two-sample MR analysis identified significant correlations between GM and immune cell types. The study found eight specific GMs affecting pNETs risk: the family Sutterellaceae (OR: 1.52, 95% CI 1.10–2.10, p = 0.01), the genus Paraprevotella (OR: 1.34, 95% CI 1.05–1.72, p = 0.02), the species Paraprevotella unclassified (OR: 1.40, 95% CI 1.08–1.81, p = 0.01), and the species Ruminococcus torques (OR: 1.45, 95% CI 1.12–1.89, p = 0.01) increased risk, while the class Gammaproteobacteria (OR: 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.98, p = 0.04), the family Acidaminococcaceae (OR: 0.70, 95% CI 0.52–0.94, p = 0.02), the species Paraprevotella xylaniphila (OR: 0.72, 95% CI 0.54–0.96, p = 0.03), and the species Bacteroides finegoldii (OR: 0.68, 95% CI 0.51–0.91, p = 0.01) decreased it. Mediation analysis indicated the species Ruminococcus torques mediated the effect of CD25 on CD45RA+ CD4 non-regulatory T cells on pNETs, accounting for 3.6% of the total effect. This study provides evidence suggestive of a potential causal role of specific GM compositions in pNETs progression and their mediation through immune cell signatures. However, mechanistic studies are required to further validate this relationship.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-02761-3.

Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs), also known as"islet cell tumors,"are neuroendocrine tumors arising from pancreatic endocrine cells located in the islets of Langerhans. They are divided into functional tumors and non-functional tumors [1]. Functional pNETs produce excess hormones (e.g., insulin, gastrin), causing distinct symptoms like hypoglycemia or ulcers, leading to earlier diagnosis. Non-functional pNETs, which account for most cases, lack hormone-related symptoms and are often detected later due to mass effects (e.g., pain, jaundice) or metastasis, resulting in poorer prognosis. Despite advances in therapeutic strategies, including surgery, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy, and targeted therapies, the prognosis for NET patients remains variable, with a 5-year survival rate ranging widely depending on the tumor's stage and functional status [2, 3].

There has been growing research, increasingly highlighting the vital importance of the gut microbiome (GM) to human health and disease [4]. The GM is the"second genome"of the human body, consisting of trillions of microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract. They direct metabolic, endocrine, immune, and inflammatory processes [5, 6]. The longstanding observation, supported by epidemiological and genetic evidence is that GM dysbiosis is associated with the development of a multitude of different diseases, not only cardiovascular diseases but also inflammatory bowel diseases and cancer [7, 8]. While Mendelian randomization (MR) findings are consistent with this association, experimental research is needed to elucidate underlying mechanisms. The information gained from recent studies provide evidence supporting that the GM's composition and function might also affect pNETs development and progression [9–11].

Furthermore, the interaction between the GM and the immune system is particularly relevant in the context of cancer. The GM can modulate immune responses by influencing the local environment of the intestinal mucosa and intestinal-associated lymphoid tissue, thereby impacting systemic immunity [12–14]. Recent reviews emphasize that GM-derived metabolites (e.g., Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), polyamines) and microbial antigens directly shape antitumor immunity by regulating dendritic cell maturation, T cell differentiation, and macrophage polarization [15, 16]. For instance, SCFAs enhance Treg suppressive function while inhibiting pro-inflammatory Th17 responses, a balance critical for preventing both autoimmunity and tumor immune evasion [17]. This immune modulation is crucial for the body's ability to recognize and eliminate malignant cells through immune surveillance. However, tumors, including pNETs, can develop mechanisms to evade this immune surveillance, leading to unchecked growth and metastasis [18, 19].

In epidemiological research, MR is a powerful tool to infer causal relationships between risk factors (exposures) and disease outcomes. MR utilizes genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to mitigate confounding and reverse causation, providing a more robust assessment of causality [20, 21]. Previous research has employed MR to elucidate the role of GM in various diseases, but its application to pNETs remains underexplored [22, 23].

This study aims to investigate the causal role of GM in the progression of pNETs and to determine whether immune cell signatures mediate this effect. We performed a two-sample MR analysis using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data as IVs for GM composition and immune cell signatures [24]. We aimed to evaluate the causal relationships and mediation effects, enhancing our understanding of the underlying mechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets for pNETs.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study used a systematic MR approach to explore the causal relationship between GM and pNETs and to determine if immune cell signatures mediate this relationship. We performed MR analyses on 412 types of GM to identify those associated with pNETs, validated these findings with reverse MR analysis, and examined 731 immune cell types to find significant correlations. Finally, we assessed the proportion of the GM's effect on pNETs mediated by immune cells, using non-overlapping datasets for exposures and outcomes to ensure robust results. The study design is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overall study design flowchart

Data sources

Pooled statistics for 412 GMs were collected from MiBioGen (https://mibiogen.gcc.rug.nl/), which included 207 taxa and 205 pathways (Ebi-a-GCST90027446 to Ebi-a-GCST90027857) [21]. pNETs data were obtained from the FinnGen_R9_C3_PANCREAS_NEUROENDOCRINE_EXALLC cohort, comprising 122 pNETs cases and 287,137 controls [22]. Immune cell datasets (731 traits, Ebi-a-GCST90001391 to Ebi-a-GCST90002121) were sourced from the Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) catalog (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/) [23].

Genetic IVs selection

The significance level was set at p < 1 × 10−5 to select the GM and immune cell trait IVs. Afterwards, the linkage disequilibrium in the selected IVs with R2 threshold of < 0.001 in the distance of ≥ 10,000 kilobases was clumped. For the inverse MR analysis, the significant threshold was determined as a stricter value (p < 5 × 10−8). The F-statistic was calculated for each IV, and SNPs with F > 10 were retained for subsequent studies [25].

MR analysis

All statistical analyses were implemented with R 4.2.3 and Rstudio (2023.12.1 + 402) using the TwoSampleMR package (version 0.6.0). The inverse variance weighted (IVW) method served as the primary analytical tool, supplemented by MR Egger, weighted median, simple mode, and weighted mode to ensure comprehensive results [25]. To address limitations of conventional MR approaches, we further applied Bayesian Weighting Mendelian Randomization (BWMR), which integrates prior distributions for genetic effects and probabilistically models horizontal pleiotropy, improving robustness in sparse datasets. BWMR-generated posterior credible intervals complemented frequentist confidence intervals, enhancing causal inference reliability. Bayesian weighting and robust adjustments minimized measurement error and horizontal pleiotropy. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied to IVW and BWMR results [26].

Sensitivity analysis in MR

Cochran's Q statistic based on IVW and MR Egger methods was utilized to assess the degree of heterogeneity. We took advantage of the MR-Egger intercept test and MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier method (MR-PRESSO) to detect the pleiotropy with the"MRPRESSO"software package (version 1.0) [26]. Furthermore, MR-PRESSO was also applied to correct horizontal pleiotropy via outlier removal and assess significant differences before and after outlier correction. The indirect effect of GM on pNETs risk via potential mediator was evaluated using the"product of coefficients"method. The corresponding forest plot and scatter plot were constructed based on the MR results, and the leave-one-out analysis was performed to evaluate whether the MR estimate was driven or biased by a single SNP [27].

Results

MR analysis of GM on pNETs risk

MR analyses identified eight GM taxa significantly associated with pNETs risk among 412 microbial taxa. The results are shown in Fig. 2, risk-enhancing taxa included the family Sutterellaceae (OR = 3.332, 95% CI 1.045–10.625, p = 0.042), the class Paraprevotella (OR = 3.629, 95% CI 1.682–7.830, p = 0.001), the species Paraprevotella unclassified (OR = 3.251, 95% CI 1.020–10.362, p = 0.046), and the species Ruminococcus torques (OR = 3.661, 95% CI 1.460–9.178, p = 0.006), whereas the class Gammaproteobacteria (OR = 0.186, 95% CI 0.038–0.917, p = 0.039), the family Acidaminococcaceae (OR = 0.432, 95% CI 0.202–0.923, p = 0.030), the species Paraprevotella xylaniphila (OR = 0.394, 95% CI 0.213–0.728, p = 0.003), and the species Bacteroides finegoldii (OR = 0.646, 95% CI 0.421–0.992, p = 0.006) were protective. Among 205 microbial pathways, anhydromuropeptides recycling pathway increased pNETs risk (OR = 3.708, 95% CI 1.211–11.355, p = 0.022), while seven pathways showed protective effects (p < 0.05, Table S1). BWMR validation (Fig. 3) confirmed four taxa and five pathways as robust predictors (Table S2), reinforcing the primary IVW findings, with sensitivity analyses (Cochran's Q, MR-Egger intercept) indicating no heterogeneity or pleiotropy (p > 0.05, Table S3). The reverse MR analysis revealed no significant findings (Table S4), enabling further mediation analysis.

Fig. 2.

MR analysis results and heterogeneity or pleiotropy test. 16 GMs that significantly influence pNETs were identified using the IVW method. Note: GM, gut microbiome; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio; C, class; F, family; G, genus; S, species

Fig. 3.

The BWMR method, in combination with the IVW method, screened 9 GMs that significantly affected pNETs. Note: GM, gut microbiome; OR, odds ratio; F, family; G, genus; S, species

GM-immune cell interactions

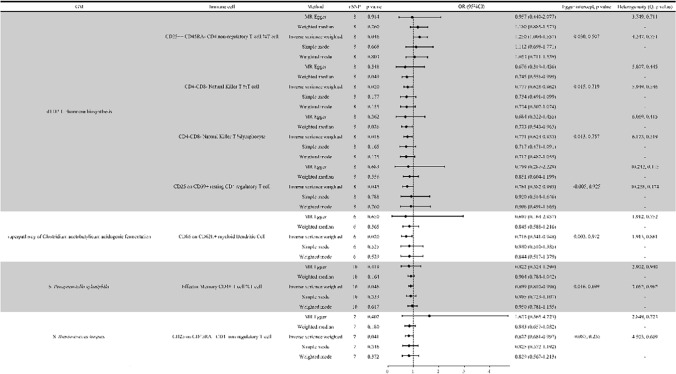

MR analyses revealed significant associations between the nine GM taxa/pathways and immune cells. For example, the dTDP-L-rhamnose biosynthesis pathway positively correlated with CD25++ CD45RA- CD4 non-regulatory T cells (OR = 1.250, 95% CI 1.004–1.557, p = 0.046) but negatively correlated with CD4-CD8- Natural Killer T cells (OR = 0.777, 95% CI 0.628–0.962, p = 0.020); lymphocytes (OR = 0.771, 95% CI 0.624–0.953, p = 0.016). The species Ruminococcus torques exhibited a negative correlation with CD25 on CD45RA+CD4 non-regulatory T cells (OR = 0.822, 95% CI 0.681–0.992, p = 0.041). No significant heterogeneity or pleiotropy was detected (p > 0.05, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Results of MR analysis of immune cells by GM. Note: GM, gut microbiome; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio; S, species

Immune cell associations with pNETs risk

Seven immune cell traits showed causal effects on pNETs risk. CD25 on CD45RA + CD4 non-regulatory T cells demonstrated protective effects (IVW: OR = 0.788, 95% CI 0.643–0.967, p = 0.023; MR Egger: OR = 0.741, 95% CI 0.579–0.949, p = 0.028), while six other immune subtypes were associated with increased risk (Table S5). BWMR validation confirmed these findings (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Results of MR analysis of the effect of immune cells on pNETs. Note: SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio

Mediation effect of GM on pNETs

CD25 on CD45RA+CD4 non-regulatory T cells mediated 3.6% of the total effect of the species Ruminococcus torques on pNETs (mediation effect = 0.046, calculated by multiplying the path coefficients (0.196 (β1) × 0.238 (β2)), Fig. 6). This pathway was supported by the negative correlation between the species Ruminococcus torques and CD25 levels (OR = 0.822) and the positive correlation between CD25+ non-Tregs and pNETs (OR = 3.661).

Fig. 6.

Mediation effect relationship of known GM and immune cells on pNETs. Note: S, species

Discussion

This study aimed to elucidate the causal relationships between specific GM taxa and pathways with pNETs and to explore potential mediation by immune cell signatures. A two-sample MR analysis provided robust evidence supporting these associations, with bidirectional sensitivity analyses minimizing potential confounding. Notably, reverse MR analyses testing pNETs as exposures showed no significant associations, consistent with a hypothesized unidirectional causal direction (GM/pathways → pNETs). However, instrumental variables for pNETs in reverse analyses explained substantially less variance compared to those for GM taxa/pathways in forward analyses, and power calculations indicated limited sensitivity to detect modest effect sizes. While these results support a causal role of GM features in pNETs pathogenesis, residual uncertainty persists due to potential weak instrument bias in reverse analyses. Future replication in larger cohorts with stronger genetic instruments is warranted to confirm these directional effects and clarify immune-mediated mechanisms [20, 21, 28].

The GM influences cancer progression through a complex interplay of microbial metabolites and immune modulation. SCFAs, such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate-produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber-exert pleiotropic effects on immune homeostasis and tumorigenesis. Butyrate, for instance, enhances regulatory T cell differentiation via histone deacetylase inhibition, promoting anti-inflammatory responses that may suppress tumorigenesis in certain contexts [29]. Conversely, dysbiosis-induced depletion of SCFAs could impair Treg-mediated immune tolerance, unleashing pro-inflammatory effector T cells that drive chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis [30]. Our findings align with this paradigm: the species Ruminococcus torques, a mucin-degrading species associated with reduced SCFAs production [31], was linked to diminished CD25 expression on CD45RA + CD4 + non-Tregs. This suggests that the species Ruminococcus torques may disrupt IL-2-dependent T cell activation while simultaneously altering metabolite-driven immune regulation. Furthermore, microbial metabolites like polyamines and secondary bile acids can modulate macrophage polarization and dendritic cell maturation, shaping antitumor immunity or fostering immune evasion [32]. For example, secondary bile acids activate the farnesoid X receptor in pancreatic stromal cells, potentially creating a tumor-permissive microenvironment [33]. These mechanisms underscore the dual role of GM metabolites-acting as both protective and pathogenic agents-depending on microbial composition, host genetics, and environmental factors.

Our findings reveal significant associations between several GM taxa and the risk of pNETs. Specifically, taxa such as the family Sutterellaceae, the class Paraprevotella, the species Paraprevotella unclassified, and the species Ruminococcus torques increased the risk of pNETs. The mechanism may lie in the fact that these intestinal flora are adherent to the intestinal mucosa, disrupting the barrier function of the intestinal mucosa and triggering inflammation, and importantly, eliciting a robust immune response at the same time, which may be at the root of the intestinal inflammation, as well as the development of the disease, in these at-risk populations [34, 35]. In contrast, the class Gammaproteobacteria, the family Acidaminococcaceae, the species Paraprevotella xylaniphila, and the species Bacteroides finegoldii were associated with a reduced risk of pNETs. These results are consistent with previous research suggesting that dysbiosis, or an imbalance in GM composition, can influence cancer development by modulating inflammation, immune response, and metabolic pathways [36–38]. Interestingly, our analysis of GM pathways identified that anhydromuropeptides recycling pathway positively correlated with pNETs risk, whereas other pathways were negatively correlated. The other pathways were negatively correlated, whereas this pathway may inhibit the host immune response by increasing the efficient bacterial recycling of peptidoglycan, which decreases the release of immune-stimulating fragments into the internal environment, allowing the bacteria to evade detection [39]. This highlights the complexity of the GM's role in tumor biology, where specific microbial functions may promote or inhibit tumorigenesis.

Mediation analysis identified that CD25 expression on CD45RA+CD4+ non-regulatory T cells mediates the effect of the species Ruminococcus torques on pNETs, suggesting that this gut microbial species influences pNETs development via immune modulation. The negative correlation between the species Ruminococcus torques abundance and CD25 levels on CD45RA+CD4+ non-Tregs, coupled with the positive association of these cells with pNETs, aligns with prior studies proposing dual roles for such immune populations: either participating in antitumor responses or being co-opted by tumors to facilitate immune evasion [36–38]. Recent work by Zhang et al. [33] further supports this mechanism, demonstrating that mucin-degrading bacteria like the species Ruminococcus torques compromise intestinal barrier integrity, leading to systemic translocation of lipopolysaccharide and activation of pancreatic stromal cells via TLR2/4 signaling, which promotes fibrotic and immunosuppressive microenvironments. The rationale for focusing on CD45RA+CD4+ non-Tregs lies in their identity as naive T cells primed for activation, where CD25 amplifies IL-2 signaling to drive clonal expansion. This is consistent with findings from Massironi [32], who reported that gut microbiota depletion reduces IL-2 bioavailability, impairing Treg function and accelerating tumor growth in preclinical models. Furthermore, the species Ruminococcus torques may skew T cell responses toward pro-inflammatory phenotypes; Cao et al. [31] showed that Ruminococcus species drive Th17 polarization through aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation by tryptophan metabolites, a pathway implicated in inflammation-driven pancreatic dysplasia [31]. Finally, while the species Bacteroides finegoldii was associated with reduced pNETs risk in our study, Massironi et al. [14] revealed that Bacteroides-derived sphingolipids inhibit natural killer cell cytotoxicity via TLR4 signaling, suggesting a broader role for GM metabolites in immune evasion across cancers. These findings collectively underscore the therapeutic potential of targeting GM-immune crosstalk to disrupt protumorigenic pathways.

The results of this study have significant implications for developing new therapeutic strategies for pNETs. We can consider novel interventions by identifying specific GM taxa and pathways that influence pNETs risk and understanding the mediating role of immune cells. For instance, manipulating the GM through dietary interventions, probiotics, or fecal microbiota transplantation could be explored as potential strategies to modulate immune responses and reduce pNETs risk [40, 41]. Furthermore, integrating GM and immune profiles could enhance the precision of pNETs treatment. Immunotherapies with variable efficacy in pNETs might be optimized by considering a patient's GM composition, thereby personalizing treatment approaches.

Our study’s strengths include a two-sample MR approach for robust causal inference, comprehensive analysis of GM taxa/pathways, and immune cell mediation to unravel GM-pNETs interactions. However, key limitations must be acknowledged. The reliance on European-descent populations introduces critical constraints, as genetic homogeneity in European cohorts contrasts sharply with the genetic and environmental diversity of non-European groups. Population-specific variants (e.g., HLA or CYP family polymorphisms), divergent gene-environment interactions (e.g., diet, microbiome influences), and differences in immune response pathways may alter GM-pNETs dynamics in underrepresented populations [42, 43]. While MR reduces confounding, residual pleiotropy risks persist.

Our study identified causal relationships between specific GM taxa and pNETs risk, yet the clinical translation of these findings requires deeper exploration of host-microbe interactions in heterogeneous patient populations. Although tumor grading data were unavailable in the FinnGen cohort used here, prior observational studies suggest that GM composition may correlate with tumor aggressiveness. For instance, in colorectal cancer, Fusobacterium nucleatum enrichment is linked to advanced tumor stage and poorer prognosis [44], while Bacteroides fragilis toxin-positive strains promote pro-inflammatory microenvironments that accelerate neoplasia progression [45]. Translating these insights to pNETs, future studies should stratify patients by tumor grade (e.g., WHO G1 vs. G3) or functional status to evaluate whether GM dysbiosis drives molecular subtypes or therapeutic resistance. Additionally, integrating patient-specific features-such as age, sex, or comorbidities-into multi-omics analyses could uncover personalized GM signatures predictive of disease course or treatment response. Overall, while our MR design precludes direct assessment of these factors, longitudinal cohorts with detailed clinical annotations are essential to bridge this gap and advance GM-targeted precision oncology.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides strong evidence for the causal role of specific GM taxa and pathways in developing pNETs and highlights the mediating role of immune cell signatures. These findings open new avenues for research and therapeutic strategies to modify the GM to prevent and treat pNETs.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the participants and researchers of the FinnGen study. We are also very grateful to Lopera-Maya EA et al. for the GM GWAS study and Orrù V et al. for the immune cells GWAS study.

Author contributions

FC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Software, Methodology and Writing – original draft. YZ: Data curation and Investigation. XM: Formal analysis. RL and HH: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision and Writing – review & editing. All authors reviewed and approved the fnal version of the manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by Medical Minimally Invasive Center Program of Fujian Province and National Key Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction Program, China (No. 2021-76), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (No. 2020 J011013), Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian province, China (No. 2023Y9149).

Data availability

The data that support the results of this study are publicly available in the MiBioGen, FinnGen and GWAS catalog.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Fangsheng Chen, Yuan Zhou and Xinwen Mao have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Ronggui Lin and Heguang Huang have contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103(2):153–71. 10.1159/000443171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halfdanarson TR, Rabe KG, Rubin J, Petersen GM. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(10):1727–33. 10.1093/annonc/mdn351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3063–72. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7285):59–65. 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cani PD. Human gut microbiome: hopes, threats and promises. Gut. 2018;67(9):1716–25. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan Y, Pedersen O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(1):55–71. 10.1038/s41579-020-0433-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchesi JR, Adams DH, Fava F, et al. The gut microbiota and host health: a new clinical frontier. Gut. 2016;65(2):330–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gentile CL, Weir TL. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science. 2018;362(6416):776–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamed A, Asa SL, McCormick T, et al. The role of the microbiome in gastroentero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs). Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022;44(5):2015–28. 10.3390/cimb44050136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitale G, Dicitore A, Barrea L, et al. From microbiota toward gastro-enteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: Are we on the highway to hell? Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2021;22(3):511–25. 10.1007/s11154-020-09589-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas RM, Jobin C. Microbiota in pancreatic health and disease: the next frontier in microbiome research. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(1):53–64. 10.1038/s41575-019-0242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157(1):121–41. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng J, Yang K, Nie H, et al. The mechanism of intestinal microbiota regulating immunity and inflammation in ischemic stroke and the role of natural botanical active ingredients in regulating intestinal microbiota: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;157: 114026. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massironi S, Facciotti F, Cavalcoli F, et al. Intratumor microbiome in neuroendocrine neoplasms: A new partner of tumor microenvironment? A pilot study. Cells. 2022. 10.3390/cells11040692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gopalakrishnan V, Helmink BA, Spencer CN, Reuben A, Wargo JA. The influence of the gut microbiome on cancer, immunity, and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(4):570–80. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hezaveh K, Shinde RS, Klotgen A, et al. Tryptophan-derived microbial metabolites activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in tumor-associated macrophages to suppress anti-tumor immunity. Immunity. 2022;55(2):324-340e8. 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulthess J, Pandey S, Capitani M, et al. The short chain fatty acid butyrate imprints an antimicrobial program in macrophages. Immunity. 2019;50(2):432-445e7. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Havasi A, Sur D, Cainap SS, et al. Current and new challenges in the management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: the role of miRNA-based approaches as new reliable biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. 10.3390/ijms23031109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rindi G, Wiedenmann B. Neuroendocrine neoplasia of the gastrointestinal tract revisited: towards precision medicine. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(10):590–607. 10.1038/s41574-020-0391-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith GD, Ebrahim S. “Mendelian randomization”: Can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(1):1–22. 10.1093/ije/dyg070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey SG. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27(8):1133–63. 10.1002/sim.3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long Y, Tang L, Zhou Y, Zhao S, Zhu H. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and cancers: a two-sample Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):66. 10.1186/s12916-023-02761-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas H. Mendelian randomization reveals causal effects of the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(4):198–9. 10.1038/s41575-019-0133-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Yu X, Wu X, Chai K, Wang S. Causal relationships between gut microbiota, immune cell, and Non-small cell lung cancer: a two-step, two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J Cancer. 2024;15(7):1890–7. 10.7150/jca.92699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boehm FJ, Zhou X. Statistical methods for Mendelian randomization in genome-wide association studies: a review. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:2338–51. 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ong JS, MacGregor S. Implementing MR-PRESSO and GCTA-GSMR for pleiotropy assessment in Mendelian randomization studies from a practitioner’s perspective. Genet Epidemiol. 2019;43(6):609–16. 10.1002/gepi.22207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng H, Garrick DJ, Fernando RL. Efficient strategies for leave-one-out cross validation for genomic best linear unbiased prediction. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2017;8:38. 10.1186/s40104-017-0164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, Ingelsson E, Thompson SG. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology. 2017;28(1):30–42. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504(7480):451–5. 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park J, Kim M, Kang SG, et al. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8(1):80–93. 10.1038/mi.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao Z, Huang J, Long X. Causal relationships between gut microbiotas, blood metabolites, and neuroendocrine tumors: a mediated mendelian randomization study. Neuroendocrinology. 2024;114(11):981–92. 10.1159/000541298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massironi S. Unraveling the microbiome’s role in neuroendocrine neoplasms: a new perspective. Neuroendocrinology. 2024;114(11):977–80. 10.1159/000541678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang CY, Jiang SJ, Cao JJ, et al. Investigating the causal relationship between gut microbiota and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1420167. 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1420167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen YJ, Wu H, Wu SD, et al. Parasutterella, in association with irritable bowel syndrome and intestinal chronic inflammation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33(11):1844–52. 10.1111/jgh.14281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joossens M, Huys G, Cnockaert M, et al. Dysbiosis of the faecal microbiota in patients with Crohn’s disease and their unaffected relatives. Gut. 2011;60(5):631–7. 10.1136/gut.2010.223263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, et al. Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(24):1907–11. 10.1093/jnci/djt300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zackular JP, Rogers MA, Ruffin MT, Schloss PD. The human gut microbiome as a screening tool for colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res Phila. 2014;7(11):1112–21. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Microbiota and diabetes: an evolving relationship. Gut. 2014;63(9):1513–21. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-306928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dik DA, Fisher JF, Mobashery S. Cell-wall recycling of the gram-negative bacteria and the nexus to antibiotic resistance. Chem Rev. 2018;118(12):5952–84. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nobili V, Mosca A, Alterio T, Cardile S, Putignani L. Fighting fatty liver diseases with nutritional interventions, probiotics, symbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1125:85–100. 10.1007/5584_2018_318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boicean A, Ichim C, Todor SB, Anderco P, Popa ML. The importance of microbiota and fecal microbiota transplantation in pancreatic disorders. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024. 10.3390/diagnostics14090861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin W, Gu C, Chen Z, Xue S, Wu H, Zeng L. Exploring the relationship between gut microbiota and breast cancer risk in European and East Asian populations using Mendelian randomization. BMC Cancer. 2024;24(1):970. 10.1186/s12885-024-12721-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mester R, Hou K, Ding Y, et al. Impact of cross-ancestry genetic architecture on GWASs in admixed populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2023;110(6):927–39. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mima K, Sukawa Y, Nishihara R, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and T cells in colorectal carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(5):653–61. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dejea CM, Fathi P, Craig JM, et al. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science. 2018;359(6375):592–7. 10.1126/science.aah3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the results of this study are publicly available in the MiBioGen, FinnGen and GWAS catalog.