Abstract

Introduction

Uterus didelphys is a congenital Müllerian anomaly characterized by the presence of two separate uteri and two cervixes. It is associated with an increased risk of pregnancy complications, including miscarriage, malpresentation, and labor dystocia.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old gravida 3, para 2, living 2, at 39 weeks of gestation with two previous cesarean sections, presented in labor before her planned elective cesarean delivery. She was incidentally diagnosed with uterus didelphys during her first pregnancy after experiencing poor labor progression, leading to an emergency cesarean section. In this pregnancy, she initiated antenatal care at 12 weeks and attended seven routine visits, all of which were unremarkable. She underwent an emergency cesarean section and delivered a live male neonate weighing 3.26 kg with good Apgar scores. Her postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged in stable condition after 72 h of observation.

Discussion

Uterus didelphys is associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including recurrent pregnancy loss, fetal malpresentation, and the need for cesarean delivery. The successful maternal and neonatal outcomes highlight the importance of early diagnosis, close antenatal monitoring, and timely delivery planning in patients with congenital uterine anomalies.

Conclusion

This case underscores the significance of early diagnosis and meticulous antenatal surveillance in women with congenital uterine anomalies. Although a didelphic uterus presents challenges in pregnancy management, appropriate obstetric care and timely surgical intervention can lead to favorable maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Keywords: Uterus didelphys, Uterine anomaly, Cesarean delivery, Case report

Highlights

-

•

Uterus didelphys can be incidentally diagnosed during cesarean delivery following labor dystocia, as the anomaly may remain asymptomatic until pregnancy complications arise.

-

•

Despite the structural abnormality, a successful and uneventful pregnancy can be achieved to term with proper antenatal care.

-

•

Surgical intervention, particularly cesarean delivery, is often necessary in patients with uterus didelphys to address risks such as labor dystocia and malpresentation, ensuring optimal maternal and neonatal outcomes.

-

•

Early diagnosis through imaging or incidental findings, along with close antenatal monitoring, plays a crucial role in pregnancy management, allowing for timely interventions and reducing obstetric complications.

1. Introduction

Müllerian duct anomalies (MDAs) are congenital malformations resulting from disruptions in the formation, fusion, or resorption of the Müllerian ducts during embryogenesis [1]. These anomalies, classified by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) into seven categories, affect reproductive anatomy and function to varying degrees. Uterus didelphys, a Class III MDA, arises from the complete failure of Müllerian duct fusion, leading to the presence of two separate uteri, often with duplicated cervices and, in some cases, a vaginal septum [2].

While many individuals with uterus didelphys remain asymptomatic, some may experience dyspareunia, menstrual abnormalities, or complications such as hematocolpos, hematometra and abnormal labor. This condition is also associated with a higher prevalence of renal and urological anomalies, necessitating comprehensive diagnostic evaluation using ultrasonography, MRI, and, in certain cases, hysterosalpingography. Although MDAs have been linked to adverse fertility and pregnancy outcomes—including preterm labor, fetal growth restriction, and an increased need for cesarean delivery—many individuals achieve successful pregnancies. Management strategies focus on symptom relief, with surgical intervention reserved for specific complications, as extensive reconstructive procedures pose significant risks [3,4].

We present the case of a 39-year-old gravida 3, para 2, living 2, who was first diagnosed with a didelphic uterus incidentally during her first pregnancy following poor labor progression, which necessitated a cesarean delivery. Despite the uterine anomaly, she has had a total three uneventful pregnancies managed by cesarean delivery. This report has been prepared in accordance with the SCARE 2023 guidelines [5].

2. Case

A 39-year-old African female Gravida 3 Para 2 Living 2 at 39 weeks of gestation, with a history of two previous cesarean deliveries, presented with intermittent lower abdominal pain that has progressively increased in intensity and radiated to the back. She denied any per vaginal bloody show or leakage of amniotic fluid and reported normal fetal movements.

She had booked antenatal care at 12 weeks of gestation and attended a total of seven uneventful visits. Her blood group is AB positive, and serological tests were negative. Her obstetric history included an emergency cesarean section seven years ago due to poor labor progression, during which a didelphic uterus was incidentally identified. She delivered a male infant weighing 3.5 Kg without complications. This was followed by an elective cesarean section three years later, resulting in the delivery of another male infant without complications.

She has no history of blood transfusion or known allergies. She experienced menarche at the age of 14 and has a regular menstrual cycle of 29 days, with menstrual flow lasting up to five days. She reports no dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia. Her medical history is unremarkable, with no evidence of renal, skeletal, or cardiac disease.

3. Clinical findings

Upon admission, the patient was alert, fully oriented, and exhibited no signs of pallor, dyspnea, or lower limb edema.

Abdominal examination showed a gravid abdomen pfannenstiel scar with a fundal height consistent with the gestational age. The fetus was in a longitudinal lie with a cephalic presentation, demonstrating normal fetal heart rates. Mild uterine contractions were noted, occurring once every 10 min and lasting 20 s.

3.1. Timeline of current episode

Admitted underwent emergency cesarean delivery on 14th February 2025 and was discharged on 17th February 2025.

3.2. Diagnostic assessment

Following the incidental finding during the first pregnancy, a transvaginal ultrasound was performed after the puerperium, confirming the presence of uterine didelphys (Fig. 1). A subsequent ultrasound conducted during the second pregnancy also revealed uterine didelphys (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Transvaginal Image taken after puerperium of the first pregnancy, Separate divergent uterine horns are identified with a large fundal cleft. Endometrial cavities are uniformly separate, with no evidence of communication. Two separate cervices were also appreciated.

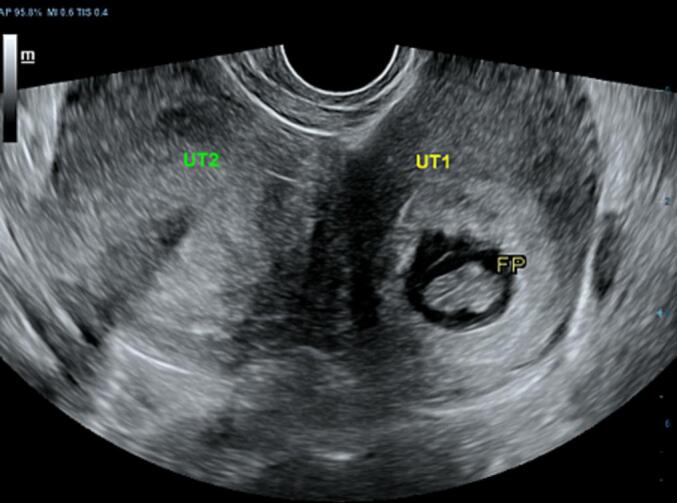

Fig. 2.

Image taken during the second pregnancy, separate divergent uterine horns are identified with an intrauterine early pregnancy within one the uterine horn and the other endometrial cavity is empty.

3.3. Diagnosis

Term pregnancy in a patient with known uterus didelphys and two previous cesarean scars in labor

3.4. Therapeutic interventions

The patient underwent an emergency cesarean delivery, resulting in the birth of a male infant weighing 3.26 Kg, with APGAR scores of 8 and 9 at the first and fifth minutes, respectively. The uterus was repaired in double layers using Vicryl, and hemostasis was achieved. A second uterine body was identified (Fig. 3). The abdomen was then closed in layers. Post cesarean section was faring well and discharged after 72 h as per institution protocol. Both mother and the baby recovered well without complication during postnatal follow up.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative findings during the third pregnancy showing the two conjoined uterine bodies, immediately after uterine repair following delivery.

3.5. Follow-up and outcome of interventions

The patient was discharged after 72 h and followed up one week later, with no complaints. The wound was clean and dry.

4. Discussion

Uterine malformations (UMs) are congenital anomalies arising from developmental disruptions in the formation, fusion, or absorption of the Müllerian ducts during embryogenesis [1]. The estimated prevalence of UMs in the general population ranges from 0.5 % to 5.0 %, with a specific prevalence of 0.3 % for uterus didelphys [6]. According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), Müllerian duct anomalies (MDAs) are classified into seven categories, from Class I (hypoplasia or agenesis, such as Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome) to Class VII (uterine abnormalities due to diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure), as detailed in Table 1. Uterus didelphys, classified as Class III MDA, results from complete failure of Müllerian duct fusion during embryonic development [2]. This condition results in the formation of two separate uteri, each with its own endometrial cavity, and may be associated with duplicated cervices and, in some cases, a vaginal septum. In the current case, the patient presented with two uteri and two cervices, without a vaginal septum. Approximately 30 % to 36 % of individuals with MDA also exhibit associated renal or urological anomalies [4]. The patient in this case report did not present with any renal or urological symptoms; therefore, further investigations such as MRI to evaluate the urinary system were not deemed necessary.

Table 1.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) classification of Müllerian duct anomalies.

| Class | Anomaly | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hypoplasia/aplasia | Complete or partial absence of Müllerian structures, such as Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. |

| II | Unicornuate uterus | One Müllerian duct is incompletely developed or fails to develop, resulting in a single uterine horn. May be associated with a rudimentary horn, which can be functional or non-functional. |

| III | Uterus didelphys | Complete failure of fusion of both Müllerian ducts, leading to two uteri, two endometrial cavities, and often two cervices. Usually, there is no communication between the cavities. |

| IV | Bicornuate uterus | Partial failure of Müllerian duct fusion, resulting in a uterus with two horns that share a single cervix. Can be complete (two endometrial cavities) or partial (some degree of communication). |

| V | septate uterus | Incomplete resorption of the midline uterine septum, leading to a fibrous or muscular partition dividing the endometrial cavity. Associated with recurrent pregnancy loss. |

| VI | arcuate uterus | A mild midline indentation of the endometrial cavity due to incomplete resorption of the septum. Considered a normal variant with minimal reproductive impact. |

| VII | Diethylstilbestrol (DES)-related anomaly | Abnormal uterine shape and hypoplastic cervix due to in utero exposure to DES, a synthetic estrogen. Common features include a T-shaped endometrial cavity. |

Although many individuals with uterus didelphys are asymptomatic, some may present with symptoms like painful intercourse (dyspareunia), a vaginal septum, accumulation of menstrual blood in the vagina (hematocolpos), or blood retention in the uterus (hematometra). Diagnostic imaging is crucial for identifying Müllerian duct anomalies (MDA), with hysterosalpingography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) being the primary modalities. The introduction of three-dimensional ultrasound has reduced reliance on hysterosalpingography, and additional imaging is often necessary to evaluate potential renal or urological anomalies. Although laparoscopy and hysteroscopy can serve as diagnostic tools, their invasive nature limits their routine use [7,8].

Müllerian duct anomalies (MDAs) are linked to an increased risk of preterm delivery (before 37 weeks), preterm premature rupture of membranes, fetal malpresentation at birth, and higher perinatal mortality rates. The likelihood of preterm birth varies depending on the specific uterine anomaly, with reported rates of 31 % for septate, 39 % for bicornuate, 43 % for unicornuate, and 56 % for didelphys anomalies. In contrast, individuals with a septate uterus face the highest relative risk of first- and second-trimester miscarriage. However, current evidence does not strongly support a direct association between MDAs and infertility [9]. In the presented case, the patient had no history of infertility, pregnancy loss, or difficulty conceiving.

Women with uterine anomalies have a higher likelihood of requiring a cesarean section, with the highest rate (82 %) seen in those with uterus didelphys. These conditions are also associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes, breech presentation, labor dystocia, placenta previa, and placental abruption [10]. Many patients with Müllerian duct anomalies (MDA) remain asymptomatic and do not require treatment. However, in cases where obstruction is present, surgical intervention is often necessary and may lead to permanent infertility. Management typically involves the surgical resection of the vaginal septum to relieve symptoms. Strassmann metroplasty, a procedure designed to unify the two uteri, is associated with considerable blood loss and a high risk of hysterectomy, which restricts its clinical use [11].

5. Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of early diagnosis, thorough antenatal monitoring, and timely obstetric intervention in managing pregnancies complicated by uterus didelphys. Despite the structural challenges posed by this congenital anomaly, favorable maternal and neonatal outcomes can be achieved with appropriate prenatal care and surgical planning. The need for cesarean delivery is often inevitable due to risks such as labor dystocia and malpresentation, emphasizing the role of vigilant obstetric surveillance. Ultimately, recognizing and addressing congenital uterine anomalies early can significantly improve pregnancy outcomes and ensure optimal maternal and neonatal well-being.

5.1. Patient perspective

“I'm so relieved that the surgery was successful, and both my baby and I are in good health. I understand how important it is to follow the recommended interpregnancy interval, and I'm committed to following the medical advice for future family planning and postnatal care. I also feel very satisfied with the pain management and the overall care I received during my stay at the hospital. I truly appreciate the support and attention from the medical team throughout the process.”

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lusajo Mwagobele and Gregory Ntiyakunze: Study conception, Manuscript drafting, Data collection and Patient management

Ronak Mulji: Manuscript drafting and Proofreading

Zainab Fidaali: Radiology interpretation

Lynn Moshi: Manuscript revision and Patient management.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Guarantor

Dr. Lynn Moshi.

Funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- 1.Chandler T.M., Machan L.S., Cooperberg P.L., Harris A.C., Chang S.D. Müllerian duct anomalies: from diagnosis to intervention. Br. J. Radiol. Dec 2009;82(984):1034–1042. doi: 10.1259/bjr/99354802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeifer S.M., Attaran M., Goldstein J., Lindheim S.R., Petrozza J.C., Rackow B.W., et al. ASRM müllerian anomalies classification 2021. Fertil. Steril. Nov 2021;116(5):1238–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raga F., Bauset C., Remohi J., Bonilla-Musoles F., Simón C., Pellicer A. Reproductive impact of congenital Müllerian anomalies. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. Oct 1997;12(10):2277–2281. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.10.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ScienceDirect; A review of Mullerian anomalies and their urologic associations. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0090429520305112 Available from: (Internet, cited 2025 Mar 4)

- 5.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A., et al. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. May 2023;109(5):1136. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan Y.Y., Jayaprakasan K., Zamora J., Thornton J.G., Raine-Fenning N., Coomarasamy A. The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2011;17(6):761–771. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radiopaedia.org; Müllerian duct anomalies | Radiology Reference Article. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/mullerian-duct-anomalies Available from: (Internet, cited 2025 Mar 5)

- 8.Olpin J.D., Moeni A., Willmore R.J., Heilbrun M.E. MR imaging of Müllerian fusion anomalies. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. Aug 2017;25(3):563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugi M.D., Penna R., Jha P., Pōder L., Behr S.C., Courtier J., et al. Müllerian duct anomalies: role in fertility and pregnancy. RadioGraphics. Oct 2021;41(6):1857–1875. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021210022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Google Scholar; Pankaja: successful pregnancy with uterus didelphys. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=J.%20Androl.%20Gynaecol.&title=Successful%20Pregnancy%20with%20Uterus%20Didelphys&author=S.%20Pankaja&author=P.%20Ip&author=F.%20O%E2%80%99Mahony&volume=4&publication_year=2016&pages=3& Available from: (Internet, cited 2025 Mar 5)

- 11.Akhtar M., Saravelos S., Li T., Jayaprakasan K., the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Reproductive implications and management of congenital uterine anomalies. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020;127(5):e1–13. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]