Abstract

Background

Bone defects remain a significant challenge in orthopedics, and traditional treatments often face limitations. Icariin (ICA) has been shown to promote osteogenic differentiation and angiogenesis, which may benefit bone repair.

Methods

ICA-loaded microspheres were prepared using an evaporation method with a co-solvent system. The encapsulation efficiency, drug loading, and release characteristics were evaluated. Silk fibroin/chitosan/nano-hydroxyapatite (SF/CS/nHA) composite scaffolds incorporated with ICA microspheres were fabricated using vacuum freeze-drying. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were cultured on these scaffolds in vitro. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to observe the morphology of microspheres and scaffolds, as well as cell adhesion. In vitro assessments of BMSC morphology, proliferation, and migration on different scaffolds were conducted using CCK-8 assays, live/dead staining, and scratch tests. Osteogenic differentiation was evaluated by alkaline phosphatase staining, Alizarin Red staining, immunofluorescence, RT-qPCR, and Western blotting. A rabbit radial critical-size bone defect model was established in vivo, and SF/CS/nHA-ICA composite scaffolds were implanted at the defect sites. Bone repair effects were assessed by CT imaging, hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining, and Masson’s trichrome staining. Osteogenic and angiogenic protein expression levels were further analyzed by immunohistochemistry and Western blot.

Results

In vitro experiments demonstrated that the SF/CS/nHA-ICA group had superior BMSC adhesion, cell morphology, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation compared to other groups (P < 0.05). In vivo, evaluations indicated that the addition of ICA significantly enhanced bone regeneration and vascularization at the defect sites compared to control and other experimental groups. Western blot and immunohistochemical analyses confirmed significant upregulation of osteogenic and angiogenic proteins (type I collagen, runt-related transcription factor 2, osteocalcin, vascular endothelial growth factor) in the SF/CS/nHA-BMSCs-ICA group.

Conclusion

ICA-loaded scaffolds effectively promote bone regeneration and repair of bone defects, offering a potential strategy for the treatment of bone defects.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12891-025-08824-4.

Keywords: Icariin, Biomimetic bone scaffold, Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, Bone regeneration, Bone tissue engineering

Introduction

Bone defects are common orthopedic conditions caused by various factors, including trauma, infection, and tumor resection, which disrupt the normal structure and function of bone tissue [1]. Small-scale bone defects typically have a certain degree of self-repair capability, allowing for natural healing through the bone regeneration process. However, when the defect exceeds a critical threshold, which is known as a critical-sized bone defects, spontaneous bone regeneration fails. These defects can significantly impact the life quality of patient, making additional clinical interventions necessary to promote healing [2–4]. Currently, several approaches are widely used in clinical practice to treat critical-sized bone defects, including autologous bone grafting, allogeneic bone grafting, and metallic implants [5]. While these methods can effectively repair bone defects to some extent, they each have limitations. Autologous bone grafting offers excellent biocompatibility and osteogenic potential, but its use is constrained by limited donor availability and potential complications such as nerve and vascular damage, inflammation, and infection at the donor site [6]. Allogeneic bone grafting, on the other hand, carries the risk of disease transmission and immune rejection. Meanwhile, metallic implants provide superior osteoinductive properties and mechanical strength, but they are associated with significant cytotoxicity and poor biodegradability [7, 8].

With the ongoing advancement of bone tissue engineering technology, innovative strategies for bone defect repair are being provided [9]. This approach integrates biological and engineering principles to mimic the natural bone regeneration by combining seed cells, biological scaffolds, and growth factors, thereby promoting defect healing [10]. Among these components, biological scaffolds serve as the structural foundation for cell growth and differentiation. Ideally, scaffold materials should possess excellent mechanical strength, toughness, and biocompatibility [11]. However, in practical applications, it is challenging for a single material to meet al.l these stringent requirements. For example, natural polymers such as collagen exhibit excellent biocompatibility but have relatively low mechanical strength, making them insufficient for the mechanical demands of bone defect sites. Conversely, synthetic inorganic materials, such as hydroxyapatite, offer superior mechanical properties but suffer from poor hydrophilicity and difficult-to-control degradation rates, which hinder cell adhesion and bone tissue regeneration. As a result, developing composite scaffolds that combine the advantages of different materials has become a major research focus [12, 13].

Hydroxyapatite-natural polymer composites achieve excellent biocompatibility and hydrophilicity through organic templating, while the inorganic phase enhances mechanical strength, making them more suitable for bone tissue regeneration [14, 15]. These materials have demonstrated significant advantages in clinical applications [16]. Nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA), as a key inorganic component, closely mimics the microstructure of human bone tissue, significantly improving fracture toughness and mechanical strength [17, 18]. Additionally, its large specific surface area facilitates strong chemical bonding with the organic framework. Silk fibroin (SF), the primary protein in natural silk, is widely used in biomedical applications such as surgical sutures and artificial skin due to its low immunogenicity and excellent biocompatibility [19, 20]. Chitosan (CS), the only naturally occurring basic polysaccharide, has a structure highly similar to human glycosaminoglycans, providing superior biocompatibility and adaptability to the human microenvironment [21]. The free amino groups in CS molecules enable chemical modifications with other biomaterials, while its outstanding biodegradability and cell affinity make it an ideal biomaterial for medical applications [22]. Based on these properties, our previous research developed a biomimetic composite scaffold composed of SF and CS as the organic framework, with nHA as the primary inorganic component. This scaffold not only exhibits excellent biocompatibility but also meets the fundamental requirements for bone defect repair in terms of porosity, pore size, and mechanical strength [23, 24], providing new research directions and promising applications in the field of bone tissue engineering.

Epimedium sagittatum, a medicinal plant with a long history in traditional Chinese medicine, has been widely used for centuries in the treatment of fractures, osteoarticular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and aging-related conditions [25]. Icariin (ICA) (C₃₃H₄₀O₁₅, molecular weight 676.67), the key pharmacologically active component of Epimedium sagittatum, exhibits significant osteoinductive properties [26]. Previous studies have shown that ICA promotes the proliferation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) by accelerating the cell cycle and enhances osteogenic differentiation by upregulating the expression of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteocalcin (OCN), and type I collagen (COL-1) [27]. Additionally, ICA exerts a dual effect by promoting osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells while inhibiting osteoclast activity, thereby enhancing bone formation and reducing bone resorption to exert a bone-protective function [28, 29]. Due to its stable chemical properties, high melting point, and ease of extraction from Epimedium sagittatum, ICA is commonly used in bone defect repair and drug-loaded scaffold preparation. As a potential small-molecule therapeutic agent, ICA exhibits a sustained release profile following bone grafting, significantly accelerating bone regeneration [30, 31].

In this study, ICA-loaded sustained-release microspheres were integrated with an SF/CS/nHA composite scaffold, and BMSCs were incorporated to develop a novel bone tissue engineering material. The osteogenic potential of this composite material was evaluated by assessing its ability to promote BMSC proliferation and osteogenic differentiation. Furthermore, using a rabbit radial bone defect model, the bone repair efficacy of the composite scaffold was systematically assessed. This study aims to explore feasible strategies for clinical bone defect treatment while providing an experimental foundation and theoretical basis for advancements in bone tissue engineering.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of rabbit BMSCs

The study selected 2 kg male New Zealand White rabbits. After anesthesia was induced, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells were extracted from the femur and tibia using the whole bone marrow extraction method. The cells were then placed in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for static culture. Once the cells covered approximately 90% of the bottom of the culture flask, passaging was performed, and the first passage was labeled as passage 1 (P1), followed by P2, P3, and so on. Passage 3 (P3) was used for subsequent cell experiments.

Identification of BMSCs

Multipotent differentiation potential of BMSCs

P3 BMSCs were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 10⁵ cells per well. Osteogenic differentiation experiment: After 14 days of osteogenic induction, cells were fixed with PFA, stained with Alizarin Red S, and mineralized nodules (red mineralized nodules) were observed under a microscope. Chondrogenic differentiation experiment: After 21 days of chondrogenic induction, cells were fixed with PFA, stained with Alcian Blue, and the cartilage matrix (blue stained areas) was observed under a microscope. Adipogenic differentiation experiment: After 14 days of adipogenic induction, cells were fixed with PFA, stained with Oil Red O, and lipid droplets (reddish-brown lipid droplets) were observed under a microscope.

Immunofluorescence identification of BMSCs

P3 BMSCs were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 1 × 10⁵ cells per well and cultured in a cell incubator. When the cells reached approximately 70% confluence, they were fixed with PFA. The cells were permeabilized with Triton X-100 solution, blocked with BSA (bovine serum albumin), and incubated with primary antibodies (CD29, CD44, CD90, CD34, HLA-DR, all diluted at 1:200). After incubating overnight at 4 °C, secondary antibodies were added at room temperature in the dark. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. After adding a fluorescence quenching agent, fluorescence signals were observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Preparation and characterization of ICA-loaded microspheres

Preparation and morphology of ICA-loaded microspheres

Based on previous studies, ICA-loaded microspheres were prepared using a solvent evaporation method. Briefly, 10 mg of ICA and 600 mg of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) were dissolved in 12.5 mL of dichloromethane. The solution was ultrasonicated for 30 s in an ice bath and then slowly added dropwise into 400 mL of 3% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution under magnetic stirring at 800 rpm, room temperature for 4 h to allow for organic solvent evaporation. After preparation, the microspheres were collected via centrifugation at 4 °C (3000 rpm for 30 min), washed five times with deionized water, and freeze-dried in a vacuum for 4 h, yielding 17.71 mg of ICA-loaded microspheres. The microspheres were sterilized with ethylene oxide and stored at 4 °C for future use. The morphology of the microspheres was examined visually and further characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Establishment of ICA concentration–absorbance standard curve and determination of drug loading and encapsulation efficiency

Based on a previously established drug concentration–absorbance standard curve (270 nm), 50 mg of ICA was dissolved in 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted to 50 mL with 0.01 mol/L PBS, resulting in a 1 mg/mL ICA stock solution. Serial dilutions were prepared by adding 5 µL, 10 µL, 15 µL, 20 µL, 25 µL, 30 µL, 35 µL, 40 µL, 45 µL, and 50 µL of the ICA stock solution into 50 mL volumetric flasks, and adjusting the final volume with 0.01 mol/L PBS to obtain ICA solutions at concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, and 1000 ng/mL. PBS was used as a blank control. The absorbance of each solution was measured at 270 nm using a UV spectrophotometer, and a standard curve equation was obtained:

Y = 0.000966x + 0.01356 (R2 = 0.9993).

To determine drug loading (DL%) and encapsulation efficiency (EE%), 5 mg of ICA-loaded microspheres were dissolved in 0.5 mL of ethyl acetate for redissolution. The solution was then mixed with 10 mL of 0.01 mol/L PBS and shaken for 24 h. The ICA content was quantified by measuring absorbance at 270 nm using a microplate reader, and the concentration was calculated based on the standard curve equation.

Drug Loading (DL%) =(Mass of ICA in microspheres/ Total mass of microspheres)×100%.

Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%)=(Actual encapsulated ICA mass / Initial ICA mass)×100%.

Drug release kinetics of ICA from microspheres

50 mg of ICA-loaded microspheres were placed in a dialysis bag immersed in 100 mL of PBS (pH = 7.4) and incubated in a shaking water bath at 37 °C. Samples were collected at 6 h, 12 h, 1 day, 2 days, 4 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 2 months, and 3 months. At each time point, 1 mL of release medium was collected, and an equal volume of fresh PBS was added to maintain a constant volume. The released ICA concentration was determined using a UV spectrophotometer at 270 nm, and a release curve was plotted to analyze drug release kinetics.

Preparation and characterization of composite scaffolds

Preparation of SF/CS/nHA scaffolds

SF/CS/nHA scaffolds were prepared as previously established method. A 10 mL solution containing 2% (w/v) SF, CS, and nHA was prepared in a 1:1:1 mass ratio and thoroughly mixed at room temperature. 1.2 mL of the mixed solution was rapidly transferred into a casting mold and immediately frozen at -80 °C for 24 h. The frozen samples were vacuum-dried for 24 h. The dried scaffolds were immersed in a crosslinking solution composed of 75% methanol (CH₃OH) and 1 mol/L NaOH (1:1 volume ratio) for 24 h. After crosslinking, the samples were refrozen and vacuum-dried for another 24 h. Next, the scaffolds were immersed in a solution containing 50 mmol/L EDC and 20 mmol/L NHS (1:1 volume ratio) for 24 h for further crosslinking. After completing the crosslinking process, the samples were once again frozen and vacuum-dried. The final SF/CS/nHA scaffolds were stored at 4 °C for future use.

Preparation of SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffolds

Based on preliminary studies, an ICA sustained-release concentration of 10 µM was determined to be optimal for BMSC proliferation, differentiation, and activity. Therefore, the ICA concentration in this study was set at 10 µM. SF/CS/nHA scaffolds were placed into 48-well plates. ICA-loaded microspheres were dissolved in deionized water, and 200 µL of the microsphere suspension was uniformly dropped onto each SF/CS/nHA scaffold. The scaffolds were immediately frozen at -80 °C for 24 h. They were then freeze-dried under vacuum for 48 h to form the ICA-loaded SF/CS/nHA scaffold (SF/CS/nHA-ICA). The scaffolds were sterilized with ethylene oxide at low temperatures and stored for future use.

Preparation of SF/CS/nHA-BMSCs-ICA composite materials

Third-passage BMSCs (P3) were digested with 0.25% trypsin, and a single-cell suspension was prepared with a final concentration of 5.0 × 10⁶ cells/mL. Sterilized SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffolds were placed into 24-well plates. 500 µL of the BMSC suspension was seeded onto the scaffolds. DMEM/F12 complete medium was carefully added to form a three-dimensional ICA-loaded microsphere-cell-scaffold composite (SF/CS/nHA-BMSCs-ICA).

SEM (20 kV) was used to observe microsphere morphology, the scaffold’s 3D porous structure, microsphere distribution, and cell adhesion. The internal structure of the scaffold was observed using SEM. The image scale bar was calibrated using ImageJ software, which automatically identified the pore contours, measured the diameter of each pore, and calculated the average pore size and standard deviation. The porosity of each scaffold group was determined using a modified liquid displacement method. The scaffold was immersed in a 5 mL graduated cylinder containing ethanol for 0.5 h, until the air within the scaffold was completely displaced. Ethanol volumes were measured before and after immersing the scaffold, recorded as V0 and V1, respectively. The scaffold was then removed, and the remaining volume of ethanol was recorded as V2. The porosity was calculated as follows:

|

The overall scaffold was subjected to conventional mechanical property testing using a materials testing machine. The preload force was set to 0.1 N, the load rate was set to 0.1 N/min, and the deformation rate was set to 2 mm/min. Based on the test results, a stress-strain curve was plotted, the elastic modulus was calculated, and the mechanical properties were evaluated.

BMSC proliferation, cytotoxicity, and migration on the scaffold

CCK-8 assay for cell proliferation

SF/CS/nHA and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffolds were prepared with a diameter of 2 mm and a thickness of 1 mm. After sterilization, they were placed into 96-well plates. Experimental groups are as following.

BM group (control): BMSCs (2 × 10⁵ cells/well) seeded directly onto the 96-well plate.

SCN-BM group: BMSCs seeded onto the SF/CS/nHA scaffold at the same density.

SCN-BM-ICA group: BMSCs seeded onto the SF/CS/nHA-ICA composite scaffold.

Each group had three replicates. On days 1, 2, 3, and 5, CCK-8 assays were performed to assess cell proliferation by measuring the optical density (OD) at 450 nm. The assay was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Live/Dead cell staining for cytotoxicity

To evaluate cytotoxicity, BMSCs were seeded in blank 12-well plate (control), SF/CS/nHA scaffold, and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffold. Each well contained 2 × 10⁵ cells. After 3 days of culture, Calcein-AM (live cell stain) and propidium iodide (PI, dead cell stain) were added and incubated in the dark for 30 min. Cell viability was observed under a fluorescence microscope, and the percentage of live/dead cells was calculated. The experiment followed the manufacturer’s protocol.

Scratch wound assay for cell migration

P3 BMSCs were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 10⁷ cells per well. When cells reached ~ 90% confluence, a 100 µL sterile pipette tip was used to create a scratch wound in the monolayer. The cells were then treated with DMEM/F12 complete medium (control), SF/CS/nHA scaffold extract, and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffold extract. Cell migration was observed at 0, 24, and 48 h using an inverted microscope. Migration distances were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs

ALP and Alizarin red staining

P3 BMSCs were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 10⁵ cells/well (500 µL/well) and divided into three groups according to the previously described method. The complete culture medium was replaced with osteogenic induction medium containing DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin/streptomycin, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 nM dexamethasone, and 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid. On day 7, cells were fixed with 4% PFA, and ALP staining was performed using an ALP staining kit. The stained samples were observed and imaged, and quantitative ALP activity was assessed following the ALP quantification kit instructions. On day 14, Alizarin Red staining was performed to assess mineralized nodule formation. After staining, cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) was added, and the samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 562 nm using a microplate reader to quantify calcium deposition.

Immunofluorescence analysis

To further investigate the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, immunofluorescence staining was performed to detect runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx-2) expression on day 7 and OCN expression on day 14. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked with 5% BSA. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C in the dark, using Runx-2 (Proteintech, 20700-1-AP, 1:200 dilution) and OCN (Abcam, ab133612, 1:200 dilution). Then, cells were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies (Proteintech, 1:400 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI, and the cytoskeleton was labeled using phalloidin fluorescent staining. The samples were imaged under a fluorescence microscope, and results were documented. The experiment was conducted following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Osteogenesis- and angiogenesis-related gene and protein expression

On day 14, total ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted from each group using TRIzol reagent. The extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The relative mRNA expression levels of Runx-2, COL-1, OCN, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were analyzed using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a specific PCR kit. The primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

To assess protein expression levels, Western blotting was performed for Runx2, COL-1, OCN, and VEGF on day 14. Cells were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer, followed by ultrasonic disruption. Protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) protein assay kit, and a standard curve was plotted. Proteins were separated by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, MA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C (see Table S2 for details). The membrane was then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using a gel imaging system, and the intensity of each band was quantified.

Repair of critical-sized bone defects

Animal model establishment

Thirty-five two-month-old male New Zealand white rabbits were purchased from Chongqing Kange Biotechnology Co., LTD., and raised in the Experimental Animal Center of the First People’s Hospital of Zunyi City under standard conditions. All animal procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zunyi First People’s Hospital (Approval No. Lun Shen (2023)-2-283). The experiments were performed in accordance with the Chinese guidelines for Ethical Review of Laboratory Animal Welfare. Rabbits were randomly assigned to four groups: control group (no treatment), SCN group (SF/CS/nHA scaffold as a positive control), SCN-BM group (SF/CS/nHA scaffold implanted with BMSCs), SCN-BM-ICA group (SF/CS/nHA-ICA composite scaffold loaded with BMSCs). Rabbits were anesthetized via intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg), and secured on a surgical table in a supine position, and the surgical area on the left forelimb was shaved and disinfected. A longitudinal incision was made at the midshaft of the left radius, followed by sequential dissection of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle to fully expose the radius. A 15 mm critical-sized bone defect was created at the middle-lower radius using an oscillating bone saw. All groups received treatments according to their respective conditions: the control group received no implant, the SCN group received the SF/CS/nHA scaffold, the SCN-BM group received the SF/CS/nHA scaffold loaded with BMSCs, and the SCN-BM-ICA group received the SF/CS/nHA-ICA composite scaffold with BMSCs. After implantation, the wounds were sutured in layers, and penicillin was administered intramuscularly for three consecutive days to prevent infection. Euthanasia of rabbits was performed by intravenous overdose of sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg) at a predetermined time point, and the death of the animal was ultimately confirmed by cardiac and respiratory arrests and loss of reflexes.

3D Computed Tomography (CT) imaging

To evaluate bone regeneration and reconstruction, 3D CT (SOMATOM Definition AS, Siemens, Germany; Slice thickness: 0.3 mm) scans were performed on rabbits at weeks 4, 8, and 12 postoperatively after anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital. Bone regeneration at each time point was quantified using a modified Lane-Sandhu scoring system.

Histological staining

To further analyze bone tissue formation, 20 mm-long bone specimens were harvested from each group. Specimens were fixed in 4% PFA for 3 days. Fixed samples were decalcified in 5% ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-Na₂ solution (pH 7.0) for 2 months. After decalcification, the samples were dehydrated with absolute ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Then, Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) staining to evaluate tissue morphology. Masson’s Trichrome staining to assess collagen deposition and new bone formation. Stained sections were observed under a light microscope, and images were captured for further analysis. Bone regeneration was further quantified using the Lane-Sandhu histological scoring system.

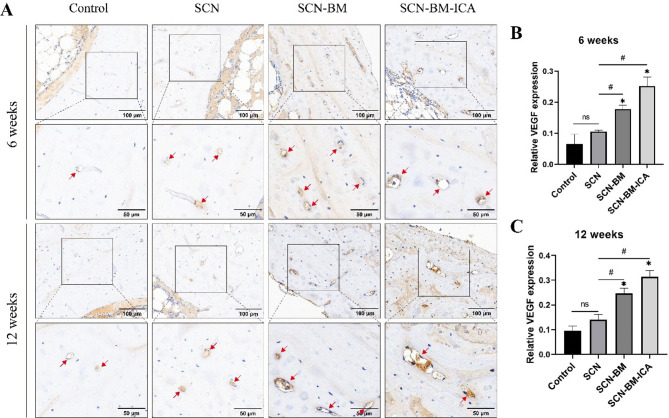

Expression of osteogenesis- and angiogenesis-related proteins IHC

To evaluate bone regeneration at the protein level, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed. Decalcified bone tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Sections were deparaffinized using an ethanol gradient. Sections were incubated in an antigen retrieval solution. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide solution. Non-specific binding was blocked using 3% BSA serum. VEGF (Proteintech, 19003-1-AP, 1:200 dilution) was incubated overnight at 4 °C. Sections were incubated with a secondary antibody at room temperature for 50 min. DAB chromogen was applied for visualization. Nuclei were counterstained. Sections were observed under a bright-field microscope, and images were captured for quantitative analysis.

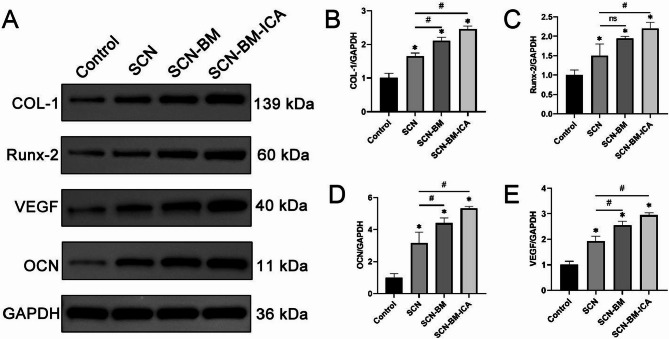

Western blotting was performed to quantify the expression of osteogenic and angiogenic proteins (Runx-2, COL-1, OCN, VEGF). Bone tissue samples were washed with PBS and cut into small pieces. Samples were lysed using RIPA buffer and homogenized. Lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged to collect total protein. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay. Samples were mixed with loading buffer, denatured by boiling, and separated via SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore, MA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C (see Table S2 for details). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Protein bands were visualized using chemiluminescence imaging, and quantitative analysis was performed.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 29.0 (IBM Crop., Armonk, NY, USA, Version 29.0)software. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Two-group comparisons were analyzed using the t-test. Multiple-group comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. If homogeneity of variance was met, the LSD test was used for post hoc comparisons. If variance was unequal, the Dunnett’s T3 test was applied. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

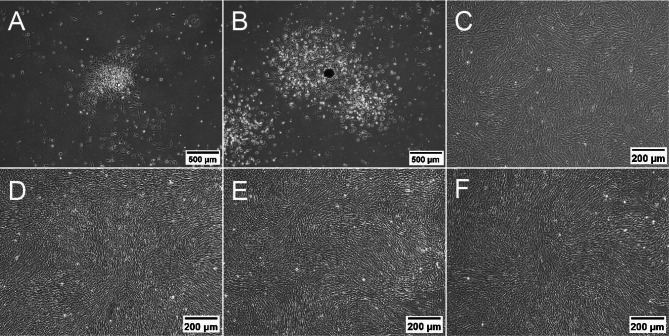

Morphology of BMSCs

Primary BMSCs were successfully isolated using the whole bone marrow adherence method. Small cell clusters were observed at day 1, but individual cell morphology was not clearly visible (Fig. 1A). Cells began to migrate outward from the clusters at day 3 exhibiting a spindle-shaped morphology (Fig. 1B). Then, cells proliferated rapidly and formed vortex-like clusters on day 10, almost covering the entire bottom of the culture flask (Fig. 1C). After Passaging (P1, P2, P3), cells predominantly displayed spindle-shaped, elongated spindle, or star-like morphologies, with larger cell bodies and smooth edges (Fig. 1D-F).

Fig. 1.

Morphological changes of BMSCs cultured at different time points (A: Day 1, B: Day 3, C: Day 10, D: Passage 1, E: Passage 2, F: Passage 3). Scale bars: 500 μm (A, B), 200 μm (C-F)

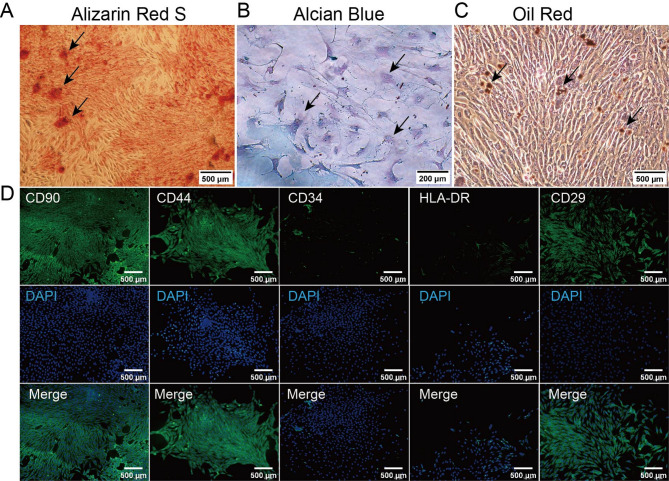

Identification of rabbit BMSCs

BMSCs were induced to differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages, followed by staining to confirm differentiation. After Alizarin Red staining, red mineralized nodules were observed, indicating successful osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 2A). The cytoplasm and extracellular matrix appeared blue or blue-green after Alcian Blue staining, confirming the presence of acidic glycosaminoglycans and the formation of chondrocytes (Fig. 2B). Intracellular and intercellular lipid droplets appeared yellow-brown or orange-red after Oil Red O staining, confirming successful adipogenic differentiation (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Identification of rabbit bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. A-C: Observation of BMSCs through Alizarin Red staining, Alcian Blue staining, and Oil Red O staining; D: Immunofluorescence detection of the expression of CD29, CD44, CD90, CD34, and HLA-DR in BMSCs. Scale bars: 500 μm (A, C, D), 200 μm (B)

BMSC immunofluorescence phenotyping showed that CD29, CD44, and CD90 exhibited strong green fluorescence, indicating positive expression. CD34 and HLA-DR showed no significant fluorescence signal, indicating negative or minimal expression (Fig. 2D). These results confirm that the isolated BMSCs highly express CD29, CD44, and CD90 but do not express CD34 or HLA-DR, which is characteristic of rabbit BMSCs. This confirms the successful isolation of high-purity BMSCs, suitable for further experiments.

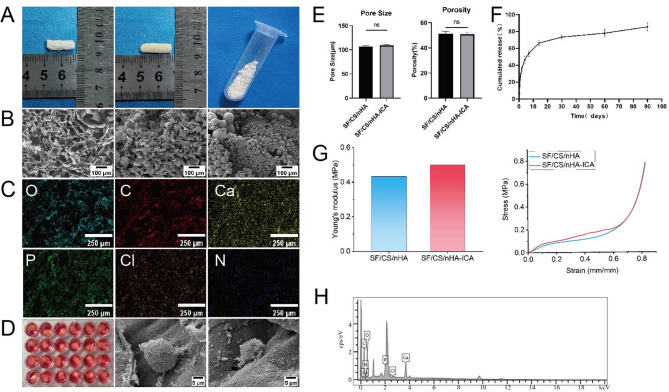

Characterization and in vitro release of ICA-loaded microspheres

SEM images revealed that the ICA-loaded microspheres exhibited a uniform spherical or near-spherical structure, and smooth surface with minor granulated structures and small pores, indicative of controlled release capability (Fig. 3A). Based on the ICA concentration-absorbance standard curve, the ICA microspheres demonstrated that drug loading efficiency was (29.38 ± 0.04)%, and encapsulation efficiency was (52.01 ± 0.09)%. These values indicate that ICA was efficiently encapsulated within the microspheres, ensuring stable release and effective bioactivity.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of scaffold composites, cell adhesion, and ICA in vitro release. A, B: Appearance and SEM images of SF/CS/nHA, SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffolds, and ICA slow-release microspheres; C, H: Energy-dispersive spectroscopy analysis of the SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffold; D: Culture of scaffold-cell complexes, SEM images of BMSCs in SF/CS/nHA and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffolds; E: Parameters related to SF/CS/nHA and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffolds; F: Release curve of ICA from microspheres; G: Young’s modulus and stress-strain curves of the SF/CS/nHA scaffold and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffold. Scale bars: 100 μm (B), 250 μm (C), 5 μm (D)

The cumulative ICA release profile (Fig. 3F) showed that burst release effect in the first 7 days, characterized by a rapid initial release. Then a gradual decrease in release rate over time, and cumulative release of 85.47% over 90 days, confirming the sustained release capability of the microspheres. SEM imaging confirmed that ICA-loaded microspheres were evenly distributed throughout the SF/CS/nHA scaffold (Fig. 3B), ensuring consistent ICA release during scaffold degradation.

Characterization of sf/cs/nha and sf/cs/nha-ICA scaffolds and cell adhesion

The SF/CS/nHA scaffold and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffold exhibited no significant differences in appearance. Both scaffolds were solid white cylindrical structures, with customizable sizes as needed. Their cut surfaces were smooth and even. After drying, the ICA-loaded microspheres appeared as a fine white powder visible to the naked eye (Fig. 3A). SEM revealed that nHA particles were evenly deposited on the SF/CS organic matrix. The internal pore distribution of both scaffolds was uniform, forming a stable 3D network structure suitable for cell adhesion and growth (Fig. 3B). The average pore size was (106.88 ± 1.50) µm (SF/CS/nHA) and (108.85 ± 2.09) µm (SF/CS/nHA-ICA). The average porosity was (51.40 ± 1.96)% (SF/CS/nHA) and (50.83 ± 1.61)% (SF/CS/nHA-ICA). There was no significant difference in pore size and porosity between the two scaffold groups (P > 0.05, Fig. 3E). The stress-strain curves of the SF/CS/nHA scaffold and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffold showed that as strain increased, stress also increased. Within a certain strain range, stress was proportional to strain. The elastic moduli of the SF/CS/nHA scaffold and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffold were 0.433 MPa and 0.501 MPa, respectively (Fig. 3G). These results indicate that both scaffolds exhibit certain compressive strength and can withstand a certain amount of external pressure.

Ion spectrum analysis confirmed that the main scaffold components were carbon (C) and oxygen (O), along with calcium (Ca) and phosphorus (P)—essential elements for bone mineralization (Fig. 3C, H). SEM imaging demonstrated that BMSCs adhered to the surface and pores of both SF/CS/nHA and SF/CS/nHA-ICA scaffolds. Cells displayed flattened or oval morphologies and proliferated in clusters. Filopodia formation was observed, and cells were surrounded by calcium phosphate crystals generated by nHA mineralization, confirming good cell adhesion and growth on the scaffolds (Fig. 3D).

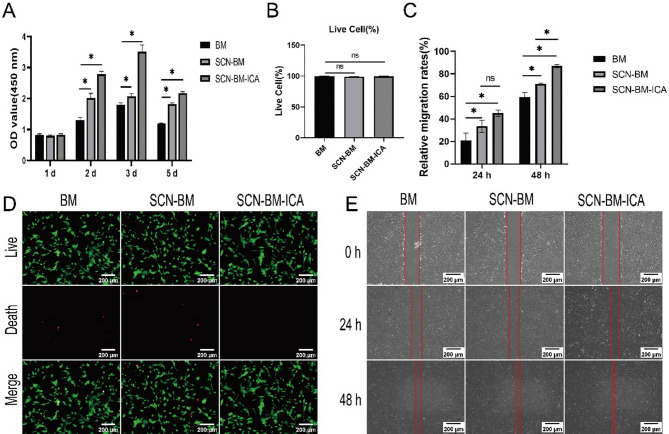

Proliferation, cytotoxicity, and migration of BMSCs on the scaffolds

On day 1, no significant difference in cell proliferation was observed among the groups (P > 0.05). On days 2, 3, and 5, the SCN-BM-ICA group exhibited a significantly higher proliferation rate compared to the other groups (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). All three groups contained a large number of live BMSCs, with only a small proportion of dead cells (Fig. 4D). The percentage of live cells were (92.3 ± 3.7)% (BM group), (89.5 ± 2.6)% (SCN-BM group), (94.7 ± 2.1)% (SCN-BM-ICA group). No statistically significant differences were observed between groups (P > 0.05, Fig. 4B), indicating that the scaffolds and ICA did not exhibit cytotoxic effects.

Fig. 4.

Study of BMSCs proliferation, toxicity, and migration ability on scaffolds. A: CCK-8 assay to assess the absorbance values of three groups to evaluate the proliferation ability of BMSCs after different treatments; B, D: Live/dead staining to detect the percentage of live cells in three groups; C, D: Wound healing assay to evaluate the migration ability of BMSCs in three groups at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h. *P < 0.05, Scale bars: 200 μm (D, E)

After 24 h of culture, all three groups exhibited significant cell migration compared to 0 h (P < 0.05), with no significant differences between groups. After 48 h, the SCN-BM-ICA group showed near-complete wound closure, with a significantly higher relative migration rate than the other two groups (P < 0.05). The SCN-BM group also exhibited a higher migration rate than the BM group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4C, E). These results suggest that the ICA-loaded microsphere 3D scaffold significantly enhances BMSC migration, more effectively than the other two groups.

Osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs

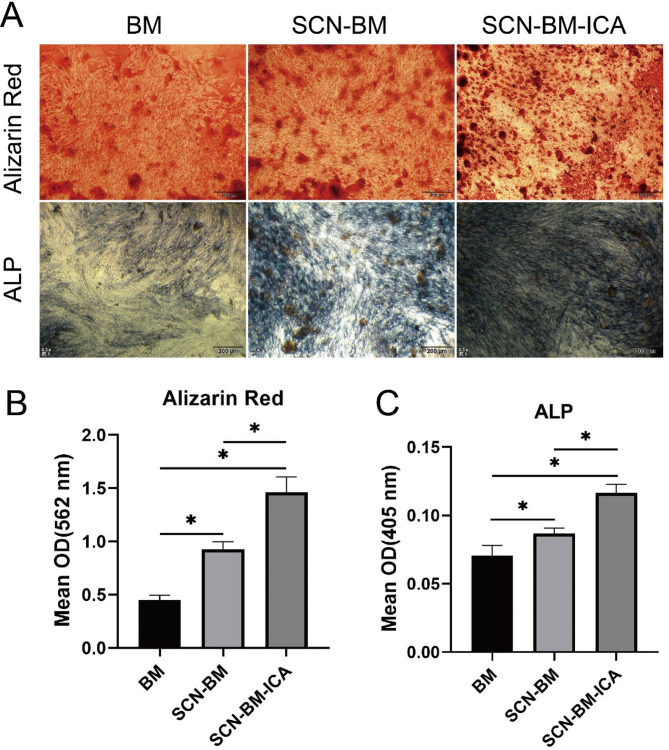

ALP and Alizarin red staining

ALP staining was used to assess early-stage osteogenic differentiation, while Alizarin Red staining was performed to evaluate late-stage mineralization of BMSCs. Microscopic observation revealed that the SCN-BM-ICA group exhibited more mineralized nodules and stronger dark brown staining compared to the other groups (Fig. 5A). Semi-quantitative analysis of Alizarin Red absorbance and ALP activity confirmed that the SCN-BM-ICA group showed significantly higher Alizarin Red absorbance and ALP activity than the other groups (P < 0.05). The SCN-BM group also exhibited significantly higher values than the BM group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

A: Alizarin Red staining and ALP staining in each group; B: Detection of Alizarin Red absorbance values at 562 nm using an ELISA reader; C: Detection of ALP absorbance values at 405 nm using an ELISA reader. *P < 0.05; Scale bars: 500 μm (Alizarin Red staining), 200 μm (ALP staining)

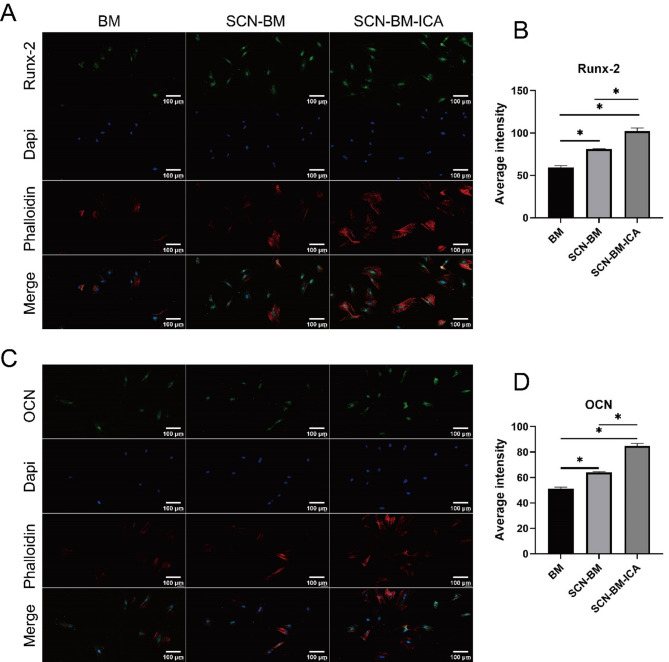

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed to detect early osteogenic marker Runx-2 and late osteogenic marker OCN in BMSCs. ImageJ semi-quantitative analysis revealed that after 7 days of osteogenic induction, Runx-2 fluorescence intensity was significantly higher in the SCN-BM-ICA group compared to the other two groups (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A, B). The SCN-BM group also showed a higher Runx-2 intensity than the BM group (P < 0.05). After 14 days of osteogenic induction, OCN fluorescence intensity followed the same trend, with the SCN-BM-ICA group showing the highest expression (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6C, D).

Fig. 6.

Expression of osteogenic-related proteins Runx-2 and OCN in various groups of BMSCs. A, B: Fluorescence and semi-quantitative analysis of Runx-2; C, D: Fluorescence and semi-quantitative analysis of OCN. *P < 0.05; Scale bars: 100 μm

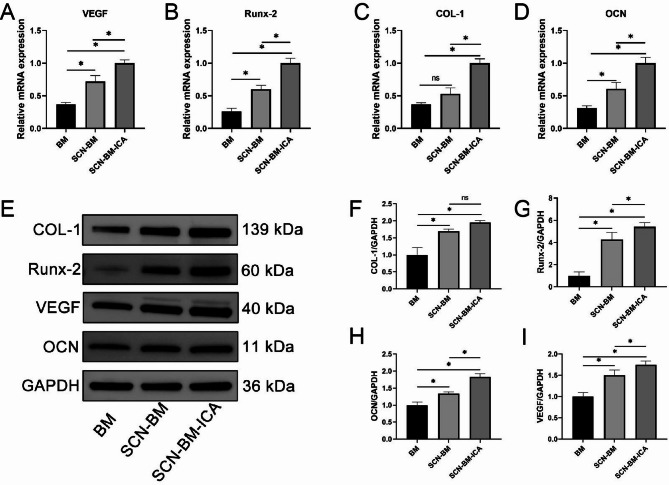

Osteogenesis- and angiogenesis-related gene and protein expression

To further analyze BMSC osteogenic differentiation, gene and protein expression levels were evaluated. Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis showed that the expression levels of Runx-2, OCN, COL-1, and VEGF were significantly higher in the SCN-BM-ICA group than in the other groups (Fig. 7A-D). The SCN-BM group also exhibited significantly higher expression levels than the BM group (P < 0.05). Western blotting results were consistent with RT-qPCR, confirming that the protein expression levels of Runx-2, OCN, COL-1, and VEGF followed the same trend (Fig. 7E-I).

Fig. 7.

Expression levels of osteogenic genes (Runx-2, COL-1, OCN) and angiogenic gene (VEGF) in terms of relative mRNA and protein on day 14 of osteoinduction in BMSCs. A-D: Relative mRNA expression of VEGF, Runx-2, COL-1, and OCN in each group; E: Representative protein Western blot bands for each group; F-I: Semi-quantitative statistical histograms for each protein. *P < 0.05

In vivo experiment

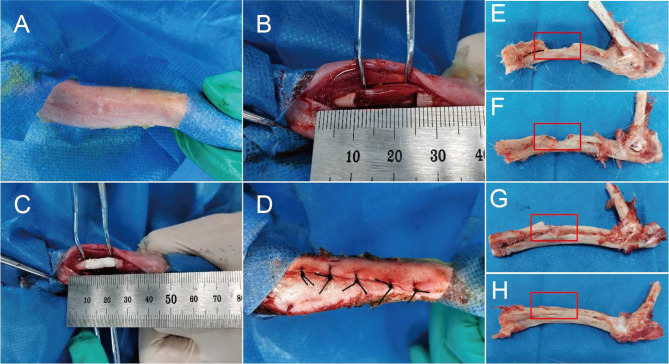

Gross morphological observation

All animals recovered well after surgery, with no infections or complications. The surgical procedure is shown in Fig. 8A-D. Macroscopic examination at 12 weeks post-surgery revealed that the control group exhibited a persistent bone defect (Fig. 8E). The SCN and SCN-BM groups showed partial bone repair but still had residual defects (Fig. 8F, G). The SCN-BM-ICA group displayed nearly complete bone regeneration, with the defect almost fully repaired (Fig. 8H).

Fig. 8.

Animal experiments with scaffold implantation in rabbit radial defects. A: Preparation of skin; B: Creation of a 1.5 cm radial defect; C: Implantation of scaffold composites; D: Suturing; E-H: Gross appearance of radial defect repair in the control group, SCN group, SCN-BM group, and SCN-BM-ICA group respectively at week 12

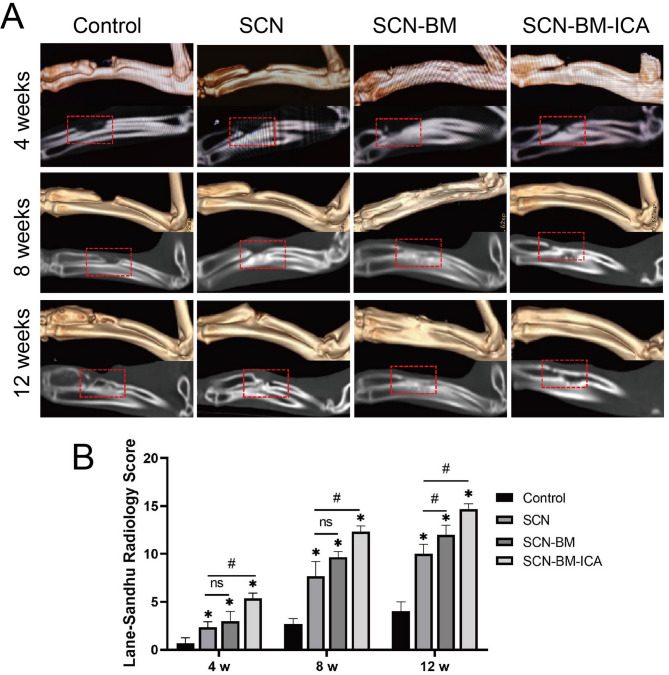

CT imaging analysis

CT scans were performed immediately post-surgery to confirm that the initial bone defect length was 15 mm in all groups. Follow-up CT scans at weeks 4, 8, and 12 were used to assess bone regeneration progress. At week 4, control group showed no obvious bone repair was observed. SCN and SCN-BM groups exhibited small amounts of new bone formation were observed at the defect margins. However, visible partial bone defect repair was observed in SCN-BM-ICA group. At week 8, control group showed only a small amount of new bone was detected at the edges of the defect. SCN and SCN-BM groups had new bone formation extended from the defect edges toward the center, but significant gaps remained. In SCN-BM-ICA group, the defect was largely filled with newly formed bone, and fracture healing was nearly complete, with only minor defects remaining. At week 12, control group performed a visible defect remained, with bone marrow cavity closure. In SCN group, some bone repair was observed, but the bone canal remained obstructed. In SCN-BM group, nearly healed, but cortical bone continuity was lower than in normal bone. However, bone healing was nearly complete, with bone marrow cavity restoration and continuous cortical bone, making it indistinguishable from normal bone in SCN-BM-ICA group (Fig. 9). 3D CT reconstruction and sagittal imaging of rabbit radial bone defects at weeks 4, 8, and 12 in each group.

Fig. 9.

Evaluation of bone defect repair in experimental rabbits at 4, 8, and 12 weeks using 3D CT. A: 3D reconstruction and sagittal images; B: Lane-Sandhu radiological scoring. compared to the Control group *P < 0.05, compared to the SCN group #P < 0.05

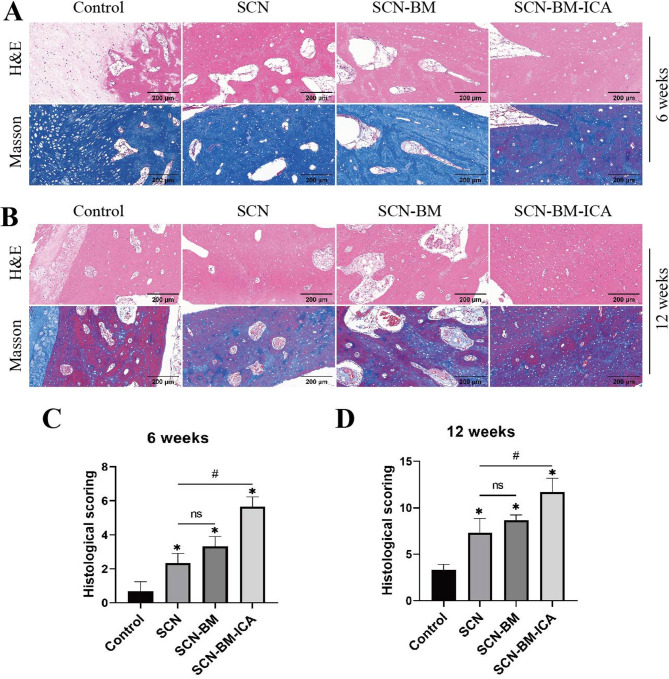

Histological analysis for the evaluation of new bone formation

At 6 and 12 weeks postoperatively, the experimental rabbits in each group were euthanized, and tissue samples were collected for histopathological analysis. H&E and Masson staining revealed that at 6 weeks post-surgery, the SCN, SCN-BM, and SCN-BM-ICA groups exhibited abundant collagen fiber formation around the bone defect, with some osteoblasts dispersed within the collagen fibers. In contrast, the blank control group showed only a small amount of collagen fibers and osteoblasts (Fig. 10A). The SCN-BM-ICA group displayed significantly more pronounced new bone formation than the SCN and SCN-BM groups, while no obvious new bone formation was observed in the blank control group. At both 6 and 12 weeks, the histological scores of the SCN-BM-ICA group were the highest, followed by the SCN-BM and SCN groups, which had higher scores than the control group (Fig. 10C, D). Compared with the 6-week time point, the SCN-BM-ICA group exhibited more extensive new bone tissue at 12 weeks, accompanied by a greater number of newly formed blood vessels (Fig. 10B). Immunohistochemical analysis further demonstrated that the SCN-BM-ICA group had the highest in vivo expression of VEGF (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10.

Evaluation of new bone formation in the bone defect areas of experimental rabbits in different groups using H&E and Masson staining. A: H&E and Masson staining at 6 weeks post-operation; B: H&E and Masson staining at 12 weeks post-operation; C: Histopathological scoring of the bone defects in each group at 6 weeks and 12 weeks. compared to the Control group *P < 0.05, compared to the SCN group #P < 0.05; Scale bars: 200 μm

Fig. 11.

Immunohistochemical detection of VEGF to assess angiogenesis in the bone defect areas of experimental rabbits in different groups at 6 weeks and 12 weeks. compared to the Control group *P < 0.05; compared to the SCN group #P < 0.05; Scale bars: 100 μm and 50 μm

Osteogenesis- and angiogenesis-related gene and protein expression

At 12 weeks post-operatively, tissue samples were collected from all groups for Western blot analysis to evaluate the expression of osteogenic marker genes (COL-1, Runx-2, OCN) and the angiogenic factor VEGF in the bone regeneration area. The results showed a progressive increase in the expression levels of these proteins across groups, with the SCN-BM-ICA group exhibiting the most significant upregulation of both osteogenic and angiogenic proteins (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Protein expression levels of osteogenic and angiogenic marker genes in the bone regeneration areas of different groups at 12 weeks post-operation. A: Western blot detection of COL-1, Runx-2, OCN, and VEGF protein expressions in the bone regeneration areas of each experimental group; B-E: Semi-quantitative statistical histograms of each protein. compared to the Control group *P < 0.05; compared to the SCN group #P < 0.05

Discussion

The treatment of critical bone defects remains a significant challenge in bone regeneration medicine [32]. Although numerous studies have attempted to repair bone defects using tissue-engineered scaffolds combined with growth factors or stem cells, clinical translation has been slow due to issues such as the uncontrollable mechanical properties and stability of materials, immune responses triggered by exogenous proteins, and the uncontrollable doses of growth factors. In recent years, organic-inorganic biomimetic scaffolds constructed from natural materials have attracted widespread attention due to their excellent biocompatibility and mechanical adaptability. Natural polymers such as CS, collagen, and SF have been shown to possess good biodegradability and cell affinity [33]. When combined with nHA, composite scaffolds provide ideal support for bone repair. ICA, an extract of traditional Chinese medicine, has advantages such as easy accessibility, low preparation costs, and potential osteogenic and angiogenic properties [34]. Combining biomimetic bone scaffolds with ICA could have significant clinical translation potential. In this study, ICA and BMSCs were co-loaded into SF/CS/nHA scaffolds, successfully creating a new scaffold composite material. Through a series of in vivo and in vitro experiments, we found that this composite material significantly promotes osteogenesis and the formation of new blood vessels.

The SF/CS/nHA biomimetic composite scaffold compensates for some of the shortcomings of individual SF, CS, and nHA scaffolds [23]. Specifically, SF lacks bone conduction and mineralization capabilities, as well as inherent bone-inductive activity. CS alone has relatively weak mechanical strength and limited stability under physiological conditions, making it unsuitable for supporting the regeneration needs of large bone defect areas. nHA, as the main inorganic component of bone tissue, has good bone-conductive and mineralization-inducing properties; however, it is brittle and lacks flexibility and processability, limiting its use in constructing complex three-dimensional scaffolds. Additionally, bioactive agents are crucial for the effectiveness of tissue engineering technologies. Jing et al. developed bio-glass incorporating ICA, which significantly induced new bone formation and angiogenesis in rat bone defect models [35]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that ICA-modified antler-derived cancellous bone scaffolds (CACB) significantly enhanced osteogenic differentiation in rat BMSCs, as evidenced by the upregulation of key osteogenic marker genes, such as ALP and OCN [36]. However, the application of ICA in bone regeneration scaffolds has not been extensively studied.

In this study, based on the previously constructed SF/CS/nHA biomimetic composite scaffold, we further developed a drug delivery system with sustained release of ICA by using PLGA microspheres, vacuum freeze-drying technology, and chemical crosslinking methods. This successfully created an SF/CS/nHA-ICA composite scaffold with sustained-release functionality. Generally, the porosity of biological scaffolds ranges from 50 to 90%, and the pore size is typically between 100 and 300 μm, which ensures a balance between cell growth, angiogenesis, and mechanical support [37, 38]. The drug-release scaffold developed in this study meets these standards. Specifically, the average pore size of the SF/CS/nHA-ICA composite scaffold was (108.85 ± 2.09) µm, with an average porosity of (50.83 ± 1.61)%, and it contained essential inorganic elements, such as Ca and P, similar to the osteogenic microenvironment. The average elastic modulus of SF/CS/nHA-ICA is 0.501 MPa, which still differs from that of natural bone tissue in terms of mechanical properties. However, it is consistent with the mechanical range reported for non-load-bearing bone repair or guided bone regeneration materials [23, 39, 40]. Ji et al. loaded biologically active Salvianolic acid B (Sal B) onto CS/HA scaffolds (Sal B-CS/HA), where the elastic modulus decreased from 34.3 kPa to 25.2 kPa. However, in vitro and in vivo experimental results showed that the osteogenic differentiation and angiogenesis in the Sal B-CS/HA group were significantly higher than in the CS/HA group [41]. These studies indicate that the elastic modulus of the scaffold is not the sole factor affecting the bone defect repair outcome. Other factors such as scaffold microstructure design, porosity, degradation rate, and biocompatibility may also play important roles in bone repair. Additionally, the osteogenic activity of ICA may compensate for the mechanical limitations by accelerating new bone formation. Therefore, it can be concluded that the SF/CS/nHA-ICA composite scaffold meets the requirements for bone tissue engineering scaffolds in terms of both physical properties and composition.

Cell adhesion, growth status, proliferation rate, and migration ability are key parameters for evaluating the biocompatibility of biomimetic scaffold materials. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations revealed that the ICA microspheres on the composite scaffold were spherical with varying diameters. Under high magnification, small pores were visible on the surface of the microspheres, providing release channels for sustained action of ICA. BMSCs adhered to the surface and pores of the scaffold, adopting a flattened or oval shape, growing in clusters, forming pseudopodia, and being surrounded by calcium salt crystals formed by nHA. These results indicate that the scaffold has the ability to promote cell adhesion and form relatively stable cell-scaffold complexes. The calcium salt crystals observed around the cells suggest osteogenic differentiation of stem cells, indicating that SF/CS/nHA has some osteoinductive potential. CCK-8 assay results showed that the SF/CS/nHA-ICA composite scaffold exhibited no significant cytotoxicity to BMSCs and continuously promoted cell proliferation over 1, 4, and 7 days. The SCN-BM-ICA group showed significantly higher cell viability than other groups (P < 0.05). Previous studies have indicated that scaffolds loaded with ICA positively affect stem cell morphology and proliferation [30]. Live/dead cell staining further confirmed that the SCN-BM-ICA group primarily exhibited green fluorescence (live cells), with almost no red fluorescence (dead cells). The cell migration experiment showed that the SCN-BM-ICA group was able to cover the scratch area in less time compared to the other two groups (P < 0.05). This indicates that the scaffold material has good biocompatibility and cell support ability, and demonstrates strong potential in promoting cell migration.

The continuous osteoinductive properties of the scaffold throughout the entire process are a prerequisite for its widespread application in bone repair. ALP is one of the early indicators of osteogenic differentiation. Calcium nodules are a significant feature of late-stage osteogenesis. ALP and Alizarin Red S staining results showed that the mineralization degree of the SCN-BM-ICA group was higher than that of the other two groups (P < 0.05), and the mineralization degree of the SCN-BM group was significantly higher than that of the BM group (P < 0.05). This suggests that the sustained release of ICA can promote osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in both the early and late stages. Moreover, the blank SF-CS-nHA scaffold itself also has some osteoinductive effects on BMSCs, but the osteogenic effect is more significant when ICA is added. Immunofluorescence staining results showed that Runx-2 and OCN were strongly expressed in BMSCs from the SCN-BM-ICA group, indicating that the osteogenic differentiation process was fully activated. Western blotting analysis further revealed that by day 14 of cell culture, the SCN-BM-ICA group exhibited the highest expression levels of osteogenic and angiogenic-related proteins, including Runx-2, OCN, COL-1, and VEGF, which were significantly higher than those in the other two groups (P < 0.05). This suggests that the osteogenic induction effects of ICA and the SF-CS-nHA scaffold may be synergistic. Additionally, RT-qPCR analysis further confirmed the expression patterns of these proteins, aligning with the Western blotting results. Based on these findings, we speculate that ICA can simultaneously induce both osteogenesis and vascularization, consistent with previous research findings [27].

Furthermore, we established a rabbit radial bone defect model to investigate whether the SCN-BM-ICA composite material could effectively promote the repair of critical-sized bone defects and to explore its potential molecular mechanisms. CT imaging results showed that at weeks 4, 8, and 12 post-surgeries, the SCN-BM-ICA group exhibited superior bone defect repair compared to the other two groups (P < 0.05). By week 12, the bone defect was completely healed, with bone density approaching normal levels, whereas the other groups displayed significantly poorer bone regeneration (P < 0.05). H&E staining and Masson’s trichrome staining further revealed that in the presence of ICA, the scaffold integrated well with the bone tissue. Most of the scaffold had effectively degraded and was replaced by newly formed bone tissue, characterized by abundant trabecular bone and newly formed blood vessels. Local vascularization occurred throughout the entire process of bone repair and reconstruction, improving blood circulation, delivering nutrients to the regenerating bone tissue and cells, and ultimately accelerating bone repair [42]. Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the SCN-BM-ICA group exhibited the highest VEGF expression in vivo, and a greater number of new blood vessels were observed in the surrounding newly formed bone tissue. These findings suggest that ICA plays a dual role in guiding bone regeneration and promoting local angiogenesis, which may be one of its unique advantages. To gain a more precise understanding of the molecular changes during bone regeneration, we collected tissue samples from the defect site at week 12 post-surgery and analyzed the expression of key osteogenic and angiogenic markers using Western blotting. The results demonstrated that the SCN-BM-ICA group exhibited a significant upregulation of osteogenic markers (COL-1, Runx-2, OCN) as well as the angiogenic factor VEGF (P < 0.05), indicating that this composite material effectively promoted osteoblast differentiation and bone matrix formation, thereby accelerating new bone formation. Moreover, the marked upregulation of VEGF expression in the SCN-BM-ICA group further confirmed the crucial role of angiogenesis in bone repair, suggesting that enhanced vascularization provided an optimal microenvironment and sufficient blood supply for new bone growth.

However, there are some other limitations in our experiments. First, we primarily focused on the effect of the SF/CS/nHA scaffold as a positive control. Future studies may consider incorporating autologous bone grafts or commercial hydroxyapatite-based materials as another important reference to further enrich and refine the experimental design. Second, We mainly used in vitro experiments to evaluate the release profiles of ICA and lacked in vivo drug release kinetic data. In the future, techniques such as isotope tracing or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) can be used to monitor the metabolism, distribution, and bioavailability of ICA in animals to optimize drug release strategies. Third, the relatively small sample size of the animal experiments as well as the short study period could be expanded, and the observation time could be extended in the future to validate the results of this study. In addition, the release mechanism of ICA in vivo and its regulation of osteogenic signaling pathways (e.g., BMP/Smad, Wnt/β-catenin) still need to be further investigated, in order to obtain more comprehensive and reliable data, and to provide stronger support for the clinical translation of bone tissue engineering materials.

Conclusion

In this study, we describe the preparation of an SF/CS/nHA composite scaffold loaded with ICA. The pharmacological activity of ICA in the prepared scaffold material and the properties of the composite scaffold did not change significantly. In vitro and in vivo experiments confirmed that the scaffold composite could promote the repair of critical bone defects in rabbit radius by up-regulating genes and proteins of osteogenic differentiation and angiogenesis. Combining ICA with SF/CS/nHA scaffolds has the advantages of low price and a simple preparation and sterilization process, which has great potential in the research and application of bone tissue engineering.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ALP

Alkaline Phosphatase

- BCA

Bicinchoninic Acid Assay

- BMSCs

Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells

- BSA

Bovine Serum Albumin

- C

Carbon

- Ca

Calcium

- CD29

Cluster of Differentiation 29

- CD34

Cluster of Differentiation 34

- CD44

Cluster of Differentiation 44

- CD90

Cluster of Differentiation 90

- cDNA

Complementary DNA

- Cl

Chlorine

- COL-1

Type I collagen

- CPC

Cetylpyridinium chloride

- CS

Chitosan

- CT

Computed Tomography

- DAPI

4’,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- EDTA

Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid

- FBS

Fetal Bovine Serum

- H&E

Hematoxylin & Eosin

- HLA-DR

Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR

- ICA

Icariin

- IHC

Immunohistochemical

- nHA

Nano-Hydroxyapatite

- O

Oxygen

- OCN

Osteocalcin

- P

Phosphorus

- P1

Passage 1

- P2

Passage 2

- P3

Passage 3

- PBS

Phosphate-Buffered Saline

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- PFA

Paraformaldehyde

- PLGA

Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- PVA

Polyvinyl Alcohol

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene Fluoride

- RIPA

Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay Buffer

- RNA

Ribonucleic Acid

- RT-qPCR

Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR

- Runx-2

Runt-related Transcription Factor 2

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

- SEM

Scanning Electron Microscopy

- SF

Silk Fibroin

- VEGF

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

Author contributions

J. D., Z.-H. Z., and D.-S. J. conceived and designed the whole study; D.-S. J. and Z.-H. Z. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; Y. W. and R.-Y. T. contributed to the experiments; S.-Q. R. and W.-L.H. secured funding; Z.-H. Z. and D.-S. J. wrote the original version of this paper, they are first authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project [Qian Ke He Ji Chu-ZK[2021]-387, Qian Ke He Ji Chu-ZK[2021]-393], Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project [Qian Ke He Cheng Guo-LC[2022]029, Qian Ke He Cheng Guo-LC[2024]019], Zunyi Science and Technology Bureau (HZ-2024-7).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zunyi First People’s Hospital (Approval No. Lun Shen (2023)-2-283). The experiments were performed in accordance with the Chinese guidelines for Ethical Review of Laboratory Animal Welfare.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dong-Sheng Jin and Zhang-Hong Zhao are first authors.

Refferences

- 1.Zhang S, Liu Y, Ma Z, Gao S, Chen L, Zhong H, Zhang C, Li T, Chen W, Zhang Y, et al. Osteoking promotes bone formation and bone defect repair through ZBP1-STAT1-PKR-MLKL-mediated necroptosis. Chin Med. 2024;19(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tam WL, Freitas Mendes L, Chen X, Lesage R, Van Hoven I, Leysen E, Kerckhofs G, Bosmans K, Chai YC, Yamashita A, et al. Human pluripotent stem cell-derived cartilaginous organoids promote scaffold-free healing of critical size long bone defects. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falacho RI, Palma PJ, Marques JA, Figueiredo MH, Caramelo F, Dias I, Viegas C, Guerra F. Collagenated Porcine heterologous bone grafts: histomorphometric evaluation of bone formation using different physical forms in a rabbit cancellous bone model. Molecules 2021, 26(5):1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Lv Z, Ji Y, Wen G, Liang X, Zhang K, Zhang W. Structure-optimized and microenvironment-inspired nanocomposite biomaterials in bone tissue engineering. Burns Trauma. 2024;12:tkae036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh WT, Yang YS, Xie J, Ma H, Kim JM, Park KH, Oh DS, Park-Min KH, Greenblatt MB, Gao G, et al. WNT-modulating gene silencers as a gene therapy for osteoporosis, bone fracture, and critical-sized bone defects. Mol Therapy: J Am Soc Gene Therapy. 2023;31(2):435–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillman CE, Jayasuriya AC. FDA-approved bone grafts and bone graft substitute devices in bone regeneration. Materials science & engineering C, Materials for biological applications 2021, 130:112466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Visscher DO, Farré-Guasch E, Helder MN, Gibbs S, Forouzanfar T, van Zuijlen PP, Wolff J. Advances in Bioprinting technologies for craniofacial reconstruction. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34(9):700–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granchi D, Savarino LM, Ciapetti G, Baldini N. Biological effects of metal degradation in hip arthroplasties. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2018;48(2):170–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Jiang W, Xie C, Wu X, Ren Q, Wang F, Shen X, Hong Y, Wu H, Liao Y, et al. Msx1(+) stem cells recruited by bioactive tissue engineering graft for bone regeneration. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou B, Jiang X, Zhou X, Tan W, Luo H, Lei S, Yang Y. GelMA-based bioactive hydrogel scaffolds with multiple bone defect repair functions: therapeutic strategies and recent advances. Biomaterials Res. 2023;27(1):86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long J, Yao Z, Zhang W, Liu B, Chen K, Li L, Teng B, Du XF, Li C, Yu XF, et al. Regulation of osteoimmune microenvironment and osteogenesis by 3D-Printed plag/black phosphorus scaffolds for bone regeneration. Adv Sci (Weinheim Baden-Wurttemberg Germany). 2023;10(28):e2302539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sivasankar MV, Chinta ML, Sreenivasa Rao P. Zirconia based composite scaffolds and their application in bone tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;265(Pt 1):130558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song T, Zhao F, Wang Y, Li D, Lei N, Li X, Xiao Y, Zhang X. Constructing a biomimetic nanocomposite with the in situ deposition of spherical hydroxyapatite nanoparticles to induce bone regeneration. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9(10):2469–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang W, Ni W, Yu C, Gu T, Ye L, Sun R, Ying X, Yik JHN, Haudenschild DR, Yao S, et al. Biomimetic bone-Like composite hydrogel scaffolds composed of collagen fibrils and natural hydroxyapatite for promoting bone repair. ACS Biomaterials Sci Eng. 2024;10(4):2385–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoveidaei AH, Sadat-Shojai M, Mosalamiaghili S, Salarikia SR, Roghani-Shahraki H, Ghaderpanah R, Ersi MH, Conway JD. Nano-hydroxyapatite structures for bone regenerative medicine: Cell-material interaction. Bone. 2024;179:116956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng J, Xiong S, Zhou J, Wei P, Guo K, Wang F, Ouyang M, Long Z, Yao A, Li J, et al. Hollow hydroxyapatite microspheres loaded with rhCXCL13 to recruit BMSC for osteogenesis and synergetic angiogenesis to promote bone regeneration in bone defects. Int J Nanomed. 2023;18:3509–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang K, Liu Y, Zhao Z, Shi X, Zhang R, He Y, Zhang H, Wang W. Magnesium-Doped Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan composite hydrogel: Preparation and characterization. Int J Nanomed. 2024;19:651–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaikh S, Gupta S, Mishra A, Sheikh PA, Singh P, Kumar A. Laser-assisted synthesis of nano-hydroxyapatite and functionalization with bone active molecules for bone regeneration. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2024;237:113859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo J, Yang B, Ma Q, Fometu SS, Wu G. Photothermal Regenerated Fibers with Enhanced Toughness: Silk Fibroin/MoS(2) Nanoparticles. Polymers 2021, 13(22):3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Hassan MA, Basha AA, Eraky M, Abbas E, El-Samad LM. Advancements in silk fibroin and silk sericin-based biomaterial applications for cancer therapy and wound dressing formulation: A comprehensive review. Int J Pharm. 2024;662:124494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fakhri E, Eslami H, Maroufi P, Pakdel F, Taghizadeh S, Ganbarov K, Yousefi M, Tanomand A, Yousefi B, Mahmoudi S, et al. Chitosan biomaterials application in dentistry. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;162:956–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petroni S, Tagliaro I, Antonini C, D’Arienzo M, Orsini SF, Mano JF, Brancato V, Borges J, Cipolla L. Chitosan-Based biomaterials: insights into chemistry, properties, devices, and their biomedical applications. Mar Drugs 2023, 21(3):147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Xiao H, Huang W, Xiong K, Ruan S, Yuan C, Mo G, Tian R, Zhou S, She R, Ye P, et al. Osteochondral repair using scaffolds with gradient pore sizes constructed with silk fibroin, chitosan, and nano-hydroxyapatite. Int J Nanomed. 2019;14:2011–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qi XN, Mou ZL, Zhang J, Zhang ZQ. Preparation of chitosan/silk fibroin/hydroxyapatite porous scaffold and its characteristics in comparison to bi-component scaffolds. J Biomedical Mater Res Part A. 2014;102(2):366–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui J, Lin L, Hao F, Shi Z, Gao Y, Yang T, Yang C, Wu X, Gao R, Ru Y, et al. Comprehensive review of the traditional uses and the potential benefits of epimedium folium. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1415265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z, Wang D, Yang D, Zhen W, Zhang J, Peng S. The effect of Icariin on bone metabolism and its potential clinical application. Osteoporos International: J Established as Result Cooperation between Eur Foundation Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Foundation USA. 2018;29(3):535–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y, Xia L, Zhou Y, Ma W, Zhang N, Chang J, Lin K, Xu Y, Jiang X. Evaluation of osteogenesis and angiogenesis of Icariin loaded on micro/nano hybrid structured hydroxyapatite granules as a local drug delivery system for femoral defect repair. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3(24):4871–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang S, Zhang X, Liao X, Ding Y, Gan J. Icariin regulates RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation via the ERα/c-Src/RANK signaling. Biomedical Mater (Bristol England) 2024, 19(2). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Hsieh TP, Sheu SY, Sun JS, Chen MH. Icariin inhibits osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption by suppression of MAPKs/NF-κB regulated HIF-1α and PGE(2) synthesis. Phytomedicine: Int J Phytotherapy Phytopharmacology. 2011;18(2–3):176–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao H, Tang J, Zhou D, Weng Y, Qin W, Liu C, Lv S, Wang W, Zhao X. Electrospun Icariin-Loaded Core-Shell collagen, polycaprolactone, hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds for the repair of rabbit tibia bone defects. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:3039–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M, Gu Q, Chen M, Zhang C, Chen S, Zhao J. Controlled delivery of Icariin on small intestine submucosa for bone tissue engineering. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;71:260–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S, Rahaman KA, Kim YC, Jeon H, Han HS. Fostering tissue engineering and regenerative medicine to treat musculoskeletal disorders in bone and muscle. Bioactive Mater. 2024;40:345–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JW, Han YS, Lee HM, Kim JK, Kim YJ. Effect of morphological characteristics and biomineralization of 3D-Printed gelatin/hyaluronic acid/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds on bone tissue regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22(13):6794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Zhang X, Liu T, Huang Y, Wismeijer D, Liu Y. Icariin: does it have an osteoinductive potential for bone tissue engineering? Phytother Res. 2014;28(4):498–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jing X, Yin W, Tian H, Chen M, Yao X, Zhu W, Guo F, Ye Y. Icariin doped bioactive glasses seeded with rat adipose-derived stem cells to promote bone repair via enhanced osteogenic and angiogenic activities. Life Sci. 2018;202:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Xu M, Song L, Wei Y, Lin Y, Liu W, Heng BC, Peng H, Wang Y, Deng X. Effects of compatibility of deproteinized antler cancellous bone with various bioactive factors on their osteogenic potential. Biomaterials. 2013;34(36):9103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prananingrum W, Naito Y, Galli S, Bae J, Sekine K, Hamada K, Tomotake Y, Wennerberg A, Jimbo R, Ichikawa T. Bone ingrowth of various porous titanium scaffolds produced by a moldless and space holder technique: an in vivo study in rabbits. Biomedical Mater (Bristol England). 2016;11(1):015012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murphy CM, Haugh MG, O’Brien FJ. The effect of mean pore size on cell attachment, proliferation and migration in collagen-glycosaminoglycan scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31(3):461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Z, Wang T, Zhang L, Luo Y, Zhao J, Chen Y, Wang Y, Cao W, Zhao X, Lu B, et al. Metal-Phenolic Networks-Reinforced extracellular matrix scaffold for bone regeneration via combining Radical-Scavenging and Photo-Responsive regulation of microenvironment. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13(15):e2304158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Y, Deng G, She H, Bai F, Xiang B, Zhou J, Zhang S. Polydopamine-coated biomimetic bone scaffolds loaded with exosomes promote osteogenic differentiation of BMSC and bone regeneration. Regenerative Therapy. 2023;23:25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ji C, Bi L, Li J, Fan J. Salvianolic acid B-Loaded chitosan/hydroxyapatite scaffolds promotes the repair of segmental bone defect by angiogenesis and osteogenesis. Int J Nanomed. 2019;14:8271–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geng Y, Duan H, Xu L, Witman N, Yan B, Yu Z, Wang H, Tan Y, Lin L, Li D, et al. BMP-2 and VEGF-A ModRNAs in collagen scaffold synergistically drive bone repair through osteogenic and angiogenic pathways. Commun Biology. 2021;4(1):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.