Abstract

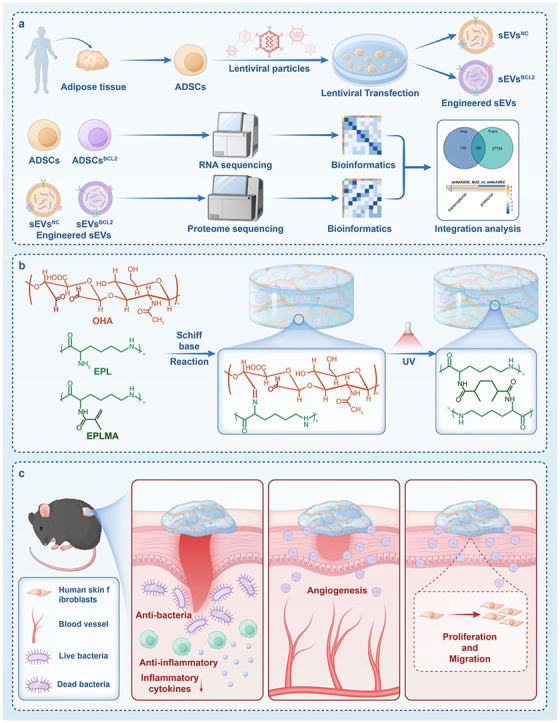

Diabetic wound healing remains a major clinical challenge owing to impaired angiogenesis, prolonged inflammation, and bacterial infection. Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) offer a promising solution for improving diabetic wound healing. The biological activity of EVs can be increased by engineering modifications. Antimicrobial hydrogel dressings combined with bioengineered EVs, will provide a good solution to the problem of difficult healing of diabetic wounds. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the potential of BCL-2-engineered EVs to enhance wound healing in a diabetic mouse model. BCL-2 engineered adipose mesenchymal stem cells were constructed using the lentiviral embedding method, and analyzed their transcriptional changes through transcriptome sequencing. Their secreted EVs were isolated and characterized by proteomic sequencing. Integrating bioinformatics analysis, we found that BCL-2 engineered EVs may play a powerful role in angiogenesis and tissue repair. Furthermore, we developed an antimicrobial hydrogel based on epsilon-poly-lysine and hyaluronic acid to encapsulate them. The hydrogel-EVs system demonstrated a comprehensive promotion of wound healing, including increased angiogenesis, enhanced cell proliferation, reduced inflammation, and improved tissue architecture. These findings highlighted the potential of BCL-2-engineered EV-loaded antimicrobial hydrogels as a novel strategy for managing diabetic wounds, providing a promising alternative to overcome the limitations of current therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: BCL-2, Extracellular vesicles, Diabetic wound, Antimicrobial hydrogel, Angiogenesis

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Chronic wounds, particularly those caused by diabetes, pose a substantial challenge to healthcare owing to their delayed healing, heightened susceptibility to infections, and frequent recurrence [1]. Diabetic wounds are marked by impaired angiogenesis, chronic inflammation, and diminished regenerative capacity, often resulting in severe complications such as amputations [[1], [2], [3]]. However, despite progress in wound care technologies and therapies, there remains a significant gap in effective treatment that ensures complete and lasting healing. One of the major causes of poor treatment results is due to disturbances in the local microenvironment, such as abnormal immune cell infiltration, oxidative stress, excessive inflammatory response, and bacterial infection [4,5]. The development of novel biomaterial dressings for diabetic wounds is important for the management and treatment of diabetic wounds due to the pathological microenvironment of high glucose, which often leads to chronic oxidative stress in the cells, which in turn affects the function of the surrounding cells, as well as leading to bacterial infections [6].

Studies show extracellular vesicles (EVs), particularly those derived from stem cells, as novel therapeutic agents owing to their ability to regulate key cellular processes involved in wound healing [[7], [8], [9]]. EVs are membrane-bound particles secreted by various cell types, capable of transferring bioactive molecules such as proteins, lipids, and RNA to recipient cells [10]. Compared to sources such as bone marrow or embryonic tissues, adipose tissue is more readily accessible, with substantial quantities of waste fat easily obtainable through liposuction [11]. This accessibility makes adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) an excellent source of EVs [12]. Furthermore, EVs derived from ADSCs show considerable potential as effective candidates for treating diabetic wound [7,13]. However, the isolation of EVs requires large amounts of cell supernatant as well as ultracentrifugation techniques, greatly limiting their clinical translation. Enhancing their yield or boosting their biological activity at the same concentration are promising pathways to address the clinical translation of EVs.

Engineered EVs are artificially modified and optimized to enhance their therapeutic potential, and they can also play a powerful role in the abnormal microenvironment of diabetic wounds [14]. These modifications are achieved through techniques such as surface modification, content loading, membrane engineering, fusion processes, and the use of genetically engineered cell sources [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]]. Such strategies can significantly improve the targeting capabilities and biological activities of EVs, making them highly attractive in the field of regenerative medicine. Developing efficient engineered EVs is important for advancing diabetic wound healing and achieving clinical translation [[15], [16], [17]]. Gene editing technology, such as CRISPR/Cas9 and lentiviral vectors, enables precise genetic modifications in cells, which can then be cultured and expanded in vitro to produce EVs sustainably. This approach facilitates large-scale and standardized EVs production, addressing key challenges in translational medicine [20,21].

Studies have shown numerous pro-survival signals converge on the BCL-2 pathway, with BCL-2 serving as a key member of the pro-survival family [22,23]. BCL-2 overexpression could enhance cell survival and suppress apoptosis, even in the absence of cytokines [24,25]. Under conditions of tissue injury, the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 plays a vital role in promoting repair by suppressing mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis [[24], [25], [26]]. It protects structural and stem cells from oxidative stress and inflammation-induced cell death, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis and tissue integrity [26]. Its expression in stem cells also prolongs viability and strengthens differentiation capacity, ultimately contributing to improved tissue regeneration [27].

Although researchers have focused on the important role of BCL-2 in regulating apoptosis, recent findings reveal that cells overexpressing BCL-2 exhibit an increased capacity to secrete growth factors, especially angiogenesis-related growth factors [[28], [29], [30]]. This suggests that BCL-2 plays an important role in promoting tissue repair and regeneration. However, previous studies have focused mainly on the changes in the stem cells themselves, and nothing is known about their specific mechanisms. Since EVs are important tools for intercellular communication, we hypothesized that BCL-2 enhances the growth factor activity of stem cells and then acts on other cells through EVs. For this purpose, we will construct BCL-2 engineered ADSCs using lentiviral vectors and isolate their secreted EVs to study their compositional alterations. We hypothesize that BCL-2-engineered extracellular vesicles (EVsBCL−2) possess enhanced biological activity and present a promising tool for treating diabetic wounds.

It is important to note that EVs often do not have antimicrobial activity to deal with bacterial infections in diabetic wounds. At the same time, EVs alone tend not to be able to stay localized in the wound for a long time with a high clearance rate [31]. Selection of suitable carriers effectively loaded with EVs and providing certain antibacterial effects can achieve better healing of diabetic wounds [9,32]. Hydrogels have gained significant attention in wound repair research owing to their three-dimensional porous structure, ability to retain moisture, and barrier protection, making them an ideal dressing for wounds [9,33]. Studies show that hydrogels loaded with EVs can significantly enhance diabetic wound healing, offering considerable potential for research and clinical applications [31,34]. To develop a hydrogel dressing with antimicrobial activity while loaded with EVs that can significantly promote tissue repair along with antimicrobial activity. Currently, there are various antimicrobial hydrogels, including the direct introduction of antibiotics, metal ions, or other plant components, but all of them have certain disadvantages, such as antibiotic abuse, bacterial resistance, metal toxicity, and complexity of preparation [35,36]. The development of a readily synthesized, simple material, antibiotic-free antimicrobial hydrogel dressing has important research implications and translational prospects.

For this purpose, we have synthesized an antibiotic-free antimicrobial hydrogel with good biological activity, mechanical properties, adhesion and antimicrobial properties by optimizing the parameters. The hydrogel composed of glycidyl methacrylate-modified epsilon-poly-lysine (EPLMA), epsilon-poly-lysine (EPL), and oxidized hyaluronic acid (OHA), creating a dynamic and biocompatible matrix. EPL and its derivatives have strong antimicrobial activity and are excellent candidates for the preparation of antimicrobial hydrogels [37,38]. Based on the Schiff base reaction and photo-crosslinking principle, this hydrogel can be synthesized under simple conditions to meet daily clinical needs.

This study aims to investigate the effects of BCL-2 overexpression on ADSC and their secreted EVs, and to design a novel hydrogel and evaluate the potential of the hydrogel loaded with BCL-2 engineered EVs to promote wound healing in diabetic mouse models (Fig. 1). We evaluated them using transcriptome sequencing and proteome sequencing technologies. We hypothesized that this advanced antibiotic-free antimicrobial hydrogel would provide a supportive microenvironment for the sustained release of EVs, thereby enhancing cell proliferation, stimulating angiogenesis, reducing inflammatory responses, and accelerating overall wound healing, thus providing a comprehensive understanding of the role of the hydrogel-EVs system in the wound repair process.

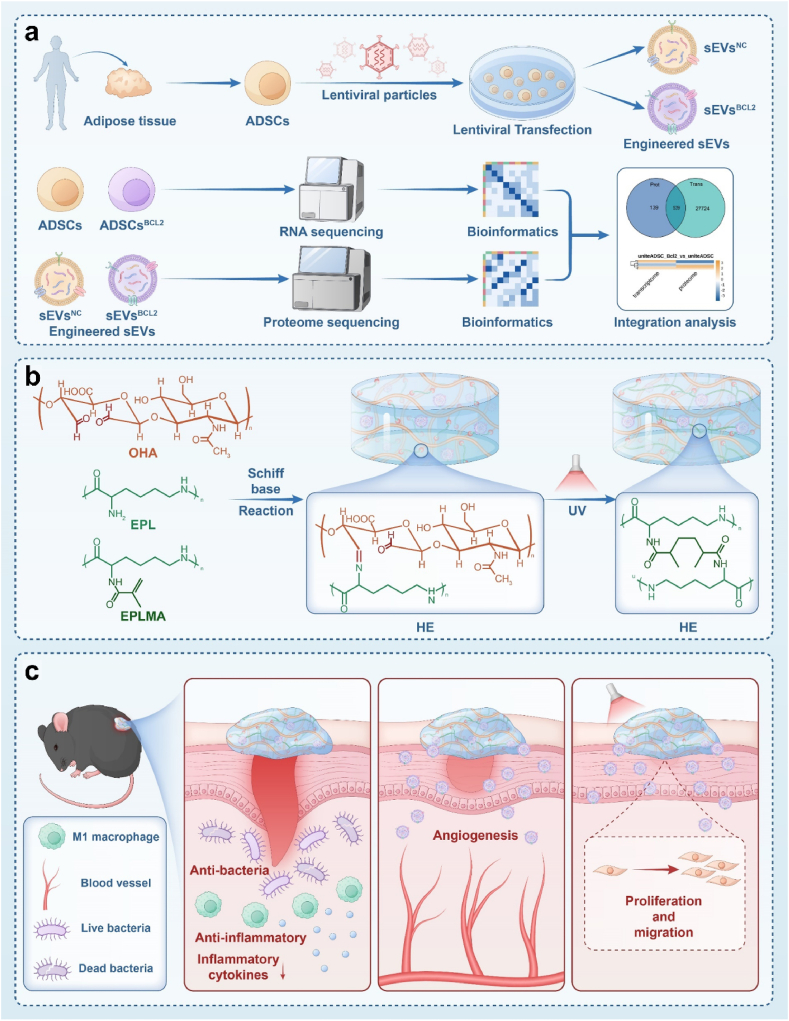

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of BCL-2 engineered extracellular vesicle-loaded antimicrobial hydrogel for comprehensive promotion of diabetic wound healing a.BCL-2 overexpressing ADSCs were constructed using lentiviral vectors, EVs were collected using differential ultracentrifugation, cells were analyzed by transcriptome sequencing technology, and EVs were analyzed by proteome sequencing. b. Hybrid hydrogel composed of glycidyl methacrylate-modified epsilon-poly-lysine (EPLMA), epsilon-poly-lysine (EPL), and oxidized hyaluronic acid (OHA), creating a dynamic and biocompatible matrix. c. The presence of EPL makes the hydrogel antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory, while providing barrier protection. The sustained release of BCL-2 engineered EVs has a powerful pro-angiogenic effect, promotes cell proliferation and migration, and comprehensively promotes the healing of diabetic wounds.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Enhanced angiogenic and regenerative potential of BCL-2-overexpressing ADSCs

Flow cytometry analysis confirmed the ADSCs phenotype, characterized by high expression levels of CD105, CD90, and CD73. Minimal expression of CD34, CD45 and HLA, validating their identity as ADSCs (Fig. S1). The differentiation potential of the ADSCs were assessed through adipogenic and osteogenic induction. Oil Red O staining revealed prominent lipid droplet formation, while Alizarin Red S staining indicated significant calcium salt deposition, confirming the ability of the cell to differentiate into adipogenic and osteogenic lineages. Additionally, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining results showed that osteogenic induction successfully promoted the differentiation of ADSCs into osteoblasts (Fig. S2). The above results confirm that the ADSCs used in the experiment are in good growth status and have the potential for multidirectional somewhat differentiation and can be used in subsequent experiments.

To examine the effect of BCL-2 on ADSCs, a lentiviral vector system was employed to induce BCL-2 overexpression in ADSCs at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. The optimal MOI was determined through preliminary experimentation and was consistent with previously reported findings in the literature (Fig. S3). Lentiviral viral vector mapping information shows in Fig. S4. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that successfully transfected cells exhibited strong green fluorescence (Fig. 2a). Additionally, flow cytometry verified successful transfection in cells treated with blank viral vectors and those treated with BCL-2 viral vectors (Fig. 2b). Overall, RNA and protein were extracted from the transfected cells for evaluation. Gene expression analysis using qRT-PCR and protein expression analysis using WB revealed significant overexpression of the BCL-2 gene and a marked increase in BCL-2 protein levels (Fig. 2c and d). These results showed the successful generation of ADSCs overexpressing BCL-2.

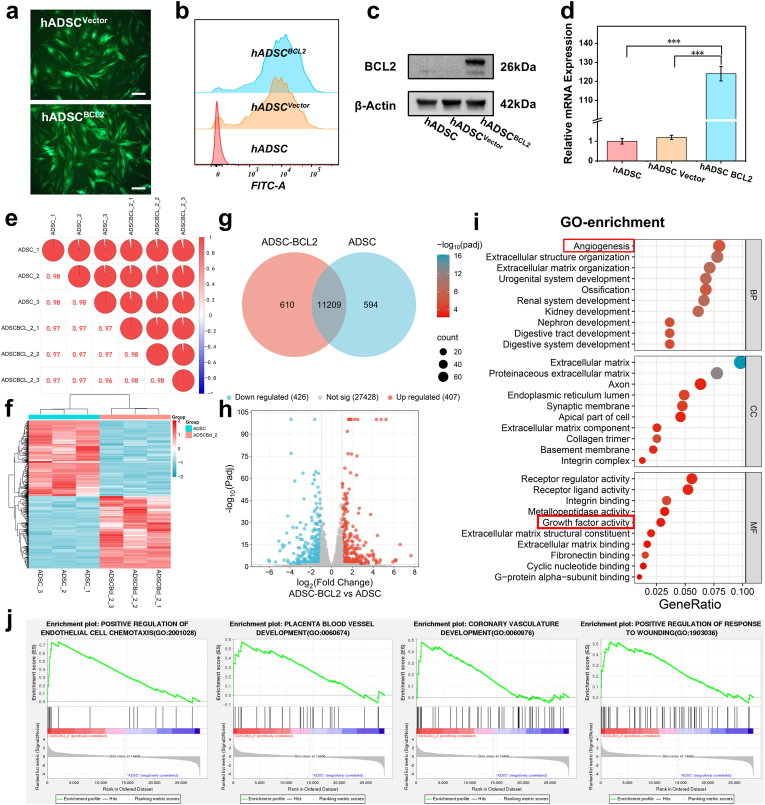

Fig. 2.

Construction and transcriptome sequencing analysis of BCL-2-overexpressing ADSCs a. Fluorescence pictures of hADSCs after transfection of blank vector and BCL-2 vector, the green fluorescence represents that the gene has been successfully transfected into the cell. The scale is 200 μm. b. The fluorescence intensity of the cells was quantified by flow cytometry to determine the transfection efficiency. c. BCL-2 protein expression level using WB. d. Relative transcript levels of the BCL-2 gene compared to the ACTB gene were detected using qRT-PCR. e. Consistency test for samples. f. Gene enrichment analysis heat map. g. Venn diagram showing co-expressed genes. h. The volcano diagram shows the differentially expressed genes. i. From the results of GO enrichment analysis, the most significant 30 Terms were selected to be plotted in a scatter plot for presentation. j. The correlation of our signaling pathways of interest with BCL-2 was analyzed using GSEA enrichment analysis. ∗∗∗:P < 0.001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

We performed transcriptome sequencing on ADSCs and BCL-2-overexpressing ADSCBCL−2 to identify differentially expressed genes. Initial analyses assessed the correlation between biological replicates, revealing a strong inter-sample correlation (R2 > 0.95) (Fig. 2e). Transcriptome analysis revealed 11,209 co-expressed genes between the control ADSCs and the BCL-2 over-expressing ADSCs group (Fig. 2g). We clustered the sets of differential genes from the two groups and analyzed them by clustering genes with similar expression patterns together to create a heat map of gene expression (Fig. 2f). Differentially expressed genes between the two groups were analyzed, and volcano plots were generated to visualize the significantly upregulated and downregulated genes (Fig. 2h). Importantly, 407 genes were significantly upregulated in the BCL-2-overexpressing cells. Furthermore, cluster analysis of differentially expressed genes was performed to group genes with similar expression patterns. GO enrichment analysis revealed significant upregulation in pathways associated with angiogenesis and growth factor activity (Fig. 2i). KEGG enrichment analysis showed that the differential genes were significantly enriched in the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetes and the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, which are closely related to diabetes and tissue repair (Fig. S5). The Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) results showed significant enrichment of several signaling pathways in the ADSCBCL−2 group, including positive regulation of endothelial cell, placental blood vessel development, chemotaxis coronary vasculature development, and positive regulation of wound healing, among others (Fig. 2j). Specifically, genes associated with blood vessel formation, growth factor secretion, and tissue repair were significantly upregulated, revealing that BCL-2 overexpression enhanced the angiogenesis and regenerative potential of ADSCs. We analyzed specific differential gene expression in detail and plotted it in a heat map, including the top 50 genes with the most pronounced differences, as well as genes related to angiogenesis and wound healing that we were more concerned about (Fig. S6). The results showed that in addition to BCL-2, some classic popular genes were enriched, such as EGR1, FGF2, WNT2, NRF2, and SERPINE1.

These findings suggested that BCL-2 overexpression significantly enhances the secretion of growth factors and promotes angiogenesis. This indicated that the role of BCL-2 extends beyond apoptosis regulation to increasing the ability of ADSCs to facilitate tissue regeneration and repair. This enhanced functionality could have significant implications for advancing therapies in tissue repair and regenerative medicine, particularly in conditions with impaired angiogenesis, such as highly diabetic wounds.

2.2. Enhanced biological activity of BCL-2-overexpressing EVs

We isolated EVs from BCL-2-overexpressing ADSCs using ultracentrifugation. The EVs were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) (Fig. 3a). TEM images confirmed the typical spherical morphology, while NTA revealed a size distribution consistent with the expected range for EVs. Western blot analysis confirmed the identity of EVs by detecting key surface markers (CD81 and CD63), while the absence of calnexin indicated minimal contamination (Fig. 3b).

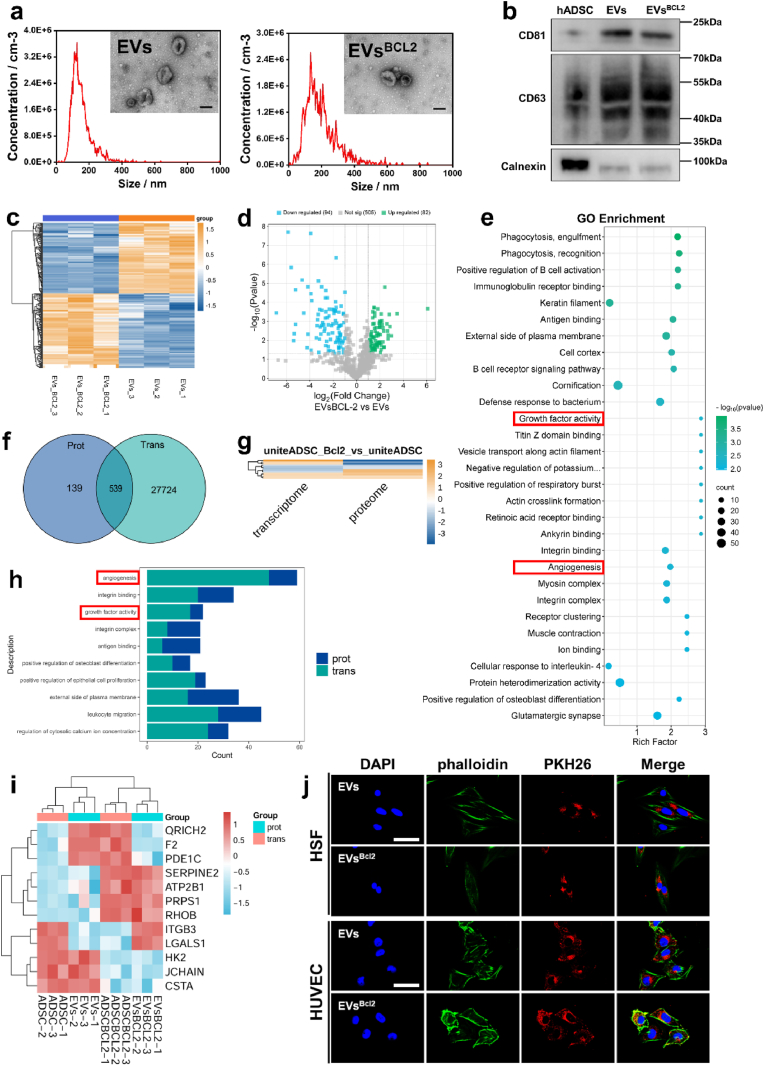

Fig. 3.

Isolation and characterization of EVs and proteomics sequencing a. Transmission electron micrographs of two groups of EVs and results of NTA particle size analysis. The scale is 100 nm. b. WB detection of positive markers CD63, CD81 and negative marker Calnexin in EVs. c. Cluster analysis heat map. d. Heatmap of differential protein expression between the two groups of samples. e. Scatterplot of GO functional enrichment analysis of differential proteins showing significantly different Top30 terms. f. Co-expression Venn diagram of the proteome and transcriptome. g. Clustered heatmap analysis was performed on the FC values (log2FC) of the shared differential genes obtained in the above Venn analysis in both histologies. h. We visualize the shared GO features in a bar chart. By default, in the shared the top 10 with the smallest sum of GO function. i. Cluster analysis of Up-Up, Down-Down, Up-Down, and Down-Up in the shared differential genes is presented as a heat map. j. Cellular uptake of EVs and EVsBCL−2. The scale is 50 μm.

To compare the functional differences between standard EVs and BCL-2-overexpressing EVs, we used 5D label-free proteomics for a detailed analysis. The proteomic data revealed significant differences in protein expression profiles between the two types of EVs (Fig. 3c and d). For the differential results screened by proteomics, we annotate them from three aspects, namely Biological Process, Cellular Component and Molecular Function, to elucidate the biological roles of the proteins from different perspectives. GO enrichment analysis revealed significant upregulation in growth factor activity and angiogenesis-related pathways in BCL-2-overexpressing EVs compared to that of the control EVs (Figs. S7 and 3e). This is consistent with our previous transcriptomic finding, which showed that BCL-2-overexpressing ADSCs exhibited enhanced expression of genes associated with these biological processes. These findings suggested that BCL-2-overexpressing EVs exhibit enhanced biological activity, particularly in promoting growth factor activity and angiogenesis. This enhancement highlights the potential of BCL-2-engineered EVs in regenerative medicine and suggests that they could offer greater therapeutic benefits for tissue repair and regeneration.

To further investigate the role of BCL-2 in cells and EVs, we integrated and analyzed the results of transcriptomic and proteomic data. To understand the overall landscape of genes common to the two histologies, a Venn analysis of all genes between the two histologies was performed, which revealed that 539 genes were shared between ADSCs and EVs (Fig. 3f and g). The shared GO-enriched functions of these genes became the focus of this analysis. We visualized the shared GO functions using bar graphs, which highlighted angiogenesis and growth factor activity as the most significantly enriched pathways in histologies (Fig. 3h–S8). To facilitate the researchers to observe the correlation between the GO functions of differential mRNAs and differential proteins, we also show the network diagrams of GO functions of the results of the “shared GO function” analysis. In particular, the network diagrams of Angiogenesis and Positive regulation of endothelial cell proliferation are shown (Fig. S9). Differential expressions were analyzed and compared, identifying 12 shared differentially expressed genes. A clustered heatmap analysis revealed that SERPINE2, ATP2B1, PRPS1, and RHOB were significantly upregulated in ADSCsBCL−2 and EVsBCL−2. We performed GO functional enrichment analysis of Up-Up genes to hypothesize the biological functions in which they may be involved. The results showed that in wound healing was significantly enriched (Fig. 3i). To confirm that cells can take up EVs as well as EVsBCL−2, we labeled them using the fluorescent label PKH26 and evaluated their uptake ability by HUVEC and HSF. The results showed that EVs and EVsBCL−2 were efficiently taken up by cells (Fig. 3j).

2.3. Synthesis and characterization of hybrid hydrogel

Given the promising results observed with BCL-2-overexpressing EVs, we sought to validate their efficacy in a diabetic wound model. Recognizing the limitations of EV stability in vitro and their rapid clearance upon application to wounds, alongside the challenges posed by the complex microenvironment of diabetic wounds, we developed a hybrid hydrogel to enhance EVs delivery and therapeutic effects. The hydrogel was designed to provide sustained release of EVs at the wound site while offering barrier protection properties.

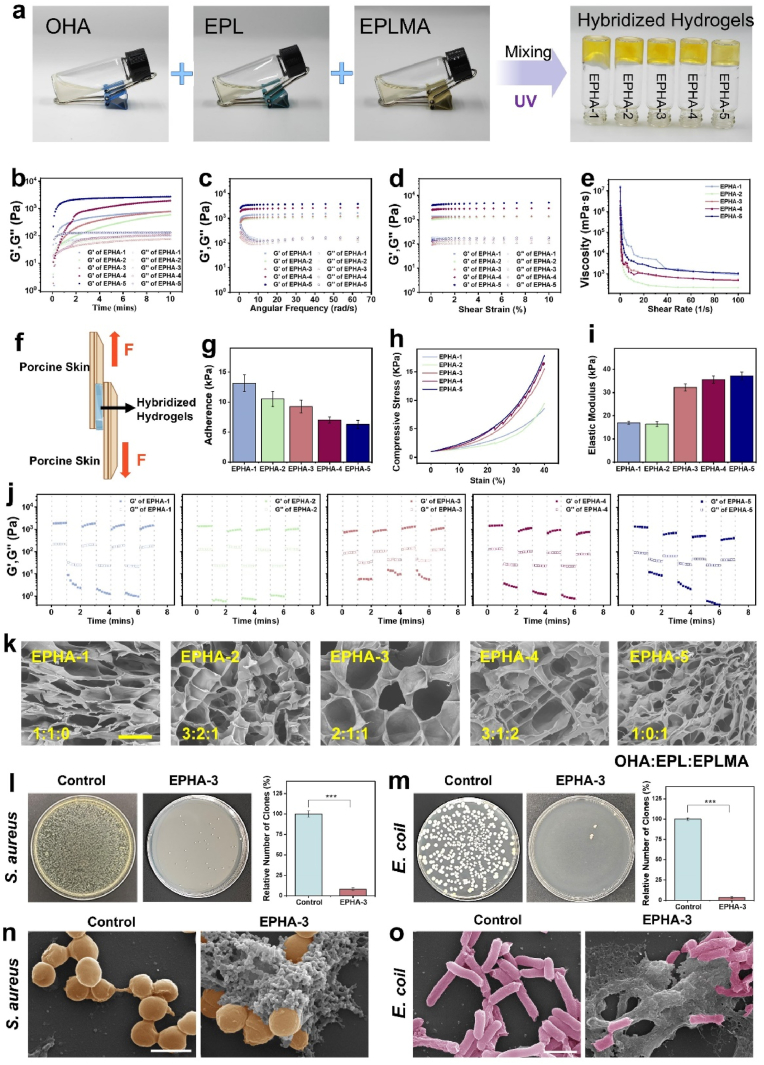

We aimed to construct a hydrogel using OHA, EPL, and EPLMA. OHA and EPLMA were synthesized and verified via Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to ensure successful conjugation (Fig. S10). To optimize the hydrogel formulation, five different component ratios were tested, and the resulting hydrogels were characterized using rheometry and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 4a–k). The hydrogel formulations by mixing different ratios of OHA, EPL, and EPLMA (EPHA-1 = 1:1:0, EPHA-2 = 3:2:1, EPHA-3 = 2:1:1, EPHA-4 = 3:1:2, EPHA-5 = 1:0:1) the formation of the hydrogel can be observed after UV light exposure. The morphology of the hydrogel became complete and stable as the proportion of EPLMA increased. The gelation time showed that hydrogels were formed within 30 s in nearly all groups (Fig. 4b). The rheomechanical properties of the hydrogels were assessed using a rheometer, and all formulations showed good stability in the frequency and amplitude scanning test (Fig. 4c and d). The shear-thinning behavior was observed across all groups, indicating that the hydrogel could be easily applied using a syringe, thereby expanding its potential applications (Fig. 4e). Since the goal is to develop biological dressings for skin wounds, hydrogel adhesion is crucial for ensuring effective wound coverage and barrier protection. To evaluate adhesion, tests were conducted using fresh porcine skin (Fig. 4f). The result showed that EPHA-1 formulation exhibited the highest adhesion, with adhesion levels decreasing as the EPLMA content increased (Fig. 4g). The mechanical properties of the hydrogels were evaluated using a universal testing machine, revealing that these properties improved with an increasing percentage of EPLMA (Fig. 4h and i). The alternating stress experiments indicated that all hydrogel formulations exhibited self-healing properties; however, this ability diminished as the number of alternating stress cycles increased (Fig. 4j).

Fig. 4.

Synthesis and characterization of EPHA hydrogels a. Macroscopic photograph of EPHA hydrogels formation. b. Dynamic rheological studies. c, d. Rheological behavior of hydrogels at different angular frequencies and under different shear strains. e. Shear thinning characterization. f, g. Characterization of the adhesion capacity of hydrogels. h, i. Characterization of mechanical properties of hydrogels. j. Rheological properties of hydrogels under alternating strains. k. Scanning electron micrograph of the hydrogels. The scale is 100 μm. l, m. The antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli was determined using the agar diffusion method. n, o. The electron microscopies of S. aureus (the scale is 1 μm) and E. coli (the scale is 2 μm). ∗∗∗:P < 0.001.

Given the antibacterial properties of EPL, antibacterial assays were conducted to assess its potential for preventing infection. The results showed that the hydrogel exhibited significant antibacterial activity, a beneficial feature for wound management. After EPHA treatment, the number of S. aureus and E. coli was significantly reduced, and all groups of hydrogels had strong antimicrobial capacity, with no significant difference between the groups before, and obvious morphological changes of bacteria were observed under the electron microscope (F igure S11, 4l-o). This hybrid hydrogel is expected to improve the stability and localized delivery of BCL-2-overexpressing EVs, thereby improving their therapeutic efficacy in diabetic wound healing.

2.4. BCL-2 engineered EVs loaded EPHA hydrogels can significantly promote angiogenesis and cell migration

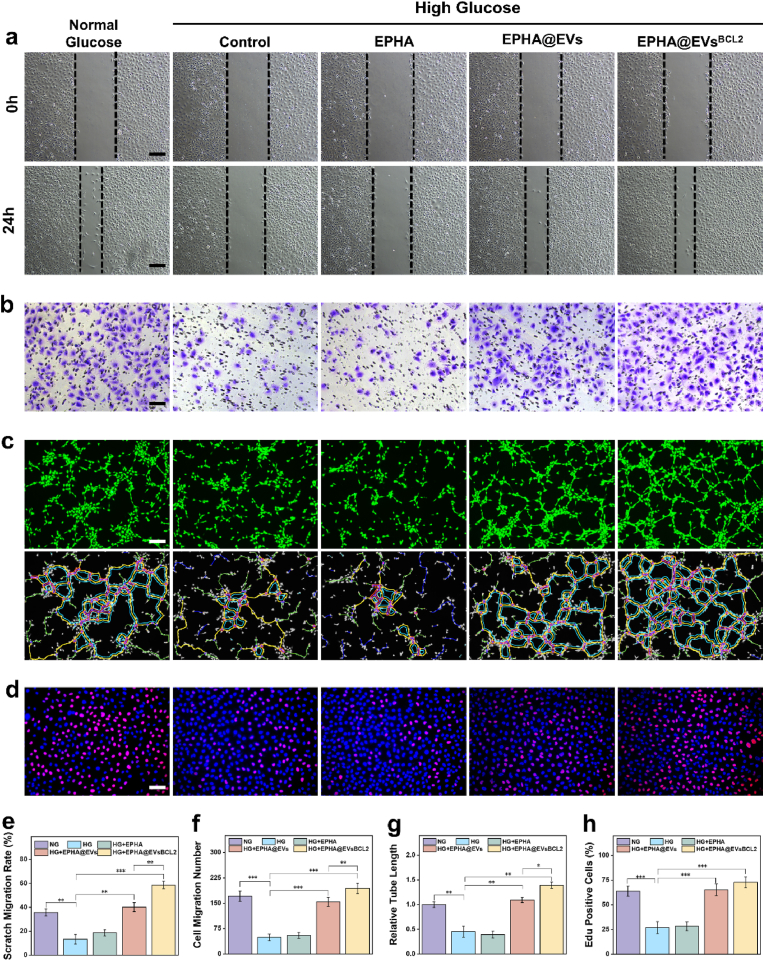

In order to evaluate the impact of this hydrogel system on cellular function, especially in high glucose environments, as we focus on its therapeutic potential in diabetic wounds. Initially, we cultured the cells using hydrogel leachates to evaluate its cytocompatibility, and the results showed that the EPHA hydrogel had good cytocompatibility, and no significant cytotoxicity was observed in both HUVEC and HSF cells (Fig. S12). We focused on evaluating the role of this hydrogel system in angiogenesis, as previous transcriptome sequencing results and proteomics sequencing results have suggested that EVsBCL−2 is expected to play an important role in angiogenesis. The experimental results showed that both groups containing EVs could significantly promote the migratory ability of HUVEC, including both horizontal and vertical migratory ability (a critical aspect of angiogenesis) in high glucose environments (Fig. 5a–f). And EVsBCL−2 could exert stronger biological activities compared with EVs. Further, we quantitatively evaluated the tubule formation ability of each group by the tube formation assay, which is a key assay for evaluating angiogenic ability in vitro. The results similarly showed that all groups containing EVs significantly promoted tubule formation, whereas the EVsBCL−2 group stimulates the formation of extensive and complex endothelial tube networks, underscoring its potential to promote angiogenesis. (Fig. 5c–g). In addition, based on the results of previous integrative showing that EVsBCL−2 may play an important role in the Positive regulation of endothelial cell proliferation, we evaluated the proliferative capacity of HUVEC by EdU Cell Proliferation Kit. The proliferative capacity of HUVEC was significantly impaired in a high glucose environment and was significantly restored after treatment with EVs, while EVsBCL−2 showed a stronger effect (Fig. 5d–h). Moreover, we likewise evaluated its effect on HSF cell function, and the results showed that both groups containing EVs promoted the scratch migration ability as well as the Transwells migration ability of HSF. Similarly, both the EVs group and the EVsBCL−2 group exhibited a promotion of cell proliferation capacity (Fig. S13). This suggests that EVsBCL−2 can play an important role not only in angiogenesis, but also its important biological activities in other cells, which in turn promote tissue repair and regeneration.

Fig. 5.

Hydrogel system has potent angiogenesis-promoting effects in vitro a, e. Cell scratch assay for HUVEC. The scale is 200 μm. b, f. Transwell migration assay for HUVEC. The scale is 100 μm. c, g. Tubule formation assay. The scale is 200 μm. d, h. EdU cell proliferation assay. The scale is 100 μm ∗:P < 0.05, ∗∗:P < 0.01, ∗∗∗:P < 0.001.

These results collectively highlight the potent angiogenic effects of the hydrogel systems, particularly under high-glucose conditions, which are often associated with impaired wound healing and vascular regeneration in patients with diabetes. The enhanced performance of BCL-2-overexpressing EVs in promoting angiogenesis could be attributed to the role of BCL-2 in enhancing the secretion of growth factors and supporting cell survival, thereby facilitating vascular repair and regeneration. This hydrogel represents a promising therapeutic strategy for improving vascular regeneration and wound healing under challenging diabetic conditions.

2.5. BCL-2 engineered EVs loaded EPHA hydrogels can comprehensive enhancement of diabetic wound healing

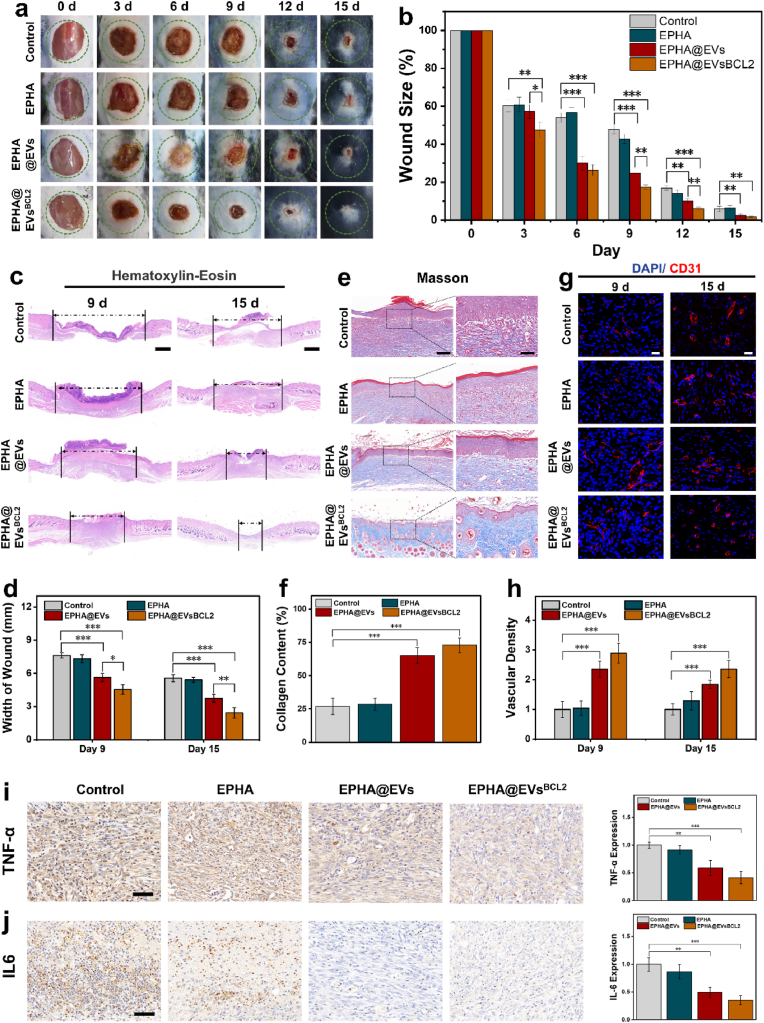

The therapeutic efficacy of EVsBCL−2-loaded EPHA hydrogels was evaluated in a diabetic mouse wound model. Streptozotocin-induced mice with diabetes received full-thickness excisional wounds on their dorsal skin. The wounds were treated with EVs-loaded EPHA hydrogels, EVsBCL−2-loaded EPHA hydrogels, empty EPHA hydrogels, and PBS as a control. Wound closure was systematically monitored and photographed at regular intervals, and the rate of wound healing was quantified using digital image analysis. It was observed that both groups containing EVs and EVsBCL−2 could significantly promote the healing of diabetic wounds in mice, and the promotion effect was more obvious in EVsBCL−2 (Fig. 6a and b). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed that the EVsBCL−2-loaded hydrogel had a smaller wound width and more intact tissue structure compared to the other groups (Fig. 6c and d). Masson staining results showed that both EVs-loaded and EVsBCL−2-loaded hydrogel groups showed more collagen deposition, whereas more restoration of skin appendages (e.g., hair follicles) could be observed in the EVsBCL−2 group (Fig. 6e and f). Immunofluorescence staining was used to detect the expression of CD31, a marker of neovascularization, to demonstrate peritraumatic angiogenesis. The results likewise showed that the EVsBCL2-loaded hydrogel could significantly promote angiogenesis in diabetic wounds (Fig. 6g and h).

Fig. 6.

BCL-2 engineered EVs loaded EPHA hydrogels can comprehensive enhancement of diabetic wound healing a. Photographs of healing wounds in each group of diabetic mice were taken on days 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15. b. Statistical analysis of wound healing. c. H&E staining of mouse wounds on day 9 and day 15. The scale is 1000 μm. d. Statistical results of wound width in mice. e. Masson staining of mouse wounds on day 15. The scale is 1000 μm. f. Collagen deposition result statistics. g. Immunofluorescence staining of CD31 in mouse wounds on day 9 and day 15. The scale is 20 μm. h. Statistics of trauma vessel density. i. Immunochemical staining of TNF-α, the scale is 50 μm. j. Immunochemical staining of IL-6, the scale is 50 μm∗:P < 0.05, ∗∗:P < 0.01, ∗∗∗:P < 0.001.

Additionally, inflammatory and apoptotic markers were analyzed to better understand the effects of the treatment. TNF-α and IL-6 levels, key indicators of inflammation, were significantly reduced in the wounds treated with EVsBCL−2-loaded hydrogels compared to that of the controls (Fig. 6i and j). This reduction in inflammatory markers suggests that EVsBCL−2 group exert anti-inflammatory effects, promoting a more favorable environment for wound healing. Further analysis of apoptosis-related indices using immunochemical staining with Cleaved Caspase-3 (C-Caspase-3) and BAX showed that apoptosis of periwound keratinocytes was significantly reduced in wounds treated with EVsBCL−2-loaded EPHA, which may also have been a factor in the accelerated healing of wounds (Fig. S14). However, apoptosis-related indicators were not significantly detected in other types of cells, probably due to their relatively low expression levels. Overall, the results showed that EVsBCL−2-loaded hydrogels significantly improved wound healing in diabetes mice by promoting angiogenesis, cell migration and cell proliferation while reducing inflammation and apoptosis. Finally, we collected organs from each group of mice after execution for H&E staining as a means of evaluating possible organ toxicity, and no abnormalities in organ histology were detected (Fig. S15). These findings showed the potential of EVsBCL−2-loaded hydrogels as an effective therapeutic approach for improving wound repair, especially under the challenging conditions of diabetes.

3. Conclusion

This study offers important insights into the role of BCL-2 in regenerative medicine by integrating cell transcriptomics and EVs proteomics. These findings revealed that BCL-2 significantly enhances the secretion of growth factors and angiogenic activity. Cell transcriptomics revealed a broad upregulation of genes associated with angiogenesis and growth factor activity in BCL-2-overexpressing ADSCs. Proteomic analysis of BCL-2-engineered EVs derived from these cells further validated this observation, highlighting a parallel enhancement in functional pathways associated with tissue repair and regeneration. The integration of cell transcriptomics and proteomics in this study provides a comprehensive perspective on the expanded biological functions of BCL-2. This dual-omics approach deepens our understanding of the role of BCL-2 in tissue regeneration and establishes a foundation for future advancements in regenerative medicine. By bridging the gap between molecular insights and therapeutic innovations, this study contributes to the development of targeted therapies for chronic wounds, paving the way for more effective clinical interventions.

The development and application of an antimicrobial hydrogel system (EPHA) for delivering BCL-2-engineered EVs represents a crucial innovation in this study. By enhancing the stability of EVs and enabling their controlled release, the hydrogel effectively addressed major challenges associated with EVs-based therapies for diabetic wound healing. Our in vitro and in vivo assays demonstrated the ability of the hydrogel to accelerate wound closure, reduce inflammation, and exterminate bacteria in diabetic wounds. These results showed the potential of EVsBCL−2-loaded hydrogels as a promising approach for managing complex wound healing scenarios and improving outcomes in chronic wound care.

However, despite these advances, this study has some limitations. This study was conducted in a diabetic mouse model, which, although informative, does not fully replicate the complexities of human wound-healing processes. It is important to note that BCL-2, as an anti-apoptotic protein, is also highly expressed in some tumors, and its potential biological risk requires attention. However, since our final treatment protocol used EVs isolated and obtained from stem cells with high BCL-2 expression, its potential tumorigenicity is minimal compared to direct treatment with stem cells. Additionally, while the hybrid hydrogel system showed promising results, further studies are necessary to assess its long-term stability, efficacy, and safety in clinical applications. Future research should aim to optimize the hydrogel formulation, investigate broader therapeutic uses of BCL-2-engineered EVs, and validate these findings in more diverse animal models and human clinical trials.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Materials

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer, Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffer Solution (DPBS), Penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.25 % trypsin were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; ADSCs, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), human skin fibroblasts (HSFs), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Procell Life Science & Technology Co. (Wuhan, China). Matrigel was purchased from Xiamen Mogengel (Xiamen, China); transwells cell culture chambers, cell culture related consumables were purchased from NEST Biotechnology; PKH26 Red Fluorescent Cell Membrane Staining Kit, Calcein-AM/PI Staining Kit, CCK8 Kit, EdU Cell Proliferation Assay Kit, phalloidin, and DAPI were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Technology Co.; Anti-BCL-2, Anti-CD63, Anti-Calnexin et al. antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc.; Anti-CD81 antibodies was purchased from Biodragon; FuturePAGE™ Protein Pregels and other Western blotting products were purchased from ACE Biotechnology; qPCR and One-Step RT MasterMixes were purchased from Applied Biological Materials Inc.; Lentiviral vector construction and sequencing technical services were assisted by Shanghai Genechem Co.; Hyaluronic acid, epsilon-poly-lysine were purchased from Shanghai yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd.; Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Slaughter Kingda Laboratory Animal Co. (Hunan, China).

4.2. Characterization of ADSCs

ADSCs were obtained from Procell Life Science & Technology, which is obtained from human fat based on enzymatic digestion. ADSCs were cultured using low glucose DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin, and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2. When the cells reached 80 % confluence, they were considered ready for passaging or cryopreservation. Second-passage ADSCs were selected to evaluate the expression of ADSCs biomarkers, including CD90, CD105, CD73, and negative markers including CD45, CD34, HLA, using flow cytometry. To assess the adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation potential of ADSC, 3rd–5th passage cells were seeded into six-well plates and treated with adipogenic or osteogenic differentiation induction media according to the instruction of the manufacturer. Calcium salt deposition and lipid droplet formation were analyzed using Alizarin Red S staining and Oil Red O staining, respectively.

4.3. BCL-2-engineered ADSC-derived EVs

ADSCs were genetically engineered to overexpress the BCL-2 gene using a lentiviral vector system, which was constructed by Shanghai GeneChem. Briefly, the lentiviral vector and transfection reagents were added to ADSCs at a cell density of 30–50 %. The optimal multiplicity of infection (MOI) for transfection was determined through preliminary experiments. Transfection efficiency was assessed based on the fluorescence intensity of transfected cells. To establish a stable cell line, non-transfected cells were eliminated using Puromycin selection.

EVs were isolated from the culture supernatant of BCL-2 overexpressing ADSCs using a multi-step centrifugation process. The culture medium was first processed through differential centrifugation to remove cells and debris. Subsequently, ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g for 1 h was performed on pellet EVs. The EV pellet was washed with PBS and subjected to a second round of ultracentrifugation to ensure purity. The isolated EVs were then characterized using nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) to measure their size and concentration. Western blotting analysis was performed to confirm the presence of established EV markers, including CD63 and CD81.

4.4. Transcriptome sequencing of cells

In this study, a standard RNA sequencing workflow was employed for cellular transcriptome analysis, comprising RNA extraction, library construction, sequencing, and data analysis. The integrity and purity of RNA samples were assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis, a NanoPhotometer and an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. PolyA-tailed mRNAs were enriched using the NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Building Kit, and cDNA libraries were constructed. Sequencing was performed with 150 bp paired-end reads on the Illumina platform. Data analysis included quality control, sequence alignment (using HISAT2), gene expression quantification (using FeatureCounts and FPKM), differential expression analysis (using DESeq2 or edgeR), functional enrichment analyses (Gene Ontology [GO] and KEGG), and gene set enrichment analysis to reveal significance.

4.5. Proteome sequencing of EVs

For the proteome analysis of EVs, a 5D label-free quantitative proteomics approach was used. This method, which does not require isotope labeling, enhances protein identification throughput and sensitivity by incorporating the ion mobility dimension (collision cross-section, [CCS]). The samples were separated using a NanoElute system and analyzed using PASEF mode on a timsTOF Pro mass spectrometer. The instrument was set at a flow rate of 300 nL/min with a parent ion scanning range of 100–1700 m/z. Data processing was conducted using the PaSER2023 software, which utilizes the CCS dimension to improve the accuracy of identification. Additionally, the software facilitates efficient protein quantification and performs significant difference analysis.

4.6. Preparation of hybrid hydrogels

The hybrid hydrogels were synthesized using EPLMA, EPL, and OHA. EPLMA was prepared according to previously established protocols [39], followed by purification through dialysis in distilled water and subsequent lyophilization. OHA was produced by oxidizing the polysaccharide backbone of hyaluronic acid with sodium periodate, generative reactive aldehyde groups. The modified hyaluronic acid was then purified and lyophilized.

To fabricate the hydrogels, EPLMA, EPL, and OHA were dissolved in PBS and mixed in a predetermined ratio to form a homogeneous solution. Gelation was induced by exposing the mixture to UV light (365 nm) for 3 min in the presence of a photoinitiator lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP), which initiated cross-linking of EPLMA. While the aldehyde groups on OHA formed Schiff bases with the amino groups of EPL, resulting in a dynamic covalent network.

The EVs were incorporated into the hybrid hydrogels by combining the EV suspension with a hydrogel precursor solution prior to UV cross-linking. The final concentration of EVs in the hydrogel was optimized to ensure sustained release and maximal therapeutic efficacy. Prepard EV-loaded hydrogels were stored at 4 °C until further use in in vitro and in vivo experiments.

4.7. Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR was conducted to validate the expression levels of key genes identified through RNA-Seq analysis. cDNA was synthesized from the extracted RNA using a reverse transcription kit, following the instructions of the manufacturer. qPCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix on a real-time PCR system with ACTB serving as the internal reference gene. Primer sequences for the target genes were designed based on RNA-seq results. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt method. The following primers were used for qRT-PCR: BCL-2: 5′-AGCCGTGTTACTTGTAGTGTG-3′ and 5′-TTCTGGTGTTTCCCCCTTGG-3′; ACTB: 5′-GTCATTCCAAATATGAGATGCGT-3′ and 5′-GCTATCACCTCCCCTGTGTG-3′.

4.8. Western blot

Western blotting was employed to confirm protein expression. Proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5 % non-fat milk to present non-specific binding and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies specific to the target proteins. After washing with buffer, the membranes were treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system.

4.9. Cell scratch assay

To evaluate cell migration and wound healing, a monolayer of HUVECs or HSF was scratched using a sterile pipette tip to create a wound gap. The cells were then treated with hydrogel leachates and incubated for 24 h. Migration into the wound area was monitored and quantified under a microscope to assess the rate of wound closure.

4.10. Transwells migration assay

HUVECs or HSF were seeded in the upper chamber of a Transwells insert, while hydrogel leachates were placed in the lower chamber. After 24 h of incubation period, cells that migrated through the membrane were fixed, stained, and quantified using a light microscope.

4.11. Tube formation assay

The angiogenic potential of HUVECs was tested using a tube formation assay on Matrigel-coated plates. HUVECs were seeded onto Matrigel and treated with hydrogel leachates. After 6–8 h of incubation, the formation was assessed using imaging. The number of tubes and the density of the tube networks were quantified to assess the angiogenic response to the treatment. Tubule formation was evaluated using Angiogenesis Analyzer plug-in imageJ software.

4.12. EdU assay

To assess cell proliferation, HUVECs or HSF were seeded in 24-well plates and exposed to hydrogel leachates. Following the treatment period, cells were incubated with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) for 8 h. The incorporated EdU was detected using a fluorescence microscope following staining with an EdU-specific fluorescent dye. The proportion of proliferating cells was quantified based on fluorescence intensity.

4.13. In vivo wound healing studies

The therapeutic efficacy of the BCL-2 EV-loaded hydrogel was assessed using a wound-healing model in mice with diabetes. Diabetes was induced in mice through streptozotocin administration following protocol established in previous studies [40]. The animal studies were conducted in accordance with humane animal handling practices under with the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. We randomly divided 48 C57BL/6J diabetic mice into 4 groups, corresponding to the control group, the blank hydrogel group, the hydrogel group loaded with EVs, and the hydrogel group loaded with EVsBCL−2. Following gas anesthetized with isoflurane, a full-thickness excisional wound was created on the dorsal skin of the mice. The wounds were treated with one of the following: hydrogel containing BCL-2-engineered EVsBCL−2, hydrogel containing unmodified EVs, an empty hydrogel, or PBS as controls. Wound closure was monitored and photographed at regular intervals, and healing rates were quantified using digital image analysis. On day 9 each group was randomized to execute 6 mice, preserving the wound tissue for subsequent staining analysis, and the remaining mice were executed at day 15.

After the treatment period, wound tissues were collected for comprehensive histological analyses. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was conducted to evaluate tissue re-epithelialization, while immunohistochemical staining for TNF-α and IL-6 (Inflammation indicators), BAX and Cleaved-caspase-3 (Apoptosis indicators), and immunofluorescence staining for CD31 (Neovascularization markers). Overall, we evaluated the healing of diabetic wounds in various ways.

4.14. Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA for multiple group comparisons. Statistical comparisons between 2 groups were analyzed using the student's t-test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yikun Ju: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Pu Yang: Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Xiangjun Liu: Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Rui Wu: Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Naisi Shen: Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology. Naihsin Hsiung: Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology. Anqi Yang: Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology. Chi Zhang: Visualization, Validation, Resources, Project administration. Bairong Fang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Liangle Liu: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China (No. 20241007).

Funding

This study was funded by the Hunan Provincial Health Commission Scientific Research Project, China (C202304106744) and the Hunan Natural Science Foundation of China, China (2024JJ5479).

Declaration of competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.101870.

Contributor Information

Bairong Fang, Email: fbrfbr2004@csu.edu.cn.

Liangle Liu, Email: liuliangle@wmu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Peña O.A., Martin P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of skin wound healing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024;25:599–616. doi: 10.1038/s41580-024-00715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uberoi A., McCready-Vangi A., Grice E.A. The wound microbiota: microbial mechanisms of impaired wound healing and infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024;22:507–521. doi: 10.1038/s41579-024-01035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Z., Bian X., Luo L., BjörklundÅ K., Li L., Zhang L., Chen Y., Guo L., Gao J., Cao C., Wang J., He W., Xiao Y., Zhu L., Annusver K., Gopee N.H., Basurto-Lozada D., Horsfall D., Bennett C.L., Kasper M., Haniffa M., Sommar P., Li D., Landén N.X. Spatiotemporal single-cell roadmap of human skin wound healing. Cell Stem Cell. 2024;32:479–498.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2024.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong Y., Mi B.-B., Lin Z., Hu Y.-Q., Yu L., Zha K.-K., Panayi A.C., Yu T., Chen L., Liu Z.-P., Patel A., Feng Q., Zhou S.-H., Liu G.-H. The role of the immune microenvironment in bone, cartilage, and soft tissue regeneration: from mechanism to therapeutic opportunity. Mil. Med. Res. 2022;9:65. doi: 10.1186/s40779-022-00426-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiong Y., Mi B.-B., Shahbazi M.-A., Xia T., Xiao J. Microenvironment-responsive nanomedicines: a promising direction for tissue regeneration. Mil. Med. Res. 2024;11:69. doi: 10.1186/s40779-024-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qian Y., Ding J., Zhao R., Song Y., Yoo J., Moon H., Koo S., Kim J.S., Shen J. Intrinsic immunomodulatory hydrogels for chronic inflammation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025;54:33–61. doi: 10.1039/d4cs00450g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y., Zhu Z., Li S., Xie X., Qin L., Zhang Q., Yang Y., Wang T., Zhang Y. Exosomes: compositions, biogenesis, and mechanisms in diabetic wound healing. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:398. doi: 10.1186/s12951-024-02684-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan M.H., Zhang X.Z., Jiang Y.L., Pi J.K., Zhang J.Y., Zhang Y.Q., Xing F., Xie H.Q. Exosomes from hypoxic urine-derived stem cells facilitate healing of diabetic wound by targeting SERPINE1 through miR-486-5p. Biomaterials. 2025;314 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.122893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K., He Q., Yang M., Qiao Q., Chen J., Song J., Zang N., Hu H., Xia L., Xiang Y., Yan F., Hou X., Chen L. Glycoengineered extracellular vesicles released from antibacterial hydrogel facilitate diabetic wound healing by promoting angiogenesis. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2024;13 doi: 10.1002/jev2.70013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang X., Gupta D., Xie J., Van Wonterghem E., Van Hoecke L., Hean J., Niu Z., Ghaeidamini M., Wiklander O.P.B., Zheng W., Wiklander R.J., He R., Mamand D.R., Bost J., Zhou G., Zhou H., Roudi S., Estupiñán H.Y., Rädler J., Zickler A.M., Görgens A., Hou V.W.Q., Slovak R., Hagey D.W., de Jong O.G., Uy A.G., Zong Y., Mäger I., Perez C.M., Roberts T.C., Carter D., Vader P., Esbjörner E.K., de Fougerolles A., Wood M.J.A., Vandenbroucke R.E., Nordin J.Z., El Andaloussi S. Engineering of extracellular vesicles for efficient intracellular delivery of multimodal therapeutics including genome editors. Nat. Commun. 2025;16:4028. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-59377-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng X., Gan J., Huang D., Zhao Y., Sun L. Recombinant human collagen hydrogels with different stem cell-derived exosomes encapsulation for wound treatment. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025;23:241. doi: 10.1186/s12951-025-03319-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang S., Sun Y., Yan C. Recent advances in the use of extracellular vesicles from adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medical therapeutics. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:316. doi: 10.1186/s12951-024-02603-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song Y., You Y., Xu X., Lu J., Huang X., Zhang J., Zhu L., Hu J., Wu X., Xu X., Tan W., Du Y. Adipose‐derived mesenchymal stem cell‐derived exosomes biopotentiated extracellular matrix hydrogels accelerate diabetic wound healing and skin regeneration. Adv. Sci. 2023;10 doi: 10.1002/advs.202304023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong Y., Lin Z., Bu P., Yu T., Endo Y., Zhou W., Sun Y., Cao F., Dai G., Hu Y., Lu L., Chen L., Cheng P., Zha K., Shahbazi M.A., Feng Q., Mi B., Liu G. A whole‐course‐repair system based on neurogenesis‐angiogenesis crosstalk and macrophage reprogramming promotes diabetic wound healing. Adv. Mater. 2023;35 doi: 10.1002/adma.202212300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nie M., Huang D., Chen G., Zhao Y., Sun L. Bioadhesive microcarriers encapsulated with IL‐27 high expressive MSC extracellular vesicles for inflammatory bowel disease treatment. Adv. Sci. 2023;10 doi: 10.1002/advs.202303349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M., Yang D., Li L., Wu P., Sun Y., Zhang X., Ji C., Xu W., Qian H., Shi H. A dual role of mesenchymal stem cell derived small extracellular vesicles on TRPC6 protein and mitochondria to promote diabetic wound healing. ACS Nano. 2024;18:4871–4885. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c09814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei Q., Su J., Meng S., Wang Y., Ma K., Li B., Chu Z., Huang Q., Hu W., Wang Z., Tian L., Liu X., Li T., Fu X., Zhang C. MiR‐17‐5p‐engineered sEVs encapsulated in GelMA hydrogel facilitated diabetic wound healing by targeting PTEN and p21. Adv. Sci. 2024;11 doi: 10.1002/advs.202307761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao Y., Zhang Z., Ouyang L., Mi B., Liu G. Engineered extracellular vesicles in wound healing: design, paradigms, and clinical application. Small. 2023;20 doi: 10.1002/smll.202307058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo L., Xiao D., Xing H., Yang G., Yang X. Engineered exosomes as a prospective therapy for diabetic foot ulcers. Burns Trauma. 2024;12 doi: 10.1093/burnst/tkae023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nie M., Huang D., Chen G., Zhao Y., Sun L. Bioadhesive microcarriers encapsulated with IL-27 high expressive MSC extracellular vesicles for inflammatory bowel disease treatment. Adv. Sci. 2023;10 doi: 10.1002/advs.202303349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min X., Deng X.H., Lao H., Wu Z.C., Chen Y., Luo Y., Wu H., Wang J., Fu Q.L., Xiong H. BDNF-enriched small extracellular vesicles protect against noise-induced hearing loss in mice. J. Contr. Release. 2023;364:546–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashkenazi A., Fairbrother W.J., Leverson J.D., Souers A.J. From basic apoptosis discoveries to advanced selective BCL-2 family inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;16:273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogler M., Braun Y., Smith V.M., Westhoff M.A., Pereira R.S., Pieper N.M., Anders M., Callens M., Vervliet T., Abbas M., Macip S., Schmid R., Bultynck G., Dyer M.J. The BCL2 family: from apoptosis mechanisms to new advances in targeted therapy. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2025;10:91. doi: 10.1038/s41392-025-02176-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ardehali R., Inlay M.A., Ali S.R., Tang C., Drukker M., Weissman I.L. Overexpression of BCL2 enhances survival of human embryonic stem cells during stress and obviates the requirement for serum factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:3282–3287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019047108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Czabotar P.E., Garcia-Saez A.J. Mechanisms of BCL-2 family proteins in mitochondrial apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023;24:732–748. doi: 10.1038/s41580-023-00629-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Croce C.M., Vaux D., Strasser A., Opferman J.T., Czabotar P.E., Fesik S.W. The BCL-2 protein family: from discovery to drug development. Cell Death Differ. 2025 doi: 10.1038/s41418-025-01481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y., Li G., Li G., Pan Y., Liu Z. BCL-2 overexpression exosomes promote the proliferation and migration of mesenchymal stem cells in hypoxic environment for skin injury in rats. J. Biol. Eng. 2025;19:7. doi: 10.1186/s13036-024-00471-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui Z., Zhou H., He C., Wang W., Yang Y., Tan Q. Upregulation of Bcl-2 enhances secretion of growth factors by adipose-derived stem cells deprived of oxygen and glucose. Biosci. Trends. 2015;9:122–128. doi: 10.5582/bst.2014.01133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dissanayaka W.L., Han Y., Zhang L., Zou T., Zhang C. Bcl-2 overexpression and hypoxia synergistically enhance angiogenic properties of dental pulp stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:6159. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni X., Ou C., Guo J., Liu B., Zhang J., Wu Z., Li H., Chen M. Lentiviral vector-mediated co-overexpression of VEGF and Bcl-2 improves mesenchymal stem cell survival and enhances paracrine effects in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017;40:418–426. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ju Y., Hu Y., Yang P., Xie X., Fang B. Extracellular vesicle-loaded hydrogels for tissue repair and regeneration. Mater. Today Bio. 2023;18 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Y., Mao J., Zhou Y., Hong G., Wu H., Hu Z., Huang X., Shi J., Xie Z., Lan Y. Youthful brain-derived extracellular vesicle-loaded GelMA hydrogel promotes scarless wound healing in aged skin by modulating senescence and mitochondrial function. Research. 2025;8:644. doi: 10.34133/research.0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie Q., Yan C., Liu G., Bian L., Zhang K. In situ triggered self-contraction bioactive microgel assembly accelerates diabetic skin wound healing by activating mechanotransduction and biochemical pathway. Adv. Mater. 2024;36 doi: 10.1002/adma.202406434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C., Wang M., Xu T., Zhang X., Lin C., Gao W., Xu H., Lei B., Mao C. Engineering bioactive self-healing antibacterial exosomes hydrogel for promoting chronic diabetic wound healing and complete skin regeneration. Theranostics. 2019;9:65–76. doi: 10.7150/thno.29766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang Y., Liang Y., Zhang H., Guo B. Antibacterial biomaterials for skin wound dressing. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2022;17:353–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L., Luo Z., Chen H., Wu X., Zhao Y. Glycyrrhizic acid hydrogel microparticles encapsulated with mesenchymal stem cell exosomes for wound healing. Research. 2024;7:496. doi: 10.34133/research.0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X., Wang C., Liu Y., Niu H., Zhao W., Wang J., Dai K. Inherent antibacterial and instant swelling ε-poly-lysine/poly(ethylene glycol) diglycidyl ether superabsorbent for rapid hemostasis and bacterially infected wound healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:36709–36721. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c02421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Q., Cui S., Song X., Hu J., Zhou Y., Liu Y. An antimicrobial peptide-immobilized nanofiber mat with superior performances than the commercial silver-containing dressing, Materials science & engineering. C. Mat. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. 2021;119 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.111608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou C., Li P., Qi X., Sharif A.R.M., Poon Y.F., Cao Y., Chang M.W., Leong S.S.J., Chan-Park M.B. A photopolymerized antimicrobial hydrogel coating derived from epsilon-poly-l-lysine. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2704–2712. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang Q., Chu Z., Wang Z., Li Q., Meng S., Lu Y., Ma K., Cui S., Hu W., Zhang W., Wei Q., Qu Y., Li H., Fu X., Zhang C. circCDK13-loaded small extracellular vesicles accelerate healing in preclinical diabetic wound models. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:3904. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-48284-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.