Abstract

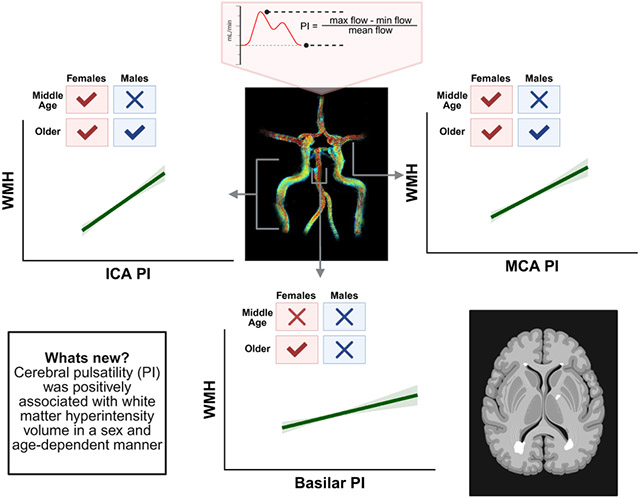

Arterial stiffening with age, which is associated with elevated cerebral pulsatility in the intracranial arteries, is linked to structural alterations in the brain, including white matter hyperintensities (WMH). Biological sex differences exist in cerebral hemodynamics and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk; yet little is known regarding the impact of biological sex on the association between cerebral pulsatility and WMH. We studied 403 cognitively unimpaired middle-aged and older adults (45-91 years, 272 females) who completed 3T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). 4D flow MRI provided measures of cerebral pulsatility index (PI) in multiple intracranial arteries. T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images were analyzed for WMH volumes. In middle-aged adults, PI in the internal carotid arteries (ICA) and the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) was positively associated with WMH in females (all P < 0.01) but not in males (all P > 0.25). In older adults, PI in the left ICA and the MCAs was positively associated with WMH in males and females (all P ≤ 0.02). Also, in older adults, basilar artery PI was positively associated with WMH in females (P = 0.006) but not males (P = 0.31). These data suggest that, among cognitively unimpaired adults, elevated cerebral PI is linked to greater WMH; however, these relationships are influenced by sex and age such that female-specific relationships emerge in the anterior circulation in middle age, and in the posterior circulation in older adults. These findings may provide insights to vascular mechanisms contributing to sex differences in AD with advancing age.

Keywords: 4D flow MRI, aging, biological sex, cerebral pulsatility, white matter hyperintensities

Graphical Abstract

New & Noteworthy

The vascular mechanisms underlying the elevated prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease among females remain unclear. In this study, we found that positive relationships between cerebral pulsatility in the anterior circulation and white matter hyperintensities (WMH) emerged in females in middle-age but not until older adulthood in males. Additionally, female-specific relationships were present between cerebral pulsatility in the posterior circulation and WMH in older adults.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias represent leading causes of disability and mortality worldwide (1). Importantly, vascular factors contribute to the development and progression of neurodegenerative disease whereby dysregulation of cerebral blood flow precedes Aβ deposition, brain atrophy, and white matter lesions in preclinical models and humans (2-5). Brain changes leading to cognitive decline emerge years before clinical diagnosis. Indeed, recent studies provide evidence that changes in neuroimaging and fluid-based biomarkers can begin decades before diagnosis (6). However, the precise vascular alterations that occur in the latent phase of AD and contribute to the development and progression of AD neuropathology remain unknown.

White matter (WM) lesions, observed as WM hyperintensities (WMH) on T2-weighted MRI images, predominantly represent cerebral small vessel disease and are linked to cognitive impairments (7). As such, WMH are considered one marker of vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia. Vascular mechanisms that may contribute to WMH include arterial stiffening of the large central arteries (8, 9) and cerebral arteries (10, 11) with age. Stiffening of the large central arteries contributes to the transmission of elevated blood flow pulsatility to the brain, as we have previously shown that aortic stiffness is positively linked with cerebral pulsatility in the large cerebral arteries as measured with state-of-the-art 4D flow MRI (12). Importantly, transmission of elevated cerebral pulsatility to the cerebral microvasculature may disrupt the blood brain barrier and damage myelin structure and axons in the WM (5) which are key alterations associated with WMH (13). Indeed, elevated cerebral pulsatility is linked with greater WM disease in patients with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack (14, 15). In healthy adults, similar associations are observed between cerebral pulsatility and WM injury (16, 17). However, these studies in healthy adults relied on transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD) measures of blood velocity for the calculation of cerebral pulsatility as opposed to measures of blood flow. Previously, we have shown weak agreement between cerebral pulsatility measures calculated from blood velocity with TCD and blood flow with 4D flow MRI (18). Additionally, use of blood velocity measures from TCD are less sensitive to age-related differences in cerebral pulsatility that are captured with blood flow measures from 4D flow MRI (18). While previous investigations have demonstrated associations between MRI-based measures of arterial stiffness or cerebral pulsatility and WM lesions (19-21), these studies used a single vessel or computed a global measure of arterial stiffness or cerebral pulsatility overlooking possible regional influences which have been reported with TCD (16). To the best of our knowledge, no studies have evaluated associations between 4D flow MRI measures of regional cerebral pulsatility and WMH in middle-aged and older adults without cognitive impairment.

Sex differences are apparent in cerebral hemodynamics across the adult lifespan. We have previously reported that females demonstrate steeper rates of elevation in cerebral pulsatility with aging (22). Despite these sex differences in cerebral hemodynamics, and also in AD prevalence with age (23, 24), to the best of our knowledge, no research to date has examined the impact on biological sex on the link between cerebral pulsatility and WMH in healthy, cognitively unimpaired adults. Further, middle-age represents a critical time contributing to known sex differences in cerebral hemodynamics as women experience vascular dysfunction associated with the menopause transition (25). Therefore, exploring sex differences in associations between cerebral pulsatility and WMH in both middle-age and older adults may provide valuable insights into vascular mechanisms associated with declining brain health in aging adults.

Therefore, this study aimed to determine the impact of cerebral pulsatility on WMH in cognitively unimpaired middle-aged and older adults and to evaluate the influence of biological sex on this relationship. We tested the hypothesis that elevated cerebral pulsatility is associated with higher WMH and that the associations between cerebral pulsatility and WMH in aging adults are sex specific. To address this hypothesis, we utilized 4D flow MRI measures of cerebral pulsatility in multiple intracranial arteries and T2-weighted measures of WMH in a large sample of cognitively unimpaired middle-aged and older males and females.

Methods

Participants

Participants included in the study analysis were from the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). Participants are enrolled in the ADRC if they i) have a diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease, ii) have a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, or iii) are adults 45 years of age and older with or without a parental history of Alzheimer’s disease. Cognitive status was determined from clinician and neuropsychologist consensus of neuropsychological examinations, laboratory, and imaging criteria (26, 27). In this study, 403 cognitively unimpaired adults (131 males, 272 females) between 45 and 91 years of age were included. Exclusion criteria consisted of a confirmed diagnosis of MCI or dementia, uncontrolled hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, kidney disease requiring hemodialysis, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, stent, stroke, alcohol abuse, current smoker, and major neurological disorders. All study procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board and performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki by obtaining written informed consent from each participant.

Laboratory Measures

Participants’ height and weight were collected, and measures of waist and hip circumference were obtained. Resting blood pressure and heart rate (HR) measures were obtained in the seated position and a venipuncture was performed for glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Parental family history of dementia and education years was obtained from all participants. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) status was determined using DNA that was extracted from blood samples (28). Participants were defined as APOE ε4 positive if they carried one or more copies of the ε4 allele and APOE ε4 negative if they did not carry copies of the ε4 allele.

MRI Measurements

Cranial MRI scans were performed on a 3T clinical MRI scanner (Discovery MR750 or Signa Premier, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, United States) at the Wisconsin Institutes for Medical Research. In the supine position, participants were fitted and imaged with an 8-channel (GE HealthCare, Madison, WI, USA; n = 20), 32-channel (Nova Medical Head Coil, Nova Medical, Wilmington, MA, USA; n = 358), or a 48-channel head coil (GE HealthCare, Madison, WI, USA; n = 20). Intracranial volume (ICV) was measured using a T1-weighted structural scan with the following parameters: fast spoiled gradient echo sequence, inversion time = 450 ms, repetition time (TR) = 8.1 ms, echo time (TE) = 3.2 ms, flip angle = 12°, acquisition matrix = 256 × 256, field of view (FOV) = 256 mm, slice thickness = 1.0 mm, and scan time ~6 min. Total WMH lesion volume was measured using a T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) scan with the following parameters: inversion time = 1,724–1,742 ms, TR = 6,000–6,002 ms, TE = 107–125 ms, flip angle = 90, acquisition matrix = 256 × 256, FOV = 256 mm, slice thickness = 1.6–2.0 mm, and scan time ~4 min. Cerebral artery hemodynamics were assessed using 4D flow MRI using a 3D radially undersampled sequence that included volumetric, time-resolved phase contrast MRI data with three-directional velocity encoding (PC-VIPR) (29, 30). The imaging parameters were as follows: velocity encoding (Venc) = 80 cm/s, FOV = 220 mm x 220 mm x 160 mm, acquired isotropic spatial resolution = 0.7 mm × 0.7 mm × 0.7 mm, TR = 7.4-8.6 ms, TE = 2.5-2.7 ms, flip angle = 8-10°, receiver bandwidth = 83.3 kHz, number of projection angles = 11,000-14,000 and scan time ~6-7 min. Time-resolved velocity and magnitude data were reconstructed offline by retrospectively gating into 20 cardiac phases using temporal interpolation (31).

Data Analysis

To determine gray matter (GM) volume, white matter (WM) volume, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume, tissue class segmentation of T1-weighted images was performed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) 12. Subsequently, ICV was determined as the sum of GM volume, WM volume, and CSF volume. WMH were assessed offline, as previously described (32), using a lesion prediction algorithm from the Lesion Segmentation Tool (LST) in SPM. WMH was calculated as WMH volume relative to ICV and cubic root transformed to reduce skewness (32). The 4D flow MRI scans were also evaluated offline by one of two study team members (BGF & AMN). The scans underwent background phase offset correction, eddy current correction and automatic phase unwrapping to minimize potential for velocity aliasing (33). Vessel segmentation of the left and right internal carotid arteries (ICA), left and right middle cerebral arteries (MCA), left and right vertebral arteries (VA), and basilar artery was performed in MATLAB using an in-house tool as previously described for semi-automated cerebrovascular hemodynamic analysis (34). Regions of interest (ROIs) were determined, and vessel cross-sectional area and blood flow are quantified from the ROIs and blood velocity signal. For the ICA, two regions were selected (the cervical and cavernous regions). At each sampling location, an average of five consecutive centerline point measures were utilized and cerebral pulsatility index (PI) was calculated as (maximum flow - minimum flow) / mean flow. The cervical and cavernous regions of the ICA were averaged for ICA PI. Damping factor (DF) was calculated as proximal PI / distal PI. The cervical region of the ICA and the vertebral arteries were defined as the proximal arteries and the MCA and basilar artery were defined as the distal arteries, respectively (ICA-MCA DF and VA-Basilar DF).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 28.0.1.0 (IBM, SPSS Inc., Armonk, New York, USA). Independent samples t-tests evaluated participant demographics, intracranial cerebral artery measures, and WMH between females and males. A chi-square test for association evaluated APOE ε4 status and proportions of diabetes and hypertension between males and females. Univariate linear regression assessed the relationship between cerebral PI in multiple intracranial arteries (Left ICA, Right ICA, Left MCA, Right MCA, Left VA, Right VA, Basilar) and WMH in the combined group and a priori sex stratified models evaluated biological sex differences (females and males). Based on a priori hypotheses, interactions between sex and age on the associations between cerebral PI and WMH were evaluated with separate univariate linear regressions in middle-aged females, middle-aged males, older females, and older males. Middle-aged females and males were defined as < 64 years of age and older females and males were defined as ≥ 64 years of age. To control for the independent influence of blood pressure and HR on WMH volume (35, 36), mean arterial pressure (MAP) and HR were included as covariates. To control for the association between APOE ε4 and cerebrovascular dysfunction (37, 38) as well as WMH (39, 40), APOE ε4 status was included as a covariate. Given links between cardiovascular risk factors, such as diabetes and hypertension, lipids, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and WM damage (41-43), these variables were included as covariates. A multivariate regression model assessed the association between cerebral PI and WMH when adjusting for covariates in the combined group and when stratified by sex. Given violations of the recommended events per variable (44) when stratifying by sex and age group, separate univariate regressions assessed relationships between cerebral PI and WMH when adjusting for covariates. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics are reported for the combined group and by sex in Table 1. Of the 403 participants included in the study, 263 had a parental history of Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias. APOE status was available in 380 participants, and 146 of these participants were APOE ε4 positive (~38%). APOE status did not differ between males and females (P = 0.60). The proportion of participants with diabetes and hypertension did not differ between males and females (both P ≥ 0.92). Approximately 16% of participants in the study were from racial groups traditionally underrepresented in research including Black or African American and American Native or Alaska Native. The distribution of race in this study is comparable to the overall cohort in the Wisconsin ADRC in which 24% of participants are from underrepresented groups. The average age difference between the laboratory and MRI visits was 2.4 ± 4.4 months.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics for the Combined Group and by Sex.

| Combined n = 403 |

Females n = 272 |

Males n = 131 |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64 ± 8 | 64 ± 8 | 63 ± 8 | 0.95 |

| Education, years | 16 ± 2 | 16 ± 2 | 17 ± 2 | 0.003 |

| Height, cm | 167 ± 10 | 163 ± 6 | 178 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 81 ± 18 | 76 ± 17 | 91 ± 15 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.8 ± 6.2 | 28.8 ± 6.8 | 28.8 ± 4.6 | 0.93 |

| Waist Circumference, cm | 98 ± 15 | 97 ± 16 | 102 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| Hip Circumference, cm | 107 ± 12 | 108 ± 14 | 104 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 123 ± 15 | 122 ± 16 | 126 ± 13 | 0.02 |

| DBP, mmHg | 77 ± 8 | 76 ± 8 | 78 ± 8 | 0.06 |

| MAP, mmHg | 92 ± 10 | 91 ± 10 | 94 ± 9 | 0.01 |

| PP, mmHg | 46 ± 11 | 46 ± 11 | 47 ± 9 | 0.11 |

| HR, mmHg | 65 ± 11 | 67 ± 11 | 62 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 101 ± 23 | 101 ± 24 | 102 ± 21 | 0.35 |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 199 ± 42 | 206 ± 40 | 183 ± 40 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 101 ± 52 | 101 ± 51 | 102 ± 56 | 0.15 |

| HDL Cholesterol, mg/dL | 60 ± 16 | 64 ± 16 | 52 ± 14 | <0.001 |

| LDL Cholesterol, mg/dL | 118 ± 34 | 121 ± 34 | 111 ± 32 | 0.002 |

| hs-CRP, mg/dL | 2.5 ± 4.2 | 2.9 ± 4.8 | 1.8 ± 2.2 | 0.03 |

| Vascular Risk, % | 11 ± 7 | 8 ± 5 | 16 ± 7 | <0.001 |

Values are mean ± SD. BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PP, pulse pressure; HR, heart rate; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Vascular risk based on Framingham 10-year cardiovascular disease risk. P value represents results of independent samples t-tests evaluating differences between females and males.

Intracranial hemodynamics and WMH are reported for the combined group and by sex in Table 2. Males demonstrated larger left and right ICA diameters, right MCA diameters, and right VA diameters compared with females (all P ≤ 0.02). Additionally, right VA PI was elevated in females compared with males (P = 0.01) and females had lower left ICA-MCA DF (P = 0.04), but greater right VA-Basilar DF (P = 0.04) compared with males.

Table 2.

Intracranial Cerebral Artery Measures and WMH in the Combined Group and by Sex.

| Combined n = 403 |

Females n = 272 |

Males n = 131 |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral Artery Diameter, mm | ||||

| Left ICA | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Right ICA | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Left MCA | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 0.15 |

| Right MCA | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 0.02 |

| Left VA | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 0.08 |

| Right VA | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 0.004 |

| Basilar | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 0.15 |

| Cerebral Pulsatility | ||||

| Left ICA | 1.10 ± 0.19 | 1.10 ± 0.20 | 1.11 ± 0.18 | 0.89 |

| Right ICA | 1.10 ± 0.19 | 1.10 ± 0.20 | 1.10 ± 0.17 | 0.88 |

| Left MCA | 1.18 ± 0.25 | 1.19 ± 0.26 | 1.15 ± 0.21 | 0.06 |

| Right MCA | 1.17 ± 0.23 | 1.19 ± 0.24 | 1.15 ± 0.20 | 0.13 |

| Left VA | 1.32 ± 0.34 | 1.34 ± 0.34 | 1.32 ± 0.34 | 0.58 |

| Right VA | 1.40 ± 0.36 | 1.42 ± 0.37 | 1.32 ± 0.33 | 0.01 |

| Basilar | 1.25 ± 0.26 | 1.26 ± 0.27 | 1.25 ± 0.27 | 0.62 |

| Damping Factor | ||||

| Left ICA-MCA | 0.92 ± 0.17 | 0.92 ± 0.17 | 0.96 ± 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Right ICA-MCA | 0.93 ± 0.16 | 0.92 ± 0.15 | 0.95 ± 0.18 | 0.11 |

| Left VA-Basilar | 1.09 ± 0.28 | 1.08 ± 0.26 | 1.08 ± 0.31 | 0.98 |

| Right VA-Basilar | 1.14 ± 0.27 | 1.15 ± 0.27 | 1.09 ± 0.26 | 0.04 |

| WMH Volume, mL | 1.59 ± 3.27 | 1.43 ± 3.15 | 1.59 ± 3.26 | 0.65 |

| Intracranial Volume, L | 1.44 ± 0.15 | 1.37 ± 0.11 | 1.57 ± 0.13 | <0.001 |

| WMH | 0.38 ± 0.20 | 0.39 ± 0.19 | 0.37 ± 0.21 | 0.45 |

Values are mean ± SD. ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; VA, vertebral artery; WMH, white matter hyperintensity. P value represents results of independent samples t-tests evaluating differences between females and males.

Relationships between Cerebral Hemodynamics and WMH

In the combined group, positive relationships were observed between PI and WMH in the anterior circulation including the left ICA (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.13, β = 0.36 ± 0.05), right ICA (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.13, β = 0.38 ± 0.05), left MCA (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.07, β = 0.22 ± 0.04), and right MCA (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.09, β = 0.27 ± 0.04). Positive relationships were also observed in the posterior circulation including the left VA (P = 0.004, R2 = 0.02, β = 0.09 ± 0.03), right VA (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.05, β = 0.12 ± 0.03), and basilar artery (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.04, β = 0.15 ± 0.04). In contrast, no associations were observed between ICA-MCA DF and WMH (left: P = 0.51; right: P = 0.99) or VA-Basilar DF and WMH (left: P = 0.36; right: P = 0.55). All relationships persisted when accounting for the covariates (Supplemental Table S1).

When considering the impact of biological sex on the relationships between cerebral PI and WMH, sex-specific associations were observed (Table 3). Males and females demonstrated positive relationships between PI and WMH in the left and right ICAs and MCAs. The associations did not differ between males and females in the left ICA (P = 0.97), right ICA (P = 0.47), left MCA (P = 0.38), and the right MCA (P = 0.98). In contrast, only females demonstrated positive associations between PI and WMH in the left and right VA as well as the basilar artery. When separated by sex, no associations were observed in females or males for ICA-MCA DF or VA-Basilar DF and WMH (Table 3). An additional finding from the biological sex stratification was the presence of female specific associations between MAP and WMH (females: P = 0.007 vs males: P = 0.54). All relationships persisted when accounting for the covariates (Supplemental Table S2).

Table 3.

Associations between Intracranial Hemodynamics and WMH by sex.

| Sex | R2 | β | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral Pulsatility | ||||

| Left ICA | Females | 0.14 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Males | 0.09 | 0.36 ± 0.10 | <0.001 | |

| Right ICA | Females | 0.17 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Males | 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.11 | 0.003 | |

| Left MCA | Females | 0.07 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Males | 0.07 | 0.28 ± 0.09 | 0.002 | |

| Right MCA | Females | 0.11 | 0.27 ± 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Males | 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 0.005 | |

| Left VA | Females | 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.003 |

| Males | −0.002 | 0.05 ± 0.06 | 0.38 | |

| Right VA | Females | 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Males | 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.06 | 0.08 | |

| Basilar | Females | 0.00 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Males | −0.009 | 0.01 ± 0.07 | 0.87 | |

| Damping Factor | ||||

| Left ICA-MCA | Females | 0.002 | 0.09 ± 0.07 | 0.21 |

| Males | −0.007 | −0.04 ± 0.11 | 0.70 | |

| Right ICA-MCA | Females | −0.004 | 0.003 ± 0.08 | 0.97 |

| Males | −0.009 | 0.001 ± 0.11 | 0.99 | |

| Left VA-Basilar | Females | 0.003 | −0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.18 |

| Males | −0.009 | 0.009 ± 0.06 | 0.89 | |

| Right VA-Basilar | Females | −0.003 | −0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.68 |

| Males | 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.08 | 0.16 | |

Values are mean ± SD. ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; VA, vertebral artery; Univariate linear regressions evaluated relationships between intracranial hemodynamics and WMH by sex (females: n = 272, males: n = 131).

Upon exploring interactions between age and biological sex, older males and females demonstrated positive associations between left ICA PI and WMH (Figure 1) and the associations did not differ between sexes (P = 0.70). In contrast, only older females demonstrated a positive association between right ICA PI and WMH, while there was a trend towards a positive association in older males. Additionally, middle-aged females demonstrated positive associations between left and right ICA PI and WMH while no relationships were present in middle-aged males (Figure 1). Older males and females also demonstrated positive associations between MCA PI and WMH (Figure 2) but there were no differences between sexes in the relationships (left: P = 0.73, right: P = 0.30). The link between MCA PI and WMH was also observed in middle-aged females on the right side of the brain while the relationship was not present in middle-aged males (Figure 2). The female-specific relationships in the posterior circulation were driven by older females. Specifically, older females demonstrated a positive association between left VA PI and WMH along with a trend towards a positive association between right VA PI and WMH (Figure 3). Further, older females demonstrated a positive association between basilar artery PI and WMH (Figure 4). No associations were observed between PI in the posterior circulation and WMH in older males, middle-aged females, or middle-aged males (Figures 3 and 4). Additionally, no associations were present between cerebral DF (ICA-MCA and VA-Basilar) and WMH in middle-aged females, middle-aged males, older females, or older males (all P ≥ 0.27). Most relationships persisted when accounting for the covariates (Supplemental Table S3). The association between left VA PI and WMH in older females was no longer significant when MAP, diabetes, and hypertension were included as covariates (all P ≤ 0.08). In contrast, the trending association between right VA PI and WMH in older females became significant when HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and hs-CRP were included as covariates (all P ≤ 0.03).

Figure 1.

Relationships between internal carotid artery (ICA) pulsatility index (PI) and white matter hyperintensity (WMH) by sex and age group. Univariate linear regression evaluated the associations between PI and WMH in middle-aged females (n = 145; red triangles), middle-aged males (n = 71; blue triangles), older females (n = 127; red circles), and older males (n = 60; blue circles). Older males and older females demonstrated positive associations between PI and WMH in the left ICA while only older females demonstrated positive associations in the right ICA. Middle-aged females demonstrated positive associations between left and right ICA PI and WMH while no relationships were observed in middle-aged males). Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Relationships between middle cerebral artery (MCA) pulsatility index (PI) and white matter hyperintensity (WMH) by sex and age group. Univariate linear regression evaluated the associations between PI and WMH in middle-aged females (n = 145; red triangles), middle-aged males (n = 71; blue triangles), older females (n = 127; red circles), and older males (n = 60; blue circles). Older males and older females demonstrated positive associations between PI and WMH in the left MCA and right MCA, while in middle-aged adults only females demonstrated links between right MCA PI and WMH. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Relationships between vertebral artery (VA) pulsatility index (PI) and white matter hyperintensity (WMH) by sex and age group. Univariate linear regression evaluated the associations between PI and WMH in middle-aged females (n = 145; red triangles), middle-aged males (n = 71; blue triangles), older females (n = 127; red circles), and older males (n = 60; blue circles). Older females demonstrated positive associations between left VA PI and WMH. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4.

Associations between basilar artery pulsatility index (PI) and white matter hyperintensity (WMH) by sex and age group. Univariate linear regression assessed the associations between basilar artery PI and WMH in middle-aged females (n = 145; red triangles), middle-aged males (n = 71; blue triangles), older females (n = 127; red circles), and older males (n = 60; blue circles). Older females demonstrated positive relationships between basilar artery PI and WMH. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

The present study reports on novel sex-specific relationships between cerebral PI and WM lesions in cognitively unimpaired adults. Our major findings are as follows. First, in the combined group, cerebral PI in multiple intracranial arteries (ICA, MCA, VA, basilar artery) was positively associated with WMH. Second, when considering the impact of biological sex and age, older males and females demonstrated positive associations between cerebral PI and WMH in the left ICA and the left and right MCAs. Third, female-specific relationships were observed in older females between PI, in the basilar artery left VA, and WMH, and in middle-aged females between PI, in the left and right ICAs and right MCA, and WMH. Therefore, cerebral PI represents an important vascular marker that is positively associated with WM lesions in aging adults. Females appear to be more sensitive to elevations in cerebral PI earlier in life with positive relationships emerging in middle age in the anterior circulation (ICAs & MCAs). Additionally, females appear to be more sensitive to elevations in cerebral PI in the posterior circulation (basilar artery, left VA) as associations were present in older females while no associations were observed in older males. . We speculate that the longer exposure to the detrimental effects of elevated cerebral PI on WM health may in part explain the higher prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in older females. Overall, the present findings provide insight into vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia.

Cerebral Hemodynamics and White Matter Hyperintensities

Cerebral small vessel disease, characterized by damage to the small cerebral vessels, is a leading contributor to vascular cognitive impairment and dementia (4). Damage to the cerebral small vessels contributes to adverse brain structural changes observed with MRI including WMH (4). While pathological processes underlying cerebral small vessel disease are diverse, vessel stiffening and transmission of elevated blood flow pulsatility into the cerebral microvasculature may be a contributor to small vessel damage and WMH. The findings from the present study are consistent with previous work, which demonstrate positive associations between MCA PI and WMH severity (17, 45-47). However, when considering the impact of age, associations between cerebral PI and WMH were no longer significant (45, 47) and MCA PI was not associated with WMH progression over time (47). Notably, these previous studies utilized TCD ultrasound for measures of PI, which is limited to measuring blood velocity typically through one cerebral artery. The present study expands on the earlier findings by utilizing 4D flow MRI, which captures cerebral artery blood flow measurements and variations in cerebral artery diameter in multiple intracranial arteries. Further, we recently demonstrated that 4D flow MRI is more sensitive to age-related changes in blood flow and PI than TCD (18). Therefore, using measures of blood flow pulsatility in the present study, positive associations between cerebral PI and WMH were observed in the combined group in multiple arteries including the left and right ICA, left and right MCA, left and right VA, and basilar artery. These findings agree with previous TCD studies (17, 45, 46) and MRI work (19), while also expanding to additional vessels beyond the ICA and MCA. In contrast to previous work with TCD (45, 47), the relationships between cerebral PI, measured with 4D flow MRI, and WMH persisted when accounting for age in the anterior circulation (ICA and MCA). This finding is consistent with a previous MRI study by Pahlavian and colleagues (19). Importantly, the link between elevated cerebral PI and increased WMH is present in cognitively unimpaired middle-aged and older adults with low vascular risk. While associations were present between cerebral PI and WMH, relationships were not observed between cerebral DF and WMH. This finding contrasts with a previous investigation demonstrating an inverse relationship between cerebral DF and number of enlarged perivascular spaces, an index of cerebral small vessel disease (48). However, this previous investigation evaluated DF between the MCA and the downstream lenticulostriate artery and impairments in cerebral DF may be evident in the smaller downstream vessels prior to the proximal vessels.

Regional Variations in Associations between Cerebral Hemodynamics and WMH

Cerebral PI varies across the large cerebral arteries (49). 4D flow MRI provides a powerful tool to evaluate cerebral PI in multiple intracranial arteries, which may provide novel insights into regional effects of elevated cerebral PI and WM integrity. Previously, regional differences were identified when evaluating the link between cerebral PI, measured with TCD, and WM integrity (16). The present study provides novel insight into regional variations in associations between cerebral PI, measured with 4D flow MRI, and WMH. Specifically, in the combined group, stronger associations were observed between cerebral PI and WMH in the anterior circulation (ICA and MCA) compared with the posterior circulation (VA and basilar artery) despite lower PI in the ICA and MCA than in the VA and basilar artery. Taken together, these findings could suggest that the anterior microcirculation may be more sensitive to elevated cerebral PI with advancing age than the posterior microcirculation. The stronger associations between cerebral PI and WMH in the anterior circulation may be related to a higher distribution of blood flow in the anterior circulation relative to the posterior circulation (49, 50) paired with lower pulsatile damping that may occur in the anterior circulation. A previous investigation by Zarrinkoob and colleagues (51) reported on damping factor in the branches of the ICA and branches of the VA. While this investigation did not statistically compare pulsatile damping between the anterior and posterior circulation, it appeared that the posterior circulation was able to damp pulsatile flow to a greater extent than the anterior circulation. Indeed, in the present cohort, VA-Basilar DF was statistically greater than ICA-MCA DF on both sides of the brain (both P < 0.001). Additionally, the white matter in the anterior regions of the brain may be more vulnerable to deterioration. Indeed, previous investigations into regional differences in WM burden have demonstrated that the corpus callosum and the prefrontal cortex are two areas that appear most sensitive to WM changes with age (52-54). Therefore, the present findings provide early evidence that elevations in cerebral PI have greater deleterious effects on WM health in the anterior portions of the brain.

Sex Differences in Associations between Cerebral Hemodynamics and WMH

Sex hormones play a key role in vascular control (55, 56). Accordingly, sex differences are observed in cerebral hemodynamics including cerebral PI (22). In addition, sex differences are apparent in WM burden in aging adults, whereby females demonstrate greater WMH severity (57, 58). Therefore, understanding the impact of biological sex on associations between cerebral hemodynamics and WMH is critical for understanding sex differences in cognitive decline with advancing age (59). Previously, in patients with transient ischemic attack or ischemic strokes, biological sex did not influence the association between ICA PI and WMH (60). In contrast, in patients with intracranial arterial stenosis, males demonstrated associations between intracranial PI and WMH whereas females did not (45). To the best of our knowledge, the present study represents the first to demonstrate novel sex differences in the association between cerebral PI and WMH in healthy, cognitively unimpaired adults. Positive associations between cerebral PI in the anterior circulation (left and right ICA, left and right MCA) and WMH were present in both males and females. The relationships between cerebral PI and WMH in the ICAs and MCAs did not differ between males and females. In the posterior circulation (left and right VA, basilar artery), only females demonstrated positive associations between cerebral PI and WMH while no relationships were present in males. We postulate that these findings may suggest that elevations in cerebral PI in the posterior circulation may occur earlier in life in females than in males leading to WM lesions in the posterior aspects of the brain. We suspect that, in line with the timing effects observed in the anterior circulation, associations between cerebral PI in the posterior circulation and WMH may emerge in males later in life than what we have captured in the present cohort. Further, these findings suggest that elevations in cerebral PI represent an early risk factor for cognitive decline in aging adults, more so in females as relationships between cerebral PI and WMH emerged in middle-age in females and not until older age in males.

Interactive Effects of Age and Sex

Age-related changes in cerebral hemodynamics differ by biological sex whereby females demonstrate steeper rates of incline in cerebral PI over the adult lifespan (22). Therefore, variations in associations between cerebral hemodynamics and WMH by biological sex may be impacted by age. Older males and females demonstrated positive associations between cerebral PI and WMH in the left ICA and the MCAs, but these associations did not differ between sexes. In contrast, only older females demonstrated a positive association between right ICA PI and WMH. Further, middle-aged females demonstrated a positive association between PI in the ICAs and right MCA PI and WMH. Middle-aged males did not demonstrate associations between cerebral PI and WMH in any vessel. Additionally, only older females demonstrated an association between left VA and basilar artery PI and WMH. Taken together, these findings may suggest that females are more sensitive to elevations in cerebral PI earlier in the adult lifespan than males. Additionally, while WM in anterior brain regions are more likely affected than posterior brain regions (52-54), females may demonstrate early sensitivity to elevations in cerebral PI in the posterior circulation. Overall, we report on novel sex differences in the association between cerebral PI and WMH whereby earlier associations in females may explain differences in the prevalence and severity of AD and related dementias with advancing age between males and females.

Mechanisms Contributing to Sex Differences

Many factors may contribute to the observed sex differences in the associations between cerebral hemodynamics and WMH in the present study. Despite sex differences in the association between cerebral PI and WMH, there were no sex differences in cerebral PI in the ICAs, MCAs, left VA, and basilar artery. In contrast, females demonstrated greater PI in the right VA compared with males. This may contribute to the female-specific associations observed between basilar artery PI and WMH, despite greater right VA-Basilar DF in females. Additional sex differences were observed in cerebral DF whereby females demonstrated lower left ICA-MCA DF compared with males. The lower left ICA-MCA DF may contribute to transmission of greater cerebral PI into the downstream vessels in females.

APOE ε4 represents a significant risk factor for cerebrovascular dysregulation (37, 38) and WMH status (39, 40). Furthermore, the adverse cerebrovascular outcomes associated with APOE appear to be greater in females than males as female APOE ε4 carriers demonstrated greater age-related declines in cerebral perfusion than male APOE ε4 carriers while no sex differences were observed in non-carriers (61). As such, the female-specific associations between cerebral PI and WMH in middle-age, and in the posterior circulation, may be related to APOE ε4. However, no sex differences were observed in APOE status in the present investigation and inclusion of APOE status as a covariate did not alter the results.

Blood pressure is a significant predictor of WMH (35, 62) and sex differences were observed in resting blood pressure whereby males demonstrated higher SBP and MAP. However, the slopes of associations between cerebral PI and WMH were not different between males and females. Additionally, all relationships between cerebral PI and WMH persisted when accounting for resting MAP, except for the association between left VA and WMH in older females (P = 0.055). Nonetheless, this suggests that blood pressure is not the primary driving factor underlying the sex differences observed in the present study as associations persisted in the ICAs, MCAs, right VA, and basilar artery. Interestingly, when MAP was included in the model, other sex differences emerged such that MAP was a significant predictor of WMH in females only. This finding aligns with previous work demonstrating that blood pressure had stronger effects on WM health in females compared with males (63-65). Presence of hypertension was also included in the model and did not influence the results with the exception that the association between left VA PI and WMH was lost in the older females (P = 0.06). In addition to sex differences in resting blood pressure, variations in resting HR may influence the findings as females demonstrated higher resting HR compared with males. However, associations between cerebral hemodynamics and WMH persisted when resting HR was considered in the model.

Additional cardiovascular risk factors beyond blood pressure may influence the relationships between cerebral PI and WMH and the observed sex differences. In particular, diabetes and cholesterol levels have deleterious effects on cerebrovascular dysfunction and WM structure (42, 66, 67). However, there were no differences in presence of diabetes between males and females and the inclusion of diabetes did not impact the findings of the present study with the exception that association between left VA PI and WMH was no longer significant in the older females (P = 0.08). In the present cohort, females had greater total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, while also having greater high-density lipoprotein cholesterol compared with males. However, when cholesterol levels were included as covariates, the results remained similar. The association between right VA PI and WMH, which was trending in the univariate analysis, became significant in older females (all P ≤ 0.03). A similar finding was observed when inflammatory marker hs-CRP was included in the model whereby older females demonstrated significant associations between right VA PI and WMH (P = 0.03) while all other results remained the same. Therefore, the associations between cerebral PI and WMH were not influenced by cardiovascular risk factors suggesting that sex differences in cerebral hemodynamics may be driving the associations.

Estrogen is vasoprotective and the significant reduction in estrogen with menopause elicits vascular dysfunction in females. Indeed, the trajectory of vascular changes with advancing age becomes markedly steeper around the age at menopause (22, 68). Therefore, while cerebral PI may not differ between males and females in the present study, it is possible that the females have undergone larger increases in cerebral PI relative to males. This may also be the case with blood pressure where, although lower in females compared with males, females likely experience larger increases in blood pressure over the lifespan (68) which may explain the female-specific link between resting MAP and WMH in the present study. The detrimental effects of menopause-mediated reductions in estrogen on vascular function may occur through direct vascular effects or through impaired autonomic regulation (e.g., central sympathoexcitation, altered baroreflex function, augmented vascular transduction) (69), endothelial dysfunction (e.g., reduced estrogen receptor α expression, reduced nitric oxide production) (56), and inflammation (e.g., tumor necrosis factor α) (25). Overall, the change in vascular function over time that females experience during the menopause transition may have a greater effect on WM health compared with the change that males of a similar age typically experience.

Study Limitations

There are methodological considerations for the present study. First, the laboratory and MRI visits occurred on separate days in many participants. As such, resting hemodynamic and blood data may not have been collected on the same day as MRI data. However, the length of time between visits was 2.4 ± 4.4 months and this is not expected to have significantly influenced the results in the present study. Second, menopausal status is an important consideration as menopause is a biological process specific to females during middle age and is associated with deleterious effects on vascular health and function. However, menopause status was not available in the present retrospective analysis. Based on the average age for menopause in the US (70-72), it is estimated that a majority of female participants in the present study were post menopause (n = 253 >52 years of age). However, it is possible that some female participants in the middle-age group were pre- or peri-menopausal whereby inter-individual variations in sex hormones could influence cerebral PI and its association to WMH. Future research should address the contribution of menopause, independent of age, to the association between cerebral PI and WMH by stratifying females by menopausal status and matching for age or considering the impact of age since menopause on the relationships. Third, males were underrepresented in the present cohort (33%), which is consistent with the Wisconsin ADRC cohort. To consider the impact of uneven samples of males and females, bootstrapping analysis was performed. The results persisted with bootstrapping, suggesting that the fewer number of males included in the present analysis did not influence the results. Fourth, different head coils were utilized in the present cohort which may contribute to variations in noise levels in the MRI scans, particularly when comparing the 8-channel coil to the 32- and 48-channel head coils. However, the 8-channel head coil was only utilized in less than 5% of participants and the removal of these participants from the cohort does not alter the results. Fifth, given the retrospective nature of the present study, information regarding physical activity levels and sleeping patterns were not available in the present cohort. Future work should address the impact of physical activity on the associations between cerebral pulsatility and WMH and consider sleep patterns as a potential confounder.

Conclusions

In summary, we report that cerebral hemodynamics are associated with detrimental changes in WM structure. Specifically, elevated cerebral PI is associated with greater WM lesions. Importantly, biological sex influences the relationships between cerebral hemodynamics and WMH. While both sexes demonstrated associations between cerebral PI in the anterior circulation (ICA, MCA) and WMH, female specific relationships were observed in the posterior circulation between VA and basilar artery PI and WMH. Additionally, associations between ICA PI and right MCA PI and WMH were present in middle-aged females. In contrast, no relationships between cerebral PI and WMH were present in middle-aged males. Taken together, these findings suggest that elevations in cerebral PI have greater detrimental effects on WM integrity in females earlier in life. Collectively, these findings contribute to our understanding of underlying cerebrovascular mechanisms contributing to brain structural changes and may have important implications for mitigating cognitive decline with advancing age.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Tables S1-S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28839845.v1

Acknowledgements

Summary Figure: Created in BioRender. Moir, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/edptbs5

Grants

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants (R03 AG070469-01 and R03 AG070469-S1 to JNB; P30-AG062715 to the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center; T32HL007936 to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Cardiovascular Research Center [to SHAGM]), a Virginia Horne Henry Research grant to JNB, and an Alzheimer’s Association Research Fellowship (AARF-22-924325 to BGF).

Footnotes

Disclosures

SCJ serves as a consultant to Enigma Biomedical and ALZPath. No other conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Tai SY, Chi YC, Lo YT, Chien YW, Kwachi I, and Lu TH. Ranking of Alzheimer's disease and related dementia among the leading causes of death in the US varies depending on NCHS or WHO definitions. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 15: e12442, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer's disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 5: 347–360, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L-J, Tian D-C, Yang L, Shi K, Liu Y, Wang Y, and Shi F-D. White matter disease derived from vascular and demyelinating origins. Stroke and Vascular Neurology svn-2023-002791, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markus HS, and de Leeuw FE. Cerebral small vessel disease: recent advances and future directions. International Journal of Stroke 18: 4–14, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hainsworth AH, Markus HS, and Schneider JA. Cerebral Small Vessel Disease, Hypertension, and Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Hypertension 81: 75–86, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadjichrysanthou C, Evans S, Bajaj S, Siakallis LC, McRae-McKee K, De Wolf F, Anderson RM, and Initiative AsDN. The dynamics of biomarkers across the clinical spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy 12: 1–16, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birdsill AC, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Johnson SC, Okonkwo OC, Hermann BP, LaRue A, Sager MA, and Bendlin BB. Regional white matter hyperintensities: aging, Alzheimer's disease risk, and cognitive function. Neurobiology of Aging 35: 769–776, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bown CW, Khan OA, Moore EE, Liu D, Pechman KR, Cambronero FE, Terry JG, Nair S, Davis LT, and Gifford KA. Elevated aortic pulse wave velocity relates to longitudinal gray and white matter changes. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 41: 3015–3024, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosano C, Watson N, Chang Y, Newman AB, Aizenstein HJ, Du Y, Venkatraman V, Harris TB, Barinas-Mitchell E, and Sutton-Tyrrell K. Aortic pulse wave velocity predicts focal white matter hyperintensities in a biracial cohort of older adults. Hypertension 61: 160–165, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Björnfot C, Garpebring A, Qvarlander S, Malm J, Eklund A, and Wåhlin A. Assessing cerebral arterial pulse wave velocity using 4D flow MRI. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 41: 2769–2777, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan L, Liu CY, Smith RX, Jog M, Langham M, Krasileva K, Chen Y, Ringman JM, and Wang DJ. Assessing intracranial vascular compliance using dynamic arterial spin labeling. Neuroimage 124: 433–441, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fico BG, Miller KB, Rivera-Rivera LA, Corkery AT, Pearson AG, Eisenmann NA, Howery AJ, Rowley HA, Johnson KM, and Johnson SC. The impact of aging on the association between aortic stiffness and cerebral pulsatility index. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 9: 821151, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wardlaw JM, Valdés Hernández MC, and Muñoz-Maniega S. What are white matter hyperintensities made of? Relevance to vascular cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Heart Association 4: e001140, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birnefeld J, Wåhlin A, Eklund A, and Malm J. Cerebral arterial pulsatility is associated with features of small vessel disease in patients with acute stroke and TIA: a 4D flow MRI study. Journal of Neurology 267: 721–730, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb AJ, Simoni M, Mazzucco S, Kuker W, Schulz U, and Rothwell PM. Increased cerebral arterial pulsatility in patients with leukoaraiosis: arterial stiffness enhances transmission of aortic pulsatility. Stroke 43: 2631–2636, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleysher R, Lipton ML, Noskin O, Rundek T, Lipton R, and Derby CA. White matter structural integrity and transcranial Doppler blood flow pulsatility in normal aging. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 47: 97–102, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purkayastha S, Fadar O, Mehregan A, Salat DH, Moscufo N, Meier DS, Guttmann CR, Fisher ND, Lipsitz LA, and Sorond FA. Impaired cerebrovascular hemodynamics are associated with cerebral white matter damage. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 34: 228–234, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fico BG, Miller KB, Rivera-Rivera LA, Corkery AT, Pearson AG, Loggie NA, Howery AJ, Rowley HA, Johnson KM, and Johnson SC. Cerebral hemodynamics comparison using transcranial doppler ultrasound and 4D flow MRI. Frontiers in Physiology 14: 1198615, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pahlavian SH, Wang X, Ma S, Zheng H, Casey M, D’Orazio LM, Shao X, Ringman JM, Chui H, and Wang DJ. Cerebroarterial pulsatility and resistivity indices are associated with cognitive impairment and white matter hyperintensity in elderly subjects: A phase-contrast MRI study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 41: 670–683, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jolly TA, Bateman GA, Levi CR, Parsons MW, Michie PT, and Karayanidis F. Early detection of microstructural white matter changes associated with arterial pulsatility. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7: 782, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Björnfot C, Eklund A, Larsson J, Hansson W, Birnefeld J, Garpebring A, Qvarlander S, Koskinen L-OD, Malm J, and Wåhlin A. Cerebral arterial stiffness is linked to white matter hyperintensities and perivascular spaces in older adults–A 4D flow MRI study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 0271678X241230741, 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alwatban MR, Aaron SE, Kaufman CS, Barnes JN, Brassard P, Ward JL, Miller KB, Howery AJ, Labrecque L, and Billinger SA. Effects of age and sex on middle cerebral artery blood velocity and flow pulsatility index across the adult lifespan. Journal of Applied Physiology 130: 1675–1683, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buckley RF, Gong J, and Woodward M. A call to action to address sex differences in Alzheimer disease clinical trials. JAMA Neurology 80: 769–770, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro-Aldrete L, Moser MV, Putignano G, Ferretti MT, Schumacher Dimech A, and Santuccione Chadha A. Sex and gender considerations in Alzheimer’s disease: The Women’s Brain Project contribution. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 15: 1105620, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreau KL, and Hildreth KL. Vascular aging across the menopause transition in healthy women. Advances in Vascular Medicine 2014: 204390, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, and Mayeux R. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia 7: 263–269, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, and Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia 7: 270–279, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson SC, La Rue A, Hermann BP, Xu G, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Bendlin BB, Hogan KJ, Roses AD, and Saunders AM. The effect of TOMM40 poly-T length on gray matter volume and cognition in middle-aged persons with APOE ε3/ε3 genotype. Alzheimer's & Dementia 7: 456–465, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson KM, Lum DP, Turski PA, Block WF, Mistretta CA, and Wieben O. Improved 3D phase contrast MRI with off-resonance corrected dual echo VIPR. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 60: 1329–1336, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu T, Korosec FR, Block WF, Fain SB, Turk Q, Lum D, Zhou Y, Grist TM, Haughton V, and Mistretta CA. PC VIPR: a high-speed 3D phase-contrast method for flow quantification and high-resolution angiography. American Journal of Neuroradiology 26: 743–749, 2005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller KB, Howery AJ, Rivera-Rivera LA, Johnson SC, Rowley HA, Wieben O, and Barnes JN. Age-related reductions in cerebrovascular reactivity using 4D flow MRI. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 11: 281, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson AG, Miller KB, Corkery AT, Eisenmann NA, Howery AJ, Cody KA, Chin NA, Johnson SC, and Barnes JN. Sympathoexcitatory Responses to Isometric Handgrip Exercise Are Associated With White Matter Hyperintensities in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 14: 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loecher M, Schrauben E, Johnson KM, and Wieben O. Phase unwrapping in 4D MR flow with a 4D single-step laplacian algorithm. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 43: 833–842, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts GS, Hoffman CA, Rivera-Rivera LA, Berman SE, Eisenmenger LB, and Wieben O. Automated hemodynamic assessment for cranial 4D flow MRI. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 97: 46–55, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wartolowska KA, and Webb AJ. Blood pressure determinants of cerebral white matter hyperintensities and microstructural injury: UK Biobank Cohort Study. Hypertension 78: 532–539, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuhrmann D, Nesbitt D, Shafto M, Rowe JB, Price D, Gadie A, Tyler LK, Brayne C, Bullmore ET, and Calder AC. Strong and specific associations between cardiovascular risk factors and white matter micro-and macrostructure in healthy aging. Neurobiology of Aging 74: 46–55, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suri S, Mackay CE, Kelly ME, Germuska M, Tunbridge EM, Frisoni GB, Matthews PM, Ebmeier KP, Bulte DP, and Filippini N. Reduced cerebrovascular reactivity in young adults carrying the APOE ε4 allele. Alzheimer's & Dementia 11: 648–657. e641, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koizumi K, Hattori Y, Ahn SJ, Buendia I, Ciacciarelli A, Uekawa K, Wang G, Hiller A, Zhao L, and Voss HU. Apoε4 disrupts neurovascular regulation and undermines white matter integrity and cognitive function. Nature Communications 9: 3816, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyall DM, Cox SR, Lyall LM, Celis-Morales C, Cullen B, Mackay DF, Ward J, Strawbridge RJ, McIntosh AM, and Sattar N. Association between APOE e4 and white matter hyperintensity volume, but not total brain volume or white matter integrity. Brain Imaging and Behavior 14: 1468–1476, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rojas S, Brugulat-Serrat A, Bargallo N, Minguillón C, Tucholka A, Falcon C, Carvalho A, Morán S, Esteller M, and Gramunt N. Higher prevalence of cerebral white matter hyperintensities in homozygous APOE-ε4 allele carriers aged 45–75: Results from the ALFA study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 38: 250–261, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King KS, Peshock RM, Rossetti HC, McColl RW, Ayers CR, Hulsey KM, and Das SR. Effect of normal aging versus hypertension, abnormal body mass index, and diabetes mellitus on white matter hyperintensity volume. Stroke 45: 255–257, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iriondo A, García-Sebastian M, Arrospide A, Arriba M, Aurtenetxe S, Barandiaran M, Clerigue M, Ecay-Torres M, Estanga A, and Gabilondo A. Plasma lipids are associated with white matter microstructural changes and axonal degeneration. Brain Imaging and Behavior 15: 1043–1057, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiao Y, Zhao L, Cong C, Li Y, Tian S, Zhu X, Yang J, Cao S, Li P, and Su J. Association of systemic inflammatory markers with white matter hyperintensities and microstructural injury: an analysis of UK Biobank data. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 50: E45–E56, 2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogundimu EO, Altman DG, and Collins GS. Adequate sample size for developing prediction models is not simply related to events per variable. Journal of clinical epidemiology 76: 175–182, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y, Dang L, Tian X, Yang M, Lv M, Sun Q, and Du Y. Association between intracranial Pulsatility and white matter Hyperintensities in asymptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis: A population-based study in Shandong, China. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 31: 106406, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu S, Zhang J, Zhang H, and Zhang S. Predictive value of transcranial doppler ultrasound for cerebral small vessel disease in elderly patients. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria 77: 310–314, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kneihsl M, Hofer E, Enzinger C, Niederkorn K, Horner S, Pinter D, Fandler-Hoefler S, Eppinger S, Haidegger M, and Schmidt R. Intracranial pulsatility in relation to severity and progression of cerebral white matter hyperintensities. Stroke 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van den Kerkhof M, van der Thiel MM, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Postma AA, Kroon AA, Backes WH, and Jansen JF. Impaired damping of cerebral blood flow velocity pulsatility is associated with the number of perivascular spaces as measured with 7T MRI. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 43: 937–946, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roberts GS, Peret A, Jonaitis EM, Koscik RL, Hoffman CA, Rivera-Rivera LA, Cody KA, Rowley HA, Johnson SC, and Wieben O. Normative cerebral hemodynamics in middle-aged and older adults using 4D flow MRI: initial analysis of vascular aging. Radiology 307: e222685, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zarrinkoob L, Ambarki K, Wåhlin A, Birgander R, Eklund A, and Malm J. Blood flow distribution in cerebral arteries. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 35: 648–654, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zarrinkoob L, Ambarki K, Wåhlin A, Birgander R, Carlberg B, Eklund A, and Malm J. Aging alters the dampening of pulsatile blood flow in cerebral arteries. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 36: 1519–1527, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kennedy KM, and Raz N. Pattern of normal age-related regional differences in white matter microstructure is modified by vascular risk. Brain Research 1297: 41–56, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tullberg M, Fletcher E, DeCarli C, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey DJ, Weiner MW, Chui HC, and Jagust WJ. White matter lesions impair frontal lobe function regardless of their location. Neurology 63: 246–253, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salat DH, Greve DN, Pacheco JL, Quinn BT, Helmer KG, Buckner RL, and Fischl B. Regional white matter volume differences in nondemented aging and Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage 44: 1247–1258, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barnes JN. Sex-specific factors regulating pressure and flow. Experimental Physiology 102: 1385–1392, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stanhewicz AE, Wenner MM, and Stachenfeld NS. Sex differences in endothelial function important to vascular health and overall cardiovascular disease risk across the lifespan. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 315: H1569–H1588, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sachdev PS, Parslow R, Wen W, Anstey K, and Easteal S. Sex differences in the causes and consequences of white matter hyperintensities. Neurobiology of Aging 30: 946–956, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alqarni A, Jiang J, Crawford JD, Koch F, Brodaty H, Sachdev P, and Wen W. Sex differences in risk factors for white matter hyperintensities in non-demented older individuals. Neurobiology of Aging 98: 197–204, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levine DA, Gross AL, Briceño EM, Tilton N, Giordani BJ, Sussman JB, Hayward RA, Burke JF, Hingtgen S, and Elkind MS. Sex differences in cognitive decline among US adults. JAMA Network Open 4: e210169–e210169, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lau KK, Pego P, Mazzucco S, Li L, Howard DP, Küker W, and Rothwell PM. Age and sex-specific associations of carotid pulsatility with small vessel disease burden in transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke. International Journal of Stroke 13: 832–839, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang R, Oh JM, Motovylyak A, Ma Y, Sager MA, Rowley HA, Johnson KM, Gallagher CL, Carlsson CM, and Bendlin BB. Impact of sex and APOE ε4 on age-related cerebral perfusion trajectories in cognitively asymptomatic middle-aged and older adults: a longitudinal study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 41: 3016–3027, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wartolowska KA, and Webb AJS. Midlife blood pressure is associated with the severity of white matter hyperintensities: analysis of the UK Biobank cohort study. European Heart Journal 42: 750–757, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reas ET, Laughlin GA, Hagler DJ Jr, Lee RR, Dale AM, and McEvoy LK. Age and sex differences in the associations of pulse pressure with white matter and subcortical microstructure. Hypertension 77: 938–947, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bonberg N, Wulms N, Dehghan-Nayyeri M, Berger K, and Minnerup H. Sex-specific causes and consequences of white matter damage in a middle-aged cohort. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 14: 810296, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lohner V, Pehlivan G, Sanroma G, Miloschewski A, Schirmer MD, Stöcker T, Reuter M, and Breteler MM. Relation between sex, menopause, and white matter hyperintensities: the Rhineland study. Neurology 99: e935–e943, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grosu S, Lorbeer R, Hartmann F, Rospleszcz S, Bamberg F, Schlett CL, Galie F, Selder S, Auweter S, and Heier M. White matter hyperintensity volume in pre-diabetes, diabetes and normoglycemia. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 9: e002050, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bill O, Mazya MV, Michel P, Prazeres Moreira T, Lambrou D, Meyer IA, and Hirt L. Intima-media thickness and pulsatility index of common carotid arteries in acute ischaemic stroke patients with diabetes mellitus. Journal of Clinical Medicine 12: 246, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ji H, Kim A, Ebinger JE, Niiranen TJ, Claggett BL, Merz CNB, and Cheng S. Sex differences in blood pressure trajectories over the life course. JAMA Cardiology 5: 255–262, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Joyner MJ, Barnes JN, Hart EC, Wallin BG, and Charkoudian N. Neural control of the circulation: how sex and age differences interact in humans. Comprehensive Physiology 5: 193, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reynolds RF, and Obermeyer CM. Age at natural menopause in Spain and the United States: results from the DAMES project. American Journal of Human Biology 17: 331–340, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gold EB, Crawford SL, Avis NE, Crandall CJ, Matthews KA, Waetjen LE, Lee JS, Thurston R, Vuga M, and Harlow SD. Factors related to age at natural menopause: longitudinal analyses from SWAN. American Journal of Epidemiology 178: 70–83, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gold EB. The timing of the age at which natural menopause occurs. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics 38: 425–440, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.