Abstract

Robust and accurate quantification of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors’ infectivity is essential for pre-clinical and clinical development of AAV gene therapy programs. The industry standard method for rAAV titration is the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay using HeLa-based cell lines that stably encode the rep and cap genes from AAV serotype 2. Co-infection with wild-type (WT) adenoviruses provides the helper functions for expression of these genes, and the use of quantitative PCR (qPCR)/droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) serves as the endpoint method for the detection of infectious events. However, TCID50 assays using these HeLa-based rep cap trans-complementing cell lines have traditionally been regarded as challenging due to high variability, stability of the integrated genes, and safety concerns associated with the use of WT helper viruses. Here we developed a novel method for infectious titration of rAAV using our vector “tetracycline-enabled self-silencing adenovirus” (TESSA); we engineered it to deliver and express the AAV2 rep genes and adenoviral helper functions for rAAV genome replication, independent of the cell type. This approach allows the infectious titration of rAAV serotypes in cell lines permissive to adenovirus but without the production of adenoviral particles for improved safety, therefore benefiting GMP analytical requirements for rAAV gene therapies.

Keywords: rAAV, infectious titer, TCID50, TESSA, TREAT assay

Graphical abstract

Infectious titration of rAAV is essential for gene therapy development and drug product release. Su and colleagues describe a novel rAAV infectious assay based on the TESSA adenoviral platform to deliver all necessary AAV genes and helper functions, enabling accurate rAAV titration in various cell types, while enhancing safety and reproducibility.

Introduction

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors have shown significant promise for clinical in vivo gene therapy because of their high safety profile, minimal toxicity, vast tropism, and potential to mediate persistent long-term gene expression. Currently, seven rAAV gene therapy drugs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical use and rAAV vectors have been administered in over 300 clinical trials (FDA.gov, accessed on 29.04.2025; and clinicaltrials.gov, accessed on 02.02.2025).1

Recombinant AAV process development for gene therapy requires step-by-step characterization and quantification of upstream and downstream process materials to enable iterative improvement in rAAV yields, purity, and vector potency. Determination of vector genome titer is mostly carried out by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), while ELISA is generally used to determine particle titers. Analytical ultracentrifugation is considered the gold standard for characterizing rAAV particles’ quality and fullness (full, partial, and empty).2,3,4 Recently, new scalable systems have made it possible to increase the rAAV particle output per cell, and the particle-to-infectivity (P:I) ratio has decreased as purification methods have evolved. Development of accurate and robust analytics assays is important to support rAAV gene therapy developments.5,6,7,8,9,10

AAV infectivity depends on several key steps, including cell receptor binding and entry, conversion of the single-stranded genome to double-stranded DNA, and the expression of functional proteins needed for viral replication. As a result, rAAV titration methods based solely on transduction readouts (such as reporter or therapeutic transgene expression) do not directly measure the concentration of functional rAAV particles. These methods often underestimate the actual infectious titer, as successful transduction requires the target cell to be permissive to AAV entry and transgene expression.11,12,13,14 Additionally, transduction-based rAAV titration can be particularly challenging if sensitive methods for detecting transgene expression, or its activity, are not readily available. Most titering techniques depend on replication or “amplification” of the rAAV vector genome within the cell for reliable detection. As rAAV vectors are replication-incompetent, this amplification relies on the presence of AAV rep and cap genes alongside the helper adenovirus functions. This step increases the sensitivity of the titering assay and enhances the reliability of determining the infectivity of an rAAV vector stock.15,16,17

The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay is an in vitro cell-based quantitative method widely used to determine the concentration of viral vector required to infect 50% of inoculated cells. To detect and quantify rAAV replication, this assay generally employs specifically engineered HeLa-based cell lines (HeLaRC32, C12, and D7-4 cells) stably expressing the Rep and Cap genes necessary for AAV replication and packaging.16,17,18,19 These engineered cells are co-inoculated with serial dilutions of the rAAV vector test sample and helper wild-type (WT) adenovirus type 5 (Ad5), providing essential components to support rAAV replication. As AAV infection does not induce cytopathic effects (CPE) in infected cells, the rAAV TCID50 assay uses qPCR or ddPCR as an endpoint method to quantify the replicated viral genome for detection of infection events in the inoculated wells of a 96-well tissue culture plate. While the rAAV TCID50 assay is important for rAAV process development and to ensure batch-to-batch consistency, it has also traditionally been viewed as challenging due to high variability, with coefficient of variation (CV) values of up to 60% between individual runs.16,20 These challenges can be further compounded by variations between testing laboratories, different HeLa rep/cap cell lines, stability of the rep cap genes at passage, and potency of different WT Ad helpers. Additionally, the requirements for sourcing the HeLa rep cap trans-complementing cells and safety concerns associated with using infectious WT Ad limit their adoption to non-specialized laboratories. Improvements in the precision and robustness of the rAAV TCID50 assay will reduce titration variability between different laboratories and facilitate AAV gene therapy development and product release.

Previously, we developed the “tetracycline-enabled self-silencing adenovirus” (TESSA) platform for rAAV manufacture in mammalian cells. The TESSA vectors are engineered E1/E3-deleted Ad5 vectors, wherein the major late promoter (MLP) is modified to include a repressor-binding site (tetracycline operator, TetO) and where the repressor (TetR) is encoded under MLP transcription. This genetic modification enables TESSA vectors to replicate its viral genome in both the presence and absence of doxycycline, but tight repression of adenovirus structural genes in its absence. Additionally, we stably encoded AAV rep and cap genes into the TESSA vector, providing all the necessary helper functionality for rAAV vector replication.21,22,23,24 As TESSA vectors can be employed for inducing rAAV replication in target cells, we show here the development and application of the TESSA Rep-enabled AAV titration “TREAT” assay for sensitive and robust infectious titration of rAAV vectors. The TREAT assay employs a self-repressing TESSA virus that expresses the adenovirus E1 genes and AAV rep to supply the necessary components required to replicate the rAAV genome and enables quantification of infectious rAAV in various target cells via the TCID50 assay. In this work, we assessed the TREAT assay’s specificity, linearity, precision, and acceptance criteria as qualification parameters for infectious titration of rAAV via the TCID50 method.

Results

TESSA vector encoding E1 and AAV Rep enables rAAV genome replication

We previously introduced the TESSA platform, based on first generation E1/E3-deleted Ad5, to produce rAAV vectors in mammalian HEK293 cells. In this system, while the Ad5 helper genes (E4Orf6, VA RNA, and E2A) and AAV rep cap are provided by the TESSA vector, the Ad5 E1 genes are supplied from the HEK293 cells.21 To enable rAAV genome replication in non-HEK293 target cells (i.e., cells lacking Ad5 E1) for complementing the TREAT assay, we engineered the TESSA virus to encode AAV2 rep and Ad5 E1 (TESSA-E1-Rep, Figure 1A). We first evaluated rAAV genome replication in the target cells by co-infection with TESSA-E1-Rep. As shown in Figure 1B, A549 (lung carcinoma epithelial cells) cells were infected with rAAV2-EGFP only at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 GC/cell, or co-infected with either TESSA-E1-Rep or the control viruses (Ad5-E1, TESSA-E1, or TESSA-Rep). Genomic DNA was harvested at the indicated time point post-infection and quantified by EGFP-specific qPCR. At 24 h post-infection (hpi), we observed an over 2-log increase in rAAV2-EGFP genome replication in cells co-infected with TESSA-E1-Rep, compared to rAAV2-EGFP alone or co-infected with the control viruses. At 48 hpi, replication of the rAAV2-EGFP, by TESSA-E1-Rep, increased to over 4,000-fold and plateaued at 72 hpi and 96 hpi. As expected, replication of rAAV2-EGFP was not observed in cells infected with rAAV2-EGFP alone or with the control viruses.

Figure 1.

TESSA-E1-Rep enables rAAV replication

(A) Adenovirus MLP is modified to include a repressor-binding site (tetracycline operator, TetO), and the repressor (TetR) is encoded under MLP transcription. This creates a doxycycline-controllable negative feedback loop regulating the expression of the adenovirus structural genes. (B) rAAV genome replication in A549 cells. Cells were infected with rAAV2-EGFP (50 GC/cell) only or co-infected with the indicated viruses (10 TCID50/cell). rAAV genome replication determined by EGFP-qPCR.

TESSA-E1-Rep enables sensitive detection of single infection events by qPCR

As rAAV vectors do not induce CPE in cells, replication of the rAAV genome is required for sensitive detection of infection events using qPCR at the endpoint for vectors encoding non-reporter transgenes (e.g., EGFP). To assess the sensitivity of the qPCR-based method for the detection of single infection events, we initially carried out infectious titration of a rAAV2-EGFP vector using the “standard” TCID50 process in HEK293AD cells with TESSA-E1-Rep (MOI of 10 TCID50/cell). Each well of the 96-well plates was assessed by qPCR and EGFP expression by fluorescence microscopy at day 3 post-infection as endpoint detection of positive infection events. While each well was monitored for one or more EGFP-expressing cells as the determination of a positive infection event, qPCR analysis was performed by determining if each well was positive or negative by comparing the PCR threshold of the fluorescent signal of the test article against the assay’s negative control samples. As shown in Table 1, we observed a good correlation between positive infection events as determined by qPCR and EGFP detection. TCID50 infectious titer based on endpoint qPCR or EGFP expression was calculated by the Spearman-Kärber statistical method.17 Expectedly, we observed a slightly higher infectious titer based on qPCR detection, likely due to the higher sensitivity of the assay and, potentially, the detection of non-transcriptionally active or truncated rAAV genomes.

Table 1.

TCID50 infectious titration of rAAV2-EGFP using TESSA-E1-Rep

| Log dilution | Replicate 1 | Replicate 2 | Replicate 3 | Replicate 4 | Replicate 5 | Replicate 6 | Replicate 7 | Replicate 8 | Replicate 9 | Replicate 10 | Positive/total ratio (qPCR endpoint) | Positive/total ratio (EGFP endpoint) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −6 | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | 1 | 1 |

| −7 | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | 1 | 1 |

| −8 | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | 1 | 1 |

| −9 | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | 1 | 1 |

| −10 | qPCR+ EGFP− | qPCR+ EGFP− | negative | qPCR+ EGFP+ | negative | qPCR+ EGFP+ | qPCR+ EGFP+ | negative | qPCR+ EGFP− | negative | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| −11 | negative | qPCR+ EGFP− | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | 0.1 | 0 |

| −12 | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | 0 | 0 |

| −13 | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | negative | 0 | 0 |

| TCID50/mL | 1.58E+11 | 6.31E+10 | ||||||||||

Ten-fold serial dilution of a rAAV2-EGFP was used for co-infection with TESSA-E1-Rep in HEK293AD cells for infectious titration via the TCID50 method. Positive infection events were determined by qPCR (EGFP-specific) and EGFP expression via fluorescence microscopy. TCID50/mL titer calculated via Spearman-Kärber statistical method.17

TCID50 infectious titration of rAAV test articles using TESSA-E1-Rep

Using the TESSA-E1-Rep vector, we assessed the infectious titers of rAAV2-EGFP (GC/mL titer: 1.19E+13), rAAV6-EGFP (GC/mL titer: 5.50E+12), and rAAV8-EGFP (GC/mL titer: 4.30E+12) stocks in various cell lines against the TCID50 assay using HeLaRC32 cells (Table 2). Based on the standard TCID50 process, HeLaRC32 cells were co-infected with the rAAV test articles and the replicating Ad5 virus (Ad5-E1, MOI of 10 TCID50/cell); the various cell lines (HEK293AD, Huh7, and HepG2) were co-infected using the rAAV test articles with TESSA-E1-Rep (MOI of 10 TCID50/cell). In addition to HeLaRC32, the selected cell lines (HEK293AD, Huh7, and HepG2) are highly promiscuous to Ad5 infection.25,26,27,28 As expected, using a replicating Ad5 virus expressing the EGFP reporter, we observed 100% transduction of the target cells at an MOI of 10 TCID50/cell (Figure S1). For infectious rAAV titration via TCID50, endpoint detection via qPCR was carried out on day 3 post-infection. For rAAV2 and rAAV6, titration in the HeLaRC32 cells generated a 2–3-fold higher TCID50/mL titer compared to titration in HEK293AD cells using the TESSA-E1-Rep, while slightly higher or comparable titers were observed for the rAAV8 articles. In all the cell lines tested, we observed the general trend that rAAV2 is significantly more infectious in vitro compared to rAAV6 and rAAV8. While rAAV2-EGFP is highly infectious in HeLaRC32, HEK293AD, and HepG2 cells, exhibiting a P:I ratio of <100, we also observed an approximately 10-fold decrease in infectivity in Huh7 cells. As expected, rAAV8 exhibited a high P:I ratio (>2-8E+3) as it poorly transduces cells in vitro. Differences in AAV infectivity observed between various serotypes may be attributable to variations in capsid-glycan receptor interactions, which influence viral attachment and cellular entry.13,15

Table 2.

Comparison of rAAV TCID50 infectious titers in HeLaRC32 cells using Ad5-E1 against various cell lines using TESSA-E1-Rep

| rAAV serotype (test article) | Cell line | Helper | qPCR endpoint (TCID50/mL) | P:I ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rAAV2-EGFP | HeLaRC32 | Ad5-E1 | 5.01E+11 | 24 |

| rAAV2-EGFP | HEK293AD | TESSA-E1-Rep | 1.89E+11 | 63 |

| rAAV2-EGFP | Huh7 | TESSA-E1-Rep | 2.51E+10 | 474 |

| rAAV2-EGFP | HepG2 | TESSA-E1-Rep | 1.90E+11 | 63 |

| rAAV6-EGFP | HeLaRC32 | Ad5-E1 | 1.03E+10 | 536 |

| rAAV6-EGFP | HEK293AD | TESSA-E1-Rep | 3.76E+09 | 1460 |

| rAAV6-EGFP | Huh7 | TESSA-E1-Rep | 1.42E+09 | 3870 |

| rAAV6-EGFP | HepG2 | TESSA-E1-Rep | 1.89E+09 | 2920 |

| rAAV8-EGFP | HeLaRC32 | Ad5-E1 | 2.05E+09 | 2100 |

| rAAV8-EGFP | HEK293AD | TESSA-E1-Rep | 3.57E+09 | 1200 |

| rAAV8-EGFP | Huh7 | TESSA-E1-Rep | 8.16E+08 | 5270 |

| rAAV8-EGFP | HepG2 | TESSA-E1-Rep | 5.15E+08 | 8360 |

rAAV2-EGFP, rAAV6-EGFP, and rAAV8-EGFP test articles were titrated in HeLaRC32 cells using Ad5-E1 (MOI of 10 TCID50/cell) or in HEK293AD, Huh7, and HepG2 cells using TESSA-E1-Rep (MOI of 10 TCID50/cell). Positive infection events were determined by qPCR (EGFP-specific) and TCID50/mL titer calculated via Spearman-Kärber method.17 P:I (particle:infectivity) ratio was calculated by comparing TCID50 titer against genome particle titer determined by ddPCR.

Development and qualification of the TREAT assay

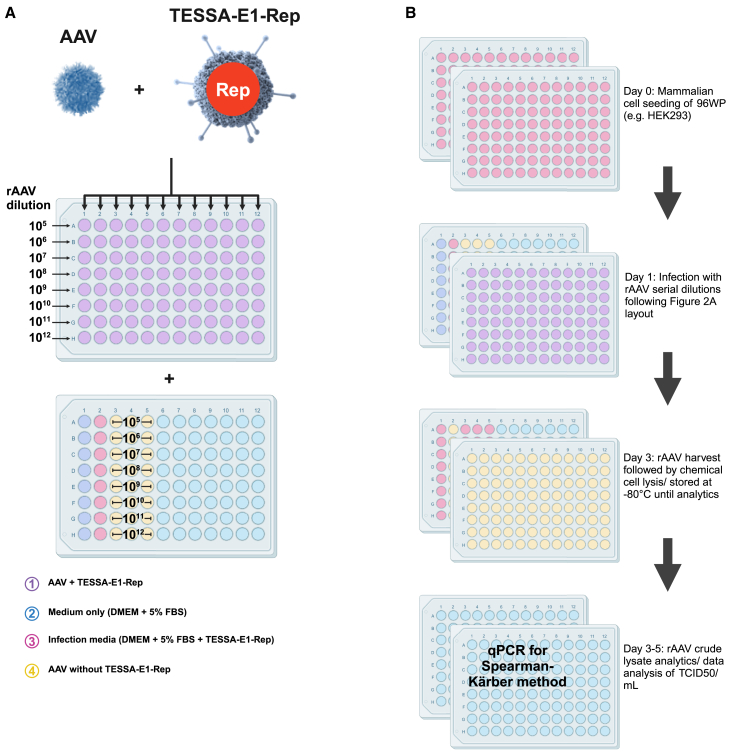

While the TESSA-E1-Rep vector enabled rAAV titration of HEK293 and non-HEK293-based cell lines using the standard TCID50 process, we further sought to develop and qualify the TREAT assay in HEK293AD cells for routine rAAV titration and rAAV GMP release. The assay qualification was designed to confirm that the assay method was suitable for use as a quantitative test for infectious titration of rAAV by TCID50 method in a two-part system: cell-based assay to amplify the rAAV genome in the presence of TESSA-E1-Rep, followed by TaqMan qPCR to detect the genome of interest (GOI) signal. Figures 2A and 2B provides the process flow diagram of the TREAT assay, qualified for rAAV infectious titration in HEK293AD cells. The assay is carried out across two 96-well plates (control plate and test article plate) for infectious titration of an rAAV test article (Figure 2A). Ten-fold serial dilutions of the rAAV test article are carried out with 12 replicates of each dilution used for co-infection with the TESSA-E1-Rep vector. HEK293AD cells in the control plate are also treated with the rAAV test article or TESSA-E1-Rep only, or left uninfected. Among all 10-fold serial dilutions, at least one dilution wherein all wells are positive, and at least one dilution wherein all wells are negative is required for the Spearman-Kärber method.17 At day 3, the plates are harvested, and each well is scored as positive or negative by comparing the Ct value of each test article well to the assay negative control wells and the corresponding test article dilution without TESSA-E1-Rep (Figure 2B). Wells with Ct values below the limit of detection (LOD) and the corresponding test article without TESSA-E1-Rep were scored positive. Ct values equal to or larger than the corresponding test article dilution without TESSA-E1-Rep were scored as negative and rAAV titers are reported as TCID50/mL.

Figure 2.

Overview and qualification of the TREAT assay for infection titration of rAAV via the TCID50 method

(A) Layout of the TREAT assay for rAAV titration with internal assay controls. (B) Protocol timeline from cell seeding to harvest and endpoint detection via endpoint qPCR.

To qualify the TREAT assay, we looked at the following parameters: specificity, linearity, precision, and accuracy. Acceptance criteria for evaluation of the qPCR and negative control of the TCID50 assay are provided in Table S1. Specificity was evaluated using controls that do not contain the rAAV-GOI sequence, including HEK293AD cells alone and cells treated with TESSA-E1-Rep alone. Two rAAV test articles (rAAV9-EGFP and rAAV9-GOI), diluted at 1E−5 and 1E−6, were used for the infection of HEK293AD cells at 12 replicate wells, and specificity was assessed by qPCR, using primers and probes directed against the EGFP and GOI sequences, respectively. Specificity criteria are met when control wells show no detection of GOI sequences by qPCR (<LOD). As shown in Table 3, the Ct values of the qPCR targeting EGFP and GOI were below LOD from all control replicate wells, while high signals (Ct values of 17–22) were detected from all samples infected with the rAAV9-EGFP and rAAV9-GOI. These results confirm the specificity of the endpoint qPCR assay against EGFP and the GOI.

Table 3.

Specificity evaluation of the TREAT assay

| Sample | Dilution factor | qPCR | Ct values qPCR | Ct of LOD | Detection rate | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293AD | N/A | EGFP | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | NA | 34.64 | 0/8 | |||

| N/A | GOI | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 38.15 | 0/8 | |||||

| TESSA-E1-Rep | N/A | EGFP | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 34.64 | 0/8 | ||||

| N/A | GOI | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 38.15 | 0/8 | |||||

| rAAV9-EGFP | 1.00E−05 | EGFP | 17.2 | 17.2 | 17.2 | 17.2 | 17.0 | 17.2 | 16.9 | 17.1 | 17.2 | 17.0 | 17.1 | 17.1 | 34.64 | 12/12 |

| 1.00E−06 | 20.3 | 21.3 | 20.9 | 20.1 | 20.8 | 20.6 | 20.4 | 20.2 | 20.1 | 20.4 | 20.8 | 20.7 | 12/12 | |||

| rAAV9-GOI | 1.00E−05 | GOI | 19.5 | 19.5 | 19.2 | 19.3 | 19.3 | 19.1 | 19.2 | 19.3 | 19.1 | 19.0 | 19.2 | 19.5 | 38.15 | 12/12 |

| 1.00E−06 | 22.5 | 22.2 | 22.1 | 22.5 | 22.1 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 22.0 | 22.0 | 22.3 | 22.4 | 23.0 | 12/12 | |||

Using a rAAV9-EGFP and rAAV9-GOI test article. Ct value 40.0 indicates that no signal was detected within 40 cycles of PCR.

Linearity is the ability of a method to produce test results that are directly proportional to the analyte concentration across a specified range.16,29 For linear fitting, the acceptance criterion is defined as R2 ≥0.9. To assess the linearity of rAAV detection via qPCR, using the TREAT assay, we co-infected HEK293AD cells with TESSA-E1-Rep (MOI of 10 TCID50/cell) and rAAV2-GOI at various 10-fold dilution ranges. Cells were harvested 72 hpi, and the copy number of rAAV2-GOI detected by GOI-specific qPCR was plotted in log scale (y axis) against the initial concentration of input rAAV2-GOI (x axis) for linear fitting. As shown in Table 4 and Figure 3, we observed a strong correlation between the DNA copy number of rAAV2-GOI at each dilution and the infection dose of rAAV2, with an R2 value of 0.9997. This exceeds the acceptance criterion, confirming the linearity of the TREAT method. Additionally, we observed an average of 20,000-fold amplification of the rAAV2-GOI over an input range of 1.77E+5 to 1.77E+1 viral genomes/well (VG/well). This confirmed that the rAAV2 genome from a single infection event can be amplified up to 20,000-fold. Moreover, sampling of 0.25% of the total lysate per well (as described in materials and methods) as input for the qPCR assay corresponds to 50 copies per reaction, significantly above the detection limit of the qPCR detection threshold. Lastly, to determine the intermediate precision (inter-assay variability) of the TREAT assay, six runs of the test method were performed using a rAAV9-EGFP test article by two operators (five times by operator 1, and once by operator 2) (Table 5). As a criterion for acceptance of precision, titers of the six independent precision runs must be within ±0.5 log of the average titer. Titration of the rAAV9-EGFP test article yielded an average titer of 1.31E+9 TCID50/mL with good precision between the different runs and <±0.35 logTCID50 deviation from the average logTCID50 titer. Additionally, as confirmation of the reproducibility of the TREAT assay, further titration of two test articles rAAV9-GOIA and rAAV9-GOIB via six replicate runs from two operators also showed an average of logTCID50 deviation of −0.07 and −0.05, respectively, compared to the average logTCID50 (Table S2). Our results confirmed that the TREAT assay demonstrated good intermediate precision and reproducibility for determining rAAV infectious titers.

Table 4.

Linearity evaluation of the TREAT assay

| Sample | Dilution factor | rAAV (VG/well) | Log of VG | Ct value (n = 12) | Positive wells | Detected DNA copy number (copies/well) | Log of copy number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rAAV2-GOI | 1.00E+07 | 1.77E+05 | 5.2 | 15.2 | 12/12 | 2.81E+09 | 9.5 |

| 1.00E+08 | 1.77E+04 | 4.2 | 18.2 | 12/12 | 3.49E+08 | 8.5 | |

| 1.00E+09 | 1.77E+03 | 3.2 | 21.6 | 12/12 | 3.31E+07 | 7.5 | |

| 1.00E+10 | 1.77E+02 | 2.2 | 24.6 | 12/12 | 5.39E+06 | 6.7 | |

| 1.00E+11 | 1.77E+01 | 1.2 | 30.2 | 4/12 | 6.05E+05 | 5.8 | |

| 1.00E+12 | 1.77E+00 | 0.2 | >39.00 | 0/12 | N/A | NA | |

| 1.00E+13 | 1.77E−01 | −0.8 | >39.00 | 0/12 | N/A | NA | |

| 1.00E+14 | 1.77E−02 | −1.8 | >39.00 | 0/12 | N/A | NA |

Detected DNA copy number at each dilution of rAAV2-GOI used for TREAT assay and obtained via qPCR (co-infected HEK293AD cells with TESSA-E1-Rep at MOI of 10 TCID50/cell).

Figure 3.

Linearity of the TREAT assay

The log of detected DNA copy number at each dilution was plotted against the concentration of the rAAV for linear fitting, with an R2 value of 0.9997.

Table 5.

Intermediate precision assessment of the TREAT assay

| Sample | Operator | Test | TCID50/mL | Log TCID50 | Average TCID50/mL | Average logTCID50 | Δ logTCID50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rAAV9-EGFP | Operator 1 | 1 | 2.61E+09 | 9.42 | 1.31E+09 | 9.07 | 0.35 |

| 2 | 1.47E+09 | 9.17 | 0.10 | ||||

| 3 | 5.62E+08 | 8.75 | −0.32 | ||||

| 4 | 1.21E+09 | 9.08 | 0.01 | ||||

| 5 | 8.25E+08 | 8.92 | −0.15 | ||||

| Operator 2 | 6 | 1.21E+09 | 9.08 | 0.01 |

Six runs of the test method were performed by two operators of an rAAV-EGFP test article. Δ logTCID50 determined by deviation of each logTCID50 relative to the average titer.

Discussion

Precise and robust methods to characterize and quantify rAAV vectors are important for process development and ensuring consistent, efficacious, and safe gene therapy products. In the current study, we introduced the TREAT assay, which builds upon the previously established TESSA platform, to address the limitations of traditional rAAV infectious titration methods.

As opposed to the infectious quantification of plaque-forming viruses and viral vectors, such as adenovirus and herpes viruses, infectious titration of rAAV is complicated by its inability to form CPE in infected cells and requiring a helper virus to aid in viral replication. Furthermore, rAAV quantification by functional or potency titer has inherent drawbacks and can be limited by cost, sensitivity, complexity, and assay availability to quantify gene expression and/or protein activity. These challenges have previously led to the development of a few assays for infectious titration of rAAV vectors. The infectious center assay (ICA) requires serial dilution of the rAAV and co-infection with WT Ad5, and transfer of the cells to nylon membranes for hybridization with a gene-specific probe for quantification of the number of cells capable of initiating infection, rather than just measuring viral particles.2,11,15 Using a similar approach, the replication center assay (RCA) was adapted to include co-infection with both WT AAV and WT Ad5 to induce DNA amplification of the rAAV and improve detection sensitivity by the hybridized probe.11 However, both of these methods are labor and time-consuming, and suffer from issues of reproducibility, either due to the lack of sensitivity for detecting positive rAAV infection events in the ICA method, or the complex interplay between WT Ad and WT AAV and requirements to balance these two virus helpers in the RCA method. Mohiuddin et al. developed an rAAV infectious titration assay using the herpes simplex virus (HSVr/c) vector expressing AAV2 rep and cap genes to determine the infectivity of various rAAV serotypes.11 However, this HSV ICA method requires a double screening process to identify candidate cell lines effectively transduced by the HSV and rAAV. Interestingly, using rAAV1 and rAAV2, the authors also showed that the titers determined in a HeLa-based cell line (C12) with the HSVr/c were 3–4 logs lower compared to titers obtained using an Ad helper, while titration of the same rAAV in HEK293 cells using HSVr/c showed a 2–10-fold lower in potency compared to the Ad helper. It was suggested that the inefficiency may be due to poor HSV infection or overexpression of Rep from the HSVr/c vector.11

The rAAV TCID50 infectious titration assay initially developed by Clark and colleagues based on the use of HeLa rep/cap trans-complementing cell line and WT Ad5 remains the most common method for measuring rAAV infectivity.18 Optimization of the rAAV TCID50 infectious assay was subsequently reported for improved assay sensitivity and detection of single infection events via endpoint qPCR.17 More recently, the rAAV TCID50 assay was further adapted for endpoint detection using ddPCR to improve interassay precision and eliminate the need to generate a standard curve required in the qPCR method.16 While the transition to ddPCR detection resulted in a significant reduction in variability between rAAV infectious titer measurements and improved assay precision, the traditional rAAV TCID50 assay remains limited to the use of specialized HeLa rep/cap complementation cell lines. This poses particular challenges for titration of various rAAV serotypes or novel capsids that are poorly permissive to these HeLa cell lines. Moreover, recent bioethical and legal concerns have been raised relating to the research and commercial use of HeLa and HeLa-based cell lines which may limit their adaptability and use in particular testing and research laboratories.30

We developed the TREAT assay to address many of the challenges associated with the traditional rAAV TCID50 method, including high variability and limited sensitivity, but also the potential to measure infectivity rAAVs in various cell targets to provide a more informative understanding of rAAV tropism for any particular capsid of interest. By leveraging the TESSA-E1-Rep vector, which encodes AAV Rep and Ad5 E1 genes, the TREAT assay enables rAAV genome replication in both HEK293 and non-HEK293 cell lines, and we observed over 20,000-fold amplification of input rAAV2 in HEK293AD cells via qPCR. Furthermore, using rAAV2, 6, and 8, we demonstrated the robustness of the TESSA-E1-Rep vector in measuring rAAV infectivity across different cell lines. Consistent with previous reports, rAAV2 showed the highest infectivity in vitro, while rAAV6 was significantly more infectious compared to rAAV8 across the various cell lines.31

Qualification of the TREAT assay in HEK293AD cells yielded intermediate precision with titers across six independent runs falling within ±0.5 log of the average titer. Our results showed consistent outcomes across multiple operators and rAAV test articles. Overall, the results of our qualification assessment from evaluating specificity, linearity, and precision support the use of the TREAT assay for reliable infectious titration of rAAV in-process materials and gene therapy products in HEK293AD cells.

While the TREAT assay requires the target cell to be permissive to adenovirus infection, it overcomes the limitation of requiring rep/cap complementation or E1-expressing (e.g., HEK293) cell lines. The assay addresses logistical and safety concerns associated with the traditional rAAV TCID50 method. The TREAT assay can be more accessible to research laboratories as it does not require specialized cell lines, rather HEK293 cells commonly used in the rAAV production process, or other cell lines that are readily available and of interest to the researcher(s). As the TREAT assay also uses a self-silencing TESSA vector, rather than WT Ad5, production of infectious adenoviruses is inhibited during the rAAV titration process. Additionally, as the TESSA-E1-Rep vector does not express AAV Cap, its use in the TREAT assay further improves safety by eliminating the generation of replication-competent AAVs and its potential for cross-contamination of general cell cultures.32

Lastly, our process for qualifying the use of the TREAT assay in HEK293AD cells enables routine testing of rAAV to support gene therapy development. Future studies may explore adapting the TREAT assay with endpoint detection of infection events via ddPCR to further improve assay precision, explore the use of the TREAT assay in additional cell types and evaluate its ability to predict in vivo infectivity.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HEK293AD cells (293AD; Cell Biolabs, CA, USA), HeLaRC32 and A549 [both from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection), VA, USA], were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, MA, USA), while HeLa and HepG2 (both from ATCC) were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM; ATCC) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS. All cell lines were maintained at 5% CO2, 37°C, and 95% humidity.

Viral vectors

Construction of the TESSA-Rep genome plasmid (pSU1091) has been described previously.21 For insertion of the Ad5 E1 genes into the TESSA-Rep genome plasmid (pSU1091), the Ad5 E1 coding sequence was extracted from the TESSA-E1 plasmid pSU708 with PacI and inserted into pSU1091 linearized using AsiSI to generate TESSA-E1-Rep (pSU1270).22 Positive clones were isolated and screened by test restriction digest and Sanger sequencing. All adenoviral vectors were recovered and purified from HEK293AD cells, and the infectious titer was quantified as described previously.22 Recombinant AAV2-EGFP, rAAV6-EGFP, and rAAV8-EGFP vectors used in this study were generated by the TESSA Duo process as previously described.21 Other rAAV viral vector stocks (specifically, rAAV9-EGFP, rAAV9-GOI, rAAV9-GOIA, rAAV9-GOIB, and rAAV2-GOI) used in this study were produced by WuXi AppTec ATU Co. (PA, USA), using the plasmid triple-transfection process in suspension HEK293 cells and purified by two-step process of AAVX affinity chromatography (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and ion-exchange chromatography.23 All rAAV vectors were quantified by ddPCR to determine the titer of genome particles.

rAAV genome replication assay

To determine rAAV genome replication, A549 cells were seeded in 48-well plate tissue culture plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well for 24 h at 5% CO2, 37°C, and 95% humidity in 300 μL of DMEM containing 10% FBS. Cells were infected with rAAV2-EGFP (50 GC/cell) only or co-infected with TESSA-E1-Rep, TESSA-E1, TESSA-Rep, Ad5-E1 (10 TCID50/cell). Total DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and rAAV genome replication was determined by EGFP-qPCR as previously described.21

Infectious titration of rAAV using the standard TCID50 assay

To determine the infectivity of rAAV preparations, mammalian cells (HeLaRC32, HEK293AD, HepG2, and Huh7) were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well for 24 h at 5% CO2, 37°C, and 95% humidity in 100 μL DMEM (or EMEM, as specified in the cell culture section) containing 10% FBS. One 96-well plate would correspond to the titration of one rAAV test material. For each rAAV test material, eight 10-fold serial dilutions (e.g., 1 × 10−6 to 1 × 10−13) were made using DMEM containing 2% FBS and supplemented with TESSA-E1-Rep or Ad5-E1 (for HelaRC32 cells) at an MOI of 10 TCID50/cell. Ten replicates of each sample dilution were added at 100 μL per well on each plate. For each plate, 12 negative control wells were infected with the infection media only (adenovirus only). Plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity before lysis by the addition of 10× chemical lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 20 mM MgCl2, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, pH 7.5) supplemented with proteinase K (1:100 dilution; QIAGEN). After the 10× lysis buffer is added, plates were incubated in a static incubator for 2 h at 37°C. Samples were then diluted 1 in 50 with nuclease-free water (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 5 μL were used in qPCR reactions using TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) in a StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences targeting the EGFP are forward 5′-GAACCGCATCGAGCTGAA-3′, reverse 5′-TGCTTGTCGGCCATGATATAG-3′, and TaqMan probe 5′-ATCGACTTCAAGGAGGACGGCAAC-3′. PCR cycles were as follows: 95°C 10 min; 40 times (95°C 1 s, 60°C 20 s). A well is scored as positive if the Ct value is above the average Ct value (3 SD) of the negative control wells (adenovirus only). Infectious rAAV titer was determined as TCID50 per mL using the Spearman-Kärber statistical method.17

rAAV infectious titer assay (TCID50) using the TREAT method

For the TREAT method, two 96-well plates are required per rAAV test article (control plate and test article plate). Each 96-well plates was seeded with HEK293AD at 2 × 104 cells per well in 100 μL of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 18–24 h. The following day, 6 assigned wells from the control plate were used for cell counting to determine the average viable cell number per well. In the control plate, cell media was removed from all wells and was replaced with 100 μL of either (1) DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS alone (dilution media); (2) dilution media containing TESSA-E1-Rep at MOI 10 TCID50/cell (infectious media); or (3) infectious media containing the rAAV test article. For each rAAV test article, eight 10-fold serial dilutions (e.g., 1 × 10−7 to 1 × 10−14) were made using the infectious media (DMEM, 5% FBS, TESSA-E1-Rep MOI of 10 TCID50/cell). Twelve replicates of each sample dilution were added at 100 μL per well on each test article plate. Control and test article plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 72 ± 4 h. For the assay to be valid, HEK293AD cells in the test article plate must show CPE at 72 h post-infection upon microscopy observation. Cells in the control and test article plates were lysed by the addition of 100 μL/well of 2× lysis buffer (0.8 M NaOH, 10mM EDTA, pH 8.0 in nuclease-free water), followed by incubation at 65°C for 60 ± 5 min. Plates were left to cool at room temperature for 30–60 min. Samples were diluted 10-fold with the infectious titration diluent composed of 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 1 M HCl at 49:1 (v/v) ratio. Five microliters of the 10-fold diluted cell lysates were used in the qPCR reaction (25 μL reaction volume) with either EGFP or GOI-specific primers and probe. Standard curves for qPCR analyses were generated using circular plasmids containing the GOI(s) through linearization by restriction digest and purification by gel electrophoresis. A 7-point standard curve was prepared by serial dilution of plasmid standard in PCR dilution buffer (10 mL of GeneAmp 10X PCR Buffer, 20 μL of sheared 10 mg/mL Salmon Sperm DNA, 1 mL 10% Pluronic F-68 and nuclease-free water up to 100 mL). qPCR run parameters consisted of 10 min at 95°C, and then 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, followed by 60°C for 60 s. Analysis was performed by comparing the Ct value of each test article well to the assay negative control samples (without TESSA-E1-Rep) corresponding to each dilution. qPCR LOD is determined by the lowest concentration of the standard curve (approximately 10 copies/reaction) and wherein at least two replicates out of three have Ct values. Signals above the negative control (3 SD) is scored positive, and the infectious rAAV titer was determined to be TCID50 per mL using the Spearman-Kärber statistical method.17

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article and its supplemental information file.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Matthew Tridgett for helping with graphical representations. The work described was fully funded by OXGENE, A WuXi Advanced Therapies Company, and all listed authors contributed to the work as employees of OXGENE and/or WuXi Advanced Therapies.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, W.S., R.C., and W.V.; formal analysis, C.F., X.L., Z.C., and W.S.; funding acquisition, R.C. and W.V.; investigation, C.F., X.L., Z.C., and W.S.; methodology, C.F., X.L., Z.C., and W.S.; supervision, R.C., W.V., M.I.P., and W.S.; writing – original draft, C.F., M.I.P., and W.S.; writing – review & editing, M.I.P. and W.S.

Declaration of interests

All listed authors are present or past employees of OXGENE, A WuXi Advanced Therapies Company. OXGENE has filed a patent application related to this work.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2025.101492.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Wang J.H., Gessler D.J., Zhan W., Gallagher T.L., Gao G. Adeno-associated virus as a delivery vector for gene therapy of human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024;9:78. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01780-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kontogiannis T., Braybrook J., McElroy C., Foy C., Whale A.S., Quaglia M., Smales C.M. Characterization of AAV vectors: A review of analytical techniques and critical quality attributes. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2024;32 doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2024.101309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gimpel A.L., Katsikis G., Sha S., Maloney A.J., Hong M.S., Nguyen T.N.T., Wolfrum J., Springs S.L., Sinskey A.J., Manalis S.R., et al. Analytical methods for process and product characterization of recombinant adeno-associated virus-based gene therapies. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2021;20:740–754. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blay E., Hardyman E., Morovic W. PCR-based analytics of gene therapies using adeno-associated virus vectors: Considerations for cGMP method development. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2023;31 doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2023.101132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan J.S., Chen K., Si Y., Kim T., Zhou Z., Kim S., Zhou L., Liu X.M. Process improvement of adeno-associated virus (AAV) production. Front. Chem. Eng. 2022;4 doi: 10.3389/fceng.2022.830421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu H., Zhang Y., Yip M., Ren L., Liang J., Chen X., Liu N., Du A., Wang J., Chang H., et al. Producing high-quantity and high-quality recombinant adeno-associated virus by low-cis triple transfection. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2024;32 doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2024.101230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendes J.P., Fernandes B., Pineda E., Kudugunti S., Bransby M., Gantier R., Peixoto C., Alves P.M., Roldão A., Silva R.J.S. AAV process intensification by perfusion bioreaction and integrated clarification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue W., Fulco C., Sha S., Alden N., Panteli J., Hossler P., Warren J. Adeno-associated virus perfusion enhanced expression: A commercially scalable, high titer, high quality producer cell line process. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2024;32 doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2024.101266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen T.N.T., Sha S., Hong M.S., Maloney A.J., Barone P.W., Neufeld C., Wolfrum J., Springs S.L., Sinskey A.J., Braatz R.D. Mechanistic model for production of recombinant adeno-associated virus via triple transfection of HEK293 cells. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2021;21:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogdanovic A., Donohue N., Glennon B., McDonnell S., Whelan J. Towards a Platform Chromatography Purification Process for Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Biotechnol. J. 2025;20 doi: 10.1002/biot.202400526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohiuddin I., Loiler S., Zolotukhin I., Byrne B., Flotte T., Snyder R. Herpesvirus-based infectious tittering of recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Mol. Ther. 2005;11:2. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daya S., Berns K.I. Gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vectors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008;21:583–593. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhungel B.P., Bailey C.G., Rasko J.E.J. Journey to the Center of the Cell: Tracing the Path of AAV Transduction. Trends Mol. Med. 2021;27:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeltner N., Kohlbrenner E., Clément N., Weber T., Linden R.M. Near-perfect infectivity of wild-type AAV as benchmark for infectivity of recombinant AAV vectors. Gene Ther. 2010;17:872–879. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.François A., Bouzelha M., Lecomte E., Broucque F., Penaud-Budloo M., Adjali O., Moullier P., Blouin V., Ayuso E. Accurate Titration of Infectious AAV Particles Requires Measurement of Biologically Active Vector Genomes and Suitable Controls. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018;27:223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duong T., McAllister J., Eldahan K., Wang J., Onishi E., Shen K., Schrock R., Gu B., Wang P. Improvement of precision in recombinant adeno-associated virus infectious titer assay with droplet digital PCR as an endpoint measurement. Hum. Gene Ther. 2023;34:742–757. doi: 10.1089/hum.2023.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zen Z., Espinoza Y., Bleu T., Sommer J.M., Wright J.F. Infectious titer assay for adeno-associated virus vectors with sensitivity sufficient to detect single infectious events. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004;15:709–715. doi: 10.1089/1043034041361262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark K.R., Voulgaropoulou F., Johnson P.R. A stable cell line carrying adenovirus-inducible rep and cap genes allows for infectivity titration of adeno-associated virus vectors. Gene Ther. 1996;3:1124–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lock M., Wilson J., Sena-Esteves M., Gao G. Sensitive Determination of Infectious Titer of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Viruses (rAAVs) Using TCID50 End-Point Dilution and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2020;1 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot095653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayuso E., Blouin V., Lock M., McGorray S., Leon X., Alvira M.R., Auricchio A., Bucher S., Chtarto A., Clark K.R., et al. Manufacturing and characterization of a recombinant adeno-associated virus type 8 reference standard material. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014;25:977–987. doi: 10.1089/hum.2014.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su W., Patrício M.I., Duffy M., Krakowiak J., Seymour L., Cawood R. Self-attenuated adenovirus enables production of recombinant adeno-associated virus for high manufacturing yield without contamination. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1182. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28738-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su W., Seymour L.W., Cawood R. AAV production in stable packaging cells requires expression of adenovirus 22/33K protein to allow episomal amplification of integrated rep/cap genes. Sci. Rep. 2023;13 doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-48901-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roach M.K., Wirz P., Rouse J., Schorzman A., Beard C.W., Scott D. Production of recombinant adeno-associated virus 5 using a novel self-attenuating adenovirus production platform. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2024;32 doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2024.101320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartweger H., Gautam R., Nishimura Y., Schmidt F., Yao K.H., Escolano A., Jankovic M., Martin M.A., Nussenzweig M.C. Gene Editing of Primary Rhesus Macaque B Cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2023;10:192. doi: 10.3791/64858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jogler C., Hoffmann D., Theegarten D., Grunwald T., Uberla K., Wildner O. Replication properties of human adenovirus in vivo and in cultures of primary cells from different animal species. J. Virol. 2006;80:3549–3558. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3549-3558.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao T., Rao X.M., Xie X., Li L., Thompson T.C., McMasters K.M., Zhou H.S. Adenovirus with insertion-mutated E1A selectively propagates in liver cancer cells and destroys tumors in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3073–3078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Recchia A., Parks R.J., Lamartina S., Toniatti C., Pieroni L., Palombo F., Ciliberto G., Graham F.L., Cortese R., La Monica N., Colloca S. Site-specific integration mediated by a hybrid adenovirus/adeno-associated virus vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2615–2620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamel W., Segerman B., Öberg D., Punga T., Akusjärvi G. The adenovirus VA RNA-derived miRNAs are not essential for lytic virus growth in tissue culture cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4802–4812. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarner P., Lau S.K., Chowdhury T., Guilmette E., Trapa P., Lo S.C., Shen S. Development of a one-step RT-ddPCR method to determine the expression and potency of AAV vectors. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2021;23:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beskow L.M. Lessons from HeLa Cells: The Ethics and Policy of Biospecimens. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2016;17:395–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-083115-022536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis B.L., Hirsch M.L., Barker J.C., Connelly J.P., Steininger R.J., 3rd, Porteus M.H. A survey of ex vivo/in vitro transduction efficiency of mammalian primary cells and cell lines with Nine natural adeno-associated virus (AAV1-9) and one engineered adeno-associated virus serotype. Virol. J. 2013;10:74. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen J.M., Debelak D.J., Reynolds T.C., Miller A.D. Identification and elimination of replication-competent adeno-associated virus (AAV) that can arise by nonhomologous recombination during AAV vector production. J. Virol. 1997;71:6816–6822. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6816-6822.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article and its supplemental information file.