Abstract

Several neural mechanisms underlying resilience to Alzheimer's disease (AD) have been proposed, including redundant neural connections between the posterior hippocampi and all other brain regions, and global functional connectivity of the left frontal cortex (LFC). Here, we investigated if functional redundancy of the hippocampus (HC) and LFC underscores neural resilience in the presence of early AD pathologies. From the ADNI database, cognitively normal older adults (CN) (N = 220; 36 % Aβ+) and patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) (N = 143; 51 % Aβ+) were utilized. Functional redundancy was calculated from resting state fMRI data using a graph theoretical approach by summing the direct and indirect paths (path lengths = 1–4) between each region of interest and its 263 functional connections. Posterior HC, but not anterior HC or LFC, redundancy was significantly lower in Aβ+ than Aβ-groups, regardless of diagnosis. Posterior HC redundancy related to higher education and better episodic memory, but it did not moderate the Aβ-cognition relationships across the diagnostic groups. Together, these findings suggest that posterior HC redundancy captures network disruption that parallels selective vulnerability to Aβ deposition. Further, our findings indicate that functional redundancy may underscore a network metric different from global functional connectivity of the LFC.

Keywords: Graph theory, Resilience, Beta-amyloid plaques, Alzheimer's disease, Aging, Functional magnetic resonance imaging

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the leading cause of dementia, is pathologically characterized by β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, accompanied by progressive cognitive decline (Braak and Braak, 1991). Neuropathological and in vivo neuroimaging evidence has demonstrated that around 30 % of clinically normal older adults exhibit significant loads of AD neuropathology in the brain (Jagust, 2013; Neuropathology Group. et al., 2001; Price and Morris, 1999), representing a stage now called preclinical AD (Sperling et al., 2013). Several neural changes have been associated with preclinical AD, including reduced functional connectivity, especially in the default mode network, gray matter atrophy, and disrupted white matter integrity (Hedden et al., 2009; Mormino et al., 2011; Oh et al., 2014a; Rieckmann et al., 2016). Despite these adverse neural changes, individuals with preclinical AD remain clinically intact. Such findings of a disconnection between neuropathology and clinical status led to the hypotheses collectively considered as reserve and resilience (Arenaza-Urquijo and Vemuri, 2018; Katzman et al., 1988; Stern, 2002). Reserve and resilience hypotheses postulate that certain neural mechanisms, which are potentially multiple yet complementary, exist to enhance an individual's ability to cope with pathology (Katzman et al., 1988; Stern, 2002). The neural mechanisms supposedly underlying reserve and resilience are further thought to be shaped by enriching experiences accumulated across the lifespan, such as higher education, literacy, physical exercise and social engagement (Stern, 2002). Given that no effective treatment for AD is readily available, prevention and early intervention efforts targeting neuroprotective or resilience mechanisms have been emphasized to delay or prevent a large proportion of dementia cases (Livingston et al., 2020).

Several neural mechanisms underlying resilience have been proposed including increased neural activity measured by positron emission tomography (e.g., [18F] Fluorodeoxyglucose PET), regional cerebral blood flow, or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) during tasks. The increased neural activity, commonly construed as neural compensation, has been observed in the frontoparietal cortex accompanied by temporoparietal hypometabolism in AD (Stern et al., 1992) while temporoparietal hypermetabolism has been observed in the presence of brain Aβ pathology among clinically intact older adults (Benzinger et al., 2013; Oh et al., 2014b, 2016; Ossenkoppele et al., 2014). Such increased neural activity has been accompanied by either better memory performance or non-demented cognitive status (Oh et al., 2018). Based on these observations, it was hypothesized that the brain regions exhibiting increased neural activity may compensate for the disrupted functions of other regions that are more susceptible to AD-related pathologies, such as the temporoparietal cortices, and their connected brain regions, such as the hippocampus.

More recently, network-based mechanisms, captured using resting state fMRI, have also been proposed to underlie resilience in brain aging, including global functional connectivity of the left frontal cortex (LFC) (Franzmeier et al., 2017; Cole et al., 2013) and functional redundancy of the posterior hippocampus (HC) (Cole et al., 2012). Functional connectivity assesses the degree of association, traditionally via point-to-point bivariate correlation techniques, between time series of activity of two brain regions. Higher functional connectivity is thought to represent the stronger direct communication between the two brain regions. In the LFC, global connectivity patterns, which represent averaged connection strength between LFC and the rest of the brain, are posited to underly cognitive resilience, as global LFC connectivity is related to proxies of cognitive resilience (e.g., IQ, educational attainment) (Cole et al., 2012; Franzmeier et al., 2017), and the LFC can adapt its global connectivity patterns to flexibly recruit various networks to meet current task-demands (Cole et al., 2013). In addition, the global LFC connectivity is shown to mitigate the slope of memory decline in MCI patients and delay cognitive impairment in autosomal dominant and sporadic AD. (Franzmeier et al., 2017, 2018)

Complementary to measures of functional connectivity, functional redundancy is a graph theory-based measure that captures how much redundant wiring exists between regions in addition to the shortest point-to-point connections. Thus, functional redundancy characterizes connectivity profiles through a different lens than bivariate correlation strength measures, by examining both direct and indirect pathways (Di Lanzo et al., 2012). Redundancy is a common design principle utilized in engineering to improve system reliability (Billinton and Allan, 1992), where duplicate pathways are built into a system to serve as a potential fail-safe mechanism in the event that a single mechanism is damaged and rendered non-functional (Billinton and Allan, 1992). Redundancy architecture is observed in biological systems, including the brain (Di Lanzo et al., 2012; Cui et al., 2024; Ghanbari et al., 2023; Langella et al., 2021a, 2021b; Sadiq et al., 2021; Stanford et al., 2024), and, in the context of AD, it is hypothesized that existing alternative functional connections between two regions or networks may allow functional persistence when the primary pathway connecting such regions is damaged by pathology (Di Lanzo et al., 2012; Langella et al., 2021b). Recent work demonstrated that in older adults across the AD clinical continuum (e.g., cognitively normal (CN), Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), AD), higher redundancy in specific brain regions, such as the left and right posterior hippocampus (HC) (Langella et al., 2021b), or across the whole brain network (Ghanbari et al., 2023), are associated with better cognitive performance (Langella et al., 2021b). Although these studies suggest the potential role of redundancy in resilience, underlying AD pathologies, such as amyloid plaques, a hallmark feature of AD, were not considered in past work. Thus, it remains unknown, whether functional redundancy serves in a resilience manner, maintaining normal cognition in the presence of AD pathology, or rather, is affected by AD pathology and thereby simply reflects healthier brain aging status and resulting better cognitive functioning. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether the neuroprotective effects of the LFC in past work would have been mediated by functional redundancy.

To examine if functional redundancy serves as a novel neural correlate of resilience in the presence of AD pathologies, we used resting state fMRI data from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database. Functional redundancy was estimated using a graph theoretical approach in CN and MCI groups characterized by Aβ positivity status. We focused on five a priori selected regions of interest, including left and right anterior HC, left and right posterior HC, and LFC, because these regions are known to be affected in the early stages of AD pathophysiology and their network-based metrics have been previously tested with respect to cognitive performance along the AD continuum (Franzmeier et al., 2018; Langella et al., 2021b). The main hypothesis was that redundancy levels would be higher in Aβ+ than Aβ-groups, if functional redundancy plays a role in resilience in the earliest stages of AD pathologies. Alternatively, we hypothesized that higher functional redundancy would be observed in Aβ-than Aβ+ groups, regardless of diagnosis, if functional redundancy reflects non-pathological brain aging status. Additionally, we explored whether posterior HC, but not anterior HC or LFC, redundancy would be lower in MCI than CN (Franzmeier et al., 2018; Langella et al., 2021b), and whether Aβ positivity status and diagnosis would interact to impact redundancy. Finally, to assess the potential role of functional redundancy as a resilience mechanism, we examined the relationships of functional redundancy with education and cognitive performance and examined whether functional redundancy mitigates the potential negative relationship between Aβ pathology and cognition.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

The data utilized for analysis were obtained from the ADNI database. Launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, ADNI is led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. A goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. For more information, see www.adni-info.org. As per ADNI protocols, all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. ADNI obtained all IRB approvals and met all ethical standards in the collection of data. Further details can be found at adni.loni.usc.edu. As the present study was based on the secondary analysis with deidentified data, additional ethical approval from Brown University IRB was not required.

A total of 370 CN and MCI participants were selected for analysis from the ADNI database based on the availability of both resting state fMRI and Florbetapir (AV45) PET. The inclusion criteria for each diagnostic group were determined by ADNI. CN participants presented with no memory complaints, had MMSE performance between 24 and 30, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) performance of 0, and did not meet diagnostic criteria for MCI or AD. MCI participants presented with a subjective memory concern, MMSE performance between 24 and 30, CDR score of 0.5, preserved functioning, and did not meet criteria for diagnosis of AD.

Participants selected for analysis underwent AV45 PET on average within one year of the resting state fMRI session. Aβ-status was determined using a threshold of 1.11 Standardized Uptake Value Ratios (SUVR) (normalized to the cerebellum), which is recommended by ADNI for cross-sectional studies (Jones et al., 2016). Individuals above the Aβ criterion were deemed Aβ-positive (Aβ+) while those below were deemed Aβ-negative (Aβ-). Seven participants were missing APOE4 genotype information and thus were excluded from analysis, resulting in a total sample of 363 individuals. See Table 1 for sample demographics.

Table 1.

Values presented as M ± SD unless otherwise specified. MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam; EF = executive function; FD = framewise displacement.

| CN Aβ- | CN Aβ+ | MCI Aβ- | MCI Aβ+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 140 | 80 | 70 | 73 |

| Age Range | 55.8–91.3 | 61.1–91.5 | 59.7–91.6 | 56.7–93.2 |

| Agea | 72.91 (6.94) | 75.77 (6.92) | 75.49 (7.99) | 74.54 (7.70) |

| Sex (% female) | 55.00 | 56.25 | 42.86 | 47.95 |

| Education (years) | 16.73 (2.33) | 16.52 (2.59) | 16.17 (3.08) | 16.10 (2.55) |

| APOE4 (% carriers)c | 20.71 | 47.50 | 17.14 | 61.64 |

| MMSEa,b,c | 29.11 (1.11) | 28.78 (1.43) | 28.37 (1.69) | 27.33 (2.04) |

| Memory (composite)a,b,c | 1.05 (0.62) | 0.94 (0.62) | 0.60 (0.67) | 0.10 (0.63) |

| EF (composite)b | 1.11 (0.77) | 0.94 (0.79) | 0.42 (0.81) | 0.29 (0.95) |

| FD | 0.18 (0.09) | 0.20 (0.20) | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.20 (0.11) |

Significant interaction effect between diagnosis and Aβ status, p's < 0.05.

Significant main effect of diagnosis, p's < 0.05.

Significant main effect of Aβ-status, p's < 0.05.

2.2. Data acquisition and preprocessing

Resting state fMRI data from ADNI phases 2 and 3 (basic sequence) were used in the current analysis. The MR acquisition protocols employed across phases were common to all sites and adapted for each scanner (volumes = 140–200, TR = 3000ms, TE = 30ms, flip angle = 80–90°, slice thickness = 3.3–3.4 mm). Time series were not truncated to match number of volumes across datasets, following previous studies (Williamson et al., 2024; Lei et al., 2022).

Resting state fMRI data were preprocessed using fMRIPrep 20.2.6 (Esteban et al., 2019), which is based on Nipype 1.7.0 (Ghanbari et al., 2023, Gorgolewski et al., 2011)(. The functional data were slice-time corrected (3dTshift; AFNI v16.2.07) (Cox and Hyde, 1997), motion corrected (mcflirt FSL v5.0.9) (Jenkinson et al., 2002), and co-registered to the anatomical T1-weighted scan using boundary based registration with six degrees of freedom (bbregister; Freesurfer v6.0.1) (Dale et al., 1999; Greve and Fischl, 2009). Several confounding time-series were calculated based on the preprocessed fMRI blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signals: framewise displacement (FD) (Power et al., 2014) and anatomical component-based regressors computed separately for CSF and WM (aCompCor) (Behzadi et al., 2007). Volumes that exceeded a threshold of 0.5 mm framewise displacement (FD) were noted as motion outliers (Power et al., 2012, 2014). All transformations (i.e. head-motion transform matrices and co-registrations to anatomical and template MNI spaces) were performed with a single interpolation using antsApplyTransforms (ANTs v2.3.3) (Avants et al., 2008), configured with Lanczos interpolation (Lanczos, 1964).

Following preprocessing, AFNI v21.2.0437 was used for denoising. Voxel timeseries were scaled to a mean of 100 (3dTstat, 3dcalc). Nuisance regression included six realignment parameters and their first temporal derivatives, and the first five anatomical principal components from WM and CSF (Ciric et al., 2017; Matijevic et al., 2022). The data were linearly detrended and a bandpass filter (0.008–0.09 Hz) was applied.

There were no diagnostic differences in average motion (FD), F = 0.47, p = .496, no differences in FD due to Aβ-status, F = 0.57, p = .453, and no significant interaction of diagnosis and Aβ-status on FD, F = 0.87, p = .350.

2.3. Brain network construction

Average timeseries were extracted from 263 functionally defined spherical ROIs (radius = 4 or 5 mm) (Seitzman et al., 2020), which provided thorough coverage of cortical, subcortical, and cerebellar regions (Fig. 1A). The timeseries of each ROI pair were correlated and Fisher z-transformed to form a 263 × 263 ROI functional connectivity matrix (i.e., graph) in each participant. For redundancy calculations, matrices were binarized using a proportional threshold technique and self-connections were set to zero. To ensure that differences in redundancy were not dependent on graph density (Rubinov and Sporns, 2010), graphs were thresholded across a wide range (2.5–25 %, steps of 2.5 %)(Langella et al., 2021b) and redundancy was calculated at each threshold. To summarize redundancy properties across the wide range of densities sampled in the current analysis (2.5–25 %), area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to represent redundancy as a single scalar metric (Power et al., 2014). AUC has widely been applied in analyses of graph-based networks and is sensitive to detect pathological alterations in network topology (Lei et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2015).

Fig. 1.

Brain nodes and a priori defined regions of interest. (A) 263 nodes distributed across 14 networks displayed in glass brain. (B) A priori defined regions of interest displayed in radiological view. Regions of interest included the anterior and posterior bilateral hippocampi and the left frontal cortex. HC = hippocampus; AUD = auditory network; COP = cinguloopercular network; DAN = dorsal attention network; DMN = default mode network; FPN = frontoparietal network; MTL = medial temporal lobe network; PMN = parietomedial network; SAL = salience network; REW = reward network; SMD = somatomotor network dorsal; SML = somatomotor network lateral; UNA = unassigned; VAN = ventral attention network; VIS = visual network.

2.4. Functional redundancy

Global redundancy (Rglobal) captures the total number of repetitive (e.g., direct and indirect) connections between node pairs. A 263 × 263 redundancy matrix was formed by summing the total paths of lengths (l) = 1 to L for each node pair (Di Lanzo et al., 2012; Langella et al., 2021b):

L (maximum path length) was set to four based on computational demands and guidelines of previous work (Di Lanzo et al., 2012; Langella et al., 2021b). Higher Rglobal of node pair (s, t) suggests that there are many alternative pathways connecting nodes s and t.

To calculate the Rglobal of each region, row averages of the redundancy matrix were calculated. The resulting 263 × 1 column vector of redundancy values represents the average number of total connections (e.g., direct and indirect) between each ROI and its 262 connections. Five regions were defined a priori and selected for analysis (Fig. 1B) including the left and right posterior and anterior HC (Langella et al., 2021b) and the LFC (MNI, x = −41.06, y = 5.81, z = 32.72) (Franzmeier et al., 2018).

2.5. Direct and indirect paths

To further discern whether diagnostic and/or Aβ-status differences in Rglobal were attributed to direct or indirect connections, redundancy components (i.e., direct vs. indirect) were calculated separately. The total number of direct connections between node pairs (Rdirect) was quantified using node degree or the sum of each node's immediate connections (a; path length = 1) 49:

Rindirect represented the sum total of all indirect paths connecting node pairs (path length = 2–4). Thus, the Rindirect matrices excluded direct connections between each ROI-node pair.

To calculate the Rindirect of each region, row averages of the Rindirect matrix were calculated. The resulting 263 × 1 column vector of Rindirect values represents the average number of total indirect connections between each ROI and its 262 connections. Rindirect values from the five a priori defined regions were carried forward to analysis.

2.6. Cognitive performance

To explore redundancy-cognition relationships and the potential role of redundancy as a resilience factor, two domains of cognition affected early in AD were examined, including episodic memory and executive functioning performance. Composite measures of memory and executive functioning were computed by ADNI investigators using the item response theory framework (Crane et al., 2012; Gibbons et al., 2012). The memory composite was formed from measures including the RAVLT (learning trials 1–5, interference, immediate recall, delayed recall, recognition), ADAS-Cog (trials 1–3, recall, recognition present, recognition absent), Logical Memory (immediate, delayed), and MMSE (recall of ball, flag, tree word items). The executive function composite included performance from clock drawing, Trails (A, B), Category Fluency (animals, vegetables), WAIS-R Digit (symbol), and Digit Span (backwards). The composite variables were standardized to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 with higher scores representing better performance.

A high proportion (99 %) of the current sample completed a cognitive assessment within a year of their MR scans. One participant was missing data for memory testing and two participants were missing data for executive function testing and thus, were excluded separately for each cognitive domain analysis. The final sample consisted of 362 to explore memory-redundancy relationships and 361 to explore executive function-redundancy relationships.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (4.1.0). Demographic characteristics were compared between groups using the aov_car function from the afex package. Chi-square tests (chisq.test) were utilized to examine the influence of diagnosis and Aβ-status on sex and APOE4 carrier distribution. Models tested in relation to redundancy measures are described below. Statistical significance was determined based on adjustments for multiple comparisons using False Discovery Rate for confirmatory results (see Supplementary Materials for a list of confirmatory analyses). For exploratory analyses, uncorrected p-values are reported without adjustments for multiple testing.

2.7.1. Diagnostic and Aβ-status group differences in redundancy

Non-parametric ANCOVA models with 10,000 permutations were utilized to examine the effects of diagnosis and Aβ-status on regional redundancy metrics (i.e., Rglobal, Rdirect, Rindirect summarized by AUC). Age, sex, education, and APOE4 genotype were included in each model as covariates.

2.7.2. Moderation analyses

Moderation analyses were employed to explore whether the relationship between the degree of Aβ deposition and regional redundancy was dependent on diagnostic group or Aβ-status. Multiple linear regression models were explored using the lm function with ROI redundancy serving as the dependent variable and Aβ SUVR as the predictor, covarying for age, sex, education, and APOE4 genotype. To examine the moderating effect of diagnostic group, an interaction term of Aβ SUVR and diagnosis was entered into the model. To examine the moderating effect of Aβ-status, separate models were conducted in each diagnostic group (CN, MCI) and included an interaction term of Aβ SUVR and Aβ-status. Conditional effects of the moderation effects were explored using the probe_interaction function. Continuous variables were standardized prior to the regression, such that each variable had a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.

2.7.3. Redundancy relationships with education

Previous work provided preliminary evidence that posterior hippocampal redundancy may underlie resilience in brain aging (Langella et al., 2021b). To further probe this relationship, we examined the construct validity of redundancy as a resilience measure by examining its relationship with a proxy of cognitive resilience, namely years of education, for each a priori defined ROI. Specifically, multiple linear regression models were formed for each ROI, with years of education serving as the dependent variable and ROI redundancy as the predictor. Each model covaried for age, sex, and APOE4 carrier status. Continuous variables were standardized prior to the regression.

2.7.4. Redundancy relationships with cognition

To examine the relationship between regional redundancy and cognition, multiple linear regression models were formed for each domain (memory, executive function), with ROI redundancy as the predictor. Each model covaried for age, sex, and APOE4 carrier status. Continuous variables were standardized prior to the regression.

2.7.5. Test of the cognitive criterion of resilience

The cognitive criterion of resilience posits that neural substrates of resilience will be related to better cognitive performance in the face of brain pathology (Franzmeier et al., 2017). To test this, we employed multiple linear regressions to examine the moderating effect of redundancy on the relationship between the degree of Aβ deposition and cognitive performance (episodic memory, executive functioning). Tests were run separately for each cognitive domain (executive function, memory) and diagnostic group (CN, MCI). For each model, the cognitive composite score served as the dependent variable and Aβ SUVR and redundancy served as the predictor. To examine the moderating effect of redundancy, for each ROI, a redundancy-SUVR interaction term was added to the model. Age, sex, and APOE4 carrier status served as covariates.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Sample characteristics by diagnostic group and Aβ-status are summarized in Table 1. The main effects of diagnosis, F = 0.71, p = .400, and Aβ-status, F = 1.44, p = .232, on age were not significant. However, there was a significant interaction between diagnosis and Aβ-status on age, F = 5.70, p = .018, such that CN Aβ-were younger than MCI Aβ-, p = .017, and CN Aβ+, p = .006. No significant differences in years of education or sex were found across diagnostic and Aβ-status groups (p's > 0.05). There were no differences in distribution of APOE4 by diagnostic group (p > .05); however, as expected, Aβ+ individuals had a higher percentage of APOE4 carriers than Aβ-, χ2(1) = 45.92, p < 001. Finally, CN had better MMSE performance than MCI, regardless of Aβ status, while MCI Aβ-performed better than MCI Aβ+ (p's < 0.05).

3.2. Diagnostic and Aβ group differences in cognitive performance

We examined differences in memory and executive function performance by diagnostic group and Aβ-status (Fig. 2; Table 1). In terms of memory performance, both the main effects of diagnosis, F = 87.00, p < .001, and Aβ-status, F = 18.94, p < .001, were significant, as well as the interaction of diagnosis and Aβ-status, F = 8.11, p = .005 (Fig. 2A), indicating that diagnostic group differences in memory performance were dependent on Aβ-status such that within MCI, Aβ-had better memory performance than Aβ+ (p < .001), while, within CN, memory performance did not differ by Aβ-status (p = .243). For executive function, performance was only found to differ by diagnostic group, where CN had better executive function performance than MCI, F = 55.64, p < .001. (Fig. 2B). The main effect of Aβ status and interaction effect were not significant for executive function performance, (p's > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Cognitive performance by diagnostic group and Aβ-status on composite scores of (A) memory, and (B) executive function. Plotted composite scores were normalized via z-transformation and bars represent Mean ± SE.

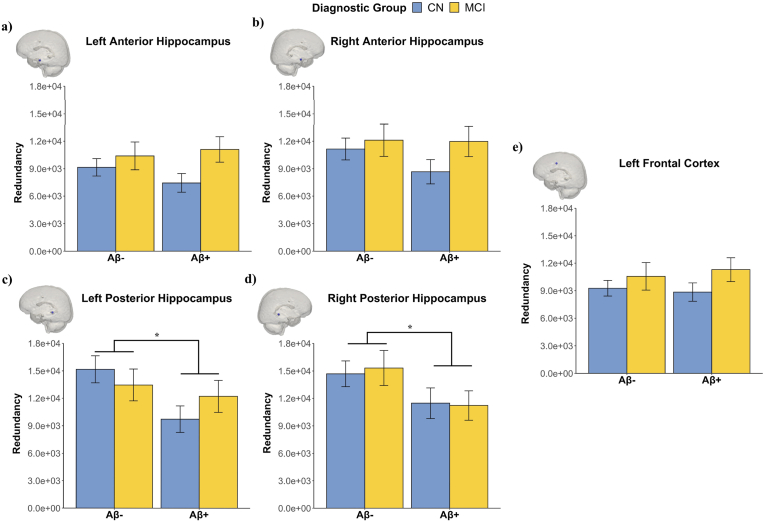

3.3. Posterior HC redundancy is lower in Aβ+ than Aβ- groups

To test our primary hypothesis, we examined whether functional redundancy (i.e., Rglobal) in five a priori defined regions of interest, including bilateral posterior hippocampi, bilateral anterior hippocampi, and LFC, would differ as a function of Aβ-status (Fig. 3). We found significant differences by Aβ-status in the left posterior HC, F = 4.64, p = .032, and the right posterior HC, F = 6.15, p = .014, showing higher redundancy in Aβ-than Aβ+ in the left and the right posterior HC (Fig. 3C and D). No significant differences by Aβ-status were found for the left and right anterior hippocampus or LFC. The Aβ-status effect on posterior HC Rglobal remained significant after FDR correction.

Fig. 3.

Functional redundancy by diagnostic group and Aβ-status in five a priori regions of interest. Plotted values represent functional redundancy of the (A) left anterior HC, (B) right anterior HC, (C) left posterior HC, (D) right posterior HC, and (E) left frontal cortex. Functional redundancy is summarized by AUC across the density thresholds 0.025–0.25 [steps of 0.025]) and bars represent Mean ± SE. ∗p < .05.

As exploratory analyses, we examined the effect of diagnosis and interactions between diagnosis and Aβ-status in these five ROIs. There were no significant diagnostic differences in Rglobal (F = 0.20, p = .659 for left posterior HC; F = 0.003, p = .954 for the right posterior HC). Interactions between diagnosis and Aβ-status on Rglobal for the left or right posterior HC were not significant (p's > 0.05). For the left and right anterior HC and the LFC, neither the main effect of diagnosis nor the interaction effect on Rglobal were found (p's > 0.05).

3.4. Diagnostic and Aβ-status group differences in direct vs. indirect connections

To gain a more thorough understanding of how diagnosis and Aβ-status affect hippocampal and LFC redundancy measures, we further explored the constituent properties of redundancy, including direct (i.e., Rdirect) and indirect connections (i.e., Rindirect), separately as a function of diagnosis, Aβ-status, and their interaction.

3.4.1. Direct connections

When examining direct connections underlying Rglobal, we found that the Aβ-exhibited higher Rdirect than Aβ+ for the right posterior hippocampus, F = 5.59, p = .018. A similar trend was seen for the left posterior HC, F = 3.34, p = .068. Neither diagnosis effects nor interactions were significant in posterior HC ROIs (p's > 0.05).

For both the left and right anterior HC ROIs, MCI exhibited more direct connections than CN (the left anterior HC, F = 4.66, p = .034, and right anterior HC, F = 5.13, p = .025). There were neither Aβ-status differences nor interaction effects in left or right anterior HC Rdirect (p's > 0.05). For the LFC, none of these effects were significant (p's > 0.05).

3.4.2. Indirect connections

For indirect connections underlying Rglobal, Aβ-had a higher number of indirect connections with both the left and right posterior HC ROIs than Aβ+ (the left posterior HC, F = 4.64, p = .032, and the right posterior HC, F = 6.15, p = .012). Neither diagnosis nor interactions were significant in posterior HC ROIs (p's > 0.05). For the left and right anterior HC and LFC, neither main effects of diagnosis or Aβ-status nor interactions were found (p's > 0.05).

3.5. Moderation by diagnosis and Aβ-status on SUVR-redundancy relationship

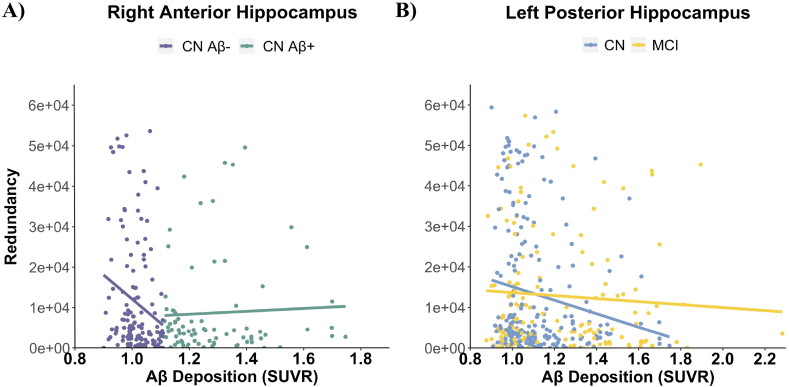

Though the Aβ-group showed greater Rglobal than Aβ+ across CN and MCI groups, primarily in the posterior HC, we further explored whether the relationships between the level of Aβ deposition, measured continuously through SUVR, and redundancy differed by Aβ-status within each diagnostic group or by diagnosis. There were significant moderation effects of the SUVR-Rglobal relationship in right anterior and left posterior HC regions. Results from the corresponding regression models can be found in Table 2, Table 3 and Fig. 4. Regression parameters for other regions (i.e., left anterior HC, right posterior HC, and LFC) are reported in the Supplementary Material.

Table 2.

Regression parameters for the moderation of the Aβ deposition and right anterior hippocampus relationship by Aβ-status and diagnosis. +p < .10; ∗p < .05; ∗∗p < .01.

| Group | R (Jagust, 2013)/Model p-value | Predictors | β | Uncorrected pvalue | Corrected p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | R (Jagust, 2013) = 0.09 | Age | 0.188 | 0.012∗ | 0.062+ |

| p = .005 | Sex | −0.35 | 0.011∗ | 0.062+ | |

| Education | −0.04 | 0.565 | 0.682 | ||

| APOE4 | 0.029 | 0.846 | 0.935 | ||

| SUVR | −0.97 | 0.005∗∗ | 0.062+ | ||

| Aβ-status | 0.386 | 0.159 | 0.364 | ||

| SUVR∗Aβ-status | 0.951 | 0.012∗ | 0.062+ | ||

| MCI | R (Jagust, 2013) = 0.026 | Age | −0.003 | 0.974 | 0.974 |

| p = .828 | Sex | 0.014 | 0.94 | 0.974 | |

| Education | −0.067 | 0.444 | 0.621 | ||

| APOE4 | −0.216 | 0.309 | 0.468 | ||

| SUVR | 0.659 | 0.227 | 0.397 | ||

| Aβ-status | −0.473 | 0.312 | 0.468 | ||

| SUVR∗Aβ-status | −0.748 | 0.185 | 0.364 | ||

| R (Jagust, 2013) = 0.024 | Age | 0.09 | 0.114 | 0.341 | |

| p = .271 | Sex | −0.189 | 0.09+ | 0.313 | |

| Education | −0.029 | 0.585 | 0.682 | ||

| APOE4 | −0.068 | 0.576 | 0.682 | ||

| SUVR | −0.177 | 0.062+ | 0.26 | ||

| Diagnosis | 0.168 | 0.135 | 0.355 | ||

| SUVR∗Diagnosis | 0.149 | 0.191 | 0.364 |

Table 3.

Regression parameters for the moderation of the Aβ deposition and left posterior hippocampus relationship by Aβ-status and diagnosis. +p < .10; ∗p < .05; ∗∗p < .01.

| Group | R (Jagust, 2013)/Model p-value | Predictors | β | Uncorrected pvalue | Corrected p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | R (Jagust, 2013) = 0.092 | Age | 0.245 | 0.002∗∗ | 0.024∗ |

| p = .004 | Sex | −0.237 | 0.104 | 0.242 | |

| Education | 0.041 | 0.578 | 0.617 | ||

| APOE4 | −0.244 | 0.128 | 0.27 | ||

| SUVR | −0.661 | 0.073+ | 0.218 | ||

| Aβ-status | 0.015 | 0.959 | 0.959 | ||

| SUVR∗Aβ-status | 0.495 | 0.217 | 0.35 | ||

| MCI | R (Jagust, 2013) = 0.064 | Age | 0.09 | 0.276 | 0.414 |

| p = .246 | Sex | −0.092 | 0.587 | 0.617 | |

| Education | 0.165 | 0.035∗ | 0.145 | ||

| APOE4 | 0.193 | 0.306 | 0.428 | ||

| SUVR | 0.614 | 0.206 | 0.35 | ||

| Aβ-status | −0.301 | 0.469 | 0.616 | ||

| SUVR∗Aβ-status | −0.713 | 0.156 | 0.298 | ||

| R (Jagust, 2013) = 0.054 | Age | 0.155 | 0.006∗∗ | 0.039∗ | |

| p = .006 | Sex | −0.189 | 0.083+ | 0.219 | |

| Education | 0.112 | 0.036∗ | 0.145 | ||

| APOE4 | −0.069 | 0.564 | 0.617 | ||

| SUVR | −0.286 | 0.002∗∗ | 0.024∗ | ||

| Diagnosis | 0.063 | 0.565 | 0.617 | ||

| SUVR∗Diagnosis | 0.229 | 0.042∗ | 0.145 |

Fig. 4.

Different relationships between Aβ deposition and hippocampal redundancy by Aβ-status and diagnosis. (A) Right anterior HC redundancy-Aβ SUVR relationship by amyloid-status in CN. Continuous amyloid SUVR (x-axis) and functional redundancy in the right anterior HC (y-axis) are plotted as a function of Aβ-status. Aβ− CN is depicted in purple and Aβ+ CN is depicted in green. A best fitting regression line for each CN group is shown in the scatterplot (A). (B) Left posterior HC redundancy-Aβ SUVR relationship by diagnosis. Continuous amyloid SUVR (x-axis) and functional redundancy in the left posterior HC (y-axis) are plotted as a function of diagnosis. CN is depicted in blue and MCI is depicted in yellow. A best fitting regression line for each diagnostic group is shown in the scatterplot (B).

3.5.1. Right anterior HC redundancy-Aβ SUVR relationships differ by amyloid-status in cognitively normal older adults

In CN, the relationship between Aβ level and right anterior HC Rglobal differed by Aβ-status, β = 0.951, p = .012 (Fig. 4A; Table 2), such that higher Aβ SUVR was associated with lower right anterior HC Rglobal in Aβ- (p = .01) and this relationship was not significant for Aβ+ (p = .90). The relationship between Aβ level and redundancy did not differ by Aβ-status in other ROIs in CN (p's > 0.05). In MCI, Aβ-status did not significantly moderate the relationship between Aβ level and Rglobal in any regions, p's > 0.05.

3.5.2. Left posterior HC redundancy-Aβ SUVR relationships differ by diagnosis

When we examined the relationship between Aβ level and HC Rglobal by diagnosis, we found that the relationship between amyloid SUVR and left posterior HC redundancy was significantly different by diagnostic group, β = 0.229, p = .042 (Fig. 4B; Table 3). Simple slopes analysis revealed that higher Aβ SUVR was associated with lower left posterior HC Rglobal in CN (p < .001), while this relationship was not significant for MCI (p = .41). Diagnosis did not moderate the relationship between Aβ level and Rglobal in other ROIs (p's > 0.05). These results further support reduced posterior HC functional redundancy with a higher Aβ level even among cognitively normal older adults.

3.6. Posterior HC redundancy related to higher years of education

To further test the potential role of redundancy in posterior HC as a resilience factor, the relationships between Rglobal, in posterior HC, and years of education were tested. Based on past work, we expected that redundancy would be positively associated with years of education (Langella et al., 2021b). Analyses were collapsed across diagnostic groups. In line with our hypothesis, we found that higher years of education was related to higher left posterior HC redundancy (β = 0.12, p = .022). The positive association between education and redundancy in the right posterior hippocampus was only at trend-level (β = 0.098, p = .062) (Fig. 5). As exploratory analyses, redundancy in three other a priori selected ROIs were correlated with years of education. None were found to be significant (p's > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Relationships between posterior hippocampal redundancy and years of education. Redundancy values are represented on the x-axis and the years of education are represented on the y-axis for the (A) left posterior hippocampus and (B) right posterior hippocampus. The best fitting regression line is depicted in each plot.

3.7. Posterior HC redundancy related to better memory performance

To test if redundancy in posterior HC confers a cognitive advantage, we examined redundancy-cognition relationships in posterior HC. Higher Rglobal in the left posterior HC, β = 0.134, p = .007, and right posterior HC, β = 0.167, p = .001, were related to better memory performance across CN and MCI groups (Fig. 6), which is consistent with previous findings (Cole et al., 2012). When we further explored whether the HC redundancy and cognition relationship differ by Aβ status, the positive relationship between memory and HC redundancy was found for both left and right posterior HC in Aβ-, (left posterior HC: β = 0.183, p = .004; right posterior HC: β = 0.163, p = .011), but not in Aβ+, (left posterior HC: β = −0.002, p = .982; right posterior HC: β = 0.109, p = .177). No significant relationship between memory performance and Rglobal was found in the three other a priori selected ROIs (p's > 0.05). With executive function performance, no cognition-Rglobal relationships were significant in any ROI (p's > 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Posterior hippocampal redundancy relations with memory performance. Plotted are composite memory scores on the y-axis and redundancy on the x-axis for the (A) left posterior hippocampus, and (B) right posterior hippocampus. Aβ− is depicted in purple and Aβ+ is depicted in green collapsing both CN and MCI groups. Regression coefficients of the relationships between regional redundancy and memory in each Aβ group are displayed in the bottom right portion of each plot.

3.8. Regional functional redundancy did not moderate pathology-cognition relationships

Finally, as a final test of the potential role of redundancy in cognitive resilience, we explored whether posterior HC redundancy measures moderated the relationship between pathology and cognition. Analyses were conducted separately for CN and MCI groups and for memory and executive composite scores. For both memory and executive function composite scores, no significant moderation effects were found for either the left or right posterior HC redundancy levels (p's > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Understanding the neural mechanisms underlying resilience in brain aging has significant implications for early intervention and prevention strategies in AD. In the current investigation, we examined whether regional functional redundancy, a complex systems-based network property, confers resilience in the presence of Aβ deposition among non-demented older adults. Our results revealed several noteworthy findings: (1) functional redundancy in the posterior hippocampi, but not the anterior hippocampi or LFC, was lower with Aβ deposition, independent of diagnosis; (2) higher posterior HC redundancy was significantly associated with higher years of education and better memory performance, especially among Aβ-individuals; and (3) functional redundancy does not underlie the resilience effects of global LFC connectivity. In the exploratory analyses, we observed several findings: (1) when we explored functional redundancy by separating direct and indirect connection measures, Aβ deposition was associated with lower redundancy in both left and right posterior HC redundancy for indirect connections and lower right posterior HC redundancy for direct connections; (2) a diagnosis of MCI was found to be related to higher anterior HC redundancy, only for direct connections; and (3) redundancy in the HC and LFC did not moderate the cognition and Aβ positivity relationship in the early stages of AD pathology. To our knowledge, this is the first study that examines Aβ-related changes in functional redundancy.

Existing evidence suggests that functional, morphological, and neurochemical markers are impaired with an increased level of Aβ deposition, even among clinically intact older adults. Despite such disruptions in brain integrity in relation to Aβ deposition, some brain regions or networks paradoxically exhibit increased neural activity or connectivity (Franzmeier et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2016), which has been construed as neural substrates underlying resilience in the presence of AD pathology. Recently, metrics capturing complex systems-based network integrity, such as functional redundancy of the posterior hippocampi (Langella et al., 2021b), rather than the strength of temporal synchrony between two distinct regions, have been proposed to underlie resilience in brain aging. To further examine whether these redundancy measures confer cognitive resilience to AD pathologies, we used a graph theoretical approach to estimate functional redundancy and tested whether they change as a function of Aβ-positivity status and diagnosis. We found that with Aβ-positivity status, functional redundancy was reduced, rather than increased, and did not serve as cognitive resilience to brain Aβ deposition. Reduced functional redundancy was selectively observed in the left and right posterior HC, but not anterior hippocampi or LFC. The Aβ-related effects were evident for both direct and indirect portions of redundancy for bilateral, but more so in right posterior HC. The redundancy metric is a comprehensive metric of regional connectivity, in that it captures not only the integrity of the connectivity profile of the ROI itself (e.g., right posterior HC direct connections), but also the integrity of the connectivity profiles of the graphical neighbors of the ROI (e.g., precuneus, retrosplenial cortex). Thus, by separately assessing direct and indirect connections of each ROI, our findings further indicate that brain Aβ deposition relates to not only reduced connectivity of the posterior hippocampus but also that of its neighboring regions.

It is intriguing that Aβ-related differences in functional redundancy in the current study were regionally specific to the posterior HC, but not other a priori selected AD-vulnerable ROIs, such as the anterior HC. Previous findings suggest that two cortical networks, the anterior temporal (AT) and posterior medial (PM) systems, converge within the hippocampus (Ranganath and Ritchey, 2012) and exhibit distinct functional connections. The AT system, which is strongly connected to the anterior HC, includes the anteriolateral entorhinal cortex, perirhinal cortex, amygdala, ventral temperopolar cortex, and lateral orbitofrontal cortex. On the other hand, the posterior HC is strongly connected to the PM system, which includes the posteriomedial entorhinal cortex, parahippocampal cortex, retrosplenial cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and precuneus. These two cortical networks not only present unique connectivity patterns with other brain regions but also are functionally distinctive – the AT system has been implicated in processing item-specific components of episodic memory, while the PM system is involved in processing contextual elements of episodic memory (Ranganath and Ritchey, 2012; Libby et al., 2012). More importantly, the AT and PM systems are differentiated by their selective susceptibility to AD pathology in the early stage of AD pathology, as regions of the AT network are most burdened by tau pathology while the PM network is most vulnerable to Aβ pathology (Dautricourt et al., 2021; Maass et al., 2019). The susceptibility of the PM system to Aβ pathology is supported by the extant AD literature, which demonstrates that major hubs of the PM, including the precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex, are some of the earliest regions to exhibit and drive Aβ deposition (Buckner et al., 2008; Palmqvist et al., 2017). A potential consequence of such regional Aβ accumulation is cascading network failure (Jones et al., 2016) that ultimately disrupts connectivity between these posterior hubs, the posterior HC (Jones et al., 2016; Gardini et al., 2015; Qi et al., 2010), and throughout the brain (Jones et al., 2016). Our results are consistent with previous studies and further indicate that functional redundancy serves as a rich single-scalar metric that captures brain-wide disruptions to direct and indirect network paths connected to the posterior hippocampi, including the PM network particularly vulnerable to Aβ pathology in AD.

On the other hand, redundancy levels in the anterior HC did not differ by Aβ-status. This finding is congruent with the reported distinct vulnerability of anterior and posterior hippocampal systems to AD pathology (Dautricourt et al., 2021; Maass et al., 2019). We did, however, find evidence of diagnostic differences, particularly when the global redundancy measure was segregated into direct and indirect components. Specifically, we observed that MCI had, on average, higher levels of direct connections between the left or right anterior HC and all other brain regions compared to CN. Consistent with these findings, a recent study showed that MCI and AD patients exhibited hyperconnectivity between the anterior hippocampus and the AT system, which may be driven by tau accumulation (Dautricourt et al., 2021; Berron et al., 2021). Thus, our results are consistent with previous reports, although, without measures of tau pathology it is difficult to discern the affiliated or underlying neurobiological alterations that may have driven increased anterior HC direct connections in MCI in the present study. Future studies are needed to examine the detrimental effects of Aβ on posterior systems paired with advancing MTL tau pathology that may mediate system-level network reorganization in MCI.

Despite differing methodologies (e.g., static functional connectivity, dynamic functional connectivity) and scales (e.g., regional, network, whole brain) used to assess functional redundancy, the literature has documented a consistent positive association between higher redundancy levels and better cognitive performance (Ghanbari et al., 2023; Langella et al., 2021b). It is difficult, however, to decipher the role of resilience in pathological cognitive aging from past work, considering that underlying pathological profiles were not evaluated. Consistent with past work, we found that, at the regional-level, posterior, but not anterior, HC redundancy conferred a cognitive benefit, such that higher left or right posterior HC redundancy was related to better episodic memory performance. We extend past work by demonstrating that this relationship was primarily driven by Aβ-groups. These results may suggest that once pathological levels of brain Aβ are reached, higher redundancy no longer confers functional benefits. However, longitudinal studies are needed to test such hypotheses.

To explicitly determine if regional redundancy exhibits properties of a resilience factor, we examined the relationship between regional redundancy and years of education, a commonly used proxy of cognitive resilience. We found that only redundancy within the left and right posterior HC, but not anterior hippocampi or LFC, were positively related to years of education. These findings provide insight that posterior HC redundancy may be shaped by early life experiences and further supports that it has the potential to play a role in resilience of brain aging (Langella et al., 2021b).

Based on the previous studies that showed increased neural activity and glucose utilization with increased brain Aβ deposition in the PM system and their moderation effect on cognition, we hypothesized increased functional redundancy in the regions of interest with Aβ positivity status. However, despite the significant relationships between posterior HC redundancy, education, and memory, posterior HC redundancy did not moderate the relationship between Aβ deposition and cognitive performance (i.e., memory, executive function). There are several possibilities that may explain this observation. First, it is possible that posterior HC redundancy in our sample has already undergone substantial detrimental changes associated with Aβ, as evidenced as decreased functional redundancy in these regions, and thereby, does not afford cognitive resilience to Aβ pathology. Second, the cognitive composites might not have been specific enough to capture the Aβ-related functional changes in the posterior HC or the PM system in general. Third, as previously reported, different regions or networks that are not part of the PM system may play a role of resilience. Using a dynamic functional redundancy measure, a graph theory metric that measures reachability from any node to any other node in the network through an independent path, Ghanbari and colleagues (Ghanbari et al., 2022) showed that, despite gradual reduction in the redundancy of the default mode network along the AD continuum, there was generally increased subnetwork redundancy in MCI particularly within the subcortical-cerebellum subnetwork. Thus, it is possible that brain regions that are not part of the networks connected to our a priori-selected AD vulnerable ROIs may play a role of resilience. A longitudinal examination of the relationship between whole brain functional redundancy, Aβ pathology, and cognitive performance with a more specific cognitive measure will help to understand the trajectory of Aβ-related changes in functional redundancy and their role in moderating the brain Aβ deposition and cognitive changes.

One of the goals of the present study was to assess the functional redundancy of LFC as a function of Aβ deposition. Preserved functional connectivity strength of LFC has been consistently reported as neural substrates supporting cognitive resilience in the presence of Aβ deposition or MCI status. Compared to posterior HC redundancy, we found that redundancy of the LFC did not differ by diagnosis or Aβ-status. This finding is analogous to past work examining functional connectivity of the LFC in the presence of AD pathologies (Franzmeier et al., 2017, 2018), and suggests that LFC connectivity is relatively unaffected by Aβ pathology or progression across the AD continuum. Maintaining functional connectivity to the LFC in the presence of AD pathology could potentially compensate for network failure that occurs in brain regions as a result of accumulating pathology. However, the LFC redundancy did not moderate the relationship between Aβ status and memory and executive function measures in the present study. Thus, our results indicate that connectivity strength, rather than redundancy, underscores LFC-mediated resilience in AD (Franzmeier et al., 2017).

Several limitations to the current study need to be noted. First, our ability to draw conclusions concerning the temporal relations between Aβ deposition, disrupted posterior HC redundancy, and relative changes across the AD continuum are limited by the cross-sectional design. For example, we interpret that reduced posterior HC redundancy may occur as a result of preferential deposition of Aβ and the subsequent disruption of posterior networks. However, alternative explanations cannot be ruled out due to the cross-sectional design. Rather, it could be that lower HC redundancy marks inefficient neural processing. Coupled with increasing age and other biological risk factors (e.g., APOE4), such inefficiency may tax the system and drive vulnerability for Aβ deposition. It will be important in follow up studies to utilize a longitudinal design to illuminate the temporal relationship between posterior HC redundancy and vulnerability to Aβ. Regardless of their temporal order, our results indicate concurrent presence of Aβ deposition and reduced functional redundancy. Second, to expand on promising previous work illustrating the potential role of posterior HC redundancy as a cognitive resilience factor in aging (Langella et al., 2021b), we considered Aβ deposition as our primary marker of AD pathology. However, given the particular sensitivity of the anterior HC network to tau accumulation (Maass et al., 2019) and the synergistic effects of Aβ and tau to disrupt functional networks (Berron et al., 2021), it will be important in future studies to examine both pathological hallmarks in redundancy-based metrics of these regions. Moreover, five a priori regions were selected for analysis based on their documented vulnerability to pathological aging. However, considering that AD not only affects regional functionality, but also disrupts large-scale networks, it will be important in future work to consider regional and network-level redundancy simultaneously. Indeed, promising work has documented how levels of whole brain, network, and regional redundancy differ across the AD clinical continuum (Ghanbari et al., 2023). However, it will be important in future work to incorporate measures of AD pathology to examine redundancy alterations across the AD continuum within groups stratified by pathology. Despite the regional selectivity of reduced functional redundancy in the posterior, not anterior, HC, regions, we do not think that this is due to greater atrophy in the posterior brain regions such as parietal cortex, as previous studies have indicated greater atrophy in widespread brain regions including the frontal cortex with a higher level of Aβ deposition among cognitively normal older adults and across AD continuum (Oh et al., 2011, 2014a; Becker et al., 2011; Storandt et al., 2009). On a technical note, redundancy was calculated based on proportionally-thresholded networks, where functional connections were derived using bivariate correlation procedures. Though bivariate correlation is one of the most commonly employed methodologies to estimate nodal connections, it can produce spurious correlations among nodes due to an inability to disambiguate if connectivity results as an involvement of a collider or indirect association (Reid et al., 2019; Sanchez-Romero and Cole, 2021). An additional limitation includes the limited diversity of the sample. It is well-documented that AD disproportionately affects under-represented populations, in particular Black Americans (Gurland et al., 1999; Steenland et al., 2016). Mounting evidence suggests that early life factors, such as years or quality of education, significantly contributes to racial disparities in cognitive levels, including episodic memory (Sisco et al., 2015; Yaffe et al., 2013). Considering that posterior hippocampal redundancy, in particular, is related to memory performance and may be shaped by early life experiences, as evidenced by its positive association with years of education, it will be critically important to examine such a metric in an ethnically diverse sample. These limitations, however, should not undermine the strengths and novelty of the current study, including a well-powered sample size and novel characterization of functional redundancy in the context of early stages of Aβ pathology.

5. Conclusion

In summary, functional redundancy represents a rich metric that captures not only the functional integrity of the primary region of interest but also the functional integrity of the region's graphical neighbors. Using this rigorous dimensionality, our study shows novel findings that functional redundancy in the posterior hippocampus is lower with Aβ pathology and may serve as a marker of pathological brain aging status.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jenna K. Blujus: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Michael W. Cole: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Elena K. Festa: Writing – review & editing. Stephen L. Buka: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Stephen P. Salloway: Writing – review & editing. William C. Heindel: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Hwamee Oh: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Data availability

All datasets utilized in the current analysis are available from the ADNI repository for download at https://adni.loni.usc.edu.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers AG068990, AG069265, OD025181].

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer's Association; Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynirp.2025.100255.

Contributor Information

Jenna K. Blujus, Email: jenna_blujus@brown.edu.

Hwamee Oh, Email: hwamee_oh@brown.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Arenaza-Urquijo E.M., Vemuri P. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology. 2018;90:695–703. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants B.B., Epstein C.L., Grossman M., Gee J.C. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med. Image Anal. 2008;12:26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J.A., et al. Amyloid-beta associated cortical thinning in clinically normal elderly. Ann. Neurol. 2011;69:1032–1042. doi: 10.1002/ana.22333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzadi Y., Restom K., Liau J., Liu T.T. A component based noise correction method (CompCor) for BOLD and perfusion based fMRI. Neuroimage. 2007;37:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.042. : [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzinger T.L., et al. Regional variability of imaging biomarkers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:E4502–E4509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317918110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berron D., et al. Early stages of tau pathology and its associations with functional connectivity, atrophy and memory. Brain. 2021;144:2771–2783. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billinton R., Allan R.N. vol. 792. Plenum press; 1992. (Reliability Evaluation of Engineering Systems). [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner R.L., Andrews-Hanna J.R., Schacter D.L. The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciric R., et al. Benchmarking of participant-level confound regression strategies for the control of motion artifact in studies of functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2017;154:174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M.W., Yarkoni T., Repovs G., Anticevic A., Braver T.S. Global connectivity of prefrontal cortex predicts cognitive control and intelligence. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:8988–8999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0536-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M.W., et al. Multi-task connectivity reveals flexible hubs for adaptive task control. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:1348–1355. doi: 10.1038/nn.3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R.W., Hyde J.S. Software tools for analysis and visualization of fMRI data. NMR Biomed. 1997;10:171–178. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199706/08)10:4/5<171::aid-nbm453>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane P.K., et al. Development and assessment of a composite score for memory in the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Brain Imaging Behav. 2012;6:502–516. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9186-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L., et al. Small vessel disease and cognitive reserve oppositely modulate global network redundancy and cognitive function: a study in middle-to-old aged community participants. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2024;45 doi: 10.1002/hbm.26634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale A.M., Fischl B., Sereno M.I. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9:179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. https://doi.org:S1053-8119(98)90395-0 [pii] 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautricourt S., et al. Longitudinal changes in hippocampal network connectivity in alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 2021;90:391–406. doi: 10.1002/ana.26168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lanzo C., Marzetti L., Zappasodi F., De Vico Fallani F., Pizzella V. Redundancy as a graph-based index of frequency specific MEG functional connectivity. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/207305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban O., et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods. 2019;16:111–116. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0235-4. : [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmeier N., et al. Left frontal cortex connectivity underlies cognitive reserve in prodromal Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2017;88:1054–1061. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmeier N., et al. Left frontal hub connectivity delays cognitive impairment in autosomal-dominant and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2018;141:1186–1200. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardini S., et al. Increased functional connectivity in the default mode network in mild cognitive impairment: a maladaptive compensatory mechanism associated with poor semantic memory performance. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45:457–470. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari M., et al. Alterations of dynamic redundancy of functional brain subnetworks in Alzheimer's disease and major depression disorders. Neuroimage Clin. 2022;33 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari M., Li G., Hsu L.M., Yap P.T. Accumulation of network redundancy marks the early stage of Alzheimer's disease. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023;44:2993–3006. doi: 10.1002/hbm.26257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons L.E., et al. A composite score for executive functioning, validated in Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) participants with baseline mild cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav. 2012;6:517–527. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9176-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgolewski K., et al. Nipype: a flexible, lightweight and extensible neuroimaging data processing framework in python. Front. Neuroinf. 2011;5:13. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2011.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve D.N., Fischl B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage. 2009;48:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurland B.J., et al. Rates of dementia in three ethnoracial groups. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 1999;14:481–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden T., et al. Disruption of functional connectivity in clinically normal older adults harboring amyloid burden. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:12686–12694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3189-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust W. Vulnerable neural systems and the borderland of brain aging and neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2013;77:219–234. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M., Bannister P., Brady M., Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.T., et al. Cascading network failure across the Alzheimer's disease spectrum. Brain. 2016;139:547–562. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R., et al. Clinical, pathological, and neurochemical changes in dementia: a subgroup with preserved mental status and numerous neocortical plaques. Ann. Neurol. 1988;23:138–144. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanczos C. Evaluation of noisy data. J. Soc. Ind. Appl. Math. B Numer. Anal. 1964;1:76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Langella S., Mucha P.J., Giovanello K.S., Dayan E. & for the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, I. The association between hippocampal volume and memory in pathological aging is mediated by functional redundancy. Neurobiol. Aging. 2021;108:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langella S., et al. Lower functional hippocampal redundancy in mild cognitive impairment. Transl. Psychiatry. 2021;11:61. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01166-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei D., et al. Disrupted functional brain connectome in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Radiology. 2015;276:818–827. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15141700. : [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei B., et al. Longitudinal study of early mild cognitive impairment via similarity-constrained group learning and self-attention based SBi-LSTM. Knowl. Base Syst. 2022;254 [Google Scholar]

- Li W., et al. Functional evolving patterns of cortical networks in progression of alzheimer's disease: a graph-based resting-state fMRI study. Neural Plast. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/7839536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby L.A., Ekstrom A.D., Ragland J.D., Ranganath C. Differential connectivity of perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices within human hippocampal subregions revealed by high-resolution functional imaging. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:6550–6560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3711-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G., et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396:413–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C.Y., et al. Functional connectome assessed using graph theory in drug-naive Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. 2015;262:1557–1567. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7750-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass A., et al. Alzheimer's pathology targets distinct memory networks in the ageing brain. Brain. 2019;142:2492–2509. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matijevic S., Andrews-Hanna J.R., Wank A.A., Ryan L., Grilli M.D. Individual differences in the relationship between episodic detail generation and resting state functional connectivity vary with age. Neuropsychologia. 2022;166 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2021.108138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormino E.C., et al. Relationships between beta-amyloid and functional connectivity in different components of the default mode network in aging. Cerebr. Cortex. 2011;21:2399–2407. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuropathology Group. Medical Research Council Cognitive, F. Aging S. Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in england and wales. Neuropathology group of the medical research council cognitive function and ageing study (MRC CFAS) Lancet. 2001;357:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H., et al. beta-Amyloid affects frontal and posterior brain networks in normal aging. Neuroimage. 2011;54:1887–1895. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H., Madison C., Villeneuve S., Markley C., Jagust W.J. Association of gray matter atrophy with age, beta-amyloid, and cognition in aging. Cerebr. Cortex. 2014;24:1609–1618. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H., Habeck C., Madison C., Jagust W. Covarying alterations in Abeta deposition, glucose metabolism, and gray matter volume in cognitively normal elderly. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014;35:297–308. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H., Madison C., Baker S., Rabinovici G., Jagust W. Dynamic relationships between age, amyloid-beta deposition, and glucose metabolism link to the regional vulnerability to Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2016;139:2275–2289. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H., Razlighi Q.R., Stern Y. Multiple pathways of reserve simultaneously present in cognitively normal older adults. Neurology. 2018;90:e197–e205. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossenkoppele R., et al. Is verbal episodic memory in elderly with amyloid deposits preserved through altered neuronal function? Cerebr. Cortex. 2014;24:2210–2218. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmqvist S., et al. Earliest accumulation of beta-amyloid occurs within the default-mode network and concurrently affects brain connectivity. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1214. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01150-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power J.D., Barnes K.A., Snyder A.Z., Schlaggar B.L., Petersen S.E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2142–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power J.D., et al. Methods to detect, characterize, and remove motion artifact in resting state fMRI. Neuroimage. 2014;84:320–341. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J.L., Morris J.C. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and "preclinical" Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1999;45:358–368. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<358::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-x. : [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z., et al. Impairment and compensation coexist in amnestic MCI default mode network. Neuroimage. 2010;50:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C., Ritchey M. Two cortical systems for memory-guided behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;13:713–726. doi: 10.1038/nrn3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid A.T., et al. Advancing functional connectivity research from association to causation. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:1751–1760. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0510-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann A., et al. Accelerated decline in white matter integrity in clinically normal individuals at risk for Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2016;42:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinov M., Sporns O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq M.U., Langella S., Giovanello K.S., Mucha P.J., Dayan E. Accrual of functional redundancy along the lifespan and its effects on cognition. Neuroimage. 2021;229 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.117737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Romero R., Cole M.W. Combining multiple functional connectivity methods to improve causal inferences. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 2021;33:180–194. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_01580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitzman B.A., et al. A set of functionally-defined brain regions with improved representation of the subcortex and cerebellum. Neuroimage. 2020;206 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisco S., et al. The role of early-life educational quality and literacy in explaining racial disparities in cognition in late life. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015;70:557–567. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R.A., Karlawish J., Johnson K.A. Preclinical Alzheimer disease-the challenges ahead. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013;9:54–58. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford W., Mucha P.J., Dayan E. Age-related differences in network controllability are mitigated by redundancy in large-scale brain networks. Commun. Biol. 2024;7:701. doi: 10.1038/s42003-024-06392-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K., Goldstein F.C., Levey A., Wharton W. A meta-analysis of alzheimer's disease incidence and prevalence comparing african-Americans and caucasians. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50:71–76. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2002;8:448–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y., Alexander G.E., Prohovnik I., Mayeux R. Inverse relationship between education and parietotemporal perfusion deficit in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1992;32:371–375. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storandt M., Mintun M.A., Head D., Morris J.C. Cognitive decline and brain volume loss as signatures of cerebral amyloid-beta peptide deposition identified with Pittsburgh compound B: cognitive decline associated with Abeta deposition. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:1476–1481. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson J., et al. Sex difference in brain functional connectivity of hippocampus in Alzheimer's disease. Geroscience. 2024;46:563–572. doi: 10.1007/s11357-023-00943-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K., et al. Effect of socioeconomic disparities on incidence of dementia among biracial older adults: prospective study. BMJ. 2013;347 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets utilized in the current analysis are available from the ADNI repository for download at https://adni.loni.usc.edu.