Summary

Background

Machine learning could improve the timely identification of trauma patients in need of hemorrhage control resuscitation (HCR), but the real-life performance remains unknown. The ShockMatrix study aimed to compare the predictive performance of a machine learning algorithm with that of clinicians in identifying the need for HCR.

Methods

Prospective, observational study in eight level-1 trauma centers. Upon receiving a prealert call, trauma clinicians in the resuscitation room entered nine predictor variables into a dedicated smartphone app and provided a subjective prediction of the need for HCR. These predictors matched those used in the machine learning model. The primary outcome, need for HCR, was defined as: transfusion in the resuscitation room, transfusion of more than four red blood cell units in 6 h of admission, any hemorrhage control procedure within 6 h, or death from hemorrhage within 24 h. The human and machine learning performances were assessed by sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, and net clinical benefit. Human and machine learning agreement was assessed with Cohen's kappa coefficient.

Findings

Between August 2022 and June 2024, out of 5550 potential eligible patients, 1292 were ultimately included in the analyses. The need for HCR occurred in 170/1292 patients (13%). The results showed a positive likelihood ratio of 3.74 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.20–4.36) and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.36 (95% CI: 0.29–0.46) for the human prediction and a positive likelihood ratio of 4.01 (95% CI: 3.43–4.70) and negative likelihood ratio of 0.35 (95% CI: 0.38–0.44) for the machine learning prediction. The combined use of human and machine learning prediction yielded a sensitivity of 83% (95% CI: 77–88%) and a specificity of 73% (95% CI: 70–75%). The Cohen's kappa coefficient showed an agreement of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.48–0.55).

Interpretation

The prospective ShockMatrix temporal validation study suggests a comparable human and machine learning performance to predict the need for HCR using real-life and real-time information with a moderate level of agreement between the two. Machine learning enhanced decision awareness could potentially improve the detection of patients in need of HCR if used by clinicians.

Funding

The study received no funding.

Keywords: Decision support, Machine learning, Human decision making, Trauma, Hemorrhage, Prediction, Performance

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Numerous retrospective studies developed machine learning algorithms to predict outcomes such as need for emergency surgery or blood transfusion in trauma with varying performance between AUC of 0.7 and 0.9; yet prospective validation studies with real patient data are inexistant and available studies have a high risk of bias. The performance of machine learning algorithms in a prospective study using real-life and real-time patient information compared to experienced clinicians is unknown. (Search sources: PubMed, Clinical Trial; search terms: human, trauma, shock prediction, machine learning, prospective validation; search date: 01/01/2000–31/12/2024).

Added value of this study

This prospective, observational study performed a temporal validation, comparing machine learning to human experts in a real-life setting using real-time information. The results demonstrated a comparable performance of a machine learning algorithm and experienced human trauma clinicians to predict the need for hemorrhage control resuscitation, with a moderate level of agreement between the two methods, and confirmed the feasibility to use machine learning decision tools.

Implications of all the available evidence

The combination of human clinician prediction with a machine learning algorithm could potentially enhance decision awareness and eventually improve the identification of trauma patients in need of hemorrhage control resuscitation.

Introduction

Timely identification of the need for hemorrhage control resuscitation (HCR) in trauma patients remains a significant challenge.1, 2, 3 Inconsistent recognition delays the administration of blood products4 and hemorrhage control procedures,5 thereby reducing survival chances. Similarly, inconsistent decision-making contributes to deviations from evidence-based guidelines, ultimately compromising care quality and patient outcomes.6,7

Clinical scores8,9 and flowcharts10,11 are often perceived as easy to use and memorize, requiring only a few data points. However, they demonstrate variable predictive performance and limited integration into daily clinical practice—likely because most were designed to predict massive transfusion rather than broader hemorrhage control needs. Machine learning algorithms offer a promising alternative, enabling automated, reliable, user-friendly, and real-time decision support, with the additional advantage of handling missing data through imputation.

Numerous models have been proposed to predict hemorrhage, transfusion needs, or surgical intervention.12,13 However, most of these models are developed using retrospective datasets, with only a few undergoing external validation, and even fewer advancing to prospective, real-life validation or clinical workflow integration.14,15 The recently published DECIDE-AI guidelines highlight this gap, emphasizing the need to study human-machine interactions and the integration of decision-support tools into clinical workflows.16, 17, 18

To address this gap, a machine learning algorithm capable of predicting the need for HCR based on routine prehospital variables, along with a dedicated smartphone application, was developed and evaluated in the preceding ShockMatrix pilot study.19

Building on these results, the prospective, multicentre observational ShockMatrix study pursued the objective to compare the predictive performance of the machine learning algorithm with that of clinicians in identifying the need for HCR. Conducted in the context of acute trauma care—where diagnostic uncertainty is high—the study sought to capture real-time, real-world clinical decisions and incorporate them into a dedicated machine learning algorithm. The primary hypothesis was that human and machine learning predictions would demonstrate comparable performance in predicting HCR requirements, within the framework of a diagnostic accuracy study, following the STARD 201520 and DECIDE-AI21 guidelines.

Methods

Setting

This prospective observational study was conducted across eight level-1 trauma centers in France (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT06270615); a level-1 center corresponds to the highest level of care provided to trauma patients with the capacity to treat any kind of injury pattern. Ethics approval was obtained from the University Paris Nord Ethics Committee (CER-2021-106, project SHOCKMATRIX, dated February 11, 2022), which also waived the requirement for informed consent.

The study was conducted by the Traumabase Group (traumabase.eu) within a previously described research context.16, 17, 18 The registry received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (Comité de Protection des Personnes, Paris VI), the Advisory Committee for Information Processing in Health Research (CCTIRS, 11.305bis), and the National Data Protection Agency (CNIL, ID 911461). Race and gender are currently not recorded in the Traumabase Registry.

Patient inclusion

Patients were included if the prehospital dispatch physician triggered a trauma team activation protocol according to national recommendations based on three-tier activation criteria (levels A, B, and C), and only for primary admissions (see Supplementary Material).22

Human participants

Human participants included all consultant- and fellow-level trauma clinicians working at one of the participating trauma centers. All were board-certified anesthesiologist-intensivists with specialized training in trauma care. Participants were instructed to use the smartphone application during each pre-alert call and to rely solely on the information spontaneously provided by the dispatcher. Clinicians had access to all dispatcher-provided information but were blinded to the machine learning model's prediction results. Clinical management decisions were left to the discretion of the attending physician, based on national guidelines.11 Transfusion thresholds and ratios were documented and compared to account for inter-center variability.

Smartphone-based data collection, storage, and processing

The smartphone application was developed by professional software engineers at Capgemini Invent (Issy-les-Moulineaux, Paris, France) and was made freely available to participating clinicians through the Apple App Store and Google Play Store. Access was granted via personal login credentials. Training sessions and manuals were provided. Usability and feasibility were assessed during a three-month pilot study in 2022 across five participating centers.19

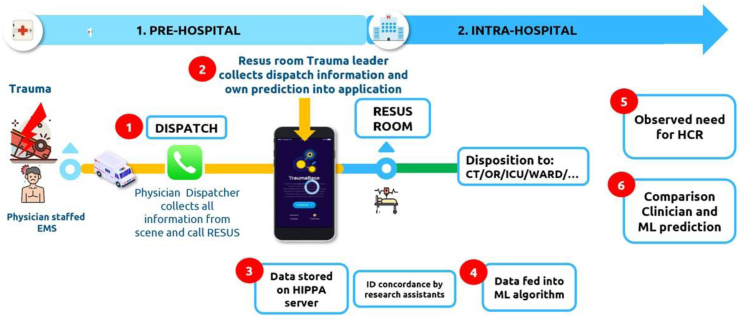

The app was designed to minimally disrupt workflow and allowed data collection in under 2 min. Upon receiving a prealert call, trauma clinicians in the resuscitation room entered nine predictor variables into the app, with the option to mark any variable as unknown. They then provided a subjective prediction of the need for HCR, expressed as a percentage (0% = very unlikely, 100% = very likely). These predictors matched those used in the machine learning model. A timestamp ensured all predictions were recorded before patient admission; any post-admission entries were excluded. Fig. 1 illustrates the study workflow.

Fig. 1.

Study workflow. CT: Computer Tomogram; EMS: emergency medicine system; RESUS: resuscitation room; HIPAA: Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; HCR: Hemorrhage control resuscitation; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; OR: Operating Room.

Data protection

Deidentified data were securely stored on a HIPAA-compliant Microsoft Azure server (Microsoft Corporation, Paris, France; commercial service, no conflict of interest). Each case received a unique identifier, which was used by trained research assistants to verify the clinical course and the objective need for HCR within the Traumabase registry. Both clinicians and research assistants were blinded to the machine learning model predictions.

Machine learning model development

The model was initially developed using data from 28,614 patients in the Traumabase registry as part of the previous ShockMatrix Pilot study.19 Detailed methodology is available in the Supplementary Material.

The model aimed to predict the need for HCR, defined as a composite outcome consisting of any of the following criteria11: a) administration of at least one packed red blood cell (RBC) in the resuscitation room,23 b) transfusion of four or more RBCs within 6 h of admission,24 c) requirement for a hemorrhage control procedure (interventional radiology or surgery) within 6 h,25 d) death from haemorrhagic shock within 24 h. These events were independently collected by blinded research assistants.

Predictors were limited to prehospital variables available during routine dispatch calls. Candidate predictors were evaluated using Shapley values,26 and the final nine selected variables were: type of trauma (blunt or penetrating), minimum diastolic and systolic blood pressures, maximum heart rate, capillary hemoglobin concentration, volume of crystalloid fluid given, intubation status, catecholamine use, and the presence of clinically obvious pelvic trauma. The strongest predictors were systolic blood pressure, capillary hemoglobin, fluid volume, and heart rate.

The dataset was split into training (50%), validation (20%), and test (30%) sets. Missing values in continuous variables were imputed using the mean, and a missing-data mask was concatenated with all predictors.27 Four tree-based algorithms (CART, Random Forest, XGBoost, CatBoost) were compared, with XGBoost selected based on superior F4-score performance in 10-fold cross-validation. The F4 metric evaluates the performance of a classification model, when the classes are imbalanced combining precision and recall (=sensibility); F4 score gives much more importance to recall than precision (see Supplementary Material).

The validation set was used to determine optimal thresholds and hyperparameters. The final model was evaluated on the test set using metrics including sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, precision, recall, AUC-PR, AUC-ROC, likelihood ratios (positive and negative), and the F4-score (to emphasize minimization of false negatives). A sample size of 1000 patients was calculated using 2000 bootstrap iterations to ensure the lower confidence interval margin of the F4-score was below the human reference F4 of 0.63.

A decision threshold of 0.11 was established by a panel of 20 expert clinicians from the Traumabase network.28,29 All model development was performed in Python 3.11.0.

Sample size calculation

The study was powered to compare the diagnostic accuracy of machine learning prediction to that of trauma clinicians. The true HCR outcome served as the gold standard. Based on a 13% prevalence and an expected sensitivity of 83% (from pilot data), a total sample size of 1158 cases was needed to achieve a 95% confidence interval with a 6% margin of error.19,30, 31, 32

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted by a professional data scientist (CC), under the supervision of a clinical researcher (TG), a professor of data science (JJ), and a data science director (SM). Analyses were performed using Python 3.11.0. Continuous variables are presented as medians (Q1–Q3) and categorical variables as counts (percentages). Missing data were handled as described above.

Machine learning and clinician predictions were compared using sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, accuracy, precision, F4-score, and positive and negative likelihood ratios (a positive likelihood ratio >10 = strong evidence to rule in; a negative likelihood ratio <0.1 = strong evidence to rule out). To simulate a combined approach, any positive HCR prediction from either machine learning or the clinician was considered a positive result—this approach aimed to maximize sensitivity. Sensitivities were compared using a Z-test with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Net clinical benefit was calculated for each modality (human, machine learning, combined) using decision-curve analysis with a decision threshold of 11%. Cohen's Kappa coefficient (with 95% CI) was used to assess agreement between machine learning and human predictions.

Role of the funding source

The study received no funding.

Results

Between August 1, 2022 and June 30, 2024, 1584 out of 5550 eligible patients were included, with 1292 analyzed. A total of 205 cases could not be matched between the smartphone app and clinical records, and 87 were excluded (see flowchart, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Study flowchart. HCR: Hemorrhage control resuscitation.

Most patients were male with a median age of 35 years (IQR 25–51) and an ISS of 10 (IQR 4–20). The need for HCR occurred in 170 of 1292 patients (13%). A total of 80 out of 104 eligible trauma clinicians (76%) contributed at least one case. Median prehospital time was 72 min (IQR 52–93). Transfusion thresholds and plasma-to-RBC ratios were consistent across centers. Table 1 presents detailed predictor availability at the time of prediction.

Table 1.

Study sample clinical characteristics.

| Cohort n = 1292 | Missing values n (%) | Need for hemorrhage resuscitation n = 170 | No need for hemorrhage resuscitation n = 1122 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | ||||

| Age, median [Q1–Q3] | 35 [26–51] | 73 (5.65%) | 39 [25–57] | 35 [26–50] |

| Male, n (%) | 1021 (79.0%) | 0 (0%) | 132 (77.6%) | 889 (79.2%) |

| Injury severity scale, median [Q1–Q3] | 10 [4–20] | 176 (13.6%) | 24 [15–33.5] | 9 [4–17] |

| Prehospital glasgow coma scale, median [Q1–Q3] | 15 [14–15] | 151 (11.6%) | 14 [7–15] | 15 [14–15] |

| Rate of critical care admission, n (%) | 1007 (77.9%) | 0 (0%) | 136 (80%) | 871 (77.63%) |

| Prehospital | ||||

| Total prehospital time, median [Q1–Q3] (=time medical team on scene to hospital admission) | 72 [52–93] | 520 (40%) | 75 [55–99] | 72 [55–92] |

| Prehospital, median minimum SBP [Q1–Q3] | 120 [110–140] | 110 (8.5%) | 100 [80–120] | 125 [110–140] |

| Prehospital, median minimum DBP [Q1–Q3] | 75 [60–80] | 242 (18.7%) | 60 [45–75] | 75 [65–85] |

| Prehospital, median maximum HR [Q1–Q3] | 90 [80–110] | 149 (11.5%) | 110 [85–120] | 90 [80–105] |

| Prehospital, median capillary hemoglobin [Q1–Q3] | 13.5 [12–15] | 261 (20.2%) | 12 [10–13.5] | 14 [12.5–15] |

| Prehospital, median crystalloid fluid expansion volume [Q1–Q3] | 450 [0–500] | 183 (14.1%) | 500 [450–1000] | 400 [0–500] |

| Prehospital crystalloid fluid expansion, n (%) | 366 (69.4%) | 765 (59.2%) | 64 (88.8%) | 302 (66.3%) |

| Prehospital intubation, n (%) | 215 (16.8%) | 15 (1.1%) | 65 (39.1%) | 150 (13.5%) |

| Prehospital catecholamine use, n (%) | 87 (7.02%) | 52 (4.0%) | 55 (34.5%) | 32 (2.9%) |

| Prehospital suspected pelvic trauma, n (%) | 199 (15.9%) | 41 (3.1%) | 35 (21.7%) | 164 (15.0%) |

| Prehospital suspected penetrating trauma, n (%) | 265 (20.6%) | 8 (0.6%) | 46 (27.2%) | 219 (19.6%) |

| Output and hospital | n = 1160 | n = 156 | n = 1004 | |

| Hemoglobin concentration on admission, median [Q1–Q3] | 12.5 [10–13] | 48 (3.6%) | 10 [10–11.2] | 11 [10–13] |

| Plasma to red cell concentrate ratio, median | NA | 41 (3%) | 1:2 | NA |

| Number of packed RBC transfused in resuscitation room [Q1–Q3] | 0 [0–0] | 10 (0.86) | 2 [0–3] | 0 [0–0] |

| Median number of packed RBC transfused within 6 h [Q1–Q3] | 0 [0–0] | 40 (3.45%) | 3 [2–6] | 0 [0–0] |

| Rate of surgical or radiological hemorrhage control procedure, n (%) | 128 (11.0%) | 499 (43.0%) | 127 (81.4%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Median duration before procedure in minutes [Q1–Q3] | 225 [140–410] | 557 (48.0%) | 156.5 [111.25–232.25] | 245 [155–482] |

| In hospital mortality, n (%) | 72 (6.2%) | 63 (5.4%) | 39 (25%) | 33 (3.2%) |

| Death from hemorrhagic shock during hospital stay, n (%) | 64 (5.5%) | 68 (5.8%) | 35 (22.4%) | 29 (2.8%) |

| Median duration of hospitalization in days [Q1–Q3] | 6.5 [2–16] | 194 (16.7%) | 15 [3–39] | 6 [2–13] |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; RBC: red blood cell concentrate; Q: quartile.

Table 2, Table 3 illustrate the confusion matrices for the trauma team clinician and machine learning prediction (XGBoost). The trauma clinician predictions for the need for HCR yielded a positive likelihood ratio of 3.74 (95% CI: 3.20–4.36) and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.36 (95% CI: 0.29–0.46). The machine learning algorithm showed a positive likelihood ratio of 4.01 (95% CI: 3.43–4.70) and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.35 (95% CI: 0.33–0.44).

Table 2.

Confusion matrix for human clinician prediction.

| Confusion matrix | Prediction human clinician |

|

|---|---|---|

| Need HCR+ | Need HCR− | |

| Observed | ||

| Need HCR+ | 120 | 50 |

| Need HCR− | 212 | 910 |

HCR: Hemorrhage Control Resuscitation.

Table 3.

Confusion matrix for machine learning prediction (XGBoost).

| Confusion matrix | Prediction XGBoost |

|

|---|---|---|

| Need HCR+ | Need HCR− | |

| Observed | ||

| Need HCR+ | 121 | 49 |

| Need HCR− | 199 | 923 |

HCR: Hemorrhage Control Resuscitation.

For the trauma clinicians, this corresponded to a sensitivity of 71% (95% CI: 62–78%), a specificity of 81% (95% CI: 78–84%), a precision of 36% (95% CI: 30–43%), and an accuracy of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.77–0.82). For the machine learning model, sensitivity was 71% (95% CI: 63–80%), specificity 82% (95% CI: 80–85%), precision 38% (95% CI: 31–75%), and accuracy 0.81 (95% CI: 0.78–0.83). The difference in sensitivity between the two methods was not statistically significant (Z-test, p = 1, 95% CI).

The F4-score was 0.64 (95% CI: 0.59–0.74) for trauma clinicians and 0.68 (95% CI: 0.60–0.75) for the machine learning model. The machine learning model's performance in this study was consistent with results from the validation cohort in the pilot study (see Supplementary Material).

The net clinical benefit was calculated as 0.07 for both the trauma clinicians and the machine learning model.

When the predictions of both the clinician and machine learning model were combined—such that a positive prediction from either source was treated as positive—the sensitivity increased to 83% (95% CI: 77–88%) and specificity was 73% (95% CI: 70–75%). This combined approach yielded a likelihood ratio+ of 3.02 (95% CI: 2.72–3.44) and a likelihood ratio− of 0.23 (95% CI: 0.17–0.33). The net clinical benefit for the combined method was 0.08.

In practical terms, in a sample of 100 patients, this equates to 8 patients correctly identified without harm using the combined method, compared to 7 patients identified by either the trauma clinician or the machine learning model alone.

Table 4, Table 5 summarize the performance metrics of the trauma clinician predictions, the machine learning model (XGBoost), and the hypothetical combined approach.

Table 4.

Confusion matrix for the hypothetical combined use of human trauma team clinician and machine learning prediction (XGBoost).

| Confusion matrix | Combined use human trauma clinician and XGBoost |

|

|---|---|---|

| Need HCR+ | Need HCR− | |

| Observed | ||

| Need HCR+ | 141 | 29 |

| Need HCR− | 304 | 818 |

HCR: Hemorrhage Control Resuscitation.

Table 5.

Summary of performance metrics human clinician, machine learning (XGBoost) and hypothetical combined use.

| F4 | Sensitivity | Precision | Specificity | Accuracy | AUC ROC | AUC PR | Pos LR | Neg LR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human clinician [95% CI] | 0.64 [0.59–0.74] | 0.71 [0.62–0.78] | 0.36 [0.30–0.43] | 0.81 [0.78–0.84] | 0.80 [0.77–0.82] | 0.76 [0.71–0.80] | 0.29 [0.24–0.35] | 3.74 [3.20–4.36] | 0.36 [0.29–0.46] |

| XGBoost model [95% CI] | 0.68 [0.60–0.75] | 0.71 [0.63–0.80] | 0.38 [0.31–0.44] | 0.82 [0.80–0.85] | 0.81 [0.78–0.83] | 0.83 [0.79–0.88] | 0.53 [0.44–0.63] | 4.01 [3.43–4.7] | 0.35 [0.33–0.44] |

| Hypothetical combined use human clinician and XGBoost [95% CI] | 0.76 [0.69–0.82] | 0.83 [0.77–0.88] | 0.31 [0.30–0.43] | 0.73 [0.70–0.75] | 0.74 [0.71–0.77] | 0.78 [0.74–0.81] | 0.29 [0.23–0.34] | 3.02 [2.72–3.44] | 0.23 [0.17–0.33] |

Human trauma clinician and machine learning model predictions did not produce identical false negative cases. Specifically, the trauma clinician predictions generated 21 false negatives that were correctly identified by the XGBoost model, while the model missed 20 cases that were detected by trauma clinicians. Table 6 lists the predictor variables and their distribution among false negative patients for both prediction sources.

Table 6.

Distribution of predictors among false negative cases for the human and machine learning prediction.

| Prédicteurs | False negative clinician (N = 50) |

False negative XGBoost (N = 49) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Missing | Distribution | Missing | |

| Median age | 48.0 (25.5–62.0) | 2 (4.0%) | 35.0 (23.5–58.0) | 2 (4.08%) |

| Median minimal SBP (mmHg) | 120.0 (105.0–140.0) | 6 (12.0%) | 120.0 (110.0–140.0) | 4 (8.16%) |

| Median minimal DBP (mmHg) | 70.0 (60.0–81.25) | 6 (12.0%) | 70.0 (60.0–82.5) | 6 (12.24%) |

| Median maximum HR (b/min) | 102.5 (85.0–110.0) | 6 (12.0%) | 95.0 (82.5–105.0) | 6 (12.24%) |

| Median cap hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.0 (11.75–14.0) | 11 (22.0%) | 14.0 (13.0–14.5) | 15 (30.61%) |

| Median fluid expansion (ml) | 500.0 (300.0–500.0) | 25 (50.0%) | 475.0 (250.0–500.0) | 27 (55.1%) |

| Sex (M) (N) | 35 (70.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 40 (81.63%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Clinical pelvic fracture (N) | 4 (8.16%) | 1 (2.0%) | 3 (6.52%) | 3 (6.12%) |

| Intubation yes (N) | 16 (32.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (23.4%) | 2 (4.08%) |

| Catecholamines (N) | 6 (12.24%) | 1 (2.0%) | 18 (81.82%) | 27 (55.1%) |

| Penetrating trauma (N) | 21 (84.0%) | 25 (50.0%) | 14 (28.57%) | 0 (0.0%) |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; RBC: red blood cell concentrate.

In cases of false negative predictions, the trauma clinicians and the machine learning model diverged most notably on the variables “catecholamine use” and “penetrating trauma”. Among the 50 false negatives from trauma clinician predictions, catecholamine use was present in 12.4% (6/50), whereas it was present in 81.2% (18/49) of the model's 49 false negatives. Conversely, penetrating trauma occurred in 84% (21/50) of the clinician-derived false negatives, compared to 28% (14/49) of the machine learning model's false negatives (see Table 6).

In terms of clinician experience, both very inexperienced clinicians (<3 years of practice) and very experienced clinicians (>9 years) had higher false negative rates (38% and 34%, respectively) compared to those with intermediate experience (3–9 years). No significant associations were found with day vs. night shifts or weekday vs. weekend shifts. There was no observable variation in results across the participating centers.

Agreement between human and machine learning predictions was moderate, with a Cohen's kappa coefficient of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.48–0.55). No malfunctions or technical issues were reported with the smartphone application, and there were no observed impacts on patient care or harm resulting from its use.

Discussion

The prospective, multicenter ShockMatrix study demonstrated that a machine learning model using only nine routine prehospital predictors performed comparably to experienced trauma clinicians in predicting the need for hemorrhage control resuscitation (HCR). The moderate agreement between predictions from clinicians and the machine learning model suggests the potential benefit of combining both approaches for enhanced decision awareness.

This study addresses a significant knowledge gap by providing a temporal, prospective validation of a machine learning model with real-time data available to clinicians and comparing its predictions to those made by human experts. Furthermore, it is one of the few multicentre benchmark studies assessing human decision-making in this context. Data collection was efficient and minimally disruptive via a user-friendly smartphone application.19 The model generated actionable outputs, aiding the preparation of blood products and hemorrhage control procedures. Notably, recent trials such as CRYOSTAT-2 have identified significant delays in administering blood products.33 Decision-support tools like this may expedite preparation and reduce those delays.

By improving decision awareness, machine learning tools can reduce clinician cognitive load, enhance reproducibility, and support guideline adherence, ultimately improving patient safety and care quality.34

The ShockMatrix study also provides a rare benchmark for human performance in predicting HCR. Human and machine learning performance slightly exceeded that of traditional clinical scores. For instance, a single-center retrospective studies showed the Shock Index and ABC score achieving likelihood ratio+ values of 3.6–4.2.9 respectively.8 A meta-analysis reported global positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio values for the Shock Index of 4.2 and 0.39.35 While easier to implement, such scores often rely on outdated cohorts and are limited to predicting massive transfusion—a less common outcome today—and typically ignore current guidelines.

Machine learning models can handle continuous variables and improve upon the binary thresholds used in traditional scores.36 Many existing machine learning models predict mortality or transfusion, but few focus on actionable patient needs like HCR, and even fewer have undergone external validation or real-life testing.12,13

The ShockMatrix model (AUC 0.89) performs comparably to others. For example, Maurer et al. used the NTDB to build a model predicting mortality (AUROC 0.92 for penetrating, 0.83 for blunt trauma) using comprehensive clinical variables.37 However, it requires data like AIS scores, typically unavailable in early care. Other models, like those by Lee, Nederpelt, and Follin, offer strong retrospective performance but depend on injury data not available prehospital.38, 39, 40 Liu et al. developed a model using heart rate variability to predict life-saving interventions (AUROC 0.7–0.9),41 but its use is limited by the current lack of this feature in commercial monitors. Perkins et al. proposed a Bayesian network model for coagulopathy prediction, but it also relies heavily on in-hospital data.42 These models rival established tools like viscoelastic testing: for example, FIBTEM A5 yields likelihood ratio+ of 2.91 and likelihood ratio− of 0.39 for hypofibrinogenemia detection, with AUC 0.75.43

The comparable performance of trauma clinicians and the algorithm supports the idea that machine learning does not need to outperform humans to be useful. Their moderate agreement and complementary errors suggest that combined use may improve overall decision-making. A prospective trial where clinicians are aware of machine learning predictions is needed to assess this integration in practice.

Future research should explore how decision-support tools affect clinical workflows, guideline adherence, resource use, and alarm fatigue. Building on ShockMatrix, a randomized cluster trial will launch in 2025 in 16 dispatch centers across France, using three machine learning algorithms to predict needs for HCR, neurosurgical intervention and intracranial pressure monitoring,44 and other trauma centre-specific treatments. The shock algorithm will be retrained for increased sensitivity. The study will include a cost-effectiveness analysis, crucial given the resource demands of developing and updating machine learning tools compared to simpler scoring systems.

With regard to limitations of the study, first while prospective, the study remains observational and does not measure impact on clinical outcomes. Ethical constraints required that machine learning performance be evaluated independently before full integration. Second, clinicians were not mandated to use the app, introducing potential selection bias. However, the final sample matched the derivation cohort in demographics and HCR incidence (13%). Third, asking clinicians to enter predictor data may have influenced their predictions. Fourth, the model used only prehospital data to maximize usability, but richer data (e.g., heart rate variability) might enhance performance at the cost of increased complexity and workflow disruption.41 Fifth, some predictors—like capillary hemoglobin and vasopressor use—are specific to the French system. Validation in other trauma systems is needed. Finally, moderate agreement between machine learning and clinicians suggests that additional human factors influence decision-making. These require further study.

Conclusion

The ShockMatrix pilot study bridges the gap between model development and real-world integration by comparing machine learning and human predictions for HCR in a real-time, high-uncertainty setting. The algorithm matched human performance and showed moderate agreement, indicating potential as a decision-support tool. A follow-up randomized cluster trial across 16 French dispatch centers is planned for 2025.

Contributors

Idea, design, data acquisition, analysis, writing of manuscript: TG.

Design, conception, data analysis, methodological supervision, writing of manuscript: JJ, JPN, AV, SM.

Data analysis, model construction, writing of manuscript: JJ, CC, SM.

Design, data acquisition, analysis, critical review: AJ, ND, MH, BB, MW, AM, VR, EC, HC, SS, JDM, PB, Traumabase Group.

Data sharing statement

All information and data and scripts are available upon request with the corresponding author. The script of the model is available on Github: https://github.com/tgauss-lab/Shockmatrix/tree/main.

Declaration of interests

TG reports honoraria from Laboratoire du Biomédicament Français and attending educational events organized by Octapharma; member of the scientific board Traumabase registry and French Society Anesthesia and Critical Care. Coordinator Traumatrix.fr Consortium. PB reports honoraria from Laboratoire du Biomédicament Français and is president of the National Trauma Committee (GITE). JDM received honoraria from Octapharma.

Acknowledgements

We thank all health care providers that contribute to the Traumabase registry. The data collection of the Traumabase registry is in part funded by several Regional Health Agencies (Agences régionales de Santé, ARS): ARS Île de France, ARS Occitanie, ARS Grand Est, ARS Hauts de France, ARS Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and by the French road safety observatory - Road Safety Delegation Service (Observatoire National Interministériel de la Sécurité Routière - Délégation à la Sécurité Routière). We thank the Regional Health Agencies and the French road safety observatory for their precious support for the data collection of the Traumabase registry. These entities did not contribute any funding to the study nor did they have any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. A special thanks to Dr. Pauline Perez for facilitating the first steps of the Traumatrix project.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2025.101340.

Contributor Information

Tobias Gauss, Email: tgauss@chu-grenoble.fr.

Traumabase Group:

Jeantrelle Caroline, Harrois Anatole, Raux Mathieu, Pasqueron Jean, Quesnel Christophe, Delhaye Nathalie, Godier Anne, Boutonnet Mathieu, Duranteau Olivier, Garrigue Delphine, Bourgeois Alexandre, Pottecher Julien, Tobias Gauss, Etienne Montalescaut, Eric Meaudre, Jean-Luc Hanouz, Valentin Lefrancois, Gérard Audibert, Marc Leone, Emmanuelle Hammad, Gary Duclos, Vincent Legros, Thierry Floch, Pauline Perez, Anne-Claire Lukaszewicz, François-Xavier Jean, Véronique Ramonda, Thomas Geeraerts, Fanny Bounes, Jean Baptiste Bouillon, Benjamin Brieu, Sébastien Gettes, Nouchan Mellati, Jean-Stéphane David, Youri Yordanov, Leslie Dussau, Elisabeth Gaertner, Benjamin Popoff, Thomas Clavier, Perrine Lepêtre, Marion Scotto, Julie Rotival, Loan Malec, Claire Jaillette, Romain Mermillod Blondin, Etienne Escudier, Samuel Gay, Pierre Gosset, Clément Collard, Jean Pujo, Hatem Kallel, Alexis Fremery, Nicolas Higel, Mathieu Willig, Benjamin Cohen, Paer Selim Abback, Jerome Morel, and Guillaume Bouhours

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Pelaccia T., Tardif J., Triby E., Charlin B. An analysis of clinical reasoning through a recent and comprehensive approach: the dual-process theory. Med Educ Online. 2011;16 doi: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durrands T.H., Murphy M., Wohlgemut J.M., De'Ath H.D., Perkins Z.B. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical examination for identification of life-threatening torsos injuries: a meta-analysis. Br J Surg. 2023;110:1885–1886. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znad285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wohlgemut J.M., Marsden M.E.R., Stoner R.S., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical examination to identify life- and limb-threatening injuries in trauma patients. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2023;31:18. doi: 10.1186/s13049-023-01083-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindsay C., Davenport R., Baksaas-Aasen K., et al. Correction of trauma-induced coagulopathy by goal-directed therapy: a secondary analysis of the ITACTIC trial. Anesthesiology. 2024;141:904–912. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000005183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke J.R., Trooskin S.Z., Doshi P.J., Greenwald L., Mode C.J. Time to laparotomy for intra-abdominal bleeding from trauma does affect survival for delays up to 90 minutes. J Trauma. 2002;52:420–425. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice T.W., Morris S., Tortella B.J., Wheeler A.P., Christensen M.C. Deviations from evidence-based clinical management guidelines increase mortality in critically injured trauma patients∗. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:778–786. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236f168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang E., Neuschwander A., Favé G., et al. Clinical decision support for severe trauma patients: machine learning based definition of a bundle of care for hemorrhagic shock and traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;92:135–143. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroll R., Swift D., Tatum D., et al. Accuracy of shock index versus ABC score to predict need for massive transfusion in trauma patients. Injury. 2018;49:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y.T., Bae B.K., Cho Y.M., et al. Reverse shock index multiplied by Glasgow coma scale as a predictor of massive transfusion in trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercer S.J., Kingston E.V., Jones C.P.L. The trauma call. BMJ. 2018;361 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gauss T., Quintard H., Bijok B., et al. Intrahospital trauma flowcharts - cognitive aids for intrahospital trauma management from the French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine and the French Society of Emergency Medicine. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2022;41 doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2022.101069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunter O.F., Perry F., Salehi M., et al. Science fiction or clinical reality: a review of the applications of artificial intelligence along the continuum of trauma care. World J Emerg Surg. 2023;18:16. doi: 10.1186/s13017-022-00469-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng H.T., Siddiqui M.M., Rhind S.G., Zhang J., Teodoro da Luz L., Beckett A. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for hemorrhagic trauma care. Mil Med Res. 2023;10:6. doi: 10.1186/s40779-023-00444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van de Sande D., van Genderen M.E., Huiskens J., Gommers D., van Bommel J. Moving from bytes to bedside: a systematic review on the use of artificial intelligence in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:750–760. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06446-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gauss T., Perkins Z., Tjardes T. Current knowledge and availability of machine learning across the spectrum of trauma science. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2023;29:713–721. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamada S.R., Gauss T., Duchateau F.X., et al. Evaluation of the performance of French physician-staffed emergency medical service in the triage of major trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1476–1483. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouzat P., Ageron F.X., Brun J., et al. A regional trauma system to optimize the pre-hospital triage of trauma patients. Crit Care. 2015;19:111. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0835-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gauss T., Ageron F.X., Devaud M.L., et al. Association of prehospital time to in-hospital trauma mortality in a physician-staffed emergency medicine system. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:1117–1124. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauss T., Moyer J.D., Colas C., et al. Pilot deployment of a machine-learning enhanced prediction of need for hemorrhage resuscitation after trauma - the ShockMatrix pilot study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2024;24:315. doi: 10.1186/s12911-024-02723-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J.F., Korevaar D.A., Altman D.G., et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasey B., Nagendran M., Campbell B., et al. Reporting guideline for the early-stage clinical evaluation of decision support systems driven by artificial intelligence: DECIDE-AI. Nat Med. 2022;28:924–933. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouzat P., GITE Network Standardizing categorization of major trauma patients in France: a position paper from the GITE Network. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2024;43 doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2024.101345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holcomb J.B., Tilley B.C., Baraniuk S., et al. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:471–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gauss T., Moyer J.D., Bouzat P. Massive transfusion in trauma: an evolving paradigm. Minerva Anestesiol. 2022;88:184–191. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.21.15914-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James A., Abback P.S., Pasquier P., et al. The conundrum of the definition of haemorrhagic shock: a pragmatic exploration based on a scoping review, experts' survey and a cohort analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:4639–4649. doi: 10.1007/s00068-022-01998-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundberg S.M., Erion G., Chen H., et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat Mach Intell. 2020;2:56–67. doi: 10.1038/s42256-019-0138-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josse J., Chen J.M., Prost N., et al. On the consistency of supervised learning with missing values. Stat Papers. 2024;65:5447–5479. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vickers A.J., Elkin E.B. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:565–574. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rousson V., Zumbrunn T. Decision curve analysis revisited: overall net benefit, relationships to ROC curve analysis, and application to case-control studies. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011;11:45. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-11-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachmann L.M., Puhan M.A., Riet G.T., Bossuyt P.M. Sample sizes of studies on diagnostic accuracy: literature survey. BMJ. 2006;332:1127–1129. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38793.637789.2F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajian-Tilaki K. Sample size estimation in diagnostic test studies of biomedical informatics. J Biomed Inform. 2014;48:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akoglu H. User's guide to sample size estimation in diagnostic accuracy studies. Turk J Emerg Med. 2022;22:177–185. doi: 10.4103/2452-2473.357348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davenport R., Curry N., Fox E.E., et al. Early and empirical high-dose cryoprecipitate for hemorrhage after traumatic injury: the CRYOSTAT-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330:1882–1891. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.21019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lefèbvre M., Balasoupramanien K., Galant J., et al. Effect of the implementation of a checklist in the prehospital management of a traumatised patient. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;72:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2023.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carsetti A., Antolini R., Casarotta E., et al. Shock index as predictor of massive transfusion and mortality in patients with trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2023;27:85. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04386-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Efthimiou O., Seo M., Chalkou K., Debray T., Egger M., Salanti G. Developing clinical prediction models: a step-by-step guide. BMJ. 2024;386 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-078276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maurer L.R., Bertsimas D., Bouardi H.T., et al. Trauma outcome predictor: an artificial intelligence interactive smartphone tool to predict outcomes in trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91:93–99. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee K.C., Lin T.C., Chiang H.F., et al. Predicting outcomes after trauma: prognostic model development based on admission features through machine learning. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000027753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nederpelt C.J., Mokhtari A.K., Alser O., et al. Development of a field artificial intelligence triage tool: confidence in the prediction of shock, transfusion, and definitive surgical therapy in patients with truncal gunshot wounds. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;90:1054–1060. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Follin A., Jacqmin S., Chhor V., et al. Tree-based algorithm for prehospital triage of polytrauma patients. Injury. 2016;47:1555–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu N.T., Holcomb J.B., Wade C.E., et al. Development and validation of a machine learning algorithm and hybrid system to predict the need for life-saving interventions in trauma patients. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2014;52:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s11517-013-1130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perkins Z.B., Yet B., Marsden M., et al. Early identification of trauma-induced coagulopathy: development and validation of a multivariable risk prediction model. Ann Surg. 2021;274:e1119–e1128. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baksaas-Aasen K., Van Dieren S., Balvers K., et al. Data-driven development of ROTEM and TEG algorithms for the management of trauma hemorrhage: a prospective observational multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2019;270:1178–1185. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moyer J.D., Lee P., Bernard C., et al. Machine learning-based prediction of emergency neurosurgery within 24 h after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. World J Emerg Surg. 2022;17:42. doi: 10.1186/s13017-022-00449-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.