Abstract

The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains causes severe problems in the treatment of microbial infections owing to limited treatment options. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are drawing considerable attention as promising antibiotic alternative candidates to combat MDR bacterial and fungal infections. Herein, we present a series of small amphiphilic membrane-active cyclic peptides composed, in part, of various nongenetically encoded hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids. Notably, lead cyclic peptides 3b and 4b showed broad-spectrum activity against drug-resistant Gram-positive (MIC = 1.5–6.2 μg/mL) and Gram-negative (MIC = 12.5–25 μg/mL) bacteria, and fungi (MIC = 3.1–12.5 μg/mL). Furthermore, lead peptides displayed substantial antibiofilm action comparable to standard antibiotics. Hemolysis (HC50 = 230 μg/mL) and cytotoxicity (>70% cell viability against four different mammalian cells at 100 μg/mL) assay results demonstrated the selective lethal action of 3b against microbes over mammalian cells. A calcein dye leakage experiment substantiated the membranolytic effect of 3b and 4b, which was further confirmed by scanning electron microscopy. The behavior of 3b and 4b in aqueous solution and interaction with phospholipid bilayers were assessed by employing nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in conjunction with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, providing a solid structural basis for understanding their membranolytic action. Moreover, 3b exhibited stability in human blood plasma (t1/2 = 13 h) and demonstrated no signs of resistance development against antibiotic-resistant S. aureus and E. coli. These findings underscore the potential of these newly designed amphiphilic cyclic peptides as promising anti-infective agentst, especially against Gram-positive bacteria.

Keywords: Antimicrobial Peptides, Antibiotics, Bacteria, Antifungal Peptides, Cyclic Peptides, Drug Resistance, Peptide-Membrane Interactions, Membranolytic, Molecular Dynamics, Molecular Hydrophobicity Potential

1. INTRODUCTION

The effectiveness of antimicrobials is regularly compromised due to the extraordinary resistance development ability of staphylococci and enterococci pathogens, especially Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) [1]. Therefore, this resistance poses a significant hurdle in treating infections caused by these pathogens with conventional antibiotics. The opportunistic human fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus is a primary cause of pulmonary aspergillosis, ranging from allergic syndromes and chronic infections to life-threatening invasive aspergillosis [2, 3]. The rise of multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria and fungi poses an imminent global health concern. In the United States, MDR pathogen infections impact over 2.8 million individuals annually, resulting in more than 35,000 deaths attributed to infection-related illnesses each year [4, 5]. The overreliance and improper use of antimicrobial drugs are key factors driving the emergence of drug-resistant pathogens [6]. Thus, it is crucial to devise novel treatment strategies that not only effectively combat drug-resistant pathogens but also mitigate the likelihood of the development of drug resistance.

Since the identification of the first antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in 1980’s, they have been regarded as the potential alternatives to the conventional antibiotics in addressing the clinical challenges posed by resistant pathogens [7]. AMPs, genetically encoded conserved molecules, form an essential part of the innate immune system in organisms spanning the phylogenetic spectrum. They function as a protective shield, aiding in the survival of these organisms on our planet [8, 9]. Over the course of evolution, AMPs have maintained their potency against rapidly mutating microorganisms, underscoring their pivotal role in the coevolutionary dynamics in the host-pathogen relationships [10]. While more than 1500 AMPs have been isolated from various sources, they share common biophysical characteristics such as cationicity and amphipathicity, allowing them to be categorized into three main structural classes: (1) α-helical; (2) β-sheet; and (3) extended structures rich in certain amino acids [7–9, 11]. Thus, it appears that a relatively a limited set of physicochemical features is required for AMPs to exert their antimicrobial effects.

Numerous studies on AMPs have suggested membrane disruption as their preferential mode of action. The cationic nature of AMPs is crucial for establishing an initial electrostatic interaction with the anionic surface of the bacterial membranes. Following the initial interaction, amphipathic peptides reorient themself in such a way that their hydrophobic side faces the lipid components of the membrane, while the hydrophilic side faces toward the phospholipid head-groups and water. Then they translocate through the membrane core, hey ultimately cause a reduction in membrane fluidity, resulting in cell death [12]. Contrary to conventional antibiotics which exert their antimicrobial action via targeting specific bacterial components, the apparently non-specific mode of action of AMPs gives them their unique therapeutic advantage, enabling them to be effective against a wide range to bacteria and fungi including drug resistant strains [6, 7, 9]. Over the past decade, academia and pharmaceutical industry have heavily invested resources in the design and development of AMP-inspired peptide-based antibiotics [13].

Many naturally occurring cyclic AMPs attain their constrained structural conformation through disulfide cross-links or backbone cyclization [14–16]. Macrocyclic molecules are a very attractive type of chemical class known to have distinctive features, such as a preorganized semi-rigid structure and high stability against peptidases. These attributes render them highly desirable not only against conventional therapeutic targets but also for contemporary drug discovery approaches such as protein-protein interactions and protein-nucleic acid interactions [17]. In addition, they offer a combination of therapeutic advantages found in both small molecules and larger biomolecules. Their low immunogenicity, high potency, selectivity, and reasonably low manufacturing costs attracted the attention of drug developers [18].

Interest in the development of macrocyclic peptide drugs stems from the discovery of the many biologically active naturally occurring antimicrobial macrocycles like vancomycin, daptomycin, gramicidin S, polymyxin B, and amphotericin B [19]. Gramicidin S, discovered in 1941, is a naturally produced cyclic-peptide based antibiotic, exhibiting antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positives and Gram-negative bacteria.[15] Despite its effectiveness, like many other promising AMPs, Gramicidin S is unsuitable for systemic use due to its hemolytic side-effects, and is thus limited to topical applications [20]. Moreover, naturally occurring as well as synthetic cyclic peptides are typically exceptionally stable against protease digestion [21]. The remarkable potency coupled with virtually minimal resistance to these established peptide antibiotics, has reignited interest in refining and/or extending their clinical applications.

Cyclic AMPs have demonstrated significant antimicrobial activities against various pathogenic bacteria, but often they present poor selectivity [20]. Thus, structure-activity relationship studies are crucial for improving their therapeutic profiles. Many studies have been conducted using native structure of the gramicidin S as a model template to create novel cyclic AMPs having improved safety profiles. The outcomes of these studies suggest that apart from conformational rigidity and amphipathicity, structural parameters such as ring size and a well-balanced combination of cationicity and hydrophobicity play a pivotal role in selectively targeting bacteria while sparing mammalian cells [20, 22].

Previously, we reported a series of short cationic cyclic amphiphilic peptides composed of unnatural amino acids (biphenylalanine (Bip), 3,3-diphenyl-L-alanine (Dip), and 3-(2-naphthyl)-L-alanine (Nal)). Among them, heptameric peptides composed of four cationic (arginine, Arg) and three hydrophobic (Dip/Nal) residues emerged as promising lead compounds [23]. In this study, we systematically modified both the cationic and hydrophobic segments to develop small cyclic peptides with improved antimicrobial activity and reduced cytotoxicity. Building upon the insights from our prior work, we selected hexameric and heptameric structural models for further optimization.

To achieve a balance between cationicity and hydrophobicity, we conducted positional scanning by substituting one or two unnatural amino acid residues at a time with tryptophan (Trp) residue. In addition, we also explored the impact of replacing the bulky aromatic side chain in unnatural amino acids Dip or Nal with a native aliphatic side chain of Leu. Furthermore, we delved into the role of Arg chain length by incorporating various Arg analogs ((S)-2-amino-3-guanidinopropionic acid (Agp), (S)-2-amino-4-guanidinobutyric acid (Agb), and homo-arginine ((S)-2-amino-6-guanidino-hexanoic acid (hArg)), in the polar domain of the peptide.

All synthesized peptides were examined for antibacterial and antifungal activities against a wide panel of antibiotic-resistant strains. The peptides’ cytotoxicity was assessed in vitro by measuring lytic activity against various types of normal mammalian cells, including human red blood cells (hRBC). The antibiofilm action and bactericidal kinetics of the lead peptides against bacteria and fungi was measured and compared with standard antibiotics. The proteolytic stability of lead cyclic peptide was determined in human blood plasma. Furthermore, the resistance development ability of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria was examined against lead cyclic peptide. Finally, we scrutinized the membrane perturbation action of the lead peptides through dye leakage assay and electron microscopy, followed by detailed NMR analysis to elucidate the membrane interactions at atomic level.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

2.1. Peptide design and synthesis

Previous investigations into both natural and synthetic AMPs have established that their ability to adopt a secondary structure with well-defined amphipathicity is critical for their antimicrobial activity and potential toxicity towards mammalian cells [24]. We also demonstrated that employing a constrained structural framework of the cyclic peptides with sequence-defined amphipathicity, could be a promising approach to in the development of peptide-based antibacterial agents [23]. Moreover, achieving a precise balance between cationic and hydrophobic residues is recognized for facilitating the effective integration of AMPs into bacterial cell membranes by establishing electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged phosphate groups of the membrane phospholipids [25]. Accordingly, in this study, we systematically altered parameters such as ring size, amphipathicity, and overall hydrophobicity and cationicity to assess their impact on activity against both microbial and eukaryotic membranes.

To this end, we designed a series of hexameric (1a-1c and 2a-2c) and heptameric (3a-3c, 4a-4c, 5a, 5b, 6a, 6b, and 7a-7c) amphiphilic peptides (Scheme 1), building upon our previously identified lead molecules c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Dip-Dip] (8a) and c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Nal-Nal] (8b) [23]. This structural amphipathicity was achieved by positioning positively charged and hydrophobic residues on opposite sides of the molecular framework. To fine tune the net hydrophobic bulk required for the antimicrobial activity and selectivity, we systematically replaced one or two unnatural hydrophobic residues with Trp, a native hydrophobic amino acid with a heteroaromatic side chain.

Scheme 1.

Overview of the various stages involved in the synthesis of macrocyclic peptides (1a to 7c) and the chemical structure of all the used hydrophobic and hydrophilic building blocks.

To pinpoint the most appropriate position of Trp in both hexameric (1a-1c and 2a-2c) and heptameric peptides (3a-3c, 4a-4c), we designed sequences by replacing one unnatural hydrophobic residue (Dip/Nal) at a time. We also created sequences (5a and 5b) where one unnatural hydrophobic residue (Dip/Nal) was flanked by Trp residues in the hydrophobic region. In addition, we also examined the impact of the substitution of an unnatural hydrophobic amino acid residue (Dip/Nal) with a native amino acid L-Leu having aliphatic side chain (6a and 6b). Given that electrostatic interaction between cationic residues and anionic bacterial membrane guides peptide molecules selectively toward bacterial membranes rather than zwitterionic mammalian membranes, we aimed to determine the optimum chain length required to establish effective interactions with bacterial membranes. To do so, we designed molecules using Arg analogs having shorter (7a and 7b) or longer (7c) chain lengths as compared to native Arg amino acid (Scheme 1).

All the peptide sequences were assembled on the resin by Fmoc/tBu solid-phase chemistry. A thorough cleavage process of the assembled peptides from the resin generated linear peptides. Through partial cleavage, cyclization in the presence of activating and coupling reagents, followed by complete deprotection, we afforded the cyclized peptides (Scheme 1). All the synthesized cyclic peptides were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and were found to be >95% pure. The HPLC purity of cyclic peptides (Figures S1–S19, Supporting Information) and mass data of all linear (Figures S20–S38) and cyclic peptides (Figures S39–S57) have been provided in the Supporting Information.

2.2. Antimicrobial evaluation

2.2.1. Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of all the synthesized cyclic peptides (1a-1c, 2a-2c, 3a-3c, 4a-4c, 5a-5b, 6a-6b, and 7a-7c) was examined against Gram-positive (S. aureus and MRSA) and Gram-negative (E. coli and P. aeruginosa) bacteria (Table 1). Hexameric peptides (1a-1c and 2a-2c) showed activity against Gram-positive bacteria with higher activity against S. aureus (MIC = 3.1–6.2 μg/mL), compared to its methicillin resistant strain (MIC = 6.2–12.5 μg/mL). However, a moderate active was observed against Gram-negative bacteria (MIC = 12.5–25 μg/mL). A similar pattern of activity was noted for heptameric peptides with higher activity was observed against Gram-positive bacteria as compared to Gram-negative bacteria. The hexameric peptides (1a-1c and 2a-2c) composed of equal number of cationic (Arg) and hydrophobic residues (Trp/Dip/Nal) residues, showed modest antibacterial potency in comparison to the heptameric peptides (3a-3c and 4a-4c) containing an additional Arg residue. Notably, with the exception of 4b, a higher activity was observed for peptides having Trp residue in the sixth (3b) or fifth (3a and 4a) position, compared to those with a Trp residue in the seventh position (3c and 4c) against MRSA.

Table 1.

Antibacterial and hemolytic activity of the cyclic peptidesa.

| Code | Peptides Sequenceb | MICc (μg/mL) | HC50 (μg/mL) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA (ATCC BAA-1556) |

S. aureus (ATCC 29213) |

P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27883) |

E. coli (ATCC 25922) |

|||

| 1a | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Dip-Dip] | 6.2 | 6.2 | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| 1b | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Trp-Dip] | 6.2 | 3.1 | 25 | 12.5 | 75 |

| 1c | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Dip-Trp] | 12.5 | 6.2 | 25 | 25 | 65 |

| 2a | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Nal-Nal] | 6.2 | 3.1 | 25 | 25 | 60 |

| 2b | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Trp-Nal] | 6.2 | 3.1 | 25 | 12.5 | 55 |

| 2c | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Nal-Trp] | 6.2 | 6.2 | 25 | 25 | 45 |

| 3a | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Dip-Dip] | 1.5 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 85 |

| 3b | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Trp-Dip] | 1.5 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 230 |

| 3c | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Dip-Trp] | 3.1 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 25 | 100 |

| 4a | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Nal-Nal] | 1.5 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 150 |

| 4b | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Trp-Nal] | 3.1 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 175 |

| 4c | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Nal-Trp] | 3.1 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 105 |

| 5a | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Dip-Trp] | 6.2 | 3.1 | 12.5 | 25 | 220 |

| 5b | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Nal-Trp] | 6.2 | 6.2 | 25 | 25 | 200 |

| 6a | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Leu-Dip] | 6.2 | 6.2 | 25 | 25 | 155 |

| 6b | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Leu-Nal] | 6.2 | 6.2 | 50 | 25 | 170 |

| 7a | c[Agp-Agp-Agp-Agp-Dip-Trp-Dip] | 6.2 | 3.1 | 25 | 25 | 240 |

| 7b | c[Agb-Agb-Agb-Agb-Dip-Trp-Dip] | 3.1 | 3.1 | 25 | 25 | 190 |

| 7c | c[hArg-Arg-hArg-Arg-Dip-Trp-Dip] | 3.1 | 3.1 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 160 |

| 8a e | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Dip-Dip] | 3.1 | 3.1 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 70 |

| 8b e | c[Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Nal-Nal] | 3.1 | 3.1 | 12.5 | 25 | 80 |

| Daptomycin | 1.5 | 0.7 | NDd | NDd | NDd | |

| Polymyxin B | NDd | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | >500 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 3.1 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | NDd | |

Results represent the highest MIC value obtained from three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

All amino acid residues are represented in three letter notations. Dip, 3,3-diphenyl-L-alanine; Nal, 3-(2-naphthyl)-L-alanine; Agp, (S)-2-amino-3-guanidinopropionic acid; Agb, (S)-2-amino-4-guanidinobutyric acid; hArg, homo-arginine (S)-2-amino-6-guanidino-hexanoic acid.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined as the lowest concentration of the peptides that inhibited bacteria growth.

HC50 is the concentrations in mg/mL of peptides at which 50% hemolysis was observed.

ND represents not determined.

Data from.[23]

Heptameric peptides containing two Trp and one Dip (5a) or Nal (5b) residue in the hydrophobic domain showed robust activity (MIC = 3.1–6.2 μg/mL) against Gram-positive bacteria and moderate activity (12.5–25 μg/mL) against Gram-negative bacteria. Peptides composed of a Leu residue flanked by Dip (6a) or Nal (6b) in the hydrophobic region displayed one-fold decrease in activity against both Gram-positive (MIC = 6.2 μg/mL) and Gram-negative (MIC = 25–50 μg/mL) bacteria.

It is well-established that the net cationicity of AMPs plays a pivotal role in their interaction with the negatively-charged bacterial membrane surfaces through electrostatic forces [12, 25]. Many previous studies, including our own, have demonstrated that increasing the net cationicity beyond a limit does not lead to a proportional increase in antibacterial activity [23, 26]. Therefore, we modified the polar domain of the lead peptide 3b while keeping the number of cationic residues the same but varying the chain length in order to identify the most appropriate chain length for establishing an effective electrostatic interaction with anionic surface of the target pathogen. Interestingly, peptides comprising unnatural Arg analogs with shorter side chain (7a and 7b) and longer side chain (7c) were found to be one to two-fold less active against all the tested bacterial strains as compared to 3b, which contains the natural Arg residue.

Additionally, linear analogs of all the cyclic peptides were tested, and the results indicated that cyclic peptides exhibited higher activity against all the tested bacterial strains (Table S3, Supporting Information).

2.2.2. Activity of the lead cyclic peptides against the extended spectrum of bacteria

Based on promising antibacterial activity of heptameric cyclic peptides (3a-3c and 4a-4c), we subjected them to screening against a clinically relevant multi-drug resistant ESKAPE panel of bacteria, including Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species. The results revealed a broad-spectrum activity with predominant effectiveness against Gram-positive bacteria (Table 2). With the exception of 4c, all tested cyclic peptides displayed antibacterial activity against E. faecium (ATCC 27270) and its vancomycin-resistant strain (ATCC 700221) with MIC values of 1.5 to 3.1 μg/mL. However, a slight reduction in activity was observed against E. faecalis (MIC = 3.1–12.5 μg/mL).

Table 2.

Broad-spectrum activity of the lead cyclic peptides.

| Bacterial Strains | MICh (μg/mL) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 3b | 3c | 4a | 4b | 4c | Daptomycin | Vancomycin | Ciprofloxacin | Polymyxin B | |

| Gram-Positive | ||||||||||

|

Enterococcus faecium

(ATCC 27270) |

3.1 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | NDi | NDi |

|

Enterococcus faeciuma (ATCC 700221) |

1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 6.25 | >50 | NDi | NDi |

|

Enterococcus faecalis

(ATCC 29212) |

6.2 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 6.25 | 0.7 | NDi | NDi |

|

Enterococcus faecalisa

(ATCC 51575) |

12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | >50 | NDi | NDi |

|

Staphylococcus pneumoniae (ATCC 49619) |

25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 12.5 | 3.1 | NDi | NDi |

|

Staphylococcus pneumoniaeb (ATCC 700677) |

12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 25 | 12.5 | 1.5 | NDi | NDi |

|

Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633) |

1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | NDi | NDi |

|

Bacillus cereus (ATCC 13061) |

6.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 0.7 | NDi | NDi |

|

Clostridium difficile (ATCC 700057) |

NDi | 12.5 | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi |

|

Clostridium difficilec (NAP1/027) |

NDi | 6.2 | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi | NDi |

| Gram-Negative | ||||||||||

|

Escherichia colid (ATCC BAA-2452) |

12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 12.5 | NDi | NDi | 0.7 | 0.7 |

|

Klebsiella pneumonia

(ATCC 13883) |

50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | NDi | NDi | 1.5 | 6.2 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC BAA-2470) | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 12.5 | 12.5 | NDi | NDi | 0.7 | 1.5 |

|

Acinetobacter baumanniif (ATCC BAA1605) |

12.5 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 25 | 25 | NDi | NDi | 0.7 | 0.7 |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 10145) |

25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 50 | NDi | NDi | 0.7 | 0.7 |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosag

(ATCC BAA-1744) |

12.5 | 12.5 | 25 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 25 | NDi | NDi | 0.7 | 0.7 |

Vancomycin resistant,

Multi-drug resistant (Penicillin, Tetracycline, and Erythromycin),

Reduced susceptibility to multiple antibiotics,

NDM-1,

Carbapenem resistant strain,

Ciprofloxacin resistant strain,

Imipenem resistant strain.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined as the lowest concentration of the peptides that inhibited bacteria growth.

ND represents not determined. The MIC values are the highest value obtained from three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Notably, all cyclic heptameric peptides (3a-3c and 4a-4c) demonstrated 2–3-fold higher activity against vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (ATCC 700221) when compared to daptomycin, a commercially available lipopeptide antibiotic. Interestingly, except for 4c, while moderate activity was observed against non-resistant S. pneumoniae (ATCC 49619, MIC = 25 μg/mL), a one-fold increase in activity was observed against MDR S. pneumoniae (ATCC 700677, MIC = 12.5 μg/mL), which is comparable to daptomycin. All tested peptides showed activity against B. subtilis and B. cereus with MIC values of 1.5 to 6.2 μg/mL. We assessed one of the lead peptides, 3b, against Clostridium difficile and notably observed a one-fold increase in activity against the MDR resistant strain (NAP1/027) that is known for its high resistance making it a formidable Gram-positive pathogen, compared to the non-resistant strain (ATCC 700057), with an MIC value of 6.2 μg/mL.

All tested cyclic peptides (3a-3c and 4a-4c) displayed moderate level of activity against Gram-negative bacterial strains. The peptides demonstrated activity against antibiotic resistant E. coli (ATCC BAA-2452) with MIC ranging from 6.2 to 12.5 μg/mL (Table 2), when compared to non-resistant E. coli (ATCC 25922, MIC = 12.5–25 μg/mL; Table 1). Although they displayed only moderate activity against non-resistant K. pneumonia (ATCC 13883, MIC = 50 μg/mL), they showed higher activity against carbapenem-resistant K. pneumonia (ATCC BAA-2470) with MIC ranging from 12.5 to 25 μg/mL (Table 2). The peptides exhibited activity against Acinetobacter baumannii (ATCC BAA1605) and P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27883, ATCC 10145, ATCC BAA-1744), with MIC values ranging from 6.2 to 25 μg/mL (Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, similar to Gram-positive bacteria, these peptides demonstrated mostly higher activity against antibiotic-resistant strains compared to non-resistant bacterial strains, as shown for K. pneumonia and P. aeruginosa (Table 2). Overall, activity results indicate that the tested cyclic peptides possess a broad-spectrum antibacterial potential, exerting mostly higher activity against antibiotic-resistant strains.

2.2.3. Antifungal Activity

Encouraged by the promising antibacterial performance of these selected heptameric peptides, we proceeded to evaluate their antifungal activity. The antifungal activity of the selected cyclic peptides (3a-3c and 4a-4c) was determined against A. fumigatus and candida strains, and the corresponding data is outlined in Table 3. These cyclic peptides exhibited antifungal activity against all the tested strains, with comparatively higher activity against candida strains. Against A. fumigatus, the cyclic peptides (3a-3c and 4a-4c) demonstrated antifungal effects, with MICs falling within the range of 6.2–12.5 μg/mL, while displayed slightly enhanced potency against all three candida strains, with MICs ranging from 1.5 to 6.2 μg/mL (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antifungal activity of the selected cyclic peptidesa.

| Peptide | MICb (μg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A. fumigatus (Af-293) |

C. albicans (ATCC 60193) |

C. albicans (ATCC 10132) |

C. krusii (ATCC 6258) |

|

| 3a | 6.2 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 1.5 |

| 3b | 6.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 1.5 |

| 3c | 12.5 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| 4a | 12.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 3.1 |

| 4b | 6.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| 4c | 6.2 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 1.5 |

| Fluconazole | NDc | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.7 | NDc | NDc | NDc |

Results represent the highest MIC value obtained from three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined as the lowest concentration of the peptides that inhibited fungi growth.

ND represents not determined.

2.2.4. Salt and serum sensitivity

Previous studies have revealed the detrimental impact of physiological salts on antimicrobial activity of AMPs [27]. The initial binding and subsequent antimicrobial activity of positively charged AMPs rely heavily on electrostatic interactions with negatively charged bacterial membranes [28]. Evidently, the abundance of competing physiological cations may hinder these vital electrostatic interactions between AMPs and target bacterial membranes which are pivotal for their activity.

To investigate the effect of the presence of cations on the antibacterial and antifungal potency of the lead cyclic peptides (3b, 4a, and 4b), MIC values were determined against bacteria (MRSA (ATCC BAA-1556) and E. coli (ATCC BAA-2452)) as well as fungi (A. fumigatus (Af-293) and C. albicans (ATCC 60193)) under various physiologically relevant salt conditions. The results indicated that, in most cases, the presence of monovalent cations (Na+, K+, and NH4+) as well as divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) had no effect in MICs or a negligible impact with a slightly higher increase in MICs (2–4-fold) on both bacterial and fungal strains (Table 4). It appears that the well-defined inherent amphiphilic constrained structure, coupled with the higher localized positive charge due to adjacent Arg residues, might have outweighed the counteractive effect of cations vying for membrane binding. Moreover, we assume that the preorganized amphiphilic structure of the cyclic peptides may have resulted in a lesser amount of entropy lost required to attain the target binding conformation. The antibacterial action of cyclic peptides in salt conditions underline their potential clinical application in treating infectious diseases that may disrupt normal salt homeostasis in certain human tissues [29].

Table 4.

Antibacterial and antifungal activities of lead peptides (3b, 4a, and 4b) and antibiotics in the presence of various cationic salts and FBSa.

| Peptide | MICb (μg/mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlc | NaCld | KCld | NH4Cld | MgCl2d | CaCl2d | FBSe

(25%) |

|

| MRSA (ATCC BAA-1556) | |||||||

| 3b | 1.5 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 3.1 |

| 4a | 1.5 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| 4b | 3.1 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| Daptomycin | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| E. coli (ATCC BAA-2452) | |||||||

| 3b | 12.5 | 25 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 25 |

| 4a | 12.5 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 12.5 | 12.5 | >50 |

| 4b | 12.5 | 50 | 25 | 25 | >50 | 25 | 50 |

| Polymyxin B | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| A. fumigatus (Af-293) | |||||||

| 3b | 6.2 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 12.5 |

| 4a | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| 4b | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 25 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| C. albicans (ATCC 60193) | |||||||

| 3b | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| 4a | 6.2 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 12.5 |

| 4b | 3.1 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| Fluconazole | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

Results of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined as the lowest concentration of the peptides that inhibited bacteria/fungi growth.

The Control represents the assay conducted in MH media without salt ions or serum.

The final concentrations of NaCl, KCl, NH4Cl, MgCl2, and CaCl2 were 150 mM, 4.5 mM, 6 mM, 1 mM, and 2 mM, respectively.

Antibacterial and antifungal activities were determined in the presence of fetal bovine serum (FBS).

In addition, we also determined the antimicrobial activity of lead cyclic peptides (3b, 4a, and 4b) and standard antibiotics in the presence of serum. Cyclic peptides 3b, 4a, and 4b maintained their antimicrobial potency against bacteria and fungi even in the presence of human serum (Table 4). While a slight increase in MICs was observed for cyclic peptides against MRSA, a comparatively more significant loss in activity was observed against E. coli (Table 4). Likewise, a small decrease in activity was observed for daptomycin and polymyxin B. However, conventional antibiotics ciprofloxacin, amphotericin B, and fluconazole maintained their consistent activity profiles against the tested bacterial and fungal strains.

2.2.5. Antibiofilm activity

Biofilm formation is an inherent feature of many microbial pathogens that cause life-threatening infections. These biofilms can be clusters of microorganisms or multicellular communities, which surround themselves within a self-produced matrix of secreted extracellular polymeric substances, typically composed of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and DNA [30]. Biofilms are considered as one of the potential protective mechanisms, which not only reduce the susceptibility pathogens to most antibiotics but also significantly contribute to the emergence of drug resistance [31]. In comparison to bacteria, fungal biofilms are highly associated with persistent nosocomial infections, most commonly typical in immunocompromised patients with prolonged exposure to medical devices such as catheters, cardiac pacemakers, and prosthetic heart valves [32]. Several clinically important species belonging to the genus Candida are the most common opportunistic pathogen, being endowed with a strong ability to switch from a yeast mode of growth to a hyphal morphology that is better suited for invading host tissues and forming biofilms on abiotic and biotic surfaces. This leads to increased resistance to existing antifungal agents [33]. Given the formidable clinical challenges posed by biofilm producing microbes, we examined the anti-biofilm potential of lead peptides (3b and 4b) against bacterial and fungal strains.

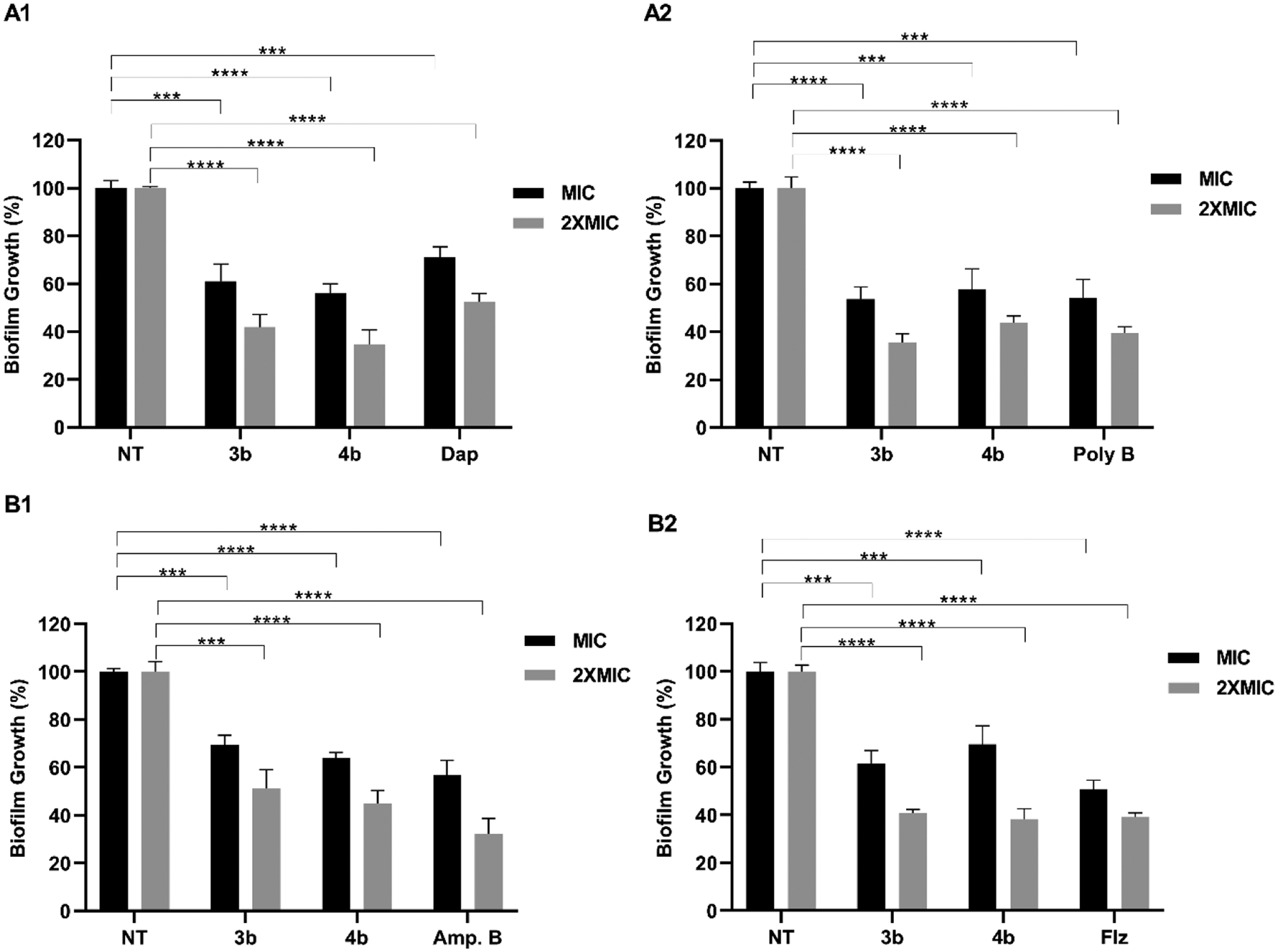

The antibiofilm potential of lead cyclic peptides (3b and 4b) against bacteria (MRSA (ATCC BAA-1556) and E. coli (ATCC BAA-2452)) and fungi (A. fumigatus (Af-293) and C. albicans (ATCC 60193)) was determined by conducting XTT assay. To determine antibiofilm activity, a percentage decrease in the biofilm burden at MIC and 2× the MIC of test peptides (3b and 4b) and standard antibiotics was calculated (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Antibiofilm activity of lead peptides (3b and 4b) against bacteria (MRSA (ATCC BAA-1556) (A1), E. coli (ATCC BAA-2452) (A2)) and fungi (A. fumigatus (Af-293) (B1), C. albicans (ATCC 60193) (B2)) at MIC and 2×MIC. NT corresponds to the negative control-untreated cells in PBS. Standard antibiotics daptomycin (Dap), polymyxin B (Poly B), amphotericin B (Amp B), and fluconazole (Flz) were used as a positive control against bacteria and fungi, respectively. The data obtained are from the experiments performed in triplicate. The data underwent analysis via a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (**p < 0.01, (***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns-not significant).

At MIC, lead cyclic peptides 3b and 4b displayed substantial antibiofilm activity against MRSA (Figure 1A1) and E. coli (Figure 1A2), resulting in approximately a 40–45% reduction in biofilm mass compared to untreated control cells. Notably, both 3b and 4b demonstrated even greater antibiofilm activity (60–65% decrease in biofilm mass) at 2× the MIC, indicating a concentration-dependent inhibition of biofilm formation. Interestingly, as compared to 3b and 4b, less antibiofilm activity was observed for daptomycin with around 29% and 48% decrease in biofilm mass of MRSA at MIC and 2× the MIC, respectively (Figure 1A1). In contrast, polymyxin B showed 46% (MIC) and 61% (2× the MIC) reduction in biofilm mass of E. coli, which were comparable to lead cyclic peptides (3b and 4b) (Figure 1A2).

Lead cyclic peptides 3b and 4b demonstrated a significant decrease in the biofilm mass of both A. fumigatus (Figure 1B1) and C. albicans (Figure 1B2). When compared to untreated cells, A. fumigatus treated with 3b and 4b at MIC and 2× the MIC resulted into 31–36% and 49–56% reduction in biofilm mass, respectively (Figure 1B1). Similarly, against C. albicans, both 3b and 4b induced 31–39% and 60–62% decrease in biofilm mass at MIC and 2× the MIC, respectively (Figure 1B2).

Notably, while antibiofilm action of 3b and 4b was comparable to that of amphotericin B against A. fumigatus, a slightly lower antibiofilm activity was observed compared to fluconazole against C. albicans. Overall, 3b and 4b exhibited remarkable antibiofilm activity against both bacteria and fungi, on par with standard antibiotics. Given the structural similarities between biofilm and bio-membranes, we assume the extraordinary membranolytic ability of cyclic peptides is responsible for their antibiofilm activity.

2.2.6. Kill-kinetic assay

As compared to the conventional antibiotics, AMPs are recognized for their swift microbial eradication capabilities. To examine the time-dependent antimicrobial action of the leading cyclic peptides 3b and 4b, the viability of exponentially growing bacterial (MRSA (ATCC BAA-1556) and E. coli (ATCC BAA-2452), Figures 2A1 and 2A2) and fungal (A. fumigatus (Af-293) and C. albicans (ATCC 60193), Figures 2B1 and 2B2) strains was evaluated using a kill-kinetic assay at 6 h and 12 h, respectively. Both 3b and 4b demonstrated a rapid bactericidal effect against MRSA, virtually eliminating all bacterial cells within 3–4 h at MIC, and within 1–2 h at 4× the MIC. Similarly, with only a slight reduction in rate of killing, both 3b and 4b completely halted the growth of nearly all E. coli cells after 4 h and 2 h of treatment at MIC and 4× the MIC, respectively. Notably, in comparison to peptide-based antibiotics daptomycin and polymyxin B, the kinetics of bactericidal action of 3b and 4b closely matched MIC for MRSA and E. coli. However, at a concentration level of 4× the MIC, they demonstrated superior efficacy (Figures 2A1 and A2).

Figure 2.

Time-dependent killing action of the lead macrocyclic peptides (3b and 4b) and standard antibiotics, daptomycin and polymyxin B, against bacteria (A1 (MRSA (ATCC BAA-1556)) and A2 (E. coli (ATCC BAA-2452)) and fungi (B1 (A. fumigatus (Af-293) and B2 (C. albicans) (ATCC 60193) at MIC and 4×MIC. The data obtained are from the experiments performed in triplicate.

Contrastingly, against the fungal strains (A. fumigatus and C. albicans), lead cyclic peptide 3b and 4b displayed comparatively less rapid action. Complete eradication was not achieved even after 12 h of treatment at MIC. However, at 4× the MIC, both 3b and 4b demonstrated near-complete eradication of fungal cells after 12 h. It is worth noting that, in comparison to lead cyclic peptides 3b and 4b, amphotericin B and fluconazole showed a mild fungicidal effect against A. fumigatus and C. albicans, respectively (Figures 2B1 and B2). Overall, the kill-kinetic study results underscored the rapid killing action of 3b and 4b against both bacteria and fungi.

2.3. Cytotoxicity

2.3.1. Hemolytic activity

The hemolytic activity of all synthesized cyclic peptides (1a-1c, 2a-2c, 3a-3c, 4a-4c, 5a, 5b, 6a, 6b, and 7a-7c) was assessed through a hemolytic assay using human red blood cells (hRBCs), with results quantified as HC50 (the peptide concentration required for 50% hemolysis; Table 1). Heptameric cyclic peptides (3a-3c and 4a-4c) were found to be less hemolytic in comparison to hexameric cyclic peptides (1a-1c and 2a-2c). This observed higher hemolytic activity of hexameric peptides compared to heptameric peptides reinforces a widely accepted phenomenon of a direct correlation between cationicity/hydrophobic bulk ratio and selectivity towards microbial membranes over mammalian membranes [23, 26, 34]. The higher ratio of hydrophobic content relative to cationicity increases the activity of hexameric peptides towards zwitterionic mammalian membranes. Conversely, the heptameric peptides having high cationicity/hydrophobic bulk ratio attributed to the presence of an additional Arg residue, appear to be more selective towards anionic microbial membranes.

Interestingly, while the heptameric peptides (3a-3c and 4a-4c) have somewhat similar antibacterial activity irrespective of the position of the Trp residue, there is a distinct variation in hemolytic activity (Table 1). Peptides with Trp residues at positions one (3c and 4c) and three (3a and 4a) showed higher hemolytic activity compared to peptides where the Trp residue was flanked by unnatural amino acid Dip (3b; HC50 = 230 μg/mL) and Nal (4b; HC50 = 175 μg/mL). Regarding these peptide series, we consider HC50 ≥ 175 μg/mL as the threshold for limited hemolysis. A comparable hemolytic activity was observed for peptides 5a and 5b containing two Trp residues and one Dip or Nal with HC50 values of 200 μg/mL and 220 μg/mL, respectively. It appears that the lower overall hydrophobicity of the heteroaromatic ring of Trp might disrupt the dominant hydrophobic moment generated by the adjacently placed bulky hydrophobic residues (Dip/Nal), thereby diminishing the hydrophobic interaction with mammalian membranes. The difference in hemolytic activity between the peptides 3a-3c with Dip is much pronounced than in peptides 4a-4c with Nal (Table 1). As verified by modeling results (see below), the bulky aromatic rings of Dip create a more expanded hydrophobic surface compared to Nal. Hence, the disruption of the expanded hydrophobic surface by the centrally-placed Trp side chain has a strong impact on the peptide’s hemolytic activity. A decrease in hydrophobic bulk in peptides containing two Trp and one Dip (5a) or Nal (5b) residues led to 2–4-fold decrease in their antibacterial activity, while maintaining a similar hemolytic activity compared to the lead peptides 3b and 4b (Table 1).

Peptides 6a and 6b, having Leu instead of Trp, showed high toxicity with HC50 values of 155 μg/mL and 170 μg/mL, respectively. While 6b displayed closely similar hemolytic activity to its analogous peptide 4b, a significant increase in hemolytic activity was observed for 6a compared to its analogous peptide 3b (Table 1). Among the peptides composed of Arg analogs (7a-7c), the highest toxicity was observed for peptide 7c (HC50 = 160 μg/mL) due to its long side chain, as compared to peptides composed of short side chain Arg analogs (7a and 7b) (Table 1). The antibacterial and hemolytic activity results indicate that the chain length of native Arg is optimum among the used synthetic analogs with both shorter (Agp and Agb) and longer (hArg) side chains.

Lead peptides 3b and 4b displayed a one-fold higher antibacterial activity and significantly lower toxicity compared to their previously reported heptameric peptide prototypes 8a and 8b [23]. Considering the combined results of antibacterial and hemolytic activity results of heptameric cyclic peptides with diverse hydrophobic domains (3a-3c, 4a-4c, 5a-5b, 6a, and 6b), it appears that not only the number and position of hydrophobic residues, but also their side chain chemistry, plays a crucial role. Additionally, we evaluated the hemolytic activity of all linear analogs, and the data indicated that linear peptides demonstrated lower hemolytic action compared to their cyclic counterparts (Supporting information Table S3).

2.3.2. Cell viability assay

For a more in-depth assessment of the lead cyclic peptides (3b, 4b, and 4a), we conducted cytotoxicity screenings against normal lung cells (MRC-5) (Figure 3A), kidney cells (HEK-293) (Figure 3B), liver cells (HepaRG) (Figure 3C), and human skin fibroblast cell (HeKa) (Figure 3D). At a concentration level of 50 μg/mL, the lead cyclic peptides showed negligible cytotoxicity against lung cells (93–95% cell viability), kidney cells (81–89% cell viability), and liver cells (88–91% cell viability). However, there was a slightly higher level of cytotoxicity observed against skin cells (71–78% cell viability). In accordance with international standard guidelines (ISO 10993–5), percentages of cell viability exceeding 80% are categorized as non-cytotoxic, while values within the range of 80% to 60% are considered weakly cytotoxic; 60% to 40% denote moderate cytotoxicity, and below 40% indicate strong cytotoxicity [35]. Thus, the data from the cell viability assay indicates that at 100 μg/mL, the lead peptides demonstrate non-cytotoxic effects against lung cells (MRC-5) and liver cells (HPRGC10) (>80% cell viability). However, weak cytotoxicity is observed against kidney cells (HEK-293) (>70% cell viability) and skin fibroblast cells (HeKa) (>60% cell viability). A similar trend in cytotoxicity was observed at the highest experimental concentration (250 μg/mL), with >50% cell viability observed for liver, kidney, and lung cells, while skin cells displayed relatively lower cell viability (30–37% cell viability). Overall, when considering both the hemolytic data and cytotoxicity results, it was evident that 3b, 4b, and 4a exhibited a lower cytotoxic profile when compared with previously reported peptides 8a and 8b [23].

Figure 3.

Cytotoxicity assay of lead macrocyclic peptides (3b, 4a, and 4b) and previously identified lead peptides (8a and 8b) against human (A) lung cells (MRC-5), (B) Embryonic kidney (HEK-293), (C) liver cells (HPRGC10), and (D) Skin fibroblast cells (HeKa). The results represent the data obtained from the experiments performed in triplicate (incubation for 24 h).

2.4. Membranolytic action of the lead peptides

2.4.1. Calcein dye leakage

According to the previous reports, cationic AMPs are known to exert their antibacterial action by membrane disruption, leading to the release of intracellular contents and eventually cell death [12, 25, 28]. To study the membranolytic action of the lead cyclic peptide 3b and 4b, we performed a calcein dye leakage experiment by employing negatively charged and zwitterionic calcein encapsulated lipid vesicles, which mimic the outer surface of the bacterial and mammalian cell membrane, respectively. Lead cyclic peptides 3b and 4b induced calcein dye leakage that was measured at various concentration levels ranging from 5 to 50 μg/mL at different time intervals (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Concentration-dependent leakage of calcein dye from bacterial membrane mimicking (A1-A3) and mammalian membrane mimicking (B1-B3) liposomes. (A1 and B1) 3b; (A2 and B2) 4b; (A3 and B3) daptomycin. The data obtained are from the experiments performed in triplicate.

The results demonstrated a concentration-dependent leakage of dye upon treatment of calcein encapsulated bacterial membrane mimicking liposomes treated with 3b and 4b. Both 3b and 4b exhibited similar trends of dye leakage at 5 μg/mL, resulting in approximately 20% and 60% leakage was observed after 40 and 60 min of incubation, respectively (Figures 4A1 and 4A2). With the increase in concentration of peptides 3b and 4b, a sharp increase in the amount of dye leakage was observed. At the highest experimental concentration (50 μg/mL), both peptides 3b and 4b induced 100% dye leakage after 60 min 50 min incubation, respectively (Figures 4A1 and 4A2).

Noticeably, both 3b and 4b induced a non-significant amount of dye leakage when incubated with liposomes mimicking mammalian membrane, with only 14.11% and 20.2% dye leakage, respectively, after 100 min (Figures 4B1 and 4B2). In comparison to the lead cyclic peptides 3b and 4b, daptomycin at 50 μg/mL resulted into mild dye leakage when incubated with liposomes mimicking bacterial membranes, showing only 44% of dye release observed after 100 min incubation (Figure 4A3). Additionally, a negligible amount of dye leakage (5.2%) was observed for daptomycin (50 μg/mL) when incubated with mammalian mimicking liposomes for 100 min. (Figure 4B3). The results of calcein dye leakage experiments indicated that like the most native AMPs, lead cyclic peptides 3b and 4b exert a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity via membrane perturbation action.

2.4.2. Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) analysis

To delve deeper into the membranolytic action of lead cyclic peptides 3b and 4b, we examined the treated bacterial (MRSA (ATCC BAA-1556) and E. coli (ATCC BAA-2452) and fungal (A. fumigatus (Af-293) and C. albicans (ATCC 60193)) cells using FE-SEM. The SEM micrographs conspicuously indicate the membrane-damaging properties of 3b against all the examined bacterial and fungal cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

FE-SEM images of bacterial (MRSA (A1 and B1) and E. coli (A2 and B2)) and fungal (A. fumigatus (A3 and B3) and C. albicans (A4 and B4) cells treated with lead macrocyclic peptide 3b (B1-B4) at 4×MIC for 1 h. The control for each bacterial and fungal strain (A1-A4) was done without peptide.

Untreated bacteria (Figures 5A1 and 5A2) and fungi (Figures 5A3 and 5A4) cells exhibit regular size and shape with bright and smooth surface. Upon close examination of the treated cells, a comparatively higher membrane disruptive action of lead peptides (3b) is observed against bacteria (Figures 5B1 and 5B2) as compared to fungi (Figures 5B3 and 5B4). The treatment of bacterial cells with lead peptides (3b) at 4× the MIC led to pronounced cell-specific morphological alterations (Figures 5B1 and 5B2). While the loss of membrane fluidity is quite evident for both MRSA (Figure 5B1) and E. coli (Figure 5B2), a strong membrane atrophy was observed for E. coli. As for fungi, surface blebs were noted on the surfaces of both A. fumigatus (Figure 5B3) and C. albicans (Figure 5B4), alongside a significant loss of membrane fluidity observed for A. fumigatus. These observations strongly indicate the predominant membrane-disrupting action of 3b against both bacteria and fungi. In contrast, conventional antibiotics target essential biochemical pathways at a subcellular level inhibiting microbial proliferation rather than causing physical membrane damage [36]. This fundamental difference in mechanism of action could account for the rapid bactericidal action of the lead cyclic peptide 3b (Figure 2) compared to the tested standard antibiotics.

2.5. Resistance development study

The extraordinary ability of bacterial pathogens to develop resistance has led to a significant decline in the clinical effectiveness of many conventional antibiotics. Consequently, the emergence of resistance is considered a formidable challenge, particularly last resort antibiotics. Given the membranolytic properties of lead cyclic peptide 3b, as evidenced by the calcein dye leakage experiment and SEM images, we opted its potential for inducing resistance in bacteria. We performed resistance acquisition studies using both a resistant and susceptible strain of S. aureus and E. coli. For comparative purposes, S. aureus strains were treated with daptomycin and ciprofloxacin while E. coli strains were exposed to polymyxin B and ciprofloxacin. Following each successive exposure of the bacteria to the different test specimens, new MIC was determined as an indicator of the resistance development (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Resistance induction after repeated 18 times exposures of lead cyclic peptide (3b) and standard antibiotics (daptomycin, polymyxin B, and ciprofloxacin) against (A1) S. aureus (ATCC 29213), (A2) MRSA (ATCC BAA-1556), (B1) E. coli (ATCC 25922), and (B2) E. coli (ATCC BAA-2452). The data represents the experiments conducted in triplicate.

Interestingly, similar to other peptide-based antibiotics like daptomycin and polymyxin B, negligible changes in the MIC values were observed for peptide 3b across all tested bacterial strains. In contrast, a sharp increase in the MIC values of ciprofloxacin was observed against all the tested bacterial strains. It appears that, much like other peptide-based antibacterial agents, the rapid bactericidal action achieved by membrane disruption presents a formidable hurdle for bacteria to develop resistance to counter the multifaceted mode of action. These results underscore the remarkable therapeutic potential of 3b in treating infections caused by resistant strains. The extraordinary ability of the 3b in neutralizing the bacterial cells effectively and rapidly may lead to shorter the duration of antimicrobial treatment, ultimately leaving fewer opportunities for pathogens to develop resistance via genetic mutation or phenotype modifications such as persister cells or biofilm formation.

2.6. Plasma stability

Most of the naturally occurring AMPs are structurally linear and fairly large molecules. Consequently, the presence of numerous scissile amide bonds makes them susceptible to degradation by various peptidases. The inherent enzymatic instability leads to the inactivation of these potent antimicrobial molecules within the intended biological environment. Addressing this issue is essential for the effective implementation of peptide-based therapeutics in clinical settings. The cyclic nature of macrocycles has been shown to enhance resistance to degradation by proteases, as the cyclic framework of peptides do not fit as neatly into the active site of endopeptidase active site and also shields most vulnerable sites to peptidases [37]. Head-to-tail cyclization is considered as one of the most prominent approaches to enhance the stability. In addition, the incorporation of unnatural amino acids provides an added layer of protection against peptidases.

To this end, we examined the stability of peptide 3b in human blood plasma over a 24 h period (Figure 7). After a 30 min incubation, approximately 82.4% of the intact peptide 3b was observed. Moreover, after 12 h incubation, about 52.3% of peptide 3b remained undegraded. Roughly 44.9% of the intact peptide 3b was still present after 24 h incubation. The results of the stability study indicate that peptide 3b possesses a half-life (t1/2) of 13 h. It appears that the cyclic structure in combination with the presence of unnatural building blocks in 3b, imparts additional plasma stability.

Figure 7.

In vitro plasma stability assay of the lead macrocyclic peptide 3b. The data represents the percentage of undegraded peptide measured using Q-TOF LC/MS as the area under the curve in extracted ion chromatogram in three independent experiments.

2.7. Examination of interaction with the model membrane using NMR

The interaction of cyclic peptides 3b and 4b with model membranes was evaluated by 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Similar to previously studied short AMPs that demonstrated selectivity towards the bacterial membrane,[23, 38] peptides 3b and 4b showed distinct effects and modes of interaction with the liposomes mimicking bacterial or mammalian membranes. To evaluate the interaction and the effect of lipids on the structural characteristics of the peptide we utilized homonuclear 1D and 2D-Noesy 1H-NMR spectroscopy. We used three different media: water, liposomes mimicking bacterial membranes (DOPC/DOPG, 7:3 w/w ratio), and liposomes mimicking mammalian membranes (DOPC/Cholesterol, 9:1 w/w ratio), enabling a comparison of the characteristics of 1D-1H-NMR spectra (signal positions and linewidth) of peptides 3b and 4b (Figure 8 and Figure S59, Supporting Information).

Figure 8.

Amide/aromatic regions of 1D 1H-NMR spectra of peptide 3b in water (black, bottom), DOPC/Cholesterol liposomes (blue, middle), and DOPC/DOPG liposomes (green, top). The assignment of the HN resonances is shown with the dashed lines and residue label. “U” stands for Dip residues.

NMR spectrum of peptide 3b in water showed a broadening of all amide hydrogen (HN) signals, reaching the level of complete disappearance of the HN signals of Arg3 and Dip5, along with strong broadening of all other HN signals (Figure 8, bottom black spectrum). The disappearance and broadening can be attributed to an intermediate conformational exchange of the backbone due to its restricted flexibility, as well as the presence of multiple conformers and/or oligomeric states. However, close to zero NOE values for peptide 3b in water (data not shown) correspond to a small peptide molecule with a molecular weight ranging from 1.0 to 1.5 kDa, indicating conformational exchange, but not indicative of high-order oligomers with a high molecular weight.

Conversely, the presence of bacterial membrane mimics leads to a reduction in linewidths of the HN signals from above 20 Hz range to below 14 Hz, and rendering all amide signals visible (Figure 8, top green spectrum). These spectral changes can be interpreted as a transition of backbone conformational dynamics from an intermediate (milliseconds) to a fast (microseconds and below) range, and a shift in conformational/oligomeric equilibrium towards a more uniform and likely monomeric state. These shifts in peptide structural behavior induced by the lipids are facilitated by the strong electrostatic interaction between the peptide’s cationic side chains and the negatively charged phospholipid headgroups characteristic for the bacterial membrane.

In turn, when the same experiment was performed with peptide 3b in the presence of liposomes mimicking mammalian membranes, the resulting NMR spectrum (Figure 5, middle blue spectrum) still showed broadened amide hydrogen signals (linewidths in 15–20 Hz range). This indicates a mixture of the peptide states present in both water and bacterial membrane mimics (Figure 8, bottom and top spectra, respectively).

The analysis of 2D NOESY spectra in three different media confirms efficient interaction of peptide 3b with the bacterial membrane mimicking liposomes. Indeed, the NOESY spectrum in DOPC/DOPG liposomes, which mimic bacterial membranes (Figure 9A), shows a strong increase in the absolute value of NOEs compared to the spectra recorded in water (not shown) and in DOPC/Cholesterol liposomes, which mimic mammalian membranes (Figure 9B). The increase in absolute intensity of NOE arises from the extended overall correlation time of the peptide due to its interaction with the lipid bilayer and binding to the large liposome particles.

Figure 9.

Amide/aromatic regions of NOESY spectra of peptides 3b (top row, A and B) and 4b (bottom row, C and D) in DOPC/DOPG liposomes (left, A and C) and in mixed DOPC/Cholesterol liposomes (right, B and D).

Further comparison of the 2D NOESY spectra of peptide 3b in the presence of different liposomes (Figure 9 panels A and B) shows a remarkable difference in the cross-peaks originating from amide hydrogens. The presence of bacterial mimics induces a vast network of NOE contacts for the amide protons (Figure 9A). Conversely, in the presence of the mammalian mimics, all amide hydrogens of 3b, with the exception of Trp6, appear to be accessible to water. Notably, all Arg and both Dip amide resonances exhibit strong exchange cross-peaks with water at 4.7 ppm (Figure 9B, blue dashed arrow). In the presence of bacterial membrane mimics, only the amide hydrogens of Arg residues display weak exchange cross-peaks with water. This distinction in the spectral characteristics of peptide 3b in bacterial and mammalian-mimicking environments corroborated the stronger interaction and potentially, deeper incorporation of the peptide into the bacterial-type membranes. These results align well with the activity assays data described above.

The 1D-NMR data suggest much faster backbone dynamics of peptide 4b in water compared to 3b. Unlike peptide 3b, all amide resonances are relatively sharp, with linewidths in water are below 15 Hz, and they exhibit substantial changes in all three used media (Figure S59, bottom spectrum, Supporting Information). When interacting with bacterial-mimicking liposomes, there is only a slight increase in linewidth of the amide hydrogens. This could be attributed to either the increase of the overall size of the peptide-lipid particles or to the constrained flexibility of the peptide backbone within the liposomes. Comparison of the 2D NOESY spectra of peptide 4b in different liposomes (Figure 9 panels C and D) shows a similar yet less pronounced effect than for peptide 3b (Figure 9 panels A and B), with stronger NOE effect in the bacterial-mimicking liposomes compared to the mammalian-mimicking ones. In summary, the NMR results are in agreement with other methodologies, affirming the selectivity of peptides 3b and 4b towards the bacterial membranes. Among the latter, higher antibacterial activity and lower hemolytic toxicity are inherent in the peptide 3b.

2.9. Computational analysis

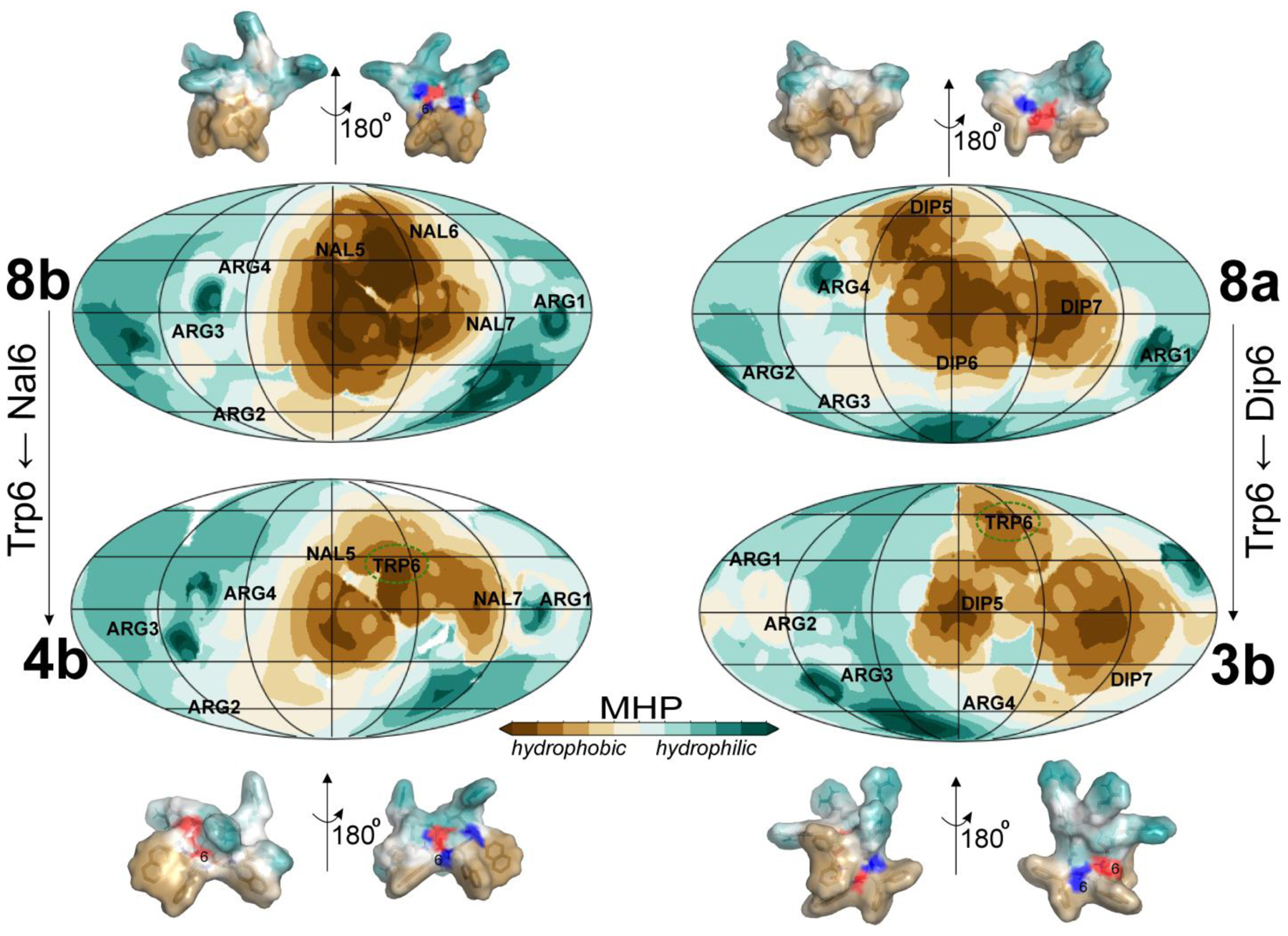

As s previously demonstrated [23], the lead cyclic peptides 8a and 8b possess prominent amphiphilic properties on their surfaces. The positively charged Arg residues and Dip/Nal residues contribute to the polar and hydrophobic regions, respectively. MD simulations of these peptides with bacterial mimic lipid bilayers showed deep penetration of the peptides into the membrane core via their hydrophobic parts [23].

In this study, we observed alterations in both hemolytic and antibacterial activity when replacing unnatural amino acids (Dip/Nal) with Trp in the peptides. Since the side chain surface of Trp is ~10–15% smaller than that of Dip or Nal, the substitution leads to weakening of the surface hydrophobic pattern in the Trp mutants compared to the parent peptides 8a and 8b. At the same time, the impact of mutations of hydrophobic residues on membrane-binding properties of the peptides depends not only on the type of amino acid residue but also on its position within the sequence.

To investigate the influence of Trp-induced changes on the conformational mobility and organization of the hydrophobic membrane-binding motif in peptides 3a, 3b, 4a, and 4b, in comparison with the previously reported peptides 8a and 8b, we conducted a series of all-atom MD simulations in an explicit water environment.

Analysis of the ensemble of accumulated MD states clearly indicates an increase of conformational mobility in peptides 3a, 3b, 4a, and 4b. The average pairwise root mean square deviation (RMSD) values for the backbone atoms of peptides 8a/3a/3b and 8b/4a/4b are 0.84/1.06/1.15 and 1.01/1.08/1.17 Å, respectively. Also, in all mutants, there is a reduction in the ratio of apolar/polar solvent-accessible molecular surface areas (Tables S4 and S5). Besides the elevated conformational mobility, the analysis of MD-states with different spatial arrangements of the apolar surface indicates that the Trp-mutants (3a, 3b, 4a, and 4b, Tables S4 and S5) also have increased flexibility in their hydrophobic surfaces. As expected, the replacement of Dip/Nal with a Trp residue increases heterogeneity of the ensemble of accumulated MD states. While for 8a and 8b only 1–2 groups of the most populated states were observed, for mutants the number of such groups and the variety of MD states were much greater.

MD-states, characterized using the molecular hydrophobicity potential (MHP) approach [39] (Figure S1), were evaluated through the MD simulations to delineate the structural/dynamic parameters (Tables S4, S5) of the most populated states (Table S6).

Additional details regarding the structural parameters of the peptides and their MD-derived hydrophobic surface clusters can be found in the Supporting Information (Figure S1, Table S4, S5, and S6).

Based on the analysis of the most populated MD states, it was concluded that both parent peptides (8a and 8b) possess extensive hydrophobic surface area devoid of polar inclusions (Figure 10, top panel). In contrast, peptides 3b and 4b exhibit relatively weaker and more variable hydrophobic patterns. As a result, the overall solvent exposure of the backbone atoms of hydrophobic residues increases in both 3a and 3b compared to 8a. The backbone, particularly the NH-group, of the central hydrophobic residue 6, which is buried in 8a, becomes much more accessible to water in 3a and 3b (Table S4). As illustrated in Figure 10, the presence of hydrophilic surface spots in 3b and 4b, formed by the polar backbone, has an impact on the integrity of the apolar motif.

Figure 10. Rearrangements of structural/hydrophobic properties of the parent peptides 8a and 8b and their mutants 3b and 4b as revealed by MD simulations in aqueous solution.

Hydrophobic properties of peptides are expressed in terms of the MHP distribution on their solvent-accessible surfaces. The MHP values are color-coded according to the scale bar. Properties of the entire peptide surface are shown as MHP spherical projection maps for representatives of the dominant MD states. Projections of centers of mass of the residues are given with the corresponding residue names and numbers. Alterations of the hydrophobic pattern (residues 5–7), accompanied by the exposure of polar backbone atoms of peptides are visualized in 3D representations of MHP-encoded molecular surfaces. The location of the solvent accessible backbone atoms on the apolar pattern is highlighted with red and blue colors for CO and NH groups, respectively. Trp6 is marked with dashed ellipses on spherical projection maps and identified by residue number on the 3D MHP-surfaces of peptides 3b and 4b.

2.5.2. Characteristics affecting the activity and selectivity of the peptides.

The overall hydrophobicity of membrane-active peptides holds particular importance in interactions with zwitterionic membranes, such as those in mammals. A decrease in hydrophobicity often correlates with a reduction in peptide toxicity. Indeed, all mutant peptides exhibit less hemolytic activity compared to the parent peptides 8a and 8b. However, the observed minor changes in overall hydrophobicity are not sufficient to fully account for the significant difference in toxicity between the parent peptides and their Trp-single mutants, or to explain the position-dependent effects of residue substitution with Trp.

Analysis of MD data suggests that a single-Trp substitution at positions 5 or 6 in peptides 8a and 8b weakens the packing order, thereby enhancing the overall flexibility of the hydrophobic patch in peptides 3a, 3b, 4a, and 4b. As a result, the cohesive hydrophobic patterns of 8a and 8b transform into separated apolar fragments (Figure 10). Notably, substitution with Trp at position 6 in the center of the hydrophobic region of the parent peptides 8a and 8b leads to the most pronounced weakening of the consolidation of the hydrophobic pattern in the corresponding peptides 3b and 4b, rendering them the least toxic.

The features of the structural, dynamic and hydrophobic organization of parent peptides and their mutants, characterized based on MD simulations in water, suggest scenarios for the behavior of peptides in lipid bilayers mimicking the membranes of eukaryotic (e.g., DOPC) and bacterial (e.g., DOPC/DOPG) cells, respectively. Previously, we have applied this approach to other antimicrobial peptides [23, 36]. Based on this and literature data, it seems reasonable that there are no strong electrostatic peptide-membrane interactions in the zwitterionic bilayer, therefore, the embedding of the peptide is mainly due to the correspondence of the hydrophobic/polar properties of its surface with those on the membrane interface. Parent peptides 8a and 8b with pronounced hydrophobic patterns will tend to penetrate deeply into the nonpolar region of the bilayer. This leads to destabilization of the model “eukaryotic” membrane, explaining the high hemolytic activity of peptides. In the Trp mutants, these surface hydrophobic patterns are significantly weakened (especially in peptides 3b and 4b), and additional polar regions appear on the surface due to exposure of backbone atoms. As a result, the binding of the mutant peptides to the model mammalian membrane presumably becomes less effective, correlating with a decrease in the hemolytic activity and cytotoxicity of the mutants. In turn, upon interaction with the model bacterial membrane, in addition to hydrophobic contacts, strong electrostatic interactions with the lipid headgroups, as well as the higher conformational plasticity of the mutant peptides’ hydrophobic surfaces demonstrated in this work play an important role. These features allow the peptides to efficiently adapt to the membrane environment in the presence of strong charge contacts. Better membrane affinity explains higher antimicrobial activity of the designed single Trp mutants.

3. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study presents a comprehensive exploration of small amphiphilic membrane-active cyclic peptides composed of various nongenetically encoded hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids. Lead cyclic peptides 3b and 4b exhibited potent broad-spectrum activity against drug-resistant Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as fungi. Furthermore, the peptides exhibited notable antibiofilm activity against both bacterial and fungal strains, with lead peptides 3b and 4b demonstrating particularly impressive results. Noticeably, when compared to standard antibiotics, lead peptides showed either comparable or higher activity against drug resistant Gram-positive bacteria (Enterococcus faecium (ATCC 700221) and Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 51575)), which are known to cause difficult-to-treat infections. Moreover, the low MIC of 3b (6.2 μg/mL) against Clostridium difficile (NAP1/027) further highlights its therapeutic potential. Their rapid bactericidal action was evidenced by the kill-kinetic assay, wherein they eliminated MRSA and E. coli cells even faster than the standard antibiotics. In addition, the results revealed that the presence of both monovalent and divalent cations had minimal effect on MIC values, suggesting that the peptides’ inherent structure and positive charge density played a dominant role in their antimicrobial action. The peptides’ selectivity for bacterial membranes over mammalian membranes was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy and calcein leakage experiments.

The structural basis for their membranolytic action was elucidated through various computational techniques. The study highlighted the importance of the structure and flexibility of the hydrophobic surface in determining antibacterial and hemolytic activities of the peptides. Peptide 3b showed higher antibacterial activity and lower toxicity compared to its analogs, emphasizing the significance of subtle changes in surface distribution of hydrophobic patterns. The increased conformational mobility of mutant peptides (3a, 3b, 4a, and 4b) enhances their structural adaptability, a crucial factor when interacting with negatively charged bacterial membranes. While strong electrostatic interactions between charged groups of Arg and lipid heads prevent the peptide from dissociating from the membrane surface, structural plasticity ensures efficient incorporation of the entire hydrophobic motif into the membrane core. As a result, mutant peptides 3a, 3b, 4a, and 4b maintain or even enhance their antibacterial activity in comparison to their corresponding parent peptides 8a and 8b.

Importantly, lead peptide 3b exhibited remarkable stability in human blood plasma and shows no signs of resistance development against antibiotic-resistant strains. The newly designed cyclic peptides represent promising candidates for the development of effective and selective anti-infective agents. The results underscore the potential of these cyclic peptides as a valuable addition to the arsenal of antimicrobial agents, particularly against drug-resistant strains. Taken together, these outcomes underscore the potential of lead peptide 3b as a promising peptide-based anti-infective agent. Lead peptide 3b exhibits promising potential for combating Gram-positive bacteria, characterized by its rapid time-dependent killing, anti-biofilm properties, low propensity for resistance development, and minimal cytotoxicity and hemolytic activity. These combined attributes position it as comparable to or even superior to standard anti-infective agents used in the treatment of Gram-positive infections.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

2-Chlorotrityl chloride resin (loading capacity of 0.572 mmol/g) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The coupling reagent 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), along with amino acids Fmoc-Arg(pbf)-OH and Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH, were purchased from AAPPTec LLC (Louisville, KY, USA). Unnatural amino acids Fmoc-L-Ala(3,3-diphenyl)-OH, Fmoc-L-Ala(1-naphthyl)-OH, Fmoc-L-Agp(Boc)2-OH, Fmoc-L-Agb(Boc)2-OH, and Fmoc-hArg(Pbf)-OH were acquired from Chem-Impex International Inc. (Wood Dale, IL, USA). N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), acetic acid, triisopropylsilane (TIS), piperidine, and all other necessary reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 1-Hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole (HOAt), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), and 1,3-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI, USA). We obtained ultra-pure water from the Milli-Q system (Temecula, CA, USA). The MTS assay kit (98%) was procured from Promega (Madison, WI, USA), while single donor human Plasma K2 EDTA was obtained from Innov-Research (Novi, MI, USA). All phospholipids and cholesterol were sourced from Avanti polar Lipids (Alabaster, USA). Calcein dye was sourced from Sigma.

All supplies for mammalian and bacterial cell culture were acquired from Corning (Christiansburg, VA, USA) and Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Mammalian and bacterial cell experiments were conducted in a laminar flow hood Labconco (Kansas City, MO, USA). Cell cultures were maintained out at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a Forma incubator using a T-75 flask. The human lung fibroblast cell (MRC-5, ATCC No. CCL-171), human embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293, ATCC No. CRL 1573), and human hepatoma HepaRG cells (Gibco, HPRGC10) were procured from ATCC (USA) and cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator (37 °C). Human serum was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All bacterial strains employed in this study are procured from VWR, USA and propagated as per the recommendation of American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The bacterial and fungal strains with their classification and properties are listed in Table S1 and Table S2, respectively (Supporting Information).

4.2. Solid-phase peptide synthesis and macrocyclization

The peptides were manually synthesized on 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin following the standard Fmoc/tBu solid-phase peptide synthesis protocol. Fmoc-L-amino acid building blocks were linked to the resin using HBTU, HOBt, and DIPEA in DMF. Following each coupling step, Fmoc protecting groups were eliminated by treating with 20% (v/v) piperidine in DMF. Once the desired peptide sequence was achieved, the side chain-protected peptides were released from the resin by treating the peptidyl resin with a mixture of TFE/acetic acid/DCM [2:1:7 (v/v/v)] and cyclized using HOAt and DIC in an anhydrous DMF/DCM mixture. After the head-to-tail cyclization, the protecting groups were removed with a cocktail of TFA/water/TIS [95:2.5:2.5 (v/v/v)], and the crude peptide was precipitated with ice-cooled diethyl ether. Following several ether washes, the crude mass was redissolved in acetonitrile/water (1:1 v/v with 0.5% TFA), and the solution was lyophilized to obtain the crude peptide. The same procedure was used for the synthesis of linear peptides, except that after achieving the desired peptide sequence, complete cleavage was carried out in the presence of TFA/water/TIS [95:2.5:2.5 (v/v/v)].

4.3. Purification and analytical characterization of peptides

The crude linear and cyclic peptides underwent purification using a reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) system (Shimadzu LC-20AP). Peptides were dissolved in acetonitrile/water (1:2 v/v, with 0.5% TFA) to a final concentration of 15 mg/mL. Following filtration through a 0.45 μm Millipore filter, the peptide solutions were introduces onto the column through multiple 10 mL injections. A preparative C18 column (Gemini, 5 μm particle size, 100 Å pore size, 21.2 mm × 250 mm) from Phenomenex was employed, using a mixture of acetonitrile and water (both containing 0.1% (v/v) TFA) as eluent at a flow rate of 10 mL/min. The wavelength for detection was configured to 220 nm. Fractions containing the desired peptides were subsequently lyophilized.

Peptide purity was conducted on an RP-HPLC system Prominence-i (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) utilizing an analytical Delta-Pak (Waters) C18 column (100 Å, 5 μm, 3.9 mm × 150 mm). The molecular mass of the purified peptides was determined in positive ion mode using EVOQ Triple Quadrupole LC-TQ (Q-Tof, Bruker, USA). Detailed information regarding the purity (>95%) and high-resolution mass data of all cyclic peptides and their linear analogs have been provided in the supporting information.

1a [Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Dip-Dip]: HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z) C59H72N16O6 calcd: 1100.5821; found, 1101.6416 [M+H]+, 550.7297 [M+H]2+; 1b [Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Trp-Dip]: HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C59H72N16O6 calcd: 1100.5821; found, 1101.5636 [M+H]+, 550.7509 [M+H]2+; 1c [Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Dip-Trp]: HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C59H72N16O6 calcd: 1100.5821; found, 1101.5648 [M+H]+, 550.2918 [M+H]2+; 2a [Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Nal-Nal] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C55H68N16O6 calcd: 1048.5508; found, 1049.5423 [M+H]+, 525.2834 [M+2H]2+; 2b [Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Trp-Nal] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C55H68N16O6 calcd: 1048.5508; found, 1049.5416 [M+H]+, 525.2822 [M+2H]2+; 2c [Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Nal-Trp] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C55H68N16O6 calcd: 1048.5508; found, 1049.5419 [M+H]+, 525.2830 [M+2H]2+; 3a [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Dip-Dip] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C65H84N20O7 calcd: 1256.6832; found, 1257.6711 [M+H]+, 629.3439 [M+2H]2+; 3b [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Trp-Dip] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C65H84N20O7 calcd: 1256.6832; found, 1257.6693 [M+H]+, 629.3430 [M+2H]2+; 3c [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Dip-Trp] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C65H84N20O7 calcd: 1256.6832; found, 1257.6684 [M+H]+, 629.3426 [M+2H]2+; 4a [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Nal-Nal] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C61H80N20O7 calcd: 1204.6519; found, 1205.6396 [M+H]+, 603.3283 [M+2H]2+; 4b [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Trp-Nal] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C61H80N20O7 calcd: 1204.6519; found, 1205.6399 [M+H]+, 603.3282 [M+2H]2+; 4c [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Nal-Trp] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C61H80N20O7 calcd: 1204.6519; found, 1205.6405 [M+H]+, 603.3286 [M+2H]2+; 5a [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Dip-Trp] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C61H81N21O7 calcd: 1219.6628; found, 1220.5623 [M+H]+, 610.2812 [M+H]2+; 5b [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Trp-Nal-Trp] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C59H79N21O7 calcd: 1193.6471; found, 1194.5620 [M+H]+, 597.2815 [M+H]2+; 6a [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Dip-Leu-Dip] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C60H85N19O7 calcd: 1183.6879; found, 1184.5416 [M+H]+, 592.2817 [M+2H]2+; 6b [Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Nal-Leu-Nal] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C56H81N19O7 calcd: 1131.6566; found, 1132.6742 [M+H]+, 566.3456 [M+2H]2+; 7a [Arp-Arp-Arp-Arp-Dip-Trp-Dip] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C57H68N20O7 calcd: 1144.5580; found, 1145.6715 [M+H]+, 572.8342 [M+H]2+; 7b [Arb-Arb-Arb-Arb-Dip-Trp-Dip] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C61H76N20O7 calcd: 1200.6206; found, 1201.6701 [M+H]+, 600.8432 [M+H]2+; 7c [hArg-Arg-hArg-Arg-Dip-Trp-Dip] HR-MS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): C67H88N20O7 calcd: 1284.7145; found, 1286.1697 [M+H]+, 642.8143 [M+H]2+.

4.4. Measurement of antibacterial activity

The peptides were assessed for their antibacterial efficacy against a spectrum of susceptible and drug-resistant bacterial strains. Antibacterial susceptibility was evaluated using the microtiter dilution method endorsed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), with results quantified as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) -, denoting the lowest peptide concentration that inhibited bacterial growth. Additional information regarding the bacterial strains and their growth conditions can be found in the Supporting Information (Table S1).