Abstract

An experiment performed in London nearly 120 years ago, which by today's standards would be considered unacceptably sloppy, marked the beginning of the calcium (Ca2+) signaling saga. Sidney Ringer [Ringer, S. (1883) J. Physiol. 4, 29–43] was studying the contraction of isolated rat hearts. In earlier experiments, Ringer had suspended them in a saline medium for which he admitted to having used London tap water, which is hard: The hearts contracted beautifully. When he proceeded to replace the tap water with distilled water, he made a startling finding: The beating of the hearts became progressively weaker, and stopped altogether after about 20 min. To maintain contraction, he found it necessary to add Ca2+ salts to the suspension medium. Thus, Ringer had serendipitously discovered that Ca2+, hitherto exclusively considered as a structural element, was active in a tissue that has nothing to do with bone or teeth, and performed there a completely novel function: It carried the signal that initiated heart contraction. It was a landmark observation, which should have immediately aroused wide interest. Unexpectedly, however, for decades it attracted no particular attention. Occasionally, farsighted pioneers argued forcefully for a messenger role of Ca2+, offering compelling experimental evidence. Among them, one could quote L. V. Heilbrunn [Heilbrunn, L. V. (1940) Physiol. Zool. 13, 88–94], who contracted frog muscle fibers by applying Ca2+ salts to their cut ends, but not to their surfaces. Heilbrunn correctly concluded that Ca2+ had diffused from the cut ends to the internal contractile elements to elicit their contraction. One could also quote K. Bailey [Bailey, K. (1942) Biochem. J. 36, 121–139], who showed that the ATPase activity of myosin was strongly activated by Ca2+ (but not by Mg2+), and concluded that the liberation of Ca2+ in the neighborhood of the myosin controlled muscle contraction. Clearly, enough evidence was there, but only a handful of people had the vision to see it and to foresee its far-reaching implications. Perhaps no better example of clairvoyance can be offered than the quip by O. Loewy in 1959: “Ja Kalzium, das ist alles!”

The situation changed abruptly at the end of the 1950s thanks to some seminal discoveries that paved the way for the acceptance of what is now called the calcium concept. One was the demonstration by Weber (1) that the binding of Ca2+ to myofibrils activated actomyosin. Another was the finding in the laboratories of Ebashi and Lipmann and Hasselbach and Makinose (2–4) that isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles accumulated Ca2+ by using an ATP-energized system. Then, there was the discovery by Ebashi and Kodama (5) of troponin in crude tropomyosin preparations, followed by the demonstration that one of its subunits, troponin C, was the Ca2 + receptor that mediated myofibrillar contraction. One should perhaps also mention a seldom-quoted yet very important methodological contribution. This was the synthesis of EDTA and the characterization of its Ca2+-chelating properties by G. Schwarzenbach and Ackermann (6). It was EDTA that allowed Bozler (7) to perform in 1954 a key experiment in which the removal of Ca2+ by the chelator relaxed muscle fibers.

Thanks to these early discoveries, interest in the signaling role of Ca2+ started to increase, slowly at first and then more rapidly, eventually reaching today's explosive phase. The element is now recognized as an essential messenger that accompanies cells throughout their entire lifespan, from their origin at fertilization, to their eventual demise at the end of the life cycle. At first glance, then, Ca2 could be considered both an essential mediator of activity during cell life and as a conveyor of doom at the moment of cell death. Such a view, however, would be simplistic. The Ca2+-mediated death of cells exposed to toxic insults has an obvious negative connotation, but the processing of Ca2+ signals to terminate the cell life by apoptosis is instead a positive and necessary way to decode the Ca2+ signal.

The rapid advancement of the Ca2+ field has now swollen the literature to a size where it would be impossible to cover all of it in a few pages. Because a number of comprehensive reviews are available (e.g., refs. 8–11), this contribution will focus only on the most significant recent advances. The choice will be unavoidably arbitrary, but it should give readers the feeling for the most exciting developments in the area.

Background Information

Once Ca2+ was recognized as a carrier of signals, it became important to understand how its concentration within cells was regulated. Reversible complexation to specific ligands soon emerged as the only reasonable means to perform the task. A number of small cell ligands bind Ca2+ with low affinity, but the process needed complex ligands able to complex Ca2+ with the specificity and affinity demanded by the intracellular ambient. A breakthrough in this direction was the solution of the crystal structure of parvalbumin by Kretsinger (12) in 1972. This still functionally mysterious Ca2+ binding protein was to become the progenitor of a family of proteins known as EF hand proteins, which has now grown to nearly 600 members. EF hand proteins do buffer Ca2+ but also play another important role: They decode the information carried by Ca2+ and pass it on to targets. They do so by changing conformation after binding Ca2+ and after interacting with targets. Fig. 1 shows these changes, using calmodulin (CaM) as an example. Essentially, EF hand proteins become more hydrophobic on the surface after complexing Ca2+, approach the target, and collapse around its binding domain. Thus, these proteins are better defined as Ca2+ modulated proteins, or Ca2+ sensors.

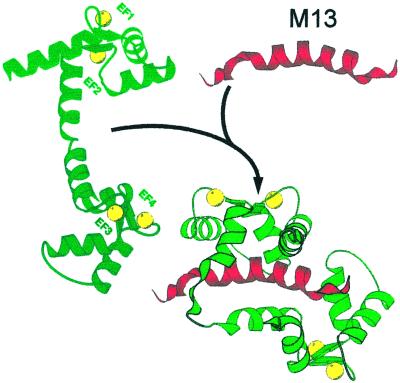

Figure 1.

Decoding of the Ca2 + signal by conformational changes in EF hand proteins (CaM). CaM interacts with a 26-residue binding domain (red peptide, top right) of a skeletal muscle myosin light chain kinase termed M13. CaM (left) has bound Ca2+ (yellow shares) to its four EF hands. It has already undergone the change that has made its surface more hydrophobic, but it still is in the fully extended conformation. The interaction with M13 collapses it to a hairpin shape that engulfs the binding peptide.

Other proteins also decipher Ca2+ signals, e.g., the annexins, gelsolin, and proteins containing C2 domains, but the EF hand proteins are the most important. They may function as a committed separate subunit of a single (enzyme) protein or as a subunit that associates reversibly with different proteins (e.g., CaM). They may even be an integral portion of the sequence of enzymes (e.g., calpain).

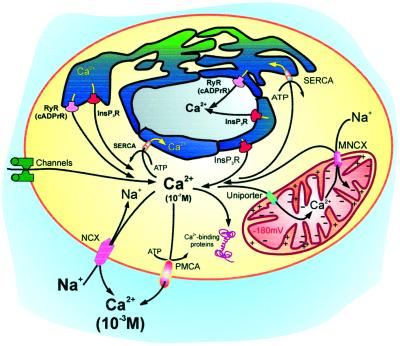

The control of Ca2+ concentration in the cytoplasm and organelles is instead the sole role of proteins that, as a rule, are intrinsic to the plasma membrane and to the membranes of organelles (the rule has exceptions, e.g., the reticular luminal protein calsequestrin) and transport Ca2+ across them (Fig. 2). These proteins have no direct role in the processing of the Ca2+ signal, but may also be targets of Ca2+ regulation. (an obvious case is that of Ca2+ channels). These proteins belong to various classes: Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane are gated by voltage, by ligands, or by the emptying of internal Ca2+ stores. In the endo(sarco)plasmic reticulum (ER/SR), they are instead activated by the second “messengers,” inositol 1-4-5 trisphosphate (InsP3) and cyclic ADP ribose (cADPr). cADPr is assumed to act on channels that are also called ryanodine receptors and that are sensitive to the agonist caffeine. Accessory (protein) factors, among them CaM, may be required for the Ca2+-releasing effect of cADPr. ATPases (pumps) are found in the plasma membrane (PMCA), in the ER/SR Ca2+ pump (SERCA), in the Golgi, and in the nuclear envelope (in yeasts, they are also found in other organelles). They export Ca2+ to the ER/SR lumen or to the extracellular spaces. Other transporters are the Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (NCX). Animal cells contain two NCX types, one in the plasma membrane and one in the inner membrane of mitochondria, the former being far better understood. In heart, NCX ejects Ca2+ after the contraction phase, whereas the mitochondrial NCX returns to the cytosol the Ca2+ that had been accumulated in the matrix by a still mysterious, electrophoretic uniporter. The existence of so many diverse Ca2+ transporters is justified by their different properties, which satisfy all demands of cells in terms of Ca2+ homeostasis; e.g., pumps have high Ca2+ affinity but limited transport capacity, and the plasma membrane NCXs have opposite properties.

Figure 2.

The Ca2+ transporters of animal cell membranes. Plasma membrane (PM) channels are gated by potential, by ligands (e.g., neurotransmitters), or by the emptying of Ca2+ stores. Channels in the ER/SR are opened by InsP3 or cADPr (the cADPr channel is sensitive to ryanodine, and is thus called ryanodine receptor, RyR). The ER/SR channels are shown with a large domain protruding into the cytosol. ATPase (pumps) are found in the PM (PMCA) and in the ER/SR (SERCA). The nuclear envelope, which is an extension of ER, contains the same transporters of the latter. NCXs are located in the PM (NCX) and in the inner mitochondria membrane (MNCX). A uniporter driven by the internal negative potential (−180 Mv) transports Ca2+ into mitochondria. A Ca2+ pump has also been described in the Golgi (not shown). Ca2+-binding proteins are represented with the dumbbell shape typical of CaM.

Based on the background information above some striking developments in Ca2+-signaling will now be discussed. When necessary, additional general information will be provided to facilitate the understanding of specific aspects.

Ca2+-Binding Proteins

EF hand proteins bind Ca2+ with high affinity to helix–loop–helix motifs that are repeated from 2 to 12 times. The motifs normally coordinate Ca2+ to side-chain oxygens of invariant residues occupying positions 1, 3, 5, and 12 of the loop, and to the carbonyl oxygen of a less conserved residue at position 7. Position 9 is the side-chain oxygen of a glutamic acid, or a water oxygen. Variations to the canonical coordination scheme have been described, e.g., carbonyl oxygens may be preferred to carboxyl oxygens, oxygens of extra residues may be inserted in a classical loop altering the coordination scheme, and side-chain oxygens from neighboring helices may be used instead of loop oxygens. The recent findings of EF hand proteins in the extracellular ambient deserve a comment. Because extracellular Ca2+ is constantly millimolar, EF hand proteins exposed to it cannot have a Ca2+-modulated function. Other recent findings have shown that EF hand proteins may also use diverse Ca2+-binding motifs. The protease calpain has a C-terminal domain with 4 canonical EF hands (domain IV) and a smaller subunit homologous to domain IV (domain VI). The three-dimensional structure of the larger subunit (13, 14) has shown an antiparallel β-sheet sandwich with an acidic stretch at one end similar to Ca2+-binding C2 domains, which may form a binding cradle for Ca2+. Two novel Ca2+-binding motifs have also been identified next to the catalytic site (15). Thus, the large subunit of calpain may bind Ca2+ at up to 7 sites, 4 of them EF hand type, one C2 type, and 2 of a novel type. One last finding that may have very important implications has emerged from the crystal structure of diisopropylfluorophosphatase (DPFase) from Loligo vulgaris (16). Strikingly, of the two Ca2+ atoms found in DPFase, one has the traditional allosteric role, promoting the interaction of enzyme domains, but the other is tightly bound at the active site and may participate directly in the catalytic process. Such a role for Ca2+ would be strikingly novel: As is well known, Ca2+ has never been known to participate directly in catalysis. Another interesting aspect of DFPase is the presence of a nitrogen atom among the atoms that coordinate Ca2+.

A group of EF hand proteins that has recently acquired prominence is that of the neuronal calcium sensors (NCS) (17). They are divided in five subfamilies. Two are expressed in retinal photoreceptors [the recoverins and the guanylate cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs)], and three in central neurons and in neuroendocrine cells (the frequenins, the visinin-like proteins, and the Kv channel-interacting proteins). Recoverins and GCAPs have established roles in phototransduction: Recoverin inhibits rhodopsin kinase, and GCAPs activate GC. The other three NCS families are proposed to regulate the release of neurotransmitters, the biosynthesis of polyphosphoinositides, the metabolism of cyclic nucleotides, and the activity of type A K+ channels. Most NCSs are N-terminally myristoylated. After complexing Ca2+, they expose the myristoyl residue and hydrophobic portions of the sequence, favoring interaction with membranes (or target proteins). Thus, the Ca2+-myristoyl switch could be a means to compartmentalize signaling cascades in neurons and/or to transduce Ca2+ signals to the membranes. Importantly, NCSs are linked to human pathology. One of the Kv channel-interacting proteins, KChIP3, has a nearly identical nucleotide sequence to the repressor of transcription DREAM (18) and to calsenilin, a protein interacting with preselinin, whose mutations cause familial Alzheimer's disease (19). GCAP gene mutations are associated with autosomal dominant cone distrophy (20–22). Recoverin is involved instead in cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR) (23, 24). The protein, normally expressed only in photoreceptors, is also expressed in nonneuronal tumors of patients with CAR, triggering the immunological response that leads to the degeneration of the photoreceptors.

The Ca2+ ATPase of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (SERCA Pump)

A major breakthrough in the area has been the solution of the crystal structure of the SERCA pump in the Ca2+-bound E1-state by Toyoshima et al. (25). The structure has validated and extended a number of former proposals and predictions. The 100-kDa pump, first purified by MacLennan (26) about 30 years ago, is proposed to span the membrane 10 times and to have 3 cytoplasmic units. The middle unit contains the catalytic aspartic acid that becomes phosphorylated by ATP as in other P-ATPases (27). Mutagenesis experiments had identified a number of residues in transmembrane domains (M) 4, 5, 6, and 8, which would form the path for Ca2+ across the protein (28). The 2.6-Å resolution structure of the pump (Fig. 3) has confirmed the 10 predicted transmembrane helices that had also been shown by an 8-Å structure determined by cryoelectromicroscopy on tubular crystals (29). The three cytosolic domains have been termed N (nucleotide binding), P (phosphorylation), and A (actuator, or N-anchoring domain). The ATP binding site in the N domain and the catalytic aspartic acid in the P domain are separated by 25 Å, but large conformational movements have been predicted to occur during ATP-energized Ca2+ translocation. The fitting of the atomic structure to the 8-Å resolution tubular crystals in the vanadate-inhibited Ca2+-free (E2) state indeed shows large conformational changes. In the E2 conformation, the cytoplasmic portion of the pump is more compact, implying that Ca2+ (in the absence of nucleotide) loosens interactions between the cytosolic domains. The N and P domains come closer to each other (but the complete closure of the gap between the nucleotide and its target is prevented by vanadate). The smaller A domain rotates by about 90% to bring the critically important sequence TGES into the site of aspartic acid phosphorylation. As predicted by the mutagenesis work, the two Ca2+-binding sites are defined by M4, M5, M6, and M8. Although M5 is straight, extending out of the membrane bilayer to the center of the P domain, M4 and M6 are unwound in the middle to optimize coordination geometry. The two sites are located side by side at a distance of 5.7 Å. Site I is in the space between M5 and M6 with a contribution from M8, the disruption of helix 6 around D800 and G801 allowing T799 and D800 to contribute. Site II is formed almost entirely by carbonyl oxygens on M4 and, again, by D800 of M6. The unwinding of helix M4 between I307 and C310 optimizes the coordination geometry of site II. The two Ca2+-binding sites are stabilized by H bonding between coordinating residues and between residues on other transmembrane helices.

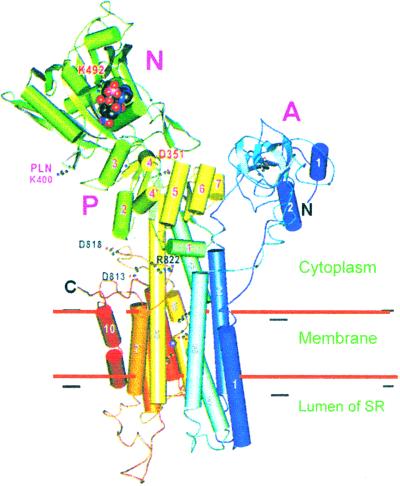

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of the SERCA pump. The structure of the pump is in the Ca2+ bound (E1) form. Details of the structure and of the predicted motions of the cytosolic domains are discussed in the text. Some important residues are indicated, including K400, which is the site of interaction with the regulatory protein phospholamban (PLN).

The path for Ca2+ to the binding site may be a cavity surrounded by M2, M4, and M6, which has a wide cytoplasmic opening. A row of exposed carbonyl oxygens in the unwound parts of M4 and M6 pointing toward the cytoplasm provides a possible hydrophilic path for Ca2+. The Ca2+ exit route could be formed by an area defined by M3, M4, and M5, which also contains a hydrophilic ring of oxygens.

Toyoshima et al. have now succeeded in growing crystals of the Ca2+-free (E2) ATPase that diffract to 3.3-Å resolution. They should soon settle open issues and validate predictions, i.e., the motions of the three cytosolic domains during the transport of Ca2+ and their relationship to the vectorial transport of Ca2+.

Ca2+ Waves and Oscillations

Ca2+ waves initiating in one cell domain and spreading across the cytoplasm were first observed in 1977 in fertilized oocytes (30). Sometimes, they even form complex or spiral waves (31). Repetitive Ca2+ spikes were instead first observed in 1987 in agonist-stimulated hepatocytes (32) and have now been observed in practically every cell type. Mechanisms to explain the propagation of the wave are all based on a positive feedback process, in which the Ca2+ increase at the initial site diffuses to vicinal stores to activate them to release Ca2+, which in turn diffuses further outwards to hit additional stores (the Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release). As discussed by Berridge and Dupont (33), the initial release may occur from a store with high sensitivity to second messenger, e.g., InsP3, after which the involvement of additional stores depends on factors like the Ca2+-diffusion coefficient, the distance between stores, and their sensitivity.

Repetitive spikes arise from the periodic opening of plasma membrane channels (34) (membrane oscillators) or from the periodic emptying of stores (cytosolic oscillator, see ref. 33). The membrane oscillator may actually be linked to the stores, whose emptying activates the capacitative Ca2+ influx. Cytosolic oscillations are distinguished into sinusoidal or baseline spiking. In the former, which may be triggered by fluctuations in the level of InsP3, Ca2+ oscillates around an elevated plateau. In baseline spiking, which in many cells is sensitive to changes in external Ca2+ and second messengers, Ca2+ instead oscillates around the resting level. The intimate mechanism for the initiation of the spiking is still unclear, although a number of plausible mathematical models have been proposed. Berridge et al. (35) have discussed the elementary events that have been called “sparks” or “puffs,” the former reflecting the opening of a group of ryanodine receptors, the latter that of a localized group of InsP3 receptors.

The key question concerning the repetitive transients is their significance, because the “shape” of the Ca2+ signal is an important factor in the modulation of targets. Oscillations are an elegant and efficient way to transmit Ca2+ signals, while at the same time avoiding deleterious sustained elevations of Ca2+. Some Ca2+-sensitive events, e.g., muscle contraction or synaptic transmission, require the rapid delivery of a spatially confined signal of high intensity. Other processes require that Ca2+ be delivered in a form that is not strictly localized and is persistent over a longer period. These processes demand that the signal changes from elementary to global (35) to permit the prolonged exposure of targets to it.

An impressive recent development in the delivery of information using oscillatory patterns is that of Ca2+-modulated gene transcription (see below) (36, 37). The activation of some transcription factors (NFAT) by repetitive Ca2+ spikings induced by the uncaging of InsP3 is more effective than by the sustained Ca2+ increase induced by the long-lasting opening of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels. Experiments modulating either the amplitude or the frequency of the Ca2+ oscillations have shown that transcription factors respond specifically to their amplitude and frequency, e.g., lower frequency oscillations only activate NF-κB.

The Versatility of Ca2+ Signaling: First, Second, or Third Messenger?

Outside signals by first messengers act on plasma membrane receptors inducing the intracellular synthesis (liberation) of second messengers, or activate the enzymatic function of the intracellular portion of the receptors, e.g., receptor tyrosine kinases.

Ca2+ is traditionally described as a second messenger liberated from intracellular stores. However, Ca2+ itself may liberate Ca2+ from these stores, thus adding one step to the signaling cascade, as if the liberated Ca2+ were a “third” messenger. To increase the complexity of the scenario, one could add that activating Ca2+ could come directly from outside rather than from internal stores. Although another second messenger, e.g., nitrogen monoxide, can also diffuse into cells from outside, Ca2+ is clearly special as a signaling agent, because it can also act on the outside of cells as a first messenger. Although this last function is also not unique to Ca2+ (the messenger sphingosine-1-phosphate may also act outside cells), it further emphasizes the unique properties of Ca2+ as a carrier of signals, and will thus be briefly described. The secretion of parathormone (PTH) was known to be sensitive to external Ca2+. A cell surface receptor has been cloned (38) as a seven-transmembrane domain protein with external acidic regions that could bind Ca2+. The receptor acts through phospholipase C (it probably also inhibits adenylyl cyclase) generating InsP3 and increasing cellular Ca2+. This action inhibits the release of PTH. The Ca2+ receptor has been described in other tissues as well, defining Ca2+ as an extracellular “hormone,” possibly specific for cells with special forms of Ca2+ sensitivity, e.g., the release of calciotropic hormones.

The family of messengers acting on Ca2+ stores has recently been enlarged by the discovery of the Ca2+-releasing properties of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP+) (39, 40). Originally described in sea urchin eggs, the Ca2+-releasing ability of NAADP+ has later been extended to other cell types as well (41, 42). In oocytes, NAADP+ liberates Ca2+ from peripheral stores that are linked to extracellular Ca2+ (42). The mobilization of Ca2+ by NAADP+ may have a triggering function on that promoted by InsP3 and cADPr. Another important development on Ca2+-linked second messengers concerns InsP3. Although its production had traditionally been related to the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) by a Gq protein, earlier work (43) had shown phosphorylation of PLC by growth factor tyrosine kinases. The work has now been extended to sperm-induced egg activation (44), showing that a tyrosine kinase pathway related to an Src-family activates PLC [the γ isoform] to produce InsP3 (45).

The Story of Mitochondria and Calcium: Birth, Decline, and Renaissance

In the prologue, the birth of the Ca2+ concept had been traced back to the discovery of Ca2+ transport by SR. The impact of that discovery has indeed been fundamental. However, well before the findings on SR, mitochondria had been shown to be able to transport Ca2+. As early as 1953, Slater and Cleland (46) had shown that heart mitochondria (at that time still called sarcosomes) accumulated large amounts of Ca2+, but had concluded that the process was passive. Two years later, Chance (47) had observed that Ca2+ uncoupled mitochondrial respiration reversibly, the duration of the uncoupled phase being proportional to the amount of Ca2+ added. Ca2+, he concluded, was somehow “consumed” during the uncoupling process. Four years later, Saris (48), having just returned to Finland after a stay in Chance's laboratory, published another remarkable observation in a little-known journal in Finnish. The addition of Ca2+ to isolated mitochondria acidified the medium, suggesting that an exchange of Ca2+ for mitochondrial H+ had taken place. Considering the times, these were sophisticated observations and conclusions, which indicated that the (possible) uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria was related to the activity of the respiratory chain and linked to a transmembrane exchange of positive charges. In a sense, they anticipated the postulates of the chemiosmotic theory, which one decade later was to become dominant in the mitochondrial field. Direct demonstration of active accumulation of Ca2+ by mitochondria was finally provided in 1961–1962 (49, 50). The process became immediately popular, and its properties were rapidly explored in a series of studies. The process was an alternative to ADP phosphorylation in the usage of respiratory energy. Provided that the amount accumulated was limited, Ca2+ was maintained within mitochondria in a dynamic state and could be rapidly returned to the cytosol. However, much larger amounts of Ca2+ could be accumulated if phosphate was also taken up, to precipitate Ca2+ in the matrix as insoluble hydroxyapatite. The energy-dependent uptake, coupled to the release mediated by exchanger systems [of which the most important is an NCX (51)], established an energy-dissipating “mitochondrial Ca2+ cycle” (52).

The early work on mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake had been performed on isolated organelles, i.e., the existence and efficiency of the process in vivo were open to question. Two studies published at the end of the 1960s demonstrated that the process indeed occurred in vivo. Rats were injected with 45Ca2+ and killed at various intervals after the injection. Mitochondria from liver (53) and heart (54) were found to contain most of the radioactivity of the organs, its specific activity being several times higher than in the ER/SR. The preinjection of the rats with uncouplers greatly diminished the amount of 45Ca2+ in mitochondria, showing that the uptake of 45Ca2+ had been energy-dependent, exactly as in the in vitro experiments. Considering the later history of the field (see below), this early finding that mitochondria handled Ca2+ in vivo with great efficiency was remarkable indeed.

These and other findings of the early period have been summarized in a number of detailed reviews (55, 56). At the end of the 1970s, mitochondrial Ca2+ transport was thus generally regarded as important to the control of cellular Ca2+. The process of limited dynamic uptake had one additional essential task, that of regulating a number of Ca2+-dependent matrix dehydrogenases (57). As for the ability to storage massive amounts of insoluble Ca2+ salts without undue disturbances to the free Ca2+ concentration in the matrix, it became universally regarded as a vital device to control situations of temporary cytosolic Ca2+ overload.

This rosy scenario changed rather abruptly at the beginning of the 1980s, because of a series of findings that eventually relegated the process to essential oblivion. One important finding was the low affinity of the mitochondrial uptake system: Under conditions mimicking those of the cytosol, the apparent Km of the uptake system was probably as high as 10–15 μM (58), a value obviously at odds with the cytosolic sub-micromolar Ca2+ concentration established by the newly introduced fluorescent Ca2+ indicators (59). Another finding was the very limited change in cytosolic Ca2+ observed after promoting Ca2+ release from mitochondria, i.e., the mitochondrial Ca2+ content in situ was negligible, much smaller than that in the ER (reviewed in ref. 60). Finally, the discovery that the potent second messenger InsP3 mobilized Ca2+ from the ER (61), soon to be followed by similar observations on other Ca2+-mobilizing agents, dealt the most serious blow to the concept of mitochondria as important actors in the regulation of cellular Ca2+. At the end of the 1980s, one could thus summarize the situation as follows. Mitochondria possessed a sophisticated machinery for transporting Ca2+, but only used it at full capacity where large amounts of Ca2+ mistakenly penetrated into the cell. The futile cycling of Ca2+ across the inner membrane, whose role was that of modulating the matrix dehydrogenases, consumed in reality marginal amounts of energy, because the low affinity of the uptake electrophoretic uniporter kept the working of the cycle at a minimum.

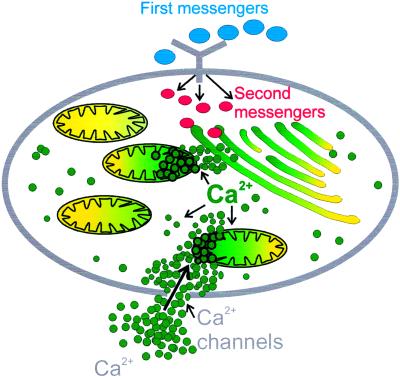

Then, at the beginning of the 1990s, the pendulum swung abruptly in the opposite direction, renewing interest in mitochondria as cellular Ca2+ regulators. The key factor behind the change was the development of indicators, chiefly aequorin (62) specifically targeted to organelles, including mitochondria, which could sense Ca2+ changes in “microdomains” of the cell, rather than in the bulk cytosol. The direct measurement of mitochondrial Ca2+ with targeted aequorin surprisingly showed that the increase of cytosolic Ca2+ induced by InsP3-linked agonists was paralleled by the rapid and reversible increase of mitochondrial Ca2+ (63). It soon became clear that the activation of mitochondrial uptake was the result of the proximity of mitochondria and ER (64). The release of large amounts of Ca2+ by the latter would create “hotspots” at the mouth of the release channels in which the Ca2+ concentration could reach 20–30 μM or more (63, 65, 66) and activate the low affinity mitochondrial uniporter: The microdomain concept is presented in Fig. 4 (in which mitochondria are also seen to sense Ca2+ hotspots at the mouth of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels). Mitochondrial Ca2+ overload would not occur, because the Ca2+ hotspots would rapidly disappear by diffusion to the bulk cytosol, shutting off rapid mitochondrial uptake, and allowing the release exchangers to return matrix Ca2+ to normal levels. Observations of this type have now been made after opening other types of Ca2+ channels in the organelles (the ryanodine receptors, plasma membrane Ca2+ channels). The rapid uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria stimulates mitochondrial metabolism, because of the activation of the Ca2+-sensitive matrix dehydrogenases. It is paralleled by the rapid increase of NADH levels and of mitochondrial ATP production and O2 consumption (67).

Figure 4.

The microdomain concept of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport. Ca2+ penetrating from outside or released from the ER generates restricted domains of high Ca2+ concentration (20 μM or more), adequate to activate the low affinity Ca2+ uptake system of neighboring mitochondria. The Ca2+-releasing agonist shown is InsP3; however, other agonists acting on different channels (e.g., cADPr) also generate the Ca2+ hotspots.

One last aspect of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that is attracting increasing attention is its linkage to apoptosis. Exposure of cells to proapoptotic treatments induces the release of procaspases and caspase cofactors from mitochondria, such as cytochrome c and the apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF). A key role is suggested to be played by the permeability transition pore (PTP), a large unselective channel whose opening is promoted by a number of factors, including the concentration of Ca2+ in the matrix (68, 69). In cells exposed to proapoptotic treatments, the InsP3-promoted uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria induces the opening of PTP and the release of cytochrome c, activating caspases (70).

Calcium in Gene Expression

The transcription factor CREB has been the focus of most of the work on Ca2+ in gene transcription (reviewed in refs. 71 and 72). CREB binds to the cAMP response element (CRE) and to the Ca2+-response element (CARE), and is thus activated by both cAMP and Ca2+. The activation by Ca2+ is linked to CaM kinases, CaMKII phosphorylating both Ser-133 and Ser-144, CaMKIV only the former. Because the phosphorylation of Ser-142 is inhibitory, the activation of CREB is essentially caused by CaMKIV. The transcriptional activation involves the recruitment of the coactivator CBP by CREB phosphorylated on Ser-133 (73), a process that is specifically mediated by nuclear (not by cytosolic) Ca2+ (the control of nuclear Ca2+ is a debated problem that will not be discussed in this review because of space restrictions). Experiments in which the cytosolic and nuclear Ca2+ pools had been separately manipulated (74) have shown that the two pools have distinct roles in the regulation of CREB phosphorylation. Of particular interest to the matter is a very recent report (75) showing that the mode of entry Ca2+ into cortical neurons specifies the response of gene transcription to Ca2+. Influx through L-type channels was especially effective in activating transcription factors CREB and MEF-2. Knockin experiments have shown that an isoleucine-glutamine (“IQ”) motif in the C-terminal portion of the L-channel binds CaM, which acts as a Ca2+ sensor at the mouth of the channel to activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and to convey the transcription activation signal to the nucleus.

The calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin has recently come to the forefront in the field of gene transcription. In T-lymphocytes overexpressing the transcription factor NFAT, it dephosphorylates it in the cytoplasm and transfers it to the nucleus (76). A similar mechanism also functions in other cells, e.g., in yeast the transcription factor cr21p is also translocated to the nucleus in this way (77). In neurons, calcineurin instead becomes activated by Ca2+ penetrating into the cell as a result of brief bursts of synaptic activity and dephosphorylates phosphatase inhibitor I, inhibiting it. This derepresses protein phosphatase I, which dephosphorylates CREB to inhibit transcription (78). Longer lasting stimulations instead maintain CREB in the phosphorylated state, because of the inactivation of calcineurin by oxygen radicals produced under these conditions. Interestingly, calcineurin also regulates the transcription of genes that code for some of the Ca2+ transporters. In cerebellar granule neurons, it mediates the rapid transcriptional down-regulation of specific isoforms of the PMCA pumps and of the NCXs (79, 80).

Ca2+ can also regulate transcription without the intermediation of kinases and phosphatases, as in the case of the EF hand protein DREAM (downstream regulatory element antagonist modulator) (18). The expression of the prodynorphin gene is controlled by the downstream regulatory element (DRE) (81), which binds Ca2+-free DREAM, silencing the gene. When a DREAM tetramer binds Ca2+ it dissociates from DRE, allowing gene transcription to resume. Interestingly, DREAM may also have a role outside the nucleus, because its sequence is nearly identical to that of a neuronal calcium sensor acting on K+ channels and to that of calsenilin, a protein that may be involved in familial Alzheimer's disease.

Calcium and Memory

Memory storage is thought to be linked to processes that change the strength of synaptic transmission, i.e., long-term potentiation (LTP), which is the prolonged increase in transmission efficiency caused by short trains of high frequency stimulation and long-term depression (LTD), which is the sustained decrease of transmission caused by the brief activation of an excitatory pathway. The molecular equivalent of the memory storage process is assumed to be the structural modification of synaptic proteins, among which CaMKII is the most attractive candidate (82). Ca2+ is thus now compellingly suggested to be involved in the mechanism of memory. CaMKII accounts for about 2% of the total hippocampal protein and for about 0.25% of the total brain protein (83). It is the most abundant protein in the postsynaptic density, a structure physically connected to domains of the postsynaptic membrane containing the ionic channels that mediate synaptic transmission. But what makes CaMKII particularly suited to “remember” synaptic events is its autophosphorylation process, which converts it to a functionally modified state that essentially self-perpetuates. Thus, the memory of the synaptic event that has induced the change is retained, even if posttranslational modifications of proteins (in this case, phosphorylation) are reversible, and even if the lifetime of proteins is finite. CaMKII contains 6–12 identical or slightly different monomers, with an autoinhibitory domain positioned at the active site. The domain is removed by CaM, exposing a threonine (Thr-286) that may become phosphorylated by a vicinal monomer made catalytically active by the binding of CaM. Binding is initiated by a Ca2+ spike whose limited duration only permits interaction with some of the subunits. Phosphorylation of Thr-286 greatly increases the affinity of the subunit for CaM, which remains bound at the end of the Ca2+ spike. When it eventually dissociates, the phosphorylated subunit remains active. Each (brief) Ca2+ spike will induce the binding of CaM to an increasing number of subunits: Those that happen to have a vicinal subunit with exposed Thr-286 would phosphorylate it and make it permanently active, irrespective of whether CaM remains bound. If a new spike occurs within 10–20 sec, CaM would bind to some “free” subunits, increasing the chance that those that had retained CaM from the previous transient would now have a vicinal subunit to phosphorylate. Evidently, the key factor is the frequency of the Ca2+ spikes, which must occur at intervals short enough to prevent CaM dissociation. CaMKII thus decodes the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations, transducing it into discrete increases of kinase activity. It is easy to see that the modification that had induced the increase in activity becomes self-perpetuating, overcoming even the turnover of the protein. Newly synthesized subunits could be assembled into the holoenzyme and enter the chain of autophosphorylation events.

The interplay between LTP and CaMKII activity in the hippocampus, which is the main site of memory formation and storage, is now supported by ample evidence. The induction of LTP in hippocampal slices induces Ca2+-independent CaMKII activity (84), whereas the targeted disruption of the CaMKII gene inhibits hippocampal LTP and impairs spatial memory (85, 86). LTP effects have also been reported by overexpressing a mutated form of CaMKII made independent of Ca2+ (Thr-286 → Asp) in restricted regions of the brain of mice whose CaMKII gene had been disrupted (87). In addition to hippocampus, other brain regions are also involved in memory. The processes responsible for memory in cortical networks are less well understood, but also seem to involve LTP and CaMKII. Mice heterozygous for a null mutation of the kinase show normal learning and memory 1–3 days after training in hippocampus-independent tasks, but their memory is severely affected at longer times (10–50 days). These heterozygous mice have normal hippocampal LTP but impaired cortical LTP, indicating that CaMKII controls the consolidation of memory in cortical networks (88).

The interplay between Ca2+ and memory formation and consolidation has recently revealed unexpected complexities. Much excitement now centers on work showing that Ca2+ regulates both LTP and LTD, i.e., it may determine whether memory is strengthened or weakened (89, 90). Ca2+ transients of different height induced in hippocampal neurons by modulating Ca2+ influx with glutamate iontophoresis (90) typically led to LTD in the range 180–500 nM, but induced LTP above 500 nM. Unexpectedly, an intermediate “Ca2+-silent” zone was identified between about 450 and 600 nM in which neither LTD nor LTP were induced. Another recent study has shown that the reduction of postsynaptic Ca2+ influx into hippocampal neurons by partially blocking glutamate receptors converted LTP into LTD (91) and induced loss of input specificity, with LTD appearing at heterosynaptic inputs. Inhibition of Ca2+ release by InsP3 receptors, primarily located in the dendritic shaft and in the soma, converted LTD to LTP and eliminated heterosynaptic LTD, whereas the blockade of ryanodine receptors, which are assumed to operate within the dendritic spines, eliminated only homosynaptic LTD.

Ca2+ Signaling and Disease

Sustained increases of cell Ca2+ to the micromolar range are obviously deleterious to the signaling function of Ca2+. When injurious conditions increase the permeability of the plasma membrane allowing abnormal Ca2+ influx, mitochondria try to cope with the cytosolic Ca2+ overload and may save the cell if the noxious agent is removed rapidly. Otherwise, a point of no return will eventually be reached past which the cell dies because of the activation of Ca2+-dependent hydrolytic enzymes, e.g., proteases. Subtler forms of pathology linked to Ca2+ signaling have also been recognized, e.g., the degeneration of the retina caused by gene defects of neuronal calcium sensors (see above). Calpain has also been involved in human pathology. The disruption of the gene for muscle isoform p94 (calpain III) causes limb girdle muscular distrophy type 2A (92), whereas genetic variations in the gene for another isoform lacking the C-terminal Ca2+-binding domain (calpain 10) favors the onset of type 2 diabetes (93).

Muscle disturbances resulting in prolonged Ca2+ overload have been linked to SERCA pump and ryanodine receptor defects. Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a genetic disease in which inhalational anestethics induce skeletal muscle rigidity and extreme hyperthermia (among other symptoms). A leak in the Ca2+-releasing ryanodine receptor of SR explains the symptoms. Nearly 30 mutations linked to the defect have been described in the RYR1 gene (94, 95). Central core disease (CCD) is a myopathy usually associated with MH, characterized by hypotonia, proximal muscle weakness, and lack of oxidative or phosphorylase activity in the central “core” of type I and type II muscle fibers. CCD is also linked to mutations in the RYR1 gene (95), clustered in the same regions where the MH mutations also cluster. The chronic depletion of the SR Ca2+ store because of the leakiness of the RYR1 receptor may explain the muscle weakness and leads to damage to the core of the fibers where compensatory mechanisms cannot maintain the homeostasis of Ca2+. Brody's (96) disease, instead, is characterized by muscle cramping and exercise-induced impairment of relaxation. In the cases linked to defects in the gene for SERCA1 (which are not all of the cases), it is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The defects lead to the loss of SERCA1 activity (97). The Ca2+ concentration in the sarcoplasm may be normal, but the time required to restore it to the normal level after induced release may increase severalfold (98). Analysis of the SERCA1 gene has revealed either premature stop codons or deleterious point mutations in about half of the affected families (99, 100).

Defects in the genes for the four isoforms of the PMCA pumps have also been described. PMCA2 and 3 are restricted to nervous cells, e.g., PMCA2 is very abundant in the outer hair cells of the organ of Corti. Recent work on knockout mice (101) and on mice with a phenotype characterized by hearing defects that could be models for hereditary hearing loss in humans (102, 103) has revealed PMCA2 defects. One is caused by an E → K mutation affecting a conserved residue in transmembrane domain 4 that could be a component of the transprotein Ca2+ path. Other defects are a G → S mutation at a highly conserved location and a 2-bp replacement that produces a truncated pump.

Concluding Remarks

Ca2+ has come a long way from the old days of London tap water and is now known to control a myriad of key cell processes. The succinct survey above has followed the development of the Ca2+ concept up to its present stage of explosive growth, discussing the developments that I considered as the most significant. Other topics, e.g., fertilization, apoptosis, protein phosphorylation, genetic Ca2+ channelopathies, and the matter of nuclear Ca2+ control, would have certainly been covered if space had permitted. Hopefully, this minireview will be a stimulus to read more about Ca2+.

Acknowledgments

The help of Drs. D. Bano and M. Brini, in the preparation of the figures, and of Ms. N. Homutescu, in the typing and processing of the manuscript, is gratefully acknowledged. The original work described has been supported by contributions from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Human Frontier Science Program Organization, the Italian Ministry of University and Scientific Research (PRIN1998 and PRIN2000), the National Research Council of Italy (Target Project on Biotechnology), and by the Armenise-Harvard Foundation.

Abbreviations

- ER/SR

endo(sarco)plasmic reticulum

- InsP3

inositol 1-4-5 trisphosphate

- cADPr

cyclic ADP ribose

- PMCA

plasma membrane Ca2+ pump

- SERCA

ER/SR Ca2+ pump

- NCX

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- LTD

long-term depression

- CaM

calmodulin

- CRE

cAMP response element

References

- 1.Weber A. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:2764–2769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebashi S. J Biochem. 1961;50:236–244. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebashi S, Lipmann F. J Cell Biol. 1962;14:389–400. doi: 10.1083/jcb.14.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasselbach W, Makinose M. Biochem Z. 1961;333:518–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebashi S, Kodama A. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1965;58:107–108. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a128157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarzenbach v G, Ackermann H. Helv Chim Acta. 1954;30:1798–1804. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozler E. J Gen Physiol. 1954;38:149–159. doi: 10.1085/jgp.38.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carafoli E, Santella L, Branca D, Brini M. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;36:107–260. doi: 10.1080/20014091074183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berridge M J. Nature (London) 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carafoli E. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:395–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams R J P. In: Calcium As a Cellular Regulator. Carafoli E, Klee C, editors. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1999. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kretsinger R H. Nat New Biol. 1972;240:85–88. doi: 10.1038/newbio240085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosfield C M, Elce J S, Davies P L, Jia Z. EMBO J. 1999;18:6880–6889. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strobl S, Fernandez-Catalan C, Braun M, Huber R, Masumoto H, Nakagawa K, Irie A, Sorimachi H, Bourenkow G, Bartunik H, Suzuki K, Bode W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:588–592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moldoveanu, T., Hosfield, C. M., Lim, D., Elce, J. S., Jia, Z. & Davies, P. L. (2002), submitted.

- 16.Scharff, E. I., Koepke, J., Fritzsch, G., Lücke, C. & Rüterjans, H. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Burgoyne R D, Weiss J L. Biochem J. 2001;353:1–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrión A M, Link W A, Ledo F, Mellström B, Naranjo J R. Nature (London) 1999;398:80–84. doi: 10.1038/18044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buxbaum J D, Choi E K, Luo Y, Lilliehook C, Crowley A C, Merriam D E, Wasco W. Nat Med. 1998;4:1177–1181. doi: 10.1038/2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokal I, Li N, Surgucheva I, Warren M J, Payne A M, Bhattacharya S S, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Mol Cell. 1998;2:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dizhoor A M, Boikov S G, Olshevskaya E V. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17311–17314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sokal I, Li N, Verlinde C L, Haeseleer F, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1498:233–251. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polans A S, Buczylko J, Crabb J, Palczewski K. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:981–989. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.5.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polans A S, Witkowska D, Haley T L, Amundson D, Baizer L, Adamus G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9176–9180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toyoshima C, Nakasako M, Nomura H, Ogawa H. Nature (London) 2000;405:647–655. doi: 10.1038/35015017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacLennan D H. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:4508–4518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen P L, Carafoli E. Trends Biochem Sci. 1987;12:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke D M, Loo T W, Inesi G, MacLennan D H. Nature (London) 1989;339:476–478. doi: 10.1038/339476a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang S, Ehlers M D, Berhardt J P, Su C T, Huganir R L. Neuron. 1998;21:443–453. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80553-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridgway E B, Gilkey J C, Jaffe L F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:623–627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amundson J, Clapham D. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1993;3:375–382. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90131-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woods N M, Cuthbertson K S, Cobbold P H. Cell Calcium. 1987;8:79–100. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(87)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berridge M J, Dupont G. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:267–274. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laskey R E, Adams D J, Cannell M, Van Breemen C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1690–1694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berridge M, Lipp P, Bootman M. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R157–R159. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolmetsch R E, Lewis R S, Goodnow C C, Healy J I. Nature (London) 1997;286:855–858. doi: 10.1038/386855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Llopis J, Whitney M, Zlokarnik G, Tsien R Y. Nature (London) 1998;392:936–941. doi: 10.1038/31965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown E M, Gamba G, Riccardi D, Lombardi M, Butters R, Kifor O, Sun A, Hediger M A, Lytton J, Hebert S C. Nature (London) 1993;366:575–580. doi: 10.1038/366575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H C, Aarhus R. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2152–2157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Genazzani A A, Galione A. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:108–110. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(96)01036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cancela J M, Churchill G C, Galione A. Nature (London) 1999;398:74–76. doi: 10.1038/18032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santella L, Kyozuka K, Genazzani A A, De Riso L, Carafoli E. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8301–8306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishibe S, Wahl M I, Rhee S G, Carpenter G. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10335–10338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shilling F M, Carroll D J, Muslin A J, Escobedo J A, Williams L T, Jaffe L A. Dev Biol. 1994;162:590–599. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giusti A F, Xu W, Hinkle B, Terasaki M, Jaffe L A. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16788–16794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slater E C, Cleland K W. Biochem J. 1953;55:566–580. doi: 10.1042/bj0550566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chance B. In: Proc. 3rd Intern. Congr. Biochem. Brussels. Liébecq C, editor. New York: Academic; 1955. pp. 300–304. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saris N E. Finska Kemistsamfundets Medd. 1959;68:98–107. [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Luca H F, Engstrom G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1961;47:1744–1750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.47.11.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasington F D, Murphy J V. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:2670–2672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carafoli E, Tiozzo R, Lugli G, Crovetti F, Kratzing C. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1974;6:361–371. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(74)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carafoli E. FEBS Lett. 1979;104:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)81073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carafoli E. J Gen Physiol. 1967;50:1849–1864. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.7.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patriarca P, Carafoli E. J Cell Physiol. 1968;72:29–38. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040720106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lehninger A L, Carafoli E, Rossi C S. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1967;29:259–320. doi: 10.1002/9780470122747.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carafoli E. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1982;151:461–472. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4259-5_51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCormack J G, Denton R M. Biochem J. 1980;190:95–105. doi: 10.1042/bj1900095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scarpa A, Graziotti P. J Gen Physiol. 1973;62:756–772. doi: 10.1085/jgp.62.6.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien R Y. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pozzan T, Rizzuto R, Volpe P, Meldolesi J. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:595–636. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Streb H, Irvine R F, Berridge M J, Schulz I. Nature (London) 1983;306:67–69. doi: 10.1038/306067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rizzuto R, Simpson A W M, Brini M, Pozzan T. Nature (London) 1992;358:325–328. doi: 10.1038/358325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rizzuto R, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Science. 1993;262:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.8235595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay F S, Fogarty K E, Lifshitz L M, Tuft R A, Pozzan T. Science. 1998;280:1763–1766. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Montero M, Alonso M T, Carnicero E, Cuchillo-Ibanez I, Albillos A, Garcia A G, Garcia-Sancho J, Alvarez A. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:57–61. doi: 10.1038/35000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hajnoczky G, Robb-Gaspers L D, Seitz M B, Thomas A P. Cell. 1995;82:415–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jouaville L S, Pinton P, Bastianutto C, Rutter G A, Rizzuto R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13807–13812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vieira H L A, Kroemer G. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:971–976. doi: 10.1007/s000180050486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crompton M. Biochem J. 1999;341:233–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Szalai G, Krishnamurthy R, Hajnoczky G. EMBO J. 1999;18:6349–6361. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bading H, Ginty D D, Greenberg M E. Science. 1993;260:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.8097060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santella L, Carafoli E. FASEB J. 1997;11:1091–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chawla S, Hardingham G E, Quinn D R, Bading H. Science. 1998;281:1505–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hardingham G E, Chawla S, Johnson C M, Bading H. Nature (London) 1997;385:260–265. doi: 10.1038/385260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dolmetsch R E, Pajvani U, Fife K, Spotts J M, Greenberg M E. Science. 2001;294:333–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1063395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shibasaki F, Price E R, Milan D, McKeon F. Nature (London) 1996;382:370–373. doi: 10.1038/382370a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stathopoulos A M, Cyert M S. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3432–3444. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bito H, Deisseroth K, Tsien R W. Cell. 1996;87:1203–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81816-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guerini D, Wang X, Li L, Genazzani A, Carafoli E. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3706–3712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li L, Guerini D, Carafoli E. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20903–20910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carríon A M, Mellström B, Naranjo J R. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6921–6929. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.6921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.De Konick P, Schulman H. Science. 1998;279:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Erondu N E, Kennedy M B. J Neurosci. 1985;5:3270–3277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-12-03270.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fukunaga K, Stoppini L, Miyamoto E, Muller D. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7863–7867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Silva A J, Paylor R, Wehner J M, Tonegawa S. Science. 1992;257:206–211. doi: 10.1126/science.1321493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Silva A J, Stevens C F, Tonegawa S, Wang Y. Science. 1992;257:201–206. doi: 10.1126/science.1378648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mayford M, Bach M E, Huang Y-Y, Wang L, Hawkins R D, Kandel E R. Science. 1996;274:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Frankland P W, O'Brien C, Ohno M, Kirkwood A, Silva A J. Nature (London) 2001;411:309–313. doi: 10.1038/35077089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cormier R J, Greenwood A C, Connor J A. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:399–406. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cho K, Aggleton J P, Brown M W, Bashir Z I. J Physiol. 2001;532:4594–4566. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0459f.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nishiyama M, Hong K, Mikoshiba K, Poo M, Kato K. Nature (London) 2000;408:584–588. doi: 10.1038/35046067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Richard I, Broux O, Allamand V, Fougerousse F, Chinnikulchai N, Bourg N, Brenguier L, Devaud C, Pasturaud P, Roudaut C, et al. Cell. 1995;81:27–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Horikawa Y, Oda N, Cox N J, Li X, Orho-Melander M, Hara M, Hinokio Y, Lindner T H, Mashima H, Schwarz P E, et al. Nat Genet. 2000;26:163–175. doi: 10.1038/79876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lynch P J, Tong J, Lehane M, Mallet A, Giblin L, Heffron J J, Vaughan P, Zafra G, MacLennan D H, McCarthy T V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4164–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Loke J, MacLennan D H. Am J Med. 1998;104:470–486. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brody I A. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:187–192. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196907242810403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karpati G, Charuk J, Carpenter S, Jablecki C, Holland P. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:38–49. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Benders A A, Veerkamp J H, Oosterhof A, Jongen P J, Bindels R J, Smit L M, Busch H F, Wevers R A. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:741–748. doi: 10.1172/JCI117393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Odermatt A, Taschner P E, Khanna V K, Busch H F, Karpati G, Jablecki C K, Breuning M H, MacLennan D H. Nat Genet. 1996;14:191–194. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang Y, Fujii J, Phillips M S, Chen H S, Karpati G, Yee W C, Schrank B, Cornblath D R, Boylan K B, MacLennan D H. Genomics. 1995;30:415–424. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kozel P J, Friedman R A, Erway L C, Yamoah E N, Liu L H, Riddle T, Duffy J J, Doetschman T, Miller M L, Cardell E L, Shull G E. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18693–18696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Takahashi K, Kitamura K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:773–778. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Street V A, McKee-Johnson J W, Fonseca R C, Tempel B L, Noben-Trauth K. Nat Genet. 1998;19:390–394. doi: 10.1038/1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]