Abstract

Dietary nutrients are an important determinant of gut microbial composition (Asnicar et al, Nat Med 27:321–332, 2021; Arifuzzaman. et al, Nature 611:578–584, 2022; Bolte. et al, Gut 70:1287–1298, 2021). Commensal bacteria compete and cross-feed on host-derived nutrients to maintain stable gut microbial communities (Kolodziejczyk. et al, Nat Rev Microbiol. 17:742–753, 2019; Ma. et al, Gut Microbes 12:1785252, 2020). However, the changes to the gut bacteria induced by fasting are not well-defined. Here, we propose a powerful method to selectively and effectively increase specific gut bacteria by combining fasting and administration of microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs). Fasting alters the gut microbial community structure, and the fasting + MAC intervention has profound effects on the gut microbiome with increased specific bacteria and fecal IgA levels than MAC administration alone. The changes in gut microbiota composition are specific to the type of MAC administered. We identified the most effective protocol to combine with fasting + MAC to increase the levels of specific bacteria such as Bifidobacterium. Overall, the integrating fasting with MACs effectively alters the gut microbiome, suggesting that fasting can prepare the environment for gut microbial modulation by MACs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-025-04140-y.

Keywords: Fasting, Microbiota-accessible carbohydrates, Fructo-oligosaccharides, 6ʹ-sialyl lactose, Paramylon, Human milk oligosaccharides, IgA, Gut microbiota

Introduction

The gut microbiome can be conceptualized as a superorganism comprising trillions of diverse microorganisms [1, 2]. The molecules and metabolites associated with the gut microbiome impact the human inflammatory state [3, 4] metabolism [5] and cognition [6]. As the diet shapes the gut microbial structure [3, 5, 7] dietary interventions are conducted to obtain health benefits.

Dietary fiber can alter the gut microbiome composition and influence the types and activities of metabolites produced [8, 9]. Dietary fibers are complex carbohydrates from plants that are resistant to digestion by humans, and are functionally classified as microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs) because these are consumed by gut bacteria [10]. Gut bacteria ferment MACs into metabolites, which serve as a primary energy source and contribute to host health by supporting intestinal homeostasis and suppressing disease development [9, 11]. The capacity to utilize various types of MACs varies among gut bacteria, leading to differing impacts on the gut microbiome and host physiology [11, 12]. Thus, MACs can serve as “gut microbiota modulators” and enhance host physiological functions based on individual conditions.

The gut microbiota are resilient, and a greater diversity of gut bacteria results in microbiome stability and resistance to dietary changes [13]. Additionally, the gut microbiota contributes to the complexity and stability of the gut ecosystem by competing and sharing nutrients in the limited intestinal environment [14]. As the robustness of gut bacteria is not easily disrupted [13] dietary interventions including MACs have struggled to alter the gut microbiome significantly [13, 15–17].

Substantial studies have shown that fasting can alter the gut microbiome composition and influence the physiological state of the host [18–23]. Fasting can disrupt the stability of gut bacteria, resulting in a distinct microbiome that can last for several months after the end of the fasting period [24, 25]. Therefore, we hypothesized that fasting can make the gut microbiome less resilient, enabling effective changes in the gut microbiome by MACs. However, the effects of fasting on gut bacteria depend on the specific type of fasting employed—such as intermittent or long-term fasting—and the existence of underlying health conditions, as shown by studies in mouse models [18–21, 26]. Moreover, the changes to the gut bacteria induced by fasting are not well-defined.

In this study, we demonstrated that fasting induces significant changes in gut microbiota structure and that administration of MACs during fasting induces selective bacterial growth and host IgA production within a short time frame.

Results

Fasting affects the gut microbial structure

We first examined how a 36-hour fasting period influences the gut microbial composition in C57BL/6J mice. The mice that underwent fasting showed a significantly altered gut microbial community based on β-diversity analysis with no notable differences in α-diversity (Fig. 1a and b). Fasting increased the relative abundance of Bacteroidota and Pseudomonadota, whereas the abundance of Bacillota decreased (Fig. 1c and d). In particular, the relative abundance of Lactobacillus was dramatically decreased in the fasting group (Fig. 1d). In addition, the relative abundance of Ruminococceae UCG-014, Ruminiclostridium 5, and the uncultured bacterium Canditatus Saccharibacteria was significantly decreased, and the abundance of the [Eubacterium] coprostanoligenes group and Alistipes was significantly increased after fasting (Fig. 1d). A comparison of the fold change for the number of each bacterial species before and after fasting revealed the dynamics of bacterial modulation. Blautia and Ruminococcaceae UCG-010, from the phylum Bacillota, showed a significant decrease. Conversely, the abundance of several bacteria, including Alloprevotella, Alistipes, and Escherichia-Shigella, showed an increase (Fig. 1e). Fasting drastically remodeled gut microbial structure through decreased numbers of Bacillota and an increase in abundance of Bacteroidota and Pseudomonadota. Thus, fasting induces rapid remodeling of the gut microbial structure.

Fig. 1.

Fasting affects the gut microbial structure. a Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) plot based on UniFrac distance shows differences in the microbial community structure in different treatment groups. Each symbol and color indicate the timepoint and group, respectively. b Violin plot showing α-diversity after 36 h of fasting. Left; Shannon Index, center; Chao1, right; Faith’s phylogenetic diversity. c Stacked bar plot showing the microbiota composition before and after fasting. Each gradient color indicates the representative bacterial phylum and genera. d Representative bacterial genera that exhibited significant differences in enrichment. e Heatmap showing the comparison of bacterial enrichment comparing an ad libitum diet vs. fasting. Plots represent the mean ± S.E.M. Pairwise Palmanova, ** P < 0.01 (a). Welch’s t-test (b, c, e). *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05

Combination of fasting and MACs drastically promoted the growth of specific gut bacteria

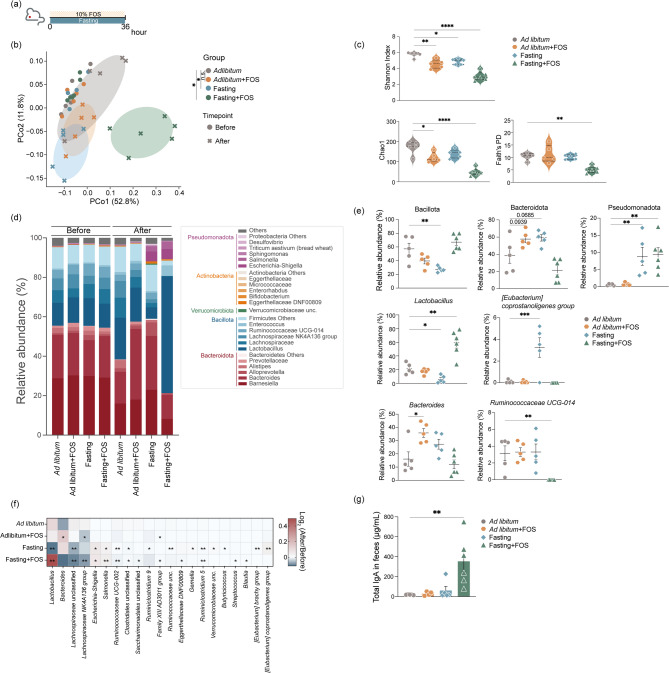

Lactobacillus were responsive to the fasting and the nutritional state in the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 1d and e) [27–29]. Furthermore, fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) can be utilized by Lactobacillus and promote their growth [30–33]. Therefore, we investigated how fasting impacts the levels of Lactobacillus with FOS administration. To assess the influence of host genetic background on the gut microbiota response to fasting, BALB/cAJcl mice were treated with 10% FOS and fasted for 36 h (Fig. 2a). Fasting or FOS conditions changed the gut microbiota composition and reduced α-diversity. However, the combination of fasting + FOS drastically altered gut microbial community composition, with a drastic reduction in α-diversity of the Fasting + FOS group compared with the control group (Fig. 2b and c). Consistent with the effects of fasting on C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 1c and d), abundances of bacteria from the phyla Bacteroidota and Pseudomonadota were increased, with a concomitant decrease in Bacillota (Fig. 2d). Notably, the relative abundance of Lactobacillus showed no increase in the Ad libitum + FOS group but was drastically increased in the Fasting + FOS group (Fig. 2d–f). In contrast, the relative abundance of Bacteroides was increased in the Ad libitum + FOS group but not in the Fasting + FOS group. Moreover, the combination of fasting + FOS diminished the increase in the [Eubacterium] coprostanoligenes group that was observed after fasting and abolished the relative abundance of Ruminococcaecae UCG-014 observed in other groups (Fig. 2e and f). FOS intake and the presence of Lactobacillus is associated with enhanced IgA production in gastrointestinal tracts [34–36] and IgA binding to bacteria plays a crucial role in regulating bacterial colonization and metabolic functions [37–40]. Therefore, we evaluated fecal IgA levels in mice. In the Fasting + FOS group, total IgA levels in feces were upregulated 18-fold (Fig. 2g), indicating that fasting enhances the responsiveness of the gut microbiota to FOS, increasing specific bacteria and gut IgA levels.

Fig. 2.

Fasting + MAC intervention drastically alters the gut microbiome structure. a Diagram illustrating the protocol for prebiotic administration during fasting. b Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) plot based on UniFrac distance showing differences in the microbial community structure. Each symbol and color indicate the timepoint and group, respectively. c Violin plot showing α-diversity after 36 h of fasting. Upper left; Shannon Index, lower left; Chao1, lower right; Faith’s phylogenetic diversity. d Stacked bar plot showing the microbiota composition before and after fasting. Each gradient color indicates the representative bacterial phylum and genera. e Representative bacterial genera that exhibited significant differences. f Heatmap showing the comparison of bacterial behavior by fasting and prebiotics. g Bar plot showing the total IgA antibody levels in feces. Plots represent the mean ± S.E.M. Pairwise Palmanova, * P < 0.05 (b). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. **** P < 0.0001, *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05 (c, e-g)

Subsequently, we assessed whether fasting could amplify the microbiota-modulating effects of various MACs. We first tested the effects of galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) and α-cyclodextrin (α-Cyd), which are known to promote the growth of specific gut bacteria [31, 41–44]. Administration of GOS and α-Cyd during fasting differentially altered the murine gut microbiota composition, including increased relative abundance of Lactobacillus, Erysipelatoclostridium, and Bacteroides (Supplementary Fig. 1). We also investigated the effects of combining fasting and human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) administration. HMOs such as 2’-fucosyllactose (2FL), 3’-sialyllactose (3SL), and 6’-sialyllactose (6SL) promote the colonization of specific gut bacterial populations and shape the infant gut microbiota [45–51]. Compared with the effects of other MACs, the intake of HMOs—including 2’-FL, 3’-SL, 6’-SL, and their cocktail—altered the abundance of multiple bacterial taxa. This was characterized by increases in the relative abundance of Atopobiaceae, Lactobacillales, Parabacteroides, Bacteroides, and Bifidobacterium, along with suppression of the increase in the that of Verrucomicrobiaceae and Eggerthellaceae DNF00809 (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Thus, the combination of fasting + MACs induced marked changes in the gut microbiota, and these effects appear to be dependent on the structural characteristics of the administered oligosaccharides, such as FOS, GOS, α-CYD, 2’-FL, 3’-SL, and 6’-SL.

Integrated regimen of fasting + MACs robustly enhanced gut microbial modulation effects

We then sought to determine the optimal strategy for combining fasting with MAC administration to promote the enrichment of specific gut bacterial taxa. There are several reports showing that Bifidobacterium has various benefits in maintaining human health and is often used to induce prebiotic effects on the gut microbiota [52, 53]. We evaluated the change in relative abundance of Bifidobacterium using the combination treatment of fasting and FOS administration. The human gut microbiome can efficiently degrade inulin/FOS within 24 h [54] and FOS supplementation increases Bifidobacterium growth within 24–48 h [55, 56]. In addition, a high dose of FOS significantly increases Bifidobacterium levels in mouse feces [57, 58].

To determine the most effective FOS administration pattern and volume, we tested several dose patterns and volumes over a 36-h interval (Fig. 3a). Administration of FOS every 12 h within 24 h of the onset of a 36-hour fasting was the most effective treatment pattern that increased the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium (Fig. 3b). Analysis of the most effective fasting duration (Fig. 3c) showed that fasting for 36 h resulted in a higher increase in the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium (Fig. 3d). These results indicate that FOS administration promotes Bifidobacterium growth when taken three times within 24 h, with each dose taken every 12 h. The increase is particularly effective when FOS was administered during a 36-h fast.

Fig. 3.

Fasting + MAC approach effectively increases Bifidobacterium levels in the gut of mice. a Diagram illustrating prebiotic administration strategies employed in the study. b Relative abundance of Bifidobacterium after fasting. c Illustration of prebiotic administration protocols of various durations with an ad libitum diet or fasting. d Relative abundance of Bifidobacterium after fasting. Plots represent the mean ± S.E.M. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. **** P < 0.0001 *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05 (b, d)

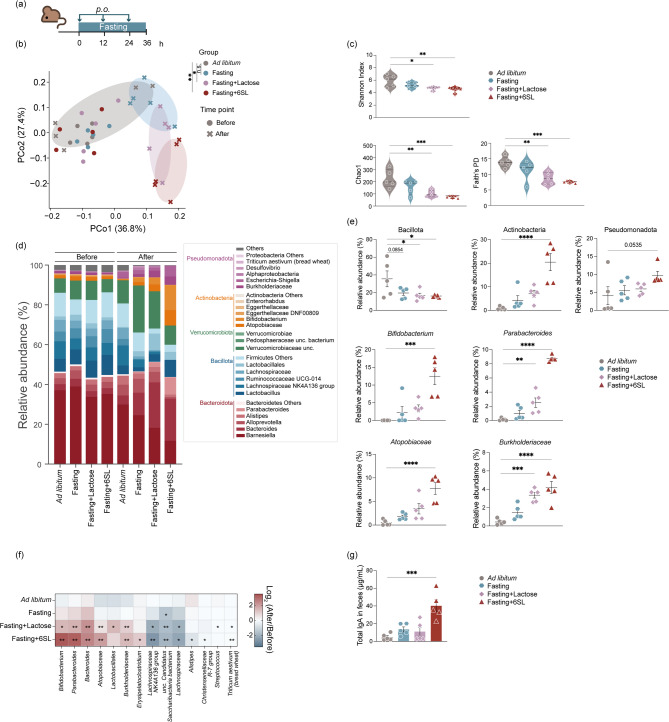

To evaluate whether the treatment regimen described above enhanced the growth of Bifidobacterium after administration of other oligosaccharides, C57BL/6J mice were fed 6SL and fasted for 36 h (Fig. 4a). The administration of 6SL during fasting strongly modulated the gut microbial community composition and significantly decreased the α-diversity (Fig. 4b and c). Administration of 6SL increased the relative abundance of Actinobacteria and Pseudomonadota (Fig. 4d). In particular, the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium, Parabacteroides, Atopobiaceae, and Burkholderiaceae were significantly increased in the fasting + lactose group and in the fasting + 6SL group (Fig. 4e and f). Bifidobacterium stimulate the secretion of mucosal IgA in the gastrointestinal tract [59–62]. Administration of 6SL during fasting resulted in a significant increase in total fecal IgA levels (Fig. 4e and f). Overall, our results indicate that the regimen of fasting and MAC administration has a marked effect on gut microbiota structure and promotes selective growth of gut bacteria.

Fig. 4.

Fasting HMO intervention changes the structure of the gut microbiome. a Diagram illustrating the protocol for prebiotic administration during fasting. b PCoA plot based on UniFrac distances showing differences in the microbial community structure. Each symbol and color indicate the timepoint and group, respectively. 6’-sialyl lactose; 6SL (c) Violin plot showing α-diversity after 36 h of fasting. Upper left; Shannon Index, lower left; Chao1, lower right; Faith’s phylogenetic diversity. d Stacked bar plot showing the microbiota composition before and after fasting. Each gradient color indicates representative bacterial phylum and genera. e Representative bacterial genera that exhibited significant differences in enrichment. f Heatmap showing the comparison of bacterial behavior between the fasting and prebiotic administration groups. g Bar plot showing the total IgA antibody levels in feces. Plots represent the mean ± S.E.M. Pairwise Palmanova, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05 (b). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. **** P < 0.0001 *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05 (c, e–g)

Fasting with paramylon administration increases specific gut bacterial levels and fecal IgA production

To explore whether fasting can potentiate the microbiota effects of saccharides structurally distinct from conventional oligosaccharides, we focused on β-glucans and their impact on the gut microbiota. β-Glucans are non-digestible polysaccharides found in sources such as yeast, grains, and fungi, and have been reported to modulate the gut microbiome, stimulate immune responses, and improve insulin sensitivity [63–66]. Among them, paramylon—a β−1,3-glucan derived from the microalga Euglena gracilis, accounting for 30–40% of its cellular content—is a commercially available bioactive compound with potential to influence both gut microbial composition and host physiology [66, 67].

We tested the effects of Paramylon and Euglena administration on the gut microbiota in C57BL/6J mice during fasting (Fig. 5a). Mice were administered a dose equivalent of 10 mg/kg body weight which was calculated based on the recommended human dosage for glucan dietary supplements [66]. In contrast to the optimized protocol used in Fig. 3, we applied a single administration of paramylon or Euglena followed by 36 h of fasting. This design was intended to test whether fasting could enhance the microbiota-modulating effects of these polysaccharides within a short timeframe, as compared to previous studies requiring daily administration over 45 days [66]. Fasting dramatically altered the gut microbial community composition (Fig. 5b). Administration of Paramylon during fasting had a modest effect on the gut microbial community composition compared to fasting alone (Fig. 5b). Notably, the administration of Euglena without fasting resulted in increased α-diversity, whereas the combination of Paramylon and fasting decreased α-diversity (Fig. 5c). The administration of Paramylon during fasting increased the relative abundance of the Bacteroides and the [Eubacterium] coprostanoligenes group, whereas Euglena and Paramylon intake decreased the relative abundance of Lactobacillus (Figs. 5e-f). Euglena administration resulted in increased gut bacteria such as Oscillibacter, Ruminiclostridium 5, Ruminiclostridium 9, uncultured Ruminococcaeceae, and Ruminococcaeceae UCG-014. However, this increase was abolished due to fasting (Fig. 5f). Additionally, Bacteroides induce IgA production [68, 69] and fasting with Paramylon intake significantly upregulated total fecal IgA levels (Fig. 5g). These findings suggest that, in addition to oligosaccharides, fasting can potentiate the microbiota-modulating effects of polysaccharides such as paramylon, even within a short intervention period, as reflected by alterations in bacterial composition and diversity.

Fig. 5.

Fasting with β-Glucan (Pramylon) administration effectively increased specific gut bacteria and fecal IgA levels. a Diagram illustrating the protocol for prebiotic administration during 36 h of fasting. b PCoA plot based on UniFrac distances showing differences in the microbial community structure. Each symbol and color indicate the timepoint and group, respectively. c Violin plot showing α-diversity after 36 h of fasting. Upper left; Shannon Index, lower left; Chao1, lower right; Faith’s phylogenetic diversity. d Stacked bar plot showing the microbiota composition before and after fasting. Each gradation color indicates the representative bacterial phylum and genera, respectively. e Representative bacterial genera that exhibited significant differences. f Heatmap showing the comparison of bacterial behavior by fasting and prebiotics. g Bar plot showing the total IgA antibody levels in feces. Plots represent the mean ± S.E.M. Pairwise Palmanova, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05 (a). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. **** P < 0.0001 *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05 (c, e-g)

Discussion

In this study, we showed that fasting induces significant changes in gut microbial structures within a short period. Furthermore, the combination of fasting with MAC administration influenced the trajectory of the microbial community changes by promoting the selective growth of specific gut microbes. In addition, the direction of these microbial shifts was dependent on the type of MAC administered. We also observed a significant increase in fecal IgA production in the fasting + MAC group of mice. These results suggest that our approach is promising for altering gut microbial structure and selectively enhancing beneficial bacteria.

Nutritional exposure is a significant factor influencing gut microbial composition, and the gut microbiota also exhibits stability in response to external perturbations [13]. The response of gut microbiota or their metabolic functions to MACs, such as prebiotics and dietary fiber, can manifest within a few days to several months. However, the response time varies considerably among individuals, depending on their baseline and previous dietary habits [54, 60]. The gastrointestinal nutritional status, such as that in oligotrophic environments, has a profound impact on the colonization of gut bacteria and their metabolic functions, influencing the responses to MACs [28, 70]. Fasting has been shown to remodel the gut microbial structure [18–23]. Indeed, the gut microbiome changes that result due to fasting can be maintained for several months compared to pre-intervention levels [24, 25]. Consistent with previous findings [21, 25, 71, 72] our results demonstrated that fasting alters gut microbial communities, decreasing the relative abundance of Bacillota while increasing that of Pseudomonadota, independent of the mouse strains. Additionally, in line with previous studies [27–29] Lactobacillus species exhibit sensitivity to the host’s nutritional status. Under malnourished conditions, the expression of surface glycans on Lactobacillus is reduced [28] which in turn diminishes their interaction with secretory IgA and impairs intestinal colonization [28]. These mechanisms may partly explain the observed decline in Lactobacillus populations during fasting. However, it remains unclear whether these fasting-induced changes confer beneficial effects on human health. Furthermore, gut microbiota exhibits differential responses to MACs in both oligotrophic and eutrophic conditions [70]. Based on our analyses, the administration of prebiotics during fasting significantly enhances the selective growth of beneficial bacteria within a short time frame. Further investigation of the minimal dose required to achieve the observed effects will strengthen a major advantage of our strategy. Different oligosaccharides exerted distinct effects on bacterial growth, particularly for beneficial species such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Bacteroides. The increase in the levels of these beneficial bacteria, in conjunction with fasting + MACs, were comparable or more pronounced than those documented in previous studies where MACs were administered over two weeks to one month [32, 43, 44, 49, 50, 57, 73, 74].

Several studies have reported that the gut microbiota tends to gradually revert to its baseline composition after the cessation of prebiotic interventions [74–76]. Recent evidence also suggests that prior dietary exposure can condition the microbiota to more efficiently utilize specific prebiotics, such as inulin and FOS, during subsequent interventions, thereby enhancing SCFA production [54]. Although the long-term stability of microbial shifts induced by our approach remains to be determined, intermittent or lower-dose supplementation may help maintain the desired microbial profiles.

Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides utilize human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) [49, 77–80] which play a critical role in the maturation and stabilization of the human gut microbiome [81] and facilitate recovery after antibiotic treatment [80]. The colonization of Bifidobacterium or Bacteroides by fasting + HMOs may promote the stabilization and maintenance of the remodeled gut microbiota. In our results, the Fasting + Lactose intervention did not lead to a Bifidobacterium increase comparable to that seen in the Fasting + 6’-SL group, despite the lactose-utilizing capacity of many Bifidobacterium strains. This may be due to the broader utilization of lactose by various gut microbes [51, 82, 83] whereas only specific Bifidobacterium strains can metabolize HMOs such as 6’-SL. In addition, 6’-SL has been shown to promote Bifidobacterium growth through epithelial adhesion and microbial cross-feeding [84–86]. These mechanisms may explain the differential responses observed. Further, we identified genera such as Parabacteroides, and bacterial families such as Atopobiaceae and Burkholderiaceae, that increased abundance after fasting and HMO administration. However, it remains unclear whether these bacteria possess the necessary enzymes for HMO degradation.

The increase in Bacteroides by α-Cyd treatment is associated with higher levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and upregulation of gluconeogenesis-associated genes in the liver, contributing to anti-obesity effects and improved endurance [43, 44]. Due to its complex structure, paramylon may require more time to be metabolized compared to simpler oligosaccharides [64] which may explain its relatively delayed impact on gut bacterial composition. Nonetheless, the increase in Bacteroides observed following fasting combined with paramylon intake appeared qualitatively similar to that reported after prolonged daily administration of paramylon [66].

Follow-up studies are needed to determine how specific bacterial taxa, such as Bifidobacterium, are selectively promoted under fasting conditions, and how the remodeled microbiota are maintained after refeeding and contribute to host physiology. In particular, the rapid enrichment of primary degraders such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Bacteroides may help stabilize and enhance the outcomes of subsequent interventions by amplifying beneficial effects and mitigating undesirable ones. This is because the acquired dietary memory of the gut microbiota improves the metabolism of the entire gut microbiome [54]. Furthermore, despite the presence and abundance of these primary degraders, their effects on the host may vary due to the influence of different substrates on various metabolites, short-chain fatty acid composition and production, and cross-feeding bacteria [42, 50]. Therefore, the combination of fasting + MACs may provide a more flexible intervention that considers the individual baseline or pathology.

Fasting + MACs increased the levels of fecal IgA, which regulate the composition and function of the gut microbiota [28, 39, 40, 87]. IgA binding to bacteria helps protect against infection and inflammation [88–90]. Gut bacteria stimulate IgA production through several mechanisms. For example, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium enhance IgA production through Toll-like receptor 2 signaling via the membrane or membrane vesicles [28, 61, 91]. Additionally, Bacteroides stimulate immune cells and promote IgA production by metabolizing short-chain fatty acids such as acetate and butyrate [36, 69, 92–95]. The type of bacteria and sites recognized and bound by IgA remain unclear. However, the upregulation of IgA using the method described in this study may facilitate the colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by gut bacteria.

To summarize, our results show that fasting induces significant changes in gut microbiota structure, and the administration of MACs during fasting induces selective bacterial growth and host IgA production within a short time frame. For the evaluation of the effects on some diseases and the application of clinical, follow-up studies are required to evaluate the to elucidate how these changes are sustained after refeeding and their influence on the host and the underlying mechanisms. On the other hand, these results indicate that our methods have the potential to be combined with more diverse substrates, such as bacterial membrane vesicles [96, 97] peptides [98]and unsaturated fatty acids [99] as well as to enhance the function of oligosaccharides as gut microbial modulators. These combinations may allow the treatment of various non-communicable diseases without the administration of antibiotics or excessive doses. These findings indicate that fasting and MACs administration can provide an effective approach for modulating the gut microbiota composition.

Methods

Mice

Eight-week-old female C57BL/6JJcl and BALB/cAJcl mice (CLEA Japan Inc.) were housed under standard conditions, under controlled conditions for light (12 h light/dark cycle), temperature (24 ± 0.5 °C), and humidity (40 ± 5%), at the animal facility of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Keio University (Tokyo, Japan). Mice had free access to food, CE-2 (CLEA Japan, Inc.), and tap water. Following a 5–7-day acclimatization period, the mice were randomly assigned to three to five mice per group. The mice in the fasting group were fasted for 12–36 h and given a solution containing 10% (w/v) of various prebiotics (fructo-oligosaccharides; FOS, galacto-oligosaccharide; GOS, or α-cyclodextrin; α-Cyd. All products were manufactured by FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Japan). Human milk oligosaccharides (2’-fucosyllactose; 2FL, 3’-sialyllactose; 3SL and 6’-sialyllactose; 6SL) were obtained from KYOWA HAKKO BIO CO. LTD., Japan. The HMO cocktail was prepared with each HMO included to achieve a final concentration of 10% (w/v). MACs were administered either via drinking water (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) or by oral gavage (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). Oral administration was used in fasting experiments to ensure consistent intake, as voluntary water consumption can decrease under fasting conditions [100]. Euglena and paramylon were obtained from Euglena Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Paramylon was isolated as previously described [101]. Euglena and Paramylon were orally administered [66] at a final concentration of 375 µg in 200 µL PBS after the start of the fasting period. All mice were unconscious under inhalant isoflurane anesthesia and sacrificed by exsanguination with cardiocentesis at the end of the experiment. To avoid coprophagia, the mice were kept in cages without bedding chips on a stainless-steel mesh floor. The animal experiments conducted in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Kitasato University (Approval No. 24 − 10) and Keio University (Approval No. A2022-078).

16S ribosomal RNA sequencing and analysis

Bacterial DNA was extracted from mouse feces using the E.Z.N.A. Stool DNA Kit Pathogen Detection Protocol (OMEGA) and purified using an magLEAD 12 gc Nucleic Acid Extraction Instrument (Precision System Science Co., Ltd.). DNA was amplified by PCR using primers specific to the V3-V4 regions of the 16 S ribosomal RNA gene (Key Resources Table). Sequencing was performed by Cancer Precision Medicine (Japan) using an MiSeq System (Illumina, Inc., USA). Raw FASTQ files were processed using QIIME2 (Version 2022.2.0) [102] with denoising using DADA2 [103]. The taxonomy was assigned with the DADA2 implementation of the Ribosomal Database Project classifier using the SILVA database [104, 105]. Sequences were deposited into the SRA database of NCBI: PRJNA1272289.

Total IgA ELISA

Fecal samples were lyophilized overnight. Freeze-dried feces (10 mg) were disrupted using 3.0 mm Zirconia Beads (Biomedical Science, Japan) and a Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) by vigorous shaking (1,500 rpm for 15 min) using a Shake Master (Biomedical Science, Japan). The lysate was centrifuged at 18,000 ×g at 4 °C for 15 min and the supernatant was collected as a fecal extract. The samples were stored at − 80 °C until use. Total IgA levels were measured using a Mouse IgA ELISA Quantitation Set (Bethyl Laboratories, USA) and the IgA concentration in 1 mg feces was estimated.

Statistical analysis

Dunnett’s test was used for statistical analyses of the two groups. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.0.3, GraphPad Software Inc.). Statistical significance is indicated with * denoting P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, and **** P < 0.0001. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 10 software (Version 10.2.3) and Qiime2 using Pairwise Palmanova, Welch’s t-test, and One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. Data were visualized using Python (version 3.8.3), the matplotlib (version 3.5.0), seaborn (version 0.11.2) packages, and GraphPad Prism 10 software (Version 10.2.3).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kyosuke Yakabe, Tomoka Kawashima, Yu Ishiyama, Minami Wakita, and Mayu Myobudani for providing technical support, and Tomoya Tsukimi and Kazuki Tanaka for valuable discussions.

Abbreviations

- α-Cyd

α-cyclodextrin

- FOS

Fructo-oligosaccharides

- GOS

Galacto-oligosaccharides

- HMOs

Human milk oligosaccharides

- MACs

Microbiota-accessible carbohydrates

- SCFAs

Short-chain fatty acids

- 2FL

2’-fucosyllactose

- 3SL

3’-sialyllactose

- 6SL

6’-sialyllactose

Authors’ contributions

K.S., J.I., and Y.-G.K. conceived the study and designed the experiments; K.S. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; K.S., A.N., J.I., S.F, and Y.-G.K. provided resources; and K.S. and Y.-G.K. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all the authors. Y.-G.K. supervised the study.

Funding

This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (JP23H02718 and JP 23K18223 to Y.-G.K.), KYOWA HAKKO BIO CO. LTD (to Y.-G.K.), Euglena Co., Ltd. (to Y.-G.K.), JST SPRING (JPMJSP2123 to K.S.), the Young Leaders Fellowship Fund (to K. S.), Sylff Research Grant (2346 to K.S.), and research funds from the Yamagata Prefectural Government and the City of Tsuruoka (to K.S.).

Data availability

The sequencing data were deposited to the Sequence Read Archive National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with accession number: PRJNA1272289.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal experiments conducted in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Kitasato University (Approval No. 24 − 10) and Keio University (Approval No. A2022-078).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Ayaka Nakashima is a researcher at Euglena Co., Ltd. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Joe Inoue, Email: inoue@lne.st.

Yun-Gi Kim, Email: kim.yungi@kitasato-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Salvucci E. The human-microbiome superorganism and its modulation to restore health. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2019;70:781–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arifuzzaman M, et al. Inulin fibre promotes microbiota-derived bile acids and type 2 inflammation. Nature. 2022;611:578–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd-Price J, et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature. 2019;569:655–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolte LA, et al. Long-term dietary patterns are associated with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory features of the gut Microbiome. Gut. 2021;70:1287–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fröhlich EE, et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;56:140–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asnicar F, et al. Microbiome connections with host metabolism and habitual diet from 1,098 deeply phenotyped individuals. Nat Med. 2021;27:321–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant ET, De Franco H, Desai MS. Non-SCFA microbial metabolites associated with fiber fermentation and host health. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2025;36:70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gasaly N, de Vos P, Hermoso MA. Impact of bacterial metabolites on gut barrier function and host immunity: A focus on bacterial metabolism and its relevance for intestinal inflammation. Front Immunol. 2021;12:658354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Kaoutari A, Armougom F, Gordon JI, Raoult D, Henrissat B. The abundance and variety of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the human gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomioka S, et al. Cooperative action of gut-microbiota-accessible carbohydrates improves host metabolic function. Cell Rep. 2022;40:111087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayakdaş G, Ağagündüz D. Microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs) as novel gut Microbiome modulators in noncommunicable diseases. Heliyon. 2023;9:e19888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolodziejczyk AA, Zheng D, Elinav E. Diet-microbiota interactions and personalized nutrition. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:742–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma C, et al. The gut Microbiome stability is altered by probiotic ingestion and improved by the continuous supplementation of galactooligosaccharide. Gut Microbes. 2020;12:1785252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pihelgas S, Ehala-Aleksejev K, Adamberg S, Kazantseva J, Adamberg K. The gut microbiota of healthy individuals remains resilient in response to the consumption of various dietary fibers. Sci Rep. 2024;14:22208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan J, et al. Functional profiling of gut microbial and immune responses toward different types of dietary fiber: a step toward personalized dietary interventions. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2274127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliver A, et al. High-fiber, whole-food dietary intervention alters the human gut Microbiome but not fecal short-chain fatty acids. mSystems. 2021;6:e00115–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cignarella F, et al. Intermittent fasting confers protection in CNS autoimmunity by altering the gut microbiota. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1222–e12356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, et al. Gut microbiota mediates intermittent-fasting alleviation of diabetes-induced cognitive impairment. Nat Commun. 2020;11:855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angoorani P, et al. Gut microbiota modulation as a possible mediating mechanism for fasting-induced alleviation of metabolic complications: a systematic review. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2021;18:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma R-X, et al. Intermittent fasting protects against food allergy in a murine model via regulating gut microbiota. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1167562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu X, et al. Intermittent fasting modulates the intestinal microbiota and improves obesity and host energy metabolism. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2023;9:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducarmon QR, et al. Remodelling of the intestinal ecosystem during caloric restriction and fasting. Trends Microbiol. 2023;31:832–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He Y, et al. Fasting challenges human gut Microbiome resilience and reduces Fusobacterium. Med Microecol. 2019;1–2:100003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ducarmon QR, et al. Long-term fasting remodels gut microbial metabolism and host metabolism. BioRxiv. 2024;20240419590209. 10.1101/2024.04.19.590209.

- 26.Imada S, et al. Short-term post-fast refeeding enhances intestinal stemness via polyamines. Nature. 2024;633:895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okada T, et al. Microbiota-derived lactate accelerates colon epithelial cell turnover in starvation-refed mice. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huus KE, et al. Commensal bacteria modulate Immunoglobulin A binding in response to host nutrition. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:909–e9215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohl KD, Amaya J, Passement CA, Dearing MD, McCue MD. Unique and shared responses of the gut microbiota to prolonged fasting: a comparative study across five classes of vertebrate hosts. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2014;90:883–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan H, Hutkins RW. Fermentation of fructooligosaccharides by lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2682–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li W, et al. Influences of structures of galactooligosaccharides and fructooligosaccharides on the fermentation in vitro by human intestinal microbiota. J Funct Foods. 2015;13:158–68. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan X, et al. Fructooligosaccharides protect against OVA-induced food allergy in mice by regulating the Th17/Treg cell balance using Tryptophan metabolites. Food Funct. 2021;12:3191–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hidaka H, Eida T, Takizawa T, Tokunaga T, Tashiro Y. Effects of fructooligosaccharides on intestinal flora and human health. Bifidobact Microflora. 1986;5:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosono A, et al. Dietary fructooligosaccharides induce immunoregulation of intestinal IgA secretion by murine peyer’s patch cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:758–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura Y, et al. Dietary fructooligosaccharides up-regulate Immunoglobulin A response and polymeric Immunoglobulin receptor expression in intestines of infant mice: fructooligosaccharides and mucosal IgA response. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;137:52–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jangid A, et al. Impact of dietary fructooligosaccharides (FOS) on murine gut microbiota and intestinal IgA secretion. 3 Biotech. 2022;12:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki K, et al. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1981–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hapfelmeier S, et al. Reversible microbial colonization of germ-free mice reveals the dynamics of IgA immune responses. Science. 2010;328:1705–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donaldson GP, et al. Gut microbiota utilize Immunoglobulin A for mucosal colonization. Science. 2018;360:795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakajima A, et al. IgA regulates the composition and metabolic function of gut microbiota by promoting symbiosis between bacteria. J Exp Med. 2018;215:2019–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu F, et al. Fructooligosaccharide (FOS) and galactooligosaccharide (GOS) increase Bifidobacterium but reduce butyrate producing Bacteria with adverse glycemic metabolism in healthy young population. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmes ZC, et al. Microbiota responses to different prebiotics are conserved within individuals and associated with habitual fiber intake. Microbiome. 2022;10:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nihei N, et al. Dietary α-cyclodextrin modifies gut microbiota and reduces fat accumulation in high-fat-diet-fed obese mice: antiobesity effect of α-cyclodextrin. BioFactors. 2018;44:336–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morita H, et al. Bacteroides uniformis and its preferred substrate, α-cyclodextrin, enhance endurance exercise performance in mice and human males. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eadd2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walsh C, Lane JA, van Sinderen D, Hickey RM. Human milk oligosaccharides: shaping the infant gut microbiota and supporting health. J Funct Foods. 2020;72:104074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jost T, Lacroix C, Braegger C, Chassard C. Impact of human milk bacteria and oligosaccharides on neonatal gut microbiota establishment and gut health. Nutr Rev. 2015;73:426–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paone P, et al. Human milk oligosaccharide 2’-fucosyllactose protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity by changing intestinal mucus production, composition and degradation linked to changes in gut microbiota and faecal proteome profiles in mice. Gut. 2024;73:1632–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Versluis DM, Schoemaker R, Looijesteijn E, Geurts JMW, Merks RM. H. 2’-Fucosyllactose helps butyrate producers outgrow competitors in infant gut microbiota simulations. iScience. 2024;27:109085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sato Y, Kanayama M, Nakajima S, Hishida Y, Watanabe Y. Sialyllactose enhances the short-chain fatty acid production and barrier function of gut epithelial cells via nonbifidogenic modification of the fecal Microbiome in human adults. Microorganisms. 2024;12:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, et al. In vitro fermentation of human milk oligosaccharides by individual Bifidobacterium longum-dominant infant fecal inocula. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;287:119322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu Z-T, Chen C, Newburg DS. Utilization of major fucosylated and sialylated human milk oligosaccharides by isolated human gut microbes. Glycobiology. 2013;23:1281–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberfroid M, et al. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(2):S1–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scott KP, et al. Developments in Understanding and applying prebiotics in research and practice-an ISAPP conference paper. J Appl Microbiol. 2020;128:934–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Letourneau J, et al. Ecological memory of prior nutrient exposure in the human gut Microbiome. ISME J. 2022;16:2479–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parhi P, Song KP, Choo WS. Growth and survival of Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium longum in various sugar systems with fructooligosaccharide supplementation. J Food Sci Technol. 2022;59:3775–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shuhaimi M, Kabeir BM, Yazid AM. Nazrul somchit, M. Synbiotics growth optimization of Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum G4 with prebiotics using a statistical methodology. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;106:191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mao B, et al. Effects of different doses of fructooligosaccharides (FOS) on the composition of mice fecal microbiota, especially the Bifidobacterium composition. Nutrients. 2018;10:1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L, et al. Effects of different oligosaccharides at various dosages on the composition of gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in mice with constipation. Food Funct. 2017;8:1966–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi T, Nakagawa E, Nara T, Yajima T, Kuwata T. Effects of orally ingested Bifidobacterium longum on the mucosal IgA response of mice to dietary antigens. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kato T, et al. Integrated multi-omics analysis reveals differential effects of fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) supplementation on the human gut ecosystem. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:11728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kurata A, et al. Enhancement of IgA production by membrane vesicles derived from Bifidobacterium longum subsp. Infantis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2022;87:119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borbet TC, et al. Disruption of the early-life microbiota alters peyer’s patch development and germinal center formation in gastrointestinal-associated lymphoid tissue. iScience. 2023;26:106810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang X, et al. Dietary oat β-glucan alleviates high-fat induced insulin resistance through regulating circadian clock and gut Microbiome. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2024;68:e2300917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakashima A, et al. Β-glucan in foods and its physiological functions. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2018;64:8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mio K, Otake N, Nakashima S, Matsuoka T, Aoe S. Ingestion of high β-glucan barley flour enhances the intestinal immune system of diet-induced obese mice by prebiotic effects. Nutrients. 2021;13:907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor HB, Gudi R, Brown R, Vasu C. Dynamics of structural and functional changes in gut microbiota during treatment with a microalgal β-glucan, paramylon and the impact on gut inflammation. Nutrients. 2020;12:2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ryan C, et al. Euglena gracilis-derived β-glucan paramylon entrains the peripheral circadian clocks in mice. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1113118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yanagibashi T, et al. Bacteroides induce higher IgA production than Lactobacillus by increasing activation-induced cytidine deaminase expression in B cells in murine peyer’s patches. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:372–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang C, et al. Fecal IgA levels are determined by strain-level differences in Bacteroides ovatus and are modifiable by gut microbiota manipulation. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:467–e4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Long W, et al. Differential responses of gut microbiota to the same prebiotic formula in oligotrophic and eutrophic batch fermentation systems. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saglam D, et al. Effects of ramadan intermittent fasting on gut microbiome: is the diet key? Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1203205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ali I, et al. Ramadan fasting leads to shifts in human gut microbiota structured by dietary composition. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sun J, et al. Fructooligosaccharides ameliorating cognitive deficits and neurodegeneration in APP/PS1 Transgenic mice through modulating gut microbiota. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67:3006–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mao B, et al. Metagenomic insights into the effects of fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) on the composition of fecal microbiota in mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:856–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li C, et al. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics regulate the intestinal microbiota differentially and restore the relative abundance of specific gut microorganisms. J Dairy Sci. 2020;103:5816–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tandon D, et al. A prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response relationship study to investigate efficacy of fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) on human gut microflora. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sela D. A., et al. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. Infantis reveals adaptations for milk utilization within the infant Microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18964–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Laursen MF, et al. Bifidobacterium species associated with breastfeeding produce aromatic lactic acids in the infant gut. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6:1367–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kijner S, Ennis D, Shmorak S, Florentin A, Yassour M. CRISPR-Cas-based identification of a sialylated human milk oligosaccharides utilization cluster in the infant gut commensal Bacteroides dorei. Nat Commun. 2024;15:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buzun E, et al. A bacterial Sialidase mediates early-life colonization by a pioneering gut commensal. Cell Host Microbe. 2024;32:181–e1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bäckhed F, et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut Microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:690–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thongaram T, Hoeflinger JL, Chow J, Miller MJ. Human milk oligosaccharide consumption by probiotic and human-associated bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:7825–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garrido D, et al. Comparative transcriptomics reveals key differences in the response to milk oligosaccharides of infant gut-associated bifidobacteria. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xiao M, et al. Cross-feeding of bifidobacteria promotes intestinal homeostasis: a lifelong perspective on the host health. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2024;10:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nishiyama K, et al. Two extracellular Sialidases from Bifidobacterium bifidum promote the degradation of sialyl-oligosaccharides and support the growth of Bifidobacterium breve. Anaerobe. 2018;52:22–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kavanaugh DW, et al. Exposure of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. Infantis to milk oligosaccharides increases adhesion to epithelial cells and induces a substantial transcriptional response. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Planer JD, et al. Development of the gut microbiota and mucosal IgA responses in twins and gnotobiotic mice. Nature. 2016;534:263–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fransen F, et al. BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice differ in polyreactive IgA abundance, which impacts the generation of antigen-specific IgA and microbiota diversity. Immunity. 2015;43:527–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gupta S, et al. IgA determines bacterial composition in the gut. Crohns Colitis. 2023;360(5):otad030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Okai S, et al. High-affinity monoclonal IgA regulates gut microbiota and prevents colitis in mice. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yamasaki-Yashiki S, Miyoshi Y, Nakayama T, Kunisawa J, Katakura Y. IgA-enhancing effects of membrane vesicles derived from Lactobacillus sakei subsp. sakei NBRC15893. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 2019;38:23–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim M, Qie Y, Park J, Kim CH. Gut microbial metabolites fuel host antibody responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:202–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu W, et al. Microbiota metabolite short-chain fatty acid acetate promotes intestinal IgA response to microbiota which is mediated by GPR43. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:946–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Takeuchi T, et al. Acetate differentially regulates IgA reactivity to commensal bacteria. Nature. 2021;595:560–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Isobe J, et al. Commensal-bacteria-derived butyrate promotes the T-cell-independent IgA response in the colon. Int Immunol. 2020;32:243–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Toyofuku M, Schild S, Kaparakis-Liaskos M, Eberl L. Composition and functions of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:415–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang X, et al. Versatility of bacterial outer membrane vesicles in regulating intestinal homeostasis. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eade5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen PB, et al. Directed remodeling of the mouse gut Microbiome inhibits the development of atherosclerosis. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:1288–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Song X, et al. Gut microbial fatty acid isomerization modulates intraepithelial T cells. Nature. 2023;619:837–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pedroso JAB, Wasinski F, Donato J. Jr. Prolonged fasting induces long-lasting metabolic consequences in mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2020;84:108457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Inui H, Miyatake K, Nakano Y, Kitaoka S. Wax ester fermentation inEuglena gracilis. FEBS Lett. 1982;150:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bolyen E, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible Microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:852–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Callahan BJ, et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Quast C, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA and ‘All-species living tree project (LTP)’ taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D643–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data were deposited to the Sequence Read Archive National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with accession number: PRJNA1272289.