Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) has become increasingly prevalent among the older Chinese population. Radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) represents an efficient procedure to reduce and minimize deleterious consequences in older patients with AF. However, self-control is often impaired in older patients, potentially affecting their recovery following surgical treatments—which can result in repeated episodes of both AF and hospital readmission. This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate self-control among older patients with AF following RFCA procedures and identify the factors that influence it, with the goal of gaining insights to inform the development of relevant clinical metrics for healthcare practitioners.

Methods

Between May and November 2024, we conducted an investigation among older patients aged ≥ 60 years with AF who were follow-up with in hospital over the first month after having received RFCA treatment. A variety of questionnaires were used, including the General Information Questionnaire; as well as Chinese version of the Brief Self-Control Scale, Perceived Social Support Scale, Family APGAR Index, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Univariate, correlation, and multiple linear regression analyses were used to investigate the factors influencing self-control in older patients with AF.

Results

A total of 230 questionnaires were distributed and 217 valid ones were returned, yielding a valid return rate of 94.35%. The total score for self-control was 22.48 ± 6.28, representing a moderate level. The multiple linear regression analyses revealed that the most important factors that negatively influenced self-control among our cohort of older patients were EHRA symptom classification and anxiety and depression, while family care and social support positively promoted better self-control.

Conclusion

Self-control among older Chinese patients with AF after RFCA is currently insufficient and should be improved. Healthcare practitioners should consider intervening to reduce anxiety and depression, as well as promote social support and family care among their patients to improve self-control, prognosis, and quality of life from both individual and environmental perspectives.

Trial registration

Not available.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-025-06141-y.

Keywords: Older patients, Atrial fibrillation, Radiofrequency catheter ablation, Self-control, Triadic reciprocal determinism, Influencing factors

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common tachyarrhythmia observed in clinical practice, has high global rates of prevalence, morbidity, mortality, disability, and readmission. This significantly endangers the lives and health of affected patients, while concurrently placing a major cost burden on the global healthcare system [1–4]. There are currently about 33 million people living with AF worldwide, of which around 12 million are in China. The prevalence of AF increases with age [5, 6]. With a rapidly aging population, there is widespread concern regarding the health of older patients with AF in China [7]. Radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) represents the preferred for AF, and is generally effective in terms of alleviating and controlling its symptoms [8, 9]. Nevertheless, there remains a significant incidence of AF recurrence after RFCA, particularly in older patients [10–14]. AF recurrence not only worsens overall health and psychological burdens among patients, but also increases the risk of heart failure and stroke—both of which can be exceedingly damaging to postoperative rehabilitation [15, 16]. Studies have shown that efficient postoperative self-management can help to preserve the efficacy of surgical treatments for AF, and lower the risk of its recurrence [17, 18].

Self-control is broadly characterized as an individual’s ability to control their behavior and emotions in the face of temptations, impulses, or distractions [19]. Self-control is vital for efficient self-management because it empowers people to persevere when pursuing goals, overcome obstacles, and retain focus and self-discipline [20, 21]. Older patients with AF require more self-control than younger patients [22, 23]. Specifically, the self-control behaviors needed for older patients with AF to avoid its recurrence after undergoing RFCA and promote recovery include various patient-led behaviors such as strict adherence to anticoagulation therapy, regular pulse rate monitoring, blood pressure control, avoidance of alcohol and tobacco use, regular physical activity, timely reporting of any cardiac symptoms, and regular check-ups involving electrocardiograms [24–27]. However, studies have shown that such patients often fail to maintain the necessary degree of self-control [28–30]. A study conducted in the Netherlands found that older patients with AF had limited control over their heart rates and rhythms [31]. To our knowledge, no such studies have yet been conducted in China. To improve postoperative self-control in older patients with AF and thus reduce its recurrence, healthcare providers must understand postoperative self-control levels in this demographic and analyze factors that might influence them, as a foundation for the development of appropriate interventions.

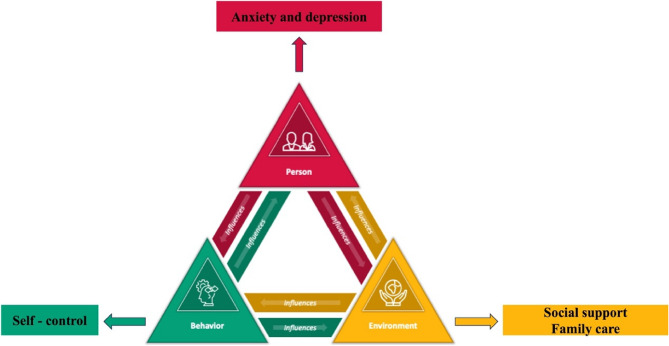

Traditional approaches such as the health belief model concentrate primarily on the impact of patient cognition on behavior [32], thus ignoring the relationship between environmental support (e.g., family care) and psychological states (e.g., anxiety and depression). Albert Bandura advocated that triadic reciprocal determinism, a major concept in social cognitive theory [33], is more appropriate when addressing the complexities of postoperative rehabilitation in older patients with AF. This method focuses on the interaction of individual behaviors with both individual and environmental influencing factors. Individual variables comprise the psychological and physiological characteristics that shape an individual’s behavior and perception of their surroundings [34], while environmental factors include social support, cultural background, economic situation, and social standing. Behavioral aspects include an individual’s external behaviors and actions, such as daily habits and patterns, self-regulation, and adaptive behaviors [34]. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze self-control status in older patients with AF following RFCA, as well as the potential factors that impacted them, using triadic reciprocal determinism as a guiding paradigm. Figure 1 shows the principles of triadic reciprocal determinism, as well as the hypothetical framework used in this study. Our hypotheses were as follows:

Fig. 1.

The Triadic Reciprocal Determinism Model and the hypothetical framework in this study

-

a

According to triadic reciprocal determinism, the behavioral element is post-RFCA self-control, the individual factors comprise anxiety and depression, and the environmental factors include family care and social support.

-

b

Social support and family care (i.e., the environmental factors), as well as anxiety and depression (i.e., the individual factors), may influence levels of self-control (i.e., the behavioral element) among older patients with AF who have undergone RFCA treatment.

Methods

Design

This was a cross-sectional study.

Study setting and sampling

We used a consecutive sample approach to recruit older patients with AF who had returned to the hospital for a follow-up check-up between May and November 2024 during the first month following the surgical RFCA treatment. The sample size was about 5–10× the number of variables [35], and assessed 22 factors. Accounting for an estimated 20% invalid questionnaires, the necessary sample size was estimated to be between 132 and 264. Therefore, a target sample size of 230 participants was elected for this investigation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were patients who: (1) were aged ≥ 60 years; (2) met the diagnostic criteria for AF [26], for which they had undergone successful RFCA treatment with no major complications within the preceding month; (3) were conscious and competent to read or communicate without difficulty; and (4) gave their written informed consent to willingly participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were those who: (1) suffered from serious brain, liver, kidney, or other organ illnesses; (2) had severe cognitive, consciousness-related, or psychiatric disorders; and (3) voluntarily withdrew from the study, for reasons such as significant physical fatigue.

Instruments

General information questionnaire

The general questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first concerned demographic information such as gender, age, body mass index, education level, marital status, and employment status; while the second addressed disease-related information including AF duration, EHRA symptom classification, and comorbidities.

Chinese version of the brief Self-Control scale

The Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS) was used to measure self-control. It comprises a simplified version of Morean’s Self-Control Scale [36] that eliminates weariness and response bias, yielding a seven-item scale with two dimensions (self-discipline and impulse control) [37]. The three items (1, 3, and 5) from the self-discipline dimension are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Conversely, the four items that form the impulse control dimension (2, 4, 6, and 7) are graded in reverse. In 2021, Luo et al. [38] translated and assessed the scale’s dependability among Chinese citizens. Its overall Cronbach’s alpha value is determined to be 0.83, while those for the self-discipline and impulse control dimensions are 0.85 and 0.86, respectively—indicating that the scale is appropriate for use in China.

Chinese version of the perceived social support scale

The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), first created by Zimet et al. [39] and later translated into Chinese by Jiang et al. [40], measures perceptions of social support. It comprises three dimensions: family support (items 3, 4, 8, and 11); support from friends (items 6, 7, 9, and 12); and other forms of support (items 1, 2, 5, and 10). It includes 12 total items, each rated on a seven-point Likert scale. The total score, which ranges between 12 and 84 points, indicates the respondents’ perceived level of social support, with higher scores indicating more social support. Scores of 12–36, 37–60, and 61–84 are classified as low, moderate, and high levels of social support, respectively.

Chinese version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is commonly used to diagnose anxiety and depression. Zigmond and Snaith [41] developed the scale, which consists of 14 items: seven concerning anxiety and seven concerning depression. It uses a four-point Likert scale, with each item ranging between 0 and 3 points based on the severity of the respondent’s symptoms. Total scores on both subscales range between 0 and 21, with subscale scores of ≥ 8 typically suggesting significant anxiety or depression symptoms. The Chinese version of the scale was translated by Ye et al. [42]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the overall, anxiety subscale, and depression subscale of the Chinese HADS have been reported to be 0.879, 0.806, and 0.806, respectively; while its retest reliability values are 0.945, 0.921, and 0.932, respectively.

Chinese version of the family APGAR index

This study used the APGAR, first established by Smilkstein et al. [43] and later translated into Chinese by Lv et al. [44], to assess the degree of family care received by our respondents. It comprises five dimensions: adaptation, partnership, growth, affection, and resolution. Five items are graded on a three-point scale ranging from “almost rarely” to “often”. The total score range from 0 to 10 points and correlate positively with the quality of family care. A score of 7–10 points suggests positive family functioning, 4–6 points indicates moderate family functioning, and 0–3 points indicates severe family dysfunction.

Data collection

The data were obtained from the patients when they visited the hospital for follow-up appointments during the first month of stable condition following their RFCA procedures. Data were collected on site by uniformly trained researchers who followed standardized processes. Before each questionnaire was administered, the patient was informed of the study’s purpose, content, and anonymity. Each then signed an informed consent form. All of the patients were questioned individually and face to face. The researchers used consistent language to clarify any aspects that the patients did not immediately understand. The questionnaires were collected onsite and verified for completeness. The researchers completed the second section of the questionnaire on behalf of each patient after reviewing their medical records and obtaining consent from their attending physician. We distributed 230 total questionnaires and received 217 genuine responses, yielding a valid response rate of 94.35%.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed statistically using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical data are presented as frequencies (associated percentages). Normally-distributed data were compared across groups using the independent-samples Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance. Multiple linear regression was used to investigate the factors that influenced self-control among the patients, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing and Rehabilitation, Shandong University, with ethics approval number 2023-R-101. This study followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All of the included participants signed an informed consent form before providing their data.

Results

Demographic patient characteristics

We included a total of 217 older patients with AF, with a mean age of 68.40 ± 6.47 years (i.e., following a normal distribution). Among them, 127 (58.5%) were male and 90 (41.5%) were female. Additional information regarding the participants’ characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics of the patients (n = 217)

| Characteristics | Number (%)/Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| male | 127(58.53%) |

| female | 90(41.47%) |

| Age | 68.40 ± 6.47 |

| BMI | |

| ~ 18.5 | 2 (0.92%) |

| 18.5~ | 61(28.11%) |

| 24~ | 97(44.70%) |

| 28~ | 53(24.42%) |

| 34~ | 4 (1.84%) |

| Marital status | |

| unmarried/widowed/divorced | 13(5.99%) |

| married | 204(94.01%) |

| Education | |

| elementary school or below | 46(21.20%) |

| junior high school | 47(21.66%) |

| high school | 50(23.04%) |

| college or bachelor’s school | 74(34.10%) |

| Employment status | |

| unemployed | 4(1.84%) |

| employed | 121(55.76%) |

| retired | 92(42.40%) |

| Household income (yuan) | |

| ~ 3000 | 74(34.10%) |

| 3000 ~ 6000 | 105(48.39%) |

| 6000~ | 38(17.51%) |

| AF Duration | |

| ~ 6months | 56(25.81%) |

| 6months ~ 1 year | 17(7.83%) |

| 1 ~ 3years | 45(20.74%) |

| 3 years~ | 99(45.62%) |

| EHRA | |

| I | 3(1.38%) |

| IIa | 37(17.05%) |

| IIb | 51(23.50%) |

| III | 126(58.06%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| none | 41(18.89%) |

| combined stroke | 7(3.23%) |

| combined heart failure | 6(2.76%) |

| combined diabetes | 5(2.30%) |

| combined heart infarction | 7(3.23%) |

| combined hypertension | 50(23.04%) |

| combined coronary vascular disease | 9(4.15%) |

| combined 2 or more of the above | 92(42.40%) |

BMI, body mass index, AF, atrial fibrillation, EHRA European Heart Rhythm Association’s Atrial Fibrillation-Related Symptom Classification

Self-control status and univariate analysis

The overall BSCS scores varied between 7 and 35 points. The older patients had a mean BSCS score of 22.48 ± 6.28, which was lower than 66% of the maximum score of 35, thus indicating an intermediate level of self-control. Comparisons of the patients’ total and sub-dimension BSCS scores vs. the scores ranges are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The scores on the brief Self-Control Scale(n = 217)

| Totals/Sub-Dimensions/Items | Scores, mean ± SD | Scores ranges |

|---|---|---|

| Self -control | 22.48 ± 6.28 | 7 ~ 35 |

| Self-discipline | 10.13 ± 3.10 | 3 ~ 15 |

| Item 1 | 3.35 ± 1.37 | 1 ~ 5 |

| Item 3 | 3.27 ± 1.02 | 1 ~ 5 |

| Item 5 | 3.51 ± 1.23 | 1 ~ 5 |

| Impulse control | 12.35 ± 3.60 | 4 ~ 20 |

| Item 2 | 2.93 ± 1.18 | 1 ~ 5 |

| Item 4 | 2.98 ± 1.25 | 1 ~ 5 |

| Item 6 | 3.25 ± 1.18 | 1 ~ 5 |

| Item 7 | 3.19 ± 1.00 | 1 ~ 5 |

Univariate analysis revealed that marital status, household income, EHRA symptom classification, and comorbidities significantly influenced self-control among the participants (P < 0.05). The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The results of a univariate analysis of the factors influencing self-control (n = 217)

| Characteristics | t/F | P |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.8061) | 0.404 |

| male | ||

| female | ||

| BMI | 0.9902) | 0.414 |

| ~ 18.5 | ||

| 18.5~ | ||

| 24~ | ||

| 28~ | ||

| 34~ | ||

| Marital status | 0.4581) | 0.044 |

| unmarried/widowed/divorced | ||

| married | ||

| Education | 0.9622) | 0.412 |

| elementary school or below | ||

| junior high school | ||

| high school | ||

| college or bachelor’s school | ||

| Employment status | 0.0162) | 0.984 |

| unemployed | ||

| employed | ||

| retired | ||

| Household income (yuan) | 3.4302) | 0.036 |

| ~ 3000 | ||

| 3000 ~ 6000 | ||

| 6000~ | ||

| AF Duration | 1.2452) | 0.294 |

| ~ 6months | ||

| 6months ~ 1 year | ||

| 1 ~ 3years | ||

| 3 years~ | ||

| EHRA | 34.0742) | < 0.001 |

| I | ||

| IIa | ||

| IIb | ||

| III | ||

| Comorbidities | 4.1712) | 0.004 |

| none | ||

| combined stroke | ||

| combined heart failure | ||

| combined diabetes | ||

| combined heart infarction | ||

| combined hypertension | ||

| combined coronary vascular disease | ||

| combined 2 or more of the above | ||

(1) t-test; (2) one-way ANOVA analysis; BMI, body mass index; AF, atrial fibrillation EHRA, European Heart Rhythm Association’s Atrial Fibrillation-Related Symptom Classification.

Correlation analysis of Self-control with social support, anxiety and depression, and family care

The overall social support score was 66.45 ± 8.70, which correlated positively with self-control (r = 0.542, P < 0.01). The lowest score 21.77 ± 3.32 was regarding support from social relationships with people such as leaders and co-workers. The patients’ mean anxiety and depression score was 26.59 ± 8.99, which correlated negatively with self-control (r = − 0.378, P < 0.01). More specifically, the mean score for the anxiety dimension was 13.03 ± 8.98, while that of the depression dimension was 13.56 ± 4.51—both > 8 points. The mean family care score was 7.18 ± 2.78, which correlated positively with self-control (r = 0.640, P < 0.01). Finally, age was negatively correlated with self-control (r = 0.228, P < 0.01). Table 4 presents the full details regarding our correlation analysis results.

Table 4.

The results of the correlation study(n = 217)

| Variables | Self-control | Social support | Anxiety and depression | Family Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-control | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Social support | 0.542** | —— | —— | —— |

| Anxiety and depression | −0.378** | −0.289** | —— | —— |

| Family Care | 0.640** | 0.529** | −0.261** | —— |

| Age | −0.228** | −0.199** | 0.342** | 0.050 |

**, P< 0.01

Multiple linear regression analyses of the factors influencing self-control

Self-control was chosen as the dependent variable for our multiple linear regression analyses. Any variables that showed statistically significant differences in our univariate analysis, as well as the variables identified through our correlation analysis, were used as independent variables in the regression equations. Table 5 shows the variable assignments, while Table 6 presents our multiple linear regression analyses results.

Table 5.

Assignment table of argument variables(n = 217)

| Variables | Assignment |

|---|---|

| Marital status | “unmarried/widowed/divorced” =1, “married” =2 |

| Household income | “~3000” =1, “3000 ~ 6000” =2, “6000~” =3 |

| EHRA | “I”=1,“IIa”=2,“IIb”=3,“III”=4 |

| Comorbidities | “none”=(0,0,0,0,0,0,0),“combined stroke”=(1,0,0,0,0,0,0),“combined heart failure”=(0,1,0,0,0,0,0),“combined diabetes”=(0,0,1,0,0,0,0),“combined heart infarction”=(0,0,0,1,0,0,0),“combined hypertension”=(0,0,0,0,1,0,0),“combined coronary vascular disease”=(0,0,0,0,0,1,0),“combined 2 or more of the above”=(0,0,0,0,0,0,1) |

| Age | Original value entry |

| Social Support | Original value entry |

| Anxiety and depression | Original value entry |

| Family Care | Original value entry |

EHRA European Heart Rhythm Association’s Atrial Fibrillation-Related Symptom Classification

Table 6.

The results of multiple linear regression analyses of influencing factors on self-control (n = 217)

| Variables | β | SE | β’ | t | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 14.858 | 5.457 | —— | 2.723 | 0.007 | —— |

| Marital status | 1.551 | 1.275 | 0.059 | 1.217 | 0.225 | 1.062 |

| Household income | 0.770 | 0.430 | 0.086 | 1.789 | 0.075 | 1.049 |

| EHRA | −1.172 | 0.377 | −0.152 | −3.107 | 0.002 | 1.090 |

| Comorbidities | −0.046 | 0.114 | −0.020 | −0.408 | 0.684 | 1.088 |

| Age | −0.081 | 0.050 | −0.083 | −1.609 | 0.109 | 1.222 |

| Social Support | 0.129 | 0.043 | 0.178 | 3.021 | 0.003 | 1.585 |

| Anxiety and depression | −0.123 | 0.037 | −0.177 | −3.305 | 0.001 | 1.301 |

| Family Care | 1.072 | 0.128 | 0.474 | 8.392 | < 0.001 | 1.451 |

The dependent variable is self-control; R2 = 0.544; adjusted R2 = 0.526; F = 30.968; P < 0.001; VIF is variance inflation factor, EHRA European Heart Rhythm Association’s Atrial Fibrillation-Related Symptom Classification

Discussion

Self-Control status in older patients with atrial fibrillation

In this study, we found that the self-control scores of older patients with AF were moderately lower than 66% of their total scale score, meaning there is significant space for improvement. Among the various survey items assessed, item 2—“I’ll do things that bring me pleasure but are harmful to me”— received the lowest score, indicating that the patients sometimes prioritized immediate emotional needs (e.g., pleasure or relaxation) over long-term consequences (e.g., the recurrence of AF or other health problems). The second-lowest score was for item 4—“I’ll be too distracted by having fun to finish my tasks on time”—which revealed that the patients were easily distracted by external distractions, thus resulting in poor self-control.

This suggests that healthcare providers should assess self-control among their patients in a timely manner and promptly initiate targeted health counseling to address any incorrect perceptions and thoughts among them. This result also reflects the influence of the external environment on self-control among patients, and suggests that society should provide better and more convenient conditions for them, so that they can improve their levels of self-control.

Factors that influence Self-control among older patients with atrial fibrillation

Disease-related information

An EHRA symptom classification of severe was found to negatively predict self-control in our patients, which is consistent with the findings of Dong et al. [45]. This is most likely because the EHRA symptom classification represents the current standard for assessing AF severity, developed by the EHRA [46]. Severe symptoms in the patients in this study may have depleted their energy and concentration, which may have directly affected their self-control or indirectly caused negative emotions.

As a result, healthcare providers should pay more attention to older patients with AF, assess the symptoms of AF in a timely manner, and provide targeted guidance and treatment to patients according to the severity of AF, to improve their self-control ability through medical care.

Analyzing the factors that influence postoperative Self-Control based on the triadic reciprocal determinism theory

We explored the impacts of individual (anxiety and depression), as well as environmental (social support and family care) factors on the postoperative self-control behaviors of our patients using triadic reciprocal determinism theory.

Individual factors: anxiety and depression

Our findings indicated that anxiety and depression can negatively predict self-control among patients with AF following RFCA, which is consistent with the findings of Geoffrion et al. [47]. One probable explanation for this is that mood disorders can significantly impede postoperative recovery [48]. Patients may require additional psychological and emotional support to cope with the challenges faced during rehabilitation. Depression and anxiety can impair patients’ capacity to adhere to medical advice and treatment programs, thus potentially compromising both their postoperative recovery and level of self-control.

Therefore, healthcare practitioners should pay attention not only to pre- and intra-operative conditions in their patients, but also to their postoperative recoveries and psychological statuses. Once psychological problems are identified, nursing interventions and psychological counseling treatments based on humanistic care should be administered in a timely manner to alleviate anxiety and improve postoperative self-control practices among patients.

Environmental factors: social support and family care

Better social support was positively associated with postoperative self-control in this study, which is consistent with Sun et al.‘s findings [29]. According to the Conservation of Resources Theory [49], social support can be viewed as a resource that assists individuals in terms of better managing and replenishing the resources needed for self-control. In this study, the older patients with AF often experienced emotions and tension after RFCA. Social support can offer emotional consolation and encouragement during such times, as well as help with and share the burden in order to minimize the patient’s overall stress levels and assist them with regulating negative emotions. This can help lessen the detrimental impact of stress on self-control while also maintaining or even improving it. However, patients with AF who reported receiving less support from “leaders, colleagues, etc.” as their sources of social support showed lower levels of self-control.

Family care was found to positively predict self-control among our patients, which is consistent with the findings of Chen et al. [50]. Family care encourages communication and information-sharing among family members, allowing patients to learn about various self-control skills and procedures. Following RFCA, older patients with AF likely benefit significantly from family care, as it provides a stable environment. This setting enables patients to obtain practical assistance from their family members—such as aiding them with regard to following their treatment plans, reminding them to take their medications, or correcting harmful habits—all of which can contribute to improved self-control.

Therefore, the positive role of both social support and family care suggests that healthcare professionals should involve the families or wider social networks of their patients when developing their postoperative intervention plans. The original units of their patients could also potentially be contacted in order to promote support and care among leaders and colleagues, through gatherings and fellowships. Enhanced levels of supervision and support may be provided to patients through the implementation of collaborative interventions between themselves and their healthcare providers. Ultimately, the enhancement of certain relevant environmental factors may improve self-control among patients with AF during the postoperative period following RFCA, thus facilitating full recovery from the disease.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the relationship between individual, environmental, and behavioral factors among older patients with AF during the early postoperative period following RFCA according to triadic reciprocal determinism theory. It is our sincere hope that our results provide theoretical references for the development of concrete clinical interventions in this field.

Nevertheless, this study has certain limitations worth noting. The samples we used were all obtained from a single hospital, for example. Additionally, RFCA is strongly influenced by the skill level of the physician, which may have led to some degree of selection bias. Finally, this was a cross-sectional study—meaning that the levels of strength associated with the various causal inferences are limited. Thus, this study’s findings may not fully represent all older patients with AF who undergo RFCA treatment in China. Therefore, future studies should consider expanding the sample size and conducting longitudinal multi-center studies in order to gain a better understanding of these relationships.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that older patients with AF showed inadequate levels of self-control after receiving surgical RFCA treatment. According to triadic reciprocal determinism, postoperative self-control is influenced by psychological anxiety and depression in this demographic, as well as external social support and family care. Clinicians should collaborate with the families of their patients in order to improve the social support and family care they receive, as well as assist their patients with resolving psychological issues such as anxiety and depression. This can improve postoperative self-control in such patients, thus reducing the occurrence of postoperative adverse events and promoting earlier postoperative recovery.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the School of Nursing and Rehabilitation, Shandong University and Qilu Hospital of Shandong University. We would like to thank all the patients and health care workers and administrators who participated in this study.

Abbreviations

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- RFCA

Radiofrequency catheter ablation

Authors’ contributions

Author contributionsConcept and design: Ding Yunmei. Data collection and analysis: Ding Yunmei, Zhang Yuan, Zhao Xiaojing, Liu Jialin. Drafting of the article: Ding Yunmei, Zhao Xiaojing, Liu Jialin, Zhang Yanyan. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: Yue Shouwei. Study supervision: Yue Shouwei.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.82372564) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82172535).

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported by the School of Nursing and Rehabilitation, Shandong University and Qilu Hospital of Shandong University. We would like to thank all the patients and health care workers and administrators who participated in this study.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed in this study are not available to the public due to our confidentiality agreements with patients but are available from the corresponding authors on request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing and Rehabilitation, Shandong University, with ethics approval number 2023-R-101.

Consent for publication

Participants all signed informed consent forms. All authors approved the final article and agreed to its publication in this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Andrade JG, Wazni OM, Kuniss M, Hawkins NM, Deyell MW, Chierchia GB, et al. Cryoballoon ablation as initial treatment for atrial fibrillation: JACC State-of-the-Art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(9):914–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, et al. 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: A report of US and global data from the American heart association. Circulation. 2024;149(8):e347–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ninni S, Lemesle G, Meurice T, Tricot O, Lamblin N, Bauters C. Relative Importance of Heart Failure Events Compared to Stroke and Bleeding in AF Patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):923. 10.3390/jcm10050923. IF: 3.0 Q1. PMID: 33670912; PMCID: PMC7957734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Guo Y, Tian Y, Wang H, Si Q, Wang Y, Lip GYH. Prevalence, incidence, and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation in china: new insights into the global burden of atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2015;147(1):109–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen JH, Andreasen L, Olesen MS. Atrial fibrillation-a complex polygenetic disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2021;29(7):1051–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung MK, Refaat M, Shen WK, Kutyifa V, Cha YM, Di Biase L, et al. Atrial fibrillation: JACC Council perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(14):1689–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia Z, Dang W, Jiang Y, Liu S, Yue L, Jia F, et al. Association between atrial fibrillation and the risk of cardiovascular mortality among elderly adults with ischemic stroke in Northeast china: A Community-Based prospective study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:836425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu S, Li H, Yi S, Yao J, Chen X. Comparing the efficacy of catheter ablation strategies for persistent atrial fibrillation: a bayesian analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2023;66(3):757–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seewöster T, Spampinato RA, Sommer P, Lindemann F, Jahnke C, Paetsch I, et al. Left atrial size and total atrial emptying fraction in atrial fibrillation progression. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(11):1605–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dretzke J, Chuchu N, Agarwal R, Herd C, Chua W, Fabritz L et al. Predicting recurrent atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation: a systematic review of prognostic models. Europace: European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology: journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European society of cardiology. 2020;22(5):748–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Binding C, Bjerring Olesen J, Abrahamsen B, Staerk L, Gislason G, Nissen Bonde A. Osteoporotic fractures in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with conventional versus direct anticoagulants. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(17):2150–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudo Y, Morimoto T, Tsushima R, Oka A, Sogo M, Ozaki M, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid and the outcomes in older patients undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(12):e033969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W, Saczynski J, Lessard D, Mailhot T, Barton B, Waring ME, et al. Physical, cognitive, and psychosocial conditions in relation to anticoagulation satisfaction among elderly adults with atrial fibrillation: the SAGE-AF study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019;30(11):2508–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boehmer AA, Rothe M, Ruckes C, Eckardt L, Kaess BM, Ehrlich JR. Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation in Elderly Patients: an Updated Meta-analysis of Comparative Studies. Can J Cardiol. 2024;40(12):2441–51. 10.1016/j.cjca.2024.08.263. Epub 2024 Aug 9. PMID: 39127258. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. Fekete M, Liotta EM, Molnar T, Fülöp GA, Lehoczki A. The role of atrial fibrillation in vascular cognitive impairment and dementia: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and preventive strategies. Geroscience. 2025;47(1):287–300. 10.1007/s11357-024-01290-1. Epub 2024 Aug 13. PMID: 39138793; PMCID: PMC11872872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Silva DS, Coan AC, Avelar WM. Neuropsychological and neuroimaging evidences of cerebral dysfunction in stroke-free patients with atrial fibrillation: A review. J Neurol Sci. 2019;399:172–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamioka M, Narita K, Watanabe T, Watanabe H, Makimoto H, Okuyama T, et al. Hypertension and atrial fibrillation: the clinical impact of hypertension on perioperative outcomes of atrial fibrillation ablation and its optimal control for the prevention of recurrence. Hypertens Res. 2024;47(10):2800–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European association for Cardio-Thoracic surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European society of cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European heart rhythm association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalis A, Pascoe J, Ortin MS. Really situated self-control: self-control as a set of situated skills. Phenom Cogn Sci. 2024. 10.1007/s11097-024-09989-4.

- 20.Zhu M, Bonk CJ, Doo MY. Self-directed learning in moocs: exploring the relationships among motivation, self-monitoring, and self-management. Education Tech Research Dev. 2020;68(5):2073–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groß D. The self-control and self-regulation maze: integration and importance. Pers Indiv Differ. 2021;175:110728. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Huang J, Weng F, Wen Y, Wang X, Jiang J, et al. Adherence to atrial fibrillation better care (ABC) pathway management of Chinese community elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: A Cross-Sectional study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2023;17:1813–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding Y, Li F, Fan Z, Zhang J, Gu J, Li X, et al. Factors influencing self-management behavior during the blanking period in patients with atrial fibrillation: A cross-sectional study based on the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Heart Lung: J Crit Care. 2023;58:62–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr., et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(1):104–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo Y, Wang H, Zhang H, Liu T, Liang Z, Xia Y, et al. Mobile photoplethysmographic technology to detect atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(19):2365–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, Benjamin EJ, Chyou JY, Cronin EM, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: A report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149(1):e1–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, Kim YH, Saad EB, Aguinaga L, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14(10):e275–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brinson Z, Tang VL, Finlayson E. Postoperative Functional Outcomes in Older Adults. Curr Surg Rep. 2016;4(6):21. 10.1007/s40137-016-0140-7. Epub 2016 May 4. PMID: 28344894; PMCID: PMC5362160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Sun C, Li H, Wang X, Shao Y, Huang X, Qi H, et al. Self-control as mediator and social support as moderator in stress-relapse dynamics of substance dependency. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):19852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shah S, Chahil V, Battisha A, Haq S, Kalra DK. Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation: A Review. Biomedicines. 2024;12(9):1968. 10.3390/biomedicines12091968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Klamer TA, Bots SH, Neefs J, Tulevski II, Ruijter HMD, Somsen GA, et al. Rate and rhythm control treatment in the elderly and very elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: an observational cohort study of 1497 patients. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022;47(10):100996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barley E, Lawson V. Using health psychology to help patients: theories of behaviour change. Br J Nurs. 2016;25(16):924–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Ann Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 1986.

- 35.Zhang Y, Chen YP, Wang J, Deng Y, Peng D, Zhao L. Anxiety status and influencing factors of rural residents in Hunan during the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional survey. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:564745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72(2):271–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morean ME, DeMartini KS, Leeman RF, Pearlson GD, Anticevic A, Krishnan-Sarin S, et al. Psychometrically improved, abbreviated versions of three classic measures of impulsivity and self-control. Psychol Assess. 2014;26(3):1003–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tao L, Limei C, Lixia Q, Shuiyuan X. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of brief Self-Control scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2021;29(01):83–6. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang QJ. Perceived social support scale. Chin J Behav Med Sci. 2001;10(10):41–3. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Badil Güloğlu S, Tunç S. The assessment of affective temperament and life quality in myofascial pain syndrome patients. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2022;26(1):79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weifei Ye JX. Application and evaluation of the ‘general hospital anxiety and depression scale’ in general hospital patients. Chin J Behav Medicine(Chinese). 1993;2(3):17–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smilkstein G. Family APGAR analyzed. Fam Med. 1993;25(5):293–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lv F, Zeng G, Liu SN, Zhong TL, Zhan ZQ. A study on validity and reliability of the family APGAR. Chin Public Health (Chinese). 1999;15:987–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dong F, Wu Y, Wang Q, Huang Y, Wu Q. Factors influencing patient engagement in decision-making for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2025;24(1):150–7. 10.1093/eurjcn/zvae141. PMID: 39397539. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Wynn GJ, Todd DM, Webber M, Bonnett L, McShane J, Kirchhof P et al. The European heart rhythm association symptom classification for atrial fibrillation: validation and improvement through a simple modification. Europace: European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology: journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European society of cardiology. 2014;16(7):965–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Geoffrion R, Koenig NA, Zheng M, Sinclair N, Brotto LA, Lee T, et al. Preoperative depression and anxiety impact on inpatient surgery outcomes: A prospective cohort study. Ann Surg Open. 2021;2(1):e049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holzer KJ, Bollepalli H, Carron J, Yaeger LH, Avidan MS, Lenze EJ, et al. The impact of compassion-based interventions on perioperative anxiety and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;365:476–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pilcher JJ, Bryant SA. Implications of social support as a Self-Control resource. Front Behav Neurosci. 2016;10:228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y, Zou H, Zhang Y, Fang W, Fan X. Family caregiver contribution to Self-care of heart failure: an application of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills model. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;32(6):576–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed in this study are not available to the public due to our confidentiality agreements with patients but are available from the corresponding authors on request.