Abstract

Transport of lung liquid is essential for both normal pulmonary physiologic processes and for resolution of pathologic processes. The large internal surface area of the lung is lined by alveolar epithelial type I (TI) and type II (TII) cells; TI cells line >95% of this surface, TII cells <5%. Fluid transport is regulated by ion transport, with water movement following passively. Current concepts are that TII cells are the main sites of ion transport in the lung. TI cells have been thought to provide only passive barrier, rather than active, functions. Because TI cells line most of the internal surface area of the lung, we hypothesized that TI cells could be important in the regulation of lung liquid homeostasis. We measured both Na+ and K+ (Rb+) transport in TI cells isolated from adult rat lungs and compared the results to those of concomitant experiments with isolated TII cells. TI cells take up Na+ in an amiloride-inhibitable fashion, suggesting the presence of Na+ channels; TI cell Na+ uptake, per microgram of protein, is ≈2.5 times that of TII cells. Rb+ uptake in TI cells was ≈3 times that in TII cells and was inhibited by 10−4 M ouabain, the latter observation suggesting that TI cells exhibit Na+-, K+-ATPase activity. By immunocytochemical methods, TI cells contain all three subunits (α, β, and γ) of the epithelial sodium channel ENaC and two subunits of Na+-, K+-ATPase. By Western blot analysis, TI cells contain ≈3 times the amount of αENaC/μg protein of TII cells. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that TI cells not only contain molecular machinery necessary for active ion transport, but also transport ions. These results modify some basic concepts about lung liquid transport, suggesting that TI cells may contribute significantly in maintaining alveolar fluid balance and in resolving airspace edema.

How the lung establishes and maintains homeostasis of airspace fluid is of major clinical importance. At birth, the respiratory epithelium must rapidly resorb large amounts of fluid as the fetal lung converts from fluid secretion to fluid reabsorption to survive in an air environment. After birth, establishment and maintenance of an appropriate thin fluid subphase in the alveoli is essential for gas exchange. Mass transfer of gases between the air and blood compartments in the alveoli is rapid because both the cellular anatomic barrier and the liquid alveolar lining layer are very thin and the alveolar surface area is large. Pulmonary edema, an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the air spaces that impairs gas exchange, may occur in a variety of different pathologic states, including cardiac failure, trauma, sepsis, and pneumonia. This disturbance of normal lung fluid balance can impair gas exchange and lead to morbidity and mortality. Precise regulation of lung fluid balance is therefore crucial for gas exchange, and, ultimately, for survival.

Fluid balance is driven by osmotic gradients created by active solute transport (1). It is thought that the alveolar epithelium maintains the airspace relatively free of liquid via active transport of solutes (2), with Na+ influx occurring via movement through apical epithelial Na+ channels in response to an electrochemical gradient created by basolateral Na+-, K+-ATPase. The resulting osmotic gradient leads to fluid reabsorption from the alveolar space (reviewed in refs. 3 and 4).

The surface area available for gas exchange and fluid reabsorption in the lung is large, ≈100 to 150 m2 in human lung (5). The alveolar epithelium, comprised of alveolar type I (TI) and type II (TII) cells, lines more than 99% of the internal surface area (6). TII cells, which cover 2–5% of the surface area, produce, secrete, and recycle pulmonary surfactant (reviewed in ref. 7). TII cells, which contain both Na+-, K+-ATPase (8) and amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channels (ENaC; refs. 9–11), actively transport Na+ in culture (12, 13). Very little is known about TI cells because this cell type is difficult to isolate. Current concepts about TI cells are that they are “inert” cells that provide solely a barrier function, rather than having active functions. A recent histology textbook refers to TI cells as alveolar lining cells, whose “main role … is to provide a barrier of minimal thickness that is readily permeable to gases” (14).

TI cells are large squamous cells whose thin cytoplasmic extensions (15) cover >95% of the internal surface area of the lung (6). TI cells contain aquaporins (water channels; ref. 16) and exhibit the highest osmotic water permeability of any mammalian cell type (17). There is conflicting evidence about whether TI cells contain ENaC or Na+-, K+-ATPase (8, 18). The perceived lack of molecular machinery for active Na+ transport in TI cells has been used to argue against the possibility that TI cells participate in ion transport. The currently accepted hypothesis is that TII cells maintain lung fluid homeostasis by regulating active Na+ transport in the lungs, whereas TI cells merely provide a route for passive water absorption (reviewed in ref. 4). However, because TI cells line more than 95% of lung surface area, an attractive hypothesis is that this cell type contributes to active Na+ transport across the alveolar epithelium. In the experiments reported in this communication, we present data that rat freshly isolated TI cells take up Na+ in an amiloride-inhibitable fashion and exhibit Na+-, K+-ATPase activity. Immunocytochemical localization of ENaC and Na+-, K+-ATPase and Western blotting confirm that TI cells contain the molecular machinery necessary for active Na+ absorption. Taken together, these studies support the hypothesis that TI cells are important in regulating ion and fluid transport.

Methods

Cell Isolation.

Type I cells.

TI cells were isolated from the lungs of male Sprague–Dawley rats (250 g) by enzymatic digestion, followed by both negative and positive immunoselection with magnetic beads, as described previously (17). To determine the types of cells in the preparations, cytocentrifuged preparations of isolated cells were stained with two monoclonal antibodies recognizing integral membrane proteins specific within the lung to TI cells (RTI40; ref. 19) or TII cells (RTII70; ref. 20). Preparations containing <70% TI cells or >2% TII cells were discarded. The non-TI or TII cells included macrophages, lymphocytes, and blood cells.

Type II cells.

TII cells were isolated from the lungs of male Sprague–Dawley rats (250 g) by using enzymatic digestion, panning on plates coated with rat IgG to remove macrophages and leukocytes, and negative immunoselection with magnetic beads to remove TI cells, as described previously (21). Preparations containing <80% TII cells or >1% TI cells were discarded. TI and TII cell isolates were used within 5 min for Na+ uptake and Na+-, K+-ATPase activity studies. For Western blotting, the cells were frozen and stored at −70°C.

Macrophages.

Alveolar macrophages were collected from the lungs of adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (250 g) by lavage with Ca2+Mg2+-free PBS containing 5 mM EDTA and EGTA at 37°C.

Na+ Transport.

Na+ transport was measured as described previously (22). Freshly isolated alveolar epithelial cells or alveolar macrophages were resuspended in RPMI 1640 media/20% FBS (Cell Culture Facility, University of California, San Francisco) and incubated with 1.9 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq)/ml 22Na and 10−4 M ouabain. We used 10−4 M ouabain because of previous studies showing the Ki for Na+-, K+-ATPase in rat is 10−4 M (23). In preliminary time course experiments, we determined that 22Na uptake was linear for 10–20 min. Because the number of cells was limiting (we used 1.5–2.0 million cells for each data point), we chose to study amiloride inhibition at 10 min. The cell suspension was divided, and 10−4 M amiloride was added to one portion before the addition of 22Na. At 10 min, 200-μl aliquots of the cell suspension were removed, and 0.1 μCi/ml U-14C-sucrose was added as a marker of extracellular space. After centrifugation through silica oil, triplicate 25-μl samples of the supernatant liquid were removed and the liquid and pellet were separately dissolved in 1.0 ml of 0.1 M NaOH overnight. Radioactivity was measured with gamma (Cobra II, Packard B 5003) and beta (Beckman LS 5801) counters. Protein was measured by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce). The 22Na content of the extracellular space was subtracted.

Na+-, K+-ATPase Activity.

Cellular uptake of Rb+ has been used conventionally as an indirect measurement of K+ uptake. Na+-, K+-ATPase is inhibited by ouabain; thus, measuring the ouabain-sensitive uptake of 86Rb indirectly measures Na+-, K+-ATPase activity (24). 86Rb uptake was measured by the same method as 22Na uptake; 10−4 M ouabain was added to a portion of the cell suspension to assess the ouabain-inhibitable fraction of 86Rb uptake (25). Rb+(K+) uptake was calculated as described in ref. 24. Because preliminary time course data showed that 86Rb uptake was linear for 5 min, we measured ouabain inhibition of 86Rb at this time point. 86Rb uptake was expressed as pmol Rb+(K+)/μg protein.

Immunocytochemistry.

ENaC.

Immunocytochemistry was performed on both cytocentrifuged preparations of mixed lung cells and 2-μm cryostat sections of adult rat lung. To obtain the mixed lung cell preparations, 1 mg/ml elastase in 40 ml RPMI 1640 was instilled via the trachea for 20 min, the lungs were minced to 1-mm3 tissue pieces, and the cell suspension was filtered. Cytocentrifuged preparations of mixed lung cells were prepared immediately from the lung cell suspension and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4° for 24 h. Cytocentrifuged preparations and sections of lung were processed identically for immunocytochemistry. Antigen retrieval was performed (26) before blocking for 1 h in 10% normal goat serum in buffer A, composed of PBS/0.1% BSA/0.3% Triton X-100. Slides were washed three times with buffer A and stained sequentially with three different primary antibodies to colocalize ENaC to specific alveolar epithelial cell types: (i) antibody against an ENaC subunit, (ii) RTI40 (marker for TI cells), and (iii) RTII70 (marker for TII cells). The ENaC antibodies, polyclonal rabbit antibodies against peptides specific to the α-, β-, or γ-subunits of ENaC, have been previously characterized (27). Slides were washed three times with buffer A between each antibody; secondary antibodies were diluted in buffer A. Order of antibody staining was as follows: (i) rabbit anti-ENaC; (ii) goat anti-rabbit IgG:biotin (Zymed), 1:200; (iii) streptavidin-Alexa 680 (blue), 1:1000; (iv) mouse monoclonal IgG1 anti-RTI40; (v) goat anti-mouse IgG1-Alexa 594 (red), 1:1000; (vi) mouse monoclonal IgG3 anti-RTII70; and (vii) goat anti-mouse IgG3-Alexa 488 (green), 1:1000. Samples were scanned with a Leica TCS-SP2 scanning spectral confocal microscope by using each laser singly and sequentially so that emission data for each fluorophore was collected individually. With this methodology, there was no spectral “spill” among the channels. Maximum intensity extended focus images were obtained by using Imaris software (Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland). The three separate emission patterns were superimposed by using imaris software to create a composite image of the three separate scans.

Na+-, K+-ATPase.

Immunocytochemical studies were performed by using commercially available rabbit polyclonal antibodies to two subunits of Na+-, K+-ATPase (anti-Na+-, K+-ATPase α-1 and anti-Na+-, K+-ATPase β-1, Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). The protocol for immunostaining with these two antibodies was identical to that for the ENaC subunits.

Western Blot Analysis.

Cell pellets were freeze-thawed five times. Two hundred microliters of 20 μg/ml DNase in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) was added to the cell pellets, and the suspension was placed on ice for 30 min. The cell suspensions were dounce homogenized and triturated through a 26-gauge needle before adding loading buffer and heating the samples at 60°C for 15 min. Protein bands were resolved on a 10% NuPage Bis-Tris ([bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]tris(hydroxymethyl)methane) gel (Invitrogen) at 100 V for 2 h in Mops (Nupage) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane in NuPage transfer buffer at 25 V for 2 h. The membrane was blocked in a solution containing 1% powdered milk, 0.4% fish gelatin, 0.1% BSA, and 0.5 mM Tris base (buffer B) overnight at 4°C, and primary antibodies against ENaC subunits were added in buffer B overnight at room temperature. The membrane was washed with 20 mM Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.4) with 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST), incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (Vector Laboratories; 1:2000 in TBST) for 1 h, washed, and incubated in SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) for 5 min before autoradiography and quantitation by PhosphorImager analysis (STORM scanner, imagequant software, Molecular Dynamics).

Results

Freshly Isolated Alveolar TI Cells Exhibit Amiloride-Inhibitable Na+ Uptake.

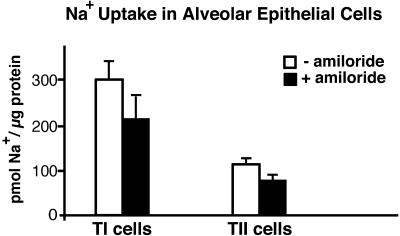

At 10 min, Na+ uptake was 300 ± 32 pmol/μg protein (mean ± SE, n = 4; Fig. 1). Amiloride (10−4 M) inhibited 22Na uptake by an average of 29% (P < 0.01, paired t test). Results from 22Na uptake in freshly isolated TII cells with and without amiloride (10−4 M) at 10 min are shown for comparison. At 10 min, Na+ uptake in TII cells was 118 ± 7 pmol/μg protein (mean ± SE, n = 6). Amiloride (10−4 M) inhibited 22Na uptake in TII cells by an average of 28% (P < 0.05, paired t test) in these experiments. Previous reports of 22Na uptake in freshly isolated TII cells (24, 28) have used cells from rabbits, which have a higher amiloride-inhibitable fraction of Na+ transport in intact lung (29) than do rats (30, 31). Nevertheless, our results with rat TII cells in these studies are similar to these reports. 22Na uptake per microgram of protein in freshly isolated TI cells was ≈2.5 times that in TII cells (P < 0.001). Alveolar macrophages did not show amiloride-sensitive 22Na uptake (data not shown, n = 2).

Figure 1.

Uptake of Na+ by TI and TII cells in vitro. Na+ uptake was performed as described in Methods. Data are expressed as mean ± SE, n = 4 for TI cells and n = 6 for TII cells. Na+ uptake in both TI and TII cells was significantly inhibited by amiloride (29% in TI with P < 0.001; 28% in TII with P < 0.03). Na+ uptake in TI cells per microgram of protein was greater than that in TII cells (P < 0.01).

TI Cells Contain All Three Subunits of ENaC.

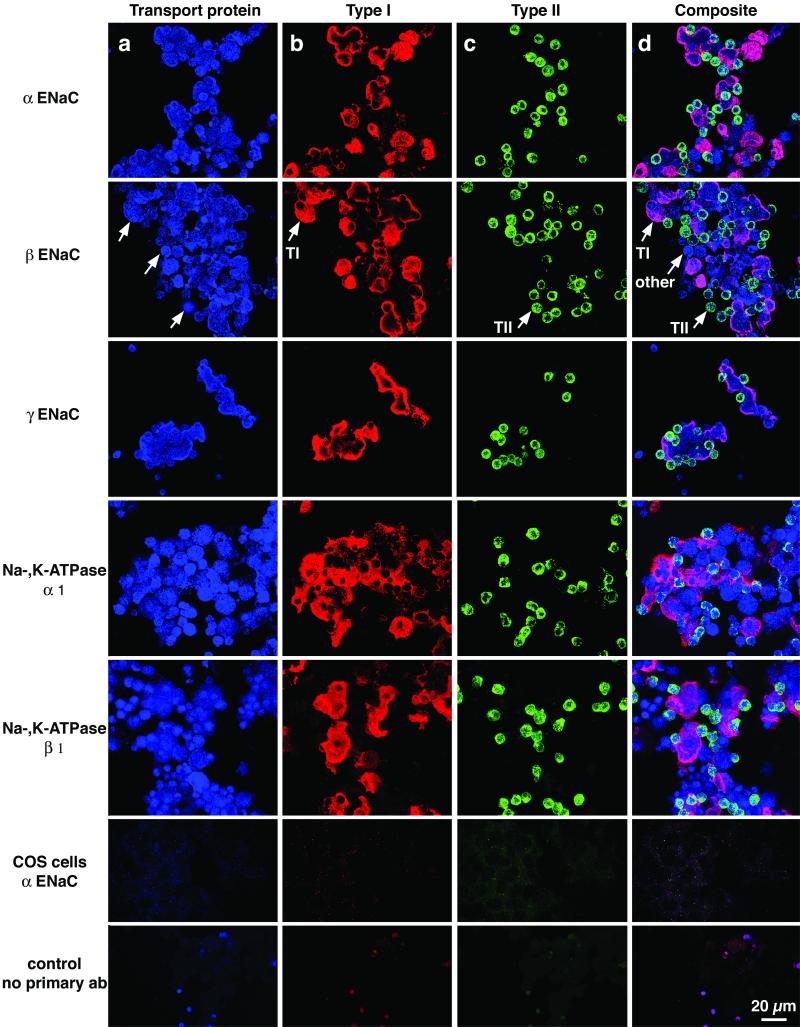

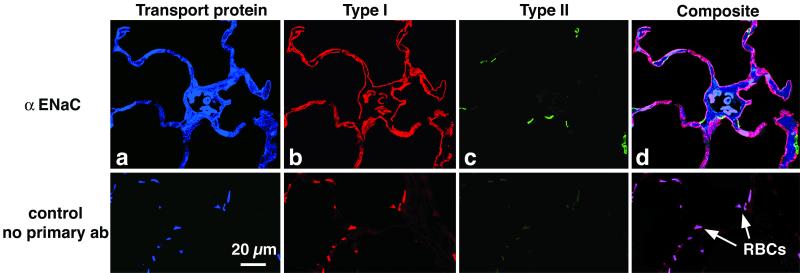

From the amiloride-sensitive pattern of Na+ uptake, we inferred that there was an amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel present in TI cells. ENaC is the prototypical epithelial Na+ channel (32). Immunocytochemical studies were performed with both cytocentrifuged mixed lung cell preparations (Fig. 2) and lung tissue (Fig. 3), by using antibodies specific to ENaC peptides and confocal scanning laser microscopy. We used preparations of mixed lung cells so that TI and TII cells subjected to identical experimental manipulation could be seen in the same image. Fig. 2 shows a preparation of isolated mixed lung cells, demonstrating localization of each ENaC subunit (top three rows) in both TI and TII cells, which are easily identifiable by cell-specific antibody staining. For details, see Fig. 2 legend. Fig. 3 shows colocalization of αENaC and TI cells in situ. We obtained similar results in situ with βENaC and γENaC (results not shown).

Figure 2.

Colocalization of subunits of ENaC and Na+-, K+-ATPase with markers specific for TI and TII cells. The preparations of isolated cells used in these experiments contain not only TI cells and TII cells, but various other lung cells liberated by enzymatic digestion, including airway cells, macrophages, and cells from the vascular and interstitial compartments. Immunocytochemistry was performed as described in Methods. The same field of cells is shown in each row, stained with three antibodies and three different fluorophores specific for each antibody. The colors shown in each column are the result of scanning with the appropriate laser for each fluorophore. In the various columns, one can appreciate staining for (a) antibodies against various channel or pump proteins (blue color); (b) RTI40, a marker for TI cells (red color); and (c) RTII70, a marker for TII cells (green color). Column d shows a composite image, created by superimposition of the three separate images shown in columns a, b, and c. Arrows indicate one representative TI cell, one TII cell, and a cell that is neither a TI nor a TII cell. Every TI and TII cell expressed all of the pump/channel proteins. This fact can be appreciated most easily when one looks in column d at the spectral shifts caused by overlapping red (TI) or green (TII) markers with the blue (pump/channel) protein. In this composite image, colocalization of a transport protein subunit (ENaC or Na+-, K+-ATPase) with either TI or TII cell plasma membrane causes a color shift, indicating colocalization of the protein subunit with TI or TII plasma membranes. For example, combination of blue (subunit) with red (TI) is pinkish purple, whereas a combination of blue (subunit) with green (TII) is bluish green. Specific antibodies are labeled in rows 1–5: row 1, αENaC; row 2, βENaC; row 3, γENaC; row 4, α1-Na+-, K+-ATPase; row 5, β1-Na+-, K+-ATPase; row 6, Cos7 cells stained for αENaC; and row 7, no primary antibody control panel with mixed lung cells.

Figure 3.

αENaC is present in TI cells in situ. (Upper) A 2-μ-thick cryostat section of rat lung incubated with primary and secondary antibodies and scanned sequentially as described in Methods. The organization is the same as described for Fig. 2: (a) αENaC (blue); (b) RTI40 (TI cell apical plasma membrane; red); (c) RTII70 (TII cell plasma membrane; green); and (d) computer-generated composite image. (Lower) A 2-μ-thick section prepared without primary antibodies but with all three secondary antibodies. Note that erythrocytes (RBCs) autofluoresce similarly with and without primary antibody.

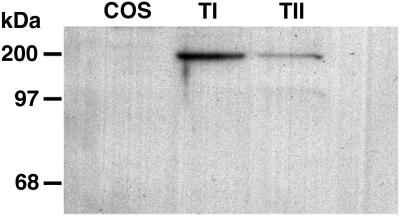

Western blotting of αENaC was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions for NuPage gels, after electrophoresis of proteins in a 10% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel. In the manufacturer's protocol, proteins are reduced with 1M DTT at 60°C for 15 min. Under these conditions, members of the ENaC/degenerin superfamily are not totally reduced and can still be detected as oligomers, mostly dimers (33). Accordingly, αENaC in TI cells and TII cells has a major band with an apparent molecular weight of ≈150,000–200,000. By PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) analysis, there was ≈3 times the amount of αENaC per microgram of protein in TI cells than there was in TII cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Western blot for αENaC in Cos, TI, and TII cells. Forty-micrograms of protein from Cos7, TI, or TII cells was added to each lane, and bands were resolved on a 10% Bis-Tris gel, transferred to nitrocellulose paper, and stained with an antibody specific for αENaC as described in Methods. A band at ≈180–200 kDa is seen in TI and TII cell lanes. By PhosphorImager quantitation, TI cells express ≈3 times the amount of αENaC found in TII cells.

TI Cells Exhibit Na+-, K+-ATPase Activity.

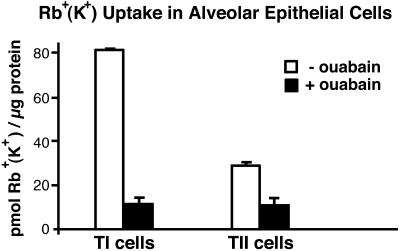

Rb+ (K+) uptake in TI cells at 5 min, calculated from 86Rb uptake as in (24), was 82 ± 0.4 pmol/μg protein (mean ± SE, n = 2 for each cell type). In the presence of 10−4 M ouabain, uptake was inhibited by an average of 85% (P < 0.02). Ouabain inhibited 86Rb uptake in TII cells by an average of 64% (Fig. 5). TI cells exhibited ≈3 times the 86Rb uptake per microgram of protein of that found in TII cells (P = 0.01).

Figure 5.

Rb+ uptake in freshly isolated TI and TII cells. Rb+ uptake in freshly isolated TI and TII cells at 5 min with and without ouabain (10−4 M). Data are expressed as mean ± SE, n = 2 for each cell type. In T1 cells, ouabain inhibited Rb+ uptake by an average of 85% (P < 0.02)

TI Cells Contain Both αl- and β1-Subunits of Na+-, K+-ATPase.

The presence of ouabain-inhibitable Rb+ uptake in TI cells suggested the presence of Na+-, K+-ATPase. Immunocytochemical studies of both isolated cells (Fig. 2, rows 4 and 5) and cryostat sections of lung (data not shown) demonstrate that TI cells contain both α1- and β1-subunits of Na+-, K+-ATPase.

Discussion

Transport of lung liquid is essential for both normal pulmonary physiologic processes (maintenance of an appropriate liquid alveolar subphase, the transition from an intrauterine to air environment at birth) and for resolution of pathologic processes, such as pulmonary edema. The large internal surface area of the lung is comprised of two types of alveolar epithelial cells, TI and TII cells; TI cells line >95% of this surface, TII cells <5%. Fluid transport is believed to be regulated by ion transport, with water movement occurring passively. In this paradigm, Na+-, K+-ATPase provides the electrochemical gradient for transcellular transport of Na+, with Na+ entering epithelial cells from the air surface of the lung (34–36). Based on the extensive data regarding ion transport in TII cells (reviewed in ref. 4) and the previously accepted concept that TI cells lack Na+-, K+-ATPase (ref. 8 and see below), the current concept has been that TII cells are the main sites of ion transport in the lung, with water movement following passively across the alveolar epithelium via aquaporins (reviewed in ref. 4).

Because TI cells line the majority of the internal surface area of the lung, we hypothesized that this cell type could be important in the regulation of lung liquid homeostasis. By using the method we previously developed to isolate TI cells for the measurement of osmotic water permeability (17), we have measured both Na+ and K+ (Rb+) transport in isolated TI cells and, in concurrent experiments, in TII cells. To our knowledge, these studies of ion transport in TI cells have not been previously documented.

We used techniques of both negative and positive immunoselection to produce preparations of either TI cells with a minimal number of TII cells or TII cells with a minimal number of TI cells. The preparations of TI cells used in these experiments contained 70–80% TI cells; the remainder of the cells in the preparations were mostly macrophages, lymphocytes, and TII cells (<2%). We found no amiloride-inhibitable uptake in macrophages over time (results not shown), suggesting that Na+ uptake in our cell preparations did not result from macrophage contamination.

TI cells take up Na+ in an amiloride-inhibitable (≈29%) fashion. Na+ uptake per microgram of protein in TI cells is ≈2.5 times that of TII cells (Fig. 1). Amiloride-inhibition of transport suggests the presence of an amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel. ENaC, the prototypical amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel, is comprised of three subunits: α, β, and γ. Of these, αENaC is functionally the most important. Na+ transport can be induced in Xenopus oocytes by injection of αENaC mRNA alone (37, 38), and null mutants of αENaC in mice, in contrast to null mutants of the two other subunits, are lethal, in part because of defective neonatal lung liquid clearance (39–42). By immunocytochemistry, TI cells contain all three subunits of ENaC (Fig. 2). By semiquantitative Western blotting (Fig. 4), TI cells contain ≈3 times αENaC per microgram of protein of that found in TII cells. Previous studies of ENaC distribution in the lung have reported conflicting results regarding localization of the various subunits to alveoli and, within alveoli, to specific alveolar cells. By using radioisotopic in situ hybridization or immunocytochemistry, investigators have concluded variously that there is no expression of any subunit in alveoli (18), that there is selective expression of only αENaC (43), of both αENaC and γENaC (9), or of all three subunits (44). Although Watanabe et al. (44) concluded that αENaC was expressed in TII cells, the relatively low spatial resolution of the methodology does not permit definitive cellular localization from these data. In an abstract, Borok et al.** reported that isolated TI cells contain αENaC.

We were able to establish specific alveolar epithelial cellular localization of ENaC subunits by combining techniques of antigen retrieval and confocal laser scanning microscopy with use of peptide-specific antibodies against each ENaC subunit and antibodies against integral membrane proteins specific within the lung to TI or TII cells. Our results with isolated cells (Fig. 2), clearly demonstrate that both TI and TII cells contain all three ENaC subunits. All of the TI cells and the TII cells expressed each ENaC subunit. Although it seems unlikely that expression of these proteins could be induced solely by the 30-min period of cell isolation, we also examined lung tissue in situ to address this possibility. Fig. 3 shows the colocalization of αENaC with a marker for TI cell apical plasma membranes. We obtained similar results with βENaC and γENaC (results not shown), demonstrating that in situ TI cells contain all three subunits of ENaC.

Na+-, K+-ATPase provides the electrochemical driving force for ion transport. Based on a report by using ultrastructural enzyme cytochemistry (8), it has been generally accepted either that TI cells do not express Na+-, K+-ATPase or that TII cells exhibit much greater Na+-, K+-ATPase activity than do TI cells. In preliminary data, Borok et al.** reported that TI cells contain α1- and β1-subunits (but not the α2-subunit) of Na+-, K+-ATPase. Ridge et al. (45) found that TII cells cultured on plastic, which lose phenotypic characteristics of TII cells and acquire some phenotypic characteristics of TI cells, express α1-, α2-, and β1-subunits. In the current series of experiments, we found that Rb+ uptake in isolated TI cells was inhibited ≈85% by ouabain (Fig. 5). These data support the concept that TI cells have functional Na+-, K+-ATPase. By immunocytochemical methods, both TI and TII cells contain the α1-and β1-subunits of Na+-, K+-ATPase (Fig. 2).

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that TI cells not only contain molecular machinery necessary for active ion transport, but also transport ions. Quantitatively, isolated TI cells contain more αENaC and transport more Na+ and Rb+ per microgram of protein than do isolated TII cells. However, the interpretation of quantitative comparisons between TI and TII cells in these studies and the extrapolation of these data to cellular functions in vivo must be made with caution. Isolated TI and TII cells have been subjected to treatment with enzymes, have lost polarized distribution of plasma membrane proteins, and probably have different surface area to protein ratios. Although the quantitative results obtained from experiments with isolated cells may not precisely reflect relative cellular functions in vivo, the data obtained with isolated cells support the concept that TI cells are important in lung liquid transport. By extension from these data, TI cells are likely to play an active, rather than a passive, role in mediating lung liquid homeostasis. These findings in part explain why, when TI cells are damaged in acute lung injury, alveolar flooding occurs and also why the ability to clear lung liquid may correlate with survival (46). In conclusion, our studies provide evidence supporting the hypothesis that active Na+ transport by TI cells is an important factor in the maintenance of alveolar fluid balance and in the resolution of pulmonary edema.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the American Lung Association (M.D.J.) and the National Institutes of Health (R01HL 57426 and PPG HL 24075).

Abbreviations

- TI

alveolar epithelial type I cell

- TII

alveolar epithelial type II cell

- ENaC

epithelial Na+ channel

Footnotes

Borok, Z., Foster, M. J., Zabaski, S. M., Veeraraghavan, S., Lubman, R. L. & Crandall, E. D. (1999) Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 159, A 467 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Diamond J M. J Membr Biol. 1979;51:195–216. doi: 10.1007/BF01869084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saumon G, Basset G. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:1–15. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matalon S, Benos D J, Jackson R M. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:L1–L22. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.1.L1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matalon S, O'Brodovich H. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:627–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weibel E R. Morphometry of the Human Lung. Berlin: Springer; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crapo J D, Young S L, Fram E K, Pinkerton K E, Barry B E, Crapo R O. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:S42–S46. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.2P2.S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright J R, Dobbs L G. Annu Rev Physiol. 1991;53:395–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.002143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneeberger E E, McCarthy K M. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60:1584–1589. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.5.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farman N, Talbot C R, Boucher R, Fay M, Canessa C, Rossier B, Bonvalet J P. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C131–C141. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.1.C131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yue G, Russell W J, Benos D J, Jackson R M, Olman M A, Matalon S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8418–8422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talbot C L, Bosworth D G, Briley E L, Fenstermacher D A, Boucher R C, Gabriel S E, Barker P M. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:398–406. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.3.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman B E, Crandall E D. Am J Physiol. 1982;243:C96–C100. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1982.243.1.C96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason R J, Williams M C, Widdicombe J H, Sanders M J, Misfeldt D S, Berry L C., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6033–6037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.6033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junqueira L C U, Carneiro J, Kelley R O. Basic Histology. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1998. p. 338. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone K C, Mercer R R, Gehr P, Stockstill B, Crapo J D. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:235–243. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King L S, Nielsen S, Agre P. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2183–2191. doi: 10.1172/JCI118659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobbs L G, Gonzalez R, Matthay M A, Carter E P, Allen L, Verkman A S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2991–2996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renard S, Voilley N, Bassilana F, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. Pflugers Arch. 1995;430:299–307. doi: 10.1007/BF00373903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobbs L G, Williams M C, Gonzalez R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;970:146–156. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(88)90173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobbs L G, Pian M S, Maglio M, Dumars S, Allen L. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L347–L354. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.2.L347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutierrez J A, Gonzalez R F, Dobbs L G. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L196–L202. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.2.L196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Widdicombe J H, Basbaum C B, Highland E. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:C184–C192. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1981.241.5.C184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Repke K, Est M, Portius H J. Biochem Pharmacol. 1965;14:1785–1802. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(65)90269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bland R D, Boyd C A. J Appl Physiol. 1986;61:507–515. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman D L, Widdicombe J H, Bland R D. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:L481–L487. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.259.6.L481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi S R, Cote R J, Taylor C R. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:931–937. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbry P, Hofman P. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G571–G585. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.3.G571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matalon S, Kirk K L, Bubien J K, Oh Y, Hu P, Yue G, Shoemaker R, Cragoe E J, Jr, Benos D J. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C1228–C1238. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.5.C1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smedira N, Gates L, Hastings R, Jayr C, Sakuma T, Pittet J F, Matthay M A. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:1827–1835. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.4.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayr C, Garat C, Meignan M, Pittet J F, Zelter M, Matthay M A. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:2636–2642. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.6.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pittet J F, Wiener-Kronish J P, McElroy M C, Folkesson H G, Matthay M A. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:663–671. doi: 10.1172/JCI117383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benos D J, Saccomani G, Sariban-Sohraby S. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10613–10618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coscoy S, Lingueglia E, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8317–8322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basset G, Crone C, Saumon G. J Physiol. 1987;384:311–324. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basset G, Bouchonnet F, Crone C, Saumon G. J Physiol. 1988;400:529–543. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthay M A, Berthiaume Y, Staub N C. J Appl Physiol. 1985;59:928–934. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.3.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lingueglia E, Voilley N, Waldmann R, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. FEBS Lett. 1993;318:95–99. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canessa C M, Horisberger J D, Rossier B C. Nature (London) 1993;361:467–470. doi: 10.1038/361467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hummler E, Barker P, Gatzy J, Beermann F, Verdumo C, Schmidt A, Boucher R, Rossier B C. Nat Genet. 1996;12:325–328. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDonald F J, Yang B, Hrstka R F, Drummond H A, Tarr D E, McCray P B, Jr, Stokes J B, Welsh M J, Williamson R A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1727–1731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barker P M, Nguyen M S, Gatzy J T, Grubb B, Norman H, Hummler E, Rossier B, Boucher R C, Koller B. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1634–1640. doi: 10.1172/JCI3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher M H, Amend A M, Bach T J, Barker J M, Brady E J, Candelore M R, Carroll D, Cascieri M A, Chiu S H, Deng L, et al. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2387–2393. doi: 10.1172/JCI2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsushita K, McCray P B, Jr, Sigmund R D, Welsh M J, Stokes J B. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:L332–L339. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.2.L332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watanabe S, Matsushita K, Stokes J B, McCray P B., Jr Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G1227–G1235. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.6.G1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ridge K M, Rutschman D H, Factor P, Katz A I, Bertorello A M, Sznajder J L. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L246–L255. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.1.L246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthay M A, Wiener-Kronish J P. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:1250–1257. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]