Abstract

Matching the activity of the genes with biomechanics and physiology is an effective way to use cDNA microarray technology. Required are data on the change of activities of genes associated with specific physiological functions with respect to a continuous variable such as time. For each pair of data (gene and physiological function) as functions of time, we can compute a coefficient of correlation, R. The correlation is perfect if R is +1 or −1; it is nonexistent if R = 0. By evaluating R for every gene in a microarray, we can arrange the genes in the order of the number R, thus learning which genes are best correlated with the mechanical or physiological function. We illustrate this procedure by studying the blood vessels in the lung in response to pulmonary hypoxic hypertension, including the remodeling of vascular morphometry, the elastic moduli, and the zero-stress state of the vessel wall. For each physiological function, we identify the top genes that correlate the best. We found that different genes correlate best with a given function in large and small arteries, and that the genes in pulmonary veins which respond to arterial functions are different from those in pulmonary arteries. We found one set of genes matching the remodeling of arterial wall thickness, but another set of genes whose integral of activity over time best fit the wall thickness change. Our method can be used to study other thought-provoking problems.

Keywords: cDNA microarray‖blood vessel morphometric parameters‖blood vessel elasticity‖blood vessel opening angle at zero-stress state‖pulmonary hypertension

The ultimate aim of using the cDNA microarray technology to obtain gene expression data is to correlate genes with physiological functions. The purpose of this article is to show how this correlation can be pursued. We describe both the chosen physiological functions of a tissue and the activities of the genes of the tissue as continuous functions of time. Then we compare these continuous functions and determine their correlation coefficients. The correlation coefficients allow us to line up the genes in the order of the correlation coefficients for each physiological function.

In this article, a survey of the association of gene activity with the functions of blood vessels is presented. For each blood vessel, we consider the following functions of time, xi(t), i = 1, 2, 3, … 8:

- x1(t)

the blood pressure;

- x2(t)

the oxygen concentration in the blood;

- x3(t)

the opening angle of a blood vessel defining its zero-stress state;

- x4(t)

the thickness of the intima-media layer;

- x5(t)

the thickness of the adventitia layer;

- x6(t)

the inner circumferential length at zero-stress state;

- x7(t)

the outer circumferential length at zero-stress state;

- x8(t)

Young's moduli of pulmonary arteries.

Each of these variables has a stable static equilibrium (homeostatic) value in vivo under physiological conditions. When a disturbance is introduced at a time t = 0, these variables change; and the changes are correlated with gene activity. We took tissue samples at time t, and measured the gene activity with a cDNA microarray method to obtain the history of the activity of each gene. Let the results be denoted by yj(t), which are functions of time, and the gene numbers j, j = 1, 2, 3, … 9,600 in our case. Now we have two sets of function xi(t) and yj(t). We can compare any pair of functions to see whether they are similar or not. For this purpose, we define a correlation coefficient R(xi, yj) by the formula

|

1 |

in which T is the total period covered by the correlation. The correlation is perfect if R = ±1; it is poor if the absolute value of R is small. For any given xi(t), we can arrange the genes in the order of the cardinal number R(xi, yj). To understand the function xi(t), we focus our attention on those genes that are closer to R = 1 or R = −1.

All of the functions xi(t) are

not of the same character. Some morphometric functions such as

x3 … x8

that describe the local tissue remodeling are strictly local. These

variables are probably more directly correlated with the gene

expressions of the local tissue. The blood pressure

x1(t), however, varies with the

total circuit. It would be interesting to inquire whether the genes

sense xi, or its rate of change,

dxi(t)/dt,

and control xi(t) by

yj, or by the integral of

yj. Thus, we should also investigate the

correlation coefficient of the derivatives and integrals of

xi and yj,

e.g.,

Rij(dxi/dt,

yj),

Rij(xi,

dyj/dt),

Rij(dxi/dt,

dyj/dt), and

Rij(xi,

∫ yj(t)dt). Correlation of the

derivatives and integrals of xi and

yj can be done according to Eq. 1 by

appropriate substitutions of xi,

yj with their derivatives or integrals.

yj(t)dt). Correlation of the

derivatives and integrals of xi and

yj can be done according to Eq. 1 by

appropriate substitutions of xi,

yj with their derivatives or integrals.

Getting physiological and gene expression data on tissue remodeling in vivo of the type studied here is very expensive in time, labor, and cost; therefore, the data on tissue remodeling are often sparse. Blood pressure data recorded digitally are, however, extremely rich, but stochastic and nonstationary. To use Eq. 1, we handled the sparse data by curve fitting with proposed analytical formulas, whereas the stochastic data were dealt with by using our intrinsic mode function method (1–3), which is explained in Materials and Methods.

The principle we put forward is that to discover which genes' activity matches a physiological function best, we first look for a continuous variable such as time, then perform experiments to obtain gene activities and physiological functions as functions of time. The correlation allows an assessment of coupling.

Identification of genes with physiology and pathology is common. A popular method is the self-organizing map (SOM) method of Tamayo et al. (4). We tried the SOM method on our specimens (5, 6), found it interesting, but not sufficiently specific. The method here is simpler to interpret.

Materials and Methods

We induced a rapid increase of pulmonary arterial blood pressure in the lungs of rats living in a modified commercial chamber (Snyder, Denver, CO) by suddenly decreasing the oxygen concentration in the chamber (2, 3, 7, 8). The cardiac output and systemic blood pressure did not change much (9, 10). We studied the remodeling of vascular tissues in response to this sudden change of blood pressure and the associated gene activities as functions of time. We then calculated the correlation coefficients of these functions of time and determined the genes that are most relevant to physiology.

The details of the animal protocol and the regulatory approval were reported (1–3, 5, 6, 11). Under anesthetization, a catheter was implanted into the pulmonary arterial trunk of the rat through its jugular vein and sutured to the back so that after awakening the rat could move freely and eat and drink normally. Blood pressure data were recorded at 100 points per sec chronically. Each oxygen level change was accomplished in 1.0 ± 0.5 min. At a scheduled time, the rat was killed with an overdose of an i.p. injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg of body weight). Then, vascular tissues were collected and prepared for measurements of morphometric and mechanical properties and gene expression. The total RNAs from the left pulmonary arteries and veins (≈50 mg of tissue per sample) were extracted by using the Stratagene Micro RNA isolation kit (no. 200344).

We measured the variables x1(t), x2(t), … x8(t) (3, 5, 6, 11) and used them in this article. Perhaps x3(t), the opening angle, needs an explanation. When an artery is cut into rings and a ring is cut along a radial line, it opens up into a sector, which represents the vessel wall at zero-stress. By taking the midpoint of the inner wall as an origin and erecting two radius vectors from this origin to the tips of the inner wall in a normal cross section, we obtain a subtended angle, x3(t), the opening angle of the vessel. Rounding up the opening sector back into a tube would generate residual stresses. Hence, the opening angle is a measure of the residual stresses and one of the best measures of tissue remodeling (12).

Measurement of Gene Activity.

Gene activity was measured by a cDNA microarray method with enzyme colorimetry detection (13). The mRNAs of the pulmonary arteries and veins were amplified by using an in vitro transcription method (14) before they were labeled with biotin during the reverse transcription process. To have better signal to noise ratios, the colorimetric signals were amplified by a modified catalyzed reporter deposition (CARD) method (15, 16). The details of the procedures for in vitro transcription and the CARD signal amplification methods are described in ref. 17. The labeled cDNA derived from the tissues were then hybridized to 9,600 probes in a microarray.

The array images were digitized by a 3,000 dots per inch flatbed scanner (PowerLook 3000, UMAX, Taiwan), and quantitative information was obtained by an image analysis software GENEPIX PRO 3.0 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). The hybridization condition and data analysis were described in detail (5). The gene activity was expressed in an arbitrary scale of 3,000–35,000. The sum total of the scores of all genes on a chip was considered as an indication of the total amount of a sample. The data from samples of the same tissue were normalized for sample sizes.

Mathematical Representation of Experimental Results.

To use Eq. 1, we first fit the physiological and gene activity data with mathematical expressions by the method of least-square errors. The expression for the mean pulmonary blood pressure, Mk(t), after a step decrease of oxygen tension in breathing gas, is as given in ref. 2, for t ≥ 0,

|

2 |

in which A, B, C, T1, and T2 are constants. The expression for the remodeling change of the opening angle, as well as that of the thickness of the media and adventitia, is given by the following equation as in ref. 5:

|

3 |

where A1, … A5 are constants, T1 is the time for the first peak, T2 is the time for the second peak. We arrived at these formulas after trying many other methods.

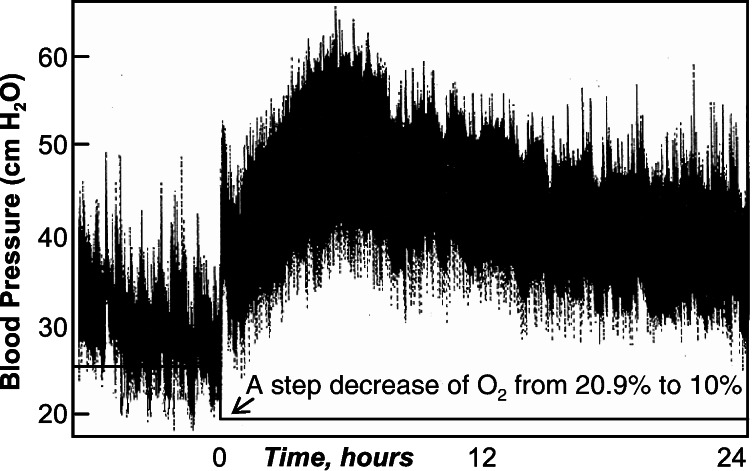

The blood pressure signal, as shown in Fig. 1, is very complex. It is nonstationary and stochastic. To explain the matching of gene activity and the blood pressure as presented in Figs. 3 and 4 and Tables 1 and 2, an explanation of the mathematics whose details are given in refs. 1–3 is given here. Very briefly, denoting the blood pressure as X(t), we compute an upper envelope that connects the successive local maxima of X(t), and a lower envelope that connects all of the minima. The mean of the envelopes is designated as m(t). We then compute X(t) − m(t) = h(t) and treat h(t) as new data, compute the new envelopes and a new mean, and iterate until it converges. The convergent result is called the first intrinsic mode C1(t), which has a zero local mean. Next, we compute X(t) − C1(t) and treat it as new data, for which the second intrinsic mode C2(t) is determined. The process ends after n steps, when Cn(t) is nonoscillatory,

|

4 |

Every term has a zero local mean. The successive modes have successively fewer zero crossings. Cn(t) is a trend. Cn + Cn-1 is also a trend with some oscillations whose local mean is zero. We define the mean trend of order k by the formula

|

5 |

and the oscillations about the mean Mk(t) as

|

6 |

Then we computed the Hilbert transform of Xk(t), whose amplitude is a function of frequency and time, Hk(ω, t). The integral of the square of Hk(ω, t) over all frequencies is defined as the oscillatory energy about the kth order mean:

|

7 |

Ek(t) is a stochastic variable that can be handled in the same way as X(t), and orders of its mean trend are defined in turn.

Figure 1.

A record of the pulmonary arterial blood pressure of a rat (rat code: 050698) subjected to step lowering of oxygen concentration in breathing gas.

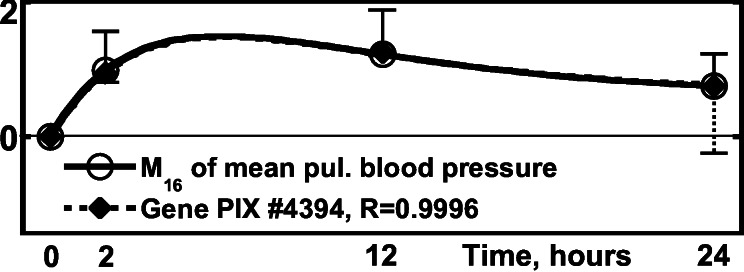

Figure 3.

Activity of the gene PIX no. 4394 (phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase

β-subunit gene) vs. the 16th order mean of the blood

pressure,

M16BP(t) above

the steady in vivo value at t

> 0. ○, normalized

M16BP, defined as

[(1/N)∑ (ΔM16BP)2]−1/2,

fitted by a solid line, one SEM flag up. ⧫, normalized gene

activity, defined as Δ(Gene

Activity)⋅[(1/N)∑

(ΔM16BP)2]−1/2,

fitted by a solid line, one SEM flag up. ⧫, normalized gene

activity, defined as Δ(Gene

Activity)⋅[(1/N)∑ (Δ(Gene

Activity)2]−1/2, fitted by dash

line, one SEM flag down.

(Δ(Gene

Activity)2]−1/2, fitted by dash

line, one SEM flag down.

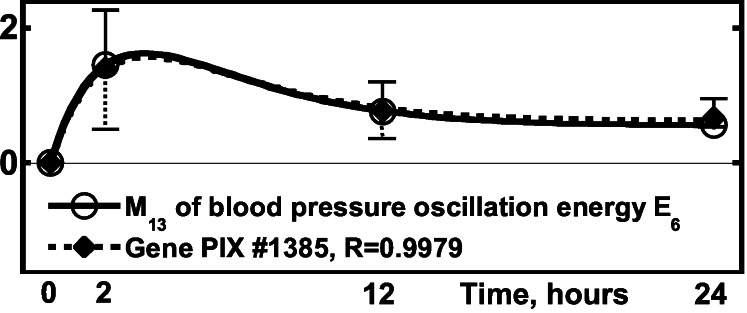

Figure 4.

Activity of the gene PIX no. 1385 (wee1 + homolog gene)

vs. the blood pressure oscillation energy, the 13th order mean of the

6th order of energy of oscillation,

E6, defined by Eqs. 4–7

and ref. 3. ○,

[(1/N)∑ (ΔE6)2]−1/2,

one SEM flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(ΔE6)2]−1/2,

one SEM flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

Table 1.

Top 5 pulmonary artery genes of +R[xi(t)yj(t)]

| Physiol. entity | Range of correlation coefficient | Identification PIX no. of the 5 top genes |

|---|---|---|

| x1(t)-kth mean of the blood pressure Mk (0–24 h) | ||

| M10BP(t) | (0.9997; 0.9969) | 4804 1385 7791 8193 4382 |

| M14BP(t) | (0.9997; 0.9963) | 4804 7791 8193 1385 7167 |

| M16BP(t) | (0.9999; 0.9995) | 1974 4394 5546 5362 7122 |

| x1(t)-kth mean of energy of the oscillations E6 (0–24 h) | ||

| M9 of E6(t) | (0.9999; 0.9975) | 2826 8915 4497 256 8395 |

| M13 of E6(t) | (0.9986; 0.9964) | 4382 1385 4575 2603 2826 |

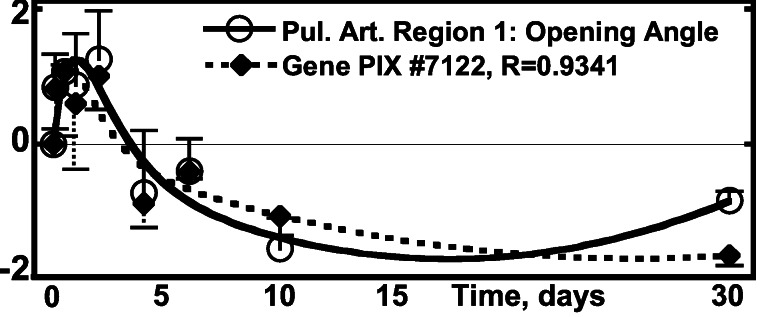

| x3(t)-Opening angle of pulmonary arteries (0–30 d) | ||

| OA-r1(t) | (0.9341; 0.8200) | 7122 5994 9217 6095 8556 |

| OA-r2(t) | (0.9677; 0.8521) | 7122 5994 2832 6095 3178 |

| OA-r3(t) | (0.9096; 0.8206) | 7122 8408 6095 8343 7266 |

| OA-r4(t) | (0.9149; 0.8133) | 7122 6095 6567 8408 7266 |

| OA-r5(t) | (0.8404; 0.7815) | 6095 2832 7122 7266 6380 |

| OA-r6(t) | (0.8903; 0.8549) | 558 4804 343 6280 4594 |

| OA-r7(t) | (0.9403; 0.8942) | 4198 6477 4804 1335 5254 |

| OA-r8(t) | (0.9350; 0.9205) | 1344 1288 4198 1335 5016 |

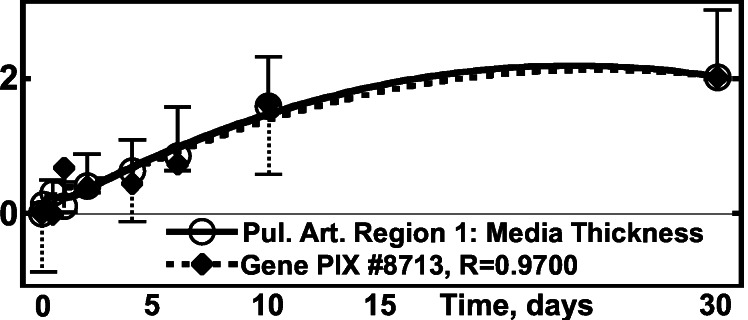

| x4(t)-Media thickness of pulmonary arteries (0–30 d) | ||

| MT-r1(t) | (0.9700; 0.9629) | 8713 4438 9172 5591 3685 |

| MT-r2(t) | (0.9425; 0.9317) | 8173 4438 3453 8032 1027 |

| MT-r3(t) | (0.9632; 0.9282) | 3759 4831 8173 9052 4438 |

| MT-r4(t) | (0.9548; 0.9385) | 3453 3759 3685 6734 5940 |

| MT-r5(t) | (0.9732; 0.9310) | 3759 8173 3624 3453 6734 |

| MT-r6(t) | (0.9640; 0.9302) | 3759 3453 6734 9329 5467 |

| MT-r7(t) | (0.9595; 0.9456) | 8674 9296 5786 8032 3584 |

| MT-r8(t) | (0.9550; 0.9198) | 9329 3759 8674 8713 3685 |

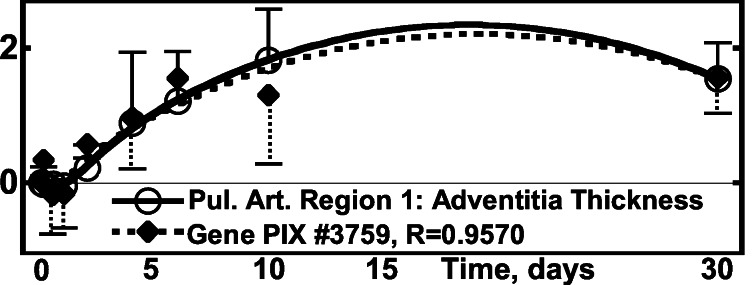

| x5(t)-Adventitia thickness of pulmonary arteries (0–30 d) | ||

| AT-r1(t) | (0.9691; 0.9391) | 3685 3759 1354 5591 4438 |

| AT-r2(t) | (0.9669; 0.9268) | 3759 3685 1354 4438 3624 |

| AT-r3(t) | (0.9524; 0.9129) | 3759 3685 1354 9285 8986 |

| AT-r4(t) | (0.9652; 0.9312) | 3759 3685 1354 5591 8713 |

| AT-r5(t) | (0.9704; 0.9169) | 3759 3624 8986 3685 9329 |

| AT-r6(t) | (0.9703; 0.9161) | 3759 3624 3685 1354 4438 |

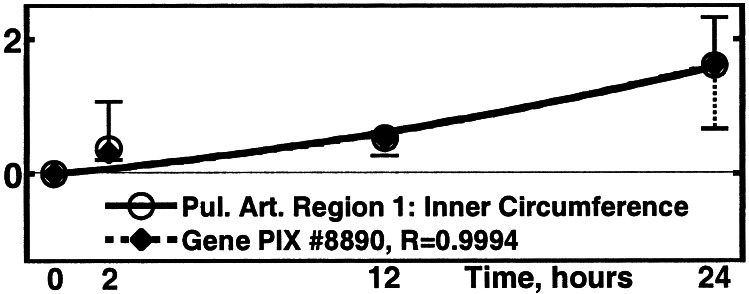

| x6(t)-Inner circumferential length of pulmonary arteries (0–24 h) | ||

| Li-r1(t) | (0.9995; 0.9989) | 662 8890 5121 6534 9145 |

| Li-r2(t) | (0.9999; 0.9994) | 8108 1972 443 4149 5695 |

| Li-r3(t) | (0.9999; 0.9994) | 5157 6269 5316 2643 8958 |

| Li-r4(t) | (0.9998; 0.9992) | 4792 8595 7585 2234 3795 |

| Li-r5(t) | (0.9998; 0.9988) | 7900 8561 3130 3283 4467 |

| Li-r6(t) | (0.99996; 0.9993) | 4145 9031 3363 4495 5615 |

| Li-r7(t) | (0.99952; 0.99922) | 4105 8567 6634 4341 718 |

| Li-r8(t) | (0.99993; 0.99978) | 2072 1967 1729 3829 6865 |

| x7(t)-Outer circumferential length of pulmonary arteries (0–24 h) | ||

| Lo-r1(t) | (0.9999; 0.9995) | 1628 8037 5688 2606 1511 |

| Lo-r2(t) | (0.9996; 0.9980) | 755 539 8830 8856 5720 |

| Lo-r3(t) | (0.9992; 0.9983) | 2668 6199 8145 4282 3075 |

| Lo-r4(t) | (0.9989; 0.9969) | 8590 9196 3178 213 1595 |

| Lo-r5(t) | (0.99995; 0.9994) | 4661 3903 5187 737 4176 |

| Lo-r6(t) | (0.9997; 0.9993) | 2426 1380 2331 2849 7175 |

| Lo-r7(t) | (0.99998; 0.9997) | 4325 7928 7133 5538 8837 |

| Lo-r8(t) | (0.99998; 0.9997) | 5309 3555 6217 1585 6545 |

| x8(t)-Young's moduli of pulmonary arteries (0–24 h) | ||

| Yθθ(t) | (0.9998; 0.9992) | 44 2442 7799 7467 3900 |

| Yzz(t) | (0.9998; 0.9989) | 4796 4563 3229 3954 6252 |

| Yθz(t) | (0.9999; 0.9998) | 3999 6187 4670 3247 778 |

Table 2.

Top 5 pulmonary artery genes of −R[xi(t)yj(t)]

| Physiol. entity | Range of correlation coefficient | Identification PIX no. of the 5 top genes |

|---|---|---|

| x1(t)-kth mean of the blood pressure Mk (0–24 h) | ||

| M10BP(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9991) | 8100 5184 1097 8083 1231 |

| M14BP(t) | (−0.9997; −0.9993) | 1097 5184 8100 2766 4137 |

| M16BP(t) | (−0.9998; −0.9993) | 7112 7948 8039 3911 4350 |

| x1(t)-kth mean of energy of the oscillations E6(0–24 h) | ||

| M9of E6(t) | (−0.9997; −0.9991) | 2046 195 8062 5967 7634 |

| M13of E6(t) | (−0.99995; −0.9993) | 2597 7865 5333 6601 8794 |

| x3(t)-Opening angle of pulmonary arteries (0–30 d) | ||

| OA-r1(t) | (−0.8960; −0.8367) | 125 3350 3148 7905 5187 |

| OA-r2(t) | (−0.9156; −0.8092) | 3350 125 7753 3148 1515 |

| OA-r3(t) | (−0.8870; −0.8502) | 5787 1354 7753 3624 1285 |

| OA-r4(t) | (−0.8745; −0.8362) | 5787 1285 1138 7753 1354 |

| OA-r5(t) | (−0.8347; −0.7907) | 319 4436 3350 5787 5631 |

| OA-r6(t) | (−0.9278; −0.8809) | 3772 3165 7205 3655 7904 |

| OA-r7(t) | (−0.9457; −0.9365) | 2533 3772 3165 7704 7904 |

| OA-r8(t) | (−0.9899; −0.9679) | 1647 7704 2886 9542 6624 |

| x4(t)-Media thickness of pulmonary arteries (0–30 d) | ||

| MT-r1(t) | (−0.9525; −0.9365) | 5554 5446 4514 5341 5320 |

| MT-r2(t) | (−0.9577; −0.9476) | 5320 5526 5979 5159 3707 |

| MT-r3(t) | (−0.9402; −0.9296) | 7422 1342 5320 5810 5979 |

| MT-r4(t) | (−0.9589; −0.9471) | 5526 5159 5554 7847 6635 |

| MT-r5(t) | (−0.9386; −0.9220) | 7422 5526 1342 5159 2324 |

| MT-r6(t) | (−0.9461; −0.9300) | 4924 7847 1342 5526 5159 |

| MT-r7(t) | (−0.9761; −0.9654) | 5159 8545 5341 6968 6635 |

| MT-r8(t) | (−0.9621; −0.9272) | 1342 5554 5159 5810 5526 |

| x5(t)-Adventitia thickness of pulmonary arteries (0–30 d) | ||

| AT-r1(t) | (−0.9252; −0.9001) | 8408 5967 2514 5810 6706 |

| AT-r2(t) | (−0.9304; −0.8950) | 5967 2514 8408 1342 5979 |

| AT-r3(t) | (−0.9312; −0.8900) | 5967 2514 4489 8408 5979 |

| AT-r4(t) | (−0.9309; −0.9115) | 5967 5554 8408 5810 2514 |

| AT-r5(t) | (−0.9185; −0.8894) | 1342 5967 6564 5810 5979 |

| AT-r6(t) | (−0.9197; −0.9077) | 1342 8408 2514 5967 6564 |

| x6(t)-Inner circumferential length of pulmonary arteries (0–24 h) | ||

| Li-r1(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9985) | 1659 8428 7556 1830 3412 |

| Li-r2(t) | (−0.9997; −0.9995) | 888 3592 7267 612 5708 |

| Li-r3(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9988) | 4498 827 4534 3790 3270 |

| Li-r4(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9995) | 4860 6524 1399 7457 3518 |

| Li-r5(t) | (−0.9993; −0.9982) | 523 1177 8462 8224 9028 |

| Li-r6(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9992) | 1438 1638 5092 3177 4152 |

| Li-r7(t) | (−0.999997; −0.999978) | 8120 101 5643 5596 2952 |

| Li-r8(t) | (−0.9982; −0.9978) | 8398 1412 356 2742 244 |

| x7(t)-Outer circumferential length of pulmonary arteries (0–24 h) | ||

| Lo-r1(t) | (−0.99995; −0.99908) | 9062 2278 8403 9018 8665 |

| Lo-r2(t) | (−0.99972; −0.99803) | 1196 6613 5244 6063 3914 |

| Lo-r3(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9973) | 6987 8814 5936 7916 529 |

| Lo-r4(t) | (−0.9997; −0.9980) | 4422 4823 1970 7929 7572 |

| Lo-r5(t) | (−0.9998; −0.9996) | 2438 9155 9473 5704 574 |

| Lo-r6(t) | (−0.99998; −0.9997) | 6197 7230 4511 6167 8422 |

| Lo-r7(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9994) | 3032 9554 1251 7845 754 |

| Lo-r8(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9980) | 9512 4076 2470 244 5282 |

| x8(t)-Young's moduli of pulmonary arteries (0–24 h) | ||

| Yθθ(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9988) | 2344 5172 6740 9495 9301 |

| Yzz(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9995) | 4434 7927 9445 3536 3693 |

| Yθz(t) | (−0.9999; −0.9996) | 7095 8228 2171 2605 1048 |

Results

(i) Positive and Negative Correlation Coefficients.

As defined in the introduction, the correlation coefficients R(x, y) can be positive or negative. A physiological function may be caused by an increase of a gene activity or by a decrease. It is interesting to know the ± sign. Hence, in listing the genes according to the values of the correlation coefficients, we tabulate the genes for positive R separately from those having negative R. This is done in Tables 1–4.

Table 4.

Top pulmonary venous genes correlating with pulmonary arterial function xi(t)

| x1(t)-kth mean of blood pressure, (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| M10BP(t) | (0.9999), 4745 | (−0.9999), 2249 |

| M14BP(t) | (0.9999), 3301 | (−0.9999), 8113 |

| x1(t)-kth mean of energy of oscillation, (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| M9of E6(t) | (0.9999), 7724 | (−0.9994), 802 |

| M13of E6(t) | (0.9998), 3165 | (−0.9998), 9488 |

| x3(t)-Opening angle of pulmonary artery, (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| Artery region 1 | (0.9525), 4754 | (−0.9167), 9158 |

| Artery region 4 | (0.9263), 870 | (−0.9272), 9156 |

| Artery region 8 | (0.9496), 369 | (−0.9675), 2021 |

| x4(t)-Media thickness of pulmonary artery, (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| Artery region 1 | (0.9792), 7360 | (−0.9646), 27 |

| Artery region 4 | (0.9676), 4082 | (−0.9664), 27 |

| Artery region 8 | (0.9735), 8715 | (−0.9715), 27 |

| x5(t)-Adventitia thickness of pulmonary artery, (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| Artery region 1 | (0.9488), 8339 | (−0.9522), 870 |

| Artery region 4 | (0.9440), 8715 | (−0.9664), 1648 |

| Artery region 6 | (0.9502), 3073 | (−0.9728), 1648 |

| x6(t)-Inner circ. length of pulmonary artery, (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| Artery region 1 | (0.9999), 4052 | (−0.9990), 6612 |

| Artery region 4 | (0.9999), 977 | (−0.9999), 7594 |

| Artery region 8 | (0.9998), 7203 | (−0.9999), 6146 |

| x7(t)-Outer circ. length of pulmonary artery, (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| Artery region 1 | (0.9999), 3655 | (−0.9999), 7282 |

| Artery region 4 | (0.9992), 6567 | (−0.9996), 1968 |

| Artery region 8 | (0.9999), 9317 | (−0.9997), 7496 |

corr. coef., correlation coefficient.

(ii) The Distribution of the Genes Lined Up in a Column According to the Correlation Coefficients with Respect to a Physiological Function.

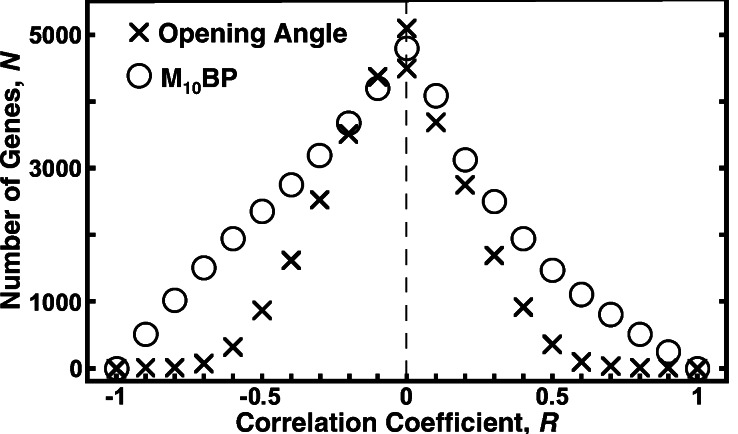

The gene having the largest correlation coefficient is called the top gene, the others are called no. 2, no. 3, etc. The names of these genes and their identification numbers (PIX no.) are listed in the software GENEPIX PRO 3.0 (Axon Instruments). The distribution of the number of genes as function of the correlation coefficient is illustrated in Fig. 2 for two cases: (i) the opening angle and (ii) the mean pulmonary blood pressure, both following a step decrease of oxygen concentration in the breathing gas. The abscissa is the correlation coefficient R. The ordinate is N, the number of genes in the interval (R, 1) for positive R or in (−1, R) for negative R.

Figure 2.

The distribution of the genes as a function of the correlation coefficient R. The ordinate N is the number of genes in the interval (R, 1) for positive R or in (−1, R) for negative R. BP, blood pressure.

(iii) Correlation of Activity of Pulmonary Arterial Genes with the Changes of Pulmonary Arterial Blood Pressure.

We induced a rapid rise in pulmonary arterial blood pressure by a step decrease of the oxygen concentration in the breathing gas. This is the well-known high altitude disease (7–10). The details of the control of gene expression by this process, which are of great interest, are unknown. Fig. 1 shows a typical pulmonary blood pressure trace. We analyzed the features of the blood pressure by the intrinsic mode functions outlined in Eqs. 4–7 (ref. 1–3). We fitted these features with Eq. 3 and fitted the gene activities with the same Eq. 3. The plots of the fitted curves of the second genes are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The corresponding numerical listing of the top five genes that correlate best with the blood pressure data is presented in Table 1 for positive correlation and Table 2 for negative correlation. The M10BP(t) represents the order 10 of the mean blood pressure as a function of time. The M9 of E6(t) represents the order 9 of the energy of oscillation E of order 6. See Materials and Methods for definitions of these terms. The parentheses indicate the range of the correlation coefficients for the top five genes whose gene identification numbers (PIX no.) are listed.

From this study we learn that the activities of many genes correlated extremely well with the time courses of the change of blood pressure, and that the genes which match the mean pressure best are not the same genes that best match the energy of oscillations about the mean.

(iv) Correlation of the Activity of Pulmonary Arterial Genes with the Oxygen Concentration in Breathing Gas.

When pO2 level is a step function, the top five genes whose activity matches the hypoxic levels are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

(v) Correlation of the Activity of Pulmonary Arterial Genes with Pulmonary Arterial Opening Angle.

The opening angle defines the zero-stress state. Its change indicates tissue remodeling. The distribution of the number of genes as a function of the correlation coefficient R is shown in Fig. 2. The top pulmonary arterial genes that correlate with the opening angle changes are listed in Tables 1 and 2; the correlation is illustrated in Fig. 5. The pulmonary arteries are labeled by Region numbers. Region 1 is the pulmonary arterial trunk. Region 1 bifurcates into two smaller Region 2 vessels, and so on. Eight consecutive regions of the main pulmonary artery were studied. The relationship between region numbers and generation numbers is given in W.H. et al. (5).

Figure 5.

Activity of the gene PIX no. 7122 (pleckstrin 2 homolog

gene) vs. the opening angle of pulmonary arterial trunk.

○, Δ(open

angle)⋅[(1/N)∑ (Δopen

angle)2]−1/2, one SEM flag up;

⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(Δopen

angle)2]−1/2, one SEM flag up;

⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(vi) Correlation of the Activity of Pulmonary Arterial Genes with Arterial Intima-Media Layer Thickness.

The endothelium and intima of the pulmonary artery have a thickness of only 2–5 μm, hence measurements were made on the combined thickness of intima-media layer. The media layer is composed of smooth muscle cells and elastin. The thickness change is a measure of tissue remodeling. Data are given in Tables 1 and 2 and illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

Activity of the gene PIX no. 8713 (inorganic

pyrophosphatase gene) vs. the media thickness of pulmonary

arterial trunk. ○,

Δ(Hmed)⋅[(1/N)∑ (ΔHmed)2]−1/2,

one SEM flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(ΔHmed)2]−1/2,

one SEM flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(vii) Correlation of the Activity of the Pulmonary Arterial Genes with Arterial Adventitia Layer Thickness.

The adventitia is the outer layer of the artery. It is composed of collagen, fibroblasts, and ground substances. The remodeling of this layer after a step hypoxia is shown in Fig. 7 and Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 7.

Activity of the gene PIX no. 3759 (osteoblast-specific factor 2,

fasciclin I-like gene) vs. the thickness of adventitia in

pulmonary arterial trunk. ○,

Δ(Hadv)⋅[(1/N)∑ (ΔHadv)2]−1/2,

one SEM flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(ΔHadv)2]−1/2,

one SEM flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(viii) Correlation of the Activity of Pulmonary Arterial Genes with the Circumferential Lengths of the Inner and Outer Walls of the Pulmonary Arteries at the Zero-Stress State.

We measured the remodeling of the circumferential length of the inner and outer arterial walls at the zero-stress state. The results are summarized in Fig. 8 and Tables 1 and 2. These, and the opening angle, are fundamental characteristics of tissue remodeling.

Figure 8.

Activity of the gene PIX no. 8890 (GTP-binding protein 2

gene) vs. the inner circumference of the pulmonary arterial

trunk at zero-stress state. ○, Δ(Inner

Circumference)⋅[(1/N)∑ (ΔInner

Circumference)2]−1/2, one SEM

flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(ΔInner

Circumference)2]−1/2, one SEM

flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

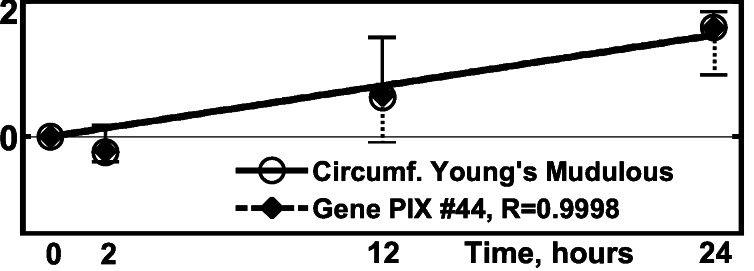

(ix) Correlation of the Activity of Pulmonary Arterial Genes with the Young's Modulus of Elasticity of the Arteries.

Elasticity measurements were done on the Region 2 pulmonary artery. The results are presented in ref. 11. The matching with gene activities is shown in Fig. 9 and Tables 1 and 2. The vessel wall is treated as a circular cylindrical shell with anisotropic elasticity. Under a transmural pressure, the radial stress is much smaller than the circumferential stress and can be neglected. The circumferential and longitudinal stresses and strains are related by a biaxial relationship, which can be linearized in the neighborhood of the in vivo state. In Fung and Liu (18) it is shown that the constitutive equation requires three elastic moduli. These are the Young's modulus in the circumferential direction, Young's modulus in the longitudinal direction, and a Cross modulus between the longitudinal and circumferential directions. These three moduli were measured on specimens with samples collected at specific instants of time after the initiation of step hypoxic breathing and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Data on all three moduli are given in ref. 11. Fig. 9 illustrates the matching of the time course of the Young's modulus in the circumferential direction with gene activity.

Figure 9.

Activity of the gene PIX no. 44 (dynein, cytoplasmic light

polypeptide gene) vs. the change of Young's modulus of

elasticity of the pulmonary artery in region 2,

Yθθ, relating circumferential

stress and strain. ○,

Δ(Yθθ)⋅

[(1/N)∑ (ΔYθθ)2]−1/2,

one SEM flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(ΔYθθ)2]−1/2,

one SEM flag up; ⧫, gene activity, one SEM flag down.

(x) Correlation of Various Rates and Integrals of Pulmonary Arterial Gene Activities and Physiological Parameters.

It is reasonable to expect that the remodeling of the thickness of the

media and adventitia layers of the blood vessel and the opening angle

at zero-stress state, which involves the addition or subtraction of

materials, be the result of cumulative integrated effect of gene

activities. Hence we examined the correlation of the integral of the

gene activity with physiological parameters. The experimental data were

fitted with Eq. 3, integrated from 0 to t, then

substituting yj in Eq. 1 by

∫ yj(t)dt and computing the

correlation over a total period T. The results are

illustrated in Table 3. The correlation between the integral of gene

activities and the opening angle lies in the range of 0.5–0.8 at best.

On the other hand, the integrated activity of some arterial genes shows

excellent correlation with the thicknesses of the arterial media and

adventitia layers; with positive correlation coefficients well above

0.98, but the genes with the best correlation for the integral test

were not the same as those for the straight contest listed in Tables 1

and 2. There was no good negative correlation between the integrated

gene activity and wall thickness.

yj(t)dt and computing the

correlation over a total period T. The results are

illustrated in Table 3. The correlation between the integral of gene

activities and the opening angle lies in the range of 0.5–0.8 at best.

On the other hand, the integrated activity of some arterial genes shows

excellent correlation with the thicknesses of the arterial media and

adventitia layers; with positive correlation coefficients well above

0.98, but the genes with the best correlation for the integral test

were not the same as those for the straight contest listed in Tables 1

and 2. There was no good negative correlation between the integrated

gene activity and wall thickness.

Table 3.

Best correlation of pulmonary artery function

xi(t) with the cumulative

integrated gene activity = ∫ (pulmonary artery

gene activity(t))dt

(pulmonary artery

gene activity(t))dt

| x3(t)-Opening angle (0–30 d), (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| Artery region 1 | (0.5352), 7589 | (−0.6338), 6420 |

| Artery region 4 | (0.7102), 4988 | (−0.8008), 5330 |

| Artery region 8 | (0.7070), 8919 | (−0.5199), 4988 |

| x4(t)-Media thickness (0–30 d), (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| Artery region 1 | (0.9886), 1535 | (−0.8063), 730 |

| Artery region 4 | (0.9837), 735 | (−0.7574), 730 |

| Artery region 8 | (0.9809), 735 | (−0.7353), 730 |

| x5(t)-Adventitia thickness (0–30 d), (corr. coef.), gene PIX no. | ||

| Artery region 1 | (0.9967), 9365 | (−0.8485), 4988 |

| Artery region 4 | (0.9937), 410 | (−0.7941), 4988 |

| Artery region 6 | (0.9841), 735 | (−0.7819), 4988 |

corr. coef., correlation coefficient.

We tested also the correlation of the first derivatives of the gene activity with the first derivatives of the mean blood pressure. We found remarkably high values of positive and negative correlation coefficients in the ranges of (0.9970–0.9998) and (−0.9970-−0.9998), respectively. But again these genes are not the same as those with the highest coefficient of correlation when tested without differentiation (listed in Tables 1 and 2).

(xi) Correlation of the Activity of Pulmonary Venous Genes with Pulmonary Arterial Tissue Remodeling.

Thus far we have considered the association of arterial genes with arterial physiology in the pulmonary circulation. How about the relationship between the pulmonary venous genes and pulmonary arterial physiology? We collected tissue samples of pulmonary arteries and veins at the same time and studied their gene activities the same way. The results are illustrated in Table 4. It is seen that the top genes in the pulmonary veins correlate very well with the physiological variables of the pulmonary arteries, but the top venous genes are not the same as the top arterial genes.

Discussion

The choice of 9,600 gene probes from a human gene library was arbitrary and limiting, considering that the human genome contains some 35,000 genes (19, 20). Other than the genes in pulmonary veins, we studied only genes and tissues in the pulmonary arteries. The range of questions asked was incomplete.

Most likely, other methods to quantify the “activity” of a gene will come in the future. As new methods are developed, it would be important to apply them and compare the results with the colorimetry method used in this study.

The essence of this article is to demonstrate the power of matching the dynamics (i.e., the continuous changes with respect to time) of gene activities with the dynamics of physiological functions. The correlation coefficient is a convenient index of the matching. In dealing with the physiological data that were measured at unevenly distributed instants of time, we converted the integrals in Eq. 1 to summations, so that the R(xi, yj) is

|

8 |

where the summation is over k = 1, 2, … , N, tks are the instants of time, xi(tk) and yj(tk) are the mean values of the measured data at time tk, Δtk is the interval of time associated with tk, and N is the total number of data points. Because xi(t1) and yj(t1) are zero for the changes of xi and yj from the steady state, there are two sets of N-1 nonvanishing data points xi, yj, and N-1 time intervals. If we took Δtk = tN/(N − 1) for all k from 1 to N, we obtain the results of Rij presented in this article. If we took Δtk = tk − tk−1, we obtain a set of different Rijs, which are fairly similar to the numbers presented here.

Other mathematical methods to identify correlation, and the documentation of the effects of many details in the protocol of collecting tissue specimens for gene activity measurements, especially the temperature, the bubbling with a gas mixture of 95% O2/5% CO2 during tissue collection, and the length of tissue collection time are still under investigation.

Concluding Remarks

The correlation between gene activity with physiological functions has put some order to the great army of genes in a panoramic view. We believe that the method described here is an effective way to study the relationship among genes, physiology, and biomechanics.

Future Goal.

The present article is designed to identify the genes in blood vessels that are closely associated with the mechanical stress induced by the blood pressure in an animal. To link the mechanics of the genes with the mechanics of the tissues is the ultimate goal of our research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health Grant HL 43026; the Medical Engineering Division of the National Health Research Institute (Taiwan); the National Science Council of Taiwan Grant 90-2314-B-001-007-M54 (to K.P.); and by the Univ. of California at San Diego Common Molecular Biochemistry Facility, sponsored by the Whitaker Foundation.

References

- 1.Huang W, Shen Z, Huang N E, Fung Y C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4816–4821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang W, Shen Z, Huang N E, Fung Y C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12766–12771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang W, Shen Z, Huang N E, Fung Y C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1834–1839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamayo P, Slonim D, Mesirov J, Zhu Q, Kitareewan S, Dmitrovsky E, Lander E S, Golub T R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2907–2912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang W, Sher Y P, Delgado-West D, Wu J, Peck K, Fung Y C. Ann Biomed Eng. 2001;29:535–551. doi: 10.1114/1.1380416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang W, Sher Y P, Peck K, Fung Y C. Biorheology. 2001;38:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Euler V S, Liljestrand G. Acta Physiol Scand. 1946;12:301–320. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyrick B, Reid L. Lab Invest. 1978;38:188–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward M P, West J B, Milledge J S. High Altitude Medicine and Physiology. 2nd. Ed. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.West J B. High Life: A History of High-Altitude Physiology and Medicine. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang W, Delgado-West D, Wu J, Fung Y C. Ann Biomed Eng. 2001;29:552–562. doi: 10.1114/1.1380417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fung Y C. Biomechanics: Circulation. 2nd. Ed. New York: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J J W, Wu R, Yang P C, Huang J Y, Sher Y P, Han M H, Kao W C, Lee P J, Chiu T F, Chang F, et al. Genomics. 1998;51:313–324. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eberwine J, Yeh H, Miyashiro K, Cao Y, Nair S, Finnell R, Zettel M, Coleman P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3010–3014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bobrow M N, Harris T D, Shaughnessy K J, Litt G J. J Immunol Methods. 1989;125:279–285. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bobrow M N, Shaughnessy K J, Litt G J. J Immunol Methods. 1991;137:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90399-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peck K, Sher Y P. In: DNA Microarrays: Gene Expression Applications. Jordan B, editor. New York: Springer; 2001. pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fung Y C, Liu S Q. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2169–2173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venter J C, Adams M D, Myers E W, Li P W, Mural R J, Sutton G G, Smith H O, Yandell M, Evans C A, Holt R A, et al. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The International Human Genome Mapping Consortium. Nature (London) 2001;409:934–941. [Google Scholar]