Abstract

Brain‒computer interfaces (BCIs) exhibit significant potential for various applications, including neurofeedback training, neurological injury management, and language, sensory and motor rehabilitation. Neural interfacing electrodes are positioned between external electronic devices and the nervous system to capture complex neuronal activity data and promote the repair of damaged neural tissues. Implantable neural electrodes can record and modulate neural activities with both high spatial and high temporal resolution, offering a wide window for neuroscience research. Despite significant advancements over the years, conventional neural electrode interfaces remain insufficient for fully achieving these objectives, particularly in the context of long-term implantation. The primary limitation stems from the poor biocompatibility and mechanical mismatch between the interfacing electrodes and neural tissues, which induce a local immune response and scar tissue formation, thus decreasing the performance and useful lifespan. Therefore, neural interfaces should ideally exhibit appropriate stiffness and minimal foreign body reactions to mitigate neuroinflammation and enhance recording quality. This review provides an exhaustive analysis of the current understanding of the critical failure modes that may impact the performance of implantable neural electrodes. Additionally, this study provides a comprehensive overview of the current research on coating materials and design strategies for implanted neural interfaces and discusses the primary challenges currently facing long-term implantation of neural electrodes. Finally, we present our perspective and propose possible future research directions to improve implantable neural interfaces for BCIs.

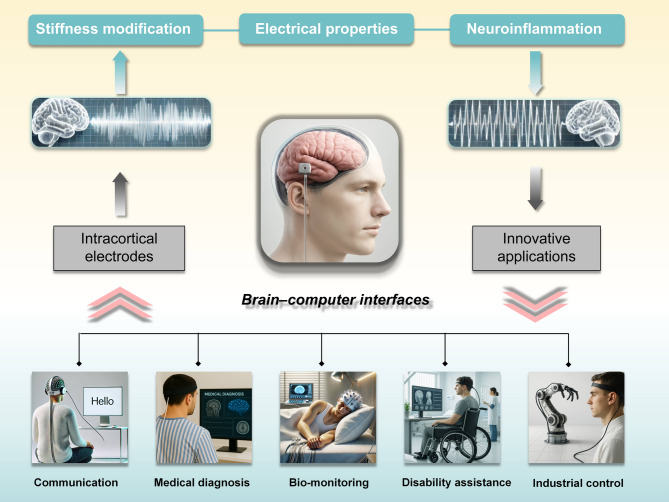

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Brain-machine interface, Neurological conditions, Neurotechnology, Intracortical electrodes, Foreign body response, Biocompatibility

Introduction

Neurological trauma caused by accidents can result in injuries to the brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nervous tissue, subsequently affecting various physical functions, including those of vital organs and the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal systems [1]. Furthermore, neurological illness can affect anyone, regardless of sex, age, education, or socioeconomic status, with an estimated tens of millions of cases occurring annually worldwide [2–4]. The high incidence of these conditions has led to the expenditure of billions of dollars each year on treatments for neurological diseases. Neural signal acquisition, signal analysis and artificial output are crucial for early neurological disease diagnosis and treatment. Research on brain‒computer interfaces (BCIs) has yielded significant advancements in the development of cortical neuroprostheses, and their potential to restore motor and sensory functions in individuals with a neurological disease has been demonstrated [5–8]. Neurostimulation therapies targeting the cochlea, vagal nerve, deep brain, and spinal cord have profoundly enhanced the quality of life of hundreds of thousands of individuals worldwide [9]. Investigations into BCIs for managing spinal cord injuries have produced promising outcomes in the restoration of both gross and fine motor functions in patients with paralysis. For instance, Hochberg et al. [10]. conducted a clinical study in which two quadriplegic patients successfully controlled and executed three-dimensional movements, such as grasping and stretching, using a robotic arm interfaced with BCIs. One participant successfully utilized a robotic arm to drink coffee from a bottle. With continued research into the impact of nonstationarity on the accuracy of BCI-coordinated movements [11], this modality holds potential as a viable method for restoring a meaningful quality of life to individuals with neurological injury or disease.

Recent advancements in electrically conductive devices have spurred the development of bioelectronic systems, including BCIs. Neural electrodes play a crucial role in BCIs, as they act as a communication bridge between external intelligent devices and the brain. They facilitate real-time recording and digitization of brain signals by directly transmitting them to a computer for in-depth analysis and visualization [12]. Brain signal recording methods are typically categorized into three major approaches: (I) detecting and registering the electrical activity of the brain using non-implantable electrodes attached to the scalp (electroencephalography, EEG); (II) recording signals from the surface of the cerebral cortex via electrodes (electrocorticography, ECoG); and (III) performing intracranial electroencephalography using implantable depth electrodes within brain tissue (deep brain stimulation, DBS) [2, 13, 14]. Broadly, BCIs can be categorized as non‐implantable or implantable according to whether they are implanted into the tissue of the human brain. Compared with traditional non‐implantable electrodes, implantable neural electrodes can provide greater neural signal quality and have the potential to be applied in other subfields of neuroscience. Implantable neural electrodes can be precisely positioned within specific regions of the cerebral cortex, thereby ensuring high-precision and stable electroencephalogram signal transmission [15, 16]. Additionally, implantable BCIs possess the ability to not only output neural signals from within the brain to external devices and interpret them but also convert external electrical signals and input them to reversely stimulate neurons, thereby restoring specific neural activities [17–19]. As the “bridge” of BCIs, implantable electrodes are a fundamental component of these devices. However, neural electrodes face challenges due to the biological incompatibility and mechanical mismatch between soft neural tissues and neuroelectrode interface materials, which can lead to acute penetrating injury, chronic inflammation, increased impedance from astrocytic scars and microglial proliferation [20–22]. For optimal BCIs application, the ideal material must meet several key requirements: (I) excellent electrical properties to enhance signal acquisition; (II) good physical and mechanical properties to prevent direct damage to brain tissue; and (III) high biocompatibility to minimize immunological and inflammatory responses.

To date, various strategies have been employed to address these challenges. However, some existing studies still have limitations, particularly concerning material properties and the technical methods of device fabrication. Therefore, more research on and optimization of the neural electrode‒tissue interface is urgently needed. For this reason, researchers are now putting increasingly significant efforts into designing new types of low-stiffness and good-biocompatibility implantable electrodes while ensuring excellent electrical properties for efficient transduction of electrical signals to the brain. This review summarizes advancements in implantable electrodes used for therapies, focusing on new electrode‒tissue interface materials and post-implantation pathophysiological responses. We start with a brief outline of the typical materials used in bioelectronic interfaces and fundamental mechanisms of tissue‒electrode interactions to provide a rational theoretical foundation. Next, we explore relatively soft materials, conducting polymers and immunosuppressive regimens, along with their applications in neural interfaces. Finally, emerging trends in and future perspectives of the BCIs field are discussed.

Overview of neural implants and their biocompatibility

The development of electrode neural interfacing systems has spanned almost one full century, encompassing intracranial/extracranial electrode recording, DBS, and direct intracranial administration (Fig. 1). Technology to record signals from the human brain has been available since the 1930s, starting with non-implantable electroencephalography and transcranial ECoG [23, 24]. This was soon followed by the creation of penetrating medium-depth microwire electrode arrays [25]. Among the various electrophysiological signals, electroencephalography signals obtained non‐implantable from the scalp are the most accessible [14]. However, their utility is limited because of the inability to provide localized information pertaining to specific brain regions owing to interference from numerous local field potentials. Furthermore, electroencephalography signals are susceptible to noise from both external and internal sources, which results in a suboptimal signal-to-noise ratio. Conversely, ECoG signals do not incorporate noise from sources situated between the scalp and skull because brain cortical regions are directly measured. Nevertheless, ECoG primarily captures the electrical signals of superficial brain regions. Consequently, similar to electroencephalography, it can be utilized to discern sensory information and basic cognitive information, but it lacks the capacity to acquire signals with the high-quality resolution found for signals emanating from individual neurons [14, 15].

Fig. 1.

The general paradigm of brain‒computer interfaces (BCIs) involve the collection of neural activity by sensors, followed by processing of these signals by decoders to control external devices. These devices, in turn, provide feedback to the user. Examples of neural recording devices for brain‒machine interface devices include non-implantable electroencephalography (EEG), which allows recording with nonpenetrating leads, and implantable electrocorticography (ECoG), which enables transcranial recording via leads positioned above or below the dura mater. A deep brain stimulator (DBS) delivers electrical pulses to the brain via an implanted neurostimulator. Multielectrode arrays, which comprise numerous penetrating electrodes, facilitate recording of neural activity across an extensive cortical area. Miniaturized neural drug delivery systems (MiNDS) enable precise administration of therapeutics to deep brain regions

For more in-depth and extensive research on neuroscience, psychological sciences and sports science, collecting signals from specific deep regions of the brain with high spatial and temporal resolution is crucial. This measurement typically targets subcortical areas, necessitating implantable electrodes into the deep brain [26, 27]. The initial experiments involving microwire arrays in cell cultures were conducted in 1972 and utilized myocytes derived from embryonic chicks [28]. Over the subsequent two decades, significant advancements in novel materials and manufacturing techniques facilitated cost reductions and decreased barriers to entry, thereby enabling more research laboratories to engage in the field of neuroimplantables. In the early 1990s, micromachined silicon-based shanks, consisting of arrays of rigid-type electrodes, emerged. Noteworthy developments in this domain include the Michigan-style probe, pioneered at the University of Michigan in 1971, and the Utah electrode, developed at the University of Utah in 1992 [29, 30]. These devices have been successfully applied to record the neural activities in the cortices of monkeys and cats in the form of electrical signals [31, 32]. With technological advancements, conventional electrodes have been integrated with communication circuits and transparent antennas to link with wireless smart systems [33, 34].

With the recent surge in artificial intelligence advancements, neural decoding offers valuable insights for designing innovative BCIs algorithms. For example, earlier studies utilized retinal neural spike data collected across multiple trials with visual stimuli to assess image quality, thus establishing a comprehensive framework for neural decoding [35]. Artificial intelligence not only enhances our understanding of neural coding in various contexts but also serves as a foundation for developing next-generation decoding algorithms for neuroprostheses and other BCIs devices. These advancements hold great promise for improving patient outcomes and streamlining healthcare processes [36]. Recent studies underscore the transformative role of AI in this domain, notably improving the speed and precision of neural signal interpretation and device responsiveness. By integrating real-time detection of neurological symptoms (e.g., epileptic seizures) with closed-loop neuromodulation, such devices can deliver targeted, adaptive stimulation to prevent adverse neurological events [37, 38]. Furthermore, AI techniques have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in decoding complex neural activity patterns, enabling more precise control of prosthetic limbs and supporting innovative communication methods for individuals with severe motor or speech impairments [39].

Although considerable success in neural interface applications has been achieved with intracortical microelectrodes, numerous studies have reported inconsistencies in chronic cortical recordings across various species and electrode types [40]. Research has suggested that mechanical damage and corrosion, occurring during or after insertion, can result in microelectrode failure. Previous studies have demonstrated that bare tungsten and gold-plated tungsten wires are prone to corrosion in phosphate-buffered saline, even under nonstimulating conditions. Patrick and colleagues reached the same conclusion that the presence of oxidative species exacerbates tungsten corrosion [41]. Additionally, since neural tissue has a soft consistency, with a Young’s modulus ranging from 1 to 10 kPa, interfacing with traditional rigid materials such as silicon (approximately 102 GPa) and platinum (approximately 102 MPa) creates a significant mechanical mismatch and foreign body reactions [42]. These factors can adversely affect the surrounding brain tissue, such as by inducing micromotion-related damage and tissue scar formation around chronic implants. The selection of materials is critical in determining the response of brain tissue to implanted devices. Rigid electrodes present notable advantages in the advancement of high-density neural interfaces. The utilization of mechanically robust materials, such as carbon fibers, has facilitated the fabrication of microelectrode arrays characterized by exceptionally high spatial resolution. For example, carbon fiber electrodes with diameters as small as 7 μm have demonstrated adequate stiffness for self-supported insertion in dense arrays, with inter-electrode spacing ranging from 50 to 100 μm [43]. Significant progress has also been achieved in the microfabrication of high-density, silicon-based neural probes. These probes incorporate application-specific integrated circuits for on-site signal amplification, filtering, and multiplexing, thereby enabling recordings from up to 1024 channels [44, 45]. The probes offer clear advantages for depth-resolved neural recordings due to their densely packed longitudinal contact arrays. Nevertheless, their relatively large cross-sectional dimensions and mechanical rigidity frequently result in tissue damage, which constrains their suitability for ultra-dense implantation and long-term biocompatibility [46].

Despite the emergence of novel neural interface systems, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval is rarely covered in most academic studies of implantable neural electrodes. The regulatory framework of the FDA is structured around a three-class system, wherein Class III medical devices are associated with the highest risk to consumers, whereas Class I devices are deemed the safest [47]. Most Class I devices, characterized as low risk, are subject only to general controls and are typically exempt from the requirement of submitting an application to the FDA. In contrast, most Class II devices, which present a moderate risk, necessitate premarket notification, and the majority of Class III devices, associated with high risk, require premarket approval. The FDA has established specific guidelines pertaining to the biocompatibility of materials utilized in medical devices [48, 49]. The FDA considers several key factors when deciding whether to approve implantable neural electrodes for clinical trials and, subsequently, for commercial use. The factors include the (I) electrode material, (II) outer dimensions, (III) functional electrode layer, and (IV) mode of implantation [50–52]. Neural interfaces with empirically validated materials, smaller overall dimensions, optimal functional coatings, and simpler modes of implantation are better positioned to advance to the clinical phase. Exploration of the coatings for neural electrodes is a valuable research direction. In the present study, various novel coatings are evaluated for their ability to mitigate the foreign body response, with a particular focus on reducing glial scarring at neural interfacing sites in vivo.

Reactive tissue responses to neural implants

Specificity of brain tissue and cell constructs

The blood‒brain barrier (BBB) restricts the presence of many types of cells, including immune cells, which are typically prevalent throughout the human body. Consequently, the brain has evolved a unique repertoire of cells to fulfil its functional requirements. The brain consists of two major cell types: neurons and glial cells (astrocytes, radial glia, oligodendroglia, and microglia). Both neurons and glial cells originate from precursor cells within the neuroectodermal germ layer during embryonic development, which enables their persistence in the brain after the formation of the BBB [53]. Furthermore, neuroglial cells play crucial roles in maintaining neuronal homeostasis, contributing to synaptic plasticity, and facilitating cellular repair. Within brain tissue, glial cells, including microglia and astrocytes, exhibit migratory behaviour towards foreign bodies as part of a physiological immune response. Glial cells, including microglia and astrocytes, are considered major mediators that act during cerebral inflammation.

Astrocytes, a major type of glial cell in the central nervous system (CNS), are indispensable for coordinating neural circuit assembly and maintenance [54, 55]. Astrocytes, marked by extensive branching and radiating projections, display diverse morphological and functional characteristics. Their end-feet are rich in mitochondria, reflecting their significant metabolic demand. These complex cells interact with the neuropil, playing crucial roles in the formation, remodelling, and elimination of synapses. Their projections regulate the synaptic structure and function, homeostatic maintenance, synaptic plasticity and neurotransmitter regulation. Additionally, the end-feet of astrocytes envelop blood vessels, thereby modulating blood flow and maintaining the integrity of the BBB. Owing to their high resistance to inflammatory factors and pressure stimuli, astrocytes act as protectors of neurons. Additionally, they secrete growth factors vital for neuroprotection, neuronal growth, and repair.

In response to CNS damage, astrocytes undergo morphological changes and develop hyperactivity, known as astrogliosis [43, 56, 57]. This process consists of three stages: (I) stimulation of astrocyte proliferation, (II) formation of glial scars, and (III) immune cell recruitment. Recent basic studies have identified two different types of reactive astrocytes: (I) neurotoxic astrocytes, which secrete proinflammatory factors, and (II) neuroprotective astrocytes, which promote neuronal growth and survival by secreting neurotrophic factors. Neurotoxic astrocytes interfere with calcium signalling in astrocytes, causing an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, thus leading to neuroinflammation [58]. Prolonged pathological conditions can lead to chronic activation of microglia, rendering them nonfunctional. Norden et al.. reported that ageing astrocytes are not sensitive to anti-inflammatory factors, which disrupts the feedback loop in which astrocytes secrete TGF-beta, in turn decreasing microglial activation [59, 60]. Astrocytes significantly interact with other types of glial cells. Both microglia and astroglia function as phagocytes and modulate inflammation, exchanging paracrine signals for communication and coordination. Similarly, oligodendrocytes communicate with astroglia through paracrine signals as well as direct intercellular contact.

Microglia are brain-resident macrophages essential for immune responses, neural development, and cognitive functions [61]. During early embryogenesis, microglial progenitors migrate from the yolk sac into the brain during embryonic development. After injury to the brain, activated microglia phagocytose axon and myelin debris, undergo necroptosis to eliminate proinflammatory cells, and are repopulated with anti-inflammatory microglia to promote remyelination by oligodendrocytes. As professional phagocytes, microglia engulf pathogens, apoptotic cells and misfolded proteins that often follow rapid proinflammatory responses [62, 63]. This process maintains brain homeostasis by preventing autoimmune neuroinflammation and minimizing unnecessary damage. Oligodendrocytes are another important component of glial cells in the CNS, distinguished by their remarkable capacity to ensheathe neuronal axons with their cytoplasmic membranes, thereby forming myelin [64]. These myelin sheaths are crucial for conduction and coordination of action potentials, enabling rapid, efficient, and finely tuned signal transmission along axons. Additionally, myelin sheaths prevent signal loss, protect axons from damage, and provide trophic and metabolic support [65, 66].

Brain tissue injury and foreign body response

Implantable neural electrode devices designed for chronic neural recording hold significant potential for restoring functional control to individuals with paralysis and limb loss through brain‒machine interfaces. However, these probes exhibit high failure rates, in part owing to biological responses that result in the formation of inflammatory scars and subsequent neuronal cell death [21, 42]. The foreign body response constitutes a neuroinflammatory reaction elicited by the disruption of healthy tissue and the persistent presence of a foreign object within the brain, including intracortical microelectrode and deep brain stimulating electrodes [67, 68]. To date, the mechanisms underlying the foreign body response have not been fully elucidated. Consequently, the correlations between the foreign body response and the failure mechanisms of chronically implanted electrodes are the subject of active investigation. The introduction of such interfaces into the CNS initiates multiphase tissue remodelling, culminating in BBB disruption, glial scar formation, and the persistent presence of proinflammatory factors and anti-inflammatory factors (Fig. 2). These factors collectively create a deleterious microenvironment for the implantation region of neural electrodes. This adverse microenvironment poses significant challenges to both neuronal functions and the performance of implanted devices. With respect to this, a recent study of the inflammatory response to subdural electrode implantation revealed significant histopathological changes as early as one day post-implantation in over half of the subjects [69].

Fig. 2.

Foreign body response to neural interfaces: Electrode implantation induces a local proinflammatory environment and biochemical responses. Following implantation, activated microglia rapidly adhere to the electrode surface and secrete proinflammatory mediators. This initial microglial adhesion is succeeded by astrocytic encapsulation along the entire electrode shaft, resulting in the formation of a glial scar. These processes, along with localized haemorrhaging, are associated with neurodegeneration at the interface. Notably, the depicted microelectrode represents a silicon shank, but the concept applies to other microelectrode types

The insertion of electrodes is inherently traumatic, and even procedures that meticulously avoid major pial arteries and veins inevitably result in rupture of cortical capillaries. This process begins at the time of implantation, and the electrodes displace and damage the blood vessels, cells, and extracellular matrix along their path to the target site, leading to disruption of the BBB [70, 71]. This results in an influx of plasma proteins that adsorb onto the microelectrode surfaces, as well as infiltration of inflammatory cells. Therefore, damage to the BBB is also an important factor linking the foreign body response to a decrease in electrode performance during long-term implantation. In addition, the “leakiness” of the BBB allows peripheral immune cells to enter the brain parenchyma and accumulate at the lesion site, exacerbating neurotoxic effects over time. The interplay of necrotic cell debris, plasma proteins, cellular infiltration and mechanical stress induced by probe insertion culminates in upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, thereby initiating a cascade of reactive tissue responses [72, 73]. Additionally, neuroinflammation feeds back to an increase in the BBB permeability, facilitating infiltration of blood components such as fibrinogen, which in turn further aggravates brain tissue damage [74–76]. Moreover, the chronic presence of reactive inflammatory cells, inflammatory cytokines, and other mediators at stimulation sites contributes to neuronal death and impedes the repair of healthy neural tissue.

Implantable electronic devices typically induce a prolonged inflammatory response and sustained activation of astrocytes and microglia in a proinflammatory state. Local astrocytes and microglia shift from their resting state to their phagocytic phenotypes or activated state as part of the normal response to injury [77, 78]. The initiation of this process involves protein adsorption onto the electrode surface, subsequently triggering an inflammatory tissue response and recruitment of immune cells [79]. Notably, microglia have been demonstrated to respond within 30 min post-implantation, and astrocyte activation and migration occur over the following hours [73, 80]. Reactive astrocytes engage in mutual coordination with microglia through signalling pathways involving IFN-γ and/or TNF-⍺ cytokines/chemokines [81]. In the weeks after implantation, a fibrous envelope—commonly termed the glial scar—composed of reactive astrocytes, connective tissue, and the extracellular matrix progressively develops around the device. This process ultimately results in encapsulation of the probes by the surrounding tissue, thereby physically isolating the device from the neurons [82, 83]. Under physiological conditions, this proliferation of astrocytes results in the formation of scar tissue, which prevents the spread of secondary injury and facilitates subsequent repair. The degradation of the signal primarily results from the separation and isolation of the electrode points from the target neurons, leading to a decreased signal-to-noise ratio and consequently affecting the overall efficacy of the device [84]. In addition, it should be noted that chronic implantation of neural electrodes induces glial activation and scar formation, which increases the distance between electrodes and neurons, thereby degrading the quality of high-frequency spike recordings. In contrast, local field potentials remain more stable over time due to their lower frequency and spatial integration properties.

A significant challenge arises from the physical and chemical disparities between Implantable neural electrodes and the brain. These differences hinder effective cell adhesion, leading to micromotion of the interfaces and increased strain on brain cells and tissues. Inadequate cell adhesion can cause micromotion of intraneural electrodes, thereby imposing additional strain on the brain and exacerbating damage [85]. Research has demonstrated this phenomenon, in which astrocytes, microglia, and cortical neurons were subjected to simulated micromotion-induced stretching over specified durations [86]. Over time, all cell types exhibited reduced viability due to the applied strain, with cortical neurons showing the most significant decline. The use of rigid materials such as silicon and glass in the design of intraneural electrodes increases the risk of micromotion and subsequent damage. Furthermore, the combination of strain induced by implantable neural interfaces and the foreign body response in the brain ultimately compromises the normal function of these interfaces [87]. Chronic implantation of neurosurgical equipment in the brain can exacerbate inflammation through failure of implanted devices, and brain tissue constantly undergoes micromotion, potentially initiating a positive feedback loop. Additionally, the glial scar contains growth-inhibiting factors, which further decrease the possibility of neuronal growth and spontaneous recovery in the implant regions [78, 88]. These alterations manifest as a substantial neuroinflammatory response and the formation of glial scars, which subsequently increase noise levels in electrophysiological recordings and the electrical impedance, thereby impeding tissue‒microelectrode integration [89]. Overall, glial scar formation is a characteristic feature of neural interfaces within the brain, and the extent or thickness of this scar is frequently employed as an indicator of the effectiveness of intervention effects designed to attenuate the foreign body response.

The persistent release of neurotoxic factors and the activation of the complement system by the activated microglia and astrocytes are detrimental to local neurons [62, 90, 91], contributing to adverse inflammatory sequelae and reduced neuronal density around implants (Fig. 3). Furthermore, reactive microglia facilitate the release of proinflammatory mediators and nitric oxide, leading to abnormal dilation of cerebral vessels and worsening neuronal damage [92, 93]. Enzymatic reactions of an inflammatory nature within reactive neuroimmune cells have the potential to generate elevated levels of ROS, thereby inducing oxidative stress within the surrounding tissue [94]. The persistent presence of ROS consistently compromises the biostability of implanted devices, resulting in corrosion of active electrode sites and progressive degradation of both insulating layers and device interconnects [20, 95]. The oxidative stress can further intensify neuroinflammation through a positive feedback mechanism, thereby increasing the ROS concentration [96]. This consequently leads to oxidation of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, culminating in neuronal dysfunction and eventual neuronal death [97, 98]. Reduced performance and eventual failure of BCIs systems can lead to diminished therapeutic efficacy. Consequently, optimizing the biocompatibility of electrodes to increase the longevity of implantable neural electrodes in vivo is of paramount importance.

Fig. 3.

Neuroinflammatory pathways are initiated following the implantation of electrodes due to localized vascular damage. Disruption of the vasculature results in mechanistic interactions at the interface of the implanted electrodes. Proteins derived from extravasated blood adhere to the surface of the implanted microelectrode and disseminate throughout the surrounding tissue environment. These blood-borne mediators subsequently activate inflammatory cells, leading to the release of cytotoxic soluble and proinflammatory factors. The release of inflammatory factors further aggravates the self-perpetuation of both blood‒brain barrier (BBB) disruption and sustained neuroinflammation around the implant. The release of cytotoxic soluble and proinflammatory factors can directly and indirectly induce neuronal apoptosis. Cellular debris from apoptotic neurons can also further activate microglia, exacerbating BBB instability. Consequently, the neuroinflammatory response to implantable electrodes is expected to persist for the duration of the presence of the implant within the tissue

Material strategies for improving neural interface biocompatibility and recording performance

The primary focus of research in this field has been the development of electrode materials that meet the three criteria essential for application in BCIs technology (Table 1): a material with mechanical properties similar to those of soft tissues that also possesses low immunoreactivity and excellent electrical properties. One of the methods involves electrode design to integrate softer conductive materials that more closely mimic the properties of neural tissue, thereby enhancing the neurocompatibility and extending the lifespan of the implants [99–101]. Flexible electronics fabricated from low-stiffness polymers and patterned to exhibit microscale conductive properties have the potential to decrease mechanical trauma. Nevertheless, softening of the electrode alone is insufficient to address inflammation at the device–tissue interface. Histological examination of the foreign body response to an implantable neural electrode in animal models has revealed substantial complications, such as neurodegeneration, pronounced inflammation, and fibrotic encapsulation surrounding the electrode site [57, 89, 102]. Additionally, electrical activity is the most important characteristic for neural function and activity and the primary mechanism through which neurons receive, transmit and express signals [14, 103]. Considering the above points, further studies include the development of innovative interface materials characterized by a low modulus, a low electrical impedance and high biocompatibility towards structurally and functionally stable interfaces.

Table 1.

Current surface modification technologies for neural stimulation

| Modification strategy | Type of material | Electrode/ device types | In vivo or in vitro |

Experimental model |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stiffness modification |

Extracellular matrix hydrogel |

Polypropylene mesh devices |

In vivo | Rat | [114] |

|

Extracellular matrix |

Silicon microelectrode arrays |

In vivo and in vitro |

Rat and astrocytes | [115] | |

| Polyethylene glycol hydrogels | Implant needle | In vivo | Rat | [129] | |

| Polysaccharide hydrogels | Silicon microelectrode arrays | In vivo | Rat | [130] | |

| Polyacrylamide hydrogels | Electrocorticography electrode |

In vivo and in vitro |

Mouse and neural cells | [136] | |

| Conductive properties | Gold nanoparticles | Neural microelectrode | In vitro | Astrocytes | [171] |

| Pristine graphene-based composite materials | Neural microelectrode | In vitro | Neuronal and glial cells | [181] | |

| Carbon nanotubes | Platinum electrodes | In vitro | Spiral ganglion cells | [183] | |

| Immune modulation | Dexamethasone | Intracortical neural probes | In vivo | CX3CR1 promoter mice | [199] |

| Sol − gel films | Neural electrode | In vitro | PC-12 and astrocyte cells | [73] | |

| L1 cell adhesion molecule | Long silicon probes | In vivo | Mice | [201] |

Stiffness modification for neural electrode interfaces

Brain tissues and other CNS components are shielded by sturdy tissues (dura mater and skull), making them less exposed to external mechanical stress than other parts of the body [104]. Therefore, the brain is highly susceptible to mechanical damage under external pressure, with neural axons breaking at approximately 18% strain, and it possesses a limited capacity for self-repair [105, 106]. Traditional electrode materials, such as silicon, gold, platinum, titanium nitride, iridium and many others, typically have a Young’s modulus in the range of GPa, which is significantly greater than that of neural tissues (approximately 1 kPa) (Fig. 4A). Owing to the sharp difference in the elastic moduli, brain tissue injury and lesions are caused by the severe mismatch between rigid electrodes and soft brain tissue during the implantation process [107].

Fig. 4.

Mechanical mismatch between commonly used probe materials and soft neural tissue. A A comparison of the Young’s moduli of cells/tissues with those of materials frequently employed in bioelectronic interfaces reveals significant disparities. Compared with cells and tissues, metals exhibit considerably greater stiffness; in contrast, polymers are relatively soft. B Schematic representation illustrating the mechanical compliance of biomimetic materials and elastomers (dimethylsiloxane and PDMS) in comparison to stiff inorganic materials (such as silicon, metals, and oxides)

Biomimetic tissue interfaces

At present, research on BCIs has largely focused on enhancing the biocompatibility of neural interfacing devices to address the mechanical mismatch inherent in implantable neural electrodes. Recent advances in tissue engineering have emphasized the incorporation of soft materials to develop biologically active or cell-laden living layers at the tissue–device interface, promoting seamless biointegration and enabling novel cell-mediated therapeutic strategies. As highlighted by Boufidis et al., although significant progress has been made in addressing mechanical biocompatibility, the fundamental differences in signal modality and complexity continue to pose significant challenges to effective neural communication [108]. To address these challenges and achieve seamless integration of neuroelectronic devices with host brain structures, design strategies and material selection are increasingly oriented towards the development of biomimetic electronics that closely mimic the properties of biological tissues. Additionally, the functionalization of electronic component surfaces with biomolecules offers the potential to harness biochemical signals from the host tissue microenvironment and the extracellular matrix (ECM), thereby creating ‘bioactive’ electronics. In biohybrid neural interfaces, a layer of living cells at the brain-device interface not only enhances the emulation of native tissues but also functions as an active scaffold to facilitate tissue regeneration, cell migration, and differentiation [109–111].

The ECM is a noncellular scaffold found in all tissues; it is predominantly composed of laminin, fibronectin, and collagen and makes up approximately 10–20% of the total parenchymal volume of the brain. The most common biomaterial coating involves covalent immobilization or noncovalent adsorption of ECM components to reduce stiffness and promote cell-targeted attachment. Notably, the ECM has been successfully utilized as a dura mater repair material for over two decades [112]. ECM-based materials can be used as biomimetic substitutes for the natural matrix in the brain, thereby enhancing cellular adhesion to neural electrodes. Furthermore, the ECM has demonstrated haemostatic and immunomodulatory properties [57, 113]. ECM coatings have also been shown to attenuate the chronic inflammatory response associated with implanted polypropylene meshes [114]. A study examined the effectiveness of neurosurgical haemostatic materials in comparison with an ECM coating derived from astrocytes in rat brains in reducing the foreign body response after neural electrode implantation [115]. This study presented evidence that an astrocyte-derived ECM coating can reduce the extent of scar formation and astrogliosis surrounding an implantable neural electrode.

Research by Ceyssens et al. [116]. investigated the effects of a temporary ECM protein coating derived from thin slices of porcine gut tissue on the integration of microelectrode arrays with brain tissue. Their findings demonstrated that neural electrodes with the ECM coating caused significantly less damage to the surrounding brain tissue three months post-implantation than the uncoated control neural electrodes. This study demonstrated that ECM sheets can serve as appropriate temporary coatings for neural implants. Another study reported similar results in which a hydrogel derived from porcine bladder ECM was successfully employed in animal models to mitigate damage following traumatic brain injury [117]. Wu and colleagues successfully synthesized cell-laden collagen‒polypyrrole (PPy) hybrid hydrogel microfibers to investigate neural functional expression and electroconductive microenvironments [118]. The results demonstrated that the biomimetic three-dimensional microstructure, enhanced by microfluidic-chip-facilitated cell alignment, combined with the excellent electrical properties provided by PPy nanoparticles significantly augmented neuronal functional expression. While bioactive approaches, mainly based on ECM proteins, have demonstrated potential in mitigating the neuroinflammatory response to neural electrode surfaces, some limitations exist in their application. The clinical application prospects are restricted by the inherently short lifespan of the ECM. Additionally, studies have shown that natural ECM exhibits immunogenicity due to molecular alterations induced by high temperatures during the implant fabrication process [67]. Furthermore, variability in the molecular structure is anticipated when deriving ECM coating materials from different species, such as animals, potentially leading to additional complications, including pathogen transfer. To increase the biocompatibility and longevity of neural electrodes, employing coatings beyond those naturally derived, considering the inherent variability, may be imperative. The ECM can be customized based on an individual’s own tissues and cells. This approach allows tailoring of each polymer to align with the patient’s unique brain environment, potentially leading to a substantial improvement in the biocompatibility of neural electrodes.

Hydrogel‒tissue interfaces

Implants utilizing polymer hydrogels and biobased materials exhibit superior biocompatibility and bioactivity. These organic materials have been extensively employed in tissue repair and various other applications since their inception, and they have also shown considerable potential in the realm of neuroelectrodes [119–121]. Hydrogels are a class of superabsorbent, soft, and wet materials typically made from hydrophilic natural or synthetic polymers [121, 122]. Unlike dry electrode materials, hydrogels rich in water and ions offer potential for enhanced electrical stimulation and recording performance by leveraging both electronic and ionic activities [123, 124]. These polymers are crosslinked to form an intertwined three-dimensional (3D) network. This structure allows hydrogels to absorb large amounts of water and to swell without dissolving in water, closely mimicking the mechanical properties of the ECM. Hydrogels, as 3D polymeric networks, are well suited for various applications because of their unique properties, including customizable structures, a self-healing capability and responsiveness to external stimuli. This makes them a promising solution for addressing biomechanical mismatches at tissue‒electrode interfaces. They have been widely used in recent years in biomedical fields such as biosensing, tissue engineering, drug delivery, wearable electronics, and BCIs [105, 125]. In the context of implantable neural electrodes, glial scarring is partially attributed to the micromotion of relatively rigid implanted components relative to the pliable brain tissue. To mitigate this issue, researchers have applied a polyethylene glycol dimethylacrylate (PEG-DMA) coating (with an approximate modulus of 15 kPa) to rigid, silicon-based devices (with an approximate modulus of 200 GPa) to attenuate local strain fields [126, 127]. The findings suggest that hydrogel coatings on rigid probes can enhance biocompatibility and diminish the impact of brain micromotion. Hydrophilic surfaces have been shown to minimize nonspecific protein adsorption, thereby offering the potential to suppress microglial responses. Specifically, a hydrogel composed of a polymer could significantly reduce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, macrophage adhesion and chemotaxis. Additionally, a spin-coated cellulose hydrogel demonstrated an 80% reduction in 24-hour microglial adhesion in vitro [100, 128]. Similar findings were reported in another study, in which a photopolymerized polymer-based hydrogel exhibited reduced microglial adhesion at 56 days post-implantation, with a 30% reduction in microglial adhesion observed at six weeks post-implantation [129]. Additionally, optimization of the thickness of the hydrogel coating can minimize insertion damage and reduce the severity of the foreign body response. In a study conducted by Skousen et al. [130]. , sodium alginate hydrogels, which were designed to function as diffusion sinks, were applied to planar silicon microelectrode arrays with various thicknesses. The research demonstrated that increasing the hydrogel coating thickness to 400 μm significantly attenuated the foreign body response. This was evidenced by reductions in inflammation, BBB permeability, astrocyte hypertrophy, and neuronal cell loss. These findings indicated that the hydrogel coating served as an effective diffusion sink, passively reducing the steady-state concentration of proinflammatory cytokines at the biotic–abiotic interface.

A single polymer hydrogel, characterized by a single network and weak mechanical properties, poses practical challenges when used as the sole material for final applications. However, the lattice-like structure of hydrogels, with interconnected pores, not only retains a high-water content but also allows the incorporation of other materials into the network, which could improve the mechanical properties, stability, and other characteristics. Consequently, hydrogels have potential applications in neural bioelectronics beyond their traditional uses, such as drug delivery and active electrode coating [131, 132]. Strategies commonly employed to achieve conducting hydrogels include the use of conducting polymers to form hydrogels and the incorporation of conducting molecules, polymeric chains, and nanomaterials into the hydrogel matrix [133, 134]. Customization of the properties enables their utilization in various applications. A recent investigation focused on surface modification of electrodes using parylene-C and PEG, both of which are biocompatible polymers designed to enhance the biocompatibility of implanted microelectrode [135]. In vitro cell culture assays were conducted to assess the adhesion and proliferation of neuroblast cells on the coated electrodes, which revealed improved cell adhesion and proliferation. Similarly, another study introduced an innovative soft neural biointerface composed of polyacrylamide hydrogels embedded with plasmonic silver nanocubes [136]. The hydrogels were encapsulated within a silicon-based template, which served as a supporting element to ensure intimate neural–hydrogel contact and facilitate stable recording from specific sites within the brain cortex. The nanostructured hydrogels exhibited enhanced electroconductivity while replicating the mechanical properties of brain tissue. In vivo chronic neuroinflammation assays conducted on a murine model revealed no adverse immune response to the nanostructured hydrogel-based neural interface. A recent study conducted by Nam et al. proposed that nonbiodegradable β-peptide can form a multihierarchical hydrogel in conjunction with conductive nanomaterials, facilitating seamless integration with brain tissue through an enhanced contact area and robust coupling with neural tissue [137]. Furthermore, the supramolecular β-peptide hydrogel neural interface enables signal amplification through tight hydrogel/neural contact without inducing neuroinflammation. Recent advancements in probe design and materials are anticipated to mitigate biological and mechanical risks, thereby accelerating the medical clearance process. Although the referenced study suggested that hydrogel coatings can enhance biocompatibility, concerns persist regarding the degradation of hydrogels over time. Consequently, the long-term efficacy of hydrogel coatings requires thorough evaluation.

Flexible electrode–tissue interfaces

In previous decades, significant advancements were made in the development of novel flexible electrode devices designed to mitigate the biomechanical disparities between electronic systems and biological tissues. Most flexible electrodes are composed of conductive nanofillers and flexible substrates. For example, polymeric materials such as polyimide, polycarbonate, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), and polyurethane have been utilized to address the modulus disparity [138–140]. Owing to the difficulty that a flexible material such as polyimide faces when attempting to penetrate a gelatinous substance compared to a needle (Fig. 4B), implantable neural electrodes fabricated from biomaterials or highly flexible materials need to be temporarily stiffened during the implantation process. Methodologies often involve insertion of an ultraflexible microelectrode into the brain by temporarily affixing it to a rigid shuttle device using a dissolvable adhesive [26, 141, 142]. Nonetheless, the ultraflexibility and diminutive size of the microelectrode present significant challenges in achieving precise alignment with the shuttle device. Following implantation, the rigid shuttle device must be disengaged from the ultraflexible microelectrode and retracted from the brain parenchyma, a process that can induce additional brain tissue injury. Concurrently, the relative positions of the probe and neurons may shift, thereby compromising the stability of long-term neural recording [51, 143, 144].

Flexible electrodes are characterized by a low Young’s modulus, necessitating the use of a stiff backing or dynamic stiffness alteration for successful implantation. The application of collagen and other biologically derived materials characterized by dynamic hydration-based stiffness holds promise for advancing the development of flexible implantable neural electrodes. Established implantation techniques designed for rigid probes can potentially be utilized for these devices [142, 145]. In brief, a flexible microelectrode is immersed in a liquid coating material, such as a PEG bath, and gradually withdrawn into dry air. During this withdrawal process, the capillary forces of the PEG liquid coalesce the flexible microelectrode into thin, straight neural probes. After solidification in the air atmosphere, the self-assembled flexible microelectrode can accurately reach the target brain regions because of the rigid support provided by PEG. Following implantation, the outer coat is dissolved by bodily fluids within the brain tissue, thereby releasing the flexible microelectrode for long-term neural interfacing. In a separate study, the gold electrode utilized exhibited high flexibility to the extent that it could not be inserted into brain tissue without bending. To ensure structural integrity during implantation, the electrode was embedded in a rigid yet dissolvable gelatine B-based matrix material [146]. Furthermore, the configuration of the flexible electrode was maintained at the correct location in functional brain areas after three weeks, indicating that functionality was preserved post-implantation. Owing to the adaptability of this novel neural interface design, it represents a versatile tool for investigating the functions of various brain regions.

Several studies have proposed a biomimetic strategy that incorporates microscale ECM coatings on microfabricated flexible microelectrodes [23, 147]. The presence of ECM coatings does not adversely impact the electrochemical properties, mechanical properties, or in vivo recording performance of the electrodes. The implanted electrodes produce a significantly reduced chronic foreign body response. Notably, the Young’s modulus of the rigid electrodes is approximately 2 MPa, whereas the Young’s modulus of the hydrated Matrigel is approximately 450 Pa [49]. Upon implantation into brain tissue, the microelectrodes undergo a hydration process, resulting in a decrease in the Young’s modulus. To avoid hydration-induced buckling during surgical insertion, the electrodes must be rapidly inserted into brain tissue prior to their softening due to hydration. Histological analyses of brain tissue at 4 months after implantation revealed reduced astrocyte reactivity, decreased glial scarring, and increased neuronal density at the implantation sites versus the control group [147]. However, the implementation of thinner and elongated probe geometries, which are essential for deep brain interactions, may introduce a risk of mechanical failure of biomaterial devices due to buckling during the implantation process. Further research is required to determine the feasibility of utilizing these materials for extended in vivo studies. Conducting trials of neural electrodes in animal experiments is essential to verify the integrity of the devices during implantation and their functionality during prolonged placement in the brain. These demonstrations are considered critical prerequisites for progressing to human clinical trials.

Electrical properties of modified electrodes

Nerve tissue consists of nerve bundles containing multiple aligned assemblies, and neurons communicate with other cells through electrical signals, which play a key role in neurodevelopmental and brain maturation processes [118, 148]. Consequently, stimulation and transmission of these electrical signals are crucial for the survival, differentiation, functioning and repair of neurons. In light of this, biocompatible conducting materials have been extensively investigated to facilitate the growth of electrosensitive tissues, especially nerve tissue. In certain instances, external electrical stimulation is also employed to augment neuronal functional expression [149–151]. Thus, a critical consideration in surface modification of electrodes is the impact of electrode modifications on the recording of neural signals. A high electrical conductivity and a low impedance are desirable characteristics for neural microelectrodes [152]. In an ideal scenario, electrodes should possess both minimal dimensions and low impedance to effectively capture highly localized signals with minimal attenuation. Reducing the contact size of electrodes enhances spatial resolution and array density, thereby improving access to neural activity. This reduction also facilitates the development of smaller implants with the same channel count, which minimizes tissue displacement and enhances both integration and long-term stability. Recent research indicates that decreasing the electrode footprint to below 10 μm significantly reduces macrophage aggregation, thereby mitigating the acute immune response [153, 154]. Nevertheless, smaller electrodes inherently exhibit higher electrochemical impedance, which can degrade the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) due to increased thermal noise [155].

Recording quality correlates inversely with impedance, as higher impedance reduces signal amplitude and unit yield. To mitigate this, electrode surfaces can be functionalized to significantly lower impedance and signal attenuation. Most approaches increase effective surface area and capacitance by introducing 3D nanostructures, enhancing electrolytic contact beyond the planar geometry. Some coatings also provide faradaic charge transfer capabilities, offering additional transduction pathways between tissue and electrode [156–158]. Conductive polymers and their nanoscale structures have garnered significant attention in recent years because of their potential to improve both the electrical properties and mechanical properties (Fig. 5). Currently, the materials widely utilized for neural electrodes include noble metal nanomaterials (e.g., gold, silver, and platinum), carbon-based nanomaterials (e.g., graphene and carbon nanotubes), and conductive polymer nanoparticles [133, 145, 159]. Simultaneously, the modification of electrode surfaces through the incorporation of nanostructures, such as metal nanopatterns or roughened surfaces enhanced with nanoparticles, not only increases the surface area of the electrode interface and enhances contact with neural tissue but also imparts specific structural characteristics that improve biocompatibility. This, in turn, facilitates more favourable conditions for neuronal cell growth at the interface [160, 161]. The conductive nanomaterials are either dispersed within the coating matrix or directly functionalized on the surfaces of electronic interfaces [134]. In contrast, the coating materials utilized for neurostimulation must function as transducers of external energy fields to induce neural activation. Consequently, the materials intended for neurostimulation possess distinct criteria and pose unique challenges compared with those employed for neuromodulation. Notably, modifications involving nanomaterials and nanostructures on the electrode surface substantially influence their electrical properties.

Fig. 5.

Schematic overview of neural interfacing electrode strategies and approaches. Centred on ‘implantable neural interfaces’, the figure shows three major optimization methods: stiffness modification (extracellular matrices, hydrogels, polymers, etc.), electrical conductivity enhancement (gold nanoparticles, carbon nanomaterials, etc.), and inflammatory reaction suppression (glucocorticoids, active factors, proteins, etc.). Each section visually represents how to enhance the signal stability and longevity, improve neuronal survival, and reduce the severity of the foreign body response

Gold nanomaterials, specifically gold nanorods, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and gold nanospheres, are widely utilized in the biomedical industry because of their photothermoelectric properties, physical and chemical stability, low toxicity, and ease of surface modification [162–164]. The various methods for synthesizing gold nanomaterials include seed-mediated growth, template-assisted electrodeposition and electrochemical reduction [165, 166]. The photothermoelectric properties of conductive gold nanomaterials are notably attractive and are influenced by various factors, including the filler dispersion, aspect ratio, concentration, size, and shape [167–169]. Not all shapes are suitable for tuning; some morphologies are conducive to photothermoelectric approaches, among which nanospheres and nanorods have most commonly been utilized in nerve electrode research. Importantly, in a study, the observed impact on neurons was stimulation of cell growth rather than initiation of action potentials, which is typically regarded as true neurostimulation [170]. AuNPs can function as standalone devices or be integrated into nanostructured electrode arrays. In a study conducted by Kojabad et al., the performance of implanted neural microelectrode was significantly enhanced through nanostructural modification [171]. Specifically, the electrodes were coated with PPy nanotubes augmented with AuNPs, resulting in a tenfold reduction in the electrochemical impedance compared with that of the uncoated control. In a separate investigation, a nanoporous gold interface coating was synthesized, and the nanostructure of the nanoporous gold was demonstrated to facilitate close physical coupling of neurons by sustaining a high neuron-to-astrocyte surface coverage ratio [160, 172]. This study reported differential effects of nanoporous gold on astrocytic versus neuronal cell coverage and highlighted the reduction in astrocytic proliferation through in situ drug release from gold nanomaterial coating patterns. In addition, the conductive material could be combined with self-healing interfaces. A novel self-healing electrode has been engineered utilizing a composite material consisting of polyborosiloxane, silver (Ag) nanowires, and silver flakes. This electrode demonstrates exceptional electrical conductivity, achieving a value of 9.71 × 10⁴ S/m, in addition to exhibiting outstanding rheological characteristics. Significantly, it retains stable conductivity when subjected to tensile strains exceeding 60% and possesses the capability to autonomously repair itself following mechanical damage [173]. These findings suggest that noble metal nanomaterials hold significant promise as functional coatings for neural interfaces.

Carbon nanomaterials exhibit a broad spectrum of structural diversities, morphologies, physical characteristics, and chemical reactivities, which depend on the specific carbon allotrope employed [174, 175]. Carbon nanomaterials encompass a variety of forms, including zero-dimensional (0D) nanomaterials (e.g., carbon dots and nanodiamonds), one-dimensional (1D) nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibers), and two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials (e.g., graphene and its related variants) [176–178]. This category of nanomaterials holds great potential for various biomedical uses, including imaging, diagnostics, and therapeutics [179, 180]. Owing to their low toxicity to neurons in vitro and impressive physical and electrical characteristics, carbon nanomaterials have been extensively explored in the development of biosensors, conductive electrodes and neuroregeneration methods [175, 181, 182]. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have been employed as interface coating materials for implantable electrodes of neural tissue because of their distinctive properties, including a high aspect ratio and exceptional chemical and mechanical stability. Burblies et al.. demonstrated the efficacy of applying CNT coatings on platinum cochlear neural electrodes [183]. The application of CNT coatings resulted in a reduction in the electrical impedance and an increase in the microelectrode capacitance while supporting stable cell growth. Another study described an assembly technique for a 16-channel electrode array composed of carbon fibres with diameters less than 5 μm, each individually insulated with Parylene-C and subsequently fire-sharpened [184]. The carbon fibre electrodes demonstrated stable multiunit recording over several months. The consistency of the firing patterns during recording further corroborated the long-term stability of these clusters. Kozai et al. [43]. reported the development of an integrated composite electrode comprising a carbon-fibre core functionalized to modulate intrinsic biological processes and a polymer-based recording pad designed for cortical recording in rats. These implants were significantly smaller than conventional implantable electrodes and exhibited favourable mechanical compliance with brain tissue. Maughan et al. documented the creation of an electroconductive composite material based on pristine graphene for application within the CNS [181]. This composite comprised type I collagen integrated with 60 wt% pristine graphene and achieved a conductivity of approximately 1.5 S/m, which meets the requirement for effective electrical stimulation. Neuronal cultures on these composite films demonstrated excellent growth, with glial cells showing no significant alterations in inflammatory markers. These findings suggest that carbon composites serve as a multifunctional neurotrophic platform, effectively balancing physiologically relevant electrical properties and biocompatibility. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that the use of carbon nanomaterials is a promising approach for enhancing the electrical properties of implantable electrodes. low impedance of gap junctions and the high electrical conductivity.

Reducing neuroinflammation by modifying electrodes

Previous research shows that electrode implantation causes acute inflammation, disrupting tissue homeostasis crucial for information processing. Initially, excitatory neurotransmission markers increase, followed by a rise in inhibitory markers after four weeks [71, 185]. Over time, signal quality declines, with efficacy compromised by unstable signals and limited longevity, reducing the therapeutic potential of implantable electrodes [89, 186, 187]. Signal degradation is primarily due to electrode detachment from neurons and neuronal death, with chronic inflammation leading to scar tissue formation that isolates the electrode, increasing impedance and reducing electrical connectivity [188–190]. Gliosis pushes tissue away, increasing the distance between the electrode and neurons, lowering the amplitude of neuronal signals [51, 191]. Immunocompatibility is a critical factor in the design and fabrication of chronically implanted neural electrodes.

To alleviate the above problem, enhancing the immunocompatibility of electrodes is crucial. A strategy to minimize the immune response to implanted electrodes involves coating them with biologically active molecules (proteins or cell adhesion peptides) [192–194] or drugs (dexamethasone and cortisones) [195, 196] that possess anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties. Inflammation suppressors and neural adhesion promoters have also been utilized in microelectrode modifications to reduce microglial attachment and inhibit microglial activation [197, 198]. A recent study reported the administration of dexamethasone to observe the real-time microglial response to an implanted probe with in vivo two-photon microscopy [199]. In this investigation, the researchers examined the cellular microglial response to microdialysis probe insertion up to six hours post-implantation while infusing either dexamethasone or artificial cerebrospinal fluid for contrast. The experimental results indicated that dexamethasone, which was utilized for localized release, could attenuate immune inflammatory responses to implantable neural electrodes in vivo. In addition, James R. et al. [73]. proposed a method involving covalent attachment of the L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1) to the surface of neural electrodes. This study demonstrated that covalent attachment of brain-tissue-derived L1 to neural probes could attenuate glial scarring. L1 coatings have been shown to provide sustained mitigation of neuronal death and gliosis for at least eight weeks. While neural adhesion molecules and pharmacological agents enhance neuronal adhesion and concurrently reduce microglial attachment and activation, their effectiveness generally decreases as these molecules are depleted [200].

A recent study demonstrated that thin films of silica prepared via a sol-gel process for surface modification of implantable neural electrodes could mitigate the immune response and promote neural integration with implants [201]. The experimental results indicated that thin films of silica prepared via a sol-gel process could be transformed into robust neural-permissive substrates that support neurite outgrowth and adhesion. Moreover, this support for cell growth provided by the hybrid organosilica did not apply to astrocytes. These findings highlight the potential of sol-gel coatings to selectively modulate the cell immune response and promote neural integration with implant devices. Bin et al. [127]. synthesized nanocoatings enriched with polyionics at the surface using an initiated chemical vapour deposition process. This vapour-based method enabled conformal surface engineering of neural electrodes, allowing facile tailoring of the surface composition and structure. Microglial adhesion was significantly diminished on polyionic-modified surfaces, with the surfaces exhibiting mixed charges demonstrating the most pronounced reduction, resulting in an over 50% decrease in the number of adherent microglia. The results of these studies well demonstrate that immune intervention is a reliable strategy that leads to favourable short- and long-term outcomes for BCIs.

For decades, metal microwire bundles have been effectively utilized in experimental neuroscience, including in chronic applications [202, 203]. A seminal study by Misra et al. established a clinical protocol for implanting platinum microwire bundles into the mesial temporal lobe of patients with epilepsy, facilitating continuous single-neuron recordings over a 15-month inpatient period [204]. Their findings demonstrated the clinical feasibility and long-term reliability of microwire-based deep brain recordings. Another study showed that ultraflexible open-mesh electronics, administered via syringe injection into rodent brains, exhibited excellent biocompatibility and stable signal acquisition [205]. Quantitative analyses conducted at 4- and 12-weeks post-implantation revealed consistent levels of neuronal, axonal, astrocytic, and microglial markers from the device surface to baseline tissue, suggesting minimal immune response and seamless integration. These attributes render ultraflexible mesh probes as highly promising tools for chronic in vivo neural recording and modulation. While scientific and technological advancements in BCIs hold great promise, their use—particularly in the context of implantable neural electrodes—raises significant ethical considerations. The surgical implantation of BCIs carries risks, including infection, immune rejection, unintended neurological side effects, and device failure. Ensuring patient safety is paramount, and rigorous clinical testing must be conducted before such devices can be widely adopted. Additionally, obtaining informed consent is particularly complex for individuals with severe neurological impairments, as their ability to fully comprehend the risks and benefits of experimental BCIs may be limited. Researchers and medical professionals must establish clear, accessible communication strategies to ensure that patients and their caregivers can make informed decisions.

Conclusion and future perspectives

There is substantial interest in the application of BCIs because of their potential to increase the quality of life of individuals with severe neurological conditions. Advances in implantable neural electrodes, particularly in the areas of the implantation technique, outer pattern size, and biocompatible materials, present new opportunities for exploring brain functions, developing therapeutic strategies for neurological disorders, and advancing scientific applications (Fig. 6). In this review, we examine the evolution of and recent advancements in neural interfaces within BCIs systems, which hold significant promise for rehabilitation in patients with neurological disorders. Nonetheless, many important issues remain unresolved before implantable brain‒machine interfaces can be transitioned from laboratory research to clinical practice. Specifically, the long-term biocompatibility of neural electrodes remains a major challenge, directly limiting the widespread application of BCIs. As a result, a key focus of BCIs development is the optimization of the neural interfaces for achieving seamless integration between biological and electronic systems. The trajectory for the next generation of BCIs is outlined, with particular emphasis on the successful application of coatings (both natural and synthetic) and topographical modifications in neural electrode design. These modifications have proven effective in enhancing signal stability and longevity, improving neuronal survival, and reducing the foreign body response.

Fig. 6.

The principal research directions and novel application areas of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). The upper section highlights three pivotal areas of focus: the modification of stiffness, electrical properties, and neuroinflammation, which are presently being addressed through advancements in intracortical electrode design and innovative engineering methodologies. The lower section depicts five representative application domains of BCIs, communication, diagnosis, bio-monitoring, disability assistance, and industrial control

In future research endeavours, an innovative neural interface with an appropriate Young’s modulus must be developed to ensure precise implant placement within target brain regions, thus minimizing the insertion footprint and tissue trauma. The development of bioactive and electroconductive materials that can be seamlessly integrated with natural nervous tissues would minimize the influence of material properties and other secondary factors involved. Such advancements are expected to mitigate both acute injury and chronic inflammatory responses, thereby facilitating more favourable neural interfacing. Owing to these outstanding features, these systems could maintain stable and intimate contact at the electrode‒tissue interface and reduce the foreign body response in terms of scarring and neuroinflammation, enabling efficient long-term recording of high-quality neural signals. This objective would facilitate the development of entirely implantable, long-term stable, and high-precision neural interfacing electrodes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AuNPs

Gold nanoparticles

- BCIs

Brain‒computer interfaces

- BBB

Blood‒brain barrier

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CNTs

Carbon nanotubes

- DBS

Deep brain stimulation

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- ECoG

Electrocorticography

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- PDMS

Polydimethylsiloxane

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

Author contributions

WG and ZY: prepared the manuscript draft, collected the data, and approved the final manuscript. HZ and YX: supervised the study, writing, editing the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. HW and JY: collected the data, revised, read, and approved the final manuscript. JY and CN: supervised the study and prepared the figures, tables, and approved the final manuscript. PL and MX: collected the data, read, and approve the final manuscript. LH and ZY: conceived the idea, designed the study, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by grants from the National Innovation Platform Development Program (No. 2020021105012440), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82172524, 81974355), the Major Program (JD) of Hubei Province (No. JD2023BAA005), and the Key R&D Program Project of Hubei Province (No.2021BEA161).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Weihang Gao, Zineng Yan and Hong Zhou contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Mao Xie, Email: xiemao666@outlook.com.

Li Huang, Email: 13907130486@163.com.

Zhewei Ye, Email: yezhewei@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Maas AIR, Menon DK, Manley GT, Abrams M, Åkerlund C, Andelic N, Aries M, Bashford T, Bell MJ, Bodien YG, et al. Traumatic brain injury: progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(11):1004–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kocabicak E, Temel Y, Höllig A, Falkenburger B, Tan SK. Current perspectives on deep brain stimulation for severe neurological and psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1051–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daskalakis ZJ. Theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression: when less May be more. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 7):1860–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen T-D, Khanal S, Lee E, Choi J, Bohara G, Rimal N, Choi D-Y, Park S. Astaxanthin-loaded brain-permeable liposomes for parkinson’s disease treatment via antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses. J Nanobiotechnol. 2025;23(1):78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouton CE, Shaikhouni A, Annetta NV, Bockbrader MA, Friedenberg DA, Nielson DM, Sharma G, Sederberg PB, Glenn BC, Mysiw WJ, et al. Restoring cortical control of functional movement in a human with quadriplegia. Nature. 2016;533(7602):247–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ajiboye AB, Willett FR, Young DR, Memberg WD, Murphy BA, Miller JP, Walter BL, Sweet JA, Hoyen HA, Keith MW, et al. Restoration of reaching and grasping movements through brain-controlled muscle stimulation in a person with tetraplegia: a proof-of-concept demonstration. Lancet. 2017;389(10081):1821–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H, Jiao L, Yang S, Li H, Jiang X, Feng J, Zou S, Xu Q, Gu J, Wang X, et al. Brain-computer interfaces: the innovative key to unlocking neurological conditions. Int J Surg. 2024;110(9):5745–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wandelt SK, Bjånes DA, Pejsa K, Lee B, Liu C, Andersen RA. Representation of internal speech by single neurons in human supramarginal gyrus. Nat Hum Behav. 2024;8(6):1136–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiavone G, Kang X, Fallegger F, Gandar J, Courtine G, Lacour SP. Guidelines to study and develop soft electrode systems for neural stimulation. Neuron. 2020;108(2):238–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochberg LR, Bacher D, Jarosiewicz B, Masse NY, Simeral JD, Vogel J, Haddadin S, Liu J, Cash SS, van der Smagt P, et al. Reach and Grasp by people with tetraplegia using a neurally controlled robotic arm. Nature. 2012;485(7398):372–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benabid AL, Costecalde T, Eliseyev A, Charvet G, Verney A, Karakas S, Foerster M, Lambert A, Morinière B, Abroug N, et al. An exoskeleton controlled by an epidural wireless brain-machine interface in a tetraplegic patient: a proof-of-concept demonstration. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(12):1112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Wu S, Yang H, Bao Y, Li Z, Gan C, Deng Y, Cao J, Li X, Wang Y, et al. Intravascular delivery of an ultraflexible neural electrode array for recordings of cortical spiking activity. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):9442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casson AJ, Smith S, Duncan JS, Rodriguez-Villegas E. Wearable EEG: what is it, why is it needed and what does it entail? Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2008;2008:5867–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buzsáki G, Anastassiou CA, Koch C. The origin of extracellular fields and currents–EEG, ecog, LFP and spikes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(6):407–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JM, Pyo Y-W, Kim YJ, Hong JH, Jo Y, Choi W, Lin D, Park H-G. The ultra-thin, minimally invasive surface electrode array neuroweb for probing neural activity. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahnood A, Chambers A, Gelmi A, Yong K-T, Kavehei O. Semiconducting electrodes for neural interfacing: a review. Chem Soc Rev. 2023;52(4):1491–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]