Abstract

During development and also in adulthood, synaptic connections are modulated by neuronal activity. To follow such modifications in vivo, new genetic tools are designed. The nontoxic C-terminal fragment of tetanus toxin (TTC) fused to a reporter gene such as LacZ retains the retrograde and transsynaptic transport abilities of the holotoxin itself. In this work, the hybrid protein is injected intramuscularly to analyze in vivo the mechanisms of intracellular and transneuronal traffics at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). Traffic on both sides of the synapse are strongly dependent on presynaptic neural cell activity. In muscle, a directional membrane traffic concentrates β-galactosidase-TTC hybrid protein into the NMJ postsynaptic side. In neurons, the probe is sorted across the cell to dendrites and subsequently to an interconnected neuron. Such fusion protein, sensitive to presynaptic neuronal activity, would be extremely useful to analyze morphological changes and plasticity at the NMJ.

The precision with which neuronal circuits are assembled during development is critical in defining the behavioral repertoire of a mature organism. Analyzing brain functioning in normal and pathological conditions will require to integrate functional information onto anatomical data at a cellular and molecular level. To that goal, genetic tools are being constructed in parallel with improving performances in molecular imaging techniques. The atoxic C-terminal fragment of tetanus toxin (TTC) fused to a reporter gene such as LacZ can traffic retrogradely and transcellularly inside a restricted neural network. After injection into the tongue, the enzymatic activity could be detected in the hypoglossal nucleus and also in connected neurons of the brainstem areas (1). However, the molecular mechanisms involved in protein transfer between two synaptically connected cells are still unknown and should be investigated at several levels of integration. To explore the in vivo intracellular and transneuronal traffic molecular details at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), we have chosen to inject the purified hybrid protein β-galactosidase (β-gal)-TTC intramuscularly and follow the transport details by confocal and electron microscopy. A high amount of tracer protein thus is made available locally to progress into endocytic itineraries. Visualization of spreading thus is facilitated in a simple neuromuscular system.

In this report, we show that β-gal-TTC allows selection and visualization of a specific membrane traffic, demonstrating in vivo the feasibility of tracing endocytic pathways at an NMJ. On both sides of the synapse, normal motoneuronal activity has strong effects on the probe intracellular distribution. In muscle, motoneuronal activity polarizes the membrane traffic to the active NMJ compartment. In neuron, the hybrid protein is sorted rapidly across the cell to dendrites and subsequently to an interconnected neuron, suggesting the existence of a retrograde intraneuronal feedback traffic.

Materials and Methods

In Vivo Intramuscular Injection.

All experiments were made in accordance with French and European Community guidelines for laboratory animal handling. Six-week-old CD1 mice were obtained from Charles River Breeding Laboratories. Intramuscular injection of β-gal-TTC protein (25 μl, 1 μg/μl) purified as described (1) was given into the gastrocnemius or the tongue. Animals were killed 2 or 6 h after injection. β-Gal was administrated systematically as a negative control. Under deep anesthesia, animals were perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde. Injected muscles and brains were removed and rinsed in PBS before 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactoside (X-Gal) in toto reaction or were frozen before cryosectioning into 20 μm-thick slices for immunohistological analysis.

X-Gal Staining and Electron Microscopy.

For in toto β-gal activity detection, tissues were washed three times for 5 min at 4°C with PBS and stained in X-Gal solution (0.8 mg/ml X-Gal/4 mM potassium ferricyanide/4 mM potassium ferrocyanide/4 mM MgCl2 in PBS) at 37°C overnight. Electron microscopic analysis was performed by using X-Gal reaction with the electron-dense 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indol precipitate. After X-Gal coloration, the cells were fixed further in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and processed as described (2).

Immunohistochemistry.

Slices were stained with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against β-gal (1:500, Cappel) followed by Alexa 488 conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobin (1:100, Molecular Probes). NMJs were identified by labeling acetylcholine receptor (AChR) with tetramethylrhodamine-labeled α-bungarotoxin (BTX, 2 μg/ml, Calbiochem) at 37°C for 30 min. Confocal laser scanning immunofluorescence analysis was performed with a TCS4D confocal microscope (Zeiss) using a Laser Technic argon-krypton laser (Leica, Deerfield, IL) in multiline operating mode. Fluorescence acquisition was performed with the 488- and 568-nm lasers lines.

Gastrocnemius Denervation Experiments.

In four mice, sciatic nerve transection was performed under deep anesthesia. Approximately 5 mm of nerve were removed. Mice were checked for hind limb paralysis after surgery. Eighteen hours after nerve transection, mice were inoculated in the denervated gastrocnemius as described above. For controls, mice were inoculated contralaterally into the innervated gastrocnemius. Sciatic nerves were examined at necropsy, and transections were confirmed in all cases.

In Vivo Tetrodotoxin (TTX) and BTX Administrations.

For TTX (Sigma) administration, four mice were anesthetized, and the left sciatic nerve was exposed in the upper thigh. An osmotic minipump (Alzer 1007D) containing TTX (500 μg/ml) was s.c.-implanted as described (3). Nerve-conduction blockage was maintained for 4 days. The absence of toe extension and flexion reflexes, indicators of a complete and continuous nerve-conduction blockage, were tested daily. As control, an osmotic minipump was filled with a sterile saline solution and implanted in the same way as in others animals. No muscle blockade was detected. β-Gal-TTC hybrid protein was injected bilaterally in the gastrocnemius 4 days after the minipump implantation. BTX (6 μg in 30 μl of sterile saline, Calbiochem) was injected under anesthesia in the left gastrocnemius of four mice 30 min before β-gal-TTC hybrid protein injection. Alternatively, BTX was injected 12 h before protein injection. Paralysis of the left hind limb was obvious after recovery from anesthesia and for the following hours.

Results

β-Gal-TTC Endocytosis Depends on Neuronal Activity.

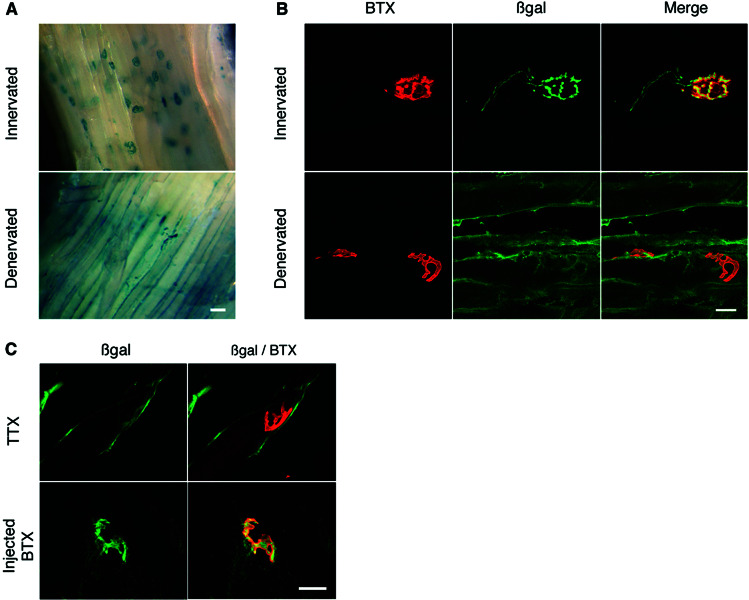

After β-gal-TTC injection into hind limb or tongue muscles, the hybrid protein binds rapidly to the NMJ (Figs. 1A and 4, respectively). Its transport along the motoneuronal axon leaving the NMJ also is rapidly detectable (Fig. 1B). To assess the influence of motor nerve activity the sciatic-gastrocnemius system was chosen, because it is easier to reach and manipulate than the hypoglossal nerve. Injection of β-gal-TTC fusion protein was performed 18 h after axotomy into innervated and denervated gastrocnemius, with visualization of protein localization performed 6 h later. A spectacular effect was observed after nerve sectioning in vivo; the hybrid protein distribution was strongly affected (Fig. 1 A and B). β-Gal-TTC no longer stained the NMJ, and no axonal labeling of the motoneuron synapse ending was detectable. This effect was observed in less than 1 day after denervation and thus more rapidly than the AChR redistribution or the reorganization of the Golgi apparatus (4). Neuronal integrity therefore is necessary for TTC internalization into the motoneuron and also for its concentration at the NMJ. To locate the origin of the activity necessary for TTC endocytic transport precisely, two specific neurotoxins, TTX and BTX, were used in vivo. Mice were checked for NMJ physiological inactivation by paralysis of the hind limb. Presynaptic neuromuscular activity was blocked by TTX, a specific sodium channel-inhibitory agent. TTX is less traumatic than axotomy, because only synaptic transmission is blocked without affecting nerve integrity. Four days after chronic perfusion of the sciatic nerve with TTX (3), β-gal-TTC was injected, and the protein distribution was analyzed (Fig. 1C). By in toto analysis, β-gal-TTC appeared, as by axotomy, to be distributed along the entire muscle length rather than concentrated at the NMJ. No labeling was detected along the axon and synaptic ending nor significantly in the NMJ. Postsynaptic transmission was subsequently stopped by BTX, which specifically binds and blocks the AChR without affecting nerve functionality. The spatial and temporal characteristics of the fusion protein endocytic traffic appeared normal in both muscle and motoneuron, although the hind limb was paralyzed (Fig. 1C). AChR stimulation in the postsynaptic membrane therefore is not involved in the detected endocytic transport.

Figure 1.

Activity-dependent β-gal-TTC localization at the NMJ. (A) The fusion protein was injected intramuscularly in innervated gastrocnemius or 18 h after sciatic nerve transection. Protein localization was investigated 6 h later in toto by X-Gal coloration. β-Gal-TTC protein was localized mainly at the NMJ in innervated gastrocnemius, whereas the denervated muscle showed a diffuse distribution of the fusion protein along the surface structures, with no labeling in the motoneuron being detected. (B) Coimmunocytolocalization of β-gal-TTC by an anti-β-gal antibody and of the NMJ by BTX. In innervated muscle (Upper), a strong β-gal-TTC concentration was detected at the NMJ and into axons. By contrast, in denervated gastrocnemius (Lower), the fusion protein was not concentrated specifically in inactive NMJ. A weak colabeling observed in some cases was not significant as determined by using the Student's t test with a standard statistical threshold of a 5% significance (P < 0.001). (C) Confocal colocalization analysis after TTX blockage of nerve conduction (Upper) or after postsynaptic transmission blockage by BTX (Lower). After TTX administration, the same β-gal-TTC distribution was observed as that in denervated muscle. Injection of a saturating dose of fluorescently labeled BTX, which stops muscle stimulation without affecting nerve functionality, had no effect on β-gal-TTC distribution. (Scale bars: A, 40 μm; B–C, 20 μm.)

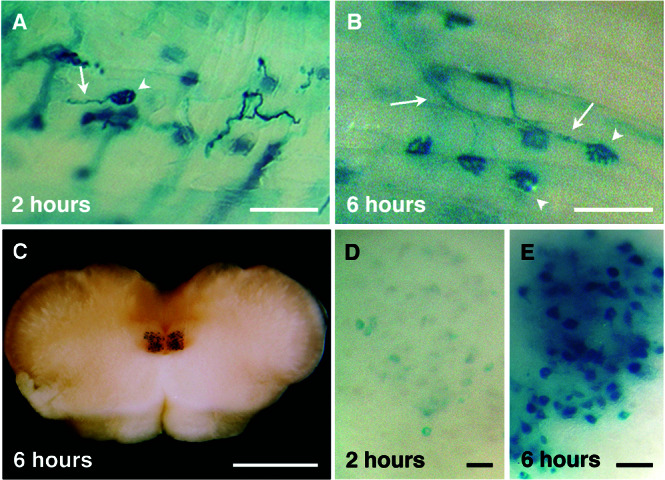

Figure 4.

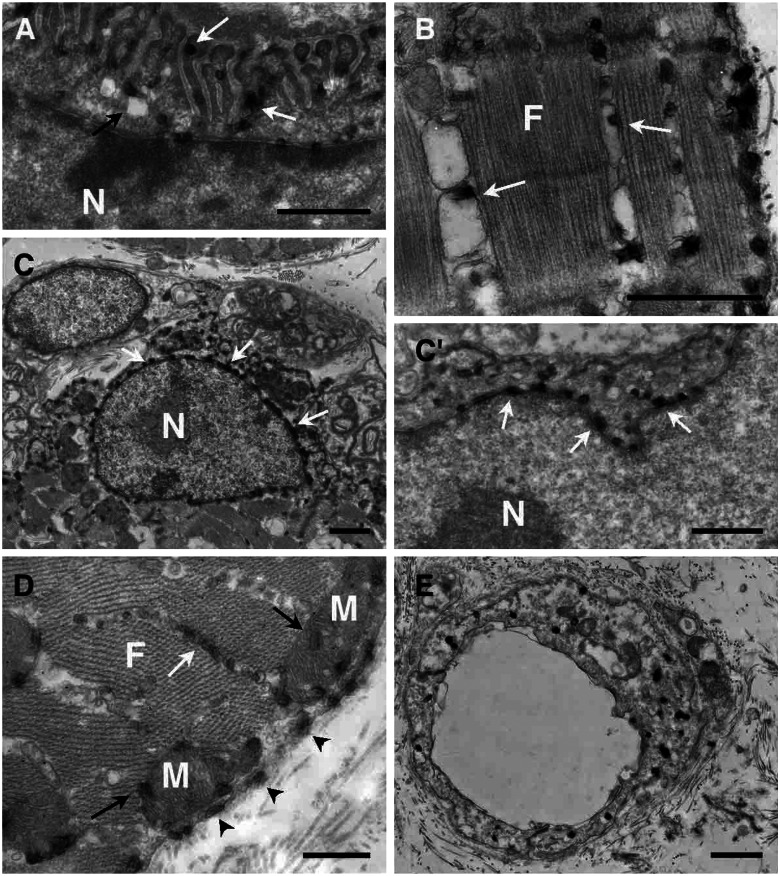

β-Gal-TTC transport kinetics into the hypoglossal nuclei. The hybrid protein was injected intramuscularly into the tongue, and an in toto X-Gal staining was performed 2 (A and D) or 6 (B, C, and E) h later. β-Gal-TTC was concentrated rapidly at the NMJ and taken up by the connected axons (A and B, arrowheads and arrows, respectively). Motoneuronal soma in the hypoglossal nuclei displayed a weaker intensity 2 h (D) than 6 h after injection (E). (C) Brainstem section showing the hypoglossal nuclei stained 6 h postinjection. (Scale bars: A–B, 100 μm; C, 1 mm; D–E, 20 μm.)

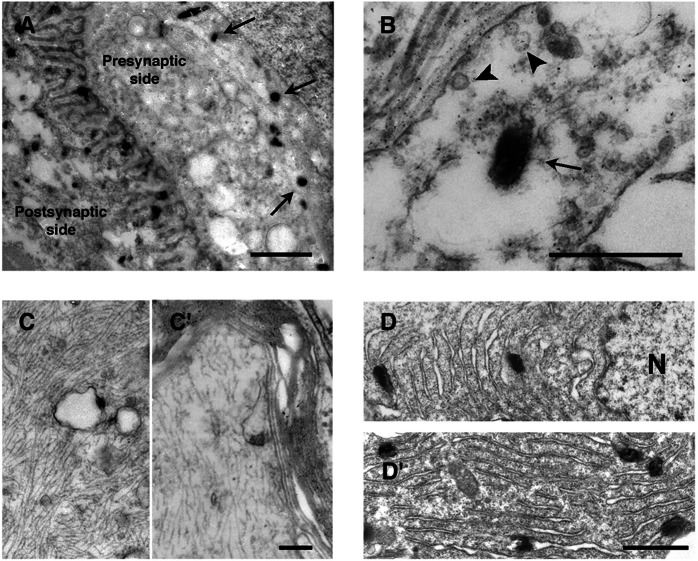

β-Gal-TTC Is Always Associated with Membranous Compartments.

To study the cellular compartments involved more precisely, electron microscopy analysis was performed. In the presynaptic side, staining was observed in large uncoated vesicles (200–300 nm; Fig. 2 A and B) and all along the axon (150–200 nm) (Fig. 2 C and C′). In the motoneuron soma, which contains most of the staining, the hybrid protein was linked to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane around the nucleus (Fig. 2 D and D′). Labeling was always associated to membranes; it was never found free in the vesicles lumen, cytoplasm, or other structures. We noticed that Schwann cells were also labeled weakly (data not shown). At the postsynaptic side of the NMJ, a strong staining was always associated to membranes: linked to the junctional folds membranes (Fig. 3A), associated with vesicular body membranes of the under end-plate region (Fig. 3A) and the plasma membrane (Fig. 3D), among the myofibrils associated with the sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes (Fig. 3 B and D), linked to the perinuclear endoplasmic reticulum membrane of the subjunctional nuclei (Fig. 3 C and C′), around or into the mitochondria (Fig. 3D), and linked to membranes associated with transverse tubules (data not shown). A weak staining in the extrajunctional areas of muscle cells also could be detected similarly localized at the plasma and sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes and at the perinuclear reticulum (data not shown). Finally, an intense vesicular staining also was observed in blood vessel endothelial cells (Fig. 3E). In denervated gastrocnemius, in agreement with fluorescent and X-Gal stainings (Fig. 1), all labeling was detected along the muscle cells associated with the plasma and sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes and to a lesser extent linked to the perinuclear endoplasmic reticulum membrane (data not shown). We conclude that the fusion protein is always transported associated with membranous compartments.

Figure 2.

β-Gal-TTC neuronal localization by electron microscopy. Electron microscopic analysis was performed by using X-Gal reaction with the electron-dense 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indol precipitate. (A) On the NMJ motoneuronal side, X-Gal signals (arrows) were detected away from the active zone into large uncoated vesicles (B, arrow); no labeling was detected in small coated synaptic vesicles (B, arrowhead). (C and C′) Staining along the axon was associated with the membranes of large vesicles. (D) In motoneuronal soma, precipitate was found in the perinuclear endoplasmic reticulum. N; nuclei. (Scale bars: A, 1 μm; B, 0.4 μm; C and C′, 0.2 μm; D and D′, 0.5 μm.)

Figure 3.

β-Gal-TTC intramuscular localization by electron microscopy. (A) A strong fusion protein concentration was observed on the NMJ postsynaptic side. Staining was detected associated with the junctional folds membranes (white arrows) and vesicular membranes (black arrows). Labeling also was observed in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (white arrows, B and D). Around the subjunctional nuclei, staining was associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (C and C′, white arrows). (D) Precipitate also was observed in mitochondria (black arrows) and associated with the muscle plasma membrane (arrowheads). (E) In blood vessel endothelial cells, an intense staining also was detected, linked to smaller vesicle membranes. F, myofibrils; N, nuclei; M, mitochondria. (Scale bars, 1 μm.)

Kinetic Analysis of β-Gal-TTC Endocytic Pathways.

To characterize in vivo the cellular mechanisms of those endocytic pathways further, kinetic analyses in neuron and muscle were performed. When the fusion protein was injected into the tongue, the hybrid protein was transported in less than 2 h to the motoneuron soma localized in the brainstem hypoglossal nuclei (Fig. 4D), and a more intense staining was obtained after 6 h (Fig. 4 C and E). These data are consistent with the known intraaxonal retrograde transport (200 mm/day) of membranous organelles associated with microtubules (for review see ref. 5). In muscle, however, the hybrid protein was concentrated rapidly at the postsynaptic side of the NMJ (Fig. 4 A and B) even with very low protein concentration (1 μg) but was never observed in a significant amount in the deep muscle structures. Moreover, after 24–48 h, most of the NMJ staining had disappeared. Stability of the protein is not involved, because it could be detected after several days in neuronal (1) and endothelial cells (data not shown). An exocytosis process at the NMJ could explain these data. Indeed, after DNA intramuscular injection, the hybrid protein was secreted by a muscle fiber at the NMJ. In this case, expression of β-gal-TTC has been observed in a single fiber, followed by hypoglossal nerve and nuclei labeling (data not shown and ref. 6).

Discussion

Retrograde transcellular signaling through the synaptic cleft is known to play crucial roles in the formation, maturation, and plasticity of synaptic connections (7, 8). However, the molecular mechanisms involved in a protein transneuronal transport between two synaptically interconnected cells are not identified yet. In previous work, we have shown that the TTC, fused to a reporter gene, could be used to analyze simple neuronal networks (1). In this in vivo study at an NMJ, endocytic pathways have been investigated and visualized by intramuscular injection of the purified hybrid protein. Endogenous motoneuronal activity strongly affects β-gal-TTC endocytic pathways. Axotomy and TTX in vivo delivery away from the target muscle prohibit β-gal-TTC neuronal internalization but also β-gal-TTC traffic and concentration at the NMJ. However, blocking muscular AChR activity by BTX administration yields no effect, establishing the role of presynaptic activity on internalization and concentration of the fusion protein. Neural activity-induced changes in the organization of the muscle Golgi complex and microtubules have been reported already, although they occur on a much longer time scale (4, 9). Regulation of gene expression by specific patterns of impulse activity is essential for skeletal muscle functions (ref. 10 and references therein). However, in our studies β-gal-TTC traffic in muscle to the NMJ is completed in less than 2 h, and in motoneuron by that time, the soma starts to be labeled. Fast endocytic pathways therefore are involved.

Endocytosis of the fusion protein requires that TTC first binds to its specific receptors present on the cell plasma membranes. Two different receptors for tetanus neurotoxin have been identified, polysialogangliosides GD1b and GT1b and an N-glycosylated 15-kDa receptor protein, p15, with a reported expression on neural cells. The TTC fragment also displays gangliosides and p15-binding properties (11–15). Compared with neuronal tissues, b-type gangliosides are expressed less abundantly in skeletal muscle or endothelial cells (16, 17), but that could explain binding and endocytosis into these cells. Gangliosides are known to segregate into membrane lipid microdomains called rafts and/or caveolae, which contain high amounts of glycosphingolipids and cholesterol but also are enriched in a specific signaling molecule(s) (for reviews see refs. 18–20). The aggregation of surface molecules is a fundamental mechanism for a cell to regulate transmembrane signaling as well as the first step in endocytosis. Recently it was reported that agrin, an aggregating protein crucial for the formation of the NMJ, is important in the reorganization of membrane lipid microdomains and mediates their active directional transport to the area of cell–cell contact in neural and immune cells (21). Agrin, secreted from motoneuron and muscle cells, acts extracellularly to trigger the local aggregation of molecules. Alternative splicing is known, resulting in several agrin isoforms with varying aggregating activity (22). Neuronal activity via secreted molecules such as agrin could induce a clustering of disperse and specific rafts at the NMJ, perhaps for signal transduction such as Ras signaling recently reported to be involved in nerve activity-dependent regulation of muscle genes (19, 23). By this way, β-gal-TTC bound to its membrane receptors could be concentrated at the NMJ directly or after an internalization step when rafts reach a critical size. Without neural activity, internalization could occur all along the muscle surface into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, but the dynamics of concentration or clustering would be impaired.

In nerve terminals, intense clathrin-mediated and clathrin-independent synaptic vesicle traffic has been described extensively and is crucial for synaptic transmission (24–27). The recycling traffic of small synaptic vesicles has been postulated to be essential to the neurotoxin internalization (28). However, on cultured spinal cord neurons or liver cells, noncoated invaginations and vesicles are involved (29, 30). In our experiments, the hybrid protein was found away from the active zones in large uncoated vesicles. Our experimental approach does not allow the detection of the dynamics of the first initial endocytic steps, and we could not eliminate the possibility that the fusion protein was first taken up at the NMJ into small synaptic vesicles before being delivered into larger vesicles. These latter vesicles likely are intermediary compartments such as endosome-like vacuoles (31) or caveosome-like compartment as described recently in simian virus 40-infected epithelial cells (32). They can undergo fusion and fission reactions that could explain the smaller size of axonic vesicles detected in our experiments.

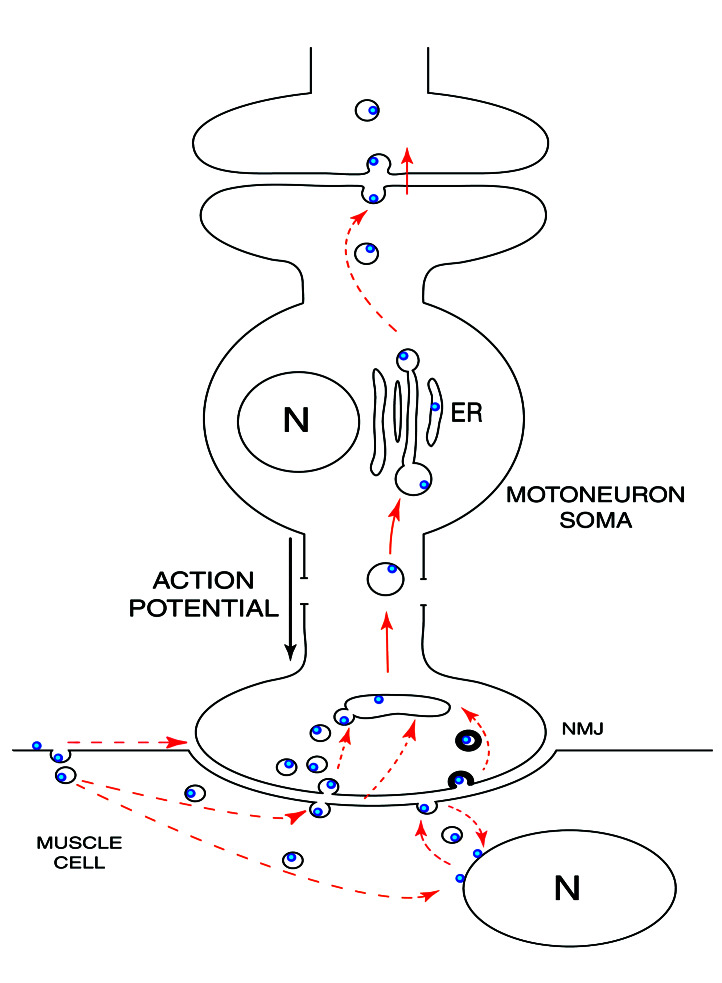

During host cell invasion, a broad range of microorganisms are known to co-opt lipid rafts trafficking. Pathogens and their products such as Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin type I and cholera toxin, which binds GM1 gangliosides at the cell surface (33, 34), or viruses such as simian virus 40 (35) are transported via caveolae to specific compartments inside the cell. By this means, they avoid lysosomal degradation and are targeted to particular subcellular sites. The tetanus toxin TTC fragment, which binds to its membranous receptors gangliosides GT1b, GD1b, and/or p15 protein, allows us to visualize such an endocytic constitutive pathway inside the central nervous system. In muscle and neural cells, the hybrid protein thus is sorted to different fates and subcellular localizations (Fig. 5). In motoneurons, the hybrid protein is taken up rapidly in nerve endings and transported across the cell to dendrites avoiding degradation. Transsynaptic transfer to interconnected neurons then will occur (1), presumably by a similar activity-dependent exocytic-endocytic pathway. By contrast, in muscle cells the reaction is transitory and localized to the muscle surface structures, a directional transport concentrating the hybrid protein rapidly to the NMJ. Whatever the details of the traffic mechanisms, the net overall effect is β-gal-TTC transport from an active motoneuronal junction to an active dendritic synapse. Further studies are needed to analyze this membrane traffic molecularly and to know if such feedback that sense neuronal activity could be an integrative mechanism at the neural network level.

Figure 5.

β-Gal-TTC presumed pathways. After intramuscular injection, β-gal-TTC is concentrated rapidly at the NMJ. The dashed arrows represent various hypothetical pathways. In motoneurons, the hybrid protein is found in large uncoated vesicles and then transported retrogradely to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Internalization by an interconnected neuron will then occur. N, nuclei.

Such a retrograde transsynaptic reporter protein would be extremely useful to analyze morphological and structural changes associated with activity during the formation, maturation, and plasticity of synaptic connections. Its application in transgenic animals, however, will require engineering to target the transgene to the appropriate vesicular subpopulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Lemonnier and J. Cartaud for their helpful comments and P. Roux for expert assistance in confocal analysis. This work was supported by European Commission Grant QLG3 CT2000 01625, a grant from the Association Française contre les Myopathies, a grant from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, and Fondo de Investigacion Sanitaria Grant FIS97/0607. F.J.M.-M. was supported by a fellowship from the Ministerio de Educacion, Cultura y Deporte, and S.R. was supported by a fellowship from the Association Française Contre les Myopathies.

Abbreviations

- TTC

C-terminal fragment of tetanus toxin

- NMJ

neuromuscular junction

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

- X-Gal

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside

- AChR

acetylcholine receptor

- BTX

tetramethylrhodamine-labeled α-bungarotoxin

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

References

- 1.Coen L, Osta R, Maury M, Brûlet P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9400–9405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnerot C, Rocancourt D, Briand P, Grimber G, Nicolas J F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6795–6799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costanzo E M, Barry J A, Ribchester R R. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:694–700. doi: 10.1038/76649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jasmin B J, Antony C, Changeux J P, Cartaud J. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:470–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein L S B, Yang Z. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:39–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coen L, Kissa K, Le Mevel S, Brûlet P, Demeneix B A. Int J Dev Biol. 1999;43:823–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzsimonds R M, Poo M M. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:143–170. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao H W, Poo M M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11009–11015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191351698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ralston E, Ploug T, Kalhovde J, Lomo T. J Neurosci. 2001;21:875–883. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00875.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buonanno A, Fields R D. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:110–120. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emsley P, Fotinou C, Black I, Fairweather N F, Charles I G, Watts C, Hewitt E, Isaacs N W. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8889–8894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halpern J L, Neale E A. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;195:221–241. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85173-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herreros J, Lalli G, Montecucco C, Schiavo G. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1941–1950. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herreros J, Lalli G, Schiavo G. Biochem J. 2000;347:199–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinha K, Box M, Lalli G, Schiavo G, Schneider H, Groves M, Siligardi G, Fairweather N. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1041–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duvar S, Peter-Katalinic J, Hanisch F G, Müthing J. Glycobiology. 1997;7:1099–1109. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.8.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müthing J, Maurer U, Sostaric K, Neumann U, Brandt H, Duvar S, Peter-Katalinic J, Weber-Schürholz S. J Biochem. 1994;115:248–256. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson R G W. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:199–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simons K, Toomre D. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:31–40. doi: 10.1038/35036052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smart E J, Graf G A, McNiven M A, Sessa W C, Engelman J A, Scherer P E, Okamoto T, Lisanti M P. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7289–7304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan A A, Bose C, Yam L S, Soloski M J, Rupp F. Science. 2001;292:1681–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.1056594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferns M, Hoch W, Campanelli J T, Rupp F, Hall Z W, Scheller R H. Neuron. 1993;8:1079–1086. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murgia M, Serrano A L, Calabria E, Pallafacchina G, Lomo T, Schiaffino S. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:142–147. doi: 10.1038/35004013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daly C, Sugimori M, Moreira J E, Ziff E B, Llinas R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6120–6125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Camilli P, Takei K. Neuron. 1996;16:481–486. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palfrey H C, Artalejo C R. Neuroscience. 1998;83:969–989. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00453-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schweizer F E, Betz H, Augustine G J. Neuron. 1995;14:689–696. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matteoli M, Verderio C, Rossetto O, Iezzi N, Coco S, Schiavo G, Montecucco C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13310–13315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montesano R, Roth J, Robert A, Orci L. Nature (London) 1982;296:651–653. doi: 10.1038/296651a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parton R G, Ockleford C D, Critchley D R. J Neurochem. 1987;49:1057–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb09994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takei K, Mundigl O, Daniell L, De Camilli P. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1237–1250. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelkmans L, Kartenbeck J, Helenius A. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:473–483. doi: 10.1038/35074539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lencer W I, Hirst T R, Holmes R K. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1999;1450:177–190. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolf A A, Jobling M G, Wimer-Mackin S, Ferguson-Maltzman M, Madara J L, Holmes R K, Lencer W I. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:917–927. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson H A, Chen Y, Norkin L C. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1825–1834. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.11.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]