Abstract

Tentoxin, a natural cyclic tetrapeptide produced by phytopathogenic fungi from the Alternaria species affects the catalytic function of the chloroplast F1-ATPase in certain sensitive species of plants. In this study, we show that the uncompetitive inhibitor tentoxin binds to the αβ-interface of the chloroplast F1-ATPase in a cleft localized at βAsp-83. Most of the binding site is located on the noncatalytic α-subunit. The crystal structure of the tentoxin-inhibited CF1-complex suggests that the inhibitor is hydrogen bonded to Asp-83 in the catalytic β-subunit but forms hydrophobic contacts with residues Ile-63, Leu-65, Val-75, Tyr-237, Leu-238, and Met-274 in the adjacent α-subunit. Except for minor changes around the tentoxin-binding site, the structure of the chloroplast α3β3-core complex is the same as that determined with the native chloroplast ATPase. Tentoxin seems to act by inhibiting inter-subunit contacts at the αβ-interface and by blocking the interconversion of binding sites in the catalytic mechanism.

Tentoxin, a cyclic tetrapeptide {cyclo-[l-MeAla-1-l-Leu-2-MePhe[(Z)Δ]-3-Gly-4]} produced by various phytopathogenic fungi from the Alternaria species, acts as a selective energy transfer inhibitor of the chloroplast F1-ATPase in certain sensitive species of plants but shows no effect on the homologous mitochondrial or bacterial enzymes. In the soluble, isolated CF1-complex, the phytopathogen inhibits ATP hydrolysis, whereas both catalytic reactions, ATP synthesis and hydrolysis, are blocked in the membrane-bound CF1. Binding studies indicate that the inhibition of the ATPase by tentoxin is uncompetitive with nucleotides (1–3) and suggest that the phytopathogen prevents the cooperative release of tightly bound nucleotides from the enzyme (4). However, the precise number and location of the tentoxin-binding site(s) and the mechanism by which the phytopathogen affects the catalytic activity of the chloroplast ATPase are still unknown. Labeling studies suggest at least one high-affinity inhibitory binding site (Kd < 10−8 M), probably located at the αβ-interface, and 1–2 low-affinity binding sites (Kd > 10−6 M), which cause a reactivation of the enzyme (5–6). Analysis of tentoxin-sensitive and -resistant Nicotiana species indicated that residue βAsp-83 located at the interface of the N-terminal β-barrel domains in the α- and β-subunits is crucial for tentoxin binding and/or sensitivity (7). Substitution of this residue by glutamate, alanine, or leucine caused tentoxin resistance (8), whereas substitution of the native glutamate in the tentoxin-resistant Chlamydomonas reinhardtii F1-ATPase by aspartate induced tentoxin sensitivity (9). On the other hand, tentoxin-resistant F1-ATPases from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 and from E. coli (10) contain aspartate in the equivalent position of the β-subunit as well. Hence, additional structural elements in the α- and/or β-subunits are probably required for tentoxin binding and sensitivity in F1-ATPases. More detailed information on these critical residues was obtained from the crystal structure of the native spinach chloroplast F1 (11) and a structural alignment of the catalytic αβ-interfaces of the chloroplast, mitochondrial (12–13) and thermophilic F1-ATPases (14). In contrast to the bacterial and mitochondrial enzymes, the conformation of the αβ-interface in the chloroplast F1 is apparently controlled by residues βAsp-83 and αArg-297, which seems to adjust the binding site to the phytopathogen. Compensation of the positive charge of αArg-297 by interaction with the negative charge of the aspartate carboxyl group might promote tentoxin binding in the chloroplast ATPase as in the tentoxin-resistant mitochondrial and thermophilic enzymes conserved positively charged residues are exposed at the surface of the potential binding cleft. Further analysis of the native CF1-structure suggested that binding of tentoxin to the essential βAsp-83 might be controlled by steric and/or electrostatic restraints caused by residues αAla-96 and αPro-133 (11), which are replaced by bulky hydrophobic or basic residues in resistant species.

In this paper, we describe the precise location of the tentoxin-binding site at the αβ-interface of the chloroplast F1-ATPase, which was determined by x-ray analysis of crystals containing the spinach chloroplast α3β3γɛ-core complexed with tentoxin. In this structure, residues involved in the binding of the inhibitor—and which are, thereby, potential targets for a selective modification to control the tentoxin sensitivity in plants—are unambiguously identified. In addition, the structure of the CF1-tentoxin complex suggests a potential mechanism that explains the inhibition of the chloroplast ATPase by the phytopathogen on the molecular level.

Materials and Methods

Crystallization and Data Collection.

Spinach chloroplast F1-ATPase was isolated by EDTA extraction and anion exchange chromatography from thylakoid membranes as described (11, 15). Subunit δ was removed from the catalytic F1-domain according to (11) and the remaining α3β3γɛ-complex was incubated with 0.05 mM tentoxin in a buffer containing 25 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 0.002% (wt/vol) PMSF, and 0.01% (wt/vol) sodium azide. Crystals of the CF1-tentoxin-inhibitor complex were grown by micro batch in the presence of 1 mM ADP to stabilize the purified protein and were formed after 8–10 weeks. Immediately before data collection on beam line BW7B at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory/Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (EMBL/DESY), crystals were transferred into 2.0 M lithium sulfate. Reflections from flash-frozen crystals were collected to 3.4 Å resolution. Diffraction data were integrated with DENZO (16) and processed further with programs from the CCP4 program suite (17).

Structure Determination and Refinement.

The structure of the CF1-tentoxin inhibitor complex was solved by molecular replacement using the refined coordinates of the native CF1-structure (11) as a search model. Initial rigid-body refinement was carried out for all reflections from 15–5 Å. According to the structure of the native chloroplast F1-complex, three domains in the α- and β-subunits were defined in the rigid-body minimization corresponding to residues α25–96, α97–371, and α372–501, and β19–93, β94–381, and β382–485, respectively. For calculation of the Rfree-value (18), 5% of the observed reflections were set aside and excluded from the entire refinement, including the initial rigid-body minimization. Tentoxin was built into a σ A weighted-difference density map with the graphics program O (19) using structural information of MeSer-1-Tentoxin obtained by NMR-spectroscopy, restrained molecular dynamics simulations (20), and coordinates of dihydrotentoxin [cyclo(l-leucyl-d-methylphenylalanyl-glycyl-l-methylalanyl)] (21–22). To prevent model bias from affecting the limited resolution of the data, a composite omit, cross-validated σ A weighted map was calculated by the program CNS (23), which confirmed the density in the tentoxin-binding site. Further crystallographic refinement was accomplished by positional and temperature-factor refinement using the maximum likelihood target in REFMAC (24). The model was revised at each cycle of the refinement by inspection of the Fo-Fc and 2Fo-Fc maps and by manual rebuilding in o (19). The model converged to a final crystallographic R-factor of 29.6% (Rfree = 31.8%) for reflections from 6–3.4 Å. Model geometry was verified with PROCHECK (25). Figures were produced by using the programs BOBSCRIPT (26) and RASTER3D (27). The structure has been submitted to the Protein Data Bank (PDB accession code 1KMH).

Results and Discussion

Quality of the Structure of the Tentoxin-Inhibited CF1-Complex.

The final model of the CF1-tentoxin complex includes 7,219 atoms. In general, the electron density is well defined. However, several residues in the C-terminal domain are not clearly visible in the electron-density map or display high-temperature factors for their side chain atoms. Hence, alternative conformations of the C-terminal domain (in particular, of the catalytic β-subunit) cannot be completely excluded at the present resolution of the diffraction data. The conformation of the α- and β-subunits in the inhibitor complex is highly similar to the native chloroplast structure (11). The Cα atoms of both structures superimpose well with an rms deviation of 0.44 Å. All residues except βArg-52 and αSer-101 have main chain dihedral angles that fall within the allowed regions of the Ramachandran diagram, as defined by the program PROCHECK (25). The final parameter of refinement and model stereochemistry are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data and refinement statistics

| Measurement | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Resolution, Å | 20.0–3.4 |

| Reflections | 19,747 |

| Completeness, % | 92.5 (79.9) |

| Rmerge | 0.089 (0.383) |

| 〈I/σI〉 | 9.43 (2.51) |

| Space group | R32 |

| Unit cell, Å3 | 146.9 × 146.9 × 381.7 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range, Å | 6.0–3.2 |

| R-factor for 95% data | 0.296 (0.316) |

| Free R-factor for 5% data | 0.318 (0.322) |

| No. of atoms | |

| CF1 | 7189 |

| tentoxin | 30 |

| RMS deviation from ideality | |

| bond lengths, Å | 0.025 |

| bond angles, ° | 1.995 |

The value for the highest resolution bin (3.49–3.40 Å) is given in parentheses.

The Tentoxin-Binding Site at the αβ-Interface.

After initial rigid-body refinement using the native CF1-structure (11) as a starting model, a clear region of positive density was identified in the difference electron-density map at the catalytic αβ-interface slightly below the N-terminal six-stranded β-barrel domain in both subunits. A single tentoxin molecule fitted almost perfectly into this additional density located in the vicinity of βAsp-83 (see Fig. 2 A–D). Further crystallographic refinement revealed no significant differences in main chain or side chain conformations in the final models of the native and the inhibited F1-ATPase besides for residues αLeu-237, αMet-274 and αArg-297, suggesting that the overall structure of the CF1-complex is essentially unchanged by binding of the phytopathogen tentoxin. Hence, tentoxin probably binds to an almost preformed rather than to an induced site in the chloroplast ATPase. The binding site lies in a cleft at the catalytic αβ-interface. The ring of the cyclic tetrapeptide inhibitor binds almost perpendicularly to the αβ-interface, and the inhibitor forms contacts with the α- and the β-subunits (see Fig. 1). These contacts between the phytopathogen and the chloroplast F1-ATPase are predominantly hydrophobic, but the interaction with the inhibitor is probably also controlled by intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Calculation of potential hydrogen bonds in the final model by the program HBPLUS (28) suggests that amide hydrogens N2 (l-Leu-2) and N4 (Gly-4) in the peptide inhibitor and the carboxyl side chain of the essential βAsp-83 are hydrogen bonded. Both hydrogen bonds probably position and align the inhibitor in the correct orientation in the binding cleft. Additional hydrogen bonding between the main chain NH group of Asp-83 and the carbonyl group of Gly-4 in the tentoxin molecule also might contribute to the exact positioning of the phytopathogen in the binding site. Furthermore, the close distance of the side chain NH group of αArg-297 and the main chain carbonyl of l-MeAla-1 (3.2 Å) suggests additional hydrogen bonding between the inhibitor and the α-subunit, although this contact was not indicated by HBPLUS (28). The importance of correct hydrogen bonding for the positioning of the inhibitor in the binding cleft is supported by biochemical and mutagenesis studies that demonstrated that tentoxin binding fails in βAsp-83→Glu mutants or in species that naturally contain glutamate in the position of the essential βAsp-83 (7, 8). Tentoxin resistance might simply result from the changed orientation of the carboxyl group in the binding cleft, which affects the correct hydrogen bonding and the alignment of the inhibitor.

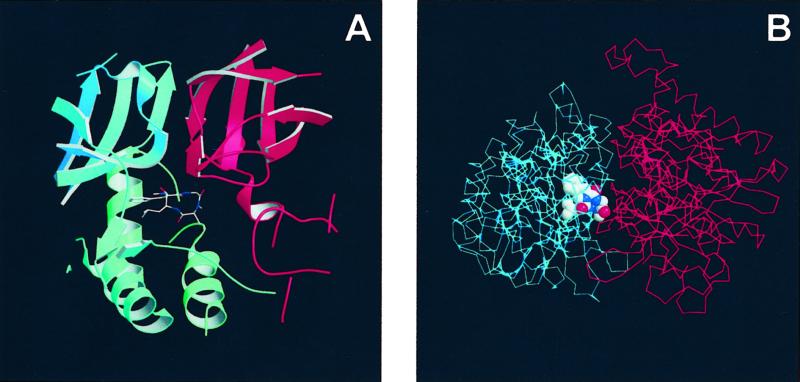

Figure 2.

Location of tentoxin in the crystal structure of the chloroplast F1-ATPase. (A) Ribbon diagram of the structure of the chloroplast α-subunit (blue) and β-subunit (red) at the tentoxin-binding site. The inhibitor is shown in ball-and-stick representation. Both subunits are shown with their 3-fold crystallographic axis in vertical orientation, with the binding site facing the external medium. (B) Schematic representation of the molecular structure of a single chloroplast αβ-pair. The structure is shown from the top as it would appear on the membrane; the 3-fold axis points toward the viewer. The bound inhibitory tentoxin molecule is drawn in cpk mode.

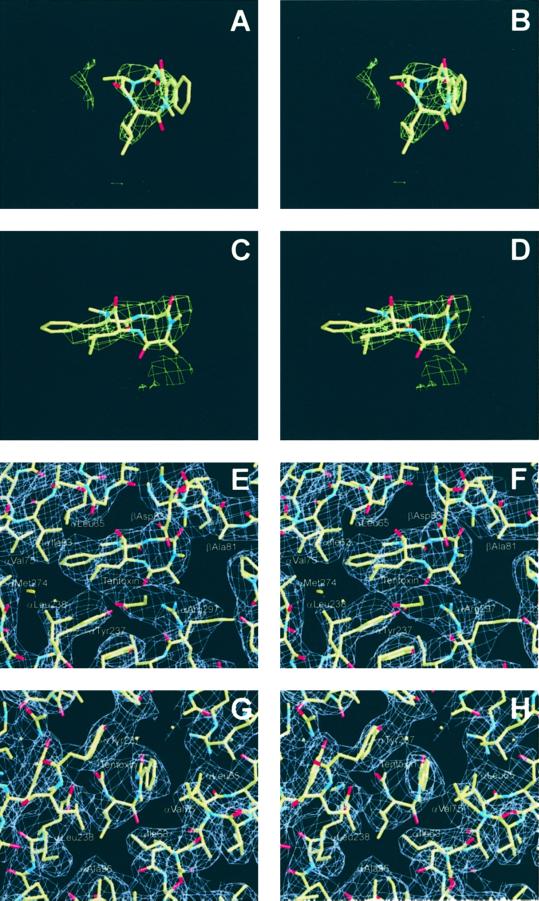

Figure 1.

Stereograms of the tentoxin-binding site in the spinach chloroplast F1. (A–D) Positive-difference electron density at the αβ-interface of the chloroplast ATPase after initial rigid-body refinement of the CF1-tentoxin inhibitor complex at a contour level of 3.0 σ. (E–H) Two orthogonal views of the 3.4 Å resolution final 2Fo-Fc electron-density map of the tentoxin-binding site in the chloroplast F1-structure contoured at 1 σ with the refined coordinates superimposed.

Although hydrogen bonding apparently dominates the interaction with the inhibitor in the β-subunit, the α-subunit forms several important hydrophobic contacts with the hydrophobic residues l-Leu-2 and MePhe-3 in the tentoxin molecule. Close contacts exist between the strictly conserved residues αLeu-65−MePhe-3 (2.9 Å), αVal-75−MePhe-3 (3.8 Å), αLeu-238−l-Leu-2 (3.7 Å). Residue αIle-63, which is replaced by the polar methionine in some resistant species, intercalates between the two hydrophobic side chains in the tentoxin molecule [αIle-63−l-Leu-2 (3.9 Å), αIle-63−MePhe-3 (4.3 Å)]. Residue αMet-274 is close to the aromatic ring of MePhe-3 (3.5 Å), which also forms a staggered stacking interaction with αTyr-237.

Another important residue controlling the binding of the inhibitor in the α-subunit is Pro-133, which is substituted by bulky hydrophobic or bulky basic residues in resistant species. Superposition of the tentoxin-resistant mitochondrial or thermophilic α-subunit with the CF1-tentoxin complex suggests that these residues block access to the binding site and thereby confer tentoxin sensitivity to the F1-complex. Superposition of the β-subunits indicates a critical role of βAla-81 in the tentoxin-binding site, which seems to form hydrophobic contacts with the methyl residue of l-MeAla-1 (3.3 Å). In the resistant EF1- and TF1-complexes, substitution of alanine by serine seems to affect this hydrophobic contact and, more essentially, the critical hydrogen bonding of βAsp-83 and tentoxin because of the side chain hydrogen bond formed between Ser-81 and Asp-83. Based on a sequence alignment of resistant and sensitive species, a critical role for tentoxin binding and sensitivity also was suggested for residue αAla-96 (11). Indeed, the structure of the CF1-tentoxin complex presented in this study demonstrates that substitution of this residue by larger side chains like methionine (TF1), valine (MF1), or leucine (EF1) in resistant species might cause steric conflicts with l-Leu-2 in the tentoxin molecule which disturb the binding of the inhibitor to the F1-complex.

Structure of Tentoxin.

In aqueous solution, tentoxin exists in at least four interconverting conformers of 51% (A), 37% (B), 8% (C), and 4% (D) (29). The two major forms differ in the position of the peptide bond formed between MeAla-1 and Leu-2, which is flipped in the B-conformer. A shift in the equilibrium of the A- and B-conformers was reported for the MeSer-1 derivate of tentoxin, where, because of an intramolecular hydrogen bond, the B-conformer becomes the predominant form in aqueous solution (20). The crystallographic data of our inhibitor complex suggest that the B-conformer is the bound species in the tentoxin-inhibited chloroplast F1-ATPase. Structure refinement with the A-conformer resulted in a final model with increased R- and Rfree-factors and impaired model geometry. Moreover, neither the electron density of the initial nor the density map of the final model showed any evidence that the A-form of tentoxin is bound at the αβ-interface of the chloroplast F1-complex.

Mechanism of Inhibition.

The crystal structure of the CF1-tentoxin complex suggests a speculative molecular mechanism by which the phytopathogen inhibits the chloroplast F1-ATPase. In contrast to the structure of the native CF1-complex which is thought to represent a latent, inactive form of the chloroplast enzyme (11), the contact between αArg-297 and βAsp-83 at the αβ-interface is blocked by the tentoxin molecule in the inhibited complex. The phytopathogen intercalates between both residues and forms potential hydrogen bonds with their side chains. In this manner, tentoxin restrains any conformational changes at the catalytic interface that involve a relative movement of these residues. However, significant changes in the distance and the relative orientation of the conserved, equivalent αArg-304 and βGlu-67 exist in the native MF1-structure (12). Considering the entire α- and β-subunits as a rigid group, a superposition of the Cα-atoms of the different conformers in the mitochondrial F1 indicates tilting in the catalytic β-subunit that involves αArg-304-βGlu-67 when the subunit shifts from the closed to the open state in the catalytic cycle (see Fig. 3). The crystal structure of the CF1-tentoxin complex suggests that the inhibitor arrests the catalytic αβ-interface in the closed conformation and thereby prevents the sequential interconversion of the nucleotide binding sites between the βDP (tight), βTP (loose), and βE (open) states (12, 30, 31). Blocking of a single αβ-interface seems sufficient to inhibit the cyclic interconversion of binding sites in multisite catalysis, which corresponds to results obtained in kinetic and labeling experiments (5). In agreement with the suggested mechanism, unisite catalysis is not affected (32). The inhibitory mechanism of tentoxin on the chloroplast F1-ATPase resembles the inhibition of the mitochondrial enzyme by aurovertin (33). However, in contrast to tentoxin, which seems to inhibit the transformation of the catalytic interface into the open conformation, aurovertin prevents closure of the αβ-interfaces in the catalytic mechanism. Nevertheless, both inhibitors show the same result on multisite catalysis as they block the cyclic interconversion of nucleotide binding sites.

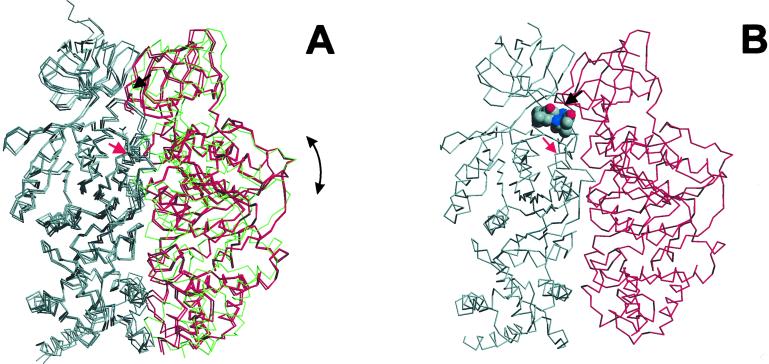

Figure 3.

Comparison of different conformational states of the bovine mitochondrial α- and β-subunits to the chloroplast αβ-complex containing tentoxin. (A) Schematic representation of the peptide backbone of three different conformations of the mitochondrial α- and β-subunits that represent different states of the catalytic cycle (12, 30). Both subunits were superimposed on their Cα-atoms. The αE, αDP, and αTP states of the noncatalytic α-subunit is shown in gray, the closed conformation of the catalytic β-subunit (βDP and βTP) is drawn in red, and the open βE state is coloured in green. Positions of residues αArg-304 and βGlu-67, equivalent to residues αArg-297 and βAsp-83 that are arrested by the tentoxin molecule in the chloroplast structure (B), are indicated by red and black arrows, respectively. As indicated by the arrow on the right (A), a shift form the closed to the open conformation of the catalytic β-subunit which occurs during the catalytic cycle is associated with a domain movement that involves the αβ-interface at αArg-304-βGlu-67.

Reactivation of the Chloroplast ATPase by Tentoxin.

Binding of tentoxin to a low-affinity site on the chloroplast F1-complex releases the inhibitory effect caused by high-affinity binding to the αβ-interface and stimulates the ATPase activity of the enzyme (5–6). This stimulatory, low-affinity binding site, however, was not resolved in our structure of the CF1-tentoxin complex, maybe because of the low occupancy of the nucleotide binding sites in the crystal, as kinetic studies have shown that binding to the stimulatory tentoxin site critically depends on the presence of bound nucleotides on the F1-ATPase (5). Thus, the precise location of the stimulatory tentoxin site and the reactivation mechanism of tentoxin remain still unknown, and additional structural information as well as functional studies seem necessary to solve this issue.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Büchner and C. Schnick for critical reading of the manuscript and N. Körtgen for technical assistance. We thank Prof. H. Strotmann for helpful comments on the manuscript and valuable suggestions. We thank the staff at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) Outstation for support. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Gr1616/4–1) and the European Community/Access to Research Infrastructure Action of the Improving Human Potential Program Contract HPRI-CT-1999–00017 at the EMBL Hamburg Outstation.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID code 1KMH).

References

- 1.Arntzen C J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;283:539–542. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steele J A, Uchytil T F, Durbin R D, Bhatnagar P, Rich D H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:2245–2248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steele J A, Durbin R D, Uchytil T F, Rich D H. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;501:72–82. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(78)90096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu N, Mills D A, Huchzermeyer B, Richter M L. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8536–8540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santolini J, Hauraux F, Sigalat C, Moal G, André F. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:849–858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mochimaru M, Sakurai H. FEBS Lett. 1997;419:23–26. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avni A, Anderson J D, Holland N, Rochaix J-D, Gromet-Elhanan Z, Edelmann M. Science. 1992;257:1245–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1387730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker W C, Du Z, Hein R, Richter M L, Gromet-Elhanan Z. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:906–912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu D, Fiedler H R, Golan T, Edelmann M, Strotmann H, Shavit N, Leu S. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5457–5463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, Spies A, Hein R, Zhou X, Thomas B C, Richter M L, Gegenheimer P. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17124–17132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groth G, Pohl E. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1345–1352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrahams J P, Leslie A G W, Lutter R, Walker J E. Nature (London) 1994;370:621–628. doi: 10.1038/370621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bianchet M A, Hullihen J, Pedersen P L, Amzel L M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11065–11070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirakahara Y, Leslie A G W, Abrahams J P, Walker J E, Ueda T, Sekimoto Y, Kambara M, Saika K, Kagawa Y, Yoshida M. Structure (London) 1997;5:825–836. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groth G, Schirwitz K. Eur J Biochem. 1999;260:15–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brünger A T. Nature (London) 1992;335:472–475. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones T A, Zhou J Y, Cowan S W, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinet E, Cavelier F, Verducci J, Girault G, Dubart L, Haraux F, Sigalat C, Andre F. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12804–12811. doi: 10.1021/bi960955n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer W L, Kuyper L F, Phelps D W, Cordes A W. Chem. Commun. 1974. , 339. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swepston P N, Cordes A W, Kuyper L F, Meyer W L. Acta Crystallogr B. 1981;37:1139. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brünger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, Delano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges N, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murshudov G N, Lebedev A, Vagin A A, Wilson K S, Dodson E J. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:247–255. doi: 10.1107/S090744499801405X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laskowski R A, MacArthur M W, Moss D S, Thornton J M. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esnouf R M. J Mol Graph Modell. 1997;15:132–134. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(97)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merritt E A, Bacon D J. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:505–524. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald I K, Thornton J M. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:777–793. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinet E, Neumann J-M, Dahse I, Girault G, Andre F. Biopolymers. 1995;36:135–152. doi: 10.1002/bip.360360204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyer P D. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1140:215–240. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90063-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menz R I, Walker J E, Leslie A G W. Cell. 2001;106:331–341. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fromme P, Dahse I, Gräber P. Z Naturforsch, C. 1992;47:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Raaij M J, Abrahams P, Leslie A G W, Walker J E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6913–6917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]