Abstract

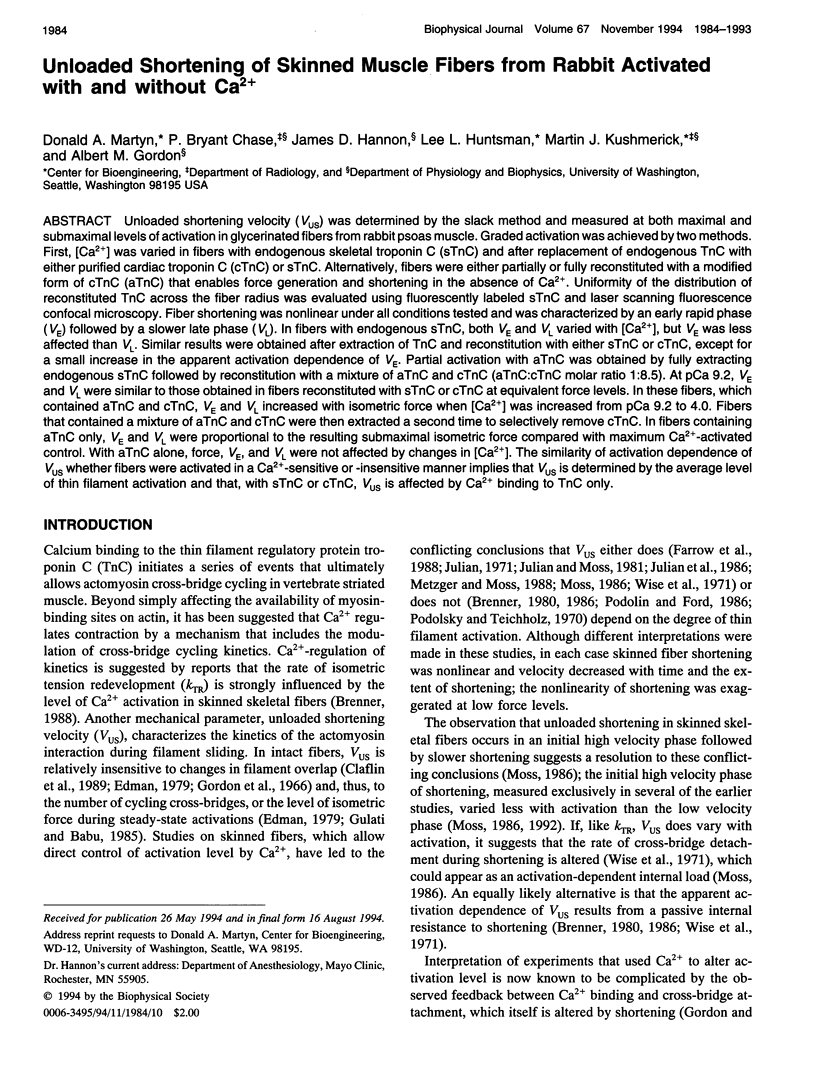

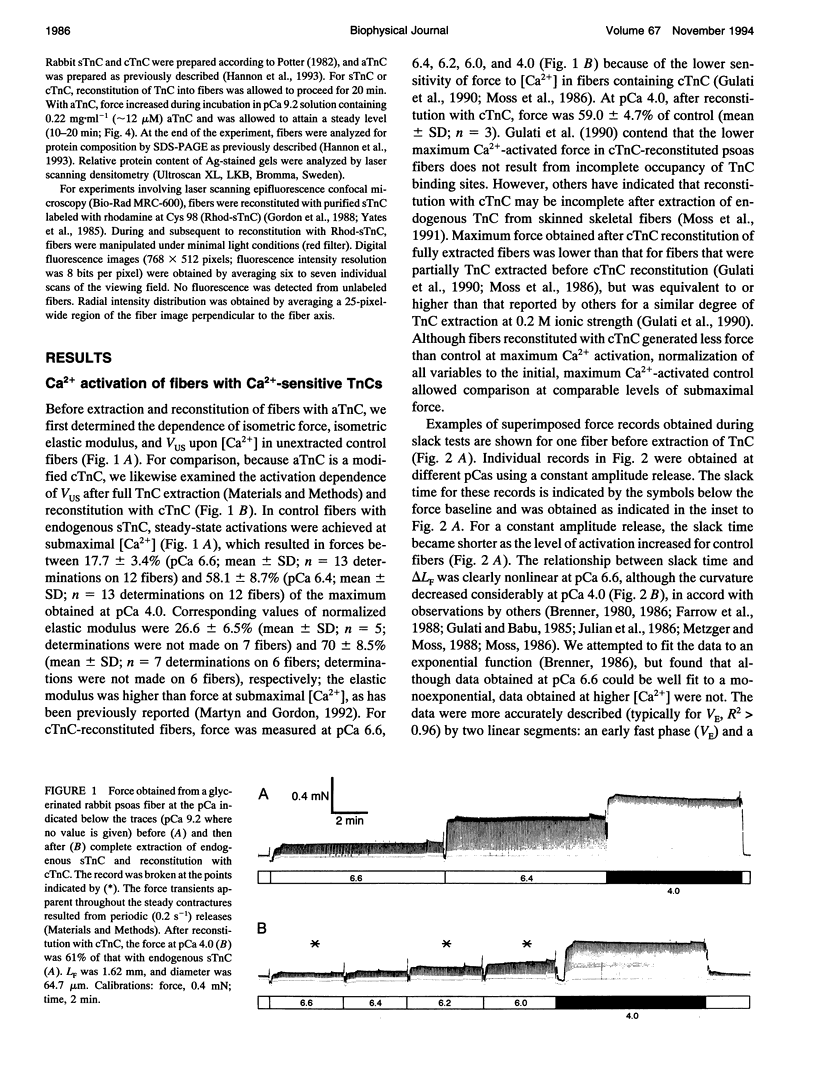

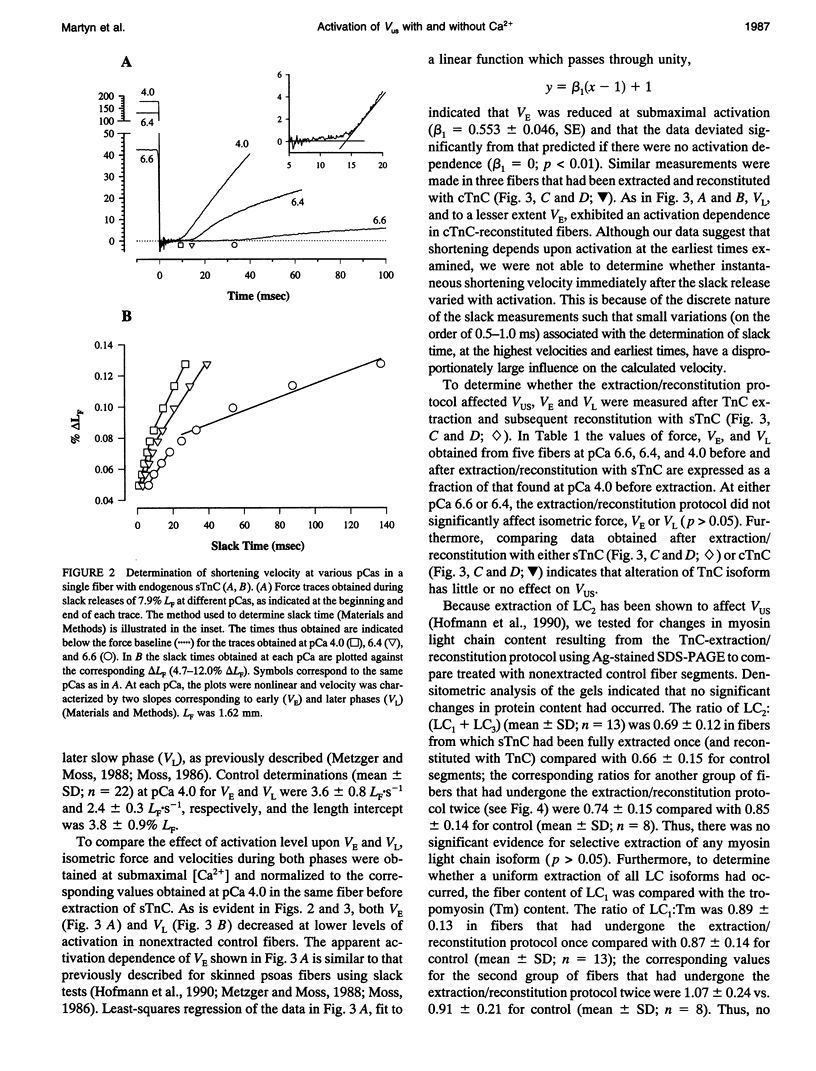

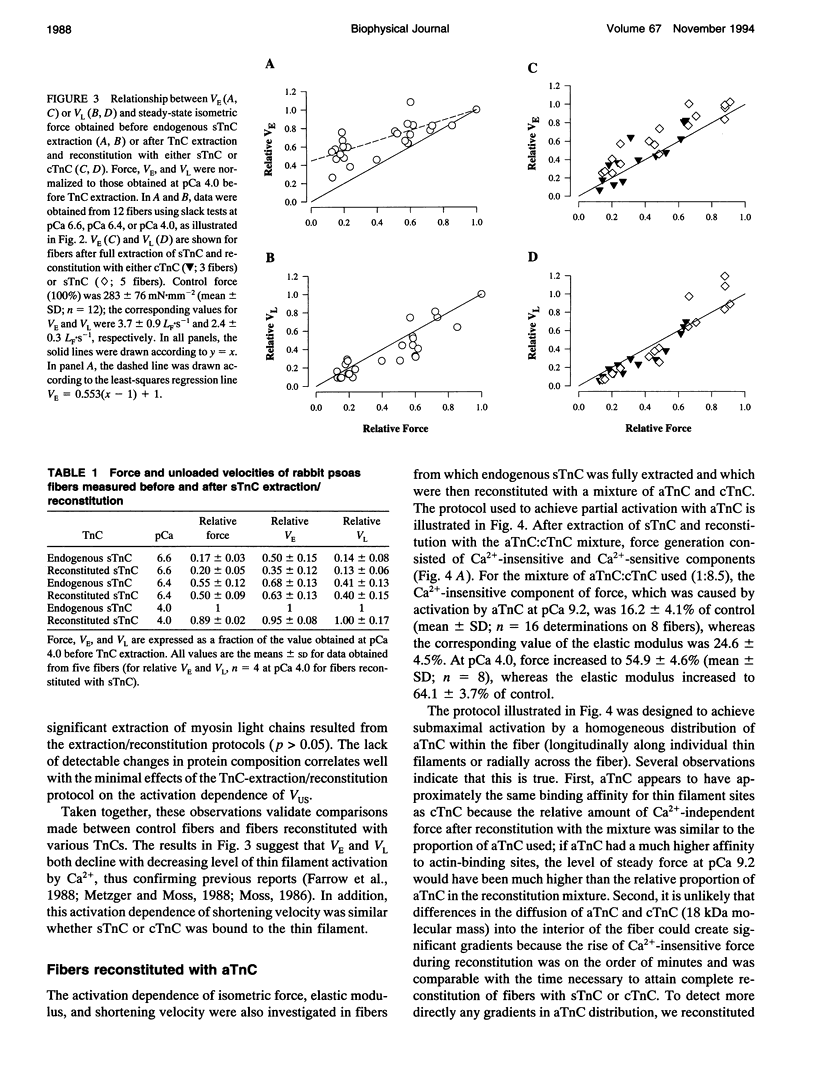

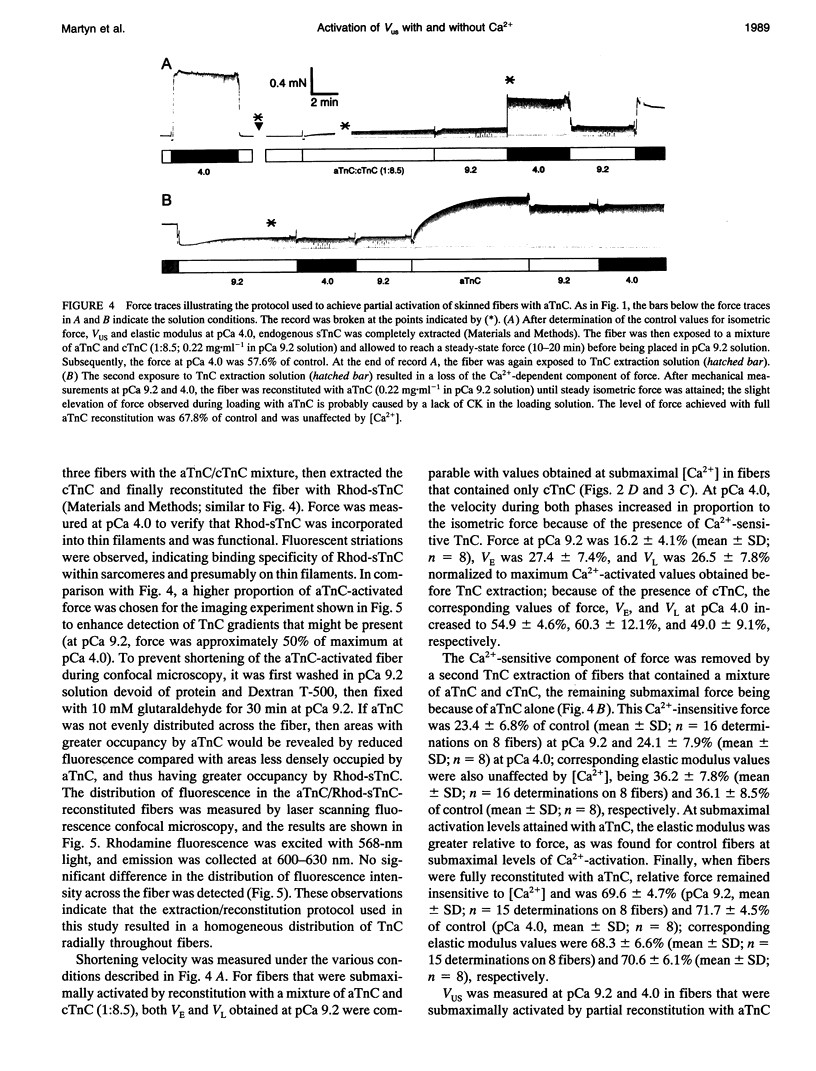

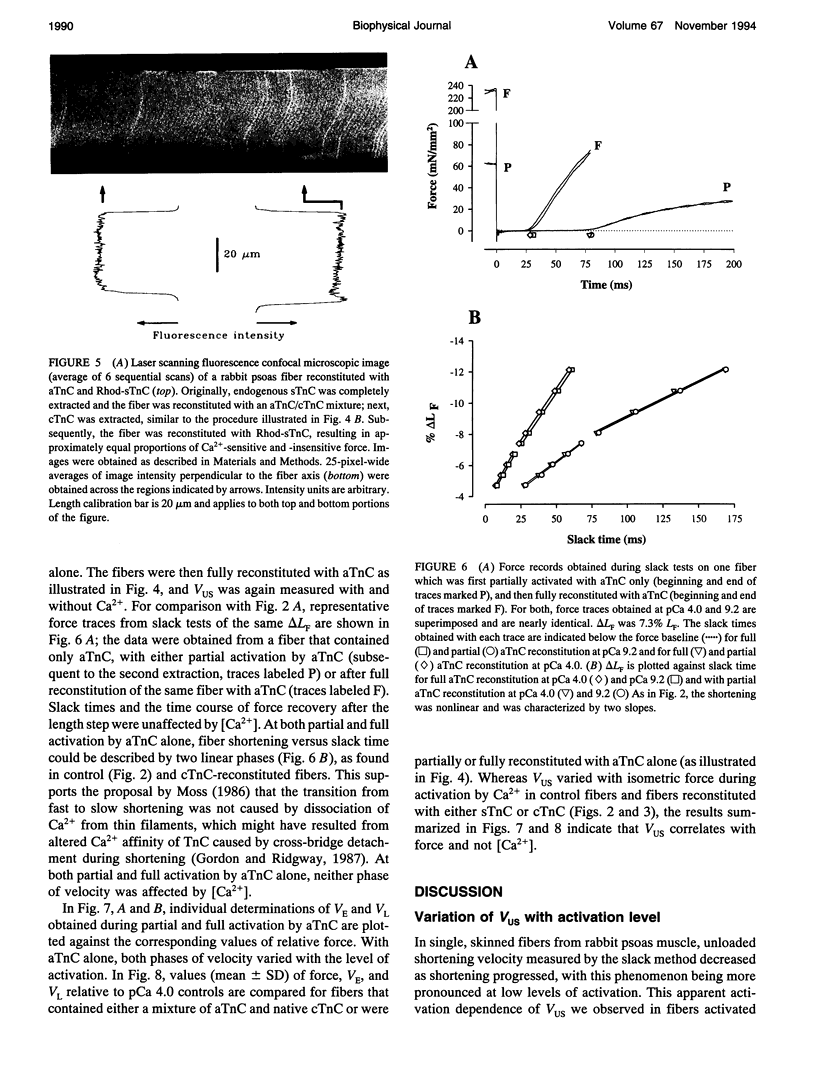

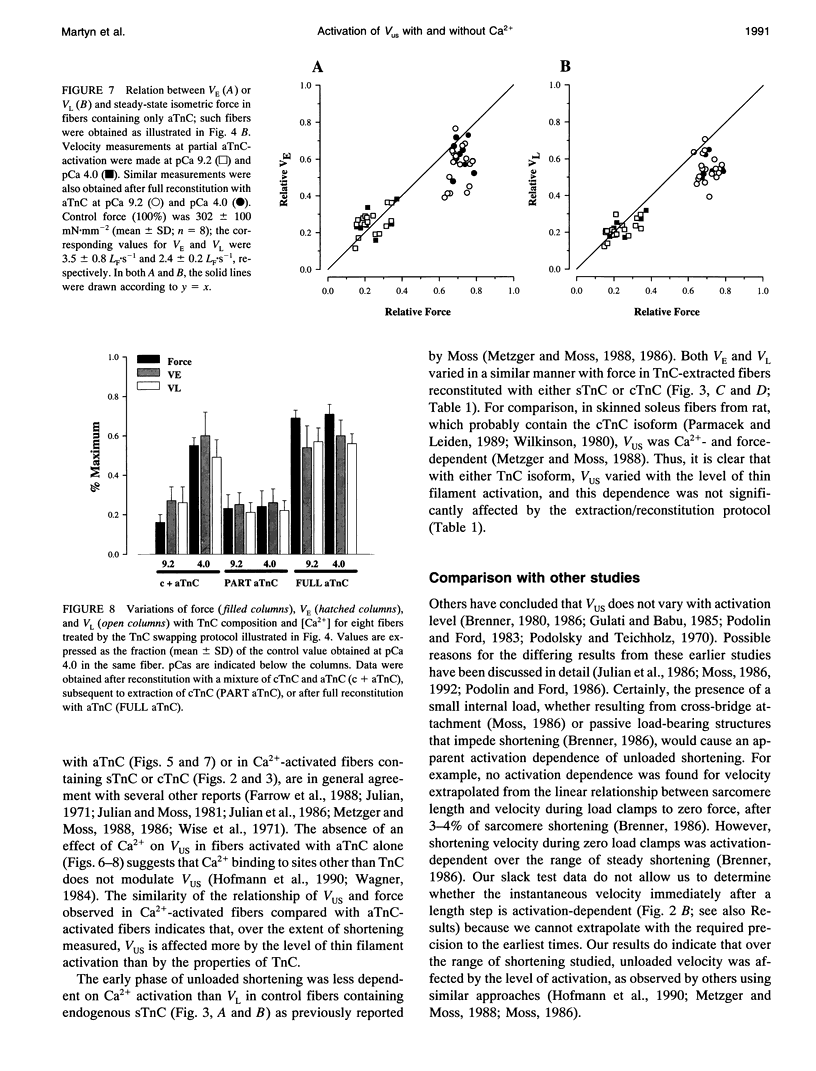

Unloaded shortening velocity (VUS) was determined by the slack method and measured at both maximal and submaximal levels of activation in glycerinated fibers from rabbit psoas muscle. Graded activation was achieved by two methods. First, [Ca2+] was varied in fibers with endogenous skeletal troponin C (sTnC) and after replacement of endogenous TnC with either purified cardiac troponin C (cTnC) or sTnC. Alternatively, fibers were either partially or fully reconstituted with a modified form of cTnC (aTnC) that enables force generation and shortening in the absence of Ca2+. Uniformity of the distribution of reconstituted TnC across the fiber radius was evaluated using fluorescently labeled sTnC and laser scanning fluorescence confocal microscopy. Fiber shortening was nonlinear under all conditions tested and was characterized by an early rapid phase (VE) followed by a slower late phase (VL). In fibers with endogenous sTnC, both VE and VL varied with [Ca2+], but VE was less affected than VL. Similar results were obtained after extraction of TnC and reconstitution with either sTnC or cTnC, except for a small increase in the apparent activation dependence of VE. Partial activation with aTnC was obtained by fully extracting endogenous sTnC followed by reconstitution with a mixture of aTnC and cTnC (aTnC:cTnC molar ratio 1:8.5). At pCa 9.2, VE and VL were similar to those obtained in fibers reconstituted with sTnC or cTnC at equivalent force levels. In these fibers, which contained aTnC and cTnC, VE and VL increased with isometric force when [Ca2+] was increased from pCa 9.2 to 4.0. Fibers that contained a mixture of a TnC and cTnC were then extracted a second time to selectively remove cTnC. In fibers containing aTnC only, VE and VL were proportional to the resulting submaximal isometric force compared with maximum Ca(2+)-activated control. With aTnC alone, force, VE, and VL were not affected by changes in [Ca2+]. The similarity of activation dependence of VUS whether fibers were activated in a Ca(2+)-sensitive or -insensitive manners implies that VUS is determined by the average level of thin filament activation and that, with sTnC or cTnC, VUS is affected by Ca2+ binding to TnC only.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brenner B. Effect of Ca2+ on cross-bridge turnover kinetics in skinned single rabbit psoas fibers: implications for regulation of muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 May;85(9):3265–3269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. Technique for stabilizing the striation pattern in maximally calcium-activated skinned rabbit psoas fibers. Biophys J. 1983 Jan;41(1):99–102. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84411-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. The necessity of using two parameters to describe isotonic shortening velocity of muscle tissues: the effect of various interventions upon initial shortening velocity (vi) and curvature (b). Basic Res Cardiol. 1986 Jan-Feb;81(1):54–69. doi: 10.1007/BF01907427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B., Yu L. C. Equatorial x-ray diffraction from single skinned rabbit psoas fibers at various degrees of activation. Changes in intensities and lattice spacing. Biophys J. 1985 Nov;48(5):829–834. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83841-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartoux L., Chen T., DasGupta G., Chase P. B., Kushmerick M. J., Reisler E. Antibody and peptide probes of interactions between the SH1-SH2 region of myosin subfragment 1 and actin's N-terminus. Biochemistry. 1992 Nov 10;31(44):10929–10935. doi: 10.1021/bi00159a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase P. B., Beck T. W., Bursell J., Kushmerick M. J. Molecular charge dominates the inhibition of actomyosin in skinned muscle fibers by SH1 peptides. Biophys J. 1991 Aug;60(2):352–359. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82060-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase P. B., Kushmerick M. J. Effects of pH on contraction of rabbit fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1988 Jun;53(6):935–946. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase P. B., Martyn D. A., Kushmerick M. J., Gordon A. M. Effects of inorganic phosphate analogues on stiffness and unloaded shortening of skinned muscle fibres from rabbit. J Physiol. 1993 Jan;460:231–246. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claflin D. R., Morgan D. L., Julian F. J. Effects of passive tension on unloaded shortening speed of frog single muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1989 Nov;56(5):967–977. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82742-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R., Bialek W. Contraction of glycerinated muscle fibers as a function of the ATP concentration. Biophys J. 1979 Nov;28(2):241–258. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85174-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R., Pate E. The effects of ADP and phosphate on the contraction of muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1985 Nov;48(5):789–798. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83837-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. A., Comte M., Stein E. A. Calmodulin-free skeletal-muscle troponin C prepared in the absence of urea. Biochem J. 1981 Apr 1;195(1):205–211. doi: 10.1042/bj1950205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman K. A. The velocity of unloaded shortening and its relation to sarcomere length and isometric force in vertebrate muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1979 Jun;291:143–159. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow A. J., Rossmanith G. H., Unsworth J. The role of calcium ions in the activation of rabbit psoas muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1988 Jun;9(3):261–274. doi: 10.1007/BF01773896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenczi M. A., Goldman Y. E., Simmons R. M. The dependence of force and shortening velocity on substrate concentration in skinned muscle fibres from Rana temporaria. J Physiol. 1984 May;350:519–543. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford L. E., Huxley A. F., Simmons R. M. The relation between stiffness and filament overlap in stimulated frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1981 Feb;311:219–249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. M., Huxley A. F., Julian F. J. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1966 May;184(1):170–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. M., Ridgway E. B. Extra calcium on shortening in barnacle muscle. Is the decrease in calcium binding related to decreased cross-bridge attachment, force, or length? J Gen Physiol. 1987 Sep;90(3):321–340. doi: 10.1085/jgp.90.3.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. M., Ridgway E. B., Yates L. D., Allen T. Muscle cross-bridge attachment: effects on calcium binding and calcium activation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;226:89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati J., Babu A. Contraction kinetics of intact and skinned frog muscle fibers and degree of activation. Effects of intracellular Ca2+ on unloaded shortening. J Gen Physiol. 1985 Oct;86(4):479–500. doi: 10.1085/jgp.86.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati J., Sonnenblick E., Babu A. The role of troponin C in the length dependence of Ca(2+)-sensitive force of mammalian skeletal and cardiac muscles. J Physiol. 1991 Sep;441:305–324. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUXLEY A. F. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog Biophys Biophys Chem. 1957;7:255–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon J. D., Chase P. B., Martyn D. A., Huntsman L. L., Kushmerick M. J., Gordon A. M. Calcium-independent activation of skeletal muscle fibers by a modified form of cardiac troponin C. Biophys J. 1993 May;64(5):1632–1637. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81517-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann P. A., Metzger J. M., Greaser M. L., Moss R. L. Effects of partial extraction of light chain 2 on the Ca2+ sensitivities of isometric tension, stiffness, and velocity of shortening in skinned skeletal muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1990 Mar;95(3):477–498. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian F. J., Moss R. L. Effects of calcium and ionic strength on shortening velocity and tension development in frog skinned muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1981 Feb;311:179–199. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian F. J., Rome L. C., Stephenson D. G., Striz S. The influence of free calcium on the maximum speed of shortening in skinned frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1986 Nov;380:257–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian F. J. The effect of calcium on the force-velocity relation of briefly glycerinated frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1971 Oct;218(1):117–145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn D. A., Gordon A. M. Force and stiffness in glycerinated rabbit psoas fibers. Effects of calcium and elevated phosphate. J Gen Physiol. 1992 May;99(5):795–816. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.5.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn D. A., Gordon A. M. Length and myofilament spacing-dependent changes in calcium sensitivity of skeletal fibres: effects of pH and ionic strength. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1988 Oct;9(5):428–445. doi: 10.1007/BF01774069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara I., Umazume Y., Yagi N. Lateral filamentary spacing in chemically skinned murine muscles during contraction. J Physiol. 1985 Mar;360:135–148. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger J. M., Greaser M. L., Moss R. L. Variations in cross-bridge attachment rate and tension with phosphorylation of myosin in mammalian skinned skeletal muscle fibers. Implications for twitch potentiation in intact muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1989 May;93(5):855–883. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.5.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger J. M., Moss R. L. Shortening velocity in skinned single muscle fibers. Influence of filament lattice spacing. Biophys J. 1987 Jul;52(1):127–131. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83197-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger J. M., Moss R. L. Thin filament regulation of shortening velocity in rat skinned skeletal muscle: effects of osmotic compression. J Physiol. 1988 Apr;398:165–175. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss R. L. Ca2+ regulation of mechanical properties of striated muscle. Mechanistic studies using extraction and replacement of regulatory proteins. Circ Res. 1992 May;70(5):865–884. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.5.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss R. L. Effects on shortening velocity of rabbit skeletal muscle due to variations in the level of thin-filament activation. J Physiol. 1986 Aug;377:487–505. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss R. L., Lauer M. R., Giulian G. G., Greaser M. L. Altered Ca2+ dependence of tension development in skinned skeletal muscle fibers following modification of troponin by partial substitution with cardiac troponin C. J Biol Chem. 1986 May 5;261(13):6096–6099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss R. L., Nwoye L. O., Greaser M. L. Substitution of cardiac troponin C into rabbit muscle does not alter the length dependence of Ca2+ sensitivity of tension. J Physiol. 1991;440:273–289. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmacek M. S., Leiden J. M. Structure and expression of the murine slow/cardiac troponin C gene. J Biol Chem. 1989 Aug 5;264(22):13217–13225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate E., Cooke R. Addition of phosphate to active muscle fibers probes actomyosin states within the powerstroke. Pflugers Arch. 1989 May;414(1):73–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00585629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolin R. A., Ford L. E. Influence of partial activation on force-velocity properties of frog skinned muscle fibers in millimolar magnesium ion. J Gen Physiol. 1986 Apr;87(4):607–631. doi: 10.1085/jgp.87.4.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolin R. A., Ford L. E. The influence of calcium on shortening velocity of skinned frog muscle cells. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1983 Jun;4(3):263–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00711996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky R. J., Teichholz L. E. The relation between calcium and contraction kinetics in skinned muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1970 Nov;211(1):19–35. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter J. D. Preparation of troponin and its subunits. Methods Enzymol. 1982;85(Pt B):241–263. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)85024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putkey J. A., Dotson D. G., Mouawad P. Formation of inter- and intramolecular disulfide bonds can activate cardiac troponin C. J Biol Chem. 1993 Apr 5;268(10):6827–6830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney H. L., Corteselli S. A., Kushmerick M. J. Measurements on permeabilized skeletal muscle fibers during continuous activation. Am J Physiol. 1987 May;252(5 Pt 1):C575–C580. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.252.5.C575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner P. D. Effect of skeletal muscle myosin light chain 2 on the Ca2+-sensitive interaction of myosin and heavy meromyosin with regulated actin. Biochemistry. 1984 Dec 4;23(25):5950–5956. doi: 10.1021/bi00320a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerblad H., Lee J. A., Lamb A. G., Bolsover S. R., Allen D. G. Spatial gradients of intracellular calcium in skeletal muscle during fatigue. Pflugers Arch. 1990 Mar;415(6):734–740. doi: 10.1007/BF02584013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson J. M. Troponin C from rabbit slow skeletal and cardiac muscle is the product of a single gene. Eur J Biochem. 1980 Jan;103(1):179–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise R. M., Rondinone J. F., Briggs F. N. Effect of calcium on force-velocity characteristics of glycerinated skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1971 Oct;221(4):973–979. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.221.4.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]