Abstract

Owing to the ready formation of an insulating oxide layer, there is an intrinsic obstacle to the use of aluminum material as the cathode in the electrocatalytic reaction. In this report, a new Al-based material with a surface aluminum oxide/chloride nanolayer (nAlClO@Al) is prepared. Via the quantum tunneling effect, this material realizes conductivity through the nano-Al–O layer. This material exhibits unusual inertness toward the hydrogen evolution reaction, leaving a wide reduction window for the substrate. Primed with the native Lewis acidity of the Al–Cl structure, this material achieves the electrocatalytic hydrogenation of thiophenes with up to >95% conversion, >95% selectivity, and 90% Faraday efficiency. This catalysis is applicable to heteroarene and benzene rings. In particular, the chemoselectivity is controlled by the nAlClO@Al catalyst instead of the substrate, which is complementary to electrochemical Birch chemistry.

Introduction

The catalytic hydrogenation is one of the most important reactions of academic research and industrial production. For example, homogeneous asymmetric hydrogenation produces numerous chiral compounds, − and heterogeneous hydrogenation converts bulky chemicals into value-added products. − The catalytic hydrogenation of planar arenes is an important reaction producing complex 3D cyclic alkanes, − serving as fundamental feedstocks for chemistry and chemical engineering. − Especially, cyclic thioether, the product from the hydrogenation of thiophene, is a basic ring motif in natural and artificial substances with diverse applications (Scheme a). − On the other hand, the hydrogenation of arenes, in particular for thiophene, typically requires demanding conditions (Scheme b). For example, when a transition metal catalyst is applied, the hydrogenation at medium to high pressure is necessary, and frequently at elevated temperature. − If acid is applied to activate the thiophene, stoichiometric or even solvent-level dosage is required. , In addition, the product thioether is able to deactivate the catalyst via sulfur–metal coordination, and the C–S bond with a bond dissociation energy of 74 kcal mol–1 could undergo cleavage during hydrogenation. , These harsh conditions have considerably limited the downstream applications of 4H-thiophene. Therefore, a novel catalyst and new synthetic method are desired for this task under mild conditions.

1. Factors for Hydrogenation of Thiophene and Electrocatalyst Design.

Recently, electrochemistry has gradually grown into a powerful and efficient approach in synthetic chemistry. − Electrochemical reduction has emerged as a promising alternative approach for hydrogenation. , For instance, the electrochemical Birch reduction of arenes using an inert electrode achieved seminal advances recently. − Another fundamental progress is emerging using an electrode primed with a transition metal catalyst to achieve electrocatalytic hydrogenation. − On the other hand, the potential power of aluminum-based main-group catalysts has not been unlocked for electrocatalytic hydrogenation. The main challenge is the deactivation of aluminum by the formation of a condensed and insulating Al2O3 layer on the surface (Scheme c), which prevents the electron transfer. Inspired by the quantum tunneling effect at nanoscale electrochemistry, − we hypothesize that the exquisitely fabricated aluminum oxide nanolayer could be a surrogate to this key obstacle. In addition, the integration of Lewis acidity, for example, Al–Cl functionality, onto the nanolayer could activate the substrate via catalysis.

With this rationale, herein, we report electrocatalytic hydrogenation with a conductive aluminum-based oxide/chloride nanolayer (nAlClO@Al) as the electrocatalyst for the first time. This Lewis acid-primed aluminum oxide nanolayer catalyst brings a high Faraday efficiency for the electrocatalytic hydrogenation of a series of thiophenes and other (hetero)aromatic rings with ammonia as the hydrogen source at ambient conditions and can invoke the control of the chemoselectivity by the catalyst via a pathway complementary to Birch reduction.

Results and Discussion

Material Construction

nAlClO@Al was prepared by treating a commercially available Al plate with anodic modification in 2 M hydrochloric acid with graphite felt (GF) as the cathode (Figure a, see Supporting Information, Section 2.1, for details). The reproducibility of this procedure was verified with a sensitivity assessment, which showed that the suitable concentration of HCl is a key factor for reproducibility, and the excess of other parameters did not impact the outcome significantly (Figure b; Supporting Information, Table S2 and Figures S1–S4). , X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis showed the signal of nAlClO@Al was similar to 5052-Al (Al-coated with an Al2O3 film of 3 μm thickness) and distinct from metallic Al, indicating the formation of a thin aluminum oxide layer at the surface of nAlClO@Al (Figure c). Furthermore, the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was employed to measure the precise constitution of the nAlClO@Al surface. As shown in Figure d, the peak at 71.7 eV (Al 2p metal) disappeared after modification, and the Al 2p oxide state at 74.3 eV was predominant. These results suggested that the surficial metallic aluminum was almost totally transformed into an aluminum oxide layer with this electric modification at the limit of detection. Next, the thickness of nAlClO@Al was investigated with the XPS depth profile analysis (Figure e, Supporting Information, Figure S5). The signal of Al (71.7 eV, Al 2p metal) was almost muted at the surface, started to appear when the depth reached 2 nm, and was constant after 6 nm. This result implied that the aluminum oxide structure of nAlClO@Al was a nanolayer about 2–6 nm that was thin enough for quantum tunneling of electrons to ensure the electrical conductivity. For verification, nAlClO@Al and Al materials with Al2O3 surfaces of approximately 65 nm, 130 nm, 185 nm, , and 3 μm in thickness were subjected to Kelvin (4-wire) resistance measurements. The aluminum oxide nanolayer of nAlClO@Al had a 100–143 mΩ resistance, and the other Al2O3 layers were insulating in the Kelvin meter range (Supporting Information, Figure S6 and Table S3). The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images revealed that the nAlClO@Al surface was porous 3D network-like (Figure f). Transmission electron spectroscopy (TEM) showed a stacked-lump morphology of the unit. These multitudinous units constituted the porous 3D network-like surface of the nAlClO@Al material (Supporting Information, Figure S7). In comparison, the metals Al and 5052-Al exhibited a condensed planar structure (Supporting Information, Figure S8). Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis provided an elemental mapping for nAlClO@Al. Besides Al and O, Cl is found to be distributed on average on the surface (Figure g), suggesting the existence of Al–Cl, which can bring Lewis acidity to the nanolayer.

1.

The preparation, morphological, and structural characterization of the cathode material nAlClO@Al. (a) The illustration of the preparation of nAlClO@Al. (b) The sensitivity assessment of the formation of the catalyst. (c) The XRD pattern of nAlClO@Al and other Al materials. (d) The XPS spectra of the Al2p orbital of nAlClO@Al and Al. (e) XPS depth profile analysis in the Al2p region for the nAlClO@Al material. (f) The SEM and TEM images of nAlClO@Al. (g) The EDS-mapping images showing the distribution of Al, O, and Cl.

Reaction Discovery

To evaluate these Lewis acid-primed nano-aluminum oxide materials, thiophene 1a, a compound highly inert toward transition-metal-catalyzed hydrogenation (Scheme a), was chosen as the model substrate to benchmark electrocatalytic hydrogenation. It was found that the electrocatalytic hydrogenation of 1a was successfully achieved with nAlClO@Al as the optimum cathode in an undivided cell (Scheme b, standard conditions). The reaction could finish in 2.14 h (4 F/mol) with >95% conversion and >95% selectivity, accounting for a 90% yield. These results overperformed other cathode materials, including Pt, Ni, Cu, Co, carbon, Pd/C, and Ru/C, which did not lead to any conversions. Metal Sn and Al cathodes gave the conversions to 2a about 40–45% as the maximum. However, side reactions including the Birch reduction to 3 and the formation of disulfide 4 took place spontaneously, inhibiting the further increase of 2a. In comparison, nAlClO@Al did not lead to the further decomposition of 2a even at its 90% yield. In the screening of solvents, DMF/EtOH was observed to be the optimum solvent. MeOH, THF/EtOH, and dioxane/H2O were totally ineffective since the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) took place instead. Without additive EtOH, the reaction in pure DMF or MeCN led to significant decomposition of 2a via C–S cleavage. The variation of the supporting electrolyte from Et4NCl to lithium salt inhibited the reaction completely because of the precipitation of metallic Li at the cathode. Other ammonium salts also worked under standard conditions with slightly inferior results. For the hydrogen source, ammonia was essential for the high conversion and high selectivity, which released nitrogen as the only side product. The change of NH3 to H2O resulted in the aging of the nanolayer of aluminum oxide to a nonconductive state, inhibiting the conversion. MeOH and EtOH also failed to deliver hydrogen in the reaction (details in Supporting Information, Tables S4–S9 and Figure S9).

2. The Discovery of nAlClO@Al-Catalyzed Electro-hydrogenation of Thiophene.

a Isolated yield in parentheses.

Mechanism Study

The electrochemistry and kinetic profile of the nAlClO@Al-catalyzed hydrogenation are further elucidated in Figure . Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) analysis indicated that the nAlClO@Al material exhibited much lower reactivity toward the HER than the metal Al cathode (Figure a, left). This distinct behavior was quantitatively demonstrated by measuring the Tafel slope for nAlClO@Al (1697 mV/dec) and Al (86 mV/dec) (Figure a, right). This contrast implied that nAlClO@Al gains a much wider window for the reduction of arene by inhibiting the HER. Therefore, we compared the Faraday efficiency (FE) and yield of 2a in the hydrogenation of 1a along these two cathodes, respectively. With the nAlClO@Al cathode, the reaction offered product 2a in a 90% 1H NMR yield at a 95% conversion with a 4 F/mol electricity, corresponding to a 90% FE (Figure b, left, Figure S29). The maximum FE of 39% from the metal Al cathode was achieved at a 39% yield and a 45% conversion (Figure b, right). It was found in both cases, and further electrolysis gave a higher conversion of 1a, whereas a lower yield of the product because the decomposition of the product 2a became faster by the depletion of 1a. This contrast revealed that the chemoselectivity at a high substrate/product ratio is critical since it was not possible to obtain a high yield via prolonged reaction. To evaluate the role of chloride in nAlClO@Al, different aluminum oxide layer materials were prepared with the anodic modification in a series of protonic media. The obtained modified Al–O/X materials were compared with nAlClO@Al using the electrocatalytic hydrogenation of 1a under standard conditions as the benchmark (Figure c). It was found that AlOTfO@Al gave an 85% NMR yield, slightly lower than that of nAlClO@Al. In contrast, the anode-treated aluminum oxide in diluted H2SO4 aqueous solution was almost ineffective. Next, the robustness of the catalyst was examined in a recycling reaction (Figure d). After five recycles of the catalyst, the yield of 2a and chemoselectivity were retained, and no obvious structural changes of nAlClO@Al were observed by SEM (Supporting Information, Figure S10). More cycles would lead to a lower yield and FE, but the nAlClO@Al cathode could regenerate easily by anodic procedure in HCl solution again. By comparing the XPS of nAlClO@Al before and after 8 cycles of the reaction (Supporting Information, Figure S11), it was deduced that the slight reduction of the Al2O3 nanolayer to metallic Al might be the reason for the decreased yield and FE. After regeneration with the preparation protocol of the anodic procedure in HCl solution again, nAlClO@Al provided a high yield. Next, the stability of the catalysts was assessed via chronopotentiometry (CP) experiments at a 10 mA/cm2 current density. The potential of the nAlClO@Al cathode was maintained within −2.7 V to −3.1 V vs Ag/AgCl for 50,000 s (Figure e). In addition, SEM/EDS analyses of the postrun cathode revealed that the nanostructure and elemental composition remained unaltered, confirming the stability of the nAlClO@Al material (Supporting Information, Figures S12 and S13). Furthermore, to verify the reproducibility of the electrocatalytic hydrogenation reaction, five samples of nAlClO@Al were prepared in parallel (Figure f). SEM analyses and resistance measurements did not reveal significant differences. In the subsequent hydrogenation of 1a, all five cathodes gave almost identical outcomes, with yields of 2a ranging from 85–89%. In addition, the tolerance to various conditions during the preparation of nAlClO@Al was verified, revealing that electrolysis with 10–20 mA/cm2 current density in a 0.5–2 M HCl aqueous solution for 2 h resulted in almost identical quality of the nAlClO@Al material. The sensitivity assessment of the catalytic reaction was conducted, exhibiting that the moisture sabotaged the reaction substantially (Figure g; Supporting Information, Table S10 and Figures S15–S19). If the reaction was conducted at −10 °C instead of room temperature, the conductivity of the solution dropped largely and inhibited the conversion.

2.

The electrocatalytic performance of the cathode material in hydrogenation of thiophene 1a. (a) The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) and Tafel plots of Al and nAlClO@Al in 2.0 equiv. Et4NCl and 0.1 mL of ethanol in an ammonia atmosphere; the scan rate is 10 mV/s. (b) Reaction performances in the hydrogenation of 1a with nAlClO@Al (left) and Al (right) cathodes with various charges under the same conditions. (c) The yield of the reaction using the Al material electro-processed in different protonic media. (d) Recycles of nAlClO@Al and corresponding conversion, yield, and Faraday efficiency of each cycle. Con. = conversion, FE = Faraday efficiency. The conversion and yield are determined by 1H NMR. (e) The chronopotentiometry (CP) measurement of the nAlClO@Al cathode. (f) The reproducibility of nAlClO@Al-catalyzed electro-hydrogenation of 1a. (g) The sensitivity assessment of the catalytic reaction.

To understand how the reaction occurs at AlClO@Al, the reduction of 1a was subjected to a series of controlled experiments. First, we explored the H source in the reaction with different deuterium-labeled chemicals (Scheme a). No deuterated product was detected when EtOD-d6 or DMF-d7 was employed as the D source. On the other hand, product 2a with a 75% deuterium incorporation ratio was obtained when gaseous ND3 was used instead of NH3, confirming that ammonia was the primary hydrogen source. We hypothesized that Et4NCl was a minor hydrogen source. Therefore, an experiment with Et4NCl at a 1/4 dosage to the standard conditions under ND3 was carried out, leading to an 86% deuterium incorporation ratio. This result confirms that Et4NCl was a side hydrogen source for this reaction (more information is provided in Figures S20–S23). In another experiment, the addition of t-BuOH, a hydrogen atom radical quencher, as an additive offered an identical yield of 2a, suggesting the hydrogen atom radical is not involved in the hydrogenation (Table S9). This result is consistent with the LSV analysis (Figure a) that the HER was inhibited with a cathodic potential even at −2.5 V (vs Ag/AgCl). In comparison, in the cyclic voltammetry (CV) analysis of 1a, the onset reduction took place at about −1.6 V vs Ag/AgCl, confirming the high chemoselectivity in the reaction (Scheme b).

3. Experiments on the Investigation of the Mechanism.

Next, we identified the intermediate of the reaction (Scheme c). When 1a was subjected to reduction with 2 F/mol electricity, about 44% of 2a was obtained and 50% recovery of 1a was achieved, suggesting the transient intermediate converts to the product instantly once generated. Then, three possible intermediates were synthesized and tested to elucidate the mechanism. Compound 3, the product from electrochemical Birch reduction in the work reported by the Baran group, was prepared and applied as a starting material under standard conditions with the nAlClO@Al cathode. In this experiment, only a trace of 2a was detected, with above 95% recovery of 3. On the other hand, compound 5 was synthesized separately and tested in the electrocatalytic hydrogenation; product 2a was obtained in an 85% yield. Subsequently, compound 6 was evaluated under the same electrocatalytic conditions, and no conversion was observed. These results supported the hydrogenation of 1a, undergoing a pathway regulated by the nAlClO@Al catalyst instead of by the substrate in Birch reduction. This conclusion was also supported by an experiment adopting naphthalene as a substrate (Supporting Information, Figure S24–S32). In turn, to study the interaction between the nanolayer of aluminum oxide and substrate, 1a adsorbed via vapor on nAlClO@Al and commercial neutral Al2O3 were measured by solid state 1H NMR (Scheme d). Compared with 1a adsorbed on neutral Al2O3, 1a adsorbed at the surface of nAlClO@Al had an up-field shift of approximately 0.1–0.2 ppm. This trend is consistent with the situation when arene gets π-coordinated with metal species. For verification, a 1H NMR titration experiment of 1a with a homogeneous Lewis acid was conducted. As TfOH-treated Al gave a comparable result to nAlClO@Al (Figure c), and Al(OTf)3 is soluble in NMR solvent (AlCl3 is insoluble in all common deuterated solvents), titration was conducted using Al(OTf)3 as the Lewis acid (Scheme d). It was found that the signals of aromatic C–H of 1a moved up-field with the increase of dosage of Al(OTf)3, confirming the observation in the solid-state 1H NMR. In contrast, such interaction was not observed when Al(OiPr)3 was applied instead of Al(OTf)3 (Supporting Information, Figures S33 and S34). With this observation, we proposed that the Lewis acid site in nAlClO@Al could also adopt coordination with the intermediate from 1a during hydrogenation.

Therefore, to understand how the chemoselectivity was regulated at the surface of the nAlClO@Al, a DFT study was conducted using an amorphous Cl–Al–O model (Scheme e). We presumed the surficial Lewis acid site of Al could stabilize the anionic carbon via the interaction of the negative charge of carbon and the vacant 2p orbital of Al (–Cl). Therefore, allylic protonation takes place with the ammonium cation generated at the anode as the proton source. Since the tetrahedral structure of the ammonium cation can exhibit steric interaction with the substrate, it brings regioselectivity to allylic protonation. With this model, the key transition states TS-1 to 3 and TS-2 to 5, both from the cathodic reduction of radical intermediate Int-1, were compared. It was found that TS-2 is more readily formed than TS-1 with a difference of 7.6 kcal mol–1. Therefore, product 5 was formed via nAlClO@Al catalysis in a predominant route complementary to Birch reduction.

Substrate Scope

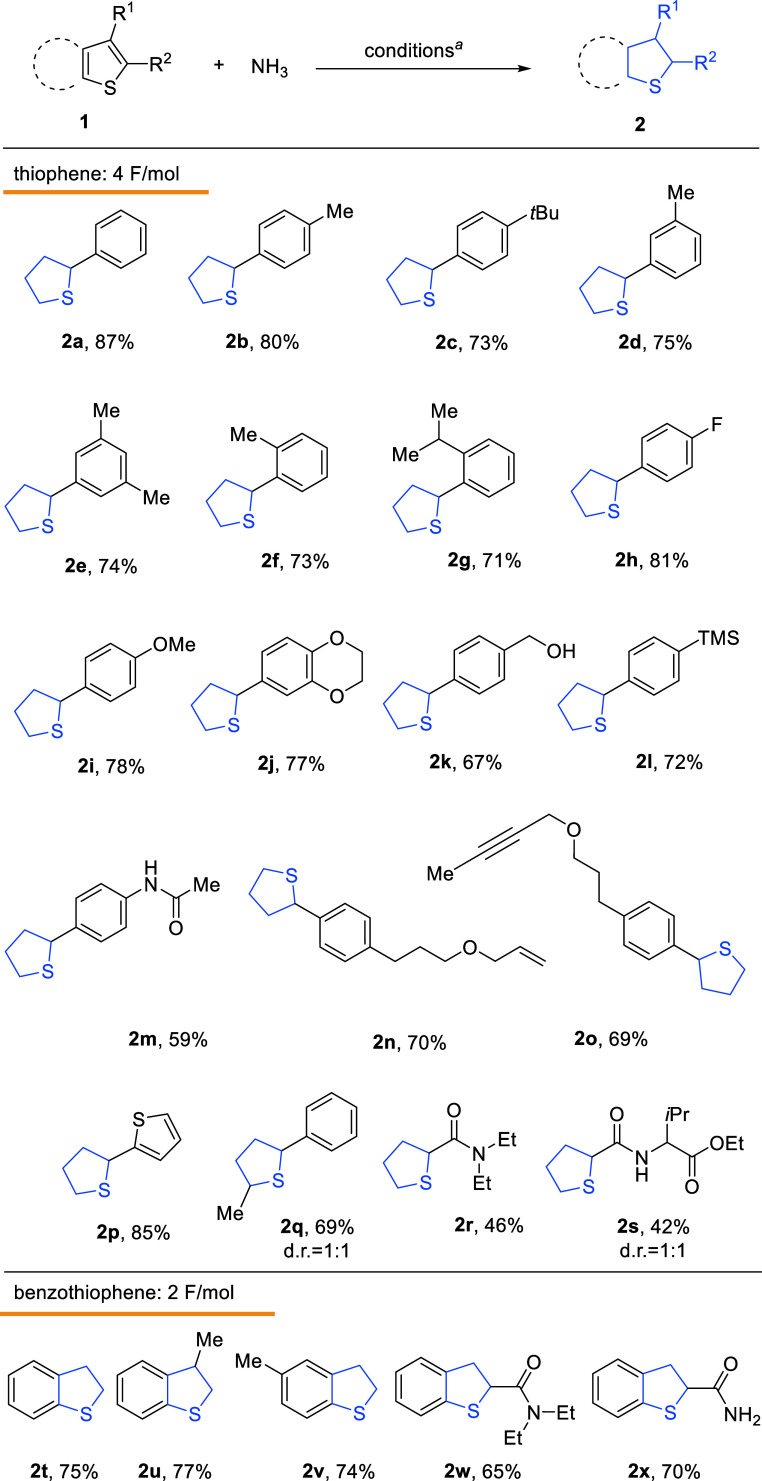

The scope of this electrocatalytic hydrogenation was explored with diverse phenylthiophenes (see all substrates in the Supporting Information, Figure S14) that were converted to corresponding products 2a–2m (Scheme ). A diversity of phenylthiophenes that bear alkyl, alkoxy, fluorine, hydroxyl, and trimethylsilyl groups were successfully hydrogenated to the corresponding products with good yields. It was noted that 2n and 2o could be obtained in a 70% and 69% yield, with the CC double and CC triple bond tolerated, which is incompatible in a transition metal-catalyzed hydrogenation system. 4H-2,2′-bithiophene 2p was obtained in an excellent yield of 85% as the sole product. A dr 1:1 ratio in methyl phenyl 4H-thiophene 2q confirmed the reaction underwent a stepwise reduction. Notably, the cyclic thioether motifs were prepared with thiophene amides (2r, 2s). The relatively low yields were partially due to the loss during purification. Products 2t–2x were synthesized from the benzothiophenes, respectively, in good yields with 2 F/mol electricity. On the other hand, due to the strong reductivity imposed by the nAlClO@Al, aryl ether, benzyl ether, benzyl halide, and some electron-deficient groups decomposed during the reaction (Supporting Information, Figure S35).

4. Scope of Thiophenes in the AlClO@Al-Catalyzed Electro-hydrogenation.

a Standard condition: 1 (0.2 mmol), Et4NCl (0.4 mmol), DMF (5 mL), GF anode, nAlClO@Al cathode, NH3 balloon, 10 mA/cm2 constant current, rt, 4 F/mol, isolated yields are reported.

Furthermore, we expanded the scope of electrocatalytic hydrogenation to extensive arenes 7 (Scheme ). It was delightful to observe that full carbon arenes such as naphthalene, anthracene, phenanthrene, and acenaphthylene were hydrogenated to aliphatic cycles in moderate to excellent isolated yields (8a–8f), including compound 8b, the bulky chemical for the phenol/cyclohexanone industry. Besides thiophene, other heterocycles were also hydrogenated with this protocol. The reduction of benzofuran and indole took place at the heterocycle, producing 8g (62%) and 8h (60%), respectively. Pyrimidazoles were converted to their 4H-products 8i and 8j. The 4H-isoquinoline was obtained from isoquinoline with this method in a 54% isolated yield (8k). The piperidines 8l were generated from phenylpyridine in moderate isolated yields. For the case of bipyridine, the partially reduced product 8m was successfully obtained as the sole product. The steric effect had a strong influence on the adsorption of substrate on nAlClO@Al. Steric alkyl substitutions, for example, t-butyl and multiple methyl groups, on the phenyl ring inhibited the adsorption of substrate and corresponding conversion (Supporting Information, Figure S35).

5. Scope of Arenes in the nAlClO@Al-Catalyzed Electro-hydrogenation.

a Standard condition: 7 (0.2 mmol), Et4NCl (0.4 mmol), DMF (5 mL), GF anode, nAlClO@Al cathode, NH3 balloon, 10 mA/cm2 constant current, rt, 4 F/mol, isolated yields are reported.

b Eight F/mol, 12.5 mA/cm2.

c Four F/mol, 15 mA/cm2.

d Two F/mol.

We subsequently explored the synthetic application of this electrocatalytic hydrogenation reaction. This electrocatalytic hydrogenation of thiophene 1a was readily conducted on the gram scale. Almost identical yield was observed even at a current of 100 mA/cm2 in an undivided cell reactor (Scheme a, Supporting Information Figure S36). Product 2a could be smoothly oxidized to the corresponding sulfoxide 9. Further oxidation of 2a led to sulfone 10, which is an ingredient for hair dye and an intermediate of a vasodilator. Next, we demonstrated that nAlClO@Al was also an efficient electrocatalyst for other functional groups (Scheme b). For example, alkene 11a, ketone 13, and antipyrine 15 were converted to corresponding products 12a, 14, and 16 in 52% to 88% yields. We subsequently explored whether this reduction was compatible with the sacrificial anode, which allowed for additional labile functional groups (Scheme c). For example, furan-derived 7n could be converted to product 8n, the unprotected amine intermediate for the alpha-adrenergic blocker terazosin, in a 55% yield with a zinc anode. Two pharmaceutical compounds, tamoxifen 11b and carbamazepine 11c, were hydrogenated to products 12b and 12c, respectively. Next, (R)-binol dimethyl ether 7o of 96% ee was converted to the diH-binol derivative 8o in a 63% isolated yield. It should be noted that the optical purity remained intact, which was not achieved in the previously reported example. Similarly, 2H-agomelatine 8p and 2H-naftopidil 8q were prepared in good yields via the same protocol. Finally, we explored the application of 4H-thiophene compounds as a selective extractant for precious metals (Scheme d). As metals are typically recovered under strong acidic conditions, the extractant must remain unaffected by the protonation. We tried to extract PdCl2 from its hydrochloric acid solution with substrate 1p and product 2p. A distinct difference in the extraction ratio was observed. ICP–MS analysis revealed that 1p extracted only about 5% of the Pd species out of the aqueous HCl solution; on the other hand, almost quantitative extraction of the palladium species was realized with 2p. Next, we evaluated the selectivity of 2p in a simulated waste electrical and electronic equipment solution (WEEE) incorporating Pd, Au, Pt, Ru, Zn, and Cu salts at similar concentrations. ICP–MS analysis showed 2p was highly selective toward Pd and Au salts and left other metal ions in aqueous solution. In particular, we found that product 2a was not as effective as 2p, suggesting that the second coordinative group was also essential for successful extraction (details in Supporting Information, Table S11 and Figures S37–S40). Therefore, this electrocatalytic hydrogenation of substituted thiophene provides a potential route for the production of extractants with tunable efficiency and selectivity.

6. Synthetic Exploration of the Electrocatalytic Hydrogenation and Corresponding Applications.

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrate the first example of electrocatalytic hydrogenation with an Al-based material. The Al–Cl Lewis acid-modified aluminum oxide nanolayer allows the quantum tunneling of electrons and regulates the substrate via a non-Birch pathway. With these features, the first electrocatalytic full hydrogenation of a substituted thiophene was achieved. This chemistry covers a myriad of full carbon, O-hetero, and N-hetero arenes, producing a number of aliphatic rings with up to 90% Faraday efficiency. This discovery would lead to the design of new main-group Lewis acid nanomaterials for electrocatalytic reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22071105, 22031008, 22471125 for C.X.). This work is supported by the Elite Student Development Program for Fundamental Disciplines 2.0 (20221021). We appreciate the assistance of Prof. Dr. Xinghua Xia and Dr. Jin Li in the in situ IR analysis.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.5c06034.

XPS analysis and SEM image of nAlClO@Al; details of condition optimization and mechanism study; experimental procedures; characterization of all new compounds; and DFT computational data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Zhang Z., Butt N. A., Zhang W.. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Nonaromatic Cyclic Substrates. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:14769–14827. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X., Li X., Xie J., Zhou Q.. Recent Progress in Homogeneous Catalytic Hydrogenation of Esters. Acta Chim. Sinica. 2019;77:598–612. doi: 10.6023/A19050166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Wen J., Zhang X.. Chiral Tridentate Ligands in Transition Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2021;121:7530–7567. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabré A., Verdaguer X., Riera A.. Recent Advances in the Enantioselective Synthesis of Chiral Amines via Transition Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2022;122:269–339. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Astruc D.. The Golden Age of Transfer Hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:6621–6686. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zhou M., Wang A., Zhang T.. Selective Hydrogenation over Supported Metal Catalysts: From Nanoparticles to Single Atoms. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:683–733. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie R., Tao Y., Nie Y., Lu T., Wang J., Zhang Y., Lu X., Xu C. C.. Recent Advances in Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation with Formic Acid over Heterogeneous Transition Metal Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2021;11:1071–1095. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c04939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qu R., Junge K., Beller M.. Hydrogenation of Carboxylic Acids, Esters, and Related Compounds over Heterogeneous Catalysts: A Step toward Sustainable and Carbon-Neutral Processes. Chem. Rev. 2023;123:1103–1165. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Dimitratos N., Rossi L. M., Thonemann N., Beale A. M., Wojcieszak R.. Hydrogenation of CO2 for sustainable fuel and chemical production. Science. 2025;387:eadn9388. doi: 10.1126/science.adn9388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeldt M. P., Nairoukh Z., Li W., Glorius F.. Hydrogenation of fluoroarenes: Direct access to all-cis-(multi)fluorinated cycloalkanes. Science. 2017;357:908–912. doi: 10.1126/science.aao0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Yang J., Peters B. B. C., Massaro L., Zheng J., Andersson P. G.. Asymmetric Full Saturation of Vinylarenes with Cooperative Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Rhodium Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:20377–20383. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c09975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.-X., Zhu Z.-H., Chen M.-W., Yu C.-B., Zhou Y.-G.. Rhodium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of All-Carbon Aromatic Rings. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022;61:e202205623. doi: 10.1002/anie.202205623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viereck P., Hierlmeier G., Tosatti P., Pabst T. P., Puentener K., Chirik P. J.. Molybdenum-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Fused Arenes and Heteroarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:11203–11214. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c02007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hierlmeier G., Tosatti P., Puentener K., Chirik P. J.. Identification of Cyclohexadienyl Hydrides as Intermediates in Molybdenum-Catalyzed Arene Hydrogenation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023;62:e202216026. doi: 10.1002/anie.202216026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaithal A., Sasmal H. S., Dutta S., Schäfer F., Schlichter L., Glorius F.. cis-Selective Hydrogenation of Aryl Germanes: A Direct Approach to Access Saturated Carbo- and Heterocyclic Germanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145:4109–4118. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c12062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.-X., Yu Z.-X.. Arene Reduction by Rh/Pd or Rh/Pt under 1 atm Hydrogen Gas and Room Temperature. Org. Lett. 2024;26:3458–3462. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.4c01029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lückemeier L., Pierau M., Glorius F.. Asymmetric arene hydrogenation: towards sustainability and application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023;52:4996–5012. doi: 10.1039/D3CS00329A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Shi H., Yin G.. Synthetic techniques for thermodynamically disfavoured substituted six-membered rings. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024;8:535–550. doi: 10.1038/s41570-024-00612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeldt M. P., Nairoukh Z., Dalton T., Glorius F.. Selective Arene Hydrogenation for Direct Access to Saturated Carbo- and Heterocycles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:10460–10476. doi: 10.1002/anie.201814471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha A. G., Franco A., Krezel A. M., Rumsey J. M., Alberti J. M., Knight W. C., Biris N., Zacharioudakis E., Janetka J. W., Baloh R. H., Kitsis R. N., Mochly-Rosen D., Townsend R. R., Gavathiotis E., Dorn G. W.. MFN2 agonists reverse mitochondrial defects in preclinical models of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A. Science. 2018;360:336–341. doi: 10.1126/science.aao1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma, H. ; Yamada, H. . L’Oreal Patent, JP 2019011284 A, 2019.

- Matsingos C., Al-Adhami T., Jamshidi S., Hind C., Clifford M., Mark Sutton J., Rahman K. M.. Synthesis, microbiological evaluation and structure activity relationship analysis of linezolid analogues with different C5-acylamino substituents. Biorg. Med. Chem. 2021;49:116397. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K., Akiyama R., Kobayashi S.. Recoverable, Reusable, Highly Active, and Sulfur-Tolerant Polymer Incarcerated Palladium for Hydrogenation. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:2871–2873. doi: 10.1021/jo0358527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S., Beiring B., Ortega N., Paul D., Glorius F.. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Thiophenes and Benzothiophenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:15241–15244. doi: 10.1021/ja306622y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul D., Beiring B., Plois M., Ortega N., Kock S., Schlüns D., Neugebauer J., Wolf R., Glorius F.. A Cyclometalated Ruthenium-NHC Precatalyst for the Asymmetric Hydrogenation of (Hetero)arenes and Its Activation Pathway. Organometallics. 2016;35:3641–3646. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B., Chandrashekhar V. G., Ma Z., Kreyenschulte C., Bartling S., Lund H., Beller M., Jagadeesh R. V.. Development of a General and Selective Nanostructured Cobalt Catalyst for the Hydrogenation of Benzofurans, Indoles and Benzothiophenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023;62:e202215699. doi: 10.1002/anie.202215699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latypova F. M., Parfenova M. A., Lyapina N. K.. Reduction of thiophenes in the presence of sulfuric acid and zinc. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2011;47:1078–1084. doi: 10.1007/s10593-011-0877-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curless L. D., Clark E. R., Dunsford J. J., Ingleson M. J.. E–H (E = R3Si or H) bond activation by B(C6F5)3 and heteroarenes; competitive dehydrosilylation, hydrosilylation and hydrogenation. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:5270–5272. doi: 10.1039/C3CC47372D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini C., Meli A.. Hydrogenation, Hydrogenolysis, and Desulfurization of Thiophenes by Soluble Metal Complexes: Recent Achievements and Future Directions. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:109–116. doi: 10.1021/ar970029g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lückemeier L., De Vos T., Schlichter L., Gutheil C., Daniliuc C. G., Glorius F.. Chemoselective Heterogeneous Hydrogenation of Sulfur Containing Quinolines under Mild Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146:5864–5871. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c11163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M., Kawamata Y., Baran P. S.. Synthetic Organic Electrochemical Methods Since 2000: On the Verge of a Renaissance. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:13230–13319. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Gao X., Lv Z., Abdelilah T., Lei A.. Recent Advances in Oxidative R1-H/R2-H Cross-Coupling with Hydrogen Evolution via Photo-/Electrochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:6769–6787. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novaes L. F. T., Liu J., Shen Y., Lu L., Meinhardt J. M., Lin S.. Electrocatalysis as an enabling technology for organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50:7941–8002. doi: 10.1039/D1CS00223F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhade S. A., Singh N., Gutiérrez O. Y., Lopez-Ruiz J., Wang H., Holladay J. D., Liu Y., Karkamkar A., Weber R. S., Padmaperuma A. B., Lee M.-S., Whyatt G. A., Elliott M., Holladay J. E., Male J. L., Lercher J. A., Rousseau R., Glezakou V.-A.. Electrocatalytic Hydrogenation of Biomass-Derived Organics: A Review. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:11370–11419. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Chen F., Zhao B.-H., Wu Y., Zhang B.. Electrochemical hydrogenation and oxidation of organic species involving water. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024;8:277–293. doi: 10.1038/s41570-024-00589-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters B. K., Rodriguez K. X., Reisberg S. H., Beil S. B., Hickey D. P., Kawamata Y., Collins M., Starr J., Chen L., Udyavara S., Klunder K., Gorey T. J., Anderson S. L., Neurock M., Minteer S. D., Baran P. S.. Scalable and safe synthetic organic electroreduction inspired by Li-ion battery chemistry. Science. 2019;363:838–845. doi: 10.1126/science.aav5606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K., Griffin J., Harper K. C., Kawamata Y., Baran P. S.. Chemoselective (Hetero)Arene Electroreduction Enabled by Rapid Alternating Polarity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:5762–5768. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c02102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. S., Love A., Mansouri Z., Waldron Clarke T. H., Harrowven D. C., Jefferson-Loveday R., Pickering S. J., Poliakoff M., George M. W.. High-Productivity Single-Pass Electrochemical Birch Reduction of Naphthalenes in a Continuous Flow Electrochemical Taylor Vortex Reactor. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022;26:2674–2684. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.2c00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shida N., Shimizu Y., Yonezawa A., Harada J., Furutani Y., Muto Y., Kurihara R., Kondo J. N., Sato E., Mitsudo K., Suga S., Iguchi S., Kamiya K., Atobe M.. Electrocatalytic Hydrogenation of Pyridines and Other Nitrogen-Containing Aromatic Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146:30212–30221. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c09107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbo R. S., Kurimoto A., Brown C. M., Berlinguette C. P.. Efficient Electrocatalytic Hydrogenation with a Palladium Membrane Reactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:7815–7821. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b01442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Liu C., Wang C., Lu S., Zhang B.. Selective Transfer Semihydrogenation of Alkynes with H2O (D2O) as the H (D) Source over a Pd-P Cathode. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:21170–21175. doi: 10.1002/anie.202009757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Liu C., Wang C., Yu Y., Shi Y., Zhang B.. Converting copper sulfide to copper with surface sulfur for electrocatalytic alkyne semi-hydrogenation with water. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3881. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24059-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S., Wu Y., Wang C., Gao Y., Li M., Zhang B., Liu C.. Electrocatalytic hydrogenation of quinolines with water over a fluorine-modified cobalt catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:5297. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32933-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Zenner J., Johny J., Kaeffer N., Bordet A., Leitner W.. Electrocatalytic hydrogenation of alkenes with Pd/carbon nanotubes at an oil–water interface. Nat. Catal. 2022;5:1110–1119. doi: 10.1038/s41929-022-00882-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Mao X., Jiang S.. Effect of thermally grown Al2O3 on electrical insulation properties of thin film sensors for high temperature environments. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 2021;331:113033. doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2021.113033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht T.. Electrochemical tunnelling sensors and their potential applications. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:829. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht T., Horswell S., Allerston L. K., Rees N. V., Rodriguez P.. Electrochemical processes at the nanoscale. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2018;7:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.coelec.2017.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri M. R., Kluge R. M., Haid R. W., Fortmann J., Ludwig A., Bandarenka A. S., Alexandrov V.. Electron Tunneling at Electrocatalytic Interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2023;127:6321–6327. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.3c00207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer F., Lückemeier L., Glorius F.. Improving reproducibility through condition-based sensitivity assessments: application, advancement and prospect. Chem. Sci. 2024;15:14548–14555. doi: 10.1039/D4SC03017F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzer L., Schäfers F., Glorius F.. Rapid Assessment of the Reaction-Condition-Based Sensitivity of Chemical Transformations. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:8572–8576. doi: 10.1002/anie.201901935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M., Chen J., Su Z., Peng Y., Zou P., Yao X.. Anodic Oxidation in Aluminum Electrode by Using Hydrated Amorphous Aluminum Oxide Film as Solid Electrolyte under High Electric Field. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016;8:11100–11107. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b00945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M., Chen J., Yang P., Shan W., Hu B., Yao X.. Preparation and Breakdown Property of Aluminum Oxide Thin Films Deposited onto Anodized Aluminum Substrate. Ferroelectrics. 2013;455:21–28. doi: 10.1080/00150193.2013.843409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., He L., Liu X., Cheng X., Li G.. Electrochemical Hydrogenation with Gaseous Ammonia. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:1759–1763. doi: 10.1002/anie.201813464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Lin Y., Wu W.-Q., Hu W.-Q., Xu J., Shi H.. Amination of Aminopyridines via η6-Coordination Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146:22906–22912. doi: 10.1021/jacs.4c07306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan T., Sun L., Wu Z., Wang R., Cai X., Lin W., Zheng M., Wang X.. Mild and metal-free Birch-type hydrogenation of (hetero)arenes with boron carbonitride in water. Nat. Catal. 2022;5:1157–1168. doi: 10.1038/s41929-022-00886-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.