Abstract

Aim

The interaction between dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) and vascular endothelial cells (ECs) is crucial to the speedy establishment of functional blood circulation within the transplanted pulp tissue. It is a complex process involving direct cell contact and paracrine signalling. The transmembrane domains of α1-Na+/K+-ATPase (ATP1A1) have been shown to influence tumour angiogenesis. Its role in regulating DPSCs/ECs interaction in vascular formation remains unknown. This study aimed to explore ATP1A1 on DPSCs/ECs communication, vascular network formation, and underlying mechanisms.

Methods

The formation of vessel structures within different culture systems was examined. The expression of pericyte-like markers and Na+/K+-ATPase-related genes and proteins were systematically analysed. Immunofluorescence staining was performed to examine the localisation of ATP1A1. Total and phosphorylated proteins were evaluated to identify and explore the signalling pathways activated under cocultured conditions. Downstream signalling was also investigated after the inhibition of ATP1A1.

Results

Direct coculture accelerated vessel network formation and prolonged its stability compared to indirect systems. ATP1A1 expression and SMC-specific marker (α-SMA) levels significantly increased in direct coculture systems, with nuclear α-SMA localisation and ATP1A1 enrichment at cell-contact sites. Protein assay revealed activated Src/AKT pathways and upregulated FGF-2/activin A secretion in coculture supernatants. ATP1A1 inhibition reduced α-SMA expression, impairing SMC differentiation.

Conclusion

Direct DPSCs-HUVECs contact stabilises vessel networks via ATP1A1-mediated Src/AKT activation, driving FGF-2/activin A secretion and initiating SMC differentiation. This highlights that ATP1A1 may be critical for pericyte-like transition and vascular microenvironment optimisation in pulp angiogenesis.

Clinical Significance

This research informed strategies aimed at pulp tissue regeneration. The findings hold significant implications for enabling the biological restoration of tooth vitality and function in the field of clinical regenerative treatment.

Key words: ATP1A1, Coculture, Dental pulp stem cells, Smooth muscle cells, Vessel stability

Introduction

The dental pulp encompasses profuse vascularisation, affluent nerve innervation, and various multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). These unique features facilitate the pulp in accomplishing its vital functions, including nutrition provision, sensate, self-repair, etc., for the tooth.1 However, once the pulp tissue is damaged, its regeneration is extremely challenging due to the anatomical constraints of the root canal system in which it is enclosed. A critical requirement is rapidly establishing functional blood circulation to support the cells’ metabolism and survivability within the transplanted pulp construct.2,3

Current research on vascular regeneration of dental pulp tissue focuses primarily on two key strategies: in situ angiogenesis and pre-vascularisation of scaffolds. These approaches involve intricate cell-cell interactions and the secretion of angiogenic factors, which serve as signals guiding the regeneration process.4, 5, 6

It was reported that MSCs can support endothelial cells (ECs) in the process of new blood vessel formation and play a critical role in tissue regeneration.7 Similarly, dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), as seed cells in pulp tissue engineering, are essential for pulp-dentin complex formation and vasculature regeneration.8,9 DPSCs guide endothelial angiogenesis via paracrine signalling and stabilise the newly formed vessels by functioning in a manner analogous to pericytes.8,10 This interaction is largely mediated through coordinated signallings between the 2 types of cells. A study showed that controlling the distance between ECs and MSCs within a 3D-printed coculture system can influence angiogenesis, demonstrating that indirect contact between ECs and MSCs can efficiently stimulate local tissue angiogenesis through the release of paracrine signals,11 attributing to increased secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in DPSCs and associated signalling through VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) in ECs.10 Additionally, fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) has proven to be a major inducer of VEGF secretion in DPSCs.5 Besides the classical paracrine mechanism, recent coculture studies have highlighted other regulatory pathways in regulating DPSC pericyte differentiation.12, 13, 14 Direct contact coculture maintains intercellular connections,15 closely mimicking the in vivo state and maximising intercellular interactions through membrane connections. Such direct cell-cell communication is crucial for angiogenesis and can be influenced by multiple factors. For example, our recent study revealed that DPSCs and ECs direct coculture promoted TGF-β1 secretion, driving DPSCs differentiation towards smooth muscle cells (SMCs) via the TGF-β1/ALK5 signalling pathway.9,13 Activin A was also elevated, suppressing VEGFR2 activation in ECs and stabilising the newly formed vessel structure.16, 17, 18 Previous studies also reported that Na/K-ATPase (NKA), a transmembrane heterodimer composed of a catalytic α subunit and a glycosylated β subunit, participated in signal transduction in cell-cell direct contact manner.19,20 Variations in the transmembrane domains of ATP1A1 can induce tumourigenesis and promote cell proliferation.21 ATP1A1 expression levels were altered in atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases, which are associated with abnormal angiogenesis.22 ATP1A1 serves as a novel recruiting factor for membrane-bound FGF-2,23 influencing angiogenesis.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 RNAi-mediated downregulation of ATP1A1 significantly inhibited the secretion of FGF-2.29 These findings suggest that ATP1A1 may play a significant role in angiogenesis.

Therefore, this study aimed to use an in vitro coculture model of HUVECs and DPSCs to investigate whether ATP1A1 regulates cell-cell interactions between ECs and DPSCs and promotes DPSC differentiation toward SMC phenotype.

Method

Cell culture and coculture

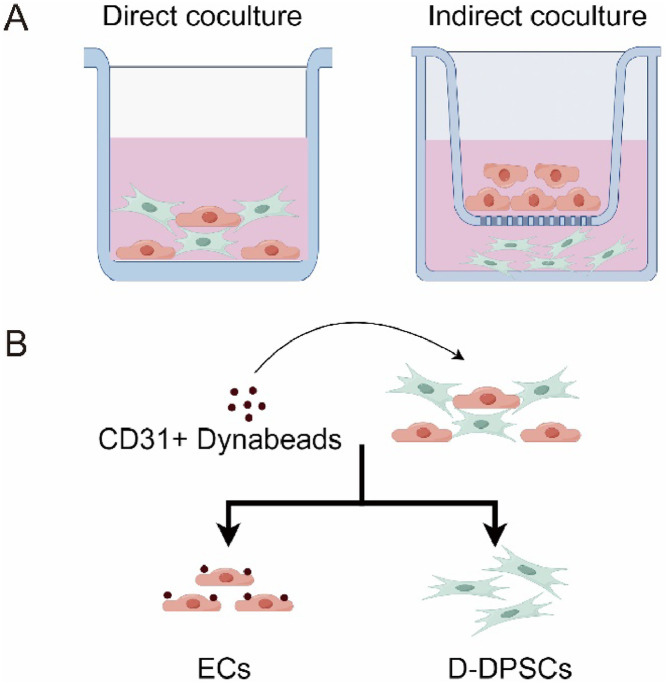

The primary DPSCs were purchased from iCell Bioscience Inc. and were grown in complete media (α-MEM supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) at 37°C with humidified air containing 5% CO2. Primary HUVECs from iCell Bioscience Inc. were cultured in Endothelial Cell Medium (ECM) (1001, ScienCell) supplemented with 10% FBS, 30 μg/mL ECGS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C. Passages 3 to 5 of hDPSCs and 4 to 8 of HUVECs were used for all experiments. For direct and indirect coculture, a basic ECM medium was used to alleviate the effect of medium composition on growth factors (Figure 1A). DPSCs and HUVECs were combined at a 1:1 ratio (3-5 × 105 cells of each type per well in 6-well plates).9,30 Cell seeding density was kept consistent across all experimental replicates to ensure reproducibility.

Fig. 1.

Different coculture methods of endothelial cells and dental pulp stem cells in vitro. (A) Methods of direct coculture and indirect coculture. (B) Separation of direct coculture cells. The schematic diagram of methods was generated by Figdraw.

Separation of direct coculture cell

The separation of direct coculture cells was performed as described previously.13 The DPSCs were isolated after direct coculture of HUVECs and DPSCs. HUVECs and DPSCs were seeded as 3 × 105 each well in a 6-well plate and directly cocultured for 4 to 48 hours. Then, the cocultured cells were collected in PBS as cell suspension. 1 mL cell suspension was mixed with 25 μL prewashed Dynabeads CD31 Endothelial Cell (11155D, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a tube. The Dynabeads and cell mixture were incubated at 4°C for 20 minutes with rotation. Afterward, the tube was placed in a magnet for 2 minutes. The supernatant containing the direct coculture DPSCs (D-DPSCs) was transferred to a new plate, and bead-bound HUVECs were left in the tube (Figure 1B).

Total RNA isolation and RNA sequence

After coculture, total RNA from DPSCs and HUVECs was isolated by Trizol (B511311, Sangon Biotech) and then sent to BGI Company for RNA-seq. The differently expressed genes (DEGs) were analysed using the ‘DEseq2’ R package. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) and Gene Ontology enrichment analysis (GO, http://www.geneontology.org/) were also performed in Dr Tom's multiomics data mining system (https://biosys.bgi.com) for data analysis, visualisation, and mining. The Library Construction method was detailed in the supplementary material.

RNA interference

hDPSCs were transfected at approximately 60% confluency in opti-mem medium (antibiotic-free, Gibco) with 50nM siRNA targeting ATP1A1 (MCE), using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 4 hours, cells were washed with PBS A and re-fed with complete growth media, and cultured for an additional 48 hours.

Quantitative real-time PCR

After 2 days of induction, total RNA was extracted from the cells using the EZ-press RNA Purification Kit (EZBiosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the Color Reverse Transcription Kit (A0010CGQ, EZBioscience). cDNA amplification was performed using 2 × SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (A0012-R1, EZBioscience). Each assay was implemented in triplicate. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1. The relative expression of target genes was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method with normalisation to the control group.

Table 1.

RT-qPCR primer sequences.

| Gene | Primer (5’-3’) | Accession number |

|---|---|---|

| ATP1A1 | GGCAGTGTTTCAGGCTAACCAG TCTCCTTCACGGAACCACAGCA |

NM_001160234 |

| α-SMA | CCGACCGAATGCAGAAGGA ACAGAGTATTTGCGCTCCGAA |

NM_001141945 |

| INHBA | GCAGTCTGAAGACCACCCTC ATGATCCAGTCATTCCAGCC |

NM_002192 |

| SM22α | AGTGCAGTCCAAAATCGAGAAG CTTGCTCAGAATCACGCCAT |

NM_001001522 |

| GAPDH | GGCTCTCCAGAACATCATCCCTGC GGGTGTCGCTGTTGAAGTCAGAGG |

NM_017008.4 |

Protein extraction and Western blotting

Proteins were extracted using a RIPA Lysis Buffer (P0013B, Beyotime) containing a Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (P002, NCM) for SDS-PAGE with Tris glycine-SDS running buffer. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (P0012, Beyotime). A total of 20 μg of total protein was subjected to gel electrophoresis in 10% to 12.5% acrylamide gel and electroblotted onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked in fast blocking buffer (P30500, NcmBlot) for 10 minutes at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. The membranes were washed, and the bands were detected by the ECL after incubating with HRP secondary antibodies for 1 hr. Then, the bands were exposed to the TANON gel imager. The results were analysed using ImageJ software.

Tube formation assay

The angiogenesis ability of HUVECs was determined using an in vitro tube formation assay. Corning Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix (354234, BD Biosciences) was thawed at 4 °C overnight. The next day, the Matrix was placed on a 48-well plate and then coagulated at 37°C for 30 minutes. A total of 1 × 104 cells/well were seeded in the matrix-coated plate and cultured for 1 to 7 days, then photographed under a Carl Zeiss microscope (Jena, Germany).

Wound healing experiments

HUVECs were seeded into six-well plates (3 × 105 cells per well) and incubated with different concentrations of ouabain (10nM, 25nM, 50nM, MCE) or si-RNA for 48 hours to allow for initial attachment. A sterile pipette tip was employed to create a linear wound across the confluent cell monolayer. Following scratch formation, the culture surface was gently rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline to eliminate detached cellular debris. A regular medium or medium with ouabain was then added to each plate. Cell migration was inspected by microscopy at 0 and 48 hours.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The coculture medium was collected at the indicated time points as described above. Activin A and FGF-2 expression levels in culture supernatant were analysed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (SYP-H0001, SYP-H0610, UpingBio).

Immunofluorescence

The cells were seeded in coverslips and were fixed with methanol at –20°C. The cell slips were rinsed with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS (PBST) for 5 minutes thrice, blocked with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) in 0.3% PBST at room temperature for 1.5 hours, then incubated with anti-ATP1A1 (Abcam) at 1:200 dilution and anti-α-SMA (Boster) at 1:200 dilution at 4 °C overnight. After washing 3 times, the slips were incubated with a corresponding secondary antibody at RT for 2 hours. After washing 3 times, the samples were incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Beyotime) for 10 minutes. Fluorescence images were captured using a Carl Zeiss fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Student’s unpaired t-test was used to assess statistically significant differences between 2 groups. One-way ANOVA and post hoc multiple comparison tests were used to compare more than 2 groups. Statistical significance was resented as P < .05. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5 software.

Results

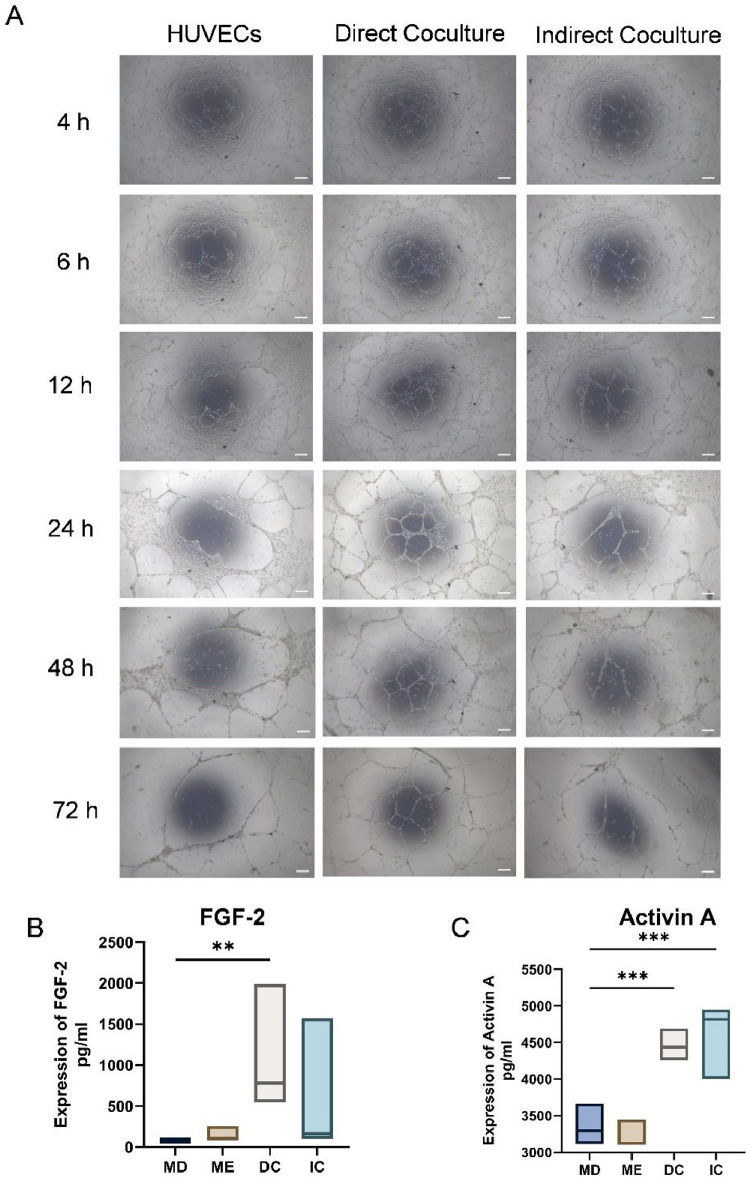

Direct coculture supernatant promotes vessel formation and stability in vitro

Supernatants from 3 distinct culture conditions were filtered and introduced into an in vitro three-dimensional ECs culture system to assess their angiogenic potential. Continuous observation over a 7-day period revealed that direct coculture facilitated earlier vascular network formation and sustained it for a longer duration. Specifically, from 6 to 72 hours post-treatment, the direct coculture groups exhibited a significantly higher number of nodes and branches than the control and indirect coculture groups (Figure 2A).

Fig. 2.

Different coculture methods influence the formation of vessel-like structures in vitro. (A) Tube formation on Matrigel after 4, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours of coculture medium incubation. (B-C) ELISA analysis of the FGF-2 and activin A level in CM of HUVECs and DPSCs from monoculture and cocultures. Data are presented as box plots showing the median (horizontal line) and minimum and maximum values (box boundaries) for n = 3 replicates, *P < .05, ***P < .001, Scale Bar = 100 μm.

ELISA analysis demonstrated significant differences in protein secretion between mono-culture and coculture conditions. The concentration of activin A in the coculture supernatant increased to approximately 4500 pg/mL, which was markedly higher than that observed in DPSCs mono-culture (3359 ± 240.2 pg/mL) and HUVECs mono-culture (3223 ± 162.1 pg/mL) (P < .05; Figure 2C). Simultaneously, FGF-2 secretion was substantially elevated in the direct coculture system, reaching concentrations exceeding 1000 pg/mL, compared to those in DPSCs and HUVECs mono-cultures (P < .05; Figure 2B). These findings indicate a notable increase in FGF-2 secretion in the direct coculture system.

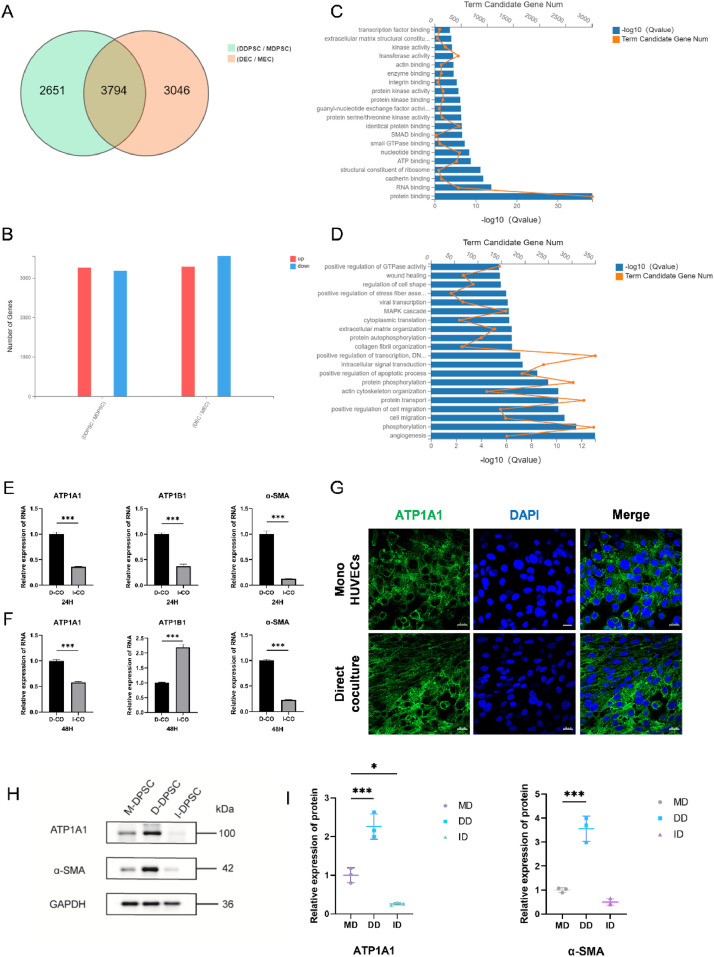

Effects of direct coculture on DPSC differentiation into SMCs and the expression of ATP1A1

The RNA-seq datasets generated and analysed in this study are available in the NCBI SRA repository with the primary accession code PRJNA1240367 (https://www.ncbi.nl-m.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1240367). Basic information of the quality metrics of filtered reads are provided in the summary table (Supplementary Table S1, S2). After assessing the expression profiles of differentially expressed genes from the two culture methods through RNA sequencing, we found that the gene ACTA2, which encodes α-SMA, was upregulated in directly coculture DPSCs, while no significant changes were noted in indirect coculture. Similarly, INHBA, encoding activin A, showed significant upregulation in direct coculture condition but remained unchanged in indirect coculture (Table 2). Additionally, GO functional enrichment analysis of the intersection between differentially expressed genes before and after direct coculture and upregulated genes in DPSCs indicated that direct coculture predominantly affected functions related to angiogenesis and protein binding (Figure 3A-D).

Table 2.

Differential expression analysis of genes from RNA-Seq data.

| Gene | Compare group | log2Ratio | Qvalue |

|---|---|---|---|

| INHBA | MDPSC-vs-DDPSC | 1.566890052 | 8.28E-142 |

| MDPSC-vs-IDPSC | −0.577129741924563 | 1.93E-64 | |

| ACTA2 | MDPSC-vs-DDPSC | 0.431898543 | 4.71E-08 |

| MDPSC-vs-IDPSC | −0.0067347566798591 | 0.98 |

Fig. 3.

RNA-sequencing data and the expression of ATP1A1 and α-SMA after direct coculture. (A-B) Differently expressed Genes (DEGs) analysis of cells after direct coculture. (C-D) Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed the enrichment of biological processes among the upregulated genes of DPSCs. (E-F) RT-qPCR analysis of the relative mRNA expression of ATP1A1, ATP1B1 and α-SMA in cells after coculture for 24 and 48 hours. (G) Representative immunofluorescence images of ATP1A1(green) and DAPI (blue) in HUVECs after coculture for 2 days. Scale bar = 20 μm. (H-I) Western blot analysis of the expression of ATP1A1 and α-SMA in DPSCs after coculture for 48 hours. Data are mean ± SD for n = 3 replicates, *P < .05, ***P < .001.

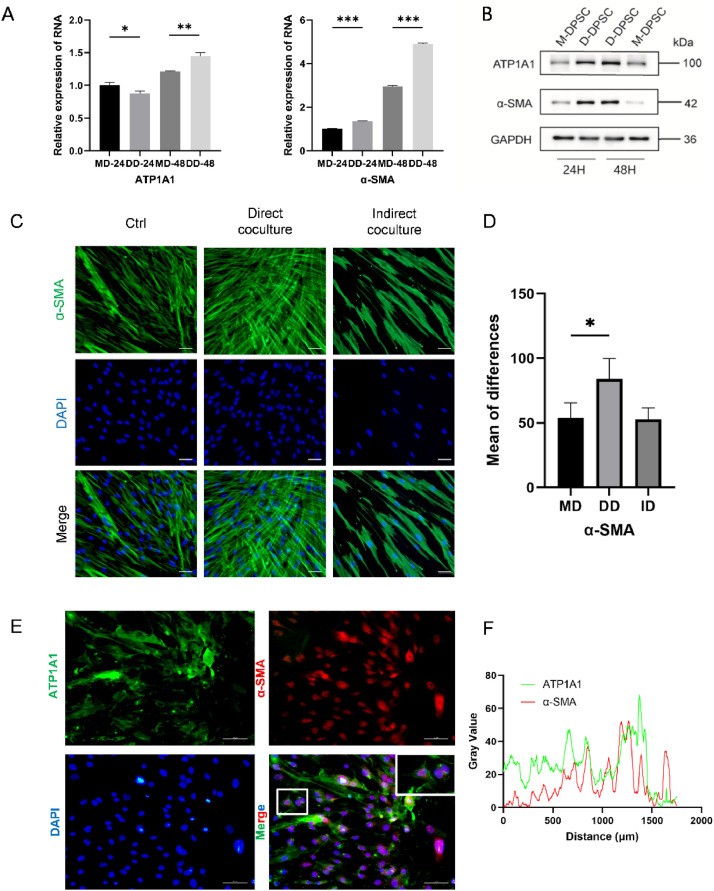

Total RNA was extracted from cells in both the direct and indirect coculture groups to evaluate the expression levels of NKA and pericyte-marker mRNA. Our results demonstrated that ATP1A1 expression in the direct coculture group was significantly elevated compared to the indirect coculture group at both 24 and 48 hrs (Figure 3E, 3F). To further investigate the vasculogenic differentiation potential of DPSCs, α-SMA expression was also assessed, which was found to be higher than in the direct coculture group at the same time points (Figures 3H, 3I, 4A, 4B).

Fig. 4.

DPSCs exhibited differentiation properties toward SMCs after contact with HUVECs. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of the relative mRNA expression of ATP1A1, ATP1B1 and α-SMA in DPSCs after coculture for 24 and 48 hours. (B) Western blot analysis of the expression of ATP1A1, and α-SMA in DPSCs after coculture for 24 and 48 hours. (C-D) Representative immunofluorescence images of α-SMA (green) and DAPI (blue) in HUVECs after coculture for 2 days. Scale bar = 50 μm. (E-F) Microscopy images showed the location of ATP1A1 and α-SMA in direct coculture. Scale bar = 50 μm. Data are mean ± SD for n = 3 replicates, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

To verify the vasculogenic differentiation potential of DPSCs and the relationship between ATP1A1 and α-SMA, immunofluorescence staining of ATP1A1 and α-SMA was performed on DPSCs before and after coculture. At the 48-hour time point, immunofluorescence results indicated that ATP1A1 fluorescence enhancement was predominantly localised to cell-cell contact regions along the plasma membrane in the coculture group (Figures 3G, 4E). In the direct coculture cells, immunofluorescence staining for ATP1A1 (green) and α-SMA (red) showed that α-SMA was primarily localised in the nucleus, with fluorescence signals of ATP1A1 in the contact areas between cells. A marked increase in α-SMA fluorescence intensity was observed in the direct coculture group at this same time, as shown in Figure 4D.

Inhibition of ATP1A1 reduces DPSCs’ differentiation in vitro

To evaluate whether ATP1A1 plays a role in the induction of pericyte-like differentiation in DPSCs after contact with HUVECs. DPSCs were treated with 3 μM of ouabain for 48 hrs. The results showed that the expression of both ATP1A1 and α-SMA significantly decreased. To confirm the successful transfection and evaluate the knockdown efficiency, fluorescence imaging was performed on cells following siRNA treatment, as shown in Figure 5D. The images indicate effective transfection across all experimental groups while demonstrating the preservation of consistent cellular morphology throughout the procedure. Consistent with the pharmacological inhibition results, RNA interference of ATP1A1 using specific siRNA led to similar effects. Three small interfering RNAs targeting ATP1A1 were used to knock down its expression in DPSCs. Following ATP1A1 knockdown, we observed a significant decrease in the mRNA expression of α-SMA and activin A (Figures 5A-D). Western blot analysis revealed a significant reduction in ATP1A1 protein levels, coinciding with decreased expression of pericyte-related markers like NG2, compared to negative control (Figures 5E-F). In contrast, the expression levels of desmin and α-SMA remained relatively unchanged. Meanwhile, a notable decrease in FGF-2 expression was detected in DPSCs.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of ATP1A1 suppresses the expression of SMC markers in DPSCs. (A-D) RT-qPCR analysis of the relative expression of ATP1A1, α-SMA and activin A in cells after siRNA transfection. Representative fluorescence images of cells after siRNA transfection. Images were captured at 48 hours post-transfection to visualise transfection efficiency and cell morphology. (E-F) Western blot analysis of the relative expression of proteins in cells after siRNA transfection. (G) The impact of ouabain treatment on DPSCs. (H-J) Ouabain inhibited HUVEC migration and tube formation. Data are mean ± SD for n = 3 replicates, *P < .05, ***P < .001, Scale Bar = 100 μm.

Suppression of tube formation and HUVECs migration by ATP1A1 inhibitor

Since tube morphogenesis is critical in forming blood vessels, we assessed the influence of ATP1A1 on the tubulogenesis of HUVECs. After treating the cells with different concentrations of ATP1A1 protein inhibitor ouabain (Figure 5G), we observed that 1-3 μM ouabain concentrations significantly inhibited tube formation (Figure 5H). To further assess the effect of ATP1A1 on EC migration, a wound-healing assay was performed. The assay revealed a markedly reduced rate of EC migration into the scratch area following the ouabain treatment compared to cell culture in a normal medium (Figures 5I, 5J).

To further investigate the functional role of ATP1A1 in endothelial cell behaviour, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of ATP1A1 and assessed its effects on HUVEC tube formation and migration (Supplementary Figure S2). Notably, ATP1A1 knockdown alone did not significantly impair these functions. However, when ATP1A1 was functionally inhibited through Ouabain binding, both tube formation and migration were significantly reduced (P < .01).

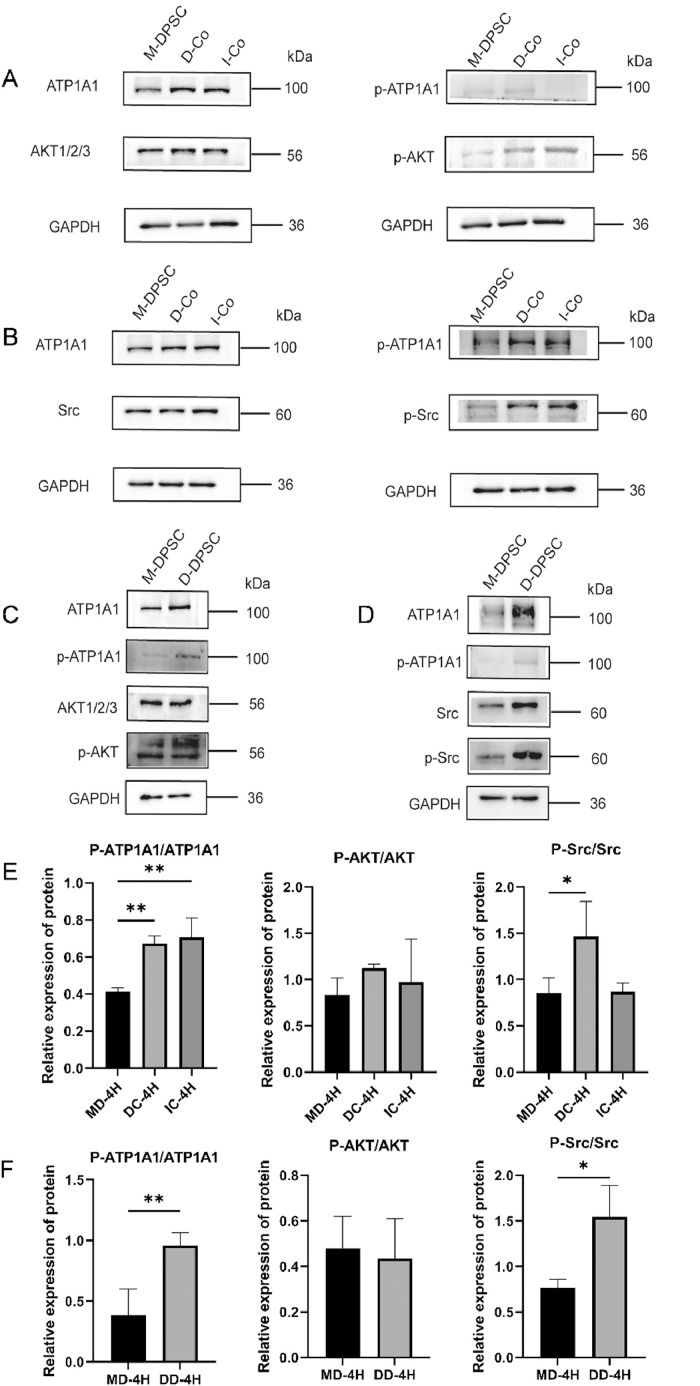

ATP1A1/Src/AKT signalling is activated in DPSCs by contacting with HUVECs

To identify potential downstream mechanisms of ATP1A1 action, we performed pathway enrichment analysis on RNA sequencing data from differentiating DPSCs into SMCs (Supplementary Figure S1D-E). This analysis revealed significant enrichment of genes involved in PI3K/AKT and MAPK signalling pathways. A comprehensive literature review further indicated that ATP1A1 frequently exerts its effects through Src-mediated mechanisms. Notably, previous studies have demonstrated that the Src/AKT signalling pathway plays a critical role in mediating ATP1A1 functions during glioma progression.31 Based on this convergent evidence from our enrichment analysis and previously published findings, we selected the Src/AKT signalling pathway for further investigation in our DPSC differentiation model. To assess the phosphorylation status of ATP1A1 and Src/AKT, total protein was extracted from separately cultured cells, directly cocultured, and indirectly cocultured cells. Western blot analysis revealed distinct changes in signalling pathway activation after a 4-hour coculture of DPSCs with HUVECs. It is important to note that the observed phosphorylation changes were measured after 4 hours of co-culture, representing early signalling events, in contrast to the changes in total ATP1A1 protein levels observed after 48 hours of co-culture (Figure 3). Prior to coculture, DPSCs exhibited baseline levels of phosphorylated ATP1A1 (p-ATP1A1). Following the 4-hour coculture period, phosphorylated ATP1A1 and AKT levels were increased in both DPSCs and the total direct coculture group (Figures 6A-F).

Fig. 6.

Involvement of Src/AKT pathway in HUVECs/DPSCs direct coculture. (A-B) Effects of ATP1A1 on the phosphorylation status of AKT and Src after coculture. (C-D) Effects of ATP1A1 on the phosphorylation status of AKT and Src in DPSCs. (E-F) Semi-quantitative analysis of the phosphorylation and total protein after coculture. Data are mean ± SD for n = 3 replicates, *P < .05, **P < .01.

Discussion

The physical interaction between ECs and MSCs serves as a crucial microenvironmental cue that guides MSCs toward the pericyte phenotype.9,13,32 Various MSCs have been studied, including bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells,33,34 adipose-derived MSCs,35,36 stem cells from the apical papilla.37 In this study, direct cellular interactions between DPSCs and HUVECs were investigated in an in vitro coculture model. It was found that DPSCs were induced to differentiate into pericyte-like cells by activating ATP1A1 and promoting the secretion of FGF-2 through Src and AKT phosphorylation, which signalling is closely related to cell migration and proliferation in several biological processes like angiogenesis and protein transport.38, 39, 40, 41

Heterogeneous cells in vitro coculture systems are widely utilised to replicate cell-cell communication within the in vivo cellular microenvironment.42 MSCs/ECs coculture has been shown to influence the angiogenesis process through multiple stages and mechanisms. Direct cell-cell contact between MSCs and ECs is essential for initiating angiogenic differentiation, where MSCs serve as pericyte precursors.43,44 This interaction induces the expression of pericyte markers like α-SMA and NG2, mediated by key signalling molecules, including PDGF-BB secreted by ECs and TGF-β signalling pathways.9,28,40,45 Long-term vessel stabilisation is achieved through MSC differentiation into pericyte-like cells, which provide structural support and maintain vessel integrity.46 Multiple signalling pathways coordinate this process, including VEGF promoting EC proliferation, PDGF-BB recruiting pericyte precursors, and FGF-2 stimulating EC migration.34,36,47 This study found that the conditioned medium extracted from the initial 48 hours of the direct coculture system facilitates the maintenance of the formed tube. Direct coculture markedly enhanced pericyte differentiation and maintained vascular stability during the early stages of formation, in contrast to indirect coculture. This is supported by the increased expression of key pericyte markers, including α-SMA and NG2 (Figures 3, 4, and 5). The mRNA expression levels of α-SMA at 24 and 48 hours and 7 days were notably higher in the direct coculture group compared to the indirect coculture group. Immunofluorescence analysis also revealed a marked increase in α-SMA intensity after direct coculture (Figure 4). This trend is consistent with some previous studies, which reported that DPSCs have moderate pericyte differentiation potential, showing higher expression of α-SMA when cocultured with ECs, and this process requires direct cell-cell contact rather than just paracrine signalling,9,48 indicating that the differentiation of DPSCs toward pericyte was, to some extent, regulated by direct contact with ECs.9

It is noteworthy that ATP1A1 exhibits a significant alteration between the two culture systems over the continuous 48-hour period in DPSCs, suggesting its potentially divergent roles in modulating cell differentiation during the initial stages. A previous study revealed that ATP1A1 binding triggered activin A secretion from fibroblasts, which upregulated their α-SMA expression and promoted fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transformation.35 Mature ECs from different blood vessels drive smooth muscle cells toward contractile and synthetic phenotype,49 while disrupting ATP1A1 binding diminishes their phenotype change.50,51 These studies have demonstrated that ATP1A1 binding between different cell types can induce cellular differentiation, which provided valuable insights for our investigation. Interestingly, our findings revealed that merely knocking down ATP1A1 in HUVECs did not significantly exert a significant impact on the tubulogenesis or migration capabilities of endothelial cells. However, treatment with a specific ATP1A1 inhibitor remarkably reduced the angiogenic capacity of endothelial cells in vitro. This discrepancy can be attributed to the mechanism of Ouabain, which inhibits ATP1A1 function by binding to specific domains of the ATP1A1 protein. These findings indicated that ATP1A1 may influence angiogenesis specifically when its protein binding sites are engaged, rather than simply through its expression level. The distinct effects observed between gene knockdown and pharmacological inhibition highlight the intricate role of ATP1A1 in angiogenesis regulation. Our findings suggest a potential protein-protein interaction mechanism wherein ATP1A1 may function as a signalling platform to modulate endothelial cell behavior during angiogenesis.12,51,52 This provides a novel direction for future investigations aimed at identifying the specific binding partners and signalling pathways involved in ATP1A1-mediated regulation of vascular formation.

The data showed parallel expression patterns of ATP1A1 and α-SMA during the first 48-hour period (Figure 4). ATP1A1, a significant subunit of Na+/K+ ATPase, has been previously studied as both a transporter53, 54, 55, 56 and a drug receptors.57, 58, 59, 60 In recent years, research has focused on its immunological functions, especially in cell adhesion and signal transduction.20,38,61, 62, 63, 64, 65 It has been confirmed that ATP1A1 facilitates the unconventional secretion of FGF-2 and functions upstream in membrane translocation.66 These processes are crucial for vascular development and maintenance. Indeed, FGF-2 modulates the differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs) toward pericyte-like phenotype through its regulation of α-SMA expression, thereby promoting the development of cells with characteristics more closely resembling natural pericytes, which are characterised by low levels of α-SMA.36 Our data suggest that within the initial 48 hrs, DPSCs predominantly differentiate into a proliferative phenotype, potentially influenced by increased secretion of FGF-2. In fact, studies have demonstrated that FGF-2 promoted DPSCs proliferative capacity67 and angiogenic differentiation in vitro,68, 69, 70 contributing to enhanced stabilisation of vessel tubes via increased coverage by pericyte-like cells.71 Some studies have demonstrated that after 4 days, endothelial-secreted TGF-β and PDGF could induce pericyte phenotype switching, characterised by increased α-SMA expression.32,40,72 In an experiment exploring myofibroblast differentiation, the upregulation of FGF-2 leads to increased TGF-β1 expression; moreover, inhibiting either FGF-2 or TGF-β1 expression blocks 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE) induced α-SMA expression.73 It has been reported that activin A can strongly induce the expression of smooth muscle differentiation markers like α-SMA, calponin, and SM22α through a different mechanism from TGF-β1-mediated regulation.74,75 However, this study noted that neither TGF-β nor activin A serves as the primary initiating signalling molecules in the process where ECs trigger ASCs to differentiate into SMCs.32 Intriguingly, we found that the expression of ATP1A1 was upregulated in the direct coculture system, functioning as an adhesion molecule during ECs-DPSCs contact within the first 2 days. Additionally, the levels of FGF-2 and activin A may play a critical role in influencing early pericyte differentiation.

After inhibiting the activity of the ATP1A1 protein with ouabain, a significant decrease in α-SMA expression was observed, along with a marked suppression of tube formation capability in ECs. Furthermore, siRNA-mediated knockdown of ATP1A1 led to reduced mRNA expression of activin A and decreased expression of SMC-specific markers in DPSCs (Figure 5). These findings suggested an essential role for ATP1A1 in differentiating DPSCs into SMCs. The current study revealed the transient effects of active ATP1A1 forms on signal transduction, which may influence blood vessel stability. Prior to this study, ATP1A1 was primarily recognised for its role in regulating the secretion of proangiogenic factors during processes such as tumour formation, cell proliferation, and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).31,76, 77, 78, 79 Further evidence supporting a critical role for ATP1A1 in this coculture system is presented by the findings that re-establishing coculture conditions ameliorated the siRNA-induced deficiency in SMC differentiation. This finding provides new insights into the molecular mechanisms governing pericyte differentiation and vessel stabilisation. The divergent effects observed between ATP1A1 knockdown and functional inhibition highlight the complex role of this protein in endothelial function. Our findings suggest that ATP1A1 mediates endothelial tube formation and migration through specific binding site interactions and cell-cell contacts, rather than through overall expression levels alone, which aligns with our proposed mechanism.

Mechanistically, AKT and Src signalling pathways were activated in this coculture system. Our results showed that ATP1A1 regulated cell differentiation through a direct contact mechanism involving the phosphorylation of AKT and Src (Figure 6). The ATP1A1 protein has proven to be a key component of tight junctions in polarised epithelial cells and exhibits a unique response to second messenger signalling.80 Numerous regulators of protein phosphorylation have been implicated in this process. Previous studies have shown that ATP1A1 could enhance cell proliferation and survival via an Src-dependent mechanism in some tumour cells.21,31,64,65,78 Specifically, the interaction between ATP1A1 and Src, whether direct or indirect, leads to Src phosphorylation, which promotes cancer progression by activating the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signalling pathways. Similarly, we found that Src and AKT phosphorylation are critical for pericyte-like cell differentiation, especially influencing the expression of NG2 and α-SMA in DPSCs. These findings advance our understanding of the complex cellular interactions necessary for stable vessel formation. Further studies will be required to identify the specific mechanisms of ATP1A1 regulation after direct coculture.

Despite using commercially available primary DPSCs verified for stemness properties (Supplementary Figure S1), these cells have inherent limitations. They originate from a restricted donor pool, potentially lacking the full spectrum of genetic and epigenetic diversity. Commercial processing and multiple passages may alter cellular characteristics. Limited donor demographic information constrains the broader contextualisation of our findings. However, commercial primary cells offer consistency, rigorous quality control, and batch-to-batch reproducibility, which facilitates experimental replication across various studies.

Our study, for the first time, explored the role of ATP1A1 in guiding dental stem cells toward a specific phenotype within a fully integrated HUVECs/DPSCs coculture model, which is essential to vascular stabilisation. The HUVECs/DPSCs coculture model provides a valuable tool for studying the molecular mechanisms underlying pericyte differentiation and vessel stabilisation.

The molecular mechanisms of DPSC-endothelial cell interactions elucidated in this study have direct implications for the development of dental pulp regeneration strategies. Successful pulp regeneration requires not only the differentiation of stem cells into pulp-specific cell types but also the establishment of a functional and robust vascular network. Our findings regarding ATP1A1′s role in mediating critical intercellular interactions offer valuable insights that could guide the development of improved regenerative endodontic approaches. For instance, biomaterial scaffolds could be functionalised to enhance ATP1A1-mediated signalling between transplanted DPSCs and host vasculature, potentially improving angiogenesis and tissue integration during pulp revitalisation procedures. Furthermore, pharmacological modulation of the identified signalling pathways may provide new avenues for enhancing the regenerative capacity of dental pulp cells in clinical applications. However, the long-term stability of these cells under diverse stress conditions requires further characterisation. Additionally, the current system may not fully recapitulate all aspects of the native vascular microenvironment, such as the influence of inflammatory cells and mechanical forces.4 Moreover, the precise timing and dosing of various signalling molecules in the coculture system need to be optimised for different applications. Future studies should focus on elucidating the temporal dynamics of signalling pathway activation during SMC differentiation.

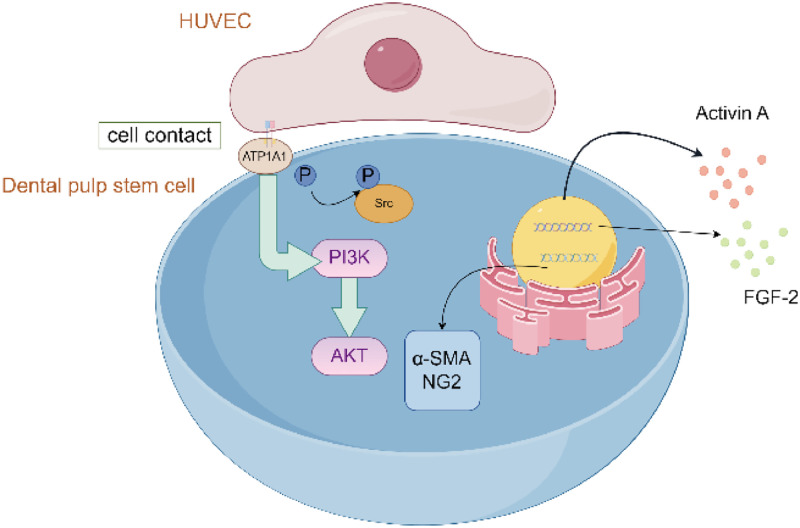

Conclusion

In conclusion, we propose that ATP1A1 acts as an initiation point for activating signalling pathways following direct cell contact by inducing Src/AKT activation and secretion of FGF-2 and activin A (Figure 7). Elucidating the direct coculture effects of ECs and DPSCs during the initial contact stage may facilitate rapid vascularisation and inform strategies aimed at pulp tissue regeneration.

Fig. 7.

Proposed model of cell interactions through ATP1A1 promotes SMC activation for vascular stability. Cell interactions between DPSCs and HUVECs induce ATP1A1 over-expression, leading to SMC differentiation, Src/AKT activation and activin A, FGF-2 secretion. The schematic diagram of mechanism was generated by Figdraw.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mingqi Zhu: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Data curation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Shan Jiang: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis. Chengfei Zhang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Buling Wu: Supervision, Resources, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Ting Zou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Data availability

Availability of data and materials: Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. The RNA-seq datasets generated and analysed in this study are available in the NCBI SRA repository with the primary accession code PRJNA1240367 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1240367).

Funding

This work was supported by the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82401081), the President’s fund of Southern Medical University Shenzhen Stomatology Hospital (Pingshan) (Grant No. 714011 and No. 2024B001) and Shenzhen Natural Science Foundation for Basic Research (Grant No. 20230807154303008). The authors acknowledge the financial support from funding agencies.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.identj.2025.100870.

Contributor Information

Buling Wu, Email: bulingwu@smu.edu.cn.

Ting Zou, Email: zouting0818@163.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Zhang S., Zhang W., Li Y., et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell differentiation into odontoblast-like cells and endothelial cells: a potential cell source for dental pulp tissue engineering. Front Physiol. 2020;11:593. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambrichts I., Driesen R.B., Dillen Y., et al. Dental pulp stem cells: their potential in reinnervation and angiogenesis by using scaffolds. J Endod. 2017;43(9S):S12–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xuan K., Li B., Guo H., et al. Deciduous autologous tooth stem cells regenerate dental pulp after implantation into injured teeth. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(455) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novosel E.C., Kleinhans C., Kluger PJ. Vascularization is the key challenge in tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63(4-5):300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorin C., Rochefort G.Y., Bascetin R., et al. Priming dental pulp stem cells with fibroblast growth factor-2 increases angiogenesis of implanted tissue-engineered constructs through hepatocyte growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor secretion. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5(3):392–404. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattei V., Martellucci S., Pulcini F., et al. Regenerative potential of DPSCs and revascularization: direct, paracrine or autocrine effect? Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2021;17(5):1635–1646. doi: 10.1007/s12015-021-10162-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovina M.V., Dyuzheva T.G., Krasheninnikov M.E., Yakovenko S.A., Khodarovich YM. Co-growth of stem cells with target tissue culture as an easy and effective method of directed differentiation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.591775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dissanayaka W.L., Zhan X., Zhang C., Hargreaves K.M., Jin L., Tong EHY. Coculture of dental pulp stem cells with endothelial cells enhances osteo-/odontogenic and angiogenic potential in vitro. J Endod. 2012;38(4):454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Zhong J., Lin S., et al. Direct contact with endothelial cells drives dental pulp stem cells toward smooth muscle cells differentiation via TGF-β1 secretion. Int Endodontic J. 2023 doi: 10.1111/iej.13943. iej.13943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janebodin K., Zeng Y., Buranaphatthana W., Ieronimakis N., Reyes M. VEGFR2-dependent angiogenic capacity of pericyte-like dental pulp stem cells. J Dent Res. 2013;92(6):524–531. doi: 10.1177/0022034513485599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piard C., Jeyaram A., Liu Y., et al. 3D printed HUVECs/MSCs cocultures impact cellular interactions and angiogenesis depending on cell-cell distance. Biomaterials. 2019;222 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dissanayaka W.L., Zhan X., Zhang C., Hargreaves K.M., Jin L., Tong EHY. Coculture of dental pulp stem cells with endothelial cells enhances osteo-/odontogenic and angiogenic potential in vitro. J Endod. 2012;38(4):454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y., Liu J., Zou T., et al. DPSCs treated by TGF-β1 regulate angiogenic sprouting of three-dimensionally co-cultured HUVECs and DPSCs through VEGF-Ang-Tie2 signaling. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):281. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02349-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caviedes-Bucheli J., Gomez-Sosa J.F., Azuero-Holguin M.M., Ormeño-Gomez M., Pinto-Pascual V., Munoz HR. Angiogenic mechanisms of human dental pulp and their relationship with substance P expression in response to occlusal trauma. Int Endod J. 2017;50(4):339–351. doi: 10.1111/iej.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shafiee S., Shariatzadeh S., Zafari A., Majd A., Niknejad H. Recent advances on cell-based co-culture strategies for prevascularization in tissue engineering. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.745314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y., Lin S., Liu J., et al. Ang1/Tie2/VE-cadherin signaling regulates DPSCs in vascular maturation. J Dent Res. 2024;103(1):101–110. doi: 10.1177/00220345231210227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baccouche B., Lietuvninkas L., Kazlauskas A. Activin a limits VEGF-induced permeability via VE-PTP. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(10):8698. doi: 10.3390/ijms24108698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q., Xie Y., Rice R., Maverakis E., Lebrilla CB. A proximity labeling method for protein-protein interactions on cell membrane. Chem Sci. 2022;13(20):6028–6038. doi: 10.1039/d1sc06898a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalaf F.K., Tassavvor I., Mohamed A., et al. Epithelial and endothelial adhesion of immune cells is enhanced by cardiotonic steroid signaling through Na + /K + -ATPase-α-1. JAHA. 2020;9(3) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajamanickam G.D., Kastelic J.P., Thundathil JC. The ubiquitous isoform of Na/K-ATPase (ATP1A1) regulates junctional proteins, connexin 43 and claudin 11 via Src-EGFR-ERK1/2-CREB pathway in rat Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod. 2017;96(2):456–468. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.116.141267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobuke K., Oki K., Gomez-Sanchez C.E., et al. ATP1A1 mutant in aldosterone-producing adenoma leads to cell proliferation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(20) doi: 10.3390/ijms222010981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swift F., Birkeland J.A.K., Tovsrud N., et al. Altered Na+/Ca2+-exchanger activity due to downregulation of Na+/K+-ATPase alpha2-isoform in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78(1):71–78. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La Venuta G., Zeitler M., Steringer J.P., Müller H.M., Nickel W. The startling properties of fibroblast growth factor 2: how to exit mammalian cells without a signal peptide at hand. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(45):27015–27020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.689257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C., Dai X., Wu S., Xu W., Song P., Huang K. FUNDC1-dependent mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes are involved in angiogenesis and neoangiogenesis. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2616. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22771-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gharaei M.A., Xue Y., Mustafa K., Lie S.A., Fristad I. Human dental pulp stromal cell conditioned medium alters endothelial cell behavior. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0815-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dudley A.C., Griffioen AW. Pathological angiogenesis: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Angiogenesis. 2023;26(3):313–347. doi: 10.1007/s10456-023-09876-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eguchi R., Kawabe J.I., Wakabayashi I. VEGF-independent angiogenic factors: beyond VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling. J Vasc Res. 2022;59(2):78–89. doi: 10.1159/000521584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vimalraj S. A concise review of VEGF, PDGF, FGF, Notch, angiopoietin, and HGF signalling in tumor angiogenesis with a focus on alternative approaches and future directions. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;221:1428–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zacherl S., La Venuta G., Müller H.M., et al. A direct role for ATP1A1 in unconventional secretion of fibroblast growth factor 2. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(6):3654–3665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.590067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan C., Wang P., Zhu L., et al. Coculture of stem cells from apical papilla and human umbilical vein endothelial cell under hypoxia increases the formation of three-dimensional vessel-like structures in vitro. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21(5-6):1163–1172. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2014.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu Y., Chen C., Huo G., et al. ATP1A1 integrates AKT and ERK signaling via potential interaction with src to promote growth and survival in glioma stem cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:320. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geevarghese A., Herman IM. Pericyte-endothelial crosstalk: implications and opportunities for advanced cellular therapies. Transl Res. 2014;163(4):296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva A.S., Santos L.F., Mendes M.C., Mano JF. Multi-layer pre-vascularized magnetic cell sheets for bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2020;231 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin R.Z., Moreno-Luna R., Li D., Jaminet S.C., Greene A.K., Melero-Martin JM. Human endothelial colony-forming cells serve as trophic mediators for mesenchymal stem cell engraftment via paracrine signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(28):10137–10142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405388111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X., Aledia A.S., Popson S.A., Him L., Hughes C.C.W., George SC. Rapid anastomosis of endothelial progenitor cell-derived vessels with host vasculature is promoted by a high density of cotransplanted fibroblasts. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(2):585–594. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mannino G., Gennuso F., Giurdanella G., et al. Pericyte-like differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells: an in vitro study. World J Stem Cells. 2020;12(10):1152–1170. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i10.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savkovic V., Li H., Obradovic D., et al. The angiogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells from the hair follicle outer root sheath. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):911. doi: 10.3390/jcm10050911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khalaf F.K., Dube P., Kleinhenz A.L., et al. Proinflammatory effects of cardiotonic steroids mediated by NKA α-1 (na+/K+-ATPase α-1)/src complex in renal epithelial cells and immune cells. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979) 2019;74(1):73–82. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Ma J.C., Sun X.W., Su H., et al. Fibroblast-derived CXCL12/SDF-1α promotes CXCL6 secretion and co-operatively enhances metastatic potential through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(28):5167–5178. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i28.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papetti M., Shujath J., Riley K.N., Herman IM. FGF-2 antagonizes the TGF-β1-mediated induction of pericyte α-smooth muscle actin expression: a role for myf-5 and smad-mediated signaling pathways. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(11):4994–5005. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Sun Q, Ye Y, et al. FGF-2 signaling in nasopharyngeal carcinoma modulates pericyte-macrophage crosstalk and metastasis. JCI Insight. 7(10):e157874. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.157874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Yoo J., Jung Y., Char K., Jang Y. Advances in cell coculture membranes recapitulating in vivo microenvironments. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41(2):214–227. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loibl M., Binder A., Herrmann M., et al. Direct cell-cell contact between mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells induces a pericyte-like phenotype in vitro. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/395781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joensuu K., Uusitalo-Kylmälä L., Hentunen T.A., Heino TJ. Angiogenic potential of human mesenchymal stromal cell and circulating mononuclear cell cocultures is reflected in the expression profiles of proangiogenic factors leading to endothelial cell and pericyte differentiation. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12(3):775–783. doi: 10.1002/term.2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurpinski K., Lam H., Chu J., et al. Transforming growth factor-beta and notch signaling mediate stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28(4):734–742. doi: 10.1002/stem.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armulik A., Genové G., Betsholtz C. Pericytes: Developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell. 2011;21(2):193–215. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaengel K., Genové G., Armulik A., Betsholtz C. Endothelial-mural cell signaling in vascular development and angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(5):630–638. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parthiban S.P., He W., Monteiro N., Athirasala A., França C.M., Bertassoni LE. Engineering pericyte-supported microvascular capillaries in cell-laden hydrogels using stem cells from the bone marrow, dental pulp and dental apical papilla. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78176-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin C.H., Lilly B. Endothelial cells direct mesenchymal stem cells toward a smooth muscle cell fate. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23(21):2581–2590. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang M., Wang X., Banerjee M., et al. Regulation of myogenesis by a na/K-ATPase α1 caveolin-binding motif. Stem Cells. 2022;40(2):133–148. doi: 10.1093/stmcls/sxab012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X., Cai L., Xie J.X., et al. A caveolin binding motif in na/K-ATPase is required for stem cell differentiation and organogenesis in mammals and C. elegans. Sci Adv. 2020;6(22):eaaw5851. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruan Q., Tan S., Guo L., Ma D., Wen J. Prevascularization techniques for dental pulp regeneration: potential cell sources, intercellular communication and construction strategies. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1186030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Čechová P., Berka K., Kubala M. Ion pathways in the Na+/K+-ATPase. J Chem Inf Model. 2016;56(12):2434–2444. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bandulik S. Of channels and pumps: different ways to boost the aldosterone? Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2017;220(3):332–360. doi: 10.1111/apha.12832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li S., Jiang X., Luo Y., et al. Sodium/calcium overload and Sirt1/Nrf2/OH-1 pathway are critical events in mercuric chloride-induced nephrotoxicity. Chemosphere. 2019;234:579–588. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clausen M.V., Hilbers F., Poulsen H. The structure and function of the Na,K-ATPase isoforms in health and disease. Front Physiol. 2017;8:371. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akimova O.A., Tverskoi A.M., Smolyaninova L.V., et al. Critical role of the α1-Na(+), K(+)-ATPase subunit in insensitivity of rodent cells to cytotoxic action of ouabain. Apoptosis. 2015;20(9):1200–1210. doi: 10.1007/s10495-015-1144-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang C.J., Zhang C.Y., Zhao Y.K., et al. Bufalin inhibits tumorigenesis and SREBP-1-mediated lipogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma via modulating the ATP1A1/CA2 axis. Am J Chin Med. 2023;51(2):461–485. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X23500246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elkareh J., Kennedy D.J., Yashaswi B., et al. Marinobufagenin stimulates fibroblast collagen production and causes fibrosis in experimental uremic cardiomyopathy. Hypertension. 2007;49(1):215–224. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252409.36927.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang X., Yao Z., Xue Z., et al. Resibufogenin targets the ATP1A1 signaling cascade to induce G2/M phase arrest and inhibit invasion in glioma. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.855626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakamura K., Shiozaki A., Kosuga T., et al. The expression of the alpha1 subunit of Na+/K+-ATPase is related to tumor development and clinical outcomes in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2021;24(6):1278–1292. doi: 10.1007/s10120-021-01212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rajan P.K., Udoh U.A.S., Nakafuku Y., Pierre S.V., Sanabria J. Normalization of the ATP1A1 signalosome rescinds epigenetic modifications and induces cell autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cells. 2023;12(19):2367. doi: 10.3390/cells12192367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang K., Li Z., Chen Y., et al. Na, K-ATPase α1 cooperates with its endogenous ligand to reprogram immune microenvironment of lung carcinoma and promotes immune escape. Sci Adv. 2023;9(6):eade5393. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.ade5393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khalaf Fk., Tassavvor I., Mohamed A., et al. Epithelial and endothelial adhesion of immune cells is enhanced by cardiotonic steroid signaling through na+/K+-ATPase-α-1. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(3) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang D., Zhang P., Yang P., et al. Downregulation of ATP1A1 promotes cancer development in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Proteomics. 2017;14:15. doi: 10.1186/s12014-017-9150-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Biadun M., Sochacka M., Kalka M., et al. Uncovering key steps in FGF12 cellular release reveals a common mechanism for unconventional FGF protein secretion. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81(1):356. doi: 10.1007/s00018-024-05396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim J., Park J.C., Kim S.H., et al. Treatment of FGF-2 on stem cells from inflamed dental pulp tissue from human deciduous teeth. Oral Dis. 2014;20(2):191–204. doi: 10.1111/odi.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.He H., Yu J., Liu Y., et al. Effects of FGF2 and TGFbeta1 on the differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells in vitro. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32(7):827–834. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gorin C., Rochefort G.Y., Bascetin R., et al. Priming dental pulp stem cells with fibroblast growth factor-2 increases angiogenesis of implanted tissue-engineered constructs through hepatocyte growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor secretion. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5(3):392–404. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sagomonyants K., Mina M. Stage-specific effects of FGF2 on the differentiation of dental pulp cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 2014;199(0):311–328. doi: 10.1159/000371343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hosaka K., Yang Y., Nakamura M., et al. Dual roles of endothelial FGF-2–FGFR1–PDGF-BB and perivascular FGF-2–FGFR2–PDGFRβ signaling pathways in tumor vascular remodeling. Cell Discov. 2018;4(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41421-017-0002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Méndez-Barbero N., Gutiérrez-Muñoz C., Blanco-Colio LM. Cellular crosstalk between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vascular wall remodeling. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(14):7284. doi: 10.3390/ijms22147284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang L., Chen Y., Li G., et al. TGF-β1/FGF-2 signaling mediates the 15-HETE-induced differentiation of adventitial fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:2 doi: 10.1186/s12944-015-0174-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Merfeld-Clauss S., Lupov I.P., Lu H., et al. Adipose stromal cells differentiate along a smooth muscle lineage pathway upon endothelial cell contact via induction of activin a. Circ Res. 2014;115(9):800–809. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamashita S., Maeshima A., Kojima I., Nojima Y. Activin a is a potent activator of renal interstitial fibroblasts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(1):91–101. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000103225.68136.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Feng X., Li J., Li H., Chen X., Liu D., Li R. Bioactive C21 steroidal glycosides from euphorbia kansui promoted HepG2 cell apoptosis via the degradation of ATP1A1 and inhibited macrophage polarization under co-cultivation. Molecules. 2023;28(6):2830. doi: 10.3390/molecules28062830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen Y.I., Chang C.C., Hsu M.F., et al. Homophilic ATP1A1 binding induces activin A secretion to promote EMT of tumor cells and myofibroblast activation. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):2945. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30638-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Feng X.Y., Zhao W., Yao Z., Wei N.Y., Shi A.H., Chen WH. Downregulation of ATP1A1 Expression by Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen Saponins: a potential mechanism of antitumor effects in HepG2 cells and in vivo. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.720368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.So S., Park Y., Kang S.S., et al. Therapeutic potency of induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived corneal endothelial-like cells for corneal endothelial dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24(1):701. doi: 10.3390/ijms24010701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang Y., Dai M., Wilson T.M., et al. Na+/K+-ATPase α1 identified as an abundant protein in the blood-labyrinth barrier that plays an essential role in the barrier integrity. PLoS One. 2011;6(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Availability of data and materials: Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. The RNA-seq datasets generated and analysed in this study are available in the NCBI SRA repository with the primary accession code PRJNA1240367 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1240367).