Abstract

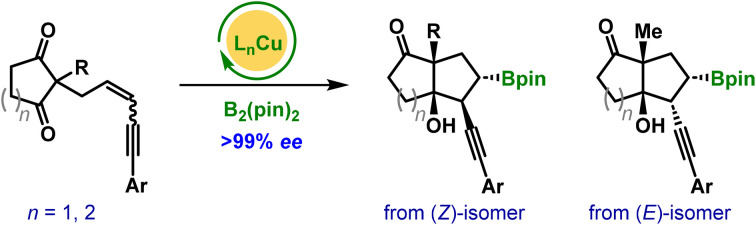

A copper(i)-catalyzed, highly enantioselective, and diastereoselective borylative cyclization of prochiral cyclic 1,3-dione-tethered 1,3-enynes is reported. This stereospecific transformation exhibits a broad substrate scope, enabling access to bicyclic organoboron products containing four contiguous stereocenters with excellent enantioselectivity. Notably, the reaction rate is significantly influenced by the substrate's stereochemistry, with the (Z)-isomer undergoing borylative cyclization much faster than the (E)-isomer due to reduced steric interactions during C–C bond formation. Furthermore, treatment of the resulting products with sodium perborate yields the corresponding alcohols without compromising enantiomeric excess.

A copper(i)-catalyzed, highly enantioselective, and diastereoselective borylative cyclization of prochiral cyclic 1,3-dione-tethered 1,3-enynes is reported.

Introduction

Conjugated enynes are highly reactive and valuable substrates in modern organic chemistry, widely utilized in the synthesis of complex aromatic molecules and materials.1 While 1,3-enyne motifs can be readily accessed through several efficient methods, the catalytic cross-coupling of terminal alkynes stands out as the most convenient approach.2 Recently, copper-catalyzed hydro- and borofunctionalizations, multicomponent reactions, radical functionalizations, and cyclizations of these π-systems have garnered significant attention from organic and medicinal chemists.3 Among these methods, enantioselective Cu-catalyzed borylation of 1,3-enynes has also emerged as an elegant strategy, providing access to a diverse range of chiral organoboranes.4 The resulting C–B bonds can be conveniently converted into C–C, C–O, and C–N bonds through stereospecific 1,2-migration.5 However, achieving asymmetric chemo- and regioselective borylative difunctionalization of 1,3-enynes remains highly challenging due to the presence of multiple reactive sites.

In general, two pathways are possible for 1,3-enynes during hydro- or borofunctionalization. The reaction at the olefin can yield propargyl or allene products via the ene-pathway (Scheme 1a), whereas the reaction at the alkyne results in diene products through the yne-pathway.3 In 2011, Ito and co-workers reported that the regioselectivity of borocupration is influenced by the nature of the ligand employed in the reaction and steric hindrance around the olefinic functionality of the enyne.6 The first enantioselective Cu-catalyzed borylative 1,2-difunctionalization of 1,3-enynes was reported by the Hoveyda group in 2014 via the ene-pathway (Scheme 1b).7 The borocupration of 1,3-enynes enables the formation of a chiral allenylcopper complex, which is readily captured by aldehydes to provide propargylated products with excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivities. In light of this report, Yin and co-workers disclosed similar consecutive protocols on ketones.8 Later, Procter and co-workers disclosed a highly enantio- and diastereoselective borylative 1,2-coupling of 1,3-enynes with imines to provide chiral homopropargyl amines with excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity.9 Recently, Yun and co-workers reported a highly enantioselective 1,2-borylation/conjugate addition with β-substituted alkylidene malonates, enabling organoboranes bearing adjacent stereocentres.10 In 2020, Hu, Wang, Liao, and co-workers developed a cooperative Cu/Pd-catalyzed 1,4-boroarylation, wherein arylation occurs via transmetalation with palladium to access chiral tri- and tetra-substituted allenes.11 Shortly thereafter, Xu et al. reported the 1,4-boroprotonation of trifluoromethyl-substituted conjugated enynes to access enantioenriched homoallenyboronates.12 Similarly, CuH-catalyzed hydrofunctionalization of 1,3-enynes also allows the generation of chiral allenylcopper intermediates, which are readily captured by various electrophiles to yield the corresponding propargylic products and allenes with excellent stereoselectivities.13,14 Among these elegant methods, 1,2-borofunctionalization is generally limited to terminal 1,3-enynes, with only two reports9,10 exploring internal enynes due to their lower reactivity and other challenges related to regioselectivity and stereoselectivity. Here, E/Z-selectivity of the double bond controls the diastereoselectivity of the corresponding product in a stereospecific manner.

Scheme 1. Cu(i)-catalyzed borylative functionalization of 1,3-enyes.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no intramolecular cyclizations reported via Cu-catalyzed borylative 1,2-difunctionalization of 1,3-enynes with internal electrophiles. Based on our interest in the area of enantioselective Cu-catalysis,15 herein, we report a stereospecific annulation of 1,3-enyne-tethered cyclic 1,3-enones (Scheme 1c). This work describes an unprecedented intramolecular Cu(i)-catalyzed borylative difunctionalization of 1,3-enynes, delivering products with excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity. The E/Z configuration of the substrates significantly influences the reaction rate and diastereoselectivity of products. We envisioned that stereospecific syn-addition of a borylcopper(i) intermediate on the double bond of (Z/E)-1 could provide intermediate A/B. Subsequent intramolecular nucleophilic attack of organocuprate A/B could afford the corresponding product anti-2 or syn-2, respectively with the retention of the configuration at the C–B bond. Notably, the reaction proceeds through highly regioselective 1,2-borocupration on the double bond adjacent to the sterically demanding quaternary prochiral center.

Results and discussion

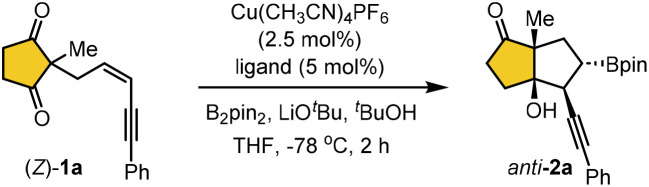

We began our investigation on Cu(i)-catalyzed borylative cyclization of Z-selective 1,3-enyne 1a as a model substrate in the presence of bis(pinacolato)diboron as the borylation source with various chiral bidentate phosphine ligands (Table 1). The reaction was initially conducted with 2.5 mol% of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6, 5 mol% of ligand, and 2.0 equivalents of base in THF at −78 °C for 2 hours. Notably, the BINAP ligands provided the desired product anti-2a in moderate yield with enantioselectivity ranging from 37% to 92%, whereas SEGPHOS ligands resulted in only trace amounts of the product (entries 1–5). In addition, the BDPP ligand L6, DUPHOS ligand L7, BIPHEP ligand L8, and iPr-BPE ligand L9 proved ineffective in the model reaction, resulting in no product formation. Fortunately, the reaction with (S,S)-Ph-BPE ligand L10 afforded 2a in high yield with excellent enantioselectivity (>99% ee). The exclusive diastereoselectivity suggests that the borylative cyclization of (Z)-1a proceeds with high stereocontrol. The relative stereochemistry of anti-2a was confirmed by single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (see Table 2).16

Table 1. Optimization of reaction conditionsa,b,c,d.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligand | Yield [%] | 2a (ee) |

| 1 | (R)-SEGPHOS, L1 | <5 | — |

| 2 | (S)-BINAP, L2 | 54 | 92% |

| 3 | (R)-Tol-BINAP, L3 | 36 | 69% |

| 4 | (S)-DM-SEGPHOS, L4 | <5 | — |

| 5 | (R)-DM-BINAP, L5 | 31 | 37% |

| 6 | (S,S)-BDPP, L6 | <5 | — |

| 7 | (R,R)-Me-DUPHOS, L7 | — | — |

| 8 | (R)-Cl-MeO-BIPHEP, L8 | — | — |

| 9 | (S,S)-iPr-BPE, L9 | — | — |

| 10 | (S,S)-Ph-BPE-L10 | 82% | >99% |

| |||

Reaction conditions: 1a (50 mg, 0.2 mmol), B2(pin)2 (60 mg, 0.24 mmol), Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (1.9 mg, 2.5 mol%), ligand (5.0 mol%), tBuOH (38 μL, 0.4 mmol), LiOtBu (36 μL, 0.4 mmol, 1.0 M THF solution), in THF solvent (3 mL, 0.1 M).

Isolated yields.

Enantiomeric ratio (er) was determined by HPLC analysis using a chiral stationary phase.

>20 : 1 dr was observed from 1H NMR analysis.

Table 2. Substrate scope of (Z)-isomera,b,c,d.

|

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.3 mmol), B2(pin)2 (91 mg, 0.36 mmol), Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (2.8 mg, 2.5 mol%), (S,S)-Ph-BPE (7.6 mg, 5.0 mol%), tBuOH (57 μL, 0.6 mmol), LiOtBu (54 μL, 0.6 mmol, 1.0 M THF solution), in THF solvent (3 mL, 0.1 M).

Isolated yields after column chromatography.

Enantiomeric ratio (er) was determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

>20 : 1 dr was observed (unless otherwise mentioned) through 1H NMR analysis of a crude reaction mixture. SM = Starting material.

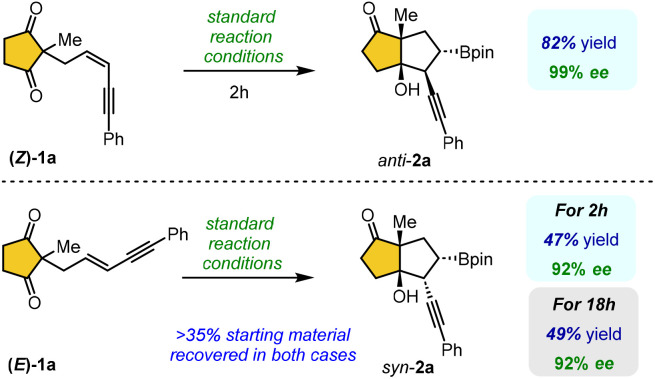

Under standard conditions, the borylative cyclization of 1,3-enyne (Z)-1a proceeded with complete anti-selectivity, affording the bicyclic product 2a in 82% yield with >99% enantioselectivity (Scheme 2). In contrast, the reaction of 1,3-enyne (E)-1a yielded the syn-selective bicyclic product 2a with moderate yield and 92% enantioselectivity. Besides, prolonging the reaction time did not enhance the conversion, and over 35% of the starting material (E)-1a remained unreacted in both cases. The reaction rates and syn/anti selectivity of the reaction were significantly influenced by the E or Z configuration of the 1,3-enyne substrates.17 Notably, the borylative cyclization of (Z)-1a proceeded much faster than that of (E)-1a, affording the desired product in high yield with exclusive enantioselectivity. This enhanced reactivity is likely attributed to reduced steric interaction between the Bpin and alkyne groups in Int-A compared to Int-B during C–C bond formation (see Scheme 1c).

Scheme 2. Comparative study of reaction rates.

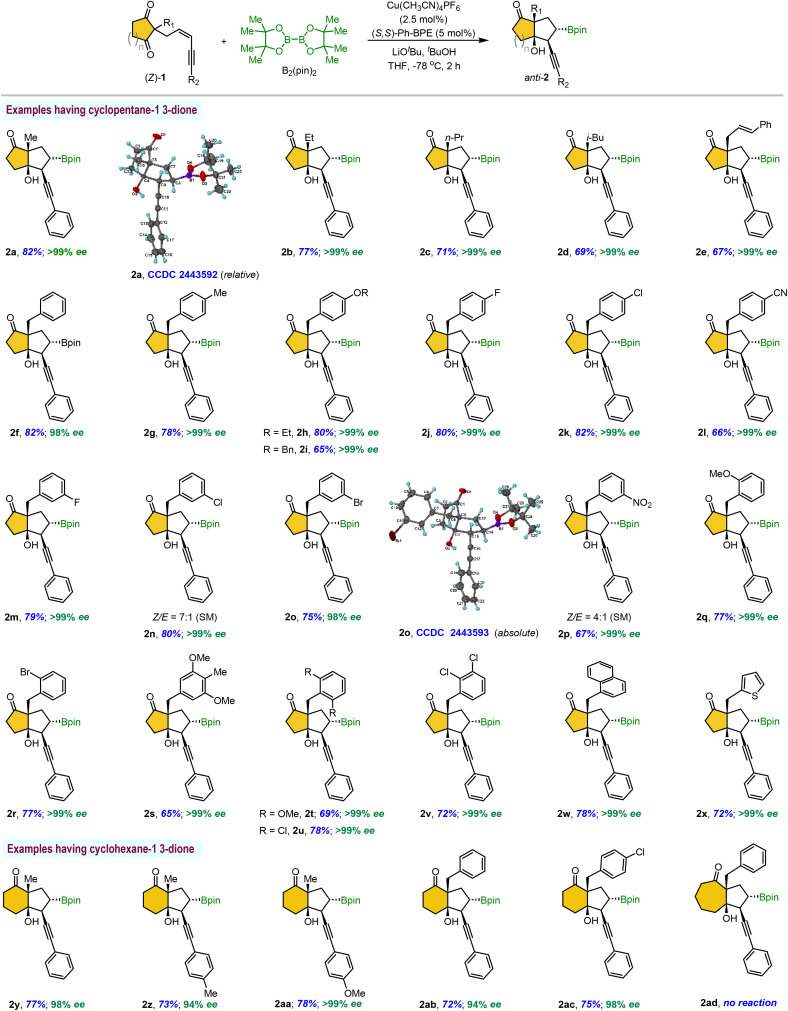

Later, the scope of the borylative cyclization in the presence of B2pin2 was explored using various prochiral (Z)-selective 1,3-enyne-tethered cyclic 1,3-diones 1 under optimized reaction conditions, unless otherwise specified for the Z/E ratio of the substrate. Our initial investigation focused on phenyl-substituted enynes with various substituents at the all-carbon prochiral center, and the results are summarized in Table 2. Substrates bearing sterically diverse alkyl groups and a cinnamyl group at the quaternary center were well-tolerated, undergoing borylative enantioselective desymmetrization to afford the corresponding products 2a–2e in 67–82% yield with excellent enantioselectivity. Next, a range of benzyl groups with electronically and sterically tuned substituents at the prochiral center were evaluated. These 1,3-enyne-tethered cyclopenta-1,3-diones proved to be highly suitable, delivering bicyclo[3.3.0]octane products 2f–2v in good yields with uniformly >99% ee across all cases. Particularly, the reaction was carried out on the substrates as an inseparable mixture of (Z/E)-isomers, with the major (Z)-1,3-enyne predominantly yielding the corresponding products anti-2n and anti-2p, along with trace amounts of syn-products derived from the (E)-isomer. Beyond benzyl groups, a similar range of yields and enantioselectivities was observed with other substituents, including 1-naphthyl and thiophen-2-ylmethylene groups at the quaternary prochiral center, furnishing products 2w and 2x, respectively. Next, the generality of the present approach was evaluated using Z-selective enyne-tethered cyclohexa-1,3-diones under standard conditions, which provided the corresponding products 2y–2ac in comparable yields and enantioselectivities. However, the cycloheptane-1,3-dione substrate failed to afford the desired product (2ad), and most of the starting material was recovered. The absolute stereochemistry of the bicyclic ketone anti-2o was unambiguously established by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis.16 The stereochemical assignments of the remaining products were assumed by analogy.

Next, we explored the scope of 1,3-enynes bearing various aromatic substituents (Table 3). The reaction was carried out on a mixture of (Z/E)-isomers under standard conditions, yielding product anti-2 predominantly from (Z)-1,3-enyne as the major diastereomer due to its higher reaction rate. Only trace amounts of the syn-product 2 (<5% yield) were identified from (E)-1 in a few examples, highlighting the strong stereochemical influence on the reaction outcome. The transformation proceeded with good diastereoselectivity, and excellent enantioselectivity. Aromatic 1,3-enynes with diverse substituents, regardless of their electronic properties, were well-tolerated under the standard conditions. Substituents such as alkyl, alkoxy, and halogen groups at the para-, meta-, or ortho-positions of the phenyl ring afforded the corresponding products (2ae–2ao) in moderate yields with excellent enantioselectivity (97–99% ee). Additionally, 9-phenanthryl and 1-cyclohexenyl groups on 1,3-enynes were readily converted into the desired products (2ap and 2aq) in good yields with >99% enantioselectivity. Unfortunately, 3-enyne substrates bearing aliphatic substituents failed to afford the desired products, and most of the starting material was recovered (entries 2ar and 2as).

Table 3. Substrate scope of the (Z/E)-isomera,b,c,d,e.

|

Reaction conditions same as in Table 2.

Isolated yields of the major product anti-2.

Diastereoselectivity was observed to be >20 : 1 for the major isomer, which was confirmed by 1H NMR analysis.

Unable to find the ratio of major and minor products in the crude 1H NMR analysis.

Enantioselectivity of the major isomer. SM = starting material.

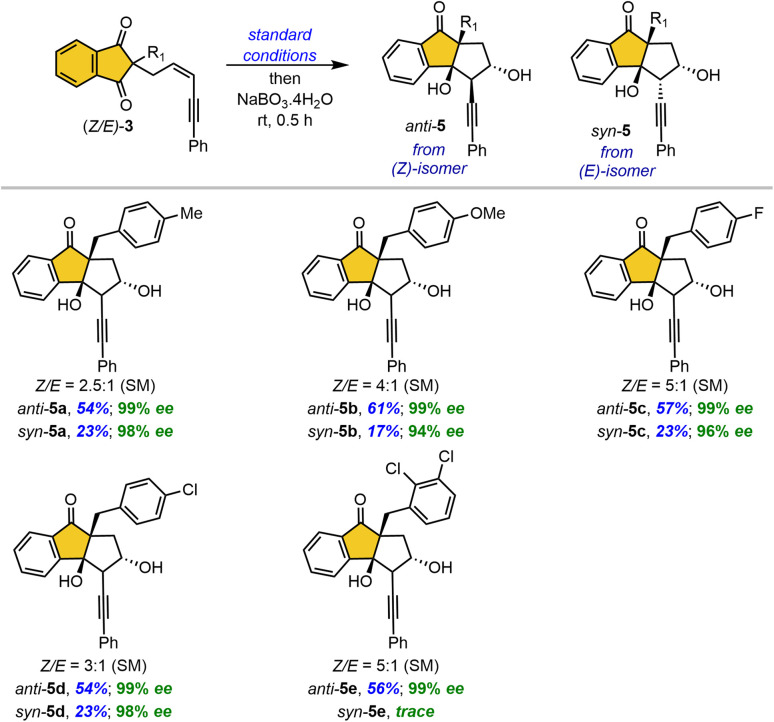

The enantioselective desymmetrization of α,α-disubstituted 1,3-indandione (Z/E)-3a (dr = 2.5 : 1) proceeded efficiently under the optimized reaction conditions, affording the desired product 4a as a mixture of inseparable diastereomers in a 1.5 : 1 ratio with a 71% yield (Scheme 3). Subsequent oxidation of the Bpin group using NaBO3·4H2O yielded the corresponding alcohols anti-5a (56%) and syn-5a (35%) as separable diastereomers, which were easily purified via simple column chromatography. It is interesting to observe that the (E)-isomer of the 1,3-indandione substrate reacts just as effectively as the (Z)-isomer.

Scheme 3. Borylative cyclization of 1,3-indandiones.

For ease of handling, we performed a one-pot borylative cyclization/oxidation of 1,3-indandiones under standard reaction conditions, followed by the sequential addition of NaBO3·4H2O (Table 4). We briefly screened this reaction with substrates featuring various benzyl groups at the prochiral quaternary center, yielding separable diastereomeric products anti-5 and syn-5. Electronically diverse substituents on the benzyl group provided high yields and excellent enantioselectivities (5a–5d). However, a sterically demanding ortho-substituted benzyl group resulted in only a trace amount of syn-product from the (E)-isomer and predominantly anti-5e from the (Z)-isomer.

Table 4. One-pot borylative cyclization/oxidation of 1,3-indandionesa,b,c,d.

|

Reaction conditions: Same as in Table 2 and then NaBO3·4H2O (150 mg, 1.5 mmol, 5.0 equiv.) was added in the same reaction.

Isolated yields of respective diastereomers.

Enantiomeric excess (ee) was determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

The dr was observed from 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. SM = starting material.

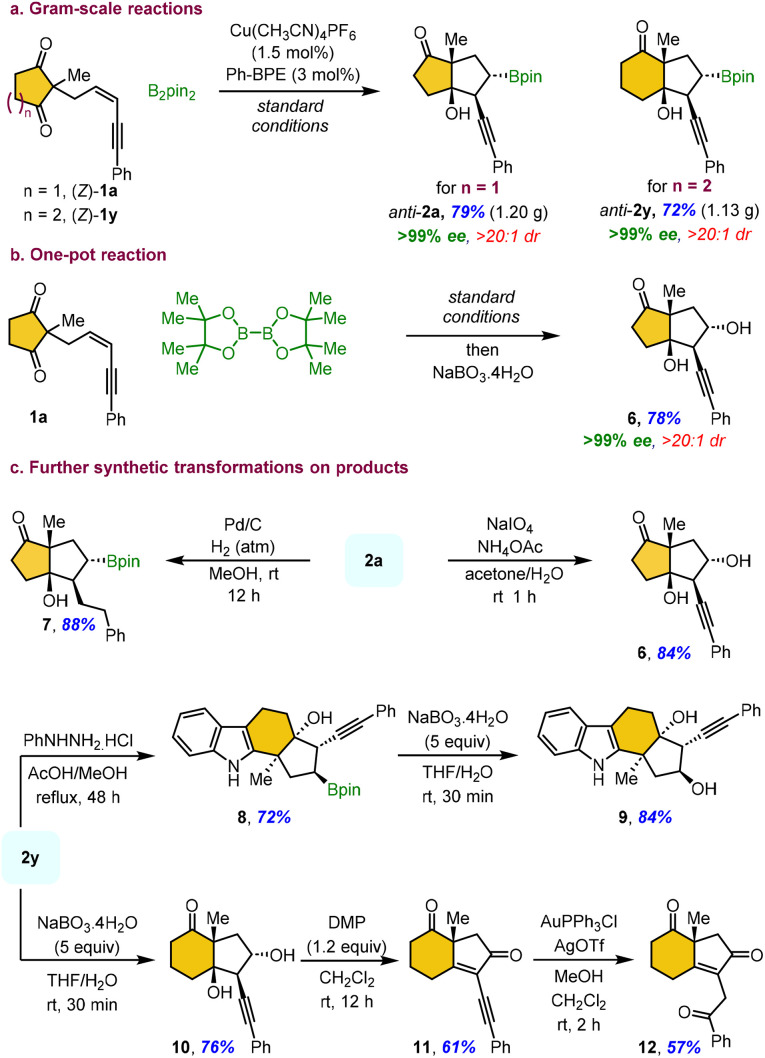

Gram-scale reactions using (Z)-1a and (Z)-1y were carried out with reduced catalyst loading under standard conditions, affording the desired products anti-2a and anti-2y, respectively, without any significant loss in yield or enantioselectivity (Scheme 4a). The one-pot borylative cyclization, followed by the sequential addition of the mild oxidizing agent sodium perborate, afforded the corresponding alcohol 6 in a similar yield with exclusive enantioselectivity (Scheme 4b). Interestingly, the reaction with the strong oxidizing agent sodium periodate also afforded alcohol 6 in high yield, instead of undergoing boronic ester hydrolysis (Scheme 4c). The Pd/C-catalyzed hydrogenolysis of compound 2a successfully reduces the triple bond, providing bicyclic ketone 7 in 88%yield. The Fischer cyclization of compound 2y with phenylhydrazine furnished a highly functionalized tetracyclic fused indole 8 in 72% yield. Subsequent oxidation of 8 with sodium perborate afforded the corresponding alcohol 9 in 84% yield. Interestingly, direct oxidation of 2y with sodium perborate yielded alcohol 10, which upon Dess–Martin periodinane (DMP) oxidation provided the α-alkynyl enone 11via sequential alcohol oxidation and tert-alcohol elimination in good yield. This highly reactive, fused, electron-deficient enyne 11 serves as a promising intermediate for diverse cycloaddition reactions. In addition, Au(i)-catalyzed hydration of enyne 11 in methanol afforded arylketone 12 in 57% yield.

Scheme 4. Large-scale reactions and further transformations.

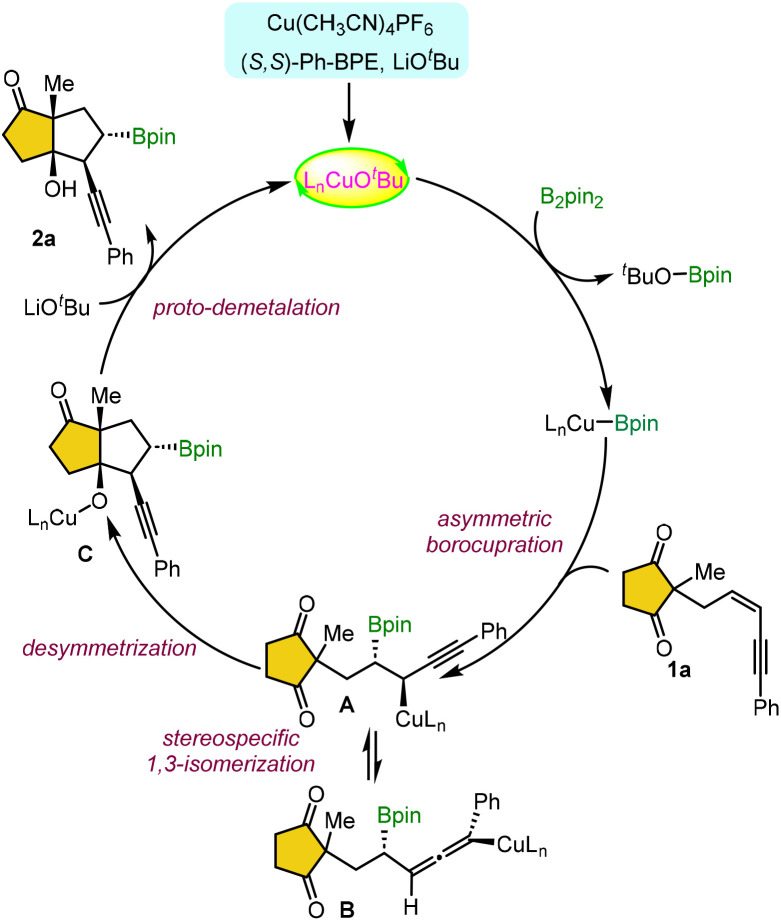

Based on the proposed copper catalytic cycle, the ligated copper alkoxide complex LnCuOtBu is generated in situ in the presence of a chiral ligand and base (Scheme 5). This complex undergoes σ-bond metathesis with a diboron reagent, yielding the LnCu–Bpin species. The enantioselective and regioselective 1,2-syn-addition of LnCu–Bpin to the 1,3-enyne-tethered cyclic-1,3-dione 1a leads to the formation of a propargylic copper intermediate A. This intermediate exists in equilibrium with an axially chiral allenyl–copper intermediate B via a stereospecific isomerization. Subsequent desymmetrization through annulation of propargylic intermediate A furnishes the desired product 2a, while the catalytic cycle is completed by regenerating LnCu–OtBu via a copper alkoxide intermediate C in the presence of a base.

Scheme 5. Plausible reaction mechanism.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a stereospecific, enantioselective copper(i)-catalyzed borylative cyclization of prochiral 1,3-enyne-tethered cyclic-1,3-diones with excellent diastereoselectivity. This asymmetric desymmetrization reaction efficiently delivers highly functionalized chiral octahydropentalenes bearing four contiguous stereocenters. Notably, the use of a BPE-ligand resulted in >99% ee for most examples. Additionally, (Z)-1,3-enyne substrates react more rapidly than their (E)-isomers, affording borylation products in high yields under standard reaction conditions. Ongoing studies in our laboratory are focused on further Cu(i)-catalyzed stereoselective transformations.

Author contributions

G. R. and V. B. P. performed the experiments and analyzed the experimental data; J. B. N. conducted the single X-ray crystallographic analysis; R. C. designed and supervised the project and wrote the manuscript with the assistance of co-authors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the SERB Core Research Grant (CRG/2022/001419) and the SERB-STAR Award (STR/2022/000007) from ANRF, New Delhi, for financial support. The authors thank CSIR-IICT for research facilities and CSIR, New Delhi for research fellowships. IICT Manuscript Communication Number: IICT/Pubs./2025/107.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. CCDC 2443592 and 2443593. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d5sc03007b

Data availability

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the ESI.†

Notes and references

- (a) Saito S. Yamamoto Y. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2901–2916. doi: 10.1021/cr990281x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wessig P. Müller G. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2051–2063. doi: 10.1021/cr0783986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Campbell K. Kuehl C. J. Ferguson M. J. Stang P. J. Tykwinski R. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7266–7267. doi: 10.1021/ja025773x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Trost B. M. Masters J. T. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:2212–2238. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00892A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Negishi E.-i. Anastasia L. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:1979–2018. doi: 10.1021/cr020377i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dherbassy Q. Manna S. Talbot F. J. T. Prasitwatcharakorn W. Perry G. J. P. Procter D. J. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:11380–11393. doi: 10.1039/D0SC04012F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Whyte A. Torelli A. Mirabi B. Zhang A. Lautens M. ACS Catal. 2020;10:11578–11622. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c02758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Holmes M. Schwartz L. A. Krische M. J. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:6026–6052. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; for the Cu-catalyzed borylative difunctionalization of π-systems, see: ; (c2) Dorn S. K. Brown M. K. ACS Catal. 2022;12:2058–2063. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c05696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xue W. Oestreich M. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020;6:1070–1081. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Perry G. J. P. Jia T. Procter D. J. ACS Catal. 2020;10:1485–1499. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b04767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hemming D. Fritzemeier R. Westcott S. A. Santos W. L. Steel P. G. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:7477–7494. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00816C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; for other selected asymmetric functionalizations on 1,3-enynes, see: ; (g2) Han J. W. Tokunaga N. Hayashi T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12915–12916. doi: 10.1021/ja017138h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Adamson N. J. Jeddi H. Malcolmson S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:8574–8583. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b02637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Zhang Y. Yang J. Ruan Y. L. Liao L. Ma C. Xue X. S. Yu J. S. Chem. Sci. 2023;14:12676. doi: 10.1039/D3SC04474B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Li L. Wang S. Jakhar A. Shao Z. Green Synth. Catal. 2023;4:124–134. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Miyaura N. Suzuki A. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:2457–2483. doi: 10.1021/cr00039a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sandford C. Aggarwal V. K. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:5481–5494. doi: 10.1039/C7CC01254C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y. Horita Y. Zhong C. Sawamura M. Ito H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:2778–2782. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F. Haeffner F. Hoveyda A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11304–11307. doi: 10.1021/ja5071202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Gan X.-C. Yin L. Org. Lett. 2019;21:931–936. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gan X. C. Zhang Q. Jia X.-S. Yin L. Org. Lett. 2018;20:1070–1073. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b04039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; for 1,2-borylacylation, see: ; (c2) Liu X.-L. Li L. Lin H.-Z. Deng J.-T. Zhang X.-Z. Peng J.-B. Chem. Commun. 2022;58:5968–5971. doi: 10.1039/D2CC01732F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna S. Dherbassy Q. Perry G. J. P. Procter D. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:4879–4882. doi: 10.1002/anie.201915191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon W. S. Jang W. J. Yoon W. Yun H. Yun J. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:2570. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30286-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y. Yin X. Wang X. Yu W. Fang D. Hu L. Wang M. Liao J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:1176–1180. doi: 10.1002/anie.201912703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. Liu Z.-L. Dai D.-T. Li Q. Ma W.-W. Zhao M. Xu Y.-H. Org. Lett. 2020;22:1360–1367. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b04647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For CuH catalyzed 1,2-hydrofunctionalizations, see: ; (a) Yang Y. Perry I. B. Lu G. Liu P. Buchwald S. L. Science. 2016;353:144–150. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhou Y. Zhou L. Jesikiewicz L. T. Liu P. Buchwald S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:9908–9914. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c03859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For CuH catalyzed 1,4-hydrofunctionalizations, see: ; (a) Bayeh-Romero L. Buchwald S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:13788–13794. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b07582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu S. Sang H. L. Zhang S.-Q. Hong X. Ge S. Commun. Chem. 2018;1:64. doi: 10.1038/s42004-018-0065-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; for enantioselective Cu-catalyzed hydroboration of 1,3-enynes, see: ; (c2) Huang Y. Pozo J. Torker S. Hoveyda A.-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:2643–2655. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b13296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sang H.-J. Yu S. Ge S. Org. Chem. Front. 2018;5:1284–1287. doi: 10.1039/C8QO00167G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (e) Gao D.-W. Xiao Y. Liu M. Karunananda M.-K. Chen J.-S. Engle K.-M. ACS Catal. 2018;8:3650–3654. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b00626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Maurya S. Navaneetha N. Behera P. Nanubolu J. B. Roy L. Chegondi R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025;64:e202420106. doi: 10.1002/anie.202420106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Navaneetha N. Maurya S. Behera P. Jadhav S. B. Magham L. R. Nanubolu J. B. Roy L. Chegondi R. Chem. Sci. 2024;15:20379–20387. doi: 10.1039/D4SC07002J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Patil V. B. Jadhav S. B. Nanubolu J. B. Chegondi R. Org. Lett. 2022;24:8233–8238. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c03359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jadhav S. B. Dash S. R. Maurya S. Nanubolu J. B. Vanka K. Chegondi R. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:854. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28288-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCDC-2443592 (compound 2a) and CCDC-2443593 (compound 2o) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper.

- (a) Ito H. Kosaka Y. Nonoyama K. Sasaki Y. Sawamura M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:7424–7427. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ito H. Toyoda T. Sawamura M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5990–5992. doi: 10.1021/ja101793a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the ESI.†