Abstract

Background

Stroke is a severe neurological disorder that poses a significant threat to patients’ health and imposes a heavy burden on healthcare resources. This study aims to systematically evaluate the synergistic effects of core stability training combined with various rehabilitation interventions to identify the optimal treatment strategy for lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients, providing stronger evidence for clinical practice.

Methods

This study included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published before May 12, 2025. The included studies met the following criteria: Participants were stroke patients with lower extremity dysfunction; The intervention in the experimental group involved core stability training or core stability training combined with other rehabilitation measures; The control group received either core stability training alone or conventional rehabilitation treatment; Outcome measures included balance ability, functional mobility, lower extremity motor ability, and walking ability; Study design was RCT. We searched six databases, including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), and SinoMed (China Biology Medicine), and conducted a network meta-analysis using R studio and Stata 15.0. We used the Risk of Bias 2.0 (ROB 2.0) tool to assess the risk of bias in the included studies.

Results

For balance ability in stroke patients, the rehabilitation effect of neuromuscular electrical stimulation combined with core stability training (NMES + CST) seemed to be the most effective, with a surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) of 90.82%. For functional mobility of lower extremity in stroke patients, proprioceptive training combined with core stability training (PT + CST) appeared to show the best rehabilitation effect (SUCRA = 93.24%). For motor ability of lower extremity, acupuncture therapy combined with core stability training (AT + CST) seemed to be the most effective (SUCRA = 90.83%). For walking ability, motor imagery training combined with core stability training (MIT + CST) seemed to be the optimal rehabilitation effect (SUCRA = 93.87%). Cluster analysis results indicated that the optimal treatment regimens for stroke-induced lower extremity dysfunction were PT + CST (SUCRA = 58.29%/SUCRA = 93.24%/ SUCRA = 63.59%/SUCRA = 56.03%) and AT + CST(SUCRA = 65.62%/SUCRA = 90.83%/SUCRA = 60.25%).

Conclusions

NMES + CST, PT + CST, AT + CST, and MIT + CST are four effective core stability training combination therapies. Comprehensive evaluation results indicate that AT + CST or PT + CST seems to be the optimal core stability training combination therapy for lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients.

Registration

PROSPERO CRD42024588917.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13102-025-01237-9.

Keywords: Stroke, Core stability training, Balance ability, Walking ability, Systematic review

Background

Stroke is a severe neurological disorder that poses a significant threat to patients’ health and imposes a heavy burden on healthcare resources [1]. Spasticity, one of the common complications of stroke, significantly affects the quality of life of many patients, with approximately 20-40% of stroke survivors experiencing this condition [2]. The spasticity caused by stroke results in a series of lower extremity dysfunctions in survivors, such as instability when standing, reduced walking ability, and loss of muscle strength in the lower limbs [3]. To improve the quality of life of stroke patients and reduce the severity of stroke’s impact, rehabilitation treatments for lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients have become an important topic in the field of clinical medicine [4, 5].

Studies have shown that core stability training can effectively treat lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients [6, 7]. Core stability refers to the ability to control the trunk posture and balance within a complete kinetic chain, ensuring the highest efficiency in producing, transmitting, and controlling speed and power to the extremities [8, 9]. Spasticity caused by stroke not only directly contributes to lower limb dysfunction, but may also impair trunk muscle control or lead to compensatory movements that increase the demand on core musculature. Both pathways frequently result in compromised core stability—the ability to maintain trunk control and balance [8, 9]. Such core instability further restricts functional recovery, including standing, walking, and effective use of the lower extremity. Base on this, a stable and strong core allows patients to utilize their lower extremity more effectively [6, 8, 9], which is essential for the rehabilitation of lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients [6]. Research by Cabanas [6] and Haruyama [7] has shown that, compared to conventional rehabilitation therapies, core stability training can more effectively improve walking and balance abilities in stroke patients. A meta-analysis also indicated that core stability training is superior to other exercise therapies in improving balance ability in stroke patients [10].

With advancements in medical techniques, various exercise interventions and physical therapy methods have also been proven to be effective in the rehabilitation of lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients, such as proprioceptive training [11], functional electrical stimulation [12], and acupuncture therapy [13]. To achieve better treatment outcomes, many rehabilitation therapists have adopted combined approaches using core stability training, such as core stability training combined with robotic rehabilitation therapy [14], core stability training combined with proprioceptive training [15], and core stability training combined with neuromuscular electrical stimulation [16]. It is worth noting that these combination therapies often yield better results than using core stability training alone [14, 16]. Although core stability training has been extensively studied in the field of stroke rehabilitation and has shown promising effects in improving lower extremity function, existing research primarily focuses on the mechanisms and efficacy of single core stability training interventions [7, 17]. Currently, comparative studies on the effectiveness of different core stability training combination strategies remain limited, and systematic evidence is still lacking to determine the optimal combination for achieving the best rehabilitation outcomes.

Network meta-analysis (NMA) is a specialized form of meta-analysis that integrates direct, indirect, and mixed comparisons of different interventions to determine their specific efficacy [18]. This approach allows for a comprehensive comparison of various treatment strategies, ultimately identifying the most effective intervention [18]. This study aims to identify the optimal core stability training combination for treating lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients by comparing the efficacy of core stability training combined with different rehabilitation interventions in post-stroke lower extremity functional recovery.

Methods

This network meta-analysis strictly follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Network Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-NMA) guidelines [19] and adheres to the methodological requirements outlined in the Cochrane Handbook to ensure transparency and scientific rigor. Additionally, to enhance the traceability and standardization of the research process, this systematic review protocol has been registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the registration number CRD42024588917.

Search strategy

This NMA conducted a comprehensive electronic literature search across six databases: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and China Biology Medicine (SinoMed). For CNKI and SinoMed, only studies indexed in the “Chinese Core Journals” by Peking University Library or the Chinese Science Citation Database (CSCD) were included. The search was conducted up to May 12, 2025. Different search strategies were applied based on the requirements of each database, and the comprehensive search strategy is available in Additional Table S1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria: (1) Participants: Individuals aged over 18 years with post-stroke lower limb dysfunction, diagnosed with stroke by computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), clinical assessment by a physician, or other medically recognized diagnostic approaches. The detailed diagnostic information is shown in Additional Table S2. There were no restrictions on gender, nationality, ethnicity, disease course, or stroke phase. (2) Interventions: Core stability training, or core stability training combined program. The detailed core stability training frequency and duration are shown in Additional Table S3. (3) Control Group: Core stability training or conventional rehabilitation therapy. (4) Outcome Measures: The outcome measures include the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), the Functional Ambulation Category Scale (FAC), the Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Lower Extremity (FMA-LE), and the Timed Up and Go Test (TUGT). The BBS reflects the balance ability of stroke patients [20]. The FAC reflects the walking ability of stroke patients [21]. The TUGT reflects the functional mobility of stroke patients [22]. The FMA-LE reflects the lower extremity motor ability [23]. (5) Study Design: Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of complete original research articles are included. RCTs designated as “pilot” or “feasibility” studies were eligible for inclusion provided they met all other PICOS criteria and methodological requirements. The inclusion of only RCTs in this study was intended to ensure that the evidence used to evaluate the effects of interventions is of high quality and carries a low risk of bias, which is crucial for ensuring the validity of the NMA results. Due to the lack of long-term follow-up data in most of the original data, we extracted data from the end of the intervention rather than long-term follow-up.

The exclusion criteria: (1) Reviews, responses, systematic reviews, letters, etc. (2) Studies with duplicate publications. (3) Studies with interventions not meeting the inclusion criteria, studies with outcomes not meeting the requirements, or studies with apparent data errors and unavailable data. (4) RCTs published in languages other than Chinese or English. (5) Grey literature.

Study selection

Two researchers independently (K.Z. and L.G.) carried out the literature screening process and extracted relevant data in accordance with predefined criteria. The retrieved bibliographic records were imported into Endnote X9 software for deduplication, with some records requiring manual deduplication. The retrieved studies were systematically reviewed based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify eligible RCTs for analysis. If any discrepancies arise during the screening process, they will first be addressed through thorough discussion to reach a consensus. If consensus cannot be achieved, a third, more experienced researcher (C.D.) will be consulted to review the case and make the final decision. Data extraction was conducted following a standardized approach, and all relevant information was recorded and organized using an Excel spreadsheet. The extracted information primarily included publication year, country, first author, patient age, sample size, intervention protocols for the treatment and control groups, outcome measures, and disease duration. For studies with more than two intervention arms (i.e., multi-arm trials), data for all eligible intervention groups (including mean, standard deviation (SD), and sample size (N) for continuous outcomes) were extracted independently. This arm-level data structure allows the network meta-analysis to synthesize all available comparisons from these trials (e.g., A vs. B, A vs. C, and B vs. C from an A-B-C trial) simultaneously, while preserving the benefits of within-trial randomization and appropriately accounting for correlations between effect estimates sharing a common comparator.

Quality assessment of included studies

Two researchers assessed the methodological quality of the included studies based on the risk of bias assessment tool (ROB 2.0) from the Cochrane Handbook [24–26]. Before the formal assessment, both reviewers (K.Z. and L.G.) familiarized themselves with the ROB 2.0 guidance and jointly assessed a small number of studies to ensure consistent interpretation and application of the criteria. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion, including rechecking the study data and referring to the ROB 2.0 manual, with the goal of reaching consensus. If consensus could not be achieved, a third reviewer (C.D.) was consulted to make the final decision. The assessment encompassed multiple key domains, including the randomization process, deviations from the intended intervention, completeness of outcome data, procedures for outcome evaluation, and potential selective reporting bias. Each domain was evaluated using a set of 1–7 specific questions to ensure a comprehensive risk of bias analysis. The results were classified as “high risk,” “low risk,” or “some concern.” The overall risk of bias for each study was determined based on the judgments across individual domains, following the recommendations of the Cochrane ROB 2.0 tool: Low risk: All domains were judged to be at low risk of bias. Some concerns: At least one domain was judged to raise some concerns, but none were rated as high risk. High risk: At least one domain was judged to be at high risk of bias; or there were majority of domains with some concerns, and the cumulative effect of these concerns was sufficient to rate the study as being at high risk overall.

Data analysis

This Bayesian network meta-analysis utilized R 4.2.1 with the “gemtc” and “coda” packages, as well as Stata 15 with the “gemtc” package. Mean difference (MD) was used for continuous outcome variables, with 95% credibility intervals (CrI) for interval estimation. The Bayesian network meta-analysis model, as implemented using the gemtc package, is specifically designed to incorporate data from multi-arm trials directly by utilizing arm-level outcome data, thereby ensuring that all relevant treatment comparisons are included and correlations are appropriately handled. To account for potential heterogeneity between studies, a random-effects consistency model was employed for all network meta-analyses. The between-study standard deviation (τ) was estimated within the Bayesian framework. We utilized the default prior distribution for τ as implemented in the “gemtc” package, which is a uniform distribution, τ∼U (0,om.scale), where “om.scale” represents an upper limit on τ estimated from the scale of the outcome data [27]. If the netplot contained a closed loop, local inconsistency testing was conducted. The consistency model was established with 20,000 burn-in iterations and 50,000 iterations. The Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) of the iterative results was compared with that of the inconsistency model, and if the difference was less than 5, the data were considered consistent. We used SUCRA values to determine the most effective intervention for each specific outcome, with higher SUCRA values indicating better performance. To identify comprehensive treatment strategies that perform well across multiple functional domains, we further conducted two-dimensional cluster analyses based on paired SUCRA values. Interventions that consistently ranked highly in the cluster analyses were considered potential optimal treatment strategies. A comparison-adjusted funnel plot was used to assess publication bias in the included RCTs. The plausibility of the transitivity assumption, which underlies indirect comparisons in NMA, was qualitatively assessed by comparing the distribution of key potential effect modifiers (e.g., patient baseline characteristics such as age and stroke severity, specific components of co-interventions, study settings, and outcome assessment timings) across trials that connected directly or indirectly in the network. A sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding studies assessed as having a high risk of bias, in order to evaluate their influence on the overall pooled outcomes.

Results

Search results

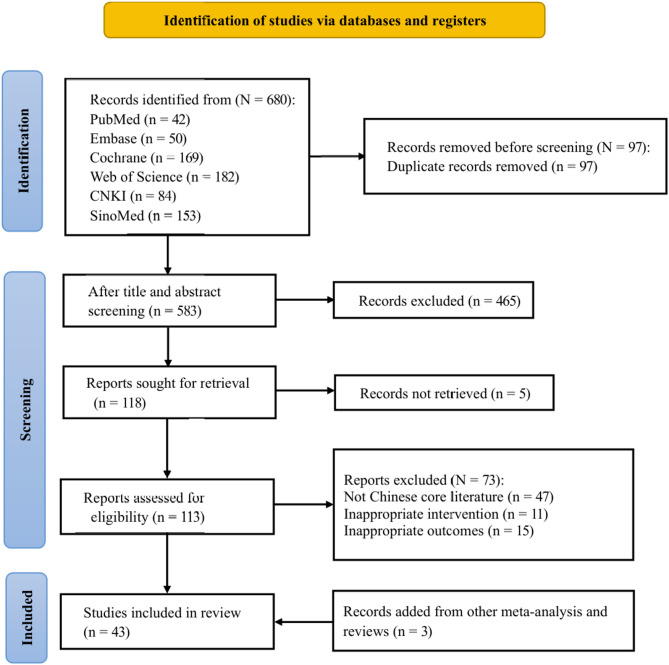

A total of 680 articles were initially identified from six medical databases, including 182 from Web of Science, 42 from PubMed, 169 from the Cochrane Library, 50 from Embase, 84 from CNKI, and 153 from SinoMed. Before screening, 97 duplicate records were removed using EndNote X9. Then, 465 articles were excluded after screening titles and abstracts, and 5 articles were excluded due to unavailability of the full text. Of the remaining 113 full-text articles, 47 were excluded for not being published in core Chinese journals, 11 were excluded due to inappropriate interventions, and 15 were excluded for not meeting the outcome criteria. Ultimately, 40 studies met the inclusion criteria. Additionally, we identified 3 more eligible studies from reference lists of other systematic reviews and meta-analyses. In total, 43 studies were included in this meta-analysis, and 640 studies were excluded. The specific search, exclusion, and inclusion process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of literature screening

Characteristics of included studies

This study included 43 RCTs [6, 7, 14–17, 20–23, 28–60], involving 2,227 stroke patients and 13 intervention protocols. The control group interventions consisted of either core stability training or conventional rehabilitation therapy (C), while the treatment group received core stability training combined with 11 additional rehabilitation therapies. Both the treatment groups and control groups were assumed to receive conventional rehabilitation therapy as the default intervention.

The 11 combined interventions in the experimental group were: Bobath therapy combined with core stability training (BT + CST), neuromuscular electrical stimulation combined with core stability training (NMES + CST), robotic rehabilitation therapy combined with core stability training (RRT + CST), weight training combined with core stability training (WT + CST), task-oriented training combined with core stability training (TOT + CST), visual feedback training combined with core stability training (VFT + CST), acupuncture therapy combined with core stability training (AT + CST), closed kinematic chain exercise combined with core stability training (CKCE + CST), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with core stability training (rTMS + CST), motor imagery training combined with core stability training (MIT + CST), proprioceptive training combined with core stability training (PT + CST). The basic characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The basic characteristics of the included studies

| NO. | Study | Country | Age (TG) | Age (CG) | N (TG) | N (CG) | Treatment (TG) | Treatment (CG) | Outcome | Duration (TG) | Duration (CG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yoo2010 [28] | Korea | 59.61 ± 18.16 | 61.77 ± 12.58 | 28 | 31 | CST | C | BBS | 42.86 ± 35.08d | 48.03 ± 29.45d |

| 2 | Verma2022 [29] | India | 40–65 | 40–65 | 15 | 15 | BT + CST | C | BBS | NR | NR |

| 3 | Salgueiro2022 [17] | Spain | 57.27 ± 14.35 | 64.53 ± 9.40 | 15 | 15 | CST | C | BBS | 4.61 ± 3.38y | 4.06 ± 4.43y |

| 4 | Park2018 [30] | Korea | 68.6 ± 13.57 | 57.5 ± 11.84 | 10 | 10 | NMES + CST | CST | BBS | 17.3 ± 9.12d | 13.6 ± 5.52d |

| 5 | Nadeem2024 [31] | Pakistan | 40–60 | 40–60 | 37 | 37 | CST | C | TUGT | NR | NR |

| 6 | Min2020 [21] | Korea | 61.47 ± 11.15 | 56.36 ± 9.16 | 19 | 19 | RRT + CST | C | BBS, TUGT, FAC, FMA-LE | 921.52 ± 1762d | 788.73 ± 999.24d |

| 7 | Mahmood2022 [32] | Pakistan | 57.10 ± 6.28 | 54.95 ± 6.35 | 20 | 21 | CST | C | FAC | NR | NR |

| 8 | Lee2020 [33] | Korea | 69.57 ± 11.75 | 68.57 ± 9.54 | 10 | 10 | CST | C | TUGT, BBS | NR | NR |

| 9 | Ko2016 [16] | Korea | 58.5 | 59.5 | 10 | 10 | NMES + CST | CST | BBS | 11d | 12d |

| 10 | Kim SM2022 [22] | Korea | 61.5 ± 8.04 | 61.7 ± 6.66 | 10 | 10 | WT + CST | CST | BBS, TUGT | 2.62 ± 1.3 m | 2.7 ± 1.36 m |

| 61.6 ± 3.92 | 10 | C | 2.75 ± 1.4 m | ||||||||

| 11 | Kim DH2022 [14] | Korea | 56.8 ± 12.78 | 56.75 ± 13.31 | 20 | 20 | RRT + CST | CST | BBS | NR | NR |

| 12 | Jeong2023 [34] | Korea | 51.08 ± 11.84 | 48.33 ± 10.81 | 13 | 12 | TOT + CST | C | BBS | 15.85 ± 5.74 m | 14.42 ± 5.43 m |

| 13 | Haruyama2017 [7] | Japan | 67.56 ± 10.11 | 65.63 ± 11.97 | 16 | 16 | CST | C | FAC, TUGT | 66d | 72d |

| 14 | Dubey2018 [35] | India | 54.35 ± 11.64 | 58.24 ± 11.77 | 17 | 17 | CST | C | FMA-LE | 240 ± 135d | 199 ± 176d |

| 15 | Chung2013 [36] | Korea | 44.37 ± 9.9 | 48.38 ± 9.72 | 8 | 8 | CST | C | TUGT | 12.88 ± 7.16 m | 9.63 ± 4.86 m |

| 16 | Chun2016 [37] | Korea | 56.21 ± 9.30 | 53.93 ± 9.21 | 14 | 14 | CST | C | BBS, TUGT | 95.79 ± 122.12 m | 97.93 ± 79.59 m |

| 17 | Chen2020 [38] | China | 59.12 ± 12.67 | 59.05 ± 12.74 | 90 | 90 | CST | C | FMA-LE, BBS | 23.79 ± 2.45d | 24.06 ± 2.53d |

| 18 | Saeys2012 [39] | Belgium | <85 | <85 | 18 | 15 | CST | C | BBS, FAC | >4 m | >4 m |

| 19 | Cabanas-Valdés2016 [6] | Spain | 74.92 ± 10.7 | 75.69 ± 9.4 | 40 | 40 | CST | C | BBS | 25.12 ± 17.3d | 21.37 ± 16d |

| 20 | An2016 [40] | Korea | 59.73 ± 8.94 | 57.07 ± 17.17 | 15 | 14 | CST | C | BBS, TUGT | 9.07 ± 3.47 m | 8.93 ± 2.30 m |

| 21 | Büyükavcı2016 [41] | Turkey | 62.6 ± 10.5 | 63.6 ± 10.4 | 32 | 32 | CST | C | BBS | 33.4 ± 11.4d | 38.5 ± 19.9d |

| 22 | Kılınç2016 [42] | Turkey | 55.91 ± 7.92 | 54 ± 13.64 | 10 | 9 | BT + CST | C | BBS, TUGT | 58.66 ± 55.68 m | 67.20 ± 43.17 m |

| 23 | Lee2018 [43] | Korea | 57.9 ± 8.1 | 57.5 ± 9.2 | 14 | 14 | CST | C | BBS | 15.2 ± 5.4 m | 17.1 ± 5.2 m |

| 24 | Chitra2015 [20] | India | 52.07 ± 5.98 | 55.27 ± 8.25 | 15 | 15 | CST | C | BBS | 1.20 ± 1.72 m | 2.67 ± 2.53 m |

| 25 | Shin2016 [44] | Korea | 57.75 ± 14.03 | 59.25 ± 9.75 | 12 | 12 | VFT + CST | C | TUGT | 17.58 ± 10.04 m | 15.17 ± 7.13 m |

| 26 | Cong2018 [45] | China | 62.8 ± 5.9 | 63.2 ± 5.7 | 96 | 96 | AT + CST | CST | FMA-LE, BBS, FAC | NR | NR |

| 27 | Fu2016 [46] | China | 59.7 ± 7.6 | 60.3 ± 8.4 | 30 | 30 | CST | C | BBS, FAC | <3 m | <3 m |

| 28 | Guo2014 [47] | China | 55.41 ± 9.1 | 53.19 ± 11.29 | 28 | 28 | CKCE + CST | C | FMA-LE, FAC | 4.9 ± 7.6w | 5.1 ± 9.9w |

| 29 | Hu2020 [48] | China | 60.35 ± 7.63 | 61.92 ± 5.14 | 19 | 19 | rTMS + CST | CST | BBS | 3.32 ± 1.95 m | 3.57 ± 1.46 m |

| 30 | Liang2012 [49] | China | 56.33 ± 9.46 | 55.62 ± 9.98 | 34 | 34 | CST | C | BBS, FMA-LE, FAC | 18.15 ± 7.23d | 20.22 ± 8.09d |

| 31 | Liao2015 [50] | China | 56.3 ± 6.2 | 57.4 ± 6.7 | 40 | 40 | AT + CST | C | BBS, FMA-LE, FAC | 10.8 ± 2.6d | 10.5 ± 2.9d |

| 32 | Peng2022 [51] | China | 56.43 ± 13.60 | 59.73 ± 13.09 | 30 | 30 | PT + CST | CST | TUGT | 62 ± 42.77d | 72.63 ± 52.40d |

| 33 | Peng2017 [52] | China | 52.39 ± 9.2 | 53.25 ± 8.2 | 24 | 24 | MIT + CST | C | FMA-LE, BBS, FAC | 23.14 ± 5.8d | 22.16 ± 6.2d |

| 34 | Shen2013 [53] | China | 59.23 ± 12.85 | 58.18 ± 13.16 | 40 | 40 | CST | C | BBS, FAC | 4.02 ± 1.14 m | 3.86 ± 1.07 m |

| 35 | Wang2016 [54] | China | 59.11 ± 7.99 | 55.63 ± 8.25 | 9 | 8 | VFT + CST | CST | BBS | 26.75 ± 6.02d | 26 ± 8.55d |

| 36 | Wang2021 [23] | China | 63.27 ± 2.13 | 63.23 ± 2.15 | 56 | 56 | AT + CST | C | FMA-LE, BBS | 13.26 ± 2.49d | 13.23 ± 2.46d |

| 37 | Xie2014 [55] | China | 54.85 ± 7.98 | 55.35 ± 8.89 | 40 | 40 | BT + CST | C | FMA-LE, TUGT | 126.73 ± 19.53d | 126.05 ± 19.89d |

| 38 | Zhang2014 [15] | China | 65.13 ± 5.38 | 62.36 ± 6.43 | 20 | 20 | PT + CST | C | FMA-LE, BBS, TUGT, FAC | ≤ 6 m | ≤ 6 m |

| 39 | Zhang2016 [56] | China | 49.36 ± 10.62 | 48.4 ± 10.78 | 30 | 30 | CST | C | BBS, FMA-LE | 39.53 ± 11.64d | 40.06 ± 11.86d |

| 40 | Zhu2017 [57] | China | 59.46 ± 8.02 | 59.25 ± 9.41 | 28 | 28 | CST | C | BBS, TUGT | 21.11 ± 18.91d | 18.39 ± 16.11d |

| 41 | Hong2024 [58] | China | 54.63 ± 4.24 | 55 ± 3.79 | 30 | 30 | AT + CST | C | BBS, FAC | 28.5 ± 3.17d | 28.77 ± 3.98d |

| 42 | Aycicek2024 [59] | Turkey | 49.72 ± 14.32 | 57.8 ± 12.47 | 25 | 25 | CST | C | BBS | 15.16 ± 6.98 m | 16.88 ± 5.84 m |

| 43 | Almasoudi2024 [60] | Saudi Arabia | 28–86 | 28–86 | 23 | 23 | CST | C | BBS | 3–6 m | 3–6 m |

BBS: Berg Balance Scale; TUGT: Time Up and Go Test; FMA-LE: Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Lower Extremity; FAC: Functional Ambulation Category Scale; CG: Control Group; TG: Treatment Group; C: conventional rehabilitation therapy; CST: core stability training; BT: Bobath therapy; NMES: neuromuscular electrical stimulation; RRT: robotic rehabilitation therapy; WT: weight training; TOT: task-oriented training; VFT: visual feedback training; AT: acupuncture therapy; CKCE: closed kinematic chain exercise; rTMS: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; MIT: motor imagery training; PT: proprioceptive training; w: week; m: month; d: day; y: year; NR: no report

Quality assessment of included studies

Among the 43 included studies, 6 were judged to be at high risk of bias, while 37 were rated as having some concerns. In the process of randomization, 8 studies were rated as having some concerns, while 35 studies were rated as having a low risk. These “some concerns” ratings were primarily due to unclear reporting of the allocation concealment mechanism (e.g., not specifying how the random sequence was concealed until participants were allocated) or insufficient detail provided about the randomization generation process itself in these studies. Regarding deviations from intended interventions, all 43 studies were classified as having some concerns. This was predominantly because most interventions involved active rehabilitation where blinding of participants and therapists was not feasible. The potential impact of this lack of blinding on subjective outcomes, co-interventions, or differential adherence could not be entirely ruled out. Additionally, some studies did not clearly report adherence rates or how deviations from the intended intervention protocol were managed in the analysis. For completeness of outcome data, 35 studies were assessed as having a low risk, whereas 8 studies had some concerns. In this regard, some concerns arise from the attrition of some participants, which led to incomplete data collection. It is unclear whether the missing data were related to unfavorable measurement outcomes. In terms of outcome measurement, 20 studies were rated as having some concerns, and 23 studies as having a low risk. Ratings of some concerns in this domain often arose from a lack of explicit reporting on whether outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation, particularly for more subjective functional scales such as the BBS or FMA-LE. Unblinded assessment of such outcomes could potentially introduce detection bias. Regarding selective outcome reporting, all studies exhibited a low risk of bias. Some concerns of bias arising during the intervention process was the primary source of bias in the included studies. Figure 2 provides a detailed illustration of the risk of bias in the included studies.

Fig. 2.

Quality assessment of included studies

Network meta-analysis

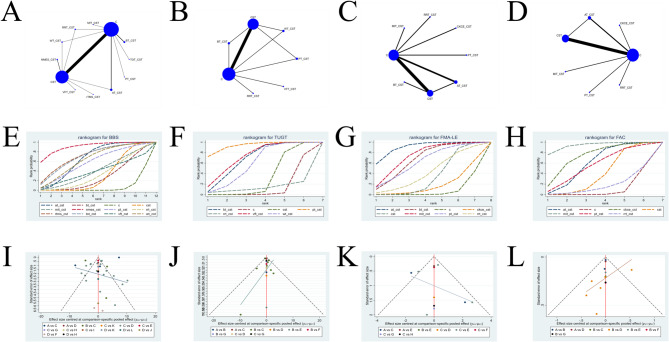

The netplots for 13 intervention protocols (including 11 core stability training combination therapies) are shown in Fig. 3A-D. Figures 3A–D correspond to four different outcome measures.

Fig. 3.

Network meta-analysis graph group. A: Netplot of Berg Balance Scale; B: Netplot of Time Up and Go Test; C: Netplot of Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Lower Extremity; D: Netplot of Functional Ambulation Category Scale; E: Cumulative probability curve of Berg Balance Scale; F: Cumulative probability curve of Time Up and Go Test; G: Cumulative probability curve of Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Lower Extremity; H: Cumulative probability curve of Functional Ambulation Category Scale; I: Funnel plot of Berg Balance Scale; J: Funnel plot of Time Up and Go Test; K: Funnel plot of Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Lower Extremity; L: Funnel plot of Functional Ambulation Category Scale. BBS: Berg Balance Scale; TUGT: Time Up and Go Test; FMA-LE: Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Lower Extremity; FAC: Functional Ambulation Category Scale; C: conventional rehabilitation therapy; CST: core stability training; BT: Bobath therapy; NMES: neuromuscular electrical stimulation; RRT: robotic rehabilitation therapy; WT: weight training; TOT: task-oriented training; VFT: visual feedback training; AT: acupuncture therapy; CKCE: closed kinematic chain exercise; rTMS: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; MIT: motor imagery training; PT: proprioceptive training

BBS

34 studies [6, 14–17, 20–23, 28–30, 33, 34, 37–43, 45, 46, 48–50, 52–54, 56–60] reported the BBS score, involving 12 rehabilitation protocols: C, CST, BT + CST, NMES + CST, RRT + CST, WT + CST, TOT + CST, AT + CST, rTMS + CST, MIT + CST, VFT + CST, and PT + CST. The netplot for the BBS outcome is shown in Fig. 3A.

The random-effects model estimated the between-study standard deviation (τ) to be 4.6083, 95% CrI (3.242, 6.552) for the BBS outcome, with an overall I2 of 0.6%. This suggests low absolute heterogeneity.

The league table for BBS is presented in Table 2. Above the diagonal are estimates from pairwise meta-analyses (PMA), while those below the diagonal represent estimates from network meta-analysis (NMA) [61]. The PMA presents the direct comparisons of effect sizes between intervention pairs. In the PMA for BBS, AT + CST (MD: 7.8, 95% CrI: 2.3–13.0), CST (MD: 4.7, 95% CrI: 2.3–7.2), and TOT + CST (MD: 11.0, 95% CrI: 1.1–21.0) were more effective than C. Additionally, AT + CST (MD: 9.9, 95% CrI: 0.38–19.0) and NMES + CST (MD: 13.0, 95% CrI: 1.9–24.0) were significantly more effective than CST. All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). NMA integrates both direct and indirect comparisons among interventions, providing effect estimates that are not available from pairwise analyses alone. In the NMA for BBS, the following interventions were more effective than C: AT + CST (MD: 9.42, 95% CrI: 4.71–14.21), CST (MD: 4.24, 95% CrI: 2–6.61), NMES + CST (MD: 17.19, 95% CrI: 5.86–28.48), rTMS + CST (MD: 11.47, 95% CrI: 0.64–22.43), TOT + CST (MD: 11.1, 95% CrI: 1.25–20.96), and WT + CST (MD: 9.51, 95% CrI: 1.15–17.94). Compared with CST, AT + CST (MD: 5.17, 95% CrI: 0.11–10.16) and NMES + CST (MD: 12.92, 95% CrI: 1.86–23.95) were more effective. Furthermore, NMES + CST (MD: 13.78, 95% CrI: 1.03–26.56) showed superior efficacy compared with BT + CST. All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

League table of BBS

| Pairwise meta-analysis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network meta-analysis | AT + CST | -7.8 (-13.0, -2.3) | -9.9 (-19.0, -0.38) | |||||||||

| 5.99 (-1.48, 13.81) | BT + CST | -3.4 (-9.3, 2.7) | ||||||||||

| 9.42 (4.71, 14.21) | 3.42 (-2.65, 9.3) | C | 4.7 (2.3, 7.2) | 5.4 (-4.1, 15.0) | 8.6 (-1.5, 19.0) | 2.9 (-7.1, 13.0) | 11.0 (1.1, 21.0) | 9.4 (-0.39, 19.0) | ||||

| 5.17 (0.11, 10.16) | -0.83 (-7.37, 5.42) | -4.24 (-6.61, -2) | CST | 13.0 (1.9, 24.0) | 1.5 (-8.6, 11.0) | 7.2 (-3.6, 18.0) | 0.65 (-14.0. 15.0) | 5.4 (-4.5, 15.0) | ||||

| 4.03 (-6.42, 14.56) | -1.96 (-13.17, 9) | -5.37 (-14.73, 3.95) | -1.12 (-10.71, 8.49) | MIT + CST | ||||||||

| -7.77 (-19.87, 4.4) | -13.78 (-26.56, -1.03) | -17.19 (-28.48, -5.86) | -12.92 (-23.95, -1.86) | -11.78 (-26.43, 2.77) | NMES + CST | |||||||

| 0.83 (-10.26, 11.84) | -5.18 (-16.95, 6.37) | -8.6 (-18.57, 1.35) | -4.36 (-14.55, 5.89) | -3.22 (-16.9, 10.42) | 8.57 (-6.43, 23.68) | PT + CST | ||||||

| 5.06 (-3.37, 13.56) | -0.94 (-10.31, 8.22) | -4.35 (-11.47, 2.73) | -0.1 (-7.15, 7.02) | 1.01 (-10.66, 12.7) | 12.84 (-0.24, 25.89) | 4.26 (-7.99, 16.46) | RRT + CST | |||||

| -2.07 (-13.88, 9.65) | -8.07 (-20.62, 4.19) | -11.47 (-22.43, -0.64) | -7.22 (-17.9, 3.41) | -6.11 (-20.47, 8.14) | 5.68 (-9.68, 20.97) | -2.88 (-17.71, 11.85) | -7.13 (-20, 5.6) | rTMS + CST | ||||

| -1.67 (-12.62, 9.31) | -7.66 (-19.3, 3.77) | -11.1 (-20.96, -1.25) | -6.85 (-16.95, 3.3) | -5.73 (-19.28, 7.82) | 6.08 (-8.86, 21.12) | -2.49 (-16.44, 11.55) | -6.75 (-18.84, 5.38) | 0.39 (-14.26, 15.14) | TOT + CST | |||

| 4.66 (-10.7, 19.82) | -1.36 (-17.29, 14.35) | -4.75 (-19.52, 9.78) | -0.51 (-15.04, 13.88) | 0.62 (-16.85, 17.85) | 12.38 (-5.9, 30.6) | 3.86 (-13.92, 21.5) | -0.38 (-16.58, 15.59) | 6.72 (-11.3, 24.66) | 6.35 (-11.33, 23.87) | VFT + CST | ||

| -0.09 (-9.72, 9.48) | -6.09 (-16.52, 4.06) | -9.51 (-17.94, -1.15) | -5.27 (-13.66, 3.17) | -4.13 (-16.7, 8.48) | 7.65 (-6.1, 21.54) | -0.92 (-13.86, 12.13) | -5.15 (-16.04, 5.71) | 1.95 (-11.56, 15.53) | 1.58 (-11.41, 14.48) | -4.76 (-21.4, 12.04) | WT + CST | |

BBS: Berg Balance Scale; C: conventional rehabilitation therapy; CST: core stability training; BT: Bobath therapy; NMES: neuromuscular electrical stimulation; RRT: robotic rehabilitation therapy; WT: weight training; TOT: task-oriented training; VFT: visual feedback training; AT: acupuncture therapy; rTMS: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; MIT: motor imagery training; PT: proprioceptive training

TUGT

14 studies [7, 15, 21, 22, 31, 33, 36, 37, 40, 42, 44, 51, 55, 57] reported the TUGT, involving 7 rehabilitation protocols: CST, C, BT + CST, WT + CST, PT + CST, VFT + CST, and RRT + CST. The netplot for the TUGT outcome is shown in Fig. 3B.

The random-effects model estimated the between-study standard deviation (τ) to be 1.831, 95% CrI (0.275, 4.719) for the TUGT outcome, with an overall I2 of 8%. This suggests low absolute heterogeneity.

The league table for TUGT is presented in Table 3. Above the diagonal are estimates from PMA, while those below the diagonal represent estimates from NMA [61]. In the PMA for TUGT, BT + CST (MD: 6.2, 95% CrI: 3.1–9.3), PT + CST (MD: 9.4, 95% CrI: 4.5–15.0), and WT + CST (MD: 4.0, 95% CrI: 0.76–7.4) were more effective than CST. Additionally, VFT + CST (MD: 7.6, 95% CrI: 3.7–11.0), WT + CST (MD: 5.7, 95% CrI: 1.4–10.0), and CST (MD: 2.6, 95% CrI: 1.1–4.0) were superior to C. All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). In the NMA for TUGT, the effectiveness of BT + CST (MD: 7.11, 95% CrI: 1.63–10.02), CST (MD: 2.19, 95% CrI: 0.07–3.89), PT + CST (MD: 10.43, 95% CrI: 5.22–15.14), VFT + CST (MD: 7.52, 95% CrI: 2.38–12.62), and WT + CST (MD: 6.07, 95% CrI: 1.61–10.12) were better than C. Furthermore, PT + CST (MD: 8.27, 95% CrI: 3.34–12.98) and VFT + CST (MD: 5.33, 95% CrI: 0.05–10.98) were more effective than CST. All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

League table of TUGT

| Pairwise meta-analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network meta-analysis | BT + CST | 0.35 (-5.8, 6.9) | 6.2 (3.1, 9.3) | ||||

| -7.11 (-10.02, -1.63) | C | -2.6 (-4.0, -1.1) | -7.8 (-15.0, 0.12) | 6.3 (-12.0, 25.0) | -7.6 (-11.0, -3.7) | -5.7 (-10.0, -1.4) | |

| -5 (-7.73, 0.18) | 2.19 (0.07, 3.89) | CST | -9.4 (-15.0, -4.5) | -4.0 (-7.4, -0.76) | |||

| 3.42 (-1.99, 10.29) | 10.43 (5.22, 15.14) | 8.27 (3.34, 12.98) | PT + CST | ||||

| -13.53 (-32.9, 6.42) | -6.76 (-25.78, 12.55) | -8.87 (-27.98, 10.53) | -17.13 (-36.72, 2.89) | RRT + CST | |||

| 0.41 (-4.95, 8.33) | 7.52 (2.38, 12.62) | 5.33 (0.05, 10.98) | -2.93 (-9.71, 4.45) | 14.28 (-5.75, 33.9) | VFT + CST | ||

| -1.14 (-5.57, 5.87) | 6.07 (1.61, 10.12) | 3.86 (-0.32, 8.14) | -4.41 (-10.52, 2.05) | 12.77 (-7.01, 32.21) | -1.45 (-8.27, 4.99) | WT + CST | |

TUGT: Time Up and Go Test; C: conventional rehabilitation therapy; CST: core stability training; BT: Bobath therapy; PT: proprioceptive training; RRT: robotic rehabilitation therapy; VFT: visual feedback training; WT: weight training

FMA-LE

12 studies [15, 21, 23, 35, 38, 45, 47, 49, 50, 52, 55, 56] reported the FMA-LE score, involving 8 rehabilitation protocols: CST, C, MIT + CST, RRT + CST, CKCE + CST, PT + CST, AT + CST, and BT + CST. The netplot for the FMA-LE outcome is shown in Fig. 3C.

The random-effects model estimated the between-study standard deviation (τ) to be 1.688, 95% CrI (0.334, 4.538) for the FMA-LE outcome, with an overall I2 of 7%. This suggests low absolute heterogeneity.

The league table for FMA-LE is presented in Table 4. Above the diagonal are estimates from PMA, while those below the diagonal represent estimates from NMA [61]. In the PMA for FMA-LE, both AT + CST (MD: 7.5, 95% CrI: 2.8–11.0) and MIT + CST (MD: 6.1, 95% CrI: 0.28–12.0) demonstrated superior intervention effects compared to C. All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). In the NMA for FMA-LE, AT + CST (MD: 7.56, 95% CrI: 4.62–10), BT + CST (MD: 5.55, 95% CrI: 0.87–10.31), CST (MD: 2.57, 95% CrI: 0.52–4.73), and MIT + CST (MD: 6.1, 95% CrI: 1.86–10.28) were all more effective than C. Additionally, AT + CST was more effective than both CKCE + CST (MD: 6.81, 95% CrI: 1.07–12.2) and CST (MD: 5, 95% CrI: 1.78–7.57). All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

League table of FMA-LE

| Pairwise meta-analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network meta-analysis | AT + CST | -7.5 (-11.0, -2.8) | -4.9 (-11.0, 0.76) | |||||

| 2.03 (-3.39, 6.82) | BT + CST | -3 (-8.7, 2.7) | ||||||

| 7.56 (4.62, 10) | 5.55 (0.87, 10.31) | C | 0.72 (-5.4, 6.8) | 2.6 (-0.24, 5.8) | 6.1 (0.28, 12.0) | 5.2 (-1.4, 12.0) | 3.2 (-3.2, 9.6) | |

| 6.81 (1.07, 12.2) | 4.82 (-1.88, 11.65) | -0.74 (-5.61, 4.16) | CKCE + CST | |||||

| 5 (1.78, 7.57) | 2.98 (-1.25, 7.17) | -2.57 (-4.73, -0.52) | -1.84 (-7.22, 3.41) | CST | ||||

| 1.47 (-3.79, 6.21) | -0.56 (-6.81, 5.86) | -6.1 (-10.28, -1.86) | -5.36 (-11.79, 1.07) | -3.53 (-8.16, 1.25) | MIT + CST | |||

| 2.37 (-3.79, 8.13) | 0.38 (-6.61, 7.44) | -5.17 (-10.5, 0.13) | -4.43 (-11.7, 2.72) | -2.59 (-8.26, 3.16) | 0.93 (-5.86, 7.65) | PT + CST | ||

| 4.32 (-1.72, 9.99) | 2.35 (-4.65, 9.38) | -3.21 (-8.43, 1.97) | -2.47 (-9.62, 4.61) | -0.64 (-6.21, 5.01) | 2.89 (-3.77, 9.51) | 1.96 (-5.48, 9.37) | RRT + CST | |

FMA-LE: Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Lower Extremity; C: conventional rehabilitation therapy; CST: core stability training; AT: acupuncture therapy; BT: Bobath therapy; CKCE: closed kinematic chain exercise; MIT: motor imagery training; PT: proprioceptive training; RRT: robotic rehabilitation therapy

FAC

13 studies [7, 15, 21, 32, 39, 45–47, 49, 50, 52, 53, 58] reported the FAC score, involving 7 rehabilitation protocols: CST, C, AT + CST, CKCE + CST, MIT + CST, PT + CST, and RRT + CST. The netplot for FAC is shown in Fig. 3D.

The random-effects model estimated the between-study standard deviation (τ) to be 0.5513, 95% CrI (0.287, 1.083) for the FAC outcome, with an overall I2 of 0%. This suggests low absolute heterogeneity.

The league table for FAC is presented in Additional Table S4. Above the diagonal are estimates from PMA, while those below the diagonal represent estimates from NMA [61]. In the PMA for FAC, AT + CST (MD: 0.66, 95% CrI: 0.057–1.3), CKCE + CST (MD: 1.3, 95% CrI: 0.43–2.2), CST (MD: 0.81, 95% CrI: 0.34–1.2), and MIT + CST (MD: 2.0, 95% CrI: 1.2–2.9) showed significantly better outcomes compared to C. Furthermore, AT + CST (MD: 0.97, 95% CrI: 0.13–1.8) was also superior to CST. All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). In the NMA for FAC, AT + CST (MD: 0.97, 95% CrI: 0.26–1.68), CKCE + CST (MD: 1.34, 95% CrI: 0.11–2.59), CST (MD: 0.61, 95% CrI: 0.1–1.11), and MIT + CST (MD: 2.04, 95% CrI: 0.82–3.26) were more effective than C. Additionally, MIT + CST outperformed both RRT + CST (MD: 2.01, 95% CrI: 0.23–3.78) and CST (MD: 1.44, 95% CrI: 0.11–2.76). All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Global consistency and local inconsistency assessment

We conducted global inconsistency tests for all four outcome indicators. In addition, we performed node-splitting analyses to assess local inconsistency within the closed loops in the netplots. The node-splitting plots for the four outcome measures are presented in Additional Figs. 1–4. For BBS, the Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) was 133.07920 under the consistency model and 133.22094 under the inconsistency model. The difference between the two models was less than 5, indicating good model fit and no significant inconsistency in the network. To further assess the agreement between direct and indirect evidence in the NMA, we performed a local inconsistency test using the node-splitting method for the BBS outcome. The node-splitting plot for BBS is presented in Additional Fig. 1. The results showed that the differences between direct and indirect effects were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) for all comparisons, indicating good consistency across the network and no significant local inconsistency. For TUGT, the DIC was 55.26557 under the consistency model and 53.07518 under the inconsistency model. The small difference (< 5) suggests good model fit and no significant global inconsistency. However, the node-splitting analysis for TUGT (Additional Fig. 2) revealed statistically significant inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons in the following pairs: C vs. BT + CST (p = 0.0279), CST vs. BT + CST (p = 0.02685), and CST vs. C (p = 0.021775), suggesting the presence of local inconsistency in these comparisons. All other comparisons showed no significant differences (p > 0.05). For FMA-LE, the DIC was 47.55670 under the consistency model and 47.82351 under the inconsistency model. The small difference indicates a good model fit and no significant global inconsistency. The node-splitting plot for FMA-LE is shown in Additional Fig. 3. The results revealed no statistically significant differences between direct and indirect effects in all comparisons (p > 0.05), indicating good consistency within the FMA-LE network and no significant local inconsistency. For FAC, the DIC was 49.44623 under the consistency model and 49.61022 under the inconsistency model. The small difference again suggests a good model fit and no global inconsistency. The node-splitting analysis for FAC is illustrated in Additional Fig. 4. All comparisons showed no statistically significant differences between direct and indirect effects (p > 0.05), indicating good agreement and no significant local inconsistency in the FAC network.

SUCRA ranking

SUCRA (Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking Curve) values provide clinicians with a probabilistic ranking of the relative efficacy of interventions, indicating the likelihood of an intervention being the best or among the best options. However, SUCRA does not directly reflect the absolute magnitude of treatment effects. When SUCRA values are similar, the actual effectiveness of interventions may be comparable, and small differences in rank may lack clinical significance. In such cases, the estimated effect sizes (MD) and corresponding 95% credible intervals (CrI) from the league table should be jointly considered for interpretation. The cumulative probability rankings for the four outcome measures are presented in Additional Table S5, with the cumulative probability line charts shown in Figs. 3E-H. The results indicate that NMES + CST (SUCRA = 90.82%) seems to be the most effective core stability training combination for improving the BBS score in stroke patients. The SUCRA ranking is as follows: NMES + CST (SUCRA = 90.82%) >rTMS + CST (SUCRA = 71.89%) >TOT + CST (SUCRA = 70.90%) >AT + CST (SUCRA = 65.62%) >WT + CST (SUCRA = 64.09%) >PT + CST (SUCRA = 58.29%) >MIT + CST (SUCRA = 40.36%) >VFT + CST (SUCRA = 38.86%) >RRT + CST (SUCRA = 33.65%) >CST (SUCRA = 31.59%) >BT + CST (SUCRA = 27.51%) >C (SUCRA = 6.41%). The results also show that PT + CST (SUCRA = 93.24%) seems to be the most effective core stability training combination for reducing the TUGT in stroke patients. The SUCRA ranking is as follows: PT + CST (SUCRA = 93.24%) >VFT + CST (SUCRA = 72.41%) >BT + CST (SUCRA = 68.10%) >WT + CST (SUCRA = 58.97%) >CST (SUCRA = 31.26%) >C (SUCRA = 13.32%) >RRT + CST (SUCRA = 12.69%). For improving the FMA-LE score in stroke patients, AT + CST (SUCRA = 90.83%) seems to be the most effective combination. The SUCRA ranking is as follows: AT + CST (SUCRA = 90.83%) >MIT + CST (SUCRA = 74.28%) >BT + CST (SUCRA = 67.99%) >PT + CST (SUCRA = 63.59%) >RRT + CST (SUCRA = 42.84%) >CST (SUCRA = 34.98%) >CKCE + CST (SUCRA = 18.07%) >C (SUCRA = 7.42%). Lastly, MIT + CST (SUCRA = 93.87%) seems to be the most effective core stability training combination for improving the FAC score in stroke patients. The SUCRA ranking is as follows: MIT + CST (SUCRA = 93.87%) >CKCE + CST (SUCRA = 73.45%) >AT + CST (SUCRA = 60.25%) >PT + CST (SUCRA = 56.03%) >CST (SUCRA = 39.70%) >RRT + CST (SUCRA = 16.98%) >C (SUCRA = 9.72%).

Cluster analysis

The two-dimensional clustering analysis graphs for the four outcome indicators are shown in Fig. 4A–C. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, PT + CST (SUCRA = 58.29%/SUCRA = 93.24%) and WT + CST (SUCRA = 64.09%/SUCRA = 58.97%) demonstrated superior efficacy in improving BBS scores and reducing TUGT time in stroke patients. Figure 4B shows that AT + CST (SUCRA = 65.62%/SUCRA = 90.83%) and PT + CST (SUCRA = 58.29%/SUCRA = 63.59%) were effective in enhancing both BBS and FMA-LE scores. Figure 4C indicates that AT + CST (SUCRA = 65.62%/SUCRA = 60.25%) and PT + CST (SUCRA = 58.29%/SUCRA = 56.03%) contributed to significant improvements in BBS and FAC scores. In conclusion, PT + CST (SUCRA = 58.29%/SUCRA = 93.24%/SUCRA = 63.59%/SUCRA = 56.03%) and AT + CST (SUCRA = 65.62%/SUCRA = 90.83%/SUCRA = 60.25%) seem to be the most effective interventions for lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients.

Fig. 4.

Cluster analysis chart. A: Cluster analysis of Berg Balance Scale and Time Up and Go Test; B: Cluster analysis of Berg Balance Scale and Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Lower Extremity; C: Cluster analysis of Berg Balance Scale and Functional Ambulation Category Scale. BBS: Berg Balance Scale; TUGT: Time Up and Go Test; FMA-LE: Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Lower Extremity; FAC: Functional Ambulation Category Scale; C: conventional rehabilitation therapy; CST: core stability training; BT: Bobath therapy; NMES: neuromuscular electrical stimulation; RRT: robotic rehabilitation therapy; WT: weight training; TOT: task-oriented training; VFT: visual feedback training; AT: acupuncture therapy; CKCE: closed kinematic chain exercise; rTMS: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; MIT: motor imagery training; PT: proprioceptive training

Publication bias

The funnel plots for the four outcome indicators are shown in Fig. 3I–L, corresponding to BBS, TUGT, FMA-LE, and FAC, respectively, to assess publication bias. As observed in Fig. 3I, although the funnel plot appears overall symmetrical, the small angle between the reference line and the X-axis, along with some points outside the funnel, suggests a potential publication bias in the BBS outcome. In Fig. 3J, all nodes are within the funnel, with overall symmetry and a larger angle between the reference line and the X-axis, indicating a low likelihood of publication bias for the TUGT outcome. Figure 3K shows that only a few nodes fall outside the funnel, and the reference line forms a large angle with the X-axis, suggesting minimal publication bias for the FMA-LE outcome. Similarly, Fig. 3L reveals that only a few nodes lie outside the funnel, with a large angle between the reference line and the X-axis, indicating a low probability of publication bias for the FAC outcome.

Sensitivity analysis

For the BBS outcome, after excluding studies with a high risk of bias, the SUCRA rankings were as follows: rTMS + CST (SUCRA = 76.14%) > TOT + CST (SUCRA = 73.92%) > AT + CST (SUCRA = 69.32%) > WT + CST (SUCRA = 67.90%) > PT + CST (SUCRA = 60.83%) > MIT + CST (SUCRA = 41.98%) > BT + CST (SUCRA = 41.98%) > VFT + CST (SUCRA = 41.96%) > RRT + CST (SUCRA = 35.35%) > CST (SUCRA = 33.78%) > C (SUCRA = 6.82%). Since both studies involving the NMES + CST intervention were excluded due to high risk of bias, this intervention was not included in the BBS outcome analysis. The overall rankings of the remaining interventions did not change significantly, suggesting that the BBS outcome is robust.

For the TUGT outcome, after excluding high-risk studies, the SUCRA rankings were as follows: PT + CST (SUCRA = 93.57%) > BT + CST (SUCRA = 79.53%) > VFT + CST (SUCRA = 66.68%) > WT + CST (SUCRA = 54.94%) > CST (SUCRA = 31.06%) > C (SUCRA = 12.83%) > RRT + CST (SUCRA = 11.39%). The rankings remained stable after excluding high-risk studies, suggesting that this outcome is also robust.

Discussion

This systematic review and network meta-analysis (NMA) aimed to compare the efficacy of various core stability training (CST) combination therapies and identify the optimal strategies for improving lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients. The NMA incorporated 43 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), with a total of 2,227 stroke patients suffering from lower extremity dysfunction. Our findings suggest that specific CST combination therapies demonstrate superior effects for different aspects of lower extremity recovery: NMES + CST appeared most beneficial for balance, PT + CST for functional mobility, AT + CST for motor ability, and MIT + CST for walking ability. Overall, the comprehensive analysis indicated that AT + CST and PT + CST may represent the most robust approaches.

The Berg Balance Scale (BBS) reflects the balance ability of stroke patients, and NMES + CST seems to be the optimal intervention for improving balance in stroke patients. NMES is a low-frequency electrical stimulation therapy that generates specific stimulating effects on different muscle areas through low-frequency pulse currents [62]. Carson and Buick [63] summarized previous research and found that NMES can effectively increase the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the serum. BDNF plays an important role in promoting the plasticity of the nervous system. Based on this, NMES can promote the remodeling of the nervous system function in stroke patients by increasing the level of BDNF in the serum, thereby enhancing the balance ability of stroke patients. Additionally, Nozoe et al. [64] found that compared to conventional rehabilitation care, NMES effectively reduces the degree of quadriceps muscle atrophy in stroke patients. Yang et al. [65] demonstrated that compared to traditional stretching exercises, NMES significantly reduces ankle joint muscle spasm and increases muscle strength in stroke patients. Clearly, NMES can reduce muscle atrophy and spasm and enhance muscle strength in specific areas by directly stimulating particular muscle regions. CST primarily focuses on training the lumbar spine, pelvis, and hip joint areas. By progressively tailoring rehabilitation exercises to the specific conditions of stroke patients, it can enhance trunk control, improve postural control during standing and movement, and promote balance recovery [66]. In summary, combining NMES with CST not only promotes the reorganization of the neural systems related to balance in stroke patients but also enhances the efficiency of core stability training. This combination increases core muscle strength, reduces lower extremity muscle spasm, and significantly improves balance through the synergistic effect of both interventions [16, 30]. Unfortunately, the studies included in this analysis did not report the other three outcome measures related to the NMES + CST protocol, which is regrettable. Balance is fundamental to human movement, and NMES + CST shows great potential for future research in treating lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients. However, clinicians should be aware of contraindications when using NMES, such as in patients with cardiac pacemakers, a history of epilepsy, or skin sensitivity or lesions at the electrode sites. Careful patient screening is essential. Moreover, the selection of stimulation parameters should be individualized to avoid discomfort or excessive muscle fatigue.

The Timed Up and Go Test (TUGT) reflects the functional mobility of the lower extremity in stroke patients, and the optimal intervention for improving functional mobility seems to be proprioceptive training combined with core stability training (PT + CST). Studies have demonstrated that a significant proportion, at least 30%, of stroke patients suffer from proprioceptive deficits [67]. These deficits are not only prevalent but also have a substantial negative impact on limb motor function and the patients’ overall independence in daily life [67]. The impaired proprioception often results in difficulties with balance, coordination, and mobility, which further hinders the patients’ ability to perform routine tasks without assistance [3]. A decline in lower extremity motor function is associated with a decrease in proprioceptive function in stroke patients [68]. Proprioception refers to the body’s innate ability to detect the position and movement of its limbs, encompassing muscle sensation, postural balance, and joint stability [69]. Proprioceptive training plays a crucial role in enhancing spatial awareness, improving postural stability, and promoting balance. Additionally, it contributes to better motor control of the lower extremities, ultimately supporting functional mobility and movement coordination [70–72]. Chae et al. [11] divided stroke patients into a PT group and a conventional physical therapy group. The PT group underwent four weeks of PT, while the control group received four weeks of conventional physical therapy. The results showed that after treatment, patients in the PT group demonstrated significantly better lower extremity function than those in the control group. Building on this study, Peng et al. [51] combined PT with CST and found that the intervention of PT + CST was significantly more effective than CST alone. CST, when combined with PT, helps patients stabilize the muscles of the pelvis and trunk during movement, creating stable support points for upper and lower extremity movements and coordinating the force exerted by both limbs. This optimizes the generation, transmission, and control of force, enabling stroke patients to control their movements more stably during testing, thereby reducing the time required for the TUGT [73]. PT + CST also achieved excellent intervention effects in improving stroke patients’ BBS scores (56.75%), FAC scores (53.80%), and FMA-LE scores (63.59%). PT + CST seems to be the best intervention for improving functional mobility of the lower extremity and treating lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients. PT—especially when combined with CST—may be of relatively high intensity for certain patients. For those who are severely frail, have significant cognitive impairment, acute pain, or markedly poor balance, the type, intensity, and duration of PT should be carefully tailored and progressed gradually to avoid excessive fatigue, musculoskeletal injuries, or increased fall risk.

Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Lower Extremity (FMA-LE) reflects the lower extremity motor ability of stroke patients, and AT + CST seems to be the optimal rehabilitation intervention for improving lower extremity motor ability in stroke patients. AT refers to acupuncture, which, guided by traditional Chinese medicine theory, involves inserting needles (usually filiform needles) into specific parts of the body at certain angles. Manipulative techniques such as twisting and lifting are used to stimulate these areas to achieve therapeutic effects. AT stimulates specific areas of the brain to improve the excitability of the brain lesion region and its surrounding neural tissue [74]. It promotes the establishment of collateral circulation in the cerebral blood vessels, rapidly relieves vascular spasm, dilates blood vessels, reduces resistance, and increases cerebral blood flow [74]. This helps improve ischemia in the brain cells around the lesion, salvaging ischemic tissue surrounding necrotic areas, promoting the recovery of “shocked” neurons, and accelerating the repair and reconstruction of the central nervous system [74, 75]. As a result, it helps patients better control limb movement. In addition, AT, by stimulating specific acupuncture points in stroke patients, can reduce pain, alleviate muscle spasm, and promote muscle recovery. A study by Wang et al. [23] found that the AT + CST combined approach significantly reduced the concentrations of neurodamage biomarkers and oxidative stress markers in stroke patients. This approach effectively inhibits oxidative stress responses, reduces the extent of neurological damage, and promotes the remodeling of the central nervous system, ultimately restoring lower extremity motor ability in stroke patients [23]. In conclusion, AT + CST improves lower extremity motor function in stroke patients by promoting neuroplasticity, enhancing trunk and lower extremity muscle strength, and reducing pain. AT + CST also demonstrates significant efficacy in improving BBS (79.15%) and FAC (65.46%) scores in stroke patients, making it an effective and optimal intervention for treating lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients. Although acupuncture is generally considered safe, minor adverse events such as slight bleeding, bruising, soreness at the needle site, or occasional vasovagal reactions (e.g., fainting) may occur. It is important that the intervention is administered by qualified professionals.

Notably, all included studies evaluating the combined intervention of AT + CST were conducted in China [23, 45, 50]. This geographic concentration significantly limits the generalizability of the favorable findings. As a core component of traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture is widely understood, culturally accepted, and often positively anticipated by patients in China. Such cultural familiarity and patient expectations may enhance perceived treatment effects through placebo/contextual mechanisms or improved adherence, effects that may not be replicated to the same extent in populations less familiar with or more skeptical of acupuncture. Moreover, the specific acupuncture protocols used in these Chinese studies—including acupoint selection, needling techniques, session duration and frequency—as well as the depth of training and clinical expertise of the acupuncturists, may differ from practices common in other regions. Given the inherent complexity of acupuncture as an intervention, standardizing its application is challenging, and variations in implementation could lead to different outcomes in non-Chinese settings. Therefore, while the findings on AT + CST are encouraging, it is critical to conduct high-quality randomized controlled trials in diverse international populations and healthcare settings to establish robust evidence. Such studies are essential not only to confirm the efficacy of this combined intervention but also to explore how it might need to be adapted across different cultural contexts and patient expectations. This would help determine the true generalizability and clinical value of AT + CST in post-stroke lower limb rehabilitation.

The Functional Ambulation Category Scale (FAC) reflects the walking ability of stroke patients, and MIT + CST seems to be the optimal rehabilitation approach for improving walking ability in stroke patients. MIT is a mental rehearsal exercise where the movement is imagined rather than actually performed. This technique improves motor ability by repeatedly imagining physical movements [76]. After a stroke, many motor dysfunctions occur, and the recovery of motor function mainly depends on the plasticity of the brain’s structure and function [77]. Studies have shown that the brain areas activated by MIT are the same or similar to those activated by actual physical movement, such as the premotor cortex and supplementary motor area [78, 79]. Additionally, there is a correlation between the neural control networks of both. Repeated MIT can cause changes in brain neural networks, promoting both structural and functional remodeling of the motor cortex in the affected areas [80]. MIT can enhance sensory information input from peripheral receptors and neural impulses from the brain, which in turn activates latent neural pathways and dormant synapses [52]. This accelerates neural system remodeling and functional reorganization, reducing the extent of neurological impairment in stroke patients [46]. Building upon MIT, CST activates core muscle groups and stimulates the afferent sensory input from peripheral receptors as well as the efferent neural output from the central nervous system [52]. This helps to improve lower extremity support and control, balance, and coordination, reduce the risk of falls, and enhance the stability of walking [52]. The effectiveness of MIT may depend on the patient’s ability to generate vivid mental representations of movement. For individuals with severe cognitive deficits, aphasia-related comprehension difficulties, or a lack of imagination capacity, the feasibility and effectiveness of MIT may be limited.

This study has certain limitations. This study only retrieved literature from six medical databases. Although this covers the majority of journals in medicine and health sciences, it may have led to the omission of some studies that met the inclusion criteria. The review was primarily limited to studies published in English and Chinese, potentially omitting relevant research published in other languages, which could introduce a language bias. While we aimed to include studies where stroke was confirmed by CT or MRI, the explicitness of reporting varied across studies. For a small number of studies, reliance was placed on established clinical diagnostic criteria where neuroimaging confirmation was not explicitly detailed for all participants. This variation in the reported rigor of diagnostic confirmation could introduce a minor degree of heterogeneity, although all included patients were clearly defined as stroke survivors with lower extremity dysfunction. Our search strategy focused on published articles and did not include a systematic search for unpublished studies or grey literature, which might leave some relevant evidence unidentified and could contribute to publication bias. While our NMA aimed to identify optimal combinations, the primary studies included often provided limited and heterogeneous reporting on adverse events, contraindications specific to the combined therapies, or how these varied across distinct stroke subpopulations (e.g., based on stroke severity, lesion location, time since stroke, or specific comorbidities). This lack of granular safety data restricts our ability to draw robust conclusions about the risk-benefit profile or precise applicability of each combination for every stroke patient. Additionally, the potential for increased patient and healthcare system burden (e.g., treatment time, cost, patient fatigue, complexity of scheduling) associated with combination therapies compared to single interventions was not systematically evaluable from the included studies. These practical factors are important considerations for clinical implementation. Our NMA identified the “optimal” combinations based on the average effects across heterogeneous patient populations included in the trials. This overall ranking does not imply “optimality” for every specific patient subgroup (e.g., based on age, gender, stroke type, severity of dysfunction, or time since stroke). Due to the use of aggregate data from the included studies, we could not perform subgroup analyses to determine tailored optimal strategies for these specific populations. Future research should focus on identifying optimal intervention strategies tailored to individual patient characteristics, which would provide valuable insights for personalized rehabilitation in stroke populations. The definition of “optimal” in this NMA is predominantly based on improvements assessed at the end of the intervention period or at short-term follow-up, reflecting the outcome reporting in the majority of included RCTs. Comprehensive data on the long-term sustainability of these improvements (e.g., at 6 months or 1year post-intervention) were sparse or inconsistently reported across the primary studies, which precluded a robust analysis of long-term “optimality”. Consequently, whether the identified “optimal” short-term interventions also confer the most sustained long-term benefits remains an important question for future research, which should prioritize longer follow-up durations. A fundamental assumption for the validity of NMA is transitivity, implying that the set of studies forming indirect comparisons are sufficiently similar in all prognostically important characteristics other than the interventions being compared. We qualitatively evaluated the distribution of key clinical and methodological factors across studies. While no major obvious imbalances were identified that would clearly violate transitivity for most comparisons, some degree of heterogeneity in these factors is inevitable in any collection of trials. Such differences, if they act as effect modifiers, could potentially bias indirect estimates and thus impact the overall NMA findings. This remains a limitation, as transitivity can rarely be definitively proven with aggregate-level data. Most of the outcomes used in this study were based on clinical rating scales, which may involve some degree of subjectivity. In contrast, biomechanical or neurophysiological assessments can reduce this subjectivity and may be more sensitive to subtle changes. Moreover, they can provide mechanistic insights into how interventions work, such as changes in muscle activation patterns, cortical excitability, or gait kinematics, rather than simply indicating changes in functional scores. Future studies could consider using three-dimensional motion capture systems for detailed gait and kinematic analysis, force platforms for postural control assessment, isokinetic dynamometers for muscle strength evaluation, and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to detect changes in corticospinal excitability and plasticity.

Conclusion

NMES + CST, PT + CST, AT + CST, and MIT + CST are four effective core stability training combination therapies. Comprehensive evaluation results indicate that AT + CST or PT + CST seems to be the optimal core stability training combination therapy for lower extremity dysfunction in stroke patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AT

Acupuncture therapy

- BBS

Berg Balance Scale

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BT

Bobath therapy

- C

Conventional rehabilitation therapy

- CKCE

Closed kinematic chain exercise

- CNKI

China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- CSCD

Chinese Science Citation Database

- CST

Core stability training

- DIC

Deviance Information Criterion

- FAC

Functional Ambulation Category Scale

- FMA-LE

Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Lower Extremity

- MIT

Motor imagery training

- NMA

Network meta-analysis

- NMES

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation

- PMA

Pairwise meta-analyses

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PT

Proprioceptive training

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- ROB2.0

Risk of Bias Tool

- RRT

Robotic rehabilitation therapy

- rTMS

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

- SinoMed

China Biology Medicine

- SUCRA

Surface under the cumulative ranking curve

- TOT

Task-oriented training

- TUGT

Timed Up and Go Test

- VFT

Visual feedback training

- WT

Weight training

Author contributions

LG proposed the topic and received funding support. LG, KZ and DW formulated the specific research question and protocol of the study. KZ and LG prepared the first draft of the review paper, with contributions and editing from DW and CD to the subsequent drafts. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the financial support from the construction project of the 2025 Industry Science and Technology Collaborative Innovation Center (SL2024B04J00048) provided by Guangzhou Science and Technology Bureau, as well as the 2024–2025 Science and Technology Innovation and Sports Culture Development Project provided by Guangdong Provincial Sports Bureau (GDSS2024N029).

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Brainin M, Norrving B, Martins S, Sacco RL, Hacke W, et al. World stroke organization (WSO): global stroke fact sheet 2022. Int J Stroke: Official J Int Stroke Soc. 2022;17(1):18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li S, Spasticity. Motor recovery, and neural plasticity after stroke. Front Neurol. 2017;8:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Zheng K, Li L, Zhou Y, Gong X, Zheng G, Guo L. Optimal proprioceptive training combined with rehabilitation regimen for lower limb dysfunction in stroke patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1503585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee KE, Choi M, Jeoung B. Effectiveness of rehabilitation exercise in improving physical function of stroke patients: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ryan M, Rössler R, Rommers N, Iendra L, Peters EM, Kressig RW, et al. Lower extremity physical function and quality of life in patients with stroke: a longitudinal cohort study. Qual Life Research: Int J Qual Life Aspects Treat Care Rehabilitation. 2024;33(9):2563–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabanas-Valdés R, Bagur-Calafat C, Girabent-Farrés M, Caballero-Gómez FM, Hernández-Valiño M, Urrútia Cuchí G. The effect of additional core stability exercises on improving dynamic sitting balance and trunk control for subacute stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(10):1024–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haruyama K, Kawakami M, Otsuka T. Effect of core stability training on trunk function, standing balance, and mobility in stroke patients. Neurorehabilit Neural Repair. 2017;31(3):240–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kibler WB, Press J, Sciascia A. The role of core stability in athletic function. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). 2006;36(3):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Guo L, Wu Y, Li LJAS. Dynamic core flexion strength is important for using arm-swing to improve countermovement jump height. Appl Sci. 2020;10(21):7676. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H, Yin H, Yi Y, Liu C, Li C. Effects of different rehabilitation training on balance function in stroke patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Archives Med Science: AMS. 2023;19(6):1671–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chae SH, Kim YL, Lee SM. Effects of phase proprioceptive training on balance in patients with chronic stroke. J Phys Therapy Sci. 2017;29(5):839–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Li H, Liu Y, Liang W, Zhang L, Zhou F, et al. The effect of electromyographic feedback functional electrical stimulation on the plantar pressure in stroke patients with foot drop. Front NeuroSci. 2024;18:1377702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong Q. Effect of Fuzheng Butu acupuncture and moxibustion therapy on ischemic stroke and its influence on balance function. Chin Gen Pract. 2019;22(S1):170–2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DH, In TS, Jung KS. Effects of robot-assisted trunk control training on trunk control ability and balance in patients with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Technol Health Care: Official J Eur Soc Eng Med. 2022;30(2):413–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang B, Wang D, Lv L. Effect of proprioceptive training and core stability training on lower limbs motor function and balance in patients with hemiplegia after stroke. Chin J Rehabilitation Theory Pract. 2014;20(12):1109–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko EJ, Chun MH, Kim DY, Yi JH, Kim W, Hong J. The additive effects of core muscle strengthening and trunk NMES on trunk balance in stroke patients. Annals Rehabilitation Med. 2016;40(1):142–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salgueiro C, Urrútia G, Cabanas-Valdés R. Influence of core-stability exercises guided by a telerehabilitation app on trunk performance, balance and gait performance in chronic stroke survivors: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Cipriani A, Higgins JP, Geddes JR, Salanti G. Conceptual and technical challenges in network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):130–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutton B, Catala-Lopez F, Moher D. The PRISMA statement extension for systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analysis: PRISMA-NMA. Med Clin (Barc). 2016;147(6):262–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chitra J, Sharan R. A comparative study on the effectiveness of core stability exercise and pelvic proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation on balance, motor recovery and function in hemiparetic patients: a randomized clinical trial. Romanian J Phys Therapy. 2015;21(36).

- 21.Min JH, Seong HY, Ko SH, Jo WR, Sohn HJ, Ahn YH, et al. Effects of trunk stabilization training robot on postural control and gait in patients with chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Rehabilitation Res Int Z fur Rehabilitationsforschung Revue Int De Recherches De Readaptation. 2020;43(2):159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SM, Jang SH. The effect of a trunk stabilization exercise program using weight loads on balance and gait in stroke patients: a randomized controlled study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2022;51(3):407–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shasha W, Jin Z, Weizhong Z, Xianchang C, Ying Z. Effects of balance acupuncture combined with core stability training on motor function of stroke. World Chin Med. 2021;16(8):1297–301. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical Res ed). 2019;366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Hao X, Liu JH, Huang JP. Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions for primary dysmenorrhoea: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. BMJ evidence-based Med. 2024;29(3):162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torres-Costoso A, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Reina-Gutiérrez S, Álvarez-Bueno C, Guzmán-Pavón MJ, Pozuelo-Carrascosa DP, et al. Effect of exercise on fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis comparing different types of exercise. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103(5):970–e8718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Valkenhoef G, Lu G, de Brock B, Hillege H, Ades AE, Welton NJ. Automating network meta-analysis. Res Synthesis Methods. 2012;3(4):285–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoo SD, Jeong YS, Kim DH, Lee M, Noh SG, Shin YW, et al. The efficacy of core strengthening on the trunk balance in patients with subacute stroke. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2010;34(6):677–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verma S, Patra A, Kumar N. To compare the effectiveness of Bobath approach along with core stability training versus Bobath approach along with conventional therapy on trunk function and sitting balance in stroke patients. J NeuroQuantology. 2022;20(13):3699. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park M, Seok H, Kim SH, Noh K, Lee SY. Comparison between neuromuscular electrical stimulation to abdominal and back muscles on postural balance in post-stroke hemiplegic patients. Annals Rehabilitation Med. 2018;42(5):652–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadeem I, Butt SK, Mubeen I, Razzaq A. Effects of core muscles strengthening exercises with routine physical therapy on trunk balance in stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. JPMA J Pakistan Med Association. 2024;74(5):848–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahmood W, Ahmed Burq HSI, Ehsan S, Sagheer B, Mahmood T. Effect of core stabilization exercises in addition to conventional therapy in improving trunk mobility, function, ambulation and quality of life in stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabilitation. 2022;14(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee J, Jeon J, Lee D, Hong J, Yu J, Kim J. Effect of trunk stabilization exercise on abdominal muscle thickness, balance and gait abilities of patients with hemiplegic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation. 2020;47(4):435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeong S, Chung Y. Task-oriented training with abdominal drawing-in maneuver in sitting position for trunk control, balance, and activities of daily living in patients with stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;11(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Dubey L, Karthikbabu S, Mohan D. Effects of pelvic stability training on movement control, hip muscles strength, walking speed and daily activities after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Annals Neurosciences. 2018;25(2):80–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung EJ, Kim JH, Lee BH. The effects of core stabilization exercise on dynamic balance and gait function in stroke patients. J Phys Therapy Sci. 2013;25(7):803–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]