Abstract

Background

The effects of smartphone use on mental health and brain activity in adolescents have received much attention; however, the effects on older adults have received little attention. As more and more older adults begin to use smartphones, exploring the effects of nonaddictive smartphone use on mental health, cognitive function, and brain activity in older adults is imperative.

Objective

This study aimed to examine differences in cognitive performance, emotional symptoms (depression, anxiety, and insomnia), and brain functional activity between older adults who use smartphones and those who do not.

Methods

A total of 1014 community-dwelling older adults aged 60 years and above were surveyed in a rural area of China. Participants were categorized into 2 groups based on their smartphone use status. The Patient Health Questionnaire, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale, Insomnia Severity Index, and Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic were used to evaluate the symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and cognitive function of the participants by trained medical staff. To explore neural mechanisms, a subsample of 130 participants (89 smartphone users and 41 nonusers) was selected using stratified random sampling for resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning. Participants with contraindications for magnetic resonance imaging (eg, metal implants or claustrophobia) or who refused to participate were excluded. Functional brain activity was analyzed and compared between groups.

Results

Among all 1015 older adults, 641 reported using smartphones, while 373 reported never using smartphones. Older adults who use smartphones exhibited better cognitive function compared with those who never use smartphones (z=3.806, P<.001), especially in the domains of fluency (z=3.025, P=.002) and abstraction (z=5.311, P<.001). However, there were no significant differences in levels of depression (z=0.689, P=.49), anxiety (z=0.934, P=.35), and insomnia (z=0.340, P=.73). In terms of the magnetic resonance imaging findings, a total of 130 participants completed functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning, including 89 who use smartphones and 41 who never use smartphones, and results showed that older adults who were smartphone users exhibited higher degree centrality values in the left parahippocampal gyrus.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that smartphone use among older adults is associated with better cognitive performance and fewer emotional symptoms, potentially linked to enhanced brain activity in key cognitive regions. Promoting digital engagement may offer cognitive and emotional benefits for aging populations. Longitudinal studies are warranted to examine causal relationships.

Introduction

The aging of the population has become a global issue. According to the World Population Prospects 2022, published by the United Nations Population Division, the older population is projected to reach 994 million by 2030 worldwide [1]. Aging means a decline in physical ability and function, and in the process, they gradually become disconnected from society [2], participate less in social activities [3], and sleep duration and quality decline significantly [3,4]. At the same time, the aging process is associated with a high risk of cognitive impairment [5], encompassing various cognitive domains such as reaction time, sensory processing, attention, memory, reasoning, and executive functioning [6]. This cognitive aging not only affects their daily life abilities but also has the potential to lead to dementia ultimately [7]. Additionally, a decline in physiological functioning and a decrease in social participation are associated with a higher risk of depression in older adults [8], which impacts the quality of life of affected individuals and their families and presents a considerable challenge for society as a whole. Therefore, there is increasing attention given to how to improve cognitive function and reduce the risk of depression among older adults.

As an important invention of the 21st century, smartphones have become an indispensable part of people’s lives. In recent years, the application scenarios and user demographics of smartphones have expanded, with many older adult individuals in rural areas also beginning to use smartphones for simple recreational activities and socializing through chat applications [9]. While researchers have long focused on the effects of smartphone use on mental health and cognitive function, research has focused on adolescents, and the effects on older adults have been less explored. Current studies of adolescents have generally linked smartphone use to reduced sleep duration, decreased sleep quality, and a higher risk of depression [10,11]. However, it should be emphasized that this is largely due to the addictive use of smartphones [12,13]. Objectively speaking, as an important tool in daily life and work, mobile phones play an irreplaceable role. Healthy use of mobile phones can help individuals broaden their horizons, seek support for emotional needs, provide opportunities for leisure and entertainment, and may improve their cognitive functioning. Compared with adolescents, older adults have better self-control and less addictive behaviors [14,15]. So, could nonaddictive smartphone use help improve cognitive function in older adults and lower their risk of depression?

Furthermore, previous studies have identified abnormal brain activity in young individuals with smartphone addiction, such as a reduction in fronto-limbic resting-state functional connectivity and smaller gray matter volume in the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex [16,17]. According to it, we assume that there are also neural activity changes among older adults who use smartphones, which could be the potential mechanism explaining their cognitive performance.

Therefore, we designed this study to explore smartphone usage among older adults in a Chinese village and designed a cross-sectional study to explore: (1) the effect of smartphone use on cognitive function in older adults; (2) the effects of smartphone use on sleep and mental health; (3) the effect of smartphone use on brain activity among older adults.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study is a cross-sectional study, and the recruitment process was conducted as in the flowchart presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The flowchart of the whole study. fMRI: functional magnetic resonance imaging; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; MoCA-B: Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; PSU: problematic smartphone use; SAS-SV: Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version.

Sample Size Calculation

For the appropriate sample size for the survey, we used G*Power (version 3.1; UC Regents), a widely recognized software tool for conducting power analyses. The calculation was based on a 2-tailed independent-samples t test, as we aimed to compare group differences in cognitive function (Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic [MoCA-B] scores) between smartphone users and nonusers. The effect size was estimated at Cohen d=0.3. The significance level (α) was set to .05, and the desired statistical power was .90, which is commonly used to ensure a sufficient likelihood of detecting true effects. A required sample size of 235 participants per group, with a total of 470 participants for both groups, was combined.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This study was conducted from June 2023 to August 2023 in a village in Hubei, China, and all participants are registered local residents aged over 60 years. We recruited them by entrusting the village committee to spread an oral recruitment notice and then hired a fixed place in the village to complete the subsequent investigation. Data acquisition was completed by 7‐10 investigators with standardized training. A total of 1030 participants were initially screened for this study.

Inclusion criteria were the following: (1) voluntarily participating in this study and providing written informed consent; (2) participants were able to understand the meaning of the questions in the questionnaire and complete the questionnaire.

Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) a history of mental illness or a family history of mental illness; (2) recent major setbacks; (3) presence of endocrine or organic diseases; (4) Addictive mobile phone use (a total score of the Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version [SAS-SV] ≥31 for males or ≥33 for females).

Ethical Considerations

The Ethics Committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University approved this study. After a complete description of this study, written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and secondary analysis of the data was allowed. The research data are anonymous, and the privacy of the subjects will not be disclosed. Individual participants cannot be identified in any images of the manuscripts or supplementary materials. Each participant in this project received a compensation of CNY ¥50 (US $6.97) as a participation fee and CNY ¥20 (US $2.79) for travel reimbursement. The data for this study were collected prospectively to explore the effects of mobile phone use on older adults and were not part of any other study.

Measures

First, general demographic data of all participants were acquired, including age, gender, and years of education. Subsequently, the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia were assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [18], Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) [19], and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [20], respectively. The Cronbach α values for PHQ-9, GAD-7, and ISI were 0.89, 0.93, and 0.82, respectively, demonstrating good internal consistency [18,21,22].

For smartphone usage, participants were asked a question, “Do you use a smartphone in your daily life?” If the answer was no, the investigation of smartphone usage was concluded. If the answer was yes, participants were further queried about their most frequently used smartphone function and the average number of hours they spent using the smartphone per day. Additionally, the symptom of problematic smartphone use (PSU) was evaluated using SAS-SV [23]. A total score of SAS-SV ≥31 for males or ≥33 for females indicated PSU.

The cognitive function was assessed by the MoCA-B, which has demonstrated excellent validity in assessing cognitive function in poorly educated older adults [24]. The MoCA-B assessed cognitive domains of executive function, orientation, memory, abstraction, visual perception, and attention. The maximum score attainable is 30. To overcome the bias of education, 1 point was added for those participants with ≤4 years of education and 2 points for nonreaders (adjusted total scores ≤30).

Statistical Analysis

A total of 16 participants were excluded due to PSU. Finally, a total of 1014 participants were included in the statistical analysis and subsequently divided into 2 groups, “use smartphone” and “never use smartphone.” All analyses were carried out in SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp).

First, the demographic characteristics were described using means and SDs or percentages. Differences between groups were assessed using independent sample t tests and chi-square tests. Then, the MoCA-B characteristics of the 2 groups were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction. The severity of depression, anxiety, and insomnia was recorded ranging from 0 (none) to 3 (severe) or 0 (none) to 2 (severe), based on the scores of PHQ-9 (0‐3), GAD-7 (0‐2), and ISI (0‐3), respectively, and compared with Mann-Whitney U tests.

In our further investigation, participants were categorized based on their frequency of smartphone use. Considering that most older adults in this study use their smartphones within 3 hours per day, we divided them into 4 groups according to self-reported frequency of use: 1 hour per day, 2 hours per day, 3 hours per day, and more than 3 hours per day. Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied to compare those 4 groups in terms of the MoCA-B, PHQ-9, GAD-7, and ISI scores.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Data Acquisition

From the total sample of 1014 older adults who completed the questionnaire survey, a subsample of 130 participants was targeted for functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning. In addition to the exclusion criteria mentioned earlier, there were additional exclusion criteria for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) analysis, such as the presence of metal objects in the body and claustrophobia. Among the eligible individuals, a stratified random sampling method was then used to select participants according to their smartphone usage status. If a selected participant declined MRI participation, another eligible individual was randomly selected to replace them. This procedure ultimately yielded a final sample of 130 participants, comprising 89 smartphone users and 41 nonsmartphone users.

Structural and functional MRI data were acquired on a 3-T United Imaging Healthcare scanner (uMR 780) at Three Gorges Uni RenHe Hospital. During the scanning, participants were instructed to remain still, stay awake, and avoid any structured cognitive activity. Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging data were acquired using a T2*-weighted echo-planar imaging sequence sensitive to blood-oxygen-level-dependent contrast [25,26]. Functional data were collected using the following parameters: repetition time=2000 ms, echo time=30 ms, flip angle=80°, matrix=64×64, and field of view=220 mm. A total of 240 volumes were obtained in 8 minutes and each volume consisted of 36 interleaved axial slices (slice thickness of 4 mm; no gap).

MRI Data Analysis

MRI data analysis was performed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (version 12; Functional Imaging Laboratory) [27] and DPABI (Data Processing & Analysis for [Resting-State] Brain Imaging) [28] under MATLAB R2013b. Specifically, the data analysis workflow consisted of the following steps: (1) Quality control: to assess the data quality, we used Magnetic Resonance Imaging Quality Control tool [29], which examined various indicators such as signal-to-noise ratio, head motion, and ghost-to-signal ratio. (2) Preprocessing: the preprocessing steps included converting the data to Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative format, removing the first 10 time points to ensure stability, conducting slice timing correction, realigning the images, segmenting structural images, normalizing the functional data, removing the linear trend of the time series, and regressing out nuisance variables. (3) Smoothing: we smoothed the images with a Gaussian kernel of 4 mm full width. (4) Calculation of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations + fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations. (5) Band pass filtering: a band-pass filter was used to extract signals in the conventional frequency band (0.01‐0.08 Hz). (6) Normalization: we normalized to a symmetric template and calculation of voxel-mirrored homotopic connectivity. (7) Calculation of regional homogeneity and degree centrality (with the correlation threshold set at r>0.25 [30]) using the unsmoothed data. (8) Two-sample t tests: these tests were performed to identify differences between two groups with the AlphaSim correction (voxel-wise threshold of P<.001 and cluster-wise threshold of P<.05). Age, gender, and education were included as covariates.

Results

Demographics and Smartphone Usage

As shown in Table 1, a total of 641 participants use smartphones in their daily lives, and 373 participants never use smartphones. There were no significant differences in age, gender, and the years of education between participants who used the smartphone and participants who never used the smartphone (P>.05). Within older adults who use the smartphone, the vast majority watch short videos on their smartphones (579/641, 90.3%), while the proportions for using social software, games and music, and other are 4.2% (27/641), 1.3% (8/641), and 0.6% (4/641), respectively.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and smartphone usage of all participants.

| USma (n=641) | NUSb (n=373) | 2-tailed t test or chi-squarec (df) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 66.63 (4.18) | 67.06 (4.51) | 1.53 (1012) | .13 |

| Sex, n | 0.08 (1012) | .78 | ||

| Male | 264 | 157 | ||

| Female | 377 | 216 | ||

| Education (years), mean (SD) | 5.05 (3.64) | 5.46 (3.69) | 1.71 (1012) | .09 |

| Frequency of use (hours/day), mean (SD) | 1.81 (1.06) | N/Ad | N/A | N/A |

| SAS-SVe, mean (SD) | 19.63 (3.93) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

USm: use smartphone.

NUS: never use a smartphone.

A chi-square test was used for sex; a t test was used for all other variables.

N/A: not applicable.

SAS-SV: Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version.

Depression, Anxiety, Insomnia, and Physical Pain

As shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences between the smartphone use group and the never-use-smartphone group in depression, anxiety, insomnia, and physical pain (P>.05).

Table 2. Depression, anxiety, insomnia, and physical pain of all participants. Analysis was completed using Mann-Whitney U tests.

| USa (n=641), n (%) | NUSb (n=373), n (%) | z score | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression levelc | 0.689 | .49 | ||

| None | 567 (88.5) | 324 (86.9) | ||

| Mild | 49 (7.6) | 37 (9.9) | ||

| Moderate | 18 (2.8) | 7 (1.9) | ||

| Severe | 7 (1.1) | 5 (1.3) | ||

| Anxiety leveld | 0.934 | .35 | ||

| None | 604 (94.2) | 347 (93) | ||

| Mild | 30 (4.7) | 21 (5.5) | ||

| Severe | 7 (1.1) | 6 (1.5) | ||

| Insomnia levele | 0.340 | .73 | ||

| None | 480 (74.9) | 284 (76.1) | ||

| Mild | 121 (18.9) | 62 (16.6) | ||

| Moderate | 31 (4.8) | 23 (6.2) | ||

| Severe | 9 (1.4) | 4 (1.1) |

USm: use smartphone.

NUS: never use a smartphone.

PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire.

GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

ISI: Insomnia Severity Index.

Cognitive Function

In the smartphone use group, 325 (50.7%) participants added 1 point for ≤4 years of education, and 66 (10.3%) participants added 2 points for nonreaders. In the never-use-smartphone group, 128 (34.3%) participants added 1 point for ≤4 years of education, and 51 (13.7%) participants added 2 points for nonreaders. To overcome the bias of education, 1 point was added for those participants with ≤4 years of education and 2 points for nonreaders (adjusted total scores ≤30). Compared with those who never use the smartphone, people who use the smartphone have a better cognitive function assessed by MoCA-B, which was demonstrated in Table 3 and Figure 2. In addition to the total score (z=3.806, P<.001), people who use the smartphone have higher scores in subdomains of fluency (z=3.025, P=.002), naming (z=2.571, P=.01), abstraction (z=5.311, P<.001), and delayed recall (z=2.277, P=.02). Among those, the scores of total, fluency, and abstraction survived Bonferroni correction (P<.005). Depression, anxiety, insomnia, and cognitive characteristics of MRI participants are presented in Table S1 in Multimedia Appendix 1.

Table 3. Cognitive function of all participants.

| Cognitive function | USma (n=641), mean (SD) | NUSb (n=373), mean (SD) | z score | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive function | 0.26 (0.44) | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.230 | .82 |

| Fluency | 0.90 (0.73) | 0.76 (0.72) | 3.025 | .002 |

| Orientation | 5.26 (0.44) | 5.24 (0.44) | 0.653 | .51 |

| Memory | 2.46 (0.55) | 2.37 (0.63) | 1.767 | .08 |

| Naming | 3.13 (0.44) | 3.05 (0.46) | 2.571 | .01 |

| Attention | 1.66 (1.05) | 1.74 (1.06) | 1.180 | .24 |

| Abstraction | 1.28 (0.97) | 0.94 (0.82) | 5.311 | <.001 |

| Delayed recall | 2.19 (1.06) | 2.25 (0.86) | 2.277 | .02 |

| Visual perception | 1.83 (0.64) | 1.75 (0.69) | 1.953 | .051 |

| Total score | 19.66 (2.54) | 18.98 (2.63) | 3.806 | <.001 |

USm: use smartphone.

NUS: never use a smartphone.

Figure 2. The difference in cognitive scores between the USm group and the NUS group. Scores for each domain were normalized before visualization to enable comparison across domains. USm: use smartphone; NUS: never use smartphone. * P<.005, ** P<.001.

Further Explore the Effects of Smartphone Use Frequency

As demonstrated in Table 4, there were no significant differences in MoCA-B and GAD-7 scores among the 3 groups with different frequencies of smartphone use. However, individuals who used their smartphones for ≥3 hours per day exhibit higher levels of depression (H=8.776, P=.03) and insomnia (H=13.335, P=.004).

Table 4. Clinical and cognitive characteristics of participants with different frequencies of smartphone use. Analysis was completed using Kruskal-Wallis tests.

| MoCA-Ba | Means of ranks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, n | Total score | PHQ-9b | GAD-7c | ISId | |

| Frequency (h/d) | |||||

| <1 | 315 | 19.60 (2.58)e | 313.39 | 317.71 | 303.76 |

| 1‐2 | 165 | 19.79 (2.56)e | 315.36 | 316.06 | 330.05 |

| 2‐3 | 134 | 19.63 (2.34)e | 341.04 | 331.44 | 336.89 |

| >3 | 27 | 19.89 (3.00)e | 344.76 | 337.72 | 388.00 |

| H-value | N/Af | 0.348 | 8.776 | 5.284 | 13.335 |

| P value | N/A | .95 | .03 | .15 | .004 |

MoCA-B: Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic.

PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire.

GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

ISI: Insomnia Severity Index.

Mean (SD).

N/A: not applicable.

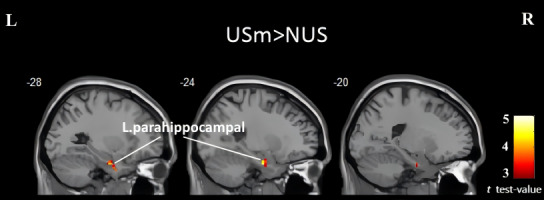

Brain Activity

After excluding low-quality data, a total of 106 participants were included in the subsequent analysis, consisting of 75 smartphone users and 31 nonsmartphone users. No significant differences were observed between the 2 groups in terms of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations, fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations, regional homogeneity, and voxel-mirrored homotopic connectivity. However, in terms of degree centrality, older adults who were smartphone users exhibited higher values in the left parahippocampal gyrus (peak coordinates: x=−24, y=−9, z=−27; cluster size=20; t=4.52). The brain activity results have been presented in Figure 3. However, correlation analysis has not identified a correlation between the left parahippocampal gyrus’ degree centrality values and cognitive scores (Table S2 in Multimedia Appendix 1).

Figure 3. Brain regions showing significantly increased degree centrality in the USm group compared to the NUS group. The cluster in the left parahippocampal gyrus is visualized in sagittal slices at x=–28, –24, and –20 (MNI coordinates). The results were set at a threshold at voxel-wise P<.001 and cluster-level P<.05 (AlphaSim corrected). The color bar indicates t test values. L: left; MNI: Montreal Neurological Institute; NUS: never use smartphone; R: right; USm: use smartphone.

Discussion

Principal Findings

In this study, we have explored the effects of smartphone use on cognitive function and the relationship between smartphone use frequency and cognitive function and mental health among older adults. The main findings of this study were that nonaddictive smartphone use is associated with better cognitive function of older adults compared to those who never use smartphones and does not significantly affect sleep, depression, and anxiety levels but may increase the risk of depression and insomnia with further increases in smartphone use.

Comparison to Prior Work

First, we have investigated smartphone usage among older adults. The results revealed that about 63.2% of older adults use smartphones in their lives, exceeding the internet penetration rate among older adults in 2021 (43.2%) [31] by nearly 20%, indicating the increasing prevalence of smartphones among older adults. Interestingly, we found that the most commonly used function among older adults was watching short videos (90.3%), which was inconsistent with the results of other studies [32,33]. Further inquiry revealed that most of them watched short videos on TikTok, which used to be regarded as the virtual playground of teenagers [34], indicating that older adults today are bridging the digital divide and exploring new technological platforms.

The prevalence of PSU in this study was relatively low (approximately 2.4%), consistent with the findings of Busch et al [35]. This could be attributed to the fact that, compared to younger individuals, older adults tend to concentrate their smartphone usage on a limited range of recreational activities (such as TikTok rather than gaming or others), and their work does not typically require smartphone involvement. Furthermore, during this study, we also found that older adults may experience difficulties maintaining prolonged smartphone usage due to physical discomfort. They reported experiencing pain in the neck and wrist, which prevented them from using smartphones continuously, even if they desired to continue it. This means that physical pain may be an important reason for the low rate of mobile phone addiction in older adults, but at the same time, it suggests that smartphone use may have adverse physical effects on older adults, which needs to be further explored in future investigations.

As regards nonaddictive smartphone use, our study demonstrated that older adults who incorporate smartphones into their daily lives exhibited better cognitive function than those who never use smartphones. Several other similar studies have also reported similar findings, highlighting the positive effects of smartphone use on cognition in older adults [32,36,37]. Using smartphones could be regarded as a mentally stimulating activity. According to the “use it or lose it” hypothesis, more involvement in mentally stimulating activities would bring less age-related cognitive decline [38], and the involved mechanisms may include increasing functional connectivity within related brain networks [39] and promoting neural plasticity [40,41]. Specifically, in our study, older adults who used smartphones displayed better performance in fluency and abstraction. Increased social engagement and reduced feelings of loneliness [42] could improve the verbal fluency of smartphone users. Moreover, older adults venturing into more advanced smartphone features, such as short videos, may experience heightened cognitive load and increased brain activation [43], potentially facilitating the enhancement of advanced cognitive functions, including abstraction.

Among all resting-state MRI indicators, our study discovered that only, in terms of degree centrality, older adults who were smartphone users exhibited higher values in the left parahippocampal gyrus. Degree centrality is an analytical method that evaluates the local properties of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging signals by measuring the extent to which a given brain voxel (node) is directly connected to other voxels [44,45]. The parahippocampal gyrus is known to be involved in various cognitive processes, including scene recognition, episodic memory, spatial navigation, and memory encoding and retrieval [46]. This finding aligns with another outcome obtained in this study, which demonstrates that older adults who use smartphones exhibit better performance in delayed recall. However, this effect was nonsignificant after correction for multiple comparisons. As memory is a crucial component of cognitive function and tends to decline with age, one possible explanation is that smartphone use may stimulate the parahippocampal gyrus and potentially enhance memory in older adults. Furthermore, regarding certain specific brain areas such as the middle frontal gyrus, as well as the lingual gyrus, which were previously found to be possibly associated with smartphone use in prior studies [47,48], this current investigation did not demonstrate clear activation or deactivation. Overall, the neural activation patterns observed in individuals using smartphones in this study were far less significant compared to previous findings. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is the emphasis on nonaddictive usage and a relatively shorter duration of smartphone usage, as repeatedly underscored throughout our research.

This study also found that healthy smartphone usage does not have a significant impact on the sleep quality, depression, and anxiety levels of older adults. As previously mentioned, the detrimental effects of smartphones on sleep and psychological well-being largely stem from unhealthy patterns of use. For example, using smartphones for long periods or at night [49,50] can considerably impair their sleep and increase the risk of depression. However, for older people, possibly because of physical limitations (excessive smartphone use can cause physical discomfort) [51], they rarely show excessive or unhealthy smartphone use and often get satisfaction from it [9,52]. These factors may be important reasons to protect them from the adverse risks of excessive smartphone use.

It is worth mentioning that as cell phone use further increased, it did not seem to continue to improve cognitive performance in older adults, but instead led to higher levels of insomnia and depression. This is consistent with previous research on young adults [49,53], suggesting that long-term use of mobile phones can also adversely affect mental health and sleep quality in older adults.

Limitations

A few limitations of this study also need to be taken into consideration. First, this study is a cross-sectional study and could not prove the causal relationship between smartphone use and cognitive function among older adults. So we plan to conduct follow-up assessments on the participants in this study in the future. Second, although we aimed to investigate all eligible older adults in the village to conduct a census, a small proportion of older adults were unable to participate due to factors such as physical limitations and personal reasons. This may introduce bias to the results to a certain extent. Third, all of the cognitive domains explored in this study fall within the realm of neurocognition, and another important aspect of cognition, namely social cognition [54], has not been assessed. Additionally, we determined the minimum required sample size for this survey through sample size calculation; however, for the MRI component, the sample size was determined based on prior experience, which may result in insufficient statistical power.

Future Directions

Our study could provide a reference for further studies to investigate the underlying mechanisms through which smartphones improve the cognition of older adults and develop interventions that leverage smartphone use to improve cognitive function. Considering that cognition is strongly associated with the function of brain regions [55], future studies could integrate other modal imaging measures, such as task-related functional magnetic resonance imaging, to further explore the potential mechanisms underlying the cognitive benefits observed in older adults who use smartphones.

Conclusions

In sum, this study reveals that older adults who incorporate smartphones into their daily lives demonstrate better cognitive function compared to those who never use smartphones. However, excessive smartphone use is associated with an increased risk of mental health problems instead of improved cognitive function. Based on our findings, we suggest that short periods of daily smartphone use can improve cognitive function in older adults without damaging mental health.

Supplementary material

Information of MRI participants. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871072 and 82071523), Major Program of National Science and Technology Innovation 2030 for “Brain Science and Brain-like Research” (2021ZD0200700), and Open Fund of Yichang City Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders (YCXL-23‐06).

Abbreviations

- DPABI

Data Processing & Analysis for (Resting-State) Brain Imaging

- GAD-7

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale

- ISI

Insomnia Severity Index

- MoCA-B

Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PSU

problematic smartphone use

- SAS-SV

Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: ZW, GW, and QW conceptualized this study. ZW and XQ handled the methodology, data curation, writing of the original draft, and formal analysis. XQ and QW validated and reviewed and edited the writing. ZW, XQ, and FO worked on the investigation. GW, BX, and HL collected and managed the resources. XQ visualized this study. GW and QW supervised and administered this project. GW acquired the funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this paper.

Data Availability: The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.United Nations; 2022. [20-06-2025]. World Population Prospects 2022: summary of results.https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf URL. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson TD. Ageism: prejudice against our feared future self. [04-07-2025];J Soc Issues. 2005 Jun;61(2):207–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00402.x. https://spssi.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/15404560/61/2 URL. Accessed. doi. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng Q, Fong JH, Zhang W, Liu C, Chen H. Leisure activity engagement among the oldest old in China, 1998-2018. Am J Public Health. 2020 Oct;110(10):1535–1537. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305798. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mander BA, Winer JR, Walker MP. Sleep and human aging. Neuron. 2017 Apr 5;94(1):19–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.004. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavelin HM, Dong C, Minkov R, et al. Combined physical and cognitive training for older adults with and without cognitive impairment: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ageing Res Rev. 2021 Mar;66(101232):101232. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101232. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dzierzewski JM, Dautovich N, Ravyts S. Sleep and cognition in older adults. Sleep Med Clin. 2018 Mar;13(1):93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2017.09.009. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guarnera J, Yuen E, Macpherson H. The impact of loneliness and social isolation on cognitive aging: a narrative review. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2023;7(1):699–714. doi: 10.3233/ADR-230011. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kok RM, Reynolds CF., III Management of depression in older adults: a review. JAMA. 2017 May 23;317(20):2114–2122. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5706. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertocchi FM, De Oliveira AC, Lucchetti G, Lucchetti ALG. Smartphone use, digital addiction and physical and mental health in community-dwelling older adults: a population-based survey. J Med Syst. 2022 Jun 18;46(8):53. doi: 10.1007/s10916-022-01839-7. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brautsch LA, Lund L, Andersen MM, Jennum PJ, Folker AP, Andersen S. Digital media use and sleep in late adolescence and young adulthood: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2023 Apr;68:101742. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101742. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaya F, Bostanci Daştan N, Durar E. Smart phone usage, sleep quality and depression in university students. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021 Aug;67(5):407–414. doi: 10.1177/0020764020960207. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karakose T, Yıldırım B, Tülübaş T, Kardas A. A comprehensive review on emerging trends in the dynamic evolution of digital addiction and depression. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1126815. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1126815. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elhai JD, Levine JC, Hall BJ. The relationship between anxiety symptom severity and problematic smartphone use: a review of the literature and conceptual frameworks. J Anxiety Disord. 2019 Mar;62:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.11.005. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fineberg NA, Menchón JM, Hall N, et al. Advances in problematic usage of the internet research - a narrative review by experts from the European network for problematic usage of the internet. Compr Psychiatry. 2022 Oct;118:152346. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152346. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arikan G, Acar IH, Ustundag-Budak AM. A two-generation study: the transmission of attachment and young adults’ depression, anxiety, and social media addiction. Addict Behav. 2022 Jan;124:107109. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107109. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee D, Namkoong K, Lee J, Lee BO, Jung YC. Lateral orbitofrontal gray matter abnormalities in subjects with problematic smartphone use. J Behav Addict. 2019 Sep 1;8(3):404–411. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.50. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pyeon A, Choi J, Cho H, et al. Altered connectivity in the right inferior frontal gyrus associated with self-control in adolescents exhibiting problematic smartphone use: a fMRI study. J Behav Addict. 2021 Dec 23;10(4):1048–1060. doi: 10.1556/2006.2021.00085. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006 May 22;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001 Jul;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun J, Liang K, Chi X, Chen S. Psychometric properties of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 Item (GAD-7) in a large sample of Chinese adolescents. Healthcare (Basel) 2021 Dec 9;9(12):1709. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9121709. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fabbri M, Beracci A, Martoni M, Meneo D, Tonetti L, Natale V. Measuring subjective sleep quality: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jan 26;18(3):1082. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031082. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon M, Kim DJ, Cho H, Yang S. The smartphone addiction scale: development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083558. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Julayanont P, Tangwongchai S, Hemrungrojn S, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic: a screening tool for mild cognitive impairment in illiterate and low-educated elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Dec;63(12):2550–2554. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13820. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa S, Lee TM, Nayak AS, Glynn P. Oxygenation-sensitive contrast in magnetic resonance image of rodent brain at high magnetic fields. Magn Reson Med. 1990 Apr;14(1):68–78. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140108. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995 Oct;34(4):537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Statistical parametric mapping. Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging. [20-06-2025]. http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm URL. Accessed.

- 28.Yan CG, Wang XD, Zuo XN, Zang YF. DPABI: Data Processing & Analysis for (Resting-State) Brain Imaging. Neuroinformatics. 2016 Jul;14(3):339–351. doi: 10.1007/s12021-016-9299-4. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esteban O, Birman D, Schaer M, Koyejo OO, Poldrack RA, Gorgolewski KJ. MRIQC: advancing the automatic prediction of image quality in MRI from unseen sites. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184661. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi Y, Zeng Y, Wu L, et al. A study of the brain functional network of post-stroke depression in three different lesion locations. Sci Rep. 2017 Nov 1;7(1):14795. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14675-4. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CNNIC; 2022. [20-06-2025]. China statistical report on internet development (no.49) [Report in Chinese]https://www.cnnic.net.cn/NMediaFile/2023/0807/MAIN1691372884990HDTP1QOST8.pdf URL. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan M, Chen J, Zhou Z, et al. Joint associations of smartphone use and gender on multidimensional cognitive health among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2019 May 24;19(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1151-x. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen K, Chan AHS, Tsang SNH. Usage of mobile phones amongst elderly people in Hong Kong. Proceedings of the International MultiConference of Engineers and Computer Scientists 2013; Mar 13-15, 2013; Hong Kong. [04-07-2025]. Presented at. URL. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bresnick E. Intensified play: cinematic study of TikTok mobile app. ResearchGate. 2019. [20-06-2025]. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ethan-Kurzrock/publication/335570557_Intensified_Play_Cinematic_study_of_TikTok_mobile_app/links/5dd3443d299bf1b74b4e2832/Intensified-Play-Cinematic-study-of-TikTok-mobile-app.pdf URL. Accessed.

- 35.Busch PA, Hausvik GI, Ropstad OK, Pettersen D. Smartphone usage among older adults. [04-07-2025];Comput Human Behav. 2021 Aug;121:106783. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106783. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563221001060 URL. Accessed. doi. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin CB, Hong B, Newsome RN, et al. A smartphone intervention that enhances real-world memory and promotes differentiation of hippocampal activity in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Dec 20;119(51):e2214285119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2214285119. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson SA, Byrne P, Rodgers SE, Maden M. A systematic review of smartphone and tablet use by older adults with and without cognitive impairment. Innov Aging. 2022;6(2):igac002. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igac002. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salthouse TA. Mental exercise and mental aging: evaluating the validity of the “use it or lose it” hypothesis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2006 Mar;1(1):68–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00005.x. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Balkom TD, van den Heuvel OA, Berendse HW, van der Werf YD, Vriend C. The effects of cognitive training on brain network activity and connectivity in aging and neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2020 Jun;30(2):267–286. doi: 10.1007/s11065-020-09440-w. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen L, Murphy K, Andrews G. Cognitive and neural plasticity in old age: a systematic review of evidence from executive functions cognitive training. Ageing Res Rev. 2019 Aug;53:100912. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100912. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park DC, Bischof GN. The aging mind: neuroplasticity in response to cognitive training. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013 Mar;15(1):109–119. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.1/dpark. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bodner E, Ayalon L, Avidor S, Palgi Y. Accelerated increase and relative decrease in subjective age and changes in attitudes toward own aging over a 4-year period: results from the health and retirement study. Eur J Ageing. 2017 Mar;14(1):17–27. doi: 10.1007/s10433-016-0383-2. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Small GW, Moody TD, Siddarth P, Bookheimer SY. Your brain on Google: patterns of cerebral activation during internet searching. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009 Feb;17(2):116–126. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181953a02. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buckner RL, Sepulcre J, Talukdar T, et al. Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2009 Feb 11;29(6):1860–1873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5062-08.2009. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuo XN, Ehmke R, Mennes M, et al. Network centrality in the human functional connectome. Cereb Cortex. 2012 Aug;22(8):1862–1875. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr269. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aminoff EM, Kveraga K, Bar M. The role of the parahippocampal cortex in cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013 Aug;17(8):379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.009. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi J, Cho H, Choi JS, Choi IY, Chun JW, Kim DJ. The neural basis underlying impaired attentional control in problematic smartphone users. Transl Psychiatry. 2021 Feb 18;11(1):129. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01246-5. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nasser NS, Sharifat H, Rashid AA, et al. Cue-reactivity among young adults with problematic instagram use in response to instagram-themed risky behavior cues: a pilot fMRI study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:556060. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.556060. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wacks Y, Weinstein AM. Excessive smartphone use is associated with health problems in adolescents and young adults. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:669042. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.669042. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Exelmans L, Van den Bulck J. Bedtime mobile phone use and sleep in adults. Soc Sci Med. 2016 Jan;148(93-101):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.037. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eitivipart AC, Viriyarojanakul S, Redhead L. Musculoskeletal disorder and pain associated with smartphone use: a systematic review of biomechanical evidence. Hong Kong Physiother J. 2018 Dec;38(2):77–90. doi: 10.1142/S1013702518300010. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim SH, Kim YH, Lee CH, Lee Y. Smartphone usage and overdependence risk among middle-aged and older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2024 Feb 9;24(1):413. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17873-8. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rathakrishnan B, Bikar Singh SS, Kamaluddin MR, et al. Smartphone addiction and sleep quality on academic performance of university students: an exploratory research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Aug 5;18(16):8291. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168291. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vita A, Gaebel W, Mucci A, et al. European Psychiatric Association guidance on assessment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2022 Sep 5;65(1):e58. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.2316. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McDonough IM, Nolin SA, Visscher KM. 25 years of neurocognitive aging theories: what have we learned? Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:1002096. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.1002096. doi. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Information of MRI participants. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.