Abstract

Precision medicine has become a cornerstone in modern therapeutic strategies, with nucleic acid aptamers emerging as pivotal tools due to their unique properties. These oligonucleotide fragments, selected through the Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment process, exhibit high affinity and specificity toward their targets, such as DNA, RNA, proteins, and other biomolecules. Nucleic acid aptamers offer significant advantages over traditional therapeutic agents, including superior biological stability, minimal immunogenicity, and the capacity for universal chemical modifications that enhance their in vivo performance and targeting precision. In the realm of osseous tissue repair and regeneration, a complex physiological process essential for maintaining skeletal integrity, aptamers have shown remarkable potential in influencing molecular pathways crucial for bone regeneration, promoting osteogenic differentiation and supporting osteoblast survival. By engineering aptamers to regulate inflammatory responses and facilitate the proliferation and differentiation of fibroblasts, these oligonucleotides can be integrated into advanced drug delivery systems, significantly improving bone repair efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Aptamer-mediated strategies, including the use of siRNA and miRNA mimics or inhibitors, have shown efficacy in enhancing bone mass and microstructure. These approaches hold transformative potential for treating a range of orthopedic conditions like osteoporosis, osteosarcoma, and osteoarthritis. This review synthesizes the molecular mechanisms and biological roles of aptamers in orthopedic diseases, emphasizing their potential to drive innovative and effective therapeutic interventions.

Subject terms: Bone, Bone cancer

Introduction

In the pursuit of novel and efficacious therapeutic strategies for disease treatment, scientific researchers are continuously striving for innovation. In recent years, precision medicine has emerged as a pivotal approach in the management of numerous diseases. Notably, nucleic acid aptamer, a closely associated technology, has attracted widespread attention. These aptamers are oligonucleotide fragments derived from the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) technology, characterized by their high affinity and specificity towards target molecules.1,2 They can be either DNA or RNA sequences, with some studies also exploring nucleic acid analogs and peptides. Aptamers possess notable advantages, including considerable biological stability, potential for universal chemical modification, low immunogenicity, and rapid tissue penetration.3 In recent years, significant advancements have been achieved in targeted gene therapy research. Current research focuses on delivering therapeutic genes to target cells via specific antibodies or ligands, along with the use of disease-specific gene promoters to tightly regulate gene expression within the disease microenvironment.3,4 Although viral vectors demonstrate high efficacy in gene delivery, concerns regarding their safety, immunogenicity, and manufacturing complexities restrict their advancement in clinical applications. In contrast, nonviral gene delivery systems exhibit considerable potential owing to their reduced immunogenicity and simpler manufacturing processes.5 Nonviral systems possess a longer shelf-life, lower production costs, and reduced batch-to-batch variability. Moreover, their physicochemical properties and target specificity can be tailored by modifying the nucleic acid composition. They are readily amenable to chemical synthesis and modification to enhance enzyme resistance and in vivo pharmacokinetics.6 The incorporation of aptamers into nonviral vectors or their combination with other nonviral vectors can improve the targeting, cellular uptake efficiency, and endosomal escape capability of nucleic acid therapeutics. For example, aptamers can be modified or conjugated with other materials to facilitate improved loading and protection of nucleic acid drugs, thereby enabling more precise delivery to specific cells or tissue sites and achieving enhanced therapeutic efficacy.6–8 This review aims to summarize and elucidate the molecular mechanisms and biological roles of nucleic acid aptamers in orthopedic diseases, proposing innovative and effective strategies for future medical interventions.

The research history and advantages of nucleic acid aptamers

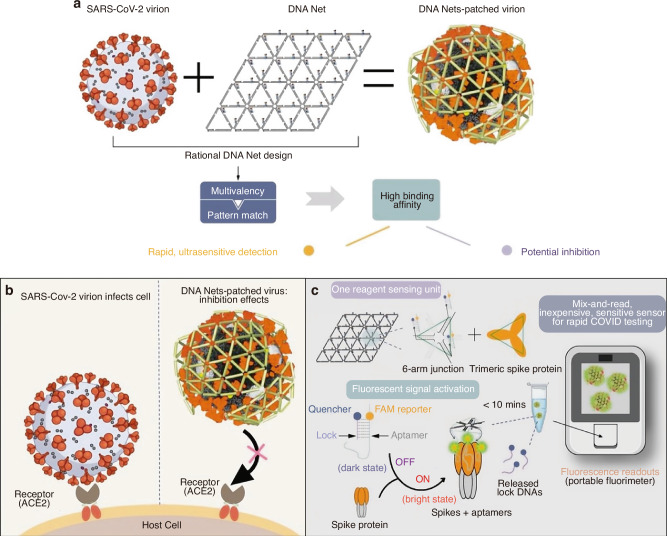

The development of SELEX technology in 1990 marked the emergence of nucleic acid aptamers.2,9 Subsequent discoveries included RNA aptamers with catalytic activity in vitro and microRNAs (miRNAs).10–13 From the mid-1990s to the early 21st century, research primarily focused on developing aptamers for small molecule sensing applications.14–16 A significant advancement occurred in 2001 with the development of aptamer-based protein labeling and detection techniques.17,18 The introduction of Cell-SELEX in 2003 was followed by the successful development of the first aptamer-based drug.19–21 Further innovations emerged in 2006 with non-covalently coupled aptamer-DOX conjugates and the establishment of aptamer-based optical and electrochemical sensing platforms during the mid-2000s.15,16,22 The concept of liquid biopsy gained prominence around 2010, leading to preliminary research on circulating tumor cell release and separation methods using nucleic acid aptamers.23–25 Investigations into miRNA detection methods utilizing aptamers commenced in 2015.26 During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, researchers successfully isolated DNA aptamers targeting the viral spike protein.27–31 Recent advancements have focused on developing aptamer-drug conjugates for cancer therapy and diagnostic methods for periprosthetic joint infection (PJI).32–35

Nucleic acid aptamers demonstrate enhanced stability through their secondary structures, including stem-loops, hairpins, and G-quadruplexes, with base modifications and stable phosphate backbones contributing significantly to their structural integrity.36–38 Protein binding further protects aptamers from external influences.39 Environmental factors, particularly ion concentration and pH levels, significantly influence aptamer stability.9 Technological advancements have introduced nucleotide analogs to enhance binding affinity and nanotechnology applications for co-delivery with therapeutic molecules.7,40–43 Chemical modifications prevent enzymatic degradation and alter binding properties. Optimization of connection modes, length, and density is essential for developing functional aptamer conjugates.38,42–48 Multivalent aptamers improve detection sensitivity, while pre-structured DNA libraries expand screening diversity.7,49–51 The formation of aptamer-drug complexes through therapeutic agent conjugation improves drug targeting and efficacy.52–56 Advanced technologies, including microfluidic technology and high-throughput sequencing, have optimized separation efficiency and the SELEX process.57–59

The three-dimensional (3D) conformation of an aptamer, derived from its secondary structure, is pivotal in determining its binding affinity and specificity to homologous targets.60 This structural diversity endows aptamers with the remarkable ability to recognize a wide array of target molecules, including proteins, RNA, DNA, and small molecules, with exceptional specificity and affinity.60–62 The functionality of aptamer-target complexes is underpinned by a network of intramolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals forces, and complementary base pairing.62 These interactions synergistically facilitate the precise recognition and binding of aptamers to their targets.63,64 SELEX, a widely utilized method for aptamer screening, has found extensive applications, particularly in the biomedical domain, where it is instrumental in selecting aptamers against proteins, tumor markers, and other biomolecules (Fig. 1a). The aptamers are invaluable in diagnostics, therapeutics, and research due to their high affinity and specificity. Furthermore, SELEX can be refined through various iterations, such as Cell-SELEX (Fig. 1b) and in vivo SELEX, which are tailored for the selection of aptamers in a cell-specific context and within living organisms, respectively.65,66 The counter-SELEX strategy introduces a negative selection step to exclude aptamers that bind to non-target molecules, thereby enhancing specificity by distinguishing between highly similar structures.66,67 Beyond SELEX, other methodologies can also be employed to augment the specificity and affinity of aptamers. Competitive binding assays, for instance, allow for the assessment of the binding affinity between an aptamer and its target, enabling the optimization of experimental conditions to improve aptamer performance.68,69 This approach is particularly useful in selecting aptamers that can effectively compete for target binding sites, thereby enhancing their efficacy in practical applications. In recent years, advancements in separation techniques, such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), capillary electrophoresis, solid-phase, and chip-based microfluidic methods, have emerged to refine the affinity and specificity of candidate aptamers.70,71 The field of aptamer screening has witnessed the advent of innovative techniques aimed at overcoming the limitations of traditional methods. Particle display technology transforms solution-phase aptamers into aptamer particles, enabling quantitative screening based on affinity through FACS. It effectively separates high-affinity aptamers in fewer selection rounds, minimizing selection bias and human error.72,73 Multiparameter particle display further refines this process by employing dual-color FACS to simultaneously evaluate affinity and specificity, facilitating the identification of high-performance aptamers even in complex environments like serum, thus mitigating the risk of discarding potentially valuable aptamers.73,74 Click chemistry particle display integrates click chemistry with particle display, simplifying the generation and high-throughput screening of “non-natural” aptamers with extensive base modifications. This innovation addresses the chemical diversity limitations of natural nucleic acid aptamers, opening new avenues for aptamer selection against challenging targets.73,75 Collectively, these advancements have significantly propelled the development and application of aptamer technology.

Fig. 1.

The SELEX process diagram. a Schematic representation of SELEX process. b Schematic representation of cell-SELEX process

The applications of nucleic acid aptamers in bone-related diseases

Bone repair and healing constitute a complex and highly coordinated physiological process aimed at restoring or maintaining osseous function.76 The biological importance of this process encompasses several aspects. Primarily, bones provide structural support and protection for internal organs, making bone repair essential for maintaining anatomical integrity. Investigation of the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in this process enhances understanding of general tissue repair and regeneration processes.76 With global population aging, the escalating risk of osteoporosis-related fractures underscores the significance of optimizing bone healing to improve geriatric quality of life. Current treatments frequently struggle to completely restore pre-fracture biomechanical properties, particularly in complex open fractures or elderly patients.77 Factors such as chronic inflammation, diabetes, vitamin deficiency, aging, and polytrauma can impede healing progression.78 Although various technologies and pharmacological agents have been developed to facilitate bone repair and healing, clinical validation remains insufficient for many applications.79 Moreover, bone grafting and substitute materials face challenges such as immunogenicity, infection risks, and donor source limitations.80

Aptamers exert crucial regulatory effects on bone repair through modulation of key molecular pathways, including parathyroid hormone (PTH), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.81–83 PTH promotes osteogenic differentiation by reducing osteoblast apoptosis and increasing the number of osteoblasts.84 Under specific conditions, PTH activates bone lining cell transformation into active osteoblasts.85–89 Besides, PTH expands osteoprogenitor cell reservoirs in bone marrow and direct early osteoblast lineage cells away from the adipocyte lineage, thereby promoting their differentiation into osteoblasts.90,91 On the other hand, PTH stimulates osteoclastogenesis through non-cell-autonomous mechanisms, enhancing bone resorption to liberate growth factors from the bone matrix that subsequently promote osteoblast migration, differentiation, and functional activation.92,93 BMPs synergize with angiogenic factors (eg, VEGF) and metallic cofactors to induce mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) osteoblastic differentiation while coordinating osteogenesis and angiogenesis during repair.94–102

The Wnt signaling pathway can determine the differentiation of mesenchymal precursor cells into osteoblasts or chondrocytes, with β-catenin serving as a vital molecular switch.103–105 Concurrently, the expression of key components within the Wnt signaling pathway is regulated during osteoblast differentiation, influencing cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and functional maturation.81 Furthermore, the Wnt signaling pathway promotes the differentiation of osteoblasts by inhibiting adipogenic transcription factors CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ).106,107 Osteoprotegerin (OPG), a soluble decoy receptor, competitively inhibits receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL)–RANK interaction by binding RANKL trimers, thereby blocking osteoclast differentiation and inducing apoptosis.108 RANKL, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily member upregulated in postmenopausal women, can be primarily modulated by estrogen supplementation.109 It stimulates osteoclastogenesis while suppressing osteoclast apoptosis. OPG competes with RANK for binding to RANKL, thus preventing the generation and maturation of osteoclasts induced by RANKL.110 Therefore, the OPG/RANKL ratio is intimately associated with osteoclastogenesis, ultimately influencing bone mineral density and mechanical strength. In β-catenin-deficient osteoblasts, RANKL expression is upregulated and OPG expression is downregulated, whereas adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc)-deficient osteoblasts demonstrate inverse regulation.111,112 This regulatory network enables Wnt signaling to indirectly govern osteoclast differentiation through osteoblast-mediated mechanisms, thus coordinating bone resorption during repair processes.113

Fracture

Fractures refer to pathological conditions characterized by the disruption of bone continuity or integrity due to external forces. These injuries can occur in any bone. The etiology of fractures is multifactorial, including direct or indirect external forces, chronic repetitive stress, and osteoporosis secondary to diseases or medications. Clinically, the healing process of fractures is typically divided into three stages: hematoma formation, callus formation, and callus remodeling. The injury results in the bone breaking into two or more fragments, accompanied by damage to the surrounding periosteum, blood vessels, and other tissues. Extravasation from bone marrow and vasculature leads to the formation of a localized hematoma containing bone-derived and immune cells.114 Immediately following a fracture, the inflammatory response is activated, serving as a critical initiator of the bone healing process. The inflammatory period is a crucial stage characterized by hypoxia, impaired perfusion, and the migration of various growth factors.115 The fracture hematoma is essential for effective bone regeneration due to its high osteogenic potential.116,117 This characteristic was initially observed in non-specialized bone progenitor cells, now identified as MSCs.118,119 MSCs are multipotent stem cells that can be isolated from many sources in both animals and humans, such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, amniotic fluid, and periosteum. Bone marrow contains the highest abundance of these cells, which are collectively termed bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells (BMSCs).120,121 These cells possess the potential for osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic differentiation.122 Aptamer-loaded delivery systems can stimulate the osteogenic differentiation of these stem cells, thereby promoting the repair and regeneration of bone tissue.123 The fracture hematoma also contains platelets, macrophages, and other cell types.124 Cytokines triggering coagulation within the hematoma simultaneously activate local phagocytic cells, facilitating debris clearance at the fracture site.125 Successful fracture healing demands coordinated interactions between macrophages and BMSCs. During the process of bone repair, the polarization of macrophages plays a key role in regulating the differentiation of BMSCs. M1 macrophages predominantly mediate pro-inflammatory responses, while M2 macrophages promote tissue repair by enhancing BMSC osteogenesis.126 Meanwhile, M2 macrophages are increasingly recognized as positive regulatory factors for fracture healing.127 Macrophages facilitate fracture healing primarily through paracrine mechanisms mediated by exosomes.128,129 Exosomes derived from M2 macrophages (M2-Exos) serve as key paracrine effectors, driving BMSC osteogenic differentiation.128,130,131 Nevertheless, current therapeutic applications of exosomes are limited by nonspecific delivery and rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system.132–134 Shou et al.132 utilized interleukin (IL)-4 to induce the differentiation of the murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 into M2 macrophages, isolated exosomes (M2-Exos) from osteoblasts, and characterized these exosomes using transmission electron microscopy, nanoparticle tracking analysis, and Western blot. After identifying a BMSC-specific aptamer sequence validated by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy, they engineered 3WJ RNA nanoparticles with three functional components: a3wj-Cholesterol, b3wj-BMSC aptamer, and c3wj-Alexa 647 (Table 1). Chain a was conjugated with cholesterol for anchoring to the exosome membrane, chain b was coupled with the BMSC aptamer serving as a targeting ligand, and chain c was labeled with Alexa 647 for imaging purposes. Chains were mixed at a 1:1:1 molar ratio and self-assembled via gradual cooling from 95 °C to 4 °C at 0.1 °C/s. The resulting 3WJ-BMSCapt/M2-Exos system combines BMSC-targeting aptamers with M2-Exos through 3WJ RNA nanoparticles. This functionalized exosome platform demonstrated precise BMSC targeting in vitro and significant fracture site accumulation in vivo, accelerating bone regeneration in a murine femoral fracture model (Fig. 2a). This cell-free strategy offers a novel therapeutic approach, with potential applications in clinically targeted drug delivery. The acute inflammatory response peaks within 24 h and resolves by day 7.135 Concurrently, the hematoma transitions to granulation tissue by about day 7.114 As inflammation subsides, the repair phase initiates with the formation of granulation tissue.124 With the emergence of MSCs and their differentiation into fibroblasts, the hematoma tissue gradually organizes and forms fibrous tissue,136,137 known as fibrous callus, which initially bridges the fracture ends.

Table 1.

Summary of the application of relevant aptamers in orthopedic diseases

| Aptamer | Material/Drug | Molecular target | Function | Diseases/Therapeutic effect | Research progress | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3WJ-BMSCapt/M2-Exos a3wj-Cholesterol b3wj-BMSCaptamer c3wj-Alexa 647 |

Drug | BMSC | Modification of M2-Exos enhances their targeting to BMSCs | In vitro, targeting BMSCs more effectively enhances their proliferation, migration, and osteogenic differentiationIn vivo, it stimulates callus formation, increases bone volume/total volume (BV/TV), bone mineral density (BMD), and trabecular number (Tb. N), reduces trabecular separation (Tb. Sp), promotes new bone formation, and elevates the expression of osteogenic markers ALP and OCN | Under development | 132 |

|

Apt Apt01 Apt02 |

Material | VEGF receptor | They exhibit high affinity for VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 | Simulating the function of VEGF-A, it has the potential to activate VEGR receptors and promote angiogenesis | Under development | 159 |

| Aptamer-agomiR-195 | Drug | Endothelial cell | It specifically targets endothelial cells and increases miR-195 levels in cells | Increasing the number of CD31hiEmcnhi vessels in aged murines stimulates bone formation and improves bone strength | Under development | 297 |

| aptamer-antagomiR-188 | Drug | BMSC | It regulates the expression of miR-188 in BMSCs | Reduce miR-188 levels in BMSCs to increase trabecular volume, quantity, and cortical bone thickness; decrease trabecular separation and intimal circumference; enhance bone strength; elevate the bone formation rate; reduce the number and area of adipocytes in the bone marrow; and increase the number and surface area of osteoblasts on the trabecular and intimal bone surfaces, thereby preventing bone loss and fat accumulation in the bone marrow of elderly murines | Under development | 298 |

| OS-7.9 | Material | MG-63 | It shows high affinity and specific binding to MG-63 cells, as well as recognition of lung and colon colorectal adenocarcinoma cell lines | It enables early diagnosis and targeted treatment of osteosarcoma and metastatic disease | Under development | 317 |

| SL1067 | Material | IL-1α | It demonstrates high affinity and specific recognition of IL-1α | Inhibit the IL-1α signaling pathway to treat related inflammatory reactions and diseases | Under development | 272 |

| VR11 | Material | TNFα | It exhibits high affinity binding and specific recognition of TNFα, inhibiting its receptor binding and blocking TNFα-induced cytotoxicity and NO production | Treat inflammatory diseases and avoid immune reactions | Under development | 273 |

| 8A-35 | Drug | IL-8 | It shows high affinity binding to IL-8, inhibiting IL-8 receptor binding, regulating the IL-8-induced intracellular signaling pathway, and inhibiting neutrophil migration | Potential anti-cancer effects in treating inflammatory diseases | Under development | 274 |

|

Apc001PE aptscl56 |

Drug | The loop3 region of sclerostin | It inhibits the antagonistic effect of sclerostin on Wnt signaling pathway and osteogenic potential | It promotes bone formation without increasing cardiovascular risk | Under development | 507 |

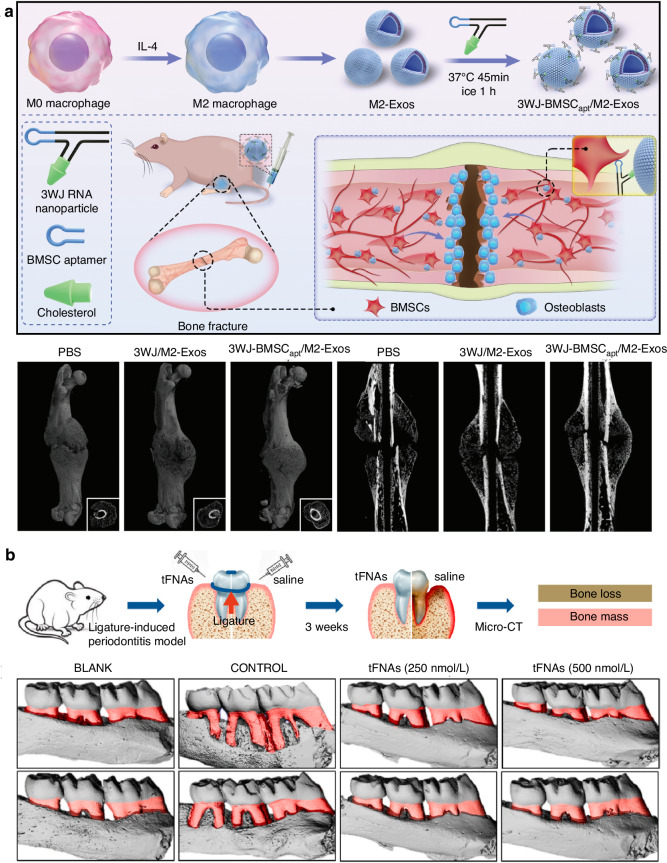

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of bone repair based on nucleic acid aptamer intervention. a Overview of 3WJ-BMSCapt/M2-Exos in fracture model. Representative 3D reconstruction images, 2D cross-sectional and sagittal images from micro-CT scanning of the murine femur fracture model. PBS: phosphate buffered saline. Reproduced form ref. 132 with permission from Oxford University Press, copyright 2023. b tFNAs significantly protected the alveolar bone from periodontitis in vivo. Schematic representation of the rat periodontitis experiment. The micro-CT 3D reconstruction images of the left maxillary alveolar bone. The red area indicates the exposure of the root. Reproduced form ref. 190 with permission from KeAi Communications Co, copyright 2020

The primary hematoma undergoes reorganization into granulation tissue, thereby initiating endochondral ossification. This process generates a cartilaginous callus in the endosteum, intramedullary region, and periosteum. Subsequently, the cartilaginous callus is replaced by a hard callus.138 Endochondral ossification occurs both between fracture ends and externally in the periosteal region. Proliferating osteoblasts produce ossified tissue, forming new bones. These zones remain mechanically unstable until cartilaginous tissue forms a soft callus that stabilizes the fracture structure.139 Intramembranous ossification beneath the periosteum generates new bone adjacent to the fracture ends, contributing to hard callus formation. The bridging of this central hard callus ultimately provides a semi-rigid structure capable of weight-bearing.140 The osteoblast-specific aptamer CH6, identified via Cell-SELEX screening, enables the preparation of functionalized lipid nanoparticles encapsulating osteoblast-targeted Plekho1 siRNA (CH6-LNPs-siRNA). Targeted delivery of this siRNA to bone formation surfaces enhances osteogenesis.67,141–143 CH6 exhibits high-affinity binding to osteoblasts with minimal interaction with rat osteoclasts, human osteoclasts, or hepatocytes. CH6-LNPs-siRNA possesses excellent in vitro osteoblast selectivity, promoting siRNA uptake while significantly reducing liver/kidney accumulation compared to conventional vectors.67 This system achieves osteoblast-specific siRNA delivery, minimizing the uptake of siRNA by liver cells, Kupffer cells, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells.67,144–148 As markers of osteoblast activity, alkaline phosphatase (Alp) and osteocalcin (OCN) are closely associated with bone formation.146,147 CH6-LNPs-siRNA shows enhanced gene silencing efficiency in Alp+/OCN+ cells, with Plekho1 mRNA reduction exhibiting dose-dependent and sustained effects that facilitate bone formation.67 During callus maturation, hypertrophic chondrocytes undergo extracellular matrix calcification, synergized by macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), RANKL, OPG, and TNF-α. These factors mediate mineralized cartilage resorption, osteocyte/osteoclast recruitment, and woven bone formation.149,150 TNF-α additionally promotes MSC recruitment and initiates chondrocyte apoptosis.150 Aptamer-based delivery systems can regulate osteoclast activity by targeting specific molecules, achieving balanced bone metabolism. This system can simultaneously promote BMSC-mediated bone formation and inhibit osteoclast-mediated resorption. This approach effectively counteracts post-traumatic bone loss such as osteoporosis while improving trabecular microstructure and mechanical properties.151

Although hard callus provides biomechanical stability, complete restoration requires remodeling into lamellar bone with a central medullary cavity.150 This remodeling phase involves marrow space reconstruction, hematopoietic tissue regeneration, vascular bed normalization, and blood flow restoration to pre-injury levels.152,153 The hard callus is progressively remodeled; periosteal and endosteal calluses are absorbed, and the medullary cavity is restored.150 As discussed, aptamers targeting osteoblast differentiation factors could accelerate callus formation, while those suppressing osteoclast activity may protect bone integrity. Successful remodeling depends critically on adequate vascular supply and progressive mechanical loading.154–156 These principles are extensively validated in fracture studies. VEGF, a hypoxia-inducible angiogenic regulator, plays pivotal roles in vascular development, angiogenesis and fracture healing.157,158 Among these, VEGF-A is an essential molecule that activates and binds to VEGF receptor-1 (VEGFR-1) and VEGFR-2. Due to the limitations of recombinant VEGF-A, including low stability, significant batch-to-batch variations, and high production costs, Apt01 and Apt02 (Table 1) have been successfully isolated via SELEX. These aptamers exhibit a high affinity for VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, with dissociation rate constants comparable to those of VEGF-A. Notably, their binding affinity hierarchy (VEGFR-1>VEGFR-2) mirrors that of VEGF-A, suggesting DNA aptamers may functionally substitute for VEGF-A.159 In summary, aptamer-mediated precision regulation of bone repair processes represents a novel therapeutic paradigm. By orchestrating tissue regeneration pathways, this approach could advance targeted treatments for orthopedic pathologies.

Alveolar bone

Alveolar bone is the protrusion located on the lower border of the maxilla and the upper border of the mandible, surrounding the root of the tooth. Through the periodontal ligament, it is closely connected to the tooth root and plays a critical role in tooth development, eruption, and mastication processes.160 Under pathological conditions including oral inflammatory diseases, trauma, tumors, hereditary diseases, and systemic diseases, the balance between alveolar bone resorption and formation is disrupted, resulting in alveolar bone defects. These defects can cause tooth loosening and loss, trigger masticatory dysfunction, and endanger the physical and mental health of patients.161 In dental implant therapy, alveolar bone resorption following tooth extraction or defect leads to insufficient bone volume and altered alveolar ridge dimensions, thereby affecting dental implant placement and complicating treatment.162,163 Furthermore, alveolar bone defects can also impact facial appearance, masticatory function, nutrient intake, and cause counterclockwise rotation of the mandible.164–166

In the process of alveolar bone repair and reconstruction, signaling pathways including Notch, Wnt, Toll-like receptor, and NF-κB regulate vital activities such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and autophagy of osteoclasts, osteoblasts, osteocytes, periodontal ligament cells, macrophages, and adaptive immune cells. These pathways also modulate the expression of inflammatory mediators and influence the balance of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system, thereby participating in the repair and reconstruction of alveolar bone.167–176 The Notch signaling pathway functions through a complex network of pro-inflammatory cytokines and bone resorption regulators. Notably, Notch1 signaling promotes alveolar bone repair, whereas Notch2 signaling inhibits it.177,178 Notch2 upregulation coincides with increased IL-1β and IL-6 levels, creating an osteoclast-favorable environment.168 In periapical periodontitis lesions where RANKL expression exceeds OPG, Notch2, Jagged1, Hey1, and TNF-α are overexpressed and strongly correlated, collectively driving extensive alveolar bone resorption.169

In a murine periapical periodontitis model, systemic administration of the Wnt inhibitor IWR-1 via the caudal vein significantly exacerbates alveolar bone lesions. Conversely, lithium chloride (a Wnt activator) applied for root canal sealing enhances collagen type I α1 and Runx2 expression, increases CD45R-positive cells, and accelerates alveolar bone healing via bone formation and immune responses.170 Furthermore, estrogen activates the Wnt signaling pathway through estrogen receptors, stimulating osteoblast differentiation, inhibiting RANKL-induced osteoclast activity, promoting osteocyte autophagy, and preventing apoptosis, directly contributing to alveolar bone reconstruction. Additionally, estrogen indirectly regulates the metabolic homeostasis of alveolar bone by suppressing oxidative stress and inflammatory responses.171,172 TNF-α stimulates gingival MSCs to secrete exosomes rich in miRNA-1260b, which inhibits non-canonical Wnt5a and JNK signaling, downregulates RANKL, upregulates OPG, reduces osteoclastogenesis, polarizes M2 macrophages, and enhances alveolar bone repair in murine periodontitis.172 IL-6 activates canonical Wnt signaling via Wnt2b/Wnt10b and non-canonical signaling via Wnt5a, collectively inducing osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells to promote alveolar bone regeneration.179

The NF-κB pathway directly influences inflammatory alveolar bone repair by regulating cytokines and mediators expression. In a ligature and Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide induced murine periodontitis model, dimethyloxaloylglycine enhances hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression, suppresses NF-κB phosphorylation, downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines, upregulates anti-inflammatory cytokines, reduces the M1/M2 macrophages ratio, inhibits osteoclast differentiation, attenuates alveolar bone resorption, and increases alveolar bone volume and density.174 Intraperitoneal injection of pirfenidone inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway in bone marrow-derived macrophages, suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α induced by lipopolysaccharide, as well as inhibiting RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis, which significantly mitigates alveolar bone loss.175 NF-κB also indirectly affects bone repair by regulating inflammasome assembly, pro-inflammatory factor maturation and pyroptosis. IL-37 inhibits NF-κB to suppress nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome, reducing osteoclast numbers, calcitonin receptor/RANKL/IL-10 expression, while increasing OPG/IL-1β/IL-6/TNF-α levels, ultimately alleviating alveolar bone resorption.180,181

Periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), a subset of dental pulp stem cells, exhibit unique multi-lineage differentiation into cementum, osteoid, and periodontal ligament-like tissues. This multi-lineage differentiation potential has not been observed in other MSCs, making it a unique characteristic of PDLSCs.182 PDLSCs are ideal seed cells for true periodontal regeneration, but inflammatory microenvironments threaten this process by exacerbating tissue destruction and impairing the osteogenic differentiation and migration of PDLSCs.183,184 Tetrahedral framework nucleic acids (tFNAs), with unique biological properties, enhance proliferation and osteogenic/odontogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells (DPSC)/PDLSC and exert anti-inflammatory/antioxidant effects by inhibiting MAPK phosphorylation in macrophages.185–189 Thereupon, Yunfeng Lin et al.190 discovered in their research that tFNAs can suppress the release of pro-inflammatory factors in cells, along with the production of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), facilitating the migration and osteogenic differentiation of PDLSCs in vitro. It is indicated that tFNAs may exert a protective effect on the osteogenic differentiation of PDLSCs in inflammatory conditions. Furthermore, in the murine periodontitis model, tFNAs reduce inflammatory cell infiltration, downregulate IL-6/IL-1β, inhibit osteoclastogenesis, and protect periodontal tissues (Fig. 2b). Moreover, tFNA activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling to drive proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of PDLSCs. Since its development, tFNA functionalization strategies have been extensively explored. Professor Yunfeng Lin’s team has applied tFNA to orthopedic, metabolic diseases, sarcopenia, bladder obstruction, and cancer,191–196 establishing new frameworks for nucleic acid aptamer research. This material offers novel tools for fundamental studies on nucleic acid functions and structure-activity relationships, while holding diagnostic and therapeutic potential for previously intractable diseases.

Articular cartilage and osteochondral tissue

Articular cartilage is a type of hyaline cartilage primarily composed of proteoglycans and type II collagen within the matrix. It is categorized into deep, middle, and superficial zones.197,198 The meniscus is one of the most significant articular cartilages in the human body, playing an extremely crucial position in protecting the health and integrity of the knee joint during long-term weight-bearing activities. Cartilages like the meniscus lack the capacity to generate adequate healing responses independently.199 Previously, research on the reconstruction and regeneration of cartilages and osteochondral tissues posed considerable challenges. Yet currently, with the emergence and maturity of new technologies, many of these difficulties are gradually being conquered.

The meniscus can be divided into three different zones: the highly vascularized (red) peripheral region, the avascular (white) inner region, and the red-white transitional region, which possesses characteristics of both.200 Meniscus tears are generally recognized to heal poorly due to inadequate vascular supply and reduced cell proliferation.200–202 Vascular supply is critical for the healing of the meniscus. The superior, lateral, and medial genicular arteries, branching from the popliteal artery, provide the primary blood supply to the meniscus, forming peripheral capillary plexuses within the synovial and capsular tissues of the knee joint.202–206 In adults, vascularization is limited to the peripheral 10%–25% of the meniscus, and the extent of this vascularized area determines the healing potential of tears.202 Because of the supply of oxygen, essential factors, and nutrients from adjacent blood vessels, tears in the vascularized area can facilitate tissue healing, while injuries in the avascular region remain irreparable.207 Insufficient blood supply leads to deficiencies in nutrients, oxygen, and other critical elements, restricting the repair capacity of the meniscus’s avascular region.208 In terms of biomechanics, clinical studies have shown that cartilage damage always extends deeply into the subchondral bone, resulting in osteochondral defects in the knee joint. These defects alter joint biomechanics and impair the long-term performance of cartilage tissue,199 underscoring the vital importance of simultaneous articular cartilage and subchondral bone restoration for successful knee joint repair.

Currently, treatment strategies mainly consist of arthroscopic suture, partial or total meniscectomy, and meniscal allograft transplantation (MAT). Nevertheless, arthroscopic meniscectomy inevitably results in progressive cartilage degeneration and osteoarthritis.209 While MAT has been clinically implemented, it faces challenges such as donor scarcity, implant shrinkage, and disease transmission risks.210 Aptamers are widely used in various biomedical applications, including disease diagnosis, drug delivery, and biosensors, because of their high affinity, specificity, and stability. In meniscus research, aptamers may be utilized to recognize and target specific biomarkers of meniscus injury or degeneration, thereby facilitating early diagnosis and treatment of the condition. Moreover, nucleic acid technologies like PCR and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) have demonstrated significant potential in pathogen identification for joint prosthesis infections, with mNGS showing 95% sensitivity and 94.7% specificity in diagnosing PJI.211–213 These findings highlight nucleic acid technologies’ diagnostic precision, further exemplified by aptamers’ ability to target and diagnose specific biomarkers.

In recent years, MSC transplantation and their directed differentiation into chondrocytes have become a preferred approach for cartilage repair.214 Nevertheless, exogenous stem cell transplantation frequently faces challenges in cartilage tissue engineering, such as the absence of a targeted delivery system for MSCs, the low survival rate of exogenous cells, and the risk of exogenous infection during in vitro culture and cell proliferation.67,215,216 Currently, an aptamer-bilayer scaffold for knee joint repair has been developed,217 comprising an aptamer-gel for cartilage regeneration and an aptamer-functionalized 3D graphene oxide-based biomineral framework for bone regeneration. MSC-specific aptamers anchored on this scaffold enable targeted MSC recognition, binding, and recruitment to osteochondral defect sites (Fig. 3a). The aptamer-gel incorporates kartogenin, a chondrogenic factor, which is released sustainably to accelerate MSC differentiation into chondrocytes for cartilage regeneration. As type II collagen abundance reflects regenerated cartilage quality and maturity,218,219 comparisons with the aptamer-bilayer scaffold reveal inferior type II collagen staining, reduced cell density, and limited subchondral bone formation in standalone aptamer-gel applications (Fig. 3b).217 This demonstrates the bilayer scaffold’s superior repair efficacy. Based on Apt19S, a DNA aptamer targeting pluripotent stem cells,220 Hao et al.221 proposed a meniscus regeneration strategy combining endogenous stem/progenitor cell (ESPC) recruitment with fibrocartilage formation. They developed a 3D scaffold featuring a biomimetic microstructure and the MSC-specific aptamer Apt19S. This scaffold can sequentially activate the homing of ESPCs and the differentiation of fibrocartilage, achieving superior meniscus regeneration and protection of articular cartilage. It presents a potential alternative for meniscus tissue regeneration and a ready-made cell-guided meniscus product for clinical applications. In addition, gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogel loaded with circular bispecific synovial-meniscal aptamers has been proven to be effective for avascular meniscus repair by recruiting endogenous synovial and meniscus cells and facilitating fibrocartilage regeneration (Fig. 4a). In a rabbit meniscus defect model, this approach demonstrated fibrocartilage-like tissue formation, reduced cartilage degeneration, and improved mechanical strength 12 weeks post-operation (Fig. 4b).222 Aptamers’ role in articular cartilage and osteochondral therapy lies in their potential as novel biomaterials for repair and regeneration. Engineered aptamers can modulate post-injury inflammation by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines or accelerate repair by promoting fibroblast proliferation and differentiation. They may also serve as drug delivery components to enhance therapeutic precision and minimize side effects. However, translating these concepts into clinical practice requires further validation of aptamer safety, efficacy, and optimal application methods, including thorough investigation of in vivo biocompatibility, long-term stability, and tissue interactions. In summary, aptamers hold diverse therapeutic potential for cartilage repair, spanning inflammation regulation, tissue regeneration, and targeted drug delivery.

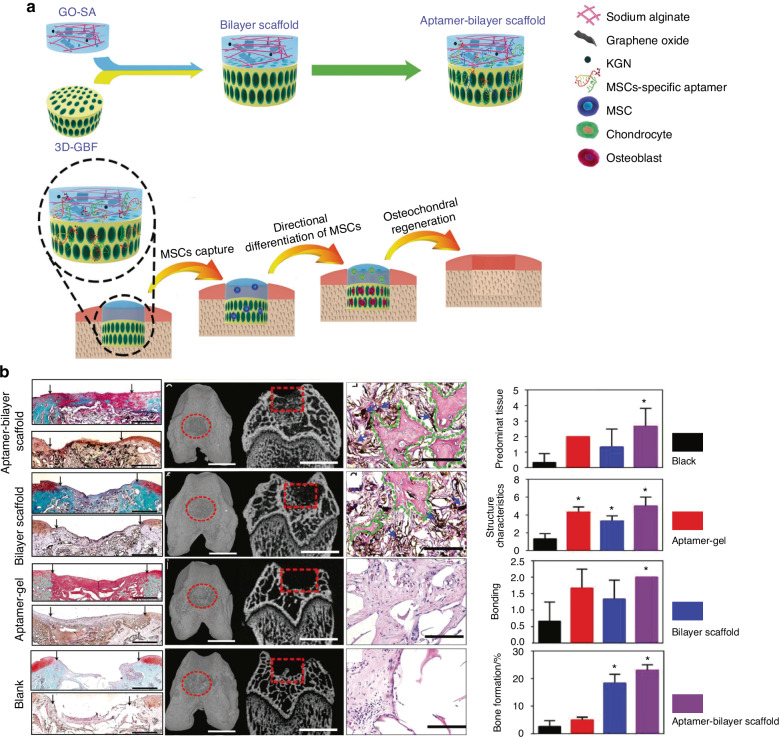

Fig. 3.

Preparation process of a nucleic acid aptamer-bilayer scaffold and its therapeutic evaluation for osteochondral defects. a Overview of the aptamer-bilayer scaffold in osteochondral defect repair. b The scaffold was implanted into the osteochondral defect in rats. After an eight-week healing period, histomorphological analyses were performed, including safranin-O staining for glycosaminoglycans (GAG) and immunohistochemical staining for collagen type II to evaluate cartilage regeneration. Concurrently, microcomputed tomography (μCT) reconstruction and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of articular joint samples were conducted to assess subchondral bone regeneration. The aptamer-bilayer scaffold demonstrated significantly higher scores across all evaluated parameters compared to other groups. Reproduced form ref. 217 with permission from Wiley, copyright 2017

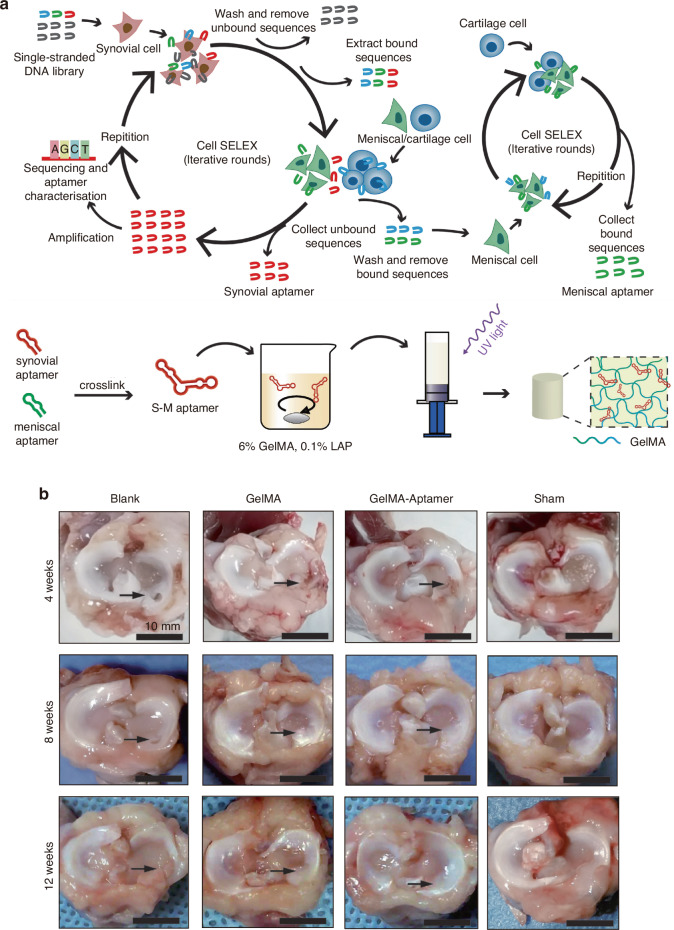

Fig. 4.

Preparation process of a bispecific GelMA-aptamer system and its therapeutic evaluation for meniscus defects. a Technological procedure for the filtration of aptamers and construction of the bispecific GelMA-aptamer system. b Observations of menisci at 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-surgery. Black arrows indicate the defect sites. Blank group, no repair; GelMA group, repair with GelMA hydrogel; GelMA-aptamer group, repair with GelMA hydrogel and bispecific aptamer; sham group, uninjured meniscus. Reproduced form ref. 222 with permission from SAGE Publications Inc., copyright 2023

Osteonosus

Osteonosus encompasses a broad spectrum of bone-related disorders involving diverse pathological mechanisms, including genetic, metabolic, inflammatory, or tumorigenic processes. These diseases may be congenital such as achondroplasia and osteogenesis imperfecta.223,224 Alternatively, these disorders may be acquired, such as diabetic bone disease, cancer-associated bone disorders, or osteoarthritis resulting from sports injuries.225–227 Similar to osteoporosis, osteonosus often involves genetic predisposition interacting with non-genetic factors, including endocrine imbalances, chronic inflammation, or systemic diseases. Under physiological conditions, bone tissue develops via intramembranous and endochondral ossification, initially forming weaker woven bone that is subsequently replaced by stronger lamellar bone.228 However, pathological states disrupt the balance between bone resorption and formation, leading to net bone loss and reduced bone mass.229 In summary, osteonosus represents a complex group of disorders frequently linked to genetic mutations, multifactorial pathogenesis, and impaired bone function.

Osteoporosis

In 1984, osteoporosis was defined as an age-related disease characterized by reduced bone mass and increased susceptibility to fractures.230 In 2001, the definition was revised to characterize osteoporosis as a skeletal disorder marked by compromised bone strength and an increased susceptibility to fractures, where bone strength is primarily determined by bone mineral density and bone quality.231,232 As the extent of population aging continues to deepen, osteoporosis emerges as an extremely crucial public health concern, imposing escalating socioeconomic burdens.233 In the USA, ~1.5 million fragility fractures occur annually,234 while UK epidemiology predicts lifetime osteoporotic fracture risks of 50% for women and 20% for men aged ≥50.235 Fracture risk escalates with age, particularly among the elderly, and is associated with substantial healthcare costs, functional impairment. The risk of hip fractures is particularly significant and is correlated with higher rates of disability and mortality.231

Osteoporosis pathogenesis centers on disrupted bone remodeling-resorption equilibrium. Estrogen potently inhibits osteoclast recruitment/activity in early menopause, suppressing bone resorption. Estrogen deficiency increases osteoclast numbers/lifespan while promoting osteoblast apoptosis, leading to trabecular thinning, cortical porosity, and accelerated remodeling, thereby causing bone mass loss.236–238 Remodeling initiates via osteoblast/osteocyte signals activating osteoclast-mediated resorption followed by bone formation.231,239,240 Excessive remodeling reduces bone mass and strength, promotes microdamage accumulation, and predicts fracture risk; lowering remodeling rates mitigates this risk.231,241,242 In osteoporosis, excessive remodeling degrades bone material properties, including bending resistance, elasticity, toughness, and strength.231,243,244 Moreover, osteoporosis is related to a decrease in the quantity and size of trabecular bones, their thinning, and transformation into a rod-like shape, replacing the stronger plate-like structures found in non-osteoporotic bone. In most osteoporosis patients, excessive remodeling may be the primary factor contributing to alterations in bone microarchitecture, as it leads to the loss of trabecular bone connectivity and further undermines the structural stability of the bone.231,237 In terms of mechanical loading, a deficiency in load will cause bone loss and an increase in remodeling activity.245 On the other hand, excessive loading can lead to an increase in microdamage.246,247 Microdamage is a reaction to repeated submaximal loads. It can sever lamellae and canaliculi, disrupt osteocytes communication, and induce osteocyte apoptosis. Subsequently, microdamage targeted for removal by osteoclasts is removed and repaired by osteoblasts.231,248,249 The optimal range of mechanical loading should fall between the two extremes, ensuring effective repair of microdamage without becoming excessive. Microdamage accumulates with advancing age, and it increases at a more rapid pace in women.250 In healthy postmenopausal women, bone remodeling doubles in the early stage and triples after 10–15 years.251 With increasing age, the body’s capacity to defend against oxidative stress diminishes. Some scholars have identified ROS as a contributing factor to the development of osteoporosis.252,253 Furthermore, the bone microstructure is disrupted to varying degrees, which impacts both bone quality and fracture resistance. Meanwhile, cortical bone undergoes structural changes because of aging and the menopausal transition.254,255 The occurrence of osteoporosis is also linked to genetic factors. Research has revealed that a single gene or a group of genes may determine bone mass at different skeletal locations. This suggests that genetic influences may affect an individual’s ability to accumulate and maintain bone mass throughout their lifetime, thus affecting the risk of developing osteoporosis.

A deficiency in estrogen increases the rate of bone remodeling. Even before menopause, a negative remodeling balance between bone resorption and formation can result in bone loss and compromise bone structure and strength256. Anti-osteoporosis medications reduce the rate of bone remodeling by either diminishing bone resorption or enhancing bone formation. For example, estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and bisphosphonates exert their effects primarily by inhibiting bone resorption, whereas intact parathyroid hormone functions as a powerful anabolic agent that increases bone formation.257,258 Currently, bisphosphonates are effective in reducing the risk of fractures and are relatively cost-effective. However, they are associated with gastrointestinal side effects. More critically, long-term application of bisphosphonates may simultaneously suppress the functions of both osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Even worse, prolonged administration may lead to osteonecrosis of the jaw and increase the risk of certain malignancies.259,260 In recent years, the exploration of various biological mechanisms in scientific research has deepened significantly. In the realm of osteoporosis research, an increasing number of studies indicate that the gut microbiota may serve as a potential target for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Against this backdrop, the research concept of the “gut-bone axis” has gradually emerged and gained widespread attention. The nutrients ingested by the human body, along with the dietary patterns adopted, can influence the gut microbiota. In turn, changes in the gut microbiota may affect the host’s metabolic state, thereby regulating the process of bone metabolism. According to the gut-bone axis theory, dietary intake can participate in the regulatory mechanisms of bone metabolism by altering the abundance, diversity, and composition of the gut microbiota.261–264 An imbalance in the gut microbiota can result in intestinal inflammation, which releases various inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. These factors can further exacerbate the inflammatory response, causing adverse reactions such as damage to the intestinal mucosal barrier and immune dysfunction in the host, leading to the occurrence and progression of a series of diseases.265–267 These factors activate the RANKL signaling pathway, enhancing osteoclast function, which results in osteoporosis and bone loss.268–270 Nucleic acid aptamers can effectively modulate these inflammatory factors, alleviate inflammation, and subsequently influence bone metabolism.271–275 Multiple studies have shown that probiotics can enhance the integrity of the intestinal epithelium, prevent barrier degradation, and reduce pro-inflammatory responses.276,277 After effective probiotic intake in murines, there is an increase in the populations of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli in the gut, along with elevated levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), significant enhancements in bone density, and improvements in bone microstructure.278–281 SCFAs are key regulatory factors in osteoclast metabolism and bone mass.282 Propionate and butyrate can induce metabolic reprogramming in osteoclasts, leading to a downregulating of bone resorption and the protection of bone mass.267 Probiotic supplementation can significantly improve the gut environment and reduce the expression of inflammation-related factors.283–286 Research also indicates that a high-calcium diet combined with probiotic intervention can further amplify protective effects on murine bones, suggesting a potential synergistic relationship between diet and the microbiota. Probiotics can improve the efficiency of calcium absorption in the gut and enhance calcium utilization through the regulation of the gut microbiota, thereby increasing bone density and bone mineral content.287 For nucleic acid aptamers, their capacity to efficiently promote calcium absorption and foster the generation and survival of probiotics is a critical factor in determining their potential to improve the intestinal microenvironment. If nucleic acid aptamers demonstrate strong efficacy in these two areas, they could provide a novel and potent approach to optimizing gut microecology and boosting intestinal health.

Advancements in molecular biology and genetic engineering have promoted the development of aptamers, which serve as novel biomolecular tools that demonstrate significant potential in the study of osteoporosis. Furthermore, aptamers can regulate gene expression by specifically targeting nucleic acid sequences, thus affecting cellular functions related to bone formation and resorption. miRNAs represent a category of non-coding small RNAs that bind to target messenger RNAs (mRNAs). This binding results in either the degradation of the target mRNAs or the inhibition of their translation, ultimately regulating the expression of specific genes.288–290 Previous research has indicated a significant role of miRNAs in the process of bone remodeling, particularly in regulating the differentiation and function of both osteoblasts and osteoclasts.291,292 Furthermore, long non-coding RNAs are implicated in various signaling pathways and in the regulation of miRNAs during the process of bone formation.293 Three polymorphic loci within the FGF2 gene have been identified as being significantly correlated with femoral neck bone mineral density. Acting as potential binding sites for specific miRNAs, these loci may influence the expression of the FGF2 gene by altering the binding affinity between miRNAs and their target mRNAs.294 This suggests that modulating the activity of specific miRNAs could potentially serve as a novel therapeutic approach for osteoporosis. Circular RNAs (circRNAs), as a novel type of RNA molecule, have demonstrated significant importance in osteoporosis research. circRNAs influence bone metabolism by participating in the regulation of the differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis of BMSCs.295,296 These research findings offer a new direction for the development of novel diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets. The previously mentioned CH6-LNPs-siRNA directly injects osteogenic Plekho1 siRNA into osteoblasts, leading to better bone microstructure and increased bone mass in tissues of osteopenic and healthy rats. Injecting an endothelial-specific aptamer-agomiR-195 system into aged murines can enhance the formation of CD31hiEmcnhi blood vessels and reverse age-related osteoporosis (Fig. S1). Utilizing SELEX technology, endothelial-cell-specific aptamers are screened and aptamer candidate 2 (Table 1) with higher binding ability and a satisfactory secondary structure is selected. A small RNA molecule, agomiR-195, which mimics the function of miR-195, is synthesized. Subsequently, 1 volume of polyethyleneimine solution (100 μg/mL, pH 6.0) is mixed with six volumes of 4.2 μmol/L sodium citrate to form a polyethyleneimine-citric acid core structure (nanocore). Then, three volumes of the synthesized aptamers (50 nmol/L) and agomiR-195 (1 μmol/L) are added into the nanocore, and the mixture is reacted for 5 min to assemble into a nano-complex, namely aptamer-agomiR-195.297 Furthermore, an aptamer-antagomiR-188 targeting system has successfully and selectively silenced miR-188 in BMSCs, which in turn increases bone formation and reduces the accumulation of bone marrow fat in aged murines (Fig. S2).298 This system assembles into a nano-complex (Table 1) after obtaining the aptamer sequence with the highest binding affinity to murine BMSCs through the same technology previously described. Despite the significant potential of aptamers in osteoporosis research, several challenges persist regarding their clinical applications. Rapid renal filtration and metabolic instability result in the rapid clearance, degradation or structural alteration of aptamers, ultimately influencing their therapeutic efficacy. This occurs due to the relatively low molecular weight of aptamers, which enables them to easily traverse the glomerular filtration membrane, leading to a reduced half-life in the body and an inability to maintain adequate concentrations at the site of action, significantly impacting therapeutic efficacy.299,300 The glomerular filtration membrane has a specific pore size, typically around 4–5 nm, allowing small molecules to pass freely.301 The molecular weight of nucleic acid aptamers generally ranges from 5 to 15 kDa, which is considerably lower than the retention threshold of the glomerular filtration membrane (30–50 kDa), facilitating their smooth passage through the membrane and rapid clearance.60,299 Previous studies have chemically modified aptamers by conjugating them with macromolecules like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or cholesterol to enhance their molecular weight, which slows their passage through the glomerular filtration membrane and prolonging their half-life in the body.302–304 Furthermore, new drug delivery systems, such as nanoparticle carriers, can be developed to encapsulate aptamers, shielding them from rapid renal clearance and achieving targeted delivery, thus enhancing their stability and therapeutic effectiveness in the body. Additional issues such as polyanion effects, unexpected tissue accumulation, and non-specific immune activation further elevate the risk of potential side effects. Therefore, future studies must focus on strategies to enhance the biological properties and efficacy of aptamers while exploring effective methods to translate these findings into clinical therapeutic approaches.

Bone tumor

From a historical perspective, the classification of bone tumors has experienced numerous changes and amendments. As early as the 1950s, researchers had already initiated revisions to the classification of bone tumors; however, this classification still possessed certain limitations. Subsequently, additional research and findings have prompted further refinement of the classification. In 2013, the fourth edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors updated the classification of bone tumors. The classification categorizes bone tumors into three categories based on their biological behavior: benign, intermediate (including subgroups of locally invasive and rarely metastatic), and malignant.305 Benign tumors only recur sporadically and are non-destructive. These tumors can be removed or curetted locally. The intermediate type is subdivided into locally invasive and rarely metastatic subtypes. Locally invasive tumors have a high recurrence propensity and show invasive and destructive growth, yet there is no risk of metastasis. Generally, extensive resection or the implementation of adjuvant measures is necessary for effective treatment. The rarely metastatic subgroup typically demonstrates locally invasive growth with a relatively low metastatic propensity of less than 2%. Malignant tumors are characterized by destructive growth, a high recurrence propensity, and a significant risk of metastasis, typically exceeding 20%. These tumors necessitate surgical intervention in conjunction with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy.306 The most recent classification standard for bone tumors is the fifth edition released by the WHO in 2020. This edition does not introduce significant changes to the classification of bone tumors; however, it includes new tumor entities and provides descriptions of subtypes for existing tumor types. Meanwhile, it integrates new molecular and genetic data.307

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma (OS) is a primary malignant skeletal tumor characterized by malignant mesenchymal cells that directly form immature bone or osteoid tissue.308,309 Typically, 80%–90% of osteosarcomas occur in long tubular bones. Conventional osteosarcoma accounts for ~15% of all primary bone tumors subjected to biopsy analysis. Among primary malignant bone tumors, its incidence is surpassed only by that of multiple myeloma.309 Patients are generally younger, with a higher prevalence in males than females, while those under 6 years old or over 60 years old rarely develop this disease.309–311 Its characteristics include a high propensity for metastasis, mainly to the lungs, and pathological fractures resulting from bone destruction.312,313 The etiology of osteosarcoma remains unclear, although evidence suggests that human osteosarcoma can be induced by viruses or cell-free extracts from human osteosarcoma, and ionizing radiation is a recognized environmental factor contributing to its development.314 Besides, osteosarcoma also shows genetic susceptibility, as several families have been reported with multiple members affected.315 Screening of a significant number of children with osteosarcoma reveals that around 3% to 4% carry germline mutations in the p53 gene, indicating a family history consistent with Li-Fraumeni syndrome.316

Through Cell-SELEX, the specific DNA aptamer OS-7.9 (Table 1) targeting MG-63 osteosarcoma cells has been successfully identified. It has been verified that the OS-7.9 aptamer has a greater affinity for osteosarcoma cancer cells, shows no affinity for human bone marrow neuroblastoma, and can bind to lung cancer and colorectal cancer cell lines.317 This suggests that there may be common markers shared between osteosarcoma cells and these cells, with the OS-7.9 aptamer potentially serving as a valuable probe in cancer research. It could be applicable in developing early diagnostic approaches and treatment methods for metastatic diseases, as well as in identifying common membrane proteins present in different cancer types. To improve the diagnostic capabilities for osteosarcoma, the selected single-stranded DNA aptamer LP-16 can specifically bind to osteosarcoma cells and is the first aptamer to identify metastatic osteosarcoma cells.318 Research has shown that combining aptamers with salinomycin or clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-associated Cas9 nuclease (CRISPR/Cas9) can decrease tumor volume and malignancy in osteosarcoma.319,320

Metastatic bone tumor: Bone is a primary site for many tumor metastasis.321 The occurrence and metastasis of high-grade and high-stage cancers are associated with the heterogeneity deletion of specific gene loci.322,323 For instance, miR-15a and miR-16-1 are tumor suppressor genes located on chromosome 13q14 and are correlated with the expression of genes like BCL2, CCND1, and WNT3A, which play direct roles in cell survival, proliferation, and invasion processes.324–328 The loss of these genes may facilitate the survival, proliferation, and invasion of cancer cells. Aberrant expression of these miRNAs in tumor cells can lead to a more aggressive metastatic capacity. On the other hand, bone metastasis may also be influenced by interactions within the bone microenvironment. During the invasion of tumor cells, a variety of adhesion receptors are implicated. These adhesion events are of great significance for the invasion, metastasis, and ultimate establishment of new tumors by tumor cells. These adhesion receptors connect the extracellular environment with intracellular signaling by binding to extracellular ligands in the tumor microenvironment, thus enhancing tumor cell migration, invasion, proliferation, and survival.329,330 Tumor cells can colonize and proliferate within bone tissue through adhering to specific components. They are capable of stimulating the activity of osteoclasts, resulting in enhanced bone resorption. Conversely, they may also impact the function of osteoblasts and facilitate bone formation.331 This imbalance in bone metabolism creates a conducive microenvironment for tumor cells growth. Moreover, tumor cells secrete large amounts of pro-angiogenic factors, giving rise to an aberrant, disorganized, immature, and poorly permeable vascular network.332 The blood vessels supply oxygen and nutrients to tumor cells, and tumor angiogenesis remarkably accelerates growth and increases the metastatic potential of the tumor.333

Numerous aptamers have been shown to suppress tumor metastasis. For angiogenesis, Rana et al.334 demonstrated an aptamer-based dynamic platform for the spatiotemporal control of the bioavailability of an angiogenic growth factor by utilizing affinity interactions within a biofabrication-friendly polymer matrix, aiming to realize a mature and stable vascular network. The RNA aptamer A10-3.2 is a new ligand for bone-metastatic prostate tumors that expresses the prostate-specific membrane antigen and is conjugated with atelocollagen (ATE) to deliver miR-15a and miR-16-1. It synergistically induces selective death of prostate cancer cells and augments the anticancer efficacy of the system.324 As a specific aptamer targeting complement C5a, AON-D21 can block the C5a/C5aR1 signal axis, effectively reducing the bone metastasis and tumor burden in lung cancer (Fig. S3).335 Research indicates that BMSCs are capable of migrating from the primary tumor site to the bone marrow, with the migration dependent on osteopontin (OPN). When OPN is blocked by the R3 aptamer, BMSCs are unable to migrate to the bone marrow.336

Multiple myeloma

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell neoplasm characterized by clonal proliferation within the bone marrow microenvironment. Although it is classified as a hematologic malignancy, it exhibits a distinct propensity to develop almost exclusively within the bone marrow, leading to severe bone destruction. This occurs by augmenting bone resorption through osteoclasts while simultaneously suppressing bone formation.337 Consequently, MM is specifically addressed here for discussion and analysis.

The occurrence of bone disease in MM is analyzed at the cellular level. The predominant pathogenesis of MM-induced bone disease is attributed to the up-regulation of osteoclast differentiation and activity, resulting in unbalanced bone resorption and the initiation of characteristic lytic bone lesions.338 Several factors mediate the activation of osteoclasts in MM patients. MM cells directly secrete cytokines capable of generating osteoclasts, including IL-1, IL-3, IL-6, TNF-α, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and decoy receptor 3.339–344 It has been previously mentioned that RANKL and OPG play a core role in osteoclast differentiation. The adhesion between MM cells and BMSCs triggers the expression of RANKL in osteoblasts and advances osteoclast differentiation by stimulating the NF-κB and Jun N-terminal kinase pathways. Therapeutic methods that normalize the RANKL/OPG ratio by increasing OPG and/or decreasing RANKL can effectively impede bone destruction and MM growth in vivo.345 Both MM cells and osteoclasts secrete elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine MIP-1α.346 MIP-1α facilitates the survival and migration of MM cells, stimulates the generation of osteoclasts by activating the ERK and AKT signaling pathways, and downregulates bone formation-related transcription factors (eg, osterix) to inhibit osteoblast differentiation, thereby reducing bone formation.347–349 Moreover, a recent study indicated that osteoclasts protect MM cells from T cell-mediated cytotoxicity by directly inhibiting proliferating T cells.350 This defective T cell-mediated reaction is a crucial mechanism for tumors to evade immune surveillance.351 The immunosuppressive function of osteoclasts and their key role in lytic bone diseases could be considered important targets for the treatment of MM.

The differentiation of MSCs into bone cells is governed by the activation of two principal transcription factors: runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and osterix.352 These transcription factors are vital for the maturation and ossification of osteoblasts and depend on the typical Wnt signaling pathway.353 Whereas, myeloma cells secrete various Wnt antagonists like dickkopf-1 (DKK1) and sclerostin (SOST). These proteins compete for the same Wnt signaling receptors, suppressing the differentiation and function of osteoblasts.354–358 Studies conducted both in vitro and in vivo have demonstrated that blocking DKK1 and augmenting Wnt signaling can restore the quantity of osteoblasts and trabecular bone, along with a reduction in tumor burden.359–362 After treating myeloma murines in vivo with a SOST-neutralizing antibody, results indicated a decrease in bone loss and lytic lesions, although there was no impact on tumor burden.363

In terms of bone marrow adipocytes, while there is no direct connection with MM bone disease, emerging evidence shows that adipocytes support the growth and survival of MM, which is inversely related to bone mass.353 Adipocytes and osteoblast lineage commitment originate from common progenitor cells. Wnt signaling acts as the primary initiator for the osteoblast lineage while simultaneously suppressing adipocyte lineage commitment regulated by the PPARγ signaling pathway.364,365 As people age, bone marrow adipocytes increase, and the rate of bone formation declines.353,366 Obesity is positively correlated with the risk of MM occurrence and is associated with an increase in bone marrow lipid as well.367–369 Furthermore, bone marrow adipocytes are capable of secreting free fatty acids, which serve as an energy source for the proliferation of tumor cells.370 Many lipids function as ligands for nuclear receptors involved in the PPARγ signaling pathway.371 The levels of free fatty acids are generally elevated in MM patients.372 This may result in the up-regulation of the PPARγ signaling pathway, thereby enhancing bone marrow adipogenesis while inhibiting the differentiation of osteoblasts and supporting the survival of MM. A recent in vitro research has indicated that saturated fatty acids, specifically stearate and palmitate, exert a direct lipotoxic effect on human osteoblasts.371,373 Furthermore, the data illustrate that increased adipogenesis during obesity and aging undermines bone regeneration.374 In conclusion, bone marrow fat is emerging as a crucial regulatory factor in the development of MM and bone disorders, potentially representing a novel and promising therapeutic target.

In the treatment of cancer, aptamers can serve as free molecules targeting specific cancer biomarkers as either agonists or antagonists (Fig. 5).375 Both AS1411 and NOX-A12, which have reached the clinical trial stage, are antagonistic aptamers that specifically target nucleolin and CXCL12, respectively.376–379 Nucleolin is highly expressed in multiple tumor cells. Through binding to the nucleolin receptor, AS1411 can play an anti-tumor effect.380 CXCL12 (also known as SDF-1) and CXC receptor 4 (CXCR4) are a chemokine and its receptor.381 CXCR4 is overexpressed in more than 75% of cancer cells, including those of myeloma.382 The CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway is a known crucial regulatory factor for tumor proliferation, cell spread, and migration both within and outside the bone marrow.383,384 NOX-A12 has been evaluated in research studies when used in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone for treating relapsed MM.377 It produces a therapeutic effect on MM by preventing the interaction between CXCL12 and its receptor, thereby interfering with the CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling pathway and inhibiting the growth and proliferation of MM cells. What’s more, the specific aptamer ola-PEG for stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) can neutralize SDF-1 and block SDF-1-dependent signal transduction, effectively suppressing the progression of MM.385

Fig. 5.

The potential application of nucleic acid aptamers in MM. a Aptamer against AXII. b BCMA targeted aptamer. c Aptamer against C-MET. d Conjugated CD38-doxorubicin aptamer and e NOX-A12 RNA aptamer for CXCL12. All the aptamers with the exception of the NOX-A12 spiegelmer are targeted at the receptors that are expressed on the plasma cell membrane of MM. BM bone marrow, Doxo doxorubicin, OBL osteoblast, sAXII soluble annexin A2. Reproduced form ref. 387 with permission from MDPI, copyright 2022

Annexin A2 (AXII) is overexpressed in the plasma cell membrane of MM, and its expression correlates negatively with patient survival rates.386 AXII, a member of the annexin family, is calcium-dependent and binds to phospholipids. The interaction between AXII and its receptor AXIIR augments the adhesion and growth of MM cells within the bone marrow microenvironment,387 potentially supporting the homing and growth of MM cells in this niche. AXII can be secreted by diverse cell types within the bone marrow, facilitating the growth of MM cells by establishing a pro-tumorigenic niche. Therefore, targeting the AXII/AXIIR axis represents a promising strategy for developing treatments against the MM niche.388 Zhou et al.389 have identified an ssDNA aptamer (wh6) that can specifically bind to MM cells expressing AXII both in vitro and vivo, and it can also suppress the adhesion and progression of MM cell lines induced by AXII. This shows that the wh6 aptamer is suitable for targeted MM therapy.

B cell maturation antigen (BCMA), a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, is preferentially expressed by mature B lymphocytes but is rarely expressed in hematopoietic stem cells.390 The ligands for BCMA, such as B-cell activating factor and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), can activate the NF-κB pathway.387,391,392 Nevertheless, the overexpression of BCMA and increased activation correlate with the progression of MM. These key genes exhibit a state of overexpression, facilitating the upregulation of the NF-κB pathway as well as the growth and survival of MM.390,393 In this context, Catuogno et al.393 selected a BCMA-targeted internalizing RNA aptamer (apt69.T) via Cell-SELEX, which demonstrated the inhibitory capacity on the APRIL-induced NF-κB pathway.

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) constitutes a specific ligand for the tyrosine kinase receptor C-MET.394 In MM, the expression of C-MET progressively augments during disease progression, and its elevated expression is correlated with a poorer prognosis for MM patients. Upon binding of HGF, C-MET dimerizes and initiates the processes that promote cell growth, migration and angiogenesis while inhibiting apoptosis, ultimately enhancing the development of MM.395 SL1 is the truncated form of the original CLN0003 ssDNA aptamer. This aptamer was obtained via the filtered SELEX method against purified C-MET to identify tumors with overexpressed C-MET.396,397 Previous research has proven that targeting C-MET with the SL1 aptamer can inhibit HGF-dependent C-MET signaling and restrain the growth of MM cells.

CD38 is a kind of cell surface glycoprotein that shows especially extensive and high expression levels in MM, contributing to the disease’s progression.387,398 Consequently, it has become one of the primary targets for developing anti-MM targeted therapy in recent years. Wen et al.399 identified a CD38-specific ssDNA aptamer using a hybridization protein and Cell-SELEX method. Subsequently, doxorubicin was non-covalently coupled to create a CD38-specific aptamer drug conjugate. It can be readily internalized by MM cells. Following pH-dependent release in lysosomes, doxorubicin is capable of exerting its specific anti-tumor activity by inhibiting tumor growth in both in vitro and vivo models.387

Osteoarthritis

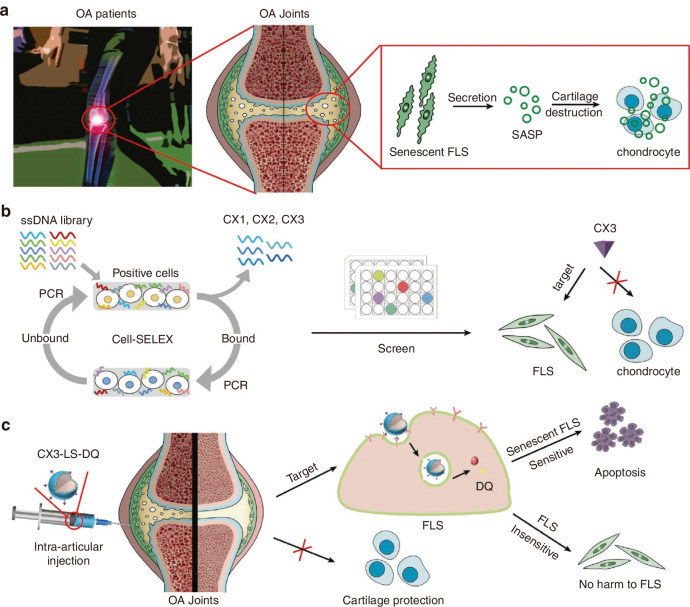

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease characterized by joint pain, tenderness and restricted mobility. As the most prevalent form of arthritis globally, it exhibits the highest incidence among all arthritis types.400 Evidence suggests that ~240 million individuals worldwide suffer from symptomatic OA, making it a leading contributor to physical disability and diminished quality of life.401,402 The primary therapeutic goals are pain management and avoidance of treatment-related toxicity.403 The knee joint is the most frequently affected site, with higher prevalence among the elderly, particularly females.400,404–406 Originally, OA was attributed to mechanical wear of articular surfaces;407 however, it is now recognized to involve genetic predisposition, aging, hormonal influences, lifestyle factors, and other contributors. Its typical pathological characteristics include degeneration of articular cartilage, sclerosis of subchondral bone, synovial lesions, and joint inflammation.408,409 In the synovial joint of the knee, critical structures such as the meniscus, articular cartilage, subchondral bone, and synovium collectively mediate these pathological changes while maintaining joint functionality. Ji et al.410 revealed significant dysregulation of miR-141/200c in OA cartilage tissue. Regulating miR-141/200c levels profoundly affects chondrocyte proliferation, apoptosis, and metabolic markers. Utilizing a Cell-SELEX system, researchers identified chondrocyte-specific aptamers (tgg2, tgg5, tgg8) (Fig. S4). The tgg2 aptamer possesses a more satisfactory secondary structure and shorter nucleotide sequence for nanoparticle conjugation. Based on this, an aptamer (tgg2)-PEG2000-PAMAM6.0-cy5.5 nanoplatform for delivering miR-141/200c was developed (Fig. 6a). In the destabilized medial meniscus model of OA, intra-articular injections of miR-141/200c inhibitors significantly alleviate the OA pathology via SIRT1/IL-6/STAT3 pathway modulation, reduces chondrocyte apoptosis, and increases pain thresholds (Fig. 6b, c).

Fig. 6.

The mechanism of nucleic acid aptamers on chondrocytes in the pathological process of OA. a Schematic representation of the synthesis of tgg2-PEG2000-PAMAM6.0-Cy5.5. b Differentiated diffusion models of cationic nanocarriers binding to the negatively charged extracellular matrix (ECM) of chondrocytes via electrostatic interactions, followed by delivery into chondrocytes in normal and OA cartilage. c Modulation of the SIRT1/IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway by miR-141/200c. Reproduced form ref. 410 with permission from Elsevier, copyright 2021