Abstract

Mechanosensitive thrombospondins (TSPs), a class of extracellular matrix (ECM) glycoproteins, have garnered increasing attention for their pivotal roles in transducing mechanical cues into biochemical signals during tissue adaptation and disease progression. This review delineates the context-dependent functions of TSP isoforms in cardiovascular homeostasis maintenance, cardiovascular remodeling, musculoskeletal adaptation, and pathologies linked to ECM stiffening, including fibrosis and tumorigenesis. Mechanistically, biomechanical stimuli regulate the expression of TSPs, enabling their interaction with transmembrane receptors and the activation of downstream effectors to orchestrate cellular responses. Under physiological mechanical stimuli, TSP-1 exhibits low-level expression, contributing to the maintenance of cardiovascular homeostasis. Conversely, under pathological mechanical stimuli, upregulated TSP-1 expression activates downstream signaling pathways. This leads to aberrant migration, proliferation, adhesion of cardiovascular cells, and collagen deposition, ultimately resulting in diseases including but not limited to atherosclerosis, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), and myocardial fibrosis. In load-bearing musculoskeletal tissues, TSP-1 facilitates the mechanical adaptation of skeletal muscle and promotes cortical bone formation, whereas TSP-2 regulates chondrogenic differentiation. Within fibrotic and neoplastic tissues characterized by altered matrix stiffness, TSP-1 and − 2 exacerbates tissue fibrosis and tumor progression through transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-mediated signaling pathways. These findings establish TSPs as critical mechanochemical switches that govern tissue homeostasis and maladaptation. Clinically, the isoform-specific expression patterns of TSPs correlate with disease severity in atherosclerosis, osteoarthritis, and fibrotic tissues, highlighting their potential as mechanobiological biomarkers. Therapeutically, targeting force-sensitive TSP–receptor interfaces or mimicking their conformational changes under mechanical loading offers innovative strategies for treating mechanopathologies. This review provides a framework for understanding TSP-mediated mechanotransduction across scales, bridging molecular insights for translational applications in mechanopharmacology and ECM-targeted regenerative therapies.

Keywords: Thrombospondins, Mechano-transduction, Extracellular matrix, Cardiovascular system, Musculoskeletal system, Fibrotic tissues, Tumors

Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) constitutes a dynamic network essential for maintaining tissue integrity through mechanochemical coupling [1, 2, 3]. In addition to providing structural support, ECM components mediate mechanotransduction, a process by which mechanical stimuli are converted into biochemical signals regulating development, homeostasis, and repair [4, 5, 6]. Aberrant mechanical microenvironments can disrupt ECM‒cell interactions, triggering pathogenic signaling cascades [5, 7]. In this process, canonical framework proteins such as collagen and fibronectin dominate mechanical load-bearing and signal transmission [4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. Moreover, noncollagenous glycoproteins, particularly thrombospondins (TSPs), also function as critical regulators of mechanoadaptive responses [17, 18, 19]. However, the structural complexity and dynamic spatiotemporal expression patterns of TSPs under mechanical stimuli pose challenges in deciphering their mechanoresponsive behaviors. To date, no systematic review has comprehensively addressed their dynamic expression features, functional adaptations, or mechanistic underpinnings in response to mechanical stimuli.

The TSP family comprises five evolutionarily conserved members that are ubiquitously expressed in mammalian tissues [20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. TSPs exhibit mechanosensitivity across both physiological and pathological contexts. Current research on TSP mechanoresponses predominantly focuses on TSP-1 and − 2, with TSP-3, -4, and − 5 receiving comparatively limited attention. This disparity stems from the earlier discovery of TSP-1 and − 2 within the TSP family, which led to more extensive investigations into their mechanosensitivity. For example, under physiological conditions, shear stress downregulates TSP-1 expression in the vascular endothelium [24, 25]. Mechanical loading increases the levels of TSPs in the musculoskeletal system, modulating force-adaptive changes in muscle tissue and promoting osteochondral formation [26, 27]. Under pathological conditions, abnormal shear stress results in the upregulation of TSP-1 in the cardiovascular system, triggering the development of atherosclerosis [28], thrombosis [29], and other cardiovascular diseases [30, 31]. In fibrotic lesions (particularly those with increased matrix stiffness), TSP-1 and − 2 expression is upregulated [32]. These molecules coordinate mechanochemical signaling by interacting with ECM components, cell-surface receptors, and soluble ligands [20, 21, 33], ultimately leading to the upregulation of fibrogenesis-related proteins and exacerbating fibrotic tissue remodeling. Although studies on TSP-3, -4, and − 5 are limited due to their relatively recent discovery, they are speculated to be mechanosensitive due to their abundant expression in mechanosensitive tissues such as the heart, bone, and cartilage. Specifically, TSP-4 has been investigated for its role and molecular mechanisms in cardiac mechanotransduction under mechanical stimulation [34, 35, 36]. These findings confirm that mechanical forces dynamically regulate the expression of TSPs across different tissues. Through interactions with distinct binding partners, TSPs perform multiple biological functions, thereby driving their functional diversity in tissue-specific contexts [37, 38, 39, 40, 41].

This review delineates the mechano-regulated protein expression patterns and functions of TSPs across diverse biomechanical conditions, with an integrated analysis of their underlying molecular mechanisms in mechanotransduction and tissue mechanoadaptive remodeling. These insights highlight the diagnostic potential of TSP isoforms as mechanobiological biomarkers and their therapeutic potential for load-associated pathologies, ranging from thrombosis, atherosclerosis, and osteoarthritis to fibrotic disorders. Furthermore, the identified force-responsive regulatory networks inform the development of mechanopharmacological interventions and biomechanical tissue engineering strategies.

Structural determinants and functional domains of TSPs

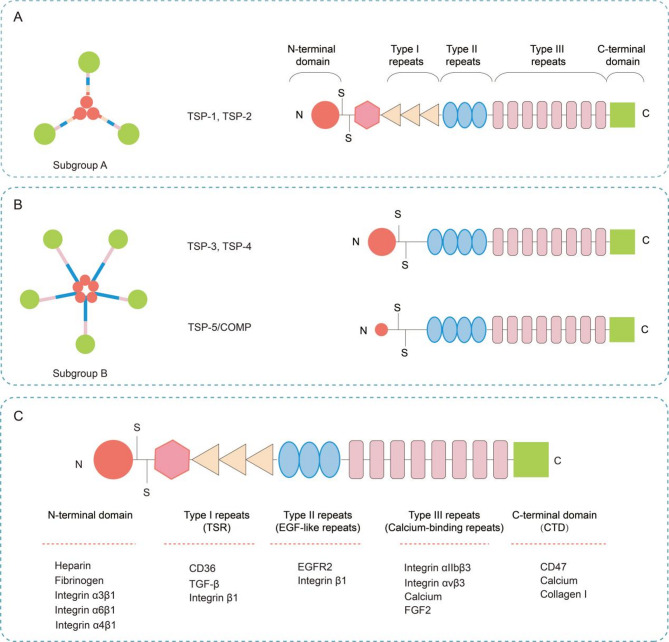

TSPs, a family of calcium-binding secreted glycoproteins, are essential components of ECM molecules. This protein family comprises five evolutionarily conserved members (TSP-1 to TSP-5) and phylogenetically diverse variants identified across species. This review concentrates on canonical mammalian TSPs, with a focused analysis of their mechanoresponsive properties. TSP-1 to TSP-5 are encoded by distinct genes: THBS1 (chromosome 15q15), THBS2 (6q27), THBS3 (1q21), THBS4 (5q23), and THBS5/COMP (19p13.1). Each member exhibits unique structural characteristics and functional domains that mediate specific cellular interactions within the ECM (Fig. 1A, B) [42, 43].

Fig. 1.

Structural classification of the TSP family proteins. (A) Molecular architecture of TSP-1 and − 2; (B) Molecular architecture of TSP-3, -4 and − 5; (C) Proteins interacting with distinct structural domains of TSPs

TSPs are classified into two subgroups on the basis of their structural organization: Subgroup A, which includes trimeric TSP-1 and TSP-2, and Subgroup B, which comprises pentameric TSP-3, TSP-4, and TSP-5/COMP [20, 44]. These proteins share similar domain architectures but differ primarily in their oligomerization domains and specific domain compositions. All TSPs share conserved structural domains critical for their functions, including the C-terminal domain (CTD), calcium binding type III repeats, and epidermal growth factor-like repeats (EGF-like repeats, Type II repeats). These domains are evolutionarily conserved across all TSPs and serve as the molecular basis for their functional specificity. The distinction between the TSP subfamilies lies in their N-terminal and TSR domains (Type I repeats). TSP-1 and TSP-2 (trimeric subgroup) contain an NH2-terminal von Willebrand factor type C (vWF-C) domain and a TSR domain. TSP-3, TSP-4, and TSP-5/COMP (trimeric subgroup) lack those two domains but exhibit additional Type II repeats [21]. The functional diversity of TSPs arises from their ability to interact with a wide range of proteins through specific domains. For example, the N-terminal domain (THBS-N) binds heparin, LRP/calreticulin, fibrinogen, and integrins (α4β1, α3β1 and α6β1). The vWC domain interacts with members of the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) superfamily and fibronectin. The TSR domains engage with integrin β1, CD36, and TGF-β, whereas the EGF-like repeats exhibit affinity for EGFR2 and integrin β1. The calcium-binding repeats mediate interactions with integrins (αvβ3 and αIIbβ3), Ca²⁺, and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2). The CTD serves as a multifunctional hub, mediating interactions with CD47, collagen, and Ca²⁺ (Fig. 1C).

Notably, TSPs exhibit complex molecular architectures and exert their mechanoregulatory functions by interacting with diverse binding partners under distinct mechanical stimuli. First, TSP-1 activates TGF-β via its TSR, which contain a unique TGF-β-activating sequence [45]. This subsequently triggers downstream signaling, promoting collagen deposition and tissue fibrosis across multiple contexts [46, 47]. Under elevated tumor matrix stiffness, TSP-1 enhances tumor cell proliferation through TGF-β/Smad-Akt signaling [48]. Second, the TSR domain of TSP-1 also harbors a CD36-binding motif. Previous reports confirmed that CD36 is extensively implicated in angiogenesis and vascular pathophysiology. Under physiological shear stress, TSP-1 and CD36 are downregulated, which subsequently inhibits tissue angiogenesis. Conversely, the pathological upregulation of TSP-1 initiates platelet activation via the TSP-1/CD36/integrin αIIβ3-Syk axis, driving arterial thrombosis [29]. Third, TSPs also engage integrins (canonical mechanosensors) to regulate mechanoresponses. Pathological shear stress induces TSP-1-mediated platelet adhesion through multiple integrins, promoting thrombosis and atherosclerosis [28, 49, 50]. Fourth, the C-terminal domain of TSPs can bind to CD47. Shear-dependent TSP-1/CD47 binding activates platelets and mediates platelet‒endothelial adhesion. In disturbed flow (d-flow), mechano-triggered assembly of the TSP-1/integrin/CD47 complex drives endothelial cell apoptosis and atherosclerotic plaque formation [50]. Mechanical overload also activates TSP-1/CD47 to induce hypertrophy in muscle stem cells (MuSCs). Finally, TSPs contain multiple Ca²⁺-binding domains. Ca²⁺ binding directly modulates TSP conformation and function (e.g., exposure of the integrin-binding RGD motif), thereby regulating receptor interactions [51]. Mechanical stimuli dynamically alter intracellular Ca²⁺ levels via channel activation, intracellular release, or other signaling pathways. In summary, multiple TSP-interacting molecular materials participate in the regulatory process of mechanotransduction. The detailed mechanisms by which TSPs modulate cell mechanotransduction will be described in detail in the subsequent sections.

Mechanical stimuli-dependent TSP signaling in physiological and pathological cardiovascular remodeling

The cardiovascular system is perpetually subjected to multifaceted mechanical forces [52, 53, 54], which are dynamically perceived by diverse cellular components, including platelets, vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and cardiomyocytes [55]. These cells exhibit mechanosensitive responses to both in vitro simulatable stimuli (e.g., shear stress, cyclic stretch, and hydrostatic pressure) and in vivo composite mechanical microenvironments. Under normal conditions, physiological mechanical stresses, primarily shear stress and cyclic stretch, maintain cardiovascular system homeostasis. In contrast, under pathological conditions, sustained abnormal forces, such as mechanical stress overload, low shear stress (LSS), high shear stress, oscillatory shear stress (OSS), and d-flow, exacerbate histopathological changes. Notably, studies have identified TSPs (especially TSP-1) as key mediators connecting mechanical cues to cellular remodeling. TSPs regulate the differential adaptive remodeling processes induced by mechanical loading. These processes exhibit distinct regulatory patterns between physiological contexts and pathological manifestations. In the cardiovascular system under normal physiological conditions, TSP-1 expression is low, with occasional transient increases exerting protective effects. Conversely, under the influence of pathological forces, sustained high TSP-1 expression can result in the development of cardiovascular pathologies. Below, we systematically elucidate the context-dependent roles of TSPs in cardiovascular adaptation, stratified by force type, physiological stage, and pathological stage (Table 1).

Table 1.

The expression and function of TSPs in cardiovascular cells under distinct mechanical stimuli

| Pathological States | Expression Tissue/Cell Type | Mechanical Stimulus | Name of TSPs | TSPs Function | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular regenerative repair | Endothelial cells (ECs) | Laminar shear stress (6–15 dyn/cm²) | TSP-1↓ | Shear stress downregulates TSP-1/CD36, reducing EC apoptosis and promoting vascular homeostasis | [56, 57] |

| Atherosclerosis | Endothelial cells (ECs) | Disturbed flow (low/oscillatory shear) | TSP-1↑ | Upregulated TSP-1 activates TGF-β-dependent fibrotic pathways (COL1A1, CTGF, PAI1↑) | [46] |

| Pulmonary hypertension (PH) | Pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs) | Tensile force | TSP-1↑ | Inhibiting PAEC proliferation via CD36/CD47 binding | [27] |

| Vascular remodeling | Vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) | Cyclic tensile stress | TSP-1↑ | Stabilizing F-actin complexes, enhancing cellular rigidity, and inhibiting SMC proliferation | [61] |

| Diabetic/ Hypertensive myopathy | Myocardial tissue | Pressure overload | TSP-1↑ | Promoting myocardial fibrosis via TGF-β activation and exacerbating injury | [47] |

| Pulmonary vascular remodeling | Pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) | Pathological pressure | TSP-1↑ | Enhancing ER stress via JAK2-STAT3-TSP-1, driving PASMC proliferation/migration | [69] |

| Aortic pressure overload | Aortic vasculature | Transverse aortic constriction (TAC) | TSP-2↑ | Preserving vascular structural integrity; deficiency causes medial-adventitial separation | [70] |

| Cardiac hypertrophy | Myocardium | Pressure overload | TSP-4↑ | Mitigating cardiomyocyte injury/fibrosis by modulating ER stress responses | [71, 35] |

| Right ventricular pressure overload | Right ventricular cardiomyocytes | Pressure overload | TSP-4↑ | Suppressing hypertrophy/fibrosis via JNK/Runx2 signaling | [72] |

Expression of TSPs in response to diverse mechanical stimuli and their mechanoregulatory roles in the cardiovascular system

Shear stress

Under physiological shear stress, the dynamic regulation of TSP-1 expression (downregulation and upregulation) acts as a spatiotemporal molecular switch that maintains vascular homeostasis and controls vascular regeneration and repair. As mentioned earlier, shear stress plays a crucial role in maintaining cardiovascular system homeostasis under physiological conditions. Physiological shear stress activates vascular endothelial cell function, promotes vasodilation, and inhibits platelet aggregation. Moreover, physiological shear stress inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation, which are essential for the maintenance of vascular wall stability. Research has indicated that the role of TSP-1 in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis under physiological conditions primarily involves blood pressure regulation, vascular tone balance, platelet function modulation, and thrombus prevention. In addition, TSP-1 responds to physiological shear stress and is downregulated, contributing to physiological homeostasis maintenance and vascular remodeling. Experiments simulating physiological laminar shear stress revealed that shear stress (6 dyn/cm² for 24 h) significantly downregulated the expression of TSP-1 and its receptor CD36 in endothelial cells (ECs) in a force- and time-dependent manner. This downregulation persisted for at least 72 h, and TSP-1 and CD36 expression was reversible upon the restoration of no-flow conditions. In addition, TSP-1/CD36 binding can induce endothelial cell apoptosis. Besides, physiological shear stress inhibits TSP-1/CD36 function, thereby suppressing endothelial cell apoptosis and promoting endothelial stability and vascular homeostasis [56]. Concurrently, studies have shown that laminar shear stress (15 dyn/cm²) suppresses TSP-1 expression in endothelial cells, thereby increasing the proliferation, adhesion, migration, and reendothelialization of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), ultimately mediating vascular repair [57]. Furthermore, under normal physiological shear stress, downregulation of TSP-1 expression does not affect NO-mediated vasodilation. Conversely, intravenous injection of TSP-1 or a CD47 agonist antibody acutely increases blood pressure [58]. In the blood flow environment, TSP-1 competitively interferes with ADAMTS13 enzyme activity via its TSR1/TSR2 domains, reducing vWF multimer cleavage and enhancing stable platelet adhesion, thereby promoting coagulation or thrombus formation. In addition to these findings, the downregulation of TSP-1 expression under normal shear stress inhibits platelet adhesion and aggregation, maintaining the normal physiological state of blood vessels [59].

In contrast to its downregulation under laminar shear stress, TSP-1 expression is aberrantly upregulated in response to pathological shear stress, exerting detrimental regulatory effects on cardiovascular tissues by promoting endothelial dysfunction and impairing angiogenesis. Under d-flow, which is characterized by low/oscillatory shear stress at arterial bifurcations or bends, TSP-1 mechanosensitivity is pathologically amplified in regions of d-flow. This subsequently leads to the activation of TGF-β-dependent fibrotic pathways, resulting in the upregulation of collagen type I alpha 1 (COL1A1), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI1), ultimately driving collagen deposition and atherosclerosis [46]. Given the biphasic expression of TSP-1 (suppressed by laminar shear stress vs. amplified by d-flow) in the cardiovascular system, future investigations are warranted to explore the corresponding functions. The therapeutic potential of targeting TSP-1 for the development of lesion stage-specific interventions deserves further study for the treatment of thrombosis and vascular sclerosis diseases.

Tensile force

Tension is a force perpendicular to the vascular axis and is primarily generated by vessel expansion resulting from cardiac pulsation. Under tensile stress in the physiological state, TSP-1 expression levels are low [60], which is consistent with previous descriptions, and TSP-1 functions mainly to maintain the normal state of the cardiovascular system. Furthermore, studies have shown that under cyclic tensile stress, TSP-1 influences the alignment orientation and stiffness of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs), directly regulating vascular wall remodeling. Under physiological tensile stress, TSP-1 also maintains vascular homeostasis by regulating downstream signaling pathways. Y. Yamashiro et al. studied vascular remodeling and the maintenance of vascular homeostasis and reported that TSP-1 expression in SMCs increased in response to cyclic tensile stress [61]. Following simulated physiological cyclic stretch, TSP-1 translocates from the perinuclear region to the cell membrane. TSP-1 colocalizes with the focal adhesion protein p-paxillin, suggesting its involvement in focal adhesion formation. TSP-1 also directly binds to integrin αvβ1 under cyclic stretch conditions, promoting the formation of mature focal adhesions (FAs). In addition, TSP-1 enhances the maturation of the FA-actin complex via integrin αvβ1, increasing cell stiffness and helping cells correctly respond to mechanical stimuli. Knocking out Thbs1 in cells under cyclic stretch affects vascular SMC stiffness, cell alignment orientation, and focal adhesion maturation. Simultaneously, under tensile stress, TSP-1 regulates the nuclear translocation of YAP via integrin αvβ1, activating the expression of YAP target genes, including CTGF, Serpine1, cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61), and Caveolin-3, which participate in vascular wall remodeling. Because YAP plays an important role in vascular wall remodeling, loss of Thbs1 leads to the inhibition of the YAP signaling pathway, thus affecting adaptive remodeling of the vascular wall [61].

Tension induces TSP-1 expression in pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs), where TSP-1 significantly inhibits PAEC proliferation by binding to CD36 and CD47 [27]. However, in this study, the authors did not investigate the downstream signaling pathways following TSP-1 binding to CD36 and CD47. Further research revealed that, via specific sequences, TSP-1 directly binds to CD36 and CD47, primarily exerting antiangiogenic and proapoptotic effects. TSP-1 binds to the conserved CLESH domain of CD36 via its TSR-1 [62]. This binding activates the kinase domain of CD36, leading to the activation of Fyn kinase (a Src family kinase) and the initiation of downstream signaling cascades [63]. The TSP-1/CD36 complex then recruits Src homology 2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase (SHP)-1 to the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) signaling complex, thereby attenuating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling. Ultimately, this cascade induces the apoptosis and antiangiogenic effects of microvascular endothelial cells [64]. TSP-1 binds CD47 via the VVM sequence within its C-terminal domain (4N1K peptide), which subsequently inhibits the NO-cGMP pathway [65]. The TSP-1/CD47 interaction also suppresses cGMP generation, consequently reducing cAMP levels. This impairs vasodilation, potentially contributing to hypertension or pulmonary hypertension, and may promote thrombosis and vascular dysfunction [66]. Furthermore, TSP-1/CD47 binding disrupts the interaction between CD47 and VEGFR2, inhibiting VEGFR2 signaling [67]. This interaction also inhibits Akt-mediated eNOS phosphorylation and calcium signaling, thereby reducing endothelial nitric oxide (NO) production and suppressing angiogenesis [65]. A previous study also suggested that TSP-1 binding to both CD36 and CD47 may have synergistic effects, as CD36 and CD47 cooperatively regulate VEGFR2 phosphorylation, inhibit the Akt pathway, and promote cell apoptosis [68]. Whether the interaction of TSP-1 with CD36 and CD47 exerts regulatory effects through the aforementioned signaling network in vascular endothelial cells and VSMCs under tensile force warrants further investigation.

In vivo mechanical stimuli in the cardiovascular system

In addition to the well-characterized mechanical stimuli in vitro, emerging evidence from in vivo cardiovascular biomechanics research highlights that TSPs exhibit dynamic responses to spatiotemporally heterogeneous mechanical cues under pathophysiological conditions. Short-term elevation of TSPs plays a critical role in cardiovascular remodeling. For example, under physiological stress, such as exercise, a delayed increase in TSP-1 expression results in the formation of a feedback loop with VEGF, preventing excessive angiogenesis [60]. Given this long-term persistence in pathological mechanical microenvironments, the sustained high expression of TSP-1 promotes pathological tissue remodeling. In diabetic and hypertensive murine models, TSP-1 expression is markedly increased, which then promotes myocardial fibrosis by activating the TGF-β signaling pathway and exacerbating myocardial injury [47]. In pulmonary hypertension (PH) models, the upregulation of TSP-1 expression enhances endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress through the JAK2-STAT3-TSP-1 pathway, driving pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell (PASMC) proliferation and migration and accelerating pulmonary vascular remodeling, thereby promoting PH progression [69]. These findings emphasize that TSP-1 in long-term pathological mechanical microenvironments exacerbates the progression of cardiovascular diseases.

In contrast to TSP-1, TSP-2 and TSP-4 play protective roles in cardiovascular tissues under pressure overload. In transverse aortic constriction (TAC) models, TSP-2 expression is elevated upon aortic pressure overload, where it preserves vascular structural integrity. In contrast, TSP-2 deficiency leads to aortic medial‒adventitial separation and reduced vascular resistance to pressure [70]. Similarly, TSP-4 expression was upregulated in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy models. By modulating ER stress responses, TSP-4 mitigates cardiomyocyte injury and fibrosis, conferring protection against cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure [71]. In myocardial pressure overload models, TSP-4 upregulation is correlated with reduced hypertrophy, fibrosis, and vascular rarefaction, whereas its absence exacerbates fibrotic remodeling, highlighting its protective role in myocardial adaptation [35]. TSP-4 also protects the right ventricle under pressure overload by suppressing cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and fibrosis via the JNK/Runx2 signaling pathway [72]. Overall, pathological pressure overload often upregulates the expression of TSPs. Notably, TSP-2 and TSP-4 exert structural preservation effects, whereas TSP-1 predominantly promotes pathological progression.

Notably, in cardiovascular tissues under pressure overload, TSP-2/-4 exert structural preservation effects, whereas TSP-1 predominantly promotes pathological progression. Structurally, the most significant difference between TSP-1 and other TSP family proteins lies in its TSR domain, which contains a unique sequence (the KRFK sequence, a distinctive structural feature specific to TSP-1) capable of binding and activating TGF-β [45]. Furthermore, considering that under pressure overload, TSP-1 primarily influences myocardial fibrosis and that TGF-β activation plays a significant role in cellular fibrosis, we hypothesize that the functional divergence between TSP-1 and TSP-2/-4 may center on their roles in TGF-β activation. Specifically, under pressure overload, TSP-1 promotes myocardial fibrosis by activating TGF-β. Conversely, TSP-2, the closest structural homolog to TSP-1, lacks the KRFK sequence. However, its TSR domains contain the GGWSHW motif, which binds to TGF-β. Via this motif, TSP-2 competitively inhibits TSP-1 binding, thereby suppressing TGF-β activation and tissue fibrosis [73]. Similarly, TSP-4 lacks the KRFK sequence. Its mechanism for regulating collagen is independent of TGF-β activation and involves direct inhibition of fibroblast collagen synthesis [35]. We therefore hypothesize that under pressure overload, TGF-β activation by the KRFK sequence in TSP-1 plays a crucial role in promoting myocardial fibrosis. Consequently, targeted antagonism of the key peptide in TSP-1 that is responsible for TGF-β activation may represent a therapeutic strategy to prevent excessive myocardial fibrosis in a pressure overload model. A previous study used a conserved sequence (LSKL) to competitively bind and activate TGF-β, counteracting the KRFK sequence of TSP-1 in diabetic-hypertensive myocardial fibrosis [74]. This approach reduced myocardial collagen deposition and improved ventricular diastolic function in a diabetic-hypertensive rat model [47]. These findings suggest that therapeutic strategies targeting TSPs should be both isoform and context specific. However, the precise therapeutic efficacy requires further validation.

Mechanical Stimuli-Dependent TSP signaling in cardiovascular remodeling

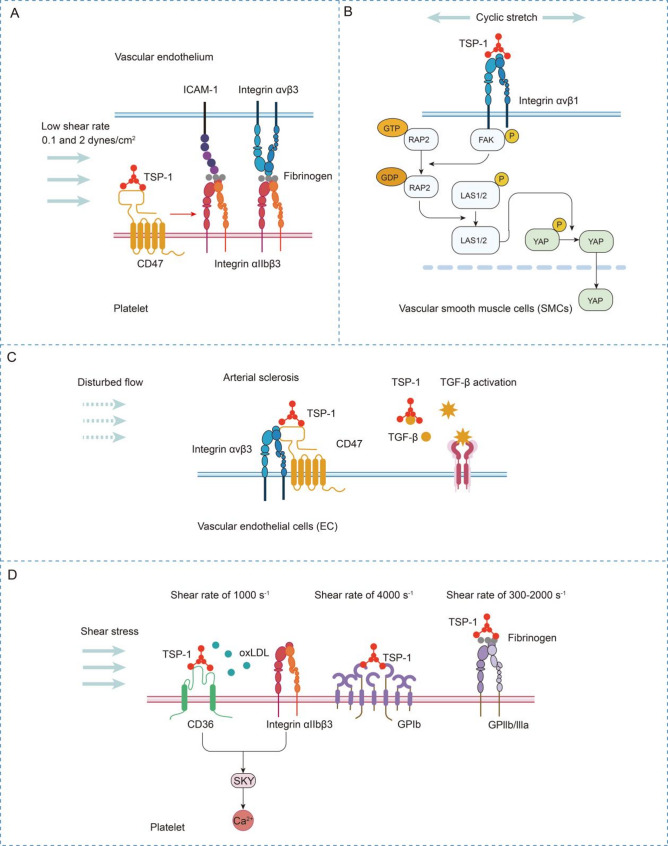

Emerging evidence from biomechanical studies underscores the pivotal role of TSPs in orchestrating cardiovascular biomechanical adaptation and disease progression under mechanical loading. Critically, the functional realization of TSPs is mechanistically dependent on their context-dependent interactome, particularly ligand‒receptor complexes dynamically assembled at force-sensitive microdomains. Herein, we systematically dissect the mechanoregulatory networks of TSPs through the lens of their binding partners (Fig. 2). Notably, as previously mentioned, the current molecular mechanisms underlying the role of TSPs under mechanical stimulation are focused primarily on TSP-1. Therefore, the following content will concentrate on the mechanisms by which TSP-1 responds to mechanical stimuli in the cardiovascular system.

Fig. 2.

Mechanical stimuli-dependent TSP signaling in cardiovascular remodeling

(A) TSP-1-CD47 binding activates platelet αIIβ3 integrin to mediate endothelial adhesion through fibrinogen bridging with ICAM-1/αvβ3 under shear stress. (B) Cyclic stretch induces TSP-1 secretion in SMCs, which binds αvβ1 integrin to promote FA-actin maturation and YAP nuclear translocation via Rap2/Hippo inactivation. (C) Disturbed flow induces TSP-1/integrin/CD47 complex formation or activates the TSP-1–TGF-β axis, driving collagen deposition and atherosclerotic plaque progression. (D) Shear stress induces TSP-1-mediated platelet aggregation and endothelial adhesion via the CD36/integrin αIIβ3–Syk axis and TSP-1–GPIb/IIbIIIa interactions

Integrins

The integrin superfamily encompasses 24 distinct heterodimeric receptors that demonstrate specialized functional profiles across biological systems [75]. Recent mechanistic investigations have identified approximately five integrin subtypes capable of mediating mechanosensitive interactions with TSPs, particularly under mechanical stress conditions. TSPs exhibit multidomain binding specificity to integrin family members using distinct structural motifs. The N-terminal domain harbors three critical binding sites: the A159ELDVP motif, which mediates α4β1 integrin interaction [76]. the Arg198 residue, which engages α3β1 integrin; and the Glu90 site, which selectively recognizes α6β1 integrin [77]. The TSR domain has β1 integrin-binding activity [78], whereas the signature domain contains a conserved RGD sequence capable of dual recognition of αvβ3 [79] and αIIbβ3 [80] integrins. These interactions are mechanoresponsive and collectively regulate platelet adhesion, atherothrombosis, and vascular remodeling.

As described earlier, the regulation of the cardiovascular system by TSPs under mechanical stimulation involves both physiological remodeling and pathological reconstruction. During the process of physiological remodeling, cyclic stretching mediates vascular remodeling. Yoshito Yamashiroa et al. reported that cyclic stretch induced TSP-1 secretion in SMCs. Secreted TSP-1 binds to integrin αvβ1 and aids in the maturation of the FA-actin complex, thereby mediating the nuclear shuttling of YAP via inactivation of Rap2 and the Hippo pathway [25] (Fig. 2B). Within an organism, the Thbs1/integrin/YAP signaling pathway may facilitate the maturation of focal adhesions (FAs) following pressure overload induced by transverse aortic constriction (TAC), thereby safeguarding the aortic wall. Conversely, when blood flow is halted due to carotid artery ligation, this signaling pathway results in the formation of the neointima (NI) [25].

In the process of pathological remodeling, TSP-1-mediated α4β1 integrin activation promotes sickle erythrocyte‒endothelium adhesion under flow, contributing to vaso-occlusive pathology [81]. Under high shear stress, TSP-1 binds αIIbβ3 integrin to potentiate platelet cohesion while antagonizing NO-mediated antithrombotic effects, particularly in stenotic vessels [28]. Dual engagement of αIIbβ3 integrin and GPIb by TSP-1 coordinates platelet adhesion‒aggregation cascades, establishing a prothrombotic microenvironment in atherosclerotic plaques [49]. Turbulent flow induces TSP-1/integrin αvβ3-IAP complex formation, triggering caspase-dependent endothelial cell death, which ultimately leads to the development of atherosclerosis [50] (Fig. 2C). A review of the literature revealed that, under pathological mechanical stimulation, the interaction between TSP-1 and integrins is often mediated by the regulation of abnormal platelet adhesion to form thrombi or endothelial cell death that triggers atherosclerosis.

CD36

CD36, a multifunctional transmembrane glycoprotein, engages TSPs through the evolutionarily conserved TSR. Structural analysis revealed that within the Type 1 repeats of TSP-1, particularly in the TSR2 domain, a conserved KRFK motif (amino acid sequence: KRFKQDGGWSHWSPWSS) is found that serves as a critical binding site for CD36 [82]. A previous study revealed that TSP-1 and CD36 exhibit biphasic expression patterns under various shear stress gradients, transitioning from transcriptional suppression to pronounced upregulation. This mechanical decoding mechanism drives a functional conversion from proangiogenic effects at low expression levels to potent angiogenesis inhibition upon high expression. Notably, their shear-dependent transcriptional reprogramming demonstrates threshold-sensitive characteristics, suggesting their potential as mechanochemical switches in vascular homeostasis.

Under physiological conditions, shear stress downregulates TSP-1 and CD36 expression in endothelial cells. The interaction between TSP-1 and CD36 inhibits angiogenesis in vitro, while blocking TSP-1 and CD36 accelerates angiogenesis [83]. The downregulation of TSP-1 and CD36 is related to the strength and duration of shear stress. More importantly, TSP-1 and CD36 downregulation is reversible after restoring no-flow conditions [56]. In the process of pathological remodeling, TSP-1 and CD36 function to modulate the cytoadhesion of P. falciparum-infected red blood cells (PfRBC) to the vascular endothelium during malaria pathogenesis. Single-molecule force spectroscopy revealed that CD36–IRBC interactions exhibit greater mechanical stability compared with TSP-1-mediated binding; however, TSP-1 demonstrates superior binding strength under high loading rates, mimicking rapid blood flow. These findings suggest a two-step adhesion mechanism in which TSP-1 initiates the capture of circulating IRBCs, whereas CD36 serves as a stabilizing anchor [84, 85]. Under shear stress, TSP-1 promotes platelet aggregation and endothelial cell adhesion, thereby driving thrombus formation through interactions with multiple cell surface receptors, including the TSP-1/CD36/ integrin αIIβ3–Syk signaling axis [29] (Fig. 2D), which initiates platelet activation and mediates arterial thrombus progression. In summary, under pathological mechanical stimulation, the interaction between TSP-1 and CD36 mainly contributes to abnormal platelet adhesion, which acts as a key factor in facilitating thrombosis.

CD47

The CD47-binding site on TSP-1 has been mapped to the peptide sequence of R1034FYVVM, which is located within the lectin-like module of the calcium-replete structure. Notably, in sickle cell disease, CD47 activation promotes erythrocyte adhesion to TSP-1, VCAM-1, and fibronectin under shear stress [81]. In mediating platelet adhesion to vascular endothelial cells under shear stress, TSP-1–CD47 binding in platelets activates αIIβ3 integrin, which bridges endothelial ICAM-1/integrin αvβ3 via fibrinogen to mediate platelet–endothelial adhesion (Fig. 2A). In arterial sclerosis induced by disturbed flow, biomechanical forces trigger the formation of the TSP-1/integrin/CD47 complex. This drives endothelial apoptosis and initiates atherogenic plaque development, thereby establishing a critical link between hemodynamic stress and early atherosclerosis progression [50].

TGF-β

The TSR2 domain of TSP-1 contains two critical motifs, WSHWSPW and RFK, that mediate the binding and activation of latent TGF-β [21]. As described in the pathological role of TSP-1 and the protective roles of TSP-2 and TSP-4, the TSR domain of TSP-1 contains a unique sequence, KRFK, which plays a crucial role in TGF-β activation. The KRFK motif in the TSP-1 TSR domain binds to the LSKL sequence within the latency-associated peptide (LAP) of the TGF-β procomplex [45, 86, 87]. TSP-1 then induces a conformational change in LAP. Specifically, its AAWSHV domain binds LAP, whereas its KRKK motif disrupts the LAP structure, leading to the release of mature TGF-β [87]. During the pathological progression of heart disease, d-flow increases TSP-1 expression, subsequently activating TGF-β. TGF-β then promotes collagen gene expression and exacerbates atherosclerosis. The TSP-1–TGF-β axis in vascular endothelial cells drives collagen deposition and atheroma formation, mechanistically linking hemodynamic perturbations to ECM remodeling and atherosclerotic plaque progression [46] (Fig. 2C). Similarly, in the context of cardiac remodeling induced by pressure overload, TSP-1 activates the TGF-β pathway and enhances matrix retention to prevent ventricular dilation [88]. During cardiac remodeling, pressure overload together with elevated Angiotensin II (Ang II) increases TSP-1 expression to facilitate TGF-β activation. TGF-β signaling subsequently drives fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition, leading to fibrosis [47]. Consequently, in both atherosclerosis and cardiac remodeling, TSP-1-mediated TGF-β activation likely contributes to excessive fibrosis within cardiovascular tissues, ultimately impairing cardiovascular function.

Calcium

Calcium ions play a pivotal role in modulating the conformational dynamics of TSPs. In the presence of calcium, TSP domains adopt a compact conformation, whereas calcium depletion induces domain unfolding and contraction of the C-terminal globular domain. These conformational changes significantly influence the binding affinity of TSPs for their interacting partners and directly modulate TSP functionality [89]. Structurally, all TSP family members (TSP-1 to TSP-5) contain Type III repeats, which serve as the direct Ca²+-binding domain [37]. These repeats form EF-hand-like calcium-binding motifs, chelating Ca²+ via carboxylate side chains of Asp/Glu residues [37]. Studies have demonstrated that Ca²+ acts as a central scaffold for the tertiary structure of the Type III repeats region. Lacking a significant secondary structure, the folding of Type III repeats depends entirely on Ca²+-mediated polypeptide chain wrapping. In the calcium-saturated state, Type III repeats and the C-terminal domain (CTD) adopt a compact assembly. Conversely, Ca²+ removal (e.g., by EDTA treatment) unfolds Type III repeats into random coils, elongating the C-terminal “arms” and collapsing the globular structure. Calcium-induced structural alterations modulate the interactions of TSPs with partner proteins. For example, TSP-1 harbors an integrin-binding RGD motif (Arg908-Gly909-Asp910) within Type III repeats. Under Ca²+ saturation, RGD embeds into an N-type calcium-binding loop, where the Arg908 backbone carbonyl coordinates Ca²+, sterically hindering integrin recognition. Low-calcium conditions lead to the exposure of this integrin-binding site [51]. Owing to this mechanism, the cellular Ca²+ loading status dictates RGD-dependent cell adhesion.

In addition to Type III repeats, the EGF-like domain also contains Ca²⁺-binding sites. Fluorescence quenching assays revealed that Ca²⁺ induces distinct conformational changes across TSP subfamilies [90]. The N700S mutation in TSP-1 reduces Ca²⁺ binding, destabilizes protein structure, and increases prothrombotic activity. The A387P mutation in TSP-4 enhances Ca²⁺ binding, suppresses endothelial cell adhesion and proliferation, and induces vascular dysfunction [3]. These findings establish Ca²⁺ as a core regulator of TSP structure and function, where single-amino acid mutations perturb local Ca²⁺ sites, triggering global conformational shifts and pathological consequences [90]. In cardiovascular systems, mechanical stimuli (e.g., shear stress and tensile force) mediate extracellular Ca²⁺ influx in endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts, contributing to disease progression. Nevertheless, the direct regulation of TSPs by Ca²⁺ in cardiovascular pathogenesis remains inadequately explored and requires further investigation.

Other related pathways

Under shear stress, TSP-1 promotes platelet aggregation and endothelial cell adhesion, thereby driving thrombus formation through interactions with multiple cell surface receptors, including the TSP-1/GPIIbIIIa complex [91] and the TSP-1/GPIb interaction [49], which initiates platelet activation and mediates arterial thrombus progression (Fig. 2D).

TSPs as central mediators in mechanically induced musculoskeletal remodeling

The musculoskeletal system integrates muscles, bones, and cartilage tissues to coordinate bodily movement and maintain structural integrity [92]. Muscles generate contractile forces to induce skeletal motion, whereas their mechanical stimulation mainly regulates bone development. The skeletal system serves as the primary load-bearing framework, dynamically adapting to mechanical stresses through mechanisms described by Wolff’s law [93]. Abnormal loading patterns may result in pathological conditions, including osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. In addition, articular cartilage primarily serves to absorb mechanical stress and minimize joint pressure and friction, with its viscoelastic properties enabling effective dynamic force distribution. TSPs function mainly to regulate muscle mechanical adaptation, osteochondral development, and osteoarthritis pathogenesis under biomechanical stimuli (Table 2).

Table 2.

The expression and functional profiles of TSPs across musculoskeletal tissues under varied mechanical loading conditions

| Physiological/Pathological States | Expression Tissue/Cell Type | Mechanical Stimulus | Name of TSPs | TSPs Function | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle hypertrophy | Interstitial mesenchymal progenitor cells | Mechanical loading | TSP-1↑ | Driving muscle stem cell (MuSC) proliferation. | [94] |

| Bone formation & remodeling | Periosteal CD68 + F4/80- myeloid cells | Piezo1-mediated mechanical sensing | TSP-1↑ | Promoting osteoprogenitor recruitment and periosteal bone formation. | [95] |

| Stem cell chondrogenesis | Stem cells | Pressure | TSP-2↑ | Enhancing chondrogenesis via NF-κB signaling activation. | [17] |

| Osteoarthritis progression | Knee cartilage | Mechanical overloading (knee varus) | TSP-1↑ | Reduced expression correlates with cartilage degeneration and disease progression. | [98] |

Expression of TSPs in response to diverse mechanical stimuli and their mechanoregulatory roles in the musculoskeletal system

Muscle

Study has demonstrated that TSPs can modulate mechanoadaptive responses and maintain tissue homeostasis. In a murine muscle hypertrophy model, Kaneshige et al. demonstrated that interstitial mesenchymal progenitor cells respond to mechanical loading by facilitating muscle stem cell proliferation [94]. Mechanistically, the transcriptional activation of Yap1 and Taz in these progenitor cells induces local TSP-1 production, which subsequently drives MuSC proliferation via CD47 signaling. These findings establish the Yap1/Taz–TSP-1–CD47 axis as an essential pathway for maintaining the MuSC supply during mechanical overload-induced muscle hypertrophy.

Bone

Similarly, mechanical forces also work to regulate TSP expression in osteogenic contexts, exerting profound effects on bone dynamics. Deng et al. reported that Piezo1-mediated mechanical sensing induces the differentiation of periosteal CD68 + F4/80- myeloid cells into CD68 + F4/80 + macrophages, which activate TGF-β1 through TSP-1 secretion, ultimately promoting osteoprogenitor recruitment and periosteal bone formation [95]. Notably, TSP-2 deficiency results in aberrant cortical bone remodeling. Although TSP-2-null mice exhibit elevated mechanical strain on the outer cortical surface, the paradoxical enhancement of bone formation occurs specifically on the inner surface without compensatory changes in strained outer regions [96]. This uncoupling between mechanical strain and bone formation suggests that TSP-2 orchestrates load-induced osteogenic patterns.

Cartilage

In addition to that described above, mechanical stimuli also modulate TSPs in chondrogenic contexts. Our prior work demonstrated that physiological pressure enhances stem cell chondrogenesis concomitant with TSP-2 upregulation, which activates nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) signaling [17]. In the process of the cartilage mechanoresponse, Orazizadeh et al. demonstrated that CD47/IAP (integrin-associated protein) serves as a mechanotransduction hub in chondrocytes. Mechanistic analyses revealed that CD47/IAP coordinates with α5β1 integrin and TSP-1 to regulate cellular perception and adaptation to biomechanical stimuli. Following mechanical compression stimulation in chondrocytes, upregulated CD47/IAP was observed. Notably, coimmunoprecipitation assays confirmed the formation of molecular complexes between CD47/IAP and α5β1 integrin/TSP-1, which subsequently triggered membrane depolarization and initiated downstream mechanotransduction pathways [97]. Similarly, in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis (OA), mechanical overloading in knee varus reduces TSP-1 expression, which is correlated with osteoarthritis progression [98].

Collectively, these studies establish TSPs as mechanosensitive regulators orchestrating musculoskeletal development and maintaining tissue homeostasis. Notably, supraphysiologic mechanical overload induces pathological TSP downregulation, culminating in musculoskeletal disorders. These mechanoresponsive adaptations provide critical insights for regenerative medicine strategies, particularly in designing biomechanically informed tissue grafts and developing therapeutics for skeletal pathologies. Nevertheless, musculoskeletal mechanobiology encompasses diverse force modalities, including compression, tension, and hydrostatic pressure, each of which imposes distinct biophysical constraints. Nevertheless, the isoform-specific responses of TSPs to defined mechanical cues (e.g., strain magnitude/frequency) remain understudied in musculoskeletal contexts.

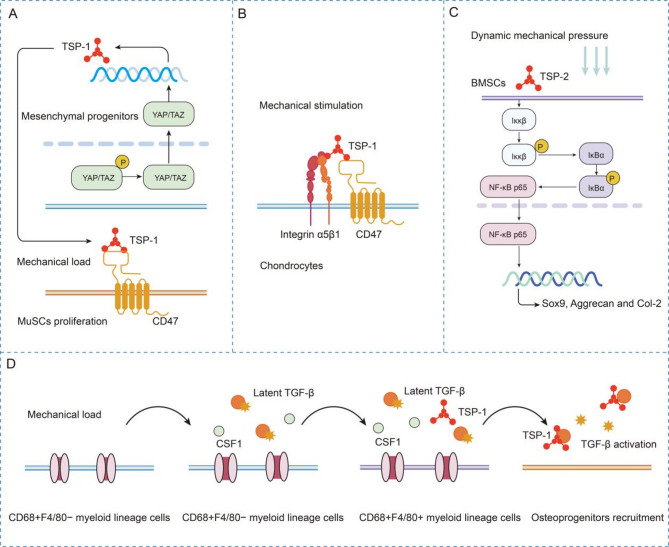

Mechanical stimuli-dependent TSP signaling in musculoskeletal remodeling

CD47

As previously established, TSP-1 functions as a pivotal mediator of signal transduction between mesenchymal progenitors and MuSCs, ensuring their adaptive responsiveness to elevated mechanical loading. In skeletal muscles, the Yap1/Taz–Thbs1–CD47 axis facilitates mechanical adaptation. Increased mechanical loading induces TSP-1 expression in mesenchymal progenitors through YAP/TAZ nuclear translocation. TSP-1 subsequently promotes MuSC proliferation and fusion via CD47 binding, ultimately leading to muscle hypertrophy [94] (Fig. 3A). These findings suggest that targeting the Yap1/Taz–Thbs1–CD47 axis may artificially activate MuSC proliferation and increase the myonuclear supply, thus reversing muscle loss. This mechanism represents a therapeutic target for sarcopenia and muscle atrophy. Furthermore, within cartilage tissue, TSP-1 performs chondroprotective mechanotransduction functions through its strategic binding to CD47, a critical mechanoreceptor that coordinates extracellular matrix adaptation. CD47/IAP may impact the mechanotransduction process of chondrocytes through its interactions with TSP-1 and α5β1 integrin, triggering membrane depolarization and thereby modulating the response of cartilage to mechanical stimuli [97] (Fig. 3B). Pharmacological activation of the CD47/TSP-1 axis may reverse pathological phenotypes in OA chondrocytes by reprogramming catabolic mechanical signals into anabolic outputs, thus inhibiting OA progression.

Fig. 3.

Mechanical stimuli-dependent TSPs signaling in musculoskeletal remodeling

(A) Mechanical loading activates the YAP/TAZ–TSP-1 axis in mesenchymal progenitors, driving CD47-mediated MuSC proliferation and fusion to promote muscle hypertrophy. (B) TSP-1 mediates mechanical responses via CD47/integrin α5β1 interactions in cartilage. (C) Pressure upregulates TSP-2 in BMSCs to synergistically activate the NF-κB pathway, driving chondrogenesis. (D) Mechanical loading activates periosteal myeloid cells, driving TSP-1 expression, which triggers TGF-β1-dependent osteoprogenitor recruitment

TGF-β

Mechanical loading induces TSP-1-mediated activation of TGF-β signaling cascades, which critically regulate transcriptional programming during osteogenic differentiation. As mechanistically described in the preceding sections, mechanical loading promotes periosteal bone formation through TSP-1-dependent TGF-β1 activation. As noted earlier, Deng et al. demonstrated that mechanical loading promotes periosteal bone formation through TSP-1-mediated TGF-β1 binding and activation. However, this process involves multiple cellular components. First, CD68⁺F4/80⁻ myeloid cells sense mechanical loading via Piezo1 activation, triggering Ca²⁺ influx and upregulating Csf1, which drives their differentiation into CD68⁺F4/80⁺ macrophages. CD68⁺F4/80⁺ macrophages secrete TSP-1, the KRFK motif of which binds the LSKL sequence in the LAP of TGF-β1, thereby releasing active TGF-β1. Second, active TGF-β1 recruits Osterix⁺ (Osx⁺) osteoprogenitors to the periosteal surface via the pSmad2/3 signaling pathway, ultimately driving cortical bone formation. Third, mechanical loading-induced cortical bone formation converges on TSP-1-dependent TGF-β1 activation, and this process involves cells such as macrophages and osteoprogenitors and multiple signaling pathways (including the Piezo1, TSP-1/TGF-β1, and TGF-β1–pSmad2/3 pathways) [95]. These findings collectively indicate that the mechanical regulation of bone formation by TSP-1 operates within a precise signaling network. Elucidating this network, particularly how mechanical stimuli activate TGF-β1 via macrophages, may inform therapeutic strategies for osteoporosis and fracture repair (Fig. 3D).

Other related pathways

During chondrogenesis, mechanical pressure enhances TSP-2 expression in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), which then promotes chondrogenic differentiation through the NF-κB signaling pathway [17]. This study demonstrated that mechanical pressure synergizes with TSP-2 to activate the canonical NF-κB pathway in BMSCs. Mechanistically, TSP-2 potentiates mechanical stress-induced IKKβ phosphorylation, which subsequently triggers IκBα ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This cascade liberates NF-κB p65 subunits for nuclear translocation, driving the transcriptional reprogramming essential for BMSC chondrogenesis. Critically, NF-κB activation serves as a central node mediating the prochondrogenic synergy between biomechanical cues and TSP-2 [17] (Fig. 3C). The TSP-2/NF-κB axis may serve as a target for engineered cartilage construction and regenerative therapies.

Matrix stiffness-mediated TSP upregulation in fibrotic remodeling and tumor progression

As a critical biomechanical cue, substrate stiffness serves as a pivotal mechanical instruction that governs cellular differentiation by modulating the mechanosensitive microenvironment, thereby directly or indirectly dictating cellular fate determination. Notably, evidence has demonstrated that tissue stiffening triggers significant upregulation of TSPs, which orchestrate tissue remodeling through downstream signaling pathways.

Matrix stiffness regulates TSP expression in fibrotic tissues

In general, the stiffness of the ECM can modulate the expression and function of TSPs. Islam et al. investigated the mechanoregulatory role of substrate stiffness in BMSC differentiation and ECM production and reported that highly anisotropic substrates significantly enhanced Col1a2, Col3a1, and TSP4 synthesis through stiffness-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization [99]. In addition to their role in cellular-scale mechanotransduction, accumulating evidence positions TSPs as mechanoresponsive biomarkers of tissue fibrosis. Moreover, existing clinical studies have also consistently reported that TSP upregulation in fibrotic pathologies across multiple organ systems is correlated with ECM crosslinking density and disease progression [100, 101, 102, 103, 104].

During hepatic fibrosis progression, serum TSP-2 concentrations dynamically track liver stiffness progression and have emerged as a stage-specific diagnostic biomarker for noninvasive stratification of fibrosis severity in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients [100]. Longitudinal analyses further established circulating TSP-2 levels as an independent predictor of advanced fibrosis (≥ F3) development in patients with T2DM and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and these levels exhibited robust prognostic value even after adjustment for conventional risk factors (BMI, platelet count, and hepatic steatosis index) [101]. In fibrotic lesions in diabetic tissues, TSP-2 mediates fibroblast dysfunction through dysregulation of cytoskeletal dynamics and ECM crosslinking [104]. In addition to its role in hepatic fibrosis, TSP-1 presents a distinct pathognomonic feature in stiff skin syndrome (SSS), where its overexpression drives dermal fibrosis through inflammation-independent mechanotransduction pathways. Histopathological and molecular profiling of SSS lesions revealed coordinated upregulation of TSP-1, Col1a2, and fibronectin-1 within the fibrotic dermal compartment, implicating TSP-1 as a central effector in dysregulated ECM deposition [102]. Moreover, TSP-1 is likely a key player in autocrine TGF-β signaling and the accumulation of ECM in scleroderma fibroblasts [103]. These findings suggest that TSPs may serve as mechanoresponsive biomarkers of tissue fibrosis and have the potential to be developed as drug targets (Table 3).

Table 3.

The expression and pathobiological functions of TSPs in fibrotic and neoplastic tissues modulated by matrix stiffness

| Pathological States | Expression Tissue/Cell Type | Mechanical Stimulus | Name of TSPs | TSPs Function | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic fibrosis | Serum (T2DM cohorts) | Liver stiffness progression | TSP-2↑ | Serving as a stage-specific diagnostic biomarker of fibrotic severity | [100] |

| Hepatic fibrosis | Serum | Liver stiffness progression | TSP-2↑ | Independent predictor of advanced fibrosis (≥ F3) development | [101] |

| Hepatic fibrosis | Diabetic fibrotic lesions fibroblasts | ECM crosslinking dysregulation | TSP-2↑ | Mediating fibroblast dysfunction via cytoskeletal dynamics dysregulation | [104] |

| Stiff skin syndrome (SSS) | Dermal fibrotic compartment | Dermal matrix stiffening | TSP-1↑ | Driving inflammation-independent dermal fibrosis via ECM deposition (Col1a2, fibronectin-1) | [102] |

| Scleroderma | Scleroderma fibroblasts | TSP-1↑ | Promoting ECM accumulation via TGF-β mechanotransduction | [103] | |

| Breast cancer | Tumor microenvironment/exosomes | Matrix stiffening | TSP-1↑ | Enhancing invasiveness via MMP-mediated ECM degradation and FAK-dependent cytoskeletal remodeling | [105] |

| Breast cancer | Tumor microenvironment | Stiffness-tuned exosomal release | TSP-1↑ | Enhancing intercellular communication networks that propagate metastatic phenotypes across rigid tumor niches | [106] |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) | Stiff matrix conditions | TSP-1↑ | Inducing EMT and chemoresistance | [48] |

Matrix stiffness modulates TSP expression in neoplastic tissues

In addition to its role in fibrosis pathogenesis, TSP-1 has also emerged as a mechanoresponsive orchestrator within stiffened tumor microenvironments, driving malignancy through multifaceted regulatory mechanisms. In breast cancer, matrix stiffening induces exosome-derived TSP-1 secretion, which potentiates invasiveness via MMP-mediated ECM degradation and FAK-dependent cytoskeletal remodeling, establishing TSP-1 as a key mechanotransducer of tumor progression [105]. Furthermore, stiffness-tuned exosomal TSP-1 facilitates tunneling nanotube (TNT) formation, thus enhancing intercellular communication networks that propagate metastatic phenotypes across rigid tumor niches [106]. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) exhibit mechanoadapted TSP-1 overexpression under stiff matrix conditions. Paracrine TSP-1 from CAFs activates TGF-β/Smad2/3 and PI3K/AKT signaling in PDAC cells, inducing epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT) and sustaining a feedforward loop via Smad4 loss-mediated TSP-1 amplification, thereby accelerating stromal cooption and chemoresistance [48]. In addition, previous studies have shown that TSPs are involved in the regulation of tumor progression associated with changes in matrix stiffness, whereas tumor progression involves various biomechanical changes, such as angiogenesis under fluid shear stress and tumor cell adhesion, indicating the importance of elucidating the relationships among TSPs, mechanical force, and tumor progression. This section describes the role of TSPs in matrix stiffness changes, whereas the other aspects of tumor formation are not discussed in detail (Table 3).

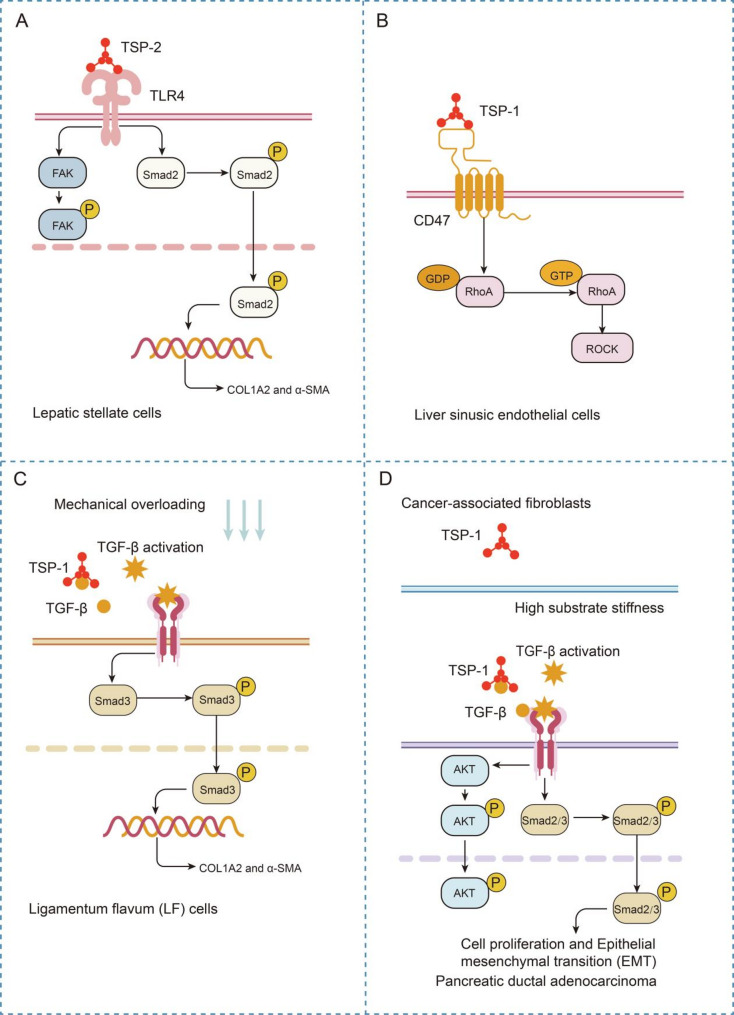

TSP signaling in fibrosis-associated matrix stiffening

In fibrotic tissues and tumors, TSP-1-mediated activation of TGF-β under conditions of altered matrix stiffness plays a critical role in tissue fibrosis and tumor progression. In fibrotic tissues, TSP-1 activates latent TGF-β, initiating a self-reinforcing autocrine loop in scleroderma fibroblasts. Mechanistically, TSP-1 upregulation (posttranscriptional stabilization by TGF-β signaling) drives Smad3 phosphorylation and α2(I) collagen synthesis [103]. In hepatic fibrosis, the extracellular TSP-2 dimer structurally recognizes and directly engages TLR4, triggering downstream profibrotic FAK/TGF-β signaling that activates HSCs, and disruption of this TSP-2-TLR4-FAK/TGF-β axis significantly attenuates both HSC activation and fibrotic progression in liver pathology [32] (Fig. 4A). In addition to liver fibrosis, mechanical stress-induced fibrosis in the spinal ligamentum flavum is similarly mediated by the TGF-β signaling pathway. This study demonstrated that physical pressure upregulated THBS1 expression, which activated the TGF-β1/Smad signaling cascade. This activation subsequently enhances the expression of fibrosis markers, including COL1A2 and α-SMA, ultimately driving ligamentum flavum hypertrophy [107] (Fig. 4C). In addition to affecting the TGF-β-associated pathway, TSP-1 drives the progression of liver fibrosis by activating the Rho-ROCK signaling pathway through its interaction with CD47 (Fig. 4B) [108]. Collectively, these studies suggest that targeting TSPs and their interaction networks (TGF-β/Smad, TLR4/FAK, and CD47/Rho-ROCK) may enable multidimensional intervention in fibrotic progression. These pathways could provide new directions for developing organ-specific antifibrotic drugs, particularly those that exhibit translational potential for refractory fibrotic diseases.

Fig. 4.

TSPs orchestrate mechanosensitive signaling networks in fibrotic and neoplastic microenvironments via matrix stiffness remodeling

(A) The TSP-2 dimer engages TLR4 in hepatic fibrosis to activate profibrotic FAK/TGF-β signaling in HSCs, with axis disruption attenuating fibrotic progression. (B) TSP-1 promotes liver fibrosis via CD47-mediated Rho/ROCK pathway activation. (C) Mechanical stress upregulates TSP-1 in the spinal ligamentum flavum, activating TGF-β1/Smad signaling to increase COL1A2/α-SMA expression and drive hypertrophic fibrosis. (D) Matrix stiffening upregulates CAF-derived TSP-1 in PDAC, activating TGF-β/Smad-Akt signaling to drive tumor proliferation/EMT, whereas TSP-1 silencing attenuates stromal activation and the expression of profibrotic markers

TSP signaling in tumor-driven stromal stiffening

In PDAC, biomechanical analysis revealed that matrix stiffening upregulated TSP-1 in CAFs, whereas TSP-1 silencing attenuated CAF proliferation while downregulating profibrotic signatures (α-SMA and COL1A1) and stromal activation markers (MMP2 and LOXL2) (Fig. 4D). Mechanistically, paracrine TSP-1 initiates a TGF-β/Smad–Akt signaling axis in PDAC cells, as evidenced by phospho-Smad2/3 (Ser465/467) nuclear accumulation and Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation, which collectively drive tumor cell proliferation and EMT [48] (Fig. 4D). These studies demonstrate that matrix stiffening upregulates TSP-1 in CAFs, driving a profibrotic phenotype. Given that TSP-1 serves as a pivotal mechanotransduction regulator, whether targeting TSP-1 and its downstream signaling pathways could achieve therapeutic efficacy warrants further investigation.

Conclusions and future perspectives

The past two decades have witnessed multiple significant advances in mechanobiology, elucidating how mechanical cues regulate cellular behavior through ECM proteins. This review focuses on key mechanosensitive ECM components, namely, TSPs. TSPs orchestrate cellular responses to mechanical forces across diverse physiological and pathological conditions. Through interactions with vital receptors (e.g., integrins, CD36, and CD47) and the modulation of downstream effectors, such as YAP, TGF-β, and Rho kinase, TSPs act as molecular bridges that convert mechanical cues into biochemical signals. These pathways regulate ECM homeostasis, cytoskeletal dynamics, and cell fate decisions, with dual roles in adaptive remodeling, such as muscular hypertrophy and osteogenesis, and maladaptive outcomes (e.g., glaucoma-associated fibrosis or pressure-overloaded aortic remodeling). The context-dependent duality of TSP signaling, exemplified by its prosurvival versus proapoptotic effects in different mechanical milieus, underscores its functional plasticity in tissue adaptation.

Despite these advances, critical questions remain unresolved. First, the structural basis of the mechanosensitivity of TSPs, specifically how mechanical force alters the conformation of TSPs to expose their cryptic domains for receptor binding, requires further structural and biophysical characterization. Second, the crosstalk between TSP-mediated pathways and their spatiotemporal regulation in vivo remain poorly defined. Third, most existing studies have focused on TSP-1, leaving the roles of other TSP family members in mechanotransduction largely unexplored. Additionally, the therapeutic potential of targeting TSPs in mechanical stress-related diseases demands careful evaluation. We hope that this review can provide a new perspective for TSPs and help explain some of the unresolved questions related to the abnormal expression or dysfunction of TSPs, thus contributing to the development of new drugs targeting TSPs for diseases or cancers involved in mechanobiology.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- TSPs

Thrombospondins

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- CTD

C-terminal domain

- vWF-C

Von Willebrand factor type C

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-beta

- FGF2

Fibroblast growth factor 2

- MuSC

Muscle stem cell

- LSS

Low shear stress

- OSS

Oscillatory shear stress

- d-flow

Disturbed flow

- EC

Endothelial cell

- EPC

Endothelial progenitor cell

- COL1A2

Collagen type I alpha 2

- CTGF

Connective tissue growth factor

- PAI1

Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1

- VSMC

Vascular smooth muscle cell

- YAP

Yes-associated protein

- FA

Focal adhesion

- Cyr61

Cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61

- PAEC

Pulmonary artery endothelial cell

- SHP

Src homology 2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase

- VEGFR2

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- NO

Nitric oxide

- PH

Pulmonary hypertension

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- PASMC

Pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell

- TAC

Transverse aortic constriction

- NI

Neointima

- PfRBC

P. falciparum-infected red blood cell

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-B

- LAP

Latency-associated peptide

- BMSC

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- NAFLD

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- SSS

Stiff skin syndrome

- TNT

Tunneling nanotube

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- CAF

Cancer-associated fibroblast

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

Author contributions

Y.Z. drafted the manuscript. S.H. and Z.Y. reviewed and edited the paper. T.L. and L.F. revised the manuscript. X.G. and Y.H. prepared the pictures. All authors have agreed to the submission and publication of this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by funds from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81901052), the General Project of Shaanxi Provincial Key Research and Development Program (2024SF-YBXM-376), Scientific research project of Xi’an Health Commission (2024ms16), the General Project on Medical Research of Xi’an Science and Technology Bureau (24YXYJ0062), and Science and Technology Support Program for Discipline Development of Xi’an People’s Hospital (Xi’an Fourth Hospital) (FZ-81).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhou Yu, Email: yz20080512@163.com.

Sheng Hu, Email: 13720776109@163.com.

References

- 1.Humphrey JD, Dufresne ER, Schwartz MA. Mechanotransduction and extracellular matrix homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(12):802–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D, Brady T, Santhanam L, Gerecht S. The extracellular matrix mechanics in the vasculature. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2023;2(8):718–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long Y, Niu Y, Liang K, Du Y. Mechanical communication in fibrosis progression. Trends Cell Biol. 2022;32(1):70–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanton AE, Tong X, Yang F. Extracellular matrix type modulates mechanotransduction of stem cells. Acta Biomater. 2019;96:310–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Feng Q, Kong W. ECM microenvironment in vascular homeostasis: new targets for atherosclerosis. Physiol (Bethesda). 2024;39(5):0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kjaer M. Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(2):649–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy AM, Iyer R, Chakraborty S. The extracellular matrix in hepatocellular carcinoma: mechanisms and therapeutic vulnerability. Cell Rep Med. 2023;4(9):101170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jansen KA, Atherton P, Ballestrem C. Mechanotransduction at the cell-matrix interface. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;71:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saraswathibhatla A, Indana D, Chaudhuri O. Cell-extracellular matrix mechanotransduction in 3D. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24(7):495–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown BN, Badylak SF. Extracellular matrix as an inductive scaffold for functional tissue reconstruction. Transl Res. 2014;163(4):268–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dey K, Roca E, Ramorino G, Sartore L. Progress in the mechanical modulation of cell functions in tissue engineering. Biomater Sci. 2020;8(24):7033–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanchanawong P, Calderwood DA. Organization, dynamics and mechanoregulation of integrin-mediated cell-ECM adhesions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24(2):142–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kechagia JZ, Ivaska J, Roca-Cusachs P. Integrins as Biomechanical sensors of the microenvironment. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(8):457–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Z, Guo SS, Fassler R. Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction. J Cell Biol. 2016;215(4):445–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross TD, Coon BG, Yun S, Baeyens N, Tanaka K, Ouyang M, Schwartz MA. Integrins in mechanotransduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25(5):613–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz MA. Integrins and extracellular matrix in mechanotransduction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(12):a005066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu J, Feng F, Zhang S, Zhu Y, Song R, Li J, Zhao L, Wang H, Zhao Y, Zhang M. Thrombospondin-2 couples Pressure-Promoted chondrogenesis through NF-kappaB signaling. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2023;20(5):753–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isenberg JS, Qin Y, Maxhimer JB, Sipes JM, Despres D, Schnermann J, Frazier WA, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 and CD47 regulate blood pressure and cardiac responses to vasoactive stress. Matrix Biol. 2009;28(2):110–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou X, Zhang L, Lin X, Chen X, Liu H, Yuan X, Zhao Q, Wang W, Lei X, Jose PA, et al. Thrombospondin 2 is a novel biomarker of essential hypertension and associated with nocturnal Na(+) excretion and insulin resistance. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2023;45(1):2276029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams JC, Lawler J. The thrombospondins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(10):a009712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson CB, Lawler J, Mosher DF. Structures of thrombospondins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(5):672–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engel J. Role of oligomerization domains in thrombospondins and other extracellular matrix proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(6):997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams JC. Thrombospondins: multifunctional regulators of cell interactions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:25–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stenina OI, Topol EJ, Plow EF. Thrombospondins, their polymorphisms, and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(9):1886–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashiro Y, Thang BQ, Ramirez K, Shin SJ, Kohata T, Ohata S, Nguyen TAV, Ohtsuki S, Nagayama K, Yanagisawa H. Matrix mechanotransduction mediated by thrombospondin-1/integrin/YAP in the vascular remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(18):9896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Posey KL, Hankenson K, Veerisetty AC, Bornstein P, Lawler J, Hecht JT. Skeletal abnormalities in mice lacking extracellular matrix proteins, thrombospondin-1, thrombospondin-3, thrombospondin-5, and type IX collagen. Am J Pathol. 2008;172(6):1664–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochoa CD, Baker H, Hasak S, Matyal R, Salam A, Hales CA, Hancock W, Quinn DA. Cyclic stretch affects pulmonary endothelial cell control of pulmonary smooth muscle cell growth. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39(1):105–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isenberg JS, Romeo MJ, Yu C, Yu CK, Nghiem K, Monsale J, Rick ME, Wink DA, Frazier WA, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 stimulates platelet aggregation by blocking the antithrombotic activity of nitric oxide/cgmp signaling. Blood. 2008;111(2):613–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nergiz-Unal R, Lamers MM, Van Kruchten R, Luiken JJ, Cosemans JM, Glatz JF, Kuijpers MJ, Heemskerk JW. Signaling role of CD36 in platelet activation and thrombus formation on immobilized thrombospondin or oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(9):1835–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang K, Li M, Yin L, Fu G, Liu Z. Role of thrombospondin–1 and thrombospondin–2 in cardiovascular diseases (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2020;45(5):1275–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishna SM, Golledge J. The role of thrombospondin-1 in cardiovascular health and pathology. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(2):692–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang N, Wu X, Zhang W, Sun Y, Yan X, Xu A, Han Q, Yang A, You H, Chen W. Targeting thrombospondin-2 retards liver fibrosis by inhibiting TLR4-FAK/TGF-beta signaling. JHEP Rep. 2024;6(3):101014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bentley AA, Adams JC. The evolution of thrombospondins and their ligand-binding activities. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(9):2187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cingolani OH, Kirk JA, Seo K, Koitabashi N, Lee DI, Ramirez-Correa G, Bedja D, Barth AS, Moens AL, Kass DA. Thrombospondin-4 is required for stretch-mediated contractility augmentation in cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 2011;109(12):1410–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frolova EG, Sopko N, Blech L, Popovic ZB, Li J, Vasanji A, Drumm C, Krukovets I, Jain MK, Penn MS, et al. Thrombospondin-4 regulates fibrosis and remodeling of the myocardium in response to pressure overload. FASEB J. 2012;26(6):2363–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palao T, Medzikovic L, Rippe C, Wanga S, Al-Mardini C, van Weert A, de Vos J, van der Wel NN, van Veen HA, van Bavel ET, et al. Thrombospondin-4 mediates cardiovascular remodelling in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2018;35:12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chistiakov DA, Melnichenko AA, Myasoedova VA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN. Thrombospondins: A role in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Wilson ZS, Raya-Sandino A, Miranda J, Fan S, Brazil JC, Quiros M, Garcia-Hernandez V, Liu Q, Kim CH, Hankenson KD et al. Critical role of thrombospondin-1 in promoting intestinal mucosal wound repair. JCI Insight 2024, 9(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Crosby ND, Zaucke F, Kras JV, Dong L, Luo ZD, Winkelstein BA. Thrombospondin-4 and excitatory synaptogenesis promote spinal sensitization after painful mechanical joint injury. Exp Neurol. 2015;264:111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alford AI, Hankenson KD. Thrombospondins modulate cell function and tissue structure in the skeleton. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2024;155(Pt B):58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forbes T, Pauza AG, Adams JC. In the balance: how do thrombospondins contribute to the cellular pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease? Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021;321(5):C826–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tucker RP, Adams JC. Molecular evolution of the thrombospondin superfamily. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2024;155(Pt B):12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams JC. Thrombospondins: conserved mediators and modulators of metazoan extracellular matrix. Int J Exp Pathol. 2024;105(5):136–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawler J. Thrombospondins. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9(10):820–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan K, Duquette M, Liu JH, Dong Y, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Lawler J, Wang JH. Crystal structure of the TSP-1 type 1 repeats: a novel layered fold and its biological implication. J Cell Biol. 2002;159(2):373–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim CW, Pokutta-Paskaleva A, Kumar S, Timmins LH, Morris AD, Kang DW, Dalal S, Chadid T, Kuo KM, Raykin J, et al. Disturbed flow promotes arterial stiffening through Thrombospondin-1. Circulation. 2017;136(13):1217–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Belmadani S, Bernal J, Wei CC, Pallero MA, Dell’italia L, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Berecek KH. A thrombospondin-1 antagonist of transforming growth factor-beta activation blocks cardiomyopathy in rats with diabetes and elevated angiotensin II. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(3):777–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsumura K, Hayashi H, Uemura N, Ogata Y, Zhao L, Sato H, Shiraishi Y, Kuroki H, Kitamura F, Kaida T, et al. Thrombospondin-1 overexpression stimulates loss of Smad4 and accelerates malignant behavior via TGF-beta signal activation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2022;26:101533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jurk K, Clemetson KJ, de Groot PG, Brodde MF, Steiner M, Savion N, Varon D, Sixma JJ, Van Aken H, Kehrel BE. Thrombospondin-1 mediates platelet adhesion at high shear via glycoprotein Ib (GPIb): an alternative/backup mechanism to von Willebrand factor. FASEB J. 2003;17(11):1490–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freyberg MA, Kaiser D, Graf R, Buttenbender J, Friedl P. Proatherogenic flow conditions initiate endothelial apoptosis via thrombospondin-1 and the integrin-associated protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286(1):141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kvansakul M, Adams JC, Hohenester E. Structure of a thrombospondin C-terminal fragment reveals a novel calcium core in the type 3 repeats. EMBO J. 2004;23(6):1223–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lim XR, Harraz OF. Mechanosensing by vascular endothelium. Annu Rev Physiol. 2024;86:71–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jensen LF, Bentzon JF, Albarran-Juarez J. The phenotypic responses of vascular smooth muscle cells exposed to mechanical cues. Cells 2021, 10(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Chen LJ, Wei SY, Chiu JJ. Mechanical regulation of epigenetics in vascular biology and pathobiology. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17(4):437–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]