Abstract

Background

Real-time audiovisual communication between healthcare providers (HCP) at different hospitals (TeleNeonatology) can improve neonatal outcomes, address capacity challenges, and reduce emotional burden on parents. Despite its potential, TeleNeonatology has yet to be widely implemented in routine clinical care, partly due to non-optimal integration into care pathways and working routines. To provide insights for further adoption, this study presents the evaluation of a pilot in the Netherlands.

Methods

A prospective hybrid type III effectiveness-implementation study was conducted in 2024. During the pilot, a TeleNeo program facilitated both acute and elective communication between Erasmus MC NICU-level IV and Amphia NICU-level II. The TeleNeo program was developed and continuously improved during the pilot using co-creation with HCP and parents to enable embedding in care pathways and working routines. A mixed-methods approach was used for evaluation. The primary outcome was a validated 21-item usability questionnaire with five-points Likert Scale questions for parents (n = 50) and HCP (n = 85). Implementation determinants were evaluated with semi-structured interviews and surveys. Effectiveness was measured via parent reported experiences, and clinical outcomes length-of-stay and transfer rate.

Results

Twelve months of implementation led to 99 consultations for 50 patients and families, including 33 acute patients, possibly in need of an acute transfer. Evaluation showed high feasibility and adoption. Usability was high among parents (n = 26, median score 5 [interquartile rage: 4–5]) and HCP (n = 48, median score 5 [interquartile range 4–5]). Parents valued rapid expert availability, involvement in transfer decisions, and experienced shared care between the NICUs. HCP observed quick and approachable communication, quicker medical decisions, improved quality of care, and smoother transitions between NICUs. Nurses were able to be more pro-active. In 18% (6/33) of acute cases transfers were perceived to be prevented. HCP highlighted TeleNeo’s influence on the local teams’ autonomy, communication styles, and financial aspects as important barriers in interviews (n = 12) and questionnaires (n = 65).

Conclusions

Pilot implementation showed high feasibility of our TeleNeo program, enabling shared care at the optimal location for our patients. Our findings will guide a robust strategy for implementation in the Southwest of the Netherlands, enhancing neonatal care, parental satisfaction and nursing experience.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12887-025-05923-y.

Keywords: Telemedicine, Neonatology, Implementation science, Neonatal intensive care unit, Infant, Co-creation, Digital health

Background

Neonatal care in the Netherlands is regionally organized across three levels of care, ensuring neonates receive appropriate level of care as close to home as possible. However, increasing capacity strain, mainly due to nurse shortages [1], has created challenges in maintaining local high-quality neonatal care. Furthermore, there is a growing emphasis on improving both parental experience [2] and overall quality of care [3]. Addressing these challenges requires innovative approaches to optimize neonatal healthcare delivery.

Telemedicine, defined as the remote delivery of healthcare, is increasingly being used in healthcare delivery [4]. Within neonatal care, TeleNeonatology, offers potential for improving neonatal care [5]. Studies have demonstrated that TeleNeonatology, in the form of audio-visual communication between healthcare providers (HCP), can help overcome distances and support local patient management [6–8]. It has been shown to improve the quality of care by enabling comprehensive visual and (when necessary) radiological evaluations [9], improve parental experiences [10], and alleviate capacity strain at higher-level NICUs [11, 12].

Despite these potential benefits, the adoption and implementation of TeleNeonatology has not been widely spread. Telemedicine is generally considered a complex intervention, because of the need to be embedded into multiple working routines and match with wishes and demands from different stakeholders [13]. The success of implementation of complex interventions, such as TeleNeonatology, is challenging and proving effectiveness is often negatively influenced by multiple interrelated contextual factors [14, 15]. Important context specific barriers to successful adoption are lack of resources and time regulatory frameworks and finances, the attitude of healthcare professionals towards the intervention, and non-compatibility with existing working routines and care pathways [15–19]. Furthermore, as the impact of implementation is strongly context dependent, complex innovations cannot be directly transferred from one setting to another without adaptation [20]. Successful implementation requires four critical components: exploring local context, involving stakeholders, determining a clear value proposition, and tailoring the intervention to the local needs and workflows [20, 21]. Co-creation has been found to be an effective method to efficiently explore context and refine interventions with stakeholders to successfully embed interventions into existing care structures [22]. Involving local stakeholders, like physicians, nursing staff and parents, already from the design phase onward, helps to create shared understandings and contributes to adoption and sustainable implementation of technological innovations [23].

Given the potential benefits of TeleNeonatology in addressing capacity challenges in our region, we undertook a project to pilot its implementation. Our interest was to explore both the effectiveness of the intervention itself, as well as empirically studying its implementation strategies. By integrating approaches from implementation science and co-creation we designed a comprehensive pilot implementation to optimize local usability and sustainable implementation of TeleNeonatology. Using a hybrid implementation-effectiveness study design [24], we aimed to evaluate both the implementation strategies employed during the pilot of our TeleNeonatology program and the preliminary effectiveness of TeleNeonatology within our region in The Netherlands.

Methods

A hybrid type III implementation-effectiveness design was used to evaluate the pilot implementation of TeleNeonatology, as an obligatory real-time audiovisual add-on service to the communication between the Amphia Hospital NICU-level II and the Erasmus MC NICU-level IV from January 1 st 2024 to December 31 st 2024. The full study protocol was published previously [25]. The implementation process and a summary of the study protocol are presented in this methods section.

Implementation process

To ensure successful adoption, our implementation process focused on designing a TeleNeo program that smoothly integrates into the local neonatal care pathway, working routines and the parent journey. Therefore, our process entailed active stakeholder involvement, co-creation to develop the program together with stakeholders to create shared understanding, and continuous improvement throughout the pilot [13, 26].

Initial development of the TeleNeo program and implementation strategies

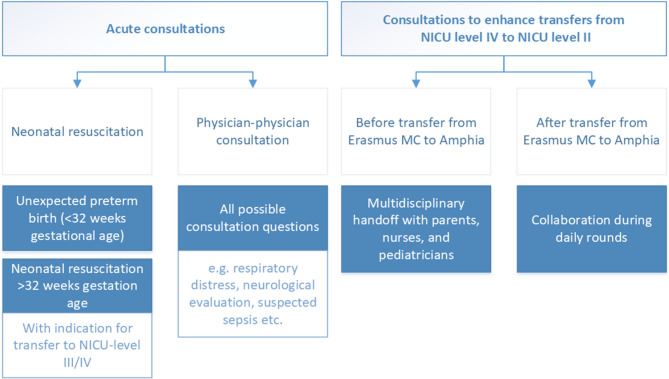

Prior to the start of the pilot, following guidance from implementation sciences [24, 27], we have performed a stakeholder analysis using the Salience model [28], a literature review, and context evaluation to explore barriers and facilitators for TeleNeonatology using the Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread and Sustainability (NASSS) framework [21]. Based on the identified barriers and facilitators [25], we developed our TeleNeo program and its corresponding implementation strategies in co-creation with pediatricians, nurses, a representative from the neonatal patient and parent advocacy organization, technicians, and managers [26, 29]. In summary, the TeleNeo program introduced real-time audiovisual consultations between the NICU-level II and NICU-level IV, referred to as TeleNeo consultations. TeleNeo consultations replaced telephonic consultations between NICU-level II pediatricians and NICU-level IV neonatologists, the current standard of care, for acute, or urgent, situations. A 24/7 availability was guaranteed by three remote neonatologists (TeleNeonatologists) on call. Furthermore, in our region, back transfers from NICU-level IV to NICU-level II are carried out as soon as a patient stabilizes (maximum level of respiratory support of continuous positive airway pressure of 5/6 and no need for invasive monitoring), and has reached a postmenstrual age of ≥ 30 weeks, and weight of ≥ 1000 g. Medical handoffs before back transfer are performed by phone and on paper between nurses and physicians separately. In our TeleNeo program, we designed elective, or planned, consultations including a multidisciplinary handoff with parents, nurses and physicians before transfer, and joint daily rounds after transfer (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Indications for TeleNeo consultations

Continuous improvement of the TeleNeo program

During the pilot we received personnel’s feedback on, among others, technical issues, perceived usefulness, communication and integration into daily work. The feedback was collected through TeleNeo consultation surveys, the midpoint evaluation questionnaires after 4 months of the pilot, focus group sessions with nurses and pediatricians after 4–5 months of the pilot, and informal talks throughout the pilot. This feedback was discussed during monthly evaluation sessions with our research team. Supplemental 1 presents a figure that illustrates the conceptualization of improvement cycles throughout the pilot, all modifications made during the pilot and a key example to illustrate the use of the continuous improvement cycles.

Technology

The Teladoc Lite 4 with Boom Arm from Teladoc Health (New York, United States) was used as the telemedicine device during the pilot. This device was chosen based on previous experience by colleagues [30] and a market exploration. They preferred this device as it is movable, has high-quality audio, three high-quality camera’s that can be used through the walls of an incubator, the ability to control the cameras remotely, and to connect other video sources such as an ultrasound machine or video laryngoscope.

Outcome measures

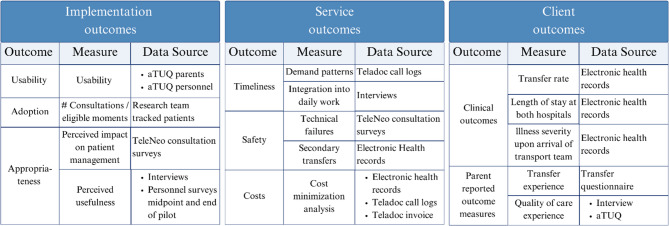

A mixed-methods approach was used to evaluate the implementation and preliminary effectiveness of TeleNeonatology [25]. A comprehensive set of outcomes measures was collected and categorized to (1) implementation outcomes, summarized as feasibility and measured by usability, adoption, and appropriateness, (2) service outcomes, e.g. timeliness and safety, and (3) client outcomes, e.g. transfer rates and parental experiences (Fig. 2). The costs analysis will be discussed in a separate article.

Fig. 2.

Outcome measures and data sources categorized to implementation, service, and client outcomes. Abbreviations: aTUQ, adjusted Telehealth Usability Questionnaire [31]. Secondary transfers were defined as a transfer > 2 h after a TeleNeo consultation where was decided not to transfer. Illness severity was objectified using the TRIPS-II score (Transport Risk Index of Physiologic Stability) [32]

Participants

All patients meeting indications for TeleNeo consultations (Fig. 1) were eligible to be included in the pilot. A sample size calculation was not performed, as the number of patients is dependent on clinical cases and the number of consultations was one of the implementation outcomes. Parents were asked informed consent to complete the adjusted Telehealth Usability Questionnaire (aTUQ, Supplemental 2). All HCP working with the TeleNeo at the Amphia Hospital were invited to participate in the evaluation questionnaires.

Data collection

Data sources were the electronic health records, questionnaires for parents and health care personnel, 12 semi-structured interviews with different types of stakeholders, and call logs from the Teladoc. The questionnaires used were the following (Supplemental 2); (1) TeleNeo surveys after each consultation to be filled in by both the local team and the TeleNeonatologists, (2) an adjusted version of the aTUQ with 21 5-point Likert scale questions on usefulness, ease of use, technical aspects, reliability and satisfaction of TeleNeonatology distributed to parents after consultations and to personnel at the midpoint and at the end of the pilot, and (3) a questionnaire designed for HCP at midpoint and at end of pilot incorporating targeted questions to assess the perceived usefulness and identify potential barriers for implementation success.

Patient, parent and HCP data collection was anonymized and managed using the CASTOR EDC data collection tool (Philadelphia, United States). Interviews were transcribed, group sessions were summarized by meeting notes, and the original recordings were deleted.

Data collection - changes made to the study protocol

In the protocol we aimed to interview more than one parent using semi-structured interviews and organize a focus group session. Unfortunately, we were only able to interview one parent and have four informal talks. Furthermore, our aim was to collect surveys to evaluate transfer experience. Due to organizational challenges only six questionnaires were completed and therefore, these results will not be discussed in this manuscript. Lastly, we aimed to use a retrospective cohort to compare our clinical course. The retrospective cohort should have consisted of patients for whom a (telephonic) consultation or transfer was conducted between the level-II and level-IV NICU. Since we were only able to retrieve patients who were transferred between the NICUs, we decided not to present this retrospective cohort as a comparator for transfer rates and length of stay, as it would induce a bias in the comparison.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed descriptively using Microsoft Excel. Since the aTUQ was distributed at two different time point with varying respondents, we analyzed responses from unique participants. For patients with an indicated change in patient management in the TeleNeo consultation survey, a group of 3 neonatologists discussed if TeleNeonatology also influenced their location of care, i.e. if a NICU-level IV transfer was prevented.

If a respondent completed the questionnaires twice, only results at the end of pilot were included in the analysis. Answers to open-ended questions and interview data were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis [33].

Patient and public involvement

Neonatal patient and parent advocacy association Care4Neo (www.care4neo.nl) was involved in the design and conduct of the trial, and in the reporting and dissemination of the results.

Results

During the 12-months implementation pilot, a total of 57 patients were eligible for inclusion. Seven eligible patients were not included: five were potential elective consultations not included due to planning or communication issues (n = 3), technical issues (n = 1) or choice of the treating neonatologist (n = 1). The two missed acute consultations were due to a technical failure (the device couldn’t be turned on at time of one consultation) and chosen by the treating neonatologist because the transport team was already close. A total of 99 TeleNeo consultations, 55 acute and 44 elective, were conducted for 50 included patients, with an average of two teleconsultations per patient (range: 1–9). Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the included patients and the clinical impact of TeleNeo consultations. Acute consultations were required for 33 patients, most commonly due to respiratory distress (n = 22/33, 66.7%), for other indications, see Table 1. Elective consultations aimed to enhance back transfers were conducted for 26 patients, with 17 patients receiving only elective consultations. 87% of the consultations surveys were fully completed (n = 87 out of 100 surveys, one from each hospital per patient). Missing values occurred for the questions: “Are you satisfied with the TeleNeo consultation?” (n = 2), and “Did a technical failure occur?” (n = 13). Twenty six out of 50 parents (all approached parents consented, with 100% response rate) completed the aTUQ. For HCP (nurses and pediatricians), the response rate was 42% (36 out of 85) completing the midpoint questionnaire and 36% (31 out of 87) the end of pilot questionnaire, resulting in 53 unique personnel respondents to the questionnaires and 48 completing the aTUQ. Nurses represented approximately 60% of the respondents (n = 40/67 total respondents and n = 30/53 unique respondents). The mean age of respondents was 43 years, with a self-reported technical affinity score of 6.8 out 10.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included patients

| Acute consultations (N = 33) | Elective consultations to enhance back transfers (N = 17a) | |

|---|---|---|

| TeleNeo consultations per patient | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1–3] |

| Characteristics | ||

| Gestational age at birth | 36 + 1 [33 + 6–39 + 1] | 28 + 5 [27 + 2–30 + 4] |

| Birthweight (grams) | 2518 (813) | 1235 (489) |

| Sex (female) | 20 (60.6%) | 12 (70.6%) |

| Gestational age at first consultation | 36 + 2 [34 + 1–39 + 1] | 32 + 5 [31 + 6–36 + 1] |

| Weight at first consultation | 2523 (804) | 1956 (674) |

| Mortality | 1 (3.0%) | 0 |

| TeleNeo consultations | ||

| Indication for consultationb | n/a | |

| Respiratory distress | 22 (66.7%) | |

| Neurological (asphyxia, convulsions) | 8 (24.2%) | |

| (Suspected) NEC | 4 (12.1%) | |

| Severely ill | 3 (9.0%) | |

| Other | 1 (3.0%) | |

| Neonatal resuscitation | 0 | |

| Not satisfied with consultationc | 0 out of 66 (0%) | 2 out of 34 (5.9%) |

| Technical issues occurred | 4 (12.1%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Impact on patient managementd | 18 (54.5%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Clinical course | ||

| Transferred to the NICU-level IV | 25 (75.8%) | n/a |

| Secondary transfers (> 2 h after consultation) | 3 (12%) | n/a |

| Transfers prevented | 6 (18.2%) | n/a |

| TRIPS-II score of transferred patientse | 17.5 [12.8–22] | n/a |

| Length of stay at NICU-level IV | 4 [3–7] | 31 [13–46] |

| Length of stay at NICU-level II | 11 [4–21] | 29 [18–40] |

Data presented as number of patients (%), mean (standard deviation) when normally distributed or median [interquartile range] when skewedness is observed

aFor this table we provided characteristics on the 17 patients with only elective consultations

bMultiple indications were registered for five patients

cDissatisfaction was based on the surveys after each consultations. Since both hospitals record surveys, dissatisfaction was presented for the total number of health care professionals

eThe TRIPS-II Score (Transport Risk Index of Physiological Stability) ranges from 0 to 65 based on temperature, blood pressure, respiratory status and neurological status, and was validated to predict mortality [32]

daccording to treating physicians as compared to standard of care (telephone consultations)

Implementation outcomes

Usability and adoption

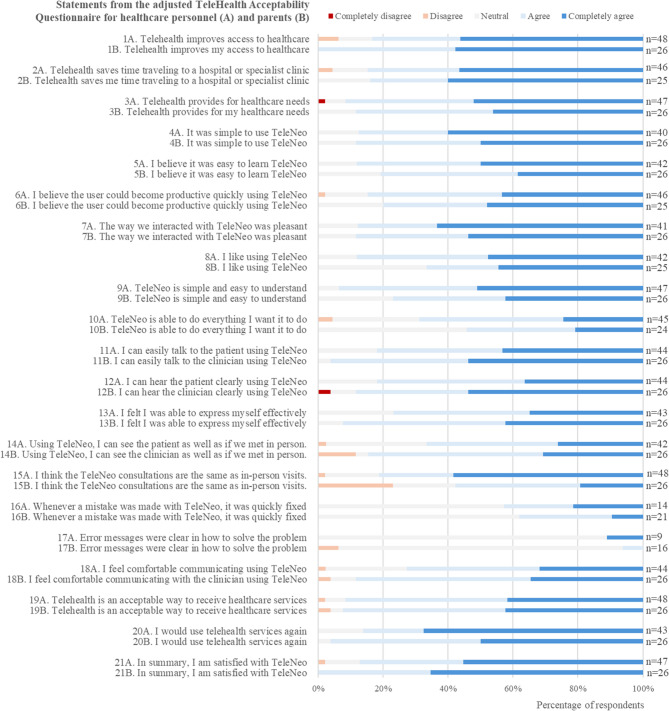

Usability was rated high, with a median score of 5 out of 5 [IQR: 4–5] by both parents and HCP in response to the question, “In summary, I am satisfied with TeleNeo”. Figure 3 presents parental and HCP responses to all 21 questions of the aTUQ. HCP particularly valued TeleNeo’s ease to use (statements 4 to 9), all receiving a mean score of ≥ 4.3 out of 5. Statement 20, “I would use telehealth services again”, scored best with a mean score of 4.5. Parents additionally appreciated the time saving aspect of TeleNeo (statement 2, median score of 5 [IQR4-5]). However, a slight discrepancy emerged regarding the statement, “I think TeleNeo consultations are the same as in-person visits”, where HCP gave a median score of 5[IQR: 4–5] and parents rated it lower at 4 [IQR:3–4]. Overall, disagreement with statements was minimal, with at most three personnel members per question disagreeing. Statements regarding technical issues received the lowers scores and had the fewest respondents, with “neutral” as the median response.

Fig. 3.

Responses to adjusted Telehealth Usability Questionnaire from healthcare personnel (n = 48) and parents (n = 26)

The adoption of TeleNeonatology, defined as the included number of patients divided by the number of eligible patients, was high (n = 50/57, 87.7%).

Appropriateness of teleneonatology

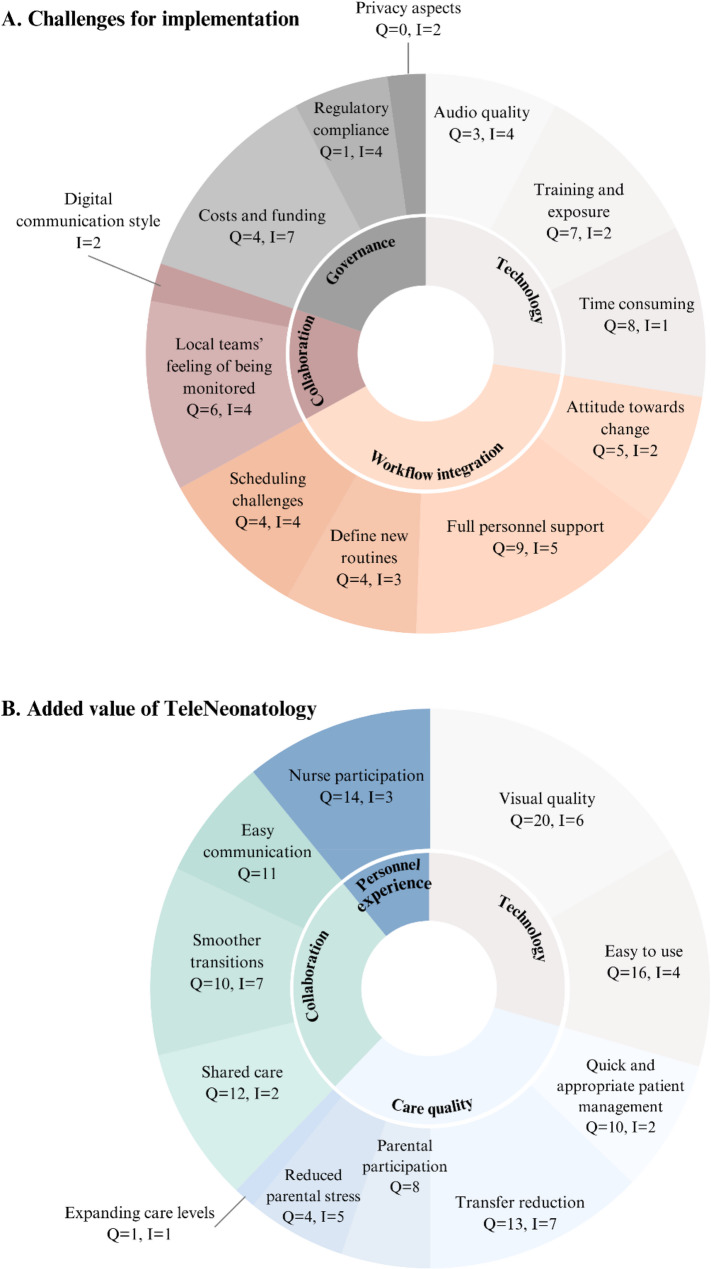

HCP reported in the TeleNeo consultations surveys that TeleNeonatology influenced patient management compared to standard of care in 40% (n = 20/50) of all patients, and in 55% (n = 18/33) of patients with acute consultations. Additionally, the added value of TeleNeonatology was evaluated by 12 interviews and HCP respondents to the questionnaires at the midpoint (n = 34) and end of the pilot (n = 31) (Supplemental 2 and Fig. 4). The visual information added to consultations via TeleNeonatology was seen as enhancing clinical assessments compared to telephonic consultations. The easy, quick, and accessible communication was perceived as an added value and to improve shared care. This is exemplified by questionnaire respondent 22 saying “[TeleNeo ensures] faster and better contact with NICU-level IV. They have a clearer view of the case and seem more involved.”

Fig. 4.

Challenges for implementation (A) and added value of TeleNeonatology (B) based on stakeholder interviews (n = 12) and personnel questionnaires (n = 65 with 53 unique respondents). Data presented as factor, questionnaire respondents (Q = n out of 65), interview respondents (I = n out of 12). Category sizes based on the total number of respondents (questionnaire and interview) that mentioned the specific factor

The majority of HCP agreed (score ≥ 4 out 5) with the statement that TeleNeo improved the quality of care for patients (28/30 respondents agreed) and parents (27/30 agreed) in both acute and elective consultations, attributed to faster and more adequate clinical management. As one HCP (questionnaire respondent 32) noted, “[The added value of TeleNeo is] rapid and efficient access to expertise in the right place, providing a comprehensive view of the patient and enabling timely interventions.”. Another (questionnaire respondent 10) stated, “Faster, better assessment by the remote neonatologist, leading to a quicker and more adequate treatment plan.”. Additionally, HCP (n = 13) mentioned that a potential transfer reduction was an important added value, “… this saves the patient from a tiring journey, and parents can stay in their ‘familiar’ environment instead of having to go to a level IV NICU, which in itself is already stressful.”(respondent 49). HCP also noted that TeleNeo improved parental experience by increasing parental participation in care and reducing stress related to interhospital transfers. Particularly, the elective consultations were perceived to enhance care for parents by 86% (n = 24 out of 28) of HCP (median score of 4 out of 5 [IQR: 4–5]).

Additionally, nearly half of the HCP respondents at the end of pilot (14 out of 29, median score: 3[IQR: 3–4]) believed that elective consultations reduced time required during patient admissions, as a substantial amount of information has already been shared beforehand. Furthermore, questionnaire respondent 81 explained that TeleNeo leads to a “good experience for parents. Safe care for the child. [.] It’s comforting for parents to see familiar faces after a transfer, ones they’ve already seen through TeleNeo.”. Respondents also noted smoother transitions between hospitals for both HCP and parents: “TeleNeo provides continuity of care and information for both the patient and the healthcare provider.” (respondent 77), “The remote neonatologist gains insight into the neonate both before an ICU-indicated intervention and afterward, ensuring a smoother transition during transport to the NICU-level IV.”(respondent 13), and “[The added value of TeleNeo is the] multidisciplinary handoff of patients so that parents have already met the new staff in the hospitals and see that the care plan is the same in the other hospital” (respondent 58).

Lastly, 21 out of 31 HCP at end of pilot, including 18 out of 20 nurses, reported that TeleNeo positively impacted their job experience, with a median score of 4 out 5 [IQR: 3–5]. Among the responding nurses, 55% (n = 11/20, score ≥ 4 out 5) indicated that they could participate more actively in acute situations and 70% (n = 14/20) felt a greater sense of involvement within the medical team.

Challenges for implementation

HCP noted perceived challenges for implementation in interviews (n = 12) and the questionnaires at midpoint (n = 34) and end of pilot (n = 31). Throughout the pilot, the primary barrier remained the perceived reduction of the local teams’ medical autonomy when communication occurs in the presence of parents. As explained by questionnaire respondent 67: “Although communication via TeleNeo is effective, nonverbal cues are difficult to pick up. In other words, concerns from parents or colleagues are harder to ‘read’ through TeleNeo. Does everyone still feel sufficiently heard when the physician from NICU-level IV speaks with parents? Does a colleague in the NICU-level II dare to express doubts about the proposed patient management in the presence of parents or other colleagues?”. Furthermore, the attitude of healthcare personnel towards change and the acceptance of a new technology, along with the challenge of getting all HCP on board were identified as implementation challenges. Technological aspects, like suboptimal audio quality, and minor delays in starting consultations due to getting used to the technology were also highlighted, mainly at the midpoint evaluation. Regular exposure to TeleNeo consultations was noted as essential to feel comfortable using the technology. As interview participant 5 mentioned, “Maybe it’s good to do a demo or training session more often and also keep repeating it, because it’s a skill you need to maintain’”. This sentiment was echoed by five questionnaire respondents, four of whom were at the midpoint evaluation. Moreover, “Defining clear roles for personnel from NICU-level II and NICU-level IV and how to organize this during a TeleNeo consultation.” (questionnaire respondent 77), was a challenge for both the interviews participants and questionnaire respondents, as well as the scheduling of elective consultations. Some respondents particularly highlighted the issue of integration into working routines, while others focused on the appropriate use-cases and the initiation of consultations, “It should not become an obligation or a routine for both teams to use TeleNeo. The initiative should primarily lie with the doctor (of course, in consultation), but the doctor should not feel obligated to use it if it is not yet necessary.” (questionnaire respondent 63). Lastly, finances and funding were mentioned as a barrier.

Service outcomes

For 7 out of 99 consultation a technical issue was observed, mainly caused by problems with the audio quality. The technical issues did not result in the inability to perform a TeleNeo consultation, but a restart was required for 2 consultations. One third of acute consultations took place during evening, night or weekend shifts (18/54, 33%). Consultations took on average 13 min and 19 s, ranging from 3 min to 51 s, the second consultation for a patient on the same day, to 57 min and 4 s, performing an INSURE procedure (intubate, surfactant, extubate) supported with TeleNeonatology using a connected video laryngoscope.

Client outcomes

The NICU transfer rate for acute consultations was 72.7% (24 out of 33 patients). Expert consensus concluded that TeleNeo consultations helped prevent six transfers from the level II to level IV NICU (18.2%). Among these six cases, two neonates with a necrotizing enterocolitis were treated conservatively at the level-II NICU with the involvement of a pediatric surgeon through TeleNeo. The remaining four, all presenting with respiratory distress, were stabilized through optimizing respiratory support, preventing the need for intubation and transfer. The median TRIPS-II score for 25 transferred patients was 17.5 on a scale from 0 to 65 [IQR: 12.8–22]. During the year pre-implementation, 23 patients were transferred from the Amphia NICU-level II to the Erasmus MC NICU-level IV, with a median TRIPS-II score of 15 [IQR: 11–22], indicating comparable illness severity upon transfer.

Additionally, for 12 out of 27 remaining acute patients, HCP noted that patient management was adjusted based on TeleNeo consultations compared to telephone consultations. Respiratory support was optimized for 10 of them, improving their clinical stability before transfer. The timing of transfer was safely extended by one day for two patients, and back transfer was expedited by one week for another patient. Furthermore, a fluid bolus was advised for one patient because of impaired circulation and sedatives adjustments were made for a patient with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the neonate.

Lastly, parents reported that TeleNeo consultations made them feel at ease because the remote neonatologist could be present quickly and transitions between hospitals were smoother, as explained by one parent: “It gives parents a sense of reassurance. You have the feeling that you are truly present.”.

Discussion

The comprehensive pilot implementation of TeleNeonatology, evaluated using a hybrid type III implementation-effectiveness design, demonstrated high feasibility for both parents and HCP. Over a one-year period, 99 TeleNeo consultations were conducted for 50 patients, including consultations in acute situations and elective consultations to enhance back transfers. Our TeleNeo program was developed and continuously improved with stakeholders using co-creations. Important perceived added values included: (1) easy, quick and accessible communication, (2) high quality visual information that facilitated faster and more adequate patient management, (3) increased parental participation, (4) smoother transitions between hospitals for both parents and healthcare personnel, and (5) improved job experience for nurses. By the end of the pilot, two main challenges for implementation remained: the perception of reduced autonomy for local medical teams and its’ impact on communication styles, and getting the whole team on board. Based on expert consensus, transfers between the NICU-level II and level IV were safely prevented for 18% of patients needing an acute consultation.

Reflection on implementation challenges

Technological barriers for implementation of TeleNeonatology frequently mentioned in literature include complex technologies, connectivity and audio issues, organizing frequent training of personnel, and challenges in keeping new staff informed about the technology [8, 34, 35]. In designing our TeleNeonatology program, we prioritized user-friendly technology with high-quality video. Our implementation strategies focused on non-time consuming and accessible training through an instruction video and frequent demonstration sessions. Our results indicate that HCP appreciated the ease of use and accessible trainings. While some technical issues were reported, these were mentioned by only a few HCP. Maintaining familiarity with the technology remained a challenge, for which repeated simulation-based training or increased use could be a solution.

Another commonly cited challenge is the negative attitude of healthcare personnel towards the change or intervention [8, 34]. To address this, we actively involved stakeholders from the beginning, ensuring that the program was either aligned with their expectations or extensively discussed and justified. As a result, only one respondent expressed concerns about the added value of the intervention.

The disruption of new technologies on existing workflows is also a well-documented barrier to implementation [8, 34, 36]. Despite our efforts to integrate the intervention into current workflows as seamlessly as possible, this remained a significant challenge at the midpoint evaluation. The continuous improvement cycles made it possible to quickly address this by organizing a multidisciplinary, multi-hospital, co-creation session where healthcare personnel took the opportunity to suggest improvement strategies. This collaborative approach proved effective, leading to a smoother integration by the end of the pilot. This serves as a strong example of how co-creation can facilitate the integration of an innovation into care pathways, care journeys and working routines of a complex medical settings.

A key remaining challenge we identified was the local teams’ concern about their competence being questioned or their autonomy being diminished, a barrier also highlighted in literature [8, 34]. Although only a few respondents mentioned this in our survey, we recognize it as a potential trust breaker and, consequently, a deal breaker for successful implementation. By the end of the pilot, we developed collaboration contracts to explicitly state that legal responsibility remains with the local team and drafted a communication plan to define the role of the remote TeleNeonatologist. However, trust between HCP across different hospital locations remains an essential foundation for successful implementation and long-term sustainability [37]. Financial challenges raised by respondents primarily concerned the impact of TeleNeonatology on the hospitals’ patient-related revenues and the need for reimbursement structures to be developed in order to achieve financially sustainable implementation and scaling. Therefore, business cases were developed for both hospitals to support decision making and secure approval for implementing TeleNeonatology following the pilot phase. Furthermore, better understand the economic implications and distribution of costs and benefits, the forthcoming economic evaluation will touch upon four different perspectives: the two hospitals, the healthcare system and the societal perspective.

Reflection on effectiveness of teleneonatology

Regarding the clinical impact of TeleNeonatology, experts estimated that for 18% of patients a transfer was prevented by using TeleNeo instead of telephone consultations. As expected, our findings showed smaller effect compared to studies from Albritton, et al. [11] and Haynes, et al. [12], who compared TeleNeonatology to telephonic consultations and reported respectively odds of transfer of 0.71 for neonatal resuscitations and 0.48 (95% CI 0.26–0.90, the adjusted odds) for NICU consultations. This difference is not surprising, given that our pilot implementation included a NICU-level II setting where two neonatologists are available, several nurses have had NICU-level IV training, and all HCP are required to undergo regular Neonatal (Advanced) Life Support training.

Strengths and limitations

Notable strengths of this pilot included the integration of different academic expertise, the early engagement of HCP and parents, and the thorough preparation prior the start of the pilot. By combining implementation science and co-creation, we created a well-rounded approach that supported effective integration within existing workflows. Additionally, the comprehensive evaluation and continuous improvement throughout the pilot provided us a strong foundation, both in terms of research data and really understanding the intervention, as well as in HCP’s perception, ensuring a smooth transition toward sustainable integration into standard of care [38].

An important limitation of this study is the absence of a control group for direct comparison. Despite efforts by the research team, we were unable to retrieve the complete cohort of patients for whom a telephonic consultation was performed in the year before implementation. While we could track patients who were transferred between hospitals through patient records, telephonic consultations were not consistently documented, making it impossible to identify non-transferred patients retrospectively. Another important limitation was the relatively high rate of missing questionnaire data, both for parents (n = 24/50, 48%) and HCP (n = 32/85, 38%). In case of parents, all missing data was due to the fact that they were not approached for consent. All approached parents consented and completed questionnaires. Decisions to not approach parents for consent were primarily attributable to two factors: the illness severity which the researchers to avoid burdening parents with the questionnaires, and the early discharge of patients before researchers found the opportunity to obtain consent. The relatively high rate of missing parental response may have introduced a bias, either toward more positive or negative responses as illness severity could both increase or reduce the perceived added value of TeleNeonatology. In case of HCP, the low response rate was for partly due to temporary factors, such as HCP being on leave, completed clinical rotations, or being students. The non-response may have introduced bias toward more positive results, as we expect the non-responders to have more neutral views and therefore less motivated to participate. To mitigate this limitation, we supplemented the questionnaires with live presentations and informal talks with both pediatricians and nurses, allowing us to gather additional feedback and suggestions to improve (see Supplemental 1).

Future steps

To further support the adoption and future scaling of TeleNeonatology to other hospitals in our region, several steps are needed. First, conduct an economic evaluation, including business cases from both hospital perspectives next to the healthcare system and societal perspective. Second, collaborate with HCP from the other regional hospitals to tailor the TeleNeo program to their specific context. Third, design a robust study protocol, for instance a stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial, with sufficiently large sample size and appropriate control group to evaluate clinical effect on transfer rates and length-of-stay.

Conclusion

This pilot implementation of a TeleNeo program, audio-visual communication between a NICU-level IV and NICU-level II, showed high feasibility. The addition of visual information and accessible communication during acute and elective consultations enhanced quality of care, improved parental and healthcare personnel experience, facilitated smoother transitions between the hospitals, and reduced the need for transfer. The comprehensive implementation process, integrating implementation science and co-creation, contributed significantly to integration of TeleNeonatology into existing workflows and supported the first steps towards sustainable implementation and regional scaling.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by Convergence| Healthy Start, a program of the Convergence Alliance – Delft University of Technology, Erasmus University Rotterdam and Erasmus Medical Center - to improve the future of new generations. Furthermore, the authors acknowledge the contribution of Saskia de Pont, Emma Zwaveling, Manuela Polderman, Jacqueline de Jong, Inez Leeuwenburg, Anne-Mieke van Breukelen, and all health care personnel at the NICU-level II of the Amphia hospital to this implementation pilot, and the participating parents for sharing their experiences. Lastly, the authors acknowledge Teladoc Health for their open collaboration and availability for technical advice and troubleshooting when needed.

Abbreviations

- aTUQ

Adjusted Telehealth Usability Questionnaire

- HCP

Healthcare provider(s)

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- TRIPS-II

Transport Risk Index of Physiological Stability score

Authors’ contributions

JW, HT, RB, MK and IR were involved in the conceptualization of the study design, with advice from SO and SH. JW and IR were responsible for funding. JW was research coordinator, responsible for data curation and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. JB performed and analyzed the interviews, designed and facilitated the co-creation session, all under supervision of FB. JB and JW together held multiple presentations and focus group interviews. JW and JB designed visualizations for this manuscript. HP, AJ, RB, HT, FC and IR were ‘TeleNeo experts’ on both study sites. SH provided advice on the methodology, focusing mainly on implementation science, and feedback on the manuscript draft. MK provided advice on methodology, focusing mainly on co-creation, and feedback on the manuscript draft. FC provided advice on methodology and reporting, focusing on quality improvement. MS was responsible for technical resources and technical workflow. SO helped developing parental questionnaires and design the content of elective consultations. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Stichting Vrienden van Sophia (project number WEL23-22).

Data availability

Responses to personnel surveys and research team notes are available as supplemental materials. The dataset containing anonymized patient records is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Erasmus MC with identification number: MEC-2023-0561. Informed consent was asked for completing the questionnaires. Exception consent was applicable for safety outcomes and demand patterns. The committee confirmed that the rules laid down in the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (also known as the Dutch abbreviation WMO) do not apply.

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wagenaar J, Franx A, Ernst-Snel H, Bertens L, De Vries L. ROAZ Regiobeeld Geboortezorg ZWN versie 2. juistezorgopdejuisteplek.nl. Traumacentrum Zuidwest-Nederland; 2023. november 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballantyne M, Orava T, Bernardo S, McPherson AC, Church P, Fehlings D. Parents’ early healthcare transition experiences with preterm and acutely ill infants: a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2017;43(6):783–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perined. Nieuwe Cijfers over internationale positie: Perined; 2019 Available from: https://www.perined.nl/nieuwe-cijfers-over-internationale-positie.

- 4.Colucci M, Baldo V, Baldovin T, Bertoncello C. A matter of communication: A new classification to compare and evaluate telehealth and telemedicine interventions and understand their effectiveness as a communication process. Health Inf J. 2019;25(2):446–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuo J, Makkar A, Machut K, Zenge J, Jagarapu J, Azzuqa A, Savani RC. Telemedicine across the continuum of neonatal-perinatal care. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;27(5): 101398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards G, O’Shea JE. Is telemedicine suitable for remotely supporting non-tertiary units in providing emergency care to unwell newborns? Arch Dis Child. 2023;109(1):5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang JL, Chuo J. Using telehealth to support pediatricians in newborn care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2021;51(1): 100952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makkar A, Sandhu T, Machut K, Azzuqa A. Utility of telemedicine to extend neonatal intensive care support in the community. Semin Perinatol. 2021;45(5): 151424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallford HG, Szyld E, McCoy M, Makkar A. A 360 evaluation of neonatal care quality at a level II neonatal intensive care unit when delivered using a hybrid telemedicine service. Am J Perinatol. 2024;41(S 01):e711–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagenaar J, Mah C, Bodell F, Reiss I, Kleinsmann M, Obermann-Borst S, Taal HR. Opportunities for telemedicine to improve parents’ well-being during the neonatal care journey: scoping review. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2024;7: e60610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albritton J, Maddox L, Dalto J, Ridout E, Minton S. The effect of a newborn telehealth program on transfers avoided: a multiple-baseline study. Health Aff Millwood. 2018;37(12):1990–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynes SC, Dharmar M, Hill BC, Hoffman KR, Donohue LT, Kuhn-Riordon KM, et al. The impact of telemedicine on transfer rates of newborns at rural community hospitals. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(5):636–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norman DA, Stappers PJ, DesignX. Complex sociotechnical systems. She ji: the journal of design. Econ Innov. 2015;1(2):83–106. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adlung C, van der Kooij N, Diehl JC, Hinrichs-Krapels S. Existing and emerging frameworks for the adoption and diffusion of medical devices and equipment in low-resource settings: a scoping review. Health Technol. 2025. 10.1007/s12553-024-00938-4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross J, Stevenson F, Lau R, Murray E. Factors that influence the implementation of e-health: a systematic review of systematic reviews (an update). Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peden CJ, Stephens T, Martin G, Kahan BC, Thomson A, Rivett K, et al. Effectiveness of a national quality improvement programme to improve survival after emergency abdominal surgery (EPOCH): a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10187):2213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook R, Lamont T, Martin R. National quality improvement programmes need time and resources to have an impact. BMJ. 2019;367:l5462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark J, McGee-Lennon M. A stakeholder-centred exploration of the current barriers to the uptake of home care technology in the UK. J Assist Technol. 2011;5(1):12–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, Lynch J, Hughes G, A’Court C, et al. Beyond adoption: A new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the Scale-Up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(11):e367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions: gap analysis, workshop and consultation-informed update. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(57):1–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenhalgh T, Abimbola S. The NASSS framework - a synthesis of multiple theories of technology implementation. Stud Health Technol Inf. 2019;263:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bender-Salazar R. Design thinking as an effective method for problem-setting and needfinding for entrepreneurial teams addressing wicked problems. J Innov Entrepreneurship. 2023;12(1):24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Drumpt S, Timan T, Talie S, Veugen T, van de Burgwal L. Digital transitions in healthcare: the need for transdisciplinary research to overcome barriers of privacy enhancing technologies uptake. Health Technol. 2024;14(4):709–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagenaar J, van Beek R, Pas H, Suurveld M, Jacobs A, Van der Linden N et al. Implementation and effectiveness of teleneonatology for neonatal intensive care units: a protocol for a hybrid type III implementation pilot. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2025;9(1):e002711 10.1136/bmjpo-2024-002711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Sanders EBN, Stappers PJ. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign. 2008;4(1):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson N, Naylor PJ, Ashe MC, Fernandez M, Yoong SL, Wolfenden L. Guidance for conducting feasibility and pilot studies for implementation trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020;6(1):167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapiriri L, Donya Razavi S. Salient stakeholders: using the salience stakeholder model to assess stakeholders’ influence in healthcare priority setting. Health Policy Open. 2021;2:100048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters GJ, Mullen PD, Parcel GS, Ruiter RA, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(3):297–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck JA, Jensen JA, Putzier RF, Stubert LA, Stuart KD, Mohammed H, et al. Developing a newborn resuscitation telemedicine program: A comparison of two technologies. Telemedicine e-Health. 2018;24(7):481–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parmanto B, Lewis AN Jr., Graham KM, Bertolet MH. Development of the telehealth usability questionnaire (TUQ). Int J Telerehabil. 2016;8(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SK, Aziz K, Dunn M, Clarke M, Kovacs L, Ojah C, et al. Transport risk index of physiologic stability, version II (TRIPS-II): a simple and practical neonatal illness severity score. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30(5):395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Davey L, Jenkinson E. Doing reflexive thematic analysis. In: Bager-Charleson S, McBeath A, editors. Supporting research in counselling and psychotherapy: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang JL, Asiedu GB, Harris AM, Carroll K, Colby CE. A mixed-methods study on the barriers and facilitators of telemedicine for newborn resuscitation. Telemed J E-Health. 2018;24(10):811–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curfman A, Groenendyk J, Markham C, Quayle K, Turmelle M, Tieken B, et al. Implementation of telemedicine in pediatric and neonatal transport. Air Med J. 2020;39(4):271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saifan AR, Odeh MS, Oleimat B, AbuRuz ME, Ahmed AM, Abdel Razeq NM, et al. Exploring the impact and challenges of tele-ICU: a qualitative study on nursing perspectives. Appl Nurs Res. 2025;82: 151914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garro-Abarca V, Palos-Sanchez P, Aguayo-Camacho M. Virtual teams in times of pandemic: factors that influence performance. Front Psychol. 2021;12: 624637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham HR, Oliwa J. Using theory to understand how interventions work and inform future implementation. Lancet Global Health. 2025;13(2):e177–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Responses to personnel surveys and research team notes are available as supplemental materials. The dataset containing anonymized patient records is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.