Abstract

The major fungal pathogen, Candida albicans, exists as a commensal in the gastrointestinal tract of healthy humans. Fungal colonisation levels increase during gut dysbiosis, when the local microbiota and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) concentrations become perturbed. Individually, acetic, propionic and butyric acids are reported to exert differential effects on C. albicans. In this study, we tested whether combinations of these SCFAs, at concentrations that broadly reflect healthy and dysbiotic gut profiles, influence virulence-related phenotypes. The selected healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes slowed the growth of C. albicans SC5314, increased resistance to cell wall stresses (Calcofluor White, SDS, caspofungin), differentially affected the exposure of the key cell surface pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) β-1,3-glucan, chitin and mannan, and influenced total chitin content compared with non-SCFA controls. However, few differences were observed between the healthy and dysbiotic mixes. Furthermore, comparison of isolates from other epidemiological clades revealed that most effects of the SCFA mixes were strain-specific, reflecting the high degree of phenotypic variation reported previously between clinical isolates. Interestingly, the healthy SCFA mix inhibited hyphal development to a greater extent than the dysbiotic mix in some C. albicans isolates including SC5314. This was not reflected in differential adhesion to Caco-2 cells or in altered virulence in the Galleria model of systemic candidiasis. We conclude that SCFA mixtures reflecting those present in the human gut subtly influence some virulence-related phenotypes in C. albicans in a strain-specific manner.

Introduction

Candida albicans is arguably unique amongst fungal pathogens due to its ability to transition between commensal and pathogenic states, the variety and frequency of infections it causes, and the extensive research on its pathobiology [1].

C. albicans is frequently found in the intestinal microbiota of humans and is the Candida species most frequently isolated from the faeces of healthy humans [2, 3]. During intestinal colonisation, C. albicans interacts with multifarious microbes that influence the ability of this fungus to establish itself in this niche. The microbiota of the mouse intestine generally inhibits C. albicans colonisation [4, 5], and probiotic bacteria can limit the severity of C. albicans infections in immunocompromised mice and germ-free mice [6]. In humans, C. albicans can colonise the healthy gut, but the likelihood of developing candidemia is enhanced by treatments with broad-spectrum antibiotics [7].

The intestinal microbiota inhibits C. albicans colonisation partly by generating molecules that directly impact the fungus and/or by eliciting host responses that target the fungus [1, 8–10]. For example, Lactobacillus rhamnosus inhibits C. albicans morphogenesis by producing an exopolysaccharide and the chitinase Msp1 [11, 12]. Enterococcus faecalis attenuates fungal morphogenesis and virulence by secreting the peptide EntV [13]. Bacterial-derived metabolites affect C. albicans proliferation [14], and SCFAs in particular have been implicated in promoting gut-barrier integrity, immune regulation, anti-inflammatory responses and the excretion of antimicrobial functions [15].

Antibiotic-driven changes in the gut microbiota lead to decreased levels of bacterial-derived SCFAs [16], and increased fungal colonisation and dissemination [17–19]. Acetic, propionic and butyric acids are the most abundant SCFAs produced by microbial fermentation of indigestible polysaccharides, simple sugars, sugar alcohols and unabsorbed or undigested proteins in the intestine [15, 20]. SCFAs can act as weak acid stressors, but the colon (pH ~ 6.5) lies above the pKa for acetic, propionic and butyric acid [21–23]. SCFA abundances vary between individuals, influenced by their microbiota and diet [24], and low SCFA concentrations can be used as biomarkers of a dysbiotic gut microbiome [25].

SCFAs attenuate C. albicans growth [26] and butyrate inhibits yeast-hypha morphogenesis [27]. SCFA resistance in C. albicans is dependent on Mig1 [28] and Hgt16 [29]. These proteins are likely to enhance glycolytic flux as Mig1 is a regulator of glucose repression [30, 31] and Hgt16 is a putative glucose transporter. This would be consistent with the demand for metabolic energy during stress adaptation [32]. Stress adaptation involves neutralisation of the stress, the repair of stress-mediated damage, plus the requisite energy generation via the upregulation of genes involved in glycolysis, ATP synthesis and mitochondrial respiration [22, 29, 33–36]. Consequently there are strong links between carbon source and stress resistance in C. albicans [31, 37, 38].

Previous studies have tended to examine the influence of individual SCFAs upon C. albicans [28, 39–41]. However, the fungus is generally exposed to combinations of SCFAs in vivo, and C. albicans can display unexpected sensitivities to combinatorial inputs [42, 43]. Therefore, our aim was to test whether SCFA mixtures that reflect healthy or dysbiotic colons [18, 44–47] differentially affect C. albicans phenotypes involved in intestinal colonisation and virulence. Here, we describe the impact of such SCFA mixtures upon growth, yeast-hypha morphogenesis, the exposure of cell wall-associated pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), adhesion and virulence.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Growth Conditions

The following C. albicans clinical isolates were used in this study: SC5314 (clade 1; bloodstream) [48]; IHEM16614 (clade 2; oropharynx), J990102 (clade 3; vagina) and AM2005/0377 (clade 4; oral commensal) [49]; and CEC3544 (clade 1; commensal), CEC3610 (clade 4; commensal), CEC3638 (clade 3; commensal), CEC3662 (clade 1; invasive) and CEC3669 (clade 2; superficial) [50].

C. albicans cells were grown in SD (2% glucose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids) or on YPD agar (2% agar, 2% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone). To prepare SCFA-containing media, stock solutions of acetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), butyric acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and propionic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) were added at the specified final concentrations to SD, the media buffered to pH 6.5 using 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) (Fisher), and filter sterilised. For phenotypic analyses, C. albicans cells were grown overnight in SD at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. These cells were used to inoculate fresh media at a starting OD600 of 0.2, grown for 3 h at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm), and harvested for analysis.

Stress Resistance

Resistance to cell wall stressors was assayed in 96-well plate format in liquid media (final volume 200 μl) using C. albicans cells grown overnight in SD. Cells were harvested, resuspended in sterile water, and inoculated to a final OD600 of 0.1 into SD (no stress control), SD containing stressor, SD containing stressor plus healthy SCFA mix, or SD containing stressor plus dysbiotic SCFA mix (Fig. 1A). Stressors included: 100 μg/ml calcofluor white (CFW), 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) and 3.2 μg/ml caspofungin. Plates were sealed with a breathable film, incubated at 37 °C, and growth (OD600) assayed at 24 h. Thermal stress was also examined by comparing growth at 30, 37 and 42 °C. The impact of the stressor was calculated by dividing the percentage of growth (OD600) in the presence of the stress by the growth in the absence of stress. Means and standard deviations from six independent replicates are shown. The data were analysed using ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparison tests: ns, p > 0.05; **, p 0.01; ***, p 0.001; ****, p 0.0001.

Fig. 1.

SCFA mixes impact the growth of C. albicans SC5314. a SCFA concentrations in mixes designed based on those observed in healthy and dysbiotic human guts (see text). b The growth of C. albicans SC5314 in SD containing no SCFAs (control), the three healthy SCFA mixes, or the three dysbiotic SCFA mixes (see key). The mixes selected for subsequent experiments were healthy mix 2 (dark blue squares) and dysbiotic mix 3 (red diamonds). Note that the points for dysbiotic mix 2 lie underneath those for healthy SCFA mixes 1 and 3. Means from n = 6 replicates for one representative experiment of three independent experiments are shown

Stress resistance was also examined using spot assays. C. albicans cells were grown to exponential phase in SD, diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 in fresh medium, a series of tenfold dilutions prepared, and these cell suspensions spotted onto SD agar containing the specified stressor. Plates were incubated for 24–72 h at 37 °C and then imaged using a GBox (SynGene). Representative results from three independent experiments are presented.

PAMP Exposure and Chitin Content

PAMP exposure was quantified by flow cytometry using published procedures [51, 52]. C. albicans strains were grown overnight in SD, subcultured into fresh SD containing the specified SCFA mix and grown at 37 °C for 3 h. These exponential cells were fixed in 50 mM thimerosal (Sigma-Aldrich) [51], washed, counted using a Vi-CELL BLU Counter (Beckman Coulter), brought to a concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml, and stained with Fc-Dectin-1 and anti-human IgG conjugated to Alexaflour 488 (β−1,3-glucan exposure), with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA: chitin exposure) or with Concanavalin A (ConA: mannan exposure)[52–54]. Fluorescence was quantified using a BD Fortessa flow cytometer and analysed using FlowJo v10.8.1 software. Fold changes in PAMP exposure were calculated by dividing the Median Fluorescence Intensity in the presence of SCFA mix (MFISCFA) by the MFI for the control condition, SD alone (MFICONTROL). Data represent means and standard deviations from three biological replicates, each of which captured 10,000 events. The data were analysed using ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparison test: ns, p > 0.05.

The total chitin content of C. albicans cells grown was measured by flow cytometry, as described previously [52]. Briefly, thimerosal-fixed cells were stained with 5 μg/ml CFW for 15 min, washed, and the MFI quantified from 10,000 events using a BD Fortessa flow cytometer, as described previously [52]. Means and standard deviations from three biological replicates were analysed using ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparison test: ns, p > 0.05; *, p 0.05.

Yeast-Hypha Morphogenesis

To assay yeast-hypha morphogenesis, C. albicans cultures were grown overnight in SD at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm), diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 in fresh SD supplemented with 3% foetal bovine serum, and incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm). Cells were then fixed overnight in 50 mM thimerosal (Sigma-Aldrich) [51], washed thrice in sterile milliQ water, stained with 5 μg/ml CFW for 5 min, and washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Cells were resuspended in 100 μl PBS containing 2 mM EDTA. The proportion of germ tubes versus ovoid yeast cells was then quantified using an Amnis Imagestream MKII Imaging Flow Cytometer (Luminex) [55]. IDEAs v6.3 software was used to gate yeast and germ tube populations based on their cell circularity and length. Means and standard deviations from three independent replicates are shown. The data were analysed using ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparison tests: ns, p > 0.05; ****, p 0.0001.

Adhesion to Caco-2 Cells

Caco-2 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FCS at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and seeded into 24-well plates at 1 × 105 cells/ml in fresh medium. After 3 days, once a confluent Caco-2 cell layer had formed, 1 ml of fresh pre-warmed medium was added. Meanwhile, exponential C. albicans cells, grown in SD containing or lacking SCFAs, were harvested, washed, resuspended in PBS, counted, and adjusted to 2 × 105 cells/ml in pre-warmed DMEM without FBS. Yeast suspensions were added to the 24-well plate (500 μL per well) and incubated with the Caco-2 cells at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1 h. Medium and non-adhering fungal cells were then removed and remaining plated onto YPD agar to quantify adherent fungal cells (CFUs). Data represent means and standard deviations from two independent replicate experiments, each with 12 technical replicates. The data were analysed ANOVA using Turkey’s multiple comparison tests: ns, p > 0.05.

Virulence Assays

C. albicans virulence was assayed in the Galleria mellonella model of systemic candidiasis, as described previously [53]. C. albicans cells were grown overnight in SD at 37 °C, subcultured into SD with or without an SCFA mix and harvested in exponential phase, as described above. The cells resuspended in sterile PBS at 1 × 107 cells/ml. These cell suspensions (10 μl) were injected through the last proleg of G. mellonella larvae (n = 20 larvae per condition), the larvae incubated at 37 °C, and their survival monitored daily. Survival curves were compared using the Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test and the Logrank test for trends.

Results

Effects of Healthy and Dysbiotic SCFA Mixes upon C. albicans Growth

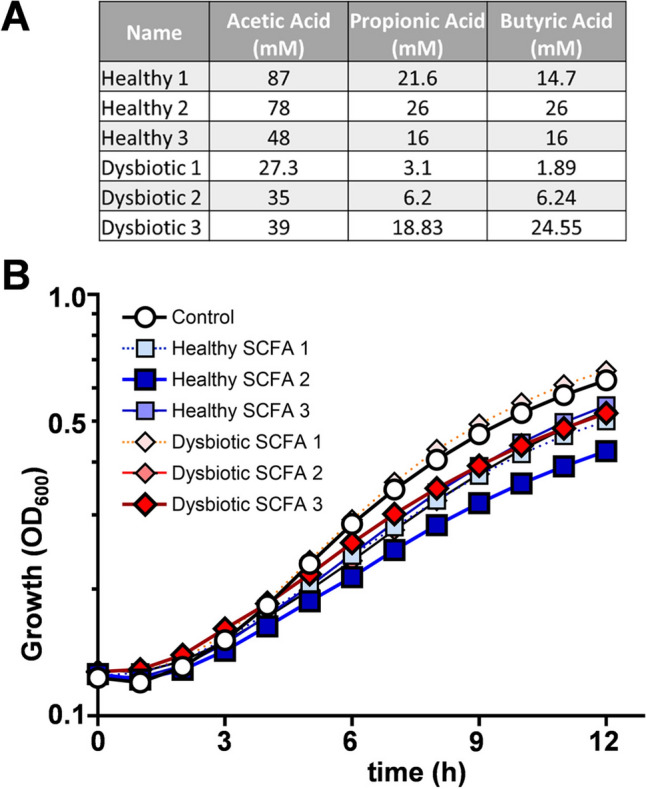

Our overall aim was to test whether SCFA mixtures encountered in the healthy and dysbiotic gut affect commensal- and virulence-associated phenotypes in C. albicans. SCFA abundances can vary between individuals and are impacted by many factors including, but not limited to, diet, microbiome composition and host health [56, 57]. Therefore our first objective was to select SCFA mixtures based on previously published literature that broadly reflect those reported for ‘healthy’ and ‘dysbiotic’ human gut profiles [18, 44–47]. We focussed on the most abundant SCFAs (acetic, propionic and butyric acids).

Initially we designed three SCFA mixtures reflecting the healthy state, and three for the dysbiotic state (Fig. 1A). Healthy SCFA concentrations were selected based on studies assessing SCFA concentrations in human cohorts [44, 45, 58]. The dysbiotic SCFA concentrations we selected from studies looking at the impact of antibiotics and disease (in this case colorectal cancer) on SCFA concentrations in rodents and humans [46, 47]. Where SCFA concentrations were obtained from rodent studies, we applied the percentage changes in SCFAs induced by antibiotics in mice to the healthy SCFA mix 2 to generate humanised dysbiotic SCFA concentrations (Fig. 1A). The mixes were designed to reflect typical healthy or dysbiotic SCFA concentrations rather than the full range of concentrations observed. We did not include single SCFA controls in our assays as the effects of individual SCFAs have been published [22, 37, 59–62].

We tested whether exposure to any of the six SCFA mixes influences growth of the commonly used clinical isolate, C. albicans SC5314, in minimal medium. Most of the SCFA mixes, except for dysbiotic mix 1, slowed the growth of the fungus when compared to the control lacking SCFAs (Fig. 1B). Dysbiotic mix 3 was selected for subsequent experiments as it reflects SCFA concentrations observed in a diseased human cohort (colorectal cancer patients). Healthy SCFA mix 2 was chosen because, of all the mixes examined, it inhibited C. albicans growth to the greatest extent.

Impact of SCFA Mixes upon C. albicans Cell Wall Stress Resistance

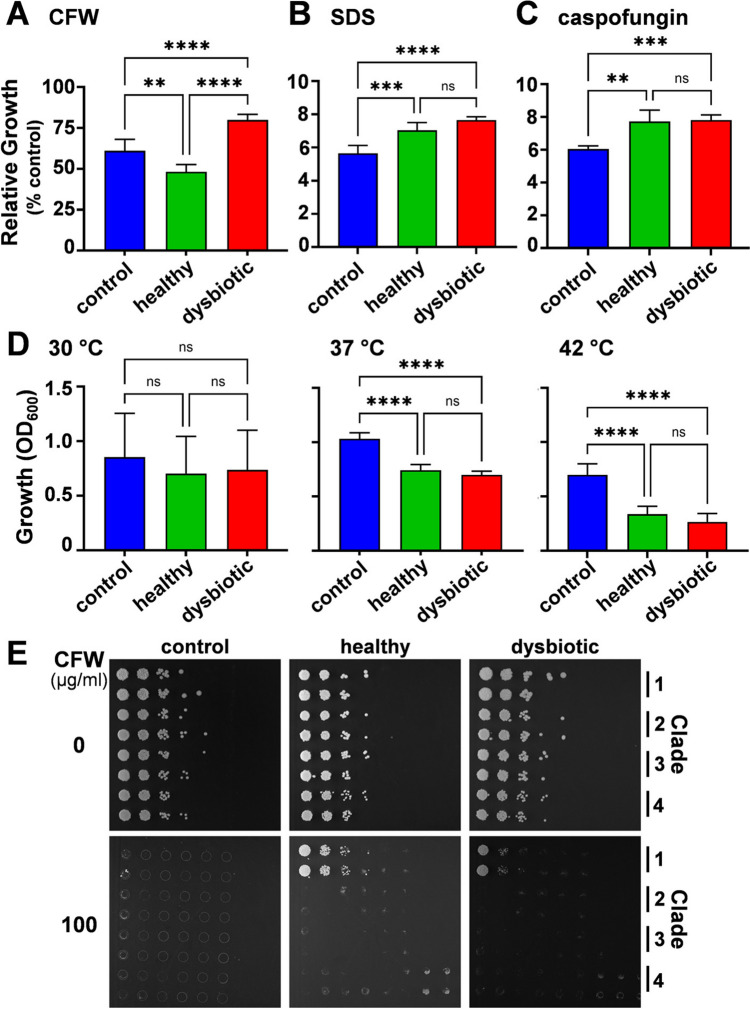

To determine whether these SCFA mixes influence sensitivity to cell wall stresses, phenotyping assays were performed in 96-well plate format. C. albicans SC5314 cells were inoculated into SD containing healthy SCFA mix 2, dysbiotic SCFA mix 3, or no SCFAs. Various cell wall stressors were added [100 μg/ml Calcofluor White (CFW), 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), or 3.2 μg/ml caspofungin], and growth at 37 °C quantified by monitoring the OD600 after 24 h. Growth in the presence of SCFA mixes was also compared at 30, 37 and 42 °C because thermal stress is known to affect the cell wall [63, 64]. The presence of SCFAs significantly influenced the resistance of C. albicans SC5314 cells to each of the cell wall stresses examined (Fig. 2A–D). The SCFA mixes increased resistance to SDS and caspofungin, but reduced resistance to thermal stress (Fig. 2B–D). However, no significant differences were observed between the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes in terms of their effects upon resistance to these stresses. Interestingly, under these experimental conditions, C. albicans SC5314 was more sensitive to CFW in the presence of the healthy mix, and more resistant to CFW with the dysbiotic SCFA mix (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

The impact of SCFA mixes on C. albicans cell wall stress phenotypes. C. albicans SC5314 cells were grown at 37 °C in SD without SCFAs (blue), with healthy SCFA mix 2 (green), or with dysbiotic SCFA mix 3 (red) in the presence or absence of cell wall stress: a 100 μg/ml CFW; (b) 0.5% SDS; or (c) 3.2 μg/ml caspofungin. Growth after 24 h in the presence of stress was measured (OD600) as a percentage of growth in the absence of stress. d Thermal sensitivity was determined by measuring the growth after 24 h of C. albicans SC5314 cells in SD at 30 °C, 37 °C, or 42 °C. Means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments are shown. The data were analysed using ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparison tests: ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. e The CFW resistance of C. albicans isolates from different clades was compared: clade 1, SC5314; clade 2, IHEM16614; clade 3, J990102; clade 4, AM2005/0377. Duplicate series of dilutions of each isolate were plated onto SD agar, supplemented with glucose, containing no SCFAs, healthy SCFA mix 2, or with dysbiotic SCFA mix 3, and 0 or 100 μg/ml CFW, and imaged after 48 h

Given the potential significance of elevated cell wall stress resistance in vivo, we tested whether the differential effects of the SCFA mixes upon CFW resistance represented a general or strain-specific phenomenon. To achieve this, we compared the CFW resistance of C. albicans isolates from different epidemiological clades on agar plates containing the different SCFA mixes. Under these conditions (growth on plates rather than in broth), C. albicans SC5314 cells displayed elevated CFW resistance with both healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes (Fig. 2E), as opposed to CFW sensitivity with the healthy mix (Fig. 2A). Differences in local pH, aeration and/or quorum sensing may account for variations in stress sensitivities observed between microtiter well and plate assays [22, 65]. Significantly, the isolates from clades 2–4 did not display elevated CFW resistance in response to either SCFA mix (Fig. 2E). We conclude that SCFA-induced CFW resistance is a strain-specific phenotype, rather than a general phenomenon in C. albicans.

Healthy and Dysbiotic SCFA Mixes Do Not Differentially Affect Cell Wall PAMPs or Chitin Content

Exposure to certain individual SCFAs has been shown to influence the exposure of the proinflammatory PAMP β−1,3-glucan at the C. albicans cell surface, and this affects the ability of innate immune cells to recognise the fungus and trigger antifungal immune responses [61]. Butyrate enhances β−1,3-glucan exposure [52], whereas lactate masks this PAMP by inducing the shaving of exposed β−1,3-glucan from the cell surface [61, 66]. These studies examined the impact of individual SCFAs on β−1,3-glucan exposure. Here, we examined the combinatorial effects of healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes upon the exposure of additional cell surface PAMPs.

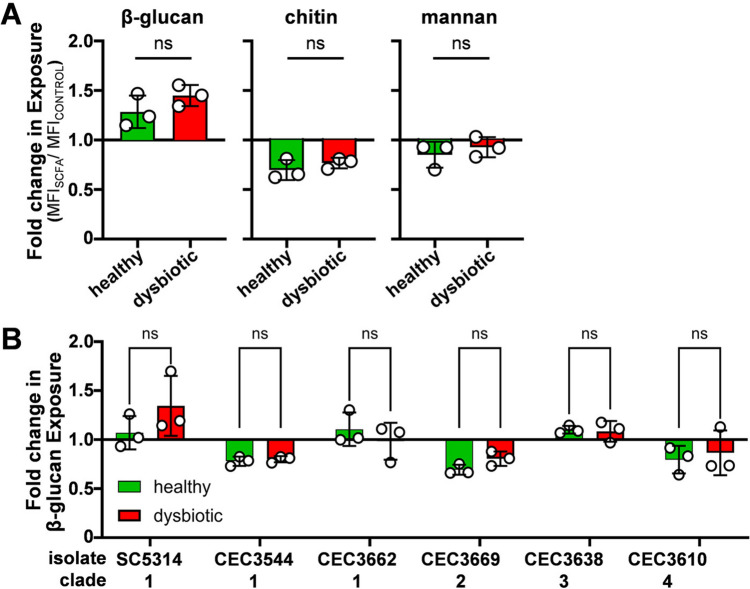

To determine the impact of the SCFA mixes upon β−1,3-glucan, chitin and mannan exposure at the C. albicans cell surface, SC5314 cells were harvested during exponential growth on SD containing or lacking the SCFA mixes. These cells were harvested, fixed, stained with Fc-Dectin-1 (exposed β−1,3-glucan), wheat germ agglutinin (WGA: exposed chitin) and Concanavalin A (ConA: exposed mannan), and the fluorescence of each quantified by flow cytometry. The impact of each SCFA mix upon each PAMP was quantified by dividing the Median Fluorescence Index (MFI) in the presence of the SCFA mix relative to the MFI in the absence of SCFA (fold change = MFISCFA/MFICONTROL). C. albicans SC5314 displayed some changes in β−1,3-glucan, chitin and mannan exposure in response to the SCFA mixes, but no significant differences were observed between the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Influence of SCFA mixes on PAMP exposure at the C. albicans cell surface. a C. albicans SC5314 cells were grown in SD containing the healthy or dysbiotic SCFA mix and their fold changes in β−1,3-glucan, chitin and mannan exposure measured relative to control cells grown without SCFAs. Fixed cells were stained with Fc-dectin-1 (β-glucan), wheat germ agglutinin (chitin) and Concanavalin A (mannan) and their fluorescence quantified by flow cytometry. To calculate fold changes in exposure, an MFI for SCFA-treated cells was divided by the corresponding MFI for untreated cells. b The effects of the SCFA mixes upon β−1,3-glucan exposure were compared for C. albicans clinical isolates from different clades. Means and standard deviations from three independent replicates are shown, and the data were analysed using ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparison test. No statistically significant differences between healthy and dysbiotic SCFA samples were observed

Given that we had observed strain-specific differences in CFW resistance (Fig. 2E), we compared the effects of the SCFA mixes upon β−1,3-glucan exposure for C. albicans isolates from different clades. Differential responses were observed between strains, some displaying reductions in β−1,3-glucan exposure (e.g. CEC3544, CEC3669, CEC3610) and others showing minimal changes (CEC3662, CEC3638) (Fig. 3B). However, none of the isolates tested displayed significantly different responses to the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes.

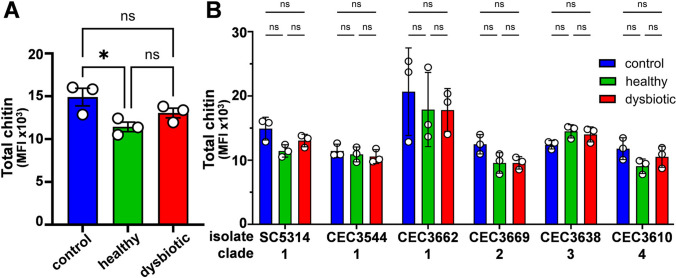

Cell wall stresses, and echinocandins in particular, induce cell wall remodelling in C. albicans, leading to an increase in chitin content [67–69]. Therefore, we assayed the total chitin content of C. albicans SC5314 cells grown in the presence of the healthy or dysbiotic SCFA mixes by staining cells with CFW and quantifying their fluorescence intensity (MFI) by flow cytometry [52]. The chitin content of cells grown with an SCFA mix was found to be lower than the SCFA-free control, but only those cells grown with the healthy SCFA mix displayed a significantly reduced chitin content (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

The impact of SCFA mixes on the chitin content of C. albicans cells. a The chitin content of C. albicans SC5314 cells was measured during exponential growth on SD (control) or SD containing the healthy or dysbiotic SCFA mix. Chitin content was assayed by staining fixed cells with CFW and measuring their fluorescence by flow cytometry. b The effects of the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes on chitin content were compared for C. albicans clinical isolates from different clades. Means and standard deviations for three independent experiments are shown. The data were analysed using ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparison tests: ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05

Given the strain variation we had observed for other phenotypes (above), we examined additional C. albicans isolates. In general, the chitin contents of six isolates from clades 1–4 decreased during growth with the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes, but none of these changes were statistically significant (Fig. 4B). We conclude that, under the conditions we used, the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes we examined do not differentially affect the degree of exposure of cell wall PAMPs or the total chitin content of C. albicans cells.

The SCFA Mixes Inhibit Yeast-Hypha Morphogenesis

Exposure to butyrate at concentrations above 25 mM has been shown to inhibit hyphal development, whereas acetate or propionate were not inhibitory at 100 mM [27]. The healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes we examined contained butyrate at concentrations around 25 mM (see healthy mix 2 and dysbiotic mix 3; Fig. 1A). Therefore, we tested whether the presence of acetate and propionate in these mixes compromises the inhibitory effects of butyrate on yeast-hypha morphogenesis. To assay germ tube formation, C. albicans SC5314 cells were inoculated into SD containing foetal bovine serum, incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h, and the proportion of yeast cells and germ tubes quantified by imaging flow cytometry. Both the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes significantly inhibited germ tube formation (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the dysbiotic SCFA mix appeared slightly less inhibitory than the healthy SCFA mix, but in this experiment this difference was not statistically significant.

Fig. 5.

The impact of the SCFA mixes on C. albicans morphogenesis, adhesion and virulence. a Germ tube formation was measured by imaging cytometry during growth at 37 °C in SD containing foetal bovine serum. C. albicans SC5314 cells were grown with no SCFAs (control) or with healthy or dysbiotic SCFA mixes, fixed and stained with CFW to permit efficient gating and quantification of yeast cells and germ tubes. Means and standard deviations from three independent replicates are shown in the left panel. The right panels show the cytometric gating for one of these experiments. Images of gated germ tubes (hyphae) and non-gated budding cells are superimposed on histograms of the imaging cytometry outputs from samples exposed to no (control), healthy or dysbiotic SCFA mixes. b The impact of the SCFA mixes on germ tube formation was compared in C. albicans clinical isolates from different clades. The data represent means and standard deviations from three independent replicates and were analysed using ANOVA with Turkey’s multiple comparison tests: ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p 0.0001. c C. albicans SC5314 cells were harvested during exponential growth in SD (control) or SD containing the healthy or dysbiotic SCFA mix and incubated with Caco-2 cells for 1 h, and then adherent fungal cells quantified by plating (n = 24 replicates). The data were analysed ANOVA using Turkey’s multiple comparison tests: ns, not significant. d C. albicans SC5314 cells were grown in SD (control) or SD containing an SCFA mix, 106 cells or the PBS carrier alone were injected per G. mellonella larva (n = 20 per group), and survival of the larvae was monitored daily. No significant differences were observed between the survival curves for the SD control or SCFA mixes using the Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test and the Logrank test for trend

C. albicans isolates display significant genetic and phenotypic variability with respect to virulence-related phenomena [1, 70–72]. Therefore, we tested whether this morphogenesis phenotype was strain-specific by examining C. albicans isolates from different epidemiological clades. Not surprisingly [1, 70–72], these isolates displayed differing efficiencies of germ tube formation in the absence of the SCFA mixes (Fig. 5B). CEC3638 and CEC3610 showed minimal germ tube formation under the experimental conditions analysed. In all the remaining isolates, hyphal development was inhibited by the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes, and this trend was statistically significant for those isolates displaying more efficient germ tube formation (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, the dysbiotic SCFA mix was significantly less inhibitory than the healthy SCFA mix for those strains showing more than 10% germ tube formation under control conditions at the 1.5 h timepoint examined (SC5314 and CEC3662). The inference is that C. albicans hyphal development might be inhibited more effectively by the SCFAs in the healthy gut.

The SCFA Mixes Do Not Affect Adhesion or Virulence

We then tested whether the SCFA mixes affect the ability of C. albicans to adhere to Caco-2 cells, an epithelial cell line derived from human colon. C. albicans SC5314 cells were grown in SD containing the healthy or dysbiotic SCFA mix or without SCFAs, harvested, washed and incubated with Caco-2 cells for 1 h. Non-adherent fungal cells were washed from the Caco-2 monolayers, and the adherent fungal cells quantified by plating onto YPD agar (CFUs). No significant differences in adherence were observed between SCFA-exposed and non-exposed C. albicans cells (Fig. 5C).

The impact of the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes upon C. albicans virulence was tested in Galleria mellonella larvae. This invertebrate model of systemic candidiasis has been reported to reflect fungal virulence in murine models with reasonable accuracy [73, 74]. The larvae displayed similar survival rates when injected with C. albicans SC5314 cells grown without SCFAs or with the SCFA mixes (Fig. 5D). We conclude that exposure to the healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes examined does not affect the adhesion of C. albicans to human colon epithelial cells or virulence in the Galleria infection model.

Discussion

Our expectation was that SCFA mixtures reflecting the healthy gut might attenuate virulence-related phenotypes in C. albicans to a greater extent than those representing the dysbiotic gut. This expectation seemed to be borne out by the inhibitory effects of the SCFA mixes upon yeast-hypha morphogenesis. Germ tube formation was inhibited to a greater extent by the healthy SCFA mix, albeit in an isolate-dependent manner (Fig. 5). This was consistent with the earlier observations that butyrate inhibits morphogenesis [27] and that antibiotic-induced decreases in gut SCFAs promote C. albicans colonisation [18].

The strain-dependent influence of SCFAs upon yeast-hypha morphogenesis was interesting in the context of commensalism and virulence. Differences in hyphal development between isolates drive differential degrees of tissue penetration, damage and inflammation in the host, thereby affecting the ability of C. albicans to colonise mucosal tissue [75–78]. In the gut, hyphal development reduces colonisation in the absence of the local microbiota [79–81], but enhances colonisation in the presence of the microbiota [82]. Hence, hyphal development lies at the heart of the fungus-host-microbiota interactions that mediate the delicate balance between C. albicans commensalism and pathogenicity [78]. Significantly, the ability of C. albicans isolates to colonise the mammalian gut seems to correlate with the degree to which SCFAs inhibit morphogenesis in these isolates [83]. Therefore, bacterial-derived SCFAs may reduce the competitiveness of C. albicans in the healthy gut in an isolate-dependent manner. Given that supplementation of drinking water with acetic and butyric acids reduced gastrointestinal colonisation by C. albicans in antibiotic-treated mice [84], and ignoring palatability issues, dietary supplementation with SCFAs could conceivably have therapeutic value under certain circumstances.

C. albicans isolates also display variability in their stress resistance and PAMP masking [50, 85]. These phenotypes influence immune recognition and virulence [86–88]. Therefore, any differential impacts between healthy and dysbiotic SCFA mixes upon these phenotypes would have been relevant in vivo. However, whilst these mixes influenced cell wall stress resistance (Fig. 2) and PAMP exposure to a limited extent (Fig. 3), no differential effects between the SCFA mixes were observed. Furthermore, the SCFA mixes did not significantly influence chitin content (Fig. 4), or adhesion to epithelial cells (Fig. 5A) under the conditions examined. Not surprisingly, no effects upon virulence were observed, even though the G. mellonella model has proven useful when assessing the virulence of C. albicans mutants with filamentation defects [73, 89, 90].

It should be noted that with a view to parsing apart the influence of these SCFA mixes from confounding factors, we employed well-defined growth media that differ significantly from conditions in the colon. For example, alternative carbon sources are known to influence stress resistance and virulence in C. albicans [37, 91]. Recent efforts to better replicate the intestinal environment in vitro include use of the SHIME model [92], gut microbiota medium [93] and organoids [94]. These models may provide an opportunity to study the effects of SCFA mixtures on C. albicans under conditions closer to the intestinal environment (such as during slow growth in the absence of sugars [95], in competition with the microbiota, or under hypoxic conditions). Ideally, such studies would compare multiple C. albicans isolates given the high degree of genetic and phenotypic variation between isolates both within and between epidemiological clades [1, 70, 71] and the ability of this fungus to evolve rapidly in response to local pressures [72, 80].

Acknowledgements

We thank Christophe d’Enfert for the provision of clinical isolates. This work was funded by a programme grant from the UK Medical Research Council [MR/M026663/2], Wellcome Investigator Awards (224323/Z/21/Z and 217163/Z/19/Z), and a PhD studentship to EH from the University of Exeter. The work was also supported by the Medical Research Council Centre for Medical Mycology at the University of Exeter (MR/N006364/2 and MR/V033417/1) and the NIHR Exeter Biomedical Research Centre. NARG also acknowledges additional support from Wellcome (224323/Z/21/Z, 200208/A/15/Z, 215599/Z/19/Z). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Additional work may have been undertaken by the University of Exeter Biological Services Unit. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Validation, Methodology: EH, IL, AP, QM, RY. Supervision, Project administration: NARG, GDB, AJPB. Funding acquisition: NARG, GDB, AJPB. Writing – original draft: EH, AJPB. Writing – review & editing: IL, AP, QM, RY, NARG, GDB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Medical Research Council (GB),MR/M026663/2, Alistair JP Brown, Medical Research Council Centre for Medical Mycology, MR/N006364/2, Gordon D. Brown, MR/V033417/1, Gordon D. Brown, Wellcome Trust, 224323/Z/21/Z, Neil A. R. Gow, 101873/Z/13/Z, Neil A. R. Gow, 224323/Z/21/Z, Neil A. R. Gow, 200208/A/15/Z, Neil A. R. Gow, 215599/Z/19/Z, Neil A. R. Gow, 217163/Z/19/Z, Gordon D. Brown, NIHR Exeter Biomedical Research Centre

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.d’Enfert C, Kaune AK, Alaban LR, Chakraborty S, Cole N, Delavy M et al (2021) The impact of the Fungus-Host-Microbiota interplay upon Candida albicans infections: current knowledge and new perspectives. FEMS Microbiol Rev 45(3):060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nash AK, Auchtung TA, Wong MC, Smith DP, Gesell JR, Ross MC et al (2017) The gut mycobiome of the human microbiome project healthy cohort. Microbiome 5(1):153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallen-Adams HE, Suhr MJ (2017) Fungi in the healthy human gastrointestinal tract. Virulence 8(3):352–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koh AY (2013) Murine models of candida gastrointestinal colonization and dissemination. Eukaryot Cell 12(11):1416–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuo K, Haku A, Bi B, Takahashi H, Kamada N, Yaguchi T et al (2019) Fecal microbiota transplantation prevents Candida albicans from colonizing the gastrointestinal tract. Microbiol Immunol 63(5):155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner RD, Pierson C, Warner T, Dohnalek M, Farmer J, Roberts L et al (1997) Biotherapeutic effects of probiotic bacteria on candidiasis in immunodeficient mice. Infect Immun 65(10):4165–4172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappas PG, Lionakis MS, Arendrup MC, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Kullberg BJ (2018) Invasive candidiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primer 4(1):1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pérez JC (2021) The interplay between gut bacteria and the yeast Candida albicans. Gut Microbes 13(1):1979877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romani L, Zelante T, De Luca A, Iannitti RG, Moretti S, Bartoli A et al (2014) Microbiota control of a tryptophan-AhR pathway in disease tolerance to fungi. Eur J Immunol 44(11):3192–3200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shulzhenko N, Morgun A, Hsiao W, Battle M, Yao M, Gavrilova O et al (2011) Crosstalk between B lymphocytes, microbiota and the intestinal epithelium governs immunity versus metabolism in the gut. Nat Med 17(12):1585–1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allonsius CN, van den Broek MFL, De Boeck I, Kiekens S, Oerlemans EFM, Kiekens F et al (2017) Interplay between Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Candida and the involvement of exopolysaccharides. Microb Biotechnol 10(6):1753–1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allonsius CN, Vandenheuvel D, Oerlemans EFM, Petrova MI, Donders GGG, Cos P et al (2019) Inhibition of Candida albicans morphogenesis by chitinase from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Sci Rep 9(1):2900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham CE, Cruz MR, Garsin DA, Lorenz MC (2017) Enterococcus faecalis bacteriocin EntV inhibits hyphal morphogenesis, biofilm formation, and virulence of Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(17):4507–4512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García C, Tebbji F, Daigneault M, Liu NN, Köhler JR, Allen-Vercoe E et al (2017) The human gut microbial metabolome modulates fungal growth via the TOR signaling pathway. mSphere 2(6):e00555-e617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL (2020) The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Front Endocrinol 31(11):25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Y, Wu J, Li JV, Zhou NY, Tang H, Wang Y (2013) Gut microbiota composition modifies fecal metabolic profiles in mice. J Proteome Res 12(6):2987–2999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy MJ, Volz PA (1985) Effect of various antibiotics on gastrointestinal colonization and dissemination by Candida albicans. Sabouraudia 23(4):265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guinan J, Wang S, Hazbun TR, Yadav H, Thangamani S (2019) Antibiotic-induced decreases in the levels of microbial-derived short-chain fatty acids correlate with increased gastrointestinal colonization of Candida albicans. Sci Rep 20(9):8872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCrory C, Lenardon M, Traven A (2024) Bacteria-derived short-chain fatty acids as potential regulators of fungal commensalism and pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol 32(11):1106–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Usta-Gorgun B, Yilmaz-Ersan L (2020) Short-chain fatty acids production by Bifidobacterium species in the presence of salep. Electron J Biotechnol 1(47):29–35 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piper P, Calderon CO, Hatzixanthis K, Mollapour M (2001) Weak acid adaptation: the stress response that confers yeasts with resistance to organic acid food preservatives. Microbiology 147(Pt 10):2635–2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsdale M, Selway L, Stead D, Walker J, Yin Z, Nicholls SM et al (2008) MNL1 regulates weak acid–induced stress responses of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell 19(10):4393–4403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans DF, Pye G, Bramley R, Clark AG, Dyson TJ, Hardcastle JD (1988) Measurement of gastrointestinal pH profiles in normal ambulant human subjects. Gut 29(8):1035–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE et al (2014) Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505(7484):559–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregory AL, Pensinger DA, Hryckowian AJ (2021) A short chain fatty acid–centric view of Clostridioides difficile pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog 17(10):e1009959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang CB, Altimova Y, Myers TM, Ebersole JL (2011) Short- and medium-chain fatty acids exhibit antimicrobial activity for oral microorganisms. Arch Oral Biol 56(7):650–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noverr MC, Huffnagle GB (2004) Regulation of Candida albicans morphogenesis by fatty acid metabolites. Infect Immun 72(11):6206–6210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cottier F, Tan ASM, Xu X, Wang Y, Pavelka N (2015) MIG1 regulates resistance of Candida albicans against the fungistatic effect of weak organic acids. Eukaryot Cell 14(10):1054–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cottier F, Tan ASM, Yurieva M, Liao W, Lum J, Poidinger M et al (2017) The transcriptional response of candida albicans to weak organic acids, carbon source, and MIG1 inactivation unveils a role for HGT16 in mediating the fungistatic effect of acetic acid. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics 7(11):3597–3604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murad AM, d’Enfert C, Gaillardin C, Tournu H, Tekaia F, Talibi D et al (2001) Transcript profiling in Candida albicans reveals new cellular functions for the transcriptional repressors CaTup1, CaMig1 and CaNrg1. Mol Microbiol 42(4):981–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagree K, Woolford CA, Huang MY, May G, McManus CJ, Solis NV et al (2020) Roles of Candida albicans Mig1 and Mig2 in glucose repression, pathogenicity traits, and SNF1 essentiality. PLoS Genet 16(1):e1008582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holyoak CD, Stratford M, McMullin Z, Cole MB, Crimmins K, Brown AJ et al (1996) Activity of the plasma membrane H(+)-ATPase and optimal glycolytic flux are required for rapid adaptation and growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the presence of the weak-acid preservative sorbic acid. Appl Environ Microbiol 62(9):3158–3164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enjalbert B, Smith DA, Cornell MJ, Alam I, Nicholls S, Brown AJP et al (2006) Role of the Hog1 stress-activated protein kinase in the global transcriptional response to stress in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell 17(2):1018–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Causton HC, Ren B, Koh SS, Harbison CT, Kanin E, Jennings EG et al (2001) Remodeling of yeast genome expression in response to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell 12(2):323–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen D, Toone WM, Mata J, Lyne R, Burns G, Kivinen K et al (2003) Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol Biol Cell 14(1):214–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gasch AP, Spellman PT, Kao CM, Carmel-Harel O, Eisen MB, Storz G et al (2000) Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell 11(12):4241–4257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ene IV, Adya AK, Wehmeier S, Brand AC, MacCallum DM, Gow NAR et al (2012) Host carbon sources modulate cell wall architecture, drug resistance and virulence in a fungal pathogen. Cell Microbiol 14(9):1319–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ene IV, Walker LA, Schiavone M, Lee KK, Martin-Yken H, Dague E et al (2015) Cell wall remodeling enzymes modulate fungal cell wall elasticity and osmotic stress resistance. MBio. 10.1128/mbio.00986-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cottier F, Tan ASM, Chen J, Lum J, Zolezzi F, Poidinger M et al (2015) The transcriptional stress response of Candida albicans to weak organic acids. G3 Bethesda Md 5(4):497–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen LN, Lopes LCL, Cordero RJB, Nosanchuk JD (2011) Sodium butyrate inhibits pathogenic yeast growth and enhances the functions of macrophages. J Antimicrob Chemother 66(11):2573–2580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lourenço A, Pedro NA, Salazar SB, Mira NP (2019) Effect of acetic acid and lactic acid at Low pH in growth and azole resistance of candida albicans and candida glabrata. Front Microbiol 8(9):3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaloriti D, Tillmann A, Cook E, Jacobsen M, You T, Lenardon M et al (2012) Combinatorial stresses kill pathogenic Candida species. Med Mycol 50(7):699–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaloriti D, Jacobsen M, Yin Z, Patterson M, Tillmann A, Smith DA et al (2014) Mechanisms underlying the exquisite sensitivity of Candida albicans to combinatorial cationic and oxidative stress that enhances the potent fungicidal activity of phagocytes. MBio. 10.1128/mbio.01334-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP, Macfarlane GT (1987) Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 28(10):1221–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machiels K, Joossens M, Sabino J, De Preter V, Arijs I, Eeckhaut V et al (2014) A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 63(8):1275–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holota Y, Dovbynchuk T, Kaji I, Vareniuk I, Dzyubenko N, Chervinska T et al (2019) The long-term consequences of antibiotic therapy: role of colonic short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) system and intestinal barrier integrity. PLoS ONE 14(8):e0220642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niccolai E, Baldi S, Ricci F, Russo E, Nannini G, Menicatti M et al (2019) Evaluation and comparison of short chain fatty acids composition in gut diseases. World J Gastroenterol 25(36):5543–5558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gillum AM, Tsay EY, Kirsch DR (1984) Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5’-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol Gen Genet MGG 198(2):179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacCallum DM, Castillo L, Nather K, Munro CA, Brown AJP, Gow NAR et al (2009) Property differences among the four major Candida albicans strain clades. Eukaryot Cell 8(3):373–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Avelar GM, Pradhan A, Ma Q, Hickey E, Leaves I, Liddle C et al (2024) A CO2 sensing module modulates β-1,3-glucan exposure in Candida albicans. MBio 15(2):e0189823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pradhan A, Avelar GM, Bain JM, Childers DS, Larcombe DE, Netea MG et al (2018) Hypoxia promotes immune evasion by triggering β-glucan masking on the candida albicans cell surface via mitochondrial and cAMP-protein kinase a signaling. MBio 9(6):e01318-e1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pradhan A, Avelar GM, Bain JM, Childers D, Pelletier C, Larcombe DE et al (2019) Non-canonical signalling mediates changes in fungal cell wall PAMPs that drive immune evasion. Nat Commun 22(10):5315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Assis LJ, Bain JM, Liddle C, Leaves I, Hacker C, Peres da Silva R et al (2022) Nature of β-1,3-glucan-exposing features on candida albicans cell wall and their modulation. MBio 13(6):e02605-e2622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma Q, Pradhan A, Leaves I, Hickey E, Roselletti E, Dambuza I et al (2024) Impact of secreted glucanases upon the cell surface and fitness of Candida albicans during colonisation and infection. Cell Surf 1(11):100128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ballard E, Yucel R, Melchers WJG, Brown AJP, Verweij PE, Warris A (2020) Antifungal activity of antimicrobial peptides and proteins against aspergillus fumigatus. J Fungi 6(2):65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kruger K, Myeonghyun Y, van der Wielen N, Kok DE, Hooiveld GJ, Keshtkar S et al (2024) Evaluation of inter- and intra-variability in gut health markers in healthy adults using an optimised faecal sampling and processing method. Sci Rep 14(1):24580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM (2013) The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res 54(9):2325–2340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Topping DL (1996) Short-chain fatty acids produced by intestinal bacteria. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 5(1):15–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ene IV, Heilmann CJ, Sorgo AG, Walker LA, de Koster CG, Munro CA et al (2012) Carbon source-induced reprogramming of the cell wall proteome and secretome modulates the adherence and drug resistance of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Proteomics 12(21):3164–3179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alves R, Mota S, Silva S, Rodrigues FC, Brown AJ, Henriques M, Casal M, Paiva S (2017) The carboxylic acid transporters Jen1 and Jen2 affect the architecture and fluconazole susceptibility of Candida albicans biofilm in the presence of lactate. Biofouling 33(10):943–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ballou ER, Avelar GM, Childers DS, Mackie J, Bain JM, Wagener J et al (2016) Lactate signalling regulates fungal β-glucan masking and immune evasion. Nat Microbiol 12(2):16238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kastora SL, Herrero-de-Dios C, Avelar GM, Munro CA, Brown AJP (2017) Sfp1 and Rtg3 reciprocally modulate carbon source-conditional stress adaptation in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol 105(4):620–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leach MD, Budge S, Walker L, Munro C, Cowen LE, Brown AJP (2012) Hsp90 orchestrates transcriptional regulation by Hsf1 and cell wall remodelling by MAPK signalling during thermal adaptation in a pathogenic yeast. PLoS Pathog 8(12):e1003069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ibe C, Munro CA (2021) Fungal cell wall proteins and signaling pathways form a cytoprotective network to combat stresses. J Fungi Basel Switz 7(9):739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Westwater C, Balish E, Schofield DA (2005) Candida albicans-conditioned medium protects yeast cells from oxidative stress: a possible link between quorum sensing and oxidative stress resistance. Eukaryot Cell 4(10):1654–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Childers DS, Avelar GM, Bain JM, Pradhan A, Larcombe DE, Netea MG et al (2020) Epitope shaving promotes fungal immune evasion. MBio. 10.1128/mbio.00984-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Walker LA, Lenardon MD, Preechasuth K, Munro CA, Gow NAR (2013) Cell wall stress induces alternative fungal cytokinesis and septation strategies. J Cell Sci 126(12):2668–2677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.da SilvaDantas A, Nogueira F, Lee KK, Walker LA, Edmondson M, Brand AC et al (2021) Crosstalk between the calcineurin and cell wall integrity pathways prevents chitin overexpression in Candida albicans. J Cell Sci 134(24):258889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walker LA, Munro CA, de Bruijn I, Lenardon MD, McKinnon A, Gow NAR (2008) Stimulation of chitin synthesis rescues candida albicans from echinocandins. PLOS Pathog 4(4):e1000040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hirakawa MP, Martinez DA, Sakthikumar S, Anderson MZ, Berlin A, Gujja S et al (2015) Genetic and phenotypic intra-species variation in Candida albicans. Genome Res 25(3):413–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ropars J, Maufrais C, Diogo D, Marcet-Houben M, Perin A, Sertour N et al (2018) Gene flow contributes to diversification of the major fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Nat Commun 9(1):2253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith AC, Hickman MA (2020) Host-induced genome instability rapidly generates phenotypic variation across Candida albicans strains and ploidy states. mSphere. 10.1128/msphere.00433-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brennan M, Thomas DY, Whiteway M, Kavanagh K (2002) Correlation between virulence of Candida albicans mutants in mice and Galleria mellonella larvae. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 34(2):153–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Champion OL, Titball RW, Bates S (2018) Standardization of G mellonella Larvae to provide reliable and reproducible results in the study of fungal pathogens. J Fungi Basel Switz 4(3):108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moyes DL, Wilson D, Richardson JP, Mogavero S, Tang SX, Wernecke J et al (2016) Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature 532(7597):64–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mogavero S, Sauer FM, Brunke S, Allert S, Schulz D, Wisgott S et al (2021) Candidalysin delivery to the invasion pocket is critical for host epithelial damage induced by Candida albicans. Cell Microbiol 23(10):e13378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lemberg C, de San M, Vicente K, Fróis-Martins R, Altmeier S, Tran VDT, Mertens S et al (2022) Candida albicans commensalism in the oral mucosa is favoured by limited virulence and metabolic adaptation. PLoS Pathog 18(4):e1010012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fróis-Martins R, Lagler J, LeibundGut-Landmann S (2024) Candida albicans virulence traits in commensalism and disease. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep 11(4):231–240 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ost KS, O’Meara TR, Stephens WZ, Chiaro T, Zhou H, Penman J et al (2021) Adaptive immunity induces mutualism between commensal eukaryotes. Nature 596(7870):114–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tso GHW, Reales-Calderon JA, Tan ASM, Sem X, Le GTT, Tan TG et al (2018) Experimental evolution of a fungal pathogen into a gut symbiont. Science 362(6414):589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Witchley JN, Penumetcha P, Abon NV, Woolford CA, Mitchell AP, Noble SM (2019) Candida albicans morphogenesis programs control the balance between gut commensalism and invasive infection. Cell Host Microbe 25(3):432-443.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liang SH, Sircaik S, Dainis J, Kakade P, Penumutchu S, McDonough LD et al (2024) The hyphal-specific toxin candidalysin promotes fungal gut commensalism. Nature 627(8004):620–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McDonough LD, Mishra AA, Tosini N, Kakade P, Penumutchu S, Liang SH et al (2021) Candida albicans Isolates 529L and CHN1 Exhibit stable colonization of the murine gastrointestinal tract. MBio 12(6):e02878-e2921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fan D, Coughlin LA, Neubauer MM, Kim J, Kim M, Zhan X et al (2015) Activation of HIF-1α and LL-37 by commensal bacteria inhibits Candida albicans colonization. Nat Med 21(7):808–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pradhan A, Herrero-de-Dios C, Belmonte R, Budge S, Lopez Garcia A, Kolmogorova A et al (2017) Elevated catalase expression in a fungal pathogen is a double-edged sword of iron. PLOS Pathog 13(5):e1006405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brown AJP, Budge S, Kaloriti D, Tillmann A, Jacobsen MD, Yin Z et al (2014) Stress adaptation in a pathogenic fungus. J Exp Biol 217(1):144–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wheeler RT, Kombe D, Agarwala SD, Fink GR (2008) Dynamic, morphotype-specific candida albicans β-glucan exposure during infection and drug treatment. PLoS Pathog 4(12):e1000227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lopes JP, Stylianou M, Backman E, Holmberg S, Jass J, Claesson R et al (2018) Evasion of immune surveillance in low oxygen environments enhances Candida albicans virulence. MBio. 10.1128/mbio.02120-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shen J, Cowen LE, Griffin AM, Chan L, Köhler JR (2008) The Candida albicans pescadillo homolog is required for normal hypha-to-yeast morphogenesis and yeast proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105(52):20918–20923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fuchs BB, Eby J, Nobile CJ, El Khoury JB, Mitchell AP, Mylonakis E (2010) Role of filamentation in Galleria mellonella killing by Candida albicans. Microbes Infect Inst Pasteur 12(6):488–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Williams RB, Lorenz MC (2020) Multiple alternative carbon pathways combine to promote candida albicans stress resistance, immune interactions, and virulence. MBio 11(1):e03070-e3119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Molly K, Vande Woestyne M, Verstraete W (1993) Development of a 5-step multi-chamber reactor as a simulation of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 39(2):254–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ito T, Sekizuka T, Kishi N, Yamashita A, Kuroda M (2019) Conventional culture methods with commercially available media unveil the presence of novel culturable bacteria. Gut Microbes 10(1):77–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pearce SC, Coia HG, Karl JP, Pantoja-Feliciano IG, Zachos NC, Racicot K (2018) Intestinal in vitro and ex vivo Models to Study Host-Microbiome Interactions and Acute Stressors. Front Physiol 12(9):1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brown AJP, Brown GD, Netea MG, Gow NAR (2014) Metabolism impacts upon Candida immunogenicity and pathogenicity at multiple levels. Trends Microbiol 22(11):614–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]