Abstract

We report that POL5 encodes the fifth essential DNA polymerase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Pol5p was identified and purified from yeast cell extracts and is an aphidicolin-sensitive DNA polymerase that is stimulated by yeast proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Thus, we named Pol5p DNA polymerase φ. Temperature-sensitive pol5-1∼–3 mutants did not arrest at G2/M at the restrictive temperature. Furthermore, the polymerase active-site mutant POL5dn gene complements the lethality of Δpol5. These results suggest that the polymerase activity of Pol5p is not required for the in vivo function of Pol5p. rRNA synthesis was severely inhibited at the restrictive temperature in the temperature-sensitive pol5-3 mutant cells, suggesting that an essential function of Pol5p is rRNA synthesis. Pol5p is localized exclusively to the nucleolus and binds near or at the enhancer region of rRNA-encoding DNA repeating units.

DNA polymerases (Pols) play important cellular roles in DNA replication, repair, and recombination. Several distinct polymerases have been identified, purified, and characterized from prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, and these enzymes are classified into several distinct types (1–3). The best characterized eukaryotic polymerases are polymerases (Pols) α, β, δ, ɛ, and γ. Recent studies also identified prokaryotic and eukaryotic polymerases that perform translesion synthesis in the presence of DNA damage (3).

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pol α, δ, and ɛ are required for chromosomal DNA replication (4), and Pol σ is required for both chromosomal DNA replication and sister chromatid cohesion (5). Pol IV (β), Rev3 (Pol ζ), and Rad30 (Pol η) participate in DNA repair and/or recombination (6), and Polγ is the mitochondria DNA (4). The complete sequence of the yeast genome identified an ORF [YEL055C (POL5)] that encodes a polypeptide resembling B-type Pols. This study characterizes the ORF in YEL055C (POL5) and shows that it encodes the fifth essential Pol in S. cerevisiae. To investigate its function in vivo, several conditionally lethal mutants and a polymerase active-site mutant of POL5 were generated. These mutants were not defective in chromosomal DNA replication, and the polymerase active-site mutant gene fully complemented the lethality of a Δpol5 mutation. These results suggest that Pol5p plays an essential role in a cellular function other than chromosomal DNA replication.

The nucleolus is the subnuclear compartment in which most steps in the production of ribosomes occur, including synthesis of pre-rRNAs, pre-RNA processing and modification, and ribosome assembly. The nucleolus also plays roles in the synthesis of ribonucleoprotein particles and pre-tRNA processing (7). Subcellular localization studies showed that Pol5p exclusively colocalizes with Nop1p, which is a component of the C + D small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein-binding protein complex (8), in the nucleolus. Therefore, it is possible that Pol5p may perform an essential function in the nucleolus. This possibility is consistent with the phenotype of pol5-3 mutant cells, which demonstrate severe inhibition of rRNA synthesis at the restrictive temperature and have increasing copy numbers of rRNA-encoding DNA (rDNA) repeating unit on chromosome XII. Thus, Pol5p may be involved in regulating rRNA synthesis in the nucleolus.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Strains and Media.

Yeast strains used in this study are S. cerevisiae CB001 (9), W303D (MATa/α ura3-1/ura3-1 leu2-3, 112/leu2-3,112 his3-11/his3-11 trp1-1/trp1-1 ade2-1/ade2-1) (from R. Rothstein), W303-1A (MATa ade2-1 ura3-1 his3-11 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100) (R. Rothstein), DY150 (MATa ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ade2-1 his3-11 can1-100 (CLONTECH), YKS1 (MATa ura3 leu2 his3 trp1 ade2) (this study), YKS10 (MATa ura3 leu2 his3 trp1 ade2 Δpol5∷LEU2 [YCplac22-POL5] (this study), YKS11 (the same as YKS10 except for [YCplac22-pol5-1]), YKS12 (the same as YKS10 except for [YCplac22-pol5-2]), YKS13 (the same as YKS10 except for [YCplac22-pol5-3]), YKS14 (the same as YKS10 except for [YEplac195-POL5]), TAK201 (MATa ade2-1 ura3-1 his3-11 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 [pNOY102 fob1Δ∷HIS3][pNOY353]) (10), and Schizosaccharomyces pombe 972 (h−). All media used in this study were described previously (11). YPG contains 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% galactose.

Activity Gel Analysis of the POL5 Gene Product.

The region of the POL5 (YEL055C) gene was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′-CCATAGTCTAGACATCGTGG-3′ and 5′-GATTCTTCTAGAAGTGCAT-3′ (the underlined is the XbaI recognition sequence) and Taq Pol, digested with XbaI and cloned into the XbaI site of vector pYEUra3 DNA (CLONTECH). The resulting plasmid, pYEUra3-POL5 DNA, was used to transform yeast strain YKS1. The transforming YKS1 (pYEUra3-POL5) was grown in YPD (1% yeast extract/2% peptone/2% glucose) at 30°C to the density 1 × 107 cells per ml, centrifuged, washed with water twice, and resuspended in fresh YPG. Cells were grown at 30°C for 8 h and centrifuged, and protein extracts were prepared as described. The protein extracts were subjected to activity gel assay by using activated fish sperm DNA as described (11).

Disruption of the POL5 Gene.

The BstBI-BstBI interval of the POL5 gene was replaced with S. cerevisiae LEU2 and used to transform a diploid yeast strain W303D to Leu+ (W303D-Δpol5). Transformants were sporulated and dissected as described previously (12). More than 50 tetrads were dissected, and only two viable spores were detected in all cases that were all Leu+. Thus, it was concluded that POL5 is an essential gene as described previously (13).

Isolation of Temperature-Sensitive pol5 Mutants.

The diploid W303D-Δpol5 was transformed with YCplac33-POL5 (POL5 URA3), sporulated, and dissected. From dissected spores, a Ura+ Leu+ haploid (W303-1A Δpol5 [YCplac33-POL5]) was selected. POL5 was cloned into the YCplac22 (14) vector (YCplac22-POL5) and mutagenized by PCR using primers which both flanking vector sequences were amplified with POL5. The PCR-amplified DNA and a BamHI- and SalI-digested YCplac22 were cotransformed into W303-1A Δpol5 [YCplac33-POL5] to obtain YCplac22-pol5 mutants by in vivo recombination (15). Approximately 20,000 transformants grown at 25°C on SC [synthetic complete medium (12)]-Trp-Ura plates were isolated and replicated onto two sets of 5-fluoroorotic acid containing SC-Trp plates. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 25 or 37°C. Eight transformants were isolated that grew at 25°C but not at 37°C. In this study, we characterized three representative mutants, pol5-1∼–3.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Among type B Pols, the 626th and 628th Asp (D) residues of POL5 are well conserved, and these residues are known to be critical for Pol activity (16). We changed the 626th and 628th D residues of POL5 to Asn (N) residue by site-directed mutagenesis. The mutant gene was named POL5dn.

Purification of the Glutathione S-Transferase (GST)-Pol5p.

The POL5 gene was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′-TACCGGATCCACAGGGAAAGTCAACGAC-3′ (the BamHI site is underlined) and 5′-TAGTCTACCCCTCGAGGGAGGTC-3′ (the XhoI site is underlined). Amplified DNA was digested with BamHI and XhoI and ligated into pYEX4T-3 (CLONTECH) double-digested with BamHI and XhoI to form plasmid pYEX4T-POL5. This plasmid was used to transform DY150, and Ura+ Leu+ transformants were selected on SC-Ura-Leu plates. Yeast strain DY150 harboring pYEX4T-POL5 was grown in 6 liters of SC medium without uracil and leucine. GST-Pol5p was induced by CuSO4 as recommended by the manufacturer. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in buffer A (9), and disrupted with a bead beater as described (17). GST-Pol5p was affinity-purified by using a glutathione-Sepharose 4B column (Pharmacia Biotech) as described (18).

Purification of Pol5p from Yeast Cell Extracts.

One kilogram of yeast CB001 cells were lysed, the cell extracts were prepared and applied to an S-Sepharose (1 liter) column equilibrated with buffer A/100 mM NaCl, and the retained proteins were eluted with 1 liter of buffer A/500 mM NaCl as described (9). The eluted sample was dialyzed against buffer A/100 mM NaCl and reapplied to a Q-Sepharose column (200 ml) equilibrated with buffer A/100 mM NaCl, and the proteins were eluted with a linear NaCl gradient from 0.1 to 0.5 M NaCl in buffer A (1 liter). Fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with mouse antibody against GST-Pol5p. Pol5p eluted at ≈0.3 M NaCl. The Pol5p-containing fractions were pooled and purified further by Mono S, hydroxylapatite, heparin-Sepharose, and Mono Q column chromatographies (a more detailed purification protocol will be published). The purified Pol5p was 90% pure (Fig. 1E). We do not know whether other polypeptides coeluted with Pol5p and Pol activity are subunits of Pol5p complex.

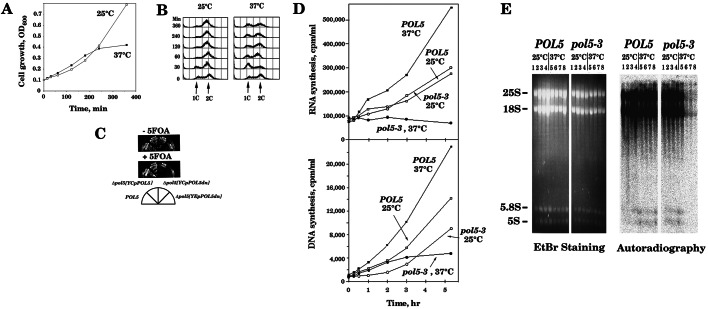

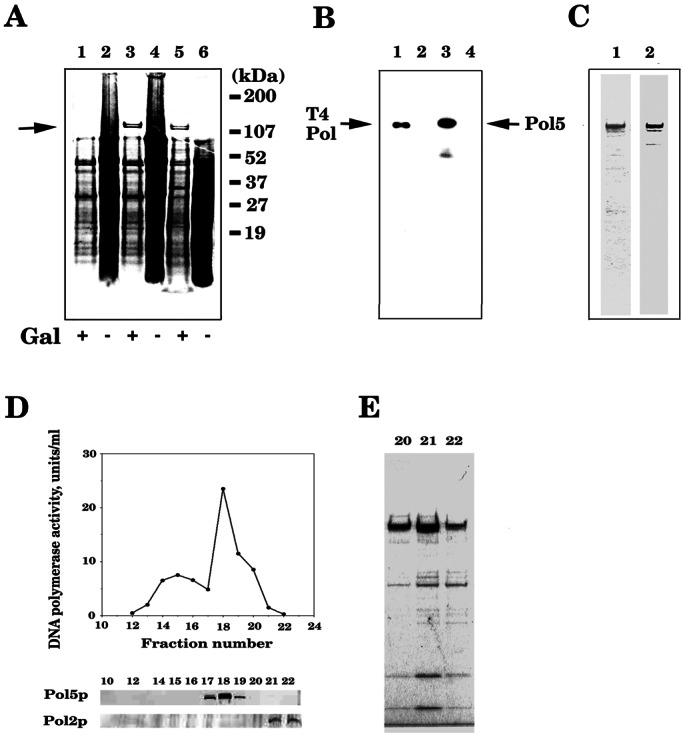

Figure 1.

Pol5p has Pol activity. Yeast YKS1 cells harboring pYEUra3-POL5 were grown in YGP, lysed, and analyzed by SDS/PAGE. (A) After SDS/PAGE, the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Lane 1, control vector, +galactose; lane 2, control vector, +glucose; lane 3, pYEUra3-POL5 DNA expression plasmid, +galactose; lane 4, pYEUra3-POL5 DNA, +glucose; lane 5, pYEUra3-POL5dn, +galactose; lane 6, pYEUra3-POL5dn, +glucose. (B) After SDS/PAGE, an in situ gel assay for Pol activity was carried out as published (9, 11). Lane 1, 10 units of T4 Pol; lane 2, pYEUra3-POL5 expression plasmid, +glucose; lane 3, pYEUra3-POL5 expression plasmid, +galactose; lane 4, pYEUra3-POL5dn, +galactose. (C) Recombinant GST-Pol5p was purified from DY150 containing pYEX4T-POL5 cells induced with CuSO4 and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting. Lane 1, Coomassie blue staining; lane 2, Western blot with mouse antiserum against GST-Pol5p. (D) Purification of Pol5p from yeast cells. The figure shows the Pol activity profile from Mono S column. The Pol active fractions were subjected to SDS/PAGE followed by Western blotting with mouse antiserum against GST-Pol5p or rabbit antiserum against the Polɛ complex. (E) Pol active fractions from the Mono Q column (lanes 20–22) were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Coomassie blue staining.

Assay for Pol Activity.

Pol activity was measured by using activated fish sperm DNA (GIBCO) or poly(dA)500⋅oligo(dT)10 (5:1, GIBCO) as DNA substrate. Reactions were performed at 30°C for 30 min as described (9, 11).

Indirect Immunofluorescence Microscopy.

Immunolocalization of the 9Myc-Pol5p and Nop1p was carried out as described (17). When the double-immunofluorescence assay was performed, monoclonal antibody B15 against Nop1p (19) and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Myc (Cell Signaling Technology) were used. Secondary antibodies were Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa 546-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes).

Sequencing of cDNA of S. pombe pol5+.

The S. pombe database was searched by using the BLAST algorithm. One sequence (c14C8) was identified that encodes a predicted protein with a high degree of similarity to Pol5p. The cDNA of this gene, pol5+, was isolated from S. pombe mRNA by using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and pol5+ was amplified by reverse transcription–PCR and sequenced by using an ABI Model 377 sequencer.

Other Methods and Materials.

S. cerevisiae Pol ɛ and Pol δ were purified to homogeneity by published methods (9, 20). S. cerevisiae proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was described previously (21). Mouse antibodies against GST-Pol5p were raised as described previously (9). RNA and DNA synthesis in wild-type and pol5 mutant cells was measured as described (22). Flow-cytometric analysis of yeast cells was carried out as described (23). Pulse-field agarose gel electrophoresis was carried out as published (24).

Results

The POL5 Gene Encodes an Aphidicolin-Sensitive Pol.

The yeast genome project identified an ORF, YEL055C, that has weak amino acid sequence homology to B-type Pols (25) and was named POL5. To confirm that POL5 encodes a previously uncharacterized Pol, the YEL055C was cloned into the expression vector pYEX4T-3 and overexpressed in yeast. Protein extracts were prepared from yeast cells overexpressing Pol5p and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and an in situ Pol activity assay. The overexpressed Pol5p had Pol activity by using this assay (Fig. 1 A and B). A Pol5p with mutation in the presumed active site also was prepared and analyzed by SDS/PAGE. This polypeptide (Pol5dn) had no DNA synthesis activity in the in situ assay (Fig. 1 A and B) or the normal Pol assay (Table 1). These results strongly suggest that POL5 encodes a polypeptide that has Pol activity in vitro. GST-Pol5p also was overexpressed and affinity-purified by using a glutathione-Sepharose 4B column and analyzed by SDS/PAGE. As shown in Fig. 1C, the purified protein has a single band of molecular weight ≈140,000 and has a significant level of DNA polymerization activity (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1D, native Pol5p Pol was purified also from yeast cell extracts by conventional column chromatography. Western blot experiments indicate that the purified polypeptide was reacted strongly with mouse antiserum against the GST-Pol5p but does not cross-react with antibodies to other yeast Pols including Pol2p (Pol ɛ, Fig. 1D), Pol α, Pol δ, and Pol β (data not shown). Thus, the product of the S. cerevisiae POL5 was named Pol φ.

Table 1.

DNA polymerase φ activity is stimulated by yeast PCNA

| DNA polymerase | PCNA addition | DNA

synthesis*

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| −Aphidicolin, pmol (fold stimulation) | +Aphidicolin, pmol | ||

| GST-Pol5p | − | 2.5 (1) | 0.5 |

| GST-Pol5p | + | 12.1 (4.8) | 1.3 |

| Polφ | − | 7.0 (1) | 0.4 |

| Polφ | + | 40.0 (5.7) | 1.3 |

| Pol5dn† | − | 0.1 (1) | 0.1 |

| Pol5dn | + | 0.1 (1) | 0.12 |

| Polδ | − | 27.1 (1) | 1.4 |

| Polδ | + | 163.0 (6.0) | 2.1 |

| Polɛ | − | 35.2 (1) | 0.8 |

| Polɛ | + | 40.2 (1.1) | 0.9 |

DNA synthesis was measured in the presence of poly(dA)500⋅oligo(dT)10 (5:1) as a template-primer.

Because the purity of the Pol5dn polypeptide was not the same as that of Polφ, the concentration of Pol5dn was estimated by Western blot using mouse polyclonal antibodies against GST-Pol5p, and the same amount of Pol5dn as Polφ was used for the DNA polymerase assay.

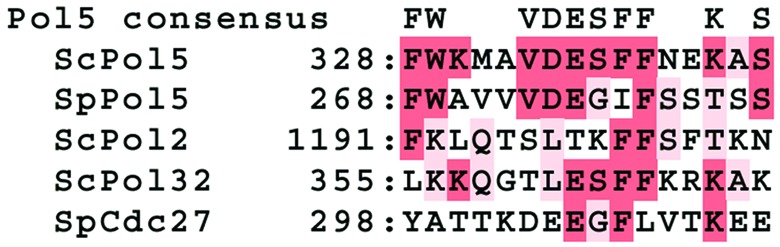

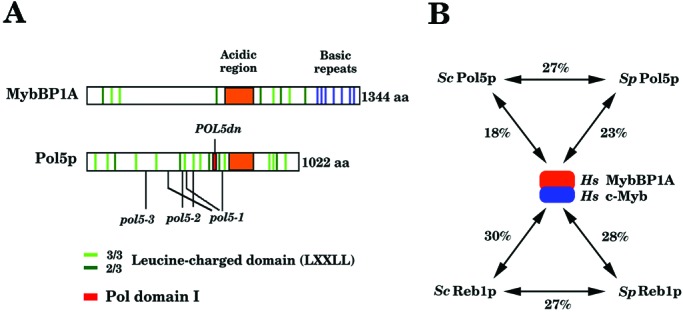

The amino acid sequence of POL5 was aligned with B-type Pols in S. cerevisiae (Pol α, Pol ɛ, Pol δ, and Pol ζ). Pol φ contains the six Pol domains (I–VI) that are present in all B-type Pols. In addition, the conserved polymerase domains in Pol φ are colinear with other B-type polymerase domains, and there is a Pol signature sequence GDTDS in region I. A PCNA-binding motif also is present from amino acids 328 to 343 in Pol φ (Fig. 2). A similar motif is found in S. cerevisiae Pol32p (ScPol32p), ScPol2p, S. pombe Cdc27p (SpCdc27p), and SpPol5p (Fig. 2). This observation is consistent with the fact that Pol activities of purified Pol φ and GST-Pol5p were stimulated several-fold by yeast PCNA, and these activities were almost completely inhibited by 5 μg/ml aphidicolin (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 3, POL5 also exhibits a weak similarity to human Myb-binding protein (MybBP1A; ref. 26), which physically interacts with c-Myb and may play a role in transactivation by Myb (27). POL5 also contains an acidic region and leucine-charged domains (LXXLL) found in MybBP1A (Fig. 3). However, MybBP1A does not have any Pol domains found in POL5.

Figure 2.

Putative PCNA-binding consensus sequences in Pol5p. The region between residues 328 and 343 of S. cerevisiae Pol5p (ScPol5p) has high homology to one of the PCNA-binding domains in ScPol32p. The figure shows the amino acid sequences of ScPol5p, SpPol5p, ScPol32p, and ScCdc7p (Pol5 consensus). The red-colored shaded amino acids are identical amino acid residues.

Figure 3.

(A) S. cerevisiae Pol5p has the six Pol domains that are conserved among B-type Pols. It also has the acidic region (orange color) and many leucine-charged domains (light green and dark green) found in human MybBP1A. Shown is one of six Pol domains (domain I) that are most conserved among B-type Pols (a red square) and the mutation sites found in pol5-1∼–3 mutants in Pol5p. (B) Amino acid sequence similarity between ScPol5p, SpPol5p, and human MybBP1A (Hs MybBP1A) and between ScReb1p, SpReb1p, and human c-Myb (Hs c-Myb). It is known that Hs MybBP1A physically interacts with Hs c-Myb.

The S. pombe sequence database was searched by using the BLAST algorithm, and one amino acid sequence (c14C8) was identified that has a high degree of similarity to the Pol5p. This gene, pol5+, is presumed to be the S. pombe homologue of Pol5p. The pol5+ cDNA was isolated and sequenced by using reverse transcription–PCR (the DDBJ accession number for cDNA of pol5+ is AB012696). This gene has a small intron, and the predicted amino acid sequence of pol5+ has extensive similarity to S. cerevisiae Pol5p. Furthermore, S. pombe pol5+ has six conserved Pol domains present in B-type Pols (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org), which suggests that S. pombe pol5+ is the structural and functional homologue of S. cerevisiae POL5.

Pol5p Is Essential for Cell Growth but Does Not Participate in Chromosomal DNA Replication.

Previous studies indicate that the POL5 gene is essential for cell growth in yeast (13). To investigate cellular function of POL5, several temperature-sensitive mutants of POL5 were isolated by using plasmid-shuffling methods (28). Three mutants with mutations in the coding region of POL5, pol5-1, pol5-2, and pol5-3, were characterized in this study. The pol5-3 mutant has a single-amino acid change [Trp (W) at amino acid 292 to Lys (R)], and the pol5-1 and pol5-2 mutants have three [Val (V) at amino acid 404 to Met (M), Lys at 491 to Glu (E), and Gln (Q) 671 to Pro (P)] and two [Leu (L) at 466 to Ser (S) and L at 594 to S] amino acid changes, respectively (Fig. 3). The multiple mutations could not be separated from the temperature-sensitive growth phenotype of pol5-1 or pol5-2, indicating that those mutations are required for the temperature-sensitive phenotype. However, none of these three temperature-sensitive pol5-1∼–3 mutants has a temperature-sensitive Pol φ activity (data not shown). Nevertheless, these conditional pol5 mutants were used to investigate whether Pol φ is required for chromosomal DNA replication. The representative mutant, pol5-3, was grown at the permissive temperature (25°C), shifted to the restrictive temperature (37°C), and analyzed by FACScan at time points after the temperature shift. Mutant cells did not arrest at a specific phase of the cell cycle at the restrictive temperature, although growth of the mutant cells was inhibited severely at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 4 A and B). And, the terminal morphology of the mutant cells after 6 h at the restrictive temperature was very different from DNA-replication mutants, which arrest at G2/M (data not shown). Furthermore, the POL5dn encoding a Pol5p that has no detectable Pol activity (Fig. 1 and Table 1) complemented the lethality of Δpol5 as POL5 (Fig. 4C). All these results strongly suggest that the polymerase activity of Pol φ is not required for chromosomal DNA replication. The temperature-sensitive pol5 mutants also were tested for sensitivity to DNA damage at semipermissive or permissive temperatures. All mutants demonstrated no hypersensitivity to hydroxyurea, methyl methane sulfonate, or UV- or γ-ray irradiation at 25, 30, or 33°C (data not shown), suggesting that Pol φ is not involved in either DNA repair and/or recombination.

Figure 4.

Pol5p is required for rRNA synthesis but not for chromosomal DNA replication. YSK13 (pol5-3) cells were grown in SD-complete without tryptophan at 25°C to ≈1 × 106 cells per ml. The culture was divided into two portions and incubated at 25 and 37°C, respectively. Aliquots were analyzed for cell growth (A) or FACScan analysis (B). (C) YSK14 harboring YEplac195-POL5 was transformed by YCplac22-POL5dn and grown on either YPD- or SD-complete tryptophan plate with 5-fluoroorotic acid at 25°C for 4 days. When YEplac195-POL5 plasmid was removed from the strain (+5-fluoroorotic acid), YSK14 (Δpol5) harboring YCplac22-POL5dn was able to grow. (D) YSK10 (POL5) and YSK13 (pol5-3) cells were grown in 50 ml of SD complete without tryptophan to ≈1 × 106 cells per ml at 25°C. [3H]uridine [250 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq)] was added to the culture, and incubation continued for 60 min. Then the culture was divided into two equal portions, which were incubated at 25 or 37°C. Aliquots were withdrawn for analysis of 3H-labeled RNA and DNA (24). (E) YSK10 (POL5) and YSK13 (pol5-3) mutant cells were grown in 50 ml of SD complete without tryptophan to ≈5 × 106 cells per ml at 25°C and divided into two equal portions, which were incubated at 25 or 37°C. For a control, cells were pulse-labeled for 15 min before temperature-shift up. At 30, 60, and 120 min after temperature shift, cells were pulse-labeled with 30 μCi/ml of [3H]uridine for 15 min, and total RNA was extracted (35) and analyzed by 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and photographed (EtBr Staining). The labeled RNA was transferred onto nitrocellulose and autoradiographed by using a Fuji imaging plate for 8 days (Autoradiography). Lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4 are RNA from either wild-type (POL5) or pol5-3 mutant cells pulse-labeled with [3H]uridine for 15 min at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min, respectively, after being grown at 25°C. Lanes 5, 6, 7, and 8 are RNA from either POL5 or pol5-3 mutant cells pulse-labeled with [3H]uridine for 15 min at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min, respectively, after temperature shift to 37°C.

Pol5p Is Involved in Regulating Synthesis of rRNA.

A weak similarity of Pol5p to human MybBP1A protein (Fig. 3) prompted us to examine rRNA synthesis in temperature-sensitive pol5-3 mutant cells by two different ways. One is that total RNA was labeled continuously with [3H]uridine before and after temperature shift to 37°C. The other is that mutant cells were pulse-labeled with [3H]uridine at various times after temperature shift to 37°C. From these two experiments, we obtained the following results. (i) Incorporation of [3H]uridine to RNA was severely inhibited immediately after temperature shift to 37°C (Fig. 4D). In contrast, cell growth (Fig. 4A), DNA synthesis (Fig. 4D), and protein synthesis (data not shown) continued for 2 or 3 h after temperature shift and then leveled off in the mutant. (ii) RNA labeled with [3H]uridine for 60 min at 25°C in the mutant was not degraded significantly after temperature shift to 37°C at least for 3 h (Fig. 4D). (iii) rRNA (25S, 18S, 5.8S, and 5S RNA) but not tRNA (data not shown) was not pulse-labeled with [3H]uridine after temperature shift to 37°C in the mutant (Fig. 4E). (iv) No significant amount of pre-rRNA was accumulated in the mutant after temperature shift to 37°C (Fig. 4E). Altogether, these results strongly suggest that the pol5-3 mutation has a primary defect in rRNA synthesis but is proficient in DNA and protein synthesis.

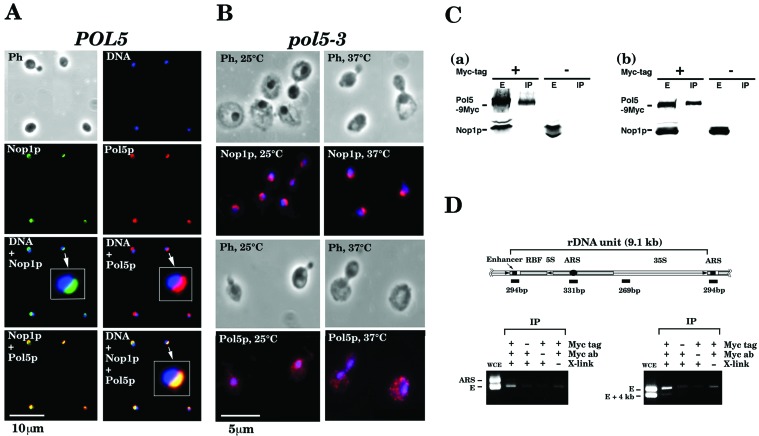

Pol5p Is Localized Exclusively in the Nucleolus.

Logarithmically growing yeast cells expressing 9Myc-tagged Pol5p were harvested, fixed, stained with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Myc and mouse monoclonal antibody against Nop1p, which was used as a marker for the nucleolus (8), and observed by a fluorescence microscope. As shown in Fig. 5A, Pol5p exclusively localizes in the nucleus, exhibiting the characteristic crescent-like shape, and colocalizes with Nop1p. These results strongly suggest that virtually all Pol5p colocalizes with Nop1p in the nucleolus. Pol5p was detected on every nuclei (Fig. 5A) from logarithmically growing cells, suggesting that the localization of Pol5p does not change during the cell cycle. The localization of Pol5p and Nop1p also was investigated in the pol5-3 mutant cells grown at 25°C and shifted to 37°C. The localization of Nop1p was not changed significantly before and after temperature shift to 37°C in pol5-3 as in POL5 cells (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, although the localization of Pol5p in mutant cells grown at 25°C was mainly in the nucleus as that in wild-type cells, the characteristic crescent-like shape was observed no more (Fig. 5B). At 37°C, Pol5p was dispersed completely in the cell and was seen as punctate foci in cytoplasm (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Pol5p is localized exclusively in the nucleolus. (A) Yeast W303-1A cells expressing 9Myc-tagged Pol5p were grown in 10 ml of YPD, harvested by centrifugation, and fixed with formaldehyde, and Pol5p and Nop1p were stained with monoclonal antibody to Myc or Nop1p. Ph, photograph of cells; DNA, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained nuclei; Pol5p and Nop1p, fluorescence images from immunoreaction with Myc and Nop1p antibodies, respectively. Nop1p + DNA, Pol5p + DNA, Pol5p + Nop1p, and Pol5p + Nop1p + DNA are the merged images of Pol5p and DNA, Pol5p and Nop1p, Nop1p and DNA, and Pol5p, Nop1p, and DNA, respectively. An arrow indicates ×5-enlarged image. (B) YSK13 (pol5-3) cells expressing 9Myc-tagged pol5-3 were grown at 25°C and divided to two equal portions, and each was incubated at 25 or 37°C for another 2 h. Then, cells were fixed and stained with DAPI and Myc or Nop1p antibody as described for A. Photograph of cells (Ph) or the merged image of DAPI (blue) and Myc or Nop1p monoclonal antibody staining (red) is shown. (C) Pol5p does not interact physically with Nop1p in the nucleolus. Yeast W303-1A cells expressing 9Myc-tagged Pol5p were grown in 100 ml of YPD, harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended in 5 ml of the lysis buffer. Protein extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation by using anti-Myc monoclonal antibody as described (27). The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc and anti-Nop1p monoclonal antibodies. As a control, no Myc-tagged W303-1A cell extracts were used. (a) Protein extracts prepared from W303-1A cells expressing 9Myc-tagged Pol5p without treatment of the dithiobis (succinimidylpropionate) (DSP) cross-linker. (b) Protein extracts from W303-1A cells expressing 9Myc-tagged Pol5p with treatment of DSP prior to protein extraction. E and IP, whole extracts and immunoprecipitates by anti-Myc monoclonal antibody, respectively; + and −, protein extracts from cells expressing 9Myc-tagged Pol5p and those from non-tagged cells, respectively. (D) Pol5p may bind on/near the enhancer sequence located in the rDNA repeating unit. Yeast W303-1A cells expressing 9Myc-tagged Pol5p were grown in 100 ml of YPD medium, fixed with formaldehyde, harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended in 5 ml of the lysis buffer. Protein extracts were prepared, sonicated, and subjected to immunoprecipitation by using anti-Myc polyclonal antibodies. DNA was extracted from the immunoprecipitates and amplified by PCR using specific primer sets for the enhancer region (E, 294 bp), autonomously replicating sequence region (ARS, 331 bp), and ≈4 kb away from the enhancer sequence (E + 4 kb, 269 bp). The DNA fragments amplified were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. WCE, DNA from whole-cell extracts; + and −, with and without Myc tag or formaldehyde cross-linking, respectively. (D Upper) Schematic representation of the structure of the rDNA repeating unit of yeast chromosomal DNA.

Pol5p Does Not Interact Physically with Nop1p.

Protein extracts were prepared from yeast cells expressing Myc-tagged Pol5p, immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody, and immunoblotted with anti-Myc or anti-Nop1p monoclonal antibodies. This experiment was carried out with or without treating cells with the cross-linking agent dithiobis (succinimidylpropionate) (23) before extract preparation. As shown in Fig. 5C, most of the Myc-tagged Pol5p was precipitated by anti-Myc monoclonal antibody, but no Nop1p was detected in the immunoprecipitates with or without dithiobis (succinimidylpropionate) treatment. Thus, we conclude that Pol5p does not interact directly with Nop1p in the nucleolus, although immunocytological study shows that Pol5p and Nop1p colocalize in the nucleolus (Fig. 5A).

Pol5p Binds Near or At the Enhancer Region of rDNA Repeating Units.

Logarithmically growing yeast cells expressing Myc-tagged Pol5p were fixed with or without formaldehyde and harvested. Chromatin fractions from these cells were sonicated and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc antibodies. Then, DNA was extracted from the immunoprecipitates and analyzed by PCR to determine the relative abundance of specific sequences bound to the immunoprecipitated Myc-tagged Pol5p (29). As shown in Fig. 5D, the DNA segment containing the yeast RNA polymerase I enhancer sequence in the rDNA repeating unit was specifically amplified, suggesting that Pol5p binds near or at the enhancer region of rDNA repeating units. S. cerevisiae has Reb1p, which is known as an rDNA enhancer-binding protein (30), a termination factor for RNA polymerase I (31), and a transcription factor for RNA polymerase II (32). Reb1p can be a homologue of human c-Myb (Fig. 3). Thus, it would be possible that Pol5p may interact physically with Reb1p and regulate the transcription of rDNA repeats in the nucleolus. However, thus far we could not detect any interaction between Reb1 and Pol5p by immunoprecipitation (data not shown).

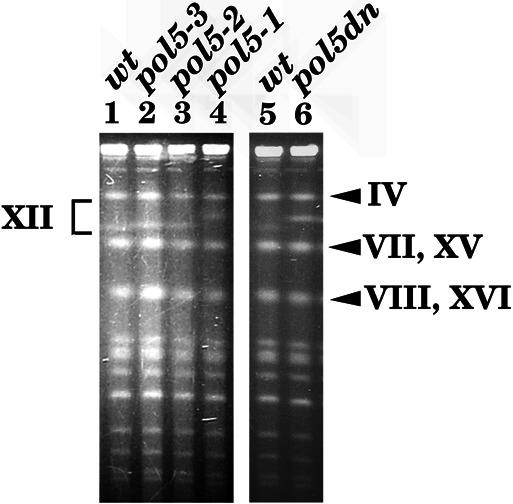

A Copy Number of rDNA Repeating Unit Increases in pol5 Mutant Cells.

A wild-type strain, temperature-sensitive pol5 mutants (pol5-1∼ –3), and the Δpol5 strain containing YEplac195-POL5dn plasmid were grown at 25°C, and their chromosomal DNA was extracted and analyzed by pulse-field agarose gel electrophoresis. As shown in Fig. 6, the migration of chromosome XII was retarded significantly in temperature-sensitive pol5 mutants. Interestingly, the apparent size of chromosome XII in the POL5dn strain also was significantly larger than that of wild-type cells. Although the POL5dn gene complements the lethality of Δpol5, the Δpol5 strain having POL5dn has a slight growth defect at 25°C (data not shown). Because chromosome XII contains many copies of rDNA repeats, we estimated a copy number of rDNA repeating unit as published (10). The results indicated that rDNA copy numbers for wild-type (W303-1A), pol5-1, pol5-2, pol5-3, and pol5dn strains are 55, 70, 75, 150, and 160 copies, respectively (data not shown). Therefore, we concluded that slow migrating chromosome XII in pol5 mutant cells is primarily caused by increasing copy numbers of rDNA repeating unit. These results suggest that Pol5p is involved in regulating the copy number of rDNA repeat.

Figure 6.

The size of chromosome XII increases in pol5 mutants. Wild-type (wt, W303-1A), temperature-sensitive pol5-1∼–3 mutants, and the Δpol5 strain containing the POL5dn gene (pol5dn) were grown at 25°C, and their chromosomal DNA was extracted and subjected to pulse-field agarose gel electrophoresis as published (14, 28). DNA was strained with ethidium bromide and photographed. Roman numbers indicate the chromosome number of S. cerevisiae.

Discussion

A previous study demonstrated that Pol5p is essential for yeast cell growth (13). Therefore, it was predicted that Pol5p would play an essential role in chromosomal DNA replication. However, the data presented here contradict that hypothesis. A mutant of Pol5p (POL5dn) was constructed with mutations in the Pol active site that encodes a polypeptide that has no detectable Pol activity (Fig. 1 and Table 1). This mutant gene complements the lethality of Δpol5 as POL5 (Fig. 4C), indicating that the polymerase activity of Pol φ is not required for its essential function in vivo. In addition, the terminal phenotype of several temperature-sensitive pol5 mutants, which have no temperature-sensitive Pol φ activity, indicates that these mutant cells do not arrest at a specific phase of cell cycle and do not exhibit the terminal cell-morphology characteristic of DNA-replication mutants (i.e., dumbbell shape).

The data presented in this study suggest that Pol φ is required for rRNA synthesis. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that Pol φ functions in pre-rRNA processing or in the formation of mature ribosomes, it is less likely because we could not see any significant accumulation of pre-rRNA molecules in mutant cells at the restrictive temperature by pulse-labeling (Fig. 4E). In the pol5-3 mutant, RNA labeled for 60 min at the permissive temperature was shown to be stable at the restrictive temperature for at least 3 h, although total rRNA was reduced gradually (Fig. 4 D and E), which suggests that rapid RNA degradation does not explain the immediate inhibition of rRNA synthesis at the restrictive temperature. Because Pol φ purified from yeast cell extracts has no detectable RNA polymerase activity (data not shown), it is unlikely that Pol φ is another RNA polymerase for rRNA synthesis. Cytological studies localize Pol5p to the nucleolus, which is the localization site of Nop1p, a component of the C + D small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein-binding protein complex. However, no direct physical interaction between Pol5p and Nop1p was detected by immunoprecipitation with or without a cross-linking reagent (Fig. 5C). Thus, it is not likely that Pol5p is a component of the pre-rRNA-processing complex. Consistent with this notion, the localization of Nop1p was not changed significantly before and after temperature shift to 37°C in pol5-3 mutant cells, whereas the localization of Pol5p was changed aberrantly in mutant cells at 37°C (Fig. 5B).

It is possible that Pol5p may be a promoter-binding protein for rRNA transcription and may regulate transcription from rDNA repeats in the nucleolus. S. cerevisiae has Reb1p, which can be a homologue of human c-Myb (Fig. 3). Although we could not detect any direct interaction between Pol5p and Reb1p, it would be possible that Pol5p and Reb1p may coordinately regulate the transcription of rDNA repeats in the nucleolus. Consistent with this result, it was shown that the DNA segment containing the yeast RNA polymerase I enhancer sequence in rDNA repeating unit was specifically amplified by a chromatin-immunoprecipitation assay, suggesting that Pol5p binds near or at the enhancer region of rDNA repeating units.

In S. cerevisiae, stable RNA (rRNA and tRNA) is synthesized by RNA polymerases I and III; however, RNA polymerase II can substitute for RNA polymerase I under certain conditions (33). Thus, we tested whether transcription of rDNA repeats by RNA polymerase II suppresses either the temperature sensitivity of pol5-3 mutant or lethality of Δpol5 after transformation with the same plasmid that Nogi et al. used (33). However, no suppression was observed. Thus, Pol5p may play another unknown function in rRNA synthesis.

As shown in Fig. 6, repeat numbers of rDNA are changed in various pol5 mutants. The repeat number seems to be maintained at an appropriate level for S. cerevisiae. However, variations of the repeat numbers were observed quite often, and most organisms seem to have the ability to alter repeat numbers in response to changes in intra- as well as extracellular conditions (10). Thus, we speculate that increasing numbers of rDNA repeating unit would be a compensatory effect of the decreasing ability of rRNA synthesis in pol5 mutants.

Causton et al. (34) recently examined genome-wide expression in yeast cells challenged with different types of environmental stress and showed that POL5 is one of 283 genes that is corepressed under seven stress conditions, some of which encode transcription or protein synthesis factors or ribosome proteins, which is consistent with our observation that virtually no rRNA synthesis was observed in pol5-3 mutant cells after temperature shift to 37°C (Fig. 4).

Why is Pol φ localized to the nucleolus? Does the polymerase activity of Pol φ function in cellular processing of nucleic acids? The nucleolus is the site at which repeated rDNA is synthesized also. Thus, it is still possible that Pol φ may participate in replication of rDNA repeats, amplification of rDNA copies, or repair of the rDNA region. Temperature-sensitive pol5 mutants are not hypersensitive to hydroxyurea, methyl methane sulfonate, or UV- or γ-ray irradiation. However, these results do not exclude the possibility that Pol5p is required for DNA repair and/or recombination, because other polymerases may substitute for Pol5p in this role.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Area (A) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan and by the Human Frontier Scientific Program (to A.S.).

Abbreviations

- Pol

DNA polymerase

- rDNA

rRNA-encoding DNA

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) database (accession no. AB012696).

References

- 1.Huang Y-P, Ito J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5300–5309. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.23.5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind L, Koonin E V. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1609–1615. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.7.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedberg E C, Feaver W J, Gerlach V L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5681–5683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120152397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawasaki Y, Sugino A. Mol Cells. 2001;12:277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carson D R, Christman M F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8270–8275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131022798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Washington M T, Johnson R E, Prakash L, Prakash S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8355–8360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121007298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pederson T. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3871–3876. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.17.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schimmang T, Tollervey D, Kern H, Frank R, Hurt E C. EMBO J. 1989;17:3747–3759. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamatake R K, Hasegawa H, Bebenek K, Kunkel T A, Sugino A. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4072–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi T, Nomura M, Horiuchi T. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:136–147. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.136-147.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu K, Santocanale C, Ropp P A, Longhese M P, Plevani P, Lucchini G, Sugino A. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:27148–27153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison A, Araki H, Clark A B, Hamatake R K, Sugino A. Cell. 1990;62:1143–1151. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90391-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winzeler E A, Shoemaker D D, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, Bangham R, Benito R, Boeke J D, Bussey H, et al. Science. 1999;286:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gietz D R, Sugino A. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muhlrad D, Hunter R, Parker R. Yeast. 1992;8:79–82. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorsky D I, Crumpacker C S. J Virol. 1990;64:1394–1397. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1394-1397.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawasaki Y, Hiraga H, Sugino A. Genes Cells. 2000;5:975–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gautier T, Berge T, Tollervey D, Hurt E. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7088–7098. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aris J P, Blobel G. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:17–31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerik K J, Li X, Pautz A, Burgers P M J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19747–19755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashimoto K, Ohara T, Maki S, Sugino A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:477–485. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eberly S L, Sakai A, Sugino A. Yeast. 1989;5:117–129. doi: 10.1002/yea.320050207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masumoto H, Sugino A, Araki H. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2809–2817. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2809-2817.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugimoto K, Shimomura T, Hashimoto K, Araki H, Sugino A, Matsumoto K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7048–7052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith V, Chou K N, Lashkari D, Botstein D, Brown P O. Science. 1996;274:2069–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keough R, Woollatt E, Drawford J, Sutherland G R, Plummer S, Casey G, Gonda T J. Genomics. 1999;62:483–489. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tavner F J, Simpson R, Tashiro S, Favier D, Jenkins N A, Gilbert D J, Copeland N G, Macmillan E M, Lutwyche J, Keough R A, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:989–1002. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Araki H, Hamatake R K, Johnston L H, Sugino A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4601–4605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strahl-Bolsinger S, Hecht A, Luo K, Grunstein M. Genes Dev. 1997;11:83–93. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrow B E, Johnson S P, Warner J R. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:9061–9068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang W H, Reeder R H. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:649–658. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Remacle J E, Holmberg S. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5516–5526. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nogi Y, Yano R, Nomura M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3962–3966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Causton H C, Ren B, Koh S-S, Harbison C T, Kanin E, Jennings E G, Lee T I, True H L, Lander E S, Young R A. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:323–337. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitt M E, Brown T A, Trumpower B L. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3091–3092. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.10.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.