Abstract

GbaSM-4 cells, smooth muscle cells derived from brain basilar artery, which express both 210-kDa long and 130-kDa short isoforms of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), were infected with an adenovirus vector carrying a 1.4-kb catalytic portion of MLCK–cDNA in an antisense orientation. Western blot analysis showed that the expression of short MLCK was depressed without affecting long MLCK expression. The contraction of the down-regulated cells was measured by the cell-populated collagen-fiber method. The tension development after stimulation with norepinephrine or A23187 was depressed. The additional infection of the down-regulated cells with the adenovirus construct containing the same insert in a sense direction rescued not only the short MLCK expression but also contraction, confirming the physiological role of short MLCK in the contraction. To examine the role of long MLCK in the residual contraction persisting in the short MLCK-deficient cells, long MLCK was further down-regulated by increasing the multiplicity of infection of the antisense construct. The additional down-regulation of long MLCK expression, however, did not alter the residual contraction, ruling out the involvement of long MLCK in the contractile activity. Further, in the cells where short MLCK was down-regulated specifically, the extent of phosphorylation of 20-kDa myosin light chain (MLC20) after the agonist stimulation was not affected. This finding suggests that there are additional factors to MLC20 phosphorylation that contribute to regulate smooth muscle contraction.

Myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) phosphorylates the 20-kDa light chain of smooth muscle myosin (MLC20) in the presence of Ca2+ and calmodulin (reviewed in ref. 1). The kinase activity is exerted through the catalytic domain located in the central part of MLCK. The N-terminal portion of MLCK acts as an actin-binding domain, where the amino acids responsible for the binding have been sequenced (2, 3). The C terminus of MLCK consists of a domain called telokin, which is expressed in smooth muscle cells as an independent gene product (4, 5). Because telokin binds myosin (6), the C terminus of MLCK is considered to be a myosin-binding domain (7). Isoforms of the enzyme are high molecular weight (long MLCK) and low molecular weight (short MLCK) kinases with molecular masses of ≈210 and ≈130 kDa, respectively. The short MLCK is best known as the conventional smooth muscle MLCK. However, the long MLCK, which is additionally furnished with 922–934 residues at the N terminus of the short MLCK (8), is poorly characterized (reviewed in ref. 9).

Smooth muscle myosin phosphorylated by the catalytic domain of MLCK is in an active form and interacts with actin filaments. This mode of regulation is widely accepted as the intracellular path for the induction of smooth muscle contraction (reviewed in ref. 10). However, several observations of smooth muscle contraction cannot be explained by the mode of phosphorylation (reviewed in ref. 11). For example, when uterine smooth muscle was subjected to prolonged incubation in Ca2+-free medium, oxytocin was able to induce contraction of the muscle without any signs of MLC20 phosphorylation (12). Obviously, an alternative regulation system must play an active role. In the search for this system, we were interested in the actin- and myosin-binding properties of MLCK and expressed the N-terminal (2) and C-terminal (13) portions of MLCK as recombinant proteins. They were tested for a regulatory role in terms of the ability to modify the actin–myosin interaction in vitro. We obtained positive answers (reviewed in ref. 14), even though they are devoid of the catalytic domain.

As the first step to examine whether our observations in vitro are related to a physiological role in regulating actual contraction of smooth muscle, we tried to obtain smooth muscle cells that are devoid of MLCK expression by introducing into them an antisense cDNA of MLCK (15). The effect of down-regulation of MLCK was tested by chemotaxis of smooth muscle cells, an assay that is based on cellular motility.

In the present study, collagen gels populated by smooth muscle cells in culture were used to detect the isometric contraction on stimulation with agonists (16). We observed a depressed contraction in the cells in which short MLCK was selectively down-regulated. However, the depression was not associated with changes in MLC20 phosphorylation—i.e., MLC20 was phosphorylated as well as MLC20 in control cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Isolation and Culture.

Smooth muscle cells were isolated from the basilar artery of guinea pigs as described for guinea pig stomach (16). The smooth muscle cells were grown on the surface of plastic dishes in DMEM of high glucose containing 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin supplemented with 10% FBS. One of the smooth muscle cells cultured in a low density was isolated by using cloning rings was named GbaSM-4 and used for the experiments.

Adenovirus Construction and Purification.

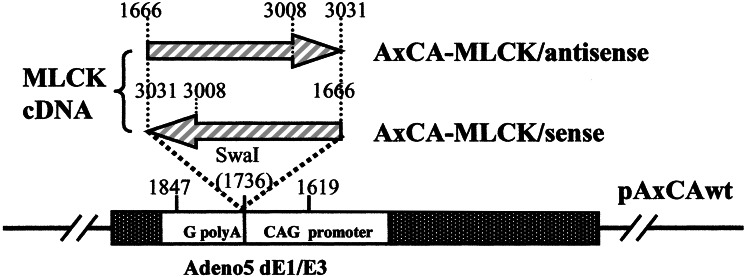

The 1,366-bp MLCK–cDNA corresponding to bp 1666–3031 of cDNA encoding rabbit smooth muscle MLCK (17) was isolated from pBst/SM3-FL by PCR as described (15). This fragment was then inserted into a cosmid vector pAxCAwt (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan) derived from adenovirus stereotype 5 with the E1 and E3 regions deleted at the SwaI site (Fig. 1). The sense and antisense orientation of the insert were confirmed by the nucleotide sequencing with Model 371 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Recombinant adenoviruses containing the inserts were constructed by the COS/TPC (terminal protein complex) method (18) using an adenovirus expression vector kit (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto). The obtained viruses bearing the sense MLCK–cDNA and the antisense MLCK–cDNA are reffered to as AxCA–MLCK/sense and AxCA–MLCK/antisense, respectively. As controls, AxCA-stuffer, an adenoviral recombinant containing 450 bp of nonsense cDNA, and AxCA–NLacZ, a vector expressing bacterial β-galactosidase tagged with a nuclear localization signal, were also used.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of construction of the recombinant adenovirus vectors. We obtained adenoviral recombinants bearing a rabbit smooth muscle MLCK–cDNA fragment coding 1666–3031 bp in a sense or antisense orientation by COS/TPC method (18) and named then AxCA–MLCK/antisense and AxCA–MLCK/sense, respectively.

Partial Sequence of MLCK from GbaSM-4 Cells.

Total RNA from GbaSM-4 cells was prepared by using RNeasy Max kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and poly(A)-rich RNA was purified with QuickPrep mRNA purification kit (Amersham Pharmacia). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized by priming with oligo(dT) using Thermoscript reverse transcription (RT)-PCR system (Invitorogen), and the MLCK–cDNA fragment was amplified with Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche). Two degenerated, oppositely oriented oligonucleotides were designed as PCR primers by deducing their nucleotide sequences from the amino acid sequences in two highly conserved regions of a variety of MLCKs. The PCR product was subcloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega), and its sequence was determined with BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing FS kit (Applied Biosystems). The identity of the nucleotide sequence of the cDNA introduced into the cells was 87% as compared with the rabbit smooth muscle MLCK gene. Such a high identity might enable the down-regulation despite the species difference. The nucleotide sequence was deposited in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession number AB070227.

Transduction of Adenoviral Vectors into Cells.

Cultured GbaSM-4 cells at ≈70% confluence were exposed to respective adenoviral vectors in 100 multiplicity of infection (moi) for 1 h unless otherwise stated. The viruses were then removed, and the cells were incubated in fresh DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS overnight for preparation of reconstituted smooth muscle fibers (see below). For the rescue experiments, AxCA–MLCK/sense or AxCA-stuffer was transduced at a titer of 160 moi into the cells that had been transduced by AxCA–MLCK/antisense.

Preparation of Cell-Populated Collagen Fibers.

String-shaped, reconstituted tissue fibers were prepared as described (16). Briefly, dispersed cells were suspended in an ice-cold collagen solution containing 3 × 106 cells/ml cultured cells, 2.2 mg/ml collagen type I-A, and 0.24 mg/ml collagen type IV in DMEM as described (16). Two milliliters of the suspension was poured into a trough and placed in a CO2 incubator (humidified 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere) at 37°C for 2 h, then 15 ml of fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to each Petri dish containing the trough. After 7 days of incubation, a string-shaped fiber was formed and used for the tension measurement.

Western Blot Analysis.

SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting with a poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane (Immobilion PVDF Transfer Membrane; Millipore) were performed as described (15, 16). The membranes were treated with antibodies as follows. A monoclonal antibody against chicken gizzard MLCK (Sigma, clone K36) was used to detect both 130- and 210-kDa MLCKs. Rho-kinase was detected with a polyclonal antibody (K-18, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Telokin was detected with the polyclonal anti-telokin antibody (15, 19). The immunoreactive proteins were visualized by using enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection system (Amersham Pharmacia) and/or 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma).

Measurement of Isometric Tension.

Smooth muscle cell fiber of 20 mm in length was mounted vertically in a 10-ml organ bath containing Leibovitz's L-15 medium at 37°C and equilibrated for at least 1 h at a resting tension of 2 mN. The tension development was recorded isometrically with a force displacement transducer (TB-612T, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo). These procedures are essentially the same as those reported (16).

MLC20 Phosphorylation Assay.

The MLC20 phosphorylation assay using glycerol-PAGE coupled with Western blotting was performed as described (15, 20). Briefly, smooth muscle fibers were stimulated with 10−7 M norepinephrine (NE) or 5 × 10−6 M A23187 for a specified time, then flash-frozen. The phosphorylated MLC20 was detected by Western blotting (see above) after glycerol-PAGE with the antibodies as follows. The monoclonal MY-21 antibody to MLC20 (Sigma) was used to recognize both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated MLC20s. The phosphorylated MLC20s were confirmed with antibodies donated by Y. Sasaki (20), which recognize the MLC20 monophosphorylated at Ser-19 and the MLC20 diphosphorylated at Thr-18 and Ser-19 (15, 20). Western blots were quantified by densitometry using the nih image program (Version 1.62).

Data Analysis.

All data are presented as means ± SE. ANOVA and Student's t test were used to assess differences. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Down-Regulated Expression of Short MLCK in Cells Harboring Antisense MLCK.

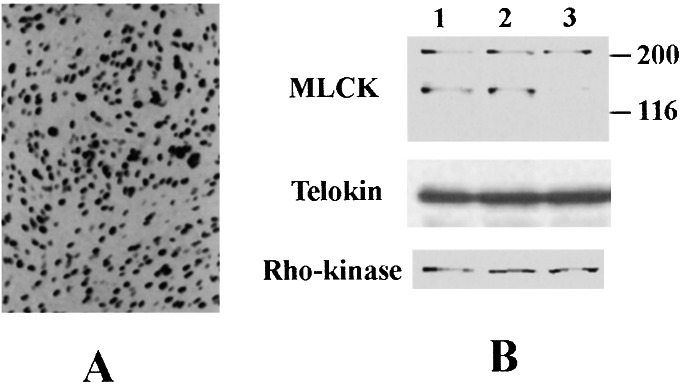

To examine to what extent the adenoviral vector was introduced into GbaSM-4 cells, we allowed the β-galactosidase vector of AxCA–NLacZ to infect the cells. The staining of the infected cells by X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside) showed a ≥90% efficiency of transduction (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Infection of GbaSM-4 with the adenovirus vectors. GbaSM-4 cells cultured in monolayers were infected with AxCA–NLacZ and incubated for 72 h. The transduction was verified by β-galactosidase staining. Original magnification, ×100. (B) Comparison of MLCK, telokin, and Rho-kinase expression in fibers reconstituted from GbaSM-4 cells by Western blot analyses. Each lane was loaded with 5 μg of protein and subjected to immunoblotting with monoclonal antibody against MLCK and polyclonal antibodies to Rho-kinase and telokin. Lane 1, Untreated GbaSM-4 cells; lane 2, GbaSM-4 cells infected with the control vector of AxCA-stuffer; lane 3, GbaSM-4 cells infected with the antisense vector of AxCA–MLCK/antisense; MLCK, MLCK expression; telokin, telokin expression; Rho-kinase, Rho-kinase expression.

Cell-populated collagen fibers were formed from the GbaSM-4 cells, those infected with AxCA-stuffer, and those infected with AxCA–MLCK/antisense. Equal quantities of total protein extracts from these fibers were subjected to Western blotting (Fig. 2B), which showed that the long MLCK isoform of ≈210 kDa and the short MLCK isoform of 130 kDa were expressed to a similar extent in untreated fibers and fibers infected with AxCA-stuffer. However, the expression of short MLCK was markedly decreased in AxCA–MLCK/antisense-transduced fibers; the signals from the short MLCK of AxCA-stuffer-transduced fibers and AxCA–MLCK/antisense-transduced fibers were 94.2% ± 6.2% (n = 4) and 7.6% ± 2.3% (n = 4), respectively, of the signals from untreated fibers. In contrast, the signals of the long MLCK from the AxCA-stuffer-transduced fibers and the AxCA–MLCK/antisense-transduced fibers were 96.1% ± 5.5% (n = 4) and 80.3% ± 3.7% (n = 4), respectively, of the signals from untreated fibers. These results indicate that transduction of AxCA–MLCK/antisense produced the short MLCK-deficient fibers. On the other hand, the expression of telokin and Rho-kinase remained unaffected as shown in Fig. 2B.

Inhibition of Isometric Contraction by the Down-Regulation of Short MLCK.

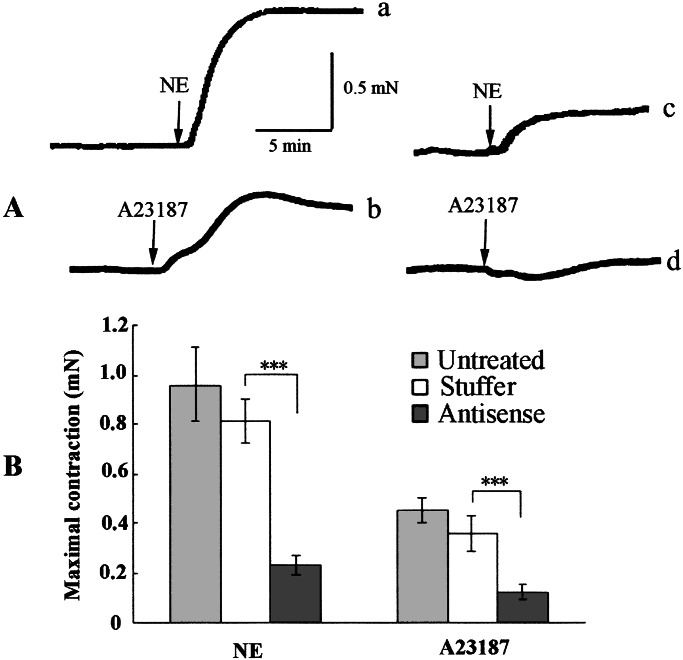

The contraction of the fibers reconstituted from GbaSM-4 cells was monitored isometrically. As shown in Fig. 3, fibers of the untreated cells and the cells infected with AxCA-stuffer developed maximum tensions of 0.96 ± 0.15 mN (n = 4) and 0.81 ± 0.09 mN (n = 4), respectively, on NE (10−7 M) stimulation. However, the maximum tension induced by NE of the fibers infected with AxCA–MLCK/antisense was depressed to 0.23 ± 0.04 mN (n = 4). These contractile responses could be repeatedly evoked by NE stimulation (data not shown).

Figure 3.

(A) Typical record of contraction of cell-populated fibers. Fibers infected with AxCA-stuffer (traces a and c) or AxCA–MLCK/antisense (traces b and d) were contracted isometrically by stimulation with 10−7 M NE (traces a and b), or 5 × 10−6 M A23187 (traces c and d). (B) Means ± SE (n = 4) in mN of maximum tension are expressed by bars and error bars. ***, Significant at P < 0.001 level compared with AxCA-stuffer-transduced fibers.

When the fibers were stimulated with A23187 (5 × 10−6 M), the maximum tensions of fibers of the untreated cells and AxCA-stuffer-treated cells were 0.45 ± 0.05 mN (n = 4) and 0.36 ± 0.07 (n = 4), respectively. However, fibers of AxCA/antisense-treated cells contracted with maximum tensions of 0.12 ± 0.03 mN (n = 4) on A23187 stimulation. We used A23187 as a calcium ionophor that allows Ca2+ to enter into cells. Unlike the stimulation by NE, contraction evoked by A23187 smaller (Fig. 3B) was not reversible (data not shown); the reason for this remains to be determined.

Rescue Experiments.

To see whether the depressed contractile activities of the cells infected with antisense MLCK vector of AxCA–MLCK/antisense is attributable to the targeting of the endogenous mRNA of short MLCK, GbaSM-4 cells harboring AxCA–MLCK/antisense were further infected with the sense MLCK vector AxCA–MLCK/sense. We then reconstituted fibers from these cells to see whether the down-regulation of short MLCK was rescued. As a control, AxCA-stuffer was introduced into the AxCA–MLCK/antisense-treated cells. When the cells harboring AxCA–MLCK/antisense were further infected with AxCA–MLCK/sense, the short MLCK expression increased to 94.1% ± 5.3% (n = 3). However, no such increase was observed when AxCA–MLCK/antisense-transduced cells were further treated with AxCA-stuffer; the short MLCK isoform expression remained at 11.2% ± 3.8% (n = 3). These data indicate that the down-regulation of short MLCK expression was rescued by the additional transduction of AxCA–MLCK/sense. No obvious difference in the long MLCK expression was observed when the fibers with AxCA–MLCK/antisense were further treated with AxCA–MLCK/sense, because the signals of ≈210 kDa were 87.6% ± 8.3% (n = 3) for the AxCA–MLCK/sense-treated cells, and 79.1% ± 7.8% (n = 3) for the AxCA-stuffer-treated cells.

Concerning the rescue of tension development, the maximum tension on NE stimulation of the AxCA–MLCK/antisense-treated fiber was increased from 0.23 ± 0.04 mN (n = 4) (Fig. 3) to 0.57 ± 0.07 mN (n = 4) by the additional transduction of AxCA–MLCK/sense. Similar recovery was detected on the stimulation with A23187, from 0.12 ± 0.03 mN (n = 4) (Fig. 3) to 0.28 ± 0.04 mN (n = 3), after the additional transduction. However, no recovery was observed after the additional transduction of AxCA-stuffer (data not shown).

It is notable that the rescue of contraction by the transduction of AxCA–MLCK/sense was incomplete, although the expression of short MLCK was rescued almost completely. We speculate that the incomplete rescue in tension development is attributable to the nonspecific effect of the repeated infection with the adenoviral vectors.

Effects of the Treatment with Antisense MLCK on MLC20 Phosphorylation.

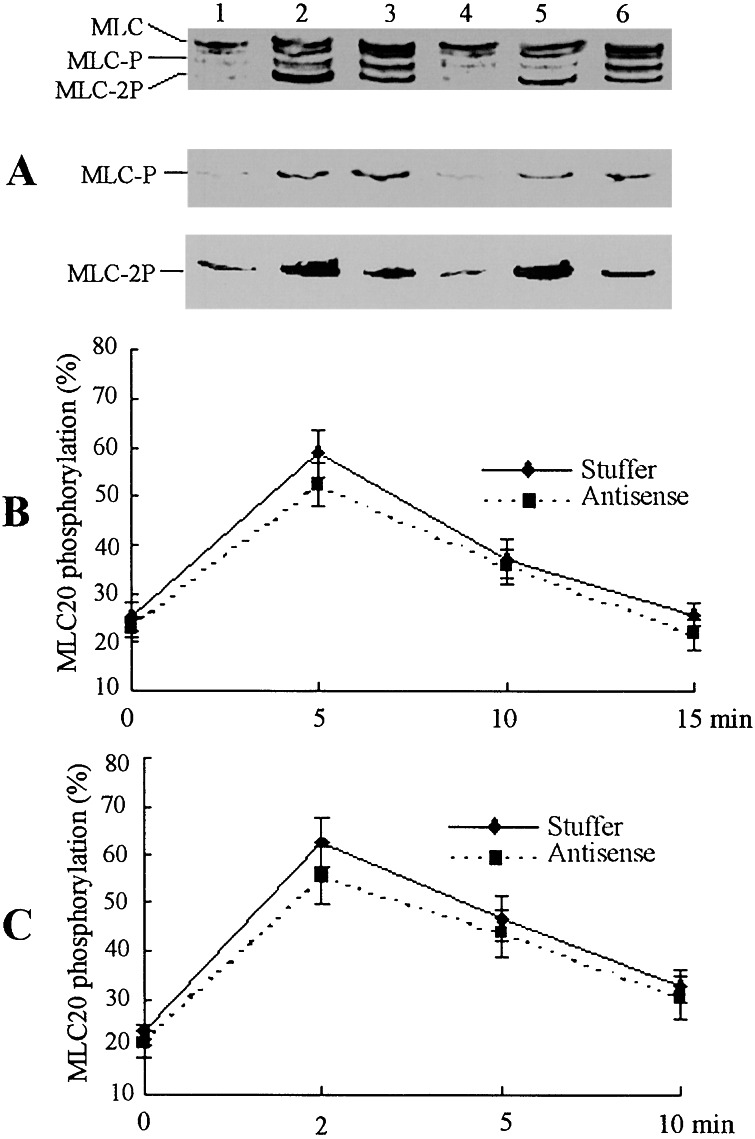

To examine whether phosphorylation of MLC20 is affected by down-regulation of the short MLCK isoform, the fibers reconstituted from the GbaSM-4 cells treated with AxCA–MLCK/antisense or AxCA-stuffer were stimulated with 10−7 M NE or 5 × 10−6 M A23187, and then subjected to Western blot analysis with a monoclonal antibody against MLC20. In AxCA-stuffer-transduced fibers, NE stimulation for 5 min caused a significant increase in MLC20 phosphorylation as expressed by (monophosphorylated MLC20 + diphosphorylated MLC20) per total MLC20 from the basal level of 25.2% ± 2.7% (n = 4) to 58.9% ± 5.0% (n = 4). The phosphorylation was 37.3% ± 2.3% (n = 4) after 10 min of stimulation, and 25.7% ± 2.3% (n = 4) after 15 min of stimulation. The phosphorylation of the AxCA/antisense-treated fibers was 22.7% ± 1.9% (n = 4) before stimulation, 52.3% ± 4.2% (n = 4) 5 min after NE stimulation, and 35.6% ± 3.6% (n = 4) 10 min after NE stimulation (Fig. 4B). These results were unexpected, because the contraction of the fibers in which short MLCK was down-regulated was markedly affected (Fig. 3B).

Figure 4.

Myosin light chain (MLC20) phosphorylation in reconstituted fibers. (A) AxCA-stuffer-transduced (lanes 1, 2, and 3) or AxCA–MLCK/antisense-transduced (lanes 4, 5, and 6) fibers were stimulated with NE 10−7 M (lanes 3 and 6) for 5 min or 5 × 10−6 M A23187 (lanes 2 and 4) for 2 min, then subjected to glycerol-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Unphosphorylated MLC20 (MLC), monophosphorylated MLC20 (MLC-P), and diphosphorylated MLC20 (MLC-2P) were simultaneously detected with monoclonal anti-MLC20 antiboby as shown in the Top. The blots were also reacted with anti-MLC-P antibody (Middle) and anti-MLC-2P antibody (Bottom) to detect Ser-19-monophosphorylated MLC20 and Thr-18/Ser-19-diphosphorylated MLC20 (15, 20). (B and C) Time course of MLC20 phosphorylation in fibers stimulated with 10−7 M NE (B) or 5 × 10−6 M A23187 (C). Values are means ± SE (n = 4).

MLC20 phosphorylation on A23187 stimulation is shown in Fig. 4C. The basal phosphorylation of the fibers with AxCA-stuffer and AxCA–MLCK/antisense was 23.1% ± 1.6% (n = 4) and 20.4% ± 2.8% (n = 4), respectively. After stimulation for 2 min, 5 min, and 10 min, the phosphorylation of the AxCA-stuffer-treated fibers was 62.7% ± 5.3% (n = 4), 46.8% ± 4.8% (n = 4), and 32.7% ± 3.6% (n = 4), respectively; and that of the AxCA–MLCK/antisense-treated fibers was 55.6% ± 6.1% (n = 4), 43.7% ± 5.1% (n = 4), and 30.2% ± 4.2% (n = 4), respectively. Again, no differences in MLC20 phosphorylation were detectable, regardless of whether or not short MLCK was down-regulated.

In Fig. 4A Top, we assigned MLC-P and MLC-2P as monophosphorylated MLC20 and diphosphorylated MLC20, respectively. The phosphorylation of MLC20 at Ser-19 or at Thr-18/Ser-19 activates myosin functions (21). However, other amino acids such as Ser-1 or Ser-2 were also phosphorylatable (22). Thus, MLC-P and MLC-2P bands might contain MLC20 that is not related to the myosin activation. To exclude such a possibility, we carried out Western blot analysis using an antibody that recognizes MLC20 monophosphorylated at Ser-19 and another that recognizes MLC20 diphosphorylated at Thr-18 and Ser-19 (15, 20). We failed to detect significant differences in the phosphorylation levels between the fibers treated with AxCA-stuffer and those treated with AxCA–MLCK/antisense (Fig. 4A Middle and Bottom). These findings are compatible with the above conclusion that MLC20 phosphorylation was not affected, even though short MLCK was down-regulated.

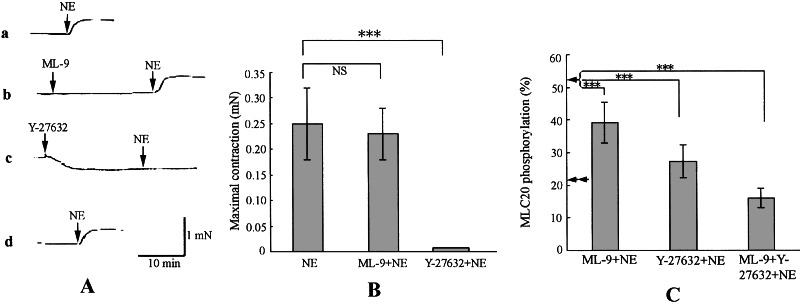

Effect of ML-9 and Y-27632 on the Tension Development of the Fiber Deficient in the Short MLCK Expression.

Treatment of GbaSM-4 cells with the antisense vector of AxCA–MLCK/antisense hardly down-regulated the expression of long MLCK and telokin (Fig. 2B), though they are the products of the same gene (23). Telokin assembles myosin into thick filaments (6), but to our knowledge, a regulatory role of telokin in smooth muscle contraction has not been reported. On the other hand, Rho-kinase, though not a product of the MLCK gene, regulates smooth muscle contraction (reviewed in ref. 25). Therefore, we investigated whether long MLCK and Rho-kinase exert regulatory roles in the contraction of the fibers reconstituted from Gba-SM4 cells, using ML-9 as an inhibitor for the former (26) and Y-27632 as an inhibitor for the latter (27).

As shown in Fig. 5A, trace a, and Fig. 5B, the fibers developed a small tension of 0.25 ± 0.07 mN (n = 4) on 10−7 M NE stimulation. After pretreatment of the fibers with 3 × 10−5 M ML-9 for 20 min, the same stimulation developed a tension of 0.23 ± 0.05 mN (n = 4) (Fig. 5B), indicating that the contraction was not affected (compare trace a with trace b in Fig. 5A). However, the level of MLC20 phosphorylation 5 min after NE stimulation was reduced by pretreatment with ML-9 from 52.3% ± 2.4% (n = 4) to 39.3% ± 6.2% (n = 4) (Fig. 5C). This reduction is attributable to the inhibition of kinase activity of long MLCK, which was not associated with any changes in the contractile activity.

Figure 5.

Effects of ML-9 and Y-27632 on the contraction and on the MLC20 phosphorylation of smooth muscle fibers in which short MLCK was down-regulated. (A) AxCA–MLCK/antisense-transduced fibers were first contracted with 10−7 M NE (trace a). The fibers were washed for 60 min and incubated with 3 × 10−5 M ML-9 (trace b) or 1 × 10−6 M Y-27632 (trace c) for 20 min, then a second contraction was induced by the addition of 10−7 M NE. After another washing for 60 min, the third contraction was induced (trace d). (B) Means of the maximal contraction induced by 10−7 M NE (n = 4) was expressed by bars and error bars as means ± SE. ***, Significant at P < 0.01 level. (C) The extent of the MLC20 phosphorylation (%) was determined 5 min after the 10−7 M NE stimulation as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The bars and error bars express mean ± SE (n = 4). The double arrowheads and the arrowhead are the MLC20 phosphorylation before stimulation (see Fig. 4B) and after 10−7 M NE stimulation (see Fig. 4B), respectively. **, Significant at P < 0.01; ***, significant at P < 0.001.

Y-27632 greatly decreased the unstimulated, resting levels of tension of the fibers, as shown in Fig. 5A, trace c. Unlike the pretreatment with ML-9, however, NE stimulation 20 min after pretreatment with Y-27632 failed to develop tension of the fiber (Fig. 5A, trace c). This failure is associated with the reduction in MLC20 phosphorylation to 27.4% ± 5.1% (n = 4) (Fig. 5C). Unlike the inhibitory effect of ML-9 on MLC20 phosphorylation, the inhibition of MLC20 phosphorylation by Y-27632 was associated with that of tension development.

The total abolition of contraction induced by NE stimulation in the presence of Y-27632 is crucially important in precluding the role of short MLCK remaining after AxCA–MLCK/antisense treatment. As shown in Fig. 2B, about 7% of short MLCK remained in the fiber, and this may be the cause of the residual contraction of trace a in Fig. 5A. However, this is not the case, because the effect of Y-27632 could not be related to the conventional, short MLCK (see Discussion).

The other finding with Y-27632 is that it caused relaxation without any relaxants, indicating that the fibers are furnished with an intrinsic tension exerts an active role.

Contractile Activities of Fibers in Which both the Short and Long MLCK Isoforms Were Down-Regulated to Various Extents.

The ratio of virus vector titer to cell number—i.e., moi—was fixed at 100 moi, because this moi allows down-regulation of short MLCK with little effect on the long MLCK expression (Fig. 2B). In this section, we altered the expression of the short and long MLCK isoforms to various extents by changing the moi of the AxCA–MLCK/antisense vector to examine how the alteration modified the tension development (Table 1). The transduction of AxCA–MLCK/antisense at 50 moi reduced the expression of short MLCK to 50.5% ± 6.2% (n = 4). The tension developed by NE (10−7 M) and A23187 (5 × 10−6 M) was also reduced by about half—i.e., to 65.5% ± 11.1% (n = 4) and 51.1% ± 4.8 (n = 4), respectively. At 100 moi, the expression of short MLCK was reduced to 8.1% ± 2.4% (n = 4), and the tension development to 28.4% ± 4.9% (n = 4) on NE stimulation and to 33.3% ± 8.3% (n = 4) on A23187 stimulation. The increase of moi to 200 failed to further down-regulate short MLCK; short MLCK expression remained at 7.0% ± 2.1% (n = 6). Further depression of tension development was also not observed; the fibers at 200 moi developed tension of 25.2% ± 7.5% (n = 6) on NE stimulation and 31.1% ± 6.3% (n = 6) on A23187 stimulation. Thus, the down-regulation of the expression of short MLCK closely paralleled the reduction of the tension development.

Table 1.

MLCK isoform expression and contractility

| moi | Short MLCK, % | Long MLCK, % | Maximal

contraction, %

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE | A23187 | |||

| 50 | 50.5 ± 6.2 | 95.3 ± 9.7 | 65.5 ± 11.1 | 51.1 ± 4.8 |

| 100 | 8.1 ± 2.4 | 83.6 ± 3.9 | 28.4 ± 4.9 | 33.3 ± 8.3 |

| 200 | 7.0 ± 2.1 | 56.1 ± 4.9 | 25.2 ± 7.5 | 31.1 ± 6.3 |

The maximum tension of the AxCA–MLCK/antisense-transduced fibers was expressed relative (%) to that of the AxCA-stuffer-transduced fibers. Means ± SE (n = 6).

The expression of long MLCK in the fibers infected at 50, 100, and 200 moi was 95.3% ± 9.7% (n = 4), 83.6% ± 3.9% (n = 4), and 56.1% ± 4.9% (n = 6), respectively. As described above, tension development in response to both NE and A23187 stimulations was depressed when moi was raised from 50 to 100. However, the down-regulation of long MLCK was slight. On the other hand, the increase in moi from 100 to 200 did not cause further decrease in tension development, but the increase in moi effectively down-regulated long MLCK. Thus, the expression of long MLCK does not parallel the tension development. These data are in conformity with those obtained with ML-9 in the previous section, precluding the involvement of long MLCK in tension development.

Discussion

GbaSM-4, a cell line derived from vascular smooth muscle cells, expresses both the short and long isoforms of MLCK. In the present study, we down-regulated almost specifically the expression of the short MLCK isoform in the vascular smooth muscle cells, resulting in the depressed contraction. The decrease in the contraction caused by the down-regulation of short MLCK was not associated with a decrease in the MLC20 phosphorylation. The time course of the phosphorylation on stimulation by agonists was hardly altered by whether or not MLCK was down-regulated (Fig. 4), indicating that tension generation can be inhibited without reducing MLC20 phosphorylation. However, this issue is not sufficient to exclude the likelihood that the MLC20 phosphorylation is necessary for this contraction.

Does the residual kinase activity to phosphorylate MLC20 in the cells in which short MLCK was down-regulated explain the residual contraction of the fiber reconstituted from them? Western blots (Fig. 2B) showed that the long MLCK was hardly down-regulated and can thus be expected to take part in the activity. The other candidate for the activity is Rho-kinase (Fig. 2B), which might phosphorylate MLC20 directly and/or by phosphorylating myosin phosphatase to reduce its activity (28). We examined this question by the use of kinase inhibitors (Fig. 5A) as follows. After 5 min of stimulation by NE, MLC20 of the down-regulated cells was phosphorylated to 52.3% ± 4.2% (n = 4) as shown in Fig. 5C. When the Rho-kinase activity was inhibited by Y-27632, MLC20 phosphorylation was reduced to 27.4% ± 5.1% (n = 4). In this fiber, contraction by the same stimulation was totally abolished (trace c in Fig. 5A). Therefore, the abolition was associated with the reduction of MLC20 phosphorylation by 24.9% (Fig. 5C), a figure that explains the abolition in terms of MLC20 phosphorylation. ML-9 also reduced MLC20 phosphorylation to 39.3% ± 6.2% (n = 4) (Fig. 5C). According to Birukov et al. (26), the reduction by 13.0% is attributable to the inhibition of the activity of the long MLCK. However, this reduction was not associated with any changes in contractile activity (traces a and b in Fig. 5A). ML-9 plus Y-27632 inhibited MLC20 phosphorylation to the resting, unstimulated level of MLC20 phosphorylation—i.e., 16.1% ± 2.9% (n = 4) (Fig. 5C)—indicating the involvement of additional kinase(s) in MLC20 phosphorylation. Thus, the kinase activity to phosphorylate MLC20 in the short MLCK-deficient cells is composed of the long MLCK, Rho-kinase and unidentified kinase(s). One of those exerting a regulatory role through MLC20 phosphorylation is Rho-kinase. Long MLCK appears not to be involved in the regulation of contraction.

What mechanism(s) is involved in the contraction unassociated with MLC20 phosphorylation? We have reported that caldesmon (29) and calponin (30) exert a stimulatory effect on the myosin ATPase activity of smooth muscle through myosin-binding activity. Similarly, we recently observed that the myosin-binding fragment of MLCK, which is devoid of kinase activity, stimulated the myosin ATPase activity (13). These observations were made only in vitro. Therefore, these proteins are candidates for the regulatory proteins that activate smooth muscle contraction independently of MLC20 phosphorylation through the myosin-binding activity (reviewed in ref. 14).

The remaining concern is whether or not GbaSM-4 cells are smooth muscle cells. GbaSM-4 cells were stained with antibodies against differentiated smooth muscle marker proteins—i.e., SM-2 myosin heavy chain (31) and smooth muscle α-actin (24) (data not shown). The presence of long MLCK indicated that they were furnished with embryonic properties (9).

In the previous study (15), the down-regulation of MLCK was performed with a plasmid vector carrying the same antisense cDNA, a method that requires screening of mutants with antisense MLCK. Therefore, these mutants might acquire a salvage pathway during the repeated subculture. However, subculture was not required in the present method using the adenovirus vector, ruling out such a possibility. Together with the rescue experiments, this finding demonstrates that the depression in contraction of the present study is solely attributable to the down-regulation of the short MLCK isoform.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Naito Foundation, the Smoking Research Foundation, and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research and the Special Coordination Funds of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Abbreviations

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

- AxCA–MLCK/antisense

adenovirus bearing MLCK-cDNA in the antisense orientation

- AxCA–MLCK/sense

adenovirus bearing MLCK-cDNA in the sense orientation

- AxCA–NLacZ

adenovirus recombinant containing bacterial β-galactosidase

- AxCA-stuffer

adenovirus recombinant containing nonsense cDNA

- MLC20

the 20-kDa light chain of smooth muscle myosin

- moi

multiplicity of infection

- NE

norepinephrine

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AB070227).

References

- 1.Kamm K E, Stull J T. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1985;25:593–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.25.040185.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye L-H, Hayakawa K, Kishi H, Imamura M, Nakamura A, Okagaki T, Takagi T, Iwata A, Tanaka T, Kohama K. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32182–32189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith L, Su X, Lin P-J, Zhi G, Stull J T. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29433–29438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito M, Dabrowska R, Guerriero V, Jr, Hartshorne D J. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13971–13974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher P J, Herring B P. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23945–23952. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirinsky V P, Vorotnikov A V, Birukov K G, Nanaev A K, Collinge M, Lukas T J, Sellers J R, Watterson D M. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16578–16583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson N J, Pearson R B, Needleman D S, Hurwitz M Y, Kemp B E, Means A R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2284–2288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia J G, Lazar V, Gilbert-McClian L I, Gallagher P J, Verin A D. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:489–494. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.5.9160829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamm K E, Stull J T. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4527–4530. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somlyo A P, Somlyo A V. Nature (London) 1994;372:231–236. doi: 10.1038/372231a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohama K, Saida K. Smooth Muscle Contraction: New Regulatory Modes. Basel: S. Karger AG; 1995. pp. 1–159. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oishi K, Takano-Ohmuro H, Minakawa-Matsuo N, Suga O, Karibe H, Kohama K, Uchida M K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;176:122–128. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90898-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye L-H, Kishi H, Nakamura A, Okagaki T, Tanaka T, Oiwa K, Kohama K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6666–6671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao Y, Ye L-H, Kishi H, Okagaki T, Samizo K, Nakamura A, Kohama K. IUBMB Life. 2001;51:337–344. doi: 10.1080/152165401753366087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishi H, Mikawa T, Seto M, Sasaki Y, Kanayasu-Toyoda T, Yamaguchi T, Imamura M, Ito M, Karaki H, Bao J, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1414–1420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oishi K, Itoh Y, Isshiki Y, Kai C, Takeda Y, Yamaura K, Takano-Ohmuro H, Uchida M K. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1432–C1442. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.5.C1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher P J, Herring B P, Griffin S A, Stull J T. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23936–23944. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyake S, Makimura M, Kanegae Y, Harada S, Sato Y, Takamori K, Tokuda C, Saito I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1320–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito M, Guerriero V, Jr, Chen X M, Hartshorne D J. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3498–3503. doi: 10.1021/bi00228a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakurada K, Seto M, Sasaki Y. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;274:C1563–C1572. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikebe M, Hartshorne D J. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:10027–10031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bengur A R, Robinson E A, Appella E, Sellers J R. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7613–7617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birukov K G, Schavocky J P, Shirinsky V P, Chibalina M V, Van Eldik L J, Watterson D M. J Cell Biochem. 1998;70:402–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owens G K, Loeb A, Gordon D, Thompson M M. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:343–352. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.2.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Somlyo A P, Somlyo A V. J Physiol. 2000;522:177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birukov K G, Csortos C, Marzilli L, Dudek S, Ma S-F, Bresnick A R, Verin A D, Cotter R J, Garcia J G. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8567–8573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uehata M, Ishizaki T, Satoh H, Ono T, Kawahara T, Morishita T, Tamakawa H, Yamagami K, Inui J, Maekawa M, Narumiya S. Nature (London) 1997;389:990–994. doi: 10.1038/40187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kureishi Y, Kobayashi S, Amano M, Kimura K, Kanaide H, Nakano T, Kaibuchi K, Ito M. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12257–12260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin Y, Ishikawa R, Okagaki T, Ye L-H, Kohama K. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1994;29:250–258. doi: 10.1002/cm.970290308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin Y, Ye L-H, Ishikawa R, Fujita K, Kohama K. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1993;113:643–645. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rovner A S, Murphy R A, Owens G K. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:14740–14745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]