Abstract

Background

In many countries, persons seeking medical abortion with mifepristone followed by misoprostol can self-administer the second drug, misoprostol, at home, but self-administration of the first drug, mifepristone, is not allowed to the same extent.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to evaluate whether the efficacy, safety and women’s satisfaction with abortion treatment are affected when mifepristone is self-administered at home instead of in a clinic.

Search strategy

A literature search covered CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, Ovid MEDLINE and APA PsycInfo in October 2022.

Selection criteria

Eligible studies focused on persons undergoing medical abortion comparing home and in-clinic mifepristone intake. Outcomes included abortion effectiveness, compliance, acceptability, and practical consequences for women.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently assessed eligibility and risk of bias. Meta-analysis included similar studies while those differing in design were synthesised without meta-analysis.

Results

Six studies (54 233 women) of medical abortions up to 10 weeks were included. One randomised controlled trial and one retrospective register study had moderate risk of bias, and four non-randomised clinical trials where women could choose the place for intake of mifepristone had serious risk of bias. There was no difference in abortion effectiveness (high confidence) or compliance (moderate confidence) between mifepristone administered at home or in-clinic. No differences in complications were detected between groups and most women who chose home administration of mifepristone expressed a preference for this approach.

Conclusions

Our systematic review demonstrates that the effectiveness of medical abortion is comparable regardless of mifepristone administration and intake, at home or in the clinic.

Keywords: Abortifacient Agents, abortion, Mifepristone

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Previous systematic reviews have not focused on home use of mifepristone. Summarising existing evidence will be important for clinical guidelines and increased access.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This systematic review adds valuable insight by demonstrating that the effectiveness and safety of medical abortion is comparable regardless of where mifepristone is administered, whether at home or in the clinic.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE, OR POLICY

The implications of this study suggest that allowing women to self-administer mifepristone at home could lead to increased access to medical abortion while maintaining effectiveness and safety. Policymakers may consider revising regulations to permit home administration of mifepristone, thereby aligning regulations with evidence-based practices and potentially improving women’s satisfaction with abortion treatment.

Introduction

Safe and effective abortion methods are a prerequisite for sexual and reproductive health.

Mifepristone followed by misoprostol is widely acknowledged as a safe and effective method to induce medical abortion and can be used without clinical follow-up.1 2 Studies have already shown for many years that self-administration of misoprostol at home is as effective as in-clinic provider-administration (ie, outside the clinic rather than in a clinic).3 4 Observational data have also indicated that self-administration of both mifepristone and misoprostol at home is safe and effective, improves acceptability and accessibility, and saves time due to less need to take time off work or school or need to arrange child care. It also allows for anonymity.5 6

Requesting patients to present at clinics for counselling, various tests and gestational age determination by ultrasound as well as abortion drug provision creates unnecessary barriers and costs to individuals and healthcare systems. Moreover, a recent systematic review concluded that medical abortion performed without prior pelvic examination or ultrasound (‘no-test medical abortion’) is a safe and effective option for pregnancy termination.7

The WHO Abortion Care Guideline emphasises that women should be given the opportunity of self-administration of mifepristone as well as misoprostol at home until 12 weeks’ gestation.1 Women are allowed to self-administer misoprostol in many countries, but self-administration of mifepristone is not allowed to the same extent.

The Swedish law as currently practised allows for home-use of misoprostol but requires providers to administer mifepristone. However, recently some countries now allow self-managed medical abortion without in-clinic visits (www.abortreport.eu.) in health clinics.8 9 The Swedish government is currently set to review the abortion law regarding medical abortion at home. Our systematic review will provide evidence to inform these decisions. Similarly, self-administration of both mifepristone and misoprostol was recently allowed in the UK.10 11

To date, no systematic review comparing the effectiveness and safety of self-administration of mifepristone at home with administration in the clinic has been published. This systematic review aims to evaluate effectiveness, safety, contacts with healthcare services, compliance and patient experience of the abortion and practical consequences of medical abortion with intake of mifepristone at home compared with in a clinic.

Material and methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered in advance in PROSPERO12 (CRD 42022344250) and is presented in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

Data sources

The search strategy was constructed and performed by a research librarian using controlled vocabulary and text word terms for the following three concepts: abortion, location other than a clinic, and abortifacient agents. The search was performed from database inception up until 26 October 2022. The systematic literature search included the databases CINAHL with Full Text (EBSCO), Cochrane Library (Wiley), Embase (Elsevier), Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL and APA PsycInfo (EBSCO). Articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were used in a forward citation search in Scopus. A complementary search for published and ongoing systematic reviews and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) reports was performed in Epistemonikos, International HTA Database and KSR (Kleijnen Systematic Reviews) Evidence. The following clinical trial registries were searched on 9 September 2022: ClinicalTrials.gov, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, European Union Clinical Trials Register, Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, and Pan-African Clinical Trials Registry. Reference lists of included articles and studies included in systematic reviews on closely related topics were manually screened to identify additional studies. No time or language limitations were made in the search, and conference abstracts were excluded in Embase. The search strategy was assessed by another information specialist before execution of the search. Most duplicate records were removed in EndNote (EndNote 20; 2013. Philadelphia PA Clarivate)13 and any remaining duplicates were removed in Covidence (Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation Melbourne, Australia. www.covidence.org.) The full search strategy for each database is provided in online supplemental appendix S1.

Main outcomes measures

Outcomes included were effectiveness of the abortion (proportion of patients with complete abortion, incomplete abortion and ongoing pregnancy), patient safety (complications and hospital care), contacts with healthcare after treatment (unplanned and planned telephone contacts with clinic and unplanned clinical visits), compliance with treatment (treatment initiated within recommended gestational age according to the study protocol), time between treatment with mifepristone and misoprostol, and the overall compliance (intake of the prescribed dose, recommended interval between the medications, administration route and initiation of treatment within the recommended time limits combined, and patient’s experience of the abortion). The proportion of women who were satisfied with the procedure and/or the proportion of women who would choose to take mifepristone at the same place in case of a new abortion and practical consequences (absence from work or school due to the abortion) were also measured.

Eligibility criteria

Studies had to investigate medical abortion in abortion-seeking pregnant women, regardless of gestational age. Studies (with or without random allocation) comparing self-administration and intake of mifepristone at home (without being monitored) with administration in a clinical setting were included. Mifepristone was to be followed by misoprostol or gemeprost and these drugs could be administered anywhere. Only studies in English, Swedish, Norwegian or Danish were included.

Studies were reviewed for eligibility and risk of bias in Covidence. All abstracts were assessed by two reviewers, and abstracts deemed relevant by one or both were assessed in full text. Similarly, full texts were assessed by two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between reviewers or in the project group. Studies included after full text review were assessed for risk of bias, using for the project customised versions of ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies - of Interventions)14 or RoB 2 (Risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials version 2)15 depending on study design (online supplemental appendix S2). Assessments were performed by two reviewers and disagreements discussed in the project group. Studies where the risk of bias of results were deemed as low, moderate or serious were included in the review. Studies where the risk was deemed as critical were excluded as they did not provide useful evidence. This was decided on after the publication of the protocol.

Data collection and analysis

One reviewer extracted data from the included studies while a second reviewer checked the data. Information on the proportion of women experiencing each of the included outcomes as well as median time interval between the drugs were extracted for both intervention and control groups. We extracted data on study design, group allocation, country, setting, location of administration of drugs, accepted interval between drugs, dose and route of drugs, time until follow-up, method to determine if the abortion was successful, additional differences in treatment between intervention and control groups, age of participants, gestational age and how it was determined, and the proportion of participants that had a previous abortion, that worked or that studied.

Results from studies of similar design and comparisons were synthesised using meta-analysis. Otherwise, a synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) was performed. Meta-analysis were performed in Review Manager (RevMan Version 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) using a random effects model and the Mantel-Haenszel method for weighting of studies.16 Results reported were risk differences and relative risks with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Risk differences were considered the main result as absolute measures are preferred according to GRADE.17 However, relative risks are also reported in table 1

Table 1. Summary of findings and certainty of evidence for the different outcome measures.

| Outcome | Participants (n) (number of studies, design) references |

Results RD and RR (95% CI) |

Difference between groups | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) deduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness of the abortion procedure (complete/incomplete abortion, and ongoing pregnancies together) |

53 790 (3 NRCT, 1 RCT, 1 retrospective register study) 19,24 |

See proportion of complete/incomplete abortion, and ongoing pregnancies (below) | No difference between groups | High ⊕⊕⊕⊕ No deduction* |

| Proportion of complete abortion | 53 790 (3 NRCT, 1 RCT, 1 retrospective register study) 19,2224 |

NRCT: RD 0.00 (–0.06 to 0.06) RR 1.00 (0.93 to 1.08) RCT: RD 0.00 (–0.03 to 0.04) RR 1.00 (0.96 to 1.04) Retrospective register study: RD 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01) RR 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01) |

No difference between groups | High ⊕⊕⊕⊕ No deduction* |

| Proportion of incomplete abortion |

52 742 (2 NRCT, 1 retrospective register study)19 21 22 |

NRCT RD 0.00 (–0.02 to 0.02) RR 0.78 (0.25 to 2.41) Retrospective register study: RD –0.00 (–0.00 to –0.00) RR 0.68 (0.57 to 0.82) |

No difference between groups |

Low ⊕⊕ΟΟ Risk of bias† Imprecision‡ |

| Proportion of ongoing pregnancy | 53 489 (2 NRCT, 1 RCT, 1 retrospective register study) 19,22 |

NRCT: RD 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.02) RR 1.36 (0.29 to 6.40) RCT: RD 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.02) RR 1.91 (0.48 to 7.58) Retrospective register study: RD –0.00 (–0.00 to –0.00) RR 1.91 (0.48 to 7.58) |

No difference between groups | Low ⊕⊕ΟΟ Risk of bias§ Imprecision‡ |

| Proportion of women with unplanned telephone contacts | 1191 (4 NRCT) 21,24 |

NRCT: RD 0.04 (0.00 to 0.08) RR 1.52 (1.05 to 2.19) |

Higher proportion among those who took mifepristone at home | Low ⊕⊕ΟΟ Risk of bias§¶ Indirectness** Imprecision†† |

| Proportion of women with unplanned healthcare visits | 1938 (4 NRCT, 1 RCT) 20,24 |

NRCT: RD 0.00 (–0.02 to 0.02) RR 1.08 (0.48 to 2.44) RCT: RD 0.02 (–0.03 to 0.06) RR 1.18 (0.77 to 1.81) |

No difference between groups | Low ⊕⊕ΟΟ Risk of bias§¶ Indirectness** Imprecision‡ |

| Compliance to treatment | 1938 (4 NRCT, 1 RCT) 20,24 |

See results in Supporting Information online supplemental table S5 | No difference between groups | Moderate ⊕⊕⊕Ο Risk of bias§ Indirectness** |

| Proportion of women who were absent from work | 651 (3 NRCT) 21 23 24 |

NRCT: RD –0.12 (–0.20 to –0.04) RR 0.55 (0.32 to 0.97) |

Lower proportion mifepristone at home | Low ⊕⊕OO Risk of bias§‡‡ Indirectness** |

| Proportion of women who were absent from school | 234 (3 NRCT) 21 23 24 |

NRCT: RD 0.01 (–0.09 to 0.11) RR 1.05 (0.61 to 1.82) |

Not possible to evaluate | Very low ⊕OOO Risk of bias§‡‡ Indirectness** Precision§§ |

The symbols (⊕) indicates certainty of evidence according to GRADE

Limitations in some of the included studies (lack of random allocation) may affect risk of bias. However, the fact that all studies show similar results, despite differences in design and context, strengthens the evidence.

Limitations in some of the included studies (lack of random allocation and too short follow-up) affect risk of bias.

A small number of events may cause imprecision.

Lack of random allocation in included studies affects risk of bias.

Lack of information on how women were instructed to make contact, and/or of how and when information on contacts were collected may affect risk of bias.

Main part of studies was performed in countries where the health system and social context may differ from Sweden which affects indirectness, as this was our population of interest.

Modest percentage difference between groups and confidence interval close to zero cause imprecision.

Lack of information about possible differences in baseline variables, as analysis is restricted to the subset of women in employment/students, which affects risk for bias.

The confidence intervals show that the analyses cannot ascertain whether home abortion affects absence from school or not and this causes imprecision.

GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; NRCT, non-randomised clinical trial, prospective clinical study where the allocation to the groups is not randomised; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RD, risk difference; RR, risk ratio.

The certainty of the evidence for each of the outcomes were graded using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).18 The GRADE domains assessed were risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias. The results were graded as having high, moderate, low or very low certainty. We have combined the results and made one GRADE assessment per outcome for all included studies despite differences in study designs. This was done as ROBINS-I, which was used for assessment of risk of bias in non-randomised studies, accounts for confounding and starts from the same level of risk of bias irrespective of study design14

There was no patient involvement in development of this review.

All of the studies included in our analysis refer to participants as ‘women’, but we recognise that not all abortion seekers do; therefore, when we refer to them as women we use ‘women’ in an inclusive way.

Results

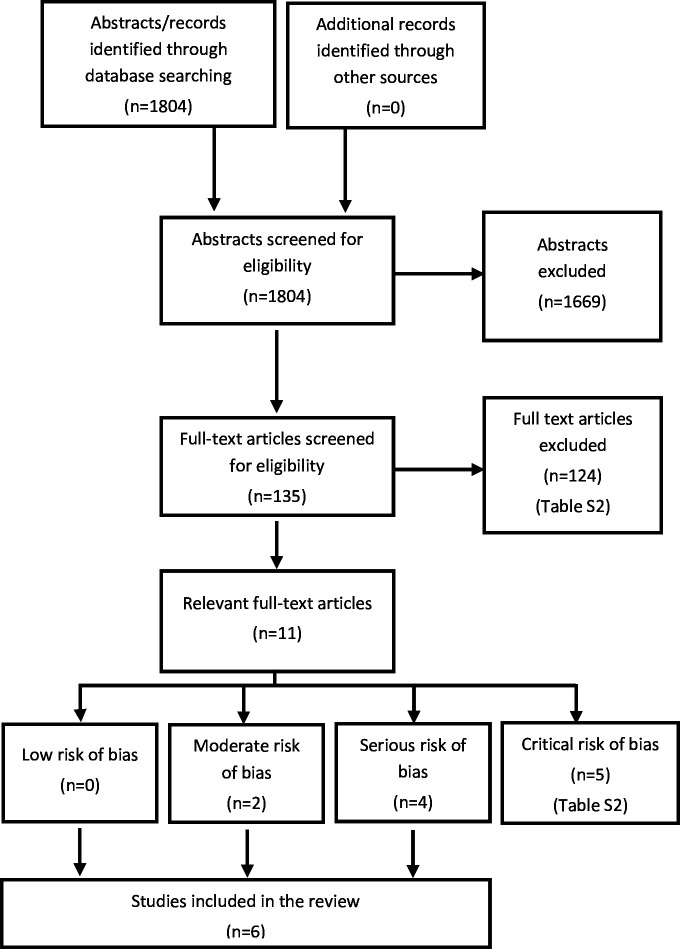

The systematic literature search identified 1804 articles after removal of duplicates (figure 1); 1669 articles were removed at the abstract level and 124 at the full text level (online supplemental table S1), leaving 11 articles for full assessment. Of these, five were excluded because of critical risk of bias (for reasons, see online supplemental table S1), leaving six studies for inclusion in the final analyses (online supplemental table S2). Two studies had moderate risk of bias19 20 and four studies had serious risk of bias21,24 (online supplemental table S3). No relevant ongoing clinical trials were found in the clinical trials registries.

Figure 1. Flowchart presenting the selection process after the literature search.

Four of the studies21,24 were non-randomised clinical trials (NRCT) where the woman herself chose the place for intake of mifepristone. One study20 was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) where women were randomised to either counselling via telemedicine and intake of mifepristone at home, or standard counselling during an appointment and intake of mifepristone in the clinic. The last study19 was a retrospective register study that compared counselling and intake of mifepristone at a clinic (before a change in routine from in-clinic provision to telemedicine provision due to the COVID pandemic) with counselling via telemedicine and intake of mifepristone at home. In total 54 233 women were included in the studies.

The included studies came from different countries with different socioeconomic contexts. One study was undertaken in Europe,19 two in the USA,21 24 one in Africa20 and two in Asia.22 23 The majority of the participants were over 18 years of age and the upper accepted limit for gestational age was 9–10 weeks. The use of ultrasound to determine gestational age varied between studies. The dosage of mifepristone was 200 mg orally. Misoprostol was administered at home but the dose and route of administration varied. For main characteristiscs of the included studies see online supplemental table S2

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of the abortion can be presented as the proportion of women with complete abortions, but also as the proportion of women without incomplete abortions or ongoing pregnancies. These results mirror each other and are presented both separately and weighed together. In table 1 the outcomes, summary of findings and certainty of the evidence are presented.

Complete abortion

Five studies comprising 53 790 participants presented results regarding complete abortion.19,2224 One study did not supply any definition,21 three studies defined a complete abortion as no need for surgical intervention,19 22 24 and one study as no need of either surgical or medical intervention.20

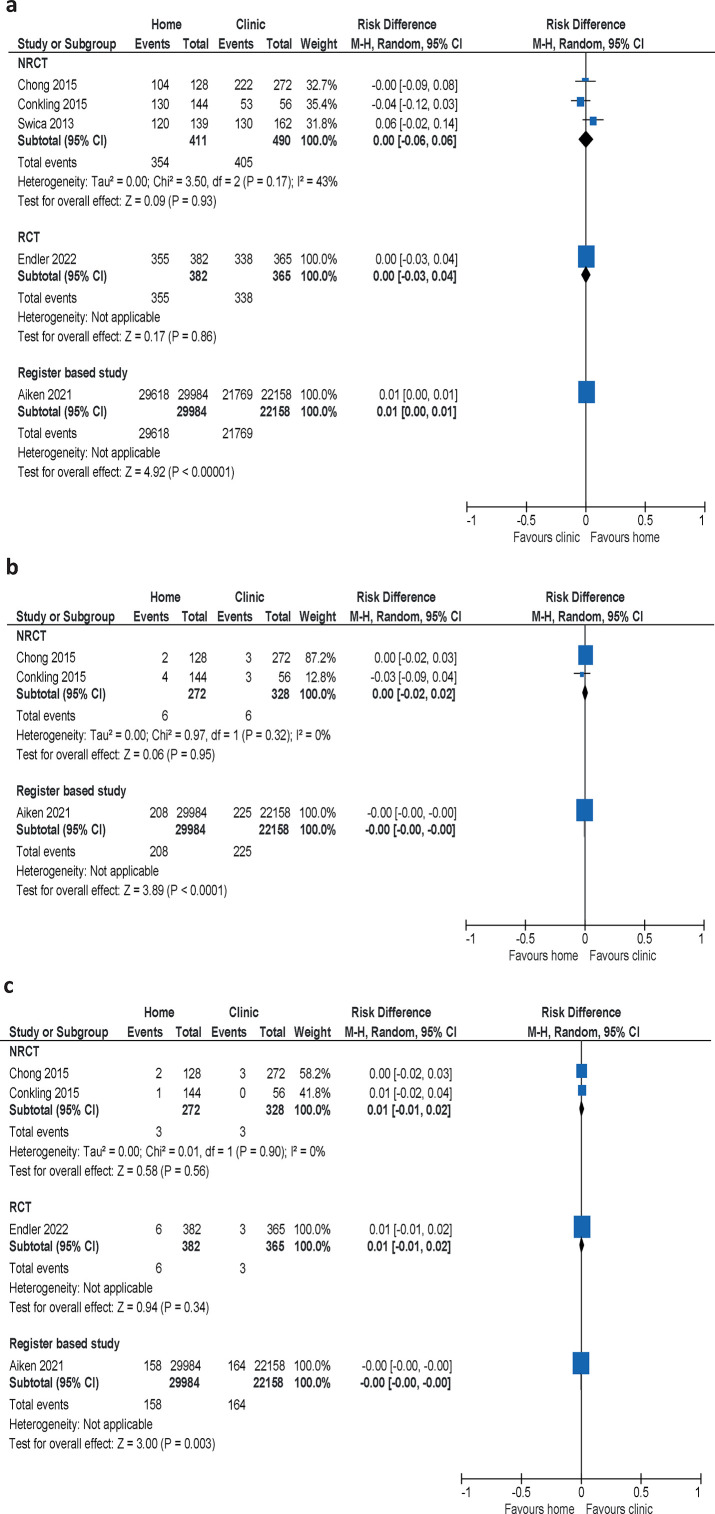

The meta-analysis of the three non-randomised clinical trials showed no difference between women who took mifepristone at home or in a clinic (risk difference (RD) 0.00, 95% CI –0.06 to 0.06). The same results were reported in the retrospective study and RCT (figure 2a, table 1).

Figure 2. Meta-analyses of studies comparing the proportion of women with (a) complete abortion, (b) incomplete abortion, and (c) ongoing pregnancy when mifepristone is administered at home or at a clinic. Differences presented as absolute risks. NRCT, non-randomised clinical trial; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Incomplete abortion

Three studies reported on incomplete abortion defined as a remaining gestational sac,21 or retained gestational products,19 or without any definition.22 In all three studies an incomplete abortion was treated with surgical intervention.

The meta-analysis of the two non-randomised clinical trials showed no difference between groups (RD 0.00, 95% CI –0.02 to 0.02). The result was confirmed by the retrospective study (figure 2b, table 1). Consequently, we found no difference in the proportion of women with incomplete abortion between intake of mifepristone at home or at a clinic.

Ongoing pregnancy

Four studies19,22 examined the proportion of ongoing pregnancies after treatment. In three of the studies19 21 22 ongoing pregnancy was treated by surgical intervention. One study did not report the method for terminating the pregnancy.20

The result from the meta-analysis of the two non-randomised clinical trials showed no significant difference between the groups in the proportion of ongoing pregnancies (RD 0.01, 95% CI –0.01 to 0.02). The result was confirmed by the RCT and the register study (figure 2c, table 1).

The results for all outcomes—complete abortion, incomplete abortion and ongoing pregnancy—showed no difference in effectiveness between self-administration of mifepristone at home compared with administration in a clinical setting, which strengthens the confidence in the result. We have judged the certainty of the evidence for no difference in effectiveness as high (table 1).

Safety

Results regarding complications and hospital care were reported in four studies (online supplemental table S4).19,2124 The proportion of serious complications were low and similar between groups in all studies. No meta-analyses were undertaken as these outcomes were rare, and the studies not designed to detect uncommon complications.

Contacts with healthcare services

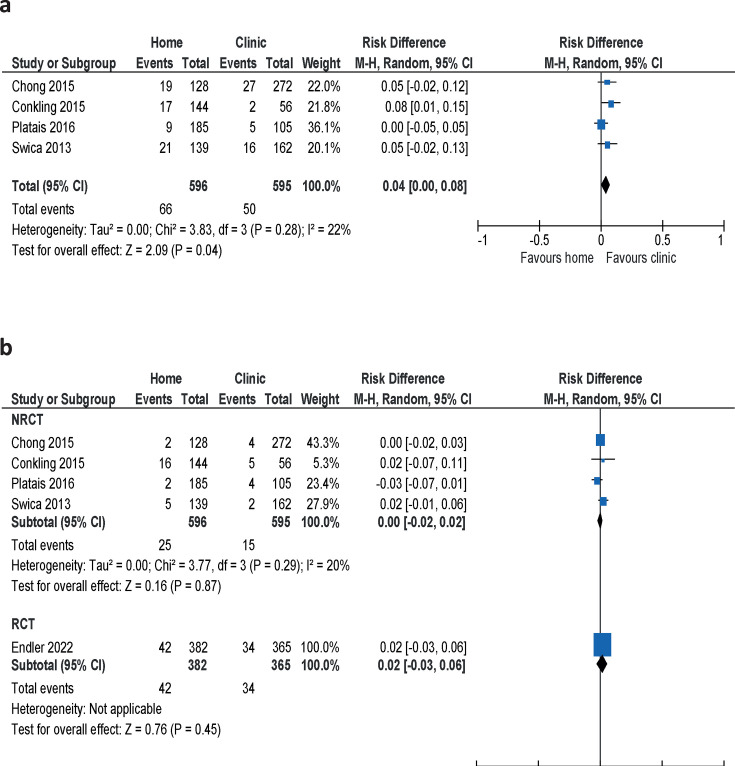

The meta-analysis of telephone contacts with the clinic, reported in four studies,21,24 showed that 4% (95% CI 0.00 to 0.08) more women in the group who took mifepristone at home made unplanned phone calls (figure 3a, table 1). No information on when these data were collected was supplied.

Figure 3. Proportion of women taking mifepristone at home compared with at a clinic who made (a) unplanned phone calls to the clinic or (b) unplanned visits to healthcare providers. NRCT, non-randomised clinical trial; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

The proportion of women who made unplanned visits to a healthcare provider showed no difference between groups in a meta-analysis of the four non-randomised clinical trials21,24 (RD 0.00, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.02) (figure 3b). The results were confirmed by the results from the RCT20; the difference was hardly detectable and considered clinically insignificant (table 1). The participants in the RCT reported unplanned visits during the follow-up 6 weeks after the abortion. The remaining four studies did not present information on how this information was gathered.

Compliance

Compliance to the prescribed abortion treatment was reported in three different ways in five studies20,24:

the proportion of women who took mifepristone within the recommended gestational age

the time interval between mifepristone and misoprostol

overall compliance (intake of the prescribed dose, recommended interval between the medications, administration route and initiation of treatment within the recommended time limits combined).

None of the studies showed any difference between home administration and administration in a clinical setting for any of the outcome measures (online supplemental table S5, table 1). In addition, compliance to the prescribed procedure was high in all studies.

Experience of the abortion

For abortion experience we abstained from a formal analysis of differences between groups. Thus, the results reported are purely descriptive for:

the proportion of women who were satisfied with the procedure and/or

the proportion of women who would choose to take mifepristone at the same place in case of a new abortion.

Two studies20 23 reported the women’s satisfaction with the procedure. The vast majority of women were satisfied with the procedure irrespective of whether they took mifepristone at home or at a clinic: 96.8% (home) versus 96.2% (clinic)23 and 96.6% (home) versus 93.7% (clinic).20

Five studies20,24 examined the preference of place for intake of mifepristone in case of a new abortion. In both groups (mifepristone at home as well as in the clinic), most women stated that they would choose the same place for intake of mifepristone in case of a new abortion (online supplemental table S6).

Practical consequences

The meta-analysis of three studies21 23 24 showed that 12% fewer women who took mifepristone at home were absent from work compared with women who took mifepristone at a clinic (RD –0.12, 95% CI –0.20 to –0.04), but there was no difference between groups in the proportion of women with absence from school (RD 0.01, 95% CI –0.09 to 0.11) (table 1 and online supplemental figure S1).

Discussion

Main findings

Our systematic review compared effectiveness, safety, acceptability and resource usage outcomes between at home versus in clinic intake of mifepristone for medical abortion. The included studies consistently demonstrate that the effectiveness of medical abortion was comparable regardless of the location of mifepristone administration. Women who took mifepristone at home showed high compliance with the prescribed treatment regimen with no significant differences observed compared with those who received it at a healthcare facility. Patient satisfaction was also high, where the majority expressed a preference for home administration of mifepristone in case of future abortions.

It is well established that home use of misoprostol in medical abortion with expulsion of the pregnancy at home is safe, effective and highly acceptable1 4 25 26 and if available preferred by a majority of patients. Only a few studies have compared administration of mifepristone at home versus in the clinic, and there are no reasons for believing that administration at one site versus the other would be less effective. The matter is mainly of legal and practical importance. Our findings align with previous evidence from observational studies supporting the safety and efficacy of self-managed medical abortion.1 5 6

Compliance with the prescribed treatment regimen is crucial for ensuring optimal outcomes in medical abortion. Our review revealed that women who took mifepristone at home exhibited comparable compliance rates to those who received it at a healthcare facility. This finding was consistent in the clinical trials and in the real-life data from the large cohort study.18 This suggests that women can effectively follow the prescribed timing and interval between mifepristone and misoprostol administration regardless of the administration site. The ability to fully tailor the timing of the whole abortion process according to their personal circumstances was a significant advantage appreciated by women opting for home administration. This is reflected in fewer days of absence from work in the group of participants who took mifepristone at home.

Strengths and limitations

While our review provides valuable insights, the number of studies specifically examining the location of mifepristone intake was relatively limited. Additionally, four of the studies were conducted by the same research group.21,24 Furthermore, all the included studies focused on abortions in the first trimester. Another limitation is that outcome definitions vary across studies due to lack of standardisation (which will hopefully improve in the future with STAR and MARE).

We were unable to perform a meta-analysis of all the included studies due to variability in outcome reporting and study design.

Only one study was an RCT and most of the included studies had a serious risk of bias. However, the fact that all the studies showed similar results despite different study designs gives reassurance for validity of the results. The results are also consistent with previous studies on self-managed medical abortion.5 Furthermore, outcomes of the large retrospective study representing real-life situations was consistent with the clinical trials. This may address the problem with generalisability of clinical trial versus real world.

In addition, the results were consistent across different treatment protocols (doses and routes for misoprostol administration and time interval between drugs), follow-up times and counselling models. In addition, the fact that studies from vastly different countries and study settings showed the same result further strengthens the findings.

Interpretation

The results are clear, and similar, across studies of different designs performed in substantially different contexts. In four of the studies, the only difference between the compared groups was the place of mifepristone administration (at home or in a clinic)21,24 whereas in two, in addition, also the counselling method (in-clinic vs telemedicine) and the method for dating the pregnancy differed.19 20

Allowing home administration of mifepristone for medical abortion, irrespective of the place of misoprostol administration and mode of counselling, may facilitate the abortion process in several ways. First of all it increases women’s autonomy and flexibility in managing their reproductive healthcare. The possibility to choose where to take mifepristone allows women to adjust the abortion procedure according to their own personal preferences and needs. The second advantage is that fewer visits to a healthcare facility can reduce costs and save time for the abortion-seeking women as well as for the healthcare system. It is, however, essential to emphasise that patients should be able to choose where to administer their medical abortion and that all choices should be offered via informed consent and shared decision-making.

Today, parts of, or all, contacts between the abortion-seeking woman and the healthcare provider can be handled digitally using telemedicine (information and counselling via internet or phone by qualified personnel).5 6 27 The current analysis did not aim to evaluate abortion via telemedicine or whether a visit for ultrasound dating was needed or not. However, allowing for counselling over distance and removing mandatory ultrasound dating of gestational age has been shown to be safe and effective and is in line with the WHO safe abortion guideline recommendation on self-managed abortion.1 7 As an example, home administration of mifepristone and misoprostol was approved in Canada in 2017, and in 2019 the demand for ultrasound was removed.28 29

Our review shows that the need for telephone contacts may increase with home use of mifepristone.21,24 However, there was no increase in unscheduled visits to healthcare providers. Good availability for telephone support is important in a high quality abortion service. High quality counselling, as well as access to support from healthcare professionals if and when needed, is stressed by the WHO.1

Conclusion

Our systematic review supports the effectiveness of home administration of mifepristone. Consequently, there seems to be no reason to withhold this option to women seeking abortion.

Women who opted for home abortion showed high satisfaction with the procedure, with most of them also expressing a preference for self-management in case of a future abortion.

Supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU: S2021/05342) funded the work with the systematic review as well as scientific external peer review of the report published in Swedish. SJ, AC, KM and EW work for SBU and participated in performing the review.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Data availability free text: NA.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.WHO . Abortion Care Guideline. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oppegaard KS, Qvigstad E, Fiala C, et al. Clinical follow-up compared with self-assessment of outcome after medical abortion: a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:698–704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ngo TD, Park MH, Shakur H, et al. Comparative effectiveness, safety and acceptability of medical abortion at home and in a clinic: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:360–70. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.084046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gambir K, Kim C, Necastro KA, et al. Self-administered versus provider-administered medical abortion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3:CD013181. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013181.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endler M, Lavelanet A, Cleeve A, et al. Telemedicine for medical abortion: a systematic review. BJOG. 2019;126:1094–102. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomperts RJ, Jelinska K, Davies S, et al. Using telemedicine for termination of pregnancy with mifepristone and misoprostol in settings where there is no access to safe services. BJOG. 2008;115:1171–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearlman Shapiro M, Dethier D, Kahili-Heede M, et al. No-Test Medication Abortion: A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:23–34. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Law . Stockholm, Sweden: 1974. Abortlag (1974: 595) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Socialstyrelsen . Stockholm, Sweden: 2009. Socialstyrelsens föreskrifter om abort (2009:15) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health and Social Care At home early medical abortions made permanent in England and Wales. 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/at-home-early-medical-abortions-made-permanent-in-england-and-wales Available. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Scottish Government Early medical abortion at home. 2022. https://www.gov.scot/news/early-medical-abortion-at-home-1/ Available.

- 12.Gemzell-Danielsson K, Brynhildsen J, Lindh I, et al. Evaluation of taking mifepristone at home during a medical abortion. PROSPERO. CRD42022344250. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, et al. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104:240–3. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schunemann HJ, Neumann I, Hultcrantz M, et al. GRADE guidance 35: update on rating imprecision for assessing contextualized certainty of evidence and making decisions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;150:225–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aiken A, Lohr PA, Lord J, et al. Effectiveness, safety and acceptability of no-test medical abortion (termination of pregnancy) provided via telemedicine: a national cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128:1464–74. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endler M, Petro G, Gemzell Danielsson K, et al. A telemedicine model for abortion in South Africa: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400:670–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01474-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chong E, Frye LJ, Castle J, et al. A prospective, non-randomized study of home use of mifepristone for medical abortion in the U.S. Contraception. 2015;92:215–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conkling K, Karki C, Tuladhar H, et al. A prospective open-label study of home use of mifepristone for medical abortion in Nepal. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;128:220–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Platais I, Tsereteli T, Grebennikova G, et al. Prospective study of home use of mifepristone and misoprostol for medical abortion up to 10 weeks of pregnancy in Kazakhstan. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;134:268–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swica Y, Chong E, Middleton T, et al. Acceptability of home use of mifepristone for medical abortion. Contraception. 2013;88:122–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiala C, Winikoff B, Helström L, et al. Acceptability of home-use of misoprostol in medical abortion. Contraception. 2004;70:387–92. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopp Kallner H, Fiala C, Stephansson O, et al. Home self-administration of vaginal misoprostol for medical abortion at 50-63 days compared with gestation of below 50 days. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1153–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds-Wright JJ, Johnstone A, McCabe K, et al. Telemedicine medical abortion at home under 12 weeks’ gestation: a prospective observational cohort study during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2021;47:246–51. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Health Canada Health Canada approves updates to mifegymiso prescribing information: ultrasound no longer mandatory. 2019. https://recalls-rappels.canada.ca/en/alert-recall/health-canada-approves-updates-mifegymiso-prescribing-information-ultrasound-no-longer Available.

- 29.Schummers L, Darling EK, Dunn S, et al. Abortion Safety and Use with Normally Prescribed Mifepristone in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:57–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa2109779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.