Abstract

Attending to the scarcity of research on the burden of occupational respiratory diseases in Türkiye, in the present registry-based epidemiological study, we investigated the incidence of occupational respiratory diseases in the country. This study is based on statistical database on occupational diseases from the Social Insurance Institution. The data from 2013 to 2023 were obtained from the official website. The results revealed that the most common occupational diseases in Türkiye are related to the respiratory system (27%). Most occupational respiratory diseases were pneumoconiosis cases (86.8%). In males, the most common disease was pneumoconioses (88.6%), while, in females, it was occupational asthma (55.4%). The annual mean incidence rate of occupational respiratory diseases amounted to 10.6 instances per 1,000,000 in the working population; it was 14.6 and 1 per 1,000,000 in males and females, respectively. The annual mean incidence rate of all pneumoconioses amounted to 9.2 per 1,000,000, while the incidence of occupational asthma was 0.7 per 1,000,000. The highest level of the incidence rate of occupational respiratory diseases—20.13 per 1,000,000—was observed in 2019. The number of patients diagnosed with occupational respiratory diseases was lower than expected. Although occupational diseases are preventable, in order to be eliminated, they must first be considered a national health problem. Therefore, the national occupational disease burden needs to be thoroughly assessed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-24014-2.

Keywords: Occupational disease, Respiratory disease, Incidence rate, Epidemiology

Introduction

The World Health Organisation’s global status report on noncommunicable diseases identifies chronic respiratory diseases as the most common diseases with significant morbidity and mortality. In low- and middle-income countries, occupational exposures, indoor air pollution, and outdoor air pollution were identified as leading risk factors for chronic respiratory diseases after smoking [1]. The respiratory system is the primary point of entry of hazardous compounds from the workplace into the body. Gases, dust, fumes, and other chemicals in the workplace can cause lung injuries [2]. The global number of deaths from workplace particulates is approximately 400,000, and the disability-adjusted life years attributable to these particulates is estimated at 6.6 million [3]. Approximately 10% of all respiratory diseases are thought to be associated with occupational exposures. Occupational lung cancer is the most common occupational cancer, and pneumoconioses continue to constitute a significant disease burden even in modern industries [4]. In the United Kingdom, approximately 1200 cases of pneumoconiosis received a disability benefit annually between 2010 and 2019 [5]. In China, 136.8 thousand new cases of pneumoconiosis were reported in 2019 [6]. In 2021, the worldwide age-standardised incidence rate for pneumoconiosis was 1.36 per 100,000 males and 0.21 per 100,000 females [7]. Overall, work-related exposure is thought to be responsible for 10–15% of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), 26% of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, 19% of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and 16% of asthma [8, 9]. Therefore, with increasing industrial development and the growth of heavy industry sectors, occupational lung diseases constitute a major public health problem in many countries. Industrial developments are causing changes in occupational hazards and exposing workers to new and unknown factors that may impair their respiratory health [2]. In addition, an ageing workforce and increased female employment may change the distribution of occupational diseases. The most important step in health surveillance and prevention measures is to monitor the frequency of diseases and changes over time. In Türkiye, previous epidemiological studies on the prevalence and incidence of occupational diseases are scarce. Seeking to fill this gap in the literature, the present study aims to evaluate the distribution of occupational respiratory diseases in Türkiye, as well as to calculate incidence rates in the working population based on legal records available in the country.

Methods

Study subjects and design

This is a retrospective epidemiological cross-sectional study that incorporated the annual statistics of occupational accidents and diseases in the Social Insurance Institution (SII) Database, Ministry of Labour and Social Insurance, Republic of Türkiye. In Türkiye, occupational disease notification is legally mandatory, and since 2007, this database has been publicly displaying all diagnosed occupational diseases nationwide every year. The database presents the number of occupational diseases classified to the affected system as separated by gender, in accordance with the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes. In addition, in the workplace statistics section, the database provides information on the total number of the country’s legally insured workers. In Türkiye, occupational diseases are diagnosed through health board reports issued by authorised hospitals. All reports prepared are sent to the SII via an electronic system, and only the SII has authority to make a certain and legal diagnosis of the occupational disease. Although the statistical database includes all numbers of cases accepted by the SII, it does not provide information about compensation numbers for occupational diseases. Accordingly, in this study, we used the numbers of insured workers and new occupational disease cases in the SII database from 2013 to 2023.

Classification of respiratory diseases

All cases were grouped and named appropriately according to ICD-10 codes [10]. All pneumoconiosis subtypes in the database (ICD-10 codes between J60 and J63.2) were collected and presented under the title of pneumoconioses. ICD-10 codes related to asthma diagnosis were coded as occupational asthma (J45.0, J45.1, J45.8, J45.9). All J68-ICD-10 codes, except for the J68.2 code, were classified as inhalation injuries of the lungs, referring to diseases caused by chemicals, gases, fumes, and vapours. Occupational upper respiratory tract diseases were formed by combining upper respiratory inflammation due to chemicals, gases, fumes, and vapours (J68.2), acute laryngitis (J04.0), other allergic rhinitis (J30.3), and other specified disorders of the nose and nasal sinuses (J34.8). Air conditioner and humidifier lung (J.67.7) cases were added under the two diagnostic codes for hypersensitivity pneumonias (J67.8 and J67.9). Furthermore, bacteriologically confirmed and not confirmed cases of respiratory tuberculosis were combined (A15 and A16). Further detail on the classification is provided in Table 1. Disease codes that were not reported within the study date range were excluded from classification (there were zero patients in the database file records for these diseases, and Supplementary Table 1 presents all ICD-10 codes related to occupational respiratory diseases in the database). Our study included 11 years of data (2013–2023), and the data before 2013 was excluded because its content was not sufficient for the study.

Table 1.

The classification of occupational respiratory diseases in the study

| Occupational respiratory disease* | Occupational diseases in the Social Security Institution data according to ICD-10 (ICD-10 code) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumoconioses | Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis | Coalworker pneumoconiosis (J60) | |

| Asbestosis | Pneumoconiosis due to asbestos and other mineral fibres (J61) | ||

| Silicosis | Pneumoconiosis due to other dust containing silica (J62.8) | ||

| Talcosis | Pneumoconiosis due to talc (J62.0) | ||

| Aluminosis | Aluminosis of lung (J63.0) | ||

| Siderosis | Siderosis (J63.4) | ||

| Other pneumoconioses | Pneumoconiosis due to other specified inorganic dusts (J63.8) | ||

| Occupational asthma | Predominantly allergic asthma (J45.0), nonallergic asthma (J45.1), mixed asthma (J45.8), asthma unspecified (J45.9) | ||

| Organic dust toxic syndrome | Airway disease due to other specific organic dusts (J66.8) | ||

| Toxic inhalation injury of lungs | Bronchitis and pneumonitis due to chemicals, gases, fumes and vapors (J68.0), pulmonary edema due to chemicals, gases, fumes and vapors (J68.1), other acute and subacute respiratory conditions due to chemicals, gases, fumes and vapors (J68.3), chronic respiratory conditions due to chemicals, gases, fumes and vapors (J68.4), other respiratory conditions due to chemicals, gases, fumes and vapors (J68.8) | ||

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | Air conditioner and humidifier lung (J67.7), hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to other organic dusts (J67.8), hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to unspecified organic dust (J68.9) | ||

| Upper respiratory tract disorders | Toxic inhalation injury of upper respiratory tract | Upper respiratory inflammation due to chemicals. gases. fumes and vapors. not elsewhere classified (J68.2) | |

| Acute laryngitis | Acute laryngitis (J04.0) | ||

| Allergic rhinitis | Other allergic rhinitis (J30.3) | ||

| Disorders of nose and nasal sinuses | Other specified disorders of nose and nasal sinuses (J34.8) | ||

| Fibrotic interstitial lung diseases | Other interstitial pulmonary diseases with fibrosis (J84.1) | ||

| Pleural disorders | Pleural effusion not elsewhere classified (J90), other specified pleural conditions (J94.8) | ||

| Larynx cancer | Malignant neoplasm of larynx (C32) | ||

| Lung cancer | Malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung (C34) | ||

| Respiratory tuberculosis | Respiratory tuberculosis bacteriologically and histologically confirmed and not confirmed (A15 and A16) | ||

| Acute tracheitis | Acute tracheitis (J04.1) | ||

ICD-10 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases

*Classified according to the 10th reference

Statistical analysis

Incidence rates were obtained by dividing the number of new cases by the number of the working population that year. Since occupational diseases are relatively rare, the incidence rate was calculated per 1,000,000 population. To calculate the annual mean incidence rate of respiratory occupational diseases, the following formula was used:

|

The proportion of each disease among respiratory occupational diseases was calculated, and the overall percentage of occupational respiratory cases among all occupational diseases was calculated separately for males and females. Supplementary Table 2 presents the annual number of diseases and the working population numbers. In this study, the Jamovi Project Program (version 2.3.2022) was used for data analyses. The Microsoft Excel program in the Microsoft 365 app for Windows was used for graphical presentations.

Table 2.

The distribution and rates of occupational respiratory diseases (the total number of patients from 2013 to 2023)

| Occupational respiratory disease | Males n (%) |

Females n (%) |

All cases n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumoconioses (all) | 2069 (88.57) | 15 (23.08) | 2084 (86.8) | |

| Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis | 399 (17.08) | - | 399 (16.62) | |

| Asbestosis | 78 (3.34) | - | 78 (3.25) | |

| Silicosis | 1543 (66.05) | 15 (23.08) | 1558 (64.89) | |

| Talcosis | 5 (0.21) | - | 5 (0.21) | |

| Aluminosis | 4 (0.17) | - | 4 (0.17) | |

| Siderosis | 15 (0.64) | - | 15 (0.62) | |

| Other pneumoconioses | 25 (1.07) | - | 25 (1.04) | |

| Occupational asthma | 129 (5.52) | 36 (55.38) | 165 (6.87) | |

| Organic dust toxic syndrome | 16 (0.68) | - | 16 (0.67) | |

| Toxic inhalation injury of lungs | 54 (2.31) | 1 (1.54) | 55 (2.29) | |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | 11 (0.47) | 1 (1.54) | 12 (0.5) | |

| Upper respiratory tract disorders (all) | 28 (1.2) | 6 (9.23) | 34 (1.42) | |

| Toxic inhalation injury of upper respiratory tract | 20 (0.86) | 1 (1.54) | 21 (0.87) | |

| Acute laryngitis | 2 (0.09) | - | 2 (0.08) | |

| Allergic rhinitis | 6 (0.26) | 2 (3.08) | 8 (0.33) | |

| Disorders of nose and nasal sinuses | - | 3 (4.62) | 3 (0.12) | |

| Fibrotic interstitial pulmonary diseases | 10 (0.43) | - | 10 (0.42) | |

| Pleural disorders | 7 (0.3) | - | 7 (0.29) | |

| Larynx cancer | 1 (0.04) | - | 1 (0.04) | |

| Lung cancer | 3 (0.13) | - | 3 (0.12) | |

| Respiratory tuberculosis | 7 (0.3) | 6 (9.23) | 13 (0.54) | |

| Acute tracheitis | 1 (0.04) | - | 1 (0.04) | |

| All occupational respiratory diseases | 2336 (97.3) | 65 (2.7) | 2401 (100) | |

ICD-10 codes are given in Table 1

Ethical approach

The data analysed in this study were downloaded from public, open websites; for that reason, ethical approval and informed consent were not obtained.

Results

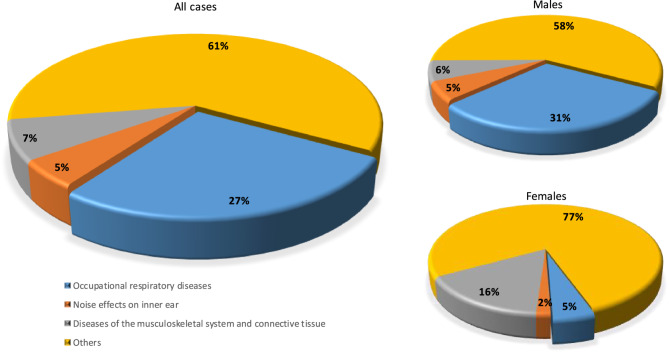

From 2013 to 2023, there were a total of 2401 cases of occupational respiratory disease in Türkiye. Among all occupational diseases, respiratory occupational diseases were the most common, accounting for 27%. Respiratory system diseases were most common in males, with a rate of 31%, whereas musculoskeletal system diseases were the most common in females, with a rate of 16%. Respiratory diseases amounted to 5% in females (Fig. 1). Pneumoconioses were the most common disease group in males (88.6%). Silicosis and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis had a significant share of all respiratory occupational diseases in males (66.1% and 17.1%, respectively). While occupational asthma was the most common respiratory occupational disease in females (55.4%), pneumoconioses ranked second (23.08%). All cases of pneumoconiosis observed in females were caused by silicosis. Occupational asthma ranked second in males, with 129 cases (5.5%). Of all cases, 2336 (97.3%) were seen in males, while only 65 (2.7%) were seen in females. Both among all cases and among males, toxic inhalation injuries stood out, ranking third after pneumoconioses and occupational asthma (n = 55, 2.3% in all cases; n = 54, 2.3% in males). The numbers and rates of occupational respiratory diseases are presented in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

The proportion of occupational respiratory diseases among all occupational diseases

The annual mean incidence rate of occupational respiratory diseases was found to be 10.6 per 1,000,000; in gender groups, this number amounted to 14.6 per 1,000,000 in males and 1 per 1,000,000 in females. Pneumoconioses accounted for a significant portion of occupational respiratory diseases, with a mean annual incidence rate of 9.2 cases per 1,000,000 population. The annual mean incidence rates of occupational asthma in males, females, and both genders amounted to 0.8, 0.5, and 0.7 per 1,000,000, respectively. Pneumoconioses had a mean incidence rate of 13 per 1,000,000 per year in males. Silicosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis had mean incidences of 9.7 and 2.5 per 1,000,000 per year in males, respectively. Furthermore, annual mean incidence rates of toxic inhalation injury were 0.3 per 1,000,000 in males and 0.2 per 1,000,000 in both genders. The annual mean incidence rates of occupational respiratory diseases are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The annual mean incidence rates of occupational respiratory diseases from 2013 to 2023 (per 1,000,000)

| Occupational respiratory disease | Males | Females | All cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumoconioses (all) | 12.93 | 0.22 | 9.18 | |

| Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis | 2.49 | - | 1.76 | |

| Asbestosis | 0.49 | - | 0.34 | |

| Silicosis | 9.64 | 0.22 | 6.86 | |

| Talcosis | 0.03 | - | 0.02 | |

| Aluminosis | 0.03 | - | 0.02 | |

| Siderosis | 0.09 | - | 0.07 | |

| Other pneumoconioses | 0.16 | - | 0.11 | |

| Occupational asthma | 0.81 | 0.54 | 0.73 | |

| Organic dust toxic syndrome | 0.10 | - | 0.07 | |

| Toxic inhalation injury of lungs | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.24 | |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.05 | |

| Upper respiratory tract disorders (all) | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.15 | |

| Toxic inhalation injury of upper respiratory tract | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.09 | |

| Acute laryngitis | 0.01 | - | 0.01 | |

| Allergic rhinitis | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| Disorders of nose and nasal sinuses | - | 0.05 | 0.01 | |

| Fibrotic interstitial pulmonary diseases | 0.06 | - | 0.04 | |

| Pleural disorders | 0.04 | - | 0.03 | |

| Larynx cancer | 0.01 | - | 0.004 | |

| Lung cancer | 0.02 | - | 0.01 | |

| Respiratory tuberculosis | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.06 | |

| Acute tracheitis | 0.01 | - | 0.004 | |

| All occupational respiratory diseases | 14.60 | 0.97 | 10.58 | |

ICD-10 codes are given in Table 1

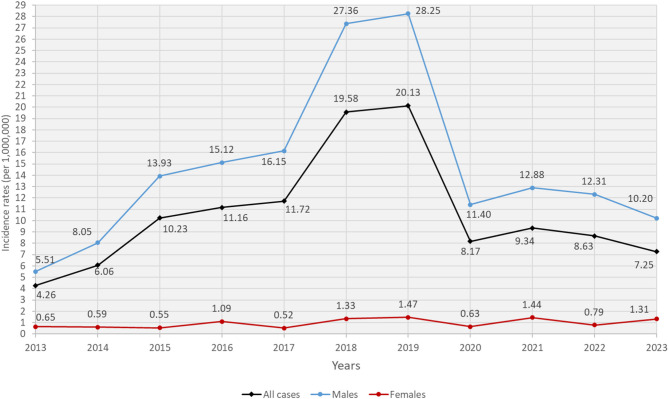

The incidence rate of all occupational respiratory diseases recorded in legal records was lowest (incidence rate: 4.26) in 2013. The most dramatic increase in the number of patients occurred in 2018. However, the peak of the incidence rate (20.13) was observed in 2019. After one year, a sharp decrease in the incidence rate was observed in 2020, and this trend persisted in 2023. The incidence rates of all occupational respiratory diseases in females remained similar throughout the study period (Fig. 2). As expected, the annual changes in the incidence rates of all pneumoconiosis cases were parallel to the incidence rates of all cases and peaked in 2019 (incidence rate: 18.74). The occupational asthma cases reached the highest incidence rate with 1.21 per 1,000,000 in 2021 (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

The incidence rates of all occupational respiratory diseases

Table 4.

The incidence rates of occupational respiratory diseases from 2013 to 2023 (per 1,000,000)

| Years | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||

| Pneumoconioses (all) | 3.77 | 5.33 | 9.27 | 10.13 | 10.14 | 17.69 | 18.74 | 6.69 | 7.01 | 7.12 | 5.60 | |

| Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis | 2.05 | 0.84 | 3.93 | 3.65 | 0.89 | 3.54 | 1.39 | 0.66 | 0.80 | 0.93 | 1.13 | |

| Asbestosis | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.79 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.13 | |

| Silicosis | 1.44 | 4.32 | 5.04 | 6.07 | 8.26 | 13.55 | 16.11 | 5.36 | 5.54 | 5.64 | 4.21 | |

| Talcosis | - | - | - | - | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | - | - | |

| Aluminosis | - | - | - | 0.05 | - | - | 0.05 | - | - | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| Siderosis | 0.06 | - | 0.05 | - | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | - | |

| Other pneumoconioses | 0.17 | - | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.10 | - | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.09 | |

| Occupational asthma | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 1.21 | 0.72 | 1.04 | |

| Organic dust toxic syndrome | - | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.08 | - | |

| Toxic inhalation injury of lungs | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 0.17 | |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | - | - | - | - | 0.05 | - | - | - | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.09 | |

| Upper respiratory tract disorders | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.09 | |

| Fibrotic interstitial pulmonary diseases | - | - | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.05 | - | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.08 | - | |

| Respiratory tuberculosis | 0.11 | - | - | - | - | 0.15 | - | 0.19 | - | - | 0.17 | |

| Other occupational respiratory diseases | - | - | - | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.09 | - | 0.08 | 0.09 | |

ICD-10 codes are given in Table 1

Discussion

Pneumoconiosis is the general term to refer to inorganic dust accumulation in the lungs and tissue reactions that develop against it [11]. Crystalline silica and asbestos are responsible for the vast majority of pneumoconiosis cases globally [12]. Approximately two-thirds (65%) of all cases during the time period of our study were silicosis cases. Silica is the most widely used mineral in the world, and the history of silicosis dates back to ancient times [13]. Major jobs that increase the risk of silicosis include foundry workers, construction workers, stonemasons, dental technicians, quarry workers, underground and surface mining jobs, metal and other mineral workers, tunnel diggers, and ceramic workers; however, exposure to silicosis can also occur in all jobs where soil and rocks are broken down or processed [14, 15]. Worldwide, silicosis poses a potentially dangerous threat to public health [16]. In China, over half a million silicosis cases were reported between 1991 and 1995 [17]. Similarly, a study in India reported that more than three million workers were exposed to silica-containing dust [18]. Silica exposure remains an important health concern in developed countries as well [19]. In the United States, for instance, it was reported that silica exposure caused a total of 1,167 deaths between 2005 and 2014 [20]. Another study found that approximately 600,000 workers in the United Kingdom and 3.2 million workers in all of Europe are exposed to silica [21]. Available data on the prevalence of silicosis in workers in Türkiye are based on regional studies [15, 22, 23]. A previous cross-sectional study showed a radiological prevalence of silicosis in 53% of former denim sandblasters [22]. Another study found that 74% of former denim sandblasters had evidence of silicosis on chest tomography scans [23]. An occupational disease polyclinic study conducted in Izmir province reported that 65.7% of referred dental technicians were diagnosed with pneumoconiosis, and 92% of the diagnosed cases had done sandblasting at some point in their working lives [15]. In our results, coal worker pneumoconiosis has a share of 17% among all occupational diseases. Similarly, in a previous meta-analysis study, the prevalence of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis in the world between 2011 and 2020 amounted to 2.29% (95% CI: 2.06 to 2.51). The three regions with the highest incidence of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis over the last 30 years are Europe, China, and the United States. Previous research emphasised that, in the last 60 years, the prevalence of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis was decreasing [24]. In Türkiye, the prevalence of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis was reported to vary between 1 and 14% [25]. This is so because, in the country, there is both environmental and occupational exposure to asbestos. In some regions, a type of soil used in the plastering and whitewashing of houses and roofs contains asbestos fibres [26]. Although asbestos was banned due to its harmful effects, asbestosis incidence rates increased globally until 2017 [27]. It is estimated that approximately 125 million workers worldwide are exposed to asbestos in their workplaces [28]. In Italy, the incidence rate of occupational cancers and asbestos-related diseases was found to be higher in workers working in workplaces with high exposure to asbestos, such as shipyards and docks [29]. A study conducted in Türkiye that examined hospital records found a total of 307 asbestos-related disease cases between 2006 and 2017, and 15% of these cases were linked to work-related asbestos exposure [30]. While most previous studies on asbestos in Türkiye focused on environmental exposure, relevant information on asbestos from an occupational perspective remains scarce [31]. One of the unexpected results of our study was the lack of cases of respiratory occupational mesothelioma. Another interesting finding is that only 3 lung cancer cases were legally recorded. By contrast, a cohort study in the Netherlands showed that occupational asbestos exposure was responsible for approximately 12% of lung cancer in men after adjusting for smoking and diet status [32]. It is estimated that approximately 40% of cancer deaths in the United Kingdom (3,500 cases per year) are due to lung cancer and mesothelioma caused by exposure to silica and asbestos in the construction industry [33]. These results can be attributed to problems in the reporting system of occupational diseases and inadequate occupational evaluation while diagnosing lung cancer and mesothelioma cases.

In our findings, occupational asthma was the second most common occupational respiratory disease after pneumoconioses. Concurrently, it was also the most common in females. In the United Kingdom, 1168 cases of occupational asthma were reported in 1999, accounting for 26% of occupational lung diseases [34]. The incidence of occupational asthma is 2–5 cases per 100,000 population annually and is the most frequently reported occupational respiratory disease [2]. Overall, numerous variables, such as gender, location, and the type, length, and intensity of workplace exposure, can affect the prevalence of occupational asthma [35]. According to Schluger et al., occupational exposures caused 11% of asthma-related mortality and morbidity, which is equal to 38,000 deaths and 1.6 million disability-adjusted life years around the world [36]. Furthermore, in a systematic analysis evaluating studies on adult-onset asthma due to occupational factors, the population-attributable risk amounted to 16.3% [37]. In the United States, the proportion of workers diagnosed with work-related asthma was reported to be 16% [38]. Available results regarding the epidemiology of occupational asthma in Türkiye are based on descriptive outpatient clinic studies and sectoral studies. In two different studies that examined the polyclinic records, Alici and Hatman found that 2.9% and 13.2% of patients had occupational asthma, respectively [39, 40]. Occupational asthma prevalence was found in various sectors in Türkiye; specifically, it was found to be 23.8% in denim bleachers, 16.78% in foundry workers, and 14.6% in hairdressers [41–43].

Toxic inhalation injury refers to the inflammatory process and clinical manifestations occurring as a result of breathing in a toxic substance, typically following an accident. Exposure to toxic substances in the workplace can lead to serious consequences, ranging from simple upper respiratory tract irritation to acute respiratory distress syndrome [44]. In the United States, an occupational exposure survey reported that over one million American workers were exposed to respiratory irritants from 1981 to 1983 [45]. Similarly, in the UK, 98 cases per year were found to be elicited by inhalation accidents at work [46]. In our study, toxic inhalation injuries were the third most common disease after pneumoconioses and occupational asthma. It also accounts for the majority of toxic injuries in upper respiratory tract diseases. Despite this, the number of acute and upper respiratory tract diseases was considerably lower as compared to other studies [45, 46]. The low incidence may result from the underestimation of the clinical relevance of these conditions by both patients and physicians. In addition, since Türkiye requires a 10% disability rate in the profession to qualify for compensation, many mild cases may not have applied to the health institution.

Occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis is an immunologic lung disease that develops due to occupational exposures [47]. In a study conducted in the United States, the incidence rate of this condition was calculated as 1.28 to 1.94 per 100,000 persons [48]. A study in the United Kingdom showed that the incidence of the disease is approximately 0.9 in 100,000 [49]. The incidence of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in the general population was reported to vary between 0.3 and 0.9 per 100,000 [50]. In the present study, the incidence rate was 0.05 per million per year, which is quite low as compared to other studies. Farmer’s lung is the most common type of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and its incidence varies according to the geographic distribution of antigens [51]. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis incidence can also be affected by climatic and environmental exposures [47]. Another unexpected result in the present study was the absence of any occupational COPD disease in the legal records. One potential reason explaining this finding is physicians’ failure to question their occupational relationships while diagnosing diseases, along with the lack of sufficient awareness of the occupational connection of diseases [52]. The results seem to indicate that the compensation-orientated registration system is seriously deficient in providing the surveillance needed to prevent occupational respiratory diseases. For that reason, it would be more beneficial to use additional and complementary surveillance systems focused on preventive measures.

With regard to gender distribution, the number of occupational respiratory diseases diagnosed in males was considerably higher than in females, both in terms of number and incidence rate. The primary reason for the disparity may be that, compared to females, males tend to work in riskier jobs related to respiratory health. Another reason is that there are more male employees in the working population. It was observed that there was an increase in the change of occupational respiratory diseases by the year 2017. The number of occupational disease specialists has started to increase in Türkiye since 2017 [53]. With this increase, it has been observed that the number of patients diagnosed has also increased. In 2020, the decline caused by the pandemic was noteworthy. The decrease may be due to the fact that all health resources were devoted to combating the pandemic, so patients did not receive the medical care they needed, which led to occupational illnesses being neglected. Since the effects of the pandemic did not disappear immediately, it took some time for health services to recover and return to pre-pandemic levels [54]. Accordingly, we believe that the expected increase in occupational lung disease diagnoses did not occur in the following years. In our study, the incidence of occupational asthma was observed to be similar throughout the study period. Similarly to our country, the incidence of occupational asthma did not demonstrate any statistically significant change over time in the European countries [55].

According to our results, the incidence of occupational respiratory diseases in Türkiye was calculated as 10.6 per 1,000,000 workers. The estimated annual incidence of occupational diseases in the Netherlands was 346 per 100,000 worker-years (95% CI 330 to 362), of which 2% were reported as respiratory diseases [56]. Furthermore, in Finland, occupational respiratory diseases were categorised as asbestos-related and allergic respiratory diseases, with average annual rates of 2.5 cases (2.4 to 2.7) and 0.9 cases (0.7 to 1.1) per 10,000 workers, respectively [57]. In Italy, the incidence of occupational respiratory diseases among agricultural workers was reported to be 19 per 100,000; in the industry and service sectors, the corresponding number amounted to 14.5 per 100,000 workers, with an increasing trend [58, 59]. Compared to other countries, the recorded incidence rates of occupational pulmonary cases in Türkiye appear to be lower than anticipated. This discrepancy suggests that many cases may go undiagnosed or unreported, possibly due to limited awareness, diagnostic complexities, or gaps in occupational health monitoring systems. First, there are glaring issues with the diagnosis procedure. Correct occupational history collection and the ability to prove a link between the illness and the job are all necessary for the diagnosis of occupational diseases [60]. However, there are not many specialists in this field available in Türkiye. As a result, it is challenging to diagnose respiratory occupational diseases because primary healthcare providers, in particular, lack necessary expertise to assess the connection between work and illness. The consequence of this lack is that occupational diseases are frequently misdiagnosed or mistaken for other illnesses [53]. Second, employees frequently fail to recognise the potential connections between their health issues and their jobs. Similarly, employers may refrain from initiating the diagnostic process due to concerns about the potential financial and legal liabilities associated with an occupational disease diagnosis [60]. In addition, workers may conceal health issues or choose not to participate in the notification process out of fear of losing their jobs [61]. Third, bureaucratic institutional barriers also adversely affect the process. The formal recognition of the diagnosis presents a systemic barrier due to the increased premium burden and compensation risk for employers [53].

The present study has several limitations. Our findings are limited by the available database that does not sufficiently address sectoral analyses of the diseases and the age groups within the population. Although we focused solely on examining data from legal records in the present study, it is clear that real-world occupational respiratory disease incidence rates are higher. In conclusion, pneumoconioses remain a serious public health problem. The low rates of occupational disease notifications in Türkiye stem from a complicated combination of socioeconomic, legal, and cultural factors, as well as various issues within the health system. To address these concerns, health professionals must first improve their knowledge of occupational diseases, streamline their diagnosis and notification procedures, and enhance workplace health and safety programs. Occupational diseases should be addressed because they are “found when looked for” and “preventable”. To reduce the health burden, it is essential to strengthen the national occupational disease diagnosis and notification system.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- SII

Social Insurance Institution

- ICD-10

10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases

Authors’ contributions

ÖG and ÖÖG made the conception and design, administrative support, provision of study materials or patients, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no funding from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Data availability

The data analysed during the present study can be found at: https://www.sgk.gov.tr/Istatistik/Yillik/fcd5e59b-6af9-4d90-a451-ee7500eb1cb4/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data analysed in this study were downloaded from publicly available websites; for that reason, ethical approval and informed consent were not obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cruz AA. Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases: a comprehensive approach. World Health Organization; 2007. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43776/9789241563468_eng.pdf.

- 2.De Matteis S, Heederik D, Burdorf A, et al. Current and new challenges in occupational lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26(146):170080. 10.1183/16000617.0080-2017. Published 2017 Nov 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driscoll T, Nelson DI, Steenland K, et al. The global burden of non-malignant respiratory disease due to occupational airborne exposures. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(6):432–45. 10.1002/ajim.20210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen RA, Go LHT, Rose CS. Global trends in occupational lung disease. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;44(3):317–26. 10.1055/s-0043-1766117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UK Department for Work and Pensions. Review and update of the prescription for prescribed disease D1: pneumoconiosis. London: UK Government. 2023. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-and-update-of-the-prescription-for-prescribed-disease-d1-pneumoconiosis/review-and-update-of-the-prescription-for-prescribed-disease-d1-pneumoconiosis. [cited 2025 Jul 9].

- 6.Li J, Yin P, Wang H, et al. The burden of pneumoconiosis in China: an analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1114. 10.1186/s12889-022-13541-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang S, Xiong J, Ruan X, Ji C, Lu H. Global burden of pneumoconiosis from 1990 to 2021: a comprehensive analysis of incidence, mortality, and socio-demographic inequalities in 204 countries and territories. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1579851. 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1579851. PMID: 40337738; PMCID: PMC12055836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanc PD, Torén K. Occupation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic bronchitis: an update. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11(3):251–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanc PD, Annesi-Maesano I, Balmes JR, et al. The occupational burden of nonmalignant respiratory diseases: an official American thoracic society and European respiratory society statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(11):1312–34. 10.1164/rccm.201904-0717ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shusterman DJ. In: LaDou J, Harrison RJ. eds. Current Diagnosis & treatment: occupational & environmental medicine, 6e. McGraw Hill; 2021. https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3065§ionid=255652128. Accessed 06 Nov 2024.

- 11.Yüksel Yavuz M, Coşkun Beyan A, Ayik Türk M, Dizdar Canbaz T, Korkmaz Özgüngör ÖM, Şafak alici N. Survival analysis of patients with pneumoconiosis followed in occupational medicine clinics: 10 years experience. BMC Pulm Med. 2025;25(1):236. 10.1186/s12890-025-03676-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cullinan P, Reid P. Pneumoconiosis. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(2):249–52. 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krefft S, Wolff J, Rose C. Silicosis: an update and guide for clinicians. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41(4):709–22. 10.1016/j.ccm.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber CM, Fishwick D, Carder M, van Tongeren M. Epidemiology of silicosis: reports from the SWORD scheme in the UK from 1996 to 2017. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(1):17–21. 10.1136/oemed-2018-105337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alıcı NŞ, Coşkun Beyan A, Demirel Y, Çımrın A. Dental technicians’ pneumoconiosis; illness behind a healthy smile–case series of a reference center in Turkey. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2018;22(1):35–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Jiang Q, Wu P, Han L, Zhou P. Global incidence, prevalence and disease burden of silicosis: 30 years’ overview and forecasted trends. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1366. 10.1186/s12889-023-16295-2. Published 2023 Jul 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung CC, Yu IT, Chen W. Silicosis. Lancet. 2012;379(9830):2008–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jindal SK. Silicosis in India: past and present. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19(2):163–8. 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835bb19e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. The world is failing on silicosis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(4):283. 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Silicosis mortality data. 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/.

- 21.Kauppinen T, Toikkanen J, Pedersen D, et al. Occupational exposure to carcinogens in the European union. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57(1):10–8. 10.1136/oem.57.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akgun M, Araz O, Akkurt I, et al. An epidemic of silicosis among former denim sandblasters. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(5):1295–303. 10.1183/09031936.00093507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozmen CA, Nazaroglu H, Yildiz T, et al. MDCT findings of denim-sandblasting-induced silicosis: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health. 2010;9:17. 10.1186/1476-069X-9-17. Published 2010 Apr 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu W, Liang R, Zhang R, et al. Prevalence of coal worker’s pneumoconiosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(59):88690–8. 10.1007/s11356-022-21966-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karadağ M, ASYOD, editors. Güncel Göğüs Hastalıkları Serisi Kitapları: Mesleki Akciğer Hastalıkları [in English: Updates on Pulmonary Diseases, Occupational Lung Disease]. Ankara: ASYOD; 2019. p. 11. Available from: http://ghs.asyod.org/Dosyalar/GHS/2019/2/a55a8788-a967-45e3-b8a1-55be4a8b0404.pdf

- 26.Turkey Asbestos Control Strategic Plan Final Report [published correction appears in Turk Thorac J. 2018 Jan;19(1):52. doi: 10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2018.01]. Turk Thorac J. 2015;16(Suppl 2):S27-S52. 10.5152/ttd.2015.10120136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Yang M, Wang D, Gan S, et al. Increasing incidence of asbestosis worldwide, 1990–2017: results from the global burden of disease study 2017. Thorax. 2020;75(9):798–800. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-214822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stayner L, Welch LS, Lemen R. The worldwide pandemic of asbestos-related diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:205–16. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larese Filon F, Granzotto J, Bignotto A, Alessandrini B, Barbina P, Rui F. Recognized occupational diseases in Italy’s Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Liguria regions (2010–2021). Med Lav. 2023;114(5):e2023044. 10.23749/mdl.v114i5.14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayram M, Özkan D, Hayat E, et al. Asbestos-related diseases in Turkey: caused not only by naturally occurring fibers but also by industrial exposures. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(5):656–9. 10.1164/rccm.201810-1922LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metintaş S, Batırel HF, Bayram H, et al. Turkey national mesothelioma surveillance and environmental asbestos exposure control program. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(11): 1293. 10.3390/ijerph14111293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Loon AJ, Kant IJ, Swaen GM, Goldbohm RA, Kremer AM, van den Brandt PA. Occupational exposure to carcinogens and risk of lung cancer: results from the Netherlands cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54(11):817–24. 10.1136/oem.54.11.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rushton L, Bagga S, Bevan R, et al. Occupation and cancer in Britain. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(9):1428–37. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer JD, Holt DL, Chen Y, Cherry NM, McDonald JC. SWORD ‘99: surveillance of work-related and occupational respiratory disease in the UK. Occup Med (Lond). 2001;51(3):204–8. 10.1093/occmed/51.3.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarlo SM, Malo JL. Third Jack Pepys Workshop on Asthma in the Workplace Participants. An official ATS proceedings: asthma in the workplace: the Third Jack Pepys Workshop on Asthma in the Workplace: answered and unanswered questions [published correction appears in Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009 Dec;6(8):728]. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(4):339–349. 10.1513/pats.200810-119ST. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Schluger NW, Koppaka R. Lung disease in a global context. A call for public health action. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(3):407–16. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-420PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torén K, Blanc PD. Asthma caused by occupational exposures is common - a systematic analysis of estimates of the population-attributable fraction. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9: 7. 10.1186/1471-2466-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazurek JM, White GE, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Work-related asthma—22 states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(13):343–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alici NŞ. A retrospective analysis of a training and research hospital’s occupational diseases outpatient clinic: where are we in diagnosing occupational diseases? J Izmir Chest Hosp 2022;33–40. https://jag.journalagent.com/igh/pdfs/IGHH-03511-ORIGINAL_RESEARCH-SAFAK_ALICI.pdf.

- 40.Hatman EA. 2019–2021 Yılları Arasında Bir Eğitim Araştırma Hastanesi İş ve Meslek Hastalıkları Polikliniğine Başvuran Olguların Özellikleri. [in English: Characteristics of the Cases who applied to the Occupational Medicine Outpatient Clinic of a Training and Research Hospital between 2019-2021. Osmangazi Tıp Dergisi. 2023;404–415. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/otd/issue/77170/1247646#article_cite.

- 41.Tutar N, Demir R, Büyükoğlan H, Oymak FS, Gülmez I, Kanbay A. The prevalence of occupational asthma among denim bleachery workers in Kayseri. Tuberk Toraks. 2011;59(3):227–35. 10.5578/tt.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kayhan S, Tutar U, Cinarka H, Gumus A, Koksal N. Prevalence of occupational asthma and respiratory symptoms in foundry workers. Pulm Med. 2013;2013:370138. 10.1155/2013/370138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akpinar-Elci M, Cimrin AH, Elci OC. Prevalence and risk factors of occupational asthma among hairdressers in Turkey. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44(6):585–90. 10.1097/00043764-200206000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rom WN, Ryon DL, David A. Diseases caused by respiratory irritants and toxic chemicals. Encyclopedia Occup Health Saf. 2011;200–36. https://iloencyclopaedia.org/part-i-47946/respiratory-system/item/411-diseases-caused-by-respiratory-irritants-and-toxic-chemicals.

- 45.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. National Occupational Exposure Survey (NOES) (1981–1983). 1990. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/noes/default.html. Accessed Sep 2024.

- 46.McDonald JC, Chen Y, Zekveld C, Cherry NM. Incidence by occupation and industry of acute work related respiratory diseases in the UK, 1992–2001. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(12):836–42. 10.1136/oem.2004.019489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akkale T, Sarı G, Şimşek C. Occupational hypersensitivity pneumonia. Tuberk Toraks. 2023;71(1):94–104. 10.5578/tt.20239911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernández Pérez ER, Kong AM, Raimundo K, Koelsch TL, Kulkarni R, Cole AL. Epidemiology of hypersensitivity pneumonitis among an insured population in the United States: a claims-based cohort analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(4):460–9. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201704-288OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solaymani-Dodaran M, West J, Smith C, Hubbard R. Extrinsic allergic alveolitis: incidence and mortality in the general population. QJM. 2007;100(4):233–7. 10.1093/qjmed/hcm008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morell F, Ojanguren I, Cruz MJ. Diagnosis of occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;19(2):105–10. 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Erçen Diken Ö, Güngör Ö, Akkaya H. Evaluation of progressive pulmonary fibrosis in non-idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-interstitial lung diseases: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24(1): 403. 10.1186/s12890-024-03226-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karabağ I, Alagüney ME, Şahan C, Yıldız AN. How difficult is it to diagnose and report an occupational disease in a developing country? A modified delphi study. Acta Med. 2023;54(4):347–56. 10.32552/2023.ActaMedica.958. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karabağ I, Şahan C, Alagüney ME, Yıldız AN. Opinions of employees on the duties, authorities, responsibilities and personal rights of occupational medicine specialists. Turkish J Public Health. 2022;20(3):329–45. 10.20518/tjph.1025980. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kitamura N, Abbas K, Nathwani D. Public health and social measures to mitigate the health and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey, Egypt, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland during 2020–2021: situational analysis. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):991. 10.1186/s12889-022-13411-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stocks SJ, McNamee R, van der Molen HF, et al. Trends in incidence of occupational asthma, contact dermatitis, noise-induced hearing loss, carpal tunnel syndrome and upper limb musculoskeletal disorders in European countries from 2000 to 2012. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72(4):294–303. 10.1136/oemed-2014-102534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van der Molen HF, Kuijer PP, Smits PB, et al. Annual incidence of occupational diseases in economic sectors in the Netherlands. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69(7):519–21. 10.1136/oemed-2011-100326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oksa P, Sauni R, Talola N, et al. Trends in occupational diseases in Finland, 1975–2013: a register study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e024040. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van der Molen HF, Marsili C, Vitali A, Colosio C. Trends in occupational diseases in the Italian agricultural sector, 2004–2017. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(5):340–3. 10.1136/oemed-2019-106168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larese Filon F, Spadola O, Colosio C, Van Der Molen H. Trends in occupational diseases in Italian industry and services from 2006 to 2019. Med Lav. 2023;114(4):e2023035. 10.23749/mdl.v114i4.14637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alaguney ME, Yildiz AN, Demir AU, Ergor OA. Physicians’ opinions about the causes of underreporting of occupational diseases. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2019;75(3):165–76. 10.1080/19338244.2019.1594663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jarolímek J, Urban P. Twenty year development of occupational diseases in the Czech republic: medical and geographical aspects. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2014;22(4):251–6. 10.21101/cejph.a4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed during the present study can be found at: https://www.sgk.gov.tr/Istatistik/Yillik/fcd5e59b-6af9-4d90-a451-ee7500eb1cb4/.