Abstract

Background

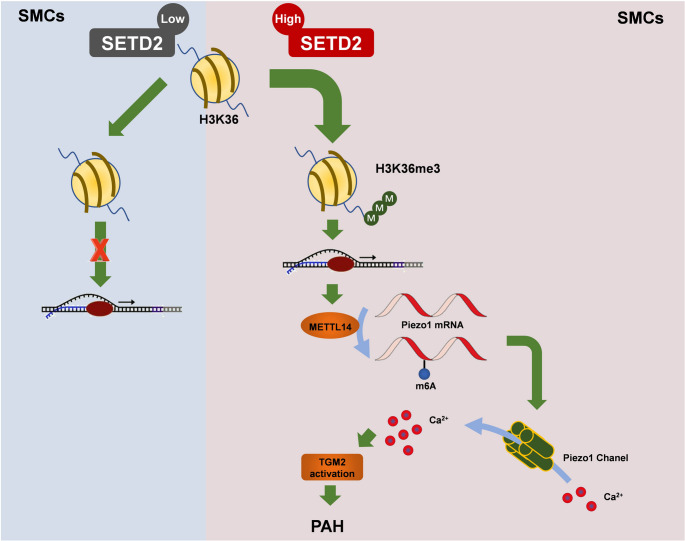

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is characterized by pathological vascular remodeling driven by pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell (PASMC) proliferation. While METTL14-mediated N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA modification has been implicated in PAH, the upstream regulators and downstream effectors linking m6A to PASMC dysregulation remain unclear. This study investigates the role of SETD2, a histone methyltransferase, in driving METTL14-dependent m6A modifications to promote PAH via Piezo1 and transglutaminase 2 (TGM2).

Methods

C57BL/6 mice were subjected to hypoxia, and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) were periodically stretched to establish PAH models in vivo and in vitro. The epigenetic regulation of METTL14 by SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 was investigated by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequence (MeRIP-seq), RNA-seq, and dual-luciferase reporter gene data were used to determine whether METTL14 enhances the expression of Piezo1 in an m6A-dependent manner. To analyze comparisons between multiple datasets, one-way ANOVA was used.

Results

METTL14 overexpression increased PASMC proliferation by 1.45-fold (vs. controls) and elevated global m6A levels by 1.73-fold in total RNA and 1.43-fold in poly A + RNA. SETD2-driven H3K36me3 histone modification upregulated METTL14 expression by 1.76-fold, amplifying m6A deposition. In hypoxia-induced PAH mice, METTL14 overexpression exacerbated hemodynamic severity, increasing right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) by 29% and mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) by 33% (vs. hypoxia alone). SETD2 knockout in PASMCs reduced RVSP by 24%, mPAP by 28%, and pulmonary artery media thickness (PAMT) by 29%, while decreasing m6A levels by 48%. Piezo1 mRNA stability increased by 2.36-fold via METTL14-mediated m6A modification at adenosine 1080, elevating Piezo1 protein expression by 3.58-fold in PASMCs. Piezo1 overexpression increased intracellular Ca²⁺ influx, driving TGM2 activity by 1.79-fold and restoring PASMC proliferation despite SETD2 deficiency.

Conclusions

This study identifies a novel SETD2/H3K36me3/METTL14/m6A axis that stabilizes Piezo1 mRNA, promoting Ca²⁺-dependent TGM2 activation and PASMC proliferation in PAH. Targeting this pathway—via SETD2, METTL14, or Piezo1 inhibition—may offer therapeutic potential to ameliorate vascular remodeling in PAH.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-025-05809-3.

Keywords: Pulmonary arterial hypertension, Epigenetic modification, SETD2, METTL14, Piezo1

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is defined as the formation of characteristic plexiform lesions caused by intimal hyperplasia, media hypertrophy and peripheral membrane proliferation of pulmonary arterioles, resulting in continuous pulmonary artery contraction and progressive occlusion [1–3]. Historically considered a uniformly fatal disease with a 10-year mortality rate of 30–40%, recent advances in targeted therapies have significantly improved survival, with 5-year survival rates now exceeding 60% in treated cohorts [4]. However, PAH remains a high-risk condition, particularly in subgroups such as connective tissue disease-associated PAH (CTD-PAH), where long-term survival remains suboptimal despite aggressive management. The therapeutic landscape has evolved dramatically with the FDA approval of sotatercept, a first-in-class activin receptor IIA-Fc fusion protein that reverses vascular remodeling by restoring balance between pro- and anti-proliferative signaling pathways (e.g., TGF-β/BMPR2). In the pivotal STELLAR trial, sotatercept reduced clinical worsening risk by 84% and improved 6-minute walk distance by 40.8 m compared to placebo, marking a paradigm shift in addressing the root cause of vascular pathology rather than merely alleviating symptoms. Despite these advances, disease progression persists in many patients, underscoring the need to elucidate novel molecular drivers of PAH beyond canonical pathways.

With the continuous progress in the field of RNA modification, the key role of epigenetics in gene expression, cell proliferation and differentiation is becoming clear. It is worth noting that N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification is the most prevalent internal modification in mRNA and plays an irreplaceable role in regulating gene expression and determining cell fate [5]. Histone methylation is based on the methylation of specific methylated residues, including lysine or arginine, affecting transcriptional or post-translational modifications [6]. It was found that histone lysine methylation (HKM) as an epigenetic regulation mode plays a key role in the proliferation, migration and contraction of PASMCs [7]. In addition, other studies indicated that SET domain containing 2 (SETD2) is critical in the cardiovascular system and that deletion of SETD2 can lead to vascular remodeling defects and lethal embryonic damage [8]. During transcription, the interaction between SETD2 and m6A RNA modifications controls gene expression. SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 can recognize and bind METTL14, recruit the m6A methyltransferase complex (MTC) to mRNA, increase RNA polymerase II activity, and enhance the m6A level of post-transcriptional mRNA [9]. Emerging evidence highlights epigenetic dysregulation as a central mechanism in PAH pathogenesis. Among epigenetic modifiers, m6A—the most abundant internal mRNA modification—has emerged as a critical regulator of vascular pathology. m6A dynamics, governed by “writers” (e.g., METTL3, METTL14), “erasers” (e.g., FTO, ALKBH5), and “readers” (e.g., YTHDF proteins), control RNA stability, splicing, and translation [10]. Recent studies implicate m6A dysregulation in PAH: Inhibition of METTL3 by STM2457 and Loss of Macrophage METTL3 Alleviate Pulmonary Hypertension and Right Heart Remodeling [11]. FTO, an m6A eraser, its deletion mitigates hypoxia-induced PAH [12]. Loss of m6A demethylase ALKBH5 alleviates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension via inhibiting Cyp1a1 mRNA decay [13]. Our prior work uniquely identified METTL14—a critical scaffolding component of the m6A methyltransferase complex—as a hypoxia-sensitive driver of PAH [14]. In hypoxia-induced PAH models, SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 recruits METTL14 to enhance m6A deposition, amplifying PASMC hyperproliferation and vascular remodeling. While METTL3 and FTO have been studied in PAH, METTL14’s role is distinct: its interaction with histone modifiers like SETD2 creates an epigenetic-metabolic feedback loop that perpetuates vascular pathology under hypoxia. However, the downstream effectors linking this epigenetic axis to pathological vascular remodeling remain poorly defined, particularly in non-hypoxic PAH models. This mechanistic uniqueness justifies our focus on METTL14 rather than other m6A regulators in the current study.

Shear stress is fundamental to cardiovascular biomechanics, and Piezo1, a recently discovered stretch-activated ion channel, is widespread throughout the cardiovascular system [15]. Notably, intense pulmonary artery contraction induced by increased shear stress stimulation of stretch-activated ion channels (SACs) plays a vital role in malignant pulmonary vascular remodeling in PAH [16]. Piezo1, a core member of SACs, senses exogenous pressure and promotes Ca2+ influx [17]. Sustained activation of Piezo1 in SMCs significantly increases intracellular Ca2+ concentration, which in turn activates transglutaminase2 (TGM2) and promotes arteriolar remodeling in hypertensive patients [18]. While Piezo1-TGM2 signaling is mechanistically plausible in PAH, the regulatory interplay between epigenetic RNA modifications and this mechanotransduction cascade has never been investigated. Furthermore, whether m6A modulates Piezo1 expression or activity—and how this impacts TGM2-driven vascular pathology—remains unknown.

In this study, we uncover two novel mechanistic axes that expand the understanding of PAH pathogenesis beyond canonical hypoxia-driven pathways. First, we demonstrate that SETD2/METTL14-mediated m6A modifications suppress Piezo1 mRNA stability, attenuating its expression and disrupting calcium homeostasis in PASMCs. Second, we identify TGM2 as a critical downstream effector of Piezo1 attenuation, where reduced Piezo1 activity unleashes TGM2-driven vascular remodeling independent of hypoxia. These findings reveal an unprecedented link between epitranscriptomic regulation (m6A), mechanosensitive ion channel dynamics (Piezo1), and post-translational matrix modulation (TGM2) in PAH. By delineating how m6A-dependent RNA decay of Piezo1 licenses TGM2 activation, this work provides a transformative perspective on PAH pathophysiology and positions the SETD2/METTL14-Piezo1-TGM2 axis as a therapeutic target worthy of clinical exploration.

Materials and methods

Animals and ethics

All the animal experiments adhered to the NIH guidelines. The Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanchang University approved the protocols (Approval No. CDYFYIACUC-202412QR005).

SM22 (α-SMA-Cre) transgenic mice (8 weeks old, weighing 18–22 g, male, SPF grade) were obtained from Shanghai Slack Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). SETD2fl/flC57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old, weighing 18–22 g, male, SPF grade) were provided by the Shanghai Lab. Animal Research Center (Shanghai, China). The animals were kept on a 12:12-hour light‒dark cycle and were provided free access to water and food. Conventional homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells was employed to mate SETD2fl/flC57BL/6 mice with SM22(α-SMA-Cre) C57BL/6 mice, thereby obtaining C57BL/6 mice that express two Flox and Cre enzymes. The SETD2 gene was then knocked out in smooth muscle cells (SMCs), resulting in the generation of SETD2−/− C57BL/6 mice [14].

Construction of a mouse PAH model

The C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old, weighing 18–22 g, male, SPF grade) were randomly divided into two groups: the normoxia group, which was exposed to indoor air, and the hypoxia group, which was placed in a ventilation chamber with 10% O₂ and < 0.5% CO₂ achieved by mixing indoor air with nitrogen. The RCI Hudson detector (Anaheim, CA, USA) was programmed for automatic oxygen concentration monitoring and control. The PAH mouse model was established after a 4-week feeding period [19].

AAV9 delivery and tropism validation

AAV9 vectors expressing METTL14 (AAV9-METTL14) or scramble control (AAV9-scramble) under the α-SMA promoter (1 × 1011 viral genomes/mouse) were administered via ultrasound-guided intratracheal instillation at the onset of hypoxia exposure, as previously described [20]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and 50 µL of AAV9 suspension was delivered into the trachea using a MicroSprayer® aerosolizer (Penn-Century, USA).

Echocardiographic examination

An intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg) was used to anesthetize the mice. Once their hindlimb reflexes had ceased, the mice were placed in a supine orientation on the physiological information monitoring table at 37°C. Echocardiography was performed with a Vevo 2100 high-resolution imaging system (Visual Sonics, Inc.) with an MS400 probe (frequency, 30 MHz). The following measurements were taken: right ventricular end-systolic diameter (RVESD), right ventricular end-systolic volume (RVESV), right ventricular end-diastolic diameter (RVEDD), right ventricular end-diastolic volume (RVEDV), right ventricular fraction of contraction (RVFS), right ventricular posterior wall thickness (RVPWT), and ventricular septal thickness (IVST). The data were averaged over 3 consecutive cardiac cycles. The right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) and the RR interval-adjusted pulmonary artery flow acceleration time (PAAT) were calculated. All echocardiographic studies were analyzed in a blinded manner.

Hemodynamic detection

Following echocardiography, a pressure sensor (FTH-1211B-0018, Primetech) with a 25-G needle was inserted into the right external jugular vein for the measurement of right ventricular mean pressure (RVMP), right cardiac displacement (RVCO), and right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP). Systolic body pressure (SBP) and systemic arterial pressure (mSAP) were measured via left carotid artery intubation. All calculations were performed via LabChart8 (ADInstruments) to determine the mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) and total pulmonary resistance (TPR) on the basis of the ratio of mPAP to RVCO.

Histologic analysis

Following the hemodynamic examination, all the animals were euthanized via CO₂ inhalation and underwent thoracotomy. The heart and lungs were excised, and the left and right lung tissues were dissected and utilized for vascular studies [21]. Following removal of the vessels, the left and right ventricles and the ventricular septum were separated, and the Fulton index was calculated as the ratio of right ventricle/(left ventricle + septum) (RV/(LV + S)) to evaluate cardiac function. Mouse lung tissue was fixed with 4% formaldehyde and paraffin embedded via standard histological methods. Continuous sections with a thickness of 5 μm were obtained. The paraffin sections were deparaffinized, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, sealed with neutral glue, and stored. A microscope (Olympus, CKX53) was used to observe the samples, and high-quality images were captured for subsequent analysis.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Lung sections were prepared in accordance with the methodologies used for histological analysis, and mouse lung tissues were analyzed by immunofluorescence [22]. Fluorescently labeled anti-METTL14 (1:400, 26158-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-SETD2 (1:300, 55377-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-α-SMA (1:500, 14395-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), and anti-Piezo1 (1:200, 15939-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) antibodies were added for 60 min, and the slices were washed twice in PBS. The slides were subsequently covered with VECTASHIELD® Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA), which contains the nuclear stain DAPI. The samples were analyzed via confocal microscopy (LSM800, Zeiss, Germany).

hPASMC culture

Normal human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs) were procured from Pricella (Cat. No. CP-H236 1, Wuhan, China) and cultured in medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were incubated in a 5% CO₂ incubator at 37°C. The culture medium was replaced daily, and the cells were passaged every 3 days. The PAH model was created in vitro through the application of cyclic stretch (CS, 1 Hz) to hPASMCs within a FlexCell 3000 Strain Unit for a period of 72 h [23].

CCK-8 analysis

The hPASMCs were inoculated into 96-well culture plates (100 µl/well) for routine culture. Following a 48-hour incubation period, CCK-8 solution (20 µl) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. In the absence of hPASMCs, only 100 µl of culture solution and 20 µl of CCK-8 reagent were added to the blank well. The absorbance was determined at 450 nm via an enzyme-labeled instrument (9200, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), with 5 replicates per group. The cell viability was determined via the formula [(AS-AB)/(AC-AB)]*100%, where AS represents the experimental sample, AC represents the control sample, and AB represents the blank sample.

Cell multiplication analysis

The hPASMCs were inoculated into 96-well plates (5,000 cells/well) and cultured until the cell density reached approximately 60%. BrdU (Cat. No. ST1056; Beyotime, Nanjing, China) (0.03 µg/ml) was added to the culture plate, which was subsequently incubated for 24 h. Then, 200 µl of fixative solution was added to each well, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min to fix and denature the DNA. Subsequently, HCl (1.5 mmol/L) was added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. A BrdU monoclonal antibody (1:1000, 66241-1-Ig, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) was then added, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The Gold Anti-Fade Reagent with DAPI (Cat. No. C1005; Beyotime, Nanjing, China) was added, and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, 100 µl of TMB substrate solution was added to each well for color development, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. The termination solution was then added to halt the reaction. The reactions were observed and photographed via confocal microscopy (LSM800, Zeiss, Germany), and the resulting images were analyzed via the J Image-Pro Plus_6.0 software system. Each group consisted of 5 compound wells, a blank control group with no cells containing BrdU, and a background control group with cells but without BrdU (the OD values of both groups were less than 0.1).

Western blot

Western blot analysis was conducted on freshly isolated mouse whole lung tissue, freshly isolated pulmonary artery tissue, and cultured hPASMCs via standard methods. The tissues and cells were lysed with cold radioimmunoprecipitation cell lysis buffer (RIPA) (Cat. No. P0013C; Beyotime, Nanjing, China) and subsequently subjected to centrifugation at 4°C (12,000 × g, 15 min). The pyrolysis products were boiled at 100°C with 6 × loading buffer (Beyotime) for 8 minutes and then stored at -80°C for subsequent analysis. The proteins were separated via SDS‒PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (MerckMillipore, USA), which was then sealed with skim milk powder. The membrane was subsequently incubated with the corresponding primary antibody at 4°C overnight. On the following day, the PVDF membrane was washed and incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 hour. The chemiluminescence signals were visualized with a Tanon 5300 (Shanghai, China), and the image gray values were analyzed with ImageJ software. The primary antibodies used in this study are as follows: anti-α-SMA (1:1000, 14395-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-collagen I (1:1500, 39952, CST, USA), anti-PCNA (1:1,000, Cat. No. sc-25280, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Cyclin A1 (1:1000, 13295-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-cyclin D1 (1:2000, 26939-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-cyclin E1 (1:1000, 11554-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-SETD2 (1:1000, 55377-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-H3K36me3 (Danvers, MA, USA), anti-METTL3 (Danvers, MA, USA), anti-METTL14 (1:1500, 26158-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-Piezo1 (1:2000, 15939-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), and anti-TGM2 (1:1) antibodies The secondary antibodies used were goat anti-mouse (1:6,000, AS003, ABclonal, China) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:6,000, AS014, ABclonal, China).

Total m6A levels

The TriZor kit (Thermo Fisher) was used to extract total RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the GenElute™ mRNA micropreparation kit (Sigma‒Aldrich, Germany) was used to purify polyadenylate mRNA. The total m6A levels were subsequently quantified via the EpiQuik™ m6A RNA Methylation Quantitative Kit (Epigentek, USA). Next, 500 ng of RNA was added to each well, after which the samples were subjected to antibody capture and detection. Following a series of incubations, the m6A levels were detected via a colorimetric method at a wavelength of 450 nm, with the results expressed as a function of the standard curve.

PolyA + RNA was extracted from total RNA via the polyA + Tract mRNA Isolation System IV and subsequently purified and quantified. Following denaturation, the sample was applied to an Amersham Hybond-N + membrane with a Bio-Dot (GE Healthcare), and the purple membrane was washed with 1× PBST buffer (Thermo Scientific) and sealed with 5% skim milk. The slides were incubated with an anti-m6A antibody (1:2000, Synaptic Systems) overnight at 4°C. Then, HRP-coupled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The sample was subsequently imaged via a chemiluminescence apparatus. The relative signal density at each point was determined via Gel-Pro analysis software [24, 25].

Dot blot

RNA was extracted from cells or tissues via RNAiso + reagent (#9109, Takara) and transferred to an Amersham Hybond-N + membrane (GE Healthcare, USA). Following ultraviolet crosslinking and washing with PBST, the total amount of RNA extracted was determined by scanning after the samples were stained with 0.02% methylene blue (#M9140–25G, Sigma‒Aldrich). The membrane was subsequently incubated with specific m6A antibodies (1:2000, #202003, Synaptic Systems) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with 5% skim milk. After incubation with the secondary antibody, the spots were imaged via a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP imaging system.

Ca2+ detection

A solution of 1 mg of Fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester (Fluo-4 AM) (HY-101896, MCE, China) in 442 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was prepared to a concentration of 2 mM, and 16.5 mg of pluronic F127 (ST501, Beyotime, Nanjing, China) was added. The Fluo-4 AM solution was diluted with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) buffer to yield a 4 µM Fluo-4 AM solution. The prepared Fluo-4 AM solution was then added to the cells, and the culture was maintained at 37°C for approximately 20 min. Following the addition of a volume of HBSS buffer containing 1% fetal bovine serum fivefold greater than the initial volume, the culture was continued for approximately 40 min. The cells were washed 3 times with HEPES-buffered saline (10 mM HEPES, 1 mM Na₂HPO₄, 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl₂, 0.5 mM MgCl₂, 5 mM glucose, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4). The cells were resuspended in HEPES-buffered saline to create a solution with a concentration of 1 × 10⁵ cells/ml. The culture was subsequently incubated at 37°C for approximately 10 min, after which the calcium ions were detected via confocal microscopy (LSM800, Zeiss, Germany). (Excitation wavelength: 494 nm; emission wavelength: 516 nm)

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from PASMCs and tissues with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and RNA (1000 ng) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA via a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Real-time PCR was conducted via the 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies, Waltham, USA), with SYBR Green as the fluorescent dye. The relative mRNA expression levels were calculated via the 2−ΔΔCt method, and ACTB was used as the reference gene for normalization.

MeRIP

The m6A modification of Piezo1 mRNA was detected via the Ribo MeRIP m6A transcriptome analysis kit (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China). In brief, approximately 50–100 mg of total RNA was isolated and fragmented via RNA fragment buffer, with 1/10 of the RNA fragment serving as the input group. A/G magnetic beads were then prewashed and combined with an anti-m6A antibody. Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) reaction buffer was added to A/G magnetic beads, which were subsequently incubated at 4°C for 2 h. The conjugates were purified and eluted with a Magen Hipure serum/plasma miRNA kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China) for subsequent qPCR analysis.

RNA-Seq

RNA-Seq was slightly modified from Shanghai Oebiotech Co., Ltd., according to published procedures [26]. RNA-seq libraries were generated via the NEBNext® Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, Inc., USA) for both the input sample without immunoprecipitation and the m6A IP samples. The libraries were evaluated on a Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq instrument.

ChIP

The concentration of H3K36me3 in the promoter region of METTL14 was quantified via a ChIP detection kit (CST, 9005 S). In brief, PASMCs are fixed with formaldehyde to establish a cross-link between the protein and DNA. Ultrasonic processing is employed to achieve the optimal size for the DNA. The chromatin protein complex was subsequently incubated with the positive control group protein H3 (1:100, 17168-1-AP; Proteintech, Wuhan, China) and the negative control normal rabbit IgG antibody (1:100, 30000-0-AP; Proteintech, Wuhan, China) at 4°C overnight. The sample was subsequently incubated with ChIP-grade protein G magnetic beads at 4°C for a period of 2 h. The elution of chromatin from the antibody/protein G magnetic complex is followed by the reverse cross-linking of DNA from the protein/DNA complex. Finally, the DNA was purified via spin column purification and stored for later analysis via qPCR.

Luciferase reporter gene analysis

The CDS and 3’ UTR regions of Piezo1 were cloned and inserted into a pGL3 control vector (Promega, USA) containing firefly luciferase (F-luc), with the predicted adenine (A) in the m6A motif of the 1080 mutant reporter plasmid replaced with thymine (T). The pretreated SMCs were inoculated into a 24-well plate and then cotransfected with 0.5 µg of the wild-type or mutant Piezo1 reporter plasmid and 25 ng of the pRL-TK plasmid (renal luciferase reporter vector) via the jetPRIME Polyplus Kit. Following a 24- to 36-hour incubation period, the cells were collected, and luciferase activity was quantified with the Dual-Glo Luciferase System (Promega, USA). The data were normalized to those of pRL-TK. This process should be repeated three times per set.

Statistical analysis

The aforementioned experiments were conducted in triplicate. The data were subjected to statistical analysis via GraphPad Prism 9. The values are expressed as the means ± SDs, and Student’s t test was used to analyze the direct differences between the two groups. Two-Way ANOVA and non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn’s post hoc correction was used to compare multiple datasets. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

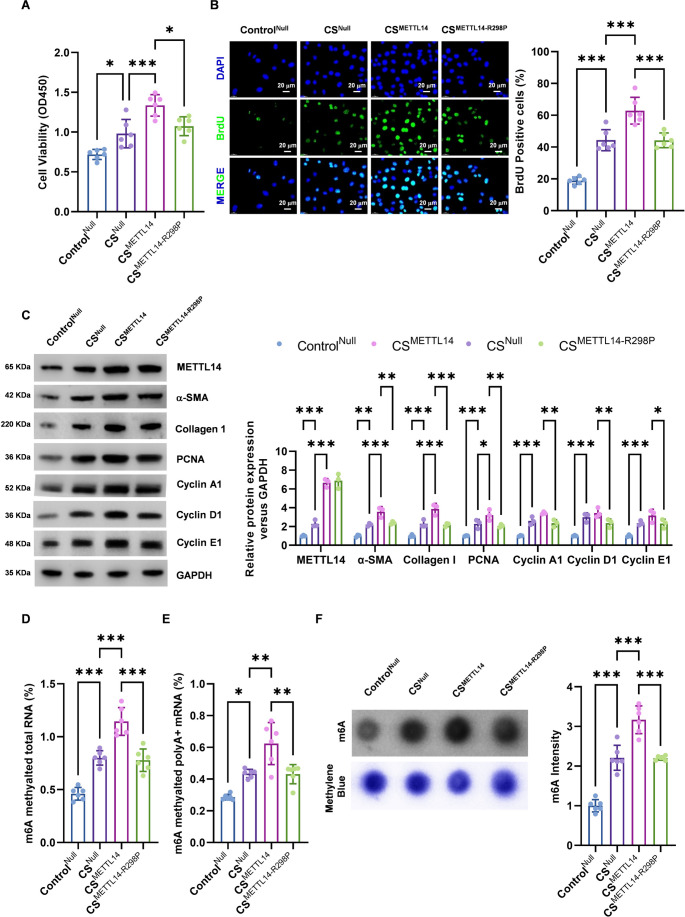

METTL14 increases m6A levels and promotes the proliferation of PASMC

In vitro studies found that the activity and proliferation capacity of hPASMCs were significantly increased in PAH group, and it is worth noting that CSMETTL14 group showed the most obvious enhancement (Fig. 1A, B). Western blotting revealed that the expression levels of cell proliferation markers were markedly elevated in the experimental group. Among these, the CSMETTL14 group presented the most pronounced increase (Fig. 1C). These findings indicate that the overexpression of METTL14 markedly enhances the proliferation of PASMCs. The levels of mRNA m6A in total RNA and poly A + RNA were subsequently quantified via a colorimetric assay. Compared with that in the control group, the expression level of m6A in PASMCs in the PAH group was markedly increased, with the CSMETTL14 group serving as the primary focus (Fig. 1D, E). Furthermore, dot blot analysis confirmed that the total m6A level was markedly elevated in PASMCs transfected with a METTL14 overexpression virus (Fig. 1F). Western blotting further confirmed that METTL14 expression was significantly upregulated in the PAH group (Fig. 1C). In conclusion, the in vitro experiments demonstrated that METTL14 increased the m6A level in SMCs and facilitated the proliferation of PASMCs.

Fig. 1.

METTL14 increases m6A levels and promotes the proliferation of PASMCs. First, two adeno-associated virus (AAV) expression vectors were constructed: the wild-type METTL14 AAV (AAV9-METTL14) and the methyltransferase-mutant METTL14 AAV (AAV9-METTL14-R298P). These vectors were then used to infect human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs). The PAH model was subsequently developed in vitro through the application of cyclic stretch (CS, 1 Hz) with the FlexCell 3000 Strain Unit for a period of 72 h. The ControlNull, CSNull, CSMETTL14, and CSMETTL14−R298P groups were established with a no-load adeno-associated virus expression vector (AAV9-Null) as the ControlNull. (A) CCK-8 detection of cell activity. (B) Cell proliferation was detected by BrdU staining. (C) Western blot detection of the protein expression of METTL14, α-SMA, collagen I, PCNA, cyclin A1, cyclin D1, and cyclin E1. (D-E) mRNA m6A levels of total RNA and poly A + RNA were detected via colorimetry. (F) Dot blot assay for m6A levels in total RNA, the methylene blue staining was used as loading control. (n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

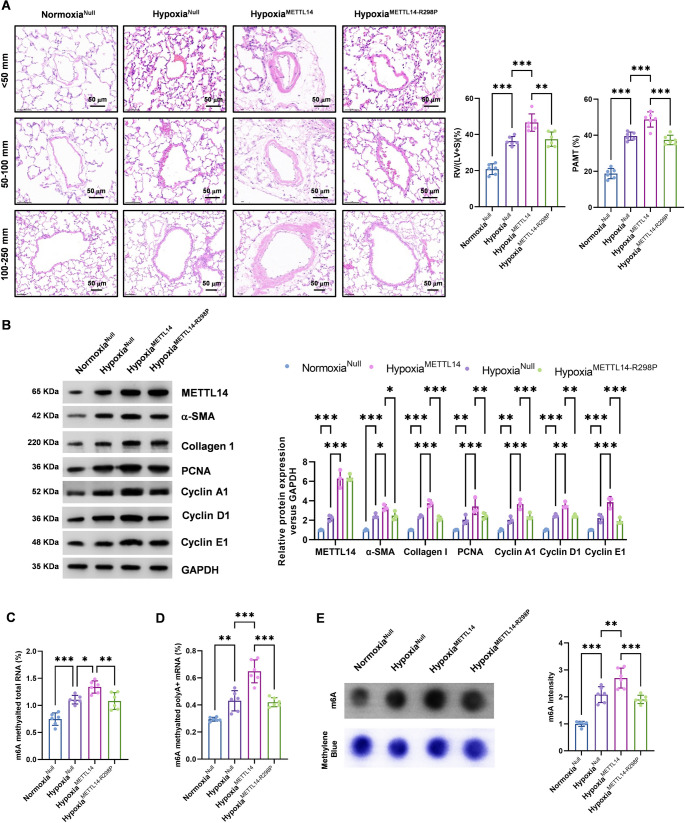

METTL14 promotes pulmonary artery remodeling and triggers PAH

To investigate the effect of METTL14 on PAH in vivo, we conducted an in vivo experimental study. First, the METTL14 vectors were delivered into the trachea by a 24G catheter to infect the lungs of C57BL/6 mice [27]. The right heart catheter test demonstrated that, compared with those in the normoxia group, the RVMP, RVSP, TPR, and mPAP were markedly elevated in the hypoxia group, whereas the RVOC was notably decreased. The HypoxiaMETTL14 group presented the most pronounced alterations. However, no significant differences were observed in SBP or mSAP among the groups (Supplementary Fig. 1 A). The above study revealed that the PAH model was successfully established in mice subjected to 10% O₂ hypoxia for 4 weeks and that there was no significant effect on systemic blood pressure. Notably, METTL14 overexpression significantly exacerbated PAH. The results of echocardiography revealed notable increases in RVEDD, RVEDV, RVESD, and RVESV in the hypoxia group, whereas RVESV, RVFS, RVEF, and PAAT significantly decreased. The HypoxiaMETTL14 group presented the most significant results (Supplementary Fig. 1 B and 1 C). These findings indicate that mice with pulmonary hypertension induced by hypoxia, particularly those with METTL14 overexpression, exhibit obvious right ventricular dysfunction.

We subsequently evaluated the Fulton index, which is a crucial indicator of right ventricular hypertrophy resulting from increased right ventricular pressure and afterload. Firstly, to determine whether METTL14 overexpression alone drives PH, we administered AAV9-METTL14 to normoxic mice. No significant differences in the RV/(LV + S) ratio or PAMT were observed (Supplementary Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2C, the RV/(LV + S) ratio in mice subjected to hypoxia was notably greater than that in the control group, particularly in the HypoxiaMETTL14 group. HE staining revealed notable thickening of the pulmonary artery wall in the hypoxia group, accompanied by considerable elevation in pulmonary artery relative media thickness (PAMT), particularly in the hypoxiaMETTL14 group (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, western blot analysis revealed notable increases in the expression levels of cell proliferation markers (Fig. 2B). These findings indicate that hypoxia can induce pulmonary artery remodeling and right ventricular dysfunction in mice and that METTL14 overexpression significantly exacerbates these manifestations.

Fig. 2.

METTL14 promotes pulmonary artery remodeling and induces PAH. The AAV9-METTL14 and AAV9-MettL14-R298P vectors were constructed, and 1 × 10¹¹ vg/75 µl adeno-associated virus vectors were delivered into the trachea by a 24G catheter to infect the lungs of C57BL/6 mice. Experiments were performed with four groups, including Normoxia (AAV9-Null, 21% O₂), HypoxiaNull (AAV9-Null + hypoxia), HypoxiaMETTL14 (AAV9-METTL14 + hypoxia), HypoxiaMETTL14−R298P (AAV9-METTL14-R298P + hypoxia). (A) Pulmonary artery wall thickness (< 50 mm, 51–100 mm, > 100 mm) and pulmonary artery relative medial thickness (PAMT) were measured via HE staining. The mass ratio of RV/(LV + S) was calculated. (B) The expression levels of METTL14, α-SMA, collagen I, PCNA, cyclin A1, cyclin D1, and cyclin E1 were detected via Western blotting. (C-D) mRNA m6A levels of total RNA and poly A + RNA were detected via colorimetry. (E) Blot analysis of the m6A levels of total RNA, the methylene blue staining was used as loading control. (n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

A comparison was subsequently conducted to determine the expression of METTL14 in each group. Western blot analysis revealed that hypoxia markedly elevated METTL14 levels in SMCs (Fig. 2B). To further analyze the expression of m6A in each group, colorimetry was employed to detect the mRNA m6A expression levels of total RNA and poly A + RNA. These data indicated that the expression level of m6A in the hypoxia group was significantly greater than that in the control group. Among these groups, the hypoxiaMETTL14 group presented the most significant results (Fig. 2C, D). In addition, dot blot analysis revealed the same results (Fig. 2E). These findings suggest that METTL14 facilitates m6A modification, contributing to pulmonary artery remodeling and the development of PAH.

SETD2 mediates H3K36me3, promotes METTL14 expression, and promotes PASMC proliferation

We have found that SETD2 overexpression markedly enhanced the proliferation of PASMCs (Fig. 3A-C). Interestingly, western blot analysis revealed a notable increase in H3K36me3 expression in the SETD2 group compared with the ControlNull group (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that SETD2 may play a key role in the proliferation of PASMCs by regulating H3K36me3. Subsequently, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed. ChIP‒qPCR analysis revealed significant upregulation of H3K36me3 in the PAH group, and the expression level of H3K36me3 was most significantly elevated in cells transfected with the SETD2 gene (Fig. 3D). These findings indicate that SETD2 regulate the expression of METTL14 through H3K36me3, thereby promoting the proliferation of PASMCs. The m6A expression levels of total RNA and poly A + RNA were subsequently quantified via colorimetric assay. The results demonstrated a notable increase in m6A expression levels in the PAH group relative to those in the control group, and the CSSETD2 group presented the most significant results (Fig. 3E, F). Furthermore, dot blot analysis showed similar results (Fig. 3G). These findings indicate that SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 and METTL14-mediated m6A modifications are pivotal in the pathogenesis of PAH.

Fig. 3.

SETD2 affects H3K36me3, promotes METTL14 expression, and promotes the proliferation of PASMCs. The SETD2 adenovirus expression vector (Ad-SETD2) was constructed for infection of hPASMCs, and Control infected with the empty Ad-Null was used as a control. The in vitro model of PAH was established by CS for 72 h. The following groups were included in the study: ControlNull, CSNull, ControlSETD2, and CSSETD2. (A) CCK-8 detection of cell activity. (B) Cell proliferation was detected by BrdU staining. (C) Western blot analysis was performed to detect the protein expression of SETD2, METTL14, α-SMA, collagen I, PCNA, cyclin A1, cyclin D1, cyclin E1, H3K36me3, and H3K36. (D) H3K36me3 expression was detected via ChIP‒qPCR. (E-F) mRNA m6A levels of total RNA and poly A + RNA were detected via colorimetry. (G) A dot blot assay was used to detect m6A levels in total RNA, the methylene blue staining was used as loading control. (n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

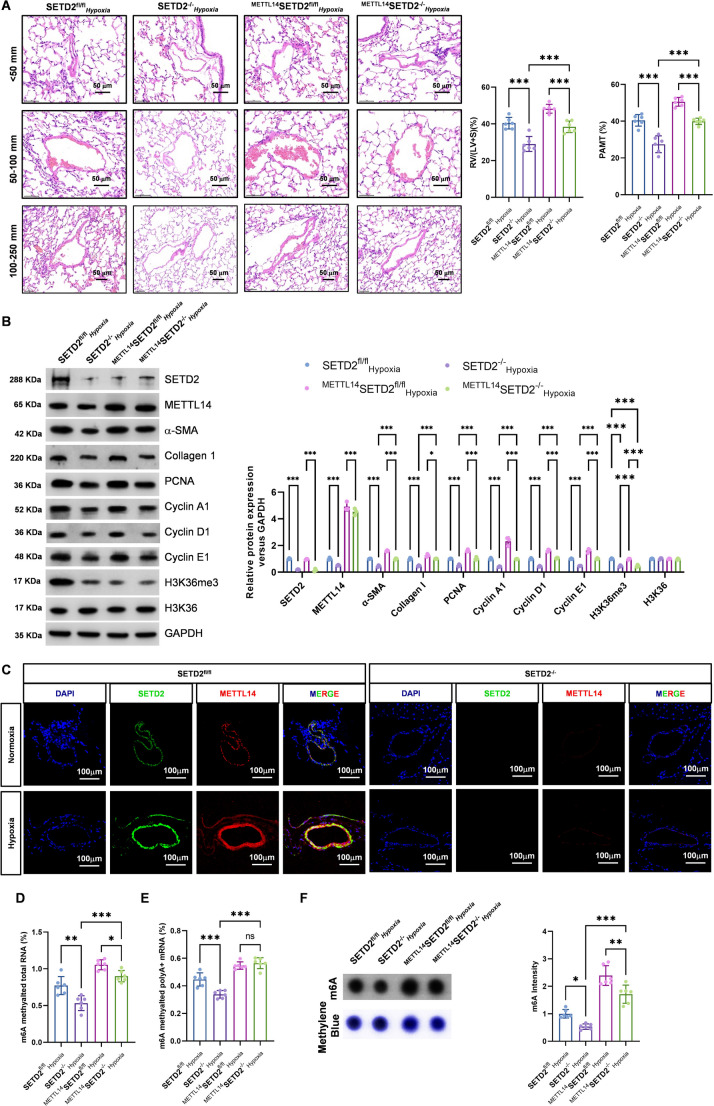

SETD2 drives METTL14 expression and induces PAH

To further investigate the role of SETD2 in vascular remodeling in PAH, in vivo experiments were performed. The results of right cardiac catheterization revealed that RVSP, mPAP and TPR were notably decreased and that RVCO was significantly increased in SMC-specific SETD2-deficient mice (Supplementary Fig. 3 A). These findings suggest that silencing the SETD2 gene in SMC cells can effectively inhibit PAH. Next, we analyzed the effects of SMC-specific SETD2 defects on right ventricular function in PAH model mice via echocardiography. We have found that silencing the SETD2 gene in SMCs can significantly improve PAH-induced right ventricular dysfunction (Supplementary Fig. 3 B and 3 C). Subsequently, we analyzed the effects of SETD2 knockout in SMCs on pulmonary pathological remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy via histological analysis. As shown in Fig. 4A, SETD2 gene silencing in SMCs significantly reduced the RV/(LV + S) ratio. HE staining revealed that SMC-specific SETD2 deletion significantly reduced PAMT and pulmonary remodeling in mice. Furthermore, western blot analysis demonstrated that the expression of cell proliferation markers were markedly diminished in SETD2-deficient SMCs derived from model mice (Fig. 4B). These findings implies that the knockout of SETD2 in SMCs profoundly reverses the pathological remodeling of pulmonary arteries in PAH and notably improves right ventricular function.

Fig. 4.

SETD 2 induced PAH via METTL14. First, Ad-METTL14 and AdMETTL14-R298P were constructed and delivered to the lungs of mice infected with SETD2−/−C57BL/6 through an air tube. The SETD2fl/flHypoxia, SETD2−/−Hypoxia, METTL14SETD2fl/flHypoxia, and METTL14SETD2−/−Hypoxia groups were subjected to 10% O2 hypoxia for four weeks to establish an animal model of PAH. (A) Pulmonary artery wall thickness (< 50 mm, 51–100 mm, > 100 mm) and pulmonary artery relative medial thickness (PAMT) were measured via HE staining. The ratio of RV/(LV + S) was calculated. (B) Western blotting was used to detect the expression of SETD2, METTL14, α-SMA, collagen I, PCNA, cyclin A1, cyclin D1, cyclin E1, H3K36me3 and H3K36. (C) IF images of OCT-embedded mouse lung sections stained with METTL14 (red) and SETD2 (green), and pulmonary arterioles were observed via immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. (D-E) Colorimetry was used to measure the m6A level of total RNA and poly A + RNA. (F) Dot blotting was used to detect the m6A level of total RNA, the methylene blue staining was used as loading control. (n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Chronic hypoxia exposure resulted in a notable increase in METTL14 expression in the pulmonary arteries of SETD2fl/flHypoxia mice. Conversely, knockout of the SETD2 gene in SMCs resulted in a reduction in pulmonary artery remodeling and a decrease in METTL14 expression (Fig. 4C). To investigate the involvement of SETD2 and METTL14-mediated m6A RNA modification in PAH, we measured total RNA m6A levels via dot blot and colorimetric methods and found that m6A expression was significantly reduced after knockout of the SETD2 gene in SMCs, which suggested that knockout of the SETD2 gene in SMCs reduce total RNA m6A in the PAH pulmonary artery through METTL14 (Fig. 4D-F). Kumari et al. [28]. also reported that SETD2 knockout downregulated global RNA m6A levels in gliomas. In addition, western blot analysis revealed that silencing the SETD2 gene in SMCs reduced the protein levels of H3K36me3 and METTL14 in SMCs (Fig. 4B). These findings indicate that SETD2 knockout in SMCs results in a reduction in the expression of H3K36me3 and METTL14, which may contribute to the alleviation of PAH.

Knockdown of the SETD2 gene in PASMC significantly reduces PAH pulmonary artery Piezo1 mRNA m6A

To explore the possible mechanism of PAH regulation by METTL14-mediated m6A, we collected pulmonary artery tissue samples for MeRIP sequencing (MeRIP-Seq) analysis and found that the knockdown of the SETD2 gene in SMCs in PAH can significantly reduce the mRNA levels of Piezo1, PNCA, VEGFR2, TGFR1, IFIT2 and U2AF1, especially Piezo1 (Supplementary Fig. 4 A-C). To verify the MeRIP-Seq results, additional qPCR analysis demonstrated that Piezo1 expression was markedly elevated in the SETD2fl/flHypoxia group compared with the SETD2fl/fl.Normoxia group. Nevertheless, knockout of the SETD2 gene in smooth muscle cells led to a notable reduction in Piezo1 mRNA m6A (Fig. 5E). Consequently, Piezo1 was identified as the primary effective downstream target. Confocal immunofluorescence images revealed that Piezo1, which was notably elevated in PAH, was predominantly expressed in PASMCs. A comparison of the SETD2fl/fl. Normoxia group with the SETD2fl/fl. Normoxia group revealed a significant increase in Piezo1 expression. Upon knockout of the SETD2 gene, a notable decrease in Piezo1 expression was observed in smooth muscle cells (Supplementary Fig. 4 D). The regulation of Piezo1 expression by SETD2 at the mRNA and protein level was subsequently examined. Real-time qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 4E) and Western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 4 F) revealed that Piezo1 expression was markedly elevated in the SETD2fl/flHypoxia group compared with the SETD2fl/flNormoxia group. However, knockout of the SETD2 gene in smooth muscle cells led to a notable reduction in Piezo1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 4 F). In conclusion, knockdown of the SETD2 gene in SMCs can significantly reduce Piezo1 mRNA m6A in PAH pulmonary arteries and ameliorate PAH.

Fig. 5.

METTL14 inhibits the attenuation of Piezo1 mRNA via m6A modification. (A-B) mRNA and protein expression levels of METTL14 and Piezo1 were detected via real-time PCR and Western blotting. (C) The SRAMP online tool was used to predict potential m6A modification sites in Piezo1 mRNA. (D) MeRIP-qPCR was used to measure the level of m6A methylation at A base 1080 of Piezo1 mRNA. (E) The stability of Piezo1 mRNA was detected via an actinomycin D inhibition assay. (F) Effect of the methylation of the A base at m6A at position 1080 of Piezo1 mRNA on mRNA stability, as verified by luciferin reporter experiments (N = 3–6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

METTL14 inhibits Piezo1 mRNA decay via m6A modification

To determine the function of Piezo1 in PAH, we infected hPASMCs with AAV-9-METTL14 and used null vectors as controls. Real-time PCR and Western blot analysis confirmed a considerable increase in Piezo1 expression in hPASMCs transfected with METTL14 overexpression (Fig. 5A, B). To further investigate this finding, we employed the sequence-based m6A modification site predictor SRAMP (http://www.cuilab.cn/sramp) to predict potential m6A modification sites in Piezo1 mRNA. This analysis revealed that the A base at position 1080 exhibited high confidence modification potential (Fig. 5C). Additionally, qPCR analysis revealed that the level of Piezo1 mRNA was markedly elevated in hPASMCs with the METTL14-overexpressing (Fig. 5D). Upon cessation of transcription with the RNA synthesis inhibitor actinomycin D, the decay rate of Piezo1 mRNA in cells overexpressing METTL14 was significantly slowed (Fig. 5E). These findings suggest that METTL14-mediated methylation influences the stability of Piezo1 mRNA. The Piezo1-WT luciferase reporter gene was subsequently constructed by fusing a portion of the coding sequence (CDS) of Piezo1 and the 1080 A base to the downstream region of the luciferase reporter gene. This result demonstrated that METTL14 markedly enhanced the luciferase activity of Piezo1. A Piezo1-Mutant-A1080C luciferase reporter gene was designed and constructed by substituting a specific adenosine in the m6A motif. The resulting reporter gene was then used to generate a reporter, which demonstrated that METTL14 was unable to promote luciferase activity in the presence of a site 1080 mutation (Fig. 5F). Collectively, these results confirm that METTL14-mediated m6A modification of Piezo1 mRNA is essential for Piezo1 mRNA stability.

METTL14 induces PAH via Piezo1

To further substantiate the involvement of Piezo1 in PAH, we conducted in vivo experiments. The right cardiac catheter results revealed that RVMP, RVSP, mPAP and TPR were significantly decreased and that RVCO was significantly increased after Piezo1 gene-specific knockdown in PASMCs (Supplementary Fig. 5 A), which suggested that Piezo1 knockdown in SMCs could effectively alleviate PAH. The results of the echocardiographic tests demonstrated that the reduction in Piezo1 in mouse PASMCs led to a notable decrease in RVEDD, RVEDV, RVESD, and RVESV, whereas RVFS, RVEF, and PAAT exhibited considerable increases (Supplementary Fig. 5B and 5 C). These findings suggest that PASMC-specific Piezo1 defects may significantly ameliorate right ventricular function in PAH.

To further evaluate the effects of Piezo1 on pulmonary artery pathological remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy, we evaluated the Fulton index histologically. Our findings demonstrated that defects in SMC-specific Piezo1 significantly reduced the RV/(LV + S) ratio (Fig. 6A). Additionally, HE staining revealed that depletion of Piezo1 expression in SMCs markedly attenuated PAMT within pulmonary arteries, thereby ameliorating the pulmonary remodeling induced by METTL14 overexpression (Fig. 6A). Meanwhile, western blot analysis revealed a notable reduction in the expression of cell proliferation markers in PASMC-specific Piezo1-deficient (Fig. 6B). These findings indicate that the knockdown of the Piezo1 gene in SMCs can inhibit PASMC proliferation and ameliorate PAH. Subsequently, the expression level of total mRNA m6A in each group was determined via colorimetry and dot blot. The results demonstrated that the total m6A level in SMCs was significantly increased in METTL14 overexpression group (Fig. 6C and E). In conclusion, these findings indicate that METTL14 regulates Piezo1 expression through m6A modification and plays an important role in the pathological remodeling of PAH and pulmonary arteries.

Fig. 6.

Piezo1 mediates METTL14 to induce PAH. First, a Piezo1 adeno-associated virus interference vector (AAV9-shPiezo1) was constructed, and both AAV9-shPiezo1 and AAV9-METTL14 were delivered to the lungs of infected C57BL/6 mice through air tubes and fed for 4 weeks under 10% oxygen to establish a PAH model, with HypoxiaNull serving as a control. The experimental groups were designated HypoxiashPiezo1, HypoxiaMETTL14, and shPiezo1HypoxiaMETTL14. (A) Pulmonary artery wall thickness (< 50 mm, 51–100 mm, > 100 mm) was measured via HE staining, and PAMT was calculated. The mass ratio of the right ventricle/(left ventricle + septum) was calculated. (B) The expression levels of Piezo1, METTL14, α-SMA, collagen I, PCNA, cyclin A1, cyclin D1, and cyclin E1 were detected via Western blotting. (C-D) mRNA m6A levels of total RNA and poly A + RNA were detected via colorimetry. (E) Dot blot analysis of the m6A levels of total RNA, the methylene blue staining was used as loading control. (n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

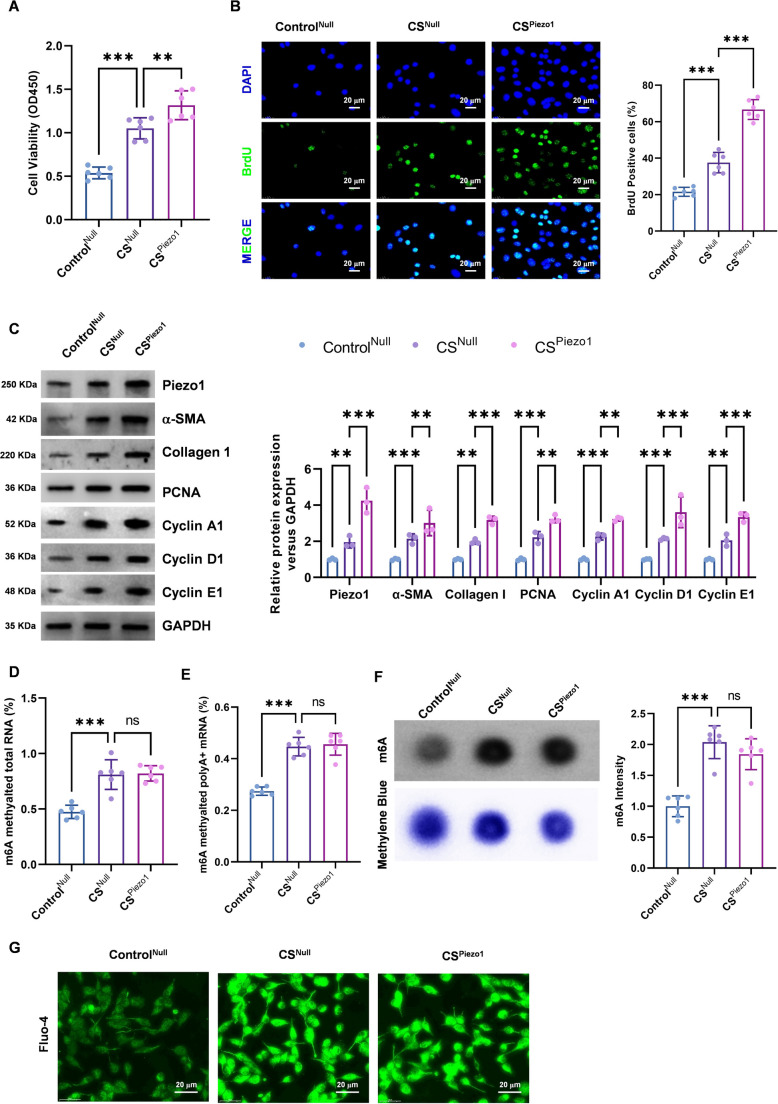

Piezo1 promotes PASMC proliferation by increasing Ca2+ levels

To gain further analytical insight into the mechanism by which Piezo1 facilitates PASMC proliferation, we constructed a Piezo1-adeno-associated virus expression vector (AAV9-Piezo1), infected hPASMCs with this vector. Compared with those in the ControlNull group, the activity and proliferative capacity of PASMCs in the PAH group were markedly elevated, particularly in the CSPiezo1 group (Fig. 7A, B). Western blot analysis revealed notable increases in the expression levels of cell proliferation markers in the PAH group compared with those in the control group. This increase was particularly pronounced in the CSPiezo1 group (Fig. 7C). These findings suggest that Piezo1 overexpression markedly enhances the proliferation of PASMCs. The mRNA m6A levels of total RNA and poly A + RNA were detected via colorimetry. The results demonstrated a notable increase in m6A expression levels in the PAH group relative to those in the control group (Fig. 7D, E). The dot blot also revealed the same result (Fig. 7F). These findings suggest that m6A modification promotes PASMC proliferation by regulating Piezo1. Piezo1 is a principal component of stretch-activated ion channels (SACs), enabling the detection of external stressors and promoting the influx of intracellular Ca²⁺ [29]. We subsequently investigated the intracellular Ca²⁺ levels, and Fluo-4 fluorescence revealed a notable increase in the intracellular Ca²⁺ levels in the PAH group compared with those in the control group (Fig. 7G). These data collectively indicate that m6A modification-mediated Piezo1 may facilitate PASMC proliferation by increasing Ca²⁺ influx.

Fig. 7.

Piezo1 promotes the proliferation of PASMCs. AAV9-Piezo1 was used to infect hPASMCs, and an in vitro model of PAH was established by CS. ControlNull was utilized as the control group, while CSNull and CSPiezo1 were employed as the experimental groups. (A) CCK-8 detection of cell activity. (B) Cell proliferation was detected by BrdU staining. (C) Protein expression levels of Piezo1, α-SMA, collagen I, PCNA, cyclin A1, cyclin D1, and cyclin E1 were measured via Western blotting. (D-E) Colorimetry was used to detect the mRNA m6A level of total RNA and poly A + RNA. (F) A dot blot assay was used to detect the m6A level of total RNA. (G) Intracellular calcium levels were measured by Fluo-4; scale bar = 25 μm (N = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

SETD2 upregulates Piezo1 via METTL14 and promotes Ca2+ influx to induce PAH

In vivo experiments found that the overexpression of Piezo1 in PASMCs exacerbated PAH and reversed the effects of SMCs-specific SETD2 defects (Supplementary Fig. 6 A). The results of the echocardiographic analysis revealed that the overexpression of SMC-specific Piezo1 induced significant increases in RVEDD, RVEDV, RVESD, and RVESV, accompanied by reductions in RVEF, RVFS, and PAAT, compared with those in the control group (Supplementary Fig. 6B and 6 C). These data suggested that the overexpression of Piezo1, which is specific to SMCs, effectively reversed the impact of SETD2 knockout and significantly exacerbated the degree of right ventricular dysfunction.

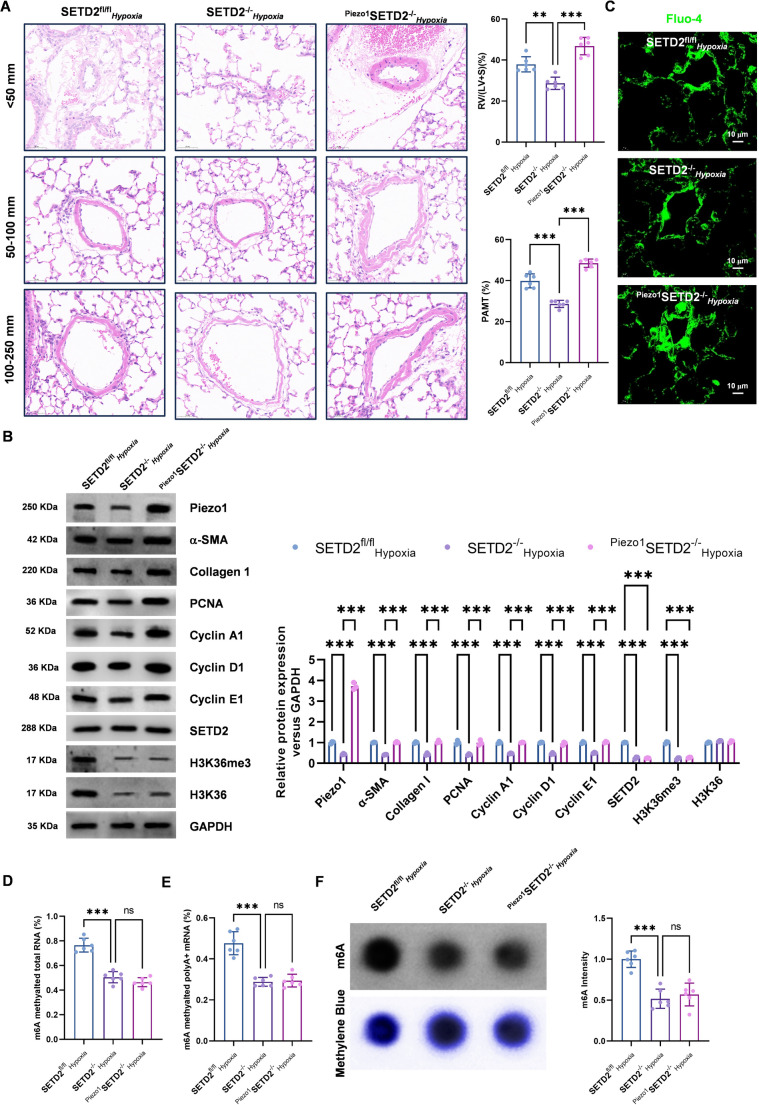

To further assess the impact of Piezo1 overexpression in SMCs on pulmonary artery pathological remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy, we evaluated cardiac function via the Fulton index. As shown in Fig. 9C, Piezo1 overexpression in SMCs markedly elevated the LV/(LV + S) ratio. The subsequent histological analysis examined the impact of Piezo1 overexpression in SMCs on pulmonary arteries. The pulmonary arteries of mice with specific Piezo1-overexpressing SMCs exhibited notable thickening, accompanied by a significant increase in PAMT (Fig. 8A). Western blotting also revealed that Piezo1 overexpression in SMCs resulted in a significant increase in the expression of cell proliferation markers (Fig. 8B). These findings suggest that the overexpression of Piezo1 may reverse the effect of SETD2 knockdown and promote pulmonary artery remodeling. In addition, Fluo-4 fluorescence revealed a notable increase in Ca²⁺ levels in the PASMCs of Piezo1-overexpressing mice (Fig. 8C). These findings indicate that Piezo1 overexpression in smooth muscle cells facilitates Ca²⁺ influx and exacerbates pathological remodeling of pulmonary arteries.

Fig. 9.

A schematic model shows a novel SETD2/H3K36me3/METTL14/m6A axis that stabilizes Piezo1 mRNA, promoting Ca²⁺-dependent TGM2 activation and PASMC proliferation in PAH

Fig. 8.

SETD2 upregulates Piezo1 via METTL14 to induce PAH. AAV9-Piezo1 was delivered to SETD2−/−C57BL/6 mice via tracheal administration and fed for 4 weeks under hypoxic conditions (10% O₂) to establish a PAH model. The control group was set to SETD2fl/flHypoxia, while the experimental groups were designated SETD2−/−Hypoxia and Piezo1SETD2−/−Hypoxia. (A) Pulmonary artery wall thickness (< 50 mm, 51–100 mm, > 100 mm) was measured via HE staining, and the PAMT was calculated. The right ventricle/(left ventricle + ventricular septum) mass ratio was calculated to evaluate cardiac function. (B) The expression levels of Piezo1, α-SMA, collagen I, PCNA, cyclin A1, cyclin D1, cyclin E1, SETD2, H3K36me3 and H3K36 were detected via Western blotting. (C) Intracellular calcium levels were measured by Fluo-4; scale bar = 25 μm. (D-E) The mRNA m6A levels of total RNA and poly A + RNA were detected via colorimetry. (F) Blot analysis of m6A levels in total RNA, the methylene blue staining was used as loading control. (n = 6; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

The expression of Piezo1, SETD2, and H3K36me3 at the protein level was subsequently evaluated. Western blotting revealed that knockout of the SETD2 gene in SMCs led to notable reductions in both Piezo1 and H3K36me3 levels (Fig. 8B). These findings suggest that SETD2 may regulate Piezo1 expression via H3K36me3. Next, the RNA m6A levels in each group were analyzed via dot blotting and colorimetry. The results demonstrated a significant decrease in the total m6A level in the pulmonary artery following knockout of the SMCs SETD2 gene (Fig. 8D and F). These findings suggest that knockout of the SETD2 gene in SMCs regulates Piezo1 expression by reducing m6A via METTL14. Taken together, these results suggest that SETD2 mediates H3K36me3-mediated regulation of METTL14 m6A modification, which in turn mediates Piezo1 regulation of PAH progression.

Piezo1 enhances TGM2 expression and promotes PASMC proliferation

Previous studies have shown that Piezo1 promotes small artery remodeling in hypertensive patients by increasing the intracellular Ca2+ concentration and activating transglutaminase 2 (TGM2) in smooth muscle cells [18, 30]. To test the hypothesis that Ca²⁺ influx promotes the proliferation of PASMCs via TGM2, we constructed an adenovirus expressing Piezo1 (Ad-Piezo1) to infect hPASMCs and established a PAH model in vitro. Western blot analysis revealed a notable increase in TGM2 protein expression in the PAH group, particularly in the CSPiezo1 group (Supplementary Fig. 7 A). Fluorescence staining demonstrated that TGM2 was predominantly localized to the cytoplasm of PASMCs (Supplementary Fig. 7B). In addition, TGM2 enzyme activity in PASMCs transfected with Piezo1 was significantly increased (Supplementary Fig. 7 C). These findings indicate that Piezo1 overexpression facilitates PASMCs proliferation by stimulating TGM2 activity.

In vivo experiments were subsequently conducted for further verification. TGM2 expression and enzyme activity were markedly lower in the SETD2−/−Hypoxia group than in the control group. Notably, following Piezo1 transfection, TGM2 protein expression in PASMCs was markedly elevated, accompanied by a notable increase in TGM2 enzyme activity (Supplementary Fig. 7D-7 F). Furthermore, Piezo1-specific inhibitors (e.g., GsMTx4) abolished the effect of Piezo1 on the elevated TGM2 protein expression and activity. (Supplementary Fig. 7D-7 F).These findings indicate that SETD2 knockout in SMCs can suppress TGM2 expression, whereas Piezo1 overexpression can stimulate TGM2 expression by increasing intracellular Ca²⁺ levels, thereby contributing to the development of PAH.

Discussion

With continuous research on RNA modification, more than 170 chemical modifications have been found in RNA, among which N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA methylation is one of the most abundant mRNA modifications in eukaryotes [5, 31]. m6A is a methylation modification of mRNA stop codon, 5’-UTR and adenylate 6th N in the long exon region, which can regulate RNA degradation, shear, transport, localization and translation, and play multiple regulatory effects in tissue development, tumorigenesis, stem cell differentiation and circadian rhythm transformation [32, 33]. The m6A methyltransferase complex (MTC) is composed of METTL3, METTL14 and WTAP, where METTL3 and METTL14 can play a synergistic role in catalyzing the formation of m6A only after they are recruited to the nuclear speckle by WTAP [34]. METTL14 is critical in numerous biological processes. The results of in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that METT14 over-expression in SMCs elevated the level of m6A in PASMCs, stimulated the proliferation of PASMCs, exacerbated hypoxia-induced PAH and right ventricular dysfunction.

Histone lysine methylation (HKM) is the process by which S-adenosylmethionine methyl is transferred to lysine residues in the direction of lysine methyltransferase to form methylated derivatives [35]. H3K36me3 is an epigenetic mark associated with actively transcribed genes and is critical for several cellular processes including transcription elongation, DNA repair, and DNA methylation [36]. There is a correlation between HKM and m6A, with H3K36me3 directing the deposition of m6A by recruiting METTL14, and methylation of H3K36 recruiting the METTL3-METTL14 N6-adenosine methylation complex for m6A modification of newborn transcripts in the active chromatin region [36, 37]. HKM is crucial in regulating PASMC proliferation, migration and contraction through epigenetic mechanisms.

SET domain containing 2 (SETD2) is a key histone lysine methyltransferase consisting of AWS-SET-PostSET, WW and SRI domains that catalytically generates H3K36me3 with H3K36me2 as substrate. It exerts potent tumor inhibitory effects by regulating RNA cleavage, DNA methylation, chromosome segregation and DNA damage repair [36, 38]. Studies have shown that 69.2% of m6A peaks overlap with H3K36me3 modification sites in the mRNA stop codon region. The co-transcriptional catalytic activity of SETD2 is required to restore the levels of H3K36me3 and m6A, and deletion of SETD2 results in hypomethylation of H3K36me3 and m6A [9]. The absence of SETD2 may lead to oocyte maturation defects and single cell arrest after fertilization, resulting in embryonic abortion [39]. We found that HKM plays an important regulatory role in PAH, and SMCS-specific SETD2 deletion inhibits mRNA m6A methylation by down regulating METTL14 levels through H3K36me3, reverses hypoxia-induced pulmonary artery remodeling, significantly alleviates PAH, and improves right ventricular dysfunction caused by PAH. This suggests that SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 and METTL14-mediated m6A play important roles in the pathogenesis of PAH.

Shear stress is an important mechanical factor in vascular constriction and remodeling [40]. Piezo1 was discovered to be a mechanosensitive, non-selective cation ion channel protein that senses and transmits a variety of mechanological forces, such as cell membrane tension, cellular stretch, shear stress, and cyclic pressure [18]. It plays an important role in the early development of blood vessels, and has been demonstrated to promote the formation of new blood vessels by activating the MT1-MMP signaling pathway [41]. Recently, Piezo1 was found to promote pulmonary vascular hyperpermeability after mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [42]. Furthermore, Piezo1 has been shown to exert a positive regulatory effect in PAH by modulating cellular behaviour through shear stress and piezoelectric sensing, thereby promoting cell proliferation, migration and aggregation, which in turn leads to pathological vascular remodeling [43, 44].

An elevation in the concentration of free Ca²⁺ within the cytoplasm of PASMCs is the primary mechanism underlying pulmonary vascular constriction. Concurrently, a disturbance in cellular Ca²⁺ balance stimulates the proliferation of PASMCs, resulting in pulmonary artery remodelling and the advancement of PAH [45]. Piezo1, a core member of the stretch-activated ion channels (SACs), is capable of sensing external pressure and promoting the osmotic influx of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ plasma, with a particular ability to facilitate Ca2+ influx [17, 46]. In physiologic states, pulmonary endothelial cell Piezo1 regulates pulmonary vasodilation via mediation of inward Ca²⁺ flow [47]. Fernandeds et al. [48] demonstrated that Piezo1-mediated Ca²⁺ influx promotes contraction and abnormal proliferation of PASMCs. Furthermore, Yoda1-mediated Ca²⁺ flow through the Piezo1 channel stimulates PASMCs proliferation [49]. In this study, we found that SETD2 and METTL14 affect the development of PAH by regulating the expression of Piezo1. The use of MeRIP-qPCR, RNA stability analysis and dual luciferase reporter assay revealed that METTL14 enhanced Piezo1 expression in an m6A-dependent manner. In comparison to the control group, METTL14 overexpression resulted in the upregulation of Piezo1 in PASMCs, increased Ca²⁺ influx, induced PASMCs excessive proliferation and pulmonary artery remodelling, and accelerated PAH progression and right ventricular dysfunction. Knockout of the SETD2 gene in SMCs can significantly reduce Piezo1 mRNA m6A in PAH pulmonary arteries and improve PAH.

Previous studies have shown that Piezo1 activation induces Ca2+ influx and activates transglutaminase2 (TGM2), leading to lens sclerosis [50]. Retailleau et al. [30] showed that Piezo1 activates TGM2 to induce arteriolar angiogenesis in arterial smooth muscle cells. Our study revealed that Piezo1 and TGM2 are predominantly expressed in PASMCs, and that Piezo1 exerts a crucial regulatory role in PAH by enhancing Ca²⁺ influx, activating TGM2, and promoting PASMCs proliferation. In addition, Mertens et al. [51] found that ADORA2B on PASMC promotes PAH by inducing the expression of IL-6, hyaluronic acid and TGM2. Taken together, these findings indicate that TGM2 plays a critical role in the development of PAH.

Our study indicated that SETD2 gene knockout in SMCs could reduce m6A levels of H3K36me3, METTL14, and Piezo1 mRNA. This results in the down-regulation of TGM2, which reverses the malignant remodeling of pulmonary arteriolar arteries and alleviates PAH, thereby improving right heart function. Nevertheless, when the SETD2 gene is overexpressed in smooth muscle cells, the opposite effect is observed. In short, by combining epigenetic modification and shear stress for the first time, we found that SETD2 drives METTL14-mediated m6A to inhibit Piezo1 attenuation and activate TGM2 to induce PAH, providing new insights and potential avenues for prevention and treatment of PAH.

While our study provides novel insights into the SETD2/METTL14-Piezo1-TGM2 axis in PAH, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the hypoxia-induced PAH model, though widely utilized, may not fully recapitulate the heterogeneity of human PAH, which includes heritable, idiopathic, and inflammation-associated subtypes. Validation in alternative preclinical models and human PAH tissues is critical to confirm translational relevance. Second, while we identified METTL14-mediated m6A regulation of Piezo1 mRNA stability, the specific m6A sites on Piezo1 and the reader proteins (e.g., YTHDF1/2) responsible for its decay remain uncharacterized. Third, our focus on PASMCs excludes potential contributions from endothelial cells or fibroblasts, which are central to PAH pathogenesis. Finally, while AAV9 enabled PASMC-focused METTL14 modulation in this study, emerging serotypes (e.g., AAV6.2FF) with enhanced lung SMC specificity may further improve targeting precision in future investigations. Addressing these gaps will refine therapeutic targeting of this axis in diverse PAH subtypes.

Conclusions

The present study revealed that SETD2 recruits METTL14 to mRNA m6A via METTL14 methylation, thereby activating Piezo1, increasing intracellular Ca²⁺ levels and enhancing TGM2 expression (Fig. 9). This study revealed that SETD2-mediated H3K36me3 drives METTL14-mediated m6A modification, inhibits Piezo1 mRNA attenuation, activates TGM2 to induce PAH, and provides a new intervention target for the treatment of PAH.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 2.08 MB)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants of this work.

Authors’ contributions

The experiment was conducted by SZ, who also wrote the manuscript; CY helped conduct most of the experiments; JL assisted in modifying the manuscript; the work was designed, supervised, and funded by QW and XZ; and the submitted version was approved by all the authors.

Funding

Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China supported this work (No. 82360060, 81970199 and 82160082), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (No. 20232ACB206003 and 20243BCE51022) and the Jiangxi Joint Talent Support Program—the main project for cultivating academic and technical leader-leading talent.

Data Availability

Data and materials are available from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the animal experiments adhered to the NIH guidelines. The Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanchang University approved the protocols (Approval No. CDYFYIACUC-202412QR005).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shuai-shuai Zhao and Chuan Yuan contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Qi-cai Wu, Email: ndyfy00619@ncu.edu.cn.

Xue-liang Zhou, Email: zhouxliang@ncu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Tuder RM, Gandjeva A, Williams S, Kumar S, Kheyfets VO, Hatton-Jones KM, Starr JR, Yun J, Hong J, West NP, Stenmark KR (2024) Digital Spatial profiling identifies distinct molecular signatures of vascular lesions in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 210(3):329–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Southgate L, Machado RD, Graf S, Morrell NW (2020) Molecular genetic framework underlying pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol 17(2):85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omura J, Satoh K, Kikuchi N, Satoh T, Kurosawa R, Nogi M, Ohtsuki T, Al-Mamun ME, Siddique MAH, Yaoita N, Sunamura S, Miyata S, Hoshikawa Y, Okada Y, Shimokawa H (2019) ADAMTS8 promotes the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension and right ventricular failure: A possible novel therapeutic target. Circ Res 125(10):884–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghofrani HA, Gomberg-Maitland M, Zhao L, Grimminger F (2025) Mechanisms and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol 22(2):105–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Yang D, Liu T, Chen J, Yu J, Yi P (2023) N6-methyladenosine-mediated gene regulation and therapeutic implications. Trends Mol Med 29(6):454–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Liu S, Zhang Y, Gao Q, Sun W, Fu L, Cao J (2018) Histone demethylase JARID1B regulates proliferation and migration of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells in mice with chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension via nuclear factor-kappa B (NFkB). Cardiovasc Pathol 37:8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Q, Lu Z, Singh D, Raj JU (2012) BIX-01294 treatment blocks cell proliferation, migration and contractility in ovine foetal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Cell Prolif 45(4):335–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu M, Sun XJ, Zhang YL, Kuang Y, Hu CQ, Wu WL, Shen SH, Du TT, Li H, He F, Xiao HS, Wang ZG, Liu TX, Lu H, Huang QH, Chen SJ, Chen Z (2010) Histone H3 lysine 36 methyltransferase Hypb/Setd2 is required for embryonic vascular remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(7):2956–2961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang H, Weng H, Zhou K, Wu T, Zhao BS, Sun M, Chen Z, Deng X, Xiao G, Auer F, Klemm L, Wu H, Zuo Z, Qin X, Dong Y, Zhou Y, Qin H, Tao S, Du J, Liu J, Lu Z, Yin H, Mesquita A, Yuan CL, Hu YC, Sun W, Su R, Dong L, Shen C, Li C, Qing Y, Jiang X, Wu X, Sun M, Guan JL, Qu L, Wei M, Muschen M, Huang G, He C, Yang J, Chen J (2019) Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 36 guides m(6)A RNA modification co-transcriptionally. Nature 567(7748):414–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai X, Cheng Y, Luo W, Wang J, Wang C, Zhang X, Zhang W, Chao J (2025) m6A ribonucleic acid methylation in fibrotic diseases of visceral organs. Small Sci 5(2):2400308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He C, Ji Y, Zhang Y, Ou J, Wu D, Qin H, Hua J, Li Q, Zheng H (2025) Inhibition of Mettl3 by STM2457 and loss of macrophage Mettl3 alleviate pulmonary hypertension and right heart remodeling. Lung 203(1):34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Z, Sang M, Li Q, Zhang H, Luo Z, Zhang Y, Li H, Ma Y, Cheng Y, Zhuang D, Ju W, Guo Q (2025) Targeted FTO knockout in endothelial cells boosts adhesion and lowers inflammatory infiltration to alleviate pulmonary arterial hypertension. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 749:151339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu N, Shen Y, He Y, Li C, Xiong W, Hu Y, Qiu Z, Peng F, Han W, Li C, Long X, Zhao R, Zhao Y, Shi B (2024) Loss of m6A demethylase ALKBH5 alleviates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension via inhibiting Cyp1a1 mRNA decay. J Mol Cell Cardiol 194:16–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X-L, Huang F-J, Li Y, Huang H, Wu Q-C (2021) SEDT2/METTL14-mediated m6A methylation awakening contributes to hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice. Aging 13(5):7538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Su SA, Li W, Ma Y, Shen J, Wang Y, Shen Y, Chen J, Ji Y, Xie Y, Ma H, Xiang M (2021) Piezo1-Mediated mechanotransduction promotes cardiac hypertrophy by impairing calcium homeostasis to activate calpain/calcineurin signaling. Hypertension 78(3):647–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonnet S, Provencher S (2016) Shear stress maladaptation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. An ageless concept. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 193(12):1331–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin YC, Guo YR, Miyagi A, Levring J, MacKinnon R, Scheuring S (2019) Force-induced conformational changes in PIEZO1. Nature 573(7773):230–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Q, Zhou H, Chi S, Wang Y, Wang J, Geng J, Wu K, Liu W, Zhang T, Dong MQ, Wang J, Li X, Xiao B (2018) Structure and mechanogating mechanism of the Piezo1 channel. Nature 554(7693):487–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan K, Shamskhou EA, Orcholski ME, Nathan A, Reddy S, Honda H, Mani V, Zeng Y, Ozen MO, Wang L, Demirci U, Tian W, Nicolls MR, de Jesus Perez VA (2019) Loss of Endothelium-Derived Wnt5a is associated with reduced pericyte recruitment and small vessel loss in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 139(14):1710–1724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Lieshout LP, Domm JM, Wootton SK (2019) AAV-Mediated Gene Delivery to the Lung. Methods Mol Biol 1950:361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villegas-Esguevillas M, Cho S, Vera-Zambrano A, Kwon JW, Barreira B, Telli G, Navarro-Dorado J, Morales-Cano D, de Olaiz B, Moreno L, Greenwood I, Perez-Vizcaino F, Kim SJ, Climent B, Cogolludo A (2023) The novel K(V)7 channel activator URO-K10 exerts enhanced pulmonary vascular effects independent of the KCNE4 regulatory subunit. Biomed Pharmacother 164:114952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Liu ZH, Chen JW, Shu XY, Shen Y, Ding FH, Zhang RY, Shen WF, Lu L, Wang XQ (2019) Using En face Immunofluorescence staining to observe vascular endothelial cells directly. J Vis Exp 20(150):e59325 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Wedgwood S, Lakshminrusimha S, Schumacker PT, Steinhorn RH (2015) Cyclic stretch stimulates mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and Nox4 signaling in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 309(2):L196–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi H, Zhang X, Weng YL, Lu Z, Liu Y, Lu Z, Li J, Hao P, Zhang Y, Zhang F, Wu Y, Delgado JY, Su Y, Patel MJ, Cao X, Shen B, Huang X, Ming GL, Zhuang X, Song H, He C, Zhou T (2018) m(6)A facilitates hippocampus-dependent learning and memory through YTHDF1. Nature 563(7730):249–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathiyalagan P, Adamiak M, Mayourian J, Sassi Y, Liang Y, Agarwal N, Jha D, Zhang S, Kohlbrenner E, Chepurko E, Chen J, Trivieri MG, Singh R, Bouchareb R, Fish K, Ishikawa K, Lebeche D, Hajjar RJ, Sahoo S (2019) FTO-Dependent N(6)-Methyladenosine regulates cardiac function during remodeling and repair. Circulation 139(4):518–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR (2012) Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149(7):1635–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bravo-Hernandez M, Tadokoro T, Navarro MR, Platoshyn O, Kobayashi Y, Marsala S, Miyanohara A, Juhas S, Juhasova J, Skalnikova H, Tomori Z, Vanicky I, Studenovska H, Proks V, Chen P, Govea-Perez N, Ditsworth D, Ciacci JD, Gao S, Zhu W, Ahrens ET, Driscoll SP, Glenn TD, McAlonis-Downes M, Da Cruz S, Pfaff SL, Kaspar BK, Cleveland DW, Marsala M (2020) Spinal subpial delivery of AAV9 enables widespread gene Silencing and blocks motoneuron degeneration in ALS. Nat Med 26(1):118–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumari S, Singh M, Kumar S, Muthuswamy S (2023) SETD2 controls m6A modification of transcriptome and regulates the molecular oncogenesis of glioma. Med Oncol 40(9):249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang HJ, Wang Y, Mirjavadi SS, Andersen T, Moldovan L, Vatankhah P, Russell B, Jin J, Zhou Z, Li Q, Cox CD, Su QP, Ju LA (2024) Microscale geometrical modulation of PIEZO1 mediated mechanosensing through cytoskeletal redistribution. Nat Commun 15(1):5521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Retailleau K, Duprat F, Arhatte M, Ranade SS, Peyronnet R, Martins JR, Jodar M, Moro C, Offermanns S, Feng Y, Demolombe S, Patel A, Honore E (2015) Piezo1 in smooth muscle cells is involved in Hypertension-Dependent arterial remodeling. Cell Rep 13(6):1161–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J, Dou X, Chen C, Chen C, Liu C, Xu MM, Zhao S, Shen B, Gao Y, Han D, He C (2020) N (6)-methyladenosine of chromosome-associated regulatory RNA regulates chromatin state and transcription. Science 367(6477):580–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livneh I, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, Dominissini D (2020) The m(6)A epitranscriptome: transcriptome plasticity in brain development and function. Nat Rev Neurosci 21(1):36–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frye M, Harada BT, Behm M, He C (2018) RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science 361(6409):1346–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaccara S, Ries RJ, Jaffrey SR (2019) Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20(10):608–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhat KP, Umit Kaniskan H, Jin J, Gozani O (2021) Epigenetics and beyond: targeting writers of protein lysine methylation to treat disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20(4):265–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yin J, Qi TF, Li L, Wang Y (2023) Targeted profiling of epitranscriptomic reader, writer, and eraser proteins regulated by H3K36me3. Anal Chem 95(25):9672–9679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulias K, Greer EL (2023) Biological roles of adenine methylation in RNA. Nat Rev Genet 24(3):143–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fahey CC, Davis IJ (2017) SETting the stage for Cancer development: SETD2 and the consequences of lost methylation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7(5):a026468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Xu Q, Xiang Y, Wang Q, Wang L, Brind’Amour J, Bogutz AB, Zhang Y, Zhang B, Yu G, Xia W, Du Z, Huang C, Ma J, Zheng H, Li Y, Liu C, Walker CL, Jonasch E, Lefebvre L, Wu M, Lorincz MC, Li W, Li L, Xie W (2019) SETD2 regulates the maternal epigenome, genomic imprinting and embryonic development. Nat Genet 51(5):844–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Q, Li X, Xing Y, Chen Y (2023) Piezo1, a novel therapeutic target to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension. Front Physiol 14:1084921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang H, Hong Z, Zhong M, Klomp J, Bayless KJ, Mehta D, Karginov AV, Hu G, Malik AB (2019) Piezo1 mediates angiogenesis through activation of MT1-MMP signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 316(1):C92–C103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang L, Zhang Y, Lu D, Huang T, Yan K, Yang W, Gao J (2021) Mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel activation promotes ventilator-induced lung injury via disruption of endothelial junctions in ARDS rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 556:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu H, He Y, Hong T, Bi C, Li J, Xia M (2022) Piezo1 in vascular remodeling of atherosclerosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension: A potential therapeutic target. Front Cardiovasc Med 9:1021540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lhomme A, Gilbert G, Pele T, Deweirdt J, Henrion D, Baudrimont I, Campagnac M, Marthan R, Guibert C, Ducret T, Savineau JP, Quignard JF (2019) Stretch-activated Piezo1 channel in endothelial cells relaxes mouse intrapulmonary arteries. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 60(6):650–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liao J, Lu W, Chen Y, Duan X, Zhang C, Luo X, Lin Z, Chen J, Liu S, Yan H, Chen Y, Feng H, Zhou D, Chen X, Zhang Z, Yang Q, Liu X, Tang H, Li J, Makino A, Yuan JX, Zhong N, Yang K, Wang J (2021) Upregulation of Piezo1 (Piezo type mechanosensitive ion channel component 1) enhances the intracellular free calcium in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells from idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension patients. Hypertension 77(6):1974–1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ge J, Li W, Zhao Q, Li N, Chen M, Zhi P, Li R, Gao N, Xiao B, Yang M (2015) Architecture of the mammalian mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel. Nature 527(7576):64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z, Chen J, Babicheva A, Jain PP, Rodriguez M, Ayon RJ, Ravellette KS, Wu L, Balistrieri F, Tang H, Wu X, Zhao T, Black SM, Desai AA, Garcia JGN, Sun X, Shyy JY, Valdez-Jasso D, Thistlethwaite PA, Makino A, Wang J, Yuan JX (2021) Endothelial upregulation of mechanosensitive channel Piezo1 in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 321(6):C1010–C1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernandez RA, Wan J, Song S, Smith KA, Gu Y, Tauseef M, Tang H, Makino A, Mehta D, Yuan JX (2015) Upregulated expression of STIM2, TRPC6, and Orai2 contributes to the transition of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells from a contractile to proliferative phenotype. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 308(8):C581–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J, Rodriguez M, Miao J, Liao J, Jain PP, Zhao M, Zhao T, Babicheva A, Wang Z, Parmisano S, Powers R, Matti M, Paquin C, Soroureddin Z, Shyy JY, Thistlethwaite PA, Makino A, Wang J, Yuan JX (2022) Mechanosensitive channel Piezo1 is required for pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 322(5):L737–L760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doki Y, Nakazawa Y, Sukegawa M, Petrova RS, Ishida Y, Endo S, Nagai N, Yamamoto N, Funakoshi-Tago M, Donaldson PJ (2023) Piezo1 channel causes lens sclerosis via transglutaminase 2 activation. Exp Eye Res 237:109719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mertens TCJ, Hanmandlu A, Tu L, Phan C, Collum SD, Chen NY, Weng T, Davies J, Liu C, Eltzschig HK, Jyothula SSK, Rajagopal K, Xia Y, Guha A, Bruckner BA, Blackburn MR, Guignabert C, Karmouty-Quintana H (2018) Switching-Off Adora2b in vascular smooth muscle cells halts the development of pulmonary hypertension. Front Physiol 9:555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data