Abstract

Diabetic bone defects are associated with chronic inflammation, impaired healing, and high susceptibility to infection, posing serious clinical challenges. Recent studies have identified macrophage metabolic dysfunction as a key contributor to this impaired regenerative process. Targeting macrophage metabolism offers a promising strategy to rebalance the inflammatory microenvironment and promote bone repair. Metformin, a well-established antidiabetic agent, has been shown to reprogram macrophage metabolism by enhancing oxidative phosphorylation and promoting anti-inflammatory M2 polarization. However, its therapeutic efficacy is limited by poor local retention and lack of antibacterial activity. To overcome these limitations, we developed a multifunctional self-assembled hydrogel (M − C Gel@Met) based on multivalent PEG-antimicrobial polymers and clay nanosheets, enabling sustained co-delivery of metformin and antimicrobial peptides. This hydrogel not only mimics the dynamic structure of the extracellular matrix and adapts to irregular defects, but also provides potent antibacterial protection while reprogramming macrophage metabolism. In diabetic bone defect models, M − C Gel@Met effectively alleviated inflammation, enhanced osteogenesis, and accelerated bone regeneration. Overall, this strategy presents a biomaterial-based immunometabolic strategy integrating infection control and metabolic modulation for diabetic bone repair.

Keywords: Macrophage, Metabolic reprogramming, Bone defect, Hydrogel, Metformin

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Disturbances in glucose metabolism in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) affect bone metabolism and its microenvironment, thereby significantly impairing bone regeneration [1]. Repair of bone defects in patients with DM has become a major challenge. Although autologous and allograft bone grafts are common therapeutic approaches, they have not achieved the desired therapeutic outcomes, especially when targeting the complex pathological microenvironment of diabetic patients at the site of the lesion [2]. Therefore, it remains a clinical challenge to promote healing of bone defects under DM more safely and efficiently.

Repair of bone defects is dependent on the synergistic action of osteoblast-mediated bone formation and osteoclast-mediated bone resorption [3,4]. Currently, engineering strategies based on aspects such as osteogenesis promotion or osteoclastic inhibition have been widely developed for bone defect repair [5,6]. However, in the diabetic microenvironment, sustained hyperglycemia induces alterations in the metabolic state of macrophages, leading to their increased polarization toward a pro-inflammatory state and the release of inflammatory cytokines [7]. Under this circumstance, stem cell activity is impaired, osteogenic differentiation is significantly deficient, and osteoclasts are overactivated. The imbalanced osteoblastic-osteoclastic coupling state is tilted toward bone resorption, which ultimately and inevitably leads to an exacerbation of the bone defects and impaired healing of the bone tissues in the diabetic state [8]. Therefore, designing new strategies with integrated modulation of the immune microenvironment and osteoblastic coupling is important to promote bone defect repair under DM.

Metformin is widely used in the treatment of insulin resistance–related conditions, including type II diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. As a hypoglycemic agent, it lowers blood glucose through multiple synergistic mechanisms, such as inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis, reducing hepatic glucose output, enhancing glycogen synthesis in muscle and adipose tissues, decreasing circulating free fatty acids, improving insulin sensitivity, and promoting glucose uptake and utilization [[9], [10], [11]]. Importantly, recent studies have provided deeper insights into the mechanisms of metformin, revealing its strong capacity to regulate cellular energy metabolism across various tissues—particularly the liver and skeletal muscle—primarily by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I and altering the intracellular AMP/ATP ratio [11]. This energy shift activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a key metabolic sensor that orchestrates glucose uptake, lipid oxidation, and mitochondrial homeostasis [12]. Beyond its classical metabolic effects, metformin has also been shown to exert immunometabolic regulatory functions, especially in macrophages. Metformin can reprogram macrophage metabolism by enhancing oxidative phosphorylation, thereby promoting M2 polarization—a phenotype associated with anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative activities [13]. This metabolic and phenotypic shift facilitates the resolution of chronic inflammation and supports tissue regeneration, including in bone fracture [14]. Given the therapeutic potential of metformin, enhancing its local delivery may offer distinct advantages by modulating the inflammatory microenvironment, initiating osteogenic processes, and ultimately promoting bone regeneration. However, achieving optimal efficacy requires strategies that enable controlled and sustained local release of metformin. More importantly, considering the high susceptibility of diabetic bone defects to bacterial infection—which severely compromises tissue repair—a key design priority is to develop delivery systems that not only ensure prolonged metformin release but also incorporate potent antibacterial functionality, thereby effectively reshaping the pathological microenvironment and facilitating efficient bone healing under diabetic conditions.

Hydrogel is a class of soft biomaterials with a three-dimensional (3D) cross-linked network structure, in which water serves as the dispersion medium [15,16]. Due to their high water content, softness, porosity, and tissue-like mechanical properties, hydrogels exhibit excellent biocompatibility and tunable physicochemical characteristics, making them highly suitable for biomedical applications such as drug delivery, wound healing, and tissue engineering [17]. In particular, hydrogels can mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM) by providing a hydrated and viscoelastic microenvironment that supports cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration. To enhance their mechanical performance and functionality, the incorporation of nanomaterials—such as clay nanosheets (CNSs)—has been widely explored [18,19]. These nanoscale fillers reinforce the hydrogel matrix through physical crosslinking, resulting in materials with improved structural integrity, shear-thinning behavior, and injectability.

Based on this, we designed and synthesized injectable multivalent support hydrogel encapsulating metformin, which was able to locally fill in bone defects, simulate the ECM and achieve controlled slow drug release of antimicrobial peptide and metformin. Compared with traditional hydrogels, multivalent hydrogel can adapt well to irregular defective cavities, maintain the structural integrity of the biological microenvironment, and controlled degradation and release of antimicrobial peptide and metformin. Through the regulation of cellular metabolism, it can achieve the transition of macrophage polarization state to anti-inflammatory repair phenotype, exerting osteogenic/osteoclastic effects, and ultimately promoting the bone tissue repair in the DM microenvironment (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Designed and synthesized a self-assembled multivalent hydrogel (M-C Gel@Met) for treating diabetic bone defects. The hydrogel, composed of antimicrobial polymers (PEG-(RW)3), metformin (Met), and clay nanosheets (CNSs), exhibits antimicrobial, immune-inflammatory microenvironment-regulating, and bone-forming properties, providing a promising approach for diabetic bone defect treatment with self-healing and injectable capabilities.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of PEG-(RW)3

The PEG-(RW)3 was synthesized via a thiol-ene Michael Addition. The 8-arm polyethylene glycol maleimide (8-arm PEG-Mal) (0.0125 mmol) and the RWRWRWC ((RW)3C-NH2) (0.1 mmol, 114.8 mg) were added to 10 mL of the PBS solution (pH = 8.0). The mixture was purified with argon gas for 20 min. Then, the reaction was stirred for 24 h at 25 °C in sealed state. The mixture was dialyzed (10,000 Da) for 5 days and lyophilized for 2 days to obtain products.

2.2. Preparation of multivalent antimicrobial peptide hydrogel

The CNSs (Laponite XLG, 30 mg; BYK Additives, Germany), a synthetic layered silicate (sodium magnesium lithium silicate), was dissolved in 500 μL of deionized water, quickly stirred with a magnetron for 5 min to form an aqueous CNSs solution. ASAP (sodium polyacrylate, 1.2 mg; Aladdin, China) was then added to further disperse the originally entangled nanosheets and continue to stir up for another 20min. PEG-(RW)3 (50 mg) and metformin were dissolved in 500 μL of deionized water, then slowly and evenly added to the aqueous CNSs solution, dripping while stirring. After stopping stirring, the solution gradually solidified to form a M − C Gel@Met in a few minutes.

2.3. Characterization of CNSs

The morphology of CNSs was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Talos L120C, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) operating at 120 kV. The hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of CNSs were measured using a dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument equipped with a zeta potential analyzer (Zetasizer Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, UK). All measurements were performed at room temperature, and samples were diluted in deionized water prior to analysis to ensure appropriate scattering intensity and stability.

2.4. The morphology of M − C Gel@Met

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, hydrogels were first lyophilized to preserve their internal structure. The dried samples were then cut into appropriate sizes and mounted onto metal stubs using conductive carbon tape. Prior to imaging, the specimens were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold for 30 s to enhance conductivity. The microstructure of the hydrogels, including pore morphology and distribution, was observed and imaged using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi Regulus 8100, Japan).

2.5. Self-healing and injectable test

The prepared M − C Gel@Met was triaged and stained with methyl orange and rhodamine. Two hydrogel blocks were pooled along the interface and photographed to observe the healing situation. To show the injectability and remoldability of M − C Gel@Met, the prepared hydrogel was placed into the injection syringe and injected into the UJS mold.

2.6. Rheological test

Rheological measurements were performed with a rheometer. The M − C Gel@Met was cut into a cylindrical shape with a diameter of 1 cm and a thickness of 0.3 cm before testing. Dynamic frequency sweep (1 % strain),dynamic strain sweep (0.01 %–300 %) and continuous step strain sweep (low strain 1 %, 60 s, high strain 200 %, 60 s) were performed.

2.7. The release of metformin

1 mL of M − C Gel@Met was placed in a dialysis bag (500 Da) and subsequently immersed in 50 mL of PBS buffer. 1 μL of the mixture was taken every three days. The absorbance at 220 nm was read by an ultra-trace spectrophotometer.

2.8. The swelling behavior of M − C Gel@Met

First, the lyophilized hydrogel was soaked in deionized water for 5 h at room temperature. Subsequently the mass of hydrogel was weighed after the surface water was wiped with filter paper. This process was repeated until the weight of the hydrogel was no longer changed. The calculation formula of swelling rate (SR) was as follows:

The Wt refers to the weight of the hydrogel after immersion, and W0 represents the weight of the hydrogel after lyophilization.

2.9. The degradation of M − C Gel@Met

For the degradation test, the initial weight of the lyophilized hydrogels was recorded as M0. The hydrogels were then put into PBS (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. At specific time, the remaining hydrogels were removed and lyophilized, and the weight was recorded as Mt. The calculation formula of degradation rate was as follows:

2.10. In vitro antibacterial activity of the M − C Gel@Met

Antibacterial activity of the M − C Gel@Met was tested against Gram-negative E. coli and Gram-positive S. aureus by colony counting method. In these experiments, 200 μL of the hydrogel was added to 800 μL of bacterial suspension (5 × 105 CFU mL−1) to reach a final volume of 1 mL. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 12 h to ensure the cumulative bactericidal effect was fully manifested for colony counting. After treatment, the suspension was diluted 50-fold, and 100 μL was evenly coated onto LB agar plates using an L-type coating stick (Bioland, China, LS05-1SPK). Plates were incubated for 18 h (E. coli) or 24 h (S. aureus) at 37 °C. Each group was repeated in triplicate. For live/dead staining, 200 μL of the hydrogel was added to 800 μL of bacterial suspension (1 × 106 CFU mL−1) and incubated at 37 °C for 12 h to provide adequate exposure for clear detection of membrane integrity changes. The hydrogel was then removed, and the bacterial suspension was centrifuged (1000 rpm, 5 min) and washed with PBS. SYTO 9/PI working solution was added and incubated for 20 min. The stained bacteria were washed again, resuspended in 200 μL of PBS, and 10 μL of the suspension was dropped onto glass slides for fluorescence microscopy. For SEM observation, 200 μL of the hydrogel was added to 800 μL of bacterial suspension (1 × 108 CFU mL−1) and incubated at 37 °C for 6 h (capture intact bacterial morphology prior to significant degradation), after which bacterial morphology was examined.

2.11. Cell culture

RAW264.7 murine macrophage cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (NEST Biotechnology, China, 209111) and 1 % penicillin–streptomycin (Ketu Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China, RG-CE-8). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2, with medium changes every 2–3 days. Primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) were isolated from the femurs and tibias of C57BL/6 mice (male, 8 weeks old). Briefly, bone marrow cells were flushed out using sterile PBS and passed through a 70 μm cell strainer (Absin, China, abs7232) to obtain a single-cell suspension. After red blood cell lysis, cells were resuspended in complete α-MEM medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (NEST Biotechnology, China, 209111), 1 % penicillin–streptomycin (Ketu Biotechnology, RG-CE-8), and recombinant murine M-CSF (20 ng/mL; Yeasen, China, 91109ES76) to promote macrophage differentiation. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5 % CO2. The medium was replaced every 2–3 days. After 5–7 days of induction, adherent cells exhibiting macrophage morphology were collected and used for subsequent experiments.

Primary bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were isolated from the femurs and tibias of Sprague-Dawley rats (male, 8 weeks old). Briefly, bone marrow was flushed with complete DMEM containing 10 % FBS and filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer. The cell suspension was seeded in culture flasks and incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. Non-adherent cells were removed after 24 h, and the medium was replaced every 2–3 days. Cells at passage 3–5 were used for subsequent experiments. For osteogenic differentiation, BMSCs were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured with osteogenic induction medium composed of DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 100 nM dexamethasone (all from Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The induction medium was refreshed every 2–3 days, and cells were harvested for analysis after 7 or 21 days, depending on the assay.

To evaluate the biological effects, hydrogel extracts were prepared by immersing sterilized hydrogels (0.1 g/mL) in complete DMEM at 37 °C for 24 h, followed by filtration (0.22 μm). The extracts were then used to treat cells in vitro (Control group: no extract; M − C Gel group: extract from metformin-free hydrogel; M − C Gel@Met group: extract from metformin-loaded hydrogel).

2.12. CCK-8

The cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 kit (Yeasen, China) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and allowed to adhere overnight. Subsequently, the culture medium was replaced with different hydrogel extract solutions. After 24 h of treatment, the extract-containing medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing 10 % (v/v) CCK-8 reagent. The cells were then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in the dark. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

2.13. Live/Dead staining

Live/dead cell staining was performed using the Calcein-AM/PI assay kit (Yeasen, China) to evaluate cell viability after treatment with hydrogel extracts. Briefly, cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and cultured overnight. Then, the medium was replaced with hydrogel extract solutions prepared by soaking hydrogels in complete medium. After 24 h of incubation, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with Calcein-AM/PI working solution (Calcein-AM: 2 μM; PI: 4.5 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C, protected from light. Fluorescence images were captured using a fluorescence microscope, with Calcein-AM (green) indicating live cells and PI (red) indicating dead cells. For the direct-contact assay, hydrogels were formed in situ in 24-well plates by mixing precursor solutions directly into each well (300 μL per well), followed by gelation at 37 °C. After gelation, the hydrogels were sterilized by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light for 30 min in a biosafety cabinet. Subsequently, 2 × 104 cells were seeded directly onto the surface of each hydrogel and cultured for 24 h. Live/dead staining was then performed as described above using Calcein-AM (2 μM) and PI (4.5 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark.

2.14. Hemolysis test

Blood samples were collected from the tail vein of rats and diluted with hydrogel extract and appropriate isotonic diluent at a ratio of 1:10. The diluted samples were put into centrifuge tubes and the speed and time of the centrifuge were set at 3000 rpm for 5–10 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant liquid was observed for its properties, and if there was hemolysis, the supernatant appeared to be a light-red transparent liquid.

2.15. Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were inoculated in well plates at a suitable density according to the experimental requirements. After completion of the culture and specific interventions, the supernatant was replaced and washed with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were fixed by adding 4 % paraformaldehyde for 15 min. After washing with PBS, the membrane was broken and punched by adding 0.1 % Triton solution. Incubate for 1 h using the containment solution. After washing with PBS, add primary antibodies staining working solution and incubate at 4 °C overnight. The primary antibodies included anti-RUNX2 Rabbit pAb (Abclonal, A2851, 1:200), anti-OCN Rabbit mAb (Abclonal, A20800, 1:200), anti-ARG1 Rabbit pAb (Proteintech, 16001-1-AP, 1:200), and anti-iNOS Mouse mAb [EPR16635] (Abcam, ab210823, 1:200). The primary antibody was washed clean by adding PBS, fluorescent secondary antibody working solution was added, including Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488, Abcam, ab150077, 1:500) and Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594, Abcam, ab150120, 1:500). Cytoskeletal staining was performed using Actin-Tracker Red-Rhodamine (Beyotime, C2207S, 1:100). Fluorescent secondary antibody incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, DAPI staining solution was added, and the nuclei of the cells were stained by test incubation for 10 min the cells were observed and photographed under a confocal microscope.

2.16. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RNA was extracted from mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) treated with different hydrogels under LPS stimulation for 24 h. Cells were seeded at 5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates with 200 μL of hydrogel extract and 2 mL of culture medium per well.

RNA was extracted from rat bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) treated with different hydrogels during osteogenic induction for 4 days. Cells were seeded at 5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates with 200 μL of hydrogel extract and 2 mL osteogenic medium per well.

Total mRNA was extracted using Beyozol reagent (R0011, Beyotime). The complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared according to a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). RT-qPCR was performed following an iTapTM Universal SYBR® Green Supermix kit (Bio- Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) on a CFX96™ Real-Time PCR System (Bio- Rad). Transcript levels of related gene were evaluated. Relative expression levels of target genes were calculated using the threshold cycle (CT) values and comparative Ct (2-ΔΔCt) method.

For direct-contact experiments, BMMs were seeded onto pre-formed, UV-sterilized hydrogels in 12-well plates (400 μL hydrogel/well) at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. After 24 h of LPS stimulation (100 ng/mL), hydrogels containing adherent cells were digested with 0.25 % trypsin-EDTA at 37 °C for 5–10 min. The resulting cell suspension was collected for RNA extraction, followed by cDNA synthesis and RT-qPCR as described above.

2.17. Flow cytometry

For the identification of macrophage polarization, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) were treated under the same conditions as described in Section 2.16 for 24 h. After incubation, cells were gently washed with PBS and detached using trypsin. The collected cells were then resuspended in PBS containing 2 % fetal bovine serum (FPBS) and incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. The following antibodies were used: APC-anti-mouse-CD11b (101211, 1:100; Biolegend), FITC anti-mouse CD86 Antibody (159219, 1:100; Biolegend), and FITC anti-mouse CD206 (MMR) Antibody (141703, 1:100; Biolegend). For direct-contact experiments, BMMs were cultured on hydrogels in 12-well plates under the same conditions as described in Section 2.16. After 24 h, cells were recovered by trypsin digestion, filtered, and stained with CD11b, CD86, and CD206 antibodies. Cells were washed twice with FPBS and analyzed using a Thermo Fisher Attune™ NxT Flow Cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

For phenotypic characterization of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), third-passage cells were harvested and stained with surface markers commonly used to identify mesenchymal stem cells. The following PE- or FITC-conjugated antibodies were used: anti-CD29-PE (102207, BioLegend, 1:100), anti-CD90-PE (202523, BioLegend, 1:100), anti-CD45-PE (202207, BioLegend, 1:100), and anti-CD105-FITC (GTX60377, GeneTex, 1:100). After 30 min of incubation at 4 °C in the dark, cells were washed with FPBS and analyzed using the Thermo Fisher Attune™ NxT Flow Cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

2.18. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq)

BMMs treatment and RNA harvesting conditions were identical to those described in Section 2.16. The transcriptome sequencing was conducted by OE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Total RNA was extracted from cells using the TRIzol reagent (Yeasen, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA quality and concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). RNA integrity was evaluated on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). RNA with an RNA integrity number (RIN) above 7.0 was selected for sequencing. RNA libraries were constructed using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to generate paired-end reads. Raw data was processed by removing adapters and low-quality sequences. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using DESeq2, and functional enrichment was analyzed using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA).

2.19. Metabolomics analysis

For metabolomics analysis, BMMs were treated with M − C Gel@Met or control conditions. The cells were harvested, and intracellular metabolites were extracted using cold methanol (MeOH) and chloroform (CHCl3) as solvents. After vortexing and sonication, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove debris. The supernatants were dried under nitrogen gas and stored at −80 °C until analysis. The metabolites were analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on an Agilent 1290 UPLC system coupled to an Agilent 6470 QQQ mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, USA). The data were processed using MassHunter software (Agilent Technologies, USA), and differential metabolites between the groups were identified based on their retention time and m/z ratios. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to assess data quality, and orthogonal projections to latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was used to observe differences between groups studied. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed to identify metabolic pathways involved in lipid metabolism and energy metabolism, and GSEA was used to further explore specific metabolic pathways.

2.20. Western blot

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Beyotime, China) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Switzerland). The protein concentration was measured using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Yeasen, China). Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were loaded onto 10 % SDS-PAGE gels and electrophoresed at 100 V for 1.5 h. The separated proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Beyotime, China) at 250 mA for 2 h. After blocking with 5 % non-fat milk in TBST for 1 h, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-NLRP3 (1:1000, A24294, ABclonal), anti-Caspase-1 (1:1000, A18646, ABclonal), anti-GSDMD (1:1000, A20728, ABclonal), anti-IL-18 (1:1000, A23999, ABclonal), anti-β-catenin (1:1000, A19657, ABclonal), anti-phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) (1:1000, AP0039, ABclonal), anti-GSK3β (1:1000, A11798, ABclonal), anti-Runx2 (1:1000, A11753, ABclonal), anti-Sp7/Osterix (1:1000, A18699, ABclonal), and anti-β-actin (1:1000, AC026, ABclonal). The membranes were then washed with TBST three times and incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were detected using the ECL detection system (Thermo Fisher, USA), and imaging was performed with a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, USA). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, USA).

2.21. Alizarin red staining (ARS)

Alizarin red staining steps refer to the instructions of Alizarin Red Staining Solution of Beyotime. Inoculate the cells in 24-well plates according to the experimental requirements. After a certain period of interventional culture (21 days), remove the culture supernatant, wash it three times with PBS, and fix it with 95 % ethanol for 10 min. After fixation, cells were washed with PBS, appropriate amount of alizarin red S staining solution was added and covered well, incubated in the oven at 37 °C for 30 min, washed well with distilled water, and subsequently microscopic images were taken under the microscope. The calcium nodules after Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining were dissolved using a 10 % cetylpyridinium chloride solution, and the optical density (OD) was then recorded at 560 nm.

2.22. Alkaline phosphatase staining (ALP)

The BCIP/NBT alkaline phosphatase chromogenic kit was used for the experiments. After the cells were cultured according to the experimental design, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were fixed with a fixative such as 4 % paraformaldehyde, then the fixative was removed and the cells were washed with PBS. The working solution was added into the plate to the extent that the cells were covered by the working solution. Afterwards, the plate was wrapped in tinfoil to protect the plate from the light, and the plate was incubated at room temperature, and the incubation time could be extended according to the development of the chromogenic conditions until the color developed to the expected shades. The chromogenic reaction was terminated by removing the working solution of the BCIP/NBT staining solution, and the reaction of the chromogenic reaction was terminated by washing the plate with deionized water for 1–2 times. The staining of the cells in the brightfield was observed in the microscope, and the reaction of the chromogenic reaction was photographed.

2.23. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining

A TRAP staining kit (Sigma) was used in this experiment. The dye solution was prepared according to the instructions. For osteoclast induction, BMMs and RAW264.7 cells were induced by RANKL (50 ng/mL). For cell staining, the cells were first fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 15 min and then incubated with TRAP dye solution for 40 min. The positive cells were observed under an inverted optical microscope.

2.24. Animal models

To establish a type 2 diabetes (T2DM) rat model, male SD rats (8 weeks old) are first fed with a high-fat diet (HFD) for 8 weeks to induce metabolic disturbances. Then low-dose streptozotocin (STZ) was administered intraperitoneally (40 mg/kg). Blood glucose levels were measured in blood obtained from the tail veins of the rats, and the successful establishment of the diabetes model was confirmed through continuous blood glucose monitoring with blood glucose levels ≥16.7 mmol/L. After establishing T2DM rat model, a total of 36 male Sprague-Dawley rats (8 weeks old) were used and randomly divided into three groups (n = 12 per group): Control, M − C Gel, and M − C Gel@Met. Under general anesthesia with pentobarbital, the femoral condyle is exposed through a small incision. A cylindrical defect (2 mm in diameter and 2 mm in depth) was created at the distal femoral condyle using a low-speed precision dental drill under sterile conditions with continuous saline irrigation. After defect creation, the bone cavities were filled with the corresponding hydrogel formulations according to group assignment (Control: no hydrogel; M − C Gel: filled with M − C Gel; M − C Gel@Met: filled with M − C Gel loaded with metformin). The wound was then sewn up, and the rats are allowed to recover. Femoral tissues are obtained at 2, 4, and 8 weeks post-surgery for Micro-CT and histological analysis.

2.25. H&E staining

Sequentially put the slices into the following dye vats for reprocessing: xylene I-10 min, xylene II-10 min, anhydrous ethanol I-5 min, anhydrous ethanol II-5 min, 95 % alcohol 5 min, 90 % alcohol 5 min, 80 % alcohol 5 min, 70 % alcohol 5 min, distilled water washing. Then transfer to Harris hematoxylin dye solution for 3–8 min, wash with tap water, differentiate with 1 % hydrochloric acid alcohol for several seconds, wash with tap water, turn blue with 0.6 % ammonia water, and wash with running water. Dye the slices in eosin dye solution for 1–3 min. Finally, put the slices into 95 % alcohol I-5 min, 95 % alcohol II-5 min, anhydrous ethanol I-5 min, anhydrous ethanol II-5 min, xylene I-5 min, xylene II-5 min in turn to dehydrate and be transparent. Take the slices out of xylene and air dry slightly and seal the slices with neutral gum. Microscopic examination, image acquisition and analysis.

2.26. Masson staining

Masson trichrome staining was performed using a commercial staining kit (Masson Trichrome Staining Kit, G1340; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., China) according to the manufacturer's protocol with minor modifications. Briefly, tissue samples were fixed in 10 % neutral buffered formalin, dehydrated through graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at a thickness of 4–5 μm, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through descending ethanol concentrations (100 %, 95 %, 70 %), followed by rinsing in distilled water. Slides were then stained in acidic magenta solution for 5–15 min, followed by differentiation in acidic ethanol (1 % hydrochloric acid in ethanol) to remove excess red stain. Subsequently, sections were counterstained with Brilliant Blue solution for 5–10 min. After staining, the slides were dehydrated through graded ethanol (70 %, 95 %, 100 %), cleared in xylene, and finally mounted with a neutral resinous medium for microscopic observation.

2.27. Micro-CT

Rat femoral tissue specimens were removed from the fixative and placed in a high-resolution micro-CT scanner (SkyScan 1176, Aartselaar, Belgium) with the following set parameters: resolution of 9 μm, angle of rotation of 0.7°, voltage of 60 kV, and current of 170 mA. Subsequently, the 2D images were reconstructed in three dimensions using the SkyScan RECON software, and quantitative analyses of the Bone Mineral Density (BMD, mg/cm3), Bone Volume/Tissue Volume Ratio (BV/TV, %), Bony Trabeculae Quantity (Tb.N, mm-1), and Bony Trabeculae Thickness (Tb.Th, μm) were performed.

2.28. Immunohistochemical staining

Tissue sections were prepared for antigen restoration by immersion in 5 % hydrogen peroxidase at 37 °C for 10 min, after which they were incubated with primary antibodies for inflammatory factors including TNF-α (1:500, Abclone, China), IL-10 (1:500), and osteogenic index including osteocalcin (OCN, 1:500), and OSTERIX (1:600; all from Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) over night at 4 °C. Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG(H + L) HRP (Shandong Sparkjade Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China, EF0002) were utilized to combine with the primary antibodies according to the host of primary antibodies. Diaminobezidin staining was then conducted to color the positive cells. Microscopic images were acquired using an inverted light microscope. The quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software.

2.29. Statistics

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed with an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test for single comparisons with GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare data from more than two groups. Bonferroni correction was used with one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of M − C Gel@Met hydrogel

In this study, a dynamic hydrogel based on electrostatic crosslinking and loaded with metformin was prepared for use in facilitating bone defect repair in a diabetic setting. To prepare hydrogels, an antimicrobial peptide with multiple guanidinium groups (RWRWRWC) modified polyethylene glycol molecules (PEG-Mal) by Michael addition reaction (Fig. S1). The chemical structure of this antimicrobial peptide (AMP) was characterised by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry (EI-MS). As shown in Fig. 1A, AMP has a high purity (97.06 %). In addition, the monoisotopic mass [M+2H]2+ of Azido-AMP was measured at 574.4 Da, which is consistent with its theoretical molecular weight (1148 Da) (Fig. 1B). As shown in the NMR spectra, with the disappearance of the maleimide characteristic peaks as well as the appearance of the AMP characteristic peaks, this indicates the successful synthesis of PEG-AMP (Fig. 1C). CNSs exhibited a uniformly dispersed nanosheet structure under TEM (Fig. S1B). The average hydrodynamic diameter was measured to be 21.55 nm (Fig. S1C), and the zeta potential shifted from approximately −42.7 mV to −13.5 mV upon metformin loading, confirming successful formation of CNS@Met (Fig. S1D). As shown in Fig. 1D, upon the addition of CNSs and metformin, the PEG-AMP solution underwent a rapid gelation process. The viscosity of the system gradually increased until its state changed completely from flow to gel. The structure and chemical composition of resultant hydrogel (M − C Gel@Met) were then characterized. SEM images showed that M − C Gel possessed a relatively homogeneous pore structure (Fig. 1E). Further quantitative analysis showed that the average pore size of the hydrogel was about 73.5 μm, which facilitates cell movement and nutrient transport (Fig. 1G). Furthermore, the addition of metformin did not provide a significant change in the pore structure of M − C Gel@Met. The pores of the hydrogel were slightly reduced to 71.4 μm (Fig. 1F and H).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of M-C Gel@Met hydrogel. (A) HPLC spectrum and (B) ESI-MS spectrum of (RW)3C-NH2. (C) 1H NMR spectrum of PEG-AMP. (D) The formation of M − C Gel@Met hydrogel. (E, F) SEM images of M − C Gel (E) and M − C Gel@Met (F). (G, H) Pore size distribution of M − C Gel (G) and M − C Gel@Met (H). (I) Self-healing ability of M − C Gel@Met hydrogel. (J) Injectability and remoldability of M − C Gel@Met hydrogel. (K) Dynamic oscillatory frequency sweep (strain = 1 %) of M − C Gel@Met. (L) Strain amplitude sweep (γ = 155 %, frequency = 1 rad s−1) of M − C Gel@Met. (M) Continuous step strain sweep (strain = 1 % or 200 %, frequency = 1 rad s−1) of M − C Gel@Met. (N) Swelling ratio of M − C Gel@Met over time.

As a dynamic material based on cross-linking by electrostatic action, we expect M − C Gel@Met to show typical dynamic properties, such as self-healing ability, remoldability, and injectability. As shown in Fig. 1I, the cut hydrogel blocks healed within 30 min after reassembly and did not break after pulling. And, the hydrogel was injected with a needle to form a complete monogram, which demonstrated excellent injectable properties (Fig. 1J). Rheological tests were further performed to examine the dynamic mechanism of M − C Gel@Met. In Fig. 1K, the hydrogel storage modulus (G′) was higher than the loss modulus (G″), indicating that it had elastic gel-like properties. It was worth mentioning that the values of G′ and G″ could be basically kept constant in the frequency range, indicating that the dynamic structure of M − C Gel@Met had good stability. Further, the strain sweeps indicated that the hydrogel had typical shear thinning properties. The values of G′ and G″ decreased gradually from steady with increasing strain and exhibit sol properties above the critical strain region (γ = 155 %) (Fig. 1L). We further found that the mechanical properties of hydrogel recovered as before when it was applied with alternative strain between 1 % and 200 % (Fig. 1M). The above rheological tests well revealed the physical dynamic mechanism of this M − C Gel@Met.

Since M − C Gel@Met was loaded with metformin, we focused heavily on the release of metformin. As shown in Fig. 1N–M − C Gel@Met consistently released metformin in the early stages, which can effectively relieve the inflammation caused in the early stage of diabetic bone defects. After 10 days, about 70 % of metformin had been released, and the release of the drug became slow. There was no doubt that this release process was very suitable for the repair needs of diabetic bone defects.

3.2. Antibacterial activity of hydrogels

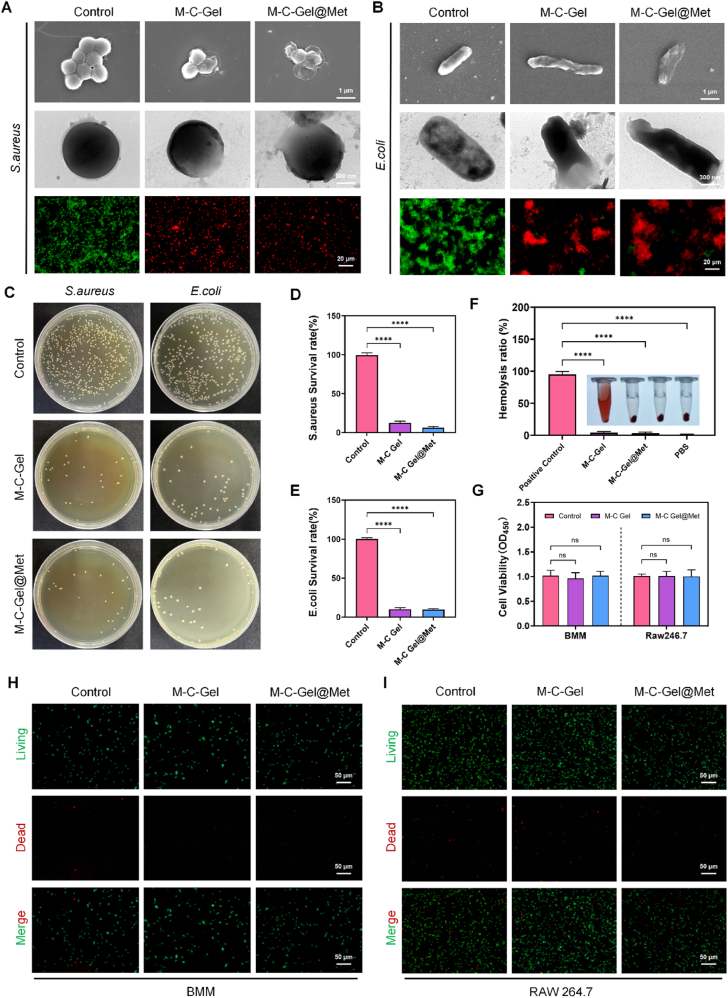

Diabetic patients are more susceptible to infections in case of bone defects or skin breaks than in the healthy state [20]. Therefore, in order to observe the antimicrobial effect of the hydrogel, in vitro bacterial cultures were first performed. Under standard incubation conditions, we observed that MC-Gel hydrogel significantly inhibited the proliferation of S. aureus and E. coli compared to the control group. Scanning electron microscopy analyses revealed substantial morphological alterations in bacteria subjected to MC-Gel hydrogel treatment. Co-culturing with M − C Gel and M − C Gel@Met hydrogels accelerated bacterial cell wall rupture, thereby promoting bacterial death. Similarly, bacterial live-dead staining results indicated an increase in red fluorescence-stained dead bacteria and a decrease in green fluorescence-stained live bacteria (Fig. 2A–B). Subsequently, the antibacterial efficacy of the hydrogels was further validated through colony formation assays (Fig. 2C). The results demonstrated a significant reduction in S. aureus and E. coli colony formation following M − C Gel and M − C Gel@Met treatment, with a markedly lower bacterial survival rate compared to the control group (Fig. 2D–E).

Fig. 2.

In vitro antibacterial activities of M-C Gel and M-C Gel@Met. (A, B) Live/dead staining (bottom), TEM (middle), and SEM (top) images of S. aureus (A) and E. coli (B) after 6 h of treatment with M − C Gel and M − C Gel@Met. (C) Bacterial colony images of E. coli and S. aureus treated with M − C Gel and M − C Gel@Met for 12 h. (D, E) Viability of S. aureus (D) and E. coli (E) after treatment with M − C Gel and M − C Gel@Met for 12 h. (F) Hemolysis assay showing erythrocyte compatibility. (G) CCK-8 assay results for RAW 264.7 and BMM cells. (H–I) Live/dead cell staining assay for BMM and RAW 264.7 cells. Statistical significance is indicated as ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 compared to the control group and ns indicates no significant difference.

To assess the biocompatibility of the hydrogels, hemolysis assays were performed (Fig. 2F). The findings revealed that M − C Gel and M − C Gel@Met did not induce significant hemolysis, indicating a favorable biosafety profile. Furthermore, we evaluated the cytocompatibility of the M − C Gel@Met hydrogel. Using the CCK-8 assay, we assessed the hydrogel's effect on the proliferation of RAW264.7 cells and primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs). After 3 days of co-culture, no significant cytotoxicity was observed (Fig. 2G). Similarly, live-dead staining results from both extract-based treatment (Fig. 2H–I) and direct-contact assays (Fig. S2A–B) showed no notable increase in PI-positive (red-stained) dead cells in the M − C Gel@Met group compared to the control group. These findings indicate that the M − C Gel hydrogel exhibits good biocompatibility and does not induce significant cytotoxicity, further supporting its favorable safety profile.

3.3. M − C Gel@Met regulates macrophage polarization-mediated inflammatory cytokine release

Under sustained high levels of blood glucose, both glycosylation end products and oxidative stress products can lead to immune cell activation and release of inflammatory cytokines [21]. Previous studies have shown that the macrophage polarization phenotype shifted and polarized toward a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype [22]. Thus, altered macrophage polarization state in the diabetic immune microenvironment is critical in regulating the inflammatory response. In order to validate the immunomodulatory effects of M − C Gel@Met in the diabetic microenvironment, we constructed cell culture models in vitro. To mimic the DM microenvironment, we added 25.5 mM glucose as well as 100 ng/mL LPS to the culture medium [23]. By comparison with cells under conventional culture, macrophages in the DM mimic microenvironment expressed more inflammatory cytokines such as iNOS and IL-6, showing a predominantly M1 polarization direction. To investigate the effect of M − C Gel@Met on macrophage polarization, we first examined the altered expression of proteins associated with polarization phenotypes. Immunofluorescence staining showed that compared with the normal group, both the M − C Gel and M − C Gel@Met groups decreased the expression of iNOS protein and promoted the expression of Arg-1, which was more significant in the M − C Gel@Met group (Fig. 3A and B). In order to further observe the altered macrophage phenotypic ratio under M − C Gel@Met intervention, we performed flow assay. The results showed that the percentage of CD11b+/CD86+ M1 macrophages was as high as 43 % in the DM simulated microenvironment, whereas the percentage of CD11b+/CD206+ M2 macrophages was extremely low. The percentage of CD11b+/CD86+ double-positive macrophages was significantly reduced in the M − C Gel@Met group. In contrast, CD11b+/CD206+ macrophages were activated with an increased ratio (Fig. 3D–G). In addition to extract-based treatments, we further evaluated the direct-contact effects of hydrogels on macrophage polarization. As shown in the representative flow cytometry plots (Fig. S3B and S3C), a similar trend was observed: the percentage of CD11b+/CD86+ M1 macrophages was markedly reduced in the M − C Gel@Met group, while CD11b+/CD206+ M2 macrophages were increased, further supporting the immunomodulatory capability of the hydrogel under both extract-based and contact conditions.

Fig. 3.

Effect of M-C Gel@Met on the immune status of macrophages. (A) Immunofluorescence co-staining of macrophage marker proteins and polarization phenotype-related protein expression in an inflammation-mimicking microenvironment. (B) Relative fluorescence intensity analysis of phenotype-related proteins (iNOS and Arg-1) in the Control, M − C Gel, and M − C Gel@Met groups. (C) RT-qPCR analysis of inflammatory cytokine gene expression, including IL-10, IL-1β, IL-6, and Tnf-α. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of CD11b+/CD86+ double-positive M1-phenotype macrophages. (E) Quantification of CD11b+/CD86+ cell percentage. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of CD11b+/CD206+ double-positive M2-phenotype macrophages. (G) Quantification of CD11b+/CD206+ cell percentage. Statistical significance is indicated as ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ns indicates no significant difference.

Secretion and release of cytokines are the main mechanisms by which macrophages function in immunomodulation [24]. Large amounts of proinflammatory cytokines secreted by M1 macrophages help generate an inflammatory microenvironment in DM, which hinders the bone healing process in defect area [25]. Although the ways and modalities vary, numerous researchers have confirmed that reducing the expression of inflammatory cytokines is an important and direct way to alleviate inflammation [26,27]. Hence, we detected changes in inflammatory cytokine gene expression levels in different cell groups using RT-qPCR. As shown in Fig. 3C, we found that M − C Gel@Met effectively inhibited the gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, and promoted the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 to some extent. Consistent results were also observed under direct-contact co-culture conditions, further confirming the hydrogel's robust anti-inflammatory effect across different experimental setups (Fig. S3A). Together, these results confirm that M − C Gel@Met is effective in decreasing the M1/M2 macrophage ratio and reducing the synthesis and release of inflammatory cytokines in the DM microenvironment. Based on this, we further collected macrophages from DM mimic culture (DM) and M − C Gel@Met intervened macrophages under DM conditions for high-throughput transcriptome sequencing. The results showed that M − C Gel@Met significantly reduced the expression of intracellular inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin family, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and TNF family, compared with DM, and these confirmed the more broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effects of M − C Gel@Met (Fig. S4A). Additionally, pathway analysis revealed that M − C Gel@Met treatment modulated several key immune-related pathways, such as the inflammatory response, cytokine activity, and chemokine-mediated signaling, which were significantly altered in the diabetic microenvironment (Fig. S4B).

3.4. M − C Gel@Met regulates macrophage immunoreactivity by influencing macrophage metabolism

To further explore the pathways and mechanisms of macrophage immunomodulation by M − C Gel@Met, we analyzed the high-throughput transcriptome sequencing performed on macrophages cultured in DM-mimicking culture (Control) and DM condition with M − C Gel@Met intervention. The PCA analysis demonstrated that the sample clustering was consistent and reproducible, indicating reliable homogeneity of the samples (Fig. 4A). The volcano plot revealed a total of differentially expressed genes between the M − C Gel@Met and Control groups, with 143 significantly downregulated and 87 significantly upregulated genes (Fig. 4B). The heatmap of differentially expressed genes further demonstrated that M − C Gel@Met significantly altered the gene expression profile of macrophages (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

M-C Gel@Met regulates macrophage expression of pathways associated with immune-inflammatory responses. (A) PCA analysis of high-throughput RNA sequencing data. (B) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between the Control and M − C Gel@Met groups. (C) Heat map of differentially expressed genes in the Control and M − C Gel@Met groups. (D) GO enrichment analysis of total differentially expressed genes. (E) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of total differentially expressed genes. (F) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of the TNF signaling pathway. (G) GSEA of the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway. (H) Heatmap of key inflammatory-related genes in the Control and M − C Gel@Met groups. (I) Western blot analysis of NLRP3, Caspase 1, GSDMD (full-length and cleaved forms), IL-18, and ACTB in macrophages treated with M − C Gel or M − C Gel@Met.

GO enrichment analysis of all differentially expressed genes indicated that M − C Gel@Met predominantly influenced genes related to inflammatory responses, immune responses, and chemokine signaling pathways, further supporting its immunomodulatory effects (Fig. 4D). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that M − C Gel@Met treatment significantly modulated key immune-inflammatory pathways, including the TNF signaling pathway and NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, which are crucial for macrophage activation and inflammatory responses (Fig. 4E). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of the TNF signaling pathway (Fig. 4F) and NOD-like receptor signaling pathway (Fig. 4G) revealed a significant enrichment of M − C Gel@Met-related changes in these pathways, with a notable decrease in the enrichment score (ES) in the treated group, further supporting the regulatory role of M − C Gel@Met in immune-inflammatory responses. The heatmap of key inflammatory-related genes, such as IL1b, IL6, IL18, TNF, Nfkb1, Casp1, and Nlrp3, confirmed that M − C Gel@Met significantly altered the expression of genes involved in inflammation and immune responses (Fig. 4H). Additionally, Western blot analysis of NLRP3, Caspase 1, GSDMD (both full-length and cleaved forms), and IL-18 further validated the regulatory effect of M − C Gel@Met on key inflammatory mediators, indicating its potent ability to modulate macrophage immune-inflammatory responses (Fig. 4I).

Given the close relationship between macrophage polarization and metabolic reprogramming, we analyzed the transcriptomic profiles of macrophages treated with M − C Gel@Met and found that several metabolism-related pathways were significantly enriched, as revealed by KEGG pathway analysis. Notably, pathways related to amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, and xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism were among the most enriched (Fig. S4C). These metabolic alterations suggest that M − C Gel@Met may facilitate the transition of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory to a pro-reparative phenotype by modulating key metabolic programs, thereby contributing to immune homeostasis and tissue regeneration in the diabetic microenvironment.

To investigate the underlying mechanisms driving macrophage immunomodulation by M − C Gel@Met, we performed untargeted metabolomics analysis of macrophages using LC-MS/MS to investigate metabolic reprogramming induced by the hydrogel treatment. The OPLS-DA analysis (Fig. 5A) showed a clear separation between the Control and M − C Gel@Met groups, indicating obvious metabolic differences. Further classification of metabolites (Fig. S5A) revealed that a large proportion of the altered metabolites were lipids and organic compounds. This suggests that M − C Gel@Met notably alters the metabolic profiles of macrophages, particularly in lipid metabolism and energy-related processes. Similarly, the super class distribution in Fig. S5B confirmed that most of the affected metabolites were lipids and organic molecules, which are closely related to metabolic and inflammatory responses.

Fig. 5.

M-C Gel@Met influences lipid metabolism-related metabolic processes involved in macrophage immunomodulation. (A) OPLS-DA analysis of differentially expressed metabolites in the Control and M − C Gel@Met groups. (B) Volcano plot of differentially expressed metabolites between the Control and M − C Gel@Met groups. (C) Log2 fold-change analysis of significantly altered metabolites. (D) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of lipid metabolism-related differentially expressed metabolites. (E) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed metabolites related to fatty acid metabolism. (F) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of the arachidonic acid metabolism pathway. (G) Heatmap of lipid metabolism-related differentially expressed metabolites. (H) GSEA of the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. (I) Heatmap of differentially expressed metabolites related to nucleotide metabolism and energy metabolism.

The volcano plot further highlighted 125 significantly downregulated metabolites (blue dots) and 139 significantly upregulated metabolites (red dots) between the two groups, confirming the regulatory effect of M − C Gel@Met on metabolite expression (Fig. 5B). These changes are visually summarized in Fig. S5C, where the heatmap clearly illustrates the differential expression of metabolites between the Control and M − C Gel@Met groups, with the color scale indicating relative abundance. Red indicates higher expression, while blue represents lower expression of metabolites. The Log2 fold-change analysis showed that certain lipid metabolites, such as Dodeca-6,8,10-Trienediolcarnitine and 15-Keto-Pgf2alpha, exhibited significant fold changes, further supporting the impact of M − C Gel@Met on lipid metabolism (Fig. 5C). These metabolites are crucial in energy metabolism and inflammatory pathways, which may contribute to the modulation of macrophage activation and immune responses.

Further KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed separately on downregulated and upregulated metabolites. The results showed that the downregulated metabolites were significantly enriched in the arachidonic acid metabolism pathway (Fig. 5D), while the upregulated metabolites were mainly associated with the oxidative phosphorylation pathway (Fig. 5E), both of which are closely linked to macrophage activation and immune regulation.

Arachidonic acid derivatives such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes are central to the inflammatory response, and their metabolic modulation has been shown to affect macrophage polarization toward either the pro-inflammatory M1 or anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes [28]. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of the arachidonic acid metabolism pathway showed a negative enrichment score (ES) in the M − C Gel@Met-treated group, indicating that M − C Gel@Met effectively suppresses arachidonic acid metabolism, thereby reducing inflammatory responses in macrophages (Fig. 5F). Additionly, the heatmap of lipid metabolism-related metabolites, highlighting significant alterations in key metabolites such as arachidonic acid derivatives, which further support the involvement of lipid metabolism in M − C Gel@Met's action (Fig. 5G).

Moreover, the oxidative phosphorylation pathway was upregulated in macrophages treated with M − C Gel@Met, further supporting the notion that M − C Gel@Met influences the metabolic state of macrophages to favor tissue repair (Fig. 5H–I). Oxidative phosphorylation is the primary energy production mechanism in M2 macrophages, which rely on mitochondrial respiration for energy during the resolution of inflammation and tissue regeneration. This metabolic shift from glycolysis (predominantly used by M1 macrophages) to oxidative phosphorylation indicates a switch in macrophage metabolism, enhancing their capacity for repair and promoting anti-inflammatory functions [29].

Overall, this analysis revealed a profound shift in the metabolic profile of macrophages upon treatment with M − C Gel@Met. Specifically, the results indicated significant modulation of lipid metabolism-related pathways, which play a pivotal role in macrophage polarization and function in inflammation and tissue repair.

3.5. M − C Gel@Met exerts osteogenic/osteoclastic effects through immunomodulation

Affected and regulated by the inflammatory microenvironment, the metabolic state of bone tissue under diabetic conditions is imbalanced, showing excessive osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and osteoblast-mediated inhibition of bone formation [27]. Therefore, remodeling the metabolic balance of bone tissue by modulating the immune microenvironment is an important means to promote the healing of bone defective tissue [28]. To verify this, we first co-cultured macrophages with M − C Gel@Met and prepared conditioned media by extracting the supernatant. During osteogenic induction, we added different conditioned media separately for induction intervention (Fig. 6A). ARS staining results (Fig. 6B and G) showed more red positively stained calcium salt crystals in the M − C Gel@Met group compared to the Control group, while ALP staining results (Fig. 6C and H) similarly showed a higher number of ALP-positive cells and significantly higher ALP viability expression in the M − C Gel@Met group of osteoinduced stem cells.

Fig. 6.

M-C Gel@Met affects osteogenic and osteoclast activation by modulating the immune microenvironment. (A) Schematic representation of the preparation of conditioned media from macrophages treated with Control, M − C Gel, and M − C Gel@Met in an inflammatory microenvironment and their subsequent intervention in osteoblast differentiation. (B) Macroscopic and microscopic views of Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining of BMSCs to evaluate osteogenic differentiation. (C) Macroscopic and microscopic views of Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) staining of BMSCs for osteogenesis-induced differentiation. (D) Western blot analysis of β-catenin, phosphorylated-GSK3β, total GSK3β, Runx2, and Sp7 in BMSCs after treatment with different conditioned media. (E, F) Immunofluorescence co-staining of cytoskeletal phalloidin with osteogenic differentiation-associated proteins OCN (E) and RUNX2 (F) during BMSC osteogenic induction. (G) Quantification of ARS staining absorbance in different groups. (OD = 560 nm) (H) ALP activity assay detection. (I, J) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) analysis of OCN (I) and RUNX2 (J) in BMSC differentiation. (K) RT-qPCR analysis of osteogenic marker gene expression (Runx2, OCN, Col1a1 and SP7). Statistical significance is indicated as ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 compared to the control group and ns indicates no significant difference. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Western blotting results (Fig. 6D) further confirmed that the expression of osteogenesis-related proteins such as β-catenin and Runx2 were significantly increased in the M − C Gel@Met group compared to the Control group, suggesting enhanced osteogenic differentiation. Specifically, the M − C Gel@Met group exhibited higher expression levels of β-catenin, phosphorylated GSK3β (p-GSK3β), GSK3β, Runx2, and Sp7 proteins, all of which are key regulators in osteogenesis, compared to the Control group. These results indicate that M − C Gel@Met promotes osteogenic differentiation by modulating these critical signaling molecules involved in bone formation.

We then further analyzed the expression of osteogenesis-related proteins at different stages of osteogenic differentiation. Specifically, we assessed the expression of RUNX2, an early osteogenic marker, and OCN, a mid-late stage osteogenic marker, at 3 and 7 days of osteogenic induction, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6E and I, OCN expression was significantly upregulated in M − C Gel@Met-treated cells compared to the Control group, indicating enhanced osteogenic differentiation. Similarly, RUNX2 expression was significantly elevated in the M − C Gel@Met-treated group, as shown in Fig. 6F and J, further supporting the role of M − C Gel@Met in promoting osteogenesis. Additionally, we extracted mRNA and detected the expression of osteogenesis-related genes under different interventions. The results showed that the intervention of hydrogel-conditioned medium could promote the expression of Col1a1, RUNX2, OCN, and SP7 genes to different degrees, which was especially significant in the M − C Gel@Met group (Fig. 6K).

During RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis, we added conditioned media collected from macrophages treated with different hydrogels to assess their indirect regulatory effects. TRAP staining results (Fig. S6A) revealed that osteoclast differentiation was remarkably inhibited in the M − C Gel@Met group, as evidenced by the significant reduction in the number and size of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells compared to the Control and M − C Gel groups. This suggests that the hydrogel-conditioned medium effectively suppresses the formation of mature osteoclasts. Additionally, F-actin immunofluorescence staining (Fig. S6B) showed fewer and less well-defined F-actin rings in the M − C Gel@Met group, which are essential for osteoclast attachment and bone resorption, further confirming the impaired osteoclast functionality under this condition. Moreover, qPCR analysis revealed significant downregulation of key osteoclast-specific genes, including CTSK, MMP9, and NFATc1, in the M − C Gel@Met group (Fig. S6C), indicating suppressed transcriptional activation of osteoclastogenesis. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that M − C Gel@Met exerts a potent inhibitory effect on osteoclast differentiation and resorptive activity, likely through macrophage-mediated paracrine mechanisms, thereby contributing to its bone-protective properties during defect repair.

3.6. M − C Gel@Met alleviates inflammatory response and promotes bone healing in diabetic rat bone defect tissues

In order to further verify the therapeutic effect of M − C Gel@Met hydrogel in vivo, we first constructed a bone defect model under the condition of diabetes mellitus (Fig. 7A). After the beginning of the model, the rats exhibited symptoms, such as increased drinking, eating, and urination. Blood glucose levels were measured in blood obtained from the tail veins of the rats, and the successful establishment of the diabetes model was confirmed through continuous blood glucose monitoring with blood glucose levels ≥16.7 mM (Fig. S7A and S7B). Previous studies have demonstrated that DM strongly affects bone turnover, bone morphology, bone mineral density (BMD), and ultimately osteoporosis. To detect changes in bone tissue in DM rats, micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scanning was performed. The analysis results revealed that the amount of bone volume in the femurs of DM rats was significantly reduced compared with that in healthy mice of the same age (Fig. S8A–C). In addition, we observed the healing of bone defects in healthy rats compared with those in DM rats. Micro-CT results showed that after 4 weeks of modeling, the healing of defect sites in DM rats was significantly worse than that in the normal group. Subsequently, we injected hydrogel for therapeutic intervention in different subgroups of DM bone defects and observed the bone tissue growth of the defects at 2, 4, and 8 weeks of treatment, respectively. Micro-CT scanning reconstruction showed that the Control group of DM rats had slow healing of the bone defects, in contrast to the hydrogel treatment group where some healing bone tissue formation was initially observed at 2 weeks, and the M − C Gel@Met group reached a good healing state at 8 weeks (Fig. 7B). By quantitative analysis of bone parameters, we found that there was a significant increase in BMD and bone volume fraction at the defect site after 8 weeks of therapeutic intervention, as well as a good up-regulation of trabecular thickness and trabecular number of the new bone (Fig. 7C). To further observe the histological changes, we performed H&E staining and Masson staining of the tissues. As shown in Fig. 7D–G, in the bone tissues at 8 weeks, the Control group still did not have a complete healing. In contrast, more neoplastic bone trabeculogenesis could be observed at the defect site in the M − C Gel@Met hydrogel treatment group, and a good filling was achieved. These results indicated that M − C Gel@Met could effectively promote the healing of bone defects in DM rats.

Fig. 7.

M-C Gel@Met promotes healing of bone defects in diabetic rats. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure for inducing femoral defects in diabetic rats and hydrogel treatment timeline. (B) Micro-CT scan reconstruction images of femoral condylar defects in diabetic rats at 2, 4, and 8 weeks post-treatment with Control, M − C Gel, and M − C Gel@Met. (C) Bone parameter analysis, including bone mineral density (BMD), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N), and bone volume fraction (BV/TV), at 8 weeks post-treatment. (D) H&E staining images of the defect sites at 8 weeks post-treatment. (E) Quantification of the percentage of new bone tissue area in the region of interest (ROI) from H&E-stained sections. (F) Masson staining images of bone tissue at 8 weeks post-treatment. (G) Quantification of the percentage of new bone tissue area in the ROI from Masson-stained sections. Statistical significance is indicated as ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 compared to the control group and ns indicates no significant difference.

An altered early inflammatory state is a prerequisite for subsequent osteogenic capacity. To further understand the role of M − C Gel@Met hydrogel in inflammatory modulation in vivo, we performed immunohistochemical staining of bone tissues from bone defects treated for 2 weeks. The results showed that DM rats in the Control group had high TNF-α expression and low IL-10 expression at the site of bone defects, suggesting that the tissue was in an inflammatory state. On the contrary, in the M − C Gel@Met group, TNF-α expression was significantly reduced, while IL-10 expression was up-regulated, which provided a favorable microenvironment for tissue repair (Fig. 8A and B).

Fig. 8.

M-C Gel@Met alleviates tissue inflammation and promotes osteogenesis in diabetic (DM) rats. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of inflammatory cytokines (IL-10 and TNF-α) in bone defect tissues at 2 weeks post-treatment. (B) Quantification of IL-10-positive cells and TNF-α-positive cells in bone defect tissues. (C) Immunohistochemical staining of osteogenesis-related proteins (OCN and OSTERIX) in bone defect tissues at 8 weeks post-treatment. (D) Quantification of OCN-positive cells and OSTERIX-positive cells in bone defect tissues. (E) Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of macrophage phenotype markers (CD86 for M1, CD206 for M2) and osteogenic marker OCN in bone defect tissues. Statistical significance is indicated as ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 compared to the control group and ns indicates no significant difference.

Subsequently, we further examined the expression of osteogenesis-related proteins in the tissues at 8 weeks. OCN and OSTERIX expression was significantly up-regulated in the bone tissues of the M − C Gel@Met group compared with the Control group (Fig. 8C and D). Immunofluorescence staining for macrophage phenotype markers (CD86 for M1, CD206 for M2) in the bone defect tissues at 2 weeks further confirmed the modulation of the inflammatory response by M − C Gel@Met (Fig. 8E). In the Control group, there was a high presence of CD86+ macrophages, which are associated with inflammation, while CD206+ macrophages, indicative of an anti-inflammatory phenotype, were low. In contrast, the M − C Gel@Met group showed a significant increase in CD206+ macrophages and a decrease in CD86+ macrophages, particularly at 2 weeks, indicating an improved anti-inflammatory state. These results confirm the in vivo anti-inflammatory effect of M − C Gel@Met and its ability to effectively promote bone metabolism processes toward bone formation.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we present a method for constructing multivalent biomaterials by integrating controlled polymerization and click chemistry. Firstly, we synthesized a multivalent antimicrobial molecules by clicking the antimicrobial peptide (RW)3 onto the 8-arm PEG-Mal via thiol-ene Michael addition. PEG-(RW)3 multivalent antimicrobial molecules display a variety of cationic ligands that enhance bactericidal properties through multivalent binding to bacterial membranes. Secondly, PEG-(RW)3 can also polymerize with CNSs, having anions, to form M − C Gel hydrogels. Finally, Considering the excellent therapeutic effect of metformin on diabetes and carrying cations, we finally synthesized M − C Gel@Met hydrogel to treat diabetic bone defects. The multivalent M − C Gel@Met hydrogels present excellent antimicrobial, inflammation modulating and bone forming properties. As a dynamic biomaterial similar to ECM, M − C Gel@Met hydrogel is remouldable, injectable and self-healing. Furthermore, M − C Gel@Met multivalent antimicrobial hydrogel can be used not only for diabetic bone defects but also for other diabetic complications such as skin defects due to its excellent antimicrobial properties and loaded with metformin. Meanwhile, we also found that metformin not only regulates the inflammatory state of tissue microenvironment, but also promotes osteoblast activity and inhibits osteoclast bone resorption in current study. In summary, the work on multivalent M − C Gel@Met hydrogels with antimicrobial, inflammation-modulating and bone-forming properties provides interesting insights into the biomimetic design of biomaterials. Despite these promising outcomes, certain limitations should be acknowledged. Due to resource constraints, only the Control and M − C Gel@Met groups were included in transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling, which limits the granularity of mechanistic comparisons across hydrogel variants. Moreover, while we demonstrated efficacy in a diabetic bone defect model, the long-term biocompatibility, biodegradation kinetics, and potential off-target effects of the material were not addressed in this study. Additional investigations in multiple disease models and under chronic pathological conditions will be essential to validate its broader translational potential. Altogether, this work highlights the therapeutic promise of multivalent M − C Gel@Met hydrogels and offers insights into the design of dynamic, multifunctional biomaterials for tissue repair in complex disease environments.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Liangliang Wang: Writing – original draft, Software, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Zebin Wu: Visualization, Data curation, Conceptualization. Xu Chen: Software, Methodology, Data curation. Jiaxiang Bai: Software, Project administration. Wenming Li: Methodology, Data curation. Gaoran Ge: Software, Methodology. Wei Zhang: Software. Wenhao Li: Data curation. Yi Qin: Methodology. Gongyin Zhao: Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Yuji Wang: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. Guoqing Pan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization. Yaozeng Xu: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Dechun Geng: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072425, 32222041, 82002321, 82272567 and 82472525), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK2021650), Jiangsu Medical Research Project (ZD2022014), the Special Project of Diagnosis and Treatment Technology for Key Clinical Diseases in Suzhou (LCZX202003), Program of Suzhou Health Commission (GSWS2022002), Changzhou Sci&Tech Program (CJ20230069), Top Talent of Changzhou "The14th Five-Year Plan” High-Level Health Talents Training Project (2022CZBJ060), the Excellent Training Project of Changzhou Medical Center of Nanjing Medical University (CMC2024PY03), Special Program for Introducing Foreign Talents of Changzhou Science and Technology Bureau (CQ20224054), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.102162.

Contributor Information

Yuji Wang, Email: yujiwang@sohu.com.

Guoqing Pan, Email: panguoqing@ujs.edu.cn.

Yaozeng Xu, Email: xuyaozeng@163.com.

Dechun Geng, Email: szgengdc@suda.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Khosla S., Samakkarnthai P., Monroe D.G., Farr J.N. Update on the pathogenesis and treatment of skeletal fragility in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021;17(11):685–697. doi: 10.1038/s41574-021-00555-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofbauer L.C., Busse B., Eastell R., Ferrari S., Frost M., Muller R., Burden A.M., Rivadeneira F., Napoli N., Rauner M. Bone fragility in diabetes: novel concepts and clinical implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(3):207–220. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appelman-Dijkstra N.M., Papapoulos S.E. Modulating bone resorption and bone formation in opposite directions in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Drugs. 2015;75(10):1049–1058. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Z., Li W., Jiang K., Lin Z., Qian C., Wu M., Xia Y., Li N., Zhang H., Xiao H., Bai J., Geng D. Regulation of bone homeostasis: signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. MedComm. 2024;5(8) doi: 10.1002/mco2.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lei C., Song J.H., Li S., Zhu Y.N., Liu M.Y., Wan M.C., Mu Z., Tay F.R., Niu L.N. Advances in materials-based therapeutic strategies against osteoporosis. Biomaterials. 2023;296 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2023.122066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng S., Wang K.H., Zhou L., Sun Z.J., Zhang L. Tailoring biomaterials ameliorate inflammatory bone loss. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13(12) doi: 10.1002/adhm.202304021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf S.J., Melvin W.J., Gallagher K. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in diabetic wound repair. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;119:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y., Zhou Y., Lin J., Zhang S. Challenges to improve bone healing under diabetic conditions. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.861878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita Y., Hosokawa M., Fujimoto S., Mukai E., Abudukadier A., Obara A., Ogura M., Nakamura Y., Toyoda K., Nagashima K., Seino Y., Inagaki N. Metformin suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis and lowers fasting blood glucose levels through reactive nitrogen species in mice. Diabetologia. 2010;53(7):1472–1481. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horakova O., Kroupova P., Bardova K., Buresova J., Janovska P., Kopecky J., Rossmeisl M. Metformin acutely lowers blood glucose levels by inhibition of intestinal glucose transport. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):6156. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42531-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foretz M., Guigas B., Viollet B. Understanding the glucoregulatory mechanisms of metformin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019;15(10):569–589. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou G., Myers R., Li Y., Chen Y., Shen X., Fenyk-Melody J., Wu M., Ventre J., Doebber T., Fujii N., Musi N., Hirshman M.F., Goodyear L.J., Moller D.E. Role of AMP-Activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J. Clin. Investig. 2001;108(8):1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X., Wang L., Chen X.-F., Liang Q., Wang W.-Q., Lin A.-Q., Yi L., Wang Y., Gao Q. Metformin improved oxidized low-density lipoprotein-impaired mitochondrial function and increased glucose uptake involving Akt-AS160 pathway in raw264.7 macrophages. Chin. Med. J. 2019;132(14):1713–1722. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin Y., Zhang Z., Guo X., Li W., Xia W., Ge G., Li Y., Guan M., Gao A., Mao L., Wang H., Chu P.K., Geng D. A bone‐targeting hydrogen sulfide delivery system for treatment of osteoporotic fracture via macrophage reprogramming and osteoblast‐osteoclast coupling. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao H., Duan L., Zhang Y., Cao J., Zhang K. Current hydrogel advances in physicochemical and biological response-driven biomedical application diversity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):426. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00830-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu S., Zheng W., Wang L., Zhang Y., Feng K., Zhang Y., Yang H., Xiao Y., Sun C., Liu X., Lu B., Yin X. Bioinspired hydrogel for sustained minocycline release: a superior periodontitis solution. Mater. Today Bio. 2025;32 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.101638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z., Sun Z., Zhu S., Qin Z., Yin X., Ding Y., Gao H., Cao X. A multifunctional hydrogel loaded with magnesium-doped bioactive glass-induced vesicle clusters enhances diabetic wound healing by promoting intracellular delivery of extracellular vesicles. Bioact. Mater. 2025;50:30–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2025.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu Y., Okuro K., Ding J., Aida T. Clay nanosheet‐based nanocomposite supramolecular hydrogel enabling rapid, reversible phase transition only with visible light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025;64(4) doi: 10.1002/anie.202416541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Q., Miao Y., Luo J., Chen Y., Wang Y. Amyloid fibril and clay nanosheet dual-nanoengineered DNA dynamic hydrogel for vascularized bone regeneration. ACS Nano. 2023;17(17):17131–17147. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c04816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]